|

The engine went through its usual performances, dragging a heavy

load of coal-wagons at about six miles an hour with apparent ease,

at which Mr. James expressed his extreme satisfaction, and declared

to Mr. Losh his opinion that Stephenson "was the greatest practical

genius of the age" and that, "if he developed the full powers of

that engine (the locomotive), his fame in the world would rank equal

with that of Watt." Mr. James informed Stephenson and Losh of his

survey of the proposed tram-road between Liverpool and Manchester,

and did not hesitate to state that he would thenceforward advocate

the construction of a locomotive railroad instead of the tram-road

which had originally been proposed.

Stephenson and Losh were naturally desirous of enlisting James's

good services on behalf of their patent locomotive, for as yet it

had proved comparatively unproductive. They believed that he might

be able so to advocate it in influential quarters as to insure its

more extensive adoption, and with that object they proposed to give

him an interest in the patent. Accordingly, they entered into an

agreement by which they assigned to him one fourth of any profits

which might be derived from the use of the patent locomotive on any

railways constructed south of a line drawn across England from

Liverpool to Hull. The arrangement, however, led to no beneficial

results. Mr. James endeavoured to introduce the engine on the Moreton-on-Marsh Railway, but it was opposed by the engineer of the

line, and the attempt failed. He next urged that a locomotive should

be sent for trial upon the Mersham tram-road; but, anxious though

Stephenson was to to its extended employment, he was too cautious to

risk experiment which might bring discredit upon the engine; and the

Mersham Road being only laid with cast-iron plates which would not

bear its weight, the invitation was declined.

The first survey made of the Liverpool and Manchester line having

been found very imperfect, it was determined to have a second and

more complete one made in the following year. Robert Stephenson,

though then a lad of only nineteen, had already obtained some

practical knowledge of surveying, having been engaged on the

preliminary survey of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in the

previous year, and he was sent over to Liverpool by his father to

give Mr. James such assistance as he could. Robert Stephenson was

present with Mr. James on the occasion which he tried to lay out the

line across Chat Moss—a proceeding which was not only difficult, but

dangerous. The Moss "was very wet at the time, and only its edges

could be ventured on. Mr. James was a heavy, thick-set man; and one

day, when endeavouring to obtain a stand for his theodolite, he felt

himself suddenly sinking. He immediately threw himself down, and

rolled over and over until he reached firm ground again, in a sad

mess. Other attempts which he subsequently made to advance into the

Moss

for the same purpose were abandoned for the same reason—the want of

a solid stand for the theodolite.

As Mr. James proceeded with his survey, he found a host of opponents

springing up in all directions, some of whom he conciliated by

deviations, but others refused to be conciliated on any terms. Among

these last were Lords Derby and Wilton, Mr. Bradshaw, and the

Strafford family. The proposed line passed through their lands, and,

regarding it as a nuisance, without the slightest compensating

advantage to them, they determined to oppose it at every stage. Their agents drove the surveyors off the land; the farmers set men

at the gates armed with pitchforks to resist their progress; and the

survey proceeded with great difficulty. Mr. James endeavoured to

avoid Lord Derby's Knowsley estate, but as he had received

instructions from Messrs. Ewart and Gladstone to lay out the line so

as to enable it to be extended to the docks, he found it difficult

to accomplish this object and at the same time avert the hostility

of the noble lord. The only large land-owners who gave the scheme

their support were Mr. Legh and Mr. Wyrley Birch, who not only

subscribed for shares, but attended several public meetings, and

spoke in favour of the proposed railroad. Public opinion was,

however, beginning to be roused, and the canal companies began at

length to feel alarmed.

"At Manchester," Mr. James wrote to Mr. Sandars,

"the subject

engages all men's thoughts, and it is curious as well as amusing to

hear their conjectures. The canal companies (southward) are alive to

their danger. I have been the object of their persecution and hate;

they would immolate me if they could; but if I can die the death of

Samson, by pulling away the pillars, I am content to die with these

Philistines. Be assured, my dear sir, that not a moment shall be

lost, nor shall my attention for a day be diverted from this

concern, which increases in importance every hour, as well as in the

certainty of ultimate success."

Mr. James was one of the most enthusiastic of men, especially about

railways and locomotives. He believed, with Thomas Gray, who brought

out his book about this time, that railways were yet to become the

great high roads of civilization. The speculative character of the

man may be inferred from the following passage in one of his

letters to Mr. Sandars, written from London:

"Every Parliamentary friend I have seen—and I have many of both

houses—eulogizes our plan, and they are particularly anxious that

engines should be introduced in the south. I am now negotiating

about the Wandsworth Railroad. A fortune is to be made by buying the

shares, and introducing the engine system upon it. I am confident

capital will treble itself in two years. I do not choose to publish

my views here, and I wish to God some of our Liverpool friends

would take this advantage. I have bought some shares, but my capital

is locked up in unproductive lands and mines."

As the survey of the Liverpool and Manchester line proceeded, Mr.

James's funds fell short, and he was under the necessity of applying

to Mr. Sandars and his friends from time to time for farther

contributions. It was also necessary for him to attend to his

business as a surveyor in other parts of the country, and he was at

such times under the necessity of leaving the work to be done by his

assistants. Thus the survey was necessarily imperfect, and when the

time arrived for lodging the plans, it was found that they were

practically worthless. Mr. James's pecuniary difficulties had also

reached their climax. "The surveys and plans," he wrote to Mr. Sandars, "can't be completed, I see, till the end of the week. With

illness, anguish of mind, and inexpressible distress, I perceive I

must sink if I wait any longer; and, in short, I have so neglected

the suit in Chancery I named to you, that if I do not put in an

answer I shall be outlawed."

Mr. James's embarrassments increased, and he was unable to shake

himself free from them. He was confined for many months in the

Queen's Bench Prison, during which time this indefatigable railway

propagandist wrote an essay illustrative of the advantages of direct

inland communication by a line of engine railroad between London,

Brighton, and Portsmouth. Meanwhile the Liverpool and Manchester

scheme seemed to have fallen to the ground. But it only slept. When

its promoters found that they could no longer rely on Mr. James's

services, they determined to employ another engineer.

Mr. Sandars had by this time visited George Stephenson at

Killingworth, and, like all who came within reach of his personal

influence, was charmed with him at first sight. The energy which he

had displayed in carrying on the works of the Stockton and

Darlington Railway, now approaching completion; his readiness to

face difficulties, and his practical ability in overcoming them; the

enthusiasm which he displayed on the subject of railways and railway

locomotion, concurred in satisfying Mr. Sandars that he was, of all

men, the best calculated to help forward the undertaking at this

juncture; and having, on his return to Liverpool, reported this

opinion to the committee, they approved his recommendation, and

George Stephenson was unanimously appointed engineer of the

projected railway. On the 25th of May, 1824, Mr. Sandars wrote to

Mr. James as follows:

"I think it right to inform you that the committee have engaged your

friend George Stephenson. We expect him here in a few days. The

subscription-list for £300,000 is filled, and the Manchester

gentlemen have conceded to us the entire management. I very much

regret that, by delays and promises, you have forfeited the

confidence of the subscribers. I can not help it. I fear now that

you will only have the fame of being connected with the commencement

of this undertaking."

It will be observed that Mr. Sandars had held to his original

purpose with great determination and perseverance, and he gradually

succeeded in enlisting on his side an increasing number of

influential merchants and manufacturers both at Liverpool and

Manchester. Early in 1824 he published a pamphlet, in which he

strongly urged the great losses and interruptions to the trade of

the district by the delays in the forwarding of merchandise; and in

the same year he had a Public Declaration drawn up, and signed by

upward of 150 of the principal merchants of Liverpool, setting forth

that they considered "the present establishments for the transport

of goods quite inadequate, and that a new line of conveyance has

become absolutely necessary to conduct the increasing trade of the

country with speed, certainty, and economy."

A public meeting was then held to consider the best plan to be

adopted, and resolutions were passed in favour of a railroad. A

committee was appointed to take the necessary measures; but, as if

reluctant to enter upon their arduous struggle with the "vested

interests," they first waited on Mr. Bradshaw, the Duke of

Bridgewater's canal agent, in the hope of persuading him to increase

the means of conveyance, as well as to reduce the charges; but they

were met by an unqualified refusal. He would not improve the

existing means of conveyance; he would have nothing to do with the

proposed railway; and, if persevered in, he would oppose it with all

his power. The canal proprietors, confident in their imagined

security, ridiculed the proposed railway as a chimera. It had been

spoken about years before, and nothing had come of it then; it would

be the same now.

In order to form a better opinion as to the practicability of the

railroad, a deputation of gentlemen interested in the project

proceeded to Killingworth to inspect the engines which had been so

long in use there. They first went to Darlington, where they found

the works of the Stockton line in progress, though still unfinished.

Proceeding next to Killingworth with George Stephenson, they there

witnessed the performances of his locomotive engines. The result of

their visit was, on the whole, so satisfactory, that on their return

to Liverpool it was determined to form a company of the proprietors

for the construction of a double line of railway between Liverpool

and Manchester.

The original promoters of the undertaking included men the highest

standing and local influence in Liverpool and Manchester, with

Charles Lawrence as chairman. Lister Ellis, Robert Gladstone, John

Moss, and Joseph Sandars as deputy chairman; while among the

ordinary members of the committee were Robert Benson, James Cropper,

John Ewart, Wellwood Maxwell, and William Rathbone, of Liverpool,

and the brothers Birley, Peter Ewart, William Garnett, John Kennedy,

and William Potter, of Manchester.

The committee also included another important name—that of Henry

Booth, then a corn-merchant of Liverpool, and afterwards the

secretary and manager of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Mr.

Booth was a man of admirable business qualities, sagacious and

far-seeing, shrewd and practical, of considerable literary ability,

and he also possessed a knowledge of mechanics, which afterward

proved of the greatest value to the railway interest; for to him we

owe the suggestion of the multitubular boiler in the form in which

it has since been employed upon railways, and the coupling-screw, as

well as other important mechanical appliances which have come into

general use.

The first prospectus, issued in October, 1824, set forth in clear

and vigorous language the objects of the company, the urgent need of

additional means of communication between Liverpool and Manchester,

and the advantages offered by the railway over all other proposed

expedients. It was shown that the water-carriers not only exacted

the most arbitrary terms from the public but were positively unable

to carry the traffic requiring accommodation. Against the indefinite

continuance or recurrence of those evils, said the prospectus, the

public have but one security: "It is competition that is wanted; and

the proof of this assertion may be adduced from the fact that shares

in the Old Quay Navigation, of which the original cost was £70, have

been sold as high as £1250 each!" The advantages of the railway over

the canals for the carriage of coals was also urged, and it was

stated that the charge for transit would be very materially reduced.

"In the present state of trade and of commercial enterprise (the

prospectus proceeded), dispatch is no less essential than economy.

Merchandise is frequently brought across the Atlantic from New York

to Liverpool in twenty-one days, while, owing to the various causes

of delay above enumerated, goods have in some instances been longer

on their passage from Liverpool to Manchester. But this reproach

must not be perpetual. The advancement in mechanical science renders

it unnecessary—the good sense of the community makes it impossible. Let it not, however, be imagined that, were England to be tardy,

other countries would pause in the march of improvement. Application

has been made, on behalf of the Emperor of Russia, for models of the

locomotive engine; and other of the Continental governments have

been duly apprised of the important schemes for the facilitating of

inland traffic, now under discussion by the British public. In the

United States of America, also, they are fully alive to the

important results to be anticipated from the introduction of

railroads; a gentleman from the United States having recently

arrived in Liverpool, with whom it is a principal object to collect

the necessary information in order to the establishment of a railway

to connect the great rivers Potomac and Ohio."

It will be observed that the principal, indeed almost the sole,

object contemplated by the projectors of the undertaking was the

improved carriage of merchandise and coal, and that the conveyance

of passengers was scarcely calculated on, the only paragraph in the

prospectus relating to the subject being the following: "Moreover,

as a cheap and expeditious means of conveyance for travellers, the

railway holds out the fair prospect of a public accommodation, the

magnitude and importance of which can not be immediately

ascertained." The estimated expense of forming the line was set down

at £400,000—a sum which was eventually found quite inadequate. The

subscription list, when opened, was filled up without difficulty.

While the project was still under discussion, its promoters,

desirous of removing the doubts which existed as to the employment

of steam-power on the proposed railway, sent a second deputation to

Killingworth for the purpose of again observing the action of

Stephenson's engines. The cautious projectors of the railway were

not yet quite satisfied, and a third journey was made to

Killingworth in January, 1825, by several gentlemen of the

committee, accompanied by practical engineers, for the purpose of

being personal eye-witnesses of what steam-carriages were able to

perform upon a railway. There they saw a train, consisting of a

locomotive and loaded wagons, weighing in all 54 tons, travelling at

the average rate of about 7 miles an hour, the greatest speed being

about 9½ miles an hour. But when the engine was run with only one

wagon attached containing twenty gentlemen, five of whom were

engineers, the speed attained was from 10 to 12 miles an hour.

In the mean time the survey was proceeded with, in the face of great

opposition on the part of the proprietors of the lands through which

the railway was intended to pass. The prejudices of the farming and

labouring

classes were strongly excited against the persons employed upon the

ground, and it was with the greatest difficulty that the levels

could be taken. This opposition was especially manifested when the

attempt was made to survey the line through the properties of Lords

Derby and Sefton, and also where it crossed the Duke of

Bridgewater's Canal. At Knowsley, Stephenson and his surveyors were

driven off the ground by the keepers, and threatened with rough

handling if found there again. Lord Derby's farmers also turned out

their men to watch the surveying party, and prevent them entering on

any lands where they had the power of driving them off. Afterward

Stephenson suddenly and unexpectedly went upon the ground with a

body of surveyors and their assistants who outnumbered Lord Derby's

keepers and farmers, hastily collected to resist them, and this time

they were only threatened with the legal consequences of their

trespass.

The same sort of resistance was offered by Lord Sefton's keepers and

farmers, with whom the following ruse was adopted. A minute was

concocted, purporting to be a resolution of the Old Quay Canal

Company to oppose the projected railroad by every possible means,

and calling upon land-owners and others to afford every facility for

making such a survey of the intended line as should enable the

opponents to detect errors in the scheme of the promoters, and

thereby insure its defeat. A copy of this minute without any

signature, was exhibited by the surveyors who went upon the ground,

and the farmers, believing, them to have the sanction of the

landlords, permitted them to proceed with the hasty completion of

their survey.

The principal opposition, however, was experienced from Mr.

Bradshaw, the manager of the Duke of Bridgewater's canal property,

who offered a vigorous and protracted resistance to the survey in

all its stages. The duke's farmers obstinately refused permission to

enter upon their fields, although Stephenson offered to pay for any

damage that might be done. Mr. Bradshaw positively refused his

sanction in any case; and being a strict preserver of game, with a

large staff of keepers in his pay, he declared that he would order

them to shoot or apprehend any persons attempting a survey over his

property. But one moonlight night a survey was effected by the

following ruse. Some men, under the orders of the surveying party,

were set to fire off guns in a particular quarter, on which all the

gamekeepers on the watch made off in that direction, and they were

drawn away to such a distance in pursuit of the supposed poachers as

to enable a rapid survey to be made during their absence. Describing

before Parliament the difficulties which he encountered in making

the survey, Stephenson said: "I was threatened to be ducked in the

pond if I proceeded, and, of course, we had a great deal of the

survey to take by stealth, at the time when the people were at

dinner. We could not get it done by night; indeed, we were watched

day and night, and guns were discharged over the grounds belonging

to Captain Bradshaw to prevent us. I can state farther that I was

myself twice turned off Mr. Bradshaw's grounds by his men, and they

said if I did not go instantly they would take me up and carry me

off to Worsley."

The same kind of opposition had to be encountered all along the line

of the intended railway. Mr. Clay, one of the company's solicitors,

wrote to Mr. Sandars from the Bridgewater Arms, Prescott, on the

31st of December, that the landlords, occupiers, trustees of

turnpike roads, proprietors of bleach-works, carriers and carters,

and even the coal-owners, were dead against the railroad. "In a

word," said he, "the country is up in arms against us."

There were only three considerable land-owners who remained

doubtful; and "if these be against us," said Mr. Clay, "then the whole of the great

proprietors along the whole line are dissentient, excepting only Mr.

Trafford."

The cottagers and small proprietors were equally hostile. "The

trouble we have with them," wrote Mr. Clay, "is beyond belief; and

those patches of gardens at the end of Manchester bordering on the

Irwell, and the tenants of Hulme Hall, who, though insignificant,

must be seen, give us infinite trouble, all of which, as I have

reason to believe, is by no means accidental." There was

also the opposition of the great Bradshaw, the duke's agent "I wrote

you this morning," said Mr. Clay, in a wrathful letter of the same

date, "since which we have been into Bradshaw's warehouse, now

called the Knot Mill, and, after traversing two of the rooms, we got

very civilly turned out, which, under all the circumstances, I thought

very lucky, and more than we deserved. However, we have seen more

than half of his d—d cottagers."

There were also the canal companies, who made common cause, formed a

common purse, and determined to wage war to the knife against all

railways. The following circular, issued by the Liverpool Railroad

Company, with the name of Mr. Lawrence, the chairman, attached, will

serve to show the resolute spirit in which the canal proprietors

were preparing to resist the bill:

"SIR—The Leeds and

Liverpool, the Birmingham, the Grand Trunk, and other canal

companies having issued circulars, calling upon 'every canal and

navigation company in the kingdom' to oppose in limine

and by a united effort the establishment of railroads wherever

contemplated, I have most earnestly to solicit your active exertions

on behalf of the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad Company, to

counteract the avowed purpose of the canal proprietors, by exposing

the misrepresentations of interested parties, by conciliating good

will, and especially by making known, as far as you have

opportunity, not only the general superiority of railroads over

other modes of conveyance, but, in our peculiar case, the absolute

necessity of a new and additional line of communication, in order to

effect with economy and dispatch the transport of merchandise

between this port and Manchester.

"(Signed)

CHARLES LAWRENCE,

Chairman."

Such was the state of affairs and such the threatenings of war on

both sides immediately previous to the Parliamentary session of

1825.

When it became known that the promoters of the undertaking were

determined—imperfect though the plans were believed to be, from the

obstructions thrown in the way of the surveying parties—to proceed

with the bill in the next session of Parliament, the canal companies

appealed to the public through the press.

Pamphlets were published and newspapers hired to revile the railway. It was declared that its formation would prevent the cows grazing

and hens laying, while the horses passing along the road would be

driven distracted. The poisoned air from the locomotives would kill

the birds that flew over them, and render the preservation of

pheasants and foxes no longer possible. Householders adjoining the

projected line were told that their houses would be burnt up by the

fire thrown from the engine chimneys, while the air around would be

polluted by clouds of smoke. There would no longer be any use for

horses; and if railways extended, the species would become

extinguished, and oats and hay be rendered unsalable commodities.

Travelling by rail would be highly dangerous, and country inns would

be ruined. Boilers would burst and blow passengers to atoms.

But there was always this consolation to wind up with—that the

weight of the locomotive would completely prevent its moving, and

that railways, even if made, could never be worked by steam-power.

Although the press generally spoke of the Liverpool and Manchester

project as a mere speculation—as only one of the many bubble schemes

of the period—there were other writers who entertained different

views, and boldly and ably announced them [p.261]. Among the most

sagacious newspaper articles of the day, calling attention to the

application of the locomotive engine to the purposes of rapid

steam-travelling on railroads, was a series which appeared in 1824,

in the "Scotsman" newspaper, then edited by Mr. Charles Maclaren. In

those publications the wonderful powers of the locomotive were

logically demonstrated, and the writer, arguing from the experiments

on friction made more than half a century before by Vince and

Coulomb, which scientific men seemed to have altogether lost sight

of, clearly showed that, by the use of steam-power on railroads, the

cheaper as well as more rapid transit of persons and merchandise

might be confidently anticipated.

Not many years passed before the anticipations of the writer,

sanguine and speculative though they were at that tune regarded,

were amply realized. Even Mr. Nicholas Wood, in 1825, speaking of

the powers of the locomotive, and referring doubtless to the

speculations of the "Scotsman" as well as of his equally sanguine

friend Stephenson, observed: "It is far from my wish to promulgate

to the world that the ridiculous expectations, or rather

professions, of the enthusiastic speculist will be realized, and

that we shall see engines travelling at the rate of twelve, sixteen,

eighteen, or twenty miles an hour. Nothing could do more harm toward

their general adoption and improvement than the promulgation of such

nonsense." [p.262]

Among the papers left by Mr. Sandars we find a letter addressed to

him by Sir John Barrow, of the Admiralty, as to the proper method of

conducting the case in Parliament, which pretty accurately

represents the state of public opinion as to the practicability of

locomotive travelling on railroads at the time at which it was

written, the 10th of January, 1825. Sir John strongly urged Mr. Sandars to keep the locomotive altogether in the background; to rely

upon the proved inability of the canals and common roads to

accommodate the existing traffic; and to be satisfied with proving

the absolute necessity of a new line of conveyance; above all, he

recommended him not even to hint at the intention of carrying

passengers.

"You will at once," said he,

"raise a host of enemies in the

proprietors of coaches, post-chaises, innkeepers, etc., whose

interests will be attacked, and who, I have no doubt, will be

strongly supported, and for what? Some thousands of

passengers, you say—but a few hundreds I should say—in the year."

He accordingly urged that passengers as

well as speed should be

kept entirely out of the act; but, if the latter were insisted on,

then he recommended that it should be kept as low as possible—say at

five miles an

hour!

Indeed, when George Stephenson, at the interviews with counsel held

previous to the Liverpool and Manchester Bill going into Committee

of the House of Commons, confidently stated his expectation of being

able to run his locomotive at the rate of twenty miles an hour, Mr.

William Brougham, who was retained by the promoters to conduct their

case, frankly told him that if he did not moderate his views, and

bring his engine within a reasonable speed, he would "inevitably

damn the whole thing, and be himself regarded as a maniac fit only

for Bedlam."

Mail coach in a thunderstorm on Newmarket Heath,

Suffolk, 1827:

artist unknown.

The idea thrown out by Stephenson of travelling at a rate of speed

double that of the fastest mail-coach appeared at the time so

preposterous that he was unable to find any engineer who would risk

his reputation in supporting such "absurd views." Speaking of his

isolation at the time, he subsequently observed at a public meeting

of railway men in Manchester: "He remembered the time when he had

very few supporters in bringing out the railway system—when he

sought England over for an engineer to support him in his evidence

before Parliament, and could find only one man, James Walker, but

was afraid to call that gentleman, because he knew nothing about

railways. He had then no one to tell his tale to but Mr. Sandars, of

Liverpool, who did listen to him, and kept his spirits up; and his

schemes had at length been carried out only by dint of sheer

perseverance."

George Stephenson's idea was at that time regarded as but the dream

of a chimerical projector. It stood before the public friendless,

struggling hard to gain a footing, scarcely daring to lift itself

into notice for fear of ridicule. The civil engineers generally

rejected the notion of a Locomotive Railway; and when no leading man

of the day could be found to stand forward in support of the

Killingworth mechanic, its chances of success must indeed have been

pronounced but small.

When such was the hostility of the civil

engineers, no wonder the Reviewers were puzzled. The

"Quarterly," in an able article in support of the projected

Liverpool and Manchester Railway, while admitting its absolute necessity, and insisting that there was no

choice left but a railroad, on which the journey between Liverpool

and Manchester, whether performed by horses or engines, would always

be accomplished "within the day," nevertheless scouted the idea of

travelling at a greater speed than eight or nine miles an hour. Adverting to a project for forming a railway to Woolwich, by which

passengers were to be drawn by locomotive engines moving with twice

the velocity of ordinary coaches, the reviewer observed: "What can

be more palpably absurd and ridiculous than the prospect held out of

locomotives travelling twice as fast as stage-coaches! We would as

soon expect the people of Woolwich to suffer themselves to be fired

off upon one of Congreve's ricochet rockets, as trust themselves to

the mercy of such a machine going at such a rate. We will back old

Father Thames against the Woolwich Railway for any sum. We trust

that Parliament will, in all railways it may sanction, limit the

speed to eight or none miles an hour, which we entirely agree with

Mr. Silvester is as great as can be ventured on with safety."

――――♦――――

CHAPTER X.

PARLIAMENTARY CONTEST ON THE LIVERPOOL AND

MANCHESTER BILL.

THE Liverpool and Manchester Bill went into Committee of the House

of Commons on the 21st of March, 1825. There was an extraordinary

array of legal talent on the occasion, but especially on the side of

the opponents to the measure. Their wealth and influence enabled

them to retain the ablest counsel at the bar; Mr. (afterward Baron)

Alderson, Mr. Stephenson, Mr. (afterward Baron) Parke, Mr. Hose, Mr.

Macdonnell, Mr. Harrison, Mr. Erle, and Mr. Cullen, appeared for

various clients, who made common cause with each other in opposing

the bill, the case for which was conducted by Mr. Adam, Mr. Sergeant

Spankie, Mr. William Brougham, and Mr. Joy.

Evidence was taken at great length as to the difficulties and delays

in forwarding raw goods of all kinds from Liverpool to Manchester,

as also in the conveyance of manufactured articles from Manchester

to Liverpool. The evidence adduced in support of the bill on these

grounds was overwhelming. The utter inadequacy of the existing modes

of conveyance to carry on satisfactorily the large and

rapidly-growing trade between the two towns was fully proved. But

then came the main difficulty of the promoters' case—that of proving

the practicability of constructing a railroad to be worked by

locomotive power. Mr. Adam, in his opening speech, referred to the

cases of the Hetton and the Killingworth railroads, where heavy

goods were safely and economically transported by means of

locomotive engines. "None of the tremendous consequences," he

observed, "have ensued from the use of steam in land carriage that

have been stated. The horses have not started, nor the cows ceased

to give their milk, nor have ladies miscarried at the sight of these

things going forward at the rate of four miles and a half an hour."

Notwithstanding the petition of two ladies alleging the great danger

to be apprehended from the bursting of the locomotive boilers, he

urged the safety of the high-pressure engine when the boilers were

constructed of wrought iron; and as to the rate which they could travel, he expressed his full conviction that such engines "could

supply force to drive a carriage at the rate of five or six miles an

hour."

The taking of the evidence as to the impediments thrown in the way

of trade and commerce by the existing system extend over a month,

and it was the 21st of April before the committee went into the

engineering evidence, which was the vital part the question.

On the 25th George Stephenson was called into the witness box. It

was his first appearance before a committee of the House of Commons,

and he well knew what he had to expect. He was aware that the whole

force of the opposition was to be directed against him; and if they

could break down his evidence, the canal monopoly might yet be

upheld for a time. Many years afterward, when looking back at his

position on this trying occasion, he said:

"When I went to Liverpool

to plan a line from thence to Manchester, I pledged myself to the

directors to attain a speed of ten miles an hour. I said I had no

doubt the locomotive might be made to go much faster, but that we

had better be moderate at the beginning. The directors said I was

quite right; for that if, when they went to Parliament, I talked of

going a greater rate than ten miles an hour, I should put a cross up

the concern. It was not an easy task for me to keep the engine down

to ten miles an hour, but it must be done, and I did my best. I had

to place myself in that most unpleasant of all positions—the

witness-box of a Parliamentary committee. I was not long in it

before I began to wish for a hole to creep out at! I could not find

words to satisfy either the committee or myself. I was subjected to

the cross-examination of eight or ten barristers, purposely, as far

as possible, to bewilder me. Some member of the committee asked

if

I was a foreigner, [p.266]

another hinted that I was mad. But I

put up with every rebuff, and went on with my plans, determined not

to be put down."

George Stephenson stood before the committee to prove what the

public opinion of that day held to be impossible. The self-taught

mechanic had to demonstrate the practicability of accomplishing that

which the most distinguished engineers of the time regarded as

impracticable. Clear though the subject was to himself, and familiar

as he was with the powers of the locomotive, it was no easy task for

him to bring home his convictions, or even to convey his meaning, to

the less informed minds of his hearers. In his strong Northumbrian

dialect, he struggled for utterance, in the face of the sneers,

interruptions, and ridicule of the opponents of the measure, and

even of the committee, some of whom shook their heads and whispered

doubts as to his sanity when he energetically avowed that he could

make the locomotive go at the rate of twelve miles an hour! It was

so grossly in the teeth of all the experience of honourable members,

that the man ''must certainly be labouring under a delusion!"

And yet his large experience of railways and locomotives, as

described by himself to the committee, entitled this "untaught,

inarticulate genius," as he has been described, to speak with

confidence on the subject. Beginning with his experience as a brakesman at Killingworth in 1803, he went on to state that he was

appointed to take the entire charge of the steam-engines in 1813,

and had superintended the railroads connected with the numerous

collieries of the Grand Allies from that time downward. He had laid

down or superintended the railways at Burradon, Mount Moor,

Springwell, Bedlington, Hetton, and Darlington, besides improving

those at Killingworth, South Moor, and Derwent Crook. He had

constructed fifty-five steam-engines, of which sixteen were

locomotives. Some of these had been sent to France. The engines

constructed by him for the working of the Killingworth Railroad,

eleven years before, had continued steadily at work ever since, and

fulfilled his most sanguine expectations. He was prepared to prove

the safety of working high-pressure locomotives on a railroad, and the

superiority of this mode of transporting goods over all others. As

to

speed, he said he had recommended eight miles an hour with twenty

tons, and four miles an hour with forty tons; but he was quite

confident that much more might be done. Indeed, he had no doubt they

might go at the rate of twelve miles. As to the charge that

locomotives on a railroad would so terrify the horses in the

neighbourhood that to travel on horseback or to plough adjoining

fields would be rendered highly dangerous, the witness said that

horses learned to take no notice of them, though there were horses

that would shy at a wheelbarrow. A mail-coach was likely to be more

shied at by horses than a locomotive. In the neighbourhood of

Killingworth, the cattle in the fields went on grazing while the

engines passed them, and the farmers made no complaints.

Mr. Alderson, who had carefully studied the subject, and was well

skilled in practical science, subjected the witness to a protracted

and severe cross-examination as to the speed and power of the

locomotive, the stroke of the piston, the slipping of wheels upon

the rails, and various other points of detail. Stephenson insisted

that no slipping took place, as attempted to be extorted from him by

the counsel. He said, "It is impossible for slipping to take place

so long as the adhesive weight of the wheel upon the rail is greater

than the weight to be dragged after it." There was a good deal of

interruption to the witness's answers by Mr. Alderson, to which Mr.

Joy more than once objected. As to accidents, Stephenson knew of

none that had occurred with his engines. There had been one, he was

told, at the Middleton Colliery, near Leeds, with a Blenkinsop

engine. The driver had been in liquor, and put a considerable load

on the safety-valve, so that upon going forward the engine blew up

and the man was killed. But he added, if proper precautions had been

used with that boiler, the accident could not have happened. The

following cross-examination occurred in reference to the question of

speed:

"Of course," he was asked, "when a body is moving upon a road, the

greater the velocity the greater the momentum that is generated?"

"Certainly." "What would be the momentum of forty tons moving at the

rate of twelve miles an hour?" "It would be very great" "Have you

seen a railroad that would stand that?" "Yes." "Where?" "Any

railroad that would bear going four miles an hour: I mean to say,

that if it would bear the weight at four miles an hour, it would

bear it at twelve." "Taking it at four miles an hour, do you mean to

say that it would not require a stronger railway to carry the same

weight twelve miles an hour?" "I will give an answer to that. I dare

say every person has been over ice when skating, or seen persons go

over, and they know that it would bear them better at a greater

velocity than it would if they went slower; when they go quick, the

weight in a measure ceases." "Is not than upon the hypothesis that

the railroad is perfect?" "It is; and I mean to make it perfect."

It is not necessary to state that to have passed through his severe

ordeal scatheless needed no small amount of courage, intelligence,

and ready shrewdness on the part of the witness. Nicholas Wood, who

was present on the occasion, has since stated that the point on

which Stephenson was hardest pressed was that of speed. "I believe,"

he says, "that it would have lost the company their bill if he had

gone beyond eight or nine miles an hour. If he had stated his

intention of going twelve or fifteen miles an hour, not a single

person would have believed it to be practicable." Mr. Alderson had,

indeed, so pressed the point of "twelve miles an hour," and the

promoters were so alarmed lest it should appear in evidence that

they contemplated any such extravagant rate of speed, that

immediately on Mr. Alderson sitting down, Mr. Joy proceeded to

re-examine Stephenson, with the view of removing from the minds of

the committee an impression so unfavourable, and, as they supposed,

so damaging to their case. "With regard," asked Mr. Joy, "to all

those hypothetical questions of my learned friend, they have been

all put on the supposition of going twelve miles an hour: now that

is not the rate at which, I believe, any of the engines of which you

have spoken have travelled?" "No," replied Stephenson, "except as an

experiment for a short distance." "But what they have gone has been

three, five, or six miles an hour?" "Yes." "So that those

hypothetical cases of twelve miles an hour do not fall within your

general experience?" "They do not."

The committee also seem to have entertained some alarm as to the

high rate of speed which had been spoken of, and proceeded to

examine the witness farther on the subject. They supposed the case of

the engine being upset when going at nine miles an hour, and asked

what, in such a case, would become of the cargo astern. To which the

witness replied that it would not be upset. One of the members of

the committee pressed the witness a little farther. He put the

following case: "Suppose, now, one of these engines to be going

along a railroad at the rate of nine or ten miles an hour, and that

a cow were to stray upon the line and get in the way of the engine;

would not that, think you, be a very awkward circumstance?" "Yes,"

replied the witness, with a twinkle in his eye, "very awkward—for

the coo!" The honourable member did not proceed farther with his

cross-examination to use a railway phrase, he was " shunted." Another asked if animals would not be very much frightened by the

engine passing at night, especially by the glare of the red-hot

chimney? "But how would they know that it wasn't painted?" said the

witness.

On the following day (the 26th of April) the engineer was subjected

to a most severe examination. On that part of the scheme with which

he was most practically conversant, his evidence was clear and

conclusive. Now, he had to give evidence on the plans made by his

surveyors, and the estimates which had been founded on those plans. So long as he was confined to locomotive engines and iron railroads,

with the minutest details of which he was more familiar than any man

living, he felt at home and in his element. But when the designs of

bridges and the cost of constructing them had to be gone into, the

subject being comparatively new to him, his evidence was much less

satisfactory.

He was cross-examined as to the practicability of forming a road on

so unstable a foundation as Chat Moss.

" 'Now, with respect to your evidence upon Chat Moss,' asked Mr.

Alderson, 'did you ever walk on Chat Moss on the proposed line of

the railway?' 'The greater part of it, I have.'

" 'Was it not extremely boggy?' 'In parts it was.'

" 'How deep did you sink in?' 'I could have gone with shoes; I do

not know whether I had boots on.'

" 'If the depth of the Moss should prove to be 40 feet instead of

20, would not this plan of the railway over this Moss be

impracticable?' 'No, it would not. If the gentleman will allow me, I

will refer to a railroad belonging to the Duke of Portland, made

over a moss; there are no levels to drain it properly, such as we

have at Chat Moss, and it is made by an embankment over the moss,

which is worse than making a cutting, for there is the weight of the

embankment to press upon the moss.'

" 'Still, you must go to the bottom of the moss?' 'It is not

necessary; the deeper you get, the more consolidated it is.'

" 'Would you put some hard materials on it before you commenced?' 'Yes, perhaps I should.'

" 'What?' 'Brushwood, perhaps.'

" 'And you, then, are of opinion that it would be a solid

embankment?' 'It would have a tremulous motion for a time, but would

not give way, like clay.' "

Mr. Alderson also cross-examined him at great length on the plans of

the bridges, the tunnels, the crossings of the roads and streets,

and the details of the survey, which, it soon appeared, were in some

respects seriously at fault. It seems that, after the plans had been

deposited, Stephenson found that a much more favourable line might

be laid out, and he made his estimates accordingly, supposing that

Parliament would not confine the company to the precise plan which

had been deposited. This was felt to be a serious blot in the

Parliamentary case, and one very difficult to get over.

For three entire days was our engineer subjected to

cross-examination by Mr. Alderson, Mr. Cullen, and the other leading

counsel for the opposition. He held his ground bravely, and defended

the plans and estimates with remarkable ability and skill, but it

was clear they were imperfect, and the result was, on the whole,

damaging to the bill. Mr. (afterward Sir William) Cubitt was called

by the promoters, Mr. Adam stating that he proposed by this witness

to correct some of the levels as given by Stephenson. It seems a

singular course to have been taken by the promoters of the measure,

for Mr. Cubitt's evidence went to upset the statements made by

Stephenson as to the survey. This adverse evidence was, of course,

made the most of by the opponents of the scheme.

Mr. Sergeant Spankie then summed up for the bill on the 2d of May,

in a speech of great length, and the case of the opponents was next

gone into, Mr. Harrison opening with a long and eloquent speech on

behalf of his clients, Mrs. Atherton and others. He indulged in

strong vituperation against the witnesses for the bill, and

especially dwelt upon the manner in which Mr. Cubitt, for the

promoters, had proved that Stephenson's levels were wrong.

"They got a person," said he,

"whose character and skill I do not

dispute, though I do not exactly know that I should have gone to the

inventor of the treadmill as the fittest man to take the levels of Knowsley Moss and Chat Moss, which shook almost as much as a

treadmill, as you recollect, for he (Mr. Cubitt) said Chat Moss

trembled so much under his feet that he could not take his

observations accurately. . . . . In fact, Mr. Cubitt did not go on

to Chat Moss, because he knew that it was an immense mass of pulp,

and nothing else. It actually rises in height, from the rain

swelling it like a sponge, and sinks again in dry weather; and if a

boring instrument is put into it, it sinks immediately by its own

weight. The making of an embankment out of this pulpy, wet moss is

no very easy task. Who but Mr. Stephenson would have thought of

entering into Chat Moss, carrying it out almost like wet dung? It is

ignorance almost inconceivable. It is perfect madness, in a person

called upon to speak on a scientific subject, to propose such a

plan. . . . . Every part of the scheme shows that this man has

applied himself to a subject of which he has no knowledge, and which

he has no science to apply."

Then, adverting to the proposal to work the intended line by means

of locomotives, the learned gentleman proceeded:

"When we set out with the original prospectus, we were to gallop I

know not at what rate—I believe it was at the rate of twelve miles

an hour. My learned friend, Mr. Adam, contemplated—possibly alluding

to Ireland—that some of the Irish members would arrive in the wagons

to a division. My learned friend says that they would go at the rate

of twelve miles an hour with the aid of the devil in the form of a

locomotive sitting as postillion on the fore horse, and an

honourable member sitting behind him to stir up the fire, and keep

it at full speed. But the speed at which these locomotive engines

are to go has slackened: Mr. Adam does not go faster now than five

miles an hour. The learned sergeant (Spankie) says he should like to

have seven, but he would be content to go six. I will show he can

not go six; and probably, for any practical purposes, I may be able

to show that I can keep up with him by the canal . . . . . Locomotive

engines are liable to be operated upon by the weather. You are told

they are affected by rain, and an attempt has been made to cover

them; but the wind will affect them; and any gale of wind which

would affect the traffic on the Mersey would render it impossible to

set off a locomotive engine, either by poking of the fire, or

keeping up the pressure of the steam till the boiler was ready to

burst."

How amusing it now is to read these extraordinary views as to the

formation of a railway over Chat Moss, and the impossibility of

starting a locomotive engine in the face of a gale of wind?

Evidence was called to show that the house property passed by the

proposed railway would be greatly deteriorated—in some places almost

destroyed; that the locomotive engines would be terrible nuisances,

in consequence of the fire and smoke vomited forth by them; and that

the value of land in the neighbourhood of Manchester alone would be

deteriorated by no less than £20,000! Evidence was also given at

great length showing the utter impossibility of forming a road of

any kind upon Chat Moss. A Manchester builder, who was examined,

could not imagine the feat possible, unless by arching it across in

the manner of a viaduct from one side to the other. It was the old

story of "nothing like leather." But the opposition mainly relied

upon the evidence of the leading engineers—not, like Stephenson,

self-taught men, but regular professionals. Mr. Francis Giles, C.E.,

was their great card. He had been twenty-two years an engineer, and

could speak with some authority. His testimony was mainly directed

to the otter impossibility of forming a railway over Chat Moss. "No

engineer in his senses," said he, "would go through Chat Moss if

he wanted to make a railroad from Liverpool to Manchester. In my

judgment, a railroad certainly can not be safely made over Chat

Moss without going to the bottom of the Moss." The following may

be taken as a specimen of Mr. Giles's evidence:

"'Tell us whether, in your judgment, a railroad can be safely made

over Chat Moss without going to the bottom of the bog?' 'I say,

certainly not.'

"'Will it be necessary, therefore, in making a permanent railroad,

to take out the whole of the moss to the bottom, along the whole

line of road?' 'Undoubtedly.'

"'Will that make it necessary to cut down the thirty-three or

thirty-four feet of which you have been speaking?' 'Yes.'

"'And afterward to fill it up with other soil?' 'To such height as

the railway is to be carried; other soil mixed with a portion of the

moss.'

"'But suppose they were to work upon this stuff, could they get

their carriages to this place?' 'No carriage can stand on the

Moss short of the bottom.'

"'What could they do to make it stand—laying planks, or something

of that sort?' 'Nothing would support it.'

"'So that, if you would carry a railroad over this fluid stuff—if

you could do it, it would still take a great number of men and a

great sum of money. Could it be done, in your opinion, for £6000?'

'I should say £200,000 would not get through it.'

"'My learned friend wishes to know what it would cost to lay it

with diamonds?'"

Mr. H. R. Palmer, C.E., gave evidence to prove that resistance to a

moving body going under four and a quarter miles an hour was less upon a

canal than upon a railroad; and that, when going against a strong

wind, the progress of a locomotive was retarded "very much." Mr.

George Leather, C.E., the engineer of the Croydon and Wandsworth

Railway, on which he said the wagons went at from two and a half to

three miles an hour, testified against the practicability of

Stephenson's plan. He considered his estimate a "very wild" one. He

had no confidence in locomotive power. The Weardale Railway, of

which he was engineer, had given up the use of locomotive engines. He supposed that, when used, they travelled at three and a half to

four miles an hour, because they were considered to be then more

effective than at a higher speed.

When these distinguished engineers had given their evidence, Mr.

Alderson summed up in a speech which extended over two days. He

declared Stephenson's plan to be "the most absurd scheme that ever

entered into the head of man to conceive:"

"My learned friends," said he,

"almost endeavoured to stop my

examination; they wished me to put in the plan, but I had rather

have the exhibition of Mr. Stephenson in that box. I say he never

had one—I believe he never had one—I do not believe he is capable of

making one. His is a mind perpetually fluctuating between opposite

difficulties: he neither knows whether he is to make bridges over

roads or rivers of one size or of another, or to make embankments,

or cuttings, or inclined planes, or in what way the thing is to be

carried into effect. Whenever a difficulty is pressed, as in the

case of a tunnel, he gets out of it at one end, and when you try to

catch him at that, he gets out at the other.''

Mr. Alderson proceeded to declaim against the gross ignorance of

this so-called engineer, who proposed to make "impossible ditches by

the side of an impossible railway" over Chat Moss; and he contrasted

with his evidence that given "by that most respectable gentleman we

have called before you, I mean Mr. Giles, who has executed a vast

number of works," etc. Then Mr. Giles's evidence as to the

impossibility of making any railway over the Moss that would stand

short of the bottom was emphatically dwelt upon; and Mr. Alderson

proceeded:

"Having now, sir, gone through Chat Moss, and having shown that Mr.

Giles is right in his principle when he adopts a solid railway—and I

care not whether Mr. Giles is right or wrong in his estimate, for

whether it be effected by means of piers raised up all the way for

four miles through Chat Moss, whether they are to support it on

beams of wood or by erecting masonry, or whether Mr. Giles shall put

a solid bank of earth through it—in all these schemes there is not

one found like that of Mr. Stephenson's, namely, to cut impossible

drains on the side of this road; and it is sufficient for me to

suggest, and to show, that this scheme of Mr. Stephenson's is

impossible or impracticable, and that no other scheme, if they

proceed upon this line, can be suggested which will not produce

enormous expense. I think that has been irrefragably made out. Every

one knows Chat Moss—every one knows that Mr. Giles speaks correctly

when he says the iron sinks immediately on its being put upon the

surface. I have heard of culverts which have been put open the Moss,

which, after having been surveyed the day before, have the next

morning disappeared; and that a house (a poet's house, who may be

supposed in the habit of building castles even in the air), story

after story, as fast as one is added, the lower one sinks! There is

nothing, it appears, except long sedgy grass, and a little soil, to

prevent its sinking into the shades of eternal night. I have now

done, sir, with Chat Moss, and there I leave this railroad."

Mr. Alderson, of course, called upon the committee to reject the

bill; and he protested "against the despotism of the Exchange at

Liverpool striding across the land of this country. I do protest,"

he concluded, "against a measure like this, supported as it is by

such evidence, and founded upon such calculations."

The case of the other numerous petitioners against the bill still

remained to be gone into. Witnesses were called to prove the

residential injury which would be caused by the "intolerable

nuisance" of the smoke and fire from the locomotives, and others to

prove that the price of coals and iron would "infallibly" be greatly

raised throughout the country. This was part of the case of the Duke

of Bridgewater's trustees, whose witnesses "proved" many very

extraordinary things. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company were so

fortunate as to pick up a witness from Hetton who was ready to

furnish some damaging evidence as to the use of Stephenson's

locomotives on that railway. This was Mr. Thomas Wood, one of the Hetton Company's clerks, whose evidence was to the effect that the

locomotives, having been found ineffective, were about to be

discontinued in favour of fixed engines. The evidence of this

witness, incompetent though he was to give an opinion on the

subject, and exaggerated as his statements were afterward proved to

be, was made the most of by Mr. Harrison when summing up the case of

the canal companies.

"At length," he said,

"we have come to this—having first set out at

twelve miles an hour, the speed of these locomotives is reduced to

six, and now comes down to two or two and a half. They must be

content to be pulled along by horses and donkeys; and all those fine

promises of galloping along at the rate of twelve miles an hour are

melted down to a total failure; the foundation on which their case

stood is cut from under them completely; for the Act of Parliament,

the committee will recollect, prohibits any person using any animal

power, of any sort, kind, or description, except the projectors of

the railway themselves; therefore I say that the whole foundation on

which this project exists is gone."

After farther personal abuse of Mr. Stephenson, whose evidence he

spoke of as "trash and confusion," Mr. Harrison closed the case of

the canal companies on the 30th of May. Mr. Adam replied for the

promoters, recapitulating the principal point of their case, and

vindicating Mr. Stephenson and the evidence which he had given

before the committee.

The committee then divided on the preamble, which

was carried by a majority of only one—thirty-seven voting for it, and thirty-six

against it. The clauses were next considered, and on a division, the

first clause, empowering the company to make the railway, was lost

by a majority of nineteen to thirteen. In like manner, the next

clause, empowering the company to take land, was lost; on which Mr.

Adam, on the part of the promoters, withdrew the bill.

Thus ended this memorable contest, which had extended over two

months—carried on throughout with great pertinacity and skill,

especially on the part of the opposition, who left no stone unturned

to defeat the measure. The want of a new line of communication

between Liverpool and Manchester had been clearly proved; but the

engineering evidence in support of the proposed railway having been

thrown almost entirely upon George Stephenson, who fought this, the

most important part of the battle, single-handed, was not brought

out so clearly as it would have been had he secured more efficient

engineering assistance, which he was not able to do, as all the

engineers of eminence of that day were against the locomotive

railway. The obstacles thrown in the way of the survey by the

land-owners and canal companies, by which the plans were rendered

exceedingly imperfect, also tended in a great measure to defeat the

bill.

Mr. Gooch says the rejection of the scheme was probably the most

severe trial George Stephenson underwent in the whole course of his

life. The circumstances connected with the defeat of the bill, the

errors in the levels, his severe cross-examination, followed by the

fact of his being superseded by another engineer, all told fearfully

upon him, and for some time he was as terribly weighed down as if a

personal calamity of the most serious kind had befallen him. It is

also right to add that he was badly served by his surveyors, who

were unpractised and incompetent. On the 27th of September, 1824, we

find him writing to Mr. Sandars: "I am quite shocked with Auty's

conduct; we must throw him aside as soon as possible. Indeed, I have

begun to fear that be has been fee'd by some of the canal

proprietors to make a botch of the job. I have a letter from Steele,

[p.277] whose views of Auty's conduct quite agree with yours."

The result of this first application to Parliament was so far

discouraging. Stephenson had been so terribly abused by the leading

counsel for the opposition in the course of the proceedings before

the committee—stigmatized by them as an ignoramus, a fool, and a

maniac—that even his friends seem for a time to have lost faith in

him and in the locomotive system, whose efficiency he continued to

uphold. Things never looked blacker for the success of the railway

system than at the close of this great Parliamentary struggle. And

yet it was on the very eve of its triumph.

The Committee of Directors appointed to watch the measure in

Parliament were so determined to press on the project of a railway,

even though it should have to be worked merely by horse-power, that

the bill had scarcely been defeated ere they met in London to

consider their next step. They called their Parliamentary friends

together to consult as to their future proceedings. Among those who

attended the meeting of gentlemen with this object in the Royal

Hotel, St. James's Street, on the 4th of June, were Mr. Huskisson,

Mr. Spring Rice, and General Gascoyne. Mr. Huskisson urged the

promoters to renew their application to Parliament. They had secured

the first step by the passing of their preamble; the measure was of

great public importance; and, whatever temporary opposition it might

meet with, he conceived that Parliament must ultimately give its

sanction to the undertaking. Similar views were expressed by other

speakers; and the deputation went back to Liverpool determined to

renew their application to Parliament in the ensuing season.

It was not considered desirable to employ George Stephenson in

making the new survey. He had not as yet established his reputation

beyond the boundaries of his own district, and the promoters of the

bill had doubtless felt the disadvantages of this in the course of

their Parliamentary struggle. They then resolved now to employ

engineers of the highest established reputation, as well as the best

surveyors that could be obtained. In accordance with these views,

they engaged Messrs. George and John Rennie to be the engineers of

the railway; and Mr. Charles Vignolles, on their behalf, was

appointed to prepare the plans and sections. The line which was

eventually adopted differed somewhat from that surveyed by

Stephenson, entirely avoiding Lord Sefton's property, and passing

through only a few detached fields of Lord Derby's at a considerable

distance from the Knowsley domain. The principal parks and game

preserves of the district were also carefully avoided. The promoters

thus hoped to get rid of the opposition of the most influential of

the resident land-owners. The crossing of certain of the streets of

Liverpool were also avoided, and the entrance contrived by means of

a tunnel and an inclined plane. The new line stopped short of the

River Irwell at the Manchester end, and thus, in some measure,

removed the objections grounded on an anticipated interruption to

the canal or river traffic. And, with reference to the use of the

locomotive engine, the promoters, remembering with what effect the

objections to it had been urged by the opponents of the measure,

intimated, in their second prospectus, that, "as a guarantee of

their good faith toward the public, they will not require any clause

empowering them to use it; or they will submit to such restrictions

in the employment of it as Parliament may impose, for the

satisfaction and ample protection both of proprietors on the line of

road and of the public at large."

It was found that the capital required to form the line of railway,

as laid out by the Messrs. Rennie, was considerably beyond the

amount of Stephenson's estimate, and it became a question with the

committee in what way the new capital should be raised. A proposal

was made to the Marquis of Stafford, who was principally interested

in the Duke of Bridgewater's Canal, to become a shareholder in the

undertaking. A similar proposal had at an earlier period been made

to Mr. Bradshaw, the trustee for the property; but his answer was

"all or none,'' and the negotiation was broken off. The Marquis of

Stafford, however, now met the projectors of the railway in a more

conciliatory spirit, and it was ultimately agreed that he should

become a subscriber to the extent of a thousand shares.

The survey of the new line having been completed, the plans were

deposited, the standing orders duly complied with, and the bill went

before Parliament. The same counsel appeared for the promoters, but

the examination of witnesses was not nearly so protracted as on the

former occasion. Mr. Erle and Mr. Harrison led the case of the

opposition. The bill went into committee on the 6th of March, and on

the 16th the preamble was declared proved by a majority of

forty-three to eighteen. On the third reading in the House of

Commons, an animated, and what now appears a very amusing

discussion, took place. The Hon. Edward Stanley (since Earl of

Derby, and prime minister) moved that the bill be read that day six

months. In the course of his speech he undertook to prove that

the railway trains would take ten hours on the journey, and that they

could only be worked by horses; and he called upon the House to stop

the bill, "and prevent this mad and extravagant speculation from

being carried into effect." Sir Isaac Coffin seconded the motion,

and in doing so denounced the project as a most flagrant imposition. He would not consent to see widows' premises and their

strawberry-beds invaded; and "what, he would like to know, was to be

done with all those who had advanced money in making and repairing

turnpike roads? What with those who may still wish to travel in

their own or hired carriages, after the fashion of their

forefathers? What was to become of coach-makers and harness-makers,

coach-masters and coachmen, innkeepers, horse-breeders, and

horse-dealers? Was the House aware of the smoke and the noise, the

hiss and the whirl, which locomotive engines, passing at the rate of

ten or twelve miles an hour, would occasion? Neither the cattle ploughing in the fields or grazing in the meadows could behold them

without dismay. Iron would be raised in price 100 per cent., or more

probably exhausted altogether! It would be the greatest nuisance,

the most complete disturbance of quiet and comfort in all parts of

the kingdom that the ingenuity of man could invent!"

Mr. Huskisson and other speakers, though unable to reply to such

arguments as these, strongly supported the bill, and it was carried

on the third reading by a majority of eighty-eight to forty-one. The

bill passed the House of Lords almost unanimously, its only

opponents being the Earl of Derby and his relative the Earl of

Wilton. The cost of obtaining the act amounted to the enormous sum

of £27,000.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XI.

CHAT MOSS-CONSTRUCTION OF THE RAILWAY.

THE

appointment of principal engineer of the railway was taken into

consideration at the first meeting of the directors held at

Liverpool subsequent to the passing of the act of incorporation. The

magnitude of the proposed works, and the vast consequences involved

in the experiment, were deeply impressed on their minds, and they

resolved to secure the services of a resident engineer of proved

experience and ability. Their attention was naturally directed to

George Stephenson; at the same time, they desired to have the

benefit of the Messrs. Rennie's professional assistance in

superintending the works. Mr. George Rennie had an interview with

the board on the subject, at which he proposed to undertake the

chief superintendence, making six visits in each year, and

stipulating that he should have the appointment of the resident

engineer. But the responsibility attaching to the direction in the

matter of the efficient carrying on of the works would not admit of

their being influenced by ordinary punctilios on the occasion, and

they accordingly declined Mr. Rennie's proposal, and proceeded to

appoint George Stephenson principal engineer at a salary of £1000

per annum.

He at once removed his residence to Liverpool, and made arrangements

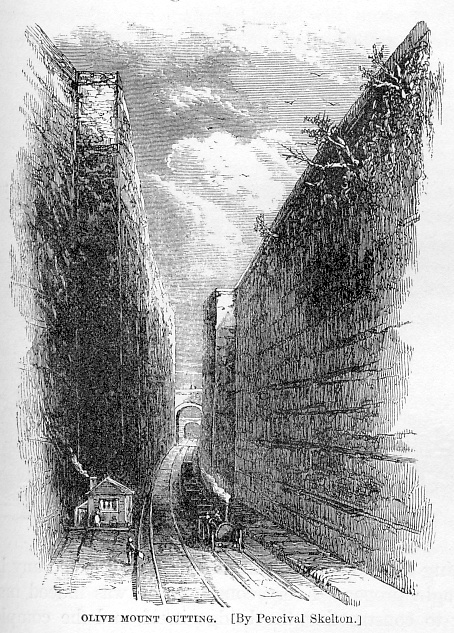

to commence the works. He began with the "impossible thing"—to do

that which some of the principal engineers of the day had declared

that "no man in his senses would undertake to do"—namely, to make

the road over Chat Moss! It was, indeed, a most formidable

undertaking, and the project of carrying a railway along, under, or

over such a material as that of which it consisted would certainly

never have occurred to an ordinary mind. Michael Drayton supposed

the Moss to have had its origin at the Deluge. Nothing more

impassable could have been imagined than that dreary waste; and Mr.

Giles only spoke the popular feeling of the day when he declared

that no carriage could stand on it "short of the bottom." In

this bog, singular to say, Mr. Roscoe, the accomplished historian of

Medicis, buried his fortune in the hopeless attempt to cultivate a

portion of it which he had bought.

Chat Moss is an immense peat-bog of about twelve square miles

in extent. Unlike the bogs or swamps of Cambridge and

Lincolnshire, which consist principally of soft mud or silt, this

bog is a vast mass of spongy vegetable pulp, the result of the

growth and decay of ages. Spagni, or bog-mosses, cover the

entire area; one year's growth rising over another, the older

growths not entirely decaying, but remaining partially preserved by

the antiseptic properties peculiar to peat. Hence the

remarkable fact that, though a semi-fluid mass, the surface of Chat

Moss rises above the level of the surrounding country. Like a

turtle's back, it declines from the summit in every direction,

having from thirty to forty feet gradual slope to the solid land on

all sides. From the remains of trees, chiefly alder and birch,

which have been dug out of it, and which must have previously

flourished on the surface of the soil now deeply submerged, it is

probable that the sand and clay base on which the bog rests is

saucer-shaped, and so retains the entire mass in position. In

rainy weather, such is its capacity for water that it sensibly

swells, and rises in those parts where the moss is the deepest.

This occurs through the capillary attraction of the fibres of the

submerged moss, which is from twenty to thirty feet in depth, while

the growing plants effectually check evaporation from the surface.

This peculiar character of the Moss has presented an insuperable

difficulty in the way of draining on any extensive system—such as by

sinking shafts in its substance, and pumping up the water by

steam-power, as has been proposed by some engineers. For,

supposing a shaft of thirty feet deep to be sunk, it has been

calculated that this would only be effectual for draining a circle

of about one hundred yards, the water running down an incline of

about 5 to 1; indeed, it was found, in the course of draining the

bog, that a ditch three feet deep only served to drain a space of

less than five yards on either side, and two ditches of this depth,

ten feet apart, left a portion of the Moss between them scarcely

affected by the drains.

The three resident engineers selected by Mr. Stephenson to

superintend the construction of the line were Mr. Joseph Locke, Mr.

Allcard, and Mr. John Dixon. The last was appointed to that

portion which included the proposed road across the Moss, the other

two being any thing but desirous of exchanging posts with him.

On Mr. Dixon's arrival, about the month of July, Mr. Locke proceeded

to show him over the length he was to take charge of, and to install

him in office. When they reached Chat Moss, Mr. Dixon found

that the line had already been staked out and the levels taken in

detail by the aid of planks laid upon the bog. The cutting of

the drains along each side of the proposed road had also been

commenced, but the soft pulpy stuff had up to this time flowed into

the drains and filled them up as fast as they were cut.

Proceeding across the Moss on his first day's inspection, the new

resident, when about half way over, slipped off the plank on which

he walked, and sank to his knees in the bog. Struggling only

sent him the deeper, and he might have disappeared altogether but

for the workmen, who hastened to his assistance upon planks, and

rescued him from his perilous position. Much disheartened, he

desired to return, and even for the moment thought of giving up the

job; but Mr. Locke assured him that the worst part was now past; so

the new resident plucked up heart again, and both floundered on

until they reached the farther edge of the Moss, wet and plastered

over with bog sludge. Mr. Dixon's assistants endeavoured to

comfort him by the assurance that he might in future avoid similar

perils by walking upon "pattens," or boards fastened to the soles of

his feet, as they had done when taking the levels, and as the