|

|

|

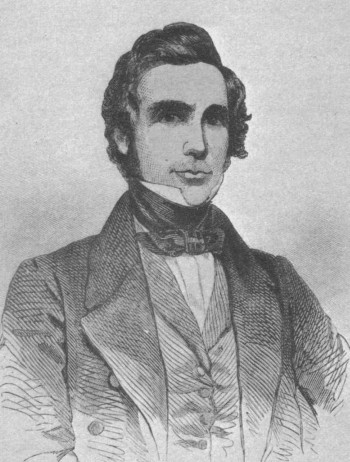

WILLIAM

LOVETT

(1800-77),

an important leader of the Chartist

movement.

"A tall, thin, rather melancholy

man, in ill-health, to which he has long been subject;

at times he is somewhat hypochondriacal; his is a spirit

misplaced."―Francis Place. |

Self-educated, WILLIAM LOVETT

was one of the leading London-based artizan Radicals of his

generation and an important leader of the Chartist movement.

Lovett was

a moral force Chartist who believed that political rights could be

achieved through political pressure and non-violent agitation, and

that teaching methods should be founded on kindness and compassion.

As a respectable Victorian Liberal he eventually became estranged

from the more prominent 'turbulent' wing of the Chartist movement

advocated by, among others, Feargus O'Connor (according to Lovett,

the great "I AM" of politics), William Benbow, George Julian Harney

and Ernest Jones.

―――♦―――

William Lovett was born at Newlyn, Cornwall, on 8th May, 1800. He

was the son of a sea captain who was drowned before his son was born.

Initially apprenticed to a rope-maker in his home town, Lovett later moved to London where,

after enduring much hardship and experiencing resistance from

established trade craftsmen, he found work as a carpenter and later as a cabinet-maker, eventually

becoming a member of the Cabinetmakers' Society and later its

President.

|

". . . Satisfied, therefore, that most of those

evils can be traced to unjust and selfish legislation, we have

pushed our enquiries still further, and we find their chief source

in our present exclusive

system of representation. The franchise being confined to a small

portion of our population, and that portion controlled and

prejudiced to an incalculable extent by the wealthy few, the

legislators and governors of our country have not been a

representation of the minds and wants of the nation, but of the

political party through whose influence they owe their power. Thus

it is that restrictive laws are maintained, that

selfish measures

have originated, and class interests are supported, at the expense

of national prosperity and individual happiness . . ."

From . . .

An Address to the Middle Classes. |

Lovett rose to political prominence as founder of the

Anti-Militia Association. On being drawn for the Militia he

refused to serve or to pay for a substitute on the ground that he

was unrepresented in Parliament. The authorities responded by

seizing and later selling his household furniture, but his protest

resulted in the subject being discussed in the House of Commons

where fear of an epidemic of "the no-vote no-musket plan" led

to the balloting system being abandoned. Lovett also became active in

trade unionism through the Metropolitan Trades Union, and

through Owenite socialism. In 1831, during the Reform Act

agitation, he helped to form the National Union of the Working

Classes with radical colleagues

Henry Hetherington and

James Watson.

After the passage of the Reform Act (1832) he and Hetherington campaigned

to repeal taxes on newspapers, known as the "War of the Unstamped".

In 1836, in consequence of the agitation, the 4d. stamp was reduced

to 1d; curiously, the Poor Man's Guardian, over which the

battle was fought, was declared by Lord Lyndhurst to be

a strictly legal publication.

|

". . . though mature reflection has caused me to

have lost faith in 'a Community of Property,' I have not

lost faith in the great benefits that may yet be

realized by a wise and judicious system of 'Co-operation

in the Production of Wealth'. The former I believe

to be unjust, unnatural, and despotic in its tendency, a

sacrificing of the intellectual energies and moral

virtues of the few, to the indolence, ignorance and

despotism of the many. The latter I believe to be

in accordance with wisdom and justice, an arrangement by

which small means and united efforts may yet be made the

instruments for upraising the multitude in knowledge,

prosperity, and freedom."

Communism vs. Co-operation,

from Life and Struggles. |

Another notable achievement was the London Working Men's

Association (LWMA). Founded in June 1836 by Lovett and several

radical colleagues including Henry

Hetherington, the LWMA was to exercise an influence on public

affairs out of all proportion to its membership which, between 1836

and 1839, amounted to a mere 279 working men and 35 honorary members;

among the latter were Francis Place, James O’Brien, Dr John Black,

Robert Owen, W. J. Fox and the

later Chartist leader, Feargus O'Connor, with whom Lovett often

clashed through their opposing views on 'moral' vs.

'physical' force Chartism. Other honorary members

included radical MP's, but overall the LWMA was a working-class

organisation, unlike groups such as the 'Birmingham Political

Union' whose executive was dominated by the middle-class. The

original purpose of the LWMA was education, but in 1838 Lovett and

fellow Radical Francis Place drafted a parliamentary bill which was

the foundation of the "Peoples' Charter", and the Association was

effectively sidetracked into Chartism.

Lovett is best remembered for his role in the

"Chartist" movement, the effects of which are with us

today. Chartism was a campaign aimed at parliamentary reform

and the correction of the inequities of the

Reform Act of 1832, following which the great majority of the U.K.'s

adult population continued to be disenfranchised.

The "Charter" aimed to remedy this wrong. It was a Bill that

addressed in

detail the arrangements for wider enfranchisement (but not of

women), registration and annual parliamentary elections, and over a million persons signed a petition in its favour.

Within a society ruled mainly by a privileged minority, its effects

were sensational; the ruling classes came to quake at the very name of Chartism,

which explains the draconian measures taken by the authorities to

stamp it out.

|

". . . women are the chief

instructors of our children, whose virtues or vices will

depend more on the education given them by their mothers

than on that off any other teacher we can employ to

instruct them. If a mother is deficient in

knowledge and depraved in morals, the effects will be

seen in all her domestic arrangements; and her

prejudices, habits, and conduct will make the most

lasting impression on her children, and often render

nugatory all the efforts of the schoolmaster. If,

on the contrary, she is so well informed as to

appreciate and second his exertions, and strives to fix

in the minds of her children habits of cleanliness,

order, refinement of conduct, and purity of morals, the

results will be evident in her wise and well-regulated

household. But if, in addition to

these qualities, she be richly stored with intellectual

and moral treasures, and makes it her chief delight to

impart them to her offspring, they will, by their lives

and conduct, reflect her intelligence and virtues."

From

Chartism (1840). |

The Bill was signed by Lovett and

five other LWMA members, along with six Radical MPs

including Daniel O'Connell, another of Lovett's uncomfortable

bedfellows. The question of the Bill's authorship is unclear,

with

both Francis Place and Lovett later claiming credit for its

drafting; but the work

of writing and rewriting the document several times — no light

task — fell to Lovett. It was eventually published in May 1838,

accompanied by an address composed by Lovett, in which he

characteristically dwelt on self-government as a means to

"enlightenment."

Chartism's most active years fell during the

following decade when three attempts were made to have the Charter

enacted by Parliament. Following the last, in 1848, Chartism

fell into decline. The movement lingered on until the late

1850s, sustained

principally by the commitment, vitality and oratory of Ernest Jones.

|

" . . . . in an age when the mass of the working

classes were without either organisation or political

experience, they were not easily pursued together. The struggle

between the conflicting interests of economic reform and political

democracy, corresponding as it did to a difference in outlook

between north and south, and to the rival policies of revolution and

persuasion, ultimately broke up the [Chartist] movement."

From R. H. Tawney's

Introduction

to Lovett's autobiography. |

Like most leading Chartists, Lovett was arrested and

imprisoned. In February 1839 the first Chartist Convention met

in London, and on 4 February 1839 unanimously elected Lovett as its

Secretary. The Convention later moved to Birmingham.

Many supporters gathered in the city's Bull Ring where the local

authority had prohibited assembly, which was broken up with much

violence by police drafted in from London for the occasion.

The Convention condemned the police violence in breaking up what

have become known as "The Bull Ring riots", and posted placards

which described them as a "bloodthirsty and unconstitutional force".

Lovett, as secretary, accepted responsibility for the placards, and

was arrested with James Watson, who had taken the placards to be

printed. He was held in custody for nine days before he could

secure bail, during which time he was treated as a convicted felon.

|

". . . . I was accordingly locked up in a dark cell, about

nine feet square, the only air admitted into it being through a

small grating over the door, and in one corner of it was a pailful

of filth left by the last occupants, the smell of which was almost

overpowering. There was a bench fixed against the wall on

which to sit down, but the walls were literally covered with water,

and the place so damp and cold, even at that season of the year,

that I was obliged to keep walking round and round, like a horse in

an apple-mill, to keep anything like life within me."

William Lovett, from Life

and Struggles. |

Lovett was tried on 6 August 1839 at the Warwick assizes for

"seditious libel" (in fact, for insulting the police). He

defended himself, was convicted and sentenced to twelve months'

imprisonment. During his term in Warwick Jail ― and despite

numerous appeals to the Secretary

of State for

leniency, some made by notable people ― he and Collins were

subjected to abysmal conditions which, in Lovett's case, permanently

affected his already fragile health. That said, in May 1840 they refused a government offer of

early release if they would be bound over to good behaviour for the

remainder of the term; Lovett and Collins believed to have accepted

this offer would have constituted an admission of guilt where none

in fact lay. On 25th July, 1840, the pair

were released and were entertained at a banquet at the White Conduit

House by the combination committee and the Working Men's

Association.

|

In the brief sketch I have given of our treatment in

Warwick Gaol, most persons must be struck with the

immense power for evil which our unpaid magistracy

possess—a power to obstruct all mitigation of suffering,

and to give, if they choose, a two-fold severity to the

law. For let two persons, in two different counties, be

tried for similar offences before the same judge, and

condemned under the same Act to suffer similar

penalties, owing to the power possessed by the

magistracy, the punishment of the one person may be

two-fold more severe than that of the other.

William Lovett, from Life

and Struggles. |

While in prison Lovett and Collins wrote "Chartism, a New Organisation of the People", which focused on

Chartist Education.

|

". . . We justly complain of your utter disregard and

seeming contempt of the wants and wishes of the people,

as expressed in the prayers and petitions they have been humbly addressing to you for a number of

years past. For, while they have been complaining of the unequal,

unjust, and cruel laws you have enacted—which, in their operation,

have reduced millions to poverty, and punished them because they

were poor—you have been either increasing the catalogue, or mocking

their expensive and fruitless commissions, or telling them that 'their poverty was beyond the reach of legislative enactment'

. . . ."

From a

Remonstrance

to the Commons House of Parliament (1842). |

Following his release, Lovett retired from

politics and in 1841 formed the "National Association for Promoting

the Political and Social Improvement of the People", an educational

body that was to implement his "New Move" educational initiative

through which he hoped poor workers and their children would be able

to better themselves. The New Move was to be funded through a

1 penny per week subscription paid by those Chartists who had signed

the national petition. Hetherington and Place supported the

move, but O'Connor opposed the scheme in the Northern Star,

believing that it would distract Chartists from the main aim of

having the petition implemented.

The New Move was unable to

generate the popular support that Lovett had hoped for.

Membership was small and education was limited to Sunday

schools. The National Association Hall was opened in 1842.

Many lectures were given there over the years by W. J. Fox, J. H.

Parry,

Thomas Cooper, and others, and secular schools also carried

on, but this Hall closed in 1857 when the lease was (forcibly)

acquired by the wealthy proprietor of the adjoining "gin-palace."

According to W. J. Linton, "Lovett

was impracticable; and his new association, after obtaining a few

hundred members, dwindled into a debating club, and their hall

became a dancing academy, let occasionally for unobjectionable

public meetings."

|

"The real hero of the [Chartist] movement

is Lovett. Perhaps the best clue to his character

is his belief, probably derived from Owen, in the virtue

of ideas. To him it was sufficient to have given

birth to an idea; if it was right it would prevail in

the end."

Julius West . . . ."A

History of the Chartist Movement." |

Throughout his life, Lovett believed

strongly in the merits of temperance and sobriety ― in 1829 he drew

up a petition for the opening of the British Museum on Sundays, its

opening sentence running . . . "Your petitioners consider that one

of the principal causes of drunkenness and dissipation on the

Sabbath is the want of recreation and amusement." In later

life he taught anatomy (also publishing a school-book on the

subject), ran a book shop (unsuccessfully ― he recognised his

lack of talent as a businessman) and wrote his autobiography, which

he published shortly before

his death in 1877. "The Life and Struggles of William Lovett"

is indeed a notable working-class autobiography that has gone

through numerous editions; that transcribed here (1920) includes a

valuable Introduction by the distinguished social historian, R. H.

Tawney (1880-1962).

|

". . . the relics of paganism formed a part of

Christian worship, as well as Judaism, or the laws and customs and

the recorded sayings and doings of a half-savage people; and these

old Jewish records have ever formed texts, incentives, and apologies

for barbarities innumerable, opposed to the religion of Christ. War

has ever met with countenance and apology in these old records,

despite the assertion of Christ that his mission was one of peace,

brotherhood, and forgiveness of injuries; and slavery, bigamy, concubinage, oppression, vindictiveness, and cruelty have

countenance and apology in their pages."

Lovett on

Christianity. |

William Lovett was buried in London's

Highgate cemetery, joining Michael Faraday, George Eliot, Karl Marx,

Christina Rossetti and many other notables who lie in that place.

His last years were dogged by ill-health ― in part attributable to

his despicable treatment years earlier while imprisoned in Warwick Goal ― and by poverty; ". . . . it does, however, jar upon my feelings

to think that, after all my struggles, all my industry, and, I may

add, all my temperance and frugality, I cannot earn or live upon my

own bread in my old age."

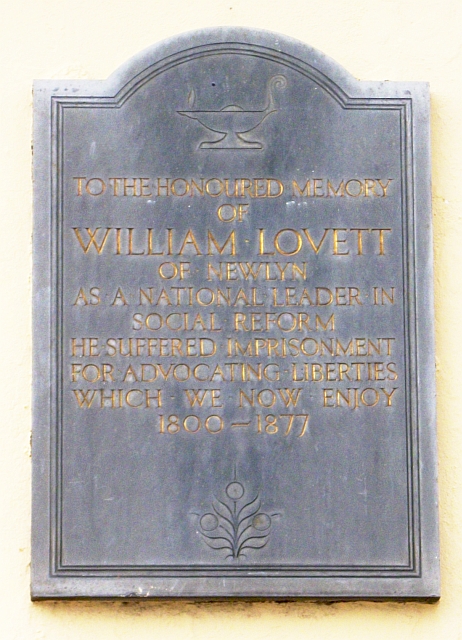

Plaque on the wall of 'The Smugglers Restaurant',

Newlyn harbour, Cornwall.

© Copyright

Bob Embleton and licensed for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

As for Chartism, 'petitions' presented to

Parliament demanding the Charter were rejected in 1839, 1842, and

1848. Following its 1848 failure, and

aggravated by other factors such as divisions within the movement and an upturn

in the nation's economic prosperity resulting in improved employment,

Chartism gradually lost

its impetus and withered. But although the movement failed

during its lifetime,

the objectives sought by our

Chartists ancestors were gradually achieved over the years and

are now clearly discernible within U.K. electoral law. Thus,

in the long term, Chartism became ― both to its credit and to our

benefit ― the victory of the vanquished . . . .

|

". . . . Democracy, in its just and most extensive sense, means

the power of the people mentally, morally, and politically directed,

in promoting the happiness of the whole human family, irrespective

of their country, creed, or colour. In its limited sense, as regards our own country, it must evidently embrace the political power of

all classes and conditions of men, directed in the same wise manner,

for the benefit of all. In a more circumscribed sense, as regards

individuals, the principle of democracy accords to every individual

the right of freely putting forth his opinions on all subjects

affecting the general welfare; the right of publicly assembling his

fellow-men to consider any project he may conceive to be of public

benefit, and the right of being heard patiently and treated

courteously, however his opinions may differ from others . . ."

From an

Address to the

Chartists of the United Kingdom (1845) |

|