|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XII.

ROBERT STEPHENSON'S RESIDENCE IN COLOMBIA, AND RETURN—THE BATTLE OF

THE LOCOMOTIVE—"THE ROCKET."

WE return to the

career of Robert Stephenson, who was absent from England during the

construction of the Liverpool Railway, but was now about to rejoin

his father and take part in "the battle of the locomotive" which

was impending.

We have seen that, on his return from Edinburgh College at the end

of 1821, he had assisted in superintending the works of the Hetton

Railway until its opening in 1822, after which he proceeded to

Liverpool to take part with Mr. James in surveying the proposed

railway there. In the following year we found him assisting his

father in the working survey of the Stockton and Darlington Railway; and when the Locomotive Engine Works were started in Forth Street,

Newcastle, he took an active part in that concern. "The factory,"

he says, "was in active operation in 1824; I left England for

Colombia in June of that year, having finished drawing the designs

of the Brusselton stationary engines for the Stockton and Darlington

Railway before I left." [p.301]

Speculation was very rife at the time, and among the most promising

adventures were the companies organized for the purpose of working

the gold and silver mines of South America. Great difficulty was

experienced in finding mining engineers capable of carrying out

those projects, and young men of even the most moderate experience

were eagerly sought after. The Colombian Mining Association of

London offered an engagement to young Stephenson to go out to Mariquita and take charge of the engineering operations of that

company. Robert was himself desirous of accepting it, but his father

said it would first be necessary to ascertain whether the proposed

change would be for his good. His health had been very delicate for

some time, partly occasioned by his rapid growth, but principally

because of his close application to work and study. Father and son

proceeded together to call upon Dr. Headlam, the eminent physician

of Newcastle, to consult him on the subject. During the

examination which ensued, Robert afterward used to say that he felt

as if he were upon trial for life or death. To his great

relief, the doctor pronounced that a temporary residence in a warm

climate was the very thing likely to be most beneficial to him.

The appointment was accordingly accepted, and, before many weeks had

passed, Robert Stephenson had set sail for South America.

After a tolerably prosperous voyage he landed at La Guayra,

on the north coast of Venezuela, on the 23d of July, from thence

proceeding to Caraccas, the capital of the district, about fifteen

miles inland. There he remained for two months, unable to

proceed in consequence of the wretched state of the roads in the

interior. He contrived, however, to make occasional excursions

in the neighbourhood with an eye to the mining business on which he

had come. About the beginning of October he set out for

Bogotá, the capital of Colombia or New Granada. The distance

was about twelve hundred miles, through a very difficult region, and

it was performed entirely upon mule-back, after the fashion of the

country.

In the course of the journey Robert visited many of the

districts reported to be rich in minerals, but he met with few

traces except of copper, iron, and coal, with occasional indications

of gold and silver. He found the people ready to furnish

information, which, however, when tested, usually proved worthless.

A guide, whom he employed for weeks, kept him buoyed up with the

hope of finding richer mining places than he had yet seen; but when

he professed to be able to show him mines of "brass, steel, alcohol,

and pinchbeck," Stephenson discovered him to be an incorrigible

rogue, and immediately dismissed him. At length our traveller

reached Bogotá, and after an interview with Mr. Illingworth, the

commercial manager of the Mining Company, he proceeded to Honda,

crossed the Magdalena, and shortly after reached the site of his

intended operations on the eastern slope of the Andes.

Mr. Stephenson used afterward to speak in glowing terms of

this his first mule-journey in South America. Every thing was

entirely new to him. The variety and beauty of the indigenous

plants, the luxurious tropical vegetation, the appearance, manners,

and dress of the people, and the mode of travelling, were altogether

different from every thing he had before seen. His own

travelling garb, also must have been strange even to himself.

"My hat," he says, "was of plaited grass, with a crown nine inches

in height, surrounded by a brim of six inches; a white cotton suit;

and a ruana of blue and crimson plaid, with a hole in the

centre for the head to pass through. This cloak is admirably

adapted for the purpose, amply covering the rider and mule, and at

night answering the purpose of a blanket in the net-hammock, which

is made from the fibres of the aloe, and which every traveller

carries before him on his mule, and suspends to the trees or in

houses, as occasion may require."

The part of the journey which seems to have made the most

lasting impression on his mind was that between Bogotá and the

mining district in the neighbourhood of Mariquita. As he

ascended the slopes of the mountain range, and reached the first

step of the table-land, he was struck beyond expression with the

noble view of the valley of Magdalena behind him, so vast that he

failed in attempting to define the point at which the course of the

river blended with the horizon. Like all travellers in the

district, he noted the remarkable changes of climate and vegetation

as he rose from the burning plains toward the fresh breath of the

mountains. From an atmosphere as hot as that of an oven he

passed into delicious cool air, until, in his onward and upward

journey, a still more temperate region was reached, the very

perfection of climate. Before him rose the majestic

Cordilleras, forming a rampart against the western sky, and at

certain times of the day looking black, sharp, and even at their

summit almost like a wall.

Our engineer took up his abode for a time at Mariquita, a

fine old city, though then greatly fallen into decay. During

the period of the Spanish dominion it was an important place, most

of the gold and silver convoys passing through it on their way to

Cartagena, there to be shipped in galleons for Europe. The

Mountainous country to the west was rich in silver, gold, and other

metals, and it was Mr. Stephenson's object to select the best site

for commencing operations for the company. With this object he

"prospected" about in all directions, visiting long-abandoned mines,

and analyzing specimens obtained from many quarters. The mines

eventually fixed upon as the scene of his operations were those of

La Manta and Santa Anna, long before worked by the Spaniards,

though, in consequence of the luxuriance and rapidity of the

vegetation, all traces of the old workings had become completely

overgrown and lost. Every thing had to be begun anew.

Roads had to be cut to open a way to the mines, machinery had to be

erected, and the ground opened up, when some of the old adits were

eventually hit upon. The native peons or labourers were not

accustomed to work, and they usually contrived to desert when they

were not watched, so that very little progress could be made until

the arrival of the expected band of miners from England. The

authorities were by no means helpful, and the engineer was driven to

an old expedient with the object of overcoming this difficulty.

"We endeavour all we can," he says, in one of his letters, "to make

ourselves popular, and this we find most effectually accomplished by

'regaling the venal beasts.'" He also gave a ball at

Mariquita, which passed off with éclat, the governor from Honda,

with a host of friends, honouring it with their presence. It

was, indeed, necessary to "make a party" in this way, as other

schemers were already trying to undermine the Colombian Company in

influential directions. The engineer did not exaggerate when

he said, "The uncertainty of transacting business in this country is

perplexing beyond description." In the mean time labourers had

been attracted to Santa Anna, which became, the engineer wrote,

"like an English fair on Sundays: people flock to it from all

quarters to buy beef and chat with their friends. Sometimes

three or four torros are slaughtered in a day. The people now

eat more beef in a week than they did in two months before, and they

are consequently getting fat." [p.304]

At last Stephenson's party of miners arrived from England,

but they gave him even more trouble than the peons had done.

They were rough, drunken, and sometimes ungovernable. He set

them to work at the Santa Anna mine without delay, and at the same

time took up his abode among them, "to keep them," he said, "if

possible, from indulging in the detestable vice of drunkenness,

which, if not put a stop to, will eventually destroy themselves, and

involve the mining association in ruin." To add to his

troubles, the captain of the miners displayed a very hostile and

insubordinate spirit, quarrelled and fought with the men, and was

insolent to the engineer himself. The captain and his gang,

being Cornishmen, told Robert to his face that because he was a

North-country man, and not brought up in Cornwall, it was impossible

that he should know any thing of mining. Disease also fell

upon him—first fever, and then visceral derangement, followed by a

return of his "old complaint, a feeling of oppression in the

breast." No wonder that in the midst of these troubles he

should longingly speak of returning to his native land. But he

stuck to his post and his duty, kept up his courage, and by a

mixture of mildness and firmness, and the display of great coolness

and judgment, he contrived to keep the men to their work, and

gradually to carry forward the enterprise which he had undertaken.

By the beginning of July, 1826, quietness and order had been

restored, and the works were proceeding more satisfactorily, though

the yield of silver was not as yet very promising, the engineer

being of opinion that at least three years' diligent and costly

operations would be necessary to render the mines productive.

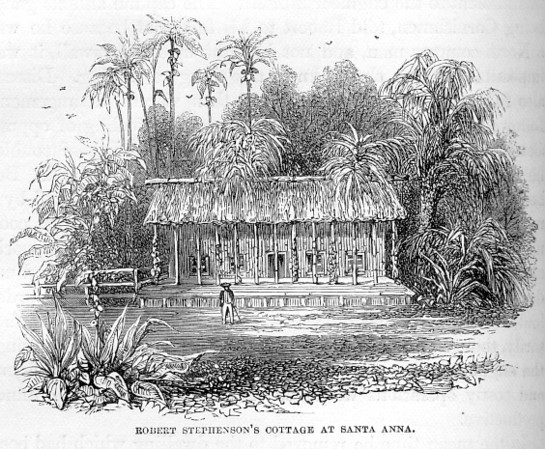

In the mean time he removed to the dwelling which had been

erected for his accommodation at Santa Anna. It was a

structure speedily raised after the fashion of the country.

The walls were of split and flattened bamboo, tied together with the

long fibres of a dried climbing plant; the roof was of palm-leaves,

and the ceiling of reeds. When an earthquake shook the

district—for earthquakes were frequent—the inmates of such a fabric

merely felt as if shaken in a basket, without sustaining any harm.

In front of the cottage lay a woody ravine, extending almost to the

base of the Andes, gorgeously clothed in primeval

vegetation—magnolias, palms, bamboos, tree-ferns, acacias, cedars;

and towering over all were the great almendrons, with their smooth,

silvery stems, bearing aloft noble clusters of pure white blossom.

The forest was haunted by myriads of gay-insects, butterflies with

wings of dazzling lustre, birds of brilliant plumage, humming-birds,

golden orioles, toucans, and a host of solitary warblers. But

the glorious sunsets seen from his cottage-porch more than all

astonished and delighted the young engineer, and he was accustomed

to say that, after having witnessed them, he was reluctant to accuse

the ancient Peruvians of idolatry.

But all these natural beauties failed to reconcile him to the

harassing difficulties of his position, which continued to increase

rather than diminish. He was hampered by the action of the

board at home, who gave ear to hostile criticisms on his reports;

and although they afterward made handsome acknowledgment of his

services, he felt his position to be altogether unsatisfactory.

He therefore determined to leave at the expiry of his three years

engagement, and communicated his decision to the directors

accordingly. [p.306]

On receiving his letter, the board, through Mr. Richardson,

of Lombard Street, one of the directors, communicated with his

father at Newcastle, representing that if he would allow his son to

remain in Colombia the company would make it "worth his while."

To this the father gave a decided negative, and intimated that he

himself urgently needed his son's assistance, and that he must

return at the expiry of his three years' term—a decision, Robert

wrote, "at which I feel much gratified, as it is clear that he is as

anxious to have me back in England as I am to get there."

At the same time, Edward Pease, a principal partner in the

Newcastle firm, privately wrote Robert to the following effect,

urging his return home: "I can assure thee that the business at

Newcastle, as well as thy father's engineering, have suffered very

much from thy absence, and, unless thou soon return, the former will

be given up, as Mr. Longridge is not able to give it that attention

it requires; and what is done is not done with credit to the house."

The idea of the manufactory being given up, which Robert had

laboured so hard to establish before leaving England, was painful to

him in the extreme, and he wrote to Mr. Illingworth, strongly urging

that arrangements should be made for enabling him to leave without

delay. In the mean time he was laid prostrate by another

violent attack of aguish fever; and when able to write, in June,

1827, he expressed himself as "completely wearied and worn down with

vexation."

At length, when he was sufficiently recovered from his attack

and able to travel, he set out on his voyage homeward in the

beginning of August. At Mompox, on his way down the River

Magdalena, he met Mr. Bodmer, his successor, with a fresh party from

England, on their way up the country to the quarry which he had just

quitted. Next day, six hours after leaving Mompox, a

steam-boat was met ascending the river, with Bolivar the Liberator

on board, on his way to St. Bogotá; and it was a mortification to

our engineer that he had only a passing sight of that distinguished

person. It was his intention, on leaving Mariquita, to visit

the Isthmus of Panamá on his way home, for the purpose of inquiring

into the practicability of cutting a canal to unite the Atlantic and

Pacific—a project which then formed the subject of considerable

public discussion; but Mr. Bodmer having informed him at Mompox that

such a visit would be inconsistent with the statements made to the

London Board that his presence was so anxiously desired at home, he

determined to embrace the first opportunity of proceeding to New

York.

Arrived at the port of Cartagena, he found himself under the

necessity of waiting some time for a ship. The delay was very

irksome to him, the more so as the place was then desolated by the

ravages of the yellow fever. While sitting one day in the

large, bare, comfortless public room of the miserable hotel at which

he put up, he observed two strangers, whom he at once perceived to

be English. One of the strangers was a tall, gaunt man,

shrunken and hollow-looking, shabbily dressed, and apparently

poverty-stricken. On making inquiry, he found it was

Trevithick, the builder of the first railroad locomotive! He

was returning home from the gold mines of Peru penniless.

Robert Stephenson lent him £50 to enable him to reach England; and

though he was afterward heard of as an inventor there, he had no

farther part in the ultimate triumph of the locomotive.

But Trevithick's misadventures on this occasion had not yet

ended, for before he reached New York he was wrecked, and Robert

Stephenson with him. The following is the account of the

voyage, "big with adventures," as given by the latter in a letter to

his friend Illingworth:

"At first we had very little foul

weather, and, indeed, were for several days becalmed among the

islands, which was so far fortunate, for a few degrees farther north

the most tremendous gales were blowing, and they appear (from our

future information) to have wrecked every vessel exposed to their

violence. We had two examples of the effects of the hurricane;

for, as we sailed north, we took on board the remains of two crews

found floating about on dismantled hulls. The one had been

nine days without food of any kind except the carcasses of two of

their companions who had died a day or two previously from fatigue

and hunger. The other crew had been driven about for six days,

and were not so dejected, but reduced to such a weak state that they

were obliged to be drawn on board our vessel by ropes. A brig

bound for Havana took part of the men, and we took the remainder.

To attempt any description of my feelings on witnessing such scenes

would be in vain. You will not be surprised to learn that I

felt somewhat uneasy at the thought that we were so far from

England, and that I also might possibly suffer similar shipwreck;

but I consoled myself with the hope that fate would be more kind to

us. It was not so much so, however, as I had flattered myself;

for on voyaging toward New York, after we had made the land, we ran

aground about midnight. The vessel soon filled with water,

and, being surrounded by the breaking surf, the ship shortly split

up, and before morning our situation became perilous. Masts

and all were cut away to prevent the hull rocking, but all we could

do was of no avail. About eight o'clock on the following

morning, after a most miserable night, we were taken off the wreck,

and were so fortunate as to reach the shore. I saved my

minerals, but Empson lost part of his botanical collection.

Upon the whole, we got off well; and, had I not been on the American

side of the Atlantic, I 'guess' I would not have gone to sea again."

After a short tour in the United States and Canada, Robert

Stephenson and his friend took ship for Liverpool, where they

arrived at the end of November, and at once proceeded to Newcastle.

The factory, we have seen, was by no means in a prosperous state.

During the time Robert had been in America it had been carried on at

a considerable loss; and Edward Pease, very much disheartened,

wished to retire from it, but George Stephenson being unable to

raise the requisite money to buy him out, the establishment was of

necessity carried on by its then partners until the locomotive could

be established in public estimation as a practicable and economical

working power. Robert Stephenson immediately instituted a

rigid inquiry into the working of the concern, unravelled the

accounts, which had been allowed to fall into confusion during his

father's absence at Liverpool, and very shortly succeeded in placing

the affairs of the factory in a more healthy condition. In all

this he had the hearty support of his father, as well as of the

other partners.

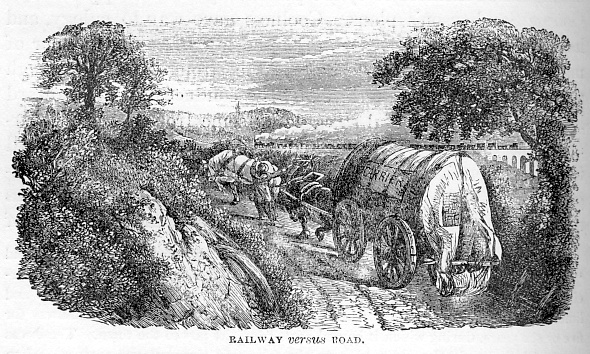

The works of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway were now

approaching completion. But, strange to say, the directors had

not yet decided as to the tractive power to be employed in working

the line when opened for traffic. The differences of opinion

among them were so great as apparently to be irreconcilable.

It was necessary, however, that they should come to some decision

without farther loss of time, and many board meetings were

accordingly held to discuss the subject. The old-fashioned and

well-tried system of horse-haulage was not without its advocates;

but, looking at the large amount of traffic which there was to be

conveyed, and at the probable delay in the transit from station to

station if this method were adopted, the directors, after a visit

made by them to the Northumberland and Durham railways in 1828, came

to the conclusion that the employment of horse-power was

inadmissible.

Fixed engines had many advocates; the locomotive very few: it

stood as yet almost in a minority of one—George Stephenson.

The prejudice against the employment of the latter power had even

increased since the Liverpool and Manchester Bill underwent its

first ordeal in the House of Commons. In proof of this, it may

be mentioned that the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway Act was

conceded in 1829 on the express condition that it should not

be worked by locomotives, but by horses only.

Grave doubts still existed as to the practicability of

working a large traffic by means of travelling engines. The

most celebrated engineers offered no opinion on the subject.

They did not believe in the locomotive, and would scarcely take the

trouble to examine it. The ridicule with which George

Stephenson had been assailed by the barristers before the

Parliamentary Committee had not been altogether distasteful to them.

Perhaps they did not relish the idea of a man who had picked up his

experience in Newcastle coal-pits appearing in the capacity of a

leading engineer before Parliament, and attempting to establish a

new system of internal communication in the country.

The directors could not disregard the adverse and conflicting

views of the professional men whom they consulted. But

Stephenson had so repeatedly and earnestly urged upon them the

propriety of making a trial of the locomotive before coming to any

decision against it, that they at length authorized him to proceed

with the construction of one of his engines by way of experiment.

In their report to the proprietors at their annual meeting on the

27th of March, 1828, they state that they had, after due

consideration, authorized the engineer "to prepare a locomotive

engine, which, from the nature of its construction and from the

experiments already made, he is of opinion will be effective for the

purposes of the company, without proving an annoyance to the

public." The locomotive thus ordered was placed upon the line

in 1829, and was found of great service in drawing the wagons full

of marl from the two great cuttings.

In the mean time the discussion proceeded as to the kind of

power to be permanently employed for the working of the railway.

The directors were inundated with schemes of all sorts for

facilitating locomotion. The projectors of England, France,

and America seemed to be let loose upon them. There were plans

for working the wagons along the line by water-power. Some

proposed hydrogen, and others carbonic acid gas. Atmospheric

pressure had its eager advocates. And various kinds of fixed

and locomotive steam-power were suggested. Thomas Gray urged

his plan of a greased road with cog-rails; and Messrs. Vignolles and

Ericsson recommended the adoption of a central friction-rail,

against which two horizontal rollers under the locomotive, pressing

upon the sides of this rail, were to afford the means of ascending

the inclined planes.

The directors felt themselves quite unable to choose from

amid this multitude of projects. Their engineer expressed

himself as decidedly as heretofore in favour of smooth rails and

locomotive engines, which, he was confident, would be found the most

economical and by far the most convenient moving power that could be

employed. The Stockton and Darlington Railway being now at

work, another deputation went down personally to inspect the fixed

and locomotive engines on that line, as well as at Hetton and

Killingworth. They returned to Liverpool with much

information; but their testimony as to the relative merits of the

two kinds of engines was so contradictory, that the directors were

as far from a decision as ever.

They then resolved to call to their aid two professional

engineers of high standing, who should visit the Darlington and

Newcastle railways, carefully examine both modes of working—the

fixed and the locomotive—and report to them fully on the subject.

The gentlemen selected were Mr. Walker, of Limehouse, and Mr.

Rastrick, of Stourbridge. After carefully examining the

working of the Northern lines, they made their report to the

directors in the spring of 1829. They concurred in the opinion

that the cost of an establishment of fixed engines would be somewhat

greater than that of locomotives to do the same work, but they

thought the annual charge would be less if the former were adopted.

They calculated that the cost of moving a ton of goods thirty miles

by fixed engines would be 6.40d., and by locomotives, 8.36d.,

assuming a profitable traffic to be obtained both ways. At the

same time, it was admitted that there appeared more grounds for

expecting improvements in the construction and working of

locomotives than of stationary engines. "On the whole,

however, and looking especially at the computed annual charge of

working the road on the two systems on a large scale, Messrs. Walker

and Rastrick were of opinion that fixed engines were preferable, and

accordingly recommended their adoption to the directors." [p.312]

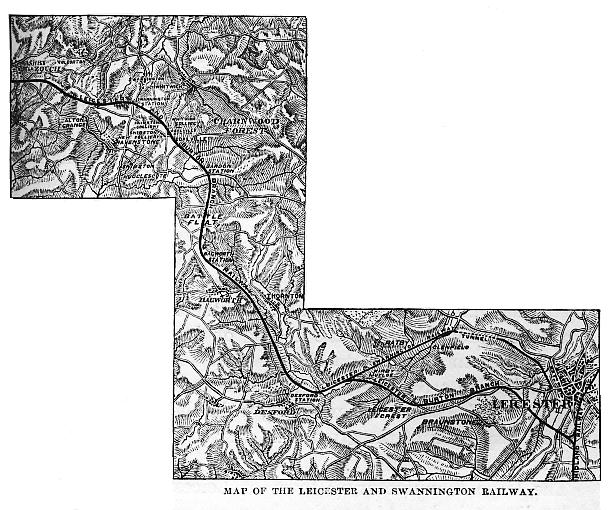

And in order to carry the system recommended by them into effect,

they proposed to divide the railroad between Liverpool and

Manchester into nineteen stages of about a mile and a half each,

with twenty-one engines fixed at the different points to work the

trains forward.

Such was the result, so far, of George Stephenson's labours.

The two best practical engineers of the day concurred in reporting

substantially in favour of the employment of fixed engines.

Not a single professional man of eminence could be found to coincide

with the engineer of the railway in his preference for locomotive

over fixed engine power. He had scarcely a supporter, and the

locomotive system seemed on the eve of being abandoned. Still

he did not despair. With the profession against him, and

public opinion against him—for the most frightful stories went

abroad respecting the dangers, the unsightliness, and the nuisance

which the locomotive would create—Stephenson held to his purpose.

Even in this, apparently the darkest hour of the locomotive, he did

not hesitate to declare that locomotive railroads would, before many

years had passed, be "the great highways of the world."

He urged his views upon the directors in all ways, in season,

and, as some of them thought, out of season. He pointed out

the greater convenience of locomotive power for the purposes of a

public highway, likening it to a series of short unconnected chains,

any one of which could be removed and another substituted without

interruption to the traffic; whereas the fixed-engine system might

be regarded in the light of a continuous chain extending between the

two termini, the failure of any link of which would derange the

whole. [p.313] But the

fixed-engine party were very strong at the board, and, led by Mr.

Cropper, they urged the propriety of forthwith adopting the report

of Messrs. Walker and Rastrick. Mr. Sandars and Mr. William

Rathbone, on the other hand, desired that a fair trial should be

given to the locomotive; and they with reason objected to the

expenditure of the large capital necessary to construct the proposed

engine-houses, with their fixed engines, ropes, and machinery, until

they had tested the powers of the locomotive as recommended by their

own engineer. George Stephenson continued to urge upon them

that the locomotive was yet capable of great improvements, if proper

inducements were held out to inventors and machinists to make them;

and he pledged himself that, if time were given him, he would

construct an engine that should satisfy their requirements, and

prove itself capable of working heavy loads along the railway with

speed, regularity, and safety. At length, influenced by his

persistent earnestness not less than by his arguments, the

directors, at the suggestion of Mr. Harrison, determined to offer a

prize of £500 for the best locomotive engine, which, on a certain

day, should be produced on the railway, and perform certain

specified conditions in the most satisfactory manner. [p.314]

The requirements of the directors as to speed were not

excessive. All that they asked for was that ten miles an hour

should be maintained. Perhaps they had in mind the

animadversions of the "Quarterly Reviewer" on the absurdity of

travelling at a greater velocity, and also the remarks published by

Mr. Nicholas Wood, whom they selected to be one of the judges of the

competition, in conjunction with Mr. Rastrick, of Stourbridge, and

Mr. Kennedy, of Manchester.

It was now felt that the fate of railways in a great measure

depended upon the issue of this appeal to the mechanical genius of

England. When the advertisement of the prize for the best

locomotive was published, scientific men began more particularly to

direct their attention to the new power which was thus struggling

into existence. In the mean time public opinion on the subject

of railway working remained suspended, and the progress of the

undertaking was watched with intense interest.

During the progress of this important controversy with

reference to the kind of power to be employed in working the

railway, George Stephenson was in constant communication with his

son Robert, who made frequent visits to Liverpool for the purpose of

assisting his father in the preparation of his reports to the board

on the subject. Mr. Swanwick remembers the vivid interest of

the evening discussions which then took place between father and son

as to the best mode of increasing the powers and perfecting the

mechanism of the locomotive. He wondered at their quick

perception and rapid judgment on each other's suggestions; at the

mechanical difficulties which they anticipated and provided for in

the practical arrangement of the machine; and he speaks of these

evenings as most interesting displays of two actively ingenious and

able minds stimulating each other to feats of mechanical invention,

by which it was ordained that the locomotive engine should become

what it now is. These discussions became more frequent, and

still more interesting, after the public prize had been offered for

the best locomotive by the directors of the railway, and the working

plans of the engine which they proposed to construct had to be

settled.

One of the most important considerations in the new engine

was the arrangement of the boiler and the extension of its heating

surface to enable steam enough to be raised rapidly and continuously

for the purpose of maintaining high rates of speed—the effect of

high-pressure engines being ascertained to depend mainly upon the

quantity of steam which the boiler can generate, and upon its degree

of elasticity when produced. The quantity of steam so

generated, it will be obvious, must chiefly depend upon the quantity

of fuel consumed in the furnace, and, by necessary consequence, upon

the high rate of temperature maintained there.

It will be remembered that in Stephenson's first Killingworth

engines he invited and applied the ingenious method of stimulating

combustion in the furnace by throwing the waste steam into the

chimney after performing its office in the cylinders, thereby

accelerating the ascent of the current of air, greatly increasing

the draught, and consequently the temperature of the fire.

This plan was adopted by him, as we have seen, as early as 1815, and

it was so successful that he himself attributed to it the greater

economy of the locomotive as compared with horsepower. Hence

the continuance of its use upon the Killingworth Railway.

Though the adoption of the steam-blast greatly quickened

combustion and contributed to the rapid production of high-pressure

steam, the limited amount of heating surface presented to the fire

was still felt to be an obstacle to the complete success of the

locomotive engine. Mr. Stephenson endeavoured to overcome this

by lengthening the boilers and increasing the surface presented by

the flue-tubes. The "Lancashire Witch," which he built for the

Bolton and Leigh Railway, and used in forming the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway embankments, was constructed with a double tube,

each of which contained a fire, and passed longitudinally through

the boiler. But this arrangement necessarily led to a

considerable increase in the weight of those engines, which amounted

to about twelve tons each; and as six tons was the limit allowed for

engines admitted to the Liverpool competition, it was clear that the

time was come when the Killingworth engine must undergo a farther

important modification.

For many years previous to this period, ingenious mechanics

had been engaged in attempting to solve the problem of the best and

most economical boiler for the production of high-pressure steam.

The use of tubes in boilers for increasing the heating

surface had long been known. As early as 1780, Matthew Boulton

employed copper tubes longitudinally in the boiler of the Wheal Busy

engine in Cornwall—the fire passing through the tubes—and it was

found that the production of steam was thereby considerably

increased. [p.317] The

use of tubular boilers afterward became common in Cornwall. In

1803, Woolf, the Cornish engineer, patented a boiler with tubes,

with the same object of in creasing the heating surface. The

water was inside the tubes, and the fire of the boiler

outside. Similar expedients were proposed by other inventors.

In 1815 Trevithick invented his light high-pressure boiler for

portable purposes, in which, to "expose a large surface to the

fire," he constructed the boiler of a number of small perpendicular

tubes "opening into a common reservoir at the top." In 1823 W.

H. James contrived a boiler composed of a series of annular

wrought-iron tubes, placed side by side and bolted together, so as

to form by their union a long cylindrical boiler, in the centre of

which, at the end, the fireplace was situated. The fire played

round the tubes, which contained the water. In 1826 James

Neville took out a patent for a boiler with vertical tubes

surrounded by the water, through which the heated air of the furnace

passed, explaining also in his specification that the tubes might be

horizontal or inclined, according to circumstances. Mr.

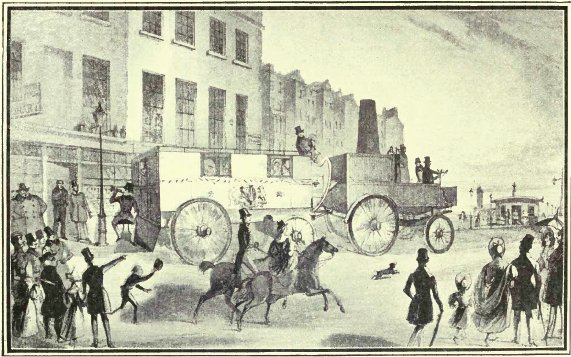

Goldsworthy Gurney, the persevering adaptor of steam-carriages to

travelling on common roads, applied the tubular principle in the

boiler of his engine, in which the steam was generated within the

tubes; while the boiler invented by Messrs. Summers and Ogle for

their turnpike-road steam-carriage consisted of a series of tubes

placed vertically over the furnace, through which the heated air

passed before reaching the chimney.

About the same time George Stephenson was trying the effect

of introducing small tubes in the boilers of his locomotives, with

the object of increasing their evaporative power. Thus, in

1829, he sent to France two engines constructed at the Newcastle

works for the Lyons and St. Etienne Railway, in the boilers of which

tubes were placed containing water. The heating surface was

thus considerably increased; but the expedient was not successful,

for the tubes, becoming furred with deposit, shortly burned out and

were removed. It was then that M. Seguin, the engineer of the

railway, pursuing the same idea, is said to have adopted his plan of

employing horizontal tubes through which the heated air passed in

streamlets, and for which he took out a French patent.

In the mean time Mr. Henry Booth, secretary to the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway, whose attention had been directed to the

subject on the prize being offered for the best locomotive to work

that line, proposed the same method, which, unknown to him, Matthew

Boulton had employed, but not patented, in 1780, and James Neville

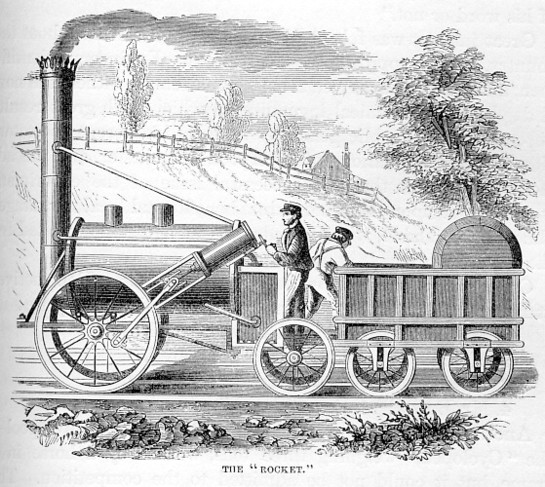

had patented, but not employed, in 1826; and it was carried into

effect by Robert Stephenson in the construction of the "Rocket,"

which won the prize at Rainhill in October, 1829. The

following is Mr. Booth's account in a letter to the author:

"I was in almost daily

communication with Mr. Stephenson at the time, and I was not aware

that he had any intention of competing for the prize till I

communicated to him my scheme of a multi-tubular boiler. This

new plan of boiler comprised the introduction of numerous small

tubes, two or three inches in diameter, and less than one eighth of

an inch thick, through which to carry the fire, instead of a single

tube or flue eighteen inches in diameter, and about half an inch

thick, by which plan we not only obtain a very much larger heating

surface, but the heating surface is much more effective, as there

intervenes between the fire and the water only a thin sheet of

copper or brass, not an eighth of an inch thick, instead of a plate

of iron of four times the substance, as well as an inferior

conductor of heat.

"When the conditions of trial were published, I communicated

my multitubular plan to Mr. Stephenson, and proposed to him that we

should jointly construct an engine and compete for the prize.

Mr. Stephenson approved the plan, and agreed to my proposal.

He settled the mode in which the fire-box and tubes were to be

mutually arranged and connected, and the engine was constructed at

the works of Messrs. Robert Stephenson and Co., Newcastle-on-Tyne.

"I am ignorant of M. Seguin's proceedings in France, but I

claim to be the inventor in England, and feel warranted in stating,

without reservation, that until I named my plan to Mr. Stephenson,

with a view to compete for the prize at Rainhill, it had not been

tried, and was not known in this country."

From the well-known high character of Mr. Booth, we believe

his statement to be made in perfect good faith, and that he was as

much in ignorance of the plan patented by Neville as he was as of

that of Seguin. As we have seen, from the many plans of

tubular boilers invented during the preceding thirty years, the idea

was not by any means new; and we believe Mr. Booth to be entitled to

the merit of inventing the method by which the multitubular

principle was so effectually applied in the construction of the

famous "Rocket" engine.

The principal circumstances connected with the construction

of the "Rocket," as described by Robert Stephenson to the author,

may be briefly stated. The tubular principle was adopted in a

more complete manner than had yet been attempted. Twenty-five

copper tubes, each three inches in diameter, extended from one end

of the boiler to the other, the heated air passing through them on

its way to the chimney; and the tubes being surrounded by the water

of the boiler, it will be obvious that a large extension of the

heating surface was thus effectually secured. The principal

difficulty was in fitting the copper tubes in the boiler-ends so as

to prevent leakage. They were manufactured by a Newcastle

coppersmith, and soldered to brass screws which were screwed into

the boiler-ends, standing out in great knobs. When the tubes

were thus fitted, and the boiler was filled with water, hydraulic

pressure was applied; but the water squirted out at every joint, and

the factory floor was soon flooded. Robert went home in

despair; and in the first moment of grief he wrote to his father

that the whole thing was a failure. By return of post came a

letter from his father, telling him that despair was not to be

thought of—that he must "try again;" and he suggested a mode of

overcoming the difficulty, which his son had already anticipated and

proceeded to adopt. It was, to bore clean holes in the

boiler-ends, fit in the smooth copper tubes as tightly as possible,

solder up, and then raise the steam. This plan succeeded

perfectly, the expansion of the copper tubes completely filling up

all interstices, and producing a perfectly water-tight boiler,

capable of withstanding extreme external pressure.

The mode of employing the steam-blast for the purpose of

increasing the draught in the chimney was also the subject of

numerous experiments. When the engine was first tried, it was

thought that the blast in the chimney was not sufficiently strong

for the purpose of keeping up the intensity of the fire in the

furnace, so as to produce high-pressure steam with the required

velocity. The expedient was therefore adopted of hammering the

copper tubes at the point at which they entered the chimney, whereby

the blast was considerably sharpened; and on a farther trial it was

found that the draught was increased to such an extent as to enable

abundance of steam to be raised. The rationale of the blast

may be simply explained by referring to the effect of contracting

the pipe of a water-hose, by which the force of the jet of water is

proportionately increased. Widen the nozzle of the pipe, and

the jet is in like manner diminished. So is it with the

steam-blast in the chimney of the locomotive.

Doubts were, however, expressed whether the greater draught

obtained by the contraction of the blast-pipe was not

counterbalanced in some degree by the negative pressure upon the

piston. Hence a series of experiments was made with pipes of

different diameters, and their efficiency was tested by the amount

of vacuum that was produced in the smoke-box. The degree of

rarefaction was determined by a glass tube fixed to the bottom of

the smoke-box, and descending into a bucket of water, the tube being

open at both ends. As the rarefaction took place, the water

would of course rise in the tube, and the height to which it rose

above the surface of the water in the bucket was made the measure of

the amount of rarefaction. These experiments proved that a

considerable increase of draught was obtained by the contraction of

the orifice; accordingly, the two blast-pipes opening from the

cylinders into either side of the "Rocket" chimney, and turned up

within it, were contracted slightly below the area of the

steam-ports; and before the engine left the factory, the water rose

in the glass tube three inches above the water in the bucket.

The other arrangements of the "Rocket" were briefly these:

the boiler was cylindrical, with flat ends, six feet in length, and

three feet four inches in diameter. The upper half of the

boiler was used as a reservoir for the steam, the lower half being

filled with water. Through the lower part the copper tubes

extended, being open to the fire-box at one end, and to the chimney

at the other. The fire-box, or furnace, two feet wide and

three feet high, was attached immediately behind the boiler, and was

also surrounded with water. The cylinders of the engine were

placed on each side of the boiler, in an oblique position, one end

being nearly level with the top of the boiler at its after end, and

the other pointing toward the centre of the foremost or driving pair

of wheels, with which the connection was directly made from the

piston-rod to a pin on the outside of the wheel. The engine,

together with its load of water, weighed only four tons and a

quarter; and it was supported on four wheels, not coupled. The

tender was four-wheeled, and similar in shape to a wagon—the

foremost part holding the fuel, and the hind part a water-cask.

When the "Rocket" was finished, it was placed upon the

Killingworth Railway for the purpose of experiment. The new

boiler arrangement was found perfectly successful. The steam

was raised rapidly and continuously, and in a quantity which then

appeared marvellous. The same evening Robert dispatched a

letter to his father at Liverpool, informing him, to his great joy,

that the "Rocket" was "all right," and would be in complete working

trim by the day of trial. The engine was shortly after sent by

wagon to Carlisle, and thence shipped for Liverpool.

The time so much longed for by George Stephenson had now

arrived, when the merits of the passenger locomotive were about to

be put to the test. He had fought the battle for it until now

almost single-handed. Engrossed by his daily labours and

anxieties, and harassed by difficulties and discouragements which

would have crushed the spirit of a less resolute man, he had held

firmly to his purpose through good and through evil report.

The hostility which he experienced from some of the directors

opposed to the adoption of the locomotive was the circumstance that

caused him the greatest grief of all; for where he had looked for

encouragement, he found only carping and opposition. But his

pluck never failed him; and now the "Rocket" was upon the ground to

prove, to use his own words, "whether he was a man of his word or

not."

Great interest was felt at Liverpool, as well as throughout

the country, in the approaching competition. Engineers,

scientific men, and mechanics arrived from all quarters to witness

the novel display of mechanical ingenuity on which such great

results depended. The public generally were no indifferent

spectators either. The populations of Liverpool, Manchester,

and the adjacent towns felt that the successful issue of the

experiment would confer upon them individual benefits and local

advantages almost incalculable, while populations at a distance

waited for the result with almost equal interest.

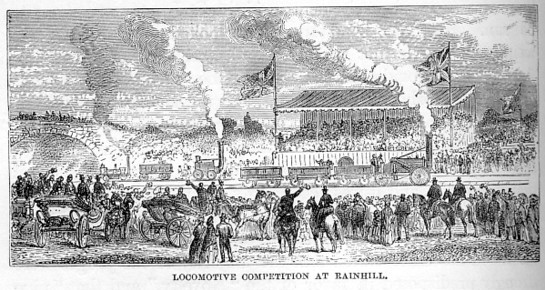

On the day appointed for the great competition of locomotives

at Rainhill the following engines were entered for the prize:

1. Messrs. Braithwaite and Ericsson's "Novelty." [p.322]

2. Mr. Timothy Hackworth's "Sanspareil."

3. Messrs. R. Stephenson and Co.'s "Rocket."

4. Mr. Burstall's "Perseverance."

Another engine was entered by Mr. Brandreth, of Liverpool—the

"Cycloped," weighing three tons, worked by a horse in a frame, but

it could not be admitted to the competition. The above were

the only four exhibited, out of a considerable number of engines

constructed in different parts of the country in anticipation of

this contest, many of which could not be satisfactorily completed by

the day of trial.

The ground on which the engines were to be tried was a level

piece of railroad, about two miles in length. Each was

required to make twenty trips, or equal to a journey of seventy

miles, in the course of the day, and the average rate of travelling

was to be not under ten miles an hour. It was determined that,

to avoid confusion, each engine should be tried separately, and on

different days.

The day fixed for the competition was the 1st of October,

but, to allow sufficient time to get the locomotives into good

working order, the directors extended it to the 6th. On the

morning of the 6th the ground at Rainhill presented a lively

appearance, and there was as much excitement as if the St. Leger

were about to be run. Many thousand spectators looked on,

among whom were some of the first engineers and mechanicians of the

day. A stand was provided for the ladies; the "beauty and

fashion" of the neighbourhood were present, and the side of the

railroad was lined with carriages of all descriptions.

It was quite characteristic of the Stephensons that, although

their engine did not stand first on the list for trial, it was the

first that was ready, and it was accordingly ordered out by the

judges for an experimental trip. Yet the "Rocket" was by no

means the "favourite" with either the judges or the spectators.

Nicholas Wood has since stated that the majority of the judges were

strongly predisposed in favour of the "Novelty," and that "nine

tenths, if not ten tenths, of the persons present were against the

'Rocket' because of its appearance." [p.323]

Nearly every person favoured some other engine, so that there was

nothing for the "Rocket" but the practical test. The first

trip made by it was quite successful. It ran about twelve

miles, without interruption, in about fifty-three minutes.

The "Novelty" was next called out. It was a light

engine, very compact in appearance, carrying the water and fuel upon

the same wheels as the engine. The weight of the whole was

only three tons and one hundred weight. A peculiarity of this

engine was that the air was driven or forced through the fire

by means of bellows. The day being now far advanced, and some

dispute having arisen as to the method of assigning the proper load

for the "Novelty," no particular experiment was made farther than

that the engine traversed the line by way of exhibition,

occasionally moving at the rate of twenty-four miles an hour.

The "Sanspareil," constructed by Mr. Timothy Hackworth, was next

exhibited, but no particular experiment was made with it on this

day. This engine differed but little in its construction from

the locomotive last supplied by the Stephensons to the Stockton and

Darlington Railway, of which Mr. Hackworth was the locomotive

foreman.

The contest was postponed until the following day; but,

before the judges arrived on the ground, the bellows for creating

the blast in the "Novelty" gave way, and it was found incapable of

going through its performance. A defect was also detected in

the boiler of the "Sanspareil," and some farther time was allowed to

get it repaired. The large number of spectators who had

assembled to witness the contest were greatly disappointed at this

postponement; but, to lessen it, Stephenson again brought out the

"Rocket," and, attaching to it a coach containing thirty persons, he

ran them along the line at the rate of from twenty-four to thirty

miles an hour, much to their gratification and amazement.

Before separating, the judges ordered the engine to be in readiness

by eight o'clock on the following morning, to go through its

definitive trial according to the prescribed conditions.

On the morning of the 8th of October the "Rocket" was again

ready for the contest. The engine was taken to the extremity

of the stage, the fire-box was filled with coke, the fire lighted,

and the steam raised until it lifted the safety-valve loaded to a

pressure of fifty pounds to the square inch. This proceeding

occupied fifty-seven minutes. The engine then started on its

journey, dragging after it about thirteen tons' weight in wagons,

and made the first ten trips backward and forward along the two

miles of road, running the thirty-five miles, including stoppages,

in an hour and forty-eight minutes. The second ten trips were

in like manner performed in two hours and three minutes. The

maximum velocity attained during the trial trip was twenty-nine

miles an hour, or about three times the speed that one of the judges

of the competition had declared to be the limit of possibility.

The average speed at which the whole of the journeys were performed

was fifteen miles an hour, or five miles beyond the rate specified

in the conditions published by the company. The entire

performance excited the greatest astonishment among the assembled

spectators; the directors felt confident that their enterprise was

now on the eve of success; and George Stephenson rejoiced to think

that, in spite of all false prophets and fickle counsellors, the

locomotive system was now safe. When the "Rocket," having

performed all the conditions of the contest, arrived at the "grand

stand" at the close of its day's successful run, Mr. Cropper—one of

the directors favourable to the fixed engine system—lifted up his

hands, and exclaimed, "Now has George Stephenson at last delivered

himself."

Messrs. Braithwaite and Ericsson's "Novelty."

Neither the "Novelty" nor the "Sanspareil" was ready for

trial until the 10th, on the morning of which day an advertisement

appeared, stating that the former engine was to be tried on that

day, when it would perform more work than any engine on the ground.

The weight of the carriages attached to it was only about seven

tons. The engine passed the first post in good style; but, in

returning, the pipe from the forcing-pump burst and put an end to

the trial. The pipe was afterward repaired, and the engine

made several trips by itself, in which it was said to have gone at

the rate of from twenty-four to twenty-eight miles an hour.

Timothy Hackworth's "Sans Pareil."

The "Sanspareil" was not ready until the 13th; and when its

boiler and tender were filled with water, it was found to weigh four

hundred weight beyond the weight specified in the published

conditions as the limit of four-wheeled engines; nevertheless, the

judges allowed it to run on the same footing as the other engines,

to enable them to ascertain whether its merits entitled it to

favourable consideration. It travelled at the average speed of

about fourteen miles an hour, with its load attached; but at the

eighth trip the cold-water pump got wrong, and the engine could

proceed no farther.

It was determined to award the premium to the successful

engine on the following day, the 14th, on which occasion there was

an unusual assemblage of spectators. The owners of the

"Novelty" pleaded for another trial, and it was conceded. But

again it broke down. Then Mr. Hackworth requested the

opportunity for making another trial of his "Sanspareil." But

the judges had now had enough of failures, and they declined, on the

ground that not only was the engine above the stipulated weight, but

that it was constructed on a plan which they could not recommend for

adoption by the directors of the company. One of the principal

practical objections to this locomotive was the enormous quantity of

coke consumed or wasted by it—about 692 lbs. per hour when

travelling—caused by the sharpness of the steam-blast in the

chimney, which blew a large proportion of the burning coke into the

air.

Timothy Burstall's "Perseverance."

The "Perseverance" of Mr. Burstall was found unable to move

at more than five or six miles an hour, and it was withdrawn from

the contest at an early period. The "Rocket" was thus the only

engine that had performed, and more than performed, all the

stipulated conditions, and it was declared to be entitled to the

prize of £500, which was awarded to the Messrs. Stephenson and Booth

accordingly. And farther to show that the engine had been

working quite within its powers, George Stephenson ordered it to be

brought upon the ground and detached from all incumbrances, when, in

making two trips, it was found to travel at the astonishing rate of

thirty-five miles an hour.

The "Rocket" had thus eclipsed the performances of all

locomotive engines that had yet been constructed, and outstripped

even the sanguine expectations of its constructors. It

satisfactorily answered the report of Messrs. Walker and Rastrick,

and established the efficiency of the locomotive for working the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and, indeed, all future railways.

The "Rocket" showed that a new power had been born into the world,

full of activity and strength, with boundless capability of work.

It was the simple but admirable contrivance of the steam-blast, and

its combination with the multitubular boiler, that at once gave

locomotion a vigorous life, and secured the triumph of the railway

system. [p.327] As has

been well observed, this wonderful ability to increase and multiply

its powers of performance with the emergency that demands them has

made this giant engine the noblest creation of human wit, the very

lion among machines. The success of the Rainhill experiment,

as judged by the public, may be inferred from the fact that the

shares of the company immediately rose ten per cent., and nothing

farther was heard of the proposed twenty-one fixed engines,

engine-houses, ropes, etc. All this cumbersome apparatus was

thenceforward effectually disposed of.

Very different now was the tone of those directors who had

distinguished themselves by the persistency of their opposition to

George Stephenson's plans. Coolness gave way to eulogy, and

hostility to unbounded offers of friendship, after the manner of

many men who run to the help of the strong. Deeply though the

engineer had felt aggrieved by the conduct exhibited toward him

during this eventful struggle by some from whom forbearance was to

have been expected, he never entertained toward them in after life

any angry feelings; on the contrary, he forgave all. But,

though the directors afterward passed unanimous resolutions

eulogizing "the great skill and unwearied energy" of their engineer,

he himself, when speaking confidentially to those with whom he was

most intimate, could not help pointing out the difference between

his "foul-weather and fair-weather friends." Mr. Gooch says

that, though naturally most cheerful and kind-hearted in

disposition, the anxiety and pressure which weighed upon his mind

during the construction of the railway had the effect of making him

occasionally impatient and irritable, like a spirited horse touched

by the spur, though his original good nature from time to time shone

through it all. When the line had been brought to a successful

completion, a very marked change in him became visible. The

irritability passed away, and when difficulties and vexations arose

they were treated by him as matters of course, and with perfect

composure and cheerfulness. |

――――♦――――

|

CHAPTER XIII.

OPENING OF THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAY, AND EXTENSION OF

THE RAILWAY SYSTEM.

THE

directors of the railway now began to see daylight, and they derived

encouragement from the skilful manner in which their engineer had

overcome the principal difficulties of the undertaking. He had

formed a solid road over Chat Moss, and thus achieved one

"impossibility;" and he had constructed a locomotive that could run

at a speed of thirty miles an hour, thus vanquishing a still more

formidable difficulty.

A single line of way was completed over Chat Moss by the 1st

of January, 1830, and on that day the "Rocket," with a carriage full

of directors, engineers, and their friends, passed along the greater

part of the road between Liverpool and Manchester. Mr.

Stephenson continued to direct his close attention to the

improvement of the details of the locomotive, every successive trial

of which proved more satisfactory. In this department he had

the benefit of the able and unremitting assistance of his son, who,

in the workshops at Newcastle, directly superintended the

construction of the engines required for the public working of the

railway. He did not by any means rest satisfied with the

success, decided though it was, which had been achieved by the

"Rocket." He regarded it but in the light of a successful

experiment; and every successive engine placed upon the railway

exhibited some improvement on its predecessors. The

arrangement of the parts, and the weight and proportion of the

engines, were altered as the experience of each successive day, or

week, or month suggested; and it was soon found that the

performances of the "Rocket" on the day of trial had been greatly

within the powers of the improved locomotive.

The first entire trip between Liverpool and Manchester was

performed on the 14th of June, 1830, on the occasion of a board

meeting being held at the latter town. The train was on this

occasion drawn by the "Arrow," one of the new locomotives, which the

most recent improvements had been adopted. George Stephenson

himself drove the engine, and Captain Scoresby, the circumpolar

navigator, stood beside him on the footplate, and minuted the speed

of the train. A great concourse of people assembled at both

termini, as well as along the line, to witness the novel spectacle

of a train of carriages drawn by an engine at the speed of seventeen

miles an hour. On the return journey to Liverpool in the

evening, the "Arrow" crossed Chat Moss at a speed of nearly

twenty-seven miles an hour, reaching its destination in about an

hour and a half.

In the meantime Mr. Stephenson and his assistant, Mr. Gooch,

were diligently occupied in making the necessary preliminary

arrangements for the conduct of the traffic against the time when

the line should be ready for opening. The experiments made

with the object of carrying on the passenger traffic at quick

velocities were of an especially harassing and anxious character.

Every week, for nearly three months before the opening, trial trips

were made to Newton and back, generally with two or three trains

following each other, and carrying altogether from two to three

hundred persons. These trips were usually made on Saturday

afternoons, when the works could be more conveniently stopped and

the line cleared for the occasion. In these experiments Mr.

Stephenson had the able assistance of Mr. Henry Booth, the secretary

of the company, who contrived many of the arrangements in the

passenger carriages, not the least valuable of which was his

invention of the coupling screw, still in use on all passenger

railways.

At length the line was finished and ready for the public

opening, which took place on the 15th of September, 1830, and

attracted a vast number of spectators from all parts of the country.

The completion of the railway was justly regarded as an important

national event, and the ceremony of its opening was celebrated

accordingly. The Duke of Wellington, then prime minister, Sir

Robert Peel, Secretary of State, Mr. Huskisson, one of the members

for Liverpool and an earnest supporter of the project from its

commencement, were among the number of distinguished public

personages present.

Inaugural journey of the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway.

Painting by A.B. Clayton, 1830.

Eight locomotive engines, constructed at the Stephenson

works, had been delivered and placed upon the line, the whole of

which had been tried and tested, weeks before, with perfect success.

The several trains of carriages accommodated in all about six

hundred persons. The "Northumbrian" engine, driven by George

Stephenson himself, headed the line of trains; then followed the

"Phoenix," driven by Robert Stephenson; the "North Star," by Robert

Stephenson senior (brother of George); the "Rocket," by Joseph

Locke; the "Dart," by Thomas L. Gooch; the "Comet," by William

Allcard; the "Arrow," by Frederick Swanwick; and the "Meteor," by

Anthony Harding. The procession was cheered in its progress by

thousands of spectators—through the deep ravine of Olive Mount; up

the Sutton incline; over the great Sankey viaduct, beneath which a

multitude of persons had assembled—carriages filling the narrow

lanes, and barges crowding the river; the people below gazing with

wonder and admiration at the trains which sped along the line, far

above their heads, at the rate of some twenty-four miles an hour.

At Parkside, about seventeen miles from Liverpool, the

engines stopped to take in water. Here a deplorable accident

occurred to one of the illustrious visitors, which threw a deep

shadow over the subsequent proceedings of the day. The

"Northumbrian" engine, with the carriage containing the Duke of

Wellington, was drawn up on one line, in order that the whole of the

trains on the other line might pass in review before him and his

party. Mr. Huskisson had alighted from the carriage, and was

standing on the opposite road, along which the "Rocket" was observed

rapidly coming up. At this moment the Duke of Wellington,

between whom and Mr. Huskisson some coolness had existed, made a

sign of recognition, and held out his hand. A hurried but

friendly grasp was given; and before it was loosened there was a

general cry from the bystanders of "Get in, get in!" Flurried

and confused, Mr. Huskisson endeavoured to get round the open door

of the carriage, which projected over the opposite rail, but in so

doing he was struck down by the " Rocket," and falling with his leg

doubled across the rail, the limb was instantly crushed. His

first words, on being raised, were, "I have met my death," which

unhappily proved true, for he expired that same evening in the

Parsonage of Eccles. It was cited at the time as a remarkable

fact that the "Northumbrian" engine, driven by George Stephenson

himself, conveyed the wounded body of the unfortunate gentleman a

distance of about fifteen miles in twenty-five minutes or at the

rate of thirty-six miles an hour. This incredible speed burst

upon the world with the effect of a new and unlooked-for phenomenon.

The accident threw a gloom over the rest of the day's

proceedings. The Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel

expressed a wish that the procession should return to Liverpool.

It was, however, represented to them that a vast concourse of people

had assembled at Manchester to witness the arrival of the trains;

that report would exaggerate the mischief if they did not complete

the journey; and that a false panic on that day might seriously

affect future railway travelling and the value of the company's

property. The party consented accordingly to proceed to

Manchester, but on the understanding that they should return as soon

as possible, and refrain from farther festivity.

As the trains approached Manchester, crowds of people were

found covering the banks, the slopes of the cuttings, and even the

railway itself. The multitude, become impatient and excited by

the rumours which reached them, had outflanked the military, and all

order was at an end. The people clambered about the carriages,

holding on by the door-handles, and many were tumbled over; but,

happily, no fatal accident occurred. At the Manchester station

the political element began to display itself; placards about

"Peterloo," etc., were exhibited, and brickbats were thrown at the

carriage containing the duke. On the trains coming to a stand

in the Manchester station, the duke did not descend, but remained

seated, shaking hands with the women and children who were pushed

forward by the crowd. Shortly after, the trains returned to

Liverpool, which they reached, after considerable delays, late at

night.

On the following morning the railway was opened for public

traffic. The first train of 140 passengers was booked and sent

on to Manchester, reaching it in the allotted time of two hours; and

from that time the traffic has regularly proceeded from day to day

until now.

It is scarcely necessary that we should speak at any length

of the commercial results of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Suffice it to say that its success was complete and decisive.

The anticipations of its projectors were, however, in many respects

at fault. They had based their calculations almost entirely on

the heavy merchandise traffic—such as coal, cotton, and

timber—relying little upon passengers; whereas the receipts derived

from the conveyance of passengers far exceeded those derived from

merchandise of all kinds, which for a time continued a subordinate

branch of the traffic. In the evidence given before the

Committee of the House of Commons, the promoters stated their

expectation of obtaining about one half of the whole number of

passengers which the coaches then running could carry, or about 400

a day. But the railway was scarcely opened before it carried

on an average about 1200 passengers daily; and five years after the

opening, it carried nearly half a million of persons yearly.

So successful, indeed, was the passenger traffic, that it engrossed

the whole of the company's small stock of engines.

For some time after the public opening of the line, Mr.

Stephenson's ingenuity continued to be employed in devising improved

methods for securing the safety and comfort of the travelling

public. Few are aware of the thousand minute details which

have to be arranged—the forethought and contrivance that have to be

exercised—to enable the traveller by railway to accomplish his

journey in safety. After the difficulties of constructing a

level road over bogs, across valleys, and through deep cuttings have

been overcome, the maintenance of the way has to be provided for

with continuous care. Every rail, with its fastenings, must be

complete, to prevent risk of accident, and the road must be kept

regularly ballasted up to the level to diminish the jolting of

vehicles passing over it at high speeds. Then the stations

must be protected by signals observable from such a distance as to

enable the train to be stopped in event of an obstacle, such as a

stopping or shunting train being in the way. For some years

the signals employed on the Liverpool Railway were entirely given by

men with flags of different colours stationed along the line; there

were no fixed signals nor electric telegraphs; but the traffic was

nevertheless worked quite as safely as under the more elaborate and

complicated system of telegraphing which has since been established.

From an early period it became obvious that the iron road, as

originally laid down, was quite insufficient for the heavy traffic

which it had to carry. The line was in the first place laid

with fish-bellied rails of only thirty-five pounds to the yard,

calculated only for horse-traffic, or, at most, for engines like the

" Rocket" of very light weight. But as the power and the

weight of the locomotives were increased, it was found that such

rails were quite insufficient for the safe conduct of the traffic,

and it therefore became necessary to relay the road with heavier and

stronger rails at considerable expense.

Replica Liverpool & Manchester Railway coach,

National Railway Museum, York.

The details of the carrying stock had in like manner to be

settled by experience. Everything had, as it were, to be begun

from the beginning. The coal-wagon, it is true, served in some

degree as a model for the railway-truck; but the railway

passenger-carriage was an entirely novel structure. It had to

be mounted upon strong framing, of a peculiar kind, supported on

springs to prevent jolting. Then there was the necessity for

contriving some method of preventing hard bumping of the

carriage-ends when the train was pulled up, and hence the

contrivance of buffer-springs and spring-frames. For the

purpose of stopping the train, brakes on an improved plan were also

contrived, with new modes of lubricating the carriage-axles, on

which the wheels revolved at an unusually high velocity. In

all these contrivances Mr. Stephenson's inventiveness was kept

constantly on the stretch; and though many improvements in detail

have been effected since his time, the foundations were then laid by

him of the present system of conducting railway traffic. As a

curious illustration of the inventive ingenuity which he displayed

in contriving the working of the Liverpool line, we may mention his

invention of the Self-acting Brake. He early entertained the

idea that the momentum of the running train might itself be made

available for the purpose of checking its speed. He proposed

to fit each carriage with a brake which should be called into action

immediately on the locomotive at the head of the train being pulled

up. The impetus of the carriages carrying them forward, the

buffer-springs would be driven home, and, at the same time, by a

simple arrangement of the mechanism, the brakes would be called into

simultaneous action; thus the wheels would be brought into a state

of sledge, and the train speedily stopped. This plan was

adopted by Mr. Stephenson before he left the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway, though it was afterward discontinued; and it is

a remarkable fact, that this identical plan, with the addition of a

centrifugal apparatus, was recently revived by M. Guerin, a French

engineer, and extensively employed on foreign railways.

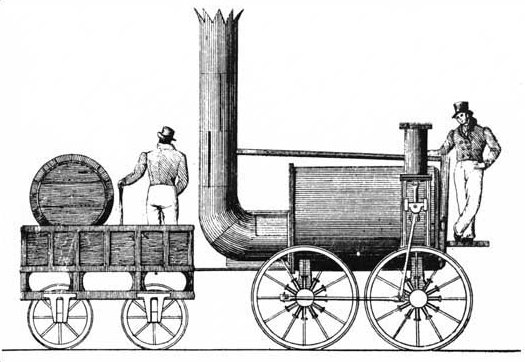

Planet-type locomotive, Liverpool & Manchester

Railway.

Engraving by William Miller, 1832.

Finally, Mr. Stephenson had to attend to the improvement of

the power and speed of the locomotive—always the grand object of his

study—with a view to economy as well as regularity in the working of

the railway. In the "Planet" engine, delivered upon the line

immediately subsequent to the public opening, all the improvements

which had up to this time been contrived by him and his son were

introduced in combination—the blast-pipe, the tubular boiler,

horizontal cylinders inside the smoke-box, the cranked axle, and the

fire-box firmly fixed to the boiler. The first load of goods

conveyed from Liverpool to Manchester by the "Planet" was eighty

tons in weight, and the engine performed the journey against a

strong head wind in two hours and a half. On another occasion,

the same engine brought up a cargo of voters from Manchester to

Liverpool, during a contested election, within a space of sixty

minutes. The "Samson," delivered in the following year,

exhibited still farther improvements, the most important of which

was that of coupling the fore and hind wheels of the engine.

By this means the adhesion of the wheels on the rails was more

effectually secured, and thus the full hauling power of the

locomotive was made available. The "Samson," shortly after it

was placed upon the line, dragged after it a train of wagons

weighing a hundred and fifty tons at a speed of about twenty miles

an hour, the consumption of coke being reduced to only about a third

of a pound per ton per mile.

The rapid progress thus made will show that the inventive

faculties of Mr. Stephenson and his son were kept fully on the

stretch; but their labours were amply repaid by the result.

They were, doubtless, to some extent stimulated by the number of

competitors who about the same time appeared as improvers of the

locomotive engine. But the superiority of Stephenson's

locomotives over all others that had yet been tried induced the

directors of the railway to require that the engines supplied to