|

Previous to the letting of the contract, the character of the

underground soil was fairly tested by trial shafts, which indicated

that it consisted of shale of the lower oolite, and the works were

let accordingly. But they had scarcely been commenced when it

was discovered that, at an interval between the two trial-shafts,

which had been sunk about two hundred yards from the south end of

the tunnel, there existed an extensive quicksand under a bed of clay

forty feet thick, which the borings had escaped in the most singular

manner. At the bottom of one of these shafts, the excavation

and building of the tunnel were proceeding, when the roof at one

part suddenly gave way, a deluge of water burst in, and the party of

workmen with the utmost difficulty escaped with their lives.

They were only saved by means of a raft, on which they were towed by

one of the engineers swimming with the rope in his mouth to the

lower end of the shaft, out of which they were safely lifted to the

daylight.

The works were of course at that point immediately stopped.

The contractor who had undertaken the construction of the tunnel was

so overwhelmed by the calamity that, though he was relieved by the

company from his engagement, he took to his bed and shortly after

died. Pumping-engines were erected for the purpose of draining

off the water, but for a long time it prevailed, and sometimes even

rose in the shaft. The question arose whether, in the face of

so formidable a difficulty, the works should be proceeded with or

abandoned. Robert Stephenson sent over to Alton Grange for his

father, and the two took serious counsel together. George was

in favour of pumping out the water from the top by powerful engines

erected over each shaft, until the water was fairly mastered.

Robert concurred in that view, and, although other engineers who

were consulted pronounced strongly against the practicability of the

scheme and advised the abandonment of the enterprise, the directors

authorized him to proceed, and powerful steam-engines were ordered

to be constructed and delivered without loss of time.

In the meantime Robert suggested to his father the expediency

of running a drift along the heading from the south end of the

tunnel, with the view of draining off the water in that way.

George said he thought it would scarcely answer, but that it was

worth a trial, at all events until the pumping-engines were got

ready. Robert accordingly gave orders for the drift to be

proceeded with. The excavators were immediately set to work,

and they had nearly reached the quicksand, when one day, while the

engineer, his assistants, and the workmen were clustered about the

open entrance of the drift-way, they heard a sudden roar as of

distant thunder. It was hoped that the water had burst in—for

all the workmen were out of the drift—and that the sand-bed would

now drain itself off in a natural way. Instead of which, very

little water made its appearance, and on examining the inner end of

the drift, it was found that the loud noise had been caused by the

sudden discharge into it of an immense mass of sand, which had

completely choked up the passage, and thus prevented the water from

draining off.

The engineer now found that nothing remained but to sink

numerous additional shafts over the line of the tunnel at the points

at which it crossed the quicksand, and endeavour to master the water

by sheer force of engines and pumps. The engines, which were

shortly erected, possessed an aggregate power of 160 horses; and

they went on pumping for eight months, emptying out an almost

incredible quantity of water. It was found that the water,

with which the bed of sand extending over many miles was charged,

was in a great degree held back by the particles of the sand itself,

and that it could only percolate through at a certain average rate.

It appeared in its flow to take a slanting direction to the suction

of the pumps, the angle of inclination depending upon the coarseness

or fineness of the sand, and regulating the time of the flow.

Hence the distribution of the pumping power at short intervals along

the line of the tunnel had a much greater effect than the

concentration of that power at any one place. It soon appeared

that the water had found its master. Protected by the pumps,

which cleared a space for engineering operations—carried on, as it

were, amid two almost perpendicular walls of water and sand on

either side—the workmen proceeded with the building of the tunnel at

numerous points. Every exertion was used to wall in the

dangerous parts as quickly as possible, the excavators and

bricklayers labouring night and day until the work was finished.

Even while under the protection of the immense pumping power above

described, it often happened that the bricks were scarcely covered

with cement ready for the setting ere they were washed quite clean

by the streams of water which poured from overhead. The men

were accordingly under the necessity of holding over their work

large whisks of straw and other appliances to protect the bricks and

cement at the moment of setting.

The quantity of water pumped out of the sand-bed during eight

months of this incessant pumping averaged two thousand gallons per

minute, raised from an average depth of 120 feet. It is

difficult to form an adequate idea of the bulk of water thus raised,

but it may be stated that if allowed to flow for three hours only,

it would fill a lake one acre square to the depth of one foot, and

if allowed to flow for an entire day it would fill the lake to over

eight feet in depth, or sufficient to float a vessel of a hundred

tons' burden. The water pumped out of the tunnel while the

work was in progress would be nearly equivalent to the contents of

the Thames at high water between London and Woolwich. It is a

curious circumstance, that notwithstanding the quantity of water

thus removed, the level of the surface in the tunnel was only

lowered about two and a half to three inches per week, showing the

vast area of the quicksand, which probably extended along the entire

ridge of land under which the railway passed.

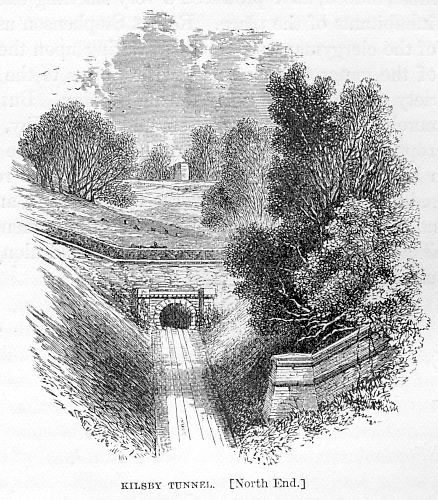

The cost of the line was greatly increased by the

difficulties thus encountered at Kilsby. The original estimate

for the tunnel was only £99,000; but by the time it was finished it

had cost about £100 per lineal yard forward, or a total of nearly

£300,000. The expenditure on the other parts of the line also

greatly exceeded the amount first set down by the engineer, and,

before the railway was complete, it had been more than doubled.

The land cost three times more than the estimate, and the claims for

compensation were enormous. Although the contracts were let

within the estimates, very few of the contractors were able to

finish them without the assistance of the company, and many became

bankrupt. Speaking of the difficulties encountered during the

construction of the line, Robert Stephenson subsequently observed to

us:

"After the works were let, wages rose, the prices of

materials of all kinds rose, and the contractors, many of whom were

men of comparatively small capital, were thrown on their beam-ends.

Their calculations as to expenses and profits were completely upset.

Let me just go over the list. There was Jackson, who took the

Primrose Hill contract—he failed. Then there was the next

length—Nowells; then Copeland and Harding; north of them Townsend,

who had the Tring cutting; next Norris, who had Stoke Hammond; then

Soars; then Hughes: I think all of these broke down, or at least

were helped through by the directors. Then there was that

terrible contract of the Kilsby Tunnel, which broke the Nowells, and

killed one of them. The contractors to the north of Kilsby

were more fortunate, though some of them pulled through only with

the greatest difficulty. Of the eighteen contracts in which

the line was originally let, only seven were completed by the

original contractors. Eleven firms were ruined by their

contracts, which were re-let to others at advanced prices, or were

carried on and finished by the company. The principal cause of

increase in the expense, however, was the enlargement of the

stations. It appeared that we had greatly under-estimated the

traffic, and it accordingly became necessary to spend more and more

money for its accommodation, until I think I am within the mark when

I say that the expenditure on this account alone exceeded by eight

or ten fold the amount of the Parliamentary estimate."

The magnitude of the works, which were unprecedented in

England, was one of the most remarkable features in the undertaking.

The following striking comparison has been made between this railway

and one of the greatest works of ancient times. The great

Pyramid of Egypt was, according to Diodorus Siculus, constructed by

three hundred thousand—according to Herodotus, by one hundred

thousand—men. It required for its execution twenty years, and

the labour expended upon it has been estimated as equivalent to

lifting 15,733,000,000 of cubic feet of stone one foot high;

whereas, if the labour expended in constructing the London and

Birmingham Railway be in like manner reduced to one common

denomination, the result is 25,000,000,000 of cubic feet more

than was lifted for the Great Pyramid; and yet the English work was

performed by about 20,000 men in less than five years. And

while the Egyptian work was executed by a powerful monarch

concentrating upon it the labour and capital of a great nation, the

English railway was constructed, in the face of every conceivable

obstruction and difficulty, by a company of private individuals out

of their own resources, without the aid of government or the

contribution of one farthing of public money.

The labourers who executed these formidable works were in

many respects a remarkable class. The "railway navvies," as

they were called, were men drawn by the attraction of good wages

from all parts of the kingdom; and they were ready for any sort of

hard work. [p.362]

Many of the labourers employed on the Liverpool line were Irish;

others were from the Northumberland and Durham railways, where they

had been accustomed to similar work; and some of the best came from

the fen districts of Lincoln and Cambridge, where they had been

trained to execute works of excavation and embankment. These

old practitioners formed a nucleus of skilled manipulation and

aptitude which rendered them of indispensable utility in the immense

undertakings of the period. Their expertness in all sorts of

earth-work, in embanking, boring, and well-sinking—their practical

knowledge of the nature of soils and rocks, the tenacity of clays,

and the porosity of certain stratifications—were very great; and,

rough-looking as they were, many of them were as important in their

own department as the contractor or the engineer.

During the railway-making period the navvy wandered about

from one public work to another, apparently belonging to no country

and having no home. He usually wore a white felt hat with the

brim turned up, a velveteen or jean square-tailed coat, a scarlet

plush waistcoat with little black spots, and a bright-coloured

kerchief round his Herculean neck, when, as often happened, it was

not left entirely bare. His corduroy breeches were retained in

position by a leathern strap round the waist, and were tied and

buttoned at the knee, displaying beneath a solid calf and foot

encased in strong high-laced boots. Joining together in a

"butty gang," some ten or twelve of these men would take a contract

to cut out and remove so much "dirt"—as they denominated

earth-cutting—fixing, their price according to the character of the

"stuff," and the distance to which it had to be wheeled and tipped.

The contract taken, every man put himself to his mettle; if any was

found skulking, or not putting forth his full working power, he was

ejected from the gang. Their powers of endurance were

extraordinary. In times of emergency they would work for

twelve and even sixteen hours, with only short intervals for meals.

The quantity of flesh-meat which they consumed was something

enormous; but it was to their bones and muscles what coke is to the

locomotive—the means of keeping up the steam. They displayed

great pluck, and seemed to disregard peril. Indeed, the most

dangerous sort of labour—such as working horse-barrow runs, in which

accidents are of constant occurrence—has always been most in request

among them, the danger seeming to be one of its chief

recommendations.

Working together, eating, drinking, and sleeping together,

and eating, and daily exposed to the same influences, these railway

labourers soon presented a distinct and well-defined character,

strongly marking them from the population of the districts in which

they laboured. Reckless alike of their lives as of their

earnings, the navvies worked hard and lived hard. For their

lodging, a but of turf would content them; and, in their hours of

leisure, the meanest public house would serve for their parlour.

Unburdened, as they usually were, by domestic ties, unsoftened by

family affection, and without much moral or religious training, the

navvies came to be distinguished by a sort of savage manners, which

contrasted strangely with those of the surrounding population.

Yet, ignorant and violent though they might be, they were usually

goodhearted fellows in the main—frank and open-handed with their

comrades, and ready to share their last penny with those in

distress. Their pay-nights were often a saturnalia of riot and

disorder, dreaded by the inhabitants of the villages along the line

of works. The irruption of such men into the quiet hamlet of

Kilsby must, indeed, have produced a very startling effect on the

recluse inhabitants of the place. Robert Stephenson used to

tell a story of the clergyman of the parish waiting upon the foreman

of one of the gangs to expostulate with him as to the shocking

impropriety of his men working during Sunday. But the head

navvy merely hitched up his trousers and said, "Why, Soondays hain't

cropt out here yet!" In short, the navvies were little better

than heathens, and the village of Kilsby was not restored to its

wonted quiet until the tunnel-works were finished, and the engines

and scaffolding removed, leaving only the immense masses of

débris around the line of shafts which extend along the top of

the tunnel.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XV.

MANCHESTER AND LEEDS, AND MIDLAND RAILWAYS—STEPHENSON'S LIFE AT

ALTON—VISIT TO BELGIUM—GENERAL EXTENSION OF RAILWAYS AND THEIR

RESULTS.

THE

rapidity with which railways were carried out, when the spirit of

the country became roused, was indeed remarkable. This was

doubtless in some measure owing to the increased force of the

current of speculation at the time, but chiefly to the desire which

the public began to entertain for the general extension of the

system. It was even proposed to fill up the canals and convert

them into railways. The new roads became the topic of

conversation in all circles; they were felt to give a new value to

time; their vast capabilities for "business" peculiarly recommended

them to the trading classes, while the friends of "progress" dilated

on the great benefits they would eventually confer upon mankind at

large. It began to be seen that Edward Pease had not been

exaggerating when he said, "Let the country but make the railroads,

and the railroads will make the country!" They also came to be

regarded as inviting objects of investment to the thrifty, and a

safe outlet for the accumulations of inert men of capital.

Thus new avenues of iron road were soon in course of formation,

branching in all directions, so that the country promised in a

wonderfully short space of time to become wrapped in one vast

network of iron.

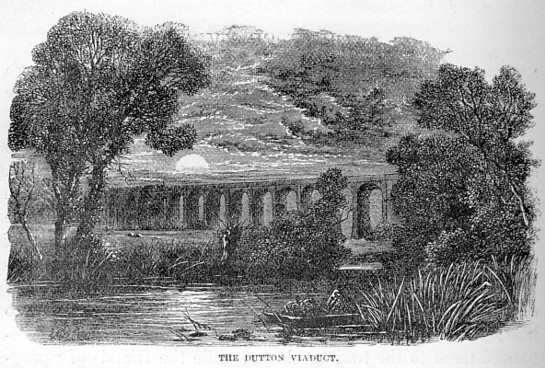

In 1836 the Grand Junction Railway was under construction

between Warrington and Birmingham—the northern part by Mr.

Stephenson, and the southern by Mr. Rastrick. The works on

that line embraced heavy cuttings, long embankments, and numerous

viaducts; but none of these are worthy of any special description.

Perhaps the finest piece of masonry on the railway is the Dutton

Viaduct across the valley of the Weaver. It consists of 20

arches of 60 feet span, springing 16 feet from the perpendicular

shaft of each pier, and 60 feet in height from the crown of the

arches to the level of the river. The foundations of the piers

were built on piles driven 20 feet deep. The structure has a

solid and majestic appearance, and is perhaps the finest of George

Stephenson's viaducts.

The Manchester and Leeds line was in progress at the same

time—an important railway connecting Yorkshire and Lancashire,

passing through a district full of manufacturing towns and villages,

the hives of population, industry, and enterprise. An attempt

was made to obtain the act as early as the year 1831, but its

promoters were defeated by the powerful opposition of the

land-owners, aided by the canal companies, and the project was not

revived for several years. The act authorizing the

construction of the line was obtained in 1836; it was amended in the

following year, and the first ground was broken on the 18th of

August, 1837.

An incident occurred while the second Manchester and Leeds

Bill was before the Committee of the Lords which is worthy of

passing notice in this place, as illustrative of George Stephenson's

character. The line which was authorized by Parliament in 1836

had been hastily surveyed within a period of less than six weeks,

but before it received the royal assent the engineer became

convinced that many important improvements might be made in it, and

he communicated his views to the directors. They determined,

however, to obtain the act, although conscious at the time that they

would have to go for a second and improved line in the following

year. The second bill passed the Commons in 1837 without

difficulty, and was expected in like manner to pass the Lords'

Committee. Quite unexpectedly, however, Lord Wharncliffe, who

was interested in the Manchester and Sheffield line, which passed

through his colliery property in the south of Yorkshire, conceiving

that the new Manchester and Leeds line might have some damaging

effect upon it, appeared as an opponent of the bill. Himself a

member of the committee, he adopted the unusual course of rising to

his feet, and making a set speech against the measure while the

engineer was under examination. He alleged that the act

obtained in the preceding session was one that the promoters had no

intention of carrying out, that they had only secured it for the

purpose of obtaining possession of the ground and reducing the

number of the opponents to their present application, and that, in

fact, they had been practicing a deception upon the House.

Then, turning full round upon the witness, he said, "I ask you, sir,

do you call that conduct honest?" Stephenson, his voice

trembling with emotion, replied, "Yes, my lord, I do call it

honest. And I will ask your lordship, whom I served for many

years as your engine-wright at the Killingworth collieries, did you

ever know me to do any thing that was not strictly honourable?

You know what the collieries were when I went there, and you know

what they were when I left them. Did you ever hear that I was

found wanting when honest services were wanted, or when duty called

me? Let your lordship but fairly consider the circumstances of

the case, and I feel persuaded you will admit that my conduct has

been equally honest throughout in this matter." He then

briefly but clearly stated the history of the application to

Parliament for the act, which was so satisfactory to the committee

that they passed the preamble of the bill without farther objection;

and Lord Wharncliffe requested that the committee would permit his

observations to be erased from the record of the evidence, which, as

an acknowledgment of his error, was allowed. Lord Kenyon and

several other members of the committee afterward came up to Mr.

Stephenson, shook him by the hand, and congratulated him on the

manly way in which he had vindicated himself from the aspersions

attempted to be cast upon him.

In conducting this project to an issue, the engineer had the

usual opposition and prejudices to encounter. Predictions were

confidently made in many quarters that the line could never succeed.

It was declared that the utmost engineering skill could not

construct a railway through such a country of hills and hard rocks;

and it was maintained that, even if the railway were practicable, it

could only be made at a cost altogether ruinous.

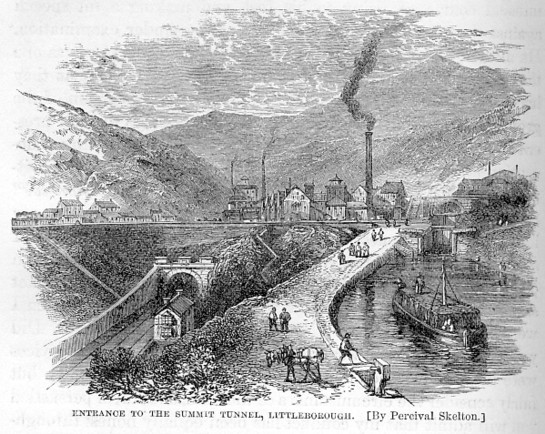

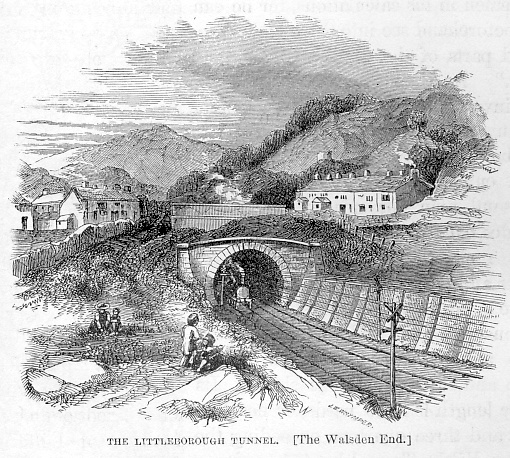

During the progress of the works, as the Summit Tunnel near

Littleborough was approaching completion, the rumour was spread

abroad in Manchester that the tunnel had fallen in and buried a

number of the workmen. The last arch had been keyed in, and

the work was all but finished, when a slight accident occurred which

was thus exaggerated by the lying tongue of rumour. An invert

had given way through the irregular pressure of the surrounding

earth and rock at a part of the tunnel where a "fault" had occurred

in the strata.

A party of the directors accompanied the engineer to inspect the

scene of the accident. They entered the tunnel mouth preceded

by upward of fifty navvies, each bearing a torch. After

walking a distance of about half a mile, the inspecting party

arrived at the scene of the "frightful accident," about which so

much alarm had been spread abroad. All that was visible was a

certain unevenness of the ground, which had been forced up by the

invert under it giving way; thus the ballast had been loosened, the

drain running along the centre of the road had been displaced, and

small pools of water stood about. But the whole of the walls

and the roof were as perfect as at any other part of the tunnel.

The engineer explained the cause of the accident; the blue shale, he

said, through which the excavation passed at that point, was

considered so hard and firm as to render it unnecessary to build the

invert very strong there. But shale is always a deceptive

material. Subjected to the influence of the atmosphere, it

gives but a treacherous support. In this case, falling away

like quicklime, it had left the lip of the invert alone to support

the pressure of the arch above, and hence its springing inward and

upward. Stephenson then directed the attention of the visitors

to the completeness of the arch overhead, where not the slightest

fracture or yielding could be detected. Speaking of the work

in the course of the same day, he said, "I will stake my character,

my head, if that tunnel ever give way, so as to cause danger to any

of the public passing through it. Taking it as a whole, I

don't think there is another such a piece of work in the world.

It is the greatest work that has yet been done of this kind, and

there has been less repairing than is usual—though an engineer might

well be beaten in his calculations, for he can not beforehand see

into those little fractured parts of the earth he may meet with."

As Stephenson had promised, the invert was put in, and the tunnel

was made perfectly safe.

The construction of this subterranean road employed the

labour of above a thousand men for nearly four years. Besides

excavating the arch out of the solid rock, they used 23,000,000 of

bricks and 8000 tons of Roman cement in the building of the tunnel.

Thirteen stationary engines, and about 100 horses, were also

employed in drawing the earth and stone out of the shafts. Its

entire length is 2869 yards, or nearly a mile and three quarters,

exceeding the famous Kilsby Tunnel by 471 yards.

The Midland Railway was a favourite line of Mr. Stephenson's

for several reasons. It passed through a rich mining district,

in which it opened up many valuable coal-fields, and it formed part

of the great main line of communication between London and

Edinburgh. The line was originally projected by gentlemen

interested in the London and Birmingham Railway. Their

intention was to extend that line from Rugby to Leeds; but, finding

themselves anticipated in part by the projection of the Midland

Counties Railway from Rugby to Derby, they confined themselves to

the district between Derby and Leeds, and in 1835 a company was

formed to construct the North Midland line, with George Stephenson

for its engineer. The act was obtained in 1836, and the first

ground was broken in February, 1837.

Although the Midland Railway was only one of the many great

works of the same kind executed at that time, it was almost enough

of itself to be the achievement of a life. Compare it, for

example, with Napoleon's military road over the Simplon, and it will

at once be seen how greatly it excels that work, not only in the

constructive skill displayed in it, but also in its cost and

magnitude, and the amount of labour employed in its formation.

The road of the Simplon is 45 miles in length; the North Midland

Railway 72½ miles. The former has 50 bridges and 5 tunnels,

measuring together 1338 feet in length; the latter has 200 bridges

and 7 tunnels, measuring together 11,400 feet, or about 2¼ miles.

The former cost about £720,000 sterling, the latter above

£3,000,000. Napoleon's grand military road was constructed in

six years, at the public cost of the two great kingdoms of France

and Italy, while Stephenson's railway was formed in about three

years by a company of private merchants and capitalists out of their

own funds and under their own superintendence.

It is scarcely necessary that we should give any account in

detail of the North Midland works. The making of one tunnel so

much resembles the making of another—the building of bridges and

viaducts, no matter how extensive, so much resembles the building of

others—the cutting out of "dirt," the blasting of rocks, and the

wheeling of excavation into embankments, is so much matter of mere

time and hard work, that it is quite unnecessary to detain the

reader by any attempt at their description. Of course there

were the usual difficulties to encounter and overcome, but the

railway engineer regarded these as mere matters of course, and would

probably have been disappointed if they had not presented

themselves.

On the Midland, as on other lines, water was the great enemy

to be fought against—water in the Clay-cross and other tunnels—water

in the boggy or sandy foundations of bridges—and in cuttings and

embankments. As an illustration of the difficulties of bridge

building, we may mention the case of the five-arch bridge over the

Derwent, where it took two years work, night and day, to get in the

foundations of the piers alone. Another curious illustration

of the mischief done by water in cuttings may be briefly mentioned.

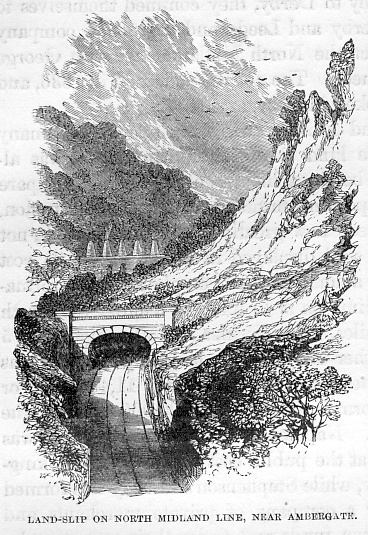

At a part of the North Midland line, near Ambergate, it was

necessary to pass along a hill-side in a cutting a few yards deep.

As the cutting proceeded, a seam of shale was cut across, lying at

an inclination of 6 to 1; and shortly after, the water getting

behind it, the whole mass of earth along the hill above began to

move down across the line of excavation. The accident

completely upset the estimates of the contractor, who, instead of

fifty thousand cubic yards, found that he had about five hundred

thousand to remove, the execution of this part of the railway

occupying fifteen months instead of two.

The Oakenshaw cutting near Wakefield was also of a very

formidable character. About six hundred thousand yards of rock

shale and bind were quarried out of it, and led to form the

adjoining Oakenshaw embankment. The Normanton cutting was

almost as heavy, requiring the removal of four hundred thousand

yards of the same kind of excavation into embankment and spoil.

But the progress of the works on the line was so rapid during 1839

that no less than 450,000 cubic yards of excavation were

accomplished per month.

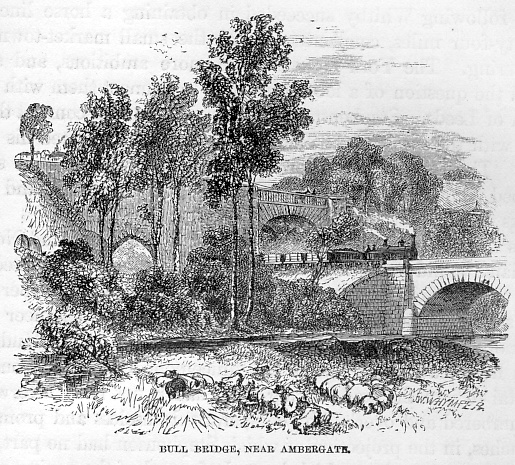

As a curiosity in construction, we may also mention a very

delicate piece of work executed on the same railway at Bull Bridge

in Derbyshire, where the line at the same point passes over a bridge

which here spans the River Amber, and under the bed of the Cromford

Canal. Water, bridge, railway, and canal were thus piled one

above the other, four stories high. In order to prevent the

possibility of the waters of the canal breaking in upon the railway

works, Stephenson had an iron trough made, 150 feet long, of the

width of the canal, and exactly fitting the bottom. It was

brought to the spot in three pieces, which were firmly welded

together, and the trough was then floated into its place and sunk,

the whole operation being completed without in the least interfering

with the navigation of the canal. The railway works underneath

were then proceeded with and finished.

Another line of the same series, constructed by George

Stephenson, was the York and North Midland, extending from

Normanton—a point on the Midland Railway—to York; but it was a line

of easy formation, traversing a comparatively level country.

The inhabitants of Whitby, as well as York, were projecting a

railway to connect these towns as early as 1832, and in the year

following Whitby succeeded in obtaining a horse line of twenty-four

miles, connecting it with the small market-town of Pickering.

The York citizens were more ambitious, and agitated the question of

a locomotive line to connect them with the town of Leeds.

Stephenson recommended them to connect their line with the Midland

at Normanton, and they adopted his advice. The company was

formed, the shares were at once subscribed for, the act was obtained

in the following year, and the works were constructed without

difficulty.

As the best proof of his conviction that the York and North

Midland would prove a good investment, Stephenson invested in it a

considerable portion of his savings, being a subscriber for 420

shares. The interest taken in this line by the engineer was on

more than one occasion specially mentioned by Mr. Hudson, then

Lord-mayor of York, as an inducement to other persons of capital to

join the undertaking; and had it not been afterward encumbered and

overlaid by comparatively useless and profitless branches, in the

projection of which Stephenson had no part, the sanguine

expectations which he early formed of the paying qualities of that

railway would have been more than realized.

There was one branch, however, of the York and North Midland

Line in which he took an anxious interest, and of which he may be

said to have been the projector—the branch to Scarborough, which

proved one of the most profitable parts of the railway. He was

so satisfied of its value, that, at a meeting of the York and North

Midland proprietors, he volunteered his gratuitous services as

engineer until the company was formed, in addition to subscribing

largely to the undertaking. At that meeting he took an

opportunity of referring to the charges brought against engineers of

so greatly exceeding the estimates: "He had had a good deal to do

with making out the estimate of the North Midland Railway, and he

believed there never was a more honest one. He had always

endeavoured to state the truth as far as was in his power. He

had known a contractor who, when he (Mr. Stephenson) had sent in an

estimate, came forward and said, 'I can do it for half the money.'

The contractor's estimate went into Parliament, but it came out his.

He could go through the whole list of the undertakings in which he

had been engaged, and show that he had never had any thing to do

with stock-jobbing concerns. He would say that he would not be

concerned in any scheme unless he was satisfied that it would pay

the proprietors; and in bringing forward the proposed line to

Scarborough, he was satisfied that it would pay, or he would have

had nothing to do with it."

During the time that our engineer was engaged in

superintending the execution of these undertakings, he was occupied

upon other projected railways in various parts of the country.

He surveyed several lines in the neighbourhood of Glasgow, and

afterward alternate routes along the east coast from Newcastle to

Edinburg, with the view of completing the main line of communication

with London. When out on foot in the field on these occasions,

he was ever foremost in the march, and he delighted to test the

prowess of his companions by a good jump at any hedge or ditch that

lay in their way. His companions used to remark his singular

quickness of observation. Nothing escaped his attention—the

trees, the crops, the birds, or the farmer's stock; and he was

usually full of lively conversation, everything in nature affording

him an opportunity for making some striking remark or propounding

some ingenious theory. When taking a flying survey of a new

line, his keen observation proved very useful, for he rapidly noted

the general configuration of the country, and inferred its

geological structure. He afterward remarked to a friend, "I

have planned many a railway travelling along in a post-chaise, and

following the natural line of the country." And it was

remarkable that his first impressions of the direction to be taken

almost invariably proved correct; and there are few of the lines

surveyed and recommended by him which have not been executed, either

during his lifetime or since. As an illustration of his quick

and shrewd observation on such occasions, we may mention that when

employed to lay out a line to connect Manchester, through

Macclesfield, with the Potteries, the gentleman who accompanied him

on the journey of inspection cautioned him to provide large

accommodation for carrying off the water, observing, "You must not

judge by the appearance of the brooks; for after heavy rains these

hills pour down volumes of water, of which you can have no

conception." "Pooh! pooh! don't I see your bridges?"

replied the engineer. He had noted the details of each as he

passed along.

Among the other projects which occupied his attention about

the same time were the projected lines between Chester and Holyhead,

between Leeds and Bradford, and between Lancaster and Maryport by

the west coast. This latter was intended to form part of a

western line to Scotland; Stephenson favouring it partly because of

the flatness of the gradients, and because it could be formed at

comparatively small cost, while it would open out a valuable

iron-mining district, from which a large traffic in ironstone was

expected. One of its collateral advantages, in the engineer's

opinion, was that, by forming the railway directly across Morecambe

Bay, on the northwest coast of Lancashire, a large tract of valuable

land might be reclaimed from the sea, the sale of which would

considerably reduce the cost of the works. He estimated that,

by means of a solid embankment across the bay, not less than 40,000

acres of rich alluvial land would be gained. He proposed to

carry the road across the ten miles of sands which lie between

Poulton, near Lancaster, and Humphrey Head on the opposite coast,

forming the line in a segment of a circle of five miles' radius.

His plan was to drive in piles across the entire length, forming a

solid fence of stone blocks on the land side for the purpose of

retaining the sand and silt brought down by the rivers from the

interior. The embankment would then be raised from time to

time as the deposit accumulated, until the land was filled up to

high-water mark; provision being made, by means of sufficient

arches, for the flow of the river waters into the bay. The

execution of the railway after this plan would, however, have

occupied more years than the promoters of the West Coast line were

disposed to wait, and eventually Mr. Locke's more direct but less

level line by Shap Fell was adopted. A railway has, however,

since been carried across the head of the bay, in a modified form,

by the Ulverstone and Lancaster Railway Company; and it is not

improbable that Stephenson's larger scheme of reclaiming the vast

tract of land now left bare at every receding tide may yet be

carried out.

While occupied in carrying out the great railway undertakings

which we have above so briefly described, George Stephenson's home

continued, for the greater part of the time, to be at Alton Grange,

near Leicester. But he was so much occupied in travelling

about from one committee of directors to another—one week in

England, another in Scotland, and probably the next in Ireland, that

he often did not see his home for weeks together. He had also

to make frequent inspections of the various important and difficult

works in progress, especially on the Midland and Manchester and

Leeds lines, besides occasionally going to Newcastle to see how the

locomotive works were going on there. During the three years

ending 1837—perhaps the busiest years of his life [p.377]—he

travelled by post-chaise alone upward of 20,000 miles, and yet not

less than six months out of the three years were spent in London.

Hence there is comparatively little to record of Mr. Stephenson's

private life at this period, during which he had scarcely a moment

that he could call his own.

To give an idea of the number of projects which at this time

occupied our engineer's attention, and of the extent and rapidity of

his journeys, we subjoin from his private secretary's journal the

following epitome of one of them, on which he entered immediately

after the conclusion of the heavy Parliamentary session of 1836.

"August 9th. From Alton Grange to Derby and

Matlock, and forward by mail to Manchester, to meet the committee of

the South Union Railway.

August l0th. Manchester to Stockport, to meet committee of

the Manchester and Leeds Railway; thence to meet directors of the

Chester and Birkenhead, and Chester and Crewe Railways.

August 11th. Liverpool to Woodside, to meet committee of the

Chester and Birkenhead line; journey with them along the proposed

railway to Chester; then back to Liverpool.

August 12th. Liverpool to Manchester, to meet directors of

the Manchester and Leeds Railway, and travelling with them over the

works in progress.

August 13th. Continued journey over the works, and arrival at

Wakefield; thence to York.

August 14th. Meeting with Mr. Hudson at York, and journey

from York to Newcastle.

August 15th. At Newcastle, working up arrears of

correspondence.

August 16th. Meeting with Mr. Brandling as to the station for

the Brandling Junction at Gateshead, and stations at other parts of

the line.

August 17th. Carlisle to Wigton and Maryport, examining the

railway.

August 19th. Maryport to Carlisle, continuing the inspection.

August 20th. At Carlisle, examining the ground for a station;

and working up correspondence.

August 21st. Carlisle to Dumfries by mail; forward to Ayr by

chaise, proceeding up the valley of the Nith, through Thornhill,

Sanquhar, and Cumnock.

August 22d. Meeting with promoters of the Glasgow,

Kilmarnock, and Ayr Railway, and journey along the proposed line;

meeting with the magistrates of Kilmarnock at Beith, and journey

with them over Mr. Gale's proposed line to Kilmarnock.

August 23d. From Kilmarnock along Mr. Miller's proposed line

to Beith, Paisley, and Glasgow.

August 24th. Examination of site of proposed station at

Glasgow; meeting with the directors; then from Glasgow, by Falkirk

and Linlithgow, to Edinburg, meeting there with Mr. Grainger,

engineer, and several of the committee of the proposed Edinburg and

Dunbar Railway.

August 25th. Examining the site of the proposed station at

Edinburg; then to Dunbar, by Portobello, and Haddington, examining

the proposed line of railway.

August 26th. Dunbar to Tommy Grant's, to examine the summit

of the country toward Berwick, with a view to a through line to

Newcastle; then return to Edinburgh.

August 27th. At Edinburgh, meeting the provisional committee

of the proposed Edinburg and Dunbar Railway.

August 28th. Journey from Edinburg, through Melrose and

Jedburg, to Horsley, along the route of Mr. Richardson's proposed

railway across Carter Fell.

August 29th. From Horsley to Mr. Brandling's, then on to

Newcastle; engaged on the Brandling Junction Railway.

August 30th. Engaged with Mr. Brandling; after which, meeting

a deputation from Maryport.

August 31st. Meeting with Mr. Brandling and others as to the

direction of the Brandling Junction in connection with the Great

North of England line, and the course of the railway through

Newcastle; then on to York.

September 1st. At York; meeting with York and North Midland

directors; then journeying over Lord Howden's property, to arrange

for a deviation; examining the proposed site of the station at York.

September 2d. At York, giving instructions as to the survey;

then to Manchester by Leeds.

September 3d. At Manchester; journey to Stockport, with Mr.

Bidder and Mr. Bourne, examining the line to Stockport, and fixing

the crossing of the river there; attending to the surveys; then

journey back to Manchester, to meet the directors of the Manchester

and Leeds Railway.

September 4th. Sunday at Manchester.

September 5th. Journey along part of the Manchester and Leeds

Railway.

September 6th. At Manchester, examining and laying down the

section of the South Union line to Stockport; afterward engaged on

the Manchester and Leeds working plans, in endeavouring to give a

greater radius to the curves; seeing Mr. Seddon about the Liverpool,

Manchester, and Leeds Junction Railway.

September 7th. Journey along the Manchester and Leeds line,

then on to Derby.

September 8th. At Derby; seeing Mr. Carter and Mr. Beale

about the Tamworth deviation; then home to Alton Grange.

September 10th. At Alton Grange, preparing report to the

committee of the Edinburgh and Dunbar Railway."

Such is a specimen of the enormous amount of physical and

mental labour undergone by the engineer during the busy years above

referred to. He was no sooner home than he was called away

again by some other railway or business engagement. Thus, in

four days after his arrival at Alton Grange from the above journey

into Scotland, we find him going over the whole of the North Midland

line as far as Leeds; then by Halifax to Manchester, where he staid

for several days on the business of the South Union line; then to

Birmingham and London; back to Alton Grange, and next day to

Congleton and Leek; thence to Leeds and Goole, and home again by the

Sheffield and Rotherham and the Midland works. And early in

the following month (October) he was engaged in the north of

Ireland, examining the line, and reporting upon the plans of the

projected Ulster Railway. He was also called upon to inspect

and report upon colliery works, salt works, brass and copper works,

and such like, in addition to his own colliery and railway business.

He usually also staked out himself the lines laid out by him, which

involved a good deal of labour since undertaken by assistants.

And occasionally he would run up to London, attending in person to

the preparation and depositing of the plans and sections of the

projected undertakings for which he was engaged as engineer.

His correspondence increased so much that he found it

necessary to engage a private secretary, who accompanied him on his

journeys. He was himself exceedingly averse to writing

letters. The comparatively advanced age at which he learned

the art of writing, and the nature of his duties while engaged at

the Killingworth Colliery, precluded that facility in correspondence

which only constant practice can give. He gradually, however,

acquired great facility in dictation, and had also the power of

labouring continuously at this work, the gentleman who acted as his

secretary in the year 1835 having informed us that during his busy

season he one day dictated no fewer than thirty-seven letters,

several of them embodying the results of much close thinking and

calculation. On another occasion he dictated reports and

letters for twelve continuous hours, until his secretary was ready

to drop off his chair from sheer exhaustion, and at length pleaded

for a suspension of the labour. This great mass of

correspondence, though closely bearing on the subjects under

discussion, was not, however, of a kind to supply the biographer

with matter for quotation, or to give that insight into the life and

character of the writer which the letters of literary men so often

furnish. They were, for the most part, letters of mere

business, relating to works in progress, Parliamentary contests, new

surveys, estimates of cost, and railway policy—curt, and to the

point; in short, the letters of a man every moment of whose time was

precious.

Fortunately, George Stephenson possessed a facility of

sleeping, which enabled him to pass through this enormous amount of

fatigue and labour without injury to his health. He had been

trained in a hard school, and could bear with ease conditions which,

to men more softly nurtured, would have been the extreme of physical

discomfort. Many, many nights he snatched his sleep while

travelling in his chaise; and at break of day he would be at work,

surveying until dark, and this for weeks in succession. His

whole powers seemed to be under the control of his will, for he

could wake at any hour, and go to work at once. It was

difficult for secretaries and assistants to keep up with such a man.

It is pleasant to record that in the midst of these

engrossing occupations his heart remained as soft and loving as

ever. In spring-time he would not be debarred of his boyish

amusement of bird-nesting, but would go rambling along the hedges

spying for nests. In the autumn he went nutting, and when he

could snatch a few minutes he indulged in his old love of gardening.

His uniform kindness and good temper, and his communicative,

intelligent disposition, made him a great favourite with the

neighbouring farmers, to whom he would volunteer much valuable

advice on agricultural operations, drainage, ploughing, and

labour-saving processes. Sometimes he took a long rural ride

on his favourite "Bobby," now growing old, but as fond of his master

as ever. Toward the end of his life "Bobby" lived in clover,

his master's pet, doing no work; and he died at Tapton in 1845, more

than twenty years old.

During one of George's brief sojourns at the Grange he found

time to write to his son a touching account of a pair of robins that

had built their nest within one of the empty upper chambers of the

house. One day he observed a robin fluttering outside the

windows, and beating its wings against the panes, as if eager to

gain admission. He went upstairs, and there found, in a

retired part of one of the rooms, a robin's nest, with one of the

parent birds sitting over three or four young—all dead. The

excluded bird outside still beat against the panes; and on the

window being let down, it flew into the room, but was so exhausted

that it dropped upon the floor. Stephenson took up the bird,

carried it down stairs, and had it warmed and fed. The poor

robin revived, and for a time was one of his pets. But it

shortly died too, as if unable to recover from the privations it had

endured during its three days' fluttering and beating at the

windows. It appeared that the room had been unoccupied, and

the sash having been let down, the robins had taken the opportunity

of building their nest within it; but the servant having closed the

window again, the calamity befell the birds which so strongly

excited the engineer's sympathies. An incident such as this,

trifling though it may seem, gives a true key to the heart of a man.

The amount of his Parliamentary business having greatly

increased with the projection of new lines of railway, the

Stephensons found it necessary to set up an office in London in

1836. George's first office was at No. 9 Duke Street,

Westminster, from whence he removed in the following year to 30½

Great George Street. That office was the busy scene of railway

politics for several years. There consultations were held,

schemes were matured, deputations were received, and many projectors

called upon our engineer for the purpose of submitting to him their

plans of railways and railway working. His private secretary

at the time has informed us that at the end of the first

Parliamentary session in which he had been engaged as engineer for

more companies than one, it became necessary for him to give

instructions as to the preparation of the accounts to be rendered to

the several companies. In the simplicity of his heart, he

directed Mr. Binns to take his full time at the rate of ten guineas

a day, and charge the railway companies in the proportion in which

he had actually been employed in their respective business during

each day. When Robert heard of this instruction, he went

directly to his father and expostulated with him against this

unprofessional course; and, other influences being brought to bear

upon him, George at length reluctantly consented to charge as other

engineers did, all entire day's fee to each of the companies for

which he was concerned while their business was going forward; but

he cut down the number of days charged for, and reduced the daily

amount from ten to seven guineas.

Besides his journeys at home, George Stephenson was on more

than one occasion called abroad on railway business. Thus, at

the desire of King Leopold, he made several visits to Belgium to

assist the Belgian engineers in laying out the national lines of the

kingdom. That enlightened monarch at an early period discerned

the powerful instrumentality of railways in developing a country's

resources, and he determined at the earliest possible period to

adopt them as the great high roads of the nation. The country,

being rich in coals and minerals, had great manufacturing

capabilities. It had good ports, fine navigable rivers,

abundant canals, and a teeming, industrious population.

Leopold perceived that railways were eminently calculated to bring

the industry of the country into full play, and to render the riches

of the provinces available to the rest of the kingdom. He

therefore openly declared himself the promoter of public railways

throughout Belgium. A system of lines was projected at his

instance, connecting Brussels with the chief towns and cities of the

state, extending from Ostend eastward to the Prussian frontier, and

from Antwerp southward to the French frontier.

Mr. Stephenson and his son, as the leading railway engineers

of England, were consulted by the king, in 1835, as to the best mode

of carrying out his intentions. In the course of that year

they visited Belgium, and had several interesting conferences with

Leopold and his ministers on the subject of the proposed railways.

The king then appointed George Stephenson by royal ordinance a

Knight of the Order of Leopold. At the invitation of the

monarch, Mr. Stephenson made a second visit to Belgium in 1837, on

the occasion of the public opening of the line from Brussels to

Ghent. At Brussels there was a public procession, and another

at Ghent on the arrival of the train. Stephenson and his party

accompanied it to the Public Hall, there to dine with the chief

ministers of state, the municipal authorities, and about five

hundred of the principal inhabitants of the city; the English

ambassador being also present. After the king's health and a

few others had been drunk, that of Mr. Stephenson was proposed; on

which the whole assembly rose up, amid great excitement and loud

applause, and made their way to where he sat, in order to "jingle

glasses" with him, greatly to his own amazement. On the day

following, our engineer dined with the king and queen at their own

table at Laaken, by special invitation, afterward accompanying his

majesty and suite to a public ball, given by the municipality of

Brussels in honour of the opening of the line to Ghent, as well as

of their distinguished English guests. On entering the room,

the general and excited inquiry was, "Which is Stephenson?"

The English engineer had not before imagined that he was esteemed to

be so great a man.

The London and Birmingham Railway having been completed in

September, 1838, after being about five years in progress, the great

main system of railway communication between London, Liverpool, and

Manchester was then opened to the public. For some months

previously the line had been partially open, coaches performing the

journey between Denbigh Hall (near Wolverton) and Rugby—the works of

the Kilsby tunnel being still incomplete. It was already

amusing to hear the complaints of the travellers about the slowness

of the coaches as compared with the railway, though the coaches

travelled at a speed of eleven miles an hour. The comparison

of comfort was also greatly to the disparagement of the coaches.

Then the railway train could accommodate any quantity, whereas the

road conveyances were limited; and when a press of travellers

occurred—as on the occasion of the queen's coronation—the greatest

inconvenience was experienced, as much as £10 having been paid for a

seat on a donkey-chaise between Rugby and Denbigh. On the

opening of the railway throughout, of course all this inconvenience

was brought to an end.

Numerous other openings of railways constructed by George

Stephenson took place about the same time. The Birmingham and

Derby line was opened for traffic in August, 1839; the Sheffield and

Rotherham in November, 1839; and in the course of the following

year, the Midland, the York and North Midland, the Chester and

Crewe, the Chester and Birkenhead, the Manchester and Birmingham,

the Manchester and Leeds, and the Maryport and Carlisle railways,

were all publicly opened in whole or in part. Thus 321 miles

of railway (exclusive of the London and Birmingham), constructed

under Mr. Stephenson's superintendence, at a cost of upward of

eleven millions sterling, were, in the course of about two years,

added to the traffic accommodation of the country.

The ceremonies which accompanied the public opening of these

lines were often of an interesting character. The adjoining

population held general holiday; bands played, banners waved, and

assembled thousands cheered the passing trains amid the occasional

booming of cannon. The proceedings were usually wound up by a

public dinner; and in the course of his speech which followed, Mr.

Stephenson would revert to his favourite topic—the difficulties

which he had early encountered in the promotion of the railway

system, and in establishing the superiority of the locomotive.

On such occasions he always took great pleasure in alluding to the

services rendered to himself and the public by the young men brought

up under his eye—his pupils at first, and afterward his assistants.

No great master ever possessed a more devoted band of assistants and

fellow-workers than he did; and it was one of the most marked

evidences of his admirable tact and judgment that he selected, with

such undeviating correctness, the men best fitted to carry out his

plans. Indeed, the ability to accomplish great things, to carry

grand ideas into practical effect, depends in no small measure on

that intuitive knowledge of character which our engineer possessed

in so remarkable a degree.

At the dinner at York, which followed the partial opening of

the York and North Midland Railway, Mr. Stephenson said "he was sure

they would appreciate his feelings when he told them that, when he

first began railway business, his hair was black, although it was

now grey; and that he began his life's labour as but a poor

ploughboy. About thirty years since he had applied himself to

the study of how to generate high velocities by mechanical means.

He thought he had solved that problem; and they had for themselves

seen, that day, what perseverance had brought him to. He was,

on that occasion, only too happy to have an opportunity of

acknowledging that he had, in the latter portion of his career,

received much most valuable assistance particularly from young men

brought up in his manufactory. Whenever talent showed itself

in a young man, he had always given that talent encouragement where

he could, and he would continue to do so."

That this was no exaggerated statement is amply proved by

many facts which redound to Stephenson's credit. He was no

niggard of encouragement and praise when he saw honest industry

struggling for a footing. Many were the young men whom, in the

course of his career, he took by the hand and led steadily up to

honour and emolument, simply because he had noted their zeal,

diligence, and integrity. One youth excited his interest while

working as a common carpenter on the Liverpool and Manchester line;

and before many years had passed he was recognized as an engineer of

distinction. Another young man he found industriously working

away at his by-hours, and, admiring his diligence, he engaged him as

his private secretary, the gentleman shortly after rising to a

position of eminent influence and usefulness. Indeed, nothing

gave the engineer greater pleasure than in this way to help on any

deserving youth who came under his observation, and, in his own

expressive phrase, to "make a man of him."

The openings of the great main lines of railroad

communication shortly proved the fallaciousness of the numerous rash

prophecies which had been promulgated by the opponents of railways.

The proprietors of the canals were astounded by the fact that,

notwithstanding the immense traffic conveyed by rail, their own

traffic and receipts continued to increase; and that, in common with

other interests, they fully shared in the expansion of trade and

commerce which had been so effectually promoted by the extension of

the railway system. The cattle-owners were equally amazed to

find the price of horseflesh increasing with the extension of

railways, and that the number of coaches running to and from the new

railway stations gave employment to a greater number of horses than

under the old stage-coach system. Those who had prophesied the

decay of the metropolis, and the ruin of the suburban

cabbage-growers, in consequence of the approach of railways to

London, were disappointed; for, while the new roads let citizens out

of London, they also let country-people in. Their action, in

this respect, was centripetal as well as centrifugal. Tens of

thousands who had never seen the metropolis could now visit it

expeditiously and cheaply; and Londoners who had never visited the

country, or but rarely, were enabled, at little cost of time or

money, to see green fields and clear blue skies far from the smoke

and bustle of town. If the dear suburban-grown cabbages became

depreciated in value, there were truck-loads of fresh-grown country

cabbages to make amends for the loss: in this case, the "partial

evil" was a far more general good. The food of the metropolis

became rapidly improved, especially in the supply of wholesome meat

and vegetables. And then the price of coals—an article which,

in this country, is as indispensable as daily food to all

classes—was greatly reduced. What a blessing to the

metropolitan poor is described in this single fact!

The prophecies of ruin and disaster to landlords and farmers

were equally confounded by the openings of the railways. The

agricultural communications, so far from being "destroyed," as had

been predicted, were immensely improved. The farmers were

enabled to buy their coals, lime, and manure for less money, while

they obtained a readier access to the best markets for their stock

and farm-produce. Notwithstanding the predictions to the

contrary, their cows gave milk as before, the sheep fed and

fattened, and even skittish horses ceased to shy at the passing

trains. The smoke of the engines did not obscure the sky, nor

were farmyards burnt up by the fire thrown from the locomotives.

The farming classes were not reduced to beggary; on the contrary,

they soon felt that, so far from having any thing to dread, they had

very much good to expect from the extension of railways.

Landlords also found that they could get higher rent for

farms situated near a railway than at a distance from one.

Hence they became clamorous for "sidings." They felt it to be

a grievance to be placed at a distance from a station. After a

railway had been once opened, not a landlord would consent to have

the line taken from him. Owners who had fought the promoters

before parliament, and compelled them to pass their domains at a

distance, at a vastly increased expense in tunnels and deviations,

now petitioned for branches and nearer station-accommodation.

Those who held property near towns, and had extorted large sums as

compensation for the anticipated deterioration in the value of their

building land, found a new demand for it springing up at greatly

advanced prices. Land was now advertised for sale with the

attraction of being "near a railway station."

The prediction that, even if railways were made, the public

would not use them, was also completely falsified by the results.

The ordinary mode of fast travelling for the middle classes had

heretofore been by mail-coach and stage-coach. Those who could

not afford to pay the high prices charged by such conveyances went

by wagon, and the poorer classes trudged on foot. George

Stephenson was wont to say that he hoped to see the day when it

would be cheaper for a poor man to travel by railway than to walk,

and not many years passed before his expectation was fulfilled.

In no country in the world is time worth more money than in England;

and by saving time—the criterion of distance—the railway proved a

great benefactor to men of industry in all classes.

Many deplored the inevitable downfall of the old stage-coach

system. There was to be an end of that delightful variety of

incident usually attendant on a journey by road. The rapid

scamper across a fine country on the outside of the four-horse

"Express" or "Highflyer;" the seat on the box beside Jehu, or the

equally coveted place near the facetious guard behind; the journey

amid open green fields, through smiling villages and fine old towns,

where the stage stopped to change horses and the passengers to dine,

was all very delightful in its way, and many regretted that this

old-fashioned and pleasant style of travelling was about to pass

away. But it had its dark side also. Any one who

remembers the journey by stage from London to Manchester or York

will associate it with recollections and sensations of not unmixed

delight. To be perched for twenty-four hours, exposed to all

weathers, on the outside of a coach, trying in vain to find a soft

seat—sitting now with the face to the wind, rain, or sun, and now

with the back—without any shelter such as the commonest penny-a-mile

Parliamentary train now daily provides—was a miserable undertaking,

looked forward to with horror by many whose business required them

to travel frequently between the provinces and the metropolis.

Nor were the inside passengers more agreeably accommodated. To

be closely packed in a little, inconvenient, straight-backed

vehicle, where the cramped limbs could not be in the least extended,

nor the wearied frame indulge in any change of posture, was felt by

many to be a terrible thing. Then there were the

constantly-recurring demands, not always couched in the politest

terms, for an allowance to the driver every two or three stages, and

to the guard every six or eight; and if the gratuity did not equal

their expectations, growling and open abuse were not unusual.

These désagrémens, together with the exactions practiced on

travellers by innkeepers, seriously detracted from the romance of

stage-coach travelling, and there was a general disposition on the

part of the public to change the system for a better.

The avidity with which the public at once availed themselves

of the railways proved that this better system had been discovered.

Notwithstanding the reduction of the coach-fares on many of the

roads to one third of their previous rate, the public preferred

travelling by the railway. They saved in time, and they saved

in money, taking the whole expenses into account. In point of

comfort there could be no doubt as to the infinite superiority of

the locomotive train. But there remained the question of

safety, which had been a great bugbear with the early opponents of

railways, and was made the most of by the coach-proprietors to deter

the public from using them. It was predicted that trains of

passengers would be blown to pieces, and that none but fools would

entrust their persons to the conduct of an explosive machine such as

the locomotive. It appeared, however, that during the first

eight years not fewer than five millions of passengers had been

conveyed along the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and of this

vast number only two persons had lost their lives by accident.

During the same period, the loss of life by the upsetting of

stage-coaches had been immensely greater in proportion. The

public were not slow, therefore, to detect the fact that travelling

by railways was greatly safer than travelling by common roads, and

in all districts penetrated by railways the coaches were very

shortly taken off for want of support.

George Stephenson himself had a narrow escape in one of the

stage-coach accidents so common thirty years since, but which are

already almost forgotten. While the Birmingham line was under

construction, he had occasion to travel from Ashby-de-la-Zouch to

London by coach. He was an inside passenger with several

others, and the outsides were pretty numerous. When within ten

miles of Dunstable, he felt, from the rolling of the coach, that one

of the linchpins securing the wheels had given way, and that the

vehicle must upset. He endeavoured to fix himself in his seat,

holding on firmly by the arm-straps, so that he might save himself

on whichever side the coach fell. The coach soon toppled over,

and fell crash upon the road, amid the shrieks of his

fellow-passengers and the smashing of glass. He immediately

pulled himself up by the arm-strap above him, let down the

coach-window, and climbed out. The coachman and passengers lay

scattered about on the road, stunned, and some of them bleeding,

while the horses were plunging in their harness. Taking out

his pocket-knife, he at once cut the traces and set the horses free.

He then went to the help of the passengers, who were all more or

less hurt. The guard had his arm broken, and the driver was

seriously cut and contused. A scream from one of his

fellow-passenger "insides" here attracted his attention: it

proceeded from an elderly lady, whom he had before observed to be

decorated with one of the enormous bonnets in fashion at the time.

Opening the coach-door, he lifted the lady out, and her principal

lamentation was that her large bonnet had been crushed beyond

remedy! Stephenson then proceeded to the nearest village for

help, and saw the passengers provided with proper assistance before

he himself went forward on his journey.

It was some time before the more opulent classes, who could

afford to post to town in aristocratic style, became reconciled to

the railway train. It put an end to that gradation of rank in

travelling which was one of the few things left by which the

nobleman could be distinguished from the Manchester manufacturer and

bagman. But to younger sons of noble families the convenience

and cheapness of the railway did not fail to commend itself.

One of these, whose eldest brother had just succeeded to an earldom,

said to a railway manager, "I like railways—they just suit young

fellows like me, with 'nothing per annum paid quarterly.' You

know, we can't afford to post, and it used to be deuced annoying to

me, as I was jogging along on the box-seat of the stage-coach, to

see the little earl go by, drawn by his four posters, and just look

up at me and give me a nod. But now, with railways, it's

different. It's true, he may take a first-class ticket, while

I can only afford a second-class one, but we both go the same

pace."

For a time, however, many of the old families sent forward

their servants and luggage by railroad, and condemned themselves to

jog along the old highway in the accustomed family chariot, dragged

by country post-horses. But the superior comfort of the

railway shortly recommended itself to even the oldest families;

posting went out of date; post-horses were with difficulty to be had

along even the great high roads; and nobles and servants,

manufacturers and peasants, alike shared in the comfort, the

convenience, and the dispatch of railway travelling. The late

Dr. Arnold, of Rugby, regarded the opening of the London and

Birmingham line as another great step accomplished in the march of

civilization. "I rejoice to see it," he said, as he stood on

one of the bridges over the railway, and watched the train flashing

along under him, and away through the distant hedgerows—"I rejoice

to see it, and to think that feudality is gone forever: it is so

great a blessing to think that any one evil is really extinct."

It was long before the late Duke of Wellington would trust

himself behind a locomotive. The fatal accident to Mr.

Huskisson, which had happened before his eyes, contributed to

prejudice him strongly against railways, and it was not until the

year 1843 that he performed his first trip on the South-western

Railway, in attendance upon her majesty. Prince Albert had for

some time been accustomed to travel by railway alone, but in 1842

the queen began to make use of the same mode of conveyance between

Windsor and London. Even Colonel Sibthorpe was eventually

compelled to acknowledge its utility. For a time he continued

to post to and from the country as before. Then he compromised

the matter by taking a railway ticket for the long journey, and

posting only a stage or two nearest town; until, at length, he

undisguisedly committed himself, like other people, to the express

train, and performed the journey throughout upon what he had

formerly denounced as "the infernal railroad." |