|

"The tyrannous discipline of the 'Bastille,' or Union

Workhouses erected under the New Poor Law of 1834 . . . the vengeful

feeling created, in our starved manufacturing districts, towards the

harsh provisions of that Law, was the fiercest and bitterest I ever

heard expressed by working men."

Thomas Cooper, from

his introduction to 'The

Purgatory of Suicides'.

"Chartism is one of the most natural phenomena in England."

Thomas Carlyle, from "Chartism."

"It is notorious that all the great remedial measures

which have proved the most effective checks against the abuses of

capitalistic competition are of English origin. Trade Unions,

Co-operation, and Factory Legislation are all products of English

soil. That the revolutionary reaction against

capitalism is equally English in its inspiration is not so generally

known."

Professor H. S. Foxwell: Introduction to Menger's The Right to the Whole Produce

of Labour. |

|

MARK HOVELL

|

|

|

MARK HOVELL

(1888-1916) |

"There are two distinct aspects to Chartism as generally

conceived down to 1840, and as conceived after that date by the

National Charter Association. On the one hand, it is an

agitation for the traditional Radical Programme; on the other, it is

a violent and vehement protest from men, rendered desperate by

poverty and brutalised by excessive labour, ignorance, and foul

surroundings, against the situation in life in which they found

themselves placed. This protesting attitude had been brought,

by the teachings of leaders and the prosecutions of authority, to a

pitch of bitterness hardly now conceivable."

"It was from the Chartists and their forerunners that Marx and

Lasalle learned much of the doctrine which was only to come back to

these islands when its British origin had been forgotten."

Mark Hovell, from "The

Chartist Movement." |

――――♦――――

|

ALTHOUGH born

towards the end of the Victorian era, Mark Hovell

and Julius West (actually a Russian by birth—just) cannot be considered Victorian authors; so why include

them within a library devoted to Victorian writers?

A number of the poets and authors listed in the

Index to this Victorian writers website were involved

actively in the Chartist movement and left us their perspectives on that period

of British socio-political history, mainly the decade from 1838. Of

these, William Lovett,

James Watson and

Ernest Jones were most

closely involved with the movement, but Adams,

Arnott,

Bezer,

Cooper,

Holyoake,

Linton and

Massey also gave of themselves

generously in promoting the aims of the

People's Charter.

They left us their impressions and feelings ― sometimes in

prose, sometimes in verse ― of this struggle of the British

working-class against the oppression and injustice inflicted upon

them by a society dominated overwhelmingly by a wealthy and privileged

(male) minority. . . .

|

". . . . Deeply impressed with the conviction of the evils

arising from class legislation and of the

sufferings thereby inflicted upon our industrious fellow

subjects, the undersigned affirm that a large majority

of the people of this country are unjustly excluded

from that full, fair and free exercise of the elective

franchise to which they are entitled by the great

principle of Christian equity and also by the British

Constitution, ‘for no subject of England can be

constrained to pay any aids or taxes, even for the

defence of the realm or the support of the Government,

but such as are imposed by his own consent or that of

his representatives in Parliament.’"

The "Sturge Declaration" . . . from , "The

Chartist Movement." |

Mark Hovell, a professional historian writing some 50

years after the dust thrown up by the pleas and demands of those turbulent

times had mostly settled ― for in Hovell's day

universal suffrage had still to be achieved ― and with research material by then

more readily available, was able to provide a

wider and more objective assessment of the Chartist movement* than

could such as William Lovett, a poor,

self-educated man who had suffered incarceration

for sedition within the appalling prison conditions of that age and

experienced a life not greatly better at other times . . . .

|

". . . . their memoirs share fully in the

necessary limitations of the literary type to which they

belong. There are failures of memory,

over-eagerness to apologise or explain, strong bias,

necessary limitation of vision which dwells excessively

on trivial detail and cannot perceive the general

tendencies of the work in which the writers had taken

their part. But, however imperfect they may be as

set histories of Chartism, we find in most of them that

same note of simplicity and sincerity that had marked

their authors' careers. If these records make it

patent why Chartism failed, they give a shrewder insight

than any merely external narrative can afford of the

reasons why the movement spread so deeply and kept so

long alive. They enable us to understand how,

despite apparent failure, Chartism had a part of its own

in the growth of modern democracy and industrialism."

The artizan

historians . . . from "The

Chartist Movement." |

A study to both perspectives is important ― indeed, essential ― to

gain a

good (but can it ever be complete?) understanding of the rise of the Chartist movement,

ultimately to become Victorian England's most successful political

failure . . . .

|

". . . . how many of the greatest movements

in history began in failure, and how often has

a later generation reaped with little effort abundant

crops from fields which refused to yield fruit to their

first cultivators? . . . . in

the long run Chartism by no means failed . . . . the principles of the Charter

have gradually become parts of the British

constitution . . . . its restricted platform of

political reform, though denounced as revolutionary at

the time, was afterwards substantially adopted by the

British State . . . . before all the Chartist leaders

had passed away, most of the famous Six Points became

the law of the land . . . . the Chartists have

substantially won their case. England has become a

democracy, as the Chartists wished, and the domination

of the middle class . . . . is

at least as much a matter of ancient history as the

power of the landed aristocracy."

Chartism's place

in history, from "The

Chartist Movement."

"The movement's failures lay in the direction of

securing legislation, or national approbation for its

leaders. Judged by its crop of statutes and

statues, Chartism was a failure. Judged by its

essential and generally overlooked purpose, Chartism was

a success. It achieved, not the Six Points, but a

state of mind. This last achievement made possible

the renascent trade union movement of the 'fifties, the

gradually improving organization of the working classes,

the Labour Party, the co-operative movement, and

whatever greater triumphs labour will enjoy in the

future."

Chartism's place

in history, from "A

History of the Chartist Movement." |

Mark Hovell was to become one of many young men of

great promise whose

lives were wasted in the slaughterhouse of the Western Front.† It is to the credit of his friends that his manuscript was prepared

for posthumous publication, for The Chartist Movement has

become a classic of its type.§ Julius West—who at

Professor Tout's request had reviewed Hovell's manuscript and proofsβ—also

died young, in 1918 at the age of twenty-seven, of influenza. A

History of the Chartist Movement was prepared by J. C. Squire

for publication, appearing in 1920.

I have transferred from within the body of Hovell's book

Professor Tout's brief biography of an all-too-brief life, which

appears below followed by J. C. Squire's Memoire of

Julius West.

――――♦――――

* Hovell's account covers the main period of

Chartism to the summer of 1842 when his incomplete manuscript

ends. Professor Tout concludes the story, drawing

on Hovell's notes, knowing his

lectures on Chartism and being aware of his intentions for what

would have been the final section of

his book.

† Second

Lieutenant Mark Hovell, 1st Battalion, Sherwood Foresters (Notts and

Derby Regiment). Killed in action 12 August, 1916. Son of

William and Hannah Hovell, of Brooklands, Cheshire; husband of Fanny

Hovell, of Milton Cottage, John St., Sale, Cheshire. Langton Fellow

of Manchester University, 1911-14. Mark Hovell lies in Vermelles

Military Cemetery, Pas-de-Calais (Plot: III. N. 7).

§ Manchester University Press,

1918; 1925 (revised; this online edition) ― reprinted 1963

and 2008 (by Kessinger Publishing from the 1918 edition).

β "It remained to prepare the book for the press. As a first

step I was advised by Mr. Wallas to submit the manuscript to

Mr. Julius West, the author of a recently completed History of

Chartism, whose publication is only delayed by war conditions.

Mr. West has been kind enough to go through the whole manuscript and

also to read the proofs. His help has been of great service,

not only in correcting errors, resolving doubts, and removing

occasional repetitions, but also in advising as to the form which

the publication was to take. He also drew up the basis of the

bibliography. Mr. West informs me that his study and Hovell's

have some points of almost complete agreement, notably where both

differ from recent German writings. It is hardly needful to

say that Mr. West had come to his conclusions before this book had

been put in his hands." |

Vermelles Military Cemetery

|

The Guardian

11th August, 1947.

JAQUES――HOVELL. ― On

August 9, at Sale Congregational Church, by the Rev.

George Benton, NORMAN CLIFFORD JAQUES, D.A.

(Manchester), younger son of Mr. and Mrs. J. C. Jaques,

of Prestwich to MAJORIE, only daughter of the late Mark

HOVELL, M.A. and Mrs Hovell, of Sale. |

――――♦――――

INTRODUCTION

MARK HOVELL:

a brief biography by

Professor T. F. Tout.

THE author of

this book [The Chartist

Movement] belonged to the great class of young scholars of

promise, who, at the time of their country's need, forsook their

studies, obeyed the call to arms, and gave up their lives in her

defence. It is well that the older men, who cannot follow

their example, should do what in them lies to save for the world the

work of these young heroes, and to pay such tribute as they can to

their memory.

Mark Hovell, the son of William and Hannah Hovell, was born

in Manchester on March 21, 1888. In his tenth year he won an

entrance scholarship at the Manchester Grammar School from the old

Miles Platting Institute, now replaced by Nelson Street Municipal

School. It was the earliest possible age at which a Grammar

School Scholarship could be won. From September 1898 to

Christmas 1900 he was a pupil at the Grammar School, mounting in

that time from IIc to Vb on the modern side.

Circumstances forced him to leave school when only twelve years of

age, and to embark in the blind-alley occupations which were the

only ones open to extreme youth. Fortunately he was enabled to

resume his education in August 1901 as a pupil teacher in Moston

Lane Municipal School, whose head master, Mr. Mercer, speaks of him

in the warmest terms. Hovell also attended the classes of the

Pupil Teachers' College. From November 1902 to February 1904 a

serious illness again interrupted his work, but he then got back to

his classes, and at once went ahead. Mr. W. Elliott, who first

gave him his taste for history at the Pupil Teachers' College, fully

discerned his rare promise. "He was," writes Mr. Elliot,

"undoubtedly the brightest, keenest, and most versatile pupil I have

ever taught, and his fine critical mind seemed to delight in

overcoming difficulties. He was a most serious student, but he

possessed a quiet vein of humour we much appreciated. We all

looked with confidence to his attaining a position of eminence."

This opinion was confirmed by the remarkable papers with which in

June 1906 he won the Hulme Scholarship at our University, which he

joined in the following October. This scholarship gives full

liberty to the holder to take up any course he likes in the

University, and Hovell chose to proceed to his degree in the Honours

School of History. During the three years of his undergraduate

course he did exceedingly good work. After winning in 1908 the

Bradford Scholarship, the highest undergraduate distinction in

history, he graduated in 1909 with an extremely good first class and

a graduate scholarship. In 1910 he took the Teachers' Diploma

as a step towards redeeming his pledge to the Government, which had

contributed towards the cost of his education.

|

"People now

are prone to look upon the stormy and infuriate opposition to the

Poor Law as based upon mere ignorance. Those who think

so are too ignorant to understand the terrors of those times.

It was not ignorance, it was justifiable indignation with which the

Poor Law scheme was regarded. Now, the mass of the

people do not expect to go to the workhouse and do not intend

to go there. But through the first forty years of this century

almost every workman and every labourer expected to go there sooner

or later. Thus the hatred of the Poor Law was well founded.

Its dreary punishment would fall, it was believed, not upon the idle

merely, but upon the working people who by no thrift could save, nor

by any industry provide for the future."

Mark Hovell ― the seeds of Chartism . . . from "The

Chartist Movement." |

The serious work of life was now to begin. It was the

time when the Workers' Education Association was first operating on

a large scale in Lancashire, and he was at once swept up into the

movement, being appointed in 1910 assistant lecturer in history at

the University with special charge of W.E.A. classes at Colne,

Ashton, and Leigh, to which others were subsequently added. He

threw himself into this work with the greatest energy. He took

the greatest pains in presenting his material in an acceptable form.

His youthful appearance excited the suspicions of some among his

elderly auditors. They used, Mr. Paton tells me, "to lay traps

for him. He seemed to know so much, and they wanted to see if

it was all 'got up for the occasion.' But he was a 'live

wire.' He used to heckle me fine after education lectures at

College." This early acquired skill in debate soon rode

triumphant over the critics. He did not content himself simply

with giving lectures and taking classes. In order to get to

know his pupils personally, he stayed over week-ends at the towns

where he taught. He had long Sunday tramps with his disciples

over the moors, and though he never flattered them, and was perhaps

sometimes rather austere in his dealings with them, he soon

completely won their confidence and affection. I remember the

embarrassment felt by the administrators of the movement, when a

class, which had had experience of his gifts, almost revolted

against the severely academic methods of a continuator of his

course, and was only appeased when it was fortunately found possible

to bring him back to his flock without compromising the situation.

He continued in this work as long as he was in England, and when the

winter of 1913-14 took him to London, he had the same success with

the south-country workmen as with the men he had known from youth up

in the north. Mr. E. H. Jones, the secretary of his Wimbledon

class, thus describes the impression he made there with a course on

the "Making of Modern England":

Many of the students had

misgivings as to the success of what appeared to them as a dull,

drab, and dreary subject. These doubts were further increased

when, at the first preliminary meeting, a slim, quiet, unassuming,

and nervous young man got up, and in a hesitating manner outlined

the chief features of the course. The first lecture, however,

was sufficient to ensure the success of the venture. His

thorough knowledge of the subject, his clear and incisive style,

together with a charming personality, held the attention of the

class. His realistic description of the condition of the

people, especially of the working classes, during the early part of

the nineteenth century — the homes they lived in and the lives they

lived — showed us at once a man with a large heart, one who

sympathised with the sorrows and the sufferings of the people.

His great desire was to serve his fellows by educating, and so

exalting the manhood of the nation. We, who knew him,

understand the motives which prompted him to offer his life for the

sake of our common humanity. He hated tyranny; the beat of the

drums of war had no charms for him, unless the call was in the cause

of Justice and Liberty." [The Highway, December 1916,

pp. 56-57.]

This appreciation is not overdrawn. There was nothing

in Hovell of the clap-trap lecturer for effect. His rather

conservative point of view knew little of short cuts, either to

social amelioration or to the solution of historic problems.

He offered sound knowledge coupled with sympathy and intelligence,

and it is as much to the credit of the auditors as of the lecturer

that they gladly took what be had to give.

Howell's lecturing, important as it was, could only be

subsidiary to the attainment of his main purpose in life. As

soon as he graduated, he made up his mind to equip himself by

further study and by original work for the career of a university

teacher of history. His degree course had given him a

practical example of the character of two widely divergent periods

of history, studied to some extent in the original authorities.

One of these was the reign of Richard II., which he had studied

under the direction of Professor Tait. He had sent up a degree

thesis on Ireland under Richard II., written with a maturity and

thoughtfulness which are rarely found in undergraduate essays.

This essay he afterwards worked into a study which we hope to print,

when conditions again make academic treatises on mediaeval problems

practical politics. It was evidence that he might, if he had

chosen, become a good mediaevalist. But his temper always

inclined him towards something nearer our own age, and his other

special subject, the Age of Napoleon I., seemed to him to lead to

wide fields of half-explored ground in the first half of the

nineteenth century. He attended for this course lectures of my

own on the general history of the period, and made a special study

of some of the Napoleonic campaigns, which he studied under the

direction of Mr. Spenser Wilkinson, then lecturer in Military

History at Manchester, and now Chichele Professor of that subject at

Oxford. It was Mr. Wilkinson's lectures that first kindled his

enthusiasm for military history.

Howell's main bent was towards the suggestive and

little-worked field of social history, and his interest in the

labour and social problems in the years succeeding the fall of

Napoleon was vivified by the practical calls of his W.E.A. classes

upon him. I feel pretty sure that it was the stimulus of these

classes that finally made him settle on the social and economic

history of the early Victorian age as his main subject. It was

upon this that he gave nearly all his lectures to workmen.

Indeed, much of the vividness and directness of his appeal was due

to the fact that he was speaking on subjects which he himself was

investigating at first hand. A deep interest in the condition

of the people, a strong sympathy with all who were distressfully

working out their own salvation, a rare power of combining interest

and sympathy with the power of seeing things as they were, made his

progress rapid, and increasing mastery only confirmed him in his

choice of subject. Finally he narrowed his investigations to

the neglected or half-studied history of the Chartist Movement, and

examined with great care the economic, social, and political

conditions which made that movement intelligible.

|

". . . . In truth the aspect of Great Britain in these

days was sufficiently terrifying. From Bristol to

Edinburgh and from Glasgow to Hull rumours of arms,

riots, conspiracies, and insurrections grew with the

passing of the weeks. Crowded meetings applauded

violent orations, threats and terrorism were abroad.

Magistrates trembled and peaceful citizens felt that

they were living on a social volcano. The frail

bonds of social sympathy were snapped, and class stood

over against class as if a civil war were impending."

Mark Hovell ― the year 1839 . . . from "The

Chartist Movement." |

Hovell's teachers were not unmindful of his promise, and in

1911 his election to the Langton fellowship, perhaps the highest

academic distinction at the disposal of the Arts faculty of the

Manchester University, provided him with a modest income for three

years during which he could carry on his investigations, untroubled

by bread problems. He now cut down his teaching work to a

minimum, and threw himself wholeheartedly into his studies.

Circumstances, however, were not very propitious to him. He

was a poor man, and was the poorer since his abandonment of school

teaching involved the obligation of repaying the sums advanced by

the State towards the cost of his education. The work he now

desired to do was perhaps as honourable and useful as that for which

he had been destined. It was, however, different. He had

received State subsidies on the condition that he taught in schools,

and he chose instead to teach working men and University students.

So far as his bond went, he had, therefore, nothing to complain of.

The Board Education, though meeting him to some extent, was not

prepared, even in an exceptional case, to relax its rules

altogether. While recognising the inevitableness of its

action, it may perhaps be permitted to hope that the time may come,

even in this country, when it will be allowed that the best career

for the individual may also be the one which will prove the most

profitable to the community. Otherwise, the compulsion imposed

on boys and girls, hardly beyond school age, to pledge themselves to

adopt a specific career may have unpleasant suggestions of something

not very different from the forced labour of the indentured coolie

or Chinaman.

Other difficulties stood in Howell's way. He had to

continue his W.E.A. classes until he had completed his obligations

to them, and it required moral courage to avoid accepting new ones.

The University also had its claims on him, and untoward

circumstances made his lectureship much more onerous than it had

been intended to be. In the spring of 1911 a serious illness

kept me away from work, and between January and June 1912 the

University was good enough to allow me two terms' leave of absence.

On both occasions Howell was asked to deliver certain courses of my

lectures, and I shall ever be grateful for the readiness with which

he undertook this new and onerous obligation. But he gained

thereby experience in teaching large classes of students, and it all

came as part of the day's work. Despite this his study of the

Chartists made steady progress.

A further diversion soon followed. Up to now Hovell's

work had lain altogether in the Manchester district, and

Wanderjahre are as necessary as Lehrjahre to equip the

scholar for his task. The opportunity for foreign experience

came with the offer of an assistantship in Professor Karl

Lamprecht's Institut für Kultur und Universalgeschichte at Leipzig

for the academic session of 1912-1913. This offer, which came

to him through the kind offices of Sir A. W. Ward, Master of

Peterhouse, was the more flattering since the Leipzig Institute was

a place specially devised to enable Dr. Lamprecht to disseminate his

teaching as to the nature and importance of Kulturgeschichte.

Reduced to its simplest terms Lamprecht's doctrine is that the

social and economic development of society is infinitely more

important than the merely political history to which most historians

have limited themselves. Not the State alone but society as a

whole is the real object of the study of the historian.

Various doubtful amplifications and presuppositions involved in

Lamprecht's teaching in no wise impair the essential truth of the

broad propositions on which it is based.

|

"The night falls fast, and finds me brooding thus

O'er evils that afflict my fatherland:—

The night falls fast, yet brightly luminous

Beam out the cotton mills that round me stand,

Where garish gas turns night to day; and hand,

And eye, and mind of myriad toilers win

The wealth of England, but cannot command

A certainty of bread,—though, for her sin,

Woman,

like man, doth weave, and watch, and toil,

and spin."

Thomas

Cooper . . . from "The

Paradise of Martyrs". |

Hovell's own studies of social history showed him to be

predisposed to sympathy with the master. But he had never been in

Germany, and his German was almost rudimentary. However, he worked

up his knowledge of the tongue by acquiring from Lamprecht's own

works the point of view of the great apostle of Kulturgeschichte.

Accordingly by the time Hovell reached Leipzig, he bad acquired the

keys both of the German language and of Lamprecht's general

position. He found that Lamprecht's Institute, though loosely

connected with the University, was a self-contained and

self-sufficing seminary for the propagation of the new historic

gospel, and looked upon with some coldness and suspicion by the more

conservative historical teachers. It was a wise part of the

system of the Institute that certain foreign "assistants" should

present the social history of their own country from the national

point of view. Towards this task Howell's contribution was to

be an exposition of the social development of England in the

nineteenth century, so that his Chartist studies now stood him in

good stead. He was, however, profoundly convinced of the high

standard required from a German University teacher, and made

elaborate preparations to give a course of adequate novelty and

thoroughness. Unfortunately he found that the students who

gradually presented themselves were far from being specialists.

They were not even anxious to become specialists, and were nearly

all somewhat indifferent to his matter, looking upon the lectures

and discussions as an easy means of increasing their familiarity

with spoken English.

The beginning was rather an anxious time, especially when

presiding over and criticising the reading of the referate,

or students' exercises, which alternated with his set lectures.

He was impressed with the power of his pupils to write and discuss

their themes in English, though glad when increasing familiarity

with German enabled him also to deal with their difficulties in

their own tongue. The only other academic work that he essayed

was taking part in Professor Max Förster's English seminar.

The lightness of the daily task gave him leisure for looking round,

and seeing all that he could see of Germany and German social and

academic life. He attended many lectures, delighting

especially in Förster's clear and stimulating course on Shakespeare,

broken on one occasion by a passionate exhortation to the students

to forsake their beer-drinkings and duels, and to cultivate manly

sports after the English fashion, so as to be able the better to

defend their beloved Fatherland. He was much impressed by

Wundt, the psychologist, "a little plain and unassuming-looking man

dressed in undistinguished black, lecturing with astounding

clearness and strength, at the age of 81, to a closely packed and

attentive audience of fully 350 students, who look on him as the

wonder of his age, and are eager to catch the last words that might

come from the lips of the master." He heard all that he could

from Lamprecht himself, with whom his relations soon became

exceedingly cordial. He found him genial, friendly, and

good-natured, and he was impressed by his dominating personality and

missionary fervour, his broad sweep over all times and periods, the

width of his interests, and the extent of his influence. He

sincerely strove to understand the mysteries of the new science.

The very abstractness and theoretical character of the Lamprechtian

method was a stimulus and a revelation to a man of clear-cut

positive temperament, schooled in historical teaching of a much more

concrete character. It was easy to hold his own in the English

seminar where the discussions were in his own tongue. But he

gradually found himself able to take his share in Lamprecht seminar,

where all the talk was in German. "My reputation among the

students," he writes, "was founded on my knowledge that the

predecessor of the Reichsgericht sat at Wetzlar." It was a

proud moment when he had to explain that the master's confusion of

the modern English chief justice and the justiciar of the twelfth

century was the natural error of the foreigner. He was still

more gratified when called upon by Lamprecht to read an elaborate

treatise in German on the der englische Untertanenbegriff,

the English conception of political subjection. His only

embarrassment now was that he could never quite convince himself

that there was any specifically English conception of the subject at

all, and that he rather wondered whether Lamprecht knew whether

there was one either. But however much he criticised, he never

lost his loyalty to the man. His doubts of the Lamprechtian

system became intensified when he found underlying it errors of

fact, uniform vagueness of detail, and cut-and-dried theoretical

presuppositions against which the broad facts of history were

powerless to prevail. One of his last judgments, made in a

letter to me in June 1913, is perhaps worth quoting:

Professor Lamprecht is lecturing

this term on the history of the United States. His course is

exceedingly interesting, but I am bound to say that his history

strikes me as highly imaginative. He never speaks of the

English colonies. They are always "teutonisch," except when

(as to-day) be says in mistake "deutsch." Thus Virginia in

1650 was "teutonisch." He persistently depreciates the English

element on the strength of the existence of a few Swedish, Dutch,

and German settlements. By some magic English colonists cease

to be English as soon as they cross the ocean, so that their desire

for freedom and political equality owes little or nothing to the

fact of their being English. He carefully distinguishes even

Scots from English. He views the history of America down to

1763 as an episode in the eternal struggle of the "romanisch " and "teutonisch"

peoples, and the beginning of the decided triumph of the latter,

whose greatest victory of course was in 1870-71. I am firmly

convinced that he neither understands England, nor the English, nor

English history. Still, although I don't agree with half he is

saying, I find his method of handling things interesting; he

stimulates thought, if only in the effort to follow his.

The whole period at Leipzig was one of intense activity.

Hovell enjoyed himself thoroughly. He was always eager to

widen his experiences, and found much kindness from seniors and

juniors, Germans and compatriots. He made a special ally of

his French colleague, who did not take Kulturgeschichte quite

so seriously as he did. The two exiles spent the short

Christmas recess in a tour that extended as far as Strasburg, where

they moralised on the contrasts between the new Strasburg, that had

arisen after 1871, and the old city, that still sighed for the days

when it was a part of France. At Leipzig Hovell revelled in

the theatres, in the Gewandhaus concerts, the singing of the

choir of the Thomas Kirche, and the old Saxon and Thuringian

cities, churches, and castles. He was specially impressed with

the orderly development from a small ancient nucleus of the modern

industrial Leipzig, with its well-planned streets and spacious

gardens, with which the Lancashire towns which he knew contrasted

sadly. He attended all manner of students' festivities, drank

beer at their Kneipen, and witnessed, not without severe

qualms, the bloodthirsty frivolities of a students' duel. He

was present when the King of Saxony, whose personality did not

impress him, came to Leipzig to spend a morning in attending

University lectures and an afternoon in reviewing his troops.

He saw Gerhard Hauptmann receive an honorary degree, and delighted

in the poet's recitation of a piece from one of his unpublished

plays. He was so quick to praise the better sides of German

life that he was condemned by his French colleague for his excessive

accessibility to the Teutonic point of view. His appreciation

of German method extended even to the police, whom he eulogised as

efficient, and not too obtrusive in their activities. He

recognised the thoroughness, economy, and thriftiness with which the

Germans organised their natural resources. He spoke with

enthusiasm of the ways in which the Germans studied and practised

the art of living, their adaptation of means to ends, their

avoidance of social waste. He was struck with the absence of

visible slums and apparent squalor. The spectacle of the

material prosperity obtained under Protection led him to wonder

whether the gospel of Cobden in which, like all good Manchester men,

he had been brought up, was necessarily true in all places and under

all conditions. But he had enough clarity of vision to see

that there was another side to the apparent comfort and opulence of

Leipzig. He was appalled at the lack of method and

organisation when individual enterprise was left to work out details

for itself, as was notably instanced by the slipshod, happy-go-lucky

ways in which the affairs of the Institute and University were

conducted. He watched with keen interest elections for the

Saxon Diet or Landtag, when Leipzig's discontent with the

constitution of society rose triumphant over an electoral system as

destructive to the expression of democratic control as that of the

Prussian Diet itself. Things could hardly be well when Leipzig

returned, by overwhelming majorities, both to the local and to the

imperial Parliaments, Social Democrats pledged to the extirpation of

the existing order. A constitution, cunningly devised to

suppress popular suffrage, and manhood voting yielded the same

result.

|

". . . . The Chartists first compelled attention

to the hardness of the workmen's lot, and forced

thoughtful minds to appreciate the deep gulf between the

two "nations" which lived side by side without knowledge

of or care for each other. Though remedy came

slowly and imperfectly, and was seldom directly from

Chartist hands, there was always the Chartist impulse

behind the first timid steps towards social and economic

betterment. The cry of the Chartists did much to

force public opinion . . . ."

Hovell: Chartism's place

in history . . . from "The

Chartist Movement." |

Another aspect of German opinion was strange and painful to

him. He had been taught that in Germany the enthusiasts for

war were as negligible an element as the "militarists" of his own

land. But he soon found that the truth was almost the reverse

of what he had expected. From the beginning he was appalled,

too, by the widespread evidence of deep-rooted hostility to England,

even in the academic circles which received him with the utmost

cordiality. The violence of the local press, the denunciations

of England by stray acquaintances in trains and cafes, seemed to him

symptomatic of a deep-set feeling of hatred and rivalry. He

saw that Lamprecht studied English history in the hope of

appropriating for his own land the secret of British prosperity, and

that Förster exhorted the students to play football that they might

be better able to fight England when the time arrived, and that both

were confident that the time would soon come. He was disgusted

at the crass materialism he saw practised everywhere. He was

particularly moved by a quaint exhortation to the local public to

contribute handsomely to celebrate the Emperor's jubilee by

subscribing to a national fund for missions to the heathen. No

one saw anything scandalous or humorous in a spiritual appeal based

on the most earthly of motives, and centring round the arguments

that a large collection would please the Kaiser, and that, as

England and America had used missionaries as pioneers of trade and

might, Germany must also "prepare the way for world-power by the

faithful and unselfish labours of her missionaries in opening up the

economic and political resources of her protectorates." He saw

that Deutschland über alles meant to many Germans a curious

dislocation of values. An agreeable young privatdocent,

who visited him later in England, showed something of the same

spirit when, coming with a Manchester party on an historical

excursion to Lincoln, he saw nothing to admire in the majestic city

on a hill nor in the wonderful cathedral. Far finer sites and

much better Gothic art were, he solemnly assured us, to be seen in

Saxony and the Mark of Brandenburg. Very few of his many

German friends had Hovell's keen sense of humour.

Hovell's stay in Germany was broken by a visit to England at

Easter 1913, when he attended the International Historical Congress

in London, where he introduced me to Lamprecht. I was much

impressed with the fluency and accuracy which Hovell's German speech

had now attained, as well as with the cordiality of his relations to

his large German acquaintance. He returned to Leipzig for the

summer semester, and was back in England for good by August.

The novel Leipzig experiences had thrown the Chartists into

the shade, the more so as Hovell found the University Library

capriciously supplied with English books, and catalogued in somewhat

haphazard fashion. But he profited by the opportunity of a

careful study of the important works which notable German scholars

had recently devoted to the neglected history of modern British

social development. He found some of these monographs were

"too much after the German style, rather compendia than analytical

treatises, but useful for facts, references, and bibliographies."

Others of the "more philosophic sort" gave him "good ideas," and he

regarded Adolf Held's Zwei Bücher über die sociale Geschichte

Englands "specially good." Steffen's Geschichte der

englischen Lohnarbeiter, the translation of a Swedish book by a

professor at Göteborg, and M. Beer's Geschichte des Socialismus

in England were also extremely useful. But he was soon on

his guard against the widespread tendency to wrest the facts to suit

various theoretical presuppositions, and to realise the fundamental

blindness to English conditions and habits of thought that went

along with laborious study of the external facts of our history.

Though he by no means worked up all his impressions of German

authors into his history, the draft, which he left behind him, bears

constant evidence alike of their influence and of his reaction from

it. It was at this time he first saw his work in print in the

shape of a review of Professor Liebermann's National Assembly in

the Anglo-Saxon Period, contributed to a French review.

On returning to England Hovell established himself in London,

where he worked hard at the Place manuscripts (unhappily divided

between Bloomsbury and Hendon), the Home Office Records, and other

unpublished Chartist material. During the winter he took a

W.E.A. class at Wimbledon. By the summer of 1914 he was ready

to settle at home again and to put together his work on the

Chartists. His fellowship now coming to an end, he undertook

more W.E.A. courses in the Manchester district for the winter of

1914-1915, and a small post was found for him at the University,

where he received charge of the subject of military history.

This study the University prepared to develop in connection with a

scheme for preparation of its students for commissions in the army

and territorial forces.

No sooner were these plans settled than the great war broke

out. The classes in military history were reduced to

microscopic dimensions, since all students keen on such study

promptly deserted the theory for the practice of warfare.

Though anxious to follow their example, Hovell remained at his work

until the late spring of 1915, finding some outlet for his ambition

to equip himself for military service in the University Officers'

Training Corps, in which he was a corporal. In May, as soon as

his lectures to workmen were over, he applied for a commission.

He had nothing of the bellicose or martial spirit; but he had a

stern sense of obligation and a keen eye to realities. Like

other contemporaries who had sought experience in Germany, he fully

realised the inevitableness of the struggle, and he knew that every

man was bound to take his place in the grave and prolonged effort by

which alone England could escape overwhelming disaster. "I

don't think," he wrote to me, "I shall dislocate the economy of the

University by joining. What troubles me is of course my book.

I have written nearly a chapter a week since Easter. At this

rate I shall have the first draft nearly completed by the end of

another three months, and I am therefore very keen to finish it.

If there were no newspapers I could keep on with it; but the

Chartists are dead and gone, while the Germans are very much alive."

In June Hovell was sent to a school of instruction for

officers at Hornsea, where they gave him, he said, the hardest

"gruelling" in his life, and from which he emerged, at the end of

July, at the head of the list with the mark "distinguished" on his

certificate. He was gazetted in August to a "Kitchener"

battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, the Nottingham and Derby

Regiment. But officers' training had not yet become the deftly

organised system into which it has now developed. When Hovell

joined his battalion at Whittington Barracks, near Lichfield, he

found himself one of a swarm of supernumerary subalterns, who had no

place in the scheme of a battalion fully equipped with officers.

As there were no platoons available for the newcomers to command,

they were put into instruction classes, hastily and not always

effectively devised for their benefit. He rather chafed at the

delay but enjoyed the hard life and the new experience. It was

soon diversified by a course of barrack-square drill with the Guards

at Chelsea, by an informal assistantship to a colonel who ran an

instructional school for officers, by a very profitable month at the

Staff College at Camberley, where he soon "felt quite at home,

seeing that the place is so like a University with its lecture-rooms

and libraries and quiet places," and by a period of musketry

instruction in Yorkshire, where an evening visit to York gave him

his first practical experience of a Zeppelin raid. Altogether

a year was consumed in these preliminaries.

In June 1916 Hovell was back with his battalion, now camped

in Cannock Chase. On June 3 he married Miss Fanny Gatley of

Sale, the Cheshire suburb in which his own family had lived in

recent years. A little later he wrote: "We managed a whole

week in the Lake District, where it rained all the time. Then

I went back to my regiment and my wife came to stay two miles away."

Then the attack on the Somme began, and "we heard rumours that

officers were being exported by the hundred." On July 4 he

received orders to embark, and crossed to France a week later.

There were some vexatious delays on the other side, but at last he

joined one of the regular battalions of his regiment in a small

mining village. The battalion had been cruelly cut up in the

recent fighting on the Somme, and the officers, old and new, were

strangers to him. But by a curious accident he found an old

friend in the chaplain, the Rev. T. Eaton McCormick, the vicar of

his parish at home. He was now plunged into the real business

of war, and did his modest bit in the reconstitution of the

shattered battalion. "I blossomed out," he wrote, "as an

expert in physical training, bayonet fighting, and map-reading to

our company. All the available N.C.O.'s were handed over to my

care, and they became enthusiastic topographers."

Before the end of the month the battalion was reorganised and

moved back into the trenches. On August 1 he wrote to me in

good spirits:

Behold me at last an officer of a

line regiment, and in command of a small fortress, somewhere in

France, with a platoon, a gun, stores, and two brother officers

temporarily in my charge. I thus become owner of the best

dug-out in the line, with a bed (four poles and a piece of stretched

canvas), a table, and a ceiling ten feet thick. We are in the

third line at present, so life is very quiet. Our worst

enemies are rats, mice, beetles, and mosquitoes.

This first experience of trench life was uneventful, and the

battalion went back for a short rest. The remainder of the

story may best be told in the words of Mr. McCormick, writing to

Hovell's mother to tell her the news of her son's death.

Mark and two other officers of the

Sherwood Foresters dined with me on Wednesday last, August 9.

We were a jolly party and talked a lot about home. After

dinner he asked me if it would be possible for him to receive the

Holy Communion before going into the trenches, and next morning I

took him in my cart two miles away, where we were having a special

celebration for chaplains. That was the last I saw of him

alive. He went into the trenches for the second time in his

experience (he had been in a different part of the line the week

before) on last Friday. On Saturday night at 9.10

P.M.,

August 12, it was decided that the Sherwood Foresters should explode

a mine under the German trenches. Mark was told off to stand

by with his platoon. When the mine blew up, one of Mark's men

was caught by the fumes driving up the shaft, and Mark rushed to his

rescue, like the brave lad that he was, and in the words of the

Adjutant of his battalion, "we think he in turn must have been

overcome by the fumes. He fell down the shaft and was killed.

The Captain of the company went down after him at once and brought

up his body.". . . They knew that he was a friend of mine, as

I had been telling the Colonel what a brilliantly clever man he was,

and what distinctions he bad won, so they sent for me, and the men

of his battalion carried his body reverently down the trenches.

We laid him to rest in a separate grave, and I took the service

myself. It was truly a soldier's funeral, for, just as I said

"earth to earth," all the surrounding batteries of our artillery

burst forth into a tremendous roar in a fresh attack upon the German

line.... He has, as the soldiers say, "gone West" in a blaze of

glory. He has fought and died in the noblest of all causes,

and though now perhaps we feel that such a brilliant career has been

brought to an untimely end, by and by we shall realise that his

sacrifice has not been in vain.

Over a year has passed away since Hovell made the supreme

sacrifice, and the cannon still roar round the British burial-ground

amidst the ruins of the big mining village of Vermelles where he

lies at rest. While north and south his victorious comrades

have pushed the tide of battle farther east, the enemy's guns still

rain shell round his unquiet tomb from the hitherto impregnable

lines that defend the approach to Lille.

Nothing more remains save to record the birth on March 26,

1917, of a daughter, named Marjorie, to Hovell and his wife, and to

give to the world the unfinished book to which he had devoted

himself with such extreme energy. This work, though very

different from what it would have been had he lived to complete it,

may do something to keep his memory green, and to suggest, better

than any words of mine can, the promise of his career. But no

printed pages are needed to preserve among his comrades in the

University and army, his teachers, his friends, and his pupils, the

vivid memory of his strenuous, short life of triumphant struggle

against difficulties, of clear thinking, high living, noble effort,

and of the beginnings of real achievement. For myself I can

truly say that I never had a pupil for whom I had a more lively

friendship, or one for whom I had a more certain assurance of a

distinguished and honourable career. He was an excellent

scholar in many fields; he could teach, he could study, and he could

inspire; he had in no small measure sympathy, aspiration, and

humour. He possessed the rare combination of practical wisdom

in affairs with a strong zeal for the pursuit of truth; he was a

magnificent worker; he kept his mind open to many interests; he had

a wonderfully clear brain; a strong judgment and sound common-sense.

I had confidently looked forward to his doing great things in his

special field of investigation. How far he has already

accomplished anything noteworthy in this book, I must leave it for

less biased minds to determine. But though I am perhaps

over-conscious of how different this book is from what it might have

been, I would never have agreed to set it before the public as a

mere memorial of a promising career cut short, if I did not think

that, even as it is, it will fill a little place in the literature

of his subject. When he finally set out for the front he

entrusted to me the completion of what he had written. I have

done my best to fulfil the pledge which I then gave him, that should

anything untoward befall him, I would see his book through the

press.

|

". . . . in 1917, in the midst of the Great

War, Parliament is busy with a third wide extension of

the electorate which, if carried out, will virtually

establish universal suffrage for all males, and,

accepting with limitations a doctrine which Lovett

considered too impracticable even for Chartists, will

allow votes to women under a fantastic limitation of age

that is not likely to endure very long" [Ed. ―

in fact, until 1928.]

Hovell ― Chartism's place

in history . . . from "The

Chartist Movement." |

|

――――♦――――

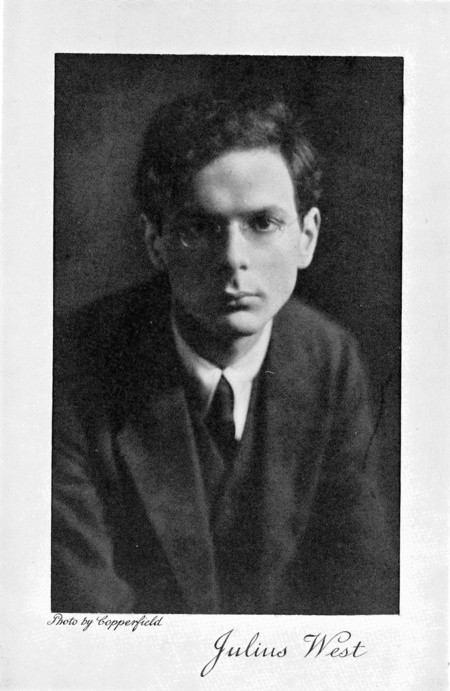

JULIUS WEST

|

"The Chartists were especially interesting as being in some

sort pioneers of the modern Labour movement in which West had grown

up; but he might have been drawn to any other such subject had he

found another that had been so neglected by English historians. It

did not take him long to discover that some current opinions would

have to be revised; that the physical menace of the Chartist

movement had often been exaggerated, and its historical importance

generally ignored."

J. C. Squire

INTRODUCTORY

MEMOIRE

by

J. C. Squire.

JULIUS

WEST was born in St.

Petersburg on March 21 (9th O.S.), 1891. In May, when he was

two months old, he went to London, where from that time onwards, his

father, Mr. Semon Rappoport, was correspondent for various Russian

papers. At twelve years of age West entered the Haberdashers'

(Aske's) School at Hampstead. He left school in 1906, and

became a temporary clerk in the Board of Trade, assisting in the

preparation of the report on the cost of living in Germany, issued

in 1908. On leaving the Board of Trade, he became a junior

clerk in the office of the Fabian Society, then in a basement in

Clement's Inn. (It was there that in 1908 or 1909 I first saw

him.) To get to the Secretary's room one had to pass through

the half-daylight of a general office stacked with papers and

pamphlets, and on some occasion I received the impression of a new

figure beyond the counter, that of a tall, white-faced, stooping

youth with spectacles and wavy dark hair, studious-looking, rather

birdlike. The impression is still so vivid that I know now I

was in a manner aware that he was unusual long before I was

conscious of any curiosity about him. I had known him thus

casually by sight for some time, without knowing his name; I had

known his name and his repute as a precocious boy for some time

without linking the name to the person. He was said to read

everything and to know a lot of economics; a great many people were

getting interested in him; he was called West and was a Russian, a

collocation which puzzled me until I learned that he was a Jew from

Russia who had adopted an English name. Although still under

twenty, he was already, I think, lecturing to small labour groups

when I got to know him more intimately. He knew his orthodox

economics inside out, and was in process of acquiring a peculiar

knowledge of the involved history of the Socialist movement and its

congeners during the last hundred years.

He was, in fact, already rather extraordinary. His

education had been broken off early, and he always regretted it; but

I have known few men who have suffered less from the absence of an

academic training. Given his origins, his early struggle, his

intellectual and political environment, the ease with which he

secured some sort of hearing for his first small speeches to

congenial audiences, one might have expected a very different

product. It would not have been surprising, had he, with all

his intellect, become a narrow fanatic with a revolutionary

shibboleth; it would not have been strange if, avoiding this because

of his common sense, he had been drawn into the statistical machine

and given himself entirely to collecting and digesting the materials

for social reform. He took a delight in economic theory and he

had a passion for industrial history: the road was straight before

him. But the pleasure and the passion were not exclusive.

Although it is possible that his greatest natural talents were

economic and historical, and (as I think) likely that had he lived

his chief work would have been along lines of which the present book

is indicative, he was in no hurry to specialize. He had a

catholic mind. Behind man he could see the universe, and,

unlike many Radicals of his generation, behind the problems and the

attempted or suggested solutions of his time, he could see the wide

and long historical background, the whole experience of man with the

lessons, moral, psychological and political, which are to be drawn

from it, and are not to be ignored. You may find in his early

writings (though not in this book) all sorts of crudities,

flippancies and loose assertions; he was young and impulsive, he had

been under the successive influences of Mr. Shaw and Mr. Chesterton,

and lacked their years and their command of language; he had a full

mind and a fluent pen which, when it got warm, sometimes ran away.

But at bottom he was unusually sane; and his sanity came in part

from the intellectual temper that I have sketched, but partly from a

sweet, sensitive and sympathetic nature which made injustice as

intolerable to him as it was unreasonable. He did not always

(being young and having had until the last year or two little

experience of the general world of men) realize how people would

take his words; but I never knew a man who more quickly or more

girlishly blushed when he thought he had said or written something

wounding or not quite sensible.

|

"The great

interest of the Chartist period is the active quest for ideas which

was then being carried on, and its first results. Within a few years

working men had forced upon their attention the pros and cons of

trade unionism, industrial unionism, syndicalism, communism,

socialism, co-operative ownership of land, land nationalization,

co-operative distribution, co-operative production, co-operative

ownership of credit, franchise reform, electoral reform, woman

suffrage, factory legislation, poor law reform, municipal reform,

free trade, freedom of the press, freedom of thought, the

nationalist idea, industrial insurance, building societies, and many

other ideas. The purpose of the People's Charter was to effect joint

action between the rival schools of reformers; but its result was

to bring more new ideas on to the platform, before a larger and

keener audience."

West: ideas put forward by the Chartist

Movement. |

Julius West's life was conspicuously a life of the mind.

But if the reader understands by an intellectual a man to whom books

and verbal disputations are alone sufficient, reservations must be

made. It is true that he was a glutton for books: he collected

a considerable library where Horace Walpole, Marx, Stevenson, Mr.

Conrad, Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Webb and Marlowe stood together.

His father writes: "He was a great reader, and his literary taste

even as a schoolboy was remarkable. He scorned to read books

written specially for children, but used to enjoy the reading of

classical writers even at the age of seven or eight years, and his

knowledge of all Shakespeare's dramas was astonishingly complete."

But he was restless and roving rather than sedentary. He was

capable of running great physical risks and enduring hardships

beyond his strength; he travelled as much as he could, and had the

authorities admitted him into the Army, he would, unless his body

had given out, have made a good soldier. He did not mistake

books for life; but one had the feeling that life to him was

primarily a great book. His nature was emotional enough: he

fell in love; he was deeply attached to a few intimate friends; and

there was an emotional element in his politics and his reactions to

all the strange spectacles he saw in his last years of life.

But ordinarily what one thought of was his curiosity rather than his

emotions; his senses not at all. If at one moment one had

peeped into his affectionate nature the next one was always carried

off into some "objective" discussion. His curiosity about

things, his love of debate, gave him a refuge during trouble and an

habitual resort in ordinary times. He seemed incapable of any

idle thing. Most of us, with varying frequency, will make

physical exertions without obtaining or desiring reward beyond the

effort and the fatigue; or we will lie lapped in the gratification

of our senses, happy, without added occupation, to drink wine or sit

in silence with a friend and tobacco, or encumber a beach and feel

the hot sun on our faces, or loll in a green shade without even a

green thought. Or we will travel and see men and countries, or

take part in events for the mere exhilaration of doing it. But

whatever his physical activity, Julius West would always have been

the curious spectator, observing and learning, recording and

deducing, with history in the making around him; and, whatever his

physical inactivity, his brain would never have been asleep, or his

senses dormant. If one walked with him, there were few

silences; a punt on the river with him would have meant (unless he

were reading) eager, peering eyes and speculations either about the

surrounding objects, and what people had said about them, or else

about Burke, Bakunin or some such thing. For all his energy, I

never knew his ambition, or was clearly convinced that he had any

other ambition than to see and learn all he could, and produce his

results.

He attempted all sorts of literary work; parodies, short

stories, criticism. It was to be expected that the criticism

would be chiefly concerned with doctrine, and that the other work

would be defective and full of ideas. Partly, I suppose, all

this writing was the by-product of an intellectual organ which could

not stop working but demanded a change of work; partly his very

curiosity operated: he saw what other men had written, and he wanted

to find out what it would be like to write this, that and the other

thing. But he had neither the sensuousness nor the selfishness

(if that hard word may be used of that detachment and that

preoccupation) of the artist, nor the reverence for form that

demands and justifies an intense application to general detail which

is not, to the hasty eye, very significant. As a rule he was

exclusively preoccupied with the general purport of what he wanted

to say. But it was not unnatural that a young man with his

heart, his imaginative intelligence and his wide reading, should

have begun his career as an author with a book of poems. (The book

published by Mr. David Nutt in 1913 was called Atlantis and Other

Poems.) It was ignored by the reviewers and the public; he

would not have denied that it deserved to be; but it was very

interesting to any one interested in him. A great part of it

(remember, most of the verses had been written by a boy under

twenty-one) was very weak; short poems about mermaids, sunken

galleons, maidens, dreams, ghosts and witches, written in rhythms

which are lame, but displaying in the ineffective variety of their

form the restless ingenuity, the hunger for experiment of this young

author; and here and there lit up by a precocious thought or phrase.

A man with a greater share of the poetic craft was likely to do

better with a larger subject and a looser structure, and much the

best poem in West's book is Atlantis, a narrative in about

five hundred lines of blank verse, with a few songs embedded in it.

The blank verse is as good as most; few men of West's age could

write better; and he could without contortion move in it, and make

it say whatever he wanted it to say. He represents the Lost

Continent as dwindled to a small island and inhabited by people

conscious of their impending doom, weighed down with the memory of

what their country's forests and fields and birds were like before

the last wave. The subject offered an obvious chance as a

visible spectacle, and the poet (feeling this) made an attempt to

paint the features of the city, describing its houses and temples

and festivals. The attempt was unsuccessful; it was when he

reached more congenial ground that West showed his originality and

his power. With one of the most alluringly "picturesque" and

melodramatic subjects in the world under consideration, he put all

the obvious things behind him and spent his time considering what

effects such a situation as that of the doomed remnant of Atlanteans

would have had upon the minds of men. Passionate love became

almost extinct:

|

and 'twas thought 'twas well

No helpless childish hands there were to pull

Their elders' heartstrings, making death seem hard

And parting very bitter, and the end

A bitter draft of pain, poured by a hand

Unpitying, a draft of which the old

Were doomed to drink more than a double share. |

The poets

|

Did all but cease th' eternal themes to

sing

And in their place sang songs about the End. |

The philosophers ran to strange doctrines about the perfectibility

of the survivors from the next deluge or starkly expounded the End,

or were

|

Buffoons who sought to turn the End a

thing

For jest; |

and across the city sometimes flashed a band of fanatics proclaiming

this shadowed life to be an illusion from which those who had

courage and faith could escape. Voices spoke, sad or

resentful, of men cheated out of their due years; one fierce

|

For us an aimless life, an aimless Death

. . .

That I should have the power for once to live,

To be a creature strong with power to kill,

To stay, but for a little while, the strength

That hems us in! That I might taste the joy

Of conflict with an equal force to mine,

Conflict of life and death, not purposeless,

Not vain, as we now feebly struggle on. . . .

That I could have the gift of knowing hate,

Black hate that animates before it kills. . . .

O, to do aught with force, not rest supine. |

In this boyish poem we can see West's mind trying to realize

Atlantis as a whole community, where characters vary and doctrines

clash; as a vessel holding, at a certain position in time and space,

the human spirit.

Whether he would have written more poetry I do not know.

I doubt it; at all events he had little time and many distractions,

and he looked like growing confirmed in other pursuits. In

1913 he went into the office of the New Statesman, for which,

intermittently, he wrote reviews (usually of books about Eastern

Europe) and miscellaneous articles until he died. He remained

in the office for a few months; then left, and became a free lance

writing for various papers, lecturing, and starting work on the

present book and others. I think his second publication was a

tract, notable for its sagacity and its wit, on John Stuart Mill.

He was busy with several books when the war broke out, which in the

end was to kill him at twenty-seven.

I forget if it was in August, 1914, that he first tried to

join the Army. A layman might have supposed that both his eyes

and his lungs were too weak, but a doctor told him that he was good

for active service. Whenever it was that he volunteered—his

first attempt was early, and there were others after his short visit

to Russia and Warsaw in 1914-15—he made a discovery. He had

not realized—if he had ever known it the conception had dropped out

of his mental foreground—that he was not a British subject.

But they told him so, and said that his status must be settled

before he could have a commission. He had arguments: his

parents were Russian subjects and he himself was born in Russia; but

his parents were merely visiting Russia when he was born, and he

submitted that he was at that time really domiciled in England.

The argument, it seemed, had no legal validity; and, denied

citizenship in the only home he knew or wanted, he at once went,

very set and intent, to a solicitor's office in Lincoln's Inn Fields

where I had the odd experience of assisting, as I believed, to

naturalize a man I had never thought of as a foreigner. This,

he thought, would settle it; he would soon be in the Army. But

no. The hierarchy at this point thought of something new.

He was a Russian, an Ally of military age; if he wished to fight he

must join the Russian army; we would not naturalize him here.

It would have been difficult to conceive a more grotesque

suggestion, if one knew the man. He had left Russia when a

baby in long clothes; he spoke Russian (at that time) with

difficulty; he looked at Russia and her institutions from an English

point of view; he was married (he had been confirmed in the Church

of England) to the daughter of an English clergyman; all his friends

were English and most of them in uniform and it was suggested that

if he really desired to serve the Allied cause he should divest

himself of all his ties and go off to mess in the snows of Courland

or Galicia with bearded strangers from the Urals and the Ukraine.

The suggestion was repulsive to him, quite apart from the fact that

it might mean years of unbroken exile. He was, however,

allowed to join an ambulance corps in London.

Before long he was off to Petrograd on a flying tour as a

correspondent; thence to Moscow and Warsaw, within sound of which

the German guns were booming: Russian Warsaw with enemy aeroplanes

overhead and expensive Tsarist officers revelling in the best

hotels. He saw the Grand Duke Nicholas on November 17, 1914,

in the greatest Cathedral of Petrograd at a gorgeous service of

commemoration of the miraculous preservation of the Tsar Alexander

II: that was six years ago! He returned, and for a year and

more was in England, editing Everyman and writing books at a

great pace. Then his wife died. Another opportunity of

going to Russia offered, and a man always restless took it as a

means of escape from himself. He was in Petrograd in the early

months of the Bolshevik regime. He lived (a few letters came

through) in a state of high excitement, seeing everything he could,

visiting the Institute and the Bolshevik law courts, attending

meetings at which Lenin and Trotsky spoke, dogged everywhere, for he

was suspected, daily expecting to be shot from behind. Being a

democrat and a believer in ordered progress he was very angry with

the Bolsheviks; having a zest for queer manifestations of life he

found an immense variety of interest and amusement in their conduct.

When he returned he was full of stories of rascality. Lenin,

on the point of character, was in many ways an exception; but he was

tricked wholesale by German Jew agents disguised as Bolsheviks.

One of them, high in the Bolshevik Foreign Office, had even

judiciously edited the Secret Treaties, the publication of which so

edified the Bolshevik public and so surprised the world. Daily

great stacks of documents were served out to the Bolshevik press, a

dole for this paper, a dole for that; but the busy German spy had

taken the last precaution to ensure that the documents which

involved the Allies should come out, and that those which most

seriously compromised Germany should not. West became pretty

familiar with many of the revolutionary figures, and enjoyed working

in such an extraordinary scene. But he recognized that his

excitement was hectic and bad for him; he suffered to some extent

from the famine conditions of Petrograd; the cold was terrible, and

that and the indoor stuffiness which it led to affected his chest.

He had to get away. In February, 1918, he left with a party of

English governesses and elderly invalids. He was not an old

man nor a governess; he was in effect an English journalist of

fighting age who might be carrying valuable information; but he was

fortified with some lie or other, and with the rest of the pathetic

caravan he went over the ice and through the German lines. The

enemy were at that time in occupation of the Aland Islands, and West

told a romantic story of the night he and his companions spent in a

village there guarded by the German soldiers: a night filled with

snow, a silence broken by guttural voices talking of home and the

fortunes of the war in Flanders.

He got through to Stockholm and from there home, where,

unexpected and unannounced he floated in on me, keen and volatile as

ever, but looking ill. He ought then to have taken a long

rest; but he was asked to go off to Switzerland—then a hotbed of

enemy and pacifist intrigue—and he thought that with his experience

and his knowledge of languages (he now knew Russian, French, German,

Dutch, and Roumanian) it was his duty to go. But it killed

him. He came back, hollow-eyed and coughing, and went first to

an hotel in Surrey, and then to a sanatorium in the Mendips.

His friends did not know how ill he was; he wrote cheerfully about

books and politics, asked for more books, was glad he had found an

invalid officer or two with cultivated tastes. But he just saw

the war out. A complication of influenza and pneumonia

developed, and he died.

During the war he had published several books. Two—Soldiers

of the Tsar and The Fountain—were issued by the Iris

Publishing Company, the proprietor of which, now dead, deserves a

book to himself. The first was a collection of sketches

written mostly in Russia in 1914; the second a tumultuous race of

satires and parodies probably modelled on Caliban's Guide to

Letters. The agèd Reginald at the end observes:

And oh, my children, be not afraid of your own

imaginations. Once in the distant ages before our universe was

born, when Time was an unmarked desert, and God was lonely, He let

the fountain of His fancies Play, and life began. Be you, too,

creators, for there is none, even among my own grandchildren, who

has not in him a vestige of that impulse which made the earth.

The book was written on this principle; perhaps the fountain played

too fast; but its many-coloured spray shows how various was the

manipulator's knowledge and how active his mind. The other

books were G. K. Chesterton: a Critical Study (Seeker), an

abridged translation of the de Goncourt Journal, published by

Nelson's, and translations of three plays by Tchekoff and one by

Andreieff. The translation from the Goncourts, produced at a

great pace, is really good: lively, vivid, idiomatic. The

monograph, though independent and containing plenty of reservations,

was an exposition of the theory that Mr. Chesterton "is a great and

courageous thinker." West, though not blind to his subject's

genius as artist and humorist, characteristically concentrated on

his opinions about religion and politics; his own were revealed

en passant. "The dialogues on religion contained in The

Ball and the Cross are alone enough and more than enough to

place it among the few books on religion which could safely be

placed in the hands of an atheist or an agnostic with an

intelligence." Magic and Orthodoxy together "are

a great work, striking at the roots of disbelief." During the

war "those of us who had not the fortune to escape the Press by

service abroad, especially those of us who derived our living from

it, came to loathe its misrepresentation of the English people. . .

. Then we came to realize, as never before, the value of such men as

Chesterton." It was an impulsive book, but there was a great

deal of very acute analysis in it. The one book, however,