|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER XVI.

GEORGE STEPHENSON'S COAL-MINES—APPEARS AT MECHANICS' INSTITUTES—HIS

OPINION ON RAILWAY SPEEDS—ATMOSPHERIC SYSTEM—RAILWAY MANIA—VISITS TO

BELGIUM AND SPAIN. |

|

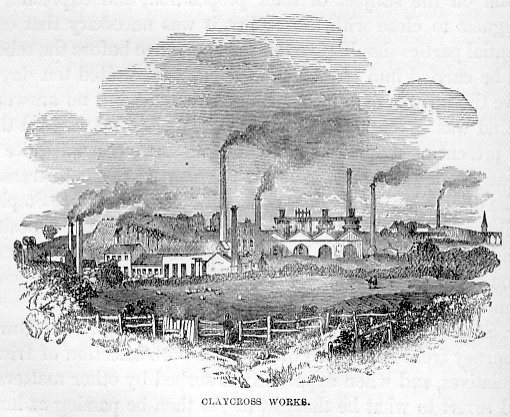

WHILE

George Stephenson was engaged in carrying on the works of the

Midland Railway in the neighbourhood of Chesterfield, several seams

of coal were cut through in the Claycross Tunnel, when it occurred

to him that if mines were opened out there, the railway would

provide the means of a ready sale for the article in the midland

counties, and even as far south as the metropolis itself.

At a time when everybody else was sceptical as to the

possibility of coals being carried from the midland counties to

London, and sold there at a price to compete with those which were

sea-borne, he declared his firm conviction that the time was fast

approaching when the London market would be regularly supplied with

North-country coals led by railway. One of the great

advantages of railways, in his opinion, was that they would bring

iron and coal, the staple products of the country, to the doors of

all England. "The strength of Britain," he would say,

"lies in her iron and coal beds, and the locomotive

is destined, above all other agencies, to bring it forth. The

lord chancellor now sits upon a bag of wool; but wool has long since

ceased to be emblematical of the staple commodity of England.

He ought rather to sit upon a bag of coals, though it might not

prove quite so comfortable a seat. Then think of the lord

chancellor being addressed as the noble and learned lord on the

coal-sack! I am afraid it wouldn't answer, after all."

To one gentleman he said:

"We want from the coal-mining, the iron-producing and

manufacturing districts, a great railway for the carriage of these

valuable products. We want, if I may so say, a stream of steam

running directly through the country from the North to London.

Speed is not so much an object as utility and cheapness. It

will not do to mix up the heavy merchandise and coal-trains with the

passenger-trains. Coal and most kinds of goods can wait, but

passengers will not. A less perfect road and less expensive

works will do well enough for coal-trains, if run at a low speed;

and if the line be flat, it is not of much consequence whether it be

direct or not. Whenever you put passenger-trains on a line,

all the other trains must be run at high speeds to keep out of their

way. But coal-trains run at high speeds pull the road to

pieces, besides causing large expenditure in locomotive power; and I

doubt very much whether they will pay, after all; but a succession

of long coal-trains, if run at from ten to fourteen miles an hour,

would pay very well. Thus the Stockton and Darlington Company

made a larger profit when running coal at low speeds at a halfpenny

a ton per mile, than they have been able to do since they put on

their fast passenger-trains, when everything must needs be run

faster, and a much larger proportion of the gross receipts is

consequently absorbed by working expenses."

In advocating these views, George Stephenson was considerably

ahead of his time; and although he did not live to see his

anticipations fully realized as to the supply of the London

coal-market, he was nevertheless the first to point it out, and to

some extent to prove, the practicability of establishing a

profitable coal-trade by railway between the northern counties and

the metropolis. So long, however, as the traffic was conducted on

main passenger-lines at comparatively high speeds, it was found that

the expenditure on tear and wear of road and locomotive power—not to

mention the increased risk of carrying on the first-class passenger

traffic with which it was mixed up—necessarily left a very small

margin of profit, and hence our engineer was in the habit of urging

the propriety of constructing a railway which should be exclusively

devoted to goods and mineral traffic run at low speeds as the only

condition on which a large railway traffic of that sort could be

profitably conducted.

Having induced some of his Liverpool friends to join him in a

coal-mining adventure at Chesterfield, a lease was taken of the

Claycross estate, then for sale, and operations were shortly after

begun. At a subsequent period Stephenson extended his

coal-mining operations in the same neighbourhood, and in 1841 he

himself entered into a contract with owners of land in the townships

of Tapton, Brimington, and Newbold for the working of the coal

thereunder, and pits were opened on the Tapton estate on an

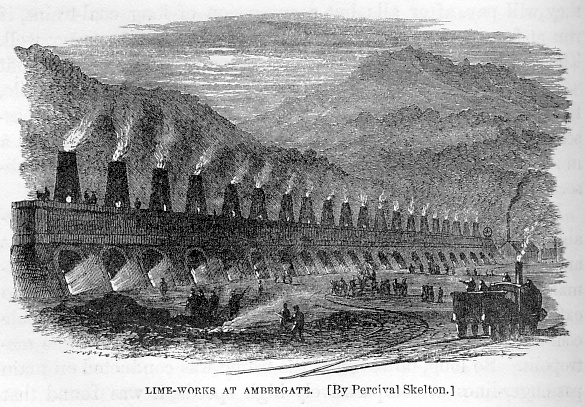

extensive scale. About the same time he erected great

lime-works, close to the Ambergate station of the Midland Railway,

from which, when in full operation, he was able to turn out upward

of two hundred tons a day. The limestone was brought on a

tramway from the village of Crich, about two or three miles distant

from the kilns, the coal being supplied from his adjoining Claycross

Colliery. The works were on a scale such as had not before

been attempted by any private individual engaged in a similar trade,

and we believe they proved very successful. |

|

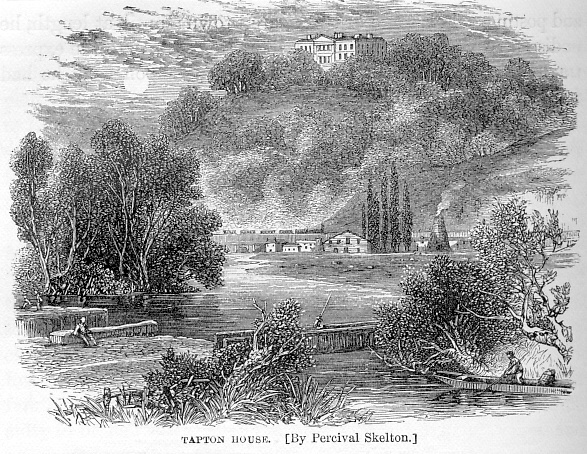

Tapton House was included in the lease of one of the

collieries, and as it was conveniently situated—being, as it were, a

central point on the Midland Railway, from which the engineer could

readily proceed north or south on his journeys of inspection of the

various lines then under construction in the midland and northern

counties—he took up his residence there, and it continued his home

until the close of his life.

Tapton House is a large, roomy brick mansion, beautifully

situated amid woods, upon a commanding eminence, about a mile to the

northeast of the town of Chesterfield. Green fields

dotted with fine trees slope away from the house in all directions.

The surrounding country is undulating and highly picturesque.

North and south the eye ranges over a vast extent of lovely scenery;

and on the west, looking over the town of Chesterfield, with its

church and crooked spire, the extensive range of the Derbyshire

hills bounds the distance. The Midland Railway skirts the

western edge of the park in a deep rock cutting, and the

locomotive's shrill whistle sounds near at hand as the trains speed

past. The gardens and pleasure-grounds adjoining the house

were in a very neglected state when Mr. Stephenson first went to

Tapton, and he promised himself, when he had secured rest and

leisure from business, that he would put a new face upon both.

The first improvement he made was in cutting a woodland footpath up

the hill-side, by which he at the same time added a beautiful

feature to the park, and secured a shorter road to the Chesterfield

station; but it was some years before he found time to carry into

effect his contemplated improvements in the adjoining gardens and

pleasure-grounds. He had so long been accustomed to laborious

pursuits, and felt himself still so full of work, that he could not

at once settle down into the habit of quietly enjoying the fruits of

his industry.

He had no difficulty in usefully employing his time.

Besides directing the mining operations at Claycross, the

establishment of the lime-kilns at Ambergate, and the construction

of the extensive railways still in progress, he occasionally paid

visits to Newcastle, where his locomotive manufactory was now in

full work, and the proprietors were reaping the advantages of his

early foresight in an abundant measure of prosperity. One of

his most interesting visits to the place was in 1838, on the

occasion of the meeting of the British Association there, when he

acted as one of the Vice-Presidents in the section of Mechanical

Science. Extraordinary changes had taken place in his own

fortunes, as well as in the face of the country, since he had first

appeared before a scientific body in Newcastle—the members of the

Literary and Philosophical Institute—to submit his safety-lamp for

their examination. Twenty-three years had passed over his

head, full of honest work, of manful struggle, and the humble

"colliery engine-wright of the name of Stephenson" had achieved an

almost world-wide reputation as a public benefactor. His

fellow-townsmen, therefore, could not hesitate to recognize his

merits and do honour to his presence. During the sittings of

the Association, the engineer took the opportunity of paying a visit

to Killingworth, accompanied by some of the distinguished savans

whom he numbered among his friends. He there pointed out to

them, with a degree of honest pride, the cottage in which he had

lived for so many years, showing what parts of it had been his

handiwork, and told them the story of the sun-dial over the door,

describing the study and the labour it had cost him and his son to

calculate its dimensions and fix it in its place. The dial had

been serenely numbering the hours through the busy years that had

elapsed since that humble dwelling had been his home, during which

the Killingworth locomotive had become a great working power, and

its contriver had established the railway system, which was now

rapidly becoming extended in all parts of the civilized world.

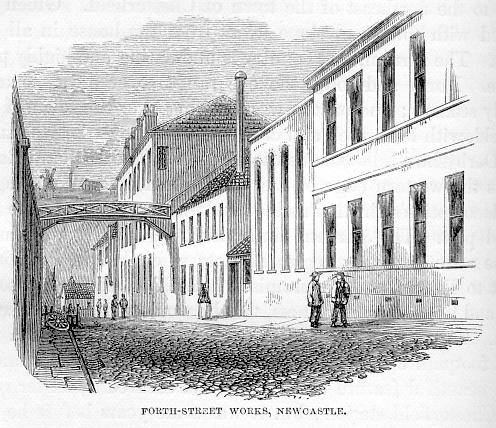

About the same time, his services were very much in request

at the meetings of Mechanics' Institutes held throughout the

northern counties. From a very early period in his history he

had taken an active interest in these valuable institutions.

While residing at Newcastle in 1824, shortly after his locomotive

foundry had been started in Forth Street, he presided at a public

meeting held in that town for the purpose of establishing a

Mechanics' Institute. The meeting was held; but, as George

Stephenson was a man comparatively unknown even in Newcastle at that

time, his name failed to secure "an influential attendance."

Among those who addressed the meeting on the occasion was Joseph

Locke, then his pupil, and afterward his rival as an engineer.

The local papers scarcely noticed the proceedings, yet the

Mechanics' Institute was founded and struggled into existence.

Years passed, and it was felt to be an honour to secure Mr.

Stephenson's presence at any public meetings held for the promotion

of popular education. Among the Mechanics' Institutes in his

immediate neighbourhood at Tapton were those of Belper and

Chesterfield, and at their soirees he was a frequent and a welcome

visitor. On these occasions he loved to tell his auditors of

the difficulties which had early beset him through want of

knowledge, and of the means by which he had overcome them. His

grand text was—PERSEVERE; and there was

manhood in the word.

On more than one occasion the author had the pleasure of

listening to George Stephenson's homely but forcible addresses at

the annual soirees of the Leeds Mechanics' Institute. He was

always an immense favourite with his audiences there. His

personal appearance was greatly in his favour. A handsome,

ruddy, expressive face, lit up by bright dark blue eyes, prepared

one for his earnest words when he stood up to speak, and the cheers

had subsided which invariably hailed his rising. He was not

glib, but he was very impressive. And who, so well as he,

could serve as a guide to the working-man in his endeavours after

higher knowledge? His early life had been all

struggle—encounter with difficulty—groping in the dark after greater

light, but always earnestly and perseveringly. His words were

therefore all the more weighty, since he spoke from the fullness of

his own experience.

Nor did he remain a mere inactive spectator of the

improvements in railway working which increasing experience from day

to day suggested. He continued to contrive improvements in the

locomotive, and to mature his invention of the carriage-brake.

When examined before the Select Committee on Railways in 1841, his

mind seems to have been impressed with the necessity which existed

for adopting a system of self-acting brakes, stating that, in his

opinion, this was the most important arrangement that could be

provided for increasing the safety of railway travelling. "I

believe," he said, "that if self-acting brakes were put upon every

carriage, scarcely any accident could take place." His plan

consisted in employing the momentum of the running train to throw

his proposed brakes into action immediately on the moving power of

the engine being checked. He would also have these brakes

under the control of the guard, by means of a connecting line

running along the whole length of the train, by which they should at

once be thrown out of gear when necessary. At the same time he

suggested, as an additional means of safety, that the signals of the

line should be self-acting, and worked by the locomotives as they

passed along the railway. He considered the adoption of this

plan of so much importance that, with a view to the public safety,

he would even have it enforced upon railway companies by the

Legislature. He was also of opinion that it was the interest

of the companies themselves to adopt the plan, as it would save

great tear and wear of engines, carriages, tenders, and brake-vans,

besides greatly diminishing the risk of accidents upon railways.

While before the same committee, he took the opportunity of

stating his views with reference to railway speeds, about which wild

ideas were then afloat, one gentleman of celebrity having publicly

expressed the opinion that a speed of a hundred miles an hour was

practicable in railway travelling! Not many years had passed

since Mr. Stephenson had been pronounced insane for stating

his conviction that twelve miles an hour could be performed by the

locomotive; but, now that he had established the fact, and greatly

exceeded that speed, he was thought behind the age because he

recommended it to be limited to forty miles an hour. He said:

"I do not like either forty or fifty miles an hour upon any line—I

think it is an unnecessary speed; and if there is danger upon a

railway, it is high velocity that creates it. I should say no

railway ought to exceed forty miles an hour on the most favourable

gradient; but upon a curved line the speed ought not to exceed

twenty-four or twenty-five miles an hour." He had, indeed,

constructed for the Great Western Railway an engine capable of

running fifty miles an hour with a load, and eighty miles without

one. But he never was in favour of a hurricane speed of this

sort, believing it could only be accomplished at an unnecessary

increase both of danger and expense.

"It is true," he observed on other occasions,

"I have said the locomotive engine might be

made to travel a hundred miles an hour, but I always put a

qualification on this, namely, as to what speed would best suit the

public. [p.399] The

public may, however, be unreasonable; and fifty or sixty miles an

hour is an unreasonable speed. Long before railway travelling

became general, I said to my friends that there was no limit to the

speed of the locomotive, provided the works could be made to

stand. But there are limits to the strength of iron,

whether it be manufactured into rails or locomotives, and there is a

point at which both rails and tires must break. Every increase

of speed, by increasing the strain upon the road and the rolling

stock, brings us nearer to that point. At thirty miles a

slighter road will do, and less perfect rolling stock may be run

upon it with safety. But if you increase the speed by say ten

miles, then everything must be greatly strengthened. You must

have heavier engines, heavier and better-fastened rails, and all

your working expenses will be immensely increased. I think I

know enough of mechanics to know where to stop. I know that a

pound will weigh a pound, and that more should not be put upon an

iron rail than it will bear. If you could insure perfect iron,

perfect rails, and perfect locomotives, I grant fifty miles an hour

or more might be run with safety on a level railway. But then

you must not forget that iron, even the best, will 'tire,' and with

constant use will become more and more liable to break at the

weakest point—perhaps where there is a secret flaw that the eye can

not detect. Then look at the rubbishy rails now manufactured

on the contract system—some of them little better than cast metal:

indeed, I have seen rails break merely on being thrown from the

truck on to the ground. How is it possible for such rails to

stand a twenty or thirty ton engine dashing over them at the speed

of fifty miles an hour? No, no,"

he would conclude,

"I am in favour of low speeds because they are safe,

and because they are economical; and you may rely upon it that,

beyond a certain point, with every increase of speed there is a

certain increase in the element of danger."

When railways became the subject of popular discussion, many

new and unsound theories were started with reference to them, which

Stephenson opposed as calculated, in his opinion, to bring discredit

on the locomotive system. One of these was with reference to

what were called "undulating lines." Dr. Lardner, who at an

earlier period was sceptical as to the powers of the locomotive, now

promulgated the idea that a railway constructed with rising and

falling gradients would be practically as easy to work as a line

perfectly level. Mr. Badnell went even beyond him, for he held

that an undulating railway was much better than a level one for

purposes of working. [p.400]

For a time this theory found favour, and the "undulating system" was

extensively adopted; but George Stephenson never ceased to inveigh

against it, and experience has proved that his judgment was correct.

His practice, from the beginning of his career until the end of it,

was to secure a road as nearly as possible on a level, following the

course of the valleys and the natural line of the country;

preferring to go round a hill rather than to tunnel under it or

carry his railway over it, and often making a considerable circuit

to secure good workable gradients. He studied to lay out his

lines so that long trains of minerals and merchandise, as well as

passengers, might be hauled along them at the least possible

expenditure of locomotive power. He had long before

ascertained, by careful experiments at Killingworth, that the engine

expends half its power in overcoming a rising gradient of 1 in 260,

which is about 20 feet in the mile; and that when the gradient is so

steep as 1 in 100, not less than three fourths of its power is

sacrificed in ascending the acclivity. He never forgot the

valuable practical lessons taught him by these early trials, which

he had made and registered long before the advantages of railways

had become recognized. He saw clearly that the longer flat

line must eventually prove superior to the shorter line of steep

gradients as respected its paying qualities. He urged that,

after all, the power of the locomotive was but limited; and,

although he and his son had done more than any other men to increase

its working capacity, it provoked him to find that every improvement

made in it was neutralized by the steep gradients which the new

school of engineers were setting it to overcome. On one

occasion, when Robert Stephenson stated before a Parliamentary

committee that every successive improvement in the locomotive was

being rendered virtually nugatory by the difficult and almost

impracticable gradients proposed on many of the new lines, his

father, on his leaving the witness-box, went up to him, and said,

"Robert, you never spoke truer words than those in all your life."

To this it must be added, that in urging these views George

Stephenson was strongly influenced by commercial considerations.

He had no desire to build up his reputation at the expense of

railway shareholders, nor to obtain engineering éclat by

making "ducks and drakes" of their money. He was persuaded

that, in order to secure the practical success of railways, they

must be so laid out as not only to prove of decided public utility,

but also to be worked economically and to the advantage of their

proprietors. They were not government roads, but private

ventures—in fact, commercial speculations. He therefore

endeavoured to render them financially profitable; and he repeatedly

declared that if he did not believe they could be "made to pay," he

would have nothing to do with them. [p.401]

Nor was he influenced by the sordid consideration merely of what he

could make out of any company that employed him, but in many cases

he voluntarily gave up his claim to remuneration where the promoters

of schemes which he thought praiseworthy had suffered serious loss.

Thus, when the first application was made to Parliament for the

Chester and Birkenhead Railway Bill, the promoters were defeated.

They repeated their application on the understanding that in event

of their succeeding the engineer and surveyor were to be paid their

costs in respect of the defeated measure. The bill was

successful, and to several parties their costs were paid.

Stephenson's amounted to £800, and he very nobly said, "You have had

an expensive career in Parliament; you have had a great struggle;

you are a young company; you can not afford to pay me this amount of

money; I will reduce it to £200, and I will not ask you for the £200

until your shares are at £20 premium; for, whatever may be the

reverses you have to go through, I am satisfied I shall live to see

the day when your shares will be at £20 premium, and when I can

legally and honourably claim that £200." [p.402]

We may add that the shares did eventually rise to the premium

specified, and the engineer was no loser by his generous conduct in

the transaction.

|

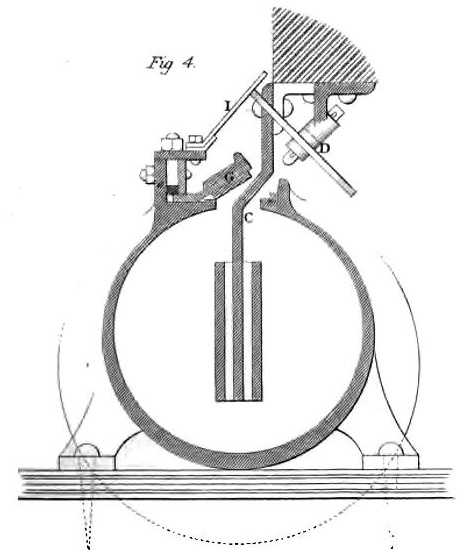

Atmospheric propulsion—drawing showing cross-section of

vacuum pipe, sealable slot and connection to the railway

vehicle (above).

Ed.—an atmospheric railway is a

railway that uses air pressure to provide power for

propulsion. A pneumatic tube is laid between the

rails, with a piston running in it suspended from the

train through a sealable slot in the top of the tube.

By means of stationary pumping engines along the route,

air is exhausted from the tube leaving a vacuum in

advance of the piston, and there is an arrangement for

admitting air to the tube behind the piston so that

atmospheric pressure propels it (and the train to which

it is attached) forward. |

Another novelty of the time with which George Stephenson had

to contend was the proposed substitution of atmospheric pressure for

locomotive steam-power in the working of railways. The idea of

obtaining motion by means of atmospheric pressure originated with

Denis Papin more than a century and a half ago; but it slept until

revived in 1810 by Mr. Medhurst, who published a pamphlet to prove

the practicability of carrying letters and goods by air. In

1824, Mr. Vallance, of Brighton, took out a patent for projecting

passengers through a tube large enough to contain a train of

carriages, the tube ahead of the carriages being previously

exhausted of its atmospheric air. The same idea was afterward

taken up, in 1835, by Mr. Pinkus, an ingenious American.

Several scientific gentlemen, Dr. Lardner and Mr. Clegg among

others, advocated the plan, and an association was formed to carry

it into effect. Shares were created, and £18,000 raised; and a model

apparatus was exhibited in London. Mr. Vignolles took Mr.

Stephenson to see the model; and after carefully examining it, he

observed emphatically, "It won't do: it is only the fixed

engines and ropes over again, in another form; and, to tell you the

truth, I don't think this rope of wind will answer so well as the

rope of wire did." He did not think the principle would stand

the test of practice, and he objected to the mode of applying the

principle. The stationary-engine system was open to serious

objections in whatever form applied; and every day's experience

showed that the fixed engines could not compete with locomotives in

point of efficiency and economy. Stephenson stood by the

locomotive engine, and subsequent experience proved that he was

right.

Messrs. Clegg and Samuda afterward, in 1840, patented their

plan of an atmospheric railway, and they publicly tested its working

on a portion of the West London Railway. The results of the

experiment were considered so satisfactory, that the directors of

the Dublin and Kingstown line adopted it between Kingstown and

Dalkey. The London and Croydon Company also adopted the

atmospheric principle; and their line was opened in 1845. The

ordinary mode of applying the power was to lay between the line of

rails a pipe, in which a large piston was inserted, and attached by

a shaft to the framework of a carriage. The propelling power

was the ordinary pressure of the atmosphere acting against the

piston in the tube on one side, a vacuum being created in the tube

on the other side of the piston by the working of a stationary

engine. Great was the popularity of the atmospheric system;

and still George Stephenson said, "It won't do; it's but a

gimcrack." Engineers of distinction said he was prejudiced,

and that he looked upon the locomotive as a pet child of his own.

"Wait a little," he replied, "and you will see that I am right."

It was generally supposed that the locomotive system was about to be

snuffed out. "Not so fast," said Stephenson. "Let us

wait to see if it will pay." He never believed it would.

It was ingenious, clever, scientific, and all that; but railways

were commercial enterprises, not toys; and if the atmospheric

railway could not work to a profit, it would not do.

Considered in this light, he even went so far as to call it "a great

humbug,"

No one can say that the atmospheric railway had not a fair

trial. The government engineer, General Pasley, did for it

what had never been done for the locomotive—he reported in its

favour, whereas a former government engineer had inferentially

reported against the use of locomotive power on railways. The

House of Commons had also reported in favour of the use of the

steam-engine on common roads; yet the railway locomotive had

vitality enough in it to live through all. "Nothing will beat

it," said George Stephenson, "for efficiency in all weathers, for

economy in drawing loads of average weight, and for power and speed

as occasion may require." The atmospheric system was fairly and

fully tried, and it was found wanting. It was admitted to be

an exceedingly elegant mode of applying power; its devices were very

skilful, and its mechanism was most ingenious. But it was

costly, irregular in action, and, in particular kinds of weather,

not to be depended upon. At best, it was but a modification of

the stationary-engine system, and experience proved it to be so

expensive that it was shortly after entirely abandoned in favour of

locomotive power. [p.404]

One of the remarkable results of the system of railway

locomotion which George Stephenson had by his persevering labours

mainly contributed to establish was the outbreak of the railway

mania toward the close of his professional career. The success

of the first main lines of railway naturally led to their extension

into many new districts; but a strongly speculative tendency soon

began to display itself, which contained in it the elements of great

danger.

The extension of railways had, up to the year 1844, been

mainly effected by men of the commercial classes, and the

shareholders in them principally belonged to the manufacturing

districts—the capitalists of the metropolis as yet holding aloof,

and prophesying disaster to all concerned in railway projects.

The Stock Exchange looked askance upon them, and it was with

difficulty that respectable brokers could be found to do business in

the shares. But when the lugubrious anticipations of the City

men were found to be so entirely falsified by the results—when,

after the lapse of years, it was ascertained that railway traffic

rapidly increased and dividends steadily improved—a change came over

the spirit of the London capitalists. They then invested

largely in railways, the shares in which became a leading branch of

business on the Stock Exchange, and the prices of some rose to

nearly double their original value.

A stimulus was thus given to the projection of farther lines,

the shares in most of which came out at a premium, and became the

subject of immediate traffic. A reckless spirit of gambling

set in, which completely changed the character and objects of

railway enterprise. The public outside the Stock Exchange

became also infected, and many persons utterly ignorant of railways,

but hungering and thirsting after premiums, rushed eagerly into the

vortex. They applied for allotments, and subscribed for shares

in lines, of the engineering character or probable traffic of which

they knew nothing. Provided they could but obtain allotments

which they could sell at a premium, and put the profit—in many cases

the only capital they possessed—into their pockets, it was enough

for them. [p.405] The

mania was not confined to the precincts of the Stock Exchange, but

infected all ranks. It embraced merchants and manufacturers,

gentry and shop-keepers, clerks in public offices, and loungers at

the clubs. Noble lords were pointed at as "stags;" there were

even clergymen who were characterized as "bulls," and amiable ladies

who had the reputation of "bears," in the share-markets. The

few quiet men who remained uninfluenced by the speculation of the

time were, in not a few cases, even reproached for doing injustice

to their families in declining to help themselves from the stores of

wealth that were poured out on all sides.

Folly and knavery were for a time in the ascendant. The

sharpers of society were let loose, and jobbers and schemers became

more and more plentiful. They threw out railway schemes as

lures to catch the unwary. They fed the mania with a constant

succession of new projects. The railway papers became loaded

with their advertisements. The post-office was scarcely able

to distribute the multitude of prospectuses and circulars which they

issued. For a time their popularity was immense. They

rose like froth into the upper heights of society, and the flunkey

Fitz Plushe, by virtue of his supposed wealth, sat among peers and

was idolized. Then was the harvest-time for scheming lawyers,

Parliamentary agents, engineers, surveyors, and traffic-takers, who

were ready to take up any railway scheme however desperate, and to

prove any amount of traffic even where none existed. The

traffic in the credulity of their dupes was, however, the great fact

that mainly concerned them, and of the profitable character of which

there could be no doubt.

Parliament, whose previous conduct in connection with railway

legislation was so open to reprehension, interposed no

check—attempted no remedy. On the contrary, it helped to

intensify the evils arising from this unseemly state of things.

Many of its members were themselves involved in the mania, and as

much interested in its continuance as the vulgar herd of

money-grubbers. The railway prospectuses now issued—unlike the

original Liverpool and Manchester, and London and Birmingham

schemes—were headed by peers, baronets, landed proprietors, and

strings of M.P's. Thus it was found in 1845 that no fewer than

157 members of Parliament were on the lists of new companies as

subscribers for sums ranging from £291,000 downward! The

projectors of new lines even came to boast of their Parliamentary

strength, and of the number of votes which they could command in

"the House." At all events, it is matter of fact, that many

utterly ruinous branches and extensions projected during the mania,

calculated only to benefit the inhabitants of a few miserable

boroughs accidentally omitted from Schedule A, were authorized in

the memorable sessions of 1844 and 1845.

George Stephenson was anxiously entreated to lend his name to

prospectuses during the railway mania, but he invariably refused.

He held aloof from the headlong folly of the hour, and endeavoured

to check it, but in vain. Had he been less scrupulous, and

given his countenance to the numerous projects about which he was

consulted, he might, without any trouble, have thus secured enormous

gains; but he had no desire to accumulate a fortune without labour

and without honour. He himself never speculated in shares.

When he was satisfied as to the merits of an undertaking, he would

sometimes subscribe for a certain amount of capital in

it, when he held on, neither buying nor selling. At a dinner

of the Leeds and Bradford directors at Ben Rydding in October, 1844,

before the mania had reached its height, he warned those present

against the prevalent disposition toward railway speculation.

It was, he said, like walking upon a piece of ice with shallows and

deeps; the shallows were frozen over, and they would carry, but it

required great caution to get over the deeps. He was satisfied

that in the course of the next year many would step on to places not

strong enough to carry them, and would get into the deeps; they

would be taking shares, and afterward be unable to pay the calls

upon them. Yorkshiremen were reckoned clever men, and his

advice to them was to stick together and promote communication in

their own neighbourhood—not to go abroad with their speculations.

If any had done so, he advised them to get their money back as fast

as they could, for if they did not they would not get it at all.

He informed the company, at the same time, of his earliest holding

of railway shares; it was in the Stockton and Darlington Railway,

and the number he held was three—"a very large capital for

him to possess at the time." But a Stockton friend was anxious

to possess a share, and he sold him one at a premium of 33s.;

he supposed he had been about the first man in England to sell a

railway share at a premium.

|

|

|

George Hudson, "The Railway King."

(1800-71) |

During 1845, his son's office in Great George Street, Westminster,

was crowded with persons of various conditions seeking interviews,

presenting very much the appearance of the levee of a minister of

state. The burly figure of Mr. Hudson, the "Railway King,"

surrounded by an admiring group of followers, was often to be seen

there; and a still more interesting person, in the estimation of

many, was George Stephenson, dressed in black, his coat of somewhat

old-fashioned cut, with square pockets in the tails. He wore a

white neck-cloth, and a large bunch of seals was suspended from his

watch-ribbon. Altogether, he presented an appearance of

health, intelligence, and good humour, that it gladdened one to look

upon in that sordid, selfish, and eventually ruinous saturnalia of

railway speculation.

Being still the consulting engineer of several of the older

companies, he necessarily appeared before Parliament in support of

their branches and extensions. In 1845 his name was associated

with that of his son as the engineer of the Southport and Preston

Junction. In the same session he gave evidence in favour of

the Syston and Peterborough branch of the Midland Railway; but his

principal attention was confined to the promotion of the line from

Newcastle to Berwick, in which he had never ceased to take the

deepest interest.

Powers were granted by Parliament in 1845 to construct not

less than 2883 miles of new railways in Britain, at an expenditure

of about forty-four millions sterling! Yet the mania was not

appeased; for in the following session of 1846, applications were

made to Parliament for powers to raise £389,000,000 sterling for the

construction of farther lines; and they were actually conceded to

the extent of 4790 miles (including 60 miles of tunnels), at a cost

of about £120,000,000 sterling. [p.408]

During this session Mr. Stephenson appeared as engineer for only one

new line—the Buxton, Macclesfield, Congleton, and Crewe Railway—a

line in which, as a coal-owner, he was personally interested; and of

three branch lines in connection with existing companies for which

he had long acted as engineer. At the same period all the

leading professional men were fully occupied, some of them appearing

as consulting engineers for upward of thirty lines each!

One of the features of this mania was the rage for "direct

lines" which every where displayed itself. There were "Direct

Manchester," "Direct Exeter," "Direct York," and, indeed, new direct

lines between most of the large towns. The Marquis of Bristol,

speaking in favour of the "Direct Norwich and London" project at a

public meeting at Haverhill, said, "If necessary, they might make a

tunnel beneath his very drawing-room rather than be defeated in

their undertaking!" And the Rev. F. Litchfield, at a meeting

in Banbury on the subject of a line to that town, said, "He had laid

down for himself a limit to his approbation of railways—at least of

such as approached the neighbourhood with which he was connected—and

that limit was, that he did not wish them to approach any nearer to

him than to run through his bedroom, with the bedposts for a

station!" How different was the spirit which influenced

these noble lords and gentlemen but a few years before!

The course adopted by Parliament in dealing with the

multitude of railway bills applied for during the prevalence of the

mania was as irrational as it proved unfortunate. The want of

foresight displayed by both houses in obstructing the railway system

so long as it was based upon sound commercial principles was only

equalled by the fatal facility with which they now granted railway

projects based upon the wildest speculation. Parliament

interposed no check, laid down no principle, furnished no guidance,

for the conduct of railway projectors, but left every company to

select its own locality, determine its own line, and fix its own

gauge. No regard was paid to the claims of existing companies,

which had already expended so large an amount in the formation of

useful railways; and speculators were left at liberty to project and

carry out lines almost parallel with theirs.

The House of Commons became thoroughly influenced by the

prevailing excitement. Even the Board of Trade began to favour

the views of the new and reckless school of engineers. In

their "Report on the Lines projected in the Manchester and Leeds

District," they promulgated some remarkable views respecting

gradients, declaring themselves in favour of the "undulating

system." They there stated that lines of an undulating

character "which gave gradients of 1 in 70 or 1 in 80 distributed

over them in short lengths, may be positively better lines, i.e.,

more susceptible of cheap and expeditious working, than others

which have nothing steeper than 1 in 100 or 1 in 120!" They

concluded by reporting in favour of the line which exhibited the

worst gradients and the sharpest curves, chiefly on the ground that

it could be constructed for less money.

Sir Robert Peel took occasion, when speaking in favour of the

continuance of the Railways Department of the Board of Trade, to

advert to this report in the House of Commons on the 4th of March

following, as containing "a novel and highly important view on the

subject of gradients, which, he was certain, never could have been

taken by any committee of the House of Commons, however

intelligent;" and he might have added, that the more intelligent,

the less likely would they be to arrive at any such conclusion.

When George Stephenson saw this report of the premier's speech in

the newspapers of the following morning, he went forthwith to his

son, and asked him to write a letter to Sir Robert Peel on the

subject. He saw clearly that if such views were adopted, the

utility and economy of railways would be seriously curtailed.

"These members of Parliament," said he, "are now as much disposed to

exaggerate the powers of the locomotive as they were to

underestimate them but a few years ago." Robert accordingly

wrote a letter for his father's signature, embodying the views which

he so strongly entertained as to the importance of flat gradients,

and referring to the experiments conducted by him many years before

in proof of the great loss of working power which was incurred on a

line of steep as compared with easy gradients. It was clear,

from the tone of Sir Robert Peel's speech in a subsequent debate,

that he had carefully read and considered Mr. Stephenson's practical

observations on the subject, though it did not appear that he had

come to any definite conclusion thereon farther than that he

strongly approved of the Trent Valley Railway, by which Tamworth

would be placed upon a direct main line of communication.

The result of the labours of Parliament was a tissue of

legislative bungling, involving enormous loss to the nation.

Railway bills were granted in heaps. Two hundred and

seventy-two additional acts were passed in 1846. Some

authorized the construction of lines running almost parallel with

existing railways, in order to afford the public "the benefits of

unrestricted competition." Locomotive and atmospheric lines,

broad-gauge and narrow-gauge lines, were granted without hesitation.

Committees decided without judgment and without discrimination; and

in the scramble for bills, the most unscrupulous were usually the

most successful. As an illustration of the legislative folly

of the period, Robert Stephenson, speaking at Toronto, in Upper

Canada, some years later, adduced the following instances:

"There was one district through which it was proposed

to run two lines, and there was no other difficulty between them

than the simple rivalry that, if one got a charter, the other might

also. But here, where the committee might have given both,

they gave neither. In another instance, two lines were

projected through a barren country, and the committee gave the one

which afforded the least accommodation to the public. In

another, where two lines were projected to run, merely to shorten

the time by a few minutes, leading through a mountainous country,

the committee gave both. So that, where the committee might

have given both, they gave neither, and where they should have given

neither, they gave both."

Among the many ill effects of the mania, one of the worst was

that it introduced a low tone of morality into railway transactions.

The bad spirit which had been evoked by it unhappily extended to the

commercial classes, and many of the most flagrant swindles of recent

times had their origin in the year 1845. Those who had

suddenly gained large sums without labour, and also without honour,

were too ready to enter upon courses of the wildest extravagance;

and a false style of living arose, the poisonous influence of which

extended through all classes. Men began to look upon railways

as instruments to job with. Persons sometimes possessing

information respecting railways, but more frequently possessing

none, got upon boards for the purpose of promoting their individual

objects, often in a very unscrupulous manner; land-owners, to

promote branch lines through their property; speculators in shares,

to trade upon the exclusive information which they obtained; while

some directors were appointed through the influence mainly of

solicitors, contractors, or engineers, who used them as tools to

serve their own ends. In this way the unfortunate proprietors were

in many cases betrayed, and their property was shamefully

squandered, much to the discredit of the railway system.

One of the most prominent celebrities of the mania was George

Hudson, of York. He was a man of some local repute in that

city when the line between Leeds and York was projected. His

views as to railways were then extremely moderate, and his main

object in joining the undertaking was to secure for York the

advantages of the best railway communication. The company was

not very prosperous at first, and during the years 1840 and 1841 the

shares had greatly sunk in value. Mr. Alderman Meek, the first

chairman, having retired, Mr. Hudson was elected in his stead, and

he very shortly contrived to pay improved dividends to the

proprietors, who asked no questions. Desiring to extend the

field of his operations, he proceeded to lease the Leeds and Selby

Railway at five per cent. That line had hitherto been a losing

concern; so its owners readily struck a bargain with Mr. Hudson, and

sounded his praises in all directions. He increased the

dividends on the York and North Midland shares to ten per cent., and

began to be cited as the model of a railway chairman.

He next interested himself in the North Midland Railway,

where he appeared in the character of a reformer of abuses.

The North Midland shares also had gone to a heavy discount, and the

shareholders were accordingly desirous of securing his services.

They elected him a director. His bustling, pushing,

persevering character gave him an influential position at the board,

and he soon pushed the old members from their stools. He

laboured hard, at much personal inconvenience, to help the concern

out of its difficulties, and he succeeded. The new directors,

recognizing his power, elected him their chairman.

Railways revived in 1842, and public confidence in them as

profitable investments was gradually increasing. Mr. Hudson

had the benefit of this growing prosperity. The dividends in

his lines improved, and the shares rose in value. The

Lord-mayor of York began to be quoted as one of the most capable of

railway directors. Stimulated by his success and encouraged by

his followers, he struck out or supported many new projects—a line

to Scarborough, a line to Bradford, lines in the Midland districts,

and lines to connect York with Newcastle and Edinburgh. He was

elected chairman of the Newcastle and Darlington Railway; and

when—in order to complete the continuity of the main line of

communication—it was found necessary to secure the Durham junction,

which was an important link in the chain, he and George Stephenson

boldly purchased that railway between them, at the price of £88,500.

It was an exceedingly fortunate purchase for the company, to whom it

was worth double the money. The act, though not strictly

legal, proved successful in the issue, and was much lauded.

Thus encouraged, Mr. Hudson proceeded to buy the Brandling Junction

line for £500,000 in his own name—an operation at the time regarded

as equally favourable, though he was afterward charged with

appropriating 1600 of the shares created for the purchase, when

worth £21 premium each. The Great North of England line being

completed, Mr. Hudson had thus secured the entire line of

communication from York to Newcastle, and the route was opened to

the public in June, 1844. On that occasion Newcastle eulogized

Mr. Hudson in its choicest local eloquence, and he was pronounced to

be the greatest benefactor the district had ever known.

The adulation which followed Mr. Hudson would have

intoxicated a stronger and more self-denying man. He was

pronounced the man of the age, and hailed as "the Railway King."

The highest test by which the shareholders judged him was the

dividends that he paid, though subsequent events proved that these

dividends were in many cases delusive, intended only "to make things

pleasant." The policy, however, had its effect. The

shares in all the lines of which he was chairman went to a premium,

and then arose the temptation to create new shares in branch and

extension lines, often worthless, which were issued at a premium

also. Thus he shortly found himself chairman of nearly 600

miles of railway, extending from Rugby to Newcastle, and at the head

of numerous new projects, by means of which paper-wealth could be

created as it were at pleasure. He held in his own hands

almost the entire administrative power of the companies over which

he presided: he was chairman, board, manager, and all. His

admirers for the time, inspired sometimes by gratitude for past

favours, but oftener by the expectation of favours to come,

supported him in all his measures. At the meetings of the

companies, if any suspicious shareholder ventured to put a question

about the accounts, he was snubbed by the chair and hissed by the

proprietors. The Railway King was voted praises, testimonials,

and surplus shares alike liberally, and scarcely a word against him

could find a hearing. He was equally popular outside the

circle of railway proprietors. His entertainments at Albert

Gate were crowded by sycophants, many of them titled; and he went

his rounds of visits among the peerage like a prince.

Of course Mr. Hudson was a great authority on railway

questions in Parliament, to which the burgesses of Sunderland had

sent him. His experience of railways, still little understood,

though the subject of so much legislation, gave value and weight to

his opinions, and in many respects he was a useful member.

During the first years of his membership he was chiefly occupied in

passing the railway bills in which he was more particularly

interested; and in the session of 1845, when he was at the height of

his power, it was triumphantly said of him that "he walked quietly

through Parliament with some sixteen railway bills under his arm."

One of these bills, however, was the subject of a severe

contest—we mean that empowering the construction of the railway from

Newcastle to Berwick. It was almost the only bill in which

George Stephenson was concerned that year. Mr. Hudson

displayed great energy in supporting the measure, and he worked hard

to insure its success both in and out of Parliament; but he himself

attributed the chief merit to Stephenson. He accordingly

suggested to the shareholders that they should present the engineer

with some fitting testimonial in recognition of his services.

Indeed, a Stephenson Testimonial had long been spoken of, and a

committee was formed for raising subscriptions for the purpose as

early as the year 1839. Mr. Hudson now revived the subject,

and appealed to the Newcastle and Darlington, the Midland, and the

York and North Midland Companies, who unanimously adopted the

resolutions which he proposed to them amid "loud applause," but

there the matter ended.

The Hudson Testimonial was a much more taking thing, for

Hudson had it in his power to allot shares (selling at a premium) to

his adulators. But Stephenson pretended to fill no man's

pocket with premiums; he was no creator of shares, and could not

therefore work upon shareholders' gratitude for "favours to come."

The proposed testimonial to him accordingly ended with resolutions

and speeches. The York, Newcastle, and Berwick Board—in other

words, Mr. Hudson—did indeed mark their sense of the "great

obligations" which they were under to George Stephenson for helping

to carry their bill through Parliament by making him an allotment of

thirty of the new shares authorized by the act. But, as

afterward appeared, the chairman had at the same time appropriated

to himself not fewer than 10,894 of the same shares, the premiums on

which were then worth, in the market, about £145,000. This

shabby manner of acknowledging the gratitude of the company to their

engineer was strongly resented by Stephenson at the time, and a

coolness took place between him and Hudson which was never wholly

removed, though they afterward shook hands, and Stephenson declared

that all was forgotten.

Mr. Hudson's brief reign drew to a close. The

saturnalia of 1845 was followed by the usual reaction. Shares

went down faster than they had gone up; the holders of them hastened

to sell in order to avoid payment of the calls, and many found

themselves ruined. Then came repentance, and a sudden return

to virtue. The betting man, who, temporarily abandoning the

turf for the share-market, had played his heaviest stake and lost;

the merchant who had left his business, and the doctor who had

neglected his patients, to gamble in railway stock and been ruined;

the penniless knaves and schemers who had speculated so recklessly

and gained so little; the titled and fashionable people, who had

bowed themselves so low before the idol of the day, and found

themselves deceived and "done;" the credulous small capitalists,

who, dazzled by premiums, had invested their all in railway shares,

and now saw themselves stripped of everything, were grievously

enraged, and looked about them for a victim. In this temper

were shareholders when, at a railway meeting in York, some pertinent

questions were put to the Railway King. His replies were not

satisfactory, and the questions were pushed home. Mr. Hudson

became confused. Angry voices rose in the meeting. A

committee of investigation was appointed. The golden calf was

found to be of brass, and hurled down, Hudson's own toadies and

sycophants eagerly joining the chorus of popular indignation.

Similar proceedings shortly after followed at the meetings of other

companies, and the bubbles having by that time burst, the Railway

Mania thus came to an ignominious end.

While the mania was at its height in England, railways were

also being extended abroad, and George Stephenson continued to be

invited to give the directors of foreign undertakings the benefit of

his advice. One of the most agreeable of his excursions with

that object was his third visit to Belgium in 1845. His

special purpose was to examine the proposed line of the Sambre and

Meuse Railway, for which a concession had been granted by the

Belgian Legislature. Arrived on the ground, he went carefully

over the entire length of the proposed line, by Couvins, through the

Forest of Ardennes, to Rocroi, across the French frontier, examining

the bearing of the coal-field, the slate and marble quarries, and

the numerous iron-mines in existence between the Sambre and the

Meuse, as well as carefully exploring the ravines which extended

through the district, in order to satisfy himself that the best

possible route had been selected. Stephenson was delighted

with the novelty of the journey, the beauty of the scenery, and the

industry of the population. His companions were entertained by

his ample and varied stores of practical information on all

subjects, and his conversation was full of reminiscences of his

youth, on which be always delighted to dwell when in the society of

his more intimate friends. The journey was varied by a visit

to the coal-mines near Jemappe, where Stephenson examined with

interest the mode adopted by the Belgian miners of draining the

pits, inspecting their engines and braking machines, so familiar to

him in early life.

The engineers of Belgium took the opportunity of the

engineer's visit to invite him to a magnificent banquet at Brussels.

The Public Hall, in which they entertained him, was gaily decorated

with flags, prominent among which was the Union Jack, in honour of

their distinguished guest. A handsome marble pedestal,

ornamented with his bust crowned with laurels, stood at one end of

the room. The chair was occupied by M. Massui, the Chief

Director of the National Railways of Belgium; and the most eminent

scientific men of the kingdom were present. Their reception of

the "father of railways" was of the most enthusiastic description.

Stephenson was greatly pleased with the entertainment. Not the

least interesting incident of the evening was his observing, when

the dinner was about half over, the model of a locomotive engine

placed upon the centre table, under a triumphal arch. Turning

suddenly to his friend Sopwith, he exclaimed, "Do you see the

'Rocket?'" It was, indeed, the model of that celebrated locomotive;

and the engineer prized the delicate compliment thus paid him

perhaps more than all the enconiums of the evening.

The next day (April 5th) King Leopold invited him to a

private interview at the palace. Accompanied by Mr. Sopwith,

he proceeded to Laaken, and was cordially received by his majesty.

The king immediately entered into familiar conversation with him,

discussing first the railway project which had been the object of

his visit to Belgium, and then the structure of the Belgian

coal-fields, his majesty expressing his sense of the great

importance of economy in a fuel which had become indispensable to

the comfort and well-being of society, which was the basis of all

manufactures, and the vital power of railway locomotion. The

subject was always a favourite one with George Stephenson, and,

encouraged by the king, he proceeded to explain to him the

geological structure of Belgium, the original formation of coal, its

subsequent elevation by volcanic forces, and the vast amount of

denudation. In describing the coal-beds he used his hat as a

sort of model to illustrate his meaning, and the eyes of the king

were fixed upon it as he proceeded with his description. The

conversation then passed to the rise and progress of trade and

manufactures, Stephenson pointing out how closely they everywhere

followed the coal, being mainly dependent upon it, as it were, for

their very existence.

The king seemed greatly pleased with the interview, and at

its close expressed himself as obliged by the interesting

information which the engineer had communicated. Shaking hands

cordially with both the gentlemen, and wishing them success in their

important undertakings, he bade them adieu. As they were

leaving the palace, Stephenson, bethinking him of the model by which

he had just been illustrating the Belgian coal-fields, said to his

friend, "By-the-by, Sopwith, I was afraid the king would see the

inside of my hat; it's a shocking bad one!"

George Stephenson paid a farther visit to Belgium in the

course of the same year, on the business of the West Flanders

Railway, and he had scarcely returned from it ere he was requested

to proceed to Spain, for the purpose of examining and reporting upon

a scheme then on foot for constructing "the Royal North of Spain

Railway." A concession had been made by the Spanish government

of a line of railway from Madrid to the Bay of Biscay, and a

numerous staff of engineers was engaged in surveying the proposed

line. The directors of the company had declined making the

necessary deposits until more favourable terms had been secured; and

Sir Joshua Walmsley, on their part, was about to visit Spain and

press the government on the subject. George Stephenson, whom

he consulted, was alive to the difficulties of the office which Sir

Joshua was induced to undertake, and offered to be his companion and

adviser on the occasion, declining to receive any recompense beyond

the simple expenses of the journey. He could only arrange to

be absent for six weeks, and he set out from England about the

middle of September, 1845.

The party was joined at Paris by Mr. Mackenzie, the

contractor for the Orleans and Tours Railway, then in course of

construction, who took them over the works and accompanied them as

far as Tours. They soon reached the great chain of the

Pyrenees, and crossed over into Spain. It was on a Sunday

evening, after a long day's toilsome journey through the mountains,

that the party suddenly found themselves in one of those beautiful

secluded valleys lying amid the Western Pyrenees. A small

hamlet lay before them, consisting of some thirty or forty houses

and a fine old church. The sun was low on the horizon, and

under the wide porch, beneath the shadow of the church, were seated

nearly all the inhabitants of the place. They were dressed in

their holiday attire. The bright bits of red and amber colour

in the dresses of the women, and the gay sashes of the men, formed a

striking picture, on which the travellers gazed in silent

admiration. It was something entirely novel and unexpected.

Beside the villagers sat two venerable old men, whose canonical hats

indicated their quality as village pastors. Two groups of

young women and children were dancing outside the porch to the

accompaniment of a simple pipe, and within a hundred yards of them

some of the youths of the village were disporting themselves in

athletic exercises, the whole being carried on beneath the fostering

care of the old church, and with the sanction of its ministers.

It was a beautiful scene, and deeply moved the travellers as they

approached the principal group. The villagers greeted them

courteously, supplied their present wants, and pressed upon them

some fine melons, brought from their adjoining gardens. George

Stephenson used afterward to look back upon that simple scene, and

speak of it as one of the most charming pastorals he had ever

witnessed.

They shortly reached the site of the proposed railway,

passing through Irun, St. Sebastian, St. Andero, and Bilbao, at

which places they met deputations of the principal inhabitants who

were interested in the object of their journey. At Raynosa

Stephenson carefully examined the mountain passes and ravines

through which a railway could be made. He rose at break of

day, and surveyed until the darkness set in, and frequently his

resting-place at night was the floor of some miserable hovel.

He was thus laboriously occupied for ten days, after which he

proceeded across the province of Old Castile toward Madrid,

surveying as he went. The proposed plan included the purchase

of the Castile Canal, and that property was also examined. He

next proceeded to El Escorial, situated at the foot of the Guadarama

Mountains, through which he found it would be necessary to construct

two formidable tunnels; added to which, he ascertained that the

country between El Escorial and Madrid was of a very difficult and

expensive character to work through. Taking these

circumstances into account, and looking at the expected traffic on

the proposed line, Sir Joshua Walmsley, acting under the advice of

Mr. Stephenson, offered to construct the line from Madrid to the Bay

of Biscay on condition that the requisite land was given to the

company for the purpose; that they should be allowed every facility

for cutting such timber belonging to the crown as might be required

for the purposes of the railway; and also that the materials

required from abroad for the construction of the line should be

admitted free of duty. In return for these concessions the

company offered to clothe and feed several thousand convicts while

engaged in the execution of the earthworks. General Narvaez,

afterward Duke of Valencia, received Sir Joshua Walmsley and Mr.

Stephenson on the subject of their proposition, and expressed his

willingness to close with them; but it was necessary that other

influential parties should give their concurrence before the scheme

could be carried into effect. The deputation waited ten days

to receive the answer of the Spanish government, but no answer of

any kind was vouchsafed. The authorities, indeed, invited them

to be present at a Spanish bull-fight, but that was not quite the

business Stephenson had gone all the way to Spain to transact, and

the offer was politely declined. The result was that

Stephenson dissuaded his friend from making the necessary deposit at

Madrid. Besides, he had by this time formed an unfavourable

opinion of the entire project, and considered that the traffic would

not amount to one eighth of the estimate.

Mr. Stephenson was now anxious to be in England. During

the journey from Madrid he often spoke with affection of friends and

relatives, and when apparently absorbed by other matters he would

revert to what he thought might then be passing at home. Few

incidents worthy of notice occurred on the journey homeward, but one

may be mentioned. While travelling in an open conveyance

between Madrid and Vittoria, the driver urged his mules down hill at

a dangerous pace. He was requested to slacken speed; but,

suspecting his passengers to be afraid, he only flogged the brutes

into a still more furious gallop. Observing this, Stephenson

coolly said, "Let us try him on the other tack; tell him to show us

the fastest pace at which Spanish mules can go." The rogue of

a driver, when he found his tricks of no avail, pulled up and

proceeded at a more moderate speed for the rest of the journey.

Urgent business required Mr. Stephenson's presence in London

on the last day of November. They travelled, therefore, almost

continuously, day and night, and the fatigue consequent on the

journey, added to the privations endured by the engineer while

carrying on the survey among the Spanish mountains, began to tell

seriously on his health. By the time he reached Paris he was

evidently ill, but he nevertheless determined on proceeding.

He reached Havre in time for the Southampton boat, but when on board

pleurisy developed itself, and it was necessary to bleed him freely.

After a few weeks' rest at home, however, he gradually recovered,

though his health remained severely shaken.

――――♦―――― |

|

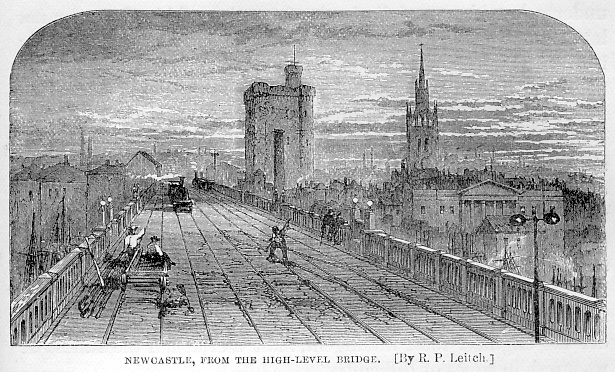

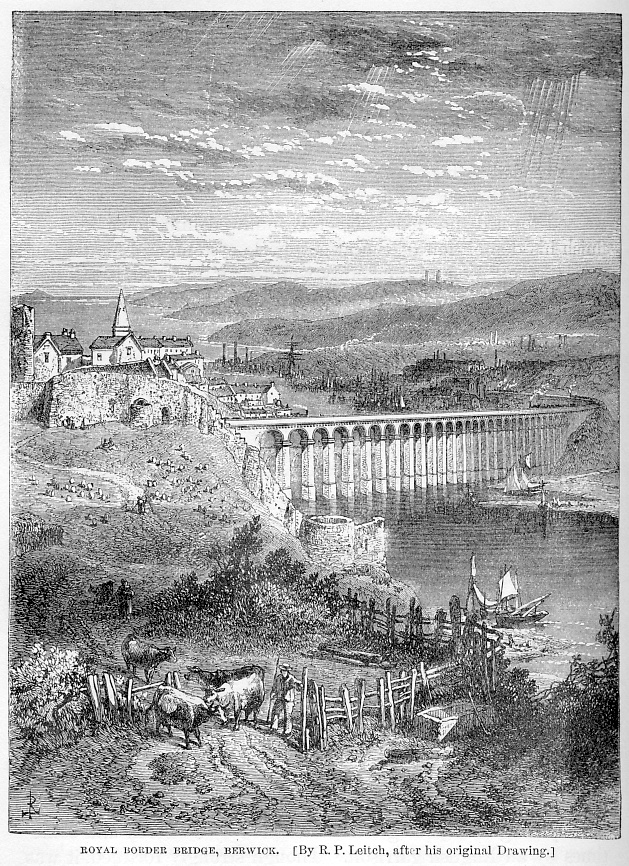

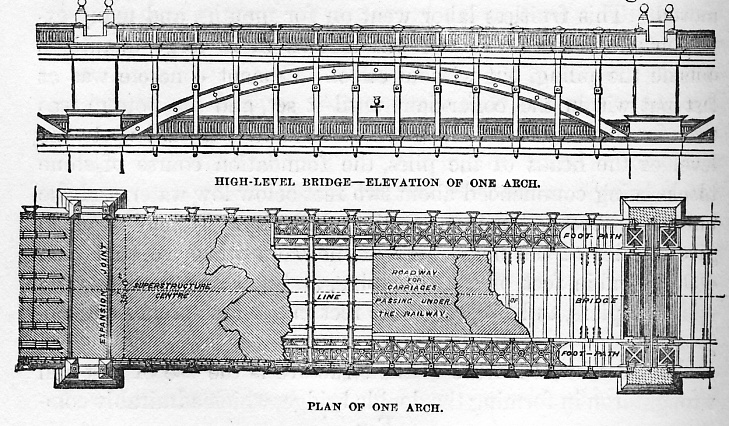

CHAPTER XVII.

ROBERT STEPHENSON'S CAREER—THE STEPHENSONS AND BRUNEL—EAST COAST

ROUTE TO SCOTLAND—ROYAL BORDER BRIDGE, BERWICK—HIGH-LEVEL BRIDGE,

NEWCASTLE.

THE

career of George Stephenson was drawing to a close. He had for

some time been gradually retiring from the more active pursuit of

railway engineering, and confining himself to the promotion of only

a few undertakings, in which he took a more than ordinary personal

interest. In 1840, when the extensive main lines in the

Midland districts had been finished and opened for traffic, he

publicly expressed his intention of withdrawing from the profession.

He had reached sixty, and, having spent the greater part of his life

in very hard work, he naturally desired rest and retirement in his

old age. There was the less necessity for his continuing "in

harness," as Robert Stephenson was now in full career as a leading

railway engineer, and his father had pleasure in handing over to

him, with the sanction of the companies concerned, nearly all the

railway appointments which he held.

Robert Stephenson amply repaid his father's care. The

sound education of which he had laid the foundations at school,

improved by his subsequent culture, but more than all by his

father's example of application, industry, and thoroughness in all

that he undertook, told powerfully in the formation of his character

not less than in the discipline of his intellect. His father

had early implanted in him habits of mental activity, familiarized

him with the laws of mechanics, and carefully trained and stimulated

his inventive faculties, the first great fruits of which, as we have

seen, were exhibited in the triumph of the "Rocket" at Rainhill.

"I am fully conscious in my own mind," said the son at a meeting of

the Mechanical Engineers at Newcastle in 1858,

"how greatly my civil engineering has been regulated

and influenced by the mechanical knowledge which I derived directly

from my father, and the more my experience has advanced, the more

convinced I have become that it is necessary to educate an engineer

in the workshop. That is, emphatically, the education which

will render the engineer most intelligent, most useful, and the

fullest of resources in times of difficulty."

Robert Stephenson was but twenty-six years old when the

performances of the "Rocket" established the practicability of steam

locomotion on railways. He was shortly after appointed

engineer of the Leicester and Swannington Railway; after which, at

his father's request, he was made joint engineer with himself in

laying out the London and Birmingham Railway, and the execution of

that line was afterward entrusted to him as sole engineer. The

stability and excellence of the works of that railway, the

difficulties which had been successfully overcome in the course of

its construction, and the judgment which was displayed by Robert

Stephenson throughout the whole conduct of the undertaking to its

completion, established his reputation as an engineer, and his

father could now look with confidence and pride upon his son's

achievements. From that time forward, father and son worked

together cordially, each jealous of the other's honour; and on the

father's retirement it was generally recognized that, in the sphere

of railways, Robert Stephenson was the foremost man, the safest

guide, and the most active worker.

Robert Stephenson was subsequently appointed engineer of the

Eastern Counties, the Northern and Eastern, and the Blackwall

Railways, besides many lines in the midland and southern districts.

When the speculation of 1844 set in, his services were, of course,

greatly in request. Thus, in one session, we find him engaged

as engineer for not fewer than thirty-three new schemes.

Projectors thought themselves fortunate who could secure his name,

and he had only to propose his terms to obtain them. The work

which he performed at this period of his life was indeed enormous,

and his income was large beyond any previous instance of engineering

gain. But much of the labour done was mere hackwork of a very

uninteresting character. During the sittings of the committees

of Parliament, much time was also occupied in consultations, and in

preparing evidence or in giving it.

Joseph Locke, civil engineer (1805-60)

The crowded, low-roofed committee-rooms of the old houses of

Parliament were altogether inadequate to accommodate the press of

perspiring projectors of bills, and even the lobbies were sometimes

choked with them. To have borne that noisome atmosphere and

heat would have tested the constitutions of salamanders, and

engineers were only human. With brains kept in a state of

excitement during the entire day, no wonder their nervous systems

became unstrung. Their only chance of refreshment was during

an occasional rush to the bun and sandwich stand in the lobby,

though sometimes even that resource failed them. Then, with

mind and body jaded—probably after undergoing a series of

consultations upon many bills after the rising of the committees the

exhausted engineers would seek to stimulate nature by a late,

perhaps a heavy dinner. What chance had any ordinary

constitution of surviving such an ordeal? The consequence was,

that stomach, brain, and liver were alike injured, and hence the men

who bore the heat and brunt of those struggles—Stephenson, Brunel,

Locke, and Errington—have already all died, comparatively young men.

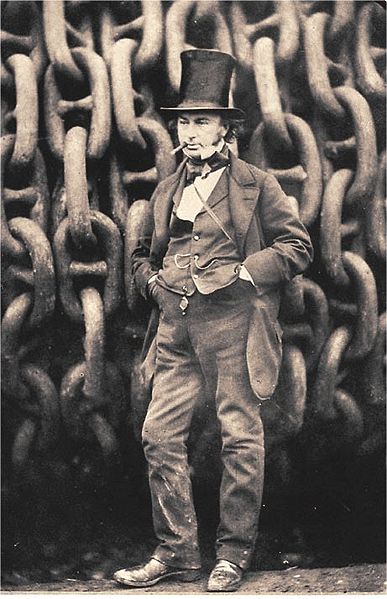

Isambard Kingdom Brunel against the launching chains

of the Great Eastern at Millwall in

1857.

In mentioning the name of Brunel, we are reminded of him as

the principal rival and competitor of Robert Stephenson. Both

were the sons of distinguished men, and both inherited the fame and

followed in the footsteps of their fathers. The Stephensons

were inventive, practical, and sagacious; the Brunels ingenious,

imaginative, and daring. The former were as thoroughly English

in their characteristics as the latter perhaps were as thoroughly

French. The fathers and the sons were alike successful in

their works, though not in the same degree. Measured by

practical and profitable results, the Stephensons were

unquestionably the safer men to follow.

Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel were destined

often to come into collision in the course of their professional

life. Their respective railway districts "marched" with each

other, and it became their business to invade or defend those

districts, according as the policy of their respective boards might

direct. The gauge of 7 feet fixed by Brunel for the Great

Western Railway, so entirely different from that of 4 feet 8½ inches

adopted by the Stephensons on the Northern and Midland lines, [p.424]

was from the first a great cause of contention. But Brunel had

always an aversion to follow any man's lead; and that another

engineer had fixed the gauge of a railway, or built a bridge, or

designed an engine in one way, was of itself often a sufficient

reason with him for adopting an altogether different course.

Robert Stephenson, on his part, though less bold, was more

practical, preferring to follow the old routes, and to tread in the

safe steps of his father.

Mr. Brunel, however, determined that the Great Western should

be a giant's road, and that travelling should be conducted upon it

at double speed. His ambition was to make the best road that

imagination could devise, whereas the main object of the

Stephensons, both father and son, was to make a road that would

pay. Although, tried by the Stephenson test, Brunel's

magnificent road was a failure so far as the shareholders in the

Great Western Company were concerned, the stimulus which his

ambitious designs gave to mechanical invention at the time proved a

general good. The narrow-gauge engineers exerted themselves to

quicken their locomotives to the utmost. They improved and

re-improved them. The machinery was simplified and perfected.

Outside cylinders gave place to inside; the steadier and more rapid

and effective action of the engine was secured, and in a few years

the highest speed on railways went up from thirty to about fifty

miles an hour. For this rapidity in progress we are in no

small degree indebted to the stimulus imparted to the narrow-gauge

engineers by Mr. Brunel.

It was one of the characteristics of Brunel to believe in the