|

|

|

WILLIAM JAMES LINTON

Chartist, Republican and Wood Engraver

(1812-97) |

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

by

Kineton Parkes, 1891.

Mr. WILLIAM JAMES LINTON

was born in London on December the 7th, 1812, and was educated at a

school at Stratford, Essex, conducted by the Reverend Dr. Burford.

When he was sixteen he became a pupil of G. W. Bonner, a well-known engraver on wood, residing in Kennington Road, and to whom he was apprenticed.

During the years of his apprenticeship were sown those seeds of liberty which were just then freely floating in the air, which afterwards resulted in the voluminous writings on social subjects, which form so considerable a portion of his work in literature.

His was a large nature, and the art of engraving was never a mere profession with him, but part of his life, just as was his love of liberty and of poetry.

On the conclusion of his apprenticeship he became a professional wood engraver, subsequently joining Orrin Smith in Judd St., Brunswick Square.

When, in 1842, The Illustrated London News was started, Linton and Smith engraved much important work for that journal. In this year he was editing

The Odd Fellow, a magazine of politics and general literature, which was afterwards called

The Fireside Journal. A few months before Orrin Smith's sudden death, the partners removed to No. 85 Hatton Garden, and these premises were retained by

Mr. Linton for several years.

It was here that many of the most revolutionary spirits of that excited time were wont to congregate, and from this address several of

Mr. Linton's early publications were issued.

About the year 1838 Mr. Linton became acquainted with James Watson, the celebrated publisher of Queen's Head Passage, Paternoster Row, with whom he was on terms of friendship until his death, and also with Hetherington, Cleave, and other leaders of the extreme Radical and Chartist parties.

Contact with such men as these fired the young artist's blood, and he threw himself into the struggle with all the impetuosity of his fervent nature.

In appearance he was animated and handsome, with bright eyes and long auburn hair.

He was generous with his time and talents, and open-handed with his money, and whenever a young reformer, or propagandist, was in want of an illustration for a tract or pamphlet, the engraver-poet was ready with a design, which he drew and engraved gratuitously.

All the circulars of the "Garibaldi Fund" were designed and engraved by him. He was always a friend of the "Friends of Italy."

Even at this early period his reputation as an engraver was spreading over England and America, and his faculty of design was as great as his facility with the graver.

When the outbreak of Frost, Jones, and Williams occurred, and these three men were condemned to death for high treason,

Mr. Linton was among the first of those who came forward to prepare the monster petition which resulted in the commutation of the sentence.

In 1841 he was intimately associated with Mazzini, and assisted him in bringing before the notice of Parliament the proceedings of Sir James Graham, who had caused letters to Mazzini and other exiles in England to be opened, and one of the results of which as the judicial murder by the Austrian Government of the brothers Bandiera.

The case was taken up from Mazzini and Linton by James Stanfield and T.

S. Duncombe, who brought it forward in the House of Commons. From his time forward

Mr. Linton's relations with Mazzini and other Italian refugees were of an intimate nature.

He was also connected with W. J. Fox and his party. In 1848 he was the deputy selected by the English workmen to carry their congratulatory address to their French brethren, on establishment of the first Provincial Government.

The first of the series of publications which Mr. Linton issued from time to time was

The National, a Library for the People, which was published by James Watson in 1839.

It was a kind of miscellany consisting of extracts from writers of liberal views, with comments by

Mr. Linton, who also supplied original articles.

It ran to twenty-four numbers, forming a single volume, each number containing an engraving.

In 1845 a remarkable book appeared called "Bob Thin." This was a satire on the then existing state of things; a state, moral and material, which dwellers in the social atmosphere of to-day find it difficult to realise, so dark was it.

Whatever the shortcomings of the present time may be, the efforts of men of the stamp of the band of reformers of half a century ago have not been wasted.

The good they did is still with us, while there still remains a field full wide for those who would follow in their steps.

"Bob Thin" was chiefly directed against the Poor Laws, and was exhibited in the life of a pauper: it was written in doggerel verse and appeared as "Twenty-six Cuts at the Times" in the pages of

The People's Review, the first sixpenny review that ever appeared, and for which

Mr. Linton designed and engraved the title, and engraved also a portrait head of Milton, which adorns the cover.

"Bob Thin" was first printed in 1845 for private circulation. It had a number of small woodcuts down the sides of the pages, which were drawn and engraved by

Mr. Linton.

In The People's Review these "Twenty-six Cuts at the Times," appear as being "furnished by BOB THIN, forming an Illustrated Alphabet for all those Little Politicians who have not yet learned their Letters, with a Preface, but no Wrapper."

The preface I quote, for apart from the explanation it offers of the "Cuts" and verses which follow it, there is a prophetic ring about it, which seems to announce the whimsical rhymes of certain celebrated librettos of to-day:—

|

Most sort of stories may be made of any raw material:

So we commence to improvise an Alphabetic serial.

Our Letters were not ordered, but came to us accidentally:

May the text be found as useful as the cuts look ornamentally. |

The original title of the privately printed brochure was, "Bob Thin, or the Poor House Fugitive." The editorship of The Illuminated Magazine passed into the hands of

Mr. Linton, in this year, from those of Douglas Jerrold.

About 1846, Mr. Linton advertised "A Store of Children's Books," as being written and illustrated by "Mr. C. Honeysuckle," to be had from 85 Hatton Garden.

The Mr. C. Honeysuckle was Mr. Linton himself, and these books, which were chiefly devoted to flowers, were all coloured and drawn with a careful feeling for nature, the author's contention being that children ought never to look upon any representation of a living thing that was not perfectly true to its prototype in nature.

In those days, drawings of the crudest character were considered good enough for children.

These books were utterly unlike anything which had then appeared, and there has not been since any which surpass them.

In 1848, Mr. Linton conceived the idea of bringing out a paper in the Isle of Man, which had then the privilege of free postage.

This was called The Cause of the People, and was a well-printed quarto on fine thick paper which bore the impress of taste.

It was the first publication of a political nature which had been produced in such a style.

The designs in it were furnished by Mr. Linton, and the arrangement of the paper was his.

He wrote occasionally under the name of "Spartacus;" and contributed "petitions" almost every Week, which were remarkable for their relevance, brevity, and logical force.

Mr. G. J. Holyoake was also associated with this enterprise.

In 1850, one of the most notable of all the journalistic enterprises of the century,

The Leader, made its appearance. This celebrated weekly newspaper was projected by Thornton Hunt and

Mr. Linton, with whom was closely associated George Henry Lewes.

When Mr. Linton devoted his energies to this matter, it was with the hope and intention of establishing a paper which should be at once the organ and nucleus of a republican party in England, and be open also for truthful accounts of republican views and republican doings throughout Europe.

A department of the paper was allotted to Mr. Linton, but his writings were "edited" by the editor-in-chief, Thornton Hunt.

He found that Hunt and Lewes were not what he considered true republicans, and that while they were willing enough to make use of him and his connection with Mazzini and the Polish Republican party, they were not willing that he should go the lengths he desired in his own department of the paper.

In the prospectus of the journal it was announced that among other reforms it would advocate "the full exercise of the Franchise'' and "Free Trade," and with these aims

Mr. Linton was in accord.

There were, however, other matters of equal importance, which his colleagues would not touch, and he was consequently compelled to sever himself from these connections, and to strive to stand alone on his own ground and to fight his combat single-handed.

With this object in view he started The English

Republic. The first number appeared at the beginning of 1851.

The contents were mostly written by Mr. Linton himself, but he also included papers from other pens, including those of Alexander Herzen, Charles Stolzman, Wendell Phillips, and Joseph Mazzini, and was helped considerably by

Mr. Joseph Cowen. Mr. Linton's own contributions were both in prose and in verse, exclusively of a political or social character, and mainly dealing with republican matters.

On these subjects, also, he included articles by Mazzini and others which had appeared elsewhere, but which helped him in his purpose, as well as passages, sometimes of considerable length, from books he regarded as standard works on republicanism, and articles he had himself contributed to a periodical published in 1850, called

The Red Republican, edited by Mr. G. J. Harvey [sic]. Everything, both in prose and verse, which has not the author's name appended, was written by

Mr. Linton.

There were four volumes of The English Republic printed. The title page of volume the first was as follows:

THE

ENGLISH REPUBLIC:

GOD AND THE PEOPLE.

Then came the unfurled flag of the Republicans, the standard of which appears strongly planted in the rock, and the flag itself with the colours blue, white and green, reaches to the clouds.

EDITED

BY

W. J. LINTON.

LONDON:

J. WATSON, QUEEN'S HEAD PASSAGE, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1851.

This volume opens with an address dated December, 1850, in which after briefly commenting upon the state of the Government of the time, the editor remarks that in his venture "there will be at least a known centre and a voice "for the Republican Party in England; and he continues, "it will be for the members of the party themselves to determine how far they use it," and concludes by saying: "Such counsel and service as from time to time I may be able to offer shall not be wanting."

|

'The profit

of a swindling trade is not property. Is it not swindling when a young

child is taken in at a factory, and receives—in exchange for childhood's

beauty, youth's hope, manhood's glorious strength, and the calm sunset of

a well-aged life—some paltry shillings a week? Nay, we will not wrong

you, trader! That is not all you give him. You also give him ignorance

and vice, and suffering, and emaciation, a crippled beggardly life and a

miserable death, in exchange for the health and joy of which God had made

him capable.'

From 'The English

Republic.' |

With volume the second, a fresh system of publication was adopted, and

The Republic was styled "A Series of Tracts." The volume includes the years 1852 and 1853, and contains a hundred tracts—the first dated January lst, 1852, and the last November 26th, 1853.

These two volumes were printed at Leeds. In 1854 more extensive changes were made.

It was now called "A Newspaper and Review," and "edited by W. J. Linton, and published by him at Brantwood, Coniston, Windermere, Westmoreland," and the motto is changed from "God and the People" to "The Formation of a Nation is a Religion," from Mazzini.

Volume the third runs through the year 1854; in 1855 we find only an incomplete volume, which extends from January to April the 15th, when the editor makes "a conclusion."

He styles himself "a political Jeremiah," and says that the "response is not sufficient to justify further continuance of 'his' endeavour, at all events, in the present manner;" and concludes the whole series as follows:—"So ends the task I undertook some years ago.

I am yet ready to bear my part in the future's work."

At Brantwood Mr. Linton had set up a private press, from which he issued other things besides

The Republic. In 1866, before going to America, Mr. Linton sold Brantwood to

Mr. Ruskin.

|

|

|

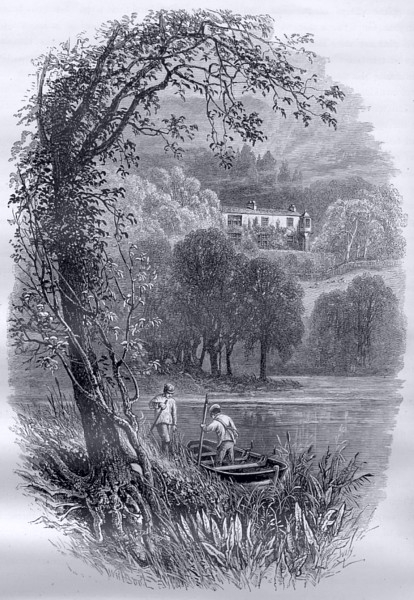

"Brantwood" on Lake Coniston.

Besides being Linton's home, Brantwood was also home

to Gerald Massey and to John

Ruskin. Ruskin moved to Brantwood in 1872 and died there in

1900; the house is now a museum to him.

(Print taken from Picturesque Europe, Appleton

& Co., New York, 1875.) |

There were only some three hundred copies of each issue of

The English Republic printed, a certain number of which were sold by James Watson, and some were sent to

Mr. Cowen at

Newcastle-on-Tyne, and the rest were given away. The complete set is now a great rarity, and I have not been able to obtain a copy for the purposes of this edition in spite of much advertising.

Of course, the venture did not pay expenses, but that could hardly be expected, when the edition was so limited, and the sale more limited still.

However this may be, its work was accomplished, its object achieved, and an exposition of Republicanism given to the class for whom it was designed.

In this its projector was not disappointed, and, in spite of the lapse of forty years, his opinions remain unchanged; and although Republican England is still something lacking achievement, his confidence in the principles he laid down then is unshaken.

Mr. Linton holds that what a man prints or says deliberately in public is no longer his, but belongs to the world, especially when he ventures to assume the office of teacher.

Though there is much he would wish bettered in its expression, there is nothing he has written during a literary life of more than half a century that he would recant; nothing he would recall except its (as he chooses to regard it) poorness of accomplishment.

During that half century he has not changed his peculiar opinions concerning things and men, and he does not live in any expectation of seeing the realisation of his younger hopes; but he does live in the sure hope that his aspirations will be realised in the future, whether it be near or far.

Thinking thuswise, Mr. Linton has kindly given his permission to me to reprint such of the essays as I thought desirable, and such as would be useful at the present hour, as contributions to the discussion of the social question which is ever with us, and which, in its main details, differs but little from what it was in the time of the original publication of

The English Republic. How well Mr. Linton's contributions to the subject apply to-day is to be gleaned by even a hasty perusal of the following pages, but how much they contribute to the solution of the difficulty will be revealed to the more careful reader and student.

The essays I have selected will give a very adequate idea of the scope of the original

English Republic.

We have seen briefly what was the origin and occasion of the work; we have yet to learn the principles which underlie what is written hereafter.

In 1867, Mr. Linton published at New York a brochure, entitled, "Ireland for the Irish, Rhymes and Reasons against Landlordism, with a Preface on Fenianism and Republicanism." In this preface

Mr. Linton gives an admirable definition of what he considered Republicanism to consist in, and I have ventured to quote from this at length as it throws much light upon his work in

The English Republic.

He says by the Republic:—

We mean not only the displacement of a particular form of government; but, believing that presidents are but slightly improved constitutional sovereigns, we mean the abolition of class government, which is monarchy, under whatever name. We mean not merely giving the land to the people, and enfranchising them from their thraldom under the priesthood; we mean not only this or that remedial measure, however just or needful; but we mean a radical reorganisation of government and of society, a reorganisation which shall pervade all ranks and conditions of men, a reorganisation whose principles we accept as a faith, defend with our reason, and date to maintain and promote with our lives.

"By the one word REPUBLIC we mean the equal right of all men to well-being and well-doing, and the ordering of all the powers and capabilities of society for the bettering of every member toward the perfecting of the whole.

"We mean that there shall be none uneducated, none without property, none shut out, by legislative enactment or social hindrance, from the people's land, or from whatever the commonwealth can furnish for their spiritual and material advantage.

"We mean the abolition of the tyrannies of rank and wealth, the abolition of all arbitrary distinctions and artificial disabilities calculated to prevent any individual from reaching the fullest growth and perfection of his or her nature. We mean the protection of the weak against the strong. We mean the assurance of every member of society against tyranny or accident. We mean the equal care of State embracing every individual as a part of the whole.

"We mean also that the State should maintain its rights to the service of all its members. We mean that each should be dutiful to all. We mean that duty shall be no more a vague or an idle word; that it shall really express the relation of the parts to the whole, the relation by which a man or a woman becomes the servant of the actual time or the surrounding society—of family, of country, of the world—bound to help to the utmost in the progressions of Humanity, with no limits except the possibilities of the individual's particular sphere.

"We mean by The Republic a form of government in which all may participate; a government not to be surrendered to rulers or ' representatives,' but to be directly exercised by the people themselves, originating, discussing, and enacting their own laws, deputing only their officers to carry out the popular will, the expression of the people's intellect and conscience.

"We mean also by that word Republic to express the connection not only between the State and the individual, but between States or nations, and the community of nations—the whole of Humanity. We mean that, as individuals are component parts of the State or body politic, so State or nation are component parts of the Universal Republic, the body politic of Humanity, bound in duty toward that, and entitled to the protection of that against all interference or encroachment.

"We mean by that word Republic the oneness of Humanity, the equality of all peoples and of all the people. We mean that there is one common object and purpose in all times and among all races of mankind, the progress from improvement to improvement, through successive discoveries and applications of the laws of human life, of which law the whole people, and no priestly class whatever, are the interpreters; and that it is the duty of every human being to aid in this progress.

"This is our meaning of the word REPUBLIC!"

This extract serves admirably as a preface to the present volume, which treats in detail of the principle here defined so tersely.

In the essays which follow will be found a fairly complete exposition of Republicanism.

The order in which they are here placed is not the same as that in which they occur in the original volumes, but sequence was not so urgent a necessity in a serial publication as it becomes in a volume purporting to treat of a single subject in its various aspects.

The order I have adopted is the best that could be decided upon, any other arrangement of the material at my command being impossible, by some reason or another.

It will be found that there are "faults" in the strata, as the geologist would express it; abrupt terminations of one line or argument, and the commencement of another, but this is neither the fault of the author nor of his editor, but of the nature of the subjects treated.

It was impossible to give separate chapters to each separate subject (if this had been done some of the chapters would have consisted of a couple of pages), so the materials have been welded as carefully as their natures admitted; and if the consistency of one or two of the chapters is a trifle varied in its composition, this explanation, it is hoped, will be found sufficient to account for it.

About the time when The English Republic was

first projected, Mr. Linton had left London and was residing near to Whitehaven, at Ravenglass,

to which address he had invited, in The Red Republican, all his

sympathisers to write to him, the result of which invitation was the formation

of various societies throughout the country, for the propagation of the principles

he professed. From Ravenglass his woodblocks were sent up to town at short

intervals. Subsequently he removed to the estate at Coniston, called Brantwood. Here the second and third volumes of the Republic were

printed, as well as The Northern Tribune, a journal in which he was again

associated with Mr. Joseph Cowen, and some privately printed books, and here he

carried on his wood engraving as before. I am not sure whether "The Plaint

of Freedom," the poem which Landor praised enthusiastically, and which was issued

anonymously by Mr. Linton, was done at Brantwood, but I fancy it belongs to the year

before he went there. The title-page bears the date 1852.

At his house at Coniston he received his exiled and refugee friends, and Colonel Stolzman, a Pole, who fought under the first Napoleon, resided with him for some years, and died here.

All men of republican tendencies were welcomed there, as at Hatton Garden he had welcomed Stanislaus Worzell, the Polish banker, who had a pension from the English Government as an exile, in Lord Dudley Stuart's days, and Alexander Herzen, the exiled but rich Russian who wrote a book dealing with the condition of Russia, which was very much noticed and spoken of at the time.

In 1854, Mr. Linton wrote and illustrated a book called "The Ferns of the English Lake Country."

|

|

|

Eliza Lynn Linton

(1822-98) |

In 1855, Mr. H. D. Linton, a younger brother of Mr. W. J. Linton, and his friend M. Edmond Morin, devised a new illustrated paper to be called

Pen and Pencil. Morin furnished the money and contributed most of the drawings;

Mr. H. D. Linton did the engraving (he had studied engraving with his brother and Orrin Smith);

while Mr. W. J. Linton edited the journal in conjunction with Mr. Macrae Moir.

After about eight numbers Pen and Pencil succumbed to scarcity of capital.

About this time and onwards Mr. W. J. Linton was a constant contributor to

The Nation, while it was edited by Duffy. Some of his contributions, however, were too fiery even for the Irish Duffy and the Irish Nation.

He was also a contributor to The Westminster Review, The

Examiner, The Spectator, and other journals.

In 1858, he married a second time. His second wife being a daughter of the Rev. J. Lynn of Crosthwaite, in Cumberland, Eliza Lynn, who is well-known now as Mrs. Lynn Linton.

In 1860, his "History of Wood Engraving" was published, and five years after, his first volume of verse called "Claribel, and other Poems," and this volume is the pivot of his career.

1865 is the middle of his literary life, and henceforth we find more time given to poetry and engraving than to politics and society.

The strenuous efforts of his earlier years were succeeded by a calmer period, though not a less prolific one.

In 1866 he left England and went to reside in America.

In April the following year, "Ireland for the Irish," to which I have previously referred, and from the preface of which I have quoted, was written in New York and published there; this year also saw the production of "Wind-Falls" from his recently acquired printing-press. It is a collection of about two hundred "extracts from imaginary plays."

For a long period there is a lull, while he confined himself very largely to his engraving; in 1878, he issued a work called "The Poetry of America." The following year saw the appearance of three volumes, a life of his old friend and publisher, James Watson, of which he privately printed fifty copies; a "Life of Thomas Paine," and "Practical Hints on Wood Engraving."

In 1880, Mr. Abel Heywood of Manchester reprinted his life of Watson.

In 1881, he published a volume of "Translations from Victor Huo and Beranger;" in 1882, he issued "Golden Apples of Hesperus," an anthology printed at his private press, called the Appledore Press, at New Haven, Connecticut, seventy-four miles from New York; "Rare Poems of the 16th and 17th Centuries" and a "History

of Wood Engraving in America." In 1883, he edited, in conjunction

with Mr. R. H. Stoddard, "English Verse" in five volumes, and in this and the following year he visited England, and worked at the British Museum at researches in the history of Wood Engraving. In 1886, "In Dispraise of a Woman" was printed, but only twenty-five copies; it is a curious book.

"Love-Lore" followed in 1887, and in this volume some of his finest verse is to be found.

"Famine, a Masque," is, I believe, to be ascribed to 1888; 1889 yielded "Poems and Translations," being a selection from his Poetical Works; and 1890, the magnificent and monumental work, "Masters of Wood Engraving."

And thus ends the other twenty-five years of incessant literary and artistic activity, years which would make the lifetime of many another man.

In our present connection, we are concerned more with his earlier period, but it cannot be uninteresting to follow up till today such a career.

Mr. Linton is now enjoying excellent health and strength at his home at New Haven, and he writes me from there to give his consent to the republication of his work done in the early eighteen-fifties.

In conclusion, I have to render my sincere and hearty

thanks to Mr. E. W. Badger, Dr. Chapman, Mr. Joseph Cowen, M.P.,

Mr. G. J.

Holyoake, Mr. F. G. Kitton, Dr. J. A. Langford, Mrs. E. Lynn

Linton, and to Mr. H. D. Linton, for important particulars

concerning the career of Mr. W. J. Linton.

KINETON PARKES. Birmingham.

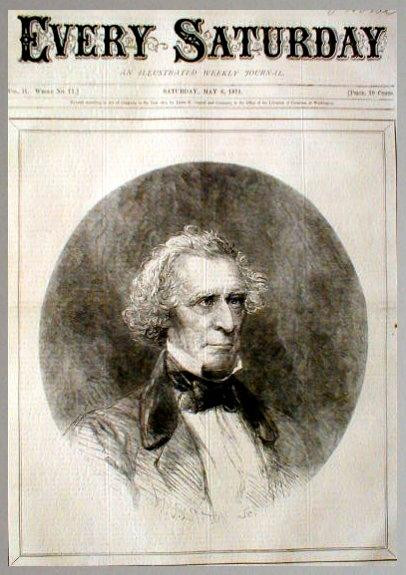

James Gordon Bennett,

Editor of The New York Herald.

An engraving by W. J. Linton.

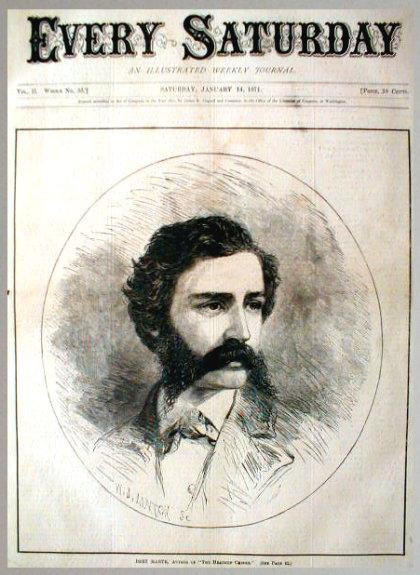

Author Bret Harte.

An engraving by W. J. Linton. |