|

EARLY INVENTORS IN LOCOMOTION.

――――♦――――

RICHARD TREVITHICK C.E.

(1771-1833)

INVENTOR, AND BUILDER OF THE FIRST

WORKING STEAM RAILWAY LOCOMOTIVE.

"He was full of speculative enthusiasm, a great

theorist, and yet

an indefatigable experimenter."

CHAPTER I.

SCHEMERS AND PROJECTORS.

IT

is easy to understand how rapid transit from place to place should,

from the earliest times, have been an object of desire. The

marvellous gift of speed conferred by Fortunatus's Wishing Cap was

what all must have envied: it conferred power. It also

conferred pleasure. "Life has not many things better than

this," said Samuel Johnson as he rolled along in the post-chaise.

But it also conferred comfort and well-being; and hence the easy and

rapid transit of persons and commodities became in all countries an

object of desire in proportion to their growth in civilization.

We have elsewhere [p.47]

endeavoured to describe the obstructions to the progress of society

occasioned by the defective internal communications of Britain in

early times, which were to a considerable extent removed by the

adoption of the canal system, and the improvement of our roads and

highways, toward the end of last century. But the progress of

industry was so rapid—the invention of new tools, machines, and

engines so greatly increased the productive wealth of the

nation—that some forty years since it was found that these roads and

canals, numerous and excellent though they might be, were altogether

inadequate for the accommodation of the traffic of the country,

which was increasing in almost a direct ratio with the increased

application of steam-power to the purposes of productive industry.

The inventive minds of the nation, always on the alert—the

"schemers" and the "projectors," to whom society has in all times

been so greatly indebted—proceeded to apply themselves to the

solution of the problem of how the communications of the country

were best to be improved; and the result was, that the power of

steam itself was applied to remedy the inconveniences which it had

caused.

Like most inventions, that of the Steam Locomotive was very

gradually made. The idea of it, born in one age, was revived

in the ages that followed. It was embodied first in one model,

then in another—the labours of one inventor being taken up by his

successors—until at length, after many disappointments and many

failures, the practicable working locomotive was achieved.

The locomotive engine was not, however, sufficient for the

purposes of cheap and rapid transit. Another expedient was

absolutely essential to its success—that of the Railway: the smooth

rail to bear the load, as well as the steam-engine to draw it.

Expedients were early adopted for the purpose of diminishing

friction between the wheels of vehicles and the roads along which

they were dragged by horse-power. The Romans employed stone

blocks with that object; and the streets of the long-buried city of

Pompeii still bear the marks of the ancient Roman chariot-wheels, as

the stone track for heavy vehicles on our modem London Bridge shows

the wheel-marks of the wagons which cross it. These stone

blocks were merely a simple expedient to diminish friction, and were

the first steps toward a railroad.

The railway proper doubtless originated in the coal districts

of the North of England and Wales, where it was found useful in

facilitating the transport of coals from the pits to the

shipping-places. At an early period the coal was carried to

the boats in panniers, or in sacks upon horses' backs. Next

carts were used, and tram-ways of flag-stone were laid down, along

which they were easily hauled. The carts were then converted

into wagons, and mounted on four wheels instead of two.

Still farther to facilitate the haulage of the wagons, pieces

of planking were laid parallel upon wooden sleepers, or imbedded in

the ordinary track. It is said that these wooden rails were

first employed by a Mr. Beaumont, a gentleman from the South, who,

about the year 1630, adventured in the northern mines with about

thirty thousand pounds, and after introducing many improvements in

the working of the coal, as well as in the methods of transporting

it to the staithes on the river, was ruined by his enterprise, and

"within a few Years," to use the words of the ancient chronicler,

"he consumed all his Money, and rode Home upon his light Horse." [p.49-1]

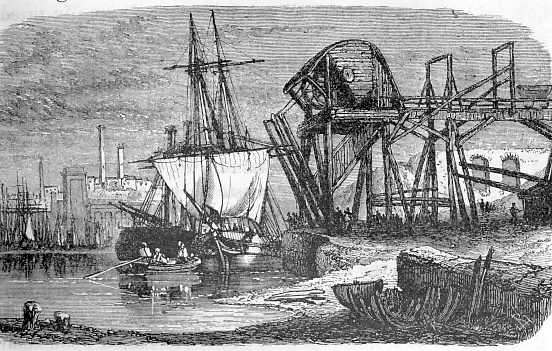

COAL-STAITH ON THE TYNE [By R. P. Leitch.]

The use of wooden rails gradually extended, and they were

laid down between most of the collieries on the Tyne and the places

at which the coal was shipped. Roger North, in 1676, found the

practice had become extensively adopted, and he speaks of the large

sums then paid for way-leave—that is, the permission granted by the

owners of lands lying between the coal-pits and the river-side to

lay down a tram-way for the purpose of connecting the one with the

other.

A century later, Arthur Young observed that not only had

these roads become greatly multiplied, but formidable works had been

constructed to carry them along upon the same level. "The coal

wagon-roads from the pits to the water," he says, "are great works,

carried over all sorts of inequalities of ground, so far as the

distance of nine or ten miles. The tracks of the wheels are

marked with pieces of wood let into the road for the wheels of the

wagons to run on, by which one horse is enabled to draw, and that

with ease, fifty or sixty bushels of coals." [p49-2]

Saint Fond, the French traveller, who visited Newcastle in

1791, described the colliery wagon-ways in that neighbourhood as

superior to any thing of the kind he had seen. The wooden

rails were formed with a rounded upper surface, like a projecting

moulding, and the wagon-wheels being "made of cast iron, and

hollowed in the manner of a metal pulley," readily fitted the

rounded surface of the rails. The economy with which the coal

was thus hauled to the shipping-places was urged by Saint Font as an

inducement to his own countrymen to adopt a like method of transit.

[p50]

Similar wagon-roads were early laid down in the coal

districts of Wales, Cumberland, and Scotland. At the time of

the Scotch rebellion in 1745, a tram-road existed between the

Tranent coal-pits and the small harbour of Cockenzie, in East

Lothian; and a portion of the line was selected by General Cope as a

position for his cannon at the battle of Prestonpans.

In these rude wooden tracks we find the germ of the modern

railroad. Improvements were gradually made in them.

Thus, at some collieries, thin plates of iron were nailed upon their

upper surface, for the purpose of protecting the parts most exposed

to friction. Cast-iron rails were also tried, the wooden rails

having been found liable to rot. The first iron rails are

supposed to have been laid down at Whitehaven as early as 1738.

This cast-iron road was denominated a "plate-way," from the

plate-like form in which the rails were cast. In 1767, as

appears from the books of the Coalbrookdale Iron Works, in

Shropshire, five or six tons of rails were cast, as an experiment,

on the suggestion of Mr. Reynolds, one of the partners; and they

were shortly after laid down to form a road.

In 1776, a cast-iron tram-way, nailed to wooden sleepers, was laid

down at the Duke of Norfolk's colliery near Sheffield. The

person who designed and constructed this coal line was Mr. John

Curr, whose son has erroneously claimed for him the invention of the

cast-iron railway. He certainly adopted it early, and thereby

met the fate of men before their age; for his plan was opposed by

the labouring people of the colliery, who got up a riot, in which

they tore up the road and burned the coal-staith, while Mr. Curr

fled into a neighbouring wood for concealment, and lay there

perdu for three days and nights, to escape the fury of the

populace. [p.51] The

plates of these early tram-ways had a ledge cast on their outer edge

to guide the wheel along the road, after the manner shown in the

preceding cut.

In 1789, Mr. William Jessop constructed a railway at

Loughborough, in Leicestershire, and there introduced the cast-iron

edge-rail, with flanches cast upon the tire of the wagon-wheels to

keep them on the track, instead of having the margin or flanch cast

upon the rail itself; and this plan was shortly after adopted in

other places. In 1800, Mr. Benjamin Outram, of Little Eaton,

Derbyshire (father of the distinguished General Outram), used stone

props instead of timber for supporting the ends or joinings of the

rails. Thus the use of railroads, in various forms, gradually

extended, until they became generally adopted in the mining

districts.

Such was the growth of the railroad, which, it will be

observed, originated in necessity, and was modified according to

experience; progress in this, as in all departments of mechanics,

having been effected by the exertions of many men; one generation

entering upon the labours of that which preceded it, and carrying

them onward to farther stages of improvement. The invention of

the locomotive was in like manner made by successive steps. It

was not the invention of one man, but of a succession of men, each

working at the proper hour, and according to the needs of that hour;

one inventor interpreting only the first word of the problem which

his successors were to solve after long and laborious efforts and

experiments. "The locomotive is not the invention of one man," said

Robert Stephenson at Newcastle, "but of a nation of mechanical

engineers."

Down to the end of last century, and indeed down almost to

our own time, the only power used in haulage was that of the horse.

Along the common roads of the country the poor horses were "tearing

their hearts out" in dragging cumbersome vehicles behind them, and

the transport of merchandise continued to be slow, dear, and in all

respects unsatisfactory. Many expedients were suggested with

the view of getting rid of the horse. The power of wind was

one of the first expedients proposed. It was cheap, though by

no means regular. It impelled ships by sea; why should it not

be used to impel carriages by land? The first sailing-coach

was invented by one Simon Stevinius, or Stevins, a Fleming, toward

the end of the sixteenth century. Pierre Gassendi gives an

account of its performances as follows:

"Purposing to visit Grotius,

Peireskius went to Scheveling that he might satisfy himself of the

carriage and swiftness of a coach a few years before invented, and

made with that artifice that with expanded sails it would fly upon

the shore as a ship upon the sea. He had formerly heard that

Count Maurice, a little after his victory at Nieuport [1600], had

put himself thereinto, together with Francis Mendoza, his prisoner,

on purpose to make trial thereof, and that, within two hours, they

arrived at Putten, which is distant from Scheveling fourteen

leagues, or two-and-forty miles. He had, therefore, a mind to

make the experiment himself, and he would often tell us with what

admiration he was seized when he was carried with a quick wind and

yet perceived it not, the coach's motion being equally quick."[p52-1]

The sailing-coach, however, was only a curiosity. As a

practicable machine, it proved worthless, for the wind could not be

depended upon for land locomotion. The coach could not tack as

the ship did. Sometimes the wind did not blow at all, while at

other times it blew a hurricane. After being used for some

time as a toy, the sailing-coach was given up as impracticable, and

the project speedily dropped out of sight.

But, strange to say, the expedient of driving coal-wagons by

the wind was revived in Wales about a century later. On this

occasion, Sir Humphry Mackworth, an ingenious coal-miner at Neath,

was the projector. Waller, in his "Essay on Mines," published

in 1698, takes the opportunity of eulogizing Sir Humphry's "new

sailing-wagons, for the cheap carriage of his coal to the

water-side, whereby one horse does the work of ten at all times; but

when any wind is stirring (which is seldom wanting near the sea),

one man and a small sail do the work of twenty."[p52-2]

It does not, however, appear that any other coal-owner had the

courage to follow Sir Humphry's example, and the sailing-wagon was

forgotten until, after the lapse of another century, it was revived

by Mr. Edgeworth.

The employment of steam-power as a means of land locomotion

was the subject of much curious speculation long before any

practical attempt was made to carry it into effect. The merit

of promulgating the first idea with reference to it probably belongs

to no other than the great Sir Isaac Newton. In his

"Explanation of the Newtonian Philosophy," written in 1680, he

figured a spherical generator, supported on wheels, and provided

with a seat for a passenger in front, and a long jet-pipe behind,

and stated that "the whole is to be mounted on little wheels, so as

to move easily on a horizontal plane, and if the hole, or jet-pipe,

be opened, the vapour will rush out violently one way, and the

wheels and the ball at the same time will be carried the contrary

way.'' This, it will be observed, was but a modification of

the earliest known steam-engine, or Œolopile, of Hero of Alexandria.

It is not believed that Sir Isaac Newton ever made any experiment of

his proposed method of locomotion, or did more than merely throw out

the idea for other minds to work upon.

The idea of employing steam in locomotion was revived from

time to time, and formed the subject of much curious speculation.

About the middle of last century we find Benjamin Franklin, then

agent in London for the United Provinces of America, Matthew

Boulton, of Birmingham, and Erasmus Darwin, of Lichfield, engaged in

a correspondence relative to steam as a motive power. Boulton

had made a model of a fire-engine, which he sent to London for

Franklin's inspection; and though the original purpose for which the

engine had been contrived was the pumping of water, it was believed

to be practicable to employ it also as a means of locomotion.

Franklin was too much occupied at the time by grave political

questions to pursue the subject; but the sanguine and speculative

mind of Erasmus Darwin was inflamed by the idea of a "fiery

chariot," and he pressed his friend Boulton to prosecute the

contrivance of the necessary steam machine.[p.54]

Erasmus Darwin was in many respects a remarkable man.

In his own neighbourhood he was highly esteemed as a physician, and

by many intelligent readers of his day he was greatly prized as a

poet. Horace Walpole said of his "Botanic Garden" that it was

"the most delicious poem upon earth," and he declared that he "could

read it over and over again forever." The doctor was

accustomed to write his poems with a pencil on little scraps of

paper while riding about among his patients in his "sulky."

The vehicle, which was worn and bespattered outside, had room within

it for the doctor and his appurtenances only. On one side of

him was a pile of books reaching from the floor to nearly the front

window of the carriage, while on the other was a hamper containing

fruit and sweetmeats, with a store of cream and sugar, with which

the occupant regaled himself during his journey. Lashed on to

the place usually appropriated to the "boot" was a large pail for

watering the horses, together with a bag of oats and a bundle of

hay. Such was the equipage of a fashionable country physician

of the last century.

Dr. Darwin was a man of large and massive person, bearing a

rather striking resemblance to his distinguished townsman, Dr.

Johnson, in manner, deportment, and force of character. He was

full of anecdote, and his conversation was most original and

entertaining. He was a very outspoken man, vehemently

enunciating theories which some thought original and others

dangerous. As he drove through the country in his "sulky," his

mind teemed with speculation on all subjects, from zoonomy, botany,

and physiology, to physics, æsthetics, and mental philosophy.

Though his speculations were not always sound, they were clever and

ingenious, and, at all events, they had the effect of setting other

minds a-thinking and speculating on science and the methods for its

advancement. From his "Loves of the Plants"—afterward so

cleverly parodied by George Canning in his "Loves of the

Triangles"—it would appear that the doctor even entertained a theory

of managing the winds by a little philosophic artifice. His

scheme of a steam locomotive was of a more practical character.

This idea, like so many others, first occurred to him in his

"sulky."

"As I was riding home yesterday," he wrote to his friend

Boulton in the year 1766,

"I considered the scheme of the fiery chariot, and

the longer I contemplated this favourite idea, the more practicable

it appeared to me. I shall lay my thoughts before you, crude

and undigested though they may appear to be, telling you as well

what I thought would not do as what would do, as by those hints you

may be led into various trains of thinking upon this subject, and by

that means (if any hints can assist your genius, which, without

hints, is above all others I am acquainted with) be more likely to

improve or disapprove. And as I am quite mad of this scheme, I

beg you will not mention it, or show this paper to Wyat or any body.

"These things are required: 1st, a rotary motion; 2d, easily

altering its direction to any other direction; 3d, to be

accelerated, retarded, destroyed, revived instantly and easily; 4th,

the bulk, the weight, and expense of the machine to be as small as

possible in proportion to its use." [p.55]

He then goes on to throw out various suggestions as to the

form and arrangement of the machine, the number of wheels on which

it was to run, and the mode of applying the power. The text of

this letter is illustrated by rough diagrams, showing a vehicle

mounted on three wheels, the foremost or guiding wheel being under

the control of the driver; but in a subsequent passage he says, "I

think four wheels will be better."

"Let there be two cylinders," he

proceeds. "Suppose one piston up, and the vacuum made under it

by the je d'eau froid. That piston can not yet descend

because the cock is not yet opened which admits the steam into its

antagonist cylinder. Hence the two pistons are in equilibrio,

being either of them pressed by the atmosphere. Then I say, if

the cock which admits the steam into the antagonist cylinder be

opened gradually and not with a jerk, that the first-mentioned

[piston in the] cylinder will descend gradually and not less

forcibly. Hence, by the management of the steam cocks, the

motion may be accelerated, retarded, destroyed, revived instantly

and easily. And if this answers in practice as it does in

theory, the machine can not fail of success! Eureka!

"The cocks of the cold water may be moved by the great work,

but the steam cocks must be managed by the hand of the charioteer,

who also directs the rudder-wheel. [Then follow his rough

diagrams.] The central wheel ought to have been under the

rollers, so as it may be out of the way of the boiler." [p.56-1]

After farther explaining himself, he goes on to say:

"If you could learn the expense of

coals to a common fire-engine and the weight of water it draws, some

certain estimate may be made if such a scheme as this would answer.

Pray don't show Wyat this scheme, for if you think it feasible and

will send me a critique upon it, I will certainly, if I can get

somebody to bear half the expense with me, endeavour to build a

fiery chariot, and, if it answers, get a patent. If you choose

to be partner with me in the profit, and expense, and trouble, let

me know, as I am determined to execute it if you approve of it.

"Please to remember the pulses of the common fire-engines,

and say in what manner the piston is so made as to keep out the air

in its motion. By what way is the jet d'eau froid let

out of the cylinder? How full of water is the boiler?

How is it supplied, and what is the quantity of its waste of water?"

[p.56-2]

It will be observed from these remarks that the doctor's

notions were of the crudest sort, and, as he obviously contemplated

but a modification of the Newcomen engine, then chiefly employed in

pumping water from mines, the action of which was slow, clumsy, and

expensive, the steam being condensed by injection of cold water, it

is clear that, even though Boulton had taken up and prosecuted

Darwin's idea, it could not have issued in a practicable or

economical working locomotive.

But, although Darwin himself—his time engrossed by his

increasing medical practice—proceeded no farther with his scheme of

a "fiery chariot," he succeeded in inflaming the mind of his young

friend, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, who had settled for a time in his

neighbourhood, and induced him to direct his attention to the

introduction of improved means of locomotion by steam. In a

letter written by Dr. Small to Watt in 1768, we find him describing

Edgeworth as "a gentleman of fortune, young, mechanical, and

indefatigable, who has taken a resolution to move land and water

carriages by steam, and has made considerable progress in the short

space of time that he has devoted to the study.''

One of the first-fruits of Edgeworth's investigations was his

paper "On Railroads" which he read before the Society of Arts in

1768, and for which he was awarded the society's gold medal.

He there proposed that four iron railroads be laid down on one of

the great roads out of London; two for carts and wagons, and two for

light carriages and stage-coaches. The post-chaises and

gentlemen's carriages might, he thought, be made to go at eight

miles an hour, and the stage-coaches at six miles an hour, drawn by

a single horse. He urged that such a method of transport would

be attended with great economy of power and consequent cheapness.

Many years later, in 1802, he published his views on the same

subject in a more matured form. By that time Watt's

steam-engine had come into general use, and he suggested that small

stationary engines should be fixed along his proposed railroad, and

made, by means of circulating chains, to draw the carriages along

with a great diminution of horse labour and expense.

It is creditable to Mr. Edgeworth's forethought that both the

models proposed by him have since been adopted. Horse-traction

of carriages on railways is now in general use in the towns of the

United States; and omnibuses on the same principle regularly ply

between the Place de la Concorde at Paris and St. Cloud, both being

found highly convenient for the public, and profitable to the

proprietors éd.—horse trams]. The system of working railways

by fixed engines was also regularly employed on some lines in the

infancy of the railway system, though it has since fallen into

disuse, in consequence of the increased power given to the modern

locomotive, which enables it to surmount gradients formerly

considered impracticable.

Besides his speculations on railways worked by horse and

steam power, Mr. Edgeworth—unconscious of the early experiments of

Stevins and Mackworth—made many attempts to apply the power of the

wind with the same object. It is stated in his "Memoirs" that

he devoted himself to locomotive traction by various methods for a

period of about forty years, during which he made above a hundred

working models, in a great variety of forms; and though none of his

schemes were attended with practical success, he adds that he gained

far more in amusement than he lost by his unsuccessful labours.

"The only mortification that affected me," he says, "was my

discovery, many years after I had taken out my patent [for the

sailing-carriage], that the rudiments of my whole scheme were

mentioned in an obscure memoir of the French Academy."

The sailing-wagon scheme, as revived by Mr. Edgeworth, was

doubtless of a highly ingenious character, though it was not

practicable. One of his expedients was a portable railway, of

a kind somewhat similar to that since revived by Mr. Boydell.

Many experiments were tried with the new wagons on Hare Hatch

Common, but they were attended with so much danger when the wind

blew strong—the vehicles seeming to fly rather than roll along the

ground—that farther experiments were abandoned, and Mr. Edgeworth

himself at length came to the conclusion that a power so uncertain

as that of the wind could never be relied upon for the safe conduct

of ordinary traffic. His thoughts finally settled on steam as

the only practicable power for this purpose; but, though his

enthusiasm in the cause of improved transit of persons and of goods

remained unabated, he was now too far advanced in life to prosecute

his investigations in that direction. When an old man of

seventy he wrote to James Watt (7th August, 1813): "I have always

thought that steam would become the universal lord, and that we

should in time scorn post-horses. An iron railroad would be a

cheaper thing than a road on the common construction. Four

years later he died, and left the problem, which he had nearly all

his life been trying ineffectually to solve, to be worked out by

younger men.

Dr. Darwin had long before preceded him into the silent land.

Down to his death in 1802, Edgeworth had kept up a continuous

correspondence with him on his favourite topic; but it does not

appear that Darwin ever revived his project of the "fiery chariot."

He was satisfied to prophesy its eventual success in the lines which

are perhaps more generally known than any he has written—for, though

Horace Walpole declared that he could ''read the Botanic Garden over

and over again forever," the poetry of Darwin is now all but

forgotten. The following was his prophecy, published in 1791,

before any practical locomotive or steam-boat had been invented:

|

"Soon shall thy arm, unconquered steam,

afar

Drag the slow barge, or drive the rapid car;

Or on wide-waving wings expanded bear

The flying chariot through the fields of air.

Fair crews triumphant, leaning from above,

Shall wave their flutt'ring kerchiefs as they move;

Or warrior bands alarm the gaping crowd.

And armies shrink beneath the shadowy cloud." |

The prophecy embodied in the first two lines of the passage

has certainly been fulfilled, but the triumph of the steam balloon

has yet to come.

CHAPTER II.

EARLY LOCOMOTIVE MODELS.

THE

application of steam-power to the driving of wheel-carriages on

common roads was in 1759 brought under the notice of James Watt by

his young friend John Robison, then a student at the University of

Glasgow. Robison prepared a rough sketch of his suggested

steam-carriage, in which he proposed to place the cylinder with its

open end downward, to avoid the necessity for using a working beam.

Watt was then only twenty-three years old, and was very much

occupied in conducting his business of a mathematical instrument

maker, which he had only recently established. Nevertheless,

he proceeded to construct a model locomotive provided with two

cylinders of tin-plate, intending that the pistons and their

connecting-rods should act alternately on two pinions attached to

the axles of the carriage-wheels. But the model, when made,

did not answer Watt's expectations; and when, shortly after, Robison

left college to go to sea, he laid the project aside, and did not

resume it for many years.

In the mean time, an ingenious French mechanic had taken up

the subject, and proceeded to make a self-moving road engine worked

by steam-power. It has been incidentally stated that a M.

Pouillet was the first to make a locomotive machine,[p.60]

but no particulars are given of the invention, which is more usually

attributed to Nicholas Joseph Cugnot, a native of Void, in Lorraine,

where he was born in 1729. Not much is known of Cugnot's early

history beyond that he was an officer in the army, that he published

several works on military science, and that on leaving the army he

devoted himself to the invention of a steam-carriage to be run on

common roads.

It appears from documents collected by M. Morin that Cugnot

constructed his first carriage at the Arsenal in 1769, at the cost

of the Comte de Saxe, by whom he was patronized and liberally

helped. It ran on three wheels, and was put in motion by an

engine composed of two single-acting cylinders, the pistons of which

acted alternately on the single front wheel. While this

machine was in course of construction, a Swiss officer, named Planta,

brought forward a similar project; but, on perceiving that Cugnot's

carriage was superior to his own, he proceeded no farther with it.

When Cugnot's carriage was ready, it was tried in the

presence of the Duc de Choiseul, the Comte de Saxe, and other

military officers. On being first set in motion, it ran

against a stone wall which stood in its way, and threw it down.

There was thus no doubt about its power, though there were many

doubts about its manageableness. At length it was got out of

the Arsenal and put upon the road, when it was found that, though

only loaded with four persons, it could not travel faster than about

two and a quarter miles an hour; and that, the size of the boiler

not being sufficient, it would not continue at work for more than

twelve or fifteen minutes, when it was necessary to wait until

sufficient steam had been raised to enable it to proceed farther.

The experiment was looked upon with great interest, and

admitted to be of a very remarkable character; and, considering that

it was a first attempt, it was not by any means regarded as

unsuccessful. As it was believed that such a machine, if

properly proportioned, might be employed to drag cannon into the

field independent of horse-power, the Minister of War authorized

Cugnot to proceed with the construction of a new and improved

machine, which was finished and ready for trial in the course of the

following year. The new locomotive was composed of two parts,

one being a carriage supported on two wheels, somewhat resembling a

small brewer's cart, furnished with a seat for the driver, while the

other contained the machinery, which was supported on a single

driving-wheel 4 ft. 2 in. in diameter. The engine consisted of

a round copper boiler with a furnace inside provided with two small

chimneys, two single-acting 13-in. brass cylinders communicating

with the boiler by a steam-pipe, and the arrangements for

communicating the motion of the pistons to the driving-wheel,

together with the steering-gear.

The two parts of the machine were united by a movable pin and

a toothed sector fixed on the framing of the front or machine part

of the carriage. When one of the pistons descended, the

piston-rod drew with it a crank, the catch of which caused the

driving-wheel to make a quarter of a revolution by means of the

ratchet wheel fixed on the axle of the driving-wheel. At the

same time, a chain fixed to the crank on the same side also

descended and moved a lever, the opposite end of which was thereby

raised, restoring the second piston to its original position at the

top of the cylinder by the interposition of a second chain and

crank. The piston-rod of the descending piston, by means of a

catch, set other levers in motion, the chain fixed to them turning a

half-way cock so as to open the second cylinder to the steam and the

first to the atmosphere. The second piston, then descending in

turn, caused the driving-wheel to make another quarter revolution,

restoring the first piston to its original position; and the process

being repeated, the machine was thereby kept in motion. To

enable it to run backward, the catch of the crank was arranged in

such a manner that it could be made to act either above or below,

and thereby reverse the action of the machinery on the

driving-wheel. It will thus be observed that Cugnot's

locomotive presented a simple and ingenious form of a high-pressure

engine; and, though of rude construction, it was a highly-creditable

piece of work, considering the time of its appearance and the

circumstances under which it was constructed.

Several successful trials were made with the new locomotive

in the streets of Paris, which excited no small degree of interest.

Unhappily, however, an accident which occurred to it in one of the

trials had the effect of putting a stop to farther experiments.

Turning the corner of a street near the Madeleine one day, when the

machine was running at a speed of about three miles an hour, it

became overbalanced, and fell over with a crash; after which, the

running of the vehicle being considered dangerous, it was

thenceforth locked up securely in the Arsenal to prevent its doing

farther mischief.

The merit of Cugnot was, however, duly recognized. He

was granted a pension of 300 livres, which continued to be paid to

him until the outbreak of the Revolution. The Girondist Roland

was appointed to examine the engine and report upon it to the

Convention; but his report, which was favourable, was not adopted;

on which the inventor's pension was stopped, and he was left for a

time without the means of living. Some years later, Bonaparte,

on his return from Italy after the peace of Campo Formio, interested

himself in Cugnot's invention, and expressed a favourable opinion of

his locomotive before the Academy; but his attention was shortly

after diverted from the subject by the Expedition to Egypt.

Napoleon, however, succeeded in restoring Cugnot's pension, and thus

soothed his declining years. He died in Paris in 1804, at the

age of seventy-five. Cugnot's locomotive is still to be seen

in the Museum of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers at Paris; and

it is, without exception, the most venerable and interesting of all

the machines extant connected with the early history of locomotion.

While Cugnot was constructing his first machine at Paris, one

Francis Moore, a linen-draper, was taking out a patent in London for

moving wheel-carriages by steam. On the 14th of March, 1769,

he gave notice of a patent for "a machine made of wood or metal, and

worked by fire, water, or air, for the purpose of moving bodies on

land or water," and on the 13th of July following he gave notice of

another "for machines made of wood and metal, moved by power, for

the carriage of persons and goods, and for accelerating boats,

barges, and other vessels." But it does not appear that Moore

did any thing beyond lodging the titles of his inventions, so that

we are left in the dark as to what was their precise character.

James Watt's friend and correspondent, Dr. Small, of

Birmingham, when he heard of Moore's intended project, wrote to the

Glasgow inventor with the object of stimulating him to perfect his

steam-engine, then in hand, and urging him to apply it, among other

things, to purposes of locomotion. "I hope soon," said Small,

"to travel in a fiery chariot of your invention." Watt replied

to the effect that "if Linen-draper Moore does not use my engines to

drive his carriages, he can't drive them by steam. If he does,

I will stop them." But Watt was still a long way from

perfecting his invention. The steam-engine capable of driving

carriages was a problem that remained to be solved, and it was a

problem to the solution of which Watt never fairly applied himself.

It was enough for him to accomplish the great work of perfecting his

condensed engine, and with that he rested content.

But Watt continued to be so strongly urged by those about him

to apply steam-power to purposes of locomotion that, in his

comprehensive patent of the 24th of August, 1784, he included an

arrangement with that object. From his specification we learn

that he proposed a cylindrical or globular boiler, protected outside

by wood strongly hooped together, with a furnace inside entirely

surrounded by the water to be heated except at the ends. Two

cylinders working alternately were to be employed, and the pistons

working within them were to be moved by the elastic force of the

steam; "and after it has performed its office," he says, "I

discharge it into the atmosphere by a proper regulating valve, or I

discharge it into a condensing vessel made air-tight, and formed of

thin plates and pipes of metal, having their outsides exposed to the

wind;" the object of this latter arrangement being to economize the

water, which would otherwise be lost. The power was to be

communicated by a rotative motion (of the nature of the "sun and

planet" arrangement) to the axle of one or more of the wheels of the

carriage, or to another axis connected with the axle by means of

toothed wheels; and in other cases he proposed, instead of the

rotative machinery, to employ "toothed racks, or sectors of circles,

worked with reciprocating motion by the engines, and acting upon

ratched wheels fixed on the axles of the carriage." To drive a

carriage containing two persons would, he estimated, require an

engine with a cylinder 7in. in diameter, making sixty strokes per

minute of 1ft. each, and so constructed as to act both on the ascent

and descent of the piston; and, finally, the elastic force of the

steam in the boiler must be such as to be occasionally equal to

supporting a pillar of mercury 30in. high.

Though Watt repeatedly expressed his intention of

constructing a model locomotive after his specification, it does not

appear that he ever carried it out. He was too much engrossed

with other work; and, besides, he never entertained very sanguine

views as to the practicability of road locomotion by steam. He

continued, however, to discuss the subject with his partner Boulton,

and from his letters we gather that his mind continued undetermined

as to the best plan to be pursued. Only four days after the

date of the above specification (i.e. on the 28th of August, 1784)

we find him communicating his views on the subject to Boulton at

great length, and explaining his ideas as to how the proposed object

might best be accomplished. He first addressed himself to the

point of whether 80lbs. was a sufficient power to move a post-chaise

on a tolerably good and level road at four miles an hour; secondly,

whether 8ft of boiler surface exposed to the fire would be

sufficient to evaporate a cube foot of water per hour without much

waste of fuel; thirdly, whether it would require steam of more than

eleven and a half times atmospheric density to cause the engine to

exert a power equal to 6lbs. on the inch. "I think," he

observed, "the cylinder must either be made larger or make more than

sixty strokes per minute. As to working gear, stopping and

backing, with steering the carriage, I think these things perfectly

manageable."

"My original ideas on the subject," he continued, "were prior

to my invention of these improved engines, or before the crank, or

any other of the rotative motions were thought of. My plan

then was to have two inverted cylinders, with toothed racks instead

of piston-rods, which were to be applied to two ratchet-wheels on

the axle-tree, and to act alternately; and I am partly of opinion

that this method might be applied with advantage yet, because it

needs no fly and has some other conveniences. From what I have

said, and from much more which a little reflection will suggest to

you, you will see that without several circumstances turn out more

favourable than has been stated, the machine will be clumsy and

defective, and that it will cost much time to bring it to any

tolerable degree of perfection, and that for me to interrupt the

career of our business would be imprudent; I even grudge the time I

have taken to make these comments on it. There is, however,

another way in which much mechanism might be saved if it be in

itself practicable, which is to apply to it one of the self-moving

rotatives, which has no regulation, but turns like a mill-wheel by

the constant influx and efflux of steam; but this would not abridge

the size of the boiler, and I am not sure that such engines are

practicable."

It will be observed from these explanations that Watt's views

as to road locomotion were still crude and undefined; and, indeed,

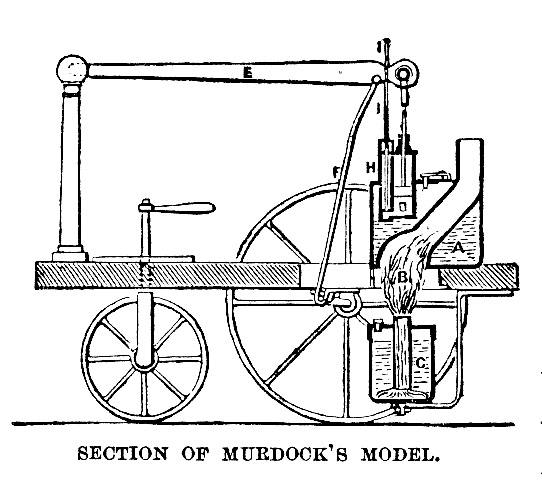

he never carried them farther. While he was thus discussing

the subject with Boulton, William Murdock, one of the most skilled

and ingenious workmen of the Soho firm—then living at Redruth, in

Cornwall—was occupying himself during his leisure hours, which were

but few, in constructing a model locomotive after a design of his

own. He had doubtless heard of the proposal to apply steam to

locomotion, and, being a clever inventor, he forthwith set himself

to work out the problem. The plan he pursued was very simple

and yet efficient. His model was of small dimensions, standing

little more than a foot high, but it was sufficiently large to

demonstrate the soundness of the principle on which it was

constructed. It was supported on three wheels, and carried a

small copper boiler, heated by a spirit-lamp, with a flue passing

obliquely through it. The cylinder, of ¾in. diameter and 3in.

stroke, was fixed in the top of the boiler, the piston-rod being

connected with the vibrating beam attached to the connecting-rod

which worked the crank of the driving-wheel. This little

engine worked by the expansive force of the steam only, which was

discharged into the atmosphere after it had done its work of

alternately raising and depressing the piston in the cylinder.

Mr. Murdock's son informed the author that this model was

invented and constructed in 1781, but, from the correspondence of

Boulton and Watt, we infer that it was not ready for trial until

1784. The first experiment with it was made in Murdock's own

house at Redruth, when it successfully hauled a model wagon round

the room—the single wheel placed in front of the engine, and working

in a swivel frame, enabling it to run round in a circle.

Another experiment was made out of doors, on which occasion,

small though the engine was, it fairly outran the speed of its

inventor. It seems that one night, after returning from his

duties at the Redruth mine, Murdock determined to try the working of

his model locomotive. For this purpose he had recourse to the

walk leading to the church, about a mile from the town. It was

rather narrow, and was bounded on each side by high hedges.

The night was dark, and Murdock set out alone to try his experiment.

Having lit his lamp, the water soon boiled, when off started the

engine, with the inventor after it. Shortly after he heard

distant shouts of terror. It was too dark to perceive objects;

but he found, on following up the machine, that the cries proceeded

from the worthy pastor of the parish, who, going toward the town,

was met on this lonely road by the hissing and fiery little monster,

which he subsequently declared he had taken to be the Evil One in

propria persona!

Watt was by no means pleased when he learned that Murdock was

giving his mind to these experiments. He feared that it might

have the effect of withdrawing him from the employment of the firm,

to which his services had become almost indispensable; for there was

no more active, skilful, or ingenious workman in all their concern.

Watt accordingly wrote to Boulton, recommending him to advise

Murdock to give up his locomotive-engine scheme; but, if he could

not succeed in that, then, rather than lose Murdock's services, Watt

proposed that he should be allowed an advance of £100 to enable him

to prosecute his experiments, and if he succeeded within a year in

making an engine capable of drawing a post-chaise carrying two

passengers and the driver at four miles an hour, it was suggested

that he should be taken as partner into the locomotive business, for

which Boulton and Watt were to provide the necessary capital.

Two years later (in September, 1786) we find Watt again

expressing his regret to Boulton that Murdock was "busying himself

with the steam-carriage." "I have still," said he, "the same

opinion concerning it that I had, but to prevent as much as possible

more fruitless argument about it, I have one of some size under

hand, and am resolved to try if God will work a miracle in favour of

these carriages. I shall in some future letter send you the

words of my specification on that subject. In the mean time I

wish William could be brought to do as we do, to mind the business

in hand, and let such as Symington and Sadler throw away their time

and money in hunting shadows." In a subsequent letter Watt

expressed his gratification at finding "that William applies to his

business." From that time Murdock as well as Watt dropped all

farther speculation on the subject, and left it to others to work

out the problem of the locomotive engine. Murdock's model

remained but a curious toy, which he himself took pleasure in

exhibiting to his intimate friends; and though he long continued to

speculate about road locomotion, and was persuaded of its

practicability, he refrained from embodying his ideas of it in any

more complete working form.

Symington and Sadler, the "hunters of shadows" referred to by

Watt, did little to advance the question. Of Sadler we know

nothing beyond that in 1786 he was making experiments as to the

application of steam-power to the driving of wheel-carriages.

This came to the knowledge of Boulton and Watt, who gave him notice,

on the 4th of July of the same year, that "the sole privilege of

making steam-engines by the elastic force of steam acting on a

piston, with or without condensation, had been granted to Mr. Watt

by Act of Parliament, and also that among other improvements and

applications of his principle he hath particularly specified the

application of steam-engines for driving wheel carriages in a patent

which he took out in the year 1784." They accordingly

cautioned him against proceeding farther in the matter; and as we

hear no more of Sadler's steam-carriage, it is probable that the

notice had its effect.

The name of William Symington is better known in connection

with the history of steam locomotion by sea. He was born at

Leadhills, in Scotland, in 1763. His father was a practical

mechanic, who superintended the engines and machinery of the Mining

Company at Wanlockhead, where one of Boulton and Watt's

pumping-engines was at work. Young Symington was of an

ingenious turn of mind from his boyhood, and at an early period he

seems to have conceived the idea of employing the steam-engine to

drive wheel-carriages. His father and he worked together, and

by the year 1786, when the son was only twenty-three years of age,

they succeeded in completing a working model of a road locomotive.

Mr. Meason, the manager of the mine, was so much pleased with the

model, the merit of which principally belonged to young Symington,

that he sent him to Edinburg for the purpose of exhibiting it before

the scientific gentlemen of that city, in the hope that it might

lead, in some way, to his future advancement in life. Mr.

Meason also allowed the model to be exhibited at his own house

there, and he invited many gentlemen of distinction to inspect it.

This machine consisted of a carriage and locomotive behind,

supported on four wheels. The boiler was cylindrical,

communicating by a steam-pipe with the two horizontal cylinders, one

on each side of the engine. When the piston was raised by the

action of the steam, a vacuum was produced by the condensation of

the steam in a cold-water tank placed underneath the engine, on

which the piston was again forced back by the pressure of the

atmosphere. The motion was communicated to the wheels by

rack-rods connected with the piston-rod, which worked on each side

of a drum fixed on the hind axle, the alternate action of which rods

upon the tooth and ratchet wheels with which the drum was provided

producing the rotary motion. It will thus be observed that

Symington's engine was partly atmospheric and partly condensing, the

condensation being effected by a separate vessel and air-pump, as

patented by Watt; and though the arrangement was ingenious, it is

clear that, had it ever been brought into use, the traction by means

of such an engine would have been of the very slowest kind.

But Symington's engine was not destined to be applied to road

locomotion. He was completely diverted from employing it for

that purpose by his connection with Mr. Miller, of Dalswinton, then

engaged in experimenting on the application of mechanical power to

the driving of his double paddle-boat The power of men was

first tried, but the labour was found too severe; and when Mr.

Miller went to see Symington's model, and informed the inventor of

his difficulty in obtaining a regular and effective power for

driving his boat, Symington—his mind naturally full of his own

invention—at once suggested his steam-engine for the purpose.

The suggestion was adopted, and Mr. Miller authorized him to proceed

with the construction of a steam-engine to be fitted into his double

pleasure boat on Dalswinton Lock, where it was tried in October,

1788. This was followed by farther experiments, which

eventually led to the construction of the Charlotte Dundas in

1801, which may be regarded as the first practical steam-boat ever

built.

Symington took out letters patent in the same year, securing

the invention, or rather the novel combination of inventions,

embodied in his steam-boat, but he never succeeded in getting it

introduced into practical use. From the date of completing his

invention, fortune seemed to run steadily against him. The

Duke of Bridgewater, who had ordered a number of Symington's

steamboats for his canal, died, and his executors countermanded the

order. Symington failed in inducing any other canal company to

make trial of his invention. Lord Dundas also took the

Charlotte Dundas off the Forth and Clyde Canal, where she had

been at work, and from that time the vessel was never more tried.

Symington had no capital of his own to work upon, and he seems to

have been unable to make friends among capitalists. The rest

of his life was for the most part thrown away. Toward the

close of it his principal haunt was London, amid whose vast

population he was one of the many waifs and strays. He

succeeded in obtaining a grant of £100 from the Privy Purse in 1824,

and afterward an annuity of £50, but he did not live long to enjoy

it, for he died in March, 1831, and was buried in the church-yard of

St. Botolph, Aldgate, where there is not even a stone to mark the

grave of the inventor of the first practicable steam-boat.

While the inventive minds of England were thus occupied,

those of America were not idle. The idea of applying

steam-power to the propulsion of carriages on land is said to have

occurred to John Fitch in 1785; but he did not pursue the idea "for

more than a week," being diverted from it by his scheme of applying

the same power to the propulsion of vessels on the water.[p.71]

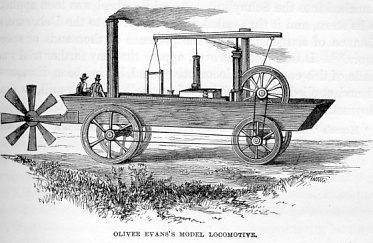

About the same time, Oliver Evans, a native of Newport, Delaware,

was occupied with a project for driving steam-carriages on common

roads; and in 1786 the Legislature of Maryland granted him the

exclusive right for that state. Several years, however, passed

before he could raise the means for erecting a model carriage, most

of his friends regarding the project as altogether chimerical and

impracticable. In 1800 or 1801, Evans began a steam-carriage

at his own expense; but he had not proceeded far with it when he

altered his intention, and applied the engine intended for the

driving of a carriage to the driving of a small grinding-mill, in

which it was found efficient. In 1804 he constructed at

Philadelphia a second engine of five-horse power, working on the

high-pressure principle, which was placed on a large flat or scow,

mounted upon wheels. "This," says his biographer, "was

considered a fine opportunity to show the public that his engine

could propel both land and water conveyances. When the machine

was finished, Evans fixed under it, in a rough and temporary manner,

wheels with wooden axle-trees. Although the whole weight was

equal to two hundred barrels of flour, yet his small engine

propelled it up Market Street, and round the circle to the

water-works, where it was launched into the Schuylkill. A

paddle-wheel was then applied to its stem, and it thus sailed down

that river to the Delaware, a distance of sixteen miles, in the

presence of thousands of spectators.[p.72]

It does not, however, appear that any farther trial was made of this

engine as a locomotive; and, having been dismounted and applied to

the driving of a small grinding-mill, its employment as a travelling

engine was shortly forgotten.

CHAPTER III.

THE CORNISH LOCOMOTIVE—MEMOIR OF RICHARD TREVITHICK.

WHILE

the discussion of steam-power as a means of locomotion was

proceeding in England, other projectors were advocating the

extension of wagon-ways and railroads. Mr. Thomas, of Denton,

near Newcastle-on-Tyne, read a paper before the Philosophical

Society of that town in 1800, in which he urged the laying down of

railways throughout the country, on the principle of the coal

wagon-ways, for the general carriage of goods and merchandise; and

Dr. James Anderson, of Edinburg, about the same time published his

"Recreations of Agriculture,'' wherein he recommended that railways

should be laid along the principal turnpike-roads, and worked by

horse-power, which, he alleged, would have the effect of greatly

reducing the cost of transport, and thereby stimulating all branches

of industry.

Railways were indeed already becoming adopted in places where

the haulage of heavy loads was for short distances; and in some

cases lines were laid down of considerable length. One of the

first of such lines constructed under the powers of an Act of

Parliament was the Cardiff and Merthyr railway or tram-road, about

twenty-seven miles in length, for the accommodation of the

iron-works of Plymouth, Pen-y-darran, and Dowlais, all in South

Wales, the necessary Act for which was obtained in 1794.

Another, the Sirhoway railroad, about twenty-eight miles in length,

was constructed under the powers of an act obtained in 1801; it

accommodated the Tredegar and Sirhoway Iron-works and the Trevill

Lime-works, as well as the collieries along its route.

In the immediate neighbourhood of London there was another

very early railroad, the Wandsworth and Croydon tram-way, about ten

miles long, which was afterward extended southward to Merstham, in

Surrey, for about eight miles more, making a total length of nearly

eighteen miles. The first act for the purpose of authorizing

the construction of this road was obtained in 1800.

All these lines were, however, worked by horses, and in the

case of the Croydon and Merstham line, donkeys shared in the work,

which consisted chiefly in the haulage of stone, coal, and lime.

No proposal had yet been made to apply the power of steam as a

substitute for horses on railways, nor were the rails then laid down

of a strength sufficient to bear more than a loaded wagon of the

weight of three tons, or, at the very outside, of three and a

quarter tons.

It was, however, observed from the first that there was an

immense saving in the cost of haulage; and on the day of opening the

southern portion of the Merstham Railroad in 1805, a train of twelve

wagons laden with stone, weighing in all thirty-eight tons, was

drawn six miles in an hour by one horse, with apparent ease, down an

incline of 1 in 120; and this was bruited about as an extraordinary

feat, highly illustrative of the important uses of the new

iron-ways.

About the same time, the subject of road locomotion was again

brought into prominent notice by an important practical experiment

conducted in a remote corner of the kingdom. The experimenter

was a young man, then obscure, but afterward famous, who may be

fairly regarded as the inventor of the railway locomotive, if any

single individual be entitled to that appellation. This was

Richard Trevithick, a person of extraordinary mechanical skill but

of marvellous ill fortune, who, though the inventor of many

ingenious contrivances, and the founder of the fortunes of many,

himself died in cold obstruction and in extreme poverty, leaving

behind him nothing but his great inventions and the recollection of

his genius.

Richard Trevithick was born on the 13th of April, 1771, in

the parish of Illogan, a few miles west of Redruth, in Cornwall.

In the immediate neighbourhood rises Castle-Carn-brea, a rocky

eminence, supposed by Borlase to have been the principal seat of

Druidic worship in the West of England. The hill commands an

extraordinary view over one of the richest mining fields of

Cornwall, from Chacewater and Redruth to Camborne.

Trevithick's father acted as purser at several of the mines.

Though a man in good position and circumstances, he does not seem to

have taken much pains with his son's education. Being an only

child, he was very much indulged—among other things, in his dislike

for the restraints and discipline of school; and he was left to

wander about among the mines, spending his time in the engine-rooms,

picking up information about pumping-engines and mining machinery.

His father, observing the boy's strong bent toward mechanics,

placed him for a time as pupil with William Murdock, while the

latter lived at Redruth superintending the working and repairs of

Boulton and Watt's pumping-engines in that neighbourhood.

During his pupilage, young Trevithick doubtless learned much from

that able mechanic. It is probable that he got his first idea

of the high-pressure road locomotive which he afterward constructed

from Murdock's ingenious little model above described, the

construction and action of which must have been quite familiar to

him, for no secret was ever made of it, and its performances were

often exhibited.

Many new pumping-engines being in course of erection in the

neighbourhood about that time, there was an unusual demand for

engineers, which it was found difficult to supply; and young

Trevithick, whose skill was acknowledged, had no difficulty in

getting an appointment. The father was astonished at his boy's

presumption (as he supposed it to be) in undertaking such a

responsibility, and he begged the mine agents to reconsider their

decision. But the result showed that they were justified in

making the appointment; for young Trevithick, though he had not yet

attained his majority, proved fully competent to perform the duties

devolving upon him as engineer.

So long as Boulton and Watt's patent continued to run,

constant attempts were made in Cornwall and elsewhere to upset it.

Their engines had cleared the mines of water, and thereby rescued

the mine lords from ruin, but it was felt to be a great hardship

that they should have to pay for the right to use them. They

accordingly stimulated the ingenuity of the local engineers to

contrive an engine that should answer the same purpose, and enable

them to evade making any farther payments to Boulton and Watt.

The first to produce an engine that seemed likely to answer the

purpose was Jonathan Hornblower, who had been employed in erecting

Watt's engines in Cornwall. After him one Edward Bull, who had

been first a stoker and then an assistant-tender of Watt's engines,

turned out another pumping-engine, which promised to prove an

equally safe evasion of the existing patent. But Boulton and

Watt having taken the necessary steps to defend their right, several

actions were tried, in which they proved successful, and then the

mine lords were compelled to disgorge. When they found that

Hornblower could be of no farther use to them, they abandoned

him—threw him away like a sucked orange; and shortly after we find

him a prisoner for debt in the King's Bench, almost in a state of

starvation. Nor do we hear any thing more of Edward Bull after

the issue of the Boulton and Watt trial.

Like the other Cornish engineers, young Trevithick took an

active part from the first in opposing the Birmingham patent, and he

is said to have constructed several engines, with the assistance of

William Bull (formerly an erector of Watt's machines), with the

object of evading it. These engines are said to have been

highly creditable to their makers, working to the entire

satisfaction of the mine-owners. The issue of the Watt trial,

however, which declared all such engines to be piracies, brought to

an end for a time a business which would otherwise have proved a

very profitable one, and Trevithick's partnership with Bull then

came to an end.

While carrying on his business, Trevithick had frequent

occasion to visit Mr. Harvey's iron foundry at Hayle, then a small

work, but now one of the largest in the West of England, the Cornish

pumping-engines turned out by Harvey and Co. being the very best of

their kind. During these visits Trevithick became acquainted

with the various members of Mr. Harvey's family, and in course of

time he contracted an engagement with one of his daughters, Miss

Jane Harvey, to whom he was married in November, 1797.

A few years later we find Trevithick engaged in partnership

with his cousin, Andrew Vivian, also an engineer. They carried

on their business of engine-making at Camborne, a mining town

situated in the midst of the mining district, a few miles south of

Redruth. Watt's patent-right expired in 1800, and from that

time the Cornish engineers were free to make engines after their own

methods. Trevithick was not content to follow in the beaten

paths, but, being of a highly speculative turn, he occupied himself

in contriving various new methods of employing steam with the object

of economizing fuel and increasing the effective power of the

engine.

From an early period he entertained the idea of making the

expansive force of steam act directly on both sides of the piston on

the high-pressure principle, and thus getting rid of the process of

condensation as in Watt's engines. Although Cugnot had

employed high-pressure steam in his road locomotive, and Murdock in

his model, and although Watt had distinctly specified the action of

steam at high-pressure as well as low in his patents of 1769, 1782,

and 1784, the idea was not embodied in any practicable working

engine until the subject was taken in hand by Trevithick. The

results of his long and careful study were embodied in the patent

which he took out in 1802, in his own and Vivian's name, for an

improved steam-engine, and "the application thereof for driving

carriages and for other purposes."

The arrangement of Trevithick's engine was exceedingly

ingenious. It exhibited a beautiful simplicity of parts; the

machinery was arranged in a highly effective form, uniting strength

with solidity and portability, and enabling the power of steam to be

employed with very great rapidity, economy, and force. Watt's

principal objection to using high-pressure steam consisted in the

danger to which the boiler was exposed of being burst by internal

pressure. In Trevithick's engine, this was avoided by using a

cylindrical wrought-iron boiler, being the form capable of

presenting the greatest resistance to the expansive force of steam.

Boilers of this kind were not, however, new. Oliver Evans, of

Delaware, had made use of them in his high-pressure engines prior to

the date of Trevithick's patent; and, as Evans did not claim the

cylindrical boiler, it is probable that the invention was in use

before his time. Nevertheless, Trevithick had the merit of

introducing the round boilers into Cornwall, where they are still

known as "Trevithick boilers." The saving in fuel effected by

their use was such that in 1812 the Messrs. Williams, of Scorrier,

made Trevithick a present of £300, in acknowledgment of the benefits

arising to their mines from that source alone.

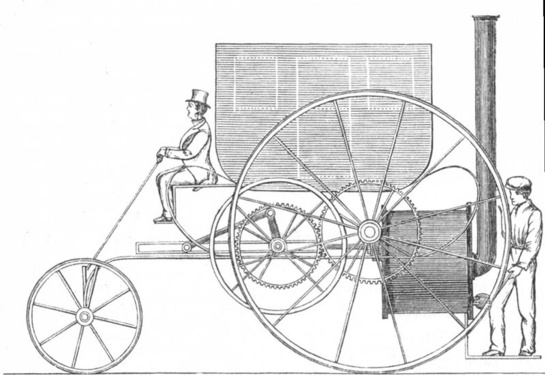

Trevithick and Vivian's steam-carriage, 1803.

Trevithick's steam-carriage was the most compact and handsome

vehicle of the kind that had yet been invented, and, indeed as

regards arrangement, it has scarcely to this day been surpassed.

It consisted of a carriage capable of accommodating some half-dozen

passengers, underneath which was the engine and machinery inclosed,

about the size of an orchestra drum, the whole being supported on

four wheels—two in front, by which it was guided, and two behind, by

which it was driven. The engine had but one cylinder.

The piston-rod outside the cylinder was double, and drove a

cross-piece, working in guides, on the opposite side of the cranked

axle to the cylinder, the crank of the axle revolving between the

double parts of the piston-rod. Toothed wheels were attached

to this axle, which worked into other toothed wheels fixed on the

axle of the driving-wheels. The steam-cocks were opened and

shut by a connection with the crank-axle; and the force-pump, with

which the boiler was supplied with water, was also worked from it,

as were the bellows to blow the fire and thereby keep up the

combustion in the furnace.

The specification clearly alludes to the use of the engine on

railroads as follows: "It is also to be noticed that we do

occasionally, or in certain cases, make the external periphery of

the wheels uneven by projecting heads of nails or bolts, or cross

grooves or fittings to railroads where required, and that in cases

of hard pull we cause a lever, belt, or claw to project through the

rim of one or both of the said wheels, so as to take hold of the

ground, but that, in general, the ordinary structure or figure of

the external surface of those wheels will be found to answer the

intended purpose."

The specification also shows the application of the

high-pressure engine on the same principle to the driving of a

sugar-mill, or for other purposes where a fixed power is required,

dispensing with condenser, cistern, air-pump, and cold-water pump.

In the year 1803, a small engine of this kind was erected after

Trevithick's plan at Marazion, which worked by steam of at least

30lbs. on the inch above atmospheric pressure, and gave much

satisfaction.

The first experimental steam-carriage was constructed by

Trevithick and Vivian in their workshops at Camborne in 1803, and

was tried by them on the public road adjoining the town, as well as

in the street of the town itself. John Petherick, a native of

Camborne, who was alive in 1858, stated in a letter to Mr. Edward

Williams that he well remembered seeing the engine, worked by Mr.

Trevithick himself, come through the place, to the great wonder of

the inhabitants. He says, "The experiment was satisfactory

only as long as the steam pressure could be kept up. During

that continuance Trevithick called upon the people to 'jump up,' so

as to create a load on the engine; and it soon became covered with

men, which did not seem to make any difference to the power or speed

so long as the steam was kept up. This was sought to be done

by the application of a cylindrical horizontal bellows worked by the

engine itself; but the attempt to keep up the power of the steam for

any considerable time proved a failure."

Trevithick, however, made several alterations in the engine

which had the effect of improving it, and its success was such that

he determined to take it to London and exhibit it there as the most

recent novelty in steam mechanism. It was successfully run by

road from Camborne to Plymouth, a distance of about ninety miles.

At Plymouth it was shipped for London, where it shortly after

arrived in safety and excited considerable curiosity. It was

run on the waste ground in the vicinity of the present Bethlehem

Hospital, as well as on Lord's cricket-ground. There Sir

Humphry Davy, Mr. Davies Gilbert, and other scientific gentlemen

inspected the machine and rode upon it. Several of them took

the steering of the carriage by turns, and they expressed their

satisfaction with the mechanism by which it was directed. Sir

Humphry, writing to a friend in Cornwall, said, "I shall soon hope

to hear that the roads of England are the haunts of Captain

Trevithick's dragons—a characteristic name." After the

experiment at Lord's, the carriage was run along the New-road, and

down Gray's-Inn Lane, to the premises of a carriage-builder in Long

Acre. To show the adaptability of the engine for fixed uses,

Trevithick had it taken from the carriage on the day after this

trial and removed to the shop of a cutler, where he applied it with

success to the driving of the machinery.

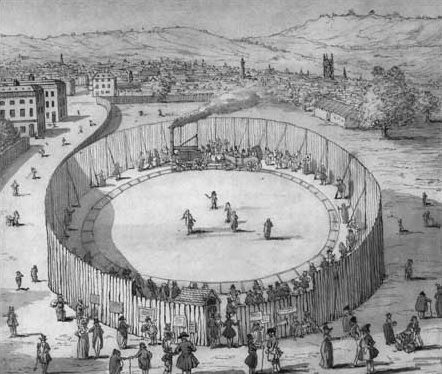

The steam-carriage shortly became the talk of the town, and

the public curiosity being on the increase, Trevithick resolved on

inclosing a piece of ground on the site of the present Euston

station of the London and North-western Railway, and admitting

persons to see the exhibition of his engine at so much a head.

He had a tram-road laid down in an elliptical form within the

inclosure, and the carriage was run round it on the rails in the

sight of a great number of spectators. On the second day

another crowd collected to see the exhibition, but, for what reason

is not known, although it is said to have been through one of

Trevithick's freaks of temper, the place was closed and the engine

removed. It is, however, not improbable that the inventor had

come to the conclusion that the state of the roads at that time was

such as to preclude its coming into general use for purposes of

ordinary traffic.

While the steam-carriage was being exhibited, a gentleman was

laying heavy wagers as to the weight which could be hauled by a

single horse on the Wandsworth and Croydon iron tram-way; and the

number and weight of wagons drawn by the horse were something

surprising. Trevithick very probably put the two things

together—the steam-horse and the iron-way—and kept the performance

in mind when he proceeded to construct his second or railway

locomotive. In the mean time, having dismantled his

steam-carriage, sent back the phaeton to the coach-builder to whom

it belonged, and sold the little engine which had worked the

machine, he returned to Camborne to carry on his business. In

the course of the year 1803 he went to Pen-y-darran, in South Wales,

to erect a forge engine for the iron-works there; and, when it was

finished, he began the erection of a railway locomotive—the first

ever constructed. There were already, as above stated, several

lines of rail laid down in the district for the accommodation of the

coal and iron works. That between Merthyr Tydvil and Cardiff

was the longest and most important, and it had been at work for some

years. It had probably occurred to Trevithick that here was a fine

opportunity for putting to practical test the powers of the

locomotive, and he proceeded to construct one accordingly in the

workshops at Pen-y-darran.

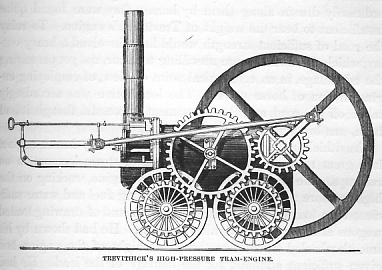

This first railway locomotive was finished and tried upon the

Merthyr tram-road on the 21st of February, 1804. It had a

cylindrical wrought-iron boiler with flat ends. The furnace

and flue were inside the boiler, the flue returning, having its exit

at the same end at which it entered, so as to increase the heating

surface. The cylinder, 4¾in. in diameter, was placed

horizontally in the end of the boiler, and the waste steam was

thrown into the stack. The wheels were worked in the same

manner as in the carriage engine already described; and a fly-wheel

was added on one side, to secure a continuous rotary motion at the

end of each stroke of the piston. The pressure of the steam

was about 40lbs. on the inch. The engine ran upon four wheels,

coupled by cog-wheels, and those who remember the engine say that

the four wheels were smooth.

On the first trial, this engine drew for a distance of nine

miles ten tons of bar iron, together with the necessary carriages,

water, and fuel, at the rate of five and a half miles an hour.

Rees Jones, an old engine-fitter, who helped to erect the engine,

and was alive in,1858, gave Mr. Menelaus the following account of

its performances: "When the engine was finished, she was used for

bringing down metal from the old forge. She worked very well;

but frequently, from her weight, broke the tram-plates, and also the

hooks between the trams. After working for some time in this

way, she took a journey of iron from Pen-y-darran down the Basin

Boad, upon which road she was intended to work. On the journey

she broke a great many of the tram-plates; and, before reaching the

Basin, she ran off the road, and was brought back to Pen-y-darran by

horses. The engine was never used as a locomotive after this;

but she was used as a stationary engine, and worked in this way for

several years."

So far as the locomotive was concerned it was a remarkable

success. The defect lay not in the engine so much as in the

road. This was formed of plate-rails of cast iron, with a

guiding flange upon the rail instead of on the engine wheels, as in

the modem locomotive. The rails were also of a very weak form,

considering the quantity of iron in them; and, though they were

sufficient to bear the loaded wagons mounted upon small wheels, as

ordinarily drawn along them by horses, they were found quite