|

"The liberty of opinion is the most sacred of all

liberties,

for it is the basis of all..."

ERNEST JONES,

Notes To The

People.

――――♦――――

|

|

"I tell you, never

was a truth propounded that did not make the world richer than it was

before. It never dies, though its utterer may perish piecemeal;

and, though no fruit may seem to grow from its teaching, it has leavened

mankind none the less, and the great heart of humanity will swell sooner

or later with that germ of truth, and flash some bright new glory on the

world! . . . Believe me, no great man has ever toiled and perished,

without doing good. To such men, to hopeless martyrs, who passed

unrecognised and perished unaided, we owe — aye! every liberty we have .

. . ."

ERNEST JONES,

The Cabinet, 27 Aug. 1859.

――――♦―――― |

|

|

|

ERNEST

JONES

Chartist and reformer

1819 - 1869 |

|

|

The Prelate bows his cushioned knee;

Oh! the Prelate's fat to see;

Fat the priests who minister,

Fat, each roaring chorister,

Prebendary, Deacon, Lector,

Chapter, Chanter, Vicar, Rector,

Curate, Chaplain, Dean and Pastor,

Verger, Sexton, Clerk, Schoolmaster,

From mitre tall, to gold-laced hat,

Fat's the place—and all are fat.

From...."Beldagon

Church" |

|

|

ERNEST

JONES,

THE CHARTIST ADVOCATE.

BY

GEORGE JACOB

HOLYOAKE

(from 'SIXTY

YEARS OF AN AGITATOR'S LIFE')

I

OWN I have the sympathies of Old Mortality. In

my time I have perpetuated the memory of many unregarded heroes, who gave

their strength, and in some cases their lives, in defence of the people

who had forgotten, or who had never inquired, to whom they owed their

advantages.

ERNEST CHARLES

JONES will, however, be long remembered by

Chartist generations. He was the son of a Major Jones, of high

connections, who had served in the wars of Wellington, and was at

Waterloo. He was subsequently equerry to the Duke of Cumberland,

afterwards Ernest I. of Hanover, and uncle of Queen Victoria.

Major Jones's mother was an Annesley, daughter of a squire of Kent.

His only son, Ernest, was born in Vienna, in January, 1819. His

father having an estate in Holstein, on the border of the Black Forest,

Ernest Jones passed his boyhood there, and in 1830, when eleven years old,

he set out across the Black Forest, with a bundle under his arm, to "help

the Poles." With a similar precarious equipment, he in after years

set out to help the Chartists. He was educated at St.

Michael's College in Luneburg, where only high-caste students were

admitted, and where he won distinction by delivering an oration in German.

In 1838, he became a regular attendant at the English Court, where he was

presented by the Duke of Beaufort. He married into the aristocratic

family of Gibson Atherley, of Barfield, Cumberland, the name being borne

by his son Atherley Jones, now member of Parliament. We of the

Chartist times all knew the gentle lady who lived in Brompton during the

dreary days of her husband's frightful imprisonment.

In 1844, Ernest Jones was called to the Bar of the Inner

Temple. All along he had high tastes and high prospects. Thus

he was reared under circumstances which did not render it necessary that

he should have any sympathy with the people. But the inspiration of

poetry came to him. The influence of Byron may be seen in his verse.

He had no mean capacity of song. With better fortune than befell him

when he had cast his lot with Chartism, and with more leisure, he would

have been a poet of mark: but he threw fortune away. His family did

not like the idea of his being a Chartist rhymer. His uncle, Holton

Annesley, offered to leave him £2,000 a year if he would abandon Chartist

advocacy. If not, he would leave the fortune to another—and he did.

Mr. Jones must have had in him elements of a valorous integrity to refuse

that splendid prospect. He knew well what he was about, and that the

service of the people would not keep him in bread. They whom he

served were not able to do it—they had too many needs of their own.

He had declined his uncle's wealthy offer in terms of noble but disastrous

pride, and the fortune he relinquished was given to his uncle's gardener.

Though he had chosen penury, he retained the patrician taste natural to

him, and made a point of not taking payment for his speeches and

addresses. There was more pride than sense in this. Those who

consumed his days in travelling and his strength in speaking could and

would have made him some remuneration. Without it his home must be

unprovided. Making a speech has as fair a claim to payment as

writing an article. Honest oratory is as much entitled to costs as

honest literature. Mr. Jones often walked from town to town without

means of procuring adequate refreshment by day or accommodation by night.

On some occasions an observant Chartist would buy him a pair of shoes,

seeing his need of them. Ernest Jones published the People's

Paper—the sale of which did not pay expenses. The sense of debt

was a new burden to him. On one occasion when I printed for him, and

he was considerably in arrears, he said, "I must go to my friend

Disraeli." An hour later he returned, and handed my brother Austin

three of several £5 notes. He had others in his hand. That

politic Minister inspired many Chartists with hatred of the Whigs, whom he

himself disliked, because they did not favour his circuitous pretensions;

and when he found Chartists of genius having the same hatred, he would

supply them with money, the better to give effect to it. I never

knew any Chartist in the habit of taking money, who took it for the

abandonment of his principles; nor do I believe Disraeli ever gave it them

for that purpose. Their undiscerning hatred answered Tory ends.

|

|

|

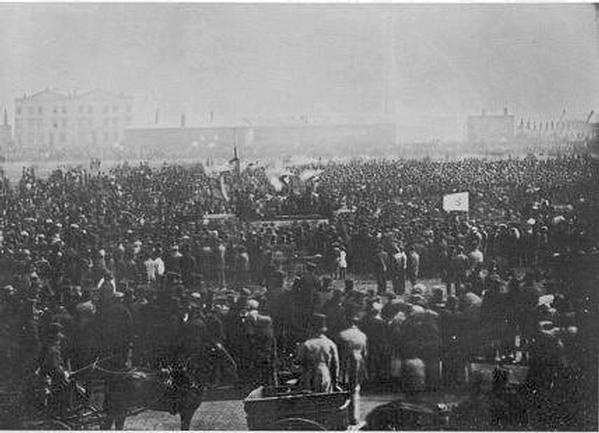

Chartist demonstration, Kenington Common,

1848. |

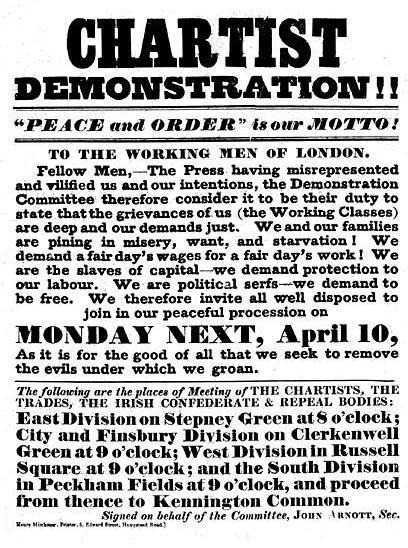

It was July, 1848, when Mr. Jones was sentenced to two years'

solitary imprisonment, and to find two sureties of £100 each and himself

£200 for three years after his release—for saying, "Only organise, and you

will see the green flag floating over Downing Street; let that be

accomplished, and John Mitchell shall be brought back again to his native

country, and Sir G. Grey and Lord John Russell shall be sent out to

exchange places with him." This was simply amusing, and there was no

more danger of this happening than of a flock of pigeons stopping a

railway train. In the same speech for which he was condemned, he

gave the same advice to the meeting that I had given to the delegates to

the Convention in the John Street Hall, on the night before the 10th of

April, 1848.

When Jones was imprisoned, it was sought to humiliate him.

The Whigs did it, but the Tories would have done the same—yet the Whigs

were more bound to respect the advocates of the people. Jones was

required to pick oakum. Being a gentleman, he refused to be degraded

as a criminal. Politics was not a crime. In the case of

Colonel Valentine Baker, the Government had just respect for a 'gentlemen;

but not when the gentlemen was the political advocate of the poor, though

Jones was socially superior to Baker.

|

"Which nation?" asked the younger

stranger, "for she [Queen

Victoria] reigns over two."

The stranger paused; Egremont was silent, but looked

inquiringly.

"Yes," resumed the younger stranger after a moment's

interval. "Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse

and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other's habits,

thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in

different zones, or inhabitants of different planets; who

are formed by a different breeding, are fed by a different

food, are ordered by different manners, and are not governed

by the same laws."

"You speak of―" said Egremont, hesitatingly.

"THE RICH

AND THE POOR."

――――♦――――

From . . . Sybil, or

The Two Nations, by Benjamin

Disraeli (1845) |

Mr. Jones was kept in solitary confinement on the silent

system—enforced with the utmost rigour for nineteen months. He

complied with all the prison regulations, excepting oakum picking.

That he steadfastly refused, as he would never bend himself to voluntary

degradation. To break his firmness on this point he was again and

again confined in a dark cell and fed on bread and water.

When suffering from dysentery, he was put into a cell in an

indescribable state from which a prisoner who died from cholera had been

carried. It may be reasonably assumed that it was intended to kill

him. The cholera was then raging in London, and, had Jones died, no

question would have been asked. Still the authorities never

succeeded in making him pick oakum.

In the second year of his imprisonment he was so broken in

health that he could no longer stand upright, and was found lying on the

floor of his cell. Only then was he taken to the hospital. He

was told, if he would petition for his release and abjure politics, the

remainder of his sentence would be remitted. This he refused, and he

was sent back to his cell. Let anyone consider what those two dreary

years of indignity, brutality, peril, and solitude must have been to

a man like Ernest Jones—nervous, sanguine, ambitious, with his fiery

spirit, fine taste, and consciousness of great powers—and restrain if he

can admiration of that splendid courage and steadfastness.

Unregarded, uncared for, he maintained his self-respect. Thomas

Carlyle went to look at the caged Chartist through the bars of his prison,

and increased, by his heartless and contemptuous remarks, public

indifference to the fate of the friendless prisoner. Carlyle wrote:

"The world and its cares quite excluded for some months to come, master of

his own time, and spiritual resources to, as I supposed, a really enviable

extent." This shows that, like meaner men, Carlyle could write

without facts, or even inquiring for them. Ernest Jones, "master of

his own time," had to pick oakum, or spend his days in a dark cell.

Thus his "spiritual resources" were limited. He was refused a Bible

even, and had to write with his blood. His "really enviable"

condition was that of knowing that his wife was ignorant whether he was

dead or alive, and he was denied the knowledge what fate in the cholera

season had befallen her or his children, for whom no provision existed.

In his savage imprisonment he did write poems, but it had to

be done with his own blood—not from sensationalism, but from necessity,

pen and ink being denied him. Undaunted, he returned on his

liberation to his old advocacy of the people. Mr. Benjamin Wilson,

of Salterhebble, Halifax, who knew Jones well, has given many facts not

before known of his career in the "Struggles of Old Chartists."

|

|

|

Jones in later life, ca. 1865. |

Ernest Jones and I were associated in Chartist agitation

while it lasted. I was a visitor at his fireside at Brompton.

Mrs. Ernest Jones, a lady of great refinement, shared the

vicissitudes of his Chartist days, which shortened her own. Mr.

Jones left London in 1859, and went to Manchester with a sad heart.

Practice at the Bar had to be won. One night, after attending the

court at Leeds, he was met by Mr. Moses Clayton, who found he had no home

to go to. A home was found him at Dr. Skelton's, and a brief

also next day. He had come to the resolution that night that he

would see no morning. Afterwards better fortune came to him.

He had the chance of being member for Dewsbury. He was nearly

elected member for Manchester, and the reversion of the seat to him was

likely when he suddenly died. His grand energy, fatigue, and

exposure killed him. Had he reached Parliament, he had all the

qualities which promised a great career there. Shortly before his

death he spent some hours with me in my chambers in Cockspur Street,

overlooking Trafalgar Square, discussing a favourite theory of his—the

manner in which an actor on the stage of the world should quit it.*

In every workshop in Great Britain, in mine and mill, and in

other lands where his name was familiar, there was sadness when his death

was known. His friend in many a conflict, George Julian Harney, sent

from America to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle an impassioned

account of the effect of the news on him as he read it in a telegram in

Boston.

Mr. Jones had a strong musical voice, energy and fire, and a

more classic style of expression than any of his compeers in agitation.

When he spoke at the grave of Benjamin Rushton of Ovenden, he began:—"We

meet to-day at a burial and a birth—the burial of a noble patriot is the

resurrection of a glorious principle. The foundation stones of

liberty are the graves of the just; the lives of the departed are the

landmarks of the living; the memories of the past are the beacons of the

future."

Despite his popular sympathies and generous sacrifices for

the people, the patrician distrust of them, now and then, broke out, as

when he wrote:—

|

"Ill fare the men who, flushed with sudden power,

Would uproot centuries in a single hour.

Gaze on those crowds—is theirs the force that saves?

What were they yesterday?—a horde of slaves!

What are they now but slaves without their chains?

The badge is cancelled, but the man remains." |

There is some truth in these lines. The abatements I take to be

these:—1. You can't "uproot centuries" if you try. 2.

The "crowds" are always better than they look. 3. The "slaves"

are always free in spirit long before they get rid of "their chains." 4.

When the" badge is cancelled," the "man" who "remains " generally turns

out a gladsome, practical creature.

In the nobler vein which so well became him, he vindicated

with a poet's insight his own career:—

|

"Men counted him a dreamer? Dreams

Are but the light of clearer skies—

Too dazzling for our naked eyes.

And when we catch their flashing beams

We turn aside and call them dreams.

Oh! trust me every thought that yet

In greatness rose and sorrow set,

That time to ripening glory nurst,

Was called an 'idle dream' at first." |

Mr. Morrison Davidson has published the most comprehensive sketch of the

career of Ernest Jones which has appeared, and a noble volume might be

made of his poems, speeches and political writings. Because he

opposed middle-class projects and broke up their meetings, little

attention was paid to his views by those who would have been most

impressed by them. Before their day he was as well informed as Karl

Marx or Henry George on questions of capital and land, and held eventually

wider views of co-operation than were advocated in his time. It

would have been economy to mankind to have pensioned Ernest Jones, that he

might have devoted his genius to oratory, literature, and liberty.

Those of this generation who have not in their memory any

instance of Ernest Jones's eloquence, may see it in the following passage

from his Lecture on the Middle Ages and the Papacy.

"You have been

told that the Church in the Dark Ages was the preserver of learning, the

patron of science, and the friend of freedom. The preserver of

learning in the Dark Ages! It was the Church that made these ages dark.

The preserver of learning! Yes, as the worm-eaten oak chest preserves a

manuscript. No more thanks to them than to the rats for not

devouring its pages. It was the Republics of Italy and the Saracens

of Spain that preserved learning—and it was the Church that trod out the

light of those Italian Republics. The patron of science! What? When

they burned Savonarola and Bruno, imprisoned Galileo, persecuted Columbus,

and mutilated Abelard? The friend of freedom! What? When they crushed the

Republics of the South, pressed the Netherlands like the vintage in a

wine-kelter, girdled Switzerland with a belt of fire and steel, banded the

crowned tyrants of Europe against the Reformers of Germany, and launched

Claverhouse against the Covenanters of Scotland? The friend of freedom!

When they hedged kings with a divinity! Their superstitions alone upheld

the rotten fabric of oppression. Their superstitions alone turned

the indignant freeman into a willing slave and made men bow to the Hell

they created here by a hope of the Heaven they could not insure hereafter.

There is nothing so corrupt that the Papacy has not befriended, and but

one gleam of sunshine flashes across the black picture, in the

architecture of its churches, the painting of its aisles, and the music of

its choirs."

Note: After his death an "Ernest Jones Fund" was

proposed. Lord Armstrong, then Sir William, sent two guineas to the

Punch office, which was sent to me for the Fund.

――――♦―――― |

|

ERNEST JONES

from

"The

Chartist Movement"

by

Mark Hovell and Professor T. F. Tout.

"Like [Feargus] O'Connor, [Ernest] Jones was a man of family, education, and good social position. His

father, Major Jones, a hussar of Welsh descent, had fought bravely

in the Peninsula and at Waterloo, and became equerry to the most

hated of George III.'s sons, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, after 1837

King of Hanover. The godson and namesake of the unpopular duke,

Ernest Jones was born at Berlin, brought up on his parents' estate

in Holstein, and educated with scions of Hanoverian nobility at Lüneburg.

He came to England with his family in 1838, but his upbringing was

shown not only in his literary tastes and wide Continental

connections, but by his very German handwriting and the constant use

of German in the more intimate and emotional entries in his

manuscript diaries. He entered English life as a man of

fashion, moving in good society, assiduous at court, where a duke

presented him to Queen Victoria, marrying a lady "descended from the Plantagenets" at a "dashing wedding" in St. George's, Hanover

Square. He was gradually weaned from frivolity by ardent

literary ambitions, but was soon terribly discouraged when

publishers refused to publish, or the public to buy, his verses,

novels, songs, and dances. In 1844 he was called to the Bar, but hardly took his

profession seriously. Domestic and financial troubles soon followed. His father and mother died and his speculations failed. In 1845

there was an execution in his house; he was compelled to hide from

his creditors and pass through the bankruptcy court. He had

now to seek some sort of employment, but apparently failed to find

anything congenial to his mystic, dreamy, enthusiastic temperament. He

does not seem to have been destitute, but he lived in a fever of

excitement and alternating hope and depression. He felt cut away

from his bearings, living without motives, principles, or ambitions,

until be began to find a new inspiration in attending Chartist

meetings. He was soon so fully a convert that, when his first

brief came from the solicitors, it gave him far less satisfaction

than the applause with which his Chartist audiences received his

vigorous recitation of his poems, and the honour of dining four or

five days running with O'Connor. Yet many years later he could

inspire the boast that he had "abandoned a promising, professional

career and the allurements of fashionable life in order to devote

himself to the cause of the people." He assiduously attended

committees and rushed all over the country to make speeches at

meetings. He offered himself as a candidate for the next

Convention because he wished to see "a liberal democracy instead of

a tyrannical oligarchy." He reveals his sensitive soul in his

diary.

I am pouring the tide of my songs over England, forming the tone of

the mighty mind of the people. Wonderful! Vicissitudes of

life — rebuffs and countless disappointments in literature — dry toil of

business — press of legal and social struggles — dreadful domestic

catastrophes — domestic bickerings — almost destitution — hunger — labour in

mind and body — have left me through the wonderful Providence of God

as enthusiastic of mind, as ardent of temper, as fresh of heart and

as strong a frame as ever! Thank God!

I am prepared to rush fresh and

strong into the strife or struggle of a nation, to ride the torrent

or to guide the rill, if God permits."

Jones was altogether composed of finer clay than O'Connor. His real

sincerity and enthusiasm for his cause were quite foreign to the

temperament of his chief. But there were certain obvious

similarities between these two very different types of the "Celtic

temperament." Not only in sympathetic desire to find remedies for

evil things, but in deftness in playing upon a popular audience, in

violence of speech, incoherence of thought, and lack of measure,

Jones stood very near O'Connor himself. Henceforth he was second

only to O'Connor among the Chartist leaders. For the two years in

which he found it easy to work with his chief, Jones's loyal and

ardent service did much to redeem the mediocrity of O'Connor's lead. In his political songs he set forth, always with fluency and

feeling, sometimes with real lyrical power, the saving merits of

the Land Scheme. Nor was he less effective as a journalist and as a

platform orator. Not content with the publicity of the Northern

Star, whose twinkle was already somewhat dimmed, O'Connor set up

in 1847 a monthly magazine called The Labourer, devoted to

furthering the work of the Land Company. In this new venture Jones

was O'Connor's right-hand man. And both in prose and verse no

perception of humour dimmed the fervour of his periods:

Has freedom whispered in his wistful ear,

"Courage, poor slave! Deliverance is near?"

Oh! She has breathed a summons sweeter still,

"Come! Take your guerdon at O'Connorville. " |

. . . . After the Chartist collapse of 1848 there remains nothing

save to write the epilogue. But ten more weary years elapsed

before the final end came, for moribund Chartism showed a strange

vitality, however feeble the life which now lingered in it.

But the Chartist tradition was already a venerable memory, and its

devotees were more conservative than they thought when they clung

hopelessly to its doctrine. It is some measure of the

sentimental force of Chartism that it took such an unconscionably

long time in dying. . . .

. . . . Ernest Jones gradually stepped into O'Connor's place.

His imprisonment between 1848 and 1850 had spared him the necessity

of violent conflict with his chief, and after his release he had

tact enough to avoid an open breach with him. His aim was now

to minimise the effects of O'Connor's eccentric policy, and after

1852 he was free to rally as he would the faithful remnant. He

wandered restlessly from town to town, agitating, organising, and

haranguing the scanty audiences that he could now attract. His

pen resumed its former activity. He sought to replace the

fallen Northern Star by a newspaper called Notes to the

People. Jones was an excellent journalist, but there was

no public which cared to buy his new venture. It was in vain

that he furiously lashed capitalists and aristocrats, middle-class

reformers, co-operators, trades unionists, and, above all, his

enemies within the Chartist ranks. He reached the limit when,

under the thin disguise of the adventures of a fictitious demagogue

called Simon de Brassier, he held up his old chief to opprobrium,

not only for his acknowledged weaknesses, but as a self-seeking

money-grabber and a government spy. It was in vain that Jones

denied that his political novel contained real characters and

referred to real events. Simon de Brassier's sayings and

doings were too carefully modelled on those of O'Connor for the

excuse to hold water. But however great the scandal excited,

it did not sell the paper in which the romance was published.

After an inglorious existence of a few months Notes to the People

came to an end, and the People's Paper, Jones's final

journalistic venture, was not much more fortunate. It dragged

on as long as sympathisers were found to subscribe enough money to

print it. When these funds failed it speedily collapsed.

The scandal of Simon de Brassier showed that Jones was almost

as irresponsible as O'Connor. In many other ways also the new

leader showed that he had no real gift for leadership. He was

fully as difficult to work with, as petulant and self-willed, as

O'Connor had ever been. He threw himself without restraint

into every sectional quarrel, and under his rule the scanty remnant

of the Chartist flock was distracted by constant quarrels and

schisms. Meanwhile the faithful few still assembled annually

in their Conventions, and the leaders still met weekly in their

Executive Committees. But while each Convention was torn

asunder by quarrels and dissensions, the outside public became

stonily indifferent to its decisions. Jones himself retained a

robust faith in the eventual triumph of the Charter, but he soon

convinced himself that its victory was not to be secured by the

co-operation of his colleagues on the Chartist Executive. He

now grew heartily sick of sitting Wednesday after Wednesday at

Executive meetings where no quorum could be obtained, or which, when

enough members attended, refused to promote "the world's greatest

and dearest cause," because minding other matters instead of minding

the Charter. He was one of the last upholders of the old

Chartist anti-middle -class programme; but he preached the faith to

few sympathetic ears. In 1852 he withdrew in disgust from the

Executive, but came back again when the Manchester Conference of

that year adopted a new organisation of his own proposing.

This Conference, however, made itself ridiculous by persisting in

the old policy of refusing to co-operate with other parties pursuing

similar ends, and after 1853 no more Conventions were held.

The release in 1854 of the martyrs of the Newport rising — Frost,

Jones, and Williams — showed that in official eyes Chartism was no

longer dangerous. For the five more years between 1853 and

1858 Jones still lectured on behalf of the Charter, and could still,

in 1858, rejoice with his brother Chartists on his vindication of

his character against the aspersions of Reynolds. With his

passing over to the Radical ranks the Chartist succession came to a

final end. . . .

. . . . Of the last Chartist leader, Ernest Jones, there is still

something to say. In 1858 he initiated a National Suffrage

Movement and accepted the presidency of the organisation established

for that end. It became, under his guidance, one of the forces

which, after a few years of lethargy, renewed the agitation for

reform of Parliament, and was a factor in bringing about the second

Reform Act of 1867. In 1861 he transferred himself from London

to Manchester, where he resided until his death, writing plays and

novels, agitating for reform, watching the movement of foreign

politics, and winning a respectable practice at the local bar.

Here his greatest achievement was his able defence of the Fenian

prisoners, convicted in 1867 of the murder of Police Sergeant Brett.

He remained poor, but obtained a good position in Radical circles,

contesting Manchester in 1868, when, though unsuccessful, he

received more than ten thousand votes. He died in January

1869, and the public display which attended his burial in Ardwick

cemetery was only second to that which had marked the interment of

O'Connor."

――――♦――――

See:

The Death and Posthumous Life of

Ernest Jones, an essay by Dr. Antony Taylor, History

Department, Sheffield Hallam University; see also

obituaries.

|

――――♦――――

|

". . . .

the condition of the scholar, the genius of the poet, the fervid eloquence

of the orator, and the courageous spirit of the patriot, whom no

prosecution could frighten from the advocacy of his principles, and whom

no threatened loss of future or seductive offers of advancement could

tempt to abandon them. He was the same from the beginning to the

end, and his life was a life of beautiful, consistency."

EDMOND BEALES

— oration at the funeral

of Ernest Jones.

|

――――♦――――

|

ON THE DEATH OF ERNEST JONES. |

|

OH! cruel Death! could'st thou not lay thine hand,

On some one less beloved in the land?

Was there not one in this vast, teeming world,

Into whose breasts thy arrows could be hurled!

Why in such dreadful haste? Had'st thou looked round,

But for one moment, Death, thou would'st have found

Those for whom none would breathe, nor sighs, nor groans,

Then why strike down our much-loved Ernest Jones!

Could'st thou not enter at some other door?

Hast thou not heard of what we had in store

For the departed one whose loss we mourn?

Hast then not heard of bitter hardships borne!

O, why not warn us of thy mission here

Ere thou did'st hurl thy darts at one so dear.

Can'st thou not see our hands uplifted now,

To place the laurels on his honoured brow!

But why thus blame thee, Death, or thus repine,

Since faith assures us that this act of thine

Hath snapped the chain, and freed the patriot bard;

His trials o'er, he's gone to his reward.

Heaven,—grown impatient at our long delays,

Of tendering our homage, help, and praise,—

Called him away, from hearts so hard and cold,

To dwell with martyrs, and the brave of old.

SAMUEL

LAYCOCK. |

|

――――♦――――

From the

RED REPUBLICAN

SATURDAY, July 20, 1850. |

|

ERNEST JONES.

THE liberation of this truly earnest and most

eloquent advocate of the rights of the people, has already called forth a

shout of joy from one end of the country to the other. But that we

are forbidden to report "news, occurrences, and events," we would tell of

the enthusiastic reception given to our friend by the Red Republicans of

London and Yorkshire. As it is, we can only express the happiness we

feel in having witnessed this act of homage on the part of the people to

one of their most truly noble defenders—to one who by his services,

sacrifices, and sufferings, has fully earned the proud distinction of

being enrolled amongst the great and good men who have

DESERVED WELL OF THEIR COUNTRY AND MANKIND.

We naturally feel no small degree of pride at being in a

position to give publicity to some of the prison-penned productions of our

friend and brother, who has kindly singled out the RED

REPUBLICAN as the medium through which to make

public a series of hymns written in his dungeon.

We must state an important fact in connection with these

hymns. At the time they were conceived in the brain of their author,

he was denied all ordinary writing materials by his pitiless jailors, but

|

"In vain did their impotent hands

Attempt his free spirit to bind." |

Ernest Jones drew blood from his own veins, and that was the ink with

which was written the hymns, No. 1 of which we this week present to our

readers. Red to the Red! Most appropriately these hymns will

grace the columns of the RED REPUBLICAN. |

SACRED HYMNS.

BY ERNEST JONES.

(Written in the blood of their author, whilst incarcerated in Tothill-fields'

Prison.)

No. I.—HYMN FOR ASCENSION DAY.

Chorus.

Freedom is risen!

Freedom is risen!

Freedom is risen to-day!

Single voice. She burst from

prison,

She burnt from prison,

She broke from her gaolers away!

Chorus.

When was she born?

How was she nurst?

Where was her cradle laid?

Single voice. In want and

scorn;

Reviled and curst;

'Mid the ranks of toil and trade.

Chorus.

And hath she gone

On her Holy morn,

Nor staid for the long workday?

Single voice. From heaven she came,

On earth to remain,

And bide with her sons alway.

Chorus.

Did she break the grave,

Our souls to save,

And leave our bodies in hell?

Single voice. To save us alive,

If we will but strive,

Body and soul as well.

Chorus.

Then what must we do

To prove us true ?

And what is the law she gave?

Single voice. Never fulfil

A tyrant's will,

Nor willingly live a slave.

Chorus.

Then this we'll do,

To prove us true,

And follow the law she gave:

Never fulfil

A tyrant's will,

Nor willingly live a slave. |

――――♦――――

|

|

|

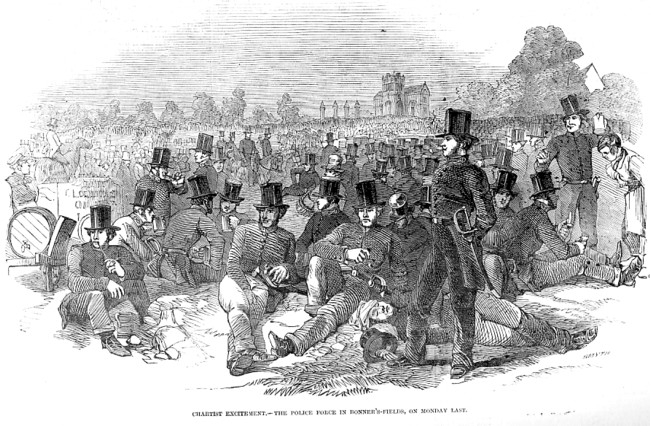

Police officers at the Chartist rally, Bonner's

Fields, which led to Jones's imprisonment.

London Illustrated News,

June 17, 1848. |

|

CENTRAL

CRIMINAL COURT.

――――♦――――

THE CHARTIST TRIALS.

On Saturday last, Francis Loony, aged thirty-four, described as a cabinet-maker, was placed in the dock charged with misdemeanour. The

Attorney-General, in stating the case to the jury, said that the prisoner

was indicted on two separate charges for attending and speaking at two

meetings on the 5th of June, the one held in Blackfriars-road, and the

other at Soho, and which were held to express sympathy with John Mitchel. The prisoner, after a lengthened trial, was found "Guilty."

On Monday morning, at ten o'clock, Lord Chief Justice

Wilde took his seat on the bench, and Ernest Charles Jones, twenty-nine, barrister-at-law,

was called upon to surrender. Having answered, he was placed at the end of

the counsel-table, and was arraigned upon an indictment charging him with

sedition, attending an unlawful assembly, and a riot, at Bishop Bonner's

Fields, on the 4th of June last.

The Attorney-General then rose, and proceeded to open the case for the

prosecution. It would be with considerable pain that he should have to lay

the circumstances of this case before the jury, for the defendant belonged

to the same profession as himself, and therefore was a person who knew

well what would be the effect of his language, not only upon the minds of

those to whom it was addressed, but also its bearing in a legal sense. He

was a person of education and reading, and therefore the jury would find

that, in the sedition he had spoken, there was not that grossness that

had been exhibited in the speeches of the others; and they would find

that it had been delivered in more measured terms, and with greater

correctness. He should not ask the jury to look at particular parts of the

defendant's speech--he should not direct their attention to particular

words, but he should put it before them as a whole, and they would see

that its entire object and meaning were, "Organise, arm, and prepare to

resist the authorities." The learned Attorney-General having, submitted

the prisoner's seditious language at length to the jury, the latter, after

a trial which lasted to six o'clock in the evening, found the prisoner

guilty.

THE SENTENCES.

The whole of the defendants who had been convicted, viz. Fussell,

Williams, Vernon, Shape, Looney, and Jones, were then placed at the bar to

receive sentence.

The Chief Justice, having addressed them on the nature of their offences,

first passed sentence upon Fussell, whom he ordered to be imprisoned upon

the charge of sedition for two years, and for the unlawful assembly for

three months; and he was, in addition, ordered to enter into his own

recognizances in £100, with two sureties in £50 each to keep the peace for

five years.

Williams was the nest sentenced to two years' imprisonment on the first

count, one week on the second, and that he also should find sureties in

the same amount as Fussell, to keep the peace for three years.

Sharpe likewise to two years for sedition, three months for the unlawful

assembly, and find the same amount of sureties as the others to keep the

peace for three years.

Vernon was also sentenced to be imprisoned for two years, and find the

same sureties as the others to keep the peace for three years.

Looney was sentenced to two years, imprisonment on the count for sedition,

two months for the unlawful assembly, and to find the same amount of

sureties as the last defendant to keep the peace for two years.

And, lastly, Jones was sentenced to be imprisoned for two years, to find

two sureties in £ 150 each, and to enter in his own recognizance in £200

to keep the peace for five years.

This closed the business of the session, and the Court then adjourned to

Monday, August 21.

|

<>

|