|

LIVES OF GEORGE AND ROBERT STEPHENSON.

――――♦――――

LIFE OF GEORGE STEPHENSON, Etc.

CHAPTER I.

THE NEWCASTLE COAL-FIELD—GEORGE STEPHENSON'S EARLY YEARS.

IN

no quarter of England have greater changes been wrought by the

successive advances made in the practical science of engineering

than in the extensive colliery districts of the North, of which

Newcastle-upon-Tyne is the centre and the capital.

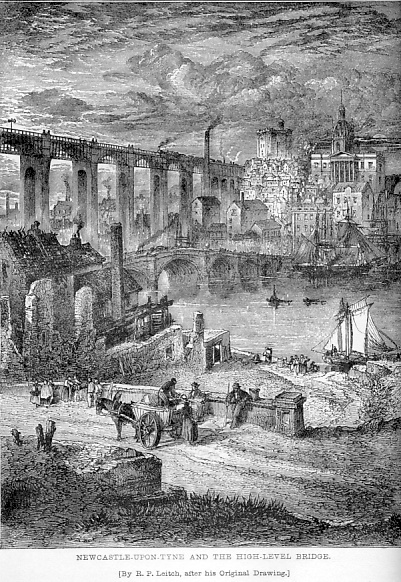

In ancient times the Romans planted a colony at Newcastle,

throwing a bridge across the Tyne near the site of the low-level

bridge shown in the prefixed engraving, and erecting a strong

fortification above it on the high ground now occupied by the

Central Railway Station. North and northwest lay a wild

country, abounding in moors, mountains, and morasses, but occupied

to a certain extent by fierce and barbarous tribes. To defend

the young colony against their ravages, a strong wall was built by

the Romans, extending from Wallsend on the north bank of the Tyne, a

few miles below Newcastle, across the country to Burgh-upon-Sands on

the Solway Frith. The remains of the wall are still to be

traced in the less populous hill-districts of Northumberland.

In the neighbourhood of Newcastle they have been gradually effaced

by the works of succeeding generations, though the "Wallsend" coal

consumed in our household fires still serves to remind us of the

great Roman work.

After the withdrawal of the Romans, Northumbria became

planted by immigrant Saxons from North Germany and Norsemen from

Scandinavia, whose eorls or earls made Newcastle their principal

seat. Then came the Normans, from whose New Castle,

built some eight hundred years since, the town derives its present

name. The keep of this venerable structure, black with age and

smoke, still stands entire at the northern end of the noble

high-level bridge—the utilitarian work of modern times thus

confronting the warlike relic of the older civilization. |

|

The nearness of Newcastle to the Scotch Border was a great hindrance

to its security and progress in the middle ages of English history.

Indeed, the district between it and Berwick continued to he ravaged

by moss-troopers long after the union of the crowns. The

gentry lived in their strong Peel castles; even the larger

farm-houses were fortified; and blood-hounds were trained for the

purpose of tracking the cattle-reavers to their retreats in the

hills. The judges of Assize rode from Carlisle to Newcastle

guarded by an escort armed to the teeth. A tribute called

"danger and protection money" was annually paid by the sheriff of

Newcastle for the purpose of providing daggers and other weapons for

the escort; and, though the need of such protection has long since

ceased, the tribute continues to be paid in broad gold pieces of the

time of Charles the First.

Until about the middle of last century the roads across

Northumberland were little better than horse-tracks, and not many

years since the primitive agricultural cart with solid wooden wheels

was almost as common in the western parts of the county as it is in

Spain now. The track of the old Roman road long continued to

be the most practicable route between Newcastle and Carlisle, the

traffic between the two towns having been carried on pack-horses

until within a comparatively recent period.

Since that time great changes have taken place on the Tyne.

When wood for firing became scarce and dear, and the forests of the

South of England were found inadequate to supply the increasing

demand for fuel, attention was turned to the rich stores of coal

lying underground in the neighbourhood of Newcastle and Durham.

It then became an article of increasing export, and "sea-coal" fires

gradually superseded those of wood. Hence an old writer

describes Newcastle as "the Eye of the North, and the Hearth that

warmeth the South parts of this kingdom with Fire." Fuel

became the staple product of the district, the quantity exported

increasing from year to year, until the coal raised from these

northern mines amounts to upward of sixteen millions of tons a year,

of which not less than nine millions are annually conveyed away by

sea.

Newcastle has in the mean time spread in all directions far

beyond its ancient boundaries. From a walled mediaeval town of

monks and merchants, it has been converted into a busy centre of

commerce and manufactures inhabited by nearly 100,000 people.

It is no longer a Border fortress—a "shield and defence against the

invasions and frequent insults of the Scots," as described in

ancient charters—but a busy centre of peaceful industry, and the

outlet for a vast amount of steam-power, which is exported in the

form of coal to all parts of the world. Newcastle is in many

respects a town of singular and curious interest, especially in its

older parts, which are full of crooked lanes and narrow streets,

wynds, and chares, formed by tall, antique houses, rising tier above

tier along the steep northern bank of the Tyne, as the similarly

precipitous streets of Gateshead crowd the opposite shore.

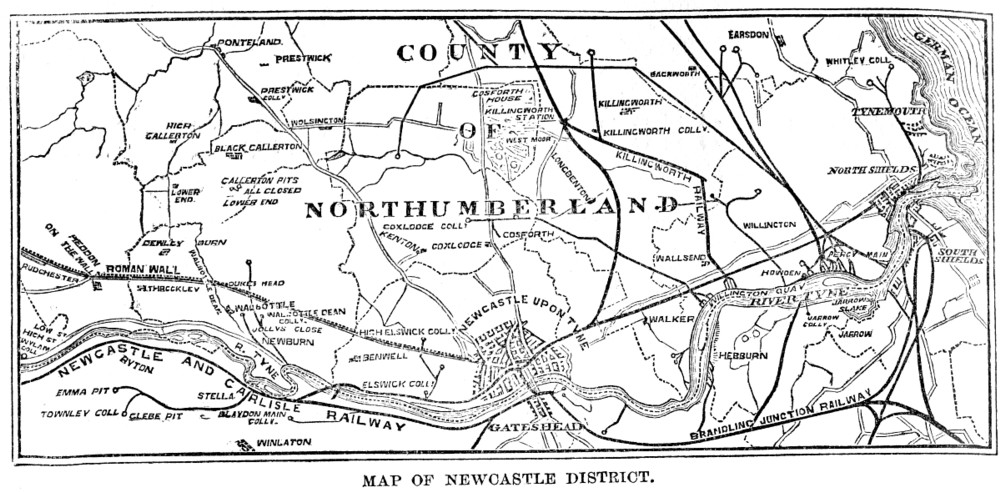

All over the coal region, which extends from the Coquet to the Tees,

about fifty miles from north to south, the surface of the soil

exhibits the signs of extensive underground workings. As you

pass through the country at night, the earth looks as if it were

bursting with fire at many points, the blaze of coke-ovens,

iron-furnaces, and coal-heaps reddening the sky to such a distance

that the horizon seems like a glowing belt of fire.

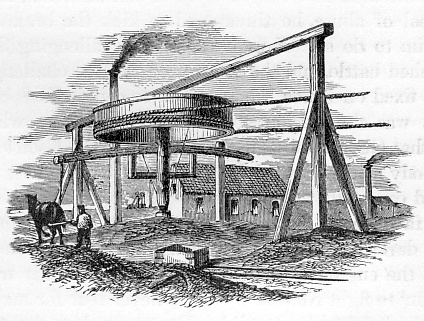

Among the upper-ground workmen employed at the coal-pits, the

principal are the firemen, engine-men, and brakesmen, who fire and

work the engines, and superintend the machinery by means of which

the collieries are worked. Previous to the introduction of the

steam-engine, the usual machine employed for the purpose was what is

called a "gin." The gin consists of a large drum placed

horizontally, round which ropes attached to buckets and corves are

wound, which are thus drawn up or sent down the shafts by a horse

travelling in a circular track or "gin race." This method was

employed for drawing up both coals and water, and it is still used

for the same purpose in small collieries; but where the quantity of

water to be raised is great, pumps worked by steam-power are called

into requisition.

Newcomen's atmospheric engine was first made use of to work

the pumps, and it continued to be so employed long after the more

powerful and economical condensing engine of Watt had been invented.

In the Newcomen or "fire-engine," as it was called, the power is

produced by the pressure of the atmosphere forcing down the piston

in the cylinder, on a vacuum being produced within it by

condensation of the contained steam by means of cold-water

injection. The piston-rod is attached to one end of a lever,

while the pump-rod works in connection with the other, the hydraulic

action employed to raise the water being exactly similar to that of

a common sucking-pump.

The working of a Newcomen engine was a clumsy and apparently

a very painful process, accompanied by an extraordinary amount of

wheezing, sighing, creaking, and bumping. When the pump

descended, there was heard a plunge, a heavy sigh, and a loud bump;

then, as it rose, and the sucker began to act, there was heard a

creak, a wheeze, another bump, and then a rush of water as it was

lifted and poured out. Where engines of a more powerful and

improved description were used, as is now the case, the quantity of

water raised is enormous—as much as a million and a half gallons in

the twenty-four hours.

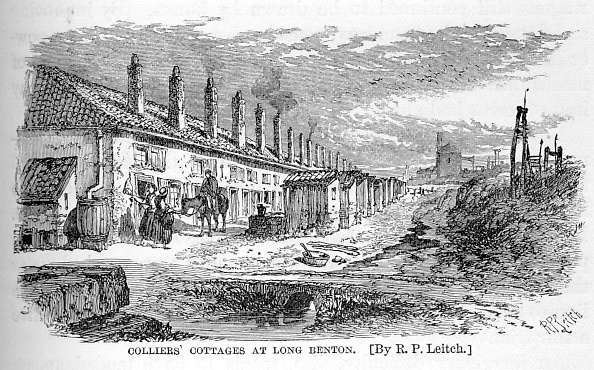

The pitmen, or "the lads belaw," who work out the coal below

ground, are a peculiar class, quite distinct from the workmen on the

surface. They are a people with peculiar habits, manners, and

character, as much so as fishermen and sailors, to whom, indeed,

they bear, in some respects, a considerable resemblance. Some

fifty years since, they were a much rougher and worse educated class

than they are now; hard workers, but very wild and uncouth; much

given to "steeks," or strikes; and distinguished, in their hours of

leisure and on pay-nights, for their love of cock-fighting,

dog-fighting, hard drinking, and cuddy races. The pay-night

was a fortnightly saturnalia, in which the pitman's character was

fully brought out, especially when the "yel" [Ed.—"ale"] was good.

Though earning much higher wages than the ordinary labouring

population of the upper soil, the latter did not mix nor intermarry

with them, so they were left to form their own communities, and

hence their marked peculiarities as a class. Indeed, a sort of

traditional disrepute seems long to have clung to the pitmen,

arising perhaps from the nature of their employment, and from the

circumstance that the colliers were among the last classes

enfranchised in England, as they were certainly the last in

Scotland, where they continued bondmen down to the end of last

century. The last thirty years, however, have worked a great

improvement in the moral condition of the Northumbrian pitmen; the

abolition of the twelve months' bond to the mine, and the

substitution of a month's notice previous to leaving, having given

them greater freedom and opportunity for obtaining employment; and

day-schools and Sunday-schools, together with the important

influences of railways, have brought them fully up to a level with

the other classes of the labouring population.

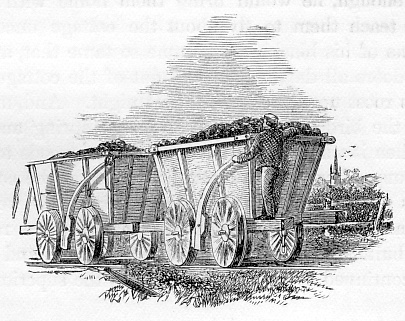

The coals, when raised from the pits, are emptied into the

wagons placed alongside, from whence they are sent along the rails

to the staiths erected by the river-side, the wagons sometimes

descending by their own gravity along inclined planes, the wagoner

standing behind to check the speed by means of a convoy or wooden

brake bearing upon the rims of the wheels. Arrived at the

staiths, the wagons are emptied at once into the ships waiting

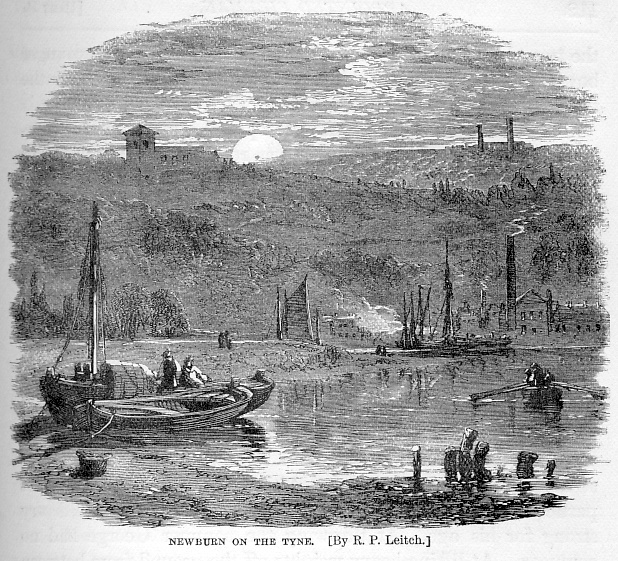

alongside for cargo. Any one who has sailed down the Tyne from

Newcastle Bridge can not but have been struck with the appearance of

the immense staiths, constructed of timber, which are erected at

short distances from each other on both sides of the river.

But a great deal of the coal shipped from the Tyne comes from

above-bridge, where sea-going craft can not reach, and is floated

down the river in "keels," in which the coals are sometimes piled up

according to convenience when large, or, when the coal is small or

tender, it is conveyed in tubs to prevent breakage. These

keels are of a very ancient model—perhaps the oldest extant in

England: they are even said to be of the same build as those in

which the Norsemen navigated the Tyne centuries ago. The keel

is a tubby, grimy-looking craft, rounded fore and aft, with a single

large square sail, which the keel-bullies, as the Tyne water-men are

called, manage with great dexterity; the vessel being guided by the

aid of the "swape," or great oar, which is used as a kind of rudder

at the stem of the vessel. These keelmen are an exceedingly

hardy class of workmen, not by any means as quarrelsome as their

designation of "bully" would imply—the word being merely derived

from the obsolete term "boolie," or beloved, an appellation still in

familiar use among brother workers in the coal districts. One

of the most curious sights on the Tyne is the fleet of hundreds of

these black-sailed, black-hulled keels, bringing down at each tide

their black cargoes for the ships at anchor in the deep water at

Shields and other parts of the river below Newcastle.

These preliminary observations will perhaps be sufficient to

explain the meaning of many of the occupations alluded to, and the

phrases employed, in the course of the following narrative, some of

which might otherwise have been comparatively unintelligible to the

reader.

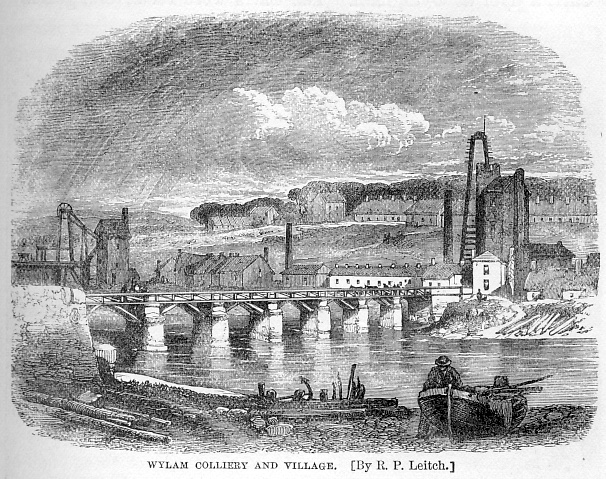

The colliery village of Wylam is situated on the north bank

of the Tyne, about eight miles west of Newcastle. The

Newcastle and Carlisle Railway runs along the opposite bank; and the

traveller by that line sees the usual signs of a colliery in the

unsightly pumping-engines surrounded by heaps of ashes, coal-dust,

and slag, while a neighbouring iron-furnace in full blast throws out

dense smoke and loud jets of steam by day and lurid flames at night.

These works form the nucleus of the village, which is almost

entirely occupied by coal-miners and iron-furnace-men. The

place is remarkable for its large population, but not for its

cleanness or neatness as a village; the houses, as in most colliery

villages, being the property of the owners or lessees, who employ

them in temporarily accommodating the work-people, against whose

earnings there is a weekly set-off for house and coals. About

the end of last century, the estate of which Wylam forms part

belonged to Mr. Blackett, a gentleman of considerable celebrity in

coal-mining, then more generally known as the proprietor of the

"Globe" newspaper.

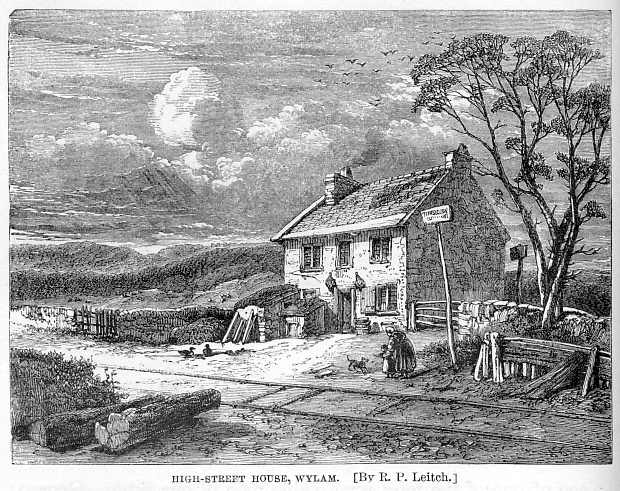

There is nothing to interest one in the village itself.

But a few hundred yards from its eastern extremity stands a humble

detached dwelling, which will he interesting to many as the

birthplace of one of the most remarkable men of our times—George

Stephenson, the Railway Engineer. It is a common, two-storied,

red-tiled, rubble house, portioned off into four labourers'

apartments. It is known by the name of High-street House, and

was originally so called because it stands by the side of what used

to be the old riding post-road or street between Newcastle and

Hexham, along which the post was carried on horseback within the

memory of persons living. |

|

The lower room in the west end of this house was the home of

the Stephenson family, and there George Stephenson was born, the

second of a family of six children, on the 9th of June, 1781.

The apartment is now, what it was then, an ordinary labourer's

dwelling; its walls are unplastered, its floor is of clay, and the

bare rafters are exposed overhead.

Robert Stephenson, or "Old Bob," as the neighbours familiarly

called him, and his wife Mabel, were a respectable couple, careful

and hard-working. Robert Stephenson's father was a Scotchman,

who came into England in the capacity of a gentleman's servant.[p.104]

Mabel, his wife, was the second daughter of Robert Carr, a dyer at

Ovingham. The Carrs were for several generations the owners of

a house in that village adjoining the church-yard; and the family

tomb-stone may still be seen standing against the east end of the

chancel of the parish church, underneath the centre lancet window,

as the tomb-stone of Thomas Bewick, the wood-engraver, occupies the

western gable. Mabel Stephenson was a woman of somewhat

delicate constitution, and troubled occasionally, as her neighbours

said, with "the vapours." But those who remembered her

concurred in describing her at "a real canny body;" and a woman of

whom this is said by general consent in the Newcastle district may

be pronounced a worthy person indeed, for it is about the highest

praise of a woman which Northumbrians can express.

|

|

For some time after their marriage, Robert resided with his

wife at Walbottle, a village situated between Wylam and Newcastle,

where he was employed as a labourer at the colliery; after which the

family removed to Wylam, where he found employment as a fireman of

the old pumping-engine at that colliery.

George Stephenson was the second of a family of six children.

[p.105]

It does not appear that the birth of any of the children was

registered in the parish books, the author having made an

unsuccessful search in the registers of Ovingham and Heddon-on-the-Wall

to ascertain the fact.

An old Wylam collier, who remembered George Stephenson's

father, thus described him: "Geordie's faytlier war like a peer o'

deals nailed thegither, an' a bit o' flesh i' th' inside; he war as

queer as Dick's hatband—went thrice aboot, an' wudn't tie. His

wife Mabel war a delicat' boddie, an' varry flighty. They war

an honest family, but sair hadden doon i' th' world." Indeed,

the earnings of old Robert did not amount to more than twelve

shillings a week; and, as there were six children to maintain, the

family, during their stay at Wylam, were necessarily in very

straitened circumstances. The father's wages being barely

sufficient even with the most rigid economy, for the sustenance of

the household, there was little to spare for clothing, and nothing

for education, so that none of the children were sent to school.

Old Robert was a general favourite in the village, especially

among the children, whom he was accustomed to draw about him while

tending the engine-fire, and feast their young imaginations with

tales of Sinbad the Sailor and Robinson Crusoe, besides others of

his own invention; so that "Bob's engine-fire" came to be the most

popular resort in the village. Another feature in his

character, by which he was long remembered, was his affection for

birds and animals; and he had many tame favourites of both sorts,

which were as fond of resorting to his engine-fire as the boys and

girls themselves. In the winter time he had usually a flock of

tame robins about him; and they would come hopping familiarly to his

feet to pick up the crumbs which he had saved for them out of his

humble dinner. At his cottage he was rarely without one or

more tame blackbirds, which flew about the house, or in and out at

the door. In summer time he would go bird-nesting with his

children; and one day he took his little boy George to see a

blackbird's nest for the first time. Holding him up in his

arms, he let the wondering boy peep down, through the branches held

aside for the purpose, into a nest full of young birds—a sight which

the boy never forgot, but used to speak of with delight to his

intimate friends when he himself had grown an old man.

The boy George led the ordinary life of working people's

children. He played about the doors; went bird-nesting when he

could; and ran errands to the village. He was also an eager

listener, with the other children, to his father's curious tales,

and he early imbibed from him his affection for birds and animals.

In course of time he was promoted to the office of carrying his

father's dinner to him while at work, and at home he helped to nurse

his younger brothers and sisters. One of his earliest duties

was to see that the other children were kept out of the way of the

chaldron wagons, which were then dragged by horses along the wooden

tram-road immediately in front of the cottage door.

This wagon-way was the first in the northern district on

which the experiment of a locomotive engine was tried. But, at

the time of which we speak, the locomotive had scarcely been dreamt

of in England as a practicable working power; horses only were used

to haul the coal; and one of the first sights with which the boy was

familiar was the coal-wagons dragged by them along the wooden

railway at Wylam.

Thus eight years passed; after which, the coal having been

worked out on the north side, the old engine, which had grown

"dismal to look at," as an old workman described it, was pulled

down; and then old Robert, having obtained employment as a fireman

at the Dewley Burn Colliery, removed with his family to that place.

Dewley Burn, at this day, consists of a few old-fashioned,

low-roofed cottages standing on either side of a babbling little

stream. They are connected by a rustic wooden bridge, which

spans the rift in front of the doors. In the central

one-roomed cottage of this group, on the right bank, Robert

Stephenson lived for a time with his family, the pit at which he

worked standing in the rear of the cottages.

Young though he was, George was now of an age to be able to

contribute something toward the family maintenance; for, in a poor

man's house, every child is a burden until his little hands can be

turned to profitable account. That the boy was shrewd and

active, and possessed of a ready mother-wit, will be evident enough

from the following incident. One day his sister Nell went into

Newcastle to buy a bonnet, and Geordie went with her "for company."

At a draper's shop in the Bigg Market Nell found a "chip" quite to

her mind, but on pricing it, alas! it was found to be fifteen pence

beyond her means. Girl-like, she had set her mind upon that

bonnet, and no other would please her. She accordingly left

the shop very much dejected. But Geordie said, "Never heed,

Nell; come wi' me, and I'll see if I canna win siller enough to buy

the bonnet; stand ye there till I come back." Away ran the

boy, and disappeared amid the throng of the market, leaving the girl

to wait his return. Long and long she waited, until it grew

dusk, and the market-people had nearly all left. She had begun

to despair, and fears crossed her mind that Geordie must have been

run over and killed, when at last up he came running, almost

breathless. "I've gotten the siller for the bonnet, Nell!"

cried he. "Eh, Geordie!" she said, "but hoo hae ye gotten it!"

"Hauddin the gentlemen's horses!" was the exultant reply. The

bonnet was forthwith bought, and the two returned to Dewley in

triumph.

George's first regular employment was of a very humble sort.

A widow, named Grace Ainslie, then occupied the neighbouring

farm-house of Dewley. She kept a number of cows, and had the

privilege of grazing them along the wagon-ways. She needed a

boy to herd the cows, to keep them out of the way of the wagons, and

prevent their straying or trespassing on the neighbours'

"liberties;" the boy's duty was also to bar the gates at night after

all the wagons had passed. George petitioned for this post,

and, to his great joy, he was appointed, at the wage of twopence a

day.

It was light employment, and he had plenty of spare time on

his hands, which he spent in bird-nesting, making whistles out of

reeds and scrannel straws, and erecting Liliputian mills in the

little water-streams that ran into the Dewley bog. But his

favourite amusement at this early age was erecting clay engines in

conjunction with his playmate, Bill Thirlwall. The place is

still pointed out where the future engineers made their first essays

in modelling. The boys found the clay for their engines in the

adjoining bog, and the hemlocks which grew about supplied them with

imaginary steam-pipes. They even proceeded to make a miniature

winding-machine in connection with their engine, and the apparatus

was erected upon a bench in front of the Thirlwalls' cottage.

Their corves were made out of hollowed corks; their ropes were

supplied by twine; and a few bits of wood gleaned from the refuse of

the carpenters' shop completed their materials. With this

apparatus the boys made a show of sending the corves down the pit

and drawing them up again, much to the marvel of the pitmen.

But some mischievous person about the place seized the opportunity

early one morning of smashing the fragile machinery, greatly to the

grief of the young engineers. We may mention, in passing, that

George's companion afterward became a workman of repute, and

creditably held the office of engineer at Shilbottle, near Alnwick,

for a period of nearly thirty years.

As Stephenson grew older and abler to work, he was set to

lead the horses when ploughing, though scarce big enough to stride

across the furrows; and he used afterward to say that he rode to his

work in the mornings at an hour when most other children of his age

were asleep in their beds. He was also employed to hoe

turnips, and do similar farm-work, for which he was paid the

advanced wage of fourpence a day. But his highest ambition was

to be taken on at the colliery where his father worked; and he

shortly joined his elder brother James there as a "corf-bitter," or

"picker," to clear the coal of stones, bats, and dross. His

wages were then advanced to sixpence a day, and afterward to

eightpence when he was sent to drive the gin-horse.

Shortly after, George went to Black Callerton Colliery to

drive the gin there; and, as that colliery lies about two miles

across the fields from Dewley Burn, the boy walked that distance

early in the morning to his work, returning home late in the

evening. One of the old residents at Black Callerton, who

remembered him at that time, described him to the author as "a grit

growing lad, with bare legs an' feet;" adding that he was "very

quick-witted, and full of fun and tricks: indeed, there was nothing

under the son but he tried to imitate." He was usually

foremost also in the sports and pastimes of youth.

Among his first strongly developed tastes was the love of

birds and animals, which he inherited from his father.

Blackbirds were his special favourites. The hedges between

Dewley and Black Callerton were capital bird-nesting places, and

there was not a nest there that he did not know of. When the

young birds were old enough, he would bring them home with him, feed

them, and teach them to fly about the cottage unconfined by cages.

One of his blackbirds became so tame that, after flying about the

doors all day, and in and out of the cottage, it would take up its

roost upon the bed-head at night. And, most singular of all,

the bird would disappear in the spring and summer months, when it

was supposed to go into the woods to pair and rear its young, after

which it would reappear at the cottage, and resume its social habits

during the winter. This went on for several years. George had

also a stock of tame rabbits, for which he built a little house

behind the cottage, and for many years he continued to pride himself

upon the superiority of his breed.

After he had driven the gin for some time at Dewley and Black

Callerton, he was taken on as assistant to his father in firing the

engine at Dewley. This was a step of promotion which he had

anxiously desired, his only fear being lest he should be found too

young for the work. Indeed, he afterward used to relate how he

was wont to hide himself when the owner of the colliery went round,

in case he should be thought too little a boy to earn the wages paid

him. Since he had modelled his clay engines in the bog, his

young ambition was to be an engine-man; and to be an assistant

fireman was the first step toward this position. Great,

therefore, was his joy when, at about fourteen years of age, he was

appointed assistant fireman, at the wage of a shilling a day.

But the coal at Dewley Burn being at length worked out, the

pit was ordered to be "laid in," and old Robert, and his family were

again under the necessity of shifting their home; for, to use the

common phrase, they must "follow the wark."

――――♦―――― |

|

CHAPTER II.

NEWBURN AND CALLERTON―GEORGE STEPHENSON

LEARNS TO BE AN ENGINE-MAN.

On quitting their humble home at Dewley Burn, the Stephenson

family removed to a place called Jolly's Close, a few miles to the

south, close behind the village of Newburn, where another coal-mine

belonging to the Duke of Northumberland, called "the Duke's Winnin"

had recently been opened out.

One of the old persons in the neighbourhood, who knew the

family well, describes the dwelling in which they lived as a poor

cottage of only one room, in which the father, mother, four sons,

and two daughters lived and slept. It was crowded with three

low-poled beds. The one apartment served for parlour, kitchen,

sleeping-room, and all.

The children of the Stephenson family were now growing apace,

and several of them were old enough to be able to earn money at

various kinds of colliery work, James and George, the two eldest

sons, worked as assistant firemen; and the younger boys worked as

wheelers or pickers on the bank-tops; while the two girls helped

their mother with the household work.

Other workings of the coal were opened out in the

neighbourhood, and to one of these George was removed as fireman on

his own account. This was called the "Mid Mill Winnin," where

he had for his mate a young man named Coe. They worked

together there for about two years, by twelve hour shifts, George

firing the engine at the wage of a shilling a day. He was now

fifteen years old. His ambition was as yet limited to

attaining the standing of a full workman, at a man's wages, and with

that view he endeavoured to attain such a knowledge of his engine as

would eventually lead to his employment as engine-man, with its

accompanying advantage of higher pay. He was a steady, sober,

hard-working young man, but nothing more in the estimation of his

fellow-workmen.

One of his favourite pastimes in by-hours was trying feats of

strength with his companions. Although in frame he was not

particularly robust, yet he was big and bony, and considered very

strong for his age. At throwing the hammer George had no

compeer. At lifting heavy weights off the ground from between

his feet, by means of a bar of iron passed through them—placing the

bar against his knees as a fulcrum, and then straightening his spine

and lifting them sheer up—he was also very successful. On one

occasion he lifted as much as sixty (sic.) stones' weight—a

striking indication of his strength of bone and muscle.

[Ed.—"sixteen" stones seems more likely.]

When the pit at Mid Mill was closed, George and his companion

Coe were sent to work another pumping-engine erected near Throckley

Bridge, where they continued for some months. It was while

working at this place that his wages were raised to 12s. a week—an

event to him of great importance. On coming out of the

foreman's office that Saturday evening on which he received the

advance, he announced the fact to his fellow-workmen, adding

triumphantly, "I am now a made man for life!"

The pit opened at Newburn, at which old Robert Stephenson

worked, proving a failure, it was closed, and a new pit was sunk at

Water-row, on a strip of land lying between the Wylam wagon-way and

the River Tyne, about half a mile west of Newburn Church. A

pumping-engine was erected there by Robert Hawthorn, the duke's

engineer, and old Stephenson went to work it as fireman, his son

George acting as the engine-man or plugman. At that time he

was about seventeen years old—a very youthful age at which to fill

so responsible a post. He had thus already got ahead of his

father in his station as a workman; for the plugman holds a higher

grade than the fireman, requiring more practical knowledge and

skill, and usually receiving higher wages.

George's duties as plugman were to watch the engine, to see

that it kept well in work, and that the pumps were efficient in

drawing the water. When the water-level in the pit was

lowered, and the suction became incomplete through the exposure of

the suction-holes, it was then his duty to proceed to the bottom of

the shaft and plug the tube so that the pump should draw: hence the

designation of "plugman." If a stoppage in the engine took place

through any defect which he was incapable of remedying, it was his

duty to call in the aid of the chief engineer to set it to rights.

But from the time that George Stephenson was appointed

fire-man, and more particularly afterward as engine-man, he applied

himself so assiduously and successfully to the study of the engine

and its gearing—taking the machine to pieces in his leisure hours

for the purpose of cleaning it and understanding its various

parts—that he soon acquired a thorough practical knowledge of its

construction and mode of working, and very rarely needed to call the

engineer of the colliery to his aid. His engine became a sort

of pet with him, and he was never wearied of watching and inspecting

it with admiration.

There is, indeed, a peculiar fascination about an engine to

the person whose duty it is to watch and work it. It is almost

sublime in its untiring industry and quiet power; capable of

performing the most gigantic work, yet so docile that a child's hand

may guide it. No wonder, therefore, that the workman who is

the daily companion of this life-like machine, and is constantly

watching it with anxious care, at length comes to regard it with a

degree of personal interest and regard. This daily

contemplation of the steam-engine, and the sight of its steady

action, is an education of itself to an ingenious and thoughtful

man. And it is a remarkable fact, that nearly all that has

been done for the improvement of this machine has been accomplished,

not by philosophers and scientific men, but by labourers, mechanics,

and engine-men. Indeed, it would appear as if this were one of

the departments of practical science in which the higher powers of

the human mind must bend to mechanical instinct.

Stephenson was now in his eighteenth year, but, like many of

his fellow-workmen, he had not yet learned to read. All that

he could do was to get some one to read for him by his engine-fire,

out of any book or stray newspaper which found its way into the

neighbourhood. Bonaparte was then overrunning Italy, and

astounding Europe by his brilliant succession of victories; and

there was no more eager auditor of his exploits, as read from the

newspaper accounts, than the young engine-man at the Water-row Pit.

There were also numerous stray bits of information and

intelligence contained in these papers which excited Stephenson's

interest. One of them related to the Egyptian method of

hatching birds' eggs by means of artificial heat. Curious

about every thing relating to birds, he determined to test it by

experiment. It was spring time, and he forthwith went

bird-nesting in the adjoining woods and hedges. He gathered a

collection of eggs of various sorts, set them in flour in a warm

place in the engine-house, covered the whole with wool, and waited

the issue. The heat was kept as steady as possible, and the

eggs were carefully turned every twelve hours; but, though they

chipped, and some of them exhibited well-grown chicks, they never

hatched. The experiment failed, but the incident shows that

the inquiring mind of the youth was fairly at work.

Modelling of engines in clay continued to be another of his

favourite occupations. He made models of engines which he had

seen, and of others which were described to him. These

attempts were an improvement upon his first trials at Dewley Burn

bog, when occupied there as a herd-boy. He was, however,

anxious to know something of the wonderful engines of Boulton and

Watt, and was told that they were to be found fully described in

books, which he must search for information as to their

construction, action, and uses. But, alas! Stephenson could

not read; he had not yet learned even his letters.

Thus he shortly found, when gazing wistfully in the direction

of knowledge, that to advance farther as a skilled workman he must

master this wonderful art of reading—the key to so many other arts.

Only thus could he gain an access to books, the depositories of the

wisdom and experience of the past. Although a grown man, and

doing the work of a man, he was not ashamed to confess his

ignorance, and go to school, big as he was, to learn his letters.

Perhaps, too, he foresaw that, in laying out a little of his spare

earnings for this purpose, he was investing money judiciously, and

that, in every hour he spent at school, he was really working for

better wages.

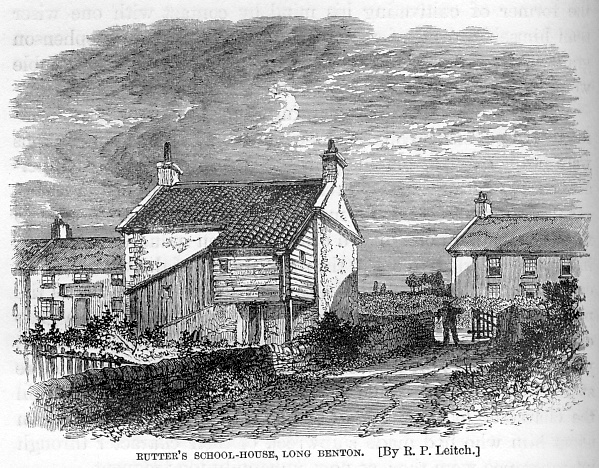

His first schoolmaster was Robin Cowens, a poor teacher in

the village of Walbottle. He kept a night-school, which was

attended by a few of the colliers' and labourers' sons in the

neighbourhood. George took lessons in spelling and reading

three nights in the week. Robin Cowen's teaching cost

threepence a week; and though it was not very good, yet George,

being hungry for knowledge and eager to acquire it, soon learned to

read. He also practiced "pot-hooks," and at the age of

nineteen he was proud to be able to write his own name.

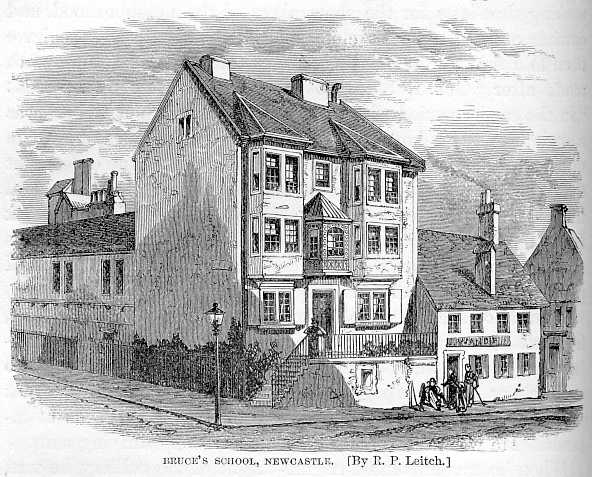

A Scotch dominie, named Andrew Robertson, set up a

night-school in the village of Newburn in the winter of 1799.

It was more convenient for George to attend this school, as it was

nearer his work, being only a few minutes' walk from Jolly's Close.

Besides, Andrew had the reputation of being a good arithmetician,

and this was a branch of knowledge that Stephenson was very desirous

of acquiring. He accordingly began taking lessons from him,

paying fourpence a week. Robert Gray, junior fire-man at the

Water-row Pit, began arithmetic at the same time; and Gray afterward

told the author that George learned "figuring" so much faster than

he did, that he could not make out how it was—"he took to figures so

wonderful." Although the two started together from the same

point, at the end of the winter George had mastered "reduction,"

while Robert Gray was still struggling with the difficulties of

simple division. But George's secret was his perseverance.

He worked out the sums in his by-hours, improving every minute of

his spare time by the engine-fire, there studying the arithmetical

problems set for him upon his slate by the master. In the evenings

he took to Robertson the sums which he had "worked," and new ones

were "set" for him to study out the following day. Thus his

progress was rapid, and, with a willing heart and mind, he soon

became well advanced in arithmetic. Indeed, Andrew Robertson

became very proud of his scholar; and shortly after, when the

Water-row Pit was closed, and George removed to Black Callerton to

work there, the poor schoolmaster, not having a very extensive

connection in Newburn, went with his pupils, and set up his

night-school at Black Callerton, where he continued his lessons.

George still found time to attend to his favourite animals

while working at the Water-row Pit. Like his father, he used

to tempt the robin-redbreasts to hop and fly about him at the

engine-fire by the bait of bread-crumbs saved from his dinner.

But his chief favourite was his dog—so sagacious that he almost

daily carried George's dinner to him at the pit. The tin

containing the meal was suspended from the dog's neck, and, thus

laden, he proceeded faithfully from Jolly's Close to Water-row Pit,

quite through the village of Newburn. He turned neither to

left nor right, nor heeded the barking of curs at his heels.

But his course was not unattended with perils. One day the

big, strange dog of a passing butcher, espying the engine-man's

messenger with the tin can about his neck, ran after and fell upon

him. There was a terrible tussle and worrying, which lasted

for a brief while, and, shortly after, the dog's master, anxious for

his dinner, saw his faithful servant approaching, bleeding but

triumphant. The tin can was still round his neck, but the

dinner had been spilled in the struggle. Though George went

without his dinner that day, he was prouder of his dog than ever

when the circumstances of the combat were related to him by the

villagers who had seen it.

It was while working at the Water-row Pit that Stephenson

learned the art of brakeing an engine. This being one of the

higher departments of colliery labour, and among the best paid,

George was very anxious to learn it. A small winding-engine

having been put up for the purpose of drawing the coals from the

pit. Bill Coe, his friend and fellow-workman, was appointed the

brakesman. He frequently allowed George to try his hand at the

machine, and instructed him how to proceed. Coe was, however,

opposed in this by several of the other workmen, one of whom, a

banksman named William Locke,[p.116]

went so far as to stop the working of the pit because Stephenson had

been called in to the brake. But one day, as Mr. Charles

Nixon, the manager of the pit, was observed approaching, Coe adopted

an expedient which put a stop to the opposition. He called

upon Stephenson to "come into the brake-house and take hold of the

machine." Locke, as usual, sat down, and the working of the

pit was stopped. When requested by the manager to give an

explanation, he said that "young Stephenson couldn't brake, and,

what was more, never would learn, he was so clumsy." Mr.

Nixon, however, ordered Locke to go on with the work, which he did;

and Stephenson, after some farther practice, acquired the art of

brakeing.

After working at the Water-row Pit and at other engines near

Newburn for about three years, George and Coe went to Black

Callerton early in 1810. Though only twenty years of age, his

employers thought so well of him that they appointed him to the

responsible office of brakesman at the Dolly Pit. For

convenience' sake, he took lodgings at a small farmer's in the

village, finding his own victuals, and paying so much a week for

lodging and attendance. In the locality this was called "picklin

in his awn poke neuk." It not unfrequently happens that the

young workman about the collieries, when selecting a lodging,

contrives to pitch his tent where the daughter of the house

ultimately becomes his wife. This is often the real attraction

that draws the youth from home, though a very different one may be

pretended.

George Stephenson's duties as brakesman may be briefly

described. The work was somewhat monotonous, and consisted in

superintending the working of the engine and machinery by means of

which the coals were drawn out of the pit. Brakesmen are

almost invariably selected from those who have had considerable

experience as engine-firemen, and borne a good character for

steadiness, punctuality, watchfulness, and "mother wit." In

George Stephenson's day the coals were drawn out of the pit in

corves, or large baskets made of hazel rods. The corves were

placed together in a cage, between which and the pit-ropes there was

usually from fifteen to twenty feet of chain. The approach of

the corves toward the pit mouth was signalled by a bell, brought

into action by a piece of mechanism worked from the shaft of the

engine. When the bell sounded, the brakesman checked the speed

by taking hold of the hand-gear connected with the steam-valves,

which were so arranged that by their means he could regulate the

speed of the engine, and stop or set it in motion when required.

Connected with the fly-wheel was a powerful wooden brake, acting by

pressure against its rim, something like the brake of a railway

carriage against its wheels. On catching sight of the chain

attached to the ascending corve-cage, the brakesman, by pressing his

foot upon a foot-step near him, was enabled, with great precision,

to stop the revolutions of the wheel, and arrest the ascent of the

corves at the pit mouth, when they were forthwith landed on the

"settle-board." On the full corves being replaced by empty

ones, it was then the duty of the brakesman to reverse the engine,

and send the corves down the pit to be filled again.

The monotony of George Stephenson's occupation as a brakesman

was somewhat varied by the change which he made, in his turn, from

the day to the night shift. His duty, on the latter occasions,

consisted chiefly in sending men and materials into the mine, and in

drawing other men and materials out. Most of the workmen enter

the pit during the night shift, and leave it in the latter part of

the day, while coal-drawing is proceeding. The requirements of

the work at night are such that the brakesman has a good deal of

spare time on his hands, which he is at liberty to employ in his own

way. From an early period, George was accustomed to employ

those vacant night hours in working the sums set for him by Andrew

Robertson upon his slate, practicing writing in his copy-book, and

mending the shoes of his fellow-workmen. His wages while

working at the Dolly Pit amounted to from £1 15s. to £2 in the

fortnight; but he gradually added to them as he became more expert

at shoe-mending, and afterward at shoe-making.

Probably he was stimulated to take in hand this extra work by

the attachment he had by this time formed for a young woman named

Fanny Henderson, who officiated as servant in the small farmer's

house in which he lodged. "We have been informed that the

personal attractions of Fanny, though these were considerable, were

the least of her charms. Mr. William Fairbairn, who afterward

saw her in her home at Willington Quay, describes her as a very

comely woman. But her temper was one of the sweetest; and

those who knew her were accustomed to speak of the charming modesty

of her demeanour, her kindness of disposition, and, withal, her

sound good sense.

Among his various mendings of old shoes at Callerton, George

was on one occasion favoured with the shoes of his sweetheart to

sole. One can imagine the pleasure with which he would linger

over such a piece of work, and the pride with which he would execute

it. A friend of his, still living, relates that, after he had

finished the shoes, he carried them about with him in his pocket on

the Sunday afternoon, and that from time to time he would pull them

out and hold them up, exclaiming "what a capital job he had made of

them!"

Not long after he began to work at Black Callerton as

brakesman he had a quarrel with a pitman named Ned Nelson, a

roistering bully, who was the terror of the village. Nelson

was a great fighter, and it was therefore considered dangerous to

quarrel with him. Stephenson was so unfortunate as not to be

able to please this pitman by the way in which he drew him out of

the pit, and Nelson swore at him grossly because of the alleged

clumsiness of his brakeing. George defended himself, and

appealed to the testimony of the other workmen. Nelson had not

been accustomed to George's style of self-assertion, and, after a

great deal of abuse, he threatened to kick the brakesman, who defied

him to do so. Nelson ended by challenging Stephenson to a

pitched battle, and the latter accepted the challenge, when a day

was fixed on which the fight was to come off.

Great was the excitement at Black Callerton when it was known

that George Stephenson had accepted Nelson's challenge. Every

body said he would be killed. The villagers, the young men,

and especially the boys of the place, with whom George was a great

favourite, all wished that he might beat Nelson, but they scarcely

dared to say so. They came about him while he was at work in

the engine-house to inquire if it was really true that be was "goin'

to fight Nelson." "Ay; never fear for me; I'll fight him."

And fight him he did. For some days previous to the appointed

day of battle, Nelson went entirely off work for the purpose of

keeping himself fresh and strong, whereas Stephenson went on doing

his daily work as usual, and appeared not in the least disconcerted

by the prospect of the affair. So, on the evening appointed,

after George had done his day's labour, he went into the Dolly Pit

Field, where his already exulting rival was ready to meet him.

George stripped, and "went in" like a practiced pugilist, though it

was his first and last fight. After a few rounds, George's

wiry muscles and practiced strength enabled him severely to punish

his adversary and to secure an easy victory.

This circumstance is related in illustration of Stephenson's

personal pluck and courage, and it was thoroughly characteristic the

man. He was no pugilist, and the reverse of quarrelsome.

But he would not be put down by the bully of the colliery, and he

fought him. There his pugilism ended; they afterward shook

hands, and continued good friends. In after life Stephenson's

mettle was often as hardly tried, though in a different way, and he

did not fail to exhibit the same courage in contending with the

bullies of the railway world as he showed in his encounter with Ned

Nelson, the fighting pitman of Callerton.

|

――――♦――――

|

CHAPTER III.

ENGINE-MAN AT WILLINGTON QUAY AND AT KILLINGWORTH.

GEORGE

STEPHENSON had now

acquired the character of an expert workman. He was diligent

and observant while at work, and sober and studious when the day's

work was done. His friend Coe described him to the author as

"a standing example of manly character." On pay-Saturday

afternoons, when the pit men held their fortnightly holiday,

occupying themselves chiefly in cock-fighting and dog-fighting in

the adjoining fields, followed by adjournments to the "yel-house,"

George was accustomed to take his engine to pieces, for the purpose

of obtaining "insight," and he cleaned all the parts and put the

machine in thorough working order before leaving her. His

amusements continued to be principally of the athletic kind, and he

found few that could beat him at lifting heavy weights, leaping, and

throwing the hammer.

In the evenings he improved himself in the arts of reading

and writing, and occasionally he took a turn at modelling. It

was at Callerton, his son Robert informed us, that he began to try

his hand at original invention, and for some time he applied his

attention to a machine of the nature of an engine-brake, which

reversed itself by its own action. But nothing came of the

contrivance, and it was eventually thrown aside as useless.

Yet not altogether so; for even the highest skill must undergo the

inevitable discipline of experiment, and submit to the wholesome

correction of occasional failure.

After working at Callerton for about two years, Stephenson

received an offer to take charge of the engine on Willington Ballast

Hill at an advanced wage. He determined to accept it, and at

the same time to marry Fanny Henderson, and begin housekeeping on

his own account. Though he was only twenty-one years old, he

had contrived, by thrift, steadiness, and industry, to save as much

money as enabled him, with the help of Fanny's small hoard, to take

a cottage dwelling at Willington Quay, and furnish it in a humble

but comfortable style for the reception of his bride.

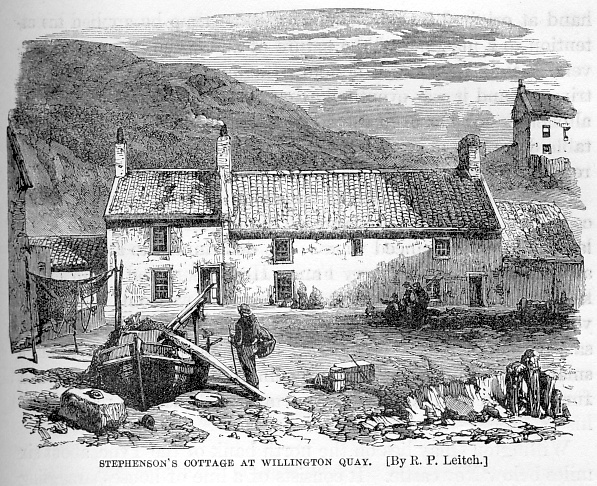

Willington Quay lies on the north bank of the Tyne, about six

miles below Newcastle. It consists of a line of houses

straggling along the river side, and high behind it towers up the

huge mound of ballast emptied out of the ships which resort to the

quay for their cargoes of coal for the London market. The

ballast is thrown out of the ships' holds into wagons laid

alongside. When filled, a train of these is dragged to the

summit of the Ballast Hill, where they are run out, and their

contents emptied on to the monstrous accumulation of earth, chalk,

and Thames mud already laid there, probably to form a puzzle for

future antiquaries and geologists when the origin of these immense

hills along the Tyne has been forgotten. At the foot of this

great mound of shot rubbish was a fixed engine, which drew the

trains of laden wagons up the incline by means of ropes working over

pulleys, and of this engine George Stephenson acted as brakes-man.

The cottage in which he took up his abode was a small

two-storied dwelling, standing a little back from the quay, with a

bit of garden ground in front; [p.122]

but he only occupied the upper room in the west end of the cottage.

Close behind rose the Ballast Hill.

When the cottage dwelling had been made snug and was ready

for his wife's reception, the marriage took place. It was

celebrated in Newburn Church on the 28th of November, 1802.

George Stephenson's signature, as it stands in the register, is that

of a person who seems to have just learned to write. With all the

writer's care, however, he had not been able to avoid a blotch. The

name of Frances Henderson has the appearance of being written by the

same hand.

After the ceremony, George and his newly-wedded partner

proceeded to the house of old Robert Stephenson and his wife Mabel

at Jolly Close. The old man was now becoming infirm, though he

still worked as an engine-fireman, and contrived with difficulty "to

keep his head above water." When the visit had been paid, the

bridal party prepared to set out for their new home at Willington

Quay. They went in a style which was quite common before

travelling by railway had been invented. Two farm-horses,

borrowed from a neighbouring farmer, were each provided with a

saddle and a pillion, and George having mounted one, his wife seated

herself behind him, holding on by her arms round his waist.

The brideman and bridesmaid in like manner mounted the other horse,

and in this wise the wedding party rode across the country, passing

through the old streets of Newcastle, and then by Wallsend to

Willington Quay—a long ride of about fifteen miles.

George Stephenson's daily life at Willington was that of a

steady workman. By the manner, however, in which he continued

to improve his spare hours in the evening, he was silently and

surely paving the way for being something more than a manual

labourer. He diligently set himself to study the principles of

mechanics, and to master the laws by which his engine worked.

For a workman, he was even at that time more than ordinarily

speculative, often taking up strange theories, and trying to sift

out the truth that was in them. While sitting by the side of

his young wife in his cottage dwelling in the winter evenings, he

was usually occupied in studying mechanical subjects or in modelling

experimental machines.

Among his various speculations while at Willington, he tried

to discover a means of Perpetual Motion. Although he failed,

as so many others had done before him, the very efforts he made

tended to whet his inventive faculties and to call forth his dormant

powers. He actually went so far as to construct the model of a

machine for the purpose. It consisted of a wooden wheel, the

periphery of which was furnished with glass tubes filled with

quicksilver; as the wheel rotated, the quicksilver poured itself

down into the lower tubes, and thus a sort of self-acting motion was

kept up in the apparatus, which, however, did not prove to be

perpetual. Where he had first obtained the idea of this

machine—whether from conversation, or reading, or his own thoughts,

is not known; but his son Robert was of opinion that he had heard of

an apparatus of this kind as described in the "History of

Inventions." As he had then no access to books, and, indeed,

could scarcely yet read, it is probable that he had been told of the

invention, and set about testing its value according to his own

methods.

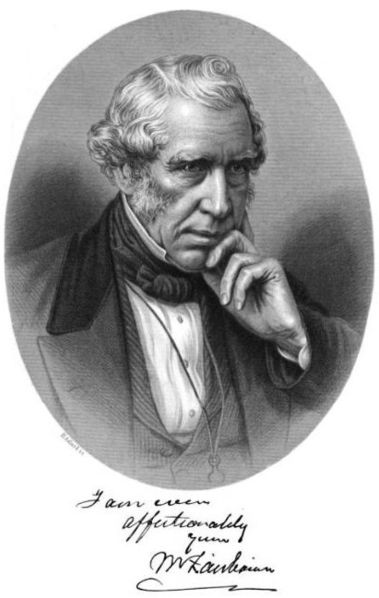

Sir William Fairbairn F.R.S., LL.D. (1789-1874)

structural engineer.

Much of his spare time continued to be occupied by labour

more immediately profitable, regarded in a pecuniary point of view.

In the evenings, after his day's labour at his engine, he would

occasionally employ himself for a few hours in casting ballast out

of the collier ships, by which means he was enabled to earn a few

shillings weekly. Mr. William Fairbairn, of Manchester, has

informed the author that, while Stephenson was employed at the

Willington Ballast Hill, he himself was working in the neighbourhood

as an engine apprentice at the Percy Main Colliery [Ed.—see the poet

Joseph Skipsey]. He was

very fond of George, who was a fine, hearty fellow, besides being a

capital workman. In the summer evenings young Fairbairn was

accustomed to go down to Willington to see his friend, and on such

occasions he would frequently take charge of George's engine for a

few hours, to enable him to take a two or three hours' turn at

heaving ballast out of the ships' holds. It is pleasant to

think of the future President of the British Association thus

helping the future Railway Engineer to earn a few extra shillings by

overwork in the evenings, at a time when both occupied the rank but

of humble working men in an obscure northern village.

Mr. Fairbairn was also a frequent visitor at George's cottage

on the Quay, where, though there was no luxury, there was comfort,

cleanness, and a pervading spirit of industry. Even at home

George was never for a moment idle. When there was no ballast

to heave, he took in shoes to mend; and from mending he proceeded to

making them, as well as shoe-lasts, in which he was admitted to be

very expert. William Coe, who continued to live at Willington

in 1851, informed the author that he bought a pair of shoes from

George Stephenson for 7s. 6d., and he remembered that

they were a capital fit, and wore very well.

But an accident occurred in Stephenson's household about this

time which had the effect of directing his industry into a new and

still more profitable channel. The cottage chimney took fire

one day in his absence, when the alarmed neighbours, rushing in,

threw quantities of water upon the flames; and some, in their zeal,

even mounted the ridge of the house, and poured buckets of water

down the chimney. The fire was soon put out, but the house was

thoroughly soaked. When George came home, he found the water

running out of the door, every thing in disorder, and his new

furniture covered with soot. The eight-day clock, which hung

against the wall—one of the most highly-prized articles in the

house—was seriously damaged by the steam with which the room had

been filled. Its wheels were so clogged by the dust and soot

that it was brought to a complete stand-still.

George was advised to send the article to the clock-maker,

but that would cost money; and he declared that he would repair it

himself—at least he would try. The clock was accordingly taken

to pieces and cleaned; the tools which he had been accumulating for

the purpose of constructing his Perpetual Motion machine readily

enabled him to do this, and he succeeded so well that, shortly

after, the neighbours sent him their clocks to clean, and he soon

became one of the most expert clock-cleaners in the neighbourhood.

It was while living at Willington Quay that George

Stephenson's only son was born on the 16th of October, 1803. [126-1]

The child was from the first, as may well be imagined, a great and

favourite with his father, and added much to the happiness of his

evening hours. George Stephenson's strong "philoprogenitivenees,''

as phrenologists call it, had in his boyhood expended itself on

birds, and dogs, and rabbits, and even on the poor old gin-horses

which he had driven at the Callerton Pit, and now he found in his

child a more genial object for the exercise of his affection.

The christening of the boy took place in the school-house at

Wallsend, the old parish church being at the time in so dilapidated

a condition from the "creeping" or subsidence of the ground,

consequent upon the excavation of the coal, that it was considered

dangerous to enter it. [126-2]

On this occasion, Robert Gray and Anne Henderson, who had officiated

as brideman and bridesmaid at the wedding, came over again to

Willington, and stood godfather and godmother to little Robert, as

the child was named, after his grandfather.

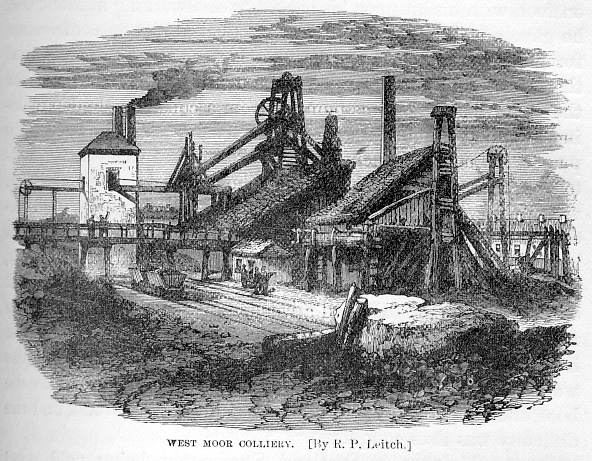

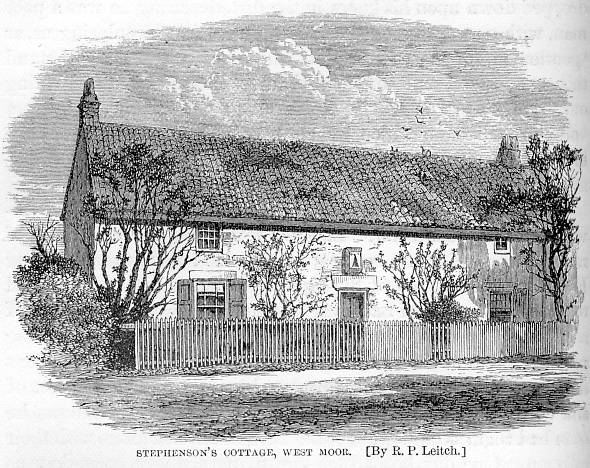

After working for about three years as a brakesman at the

Willington machine, George Stephenson was induced to leave his

situation there for a similar one at the West Moor Colliery,

Killingworth. It was not without considerable persuasion that

he was induced to leave the Quay, as he knew that he should thereby

give up the chance of earning extra money by casting ballast from

the keels. At last, however, he consented, in the hope of

making up the loss in some other way.

|

|

The village of Killingworth lies about seven miles north of

Newcastle, and is one of the best-known collieries in that

neighbourhood. The workings of the coal are of vast extent,

and give employment to a large number of work-people. To this

place Stephenson first came as a brakesman about the end of 1804.

He had not been long in his new home ere his wife died of

consumption, leaving him with his only child Robert. George

deeply felt the loss, for his wife and he had been very happy

together. Their lot had been sweetened by daily successful

toil. George had been hard-working, and his wife had made his

hearth so bright and his home so snug, that no attraction could draw

him from her side in the evening hours. But this domestic

happiness was all to pass away, and the bereaved husband felt for a

time as one that had thenceforth to tread the journey of life alone.

Shortly after this event, while his grief was still fresh, he

received an invitation from some gentlemen concerned in large

spinning-works near Montrose, in Scotland, to proceed thither and

superintend the working of one

of Boulton and Watt's engines. He accepted the offer, and made

arrangements to leave Killingworth for a time.

Having left his boy in charge of a respectable woman who

acted as his housekeeper, he set out on the journey to Scotland on

foot, with his kit upon his back. While working at Montrose,

he gave a striking proof of that practical ability in contrivance

for which he was afterward so distinguished. It appears that

the water required for the purposes of his engine, as well as for

the use of the works, was pumped from a considerable depth, being

supplied from the adjacent extensive sand strata. The pumps

frequently got choked by the sand drawn in at the bottom of the well

through the snore-holes, or apertures through which the water to be

raised is admitted. The barrels soon became worn, and the

bucket and clack leathers destroyed, so that it became necessary to

devise a remedy; and with this object, the engine-man proceeded to

adopt the following simple but original expedient. He had a

wooden box or boot made, twelve feet high, which he placed in the

sump or well, and into this he inserted the lower end of the pump.

The result was, that the water flowed clear from the outer part of

the well over into the boot, and was drawn up without any admixture

of sand, and the difficulty was thus conquered.[p.128]

During his stay in Scotland, Stephenson, being paid good

wages, contrived to save a sum of £28, which he took back with him

to Killingworth, after an absence of about a year. Longing to

get back to his kindred, and his heart yearning for the boy whom he

had left behind, our engine-man bade adieu to his Montrose

employers, and trudged back to Killingworth on foot as he had gone.

He related to his friend Coe, on his return, that when on the

borders of Northumberland, late one evening, footsore and wearied

with his long day's journey, he knocked at a small farmer's cottage

door, and requested shelter for the night. It was refused; and

then he entreated that, being sore tired and unable to proceed any

farther, they would permit him to lie down in the outhouse, for that

a little clean straw would serve him. The farmer's wife

appeared at the door, looked at the traveller, then retiring with

her husband, the two confabulated a little apart, and finally they

invited Stephenson into the cottage. Always full of

conversation and anecdote, he soon made himself at home in the

farmer's family, and spent with them some pleasant hours. He

was hospitably entertained for the night, and when he left the

cottage in the morning, he pressed them to make some charge for his

lodging, but they refused to accept any recompense. They only

asked him to remember them kindly, and if he ever came that way, to

be sure and call again. Many years after, when Stephenson had

become a thriving man, he did not forget the humble pair who had

thus succoured and entertained him on his way; he sought their

cottage again when age had silvered their hair; and when he left the

agèd couple on that occasion, they may have been reminded of the old

saying that we may sometimes "entertain angels unawares."

Reaching home, Stephenson found that his father had met with

a serious accident at the Blucher Pit, which had reduced him to

great distress and poverty. While engaged in the inside of an

engine, making some repairs, a fellow-workman inadvertently let in

the steam upon him. The blast struck him full in the face; he

was terribly scorched, and his eyesight was irretrievably lost.

The helpless and infirm man had struggled for a time with poverty;

his sons who were at home, poor as himself, were little able to help

him, while George was at a distance in Scotland. On his

return, however, with his savings in his pocket, his first step was

to pay off his father's debts, amounting to about £15; and, shortly

after, he removed the agèd pair from Jolly's Close to a comfortable

cottage adjoining the tram-road near the West Moor at Killingworth,

where the old man lived for many years, supported by his son.

Stephenson was again taken on as a brakesman at the West Moor

Pit. He does not seem to have been very hopeful as to his

prospects in life at the time. Indeed, the condition of the

working classes was then very discouraging. England was

engaged in a great war, which pressed upon the industry, and

severely tried the resources of the country. Heavy taxes were

imposed upon all the articles of consumption that would bear them.

There was a constant demand for men to fill the army, navy, and

militia. Never before had England witnessed such drumming and

fifing for recruits. In 1805, the gross forces of the United

Kingdom amounted to nearly 700,000 men, and early in 1808 Lord

Castlereagh carried a measure for the establishment of a local

militia of 200,000 men. These measures were accompanied by

general distress among the labouring classes. There were riots

in Manchester, Newcastle, and elsewhere, through scarcity of work

and lowness of wages. The working people were also liable to

be pressed for the navy, or drawn for the militia; and though people

could not fail to be discontented under such circumstances, they

scarcely dared even to mutter their discontent to their neighbours.

George Stephenson was one of those drawn for the militia.

He must therefore either quit his work and go a-soldiering, or find

a substitute. He adopted the latter course, and borrowed £6,

which, with the remainder of his savings, enabled him to provide a

militia-man to serve in his stead. Thus the whole of his

hard-won earnings were swept away at a stroke. He was almost

in despair, and contemplated the idea of leaving the country, and

emigrating to the United States. Although a voyage thither was

then a much more formidable thing for a working man to accomplish

than a voyage to Australia is now, he seriously entertained the

project, and had all but made up his mind to go. His sister

Ann, with her husband, emigrated about that time, but George could

not raise the requisite money, and they departed without him.

After all, it went sore against his heart to leave his home and his

kindred, the scenes of his youth and the friends of his boyhood, and

he struggled long with the idea, brooding over it in sorrow.

Speaking afterward to a friend of his thoughts at the time, he said:

"You know the road from my house at the West Moor to Killingworth.

I remember once when I went along that road I wept bitterly, for I

knew not where my lot in life would be cast." But his poverty

prevented him from prosecuting the idea of emigration, and rooted

him to the place where he afterward worked out his career so

manfully and victoriously.

In 1808, Stephenson, with two other brakesmen, took a small

contract under the colliery lessees, brakeing the engines at the

West Moor Pit. The brakesmen found the oil and tallow; they

divided the work among them, and were paid so much per score for

their labour. There being two engines working night and day,

two of the three men were always on duty, the average earnings of

each amounting to from 18s. to 20s. a week. It

was the interest of the brakesmen to economize the working as much

as possible, and George no sooner entered upon the contract than he

proceeded to devise ways and means of making the contract "pay."

He observed that the ropes with which the coal was drawn out of the

pit by the winding-engine were badly arranged; they "glued" and wore

each other to tatters by the perpetual friction. There was

thus great wear and tear, and a serious increase in the expenses of

the pit. George found that the ropes which, at other pits in

the neighbourhood, lasted about three months, at the West Moor Pit

became worn out in about a month. He accordingly set himself

to ascertain the cause of the defect; and, finding that it was

occasioned by excessive friction, he proceeded, with the sanction of

the head engine-wright and of the colliery owners, to shift the

pulley-wheels so that they worked immediately over the centre of the

pit. By this expedient, accompanied by an entire rearrangement

of the gearing of the machine, he shortly succeeded in greatly

lessening the wear and tear of the ropes, to the advantage of the

owners as well as of the workmen, who were thus enabled to labour

more continuously and profitably.

About the same time he attempted an improvement in the

winding-engine which he worked, by placing a valve between the

air-pump and condenser. This expedient, although it led to no

practical result, showed that his mind was actively engaged in

studying new mechanical adaptations. It continued to be his

regular habit, on Saturdays, to take his engine to pieces, for the

purpose at the same time of familiarizing himself with its action,

and of placing it in a state of thorough working order; and by

mastering the details of the engine, he was enabled, as opportunity

occurred, to turn to practical account the knowledge thus diligently

and patiently acquired.

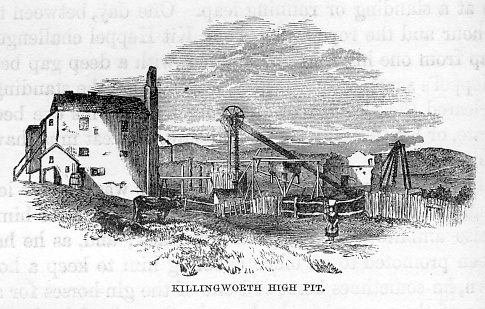

Such an opportunity was not long in presenting itself.

In the year 1810, a pit was sunk by the "Grand Allies" (the lessees

of the mines) at the village of Killingworth, now known as the

Killingworth High Pit. An atmospheric or Newcomen engine,

originally made by Smeaton, was fixed there for the purpose of

pumping out the water from the shaft; but, somehow or other, the

engine failed to clear the pit. As one of the workmen has

since described the circumstance—"She couldn't keep her jack-head in

water: all the engine-men in the neighbourhood were tried, as well

as Crowther of the Ouseburn, but they were clean bet." The

engine had been fruitlessly pumping for nearly twelve months, and

came to be regarded as a total failure. Stephenson had gone to

look at it when in course of erection, and then observed to the

over-man that he thought it was defective; he also gave it as his

opinion that if there were much water in the mine, the engine could

never keep it under. Of course, as he was only a brakesman,

his opinion was considered to be worth very little on such a point.

He continued, however, to make frequent visits to the engine to see

"how she was getting on." From the bank-head where he worked

his brake he could see the chimney smoking at the High Pit; and as

the workmen were passing to and from their work, he would call out

and inquire "if they had gotten to the bottom yet." And the

reply was always to the same effect—the pumping made no progress,

and the workmen were still "drowned out."

One Saturday afternoon he went over to the High Pit to

examine the engine more carefully than he had yet done. He had

been turning the subject over in his mind, and, after a long

examination, he seemed to have satisfied himself as to the cause of

the failure. Kit Heppel, one of the sinkers, asked him, "Weel,

George, what do you mak' o' her? Do you think you could do any

thing to improve her?" "Man," said George, in reply, "I could

alter her and make her draw: in a week's time from this I could send

you to the bottom."

Heppel at once reported this conversation to Ralph Dodds, the

head viewer, who, being now quite in despair, and hopeless of

succeeding with the engine, determined to give George's skill a

trial. George had already acquired the character of a very

clever and ingenious workman, and, at the worst, he could only fail,

as the rest had done. In the evening Dodds went in search of

Stephenson, and met him on the road, dressed in his Sunday's suit,

on his way to "the preaching" in the Methodist Chapel, which he at

that time attended. "Well, George," said Dodds, "they tell me

that you think you can put the engine at the High Pit to rights."

"Yes, sir," said George, "I think I could." "If that's the

case, I'll give you a fair trial, and you must set to work

immediately. We are clean drowned out, and can not get a step

farther. The engineers hereabouts are all bet; and if you

really succeed in accomplishing what they can not do, you may depend

upon it I will make you a man for life."

Stephenson began his operations early next morning. The

only condition that he made, before setting to work, was that he

should select his own workmen. There was, as he knew, a good

deal of jealousy among the "irregular" men that a colliery brakesman

should pretend to know more about their engine than they themselves

did, and attempt to remedy defects which the most skilled men of

their craft, including the engineer of the colliery, had failed to

do. But George made the condition a sine qua non.

"The workmen," said he, "must either be all Whigs or all Tories."

There was no help for it, so Dodds ordered the old hands to stand

aside. The men grumbled, but gave way; and then George and his

party went in.

The engine was taken entirely to pieces. The cistern

containing the injection water was raised ten feet; the injection

cock, being too small, was enlarged to nearly double its former

size, and it was so arranged that it should be shut off quickly at

the beginning of the stroke. These and other alterations were

necessarily performed in a rough way, but, as the result proved, on