|

THOMAS

COOPER, the illegitimate son of a working dyer,

was born at Leicester on the 20th of March 1805. After his

father's death his mother began business as a dyer and fancy box-maker

at Gainsborough, and Cooper was apprenticed to a shoemaker. Living

with his mother and half-sister Ann, he spent his free time on an

astonishing - 'fanatical' by most standards - programme of

self-education. By the age of twenty Cooper could recite thousands

of lines of poetry (including the first three books of Milton's

"Paradise Lost"), and was conversant with a large number of historical

and theological texts, as well as Latin, Greek, and French.

In 1827 Cooper gave up cobbling to become a schoolmaster, and

later, a Methodist preacher. His affairs did not prosper, and

after going to Lincoln, where he obtained work on a local newspaper, he

went to London in 1839 where he became assistant to a second-hand

bookseller. In 1840 Cooper joined the staff of the

Leicestershire Mercury, but his support of the Chartist movement

obliged him to resign his position. In 1841 he edited The

Midland Counties Illuminator, a Chartist journal, and became a

leading member of the Chartists. For his part in promoting the

riots in the English pottery towns in 1842, Cooper was imprisoned for

two years in Stafford Gaol. It was during this time that he wrote

his epic poem, 'The Purgatory of

Suicides', in ten books - over 900 Spenserian stanzas - which

embodies the radical ideas of his time. In his efforts to publish

this work he came to the notice of Disraeli, Carlyle, Kingsley and

Douglas Jerrold; it was with Jerrold's help that 'Purgatory' was

published in 1845.

|

More heat

was in impulsive Thomas Cooper, the poor shoe-maker, who beguiled

captivity by writing the "Purgatory of Suicides; a Prison Rhyme," in

ten books, which, with part of an historical romance, a series of

simple tales, and a small Hebrew guide, were the fruits of two years

and eleven weeks' confinement in Stafford Gaol. The author

speaks of himself as one "who bent over the last and wielded the awl

till three-and-twenty, — struggling amidst weak health and

deprivation to acquire a knowledge of languages, — and whose

experience in after life was at first limited to the humble sphere

of a school-master, and never enlarged beyond that of a laborious

worker on a newspaper." His imprisonment was for "seditious

conspiracy"—a speech made by him to some colliers on strike

having been followed, without his purpose or his knowledge, by

riot. He stood two trials—first for taking part in the riot,

when he proved an

alibi; the second for conspiring to produce the riot, for which,

after a ten days' trial, he pleading for himself, he was

convicted. To return to his poem. Noteworthy on account

of the circumstances under which it was produced, it also deserves

credit for itself: a poem well conceived, wrought out with no

ordinary amount of power, and not wanting in poetic imagination.

A few lines may suffice to show its form,—lines of which

Ebenezer Elliott, the "Corn-law

Rhymer," would not have been ashamed. The opening of the third

book:

|

"Hail, glorious Sun!

Great exorcist, that bringest up the train

Of childhood's joyance and youth's dazzling dreams

From the heart's sepulchre, until again

I live in ecstasy 'mid woods and streams

And golden flowers that laugh while kiss'd

by thy

bright beams.

"Ay! once more, mirror'd in the silver Trent,

Thy noontide majesty I think I view,

With boyish wonder; or, till drowsed and spent

With eagerness, peer up the vaulted blue

With shaded eyes, watching the lark pursue

Her dizzy flight; then on a fragrant bed

Of meadow sweets, still sprent with morning dew,

Dream how the heavenly chambers overhead

With steps of grace and joy the holy angels

tread. |

|

|

'WHO

WERE THE

CHARTISTS'

by W. J. Linton |

Cooper's collection of short stories, 'Wise Saws and

Modern Instances' (1845—later extended and republished as 'Old

Fashioned Stories') is generally regarded as his best piece of prose

fiction, providing in places a vivid account of the miserable,

impoverished lives of the Leicester stockingers of his age (e.g.

The Minister of Mercy;

Merrie England;

Seth Thompson). Two

volumes on 'self-help'—a theme more generally associated with Cooper's

contemporary, Samuel Smiles—appeared in 1847/8; "Triumphs of

Perseverance" and "Triumphs of Enterprise" [later (ca. 1880) extended

and combined into a single volume] comprise

a collection of "biographical sketches of the achievements of men famous

in many fields of enterprise, and distinguished by the perseverance they

exhibited" which, Cooper hoped, would "stimulate the youthful reader to

attempt to follow in their footsteps". Among Cooper's other titles

is the historical novel 'Captain Cobler' (1850), and the novels

'Alderman Ralph' (1853) and 'The Family Feud' (1855). The 'Bridge

of History over the Gulf of Time' (1871) is a modestly sized and

very readable book on Christian evidences in which Cooper, in a

well-argued low-church manner, answers the question, "if Christianity be

not true, where did it come from?"—and in the process never misses an

opportunity to heap blame at the Vatican's doorway. Cooper's

autobiography, 'The Life of Thomas Cooper,

written by Himself' (1872), is among the best

memoirs of a Victorian artisan. His life as

a preacher is reflected strongly in his 'Thoughts

at Four-Score' (1885), a collection of opinions (including Cooper's

views on

Darwin and 'the fallacies of

evolution') and solid Victorian—at times Puritanical—moralising

aimed principally at 'young working men'.

Cooper has a further niche in English literature, being

the model for the Chartist 'poet of the people', in Charles

Kingsley's popular novel

Alton Locke and the provider of much of Kingsley's background

information on Chartism among working people.

|

|

|

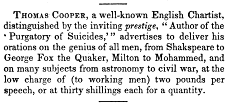

Literary Notices, Harper's Magazine, 1851 |

Cooper eventually turned to lecturing upon historical and

educational subjects. In 1856 he suddenly renounced the

free-thinking doctrines which he had held for many years, and became a

lecturer on Christian evidences. In 1867 his friends raised an

annuity of £100 per annum for him, and in the last year of his life he

received, belatedly, a modest government grant.

|

The First Lord of the Treasury

yesterday sanctioned the contribution, through Mr. Mundella, of a

grant of £200 to Mr. Thomas Cooper, the veteran Chartist leader, and

author of the poem "Purgatory of Suicides," who is now in his 84th

year and infirm in health. The grant is made in recognition of

Mr. Cooper's literary talent and influence as a moral teacher. |

|

The Times, April 30, 1892.

|

Thomas Cooper died at Lincoln on the 15th of July 1892.

Hard-working and intellectually gifted, with a reputation for honesty

and generosity, Cooper was also capable of being pedantic and was a man

who disliked being challenged. In his "Memoirs of a Social Atom",

W. E. Adams describes him thus—"Thomas

Cooper had the 'defect of his qualities.' I have given one example

of his irritability. Many others were known to his friends....Warm

in his friendships, he was bitter in his animosities.....But

Thomas Cooper had other qualities that redeemed his defects.

Innumerable instances of his kindness and generosity are recorded.

It is a loving trait in his character that he never forgot or neglected

any old friend whom he knew to be living in any of the towns he visited

during his later peregrinations."

Other artisan memoires—See also G. J. Holyoake's "Sixty

Years of an Agitator's Life", Samuel Bamford's two-part

autobiography, "Early Days"

and "Passages in the

Life of a Radical" (to which a biographical supplement,

Reminiscences,

was added in 1864), Hugh Miller's "My

Schools and Schoolmasters,"; "Memoirs

of a Social Atom" by the printer turned newspaper editor,

W. E. Adams and "Recollections

of Fifty Years" by poetess and author Isabella Fyvie Mayo (aka

"Edward Garrett"). |