|

PREFACE.

――――――――

THE present is a

revised edition of the life of George Stephenson and of his son

Robert Stephenson, to which is prefixed a history of the Railway and

the Locomotive in its earlier stages, uniform with the early history

of the Steam-engine given in vol. iv. of "Lives of the Engineers"

containing the memoirs of Boulton and Watt. A memoir of

Richard Trevithick has also been included in this introductory

portion of the book, which will probably be found more complete than

any notice which has yet appeared of that distinguished mechanical

engineer.

Since the appearance of this Life in its original form ten

years ago, the construction of railways has continued to make

extraordinary progress. The length of lines then open in

Europe was estimated at about 18,000 miles: it is now more than

50,000 miles. Although Great Britain, first in the field, had

then, after about twenty-five years' work, expended nearly 300

millions sterling in the construction of 8300 miles of double

railway, it has during the last ten years expended about 200

millions more in constructing 5600 additional miles.

But the construction of railways has proceeded with equal

rapidity on the Continent. France has now 9624 miles at work;

Germany (including Austria), 13,392 miles; Spain, 3161 miles;

Sweden, 1100 miles; Belgium, 1073 miles; Switzerland, 795 miles;

Holland, 617 miles; besides railways in other states. These

have, for the most part, been constructed and opened during the last

ten years, while a considerable length is still under construction.

Austria is actively engaged in carrying new lines across the plains

of Hungary to the frontier of Turkey, which Turkey is preparing to

meet by lines carried up the valley of the Lower Danube; and Russia,

with 2800 miles already at work, is occupied with extensive schemes

for connecting Petersburg and Moscow with her ports in the Black Sea

on the one hand, and with the frontier towns of her Asiatic empire

on the other.

Italy also is employing her new-born liberty in vigorously

extending railways throughout her dominions. The length of

Italian lines in operation in 1866 was 2752 miles, of which not less

than 680 were opened in that year. Already has a direct line

of communication been opened between Germany and Italy through the

Brenner Pass, by which it is now possible to make the entire journey

by railway (excepting only the short sea-passage across the English

Channel) from London to Brindisi on the south-eastern extremity of

the Italian peninsula; and, in the course of a few more years, a

still shorter route will be opened through France, when that most

formidable of all railway borings, the seven-mile tunnel under Mont

Cenis, has been completed.

During the last ten years, nearly the whole of the existing

Indian railways have been made. When Edmund Burke in 1783

arraigned the British government for their neglect of India in his

speech on Mr. Fox's Bill, he said, "England has built no bridges,

made no high roads, cut no navigations, dug out no reservoirs. . . .

. Were we to be driven out of India this day, nothing would remain

to tell that it had been possessed, during the inglorious period of

our dominion, by any thing better than the orang-outang or the

tiger." But that reproach no longer applies. Some of the

greatest bridges erected in modern times—such as those over the Sone

near Patna, and over the Jamna at Allahabad—have been erected in

connection with the Indian railways, of which there are already 3637

miles at work, and above 2000 more under construction. When

these lines have been completed, at an expenditure of about

£88,000,000 of British capital guaranteed by the British government,

India will be provided with a magnificent system of internal

communication, connecting the capitals of the three

Presidencies—uniting Bombay with Madras on the south, and with

Calcutta on the northeast—while a great main line, 2200 miles in

extent, passing through the north-western provinces, and connecting

Calcutta with Lucknow, Delhi, Lahore, Moultan, and Kurrachee, will

unite the mouths of the Hooghly in the Bay of Bengal with those of

the Indus in the Arabian Sea.

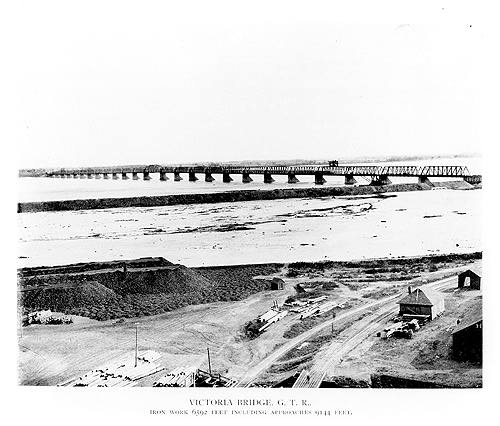

When the first edition of this work appeared in the beginning

of 1857, the Canadian system of railways was but in its infancy.

The Grand Trunk was only begun, and the Victoria Bridge—the greatest

of all railway structures—was not half erected. Now, that fine

colony has more than 2200 miles in active operation along the great

valley of the St. Lawrence, connecting Rivière du Loup at the mouth

of that river, and the harbour of Portland in the State of Maine,

via Montreal and Toronto, with Sarnia on Lake Huron, and with

Windsor, opposite Detroit, in the State of Michigan. The Australian

Colonies also have during the same time been actively engaged in

providing themselves with railways, many of which are at work, and

others are in course of formation. Even the Cape of Good Hope has

several lines open, and others making. France also has constructed

about 400 miles in Algeria, while the Pasha of Egypt is the

proprietor of 360 miles in operation across the Egyptian desert.

Victoria Bridge, Montreal, ca. 1898. See also

Chapter XX.

But in no country has railway construction been prosecuted

with greater vigour than in the United States. There the

railway furnishes not only the means of intercommunication between

already established settlements, as in the Old World, but it is

regarded as the pioneer of colonization, and as instrumental in

opening up new and fertile territories of vast extent in the

west—the food-grounds of future nations. Hence railway

construction in that country was scarcely interrupted even by the

great Civil War; at the commencement of which Mr. Seward publicly

expressed the opinion that "physical bonds, such as highways,

railroads, rivers, and canals, are vastly more powerful for holding

civil communities together than any mere covenants, though written

on parchment or engraved on iron."

The people of the United States were the first to follow the

example of England, after the practicability of steam locomotion had

been proved on the Stockton and Darlington and Liverpool and

Manchester Railways. The first sod of the Baltimore and Ohio

Railway was cut on the 4th of July, 1828, and the line was completed

and opened for traffic in the following year, when it was worked

partly by horse-power, and partly by a locomotive built at

Baltimore, which is still preserved in the Company's workshops.

In 1830 the Hudson and Mohawk Railway was begun, while other lines

were under construction in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New

Jersey; and in the course of ten years, 1843 miles were finished and

in operation. In ten more years, 8827 miles were at work; at

the end of 1864, not less than 35,000 miles, mostly single tracks;

while about 15,000 miles more were under construction. One of

the most extensive trunk-lines still unfinished is the Great Pacific

Railroad, connecting the lines in the valleys of the Mississippi and

the Missouri with the city of San Francisco on the shores of the

Pacific, by which, when completed, it will be possible to make the

journey from England to Hong Kong, via New York, in little

more than a month.

The results of the working of railways have been in many

respects different from those anticipated by their projectors.

One of the most unexpected has been the growth of an immense

passenger-traffic. The Stockton and Darlington line was

projected as a coal line only, and the Liverpool and Manchester as a

merchandise line. Passengers were not taken into account as a

source of revenue; for, at the time of their projection, it was not

believed that people would trust themselves to be drawn upon a

railway by an "explosive machine," as the locomotive was described

to be. Indeed, a writer of eminence declared that he would as

soon think of being fired off on a ricochet rocket as travel on a

railway at twice the speed of the old stage-coaches. So great

was the alarm which existed as to the locomotive, that the Liverpool

and Manchester Committee pledged themselves in their second

prospectus, issued in 1825, "not to require any clause empowering

its use;" and as late as 1829, the Newcastle and Carlisle Act was

conceded on the express condition that it should not be worked by

locomotives, but by horses only.

Nevertheless, the Liverpool and Manchester Company obtained

powers to make and work their railway without any such restriction;

and when the line was made and opened, a locomotive passenger-train

was ordered to be run upon it by way of experiment. Greatly to

the surprise of the directors, more passengers presented themselves

as travellers by the train than could conveniently be carried.

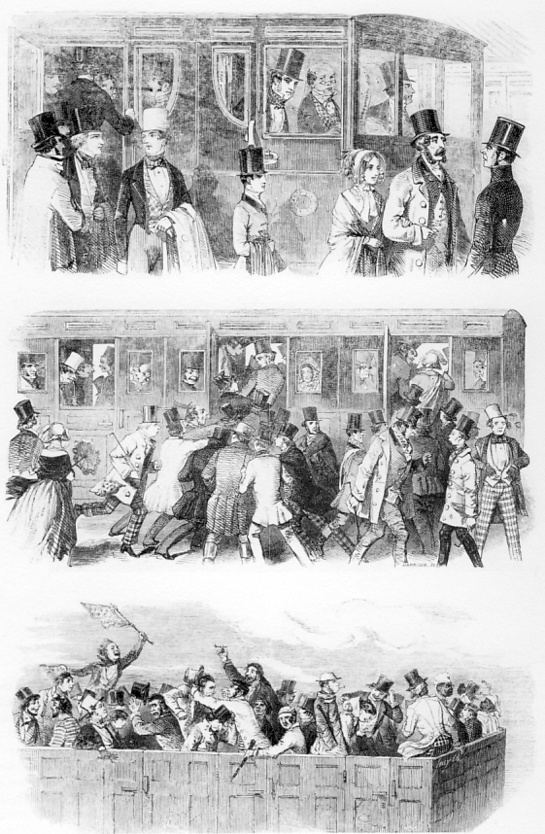

Inaugural journey, Liverpool and Manchester Railway,

15 Sept. 1830.

The first arrangements as to passenger-traffic were of a very

primitive character, being mainly copied from the old stage-coach

system. The passengers were "booked" at the railway office,

and their names were entered

in a way-bill which was given to the guard when the train started.

Though the usual stage-coach bugleman could not conveniently

accompany the passengers, the trains were at first played out of the

terminal stations by a lively tune performed by a trumpeter at the

end of the platform, and this continued to be done at the Manchester

Station until a comparatively recent date.

But the number of passengers carried by the Liverpool and

Manchester line was so unexpectedly great, that it was very soon

found necessary to remodel the entire system. Tickets were

introduced, by which a great saving of time was effected. More

roomy and commodious carriages were provided, the original

first-class compartments being seated for four passengers only.

Everything was found to have been in the first instance made too

light and too slight. The prize "Rocket," which weighed only

4½ tons when loaded with its coke and water, was found quite

unsuited for drawing the increasingly heavy loads of passengers.

There was also this essential difference between the old stage-coach

and the new railway train, that, whereas the former was "full" with

six inside and ten outside, the latter must be able to accommodate

whatever number of passengers came to be carried. Hence

heavier and more powerful engines, and larger and more substantial

carriages, were from time to time added to the carrying stock of the

railway.

The Rocket, built by Robert Stephenson and Company,

1829.

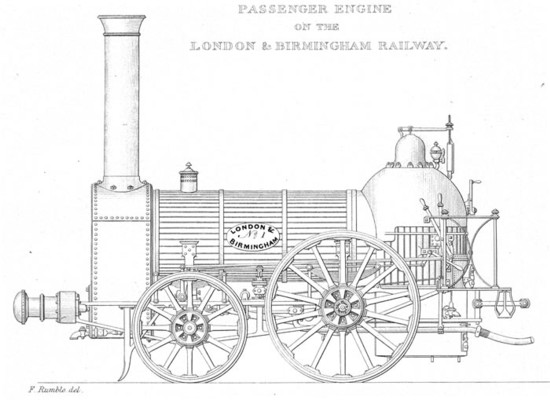

The speed of the trains was also increased. The first

locomotives used in hauling coal-trains ran at from four to six

miles an hour. On the Stockton and Darlington line the speed

was increased to about ten miles an hour; and on the Liverpool and

Manchester line the first passenger-trains were run at the average

speed of seventeen miles an hour, which at that time was considered

very fast. But this was not enough. When the London and

Birmingham line was opened, the mail-trains were run at twenty-three

miles an hour; and gradually the speed went up, until now the fast

trains are run at from fifty to sixty miles an hour—the pistons in

the cylinders, at sixty miles, travelling at the inconceivable

rapidity of 800 feet per minute!

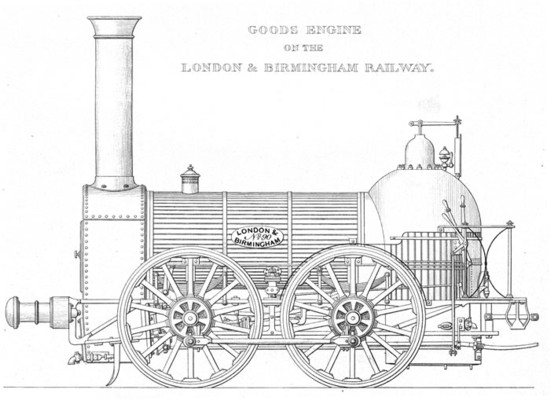

Bury-type freight locomotive, ca. 1840.

To bear the load of heavy engines run at high speeds, a much

stronger and heavier road was found necessary; and shortly after the

opening of the Liverpool and Manchester line, it was entirely

re-laid with stronger materials. Now that express

passenger-engines are from thirty to thirty-five tons each, the

weight of the rails has been increased from 35 lbs. to 75 lbs. or 86

lbs. to the yard. Stone blocks have given place to wooden

sleepers; rails with loose ends resting on the chairs, to rails with

their ends firmly "fished" together; and in many places, where the

traffic is unusually heavy, iron rails have been replaced by those

of steel.

Bury-type passenger locomotive, ca. 1840.

And now see the enormous magnitude to which railway

passenger-traffic has grown. In the year 1866, 274,293,668

passengers were carried by day tickets in Great Britain alone. But

this was not all; for in that year 110,227 periodical tickets were

issued by the different railways; and assuming half of them to be

annual, one fourth half-yearly, and the remainder quarterly tickets,

and that their holders made only five journeys each way weekly, this

would give an additional number of 39,405,600 journeys, or a total

of 313,699,268 passengers carried in Great Britain in one year.

It is difficult to grasp the idea of the enormous number of

persons represented by these figures. The mind is merely

bewildered by them, and can form no adequate notion of their

magnitude. To reckon them singly would occupy twenty years,

counting at the rate of one a second for twelve hours every day.

Or take another illustration. Supposing every man, woman, and

child in Great Britain to make ten journeys by rail yearly, the

number would fall short of the passengers carried in 1866.

Mr. Porter, in his "Progress of the Nation," estimated that

thirty millions of passengers, or about eighty-two thousand a day,

travelled by coaches in Great Britain in 1834, an average distance

of twelve miles each, at an average cost of 5s. a passenger,

or at the rate of 5d. a mile; whereas above 313 millions are

now carried by railway an average distance of 8½ miles each, at an

average cost of 1s. l½d. per passenger, or about three

half-pence per mile, in considerably less than half the time.

But, besides the above number of passengers, one hundred and

twenty-four million tons of minerals and merchandise were carried by

railway in the United Kingdom in 1866, and fifteen millions of

cattle, besides mails, parcels, and other traffic. The

distance run by passenger and goods trains in the year was

142,807,853 miles, to accomplish which it is estimated that four

miles of railway on an average must be covered by running trains

during every second all the year round.

To perform this service, there were, in 1866, 8125

locomotives at work in the United Kingdom, consuming about three

million tons of coal and coke, and flashing into the air every

minute some thirty tons of water in the form of steam in a high

state of elasticity. There were also 19,228

passenger-carriages, 7276 vans and breaks attached to

passenger-trains, and 242,947 trucks, wagons, and other vehicles

appropriated to merchandise. Buckled together, buffer to

buffer, the locomotives and tenders would extend for a length of

about 54 miles, or more than the distance from London to Brighton;

while the carrying vehicles, joined together, would form two trains

occupying a double line of railway extending from London to beyond

Inverness.

First, second and third class passengers setting off

for Epsom races, 1847.

A notable feature in the growth of railway traffic of late

years has been the increase in the number of third-class passengers,

compared with first and second class. Sixteen years since, the

third-class passengers constituted only about one third; ten years

later they were about one half; whereas now they form nearly two

thirds of the whole number carried. Thus George Stephenson's

prediction "that the time would come when it would be cheaper for a

working man to make a journey by railway than to walk on foot" is

already realized.

The degree of safety with which this great traffic has been

conducted is not the least remarkable of its features. Of

course, so long as railways are worked by men, they will be liable

to the imperfections belonging to all things human. Though

their machinery may be perfect, and their organization as complete

as skill and forethought can make it, workmen will at times be

forgetful and listless, and a moment's carelessness may lead to the

most disastrous results. Yet, taking all circumstances into

account, the wonder is that travelling by railway at high speeds

should have been rendered comparatively so safe.

To be struck by lightning is one of the rarest of all causes

of death, yet more persons were killed by lightning in Great

Britain, in 1866, than were killed on railways from causes beyond

their own control; the number in the former case having been

nineteen, and in the latter fifteen, or one in every twenty millions

of passengers carried. Most persons would consider the

probability of their dying by hanging to be extremely remote; yet,

according to the Registrar General's returns for 1867, it is thirty

times greater than that of being killed by railway accident.

Taking the number of persons who travelled in Great Britain in 1866

at 313,699,268, of whom fifteen were accidentally killed, it would

appear that, even supposing a person to have a permanent existence,

and to make a journey by railway daily, the probability of his being

killed in an accident would occur on an average once in above 50,000

years.

The remarkable safety with which railway traffic is on the

whole conducted, is due to constant watchfulness and highly-applied

skill. The men who work the railways are for the most part the

picked men of the country, and every railway station may be regarded

as a practical school of industry, attention, and punctuality.

Where railways fail in these respects, it will usually be found that

it is because the men are personally defective, or because better

men are not to be had. It must also be added that the onerous

and responsible duties which railway workmen are called upon to

perform require a degree of consideration on the part of the public

which is not very often extended to them.

Few are aware of the complicated means and agencies that are

in constant operation on railways day and night to insure the safety

of the passengers to their journeys' end. The road is under a

system of continuous inspection, under gangs of men—about twelve to

every five miles, under a foreman or "ganger"—whose duty it is to

see that the rails and chairs are sound, all their fastenings

complete, and the line clear of obstructions.

Then, at all the junctions, sidings, and crossings, pointsmen

are stationed, with definite instructions as to the duties to be

performed by them. At these places signals are provided,

worked from the station platforms, or from special signal-boxes, for

the purpose of protecting the stopping or passing trains. When

the first railways were opened the signals were of a very simple

kind. The station-men gave them with their arms stretched out

in different positions; then flags of different colours were used;

next fixed signals, with arms or discs, or of rectangular or

triangular shape. These were followed by a complete system of

semaphore signals, near and distant, protecting all junctions,

sidings, and crossings.

When government inspectors were first appointed by the Board

of Trade to examine and report upon the working of railways, they

were alarmed by the number of trains following each other at some

stations in what then seemed to be a very rapid succession. A

passage from a Report written in 1840 by Sir Frederick Smith, as to

the traffic at "Taylor's Junction," on the York and North Midland

Railway, contrasts curiously with the railway life and activity of

the present day: "Here," wrote the alarmed inspector, "the passenger

trains from York, as well as Leeds and Selby, meet four times a day.

No less than 23 passenger-trains stop at or pass this station in the

24 hours—an amount of traffic requiring not only the most perfect

arrangements on the part of the management, but the utmost vigilance

and energy in the servants of the Company employed at this place."

Contrast this with the state of things now. On the

Metropolitan Line, 667 trains pass a given point in one direction or

the other during the eighteen hours of the working day, or an

average of 36 trains an hour. At the Cannon-street Station of

the South-eastern Railway, 527 trains pass in and out daily, many of

them crossing each others' tracks under the protection of the

station signals. Forty-five trains run in and out between 9

and 10 A.M., and an equal number between 4 and 5 P.M. Again,

at the Clapham Junction, near London, about 700 trains pass or stop

daily; and though to the casual observer the succession of trains

coming and going, running and stopping, coupling and shunting,

appears a scene of inextricable confusion and danger, the whole is

clearly intelligible to the signal-men in their boxes, who work the

trains in and out with extraordinary precision and regularity.

The inside of a signal-box reminds one of a piano-forte on a

large scale, the lever-handles corresponding with the keys of the

instrument; and, to an uninstructed person, to work the one would be

as difficult as to play a tune on the other. The signal-box

outside Cannon-street Station contains 67 lever-handles, by means of

which the signal-men are enabled at the same moment to communicate

with the drivers of all the engines on the line within an area of

800 yards. They direct by signs, which are quite as

intelligible as words, the drivers of the trains starting from

inside the station, as well as those of the trains arriving from

outside. By pulling a lever-handle, a distant signal, perhaps

out of sight, is set some hundred yards off, which the approaching

driver—reading it quickly as he comes along—at once interprets, and

stops or advances, as the signal may direct.

The precision and accuracy of the signal-machinery employed

at important stations and junctions have of late years been much

improved by an ingenious contrivance, by means of which the setting

of the signal prepares the road for the coming train. When the

signal is set at "Danger," the points are at the same time worked,

and the road is "locked" against it; and when at "Safety," the road

is open—the signal and the points exactly corresponding.

The Electric Telegraph has also been found a valuable

auxiliary in insuring the safe working of large railway traffics.

Though the locomotive may run at sixty miles an hour, electricity,

when at its fastest, travels at the rate of 288,000 miles a second,

and is therefore always able to herald the coming train. The

electric telegraph may, indeed, be regarded as the nervous system of

the railway. By its means the whole line is kept throbbing

with intelligence. The method of working electric signals

varies on different lines; but the usual practice is to divide a

line into so many lengths, each protected by its signal-stations,

the fundamental law of telegraph working being that two engines are

not to be allowed to run on the same line between two

signal-stations at the same time. When a train passes one of

such stations, it is immediately signalled on—usually by electric

signal-bells—to the station in advance, and that interval of railway

is "blocked" until the signal has been received from the station in

advance that the train has passed it. Thus an interval of

space is always secured between trains following each other,

which are thereby alike protected before and behind. And thus,

when a train starts on a journey of it may be hundreds of miles, it

is signalled on from station to station, and "lives along the line,"

until at length it reaches its destination, and the last signal of

"train in" is given. By this means an immense number of trains

can be worked with regularity and safety. On the South-eastern

Railway, where the system has been brought to a state of high

efficiency, it is no unusual thing during Easter week to send

570,000 passengers through the London Bridge Station alone; and on

some days as many as 1200 trains a day.

While such are the expedients adopted to insure safety,

others equally ingenious are adopted to insure speed. In the

case of express and mail trains, the frequent stopping of the

engines to take in a fresh supply of water occasions a considerable

loss of time on a long journey, each stoppage for this purpose

occupying from ten to fifteen minutes. To avoid such stoppages

larger tenders have been provided, capable of carrying as much as

2000 gallons of water each. But as a considerable time is

occupied in filling these, a plan has been contrived by Mr.

Ramsbottom, the locomotive engineer of the London and North-western

Railway, by which the engines are made to feed themselves

while running at full speed! The plan is as follows: An open

trough, about 440 feet long, is laid longitudinally between the

rails. Into this trough, which is filled with water, a

dip-pipe, or scoop attached to the bottom of the tender of the

running train, is lowered, and, at a speed of 50 miles an hour, as

much as 1070 gallons of water are scooped up in the course of a few

minutes. The first of such troughs was laid down between

Chester and Holyhead, to enable the Express Mail to run the distance

of 84¾ miles in two hours and five minutes without stopping; and

similar troughs have since been laid down at Bushey, near London; at

Castlethorpe, near Wolverton; and at Parkside, near Liverpool.

At these four troughs about 130,000 gallons of water are scooped up

daily.

Wherever railways have been made, new towns have sprung up,

and old towns and cities been quickened into new life. When

the first English lines were projected, great were the prophecies of

disaster to the inhabitants of the districts through which they were

proposed to be forced. Such fears have long since been

dispelled in this country. The same prejudices existed in

France. When the railway from Paris to Marseilles was

projected to pass through Lyons, a local prophet predicted that if

the line were made the city would be ruined—"ille traversée,

ville perdue;" while a local priest denounced the locomotive and

the electric telegraph as heralding the reign of Antichrist.

But such nonsense is no longer uttered. Now it is the city

without the railway that is regarded as the "city lost;" for it is

in a measure shut out from the rest of the world, and left outside

the pale of civilization.

Perhaps the most striking of all the illustrations that could

be offered of the extent to which railways facilitate the

locomotion, the industry, and the subsistence of the population of

large towns and cities, is afforded by the working of the railway

system in connection with the capital of Great Britain.

The extension of railways to London has been of comparatively

recent date, the whole of the lines connecting it with the provinces

and terminating at its outskirts having been opened during the last

thirty years, while the lines inside London have for the most part

been opened within the last ten years.

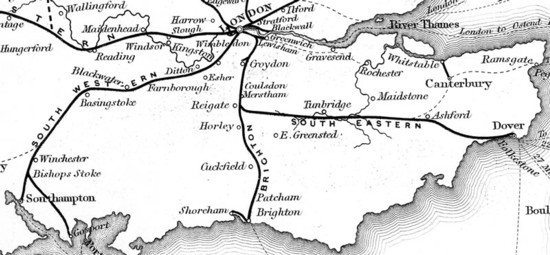

Map of railways running into London from the south

and west,

ca. 1840.

(Greenwich at top centre)

The first London line was the Greenwich Railway, part of

which was opened for traffic to Deptford in February, 1836.

The working of this railway was first exhibited as a show, and the

usual attractions were employed to make it "draw." A band of

musicians in the garb of the Beef-eaters was stationed at the London

end, and another band at Deptford. For cheapness' sake, the

Deptford band was shortly superseded by a large barrel-organ, which

played in the passengers; but when the traffic became established,

the barrel-organ, as well as the Beefeater band at the London end,

were both discontinued. The whole length of the line was lit

up at night by a row of lamps on either side like a street, as if to

enable the locomotives or the passengers to see their way in the

dark; but these lamps also were eventually discontinued as

unnecessary.

As a show, the Greenwich Railway proved tolerably successful.

During the first eleven months it carried 456,750 passengers, or an

average of about 1300 a day. But the railway having been found

more convenient to the public than either the river boats or the

omnibuses, the number of passengers rapidly increased. When

the Croydon, Brighton, and South-eastern Railways began to pour

their streams of traffic over the Greenwich Viaduct, its

accommodation was found much too limited, and it was widened from

time to time, until now nine lines of railway are laid side by side,

over which more than twenty millions of passengers are carried

yearly, or an average of about 60,000 a day all the year round.

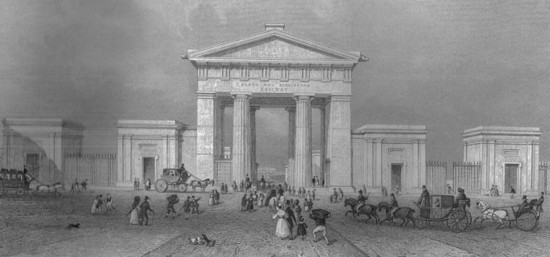

The entrance to London Euston station, 1838.

Philip Hardwick's splendid 'Euston Arch'

was demolished amidst much public protest in 1962.

Since the partial opening of the Greenwich Railway in 1836, a

large extent of railways has been constructed in and about the

metropolis, and convenient stations have been established almost in

the heart of the city. Sixteen of these stations are within a circle

of half a mile radius from the Mansion House, and above three

hundred stations are in actual use or in course of construction

within about five miles of Charing Cross. The most important lines

recently opened for the accommodation of the London local traffic

have been the London, Chatham and Dover Metropolitan Extensions

(1861), the Metropolitan (1863), the North London Extension to

Liverpool Street (1865), the Charing Cross and Cannon-street

Extensions of the South-eastern Railway (1864-6), and the South

London Extension of the Brighton Railway (1866). Of these railways,

the London, Chatham and Dover carried 5,228,418 passengers in 1867;

the Metropolitan, 23,405,282; the North London, 17,585,502; the

South-eastern, 17,473,934; and the Brighton, 12,686,417. The total

number carried into and out of London, as well as from station to

station in London, in the same year, was 104 millions of passengers.

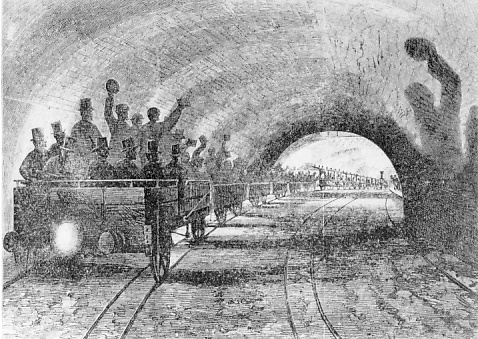

The Metropolitan Railway. Trial run, 1862.

To accommodate this vast traffic, not fever than 3600 local

trains are run in and out daily, besides 340 trains which depart to

and arrive from distant places, north, south, east, and west.

In the morning hours, between 8.30 and 10.30, when business men are

proceeding inward to their offices and counting-houses, and in the

afternoon between four and six, when they are returning outward to

their homes, as many as two thousand stoppages are made in the hour,

within the metropolitan district, for the purpose of taking up and

setting down passengers, while about two miles of railway are

covered by the running trains.

One of the remarkable effects of railways has been to extend

the residential area of all large towns and cities. This is

especially notable in the case of London. Before the

introduction of railways, the residential area of the metropolis was

limited by the time occupied by business men in making the journey

outward and inward daily; and it was for the most part bounded by

Bow on the east, by Hampstead and Highgate on the north, by

Paddington and Kensington on the west, and by Clapham and Brixton on

the south. But now that stations have been established near

the centre of the city, and places so distant as Waltham, Barnet,

Watford, Hanwell, Richmond, Epsom, Croydon, Reigate, and Erith can

be more quickly reached by rail than the old suburban quarters were

by omnibus, the metropolis has become extended in all directions

along its railway lines, and the population of London, instead of

living in the city or its immediate vicinity as formerly, have come

to occupy a residential area of not less than six hundred square

miles!

Pursuit of Pleasure under Difficulties: Getting home

from the Crystal Palace on a Fête day.

The number of new towns which have consequently sprung into

existence near London within the last twenty years has been very

great; towns numbering from ten to twenty thousand inhabitants,

which before were but villages, if indeed, they existed. This

has especially been the case along the lines south of the Thames,

principally in consequence of the termini of those lines being more

conveniently situated for city men of business. Hence the

rapid growth of the suburban towns up and down the river, from

Richmond and Staines on the west, to Erith and Gravesend on the

east, and the hives of population which have settled on the high

grounds south of the Thames, in the neighbourhood of Norwood and the

Crystal Palace, rapidly spreading over the Surrey Downs, from

Wimbledon to Guildford, and from Bromley to Croydon, Epsom, and

Dorking. And now that the towns on the south and southeast

coast can be reached by city men in little more time than it takes

to travel to Clapham or Bayswater by omnibus, such places have

become, as it were, parts of the great metropolis, and Brighton and

Hastings are but marine suburbs of London.

The improved state of the communications of the city with the

country has had a marked effect upon its population. While the

action of the railways has been to add largely to the number of

persons living in London, it has also been accompanied by their

dispersion over a much larger area. Thus the population of the

central parts of London is constantly decreasing, whereas that of

the suburban districts is as constantly increasing. The

population of the city fell off more than 10,000 between 1851 and

1861; and during the same period, that of Holborn, the Strand, St

Martin-in-the-Fields, St James's, Westminster, East and West London,

showed a considerable decrease. But, as regards the whole mass

of the metropolitan population, the increase has been enormous,

especially since the introduction of railways. Thus, starting

from 1801, when the population of London was 958,868, we find it

increasing in each decennial period at the rate of between two and

three hundred thousand, until the year 1841, when it amounted to

1,948,369. Railways had by that time reached London, after

which its population increased at nearly double the former ratio.

In the ten years ending 1851, the increase was 413,867; and in the

ten years ending 1861, 441,768; until now, to quote the words of the

Registrar General in his last annual Report, "the population within

the registration limits is by estimate 2,993,513; but beyond this

central mass there is a ring of life growing rapidly, and extending

along railway lines over a circle of fifteen miles from Charing

Cross. The population within that circle, patrolled by the

metropolitan police, is about 3,463,771!"

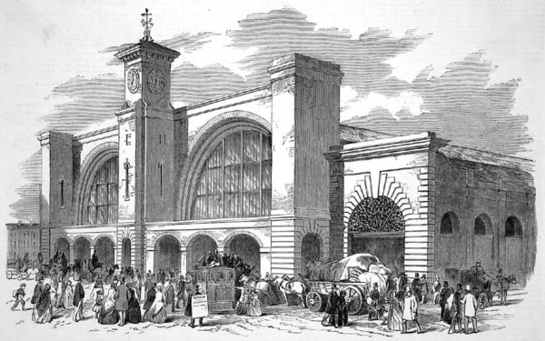

King's Cross station, London, opened 1852.

The aggregation of so vast a number of persons within so

comparatively limited an area—the immense quantity of food required

for their daily sustenance, as well as of fuel, clothing, and other

necessaries—would be attended with no small inconvenience and danger

but for the facilities again provided by the railways. The

provisioning of a garrison of even four thousand men is considered a

formidable affair; how much more so the provisioning of nearly four

millions of people!

The whole mystery is explained by the admirable organization

of the railway service, and the regularity and dispatch with which

it is conducted. We are enabled by the courtesy of the general

managers of the London railways to bring together the following

brief summary of facts relating to the food supply of London, which

will probably be regarded by most readers as of a very remarkable

character.

Generally speaking, the railways to the south of the Thames

contribute comparatively little toward the feeding of London.

They are, for the most part, passenger and residential lines,

traversing a limited and not very fertile district bounded by the

sea-coast, and, excepting in fruit and vegetables, milk and hops,

they probably carry more food from London than they bring to it.

The principal supplies of grain, flour, potatoes, and fish are

brought by railway from the eastern counties of England and

Scotland; and of cattle and sheep, beef and mutton, from the grazing

counties of the west and northwest of Britain, as far as from the

Highlands of Scotland, which, through the instrumentality of

railways, have become part of the great grazing-grounds of the

metropolis.

Take first "the staff of life"—bread and its constituents.

Of wheat, not less than 222,080 quarters were brought into London by

railway in 1867, besides what was brought by sea; of oats, 151,767

quarters; of barley, 70,282 quarters; of beans and peas, 51,448

quarters. Of the wheat and barley, by far the largest

proportion was brought by the Great Eastern Railway, which delivered

in London last year 155,000 quarters of wheat and 45,500 quarters of

barley, besides 600,429 quarters more in the form of malt. The

largest quantity of oats was brought by the Great Northern Railway,

principally from the north of England and the east of Scotland—the

quantity delivered by that company in 1867 having been 97,500

quarters, besides 24,664 quarters of wheat, 5560 quarters of barley,

and 103,917 quarters of malt. Again, of 1,250,566 sacks of

flour and meal delivered in London last year, the Great Eastern

brought 654,000 sacks, the Great Northern 232,022 sacks, and the

Great Western 136,312 sacks; the principal contribution of the

London and North-western Railway toward the London bread-stores

being 100,760 boxes of American flour, besides 24,300 sacks of

English. The total quantity of malt delivered at the London

railway stations in 1867 was thirteen hundred thousand sacks.

Next, as to flesh meat. Last year not fewer than

172,300 head of cattle were brought into London by railway, though

this was considerably less than the number carried before the cattle

plague, the Great Eastern Railway alone having carried 44,672 less

than in 1864. But this loss has since been more than made up

by the increased quantities of fresh beef, mutton, and other kinds

of meat imported in lieu of the live animals. The principal

supplies of cattle are brought, as we have said, by the western,

northern, and eastern lines: by the Great Western from the western

counties and Ireland; by the London and North-western, the Midland,

and the Great Northern, from the northern counties and from

Scotland; and by the Great Eastern from the eastern counties, and

from the ports of Harwich and Lowestoft

Last year also, 1,147,609 sheep were brought to London by

railway, of which the Great Eastern delivered not less than 265,371

head. The London and North-western and Great Northern between

them brought 390,000 head from the northern English counties, with a

large proportion from the Scotch Highlands; while the Great Western

brought up 130,000 head from the Welsh mountains, and from the rich

grazing districts of Wilts, Gloucester, Somerset, and Devon.

Another important freight of the London and North-western Railway

consists of pigs, of which they delivered 54,700 in London last

year, principally Irish; while the Great Eastern brought up 27,500

of the same animal, partly foreign.

While the cattle plague has had the effect of greatly

reducing the number of live-stock brought into London yearly, it has

given a considerable impetus to the Fresh Meat traffic. Thus,

in addition to the above large numbers of cattle and sheep delivered

in London last year, the railways brought 76,175 tons of meat,

which—taking the meat of an average beast at 800 lbs., and of an

average sheep at 64 lbs.—would be equivalent to about 112,000 more

cattle, and 1,267,500 more sheep. The Great Northern brought

the largest quantity; next, the London and North-western—these two

companies having brought up between them, from distances as remote

as Aberdeen and Inverness, about 42,000 tons of fresh meat in 1867,

at an average freight of about ½d. a lb.

Again, as regards Fish, of which six tenths of the whole

quantity consumed in London is now brought by rail. The Great

Eastern and the Great Northern are by far the largest importers of

this article, and justify their claim to be regarded as the great

food lines of London. Of the 61,358 tons of fish brought by

railway in 1867, not less than 24,600 tons were delivered by the

former, and 22,000 tons, brought from much longer distance, by the

latter company. The London and North-western brought about

6000 tons last year, the principal part of which was salmon from

Scotland and Ireland. The Great Western also brought about

4000 tons, partly salmon, but the greater part mackerel from the

southwest coast. During the mackerel season, as much as a

hundred tons at a time are brought into the Paddington Station by

express fish-train from Cornwall.

The Great Eastern and Great Northern Companies are also the

principal carriers of turkeys, geese, fowls, and game, the quantity

delivered in London last year by the former company having been 5042

tons. In Christmas week no fewer than 30,000 turkeys and geese

were delivered at the Bishopsgate Station, besides about 300 tons of

poultry, 10,000 barrels of beer, and immense quantities of fish,

oysters, and other kinds of food. As much as 1600 tons of

poultry and game were brought last year by the South-western

Railway; 600 tons by the Great Northern Railway; and 130 tons of

turkeys, geese, and fowls by the London, Chatham and Dover line,

principally from France.

|

|

Sketch of

the Midland

Counties Railway

a constituent of what became the

Midland Railway. |

Of miscellaneous articles, the Great Northern and Midland each

brought about 3000 tons of cheese, the South-western 2600 tons, and

the London and North-western 10,034 cheeses in number; while the

South-western and Brighton lines brought a splendid contribution to

the London breakfast-table in the shape of 11,259 tons of

French eggs; these two companies delivering between them an average

of more than three millions of eggs a week all the year round!

The same companies last year delivered in London 14,819 tons of

butter, the most part the produce of the farms of Normandy, the

greater cleanness and neatness with which the Normandy butter is

prepared for market rendering it a favourite both with dealers and

consumers of late years compared with Irish butter. The

London, Chatham and Dover Company also brought from Calais 96 tons

of eggs.

Next, as to the potatoes, vegetables, and fruit brought by

rail. Forty years since, the inhabitants of London relied for

their supply of vegetables on the garden-grounds in the immediate

neighbourhood of the metropolis, and the consequence was that they

were both very dear and limited in quantity. But railways,

while they have extended the grazing-grounds of London as far as the

Highlands, have at the same time extended the garden-grounds of

London into all the adjoining counties—into East Kent, Essex,

Suffolk, and Norfolk, the vale of Gloucester, and even as far as

Penzance in Cornwall. The London, Chatham and Dover, one of

the youngest of our main lines, brought up from East Kent last year

5279 tons of potatoes, 1046 tons of vegetables, and 5386 tons of

fruit, besides 542 tons of vegetables from France. The

South-eastern brought 25,163 tons of the same produce. The

Great Eastern, brought from the eastern counties 21,315 tons of

potatoes, and 3596 tons of vegetables and fruit; while the Great

Northern brought no less than 78,505 tons of potatoes—a large part

of them from the east of Scotland—and 3768 tons of vegetables and

fruit. About 6000 tons of early potatoes were last year

brought from Cornwall, with about 5000 tons of broccoli, and the

quantities are steadily increasing. "Truly London hath a large

belly," said old Fuller two hundred years since. But how much

more capacious is it now!

One of the most striking illustrations of the utility of

railways in contributing to the supply of wholesome articles of food

to the population of large cities is to be found in the rapid growth

of the traffic in Milk. Readers of newspapers may remember the

descriptions published some years since of the horrid dens in which

London cows are penned, and of the odious compound sold by the name

of milk, of which the least deleterious ingredient in it was

supplied by the "cow with the iron tail." That state of

affairs is now completely changed. What with the greatly

improved state of the London dairies and the better quality of the

milk supplied by them, together with the large quantities brought by

railway from a range of a hundred miles and more all round London,

even the poorest classes in the metropolis are now enabled to obtain

as wholesome a supply of the article as the inhabitants of most

country towns.

The milk traffic has in some cases been rapid, almost sudden,

in its growth. Though the Great Western is at present the

greatest of the milk lines, it brought very little into London prior

to the year 1865. In the month of August in that year it

brought 23,474 gallons, and in the month of October following the

quantity had increased to 103,214 gallons. Last year the total

quantity delivered in London by this single railway was 1,514,836

gallons, or an average of 30,000 gallons a week. The largest

proportion of this milk was brought from beyond Swindon in

Wiltshire, about 100 miles from London; but considerable quantities

were also brought from the vale of Gloucester and from Somerset.

The London and South-western also is a great milk-carrying line,

having brought as much as 1,480,272 gallons to London last year, or

an average of 28,000 gallons a week. The Great Eastern brought

nearly the same quantity, 1,322,429 gallons, or an average of about

25,400 gallons a week. The London and North-western ranks

next, having brought 643,432 gallons in 1867; then the Great

Northern, 455,916 gallons; the South-eastern, 435,668 gallons; and

the Brighton, 419,254 gallons. The total quantity of milk

delivered in London by railway last year was 6,309,446 gallons, or

above 120,000 gallons a week. Yet this traffic, large though

it may appear, is as yet but in its infancy, and in the course of a

few more years it will be found very largely increased, according as

facilities are provided for its accommodation and transit.

These great streams of food, which we have thus so summarily

described, flow into London so continuously and uninterruptedly,

that comparatively few persons are aware of the magnitude and

importance of the process thus daily going forward. Though

gathered from an immense extent of country— embracing England,

Scotland, Wales, and Ireland—the influx is so unintermitted that it

is relied upon with as much certainty as if it only came from the

counties immediately adjoining London. The express meat-train

from Aberdeen arrives in town as punctually as the Clapham omnibus,

and the express milk-train from Aylesbury is as regular in its

delivery as the penny post. Indeed, London now depends so much

upon railways for its subsistence, that it may be said to be fed by

them from day to day, having never more than a few days' food in

stock. And the supply is so regular and continuous, that the

possibility of its being interrupted never for a moment occurs to

any one. Yet, in these days of strikes among workmen, such a

contingency is quite within the limits of possibility. Another

contingency, arising in a state of war, is probably still more

remote. But, were it possible for a war to occur between

England and a combination of foreign powers possessed of stronger

iron-clads than ours, and that they were able to ram our ships back

into port and land an enemy of overpowering force on the Essex

coast, it would be sufficient for them to occupy or cut the railways

leading from the north, to starve London into submission in less

than a fortnight.

Besides supplying London with food, railways have also been

instrumental in insuring the more regular and economical supply of

fuel—a matter of almost as vital importance to the population in a

climate such as that of England. So long as the market was

supplied with coal brought by sea in sailing ships, fuel in winter

often rose to a famine price, especially during long-continued

easterly winds. But, now that railways are in full work, the

price is almost as steady in winter as in summer, and the supply is

more regular at all seasons. The following statement of the

coals brought into London by sea and by railway, at decennial

periods since 1827, as supplied by Mr. J. R Scott, Registrar of the

Coal Exchange, shows the effect of railways in increasing the supply

of fuel, at the same time that they have lowered the price to the

consumer:

|

Years |

Sea-born Coal. |

Coals brought by Railway. |

Price per Ton. |

| |

Tons. |

Tons. |

s. d. |

|

1827 |

1,882,321 |

nil |

28. 6 |

|

1847 |

3,280,420 |

19,336 |

20. 10 |

|

1857 |

3,133,459 |

1,206,775 |

18. 8 |

|

1867 |

3,016,416 |

3,295,652 |

20. 8 |

Thus the price of coal has been reduced 7s.10d.a

ton since 1827, while the quantity delivered has been enormously

increased, the total saving on the quantity consumed in the

metropolis in 1867, compared with 1827, being equal to £2,388,000.

But the carriage of food and fuel to London forms but a small

part of the merchandise traffic carried by railway. Above

600,000 tons of goods of various kinds yearly pass through one

station only, that of the London and North-western Company, at

Camden Town; and sometimes as many as 20,000 parcels daily.

Every other metropolitan station is similarly alive with traffic

inward and outward, London having since the introduction of railways

become more than ever a great distributive centre, to which

merchandise of all kinds converges, and from which it is distributed

to all parts of the country. Mr. Bazley, M.P., stated at a

late public meeting at Manchester that it would probably require ten

millions of horses to convey by road the merchandise traffic which

is now annually carried by railway.

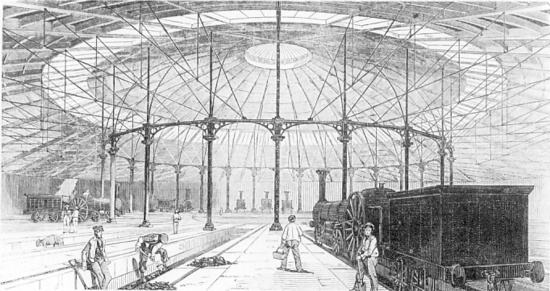

Engine shed at Camden, London and North-Western

Railway.

Railways have also proved of great value in connection with

the Cheap Postage system. By their means it has become

possible to carry letters, newspapers, books, and post parcels in

any quantity, expeditiously and cheaply. The Liverpool and

Manchester line was no sooner opened in 1830 than the Post-office

authorities recognized its utility, and used it for carrying the

mails between the two towns. When the London and Birmingham

line was opened eight years later, mail trains were at once put on,

the directors undertaking to perform the distance of 113 miles

within 5 hours by day and 5½ hours by night. As additional

lines were opened, the old four-horse mail-coaches were gradually

discontinued, until, in 1858, the last of them, the "Derby Dilly"

which ran between Manchester and Derby, was taken off on the opening

of the Midland line to Rowsley.

The increased accommodation provided by railways was found of

essential importance, more particularly after the adoption of the

Cheap Postage system; and that such accommodation was needed will be

obvious from the extraordinary increase which has taken place in the

number of letters and packets sent by post. Thus, in 1839, the

number of chargeable letters carried was only 76 millions, and of

newspapers 44½ millions; whereas, in 1865, the number of letters had

increased to 720 millions, and in 1867 to 775 millions, or more than

tenfold, while the number of newspapers, books, samples, and

patterns (a new branch of postal business begun in 1864) had

increased, in 1865, to 98½ millions.

To accommodate this largely-increasing traffic, the bulk of

which is carried by railway, the mileage run by mail trains in the

United Kingdom has increased from 25,000 miles a day in 1854 (the

first year of which we have any return of the mileage run) to 60,000

miles a day in 1867, or an increase of 240 per cent. The

Post-office expenditure on railway service has also increased, but

not in like proportion, having been £364,000 in the former year, and

£559,575 in the latter, or an increase of 154 per cent. The

revenue, gross and net, has increased still more rapidly. In

1841, the first complete year of the Cheap Postage system, the gross

revenue was £1,359,466, and the net revenue £500,789; in 1854, the

gross revenue was £2,574,407, and the net revenue £1,173,723; and in

1867, the gross revenue was £4,548,129, and the net revenue

£2,127,125, being an increase of 420 per cent compared with 1841,

and of 180 per cent compared with 1854. How much of this net

increase might fairly be credited to the Railway Postal service we

shall not pretend to say, but assuredly the proportion most be very

considerable.

One of the great advantages of railways in connection with

the postal service is the greatly increased frequency of

communication which they provide between all the large towns.

Thus Liverpool has now six deliveries of Manchester letters daily,

while every large town in the kingdom has two or more deliveries of

London letters daily. In 1863, 393 towns had two mails daily

from London; 50 had three mails daily; 7 had four mails a day

from London, and 16 had four mails a day to London; while

3 towns had five mails a day from London, and 6 had five

mails a day to London.

Another feature of the railway mail train, as of the

passenger train, is its capacity to carry any quantity of letters

and post parcels that may require to be carried. In 1838, the

aggregate weight of all the evening mails dispatched from London by

twenty-eight mail-coaches was 4 tons 6 cwt., or an average of about

3¼ cwt each, though the maximum contract weight was 15 cwt.

The mails now are necessarily much heavier, the number of letters

and packets having, as we have seen, increased more than tenfold

since 1839. But it is not the ordinary so much as the

extraordinary mails that are of considerable weighty more

particularly the American, the Continental, and the Australian

mails. It is no unusual thing, we are informed, for the

last-mentioned mail to weigh as much as 40 tons. How many of

the old mail-coaches it would take to carry such a mail the 79

miles' journey to Southampton, with a relay of four horses every

five or seven miles, is a problem for the arithmetician to solve.

But even supposing each coach to be loaded to the maximum weight of

15 cwt per coach, it would require about sixty vehicles and about

1700 horses to carry the 40 tons, besides the coachmen and guards.

A few words, in conclusion, as to the number of men employed

in working and maintaining railways. According to Mr. Mills, [xxviii]

166,047 men and officers were employed in the working of 13,289

miles open in the United Kingdom in 1865, besides 53,923 employed on

lines then under construction. The most numerous body of

workmen is that of the labourers (81,284) employed in the

maintenance of the permanent way. Being mostly picked men from

the labouring class of the adjoining districts, they are paid

considerably higher wages, and hence one of the direct effects of

railways on the labouring population (besides affording them greater

facilities for locomotion) has been to raise the standard of wages

of ordinary labour at least 2s. a week in all the districts into

which they have penetrated. The workmen next in number is that

of the artificers (40,167) employed in constructing and repairing

the rolling-stock; the porters (25,381), the plate-layers (12,901),

guards and brakesmen (5799), firemen (5266), and engine-drivers

(5171). But, besides the employees directly engaged in the

working and maintenance of railways, large numbers of workmen are

also occupied in the manufacture of locomotives and rolling-stock,

and in providing the requisite materials for the permanent way.

Thus the consumption of rails alone averages nearly 400,000 tons a

year in the United Kingdom alone, while the replacing of decayed

sleepers requires about 10,000 acres of forest to be cut down

annually and sawn into sleepers. Taking the various railway

workmen into account, with their families, it will be found that

they represent a total of about three quarters of a million persons,

or about one in fifty of our population, who are dependent on

railways for their subsistence.

While the practical working of railways has, on the whole,

been so satisfactory, the case has been very different as regards

their direction and financial management. The men employed in

the working of railways make it their business to learn it, and,

being responsible, they are under the necessity of taking pains to

do it well; whereas the men who govern and direct them are

practically irresponsible, and may possess no qualification whatever

for the office excepting only the holding of so much stock.

The consequence has been much blundering on the part of these

amateurs, and great loss on the part of the public. Indeed,

what between the confused, contradictory, and often unjust

legislation of Parliament on the one hand, and the carelessness or

incompetency of directors on the other, many once flourishing

concerns have been thrown into a state of utter confusion and

muddle, until railway government has become a by-word of reproach.

And this state of things will probably continue until the

fatal defect of government by Boards—an extremely limited

responsibility, or no responsibility at all—has been rectified by

the appointment, as in France, of executives consisting of a few men

of special ability and trained administrative skill, personally

responsible to their constituents for the due performance of their

respective functions. But the discussion of this subject would

require a treatise, whereas we are now but writing a preface.

Whatever may be said of the financial mismanagement of

railways, there can be no doubt as to the great benefits conferred

by them on the public wherever made. Even those railways which

have exhibited the most "frightful examples" of scheming and

financing, so soon as placed in the hands of practical men to work,

have been found to prove of unquestionable public convenience and

utility. And notwithstanding all the faults and imperfections

that are alleged against railways have been admitted, we think that

they must, nevertheless, be recognized as by far the most valuable

means of communication between men and nations that has yet been

given to the world.

The author's object in publishing this book in its original

form, some ten years since, was to describe, in connection with the

"Life of George Stephenson," the origin and progress of the railway

system, and to show by what moral and material agencies its founders

were enabled to carry their ideas into effect, and to work out

results which even then were of a remarkable character, though they

have since, as above described, become so much more extraordinary.

The favour with which successive editions of the book have been

received has justified the author in his anticipation that such a

narrative would prove of general, if not of permanent interest, and

he has taken pains, in preparing for the press the present, and

probably final edition, to render it, by careful amendment and

revision, more worthy of the public acceptance.

London, May, 1868.

――――♦――――

PREFACE

TO THE EIGHTH EDITION, 1864.

――――――――

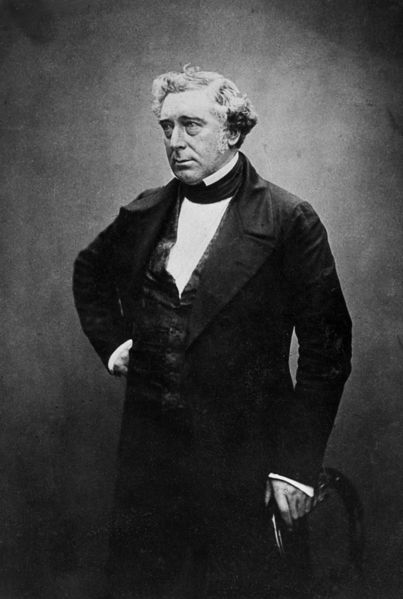

ROBERT STEPHENSON

CIVIL ENGINEER

(1803-59)

The following is a revised and improved edition of "The Life

of George Stephenson," with which is incorporated a Memoir of his

son Robert, late President of the Institute of Civil Engineers.

Since its original appearance in 1857, much additional information

has been communicated to the author relative to the early history of

Railways and the men principally concerned in establishing them, of

which he has availed himself in the present edition.

In preparing the original work for publication, the author

enjoyed the advantage of the cordial co-operation and assistance of

Robert Stephenson, on whom he mainly relied for information as to

the various stages through which the Locomotive passed, and

especially as to his father's share in its improvement.

Through Mr. Stephenson's instrumentality also, the author was

enabled to obtain much valuable information from gentlemen who had

been intimately connected with his father and himself in their early

undertakings—among others, from Mr. Edward Pease, of Darlington; Mr.

Dixon, C.E.; Mr. Sopwith, F.R.S.; Mr. Charles Parker; and Sir Joshua Walmsley.

Most of the facts relating to the early period of George

Stephenson's career were collected from colliers, brakesmen,

enginemen, and others, who had known him intimately, or been

fellow-workmen with him, and were proud to communicate what they

remembered of his early life. The information obtained from

these old men—most of them illiterate, and some broken down by hard

work—though valuable in many respects, was confused, and sometimes

contradictory; but, to insure as much accuracy and consistency of

narrative as possible, the author submitted the MS. to Mr.

Stephenson, and had the benefit of his revision of it previous to

publication.

Mr. Stephenson took a lively interest in the improvement of

the "Life" of his father, and continued to furnish corrections and

additions for insertion in the successive editions of the book which

were called for by the public. After the first two editions

had appeared, he induced several gentlemen, well qualified to supply

additional authentic information, to communicate their recollections

of his father, among whom may be mentioned Mr. T. L. Gooch, C.E.;

Mr. Vaughan, of Snibston; Mr. F. Swanwick, CE.; and Mr. Binns, of

Clayross, who had officiated as private secretaries to George

Stephenson at different periods of his life, and afterward held

responsible offices either under him or in conjunction with him.

The author states these facts to show that the information

contained in this book is of an authentic character, and has been

obtained from the most trustworthy sources. Whether he has

used it to the best purpose or not, he leaves others to judge.

This much, however, he may himself say—that he has endeavoured, to

the best of his ability, to set forth the facts communicated to him

in a simple, faithful, and straightforward manner; and, even if he

has not wholly succeeded in doing this, he has, at all events, been

the means of collecting information on a subject originally

unattractive to professional literary men, and thereby rendered its

farther prosecution comparatively easy to those who may feel called

upon to undertake it.

The author does not pretend to have steered clear of errors

in treating a subject so extensive, and, before he undertook the

labour, comparatively uninvestigated; but, wherever errors have been

pointed out, he has taken the earliest opportunity of correcting

them. With respect to objections taken to the book because of

the undue share of merit alleged to be therein attributed to the

Stephensons in respect of the Railway and the Locomotive, there will

necessarily be various opinions. There is scarcely an

invention or improvement in mechanics but has been the subject of

dispute, and it was to be expected that those who had counter claims

would put them forward in the present case; nor has the author any

reason to complain of the manner in which this has been done.

While George Stephenson is the principal subject in the

following book, his son Robert also forms an essential part of it.

Father and son were so intimately associated in the early period of

their career, that it is difficult, if not impossible, to describe

the one apart from the other. The life and achievements of the

son were in a great measure the complement of the life and

achievements of the father. The care, also, with which the

elder Stephenson, while occupying the position of an obscure engine-wright,

devoted himself to his son's education, and the gratitude with which

the latter repaid the affectionate self-denial of his father,

furnish some of the most interesting illustrations of the personal

character of both.

These views were early adopted by the author and carried out

by him in the preparation of the original work, with the concurrence

of Robert Stephenson, who supplied the necessary particulars

relating to himself. Such portions of these were accordingly

embodied in the narrative as could with propriety be published

during his life-time, and the remaining portions are now added with

the object of rendering more complete the record of the son's life,

as well as the early history of the Railway System.

――――♦――――

CONTENTS.

P A R T I.

CHAPTER I.

SCHEMERS AND PROJECTORS.

Man's Desire for rapid Transit.—Origin of the Railway. — Early Coal

Wagon-ways in the North of England. — Early Attempts to apply the

Power of Wind to drive Carriages.—Sailing-coaches.—Sir Isaac

Newton's Proposal to employ Steam-power.—Dr. Darwin's Speculations

on the Subject.—Mr. Edgeworth's Speculations.—Dr. Darwin's Prophecy.

CHAPTER II.

EARLY LOCOMOTIVE MODELS.

Watt and Robison's proposed Steam-carriage.—Memoir of Joseph Cugnot

and his Road-locomotive.—Francis Moore.—James Watt's Specification

of a Locomotive-engine.—William Murdoch's Model.—William Symington's

model Steam-carriage.—Oliver Evans's model Locomotive.

CHAPTER III.

THE CORNISH LOCOMOTIVE—MEMOIR OF TREVITHICK.

Early Welsh Railway Acts.—Wandsworth, Croydon, and Merstham

Railway.—Boyhood of Trevithick.—Becomes an Engineer.—His

Career.—Constructs a Steam-carriage.—Its Exhibition in

London.—Constructs a Tram-engine.—Its Trial on the Merthyr

Railroad.—Trevithick's Improvements in the Steam-engine.—Attempts to

construct a Tunnel under the Thames.—His numerous Inventions and

Patents.—Engines ordered of him for Peru.—Trevithick a Mining

Engineer in South America.—Is ruined by the Peruvian Revolution.—His

return Home.—His last Patents.—Death and Characteristics.

____________________

P A R T II.

CHAPTER I.

THE NEWCASTLE COAL-FIELD—GEORGE STEPHENSON'S EARLY

YEARS.

Newcastle in ancient Times.—The Coal-trade.—Modern Newcastle.—The

Colliery Workmen.—The Pumping-engines.—The Pitmen.—The Keelmen.—Wylam

Colliery and Village.—George Stephenson's Birthplace.—The Stephenson

Family.—Old Robert Stephenson.—George's Boyhood.—Employed as a

Herd-boy.—Makes Clay Engines.—Employed as Corf-bitter.—Drives the

Gin-horse.—Appointed assistant Fireman.

CHAPTER II.

NEWBURN AND CALLERTON—GEORGE STEPHENSON LEARNS TO BE

AN ENGINE-MAN.

Stephenson's Life at Newburn.—Appointed Engine-man.—Duties of

Flagman.—Study of the Steam-engine.—Experiments in

Bird-hatching.—Learns to Read.—His Schoolmasters.—Progress in

Arithmetic.—His Dog.—Learns to Brake.—Duties of Brakesman.—Begins

Shoe-mending.—Fight with a Pitman.

CHAPTER III.

ENGINE-MAN AT WILLINGTON QUAY AND KILLINGWORTH.

Sobriety and Studiousness.—Removal to Willington Quay, and

Marriage.—Attempts a Perpetual-motion Machine.—William Fairbairn,

C.E., and George Stephenson.—Ballast-heaving.—Cottage Chimney takes

fire.—Birth of his son Robert.—Removal to West Moor,

Killingworth.—Death of his Wife.—Appointed Engine-man at

Montrose.—Return to Killingworth.—Appointed Brakesman at West

Moor.—Is drawn for the Militia.—Thinks of Emigrating.—Takes a

contract for Brakeing.—Improves the Winding-engine.—Cures a

Pumping-engine.—Is appointed Engine-wright of the Colliery.

CHAPTER IV.

THE STEPHENSONS AT KILLINGWORTH—EDUCATION AND

SELF-EDUCATION.

Efforts at Self-improvement.—John Wigham.—Studies in Natural

Philosophy.—Education of Robert Stephenson.—Sent to Brace's School,

Newcastle.—His boyish Tricks.—Stephenson's Cottage, West

Moor.—Mechanical Contrivances.—The Sun-dial at West

Moor.—Stephenson's various Duties as Colliery Engineer.

CHAPTER V.

THE LOCOMOTIVE ENGINE—GEORGE STEPHENSON BEGINS ITS

IMPROVEMENTS.

Slow Progress heretofore made in the Improvement of the

Locomotive.—The Wylam Wagon-way.—Mr. Blackett orders a

Locomotive.—Mr. Blenkinsop's Leeds Locomotive.—Mr. Blackett's second

Engine a Failure.—The improved Wylam Engine.—George Stephenson's

Study of the Subject.—His first Locomotive constructed.—His

Improvement of the Engine, as described by his Son.—Invention of the

Steam-blast.

CHAPTER VI.

INVENTION OF THE "GEORDY" SAFETY LAMP.

Frequency of Colliery Explosions.—Accidents in the Killingworth

Pit.—Stephenson's heroic Conduct.—Proposes to invent a

Safety-lamp.—His first Lamp and its Trial.—Cottage Experiments with

Coal-gas.—His second and third Lamps.—Scene at the Newcastle

Institute.—The Stephenson and Davy Controversy.—The Davy and

Stephenson Testimonials.—Merits of the "Geordy" Lamp.

CHAPTER VII.

GEORGE STEPHENSON'S FARTHER IMPROVEMENTS IN THE

LOCOMOTIVE—ROBERT STEPHENSON AS VIEWER'S APPRENTICE AND STUDENT.

Stephenson's Improvements in the Mine-machinery.—Farther

Improvements in the Locomotive and in the Road.—Experiments on

Friction.—Early Neglect of the Locomotive.—Stephenson again

meditates emigrating to America. —Employed as Engineer of the Hetton

Railway.—Robert Stephenson put Apprentice to a Coal-viewer.—His

Father sends him to Edinburg University.—His Studies

there.—Geological Tour in the Highlands.

CHAPTER VIII.

GEORGE STEPHENSON ENGINEER OF THE STOCKTON AND

DARLINGTON RAILWAY.

Failure of the first public Railways near London.—Want of improved

communications in the Bishop Auckland Coal-district.—Various

Projects devised.—A Railway projected at Darlington.—Edward

Pease.—George Stephenson employed as Engineer.—Mr. Pease's Visit to

Killingworth.—A Locomotive Factory begun at Newcastle.—The Stockton

and Darlington Line constructed.—The public Opening.—The

Coal-traffic.—The first Passenger-traffic by Railway.—The Town of

Middlesborough-on-Tees created by the Railway.

CHAPTER IX.

THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAY PROJECTED.

Insufficiency of the Communication between Liverpool and

Manchester.—A Tram-road projected by Mr. Sandars.—The Line surveyed

by William James.—The Survey a failure.—George Stephenson appointed

Engineer. —A Company formed and a Railroad projected.—The first

Prospectus issued.—Opposition to the Survey.—Speculations as to

Railway Speed.—George Stephenson's Views thought

extravagant.—Article in the "Quarterly".

CHAPTER X.

PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST ON THE LIVERPOOL AND

MANCHESTER BILL.

The Bill before Parliament.—The Evidence.—George Stephenson in the

Witness-box.—Examined as to Speed.—His Cross-examination.—Examined

as to the possibility of constructing a Line on Chat Moss.—Mr.

Harrison's Speech.—Mr. Giles's Evidence as to Chat Moss.—Mr.

Alderson's Speech.—The Bill lost.—Stephenson's Vexation.—The Bill

revived, with the Messrs. Rennie as Engineers.—Sir Isaac Coffin's

prophecies of Disaster.—The Act passed.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAT MOSS—CONSTRUCTION OF THE LIVERPOOL AND

MANCHESTER RAILWAY.

George Stephenson again appointed Engineer of the Railway.—Chat Moss

described.—The resident Engineers of the Line.—George Stephenson's

Theory of a Floating Road on the Moss.—Operations begun.—The

Tar-barrel Drains.—The Embankment sinks in the Moss.—Proposed

Abandonment of the Works.—Stephenson's Perseverance.—The Obstacles

conquered.—The Tunnel at Liverpool.—The Olive Mount Cutting.—The

Sankey Viaduct.—Stephenson's great Labours.—His daily Life.—Evenings

at Home.

CHAPTER XII.

ROBERT STEPHENSON'S RESIDENCE IN COLUMBIA AND

RETURN—THE "BATTLE OF THE LOCOMOTIVE."

Robert Stephenson appointed Mining Engineer in Colombia. — Mule

Journey to Bogotá—Mariquita.—Silver Mining.—Difficulties with the

Cornishmen.—His Cottage at Santa Anna.—Resigns his

Appointment.—Meeting with Trevithick.—Voyage to New York, and

Shipwreck.—Returns to Newcastle, and takes Charge of his Locomotive

Factory. — Discussion as to the Working Power of the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway.—Walker and Rastrick's Report.—A Prize offered

for the best Locomotive.—Invention of the Multitubular Boiler.—Henry

Booth.—Construction of the "Rocket."—The Locomotive Competition at

Rainhill.— Triumph of the "Rocket."

CHAPTER XIII.

OPENING OF THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAY, AND

EXTENSION OF THE RAILWAY SYSTEM.

The Railway finished.—Organisation of the Working.—The public

Opening.—Fatal Accident to Mr. Huskisson.—The Traffic

begun.—Improvements in the Road, Rolling Stock, and

Locomotive.—Steam-carriages tried on common Roads.—New Railway

Projects.—Opposition to Railways in the South of England.—Stephenson

appointed Engineer of Leicester and Swannington Railway.—George

removes to Snibston and sinks for Coal —His character as a Master.

CHAPTER XIV.

ROBERT STEPHENSON CONSTRUCTS THE LONDON AND

BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY.

The London and Birmingham Railway projected.—George and Robert

Stephenson appointed Engineers.—An Opposition organised.—Public

Meetings against the Scheme—Robert Stephenson's Interview with Sir

A. Cooper.—The Survey obstructed.—The Line resurveyed.—The Bill in

Parliament.—Thrown out in the Lords.—The Project revived.—The Act

obtained.—The Works let in Contracts.—Difficulties of the

Undertaking.—The Line described.—Blisworth Cutting.—Primrose Hill

Tunnel.— Kilby Tunnel.—Its Construction described.—Failures of

Contractors.—Magnitude of the Works.—The Railway navies.