|

"I have looked

over Gerald Massey's Poems ―

They seem to me zealous, candid, warlike, ― intended, as they surely

are, to get up a strong feeling against the British aristocracy both

in their social and governmental political capacity."

Walt Whitman, 1855.

_____________ |

|

"His revolutionary lyrics have done

their work. The least that can be said for them is, that they

are among the very best inspired by those wild times when Feargus

O'Connor, Thomas Cooper, James [Bronterre] O'Brien and Ernest Jones

were in their glory. Of their effect in awakening and, making

all allowance for their intemperance and extravagance, in educating

our infant democracy and those who were to mould it there can be no

question."

From...

The Poetry of Mr. Gerald

Massey by John Churton Collins, 1905.

_____________ |

|

"No one ever understood the mythology

and Ritual of Ancient Egypt so well as Gerald Massey since the time

of the Ancient Philosophers of Egypt."

Albert Churchward—Preface to

Signs and Symbols of Primordial Man.

_____________ |

Pleasantly the Chime that calls to

Bridal-hall or Kirk;

But Hell might gloatingly pull for the peal

that

wakes the babes to work!

"Come, little Children," the Mill-bell rings,

and

drowsily they run,

Little old Men and Women, and human

worms who

have spun

The life of Infancy into silk; and fed, Child,

Mother, and

Wife,

The factory's smoke of torment, with the

fuel of

human life.

O weird white face, and weary bones, and

whether

they hurry or crawl,

You know them by the factory-stamp, they

wear it one

and all.

The Factory-Fiend in a grim hush waits till

all are in,

and he grins

As he shuts the door on the fair, fair world

without,

and hell begins! |

. . . . life in Tring's Silk Mill, from

Lady

Laura

|

|

|

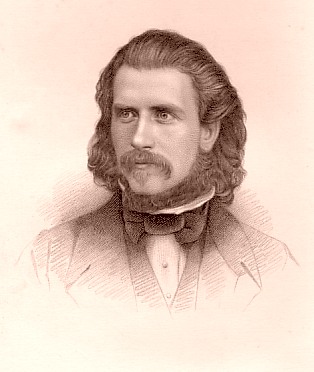

GERALD

MASSEY

(1828 - 1907)

Poet, author, lecturer and Egyptologist. |

|

|

|

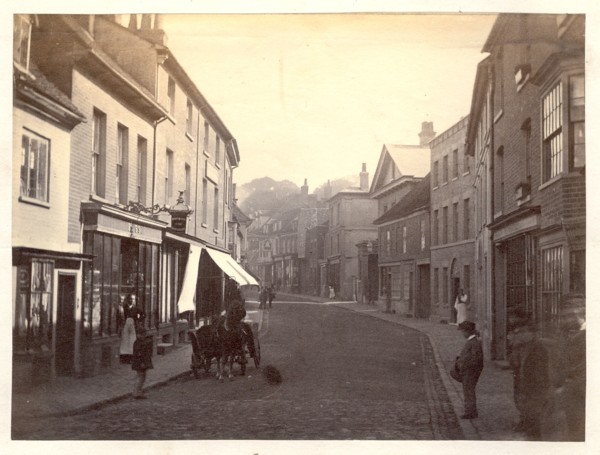

19th Century view of Tring High Street.

Photograph: Wendy Austin collection. |

|

Not by appointment do we meet delight

Or joy; they heed not our expectancy;

But round some corner of the streets of life

They of a sudden greet us with a smile.

Massey from....The

Bridegroom of Beauty |

|

|

Known in his

home town (in Hertfordshire, England) as "Tring's Poet", this extraordinary

man's enduring reputation rests more on his unparalleled ability to piece

together historical connections between cultures than on his poetry, which dates

mainly from the early part of his life. It is impossible to

categorise GERALD MASSEY

comfortably under one heading, for at different times he succeeded as a . . . .

|

Chartist and journalist,

writing in radical publications such as The Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom,

The Red Republican

and The Friend of the People (see

also

W. J. Linton,

W. E. Adams and

Karl Marx on 'Chartism'; 'What

Chartism Is' and 'James

Watson, a Memoire'). In 1886, Massey returned briefly to the

hustings, publishing a set of satirical "Election

Lyrics," which offered support to Gladstone and his

ill-fated Bill to give home-rule to Ireland;

Poet, his poetry also being published widely in North

America. In much of his poetry—particularly

his early verse—Massey protests about the lack of sorely-needed

political and social reform (see the

Poetry

section);

Essayist and poetry critic for

various Victorian

periodicals—particularly on poetry for the

Athenæum (see the

Prose

and Critical Reviews sections);

Shakespearean researcher into the

background to the Sonnets (Shakspeare

and his Sonnets;

The Secret Drama

of Shakspeare's Sonnets);

Lecturer on a wide range of subjects. During his early years,

Massey

concentrated mainly on poets and literary

personages, but later he lectured increasingly on

mythology and the origin of religious beliefs, and

on spiritualism, subjects that became absorbing interests and were—and continue—to damn him in the eyes of many;

Researcher into

the influence of ancient Egyptian beliefs on the development

of western myth, symbol, language and religion (Judaism and

Christianity—see 'Nile Genesis').

Throughout his works, when examining racial mythology, Massey

places particular emphasis on ancient Egyptian myths,

maintaining that

these developed as a necessary and fundamental central core of

belief from the earliest times, and are the roots of modern cultural

origins. He maintains that myths were founded on natural phenomena and remain

the register of the earliest scientific observation and 'the mirror of prehistoric sociology.' |

|

". . . . much

of the Christian History was pre-extant as Egyptian Mythology. I have to

ask you to bear in mind that the facts, like other foundations, have

been buried out of sight for thousands of years in a hieroglyphical

language, that was never really read by Greek or Roman, and could not be

read until the lost clue was discovered by Champollion, almost the other

day! In this way the original sources of our Mytholatry and Christology

remained as hidden as those of the Nile, until the century in which we

live."

From

Massey's lecture....

'The

Historical Jesus and the Mythical Christ'

|

Few Christians realise that the Gospels contain many points of similarity with ancient

Egyptian teachings; indeed, that they might even have been derived from

much earlier ancient Egyptian religious ritual. During the later

years of his life — from about 1870 onwards — Massey became increasingly

interested in the similarities that exist between ancient

Egyptian mythology and the Gospel stories. He studied the extensive Egyptian records housed in the British Museum, eventually teaching

himself to decipher the hieroglyphics. Following years of diligent research into

the history of Egyptian civilisation and the origins of religion, Massey

concluded that Christianity was neither original nor unique, but that the roots

of much of the Judeo/Christian tradition lay in the prevailing Kamite (ancient

Egyptian) culture of the region. By demonstrating such links are

plausible, Massey inevitably places a question mark against the

strict historical veracity of the Gospels. In the view of Dr. Alvin

Boyd Kuhn

(1880-1963), a scholar of

comparative religion who was much influenced by Massey's research:

"We

are faced with the inescapable realisation that if Jesus had been able to read

the documents of old Egypt, he would have been amazed to find his own biography

already substantially written some four or five thousand years previously."

Massey published the results of his extensive research in his 6-volume "trilogy" on the origin of

man, of civilization and of western religions—"I began my study in

1870, with the idea, which has grown stronger every year, that the human

race originated in equatorial Africa." (Massey derived an

etymology from the Egyptian af-rui-ka, "to turn toward the

opening of the Ka." The Ka is the

energetic double of every person and "opening of the Ka"

refers to a womb or birthplace. Africa would be, for the

Egyptians, "the birthplace").

But despite

today's growing interest—the books

are again available in facsimile reprint

editions—at the time of their publication the trilogy failed in

popularity due mainly to the contentious subject matter; however, it

must also be said that some of Massey's theories are poorly defined and so

supported with detail that readers found them difficult to understand.

Lacking any formal education — particularly with

regard to the need to evaluate and record his sources — and the services

of an editor, it is unsurprising that Massey's research attracted criticism, not just

with regard to the controversial nature of his conclusions but

due to a lack of clarity in how he reaches them. In:

The Book of the Beginnings,

published 1881, Massey

challenges conventional opinions of race supremacy;

The

Natural Genesis, published in 1883, Massey delves deeper into

ancient Egypt's influence on modern myths, symbols, religions and

languages. By proclaiming Egypt to be the birthplace of modern

civilisation, Massey challenges conventional theology as well as

fundamental notions of race supremacy;

Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World, published shortly before his

death in 1907 and by far Massey's most

important work, he concludes that Kamite thought was the direct progenitor of the philosophy, meta

physics, religion and science that eventually shaped Western

civilisation. "It is a work which has occupied me over thirty

years, and I shall be well content if in another century my ideas are

acknowledged as correct".

―――♦―――

Although

now largely overlooked, during the mid-Victorian era Massey was

considered a significant poet, both in Britain, where he achieved the

distinction of being awarded a civil list pension, and in North America, where he

was published widely in both books and periodicals. |

|

A happy island in a

sea of green,

Smiling it lies beneath the changing sky,

Well pleased, and conscious that each

wave

and wind

Is tempered kindly or with blessing rich:

And all the quaint cloud-messengers that

come

Voyaging the blue Heaven's summer sea,

Soft, shining, sumptuous, blown by

languid

breath,

Touch tenderly, or drop with ripeness

down.

Spring builds her leafy nest for birds and

flowers,

And folds it round luxuriant as the Vine

When grapes are filled with wine of merry

cheer:

The Summer burns her richest incense

there,

Swinging the censers of her thousand

flowers:

Brown Autumn comes o'er seas of glorious

gold:

And there old Winter keeps some greenth

of heart,

When on his head the snows of age are

white.

from....

'Craigcrook

Castle' |

|

It fell upon a

merry May morn,

I' the perfect prime of that sweet time

When daisies whiten,

woodbines

climb,—

The dear Babe Christabel was born . . .

The birds were darkling in the nest,

Or bosomed in voluptuous

trees:

On beds of flowers the happy

breeze

Had kissed its fill and sank to rest . . .

We sat and watched by life's dark stream,

Our love-lamp blown about the

night,

With hearts that lived, as

lived its

light,

And died, as did its precious gleam . . .

She thought our good-night kiss was

given,

And like a flower her life

did close.

Angels uncurtained that

repose,

And the next wakening dawned in

Heaven . . .

from....Babe

Christabel |

|

No

jewelled beauty is my love,

Yet in her earnest face,

There's such a world of tenderness,

She needs no other grace.

Her smiles, her voice, around my life

In light and music twine;

And dear, O very dear to me

Is this sweet Love of mine.

from....No

Jewelled Beauty Is My Love |

|

Come hither my brave Soldier

boy, and sit

you

by my side,

To hear a tale, a fearful tale, a glorious

tale

of pride;

How Havelock with his handful, all so

faithful,

and so few,

Held on in that far Indian land, to bear

our

England through

Her pass of bloodiest peril, and her reddest

sea

of wrath;

And strode like Paladins of old on their

avenging path.

from....Havelock's

March |

|

Massey's best poetry leans toward

the tender side of nature—often painting a succession of beautiful,

even extravagant vignettes—and to romantic scenes close to home.

Examples in this category are the ballad Babe Christabel, Massey's best-known long poem, in which he gently relates the birth, life and

death of a young child; in The Singer,

he pictures a skylark, singing softly and sweetly as it soars up into

the heavens, but the ripe, drooping ears of corn below are deaf to its song; in My Love,

Massey muses lovingly on his

wife's perfections and imperfections, a poem that I suspect makes a candid

statement of devotion for his first wife Rosina, whose imperfections

gradually became legion but who he never abandoned. There's

No Dearth of Kindness, which takes as its theme brotherly love,

is probably Massey's best-known short poem, its first four lines often appearing

in dictionaries of

quotations.

In stark contrast is Massey's political poetry, among his earliest

and arguably his

best. These exhortatory, fiery

protests, written mostly for publication in unstamped Chartist and

working-class newspapers of the period (1847-52), reflect the wrongs suffered by the masses

(A Red Republican Lyric),

their bitterness (Yet we are

Brothers Still) and utter hopelessness of a better life (Hope

On, Hope Ever!) and they display much force and vitality in the

process. Conveying as they do the feelings and sentiments of the

oppressed poor, Massey's political poems are of interest to social historians

of the period, while examples often

appear in compilations of Victorian working-class verse. For

further examples see

Early Poems and Voices of Freedom and

Lyrics of Love.

Occasionally, Massey takes as his subject a patriotic or, perversely for a champion of the

downtrodden, an imperialist episode, such as

Sir

Richard Grenville’s Last Fight, The

Death Ride and Havelock’s

March. The latter is a long narrative of the Indian Mutiny,

which Massey described as

"more properly historic photographs, rather than Poems in the Esthetic

sense" that "may have their place as illustrations in historic

records"; a perceptive comment. It's interesting to compare the first

two of these examples with Tennyson’s popular treatment of the same themes in 'The

Revenge: A Ballad of the Fleet' and in 'The Charge of the Light Brigade'.

Whereas Tennyson paints his pictures with rich but delicate strokes, Massey's

are more confused and indistinct, his poems a maze of figures. In the

opinion of a critic

writing in the Bucks

Advertiser (May, 1847), when Massey left nature and took to

the battlefield, "his sentiment is coarse, and the phraseology vulgar."

He would have done well to have taken note, for Havelock's March and

similar poems, while providing interesting views

on the headline events and sentiments of the time, are not among his best.

Craigcrook Castle,

which was

composed during 1855 when Massey held an editorial post on the Edinburgh News,

and A Tale of Eternity,

a ghost story published in 1870— and his last significant poem—are

among Massey's most accomplished poems in blank

verse.

A number of Massey's poems were set to music and

proved popular, both as hymns and songs; judging from the number of

composers that set the piece and the number of copies that remain

in circulation, No Jewelled

Beauty is my Love seems to have been a particular

favourite (it's certainly one of mine). But having sold the

copyright of his poetry to the publishers, I doubt whether Massey ever

received any royalties from the

sheet music sales.

Despite

its failings, strength and sincerity

always shines through in Massey's poetry

placing it above mere poetic merit. Of

course much of it is dated, for the concerns and conflicts

that he and his Chartist and Radical contemporaries faced, often addressing in their

verse, have long since receded below our horizon. Their battles

against

child labour, appalling factory and social conditions, the right to

protest without the fear of brutal reprisal, gender inequality and the

lack of universal suffrage, to name but some, were fought

long and hard and eventually won to our benefit (although our civil

liberties are again at risk from the all-seeing eye of modern technology

and from those who operate it!). Sadly, these

battles and those who fought them are now historic footnotes, or are forgotten.

Tennyson, who Massey greatly admired — they

met once, towards the end of the Laureate's life — described him as

"a poet of fine lyrical impulse and of a rich,

half-Oriental, imagination". . . . possibly Gerald Massey’s finest

eulogy as a poet. |

|

FOR TRUTH.

(Gerald Massey's last known poem).

He set his battle in array, and thought

To carry all before him, since he fought

For Truth, whose likeness was to him revealed;

Whose claim he blazoned on his battle-shield;

But found in front, impassively opposed,

The World against him, with its ranks all closed:

He fought, he fell, he failed to win the day

But led to Victory another way.

For Truth, it seemed, in very person came

And took his hand, and they two in one flame

Of dawn, directly through the darkness passed;

Her breath far mightier than the battle-blast.

And here and there men caught a glimpse of grace,

A moment's flash of her immortal face,

And turned to follow, till the battle-ground

Transformed with foemen slowly facing round

To fight for Truth, so lately held accursed,

As if they had been Her champion from the first.

Only a change of front, and he who had led

Was left behind with Her forgotten dead. |

―――♦―――

|

"Poverty is a cold place to write

Poetry in….. A poor man, fighting his battle of life, has little

time for the rapture of repose which Poetry demands….. Considering

all things, it may appear madness for a poor man to attempt Poetry

in the face of the barriers that surround him." |

Born in a hovel at Gamnel Wharf, Tring, on 29th May 1828, (THOMAS)

GERALD MASSEY was the eldest son of an impoverished and illiterate

canal-boatman. Massey said of himself that 'he

had no childhood,' for on

reaching the age of eight he was put to work in the Town’s silk mill where his twelve-hour days spent labouring in grim conditions added between nine

pence and one shilling and three pence to his father's meagre earnings. He later worked in Tring’s then-thriving straw

plaiting industry producing braid for the straw hat trade in nearby Luton and

Dunstable. Thanks to his mother, Mary, Massey received a scant education at a

“penny school”. Despite these tough beginnings, he learned to read

and write using the Bible, Bunyan, Robinson Crusoe and Wesleyan tracts left at

the family home. |

|

Torn from mother's arms to labour,

Fragile limbs in childhood's day—

Soon the cherub lines of beauty

From their pallid cheeks decay;

And the cankerworm of death

Makes young hearts its early prey.

......from At Eventide There Shall Be Light

|

God

shield poor little ones, where all

Must

help to be bread-bringers!

For once afoot, there's none too small

To ply their tiny fingers.

Poor Pearl, she had no time to play

The merry game of childhood;

From dawn to dark she went all day,

A-wooding in the wild-wood.

......from The Legend of Little Pearl

|

|

|

|

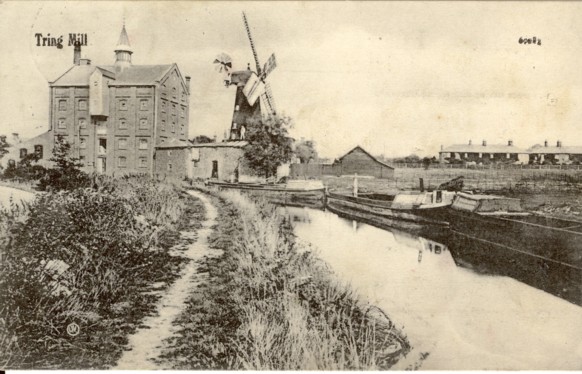

Gamnel Wharf, Tring. The steam flour mill dates from 1875.

Photo: Wendy Austin collection.

Massey's father, William, worked for the proprietor of the flour mill…

"… I know a poor old man in England who, for 40

years, worked for one firm and its three generations of proprietors. He

began at a wage of 16s. per week, and worked his way, as he grew older

and older, and many necessaries of life grew dearer and dearer, down to

six shillings a week, and still he kept on working, and would not give

up. At six shillings a week he broke a limb, and left work at last, being

pensioned off by the firm with a four-penny piece! I know whereof I

speak, for that man was my father."

GERALD MASSEY. |

|

"The

child comes into the world like a new coin with the stamp of God upon

it…the poor man’s child [is] hustled and sweated down in this bag of

society to get wealth out of it…so is the image of God worn from heart

and brow, and day by day the child recedes devil-ward. I look back now

with wonder, not that so few escape, but that any escape at all, to win

a nobler growth for their humanity. So blighting are the influences

which surround thousands in early life, to which I can bear such bitter

testimony." |

|

I

would not plod on, like these slaves of gold,

Who shut up their souls, in a dusky cave,

I would see the world better, and nobler-souled,

Ere I dream of Heaven in my green, turf-grave.

I may toil till my life is filled with dreariness,

Toil, till my heart is a wreck in its weariness,

Toil for ever, for tear-steept bread,

Till I go down to the silent dead.

But, by this yearning, this hoping, this aching,

I was not made merely for money-making.

from..... I

Was Not Made Merely for Money-Making |

|

On

Heaven, blood shall call,

Earth,

quake with pent thunder,

And

shackle and thrall,

Shall be riven asunder,

It will come, it shall come,

Impede it what may,

Up People! and welcome!

Your glorious day.

from.....The

Famine-Smitten |

|

At

the age of 15, Massey moved to London, where he found work as an errand boy, believed to have

been at the once famous

Regent Street store of Swan & Edgar.

With access to more reading material,

he flourished, absorbing the classics and other influences, including the

political writings of Thomas Paine, Volney and Howitt. He also studied French.

In later life Massey recalled that his first published poem on 'Hope' —

its author then being without

any — appeared in 1843 in the Aylesbury News, but this has not

been traced. His first

identified poem, At Eventide there shall be light,

was published in The Bucks Advertiser when he was eighteen, being attributed to "A Tring Peasant Boy".

A Tring bookseller published Massey’s first volume of poems, Original Poems and

Chansons,

in 1847, 250 copies being printed and offered for sale at a shilling each.

No copy is known to have survived (but see Early

Poems).

Throughout

his life, Massey was committed to the labourer’s cause. The revolutionary

spirit of the 1840s caught his enthusiasm and he joined the Chartists, applying

his pen in support of their cause. In 1849 he began editing

The Uxbridge Spirit of

Freedom, a paper written by working men, and was dismissed from several

jobs for publishing it.

Massey's Calvinist upbringing had taught him

that the Bible and church doctrines were true, but following his move to

London he realised that the social injustice that surrounded him was

plainly incompatible with strict church teachings. This dichotomy

was exacerbated when, having joined the Chartist movement, he came into

contact with political and religious radicals. At that time ― the

late 1840's and early 1850's ― there were discussions about and

publications refuting the strict historical veracity of biblical teachings (which continue

to this day). At that time, Massey’s sympathies veered to the

religious side of the reforming movement, where he supported the

Christian Socialists' ideals, acted as secretary to the Christian

Socialist Board and contributed to

The Christian Socialist

journal. In general, "Christian Socialism" was

taken to mean a restructuring of labour based on co-operation, joint

ownership and with increased power to the working class. F. D.

Maurice, who coined the term, intended that by these means to

Christianise socialism by opposing the unsocial Christians and the

unchristian socialists. Despite this association, however, Massey

also contributed more radical material to George Julian Harney's

Red Republican, sometimes under the pen names 'Bandiera' or 'Armand

Carrel', a venture with which the promoters of the Christian Socialist

disapproved.

|

|

|

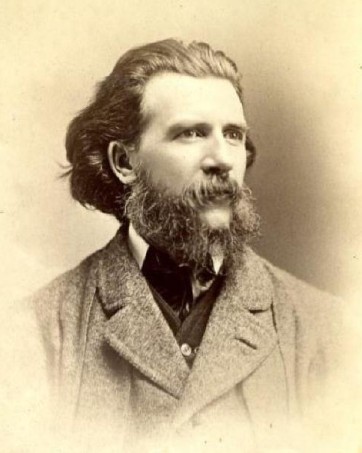

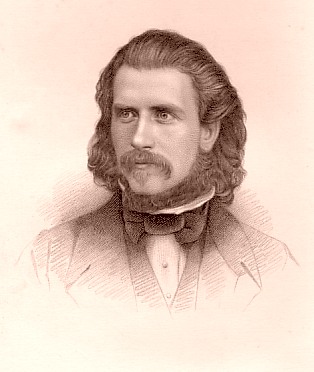

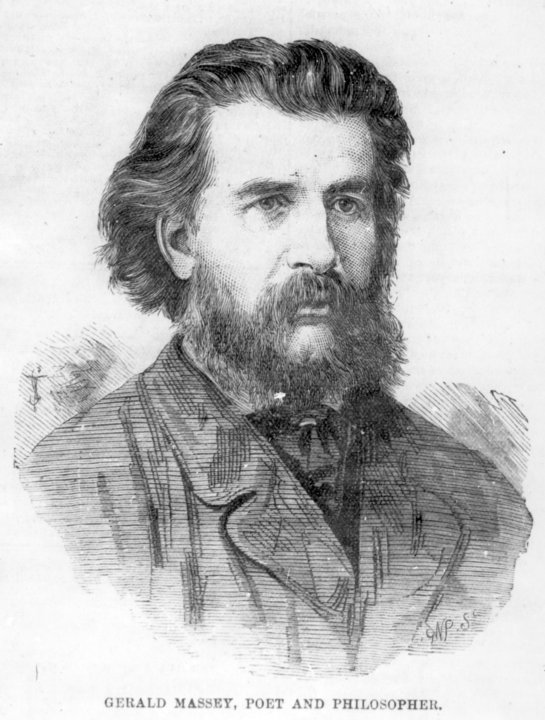

Massey, by John and Charles Watkins (ca. 1856) |

Following the virtual collapse of the Chartist

Movement by the mid 1850s, Massey continued to write poetry—much of

his poetry remaining religious in tone—together with literary articles and

reviews. His earliest surviving published

poetry collection, Voices of Freedom and Lyrics of

Love, appeared in 1851,

but it was not until his third collection, The Ballad of Babe Christabel

with other Lyrical Poems, published in 1854, that he achieved a wide

reputation as a poet. This volume went through five editions in a year and was

reprinted in New York (as Poems and

Ballads). The critic John Ruskin acknowledged Massey's talent, writing

to him; "Your education was a terrible one, but mine was far worse",

the one having suffered the bitterness of poverty, the other having been

the pampered child of wealth. War-Waits

― poems based on the Crimean War ― followed in 1855, Craigcrook Castle in 1856,

Robert Burns: a Centenary Song

(1859);

Havelock’s

March

in 1861 and, in 1870, A Tale of Eternity,

itself

a poem (and his last significant effort in the genre) dealing with the supernatural, on which

one critic commented

that ".... Weird, grisly, eerie, eldritch horror runs through the whole

current of the narrative". In 1886, in support of W. E.

Gladstone's election campaign, Massey penned a short collection of

political poems, which he published as "Election

Lyrics." Following the success of earlier compilations,

Massey collected the best of his poems into a two-volume edition, which with other material

was

published in 1889 as My Lyrical Life (Part

1, Part 2); a second, slightly extended

edition, appeared in 1896 (Part 3).

Massey's other published writing includes a detailed study of Shakespeare’s

sonnets. Following his essay on

the Sonnets published in the Quarterly Review in April, 1864,

Massey delved deeper in the mystery surrounding the characters that they

address. Shakespeare's Sonnets Never Before Interpreted

appeared in 1866 followed in 1872 by a revision, which Massey

published in a limited edition of 100 copies by subscription as The

Secret Drama of Shakespeare's Sonnets Unfolded: With the Characters Identified. A further revision,

The Secret Drama of Shakspeare's Sonnets,

which followed in 1888, exhibited an improved literary style (Massey's

spelling of 'Shakspeare' appears to have been taken from Ben Johnson,

among others, and is a recognised, though less used variant).

|

|

"That

Spanish Emperor who fancied he could have improved the plan of creation

if he had been consulted, would hardly have managed to better the time,

the place, and circumstances of Shakespeare's birth. The world would not

have been more ripe, or England more ready - the stage of the national

life more nobly peopled - the scenes more fittingly draped - than they

were for his reception. It was a time when souls were made in earnest,

and life grew quick within and large without. The full-statured sprit of

the nation had just found its sea-legs and was clothing itself with

wings." |

|

|

"It

must be borne in mind that we are endeavouring to decipher a secret

history of an unexampled kind. We can get little help, except from the

words themselves. We must not be too confident of walking by our own

light; we must rely more implicitly on that inner light of the sonnets,

left like a lamp in a tomb of old, which will lead us with the greater

certainty to the precise spot where we shall touch the secret spring and

make clear the mystery. We must ponder any the least minutiae of

thought, feeling, or expression, and not pass over one mote of meaning

because we do not easily see its significance. Some little thing that we

cannot make fit with the old reading may be the key to the right

interpretation." |

|

|

Gerald Massey.... extracts from

The Secret Drama of Shakespeare's Sonnets

Unfolded.

Among Massey's radical friends and associates during his

Chartist years were W. J. Linton,

Thomas Cooper,

G. J. Holyoake,

Ernest Jones,

J. J. Bezer,

John Arnott, F. D. Maurice and Charles

Kingsley. Later, when he had established his literary reputation,

came Hepworth Dixon, Walter Savage

Landor and George Eliot, who is widely reported to have taken Massey as

her model for the character of Felix Holt in "The Radical," although

there is no hard evidence to support this. Somewhat later came

Robert Browning (who Massey met at the establishment of Lady Marion

Alford, his patron, at Ashridge in Hertfordshire ― see Massey's

letter in defence of

Browning) and the poetess, novelist and author of charming children's stories,

Jean Ingelow, to whom, following the death of

his first wife, Rosina, in 1866, it was rumoured that Massey proposed marriage

(another rumour of this period linked Jean Ingelow with Robert

Browning).

This period, 1869-70, saw the publication of A

Tale of Eternity and other poems, the last of Massey's

significant poetry; it also marked the end of Massey's long

association (and for him, a comparatively regular stipend) as a poetry

reviewer for the influential periodical, the Athenæum. The

cause of the break is unknown, but in a letter to another of the

journal's reviewers, Thomas Purnell, Massey hints at a 'falling out' . .

.

Curiously enough I had corresponded with the ‘Athm.’ people about

resuming my old seat on their Critical bench. But, after one

meeting and your communication, I shall drop the subject and not ask for

any Books. The whole affair is infinitely funny.

Thereafter Massey all but abandoned poetry and commenced

his long research into religious origins. His 'trilogy' ("The Book

of the Beginnings", "The Natural Genesis" and "Ancient Egypt: The Light

of the World"), published between 1881 and

1907, demonstrates clearly his complete change of thought regarding the

organised religions of the day and his firm alignment to the concept of

evolution; whilst he did not become an atheist, he might be classed as a deist

(i.e. "One who believes in the existence of a God or supreme being but

denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and

reason").

A misconception about Massey's religious

beliefs stems from his connection with the Most Ancient Order of Druids to

which he was elected Chosen Chief, an honorary position that he held from

1880 until 1906. The position might have involved some minor administrative duties,

but it required no formal membership. To Massey, at least, it was not a

religion and did not involve forms of initiation, ceremonial dress or

attendance at active meetings at megalithic sites; indeed, Massey did

not believe in such pagan ceremony and made his interest in the Druids

plain . . . .

"I cannot join in the new masquerade and

simulation of ancient mysteries manufactured in our time by Theosophists,

Hermeneutists, pseudo-Esoterics, and Occultists of various orders,

howsoever profound their pretensions. The very essence of all such

mysteries as are got up from the refuse leavings of the past is pretence,

imposition, and imposture. The only interest I take in the ancient

mysteries is in ascertaining how they originated, in verifying their

alleged phenomena, in knowing what they meant, on purpose to publish the

knowledge as soon and as widely as possible." (vide Massey's response to

the Blavatsky letter, Agnostic Journal, 1891).

Original editions of most of Massey's books are available on the antiquarian

book market

(but, in good condition, can

command high prices) and most of his work is also now available in modern reprints. Copies of all Massey's major published work are held by the

British Library, at

British & Irish university libraries, and in

the US Library of Congress. |

|

Day

after day her dainty hands

Make Life's soiled temples clean,

And there's a wake of glory where

Her spirit pure hath been.

At midnight, through that shadow-land,

Her living face doth gleam;

The dying kiss her shadow, and

The Dead smile in their dream.

.....on

Florence Nightingale,

from

War Waits

|

|

In

silence sat our Crimean Hero, he

Who told us how they fought at Inkerman:

His heart swam up in tears at thoughts of

Home.

The roar and rack of Battle over and gone;

No more surprises in the bloody trench,

Where midnight swarmed with visions horrible,

And earth was like a fiery coast of hell!

All that long aching wintriness of soul,

Warm-melted in the arms of Wedded Love,

That drew him from the bloody battle-press,

And claspt him safe in their serene heaven,

Where Past and Future crown him as they

kiss.

And with dumb eloquence his poor armstump

moved,

As it were dreaming of a dear embrace.

from...Craigcrook

Castle

|

|

Up-rouse

ye now, brave brother-band;

With honest heart, and working hand:

We are but few, toil-tried and true,

Yet hearts beat high to dare and do.

And who would not a champion be,

In Labour's social Chivalry?

from....The

Chivalry of Labour |

|

In addition to his books and journalism, Massey

sought a living from contributions to periodical magazines, among others

being Chambers' Magazine, Cassell's Magazine, All the Year Round, and Good Words—the

first issue of this once-popular periodical (in 1860) includes a poem on the

great Italian unifier Garibaldi, for which Massey received ten guineas. He

also contributed to

literary journals, including Hogg's Instructor, Fraser's

Magazine, the North

British Review, the Quarterly

Review and the

Athenæum.

Massey also lectured widely in the U.K., mainly,

in his earlier years, on literature, poetry and pre-Raphaelite art, his

fiery style proving popular and often attracting large audiences—Professor

Marvin Vincent, an American theologian, described him thus:

"He is a splendid lecturer. He went off like the eighty-one ton pounder.

I didn't agree with his opening remarks, but it was like a shell

bursting among us, and we had enough to do to look out during the rest

of the lecture". In later years Massey undertook lecturing tours to North America; the first, in 1873-74, included

California and Canada, the second in 1883-85 extended to Australia and New

Zealand, but his third tour of the U.S.A. came to a

premature close when he was called home to be with his dying daughter, Hesper, for whom he had a particular affection. By this time he was lecturing chiefly on the subjects that

absorbed his later life, spiritualism, mythology and the mystical interpretation

of the Scriptures; in 1887 Massey published a selection of his

lectures on these topics.

―――♦―――

Massey

was twice married. He had 7 daughters and 2 sons (neither of whom reached

maturity), including two surviving

daughters from his first marriage.

|

My Love in Heaven! love was not hid

By closing of a Coffin-lid!

Dear Love in Heaven! true love survives

All separation in our lives!

O Love in Heaven, from you I win

Sure help without, and hope within!

My Love in Heaven, for me she waits

Like Morning golden at her Gate

from....Open

Sight

|

Massey's first wife, Rosina Jane Knowles, was a noted

clairvoyant. She was born in Bolton

in Lancashire and was nineteen when they married in 1850.

Rosina was to influence Massey's life significantly,

particularly his interest in and commitment to spiritualism. Sadly, she

was to develop severe depression, possibly stemming from the loss of two

of her children, a condition that was aggravated by growing dependence

on alcohol. She died in 1866 at the age of thirty-four—her badly weathered white

tombstone,

her name barely discernable, lies

near the gate of the beautiful secluded parish church of Saint Peter and Saint

Paul at Little Gaddesden near Tring. |

|

Massey's second

wife, Eva Byrn, who he married in 1868, was the daughter of an artist

and 'Professor of Dancing'. A contemporary magazine article

described Eva as accomplished and beautiful while referring to Massey as

having . . .

"a young, fresh look; a finely-formed head, too large for the small,

spare body; a pleasant, winning face, and long, dark brown hair,

whiskers, and moustache".

|

|

Gerald Massey—probably

early 1860s.

Photograph is

possibly by John & Charles Watkins. |

Some years earlier (1854) the poet and critic Sydney Dobell

(1824-74) described Massey thus:

"The upper part of his face reminds me of Raphael's angels, and I

catch myself dwelling upon him with a kind of optical fondness, as one

looks upon a beautiful picture or a rare colour. And this in spite

of a blue satin waistcoat! and a gold-coloured tie! The second

morning I came upon him early, sans neckerchief or collar, nursing his

sickly baby, the grey wrapper in which he sat, being like the mist to

the morning as regards his wonderful complexion, and it would be

difficult to imagine more marvellous (masculine) beauty . . ."

Massey ca. 1854.

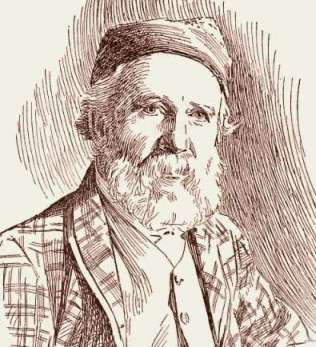

. . . . while after the passage of 30 years (1884), during his second

lecturing tour of the U.S.A.

an American journalist

found Massey to be:

"… at the grand climacteric of life; and is below the medium stature.

Grey whiskers, of English trim, half mask a face which wears a look of

intensity as he plows through the mystical domains of Egyptology and the

shadowlands of the ancient Orient. Brown hair, with occasional

streaks of grey, rolls forward in a billow on his crown, and ripples off

from the ears. He wears spectacles when he reads from manuscript."

A careworn Massey: a sketch from a

photograph taken

during his first American lecture tour, 1873.

While Eva does not appear to have had any discernable

impact on Massey's work, she undoubtedly brought stability to his

domestic life. Sadly, few of Massey's children by either

marriage survived into adulthood and with the death of his grand

daughter, Helena Viola, in 1988, his direct line came to an end.

Of his three brothers, Frederick left

numerous descendants and his line survives to this day. |

|

|

|

Ashridge: the residence of Lord Brownlow and his mother, Lady Marion

Alford.

|

|

Throughout his life Massey was beset with money problems, sometimes

having to borrow from friends. Although he eventually received a

civil list pension of £100 per annum—which must be judged by the

standards of the time—having to care for Rosina and a large family

exacerbated his already precarious existence as a writer and travelling

lecturer. Massey was fortunate, however, in securing the patronage

of Lady Marion Alford, mother of the wealthy owner of the Ashridge

Estate near Tring.

|

Of

such as he was, there be few on earth;

Of such as he is, there are few in Heaven:

And life is all the sweeter that he lived,

And all he loved more sacred for his sake:

And Death is all the brighter that he died,

And Heaven is all the happier that he's there.

From....In

Memoriam (to

Earl Brownlow) |

In 1865, Lord Brownlow settled Massey’s debts and

provided him and his family with an estate cottage in the village of Little

Gaddesden. However, Rosina's unbalanced state of mind—made worse by alcoholism—and her abilities as a clairvoyant aroused deep superstitions in the villagers,

who came to believe her to be a witch. The Brownlows again came to the

rescue, providing Massey with a large isolated farmhouse, Ward's

Hurst, where

he lived rent-free until 1877 when he moved to London. It was mainly during the period

at Wards Hurst that

Massey developed an interest in psychic phenomena that was to absorb his later

years, years in which he dropped from public view and in which there is little

record of his life.

Impecunious to the end, Massey died at his home in South Norwood

Hill, London, on the 29th of October 1907, and was laid to rest

in the family tomb in

London’s old Southgate Cemetery. Like many men of action and enterprise he was his own

educator, attending the best school that has ever existed since

men began their search for knowledge, the School of Experience,

wherein he became in his particular field—unravelling the mysteries of ancient Egyptian

mythology and elucidating its parallels with western religions—one

of its most distinguished graduates. . . ."It is a work which has

occupied me over thirty years, and I shall be well content if in

another century my ideas are acknowledged as correct".

|

|

Gone

are the last faint flashes,

Set is the sun of my years;

And over a few poor ashes,

I sit in my darkness and tears.

Massey,

from....Desolate |

|

|

|

――――♦――――

|

|

|

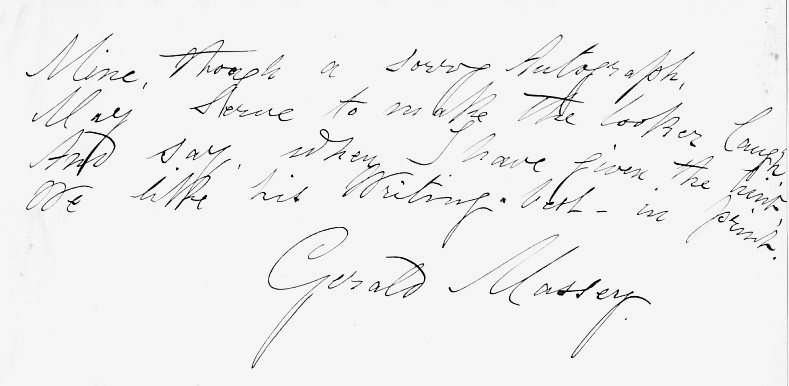

Mine, though a sorry Autograph,

May serve to make the looker laugh,

And say when I have given the hint,

We like his writing best—in print. |

|

――――♦――――

<>

|