|

"It is said, God

made everything. I don't believe it; He never made Whitecross

Place, the entrance to which was the narrow way that leadeth into

stinks. A gutter passed through the middle of the court—a pretty

looking gutter, from which the effluvia rose up, without ceasing,

into our elegant second floor front; a room, or rather a cell (we

paid 2s. 3d. rent weekly, for the blessed privilege of breathing in

the accumulated filth below); a hole in which the bugs held a

monster public meeting every night, determined to show what a

co-operative movement could do."

JOHN

JAMES BEZER. |

|

|

|

JOHN JAMES BEZER,

CHARTIST.

(1816-88) |

|

――――♦――――

JOHN JAMES BEZER, CHARTIST

AND JOHN ARNOTT,

NATIONAL CHARTER ASSOCIATION

BY

DAVID SHAW

now on sale at

LuLu.

――――♦――――

|

JOHN JAMES

BEZER was a minor but interesting activist during

the later years of the Chartist movement. His name comes down to us,

not so much by way of references made to his lectures and the Chartist

meetings that he attended in company with the movement's more notable

personalities, but through the record of his trial for sedition and, more

particularly, for his incomplete autobiography.

Ten chapters of this were published as instalments in the Christian

Socialist, from 9 August 1851. Bezer's narrative of his

childhood and early days provide an important and incisive account of the

wretched lives suffered by London's poor during the early 1800's. He

probably intended to cover the period of his trial and subsequent

incarceration in Newgate Prison, but his autobiography ceased with the

demise of the Christian Socialist in 1851, and Bezer left the

Chartist scene in 1852.

There is little information regarding his activities other

than those given in his autobiography. However, there are reports of

his rather short-lived political pursuits in radical newspapers, as well

as items in the Christian Socialist. For what information has

been obtained, including genealogical records that have been traced, a

chronological order has been used. Further information may yet

become available. From these records, it is surprising to note how

many times he and his family moved—usually within the Clerkenwell/Shoreditch/Bethnal

Green areas. He mentioned in a letter to the Christian Socialist

(see the section 'Circulation of the Christian

Socialist') that he had had nine children up to December 1851—but

details of only eight have been traced. Probably the other child

died at an early age, and that record has so far not been found.

An autodidact as were many of the poorer class at that

time—see, for example, Gerald Massey—he

was clever, observant, a practical opportunist and had a descriptive dry

sense of humour. His early involvement with the Chartist movement

certainly provided a positive outlet for his rebellious opinions, the

result of his experience of poverty and social injustice.

Undoubtedly sincere, his participation within the Chartist organisation

and Christian Socialist movement was essentially localised, and he showed

no evidence of any wide knowledge of political complexities. Neither

did he appear to show any desire for gaining wider personal achievement

through broader experience as his later occupations show.

With regard to his personal appearance, he was blind in his

left eye (apparent in the above photo), the result of smallpox as a

child and, from later information, was of very short stature at only 5

feet. In his autobiography he

mentioned [about 1835] that he had been advised to give up shoemaking, as

it was straining his eye, but according to records, he continued the

occupation for long periods.

―――♦―――

JOHN JAMES BEZER, CHARTIST

(1816-88)

BY

DAVID SHAW.

PART ONE.

John James Bezer was born on the 24 August 1816 in his father's one room

barber's shop in Hope Street, Spitalfields, and baptised on the 15

September 1816 at Spitalfields Christ Church Stepney.

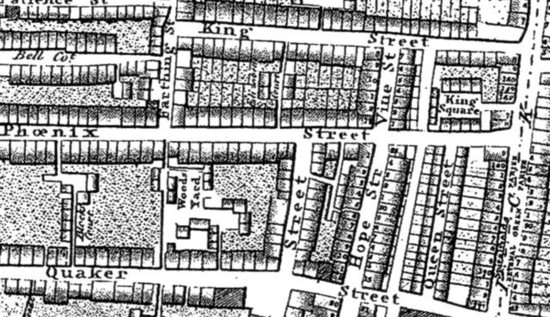

The Hope Street map area (shown below) is dated 1813, and the street—now

redeveloped—is situated in the area today between Brick Lane, Quaker

Street and Grey Eagle Street.

His father was a drunkard and spendthrift, and the family

became out-door paupers, the parish allowing them four shillings per week.

At nine years of age, young Bezer obtained his first post as a warehouse

errand boy in Newgate Street. Working a 17 hour day for a six-day

week, he received three shillings. At one time, he and his mother

lived in Whitecross Place, near the Barbican, about which he said:

"It is said, God made everything. I don't believe it;

He never made Whitecross Place, the entrance to which was the narrow way

that leadeth into stinks. A gutter passed through the middle of the

court—a pretty looking gutter, from which the effluvia rose up, without

ceasing, into our elegant second floor front; a room, or rather a cell (we

paid 2s. 3d. rent weekly, for the blessed privilege of breathing in the

accumulated filth below); a hole in which the bugs held a monster public

meeting every night, determined to show what a co-operative movement could

do."

Whitecross Place—"the place of stinks" is shown

(below) in the 1813

map beneath Crown Street. It shows also the narrow entrance from

Wilson Street, at the South-east of Finsbury Square leading into an

irregular enclosed area. Although some

improvements had been made since that time; Charles Booth noted it in his

1898 poverty map as belonging to the lowest, very poor class. It is

still marked on maps today, at the corner of Wilson Street and Sun Street.

Between January and July 1837 (records destroyed), he married

Jane Sarah Drew at Christchurch Newgate Street, and the birth of their

first child occurred the following year. Francis James Bezer was

born at 6 am on 6 February 1838 at 30, Back Hill, Saffron Hill.

Bezer was listed then as a 'Town Traveller', a broad term, for at that

time he was jobless, and reduced to singing hymns and begging.

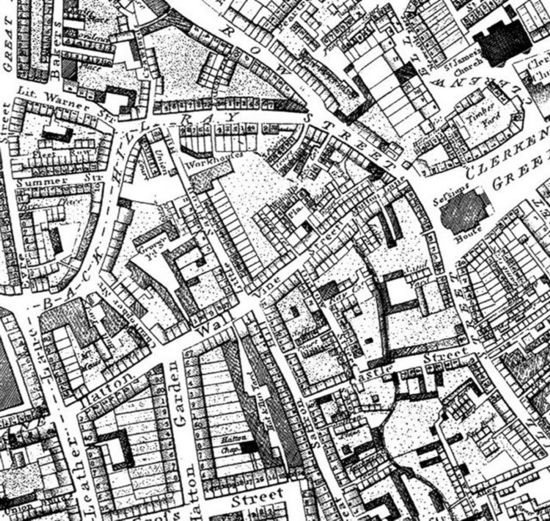

The map illustrated below, (1816) shows Back Hill to the

north of Leather Lane. The family lived also for a while in Ray

Street, between Back Hill and Clerkenwell Green—also marked on the map—but

the date is uncertain (See Bezer's Autobiography).

|

|

|

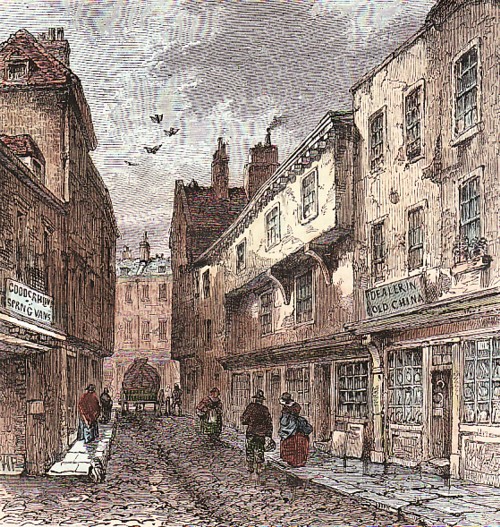

Leather Lane, c. 1870. |

The print below, of Ray Street, Clerkenwell (about 1820)

shows part of Ray Street (left, which continues to Back Hill), with St

James' Church in the background. The cattle would be on their way to

Smithfield. Ray Street is marked on maps today, but is crossed by

the Farringdon Road, and the surroundings changed by increased

redevelopment.

The couple's second child, Jane Sarah Bezer was born on 24

September 1839 at 33 St Helena Place, Clerkenwell. Bezer listed as a

'labourer.' St Helena Place was between Farringdon Road and

Aldersgate Street. It is unmarked on maps, but was mentioned in

Charles Booth's 1898 notes as then being rough, doors open, windows

broken, women wearing sackcloth instead of skirts. Unfortunately,

little Jane did not survive long, having been found dead in bed on the 12

December 1839 (Informant: the Coroner). There was no evidence to

prove the cause of death. Bezer is listed as a 'Shoemaker.'

A third child, Jane Mary Bezer was born on 26 September 1840

at 2 Baldwin's Place, Baldwin's Gardens, Holborn. Bezer listed again

as a Shoe Maker. Baldwin's Place was situated off Gray's Inn Road

between what is now Baldwin's Gardens and Portpool Lane. Charles

Booth's 1898 notes refer to the area as dull, messy, with airless courts.

The children pale, but fairly well dressed and clean.

In 1841, the census return shows the family still living in

Baldwin's Place, St Andrew above the Bar. Bezer is listed as aged

25, a Journeyman Shoemaker with his wife 25, a Dressmaker, and Jane Bezer,

9 months. Her son, Francis James, is not listed.

About 1842, in common with many other workers who were

suffering social iniquity, Bezer joined the Chartist movement, soon

becoming Secretary of the Cripplegate Locality of the National Charter

Association, and speaking at their meetings.

Bezer's next child was Emily Drew Bezer, born on 20 May 1843,

at 4 Carr Square, St Giles Cripplegate. Bezer is listed as a 'Cordwainer'

[a shoe or boot maker]. Carr Square was west of Moor Lane—now

redeveloped, and near Moorgate tube station.

Another son followed fairly quickly, as did another move:

Frederick John Bezer was born on 1 December 1844 at 7 Hanover Court, St

Giles Cripplegate. Bezer remained listed as a Cordwainer. Hanover

Court was between Milton Street and Moor Lane, and the area is

redeveloped. The site would be approximately where Milton Court is

today.

Another daughter, Mary Nelson Bezer was born on 4 August

1846. The family had moved yet again, this time to 5 Bromleys

Buildings, Bread Street Hill. Bezer now listed as a 'General

Dealer'. Bromleys Buildings were between Huggin Lane and Bread

Street Hill. Bread Street Hill is now the area of Bread Street between

Queen Victoria Street and Cannon Street, near Mansion House tube station.

Bezer's third son was next on the scene. Walter Cooper

Bezer was born on 10 July 1848, at 2, Shepherd and Flock Court, Little

Bell Alley, North East of the City of London. Bezer listed now as a

'Fishmonger', the occupation he gave when he was arrested the following

month. Shepherd and Flock Court was situated off White Alley,

Coleman Street (near the Bank of England), and between Little Bell Alley

that ran between the east end of Great Bell Alley and London Wall.

The area was rebuilt c 1890. There is a short stretch of Great Bell

Alley off Coleman Street that is still marked on maps today, south of

Moorgate tube station. The name of 'Walter Cooper' may have

been given as an association with Walter Cooper who became Manager in 1850

of the Working Tailor's Association, Castle Street. Cooper had been

lecturing prior to this, Gerald Massey having come into contact with him

in 1849.

In 1848, following the failure of the Kennington Common rally

on 10 April and the petition to Parliament, a number of militant Chartists convened

private meetings with the object "if possible, to destroy the power of the

Queen, and establish a Republic." All these meetings were undertaken

apparently without the knowledge of the Executive of the National Charter

Association. Bezer gave covert assistance, and was able to inform

those members involved that he—amongst others—would be able to supply 50

fighting men, and that they 'were going to get up a bloody revolution'.

However, Government spies defeated the plan; six of the plotters were

transported to Australia, and fifteen imprisoned [The Times, 23

September 1848].

Shortly after the Kennington Common episode, and following an

address he gave at a public meeting [see

Regina v. Bezer], Bezer was convicted of sedition [Ed.

― inciting resistance

to lawful authority and tending to cause the disruption or overthrow of

the government] and sentenced to two years imprisonment in London's

notorious Newgate prison. Prior to his arrest in 1848, he had been

on the Committee and was an active member of the Irish Democratic

Confederation of London―a strongly militant group that had Feargus

O'Connor as president. The objectives of this Confederation

included the repeal of the Union between Great Briton and Ireland and

the establishment of a representative parliament. Bezer had

lectured on the Irish question as well as on Chartist themes at various

venues throughout the previous twelve months, including Cartwright's

Coffee House, Cripplegate; the Star Coffee House Redcross Street, Golden

Lane; and the Literary and Scientific Institution, John Street.

The latter was a public meeting held on 22 June, 1848, complaining of

police action against Chartists. At this meeting, Bezer moved

'That making the police a military body was subversive of liberty, and

the British Constitution.' (Northern Star, 1 July, 1848.)

The year was ending most unkindly

for Bezer. His son, Frederick John Bezer, then aged nearly four

years, caught Scarlet Fever in the early part of August.

Unfortunately it was the malignant type, and the child died of 'cerebral

effusion' on the 1 September, soon after Bezer entered Newgate prison.

His wife was now residing at 3 Sherroll's Buildings, St. Botolph,

Bishopsgate. The address has not been identified on maps.

The occasion of his release from Newgate in April 1850

together with a number of other Chartists, was used to promote the

Chartist cause. A meeting was convened by the provisional committee

of the National Charter Association on the 23 April 1850, at the John

Street Institute. Thirteen of the released Chartists mounted the

platform, and committee members, including Bronterre O'Brien and George

Julian Harney made spirited addresses. Bezer was introduced, and

addressed the packed hall amid loud cheering. (Northern

Star, 27 April 1850.)

Following the collapse of the Kennington meeting, the

authorities took a much more lenient view of subversive lectures, as the

threat of organised violence had considerably diminished, and Bezer lost

no time in continuing his Chartist activities. The Northern

Star (4 may, 1850) noted that Bezer was commencing a series of

weekly lectures at the 'Old Dolphin,' Old Street, St. Like. His

first lecture to be 'What can I do for Liberty?'

At a public meeting of the National Charter Association

Executive to discuss the Foreign Policy of Government Ministers, Bezer

came forward amid much cheering. He said that as regards ministers

and their foreign policy, he thought they cared more for people that were

far away than they did for those at home. He held in his hand The

Young American, a Republican paper, which paper was the advocate of

social rights. He then read several extracts showing that poverty

and pauperism prevailed in the States and that even the Republican

institutions were not complete if confined to mere politics. That

showed the necessity for social rights, such as the nationalisation of the

land etc. Bezer continued by quoting many great authors in favour of

equality of rights, and appealed to the audience not to heed mere names,

but to stand by principles. He sat down to loud applause. (Northern

Star, 6 July 1850.)

In July 1850 the Metropolitan District Council resolved that

localities take a benefit with a view of placing the victim [as a

political martyr] John James Bezer in a small way of business. Bezer

said he should like the joint trades of greengrocer and fishmonger.

The Council considered that if the sum exceeded £10, the excess could be

devoted to other political martyrs. Bezer thought, with that, and an

already promised amount, he could make a fair start with £10.

The following month the question of improved circulation of

information was brought up at a National Charter Association meeting.

Bezer was called to the Chair, and discussions were raised re

dissemination of democratic knowledge via tracts, periodicals and

newspapers. It was noted that many shopkeepers refused to expose

The Red Republican for sale, or obtain it when ordered. Bezer

pointed to the necessity of extending political and social knowledge to

prevent the people in future being fleeced by parliament voting an immense

Palace to an infant in his ninth year, and give five thousand pounds for

stables for the Prince of Wales' horses, nine or ten years hence.

This was supported by Bronterre O'Brien. Mr Gerald Massey amidst

loud cheers, came forward and suggested a number of broad general axioms,

such as "All men are brethren," etc. and said that he thought some broad

basis of this description might be laid, on which all could stand in the

common band of unity. He said that in six months not less than eight

associations had been established, and invoked them to press onward in the

good cause of democracy, burying feuds in the dust. (Cheers.) (Northern

Star, 10 August, 1850)

During that month, Bezer had been making arrangements for a

lecture tour throughout the Midlands. His general subjects for the

lectures were advertised in the Red Republican and Northern Star

as:

-

The sufferings of himself and fellow-victims in prison.

-

The principles of social and democratic reform.

-

The united organisation of social and democratic reformers to obtain the

Charter.

His home address was given as 32 Bartholomew Close, Smithfield. [Still on

maps today, off 'Little Britain', but redeveloped.]

Commencing at the New Hall, Northampton on Monday 19 August,

his subject was 'Political and Social Reform, with Revelations of his

Imprisonment.' The Northern Star (24 August, 1850) reported that

Bezer's happy vein of treating the subject gained him continued

plaudits." Then

to Leicester for two lectures the following day, at which 1,000 persons

were stated to be present. He continued to Loughborough, Sherwood

Forrest, Sutton-in-Ashfield and Arnold. At Holbrook Moor, two pieces

written by him whilst in Newgate prison were sung, and he spoke on the

People's Charter and his treatment in Newgate.

Following Bezer's lecture tour, complaints regarding

the treatment of other Chartist prisoners were being made. On the

8 October 1850 a public meeting was held in the Broadway, Westminster,

for the purpose of hearing statements from several Chartists who had

been held in Newgate, Tothill Fields and Horsemonger Lane prisons.

John Arnott, as

Secretary to the Victim Committee of the National Charter Association

had been in communication with Thomas Wakley M.P. for Finsbury,

regarding the treatment of the prisoners. Mr Wakley had referred

the matter to Sir George Grey who had been informed by the Secretary of

the Home Office that, following enquiries, he had been assured that the

prison regulations had been conformed with. This despite the fact

that two Chartists had died in prison, victims of ill treatment.

The mother of one of the victims gave an account to the

Coroner. She stated that she went to visit her son, and found him

in a prostrate state. Asking what nourishment he had received, the

officer on duty said that he had plenty of soda water. Asking if

he could be allowed a little arrow-root, the officer replied that he

would not take it. On asking her son, he said yes. Two hours

later some three tablespoonfuls were brought to her, which her son took.

On visiting the next day, he told her that he had received nothing since

her last visit. He died the following day.

Bezer who was present as one of the victims, said that

imprisonment had only sent him there as a Chartist, and it has sent him

out a Republican. He said that the first speaker (Mr Shaw) had

suffered extremely, and had for some time been compelled to go upon

crutches. There was a classification of prisoners in Newgate, of

which the public had little knowledge, but the classification was not

one as regarded the nature of their crimes, but as regarded the weight

of their pockets. There were in Newgate prison fifteen condemned

cells, and he and Shaw were confined in two of these for twelve months,

until rheumatism and illness laid them both on their backs.

He certainly tried to make himself rather a troublesome

customer, and among other things, on the anniversary of Charles the

Second, he refused to go to chapel, as he said he didn't want to return

thanks for any such matter, as he thought Charles the Second ought to

have been treated just the same as his father had been. [Ed.―executed!]

They were always told they must conform to the rules of the prison, but

these rules, although he had often asked for them, they never yet could

see.

It was reported that Bezer continued with his experiences at

considerable length. (Northern Star, 12 October, 1850.)

On the 26 October Bezer commenced as a newsagent. This

was probably a rethink of his previous suggestion of a job as greengrocer

and fishmonger that he had given at the Metropolitan District Council

meeting. In November he gave his address for this as 6 Sycamore

Street, Old Street, St Luke's. At this time Harney had received a

cleverly rhymed letter with a verse and cartoon from ‘M.P.’ who stated he

had received it with a request that it be forwarded to Harney. It

was signed Brougham and Vaux―but was unlikely to have been written by

him. The cartoon was a parody of the "Arms of the British Monarchy",

with the verse being an ‘explanation’ of the items on the Arms (Red

Republican, 26 October 1850). These items are appended below:

|

LORD BROUGHAM

TO THE EDITOR OF THE RED REPUBLICAN

You, like all clever men, dear Harney!

Know I abominate all blarney,

Tow’rds high and low, to friends and foes.

In place or out, in verse or prose,

In foreign climates or at home,

I’m always just the same plain Brougham.

I hate all flattery; not that I

Would hit a friend upon the sly.

I speak my mind out like a man,

And make a hit just when I can. (1)

Though sometimes pausing on the brink,

I don’t perhaps say all I think:

For I’m not spiteful nor sarcastic.

But having a nature very plastic (2)

I turn my talents multifarious,

To objects useful, vast, and various.

Well, Harney! I admire your Red

Republican; and so I said

To my friend Lyndhurst, who agreed

With me, ‘twas very red indeed.

And thereupon I write you this

Concise and terse and brief epis-

Tle, (you’ll excuse this funny nick

In the word’s middle! ‘Tis a trick

We poets have: myself and Wakley,

Who hold our jawing-tackle slackly)―

Partly became, I blush to own,

Though there are few things I’ve not done,-

And well,―say better,―I have yet

One sad omission to regret:

That never for the People’s sake

I’ve worked till now. So prithee take

This letter as a part amends.

Henceforth we shall, I trust, be friends;

And as I still am hale and hearty,

Untrammel’d too by place or party,

I’ll give your side a turn or two,

Old boy! Won’t that astonish you?

But to the purpose of this letter.

(Few men, I think could write a better:

The engraving is my own design,

Maclise allows it’s very fine,-

And by myself cut in the wood,

My first attempt, and rather good).

On my old quest of useful knowledge,

I search’d of late the Herald’s college:

Wishing to learn if I could trace

Brougham and Vaux’s shining race (3)

To history’s unexampled Guy.

I found him out. (4) How history

Has slandered him! It slanders me!

Well, what d’ye think I chanced to see

Among a lot of queer old rubbish,

Hid in a corner rather grubbish?

(I love such corners!) How I laugh’d:

‘Twas our KINGS’ ARMS’

original draft.

And all in herald jargon writ:

You’d never have decipher’d it.

I did, and found it pleasant too;

And now translate the same for you.

I might have given it in plain prose, (5)

But write verse easier.―So here goes. |

|

The Arms of Britain’s monarchy, by loyal Britons prized,

‘Tis surely time their bearings were made plain and vulgarized:

That even the meanest British slave, or the nearest to the Brutes,

May know exactly what they mean, those royal attributes.

The herald’s coat’s a bishop’s frock, to show the “right divine,”

Which is somehow got at through the Church, and quite direct the

line;

And the bishop’s stirring in the coat, with a swaggering, tipsy

gait,―

For his foot is on the poor,―‘tis not that he’s intoxicate.

The poor man lies right in his way, with his face hid in the earth,

As if, spite of his crown of thorns, he isn’t of much worth;-

But turn to the bishop’s blazonry, and feast your vacant look

On the royal quarterings: here they are, as in the herald book.

For England’s lions―donkeys, sanguine, on a field of gold;

For Ireland’s harp―a peasant strung upon a gallows old;

The Scottish quarter is not seen, but there can be little doubt,

It’s a rampant donkey, sanguine (all the donkeys look starved out).

For supporters―on the sinister side’s a lion of the law. (6)

With spectacles and learned wig and awful breadth of jaw;

And dexter side the unicorn, with a death’s head in his hat,

And saddled back,―he seems to bid the bishop mount on that.

The whole’s surmounted for a crest, with the bonnet and the phiz

Of our most gracious sovereign: and very plain it is―

That the wreath of German sausages hangs there in honour of him

To whom a grateful nation owes so many a royal limb. (7)

The motto still is as of old.―“God and my right:” but “God”

Lies under the couchant lawyer’s paws; and the armed brute has trod

On “Right.” There’s little alteration you can see in all

these things

Since heralds first found monsters out and liken’d them to kings. |

|

You’ll publish this: t’will make some laugh,

Some think. And for my autograph,―

I’m not so vain as Wellingon

Who gives his mark to every one;

But you can sell it―the proceeds

May help your advertizing needs.

Yours, without prejudice or flaw,

Fraternally ever,

Brougham and Vaux. |

(1 Pretty often, I

guess.

2 “Plastick- that facility which can form or

fashion anything.”―Bailey’s Dictionary.

3 Does he mean by the aristocratic slime,

slug-like?

4 Guy Fawkes, or Vaux. His lordship’s not so

green as we thought.

5 Unconscious that he was writing verse

before. The sublime unconsciousness of

genius, according to Mr. Carlyle.

6 There seems some mistake here. Or, has the

noble writer shrewdly altered the

relative position of the supporters? It is true

the law has grown more dexterous and

the sword rather left-handed of late. Perhaps not

knowing the process of printing,

he has forgotten to reverse the drawing.

7 As we say, a limb of the law. I was called a limb

when I was a child.) |

The cartoon, together with the letter and verse obviously

appealed to Bezer’s sense of humour. He had it reprinted, and

advertised it for sale at his home address, Sycamore Street, in the

following fortnight’s Red Republican for one halfpenny, or 7d per

quire for Trade.

Bezer was also quick to take advantage of the Christian

Socialists, having been introduced to them by Walter Cooper. In two

advertisements in December 1850 issues of the Christian Socialist,

he referred to himself by:

RECOMMENDATION EXTRAORDINARY!

J.J. BEZER, from Newgate!!

News Agent and dealer in Periodicals.

No. 6, Sycamore Street, Old Street, St. Lukes.

Orders punctually attended to. |

Continuing with his activities, later in the year he stood on

the Polish Refugees Sub-committee of the Metropolitan Trades Committee.

Then in January the following year, 1851, at a public meeting at the

Literary Institute, Portman Square, he moved: "That the Executive of the

National Charter Association as a body deserves the support of all true

democrats. To make the agitation [for the Charter], they must join

the Association, and prove by their zeal that they really were in earnest

in their profession of a desire to raise themselves on the side of social

society."

Continuing dissention between the locally powerful Manchester

Chartists and the National Charter Association gave the NCA cause for

continuing concern. A meeting was convened at the John Street

Institute in February to receive a report of the Executive Committee

relative to charges made at the Manchester Conference by Feargus O'Connor.

Gerald Massey and others spoke, and Bezer moved "That this meeting is

further of opinion that the people's cause requires that their

acknowledged leaders should be protected from insidious and indirect

attacks and denunciations; and that it holds as despicable the conduct of

any man and every man, whose practice it is to vaguely and treacherously

arraign and denounce those leaders, and yet shrink from the responsibility

of proof." This received support, was applauded, and adopted.

The census record for 1851 shows the family at 6 Sycamore

Street:—John Bezer, 34, News Agent. Jane S. Bezer, 34. Francis

S. Bezer, 13. Emily D. Bezer, 7. Mary N. Bezer, 5, and Walter

C. Bezer, 3.

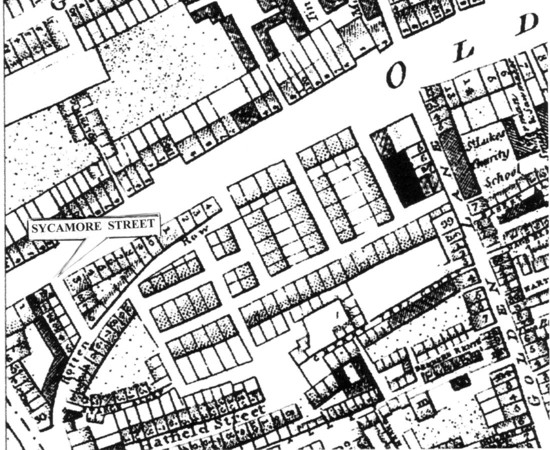

Sycamore Street—noted on the map below—was situated between

Old Street and Goswell Road, and led from Rotten Row to Old Street.

A small part of the street is still on map today, with Rotten Row being

renamed Crescent Row.

The year of 1851 was made particularly notable by the Crystal

Palace Exhibition in Hyde Park. However, Bezer prejudged this in a

most negative manner. A lecture he presented in March titled 'The

Exhibition, what will be exhibited, and what is hidden', at the Rose and

Crown, Colville Place, Tottenham Court Road, was reported by the

Northern Star. Bezer ably dilated upon the false and hollow

grandeur which would be exhibited to the visitors from abroad, whilst

every endeavour would be made to banish poverty from their view.

They would see the Glass Palace glazed by unpaid and imprisoned glaziers.

The enormous block of coal would be exhibited, but the poor miners would

be hidden. Splendid silks would be there, but the weavers would be

kept out of view. The productions of industry would be shown, but

none of its due rewards. They would see an immense blue exhibition

of 6,000 police, and 300 intensely blue, for the purpose of keeping peace,

law and order, near the building. They would also see an immense red

exhibition, headed by the her Majesty's most confidential adviser―the

Duke of Wellington. There would likewise be a great exhibition of

rant, cant, and humbug. If they looked at the Times or

Chronicle, they would see subscriptions called for to convert the poor

Heathens who would be present at this Vanity Fair. If a poor

Chartist attempted to speak of his wrongs, the blue and red exhibition

would soon put him down, though they would be unable to put down the

truths he was anxious to enforce. The Exhibition would be a monument

of hollow, empty extravagance, supported by physical force on one hand,

and superstition on the other. The attempt to hide poverty by keeping the

costermongers and others out of the streets was vain and futile. They

would fail in their object, and only increase the number of Chartists.

"Mr Bezer, during a clever and humorous address, was much applauded." (Northern

Star, 22 March 1851.)

Note: The Crystal Palace Exhibition sited in Hyde Park was open

from 1 May―15 October 1851. It extended to an area six times that

of St Paul's Cathedral. Following the exhibition, the building was

disassembled and reopened in Sydenham in 1854.

One can compare Bezer's advance negative opinion of a grand

exhibition with that of Gerald Massey's artistically positive but

over-long account of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857.

(Massey biography, chapter 3.)

Bezer's fourth son now arrived. John James Bezer was

born on 16 May 1851 at 3 Sycamore Street. Bezer was listed as a

'Newsagent', and appears to have moved from No. 6 in that street.

At a public meeting later in July, at Finsbury, Bezer noted

how even the most liberal of Press, excepting the Northern Star and

other democratic journals, misrepresented and distorted every meeting of

working men, when they condescended to notice them. When a

jeweller's shop was broken into at Camberwell, during the meetings in

1848, though it was well known by the evidence on the trial that it was

done by a gipsy, who knew nothing about Chartism―yet even Lloyd's,

a professing liberal paper, headed their account of the trial with the

words―'Trial and Conviction of another Chartist Leader.'

Yet another meeting was convened shortly after that, for

victims of the spy system of Whig government. This was held at the

Dog and Duck Tavern, at the corner of Frith Street and Queen Street, Soho.

Discussion was raised to adopt steps relative to the parliamentary enquiry

into their treatment during the ensuing session. Many victims and

relatives were present. Bezer moved: "That we, the political victims

of 1848, do now form ourselves into an Association, for the purpose of

exposing the period of our incarceration, and to prosecute, by means of

Lord Dudley Stuart and other parliamentary friends and enquiry before the

next session of parliament relative thereto, and thus prevent a repetition

of much unconstitutional and impolitic treatment."

The Political Victims Association met a week later, at the

Paragon Chapel. Bronterre O'Brien took the Chair. During

discussions, Bezer stated that he was not allowed to see his wife for five

months, although a prisoner in the next cell saw his sweetheart every

other day―but then the respectability of his crime was no doubt the cause

of the difference between them, the fellow having only violated two

children under eight years of age.

By way of advertisement and support, in October, the Victims

Committee presented 'A Democrat Concert' at the Two Chairmen, Wardour

Street, Soho. Bezer was in the Chair. The Northern Star

reported that a number of male and female democrats attended to give mirth

to the proceedings. Mr Bezer with his usual drollery turning 'The

Victims of '48' into 'The King, God bless him.' John Arnott and John

Bedford Leno gave appropriate recitations.

From 9 August 1851 having been recommended by F.D. Maurice,

he took over as publisher of the Christian Socialist using the

office of the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations, at 183

Fleet Street. In 1830, William Cobbett had published his Rural

Rides from that address, and in 1847, William Edwards, importer of

Parisian novelties, occupied the premises. However, the journal ran

into financial difficulties, and was discontinued in December of that

year, although reviving temporarily from 3 January to 28 June the

following year as the Journal of Association. That premature

curtailment of Bezer's autobiography, as previously mentioned, leaves a gap in his story of some

eight years, and he probably intended to continue the autobiography up to

the time of his arrest.

|

|

|

Fleet Street, c.1830.

This view is taken beyond Fetter Lane on the

right. Temple Bar is in the background, showing

the clock of St. Dunstan in the West just beyond Clark and

Weatherly, goldsmiths. Thomas Redshaw, bookseller, is

at No. 186, and Edward Cane, ironmonger, at No. 185.

John James Bezer's bookshop at the Society for Promoting

Working Men's Associations, No. 183, which does not appear

in this view, would have been between No. 185 and Fetter

Lane. |

At his Fleet Street office/bookshop, he also published the

Star of Freedom (change of name from the Star and National

Trades' Journal which, previous to that, was the famed Northern

Star and National Trades' Journal), from Vol. I, no. 1, 8 May 1852, to

Vol. I (new series), no. 4, 4 September 1852. George Julian Harney

took over as publisher from issue no 5. The Star of Freedom

ceased publication from 27 November, and Waller & Son, Booksellers then

occupied the bookshop at 183 Fleet Street.

In 1851, the City Builders were forming an Association, and a

Public Meeting was held at the Hall of Science, City Road on 1 December.

Gerald Massey and Frederick Furnivall attended on behalf of the Society

for Promoting Working Men's Associations. Walter Cooper was to have

been the principal speaker on their behalf, but he had been injured in a

railway accident. Bezer was also in attendance, and seconded a

resolution concerning a general fall in wages with consequent degredation

of working men in all trades. The resolution stated, 'This meeting

believes the unrestricted and increasing competition in all branches of

productive industry, to be the cause of their fall in wages.' It was

reported (Christian Socialist, 13 December 1851) that

Bezer—Publisher to the Society—after giving a humorous defence of the

class of distributors to which he had belonged all his life, followed

through an argument proposed by Mr. Furnivall in his resolutions.

Bezer emphasised the necessity and duty of association on the highest

grounds, and maintained that the only reason which made working men

dislike religion was, that the professors of Christianity so seldom acted

up to their principles. He ended by asking what working men would be

able to do with association when they had also got the vote, seeing the

wonders they had already done without it?

Bezer also continued with his Chartist activities, and was

one of nine elected to serve on the Executive of the National Charter

Association for 1852. In January 1852 he lectured at the Literary

Institution, Leicester Place, Little Saffron Hill, on 'Association among

the poor; the only remedy for conspiracy among the rich.'

On 13 February 1852, Bezer's son, John James Bezer, aged 9

months, died of 'Teething Convulsions' at 10 Milford Lane, Strand, St

Cement Danes, where the family were then living. Bezer is listed as a

'Bookseller'.

Following an adjourned Conference on 3 March 1852, the

National Reform Association held an evening Aggregate public meeting at

St. Martin's Hall, Long Acre. A number of prominent M.P.'s were

present. During the proceedings, the Chairman, Mr. J. Hume M.P. made

several comments that received support from the audience. One such

expressed the tone of the meeting: '...the House of Commons did not

represent the people; that the rule was placed in the hands of the

aristocracy. If all classes did not participate in the election of

those who formed the House of Commons, it could not be expected that the

House of Commons should act fairly towards all classes...' Sir

Charles Napier also called for radical reform, and hoped that when the

present Ministry was turned out of office, as he most sincerely hoped, he

trusted to see a good Administration composed of real Radical Reformers,

who would present a bill worthy of the acceptance of the people of

England.

A resolution was proposed and seconded, "That this meeting

believes radical Parliamentary reform to be the great practical want of

the day, and, while declaring the maintenance of free trade, records its

conviction that freedom of trade would have been impregnable if the

suffrage had been placed upon a truly national basis, and that, in common

with other equally important questions, free trade can only be finally

decided when the House of Commons is made a real representation of the

people."

Bezer, as a working man, rose and proposed as an amendment,

the addition of the words:

"That the only principle of Parliamentary reform recognised

by this meeting as just is the enactment of manhood suffrage, guaranteed

by the ballot, short parliaments, equal electoral districts, no property

qualification, and payment of representatives." (Great cheering.)

He agreed with the greater part of what had been said that

evening. He agreed also that those who were amenable to the laws

ought to have a voice in making those laws (cheers); that taxation and

representation ought to go together, that it was especially important to

the poor man to be represented, which meant, if it meant anything, that if

any were to be disenfranchised it was those who could afford to wait, and

not those who had waited so long. (Cheers.) He only wished the

gentlemen who had brought forward the resolution would make it as good as

their speeches, and that would be done by substituting the word "manhood"

for "real."

Mr. Shaw, from the Tower Hamlets [probably John Shaw who had

been imprisoned in Newgate] seconded the amendment. He observed

that, though the Chartists were supposed dormant, their spirit still

remained.

Nevertheless, there was considerable opposition to Bezer's

amendment. George Jacob Holyoake

urged its withdrawal, saying that whilst his friends said they did not

come there to make division, they did make divisions. (Great clamour.)

He also objected to the word "Manhood" suffrage, when it should also

include womanhood suffrage. Another speaker, on hearing that it was

proposed to give votes to the army, asked how the working-men would like

to be served as the men on the other side of the Channel had been?

Following further discussion and a show of hands the chairman declared the

amendment negatived.

This opposition by Holyoake to his proposed amendment induced

Bezer to write a letter to Harney in the 13 March issue of the Friend

of the People:

|

THE CHARTIST EXECUTIVE

To the Editor of the FRIEND OF THE PEOPLE.

SIR—May I be allowed a

word to the members of the National Charter Association in your

excellent paper?

It appears to me that an Executive who cannot act together,

whose members oppose each other on material points, must burden the

Chartist cause.

Mr. Holyoake and I are opposed; that gentleman's speeches,

both at the Conference of the National Parliamentary Reform

Association, and at the Aggregate Meeting at St. Martin's Hall, this

week, did not, I think, represent the views of the majority of the

members of the Chartist Association. I may be wrong, but both cannot

be right, and as disunity in the Executive must increase disunity

among the members, one of us ought to withdraw. Brother Chartists,

which is it to be?

I am, your earnestly,

John James Bezer.

183, Fleet Street. |

This observation by Bezer had also been made by Gerald

Massey, and was becoming obvious to all. It was finally acknowledged

at a meeting of the National Charter Association on the 24 March, when it

was admitted that it was:

"The Executive of a society almost without members, and

without means - members reduced to unwise antagonism without, and

influence reduced by repeated resignations within..." [Reynolds' Weekly

Newspaper].

The last two mentions of Bezer was by the Star of Freedom

on the 12 and 19 June. On the 12 June he is listed, amongst others,

as giving 2/6d as a subscription to complete the payment of the NCA debt.

On the 19 June he gave another small amount on behalf of the City Western

locality.

About early July 1852, Bezer (as Publisher) was given

(another account said he asked for) a cheque by Lord Goderich (George

Robinson) the Christian Socialist supporter, in aid of the declining

radical publication, the Star of Freedom. The Star's

editor, George Julian Harney, not having received the money, made

enquiries via Goderich, who learned that Bezer had fled to Australia in an

emigration ship, leaving his wife behind. Prior to this, Bezer had

been officially accepting money orders from subscriptions to the Star

of Freedom made payable to him at the Strand Post Office (Star of

Freedom, 26 June, 1852). However, there was no indication of

any impropriety in those dealings.

Gerald Massey was so disgusted at such behaviour by a

previous valued upholder of Chartist and Co-operative principles, that he

sent an emotive over-coloured optimistic five verse poem encapsulating his

opinions on the subject to Harney, for publication in the Star of

Freedom:

|

THE DESERTER FROM DEMOCRACY.*

Another gone back, when our battle went sorest!

Another soul sunk, like a star from the night!

Another hope quencht when our progress was poorest!

Another barque wreckt, with the haven in sight!

Our Brother once—Traitor now: Nay, we'll not curse him,

O Freedom forgive him, he knew not the cost!

He needeth our prayers, and if tears may amerce him,

Then tears that are worlds of love, weep for the Lost!

Oh! little we thought when we tenderly bound him

Up, bleeding and torn from the fierce thorns of Life.

How all the sweet tendrils of love we twined round him,

Would come home to die with such heartache and strife!

He thinks to flee from us? God pity his blindness!

For, we shall be near when, in Memory start

The old looks of Love, and the old voice of Kindness,

He'll weep tears of blood yet; and eat his own heart!

He is gone from us! Yet, shall we march on victorious;

Hearts burning like Beacons—eyes fixt on the Goal—

And if we fall fighting, we fall like the Glorious

With face to the stars; and all heaven in the soul!

And aye, for the brave stir of battle, we'll barter

The sword of Life sheath'd in the peace of the grave

And better the radiant fire-robe of the Martyr,

Than purple and gold of the glistering Slave!

He is gone! Better so. We should know who

stand under

Our Banner: let none but the trusty remain:

For there's stern work at hand, and the time comes shall sunder

The shell from the pearl, and the husk from the grain.

And the Soul that thru danger and death will be dutiful,

Chivalry's zeal, Martyr-faith, Hero-hands,

With pure heart, like a palace-home built for the Beautiful,

Freedom of all her true lovers demands.

Lo! the Harvest bends rich for death! Earth's

long-Accurst

Are ripe for Wrath's wine-press. Sound Tyranny's

knell!

For the heart of old Europe doth biggen and burst

To hurry them into their own fiery Hell.

And the Lowly, with ear to the earth, catch the humming

Of Freedom's Car-wheels, as they roll down the Time—

Which doth darken too flash forth the Glory that's coming

To crown the old Cause with its triumph sublime.

GERALD MASSEY.

* Alias, that blasted Bezer! |

Harney did not publish the poem, but Massey included it,

shortened and

amended, in later editions of his poetical works.

In 1859, on the 12 October, Bezer's daughter, Emily Drew

Bezer was baptised at St. Leonard's Church, Shoreditch. Parents

named as John James Bezer, and Jane Sarah Bezer, residing at 9 Orchard

Place, Shoreditch. Bezer's occupation, Cordwainer. Orchard

Place has not been found on maps. It was probably within the area

N.E. of Finsbury Circus, now redeveloped. Charles Booth (1898) notes

it as being entered from a crooked passage. Clean, but poor.

From the above information, there remains the question

regarding Bezer's apparent reappearance.

1861.

In census records of 1861, one of his sons is listed at:

|

6, Lower Felix Street, Bethnal Green.

Francis James Bezer, head, 23, Cordwainer. Born London St

Andrews.

|

Felix Street was sited between the east end of Hackney Road and Old

Bethnal Green Road. It was continued as Lower Felix Street for a

short distance. The area has been redeveloped as the Minerva Estate,

at the corner of Hackney Road and Cambridge Heath Road.

Also from 1861:

3B Virginia Row, Bethnal Green.

Bezer's daughter, Mary Nelson Bezer. 14, apprentice, born Middlesex

London,

Henry Thompson, head, 28, Machine Boot Closer [A person who

sews the

uppers of boots. Ed.]. Born Middlesex Shoreditch.

Hannah Thompson, wife, 38, employing 2 women, born Wilts Bradford.

Annie Thompson, daughter, 1, born Middlesex Bethnal Green. |

Virginia Row was situated in the area of the present Virginia Street,

between Bethnal Green Road, Shoreditch High Street and Hackney Road.

This next extract also from the 1861 census is of interest:

2A Old Bethnal Green Road

John Bezer, Head, 44 [enumerator's mark partly obscures].

Shoe Maker. Born

Marthan, Norfolk.

Jane Bezer, Wife, 45. Boot Binder. Born Shoreditch, Middlesex.

Emily Bezer, daughter, 17, Fitter. Born Cripplegate, City of London.

Walter Bezer, son, 12, Scholar. Born Coleman Street, City of London. |

But is the entry for John Bezer correct?

1862.

Marriage. It was now the turn of Bezer's son, Francis James to get

married. In November that year he married Emma Mander, 23, of John Street,

at St James' Church, Shoreditch. He gave his details as a

Bookseller, living at 2, William Street. His father, John James

Bezer, named as a 'Publisher'. A witness was Bezer's wife, Jane

Sarah Bezer. William Street and John Street were both off Cannon

Street, between Whitechapel Road and Cable Street. Now redeveloped.

1865.

Marriage. Bezer's daughter Mary Nelson Bezer—previously noted as an

apprentice—was married on 16 April at the Parish Church, Bethnal Green.

Details given as a spinster, minor, of 22 Coleharbour Street, Bethnal

Green. Father, John James Bezer, Stationer. She married George

Frederick Fall, a bachelor and shoemaker, of 29 Henrietta Street, Bethnal

Green. Coleharbour (Coldharbour) Street and Henrietta Street not

marked on maps, but were in the area between Hackney Road and Old Bethnal

Green Road.

1868.

Marriage. At St. James' Church, Shoreditch, 1 March 1868: Bezer's last

daughter, Emily Drew Bezer, 24, a Servant, 2 Holywell Row, married John

Coe, 29, (of same address) a Leather Seller's Assistant. John James

Bezer, Publisher, stated then as Deceased. Holywell Row is between

Shoreditch High Street and City Road.

1871.

Mary Nelson Fall (Bezer) and family were living with an 8 month son at 29

Church Row, Wandsworth. John Coe (Leather Seller), Emily Coe (Bezer)

with son Francis F. Coe, now living at 84 Nuffield Road, Tower Hamlets.

1875.

Marriage. Walter Cooper Bezer, Occupation 'Collector', married Caroline

Mackenzie on 25 January 1875 at St Stephen, Bow, Middlesex. John

James Bezer's occupation given as 'Newsagent'.

1881.

At the time of this census, Walter C. Bezer with his wife, Caroline,

daughter Annie, 1, and Harriet Mackenzie, 32, sister-in-law (an unemployed

domestic servant) were living then at 6 Cedar Mews, Clapham. John

Coe and wife Emily (Bezer), with Francis 12, and Hilda 6, were at 24

Odessa Road, West Ham.

1891.

George Fall and Mary Nelson Fall (Bezer) had moved to Alpha Cottage,

Tovells Road, Ipswich, now with 3 daughters and 3 sons.

As mentioned previously, according to Lord Goderich, Bezer

had fled to Australia, [probably in early July 1852] after asking Goderich

for a cheque to help the Star of Freedom. Harney had written

to Goderich, asking what he had done with Bezer, not having received the

cheque. Mrs Bezer had also written, wanting to know what had become

of her husband. John Ludlow commented that he 'levanted' to

Australia with another man's wife, leaving his accounts in disorder.

In addition, as a publisher, he had not submitted the required copies of

the Christian Socialist to the British Museum Library or other

institutions. In Australia, Ludlow stated, he 'went from bad to worse.'

Goderich soon had another occasion to express his displeasure

with Bezer. Goderich was anxious to obtain a Liberal parliamentary

position at Hull, but because of his Chartist and Christian Socialist

sympathies, he found himself strongly opposed by the Hull Tories.

With the help of Bezer and other workers who rallied the ships' carpenters

and engineers, Goderich was elected on the 8 July 1852. During the

election campaign, Goderich had wondered about some of the methods that

had been used, and demand for money made, by his agents. After

Bezer's disappearance, the Hull Tories found that some dubious

transactions had taken place, and made official complaints, thus involving

Goderich. However, following a petition and a House of Commons

Select Committee Enquiry, the Committee fortunately acquitted Goderich of

any personal wrongdoing and knowledge of the unethical activities of his

agents.

Had Bezer disappeared due to receiving Goderich's money?

Alternatively, because of his implication with the underhand methods

used during the election campaign and fearing more time in prison, or

perhaps both?

From the last mention of him in 1868, it may be assumed that

John James Bezer had died between April/November 1862 and March 1868, but

no death certificate has so far been traced, or later census entries

found for him or his wife. The father's name and occupation as

given on later documents need not necessarily give the state of

'deceased'.

[PART

TWO]

|