|

|

|

(1832-1906)

Chartist, Republican, supporter of women's

suffrage

and Editor of the

Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. |

Other than his newspaper

articles and pamphlets — not without influence in their time — Adams'

importance rests on two books, particularly on the second of these,

his autobiography. In

"Memoirs of a Social Atom" (1903), Adams leaves to posterity a very readable

and informative account of the lives of the working class during the early

and central decades of the Victorian era together with his perspective on the radical personalities — both British and

European — who were then active. "Our American Cousins" is a now

dated but nevertheless interesting record of his impressions of the

U.S.A. gained during a visit there in 1882.

Chartist, Republican, supporter of women's

suffrage, and long-time distinguished Editor of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle,

WILLIAM EDWIN ADAMS

was born at Cheltenham, Gloucester, on 11

February, 1832 to poor, working-class parents. In common with

most other of the authors and poets whose literary outputs are

republished on

this website, Adams was mostly self-educated.

What schooling he received was sporadic, Sunday School*

contributing to what little formal education could be had from 'dame

schools' and similar institutions. He learned to read and write, but

little else—according to Adams, "It was not much of an education, but

it sufficed. It supplied me at any rate with the tools of knowledge." Later in life Adams attended Working Men's Colleges in Manchester and in London.

Adams' first contact with the newspaper industry was at the age of

fourteen, when

he was apprenticed to the proprietor of the Cheltenham Journal. During his

seven years apprenticeship he

became involved in the radical politics of the age—an interest that

ran in his family—both

attending and participating actively in Chartist meetings, while doing

what he could to improve his education by reading, and attending lectures

and debates.

In 1854,

Adams, by now a journeyman printer, removed to "Brantwood", on Lake

Coniston (later the home of Gerald Massey

and John Ruskin), to assist W. J. Linton in the production of his radical

publication, The English

Republic. About this episode Linton had the following to say,

although he doesn't refer to his

three

"zealous and efficient helpers" by name—Thomas Hailing and James Glover being the other

two—presumably on account of their not being "among the candidates for

notoriety"....

"...the

Republic was issued in four-page weekly tracts, bound together for

monthly parts, still printed at Leeds. In the spring of 1852 I removed to

Brantwood, and in 1854 resumed the monthly issue, by then having printing

press and types, and registering myself as a printer, without which my

printing material was liable to seizure and confiscation by the

authorities. At Brantwood I had the assistance of three young men from

Cheltenham, who came across the country to offer themselves at my service,

at any wage that I could afford them. Two were printers, and the third

was a gardener. They were zealous and efficient helpers. When, in April,

1855, I had to give up the endeavour (it had never reached a paying point,

and of the few hundreds printed many were distributed freely in the hope

of propagandism), my three men had to leave me: one went back to

Cheltenham, his native place, resumed printing there, and established a

printing office noteworthy for its excellent work; one found employment

for a time in London, and has now for many years been the editor of the

weekly edition of Mr. Cowen's Newcastle Chronicle; one returned to

gardening and has been long in the employment of a gentleman in the

neighbourhood of London: all fairly well doing, all to this day my

attached and esteemed friends, none ever complaining of lost time at

Brantwood. Their names, not among the candidates for notoriety, are

written on my heart."

W. J. Linton, "Memories,"

1894.

Following closure of the Republic, Adams eventually found his way

to London, where he continued his involvement in radical politics, contributing articles to Charles Bradlaugh's National Reformer,

and publishing pamphlets dealing with tyrannicide, suffrage (in response

to the abortive reform bills of 1859 and 1860), and the American

Civil War. The first of these—"Tyrannicide: is

it justifiable?" (1858)—stemmed from the attempted assassination of

the French Emperor by the Italian, Felice Orsini, who believed that

Napoleon III was the chief obstacle to Italian independence and the

principal cause of the anti-liberal reaction throughout Europe. In

it, Adams argued strongly in Orsini's defence. Due to the British connections

of the plot and to pressure from the French government, the

assassination attempt resulted in Lord Palmerston's government presenting

the Conspiracy to Murder Bill and prosecuting Edward Truelove, the publisher

of Adams' pamphlet—which had attracted considerable attention—on charges of seditious libel and incitement to

assassinate the Emperor [1]. The Bill was defeated, Palmerston resigned

and the prosecution of Truelove was eventually settled on what, to

Truelove and Adams, were highly disagreeable terms that denied them 'their

day in court' and a public airing of their views [2]. A sequel to

Adams' "Tyrannicide" pamphlet, "Bonaparte's

Challenge to Tyrannicides", was made ready for publication but had to

be suppressed through changes in the law. As Adams put it, "the

very changes in the law which were defeated in 1858 were effected at a

later date without anybody seeming to know much about it." He went on

to say "But an inexorable fate asserted itself at last. Twelve years

later the despot and usurper who had triumphed on the Boulevards

disappeared in shame and ignominy amidst the blood and smoke of Sedan."

In his

pamphlet "An Argument for Complete Suffrage" (1860), Adams wrote: "On

principle there can be only one claim of citizenship—Manhood. And

there is nothing exclusive in this—no sexual limitation" (Adams

employs "man" in its original generic sense to refer to any human

being). He

continues: "Society has no claim upon the allegiance of the voteless

workman anymore than it has a claim upon the slave—can have no claim while

his equal social rights are withheld." In "The Slaveholder's War: an Argument for the North and the Negro"

(1863), the longest pamphlet of the set, Adams refutes the claim put

forward by the South that the causes of the American civil war are

oppressive tariffs, and much of his text is a wide-ranging and closely

argued indictment of slavery.

The year 1862 found Adams with little work and

suffering much hardship as a consequence. It was at this time that he was

invited to write a weekly article for the Newcastle Chronicle by

its owner, the prominent politician and journalist Joseph Cowen, whose

attention had been attracted by Adams' columns in the National

Reformer. This was to be the start of Adams' career in newspaper

journalism proper. While

continuing to write for Bradlaugh's National Reformer under the

pen-name of "Caractacus", he joined the editorial staff of the Newcastle Daily

Chronicle, later becoming Editor of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, a

position he was to hold with distinction for 36 years until he retired in

1900.

Adams was a great admirer of the Italian patriot,

philosopher and politician, Giuseppe Mazzini, whom he regarded as

"the greatest teacher since Christ." He favoured a transatlantic

alignment, and following a visit to the U.S.A. in 1882, published his

impressions in "Our American Cousins", an account described by one critic

as "the best and most unbiased account of the great republic ever penned

by an Englishman." Adams concludes this interesting narrative thus: "Certainly

I shall not soon forget three things that came within my experience—the

wonderful courtesy of the people, the utter absence of restraint or

formality in connection with the institutions of the land, and, above all,

the amazing energy and enterprise which Americans everywhere import into

the varied affairs of life. Nevertheless, I never returned to the

old country with greater love and admiration for it than when I returned

from that Greater Britain beyond the Atlantic."

By the 1880s Adams was finding himself increasingly out

of sympathy with emerging trends in socialism [3] and he gradually withdrew from

personal political comment, although allowing space in the Chronicle

for the dissemination of contemporary arguments that he did not favour.

But while laying down his political cudgels he cultivated

other interests, such as his campaigns for free libraries and for parks for the

people. As 'Uncle Toby' he founded the 'Dicky Bird Club' for the

protection of birds, membership of which approached a quarter of a million

young people and rallies filled the Tyne Theatre. Ruskin and Tennyson

were among the celebrities who became honorary officers.

Adams' later years were affected by poor health, to

combat which he spent the English winters in the warmer climate of

Madeira. It was there that he wrote his autobiography,

"Memoirs of a Social Atom"

(originally published as a series of articles in the Newcastle Weekly

Chronicle during 1901-2, and published as a book in 1903), aptly described by the

social historian John Saville as "much superior to the

average autobiographical record, and much more useful to the historian

than most."

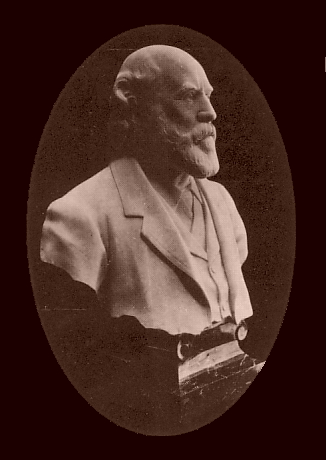

William Edwin Adams died at Funchal, Madeira, on 13 May 1906 and was buried there. On the first

anniversary of his death the marble bust pictured above was unveiled in

Newcastle Public Library by the miners' leader, Thomas Burt MP.

____________________________

FOOTNOTES:

* See John Critchley Prince, "The

Sunday School".

1.

|

The Times,

Feb 23, 1858.

PROSECUTION FOR LIBEL ON THE EMPEROR OF THE FRENCH.

─s─

At Bow-street police-court yesterday Mr. Bodkin, counsel for the

treasury, attended to conduct a prosecution against Edward Truelove,

a well dressed middle-aged man, described as a bookseller, who was

charged with having "unlawfully written and published a false,

malicious, scandalous, and seditious libel of and concerning His

majesty the Emperor of the French, with the view to incite divers

persons to assassinate his said Majesty.

Mr. Bodkin appeared for the prosecution, and Mr. Sleigh for

the defence.

The warrant having been read,

Mr. Bodkin said,—Sir, this is a case in which the Government

have thought proper to interfere. The defendant is the publisher of

a pamphlet; whether he is the author or no I cannot say, but it

purports to be written by "W. E. Adams," and is published by the

defendant at 240, Strand, at the price of 1d. It is of a

character that I cannot but designate as atrocious. It

advocates the propriety of assassination, and in terms, not, indeed,

direct, but not to be misunderstood, applies this doctrine to the

Emperor of the French. I do not wish to give any unnecessary

publicity to so scandalous a publication, and as you have already

seen the pamphlet I do not think it necessary to read it now.

Unless a remand is applied for on the other side I shall ask you to

commit the prisoner for trial at once.

The learned counsel then called—

Frederick Williamson, who deposed,—I am a detective officer.

I went on Saturday to the house of the defendant, at 240 Strand,

where he carries on business as a bookseller. I saw him and

purchased one of these pamphlets. (Witness here produced a pamphlet

in eight pages, entitled "Tyrannicide: Is it Justifiable? by

W. E. Adams.—Edward Truelove, 240, Strand.") They were 1d each.

This being the case for the prosecution.

Mr. Sleigh said,—Sir, I am only just instructed in this case,

and have had no opportunity of reading the pamphlet through, but I

cannot help saying that I look with very considerable alarm on such

proceedings on the part of the Government. We are told that

this a libel on the Emperor of the French, advocating his

assassination, but I am prepared to say—

Mr. HENRY.—If you

have not read it, Mr. Sleigh, had you better take time to do so?

I have no objection to wait while you read it.

Mr. Sleigh.—I have not had time to read it all, but I have

looked through every page, and I challenge any one to show me where

the Emperor of the French is named. I cannot help expressing

alarm at this interference—a man's shop being entered and himself

brought up in custody for a publication which does not contain any

reflection on any human being. I submit with considerable

confidence that this is not a libel. The learned counsel

proceeded to say that if the magistrate thought it was a libel, then

defendant ought to have time to prepare his defence. In that

case he should apply for a remand—defendant to be admitted to bail.

He observed that defendant was not asked by the officer whether he

knew what the pamphlet contained. This was different from the

case of Peltier, which was a personal libel.

Mr. HENRY.—So is

this. There is no doubt about it.

Mr. Bodkin.—It is not necessary that the name should be so

mentioned.

Mr. HENRY.—There

is internal evidence as clear as possible showing to whom it

alludes.

Mr. Bodkin.—To my friend's application for time I shall not

object, nor to the admission of defendant to bail in the usual

amounts; but I must ask my friend to do the Government the justice

to remember that if it was their design to be harsh they might have

indicted the defendant at once.

Mr. HENRY.—That

was the course adopted in Peltier's case.

Mr. Bodkin.—It is the usual course; but as constitutional

jealousy of that mode of proceeding has arisen it was thought right

to adopt the course which has been taken, in order that if there was

anything to be preferred in defendant's favour he might have a full

opportunity of advancing it.

Mr. Sleight could not adopt the suggestion that Government

has acted with leniency in the matter. They might have taken

out a summons instead of a warrant.

Mr. Bodkin.—We are going to have a new Government, but I hope

that no Government will know its duty so ill as to take that course

in such a case.

Defendant was then remanded, being admitted to bail in the

two sureties of £40 and his own recognizance for £100.

Mr. Sleight asked his worship to fix a lower amount of

bail—£20, for instance—as defendant was but a humble tradesman; but

Mr. HENRY

declined, and in the course of an hour bail to the amount fixed was

provided, and defendant was set at liberty. |

2.

|

The Times,

June 23, 1858.

COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH, WESTMINSTER, JUNE 21.

(Sittings at Nisi Prius, before Lord CAMPBELL

and

Special Juries.)

THE QUEEN V. TRUELOVE.

The Attorney-General, Mr. Macaulay, Q.C., Mr. Welsby, Mr.

Bodkin, and Mr. J. Clerk, appeared for the Crown; and Edwin James,

Q.C., Mr. J. Simon, Mr. Hawkins, and Mr. Sleigh for the defendant.

This was an indictment found at the Central Criminal Court,

and removed to this court by certiorari, which charged the

defendant, Edward Truelove, a bookseller, at No.210 in the Strand,

with the publication of a libel on His Imperial Majesty the Emperor

of the French, and attempting to justify the crime of assassination.

When the case was called on only nine of the special jurymen

answered to their names.

The ATTORNEY-GENERAL,

on the part of the Crown, prayed stales and, when the jurymen

were sworn, rose and said,—May it please your Lordship, and

gentlemen of the jury, I rejoice that I have to announce to you that

you will not be called upon to try this indictment. It is a

prosecution instituted by the Attorney-General of the late

Government, by reason of the publication of a pamphlet containing

certain passages tending, as it was thought, to incite evil-minded

men to the crime of assassination and murder. Gentlemen, when

I succeeded to the office which I have the honour to hold I felt it

to be my duty to adopt the act of my predecessor (the late

Attorney-General), and to carry on this prosecution. I felt it

my duty, by submitting this case to a jury of Englishmen, to

endeavour to prove that the law of England, which you sit here to

assist in administering, and the people of England, of whom you form

a part, and whom you represent, will never tolerate or endure the

dissemination of doctrines which ought to be rejected and denounced

with disapprobation and horror by every true patriot in every

country, and by every honest man throughout the world; and to

endeavour to prove also that the Sovereign of the French empire, the

firm and faithful ally of England, is as well entitled to the

protection of our laws as an English gentleman or an English Prince.

But, gentlemen, I learnt with great satisfaction from my learned

friend, Mr. James, counsel for the defendants, that his client, who

is an Englishman, and, as I am informed, a respectable English

tradesman, and the father of a large family, is ready to deny, in

terms unqualified, and without reserve, that he ever intended or

desired, directly or indirectly, to countenance or encourage the

crime of assassination, and that he is ready to express his regret

that such a construction can have been put on any publication to

which he has been a party. Gentlemen, I think this course does

honour and credit to the defendant as an Englishman, and I accept

that which I have no doubt will be fairly and frankly stated, on

behalf of his client, by my learned friend Mr. James. I

understand my learned friend is ready to offer to you and to my Lord

and to the country the assurance of what I have stated, and the

assurance likewise that the publication of this pamphlet has ceased,

and will no longer be sold by him. On that assurance it only

remains for me to perform the duty, which I perform willingly and

freely, on the part of the Crown—viz., to consent that you now

pronounce a verdict of acquittal.

Mr. EDWIN JAMES

then rose and said,—My Lord and gentlemen of the jury, I have not

the least hesitation in responding most cheerfully, on the part of

the defendant, to what has been stated by the Attorney-General.

If the case had proceeded it would have been most clear that there

was no intention, either by the writer of the pamphlet or the

publisher, to incite to assassination. So far as as he was concerned

as the publisher, it was merely a disquisition on an abstract

question, and he never intended to incite to assassination. As

to his not publishing and not selling any more of this paper, when

in the first instance, it was represented to him by myself and my

learned friends, he informed me that he feared he would be

surrendering the dearest and most valuable liberty of the press, if,

believing that no harm was intended, he entered into any engagement

not to publish any more; but we took it upon ourselves to represent

that the publication was liable to misconstruction, happening at a

time when there was a feeling of irritation between two great

nations, between whom every right-minded person trusts there will be

harmony and everlasting peace; and the defendant, Mr. Truelove,

acting under our advice that he would not be surrendering any

privilege of the press, has consented that no future publication of

the pamphlet shall take place, and that no more copies shall be

sold.

Lord CAMPBELL

said it would be the duty of the jury to find a verdict for the

defendant. If the trial had proceeded, his Lordship said he had no

doubt that, as an English jury, they would have done their duty; but

observed that in this country everyone had the most entire liberty

of commenting on the conduct not only of our own Government but of

foreign Governments and foreign rulers, provided it was done with

truth and moderation. His Lordship's voice here became scarcely

audible, but, so far as we could collect what followed, his Lordship

observed that, if the publication in question had been proved to

have the tendency imputed to it, he had no doubt the jury would have

done their duty, and found the defendant guilty. It would be a

reproach not only to the law of England, but to that of any

civilized country, if it were allowable to publish writings inciting

to assassination. The liberty of the press required no such

privilege, and such publications were an abuse of it. The learned

Attorney-General had no doubt acted in this matter with the greatest

propriety and the learned counsel who represented the defendant ha

also acted with the greatest propriety in entering into the

engagement that this publication shall no longer be sold. His

Lordship added the expression of his opinion that the publication in

question ought no longer to be circulated in this country.

The Jury then found the defendant Not Guilty, and left

the box.

|

Adams gives a complete account

of the Tyrannicide episode in his Memoirs (Chpts.

XXXV.—XXXVII).

3. Adams'

reflections on growing trade union power—see "The

Law of the Workshop"—provide an interesting description of what in the

post World War II years became known as "The British Disease", a disease

that led in turn to the "winter of discontent" of 1979 and to the trade

union reforms of the Thatcher era.

|