|

"The literary man

exercises much power in the world. He helps to

form the opinions of other men; indeed, he makes public

opinion. All other powers have in modern times

become weaker, while this has been waxing stronger from

day to day. Kings are being superseded by books,

priests by magazines, and diplomatists by newspapers.

Perhaps bookmen and editors now wield more intellectual

power than all the other crafts combined."

"Good rules may do much, but good models far more;

for in the latter we have instruction in action—wisdom

at work."

Samuel Smiles. |

|

|

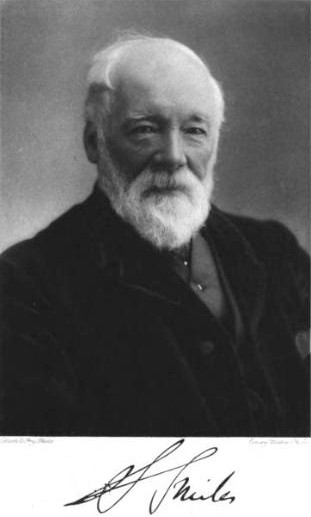

SAMUEL SMILES,

LL.D

(1812-1904) |

|

SAMUEL

SMILES is best known

today as a prolific author of books that extol the virtues of

self-help, character and duty, and of biographies lauding the

achievements of famous civil and mechanical engineers among whom are

Brindley, Smeaton, Rennie, Boulton, Watt, Telford and the

Stephensons, but, oddly, not Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

His books—particularly that on self help—were influential in

their day, as is evidenced by their wide popularity and translation

into other languages and a number of his titles remain available in

modern reprints. Alas, as a biographer Smiles suffers from an

unwillingness to undertake an objective critical analysis of his

subjects, selecting only material that presents them favourably.

But with that caveat, his books, which are very readable, provide an

interesting and informative perspective on industrialisation during

the Industrial Revolution and the Victorian era.

|

" . . . . they were mainly

self-educated: Smeaton and Watt being mathematical

instrument makers, Telford a stonemason, and Brindley

and Rennie millwrights; force of character and bent of

genius enabling each to carve out his career in his own

way. There was very little previous practice to

serve for their guide. When they were called upon

to undertake works of an entirely original character,

and could not find an old road, they had to make a new

one. This threw them upon their resources, and

compelled them to be inventive: it practised their

powers and disciplined their skill, and in course of

time the habitual encounter with difficulties brought

fully out their character as men, as well as their

genius as engineers."

Smiles on 'The Engineers.' |

Smiles trained as a doctor, but through lack of work traded

his scalpel for the pen (fellow Scot Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did

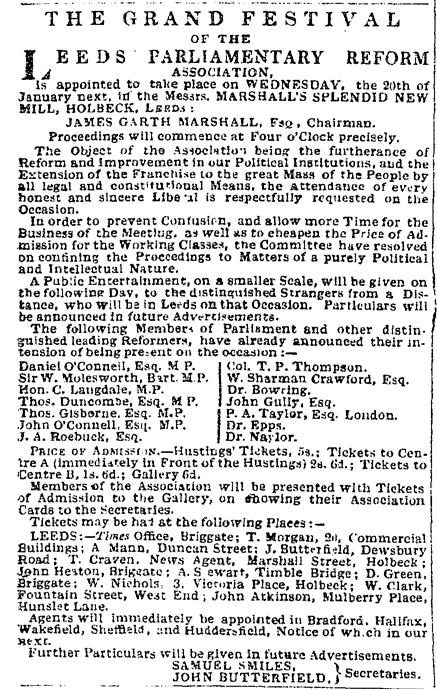

likewise). In his early life he held reforming views. In 1838

he followed Robert Nicoll into the

post of Editor of the Leeds Times, a journal for which Nicoll

had written radical editorials

exhorting the need for

sorely-needed political and economic reform. In like manner,

in 1840, Smiles became Secretary

to the Leeds Parliamentary Reform Association, an organisation that

supported the objectives of Chartism

(universal suffrage for all men over the age of 21; equal-sized

electoral districts; voting by secret ballot; an end to the need of

MPs to qualify for Parliament, other than by winning an election;

pay for MPs; and annual Parliaments). However, Smiles did not

endorse the policy of "physical force Chartism" put forward by

Feargus O'Connor and George Julian Harney.

During the 1850s Smiles drifted away from promoting radical

parliamentary reform, advocating instead individual self

improvement, as is epitomised in the book for which he is probably

best known, Self Help . . . .

|

". . . . Whatever is done

for men or classes, to a certain extent takes away the

stimulus and necessity of doing for themselves; and

where men are subjected to over-guidance and

over-government, the inevitable tendency is to render

them comparatively helpless. Even the best

institutions can give a man no active help.

Perhaps the most they can do is, to leave him free to

develop himself and improve his individual condition

. . . ."

. . . our socialist "Nanny State"

take note — from

Self-Help |

In 1845 Smiles relinquished editorship of the Leeds Times

to become Secretary to the Leeds and Thirsk Railway; this, coupled

with a meeting with George Stephenson (who he appears to have

idolised), probably sparked his interest in recording the

achievements of our leading civil and mechanical engineers of the

era. Nine years later he took up the position of Secretary to the South-Eastern Railway.

Smiles retired from railway service in 1866 to become President of the

National Provident Institution, a position that he held until

suffering a debilitating stroke in 1871. Through perseverance

he eventually recovered his ability to speak and to write,

sufficiently to enable him to resume his literary career.

|

"Good advice has its weight: but

without the accompaniment of a good example it is of

comparatively small influence; and it will be found that

the common saying of 'Do as I say, not as I do,' is

usually reversed in the actual experience of life.

All persons are more or less apt to learn through the

eye rather than the ear; and, whatever is seen in fact,

makes a far deeper impression than anything that is

merely read or heard. This is especially the case

in early youth, when the eye is the chief inlet of

knowledge. Whatever children see they

unconsciously imitate. They insensibly come to

resemble those who are about them—as insects take the

colour of the leaves they feed on."

Smiles on 'learning by example'— from

Self-Help |

The following

contemporary articles give brief summaries of Smiles's literary life and achievements.

――――♦――――

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE

Vol. 76 (May, 1888)

Taken from "London as a Literary Centre" by R. R. Bowker.

THERE is one

historian, or biographer, whom it is difficult to classify, because

he has made a place by himself. Dr. Samuel Smiles, the author

of “Self-Help” and “Character” and “Thrift” and “Duty”, is a man who

seems to have practised what he preaches, and is a very good

exemplar of those homely virtues. His “smithy,” as he calls

his study, is at West Kensington, and here, at seventy-five, of

which age his white hair and white beard tell tales, he still keeps

at work hammering out books.

He began at it fifty years ago. Born in John Knox’s

town of Haddington, he started as a surgeon at his native place, and

there published in 1838 a common-sense little book on "Physical

Education". His income was not large either from pills or pen;

he bettered it somewhat by becoming a journalist and editor of the

Leeds Times; but desiring more promising opportunity with his

marriage, he found it in 1845 in the new work of railway

organization as secretary of a local railway, afterward merged in

the North-Eastern system.

|

"It was one of the last lovely days of

autumn, when the faint breath of Summer was still

lingering among the woods and fields, as if loath to

depart from the earth she had gladdened; the blackbird

was still piping his mellifluous song in the hedges and

coppice, whose foliage was tinted in purple, russet, and

brown, with just enough of green to give that perfect

autumnal tint, so beautifully pictorial, but impossible

to paint in words. The beech-nuts were dropping

from the trees, and crackled under foot, and a rich,

damp smell rose from the decaying leaves by the

road-side."

Smiles pictures Autumn. |

Railway work engaged his work-day hours till 1866, when he

retired from the service of the South-eastern Railway on pension,

and it led him to his true vocation as a writer. Meeting

George Stephenson, he resolved to become his biographer, and as he

visited places on railway business often in vacation times, he

looked up carefully and personally all the local knowledge of the

boy and the man. This Life, printed in 1857 by Mr. Murray, was

his introduction to fame, five editions appearing within a year.

During the free-trade agitation he had spoken much in the

West Riding, and he had also become a favourite lecturer at

mechanics’ institutes; these lectures he reworked into “Self-Help”,

but they were rejected by several publishers, who declared that

during the war (in the Crimea) no one would read books. The

success of the Life “changed all that.” Over 20,000 copies of

“Self-Help”, issued in 1859, were called for in the first year:

150,000 have been sold by the English publishers. It has been

translated into seventeen languages, including Czech and Japanese;

and in Italy alone the sale has reached 47,000 copies.

|

"It is difficult to form a proper

estimate of the influence of Carlyle on modern

literature. Doubtless it has been very great.

His books have been vehemently attacked and discussed,

and scarcely defended. He has let the noise spend

itself, and left his ideas to make their own way in the

world. The influence which his writings have

exercised upon others has been of a latent kind, almost

a silent influence, notwithstanding the great éclat with

which his works have been received. You very often

find his ideas reappearing dressed up by others in

various forms, sometimes under the aristocratic, and

sometimes under the democratic form; but it is easy to

recognize the traces of his thoughts in the most

remarkable works in modern English literature.

Tennyson is the most eminent of living English poets;

who knows how much of his peculiar talent and its

direction may be due to the influence of Carlyle?

Who knows how much even Disraeli may owe to Carlyle for

the qualities of his political romances, though perhaps

he would be the last to acknowledge the influence.

Carlyle has contributed, perhaps more than any other

writer, to put an extinguisher upon the Byronic school;

and, thanks to the views which he has enunciated on

literature and art, to elevate Wordsworth—as much

admired now as he was formerly despised—upon the ruins

of the Satanic school."

Smiles on Thomas Carlyle . . . from

Brief Biographies. |

During his railway years his successive books, including the “Lives

of the Engineers” and the several industrial biographies, were all

the work of evening hours, and this industry was continued till

1871, when a stroke of paralysis gave him warning, and compelled him

to take absolute rest for three years. He now works mornings

only, taking much exercise by walking, and plenty of sleep by night,

induced by the reading of novels. From constant and wide

reading he accumulates masses of material, which he gradually sorts

under subjects and into chapters, and his embarrassment now is of

more wealth of material than the years may give him time to use.

Dr. Smiles at home, with his north of England wife, is the

picture of the Scotchman, solid-headed, pleasant-voiced, with a bit

of the burr, hearty and kindly and a little gruff in manner; for

vacation he takes to travel on the Continent, finding there,

however, such materials as have given us his Huguenot histories. |

|

――――♦――――

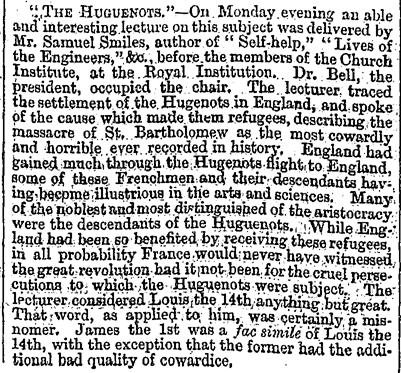

THE TIMES

18th April, 1904.

DEATH OF DR. SAMUEL SMILES.

――――♦――――

We regret to announce that the veteran Dr. Samuel Smiles died at

12-30 on Saturday at his house in Pembroke-gardens, Kensington.

He had entered his 92nd year. The biographer of the great

captains of industry, was himself an admirable example of what may

be achieved by industry and perseverance. Few, indeed have

passed such a long period in harness, for he spent upwards of 70

years of his protracted career in active intellectual and other

labours.

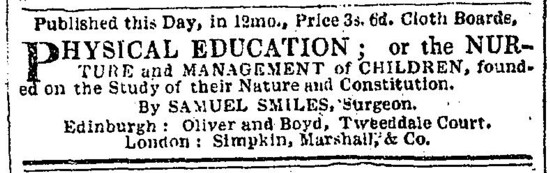

Advertisement for Smiles's "Physical Education", 1837.

Samuel Smiles was born on December 23, 1812, at Haddington.

The Smileses were descended from an old Cameronian who met his death

at the hands of Charles II's Lifeguards at the battle of Pentland.

Some of his strong qualities were perpetuated in his descendants;

but it is said, also, that Samuel Smiles's family owed much to the

intelligence, shrewdness, and force of character at their mother,

who, when left a widow with 11 children continued successfully to

conduct a small business.

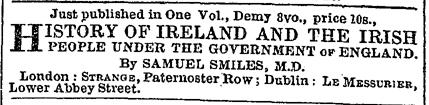

Advertisement for Smiles's History of Ireland, 1844.

Samuel was educated at the Haddington Grammar School and at

Edinburgh University. Although he had literary and artistic

leanings, he resolved on pursuing the profession of medicine.

Settling down in his native town, he practised as a medical man with

but small success, seeing that he was the youngest of eight doctors

in a remarkably small and healthy population of 3,000 persons.

He consequently sought to add to his income by lecturing on

practical chemistry, physiology, and natural history. He also

studied music and painting, wrote articles for the Edinburgh

Weekly Chronicle, and produced his first work, "Physical

Education," which, by the way, he published at his own expense.

Feeling that there was no prospect of succeeding in Haddington, he

thought of emigrating to Australia, but finally went to Holland and

Germany instead, remaining abroad for about a year. On his

return, in 1837, he became editor of the Leeds Times in

succession to his friend Robert Nicoll.

His salary was only £200 a year, and he supplemented it by writing,

lecturing at mechanics' institutes, &c. He further acted as

secretary to the Leeds Parliamentary Reform Association, and took an

active part in the Anti-Corn Law agitation from its very

commencement. While at Leeds he wrote a "History of Ireland

and the Irish People" (1844); he lectured at the Manchester

Athenæum; "stumped" the West Riding on the Corn Law question; and

conducted an adult class at the Zion School, Holbeck.

Leeds Parliamentary Reform Association, 1840.

Dr. Smiles married in 1845, and as his editorial salary could

not support a wife as well a himself, he relinquished his editorship

and accepted the post of assistant secretary to the Leeds and Thirsk

Railway. This appointment he continued to hold until 1854,

when he became secretary to the South-Eastern Railway, finally

retiring from the railway service in 1866. During his

association with these railways Dr. Smiles not only enjoyed a

satisfactory income, but he had opportunities of studying the

characters of the remarkable men whose memoirs he afterwards wrote.

It is no slight tribute to his energy, however, to state that all

the works which he produced between 1844 and 1866 were written in

the evenings, for his position as a secretary to a great railway

company fully occupied his business hours. It was during his

stay at Leeds that he came into contact with George Stephenson and

conceived the idea of writing his "Life." This task he

eventually accomplished is 1857; the work passed through five

editions in its first year, and it has been more or less in demand

ever since. "Self-Help," Dr. Smiles's most successful book,

was published in 1859. It was the outcome of numerous lectures

on subjects related to the main issue. Some very young men in

Leeds, who met in the evening for self-education, had asked Smiles

"to talk to them a bit," and though really written before, it was

only after the success of Stephenson's "Life" that "Self-Help"

appeared. The fact is that it was twice refused by the

publishers before the run upon the Stephenson volume gave them

confidence. Of "Self-Help" 20,000 copies were sold during the

first year, and by 1889 the sales had reached 150,000 copies, while

the book had been translated into 17 languages. It drew forth

tributes from all classes and conditions of men, including the

Italian statesman Signor Menabrea and the Japanese Professor

Nakamura.

In 1861 Smiles produced his "Workmen's Earnings, Strikes, and

Savings"; and two years later appeared his important work, in three

volumes, "Lives of the Engineers, with an Account of their Principal

Works." He was now an indefatigable author and compiler, and

the following books followed each other in rapid

succession:—"Industrial Biography," being a description of iron

workers and tool workers, 1863; "James Brindley and the Early

Engineers," 1864; "Lives of Bolton and Watt," together with a

history of the steam engine, 1865; and "Life of Thomas Telford,"

1867. Then he turned into a different vein for a time, and, as

the result of special investigation, wrote in 1867 "The Huguenots;

their Settlements, Churches, and Industries in England and Ireland."

This was followed up a few years later by "The Huguenots in France

and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, with a visit to the

country of the Vaudois." "Character," which belongs to the

same series of books as "Self-Help," appeared in 1871.

Lecture report, 1867.

A check was now put upon Smiles's activity, for in November,

1871, he was stricken down by a paralysis, which for a considerable

period entirely disabled him. The doctors ordered him complete

rest from literary work for three years. It was a severe blow

to the patient, but he obeyed the mandate, and the treatment pursued

proved thoroughly successful. In travelling and resting by

turns, and in drawing at the Bethnal-green Museum, he passed the

time of his enforced retirement from literary work. Few indeed

can be the men who have sustained a severe stroke of paralysis at 60

years of age and yet have recovered sufficiently to undertake 20

years of close mental work and to be hale and hearty when in their

ninth decade.

|

"Those lofty gods whom we had worshipped

and bowed down before,—those gifted children of genius

whose eyes gazed eagerly into the unseen, and penetrated

its depths far beyond our ken,—when we approach them

closer, and know them more intimately, become stripped

of their halo of glory. We find that they are but

men,—fallible, frail, and erring,—tempest-tossed by

passion and desire,—stumbling and halt, and often blind

and decrepit. We worship no more. The earth

which, seen from a distance, looks a beautiful moon,

when the foot is on it, is but rocks, clods, and 'Paris

mud'!

Sad indeed is the impression left on the mind by reading the

brief records of some of these unhappy children of

genius: gifted, but unhappy; loftily endowed, but fitful

and capricious; with the aspirations of an angel, but

the low appetites of a brute; daringly speculative, but

grovellingly sensual;—such, in a few words, was the life

of Edgar Allan Poe: a being full of misery, but all

beaten out upon his own anvil; a man gifted as few are,

but without faith or devotion, and without any earnest

purpose in life."

Smiles on Edgar Allan Poe . . . . from

Brief Biographies. |

"Thrift"—with its lessons of prudence for working men—the

first book produced after Smiles's illness, was published in 1875,

and in the following year appeared that interesting work entitled

"Thomas Edward: Life of a Scotch Naturalist." Edward was a

remarkable man, who, in the midst of the humblest surroundings, made

himself a great naturalist, and became a fellow of the Linnæan

Society of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh. The

publication of Smiles's biography awakened so much sympathy in

Edward's favour that a pension of £50 a year was conferred upon him.

The memoir of "Robert Dick, Baker of Thurso, Geologist and

Botanist," was issued in 1878, and the same year witnessed the

appearance of "George Moore, Merchant and Philanthropist."

Then in 1880 came "Duty," with its illustrations of courage,

patience and endurance.

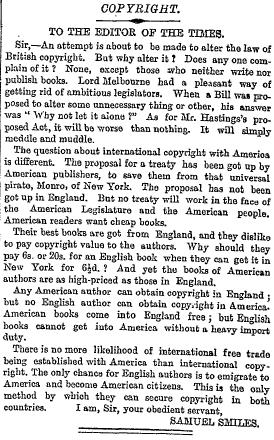

The Times, 25th April,

1881.

In 1883 Dr. Smiles edited the autobiography of James Nasmyth,

the inventor of the steam hammer, a man of original genius. In

1884 he published his "Men of Invention and Industry," and in 1887

his "Life and Labour; or, Characteristics of Men of Industry,

Culture and Genius." His memoir "John Murray," issued in 1891,

gave a graphic sketch of a well-known and remarkable publishing

house; and in the same year the author produced his biography of "Jasmin,

Barber, Poet, and Philanthropist." Jacques Jasmin was a modern

Gasoon port, who in one of his own works has given a humorous

account of the poverty and privations of his early life. His

poems were full of beauty and power, and were crowned by the French

Academy in 1852. His life and struggles interested Smiles

deeply. Thenceforward Smiles wrote but little. His wife

died in 1900, and he lived in retirement.

The mere recital of Dr. Smiles's works will show what a full

and active life his must have been. And, in addition to

writing his books, he found time to contribute frequently to the

Quarterly Review and other periodicals. In recognition of

his literary efforts the honorary degree of LL.D. was conferred upon

him by Edinburgh University in 1878, and in 1897, for the same

reason, he received from the King of Servia the Cross of Knight

Commander of the Order of St. Sava.

Dr. Smiles's works are not only admirable for their simple

and yet forcible literary style, but for many useful and practical

lessons which they enforce. They are wholesome and stimulating

books, and their whole tendency is conducive to the inculcation of

sound principles of life, and the building up of a manly and upright

character. They must long continue to exercise a salutary

influence over a nation of workers such as that to which the author

himself was proud to belong.

The funeral will be at Brompton Cemetery tomorrow, at 11:30.

――――♦――――

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

The following list is not exhaustive; a number of

Smiles's titles

appear in different editions.

|

|

The

Life of George Stephenson, 1857 |

|

The

Story of The Life of George Stephenson, 1859:

(abridgement of the above) |

|

"Self-Help," 1859 |

|

Brief

biographies, Boston, 1860:

(articles reprinted from periodicals such as the

Quarterly Review) |

|

Workmen's Earnings, Strikes, and Savings, 1861 |

|

Lives

of the Engineers, with an Account of their Principal Works, 3 vol,

London 1863

Vol 1, Early engineers - James Brindley, Sir Cornelius Vermuyden,

Sir Hugh Myddleton, Capt John Perry.

Vol 2, Harbours, Lighthouses and Bridges -

John Smeaton and John Rennie, (1761-1821)

Vol 3, History of Roads - John Metcalfe and

Thomas Telford |

|

Industrial Biography, iron workers and tool makers, 1863:

includes lives of Andrew Yarranton, Benjamin

Huntsman, Dud Dudley, Henry Maudslay,

Joseph Clement, etc. |

|

James

Brindley and the Early Engineers, 1864 |

|

Boulton and Watt, 1865 |

|

The

Huguenots: Their Settlements, Churches and Industries in England and

Ireland, 1867 |

|

Life

of Thomas Telford, 1867 |

|

"Character," 1871 |

|

Lives

of the Engineers, new ed. in 5 vols, 1874

(includes the lives of Stephenson and Boulton and

Watt) |

|

Life

of a Scotch Naturalist: Thomas Edward, 1875 |

|

"Thrift", 1875 |

|

George Moore, Merchant and Philanthropist, 1878 |

|

Robert Dick, Baker of Thurso, Geologist and Botanist, 1878 |

|

"Duty", 1880 |

|

Men of

Invention and Industry, 1884:

Phineas Pett, Francis Pettit Smith, John Harrison, John Lombe,

William Murdoch, Frederick Koenig,

The Walter family of The Times,

William Clowes (Printer), Charles Bianconi, and chapters on

Industry

in Ireland, Shipbuilding in Belfast, Astronomers and students in

humble life |

|

James

Nasmyth, engineer, an autobiography, ed. Samuel Smiles, 1885 |

|

Life

and Labour; or, Characteristics of Men of Industry, Culture and

Genius,

1887 |

|

A

Publisher and his Friends. Memoir and Correspondence of the

Late John

Murray, 1891 |

|

Jasmin. Barber, Poet, Philanthropist, 1891 |

|

Josiah Wedgwood, his Personal History, 1894 |

|

The

Autobiography of Samuel Smiles, LL.D., ed. T. Mackay, 1905 |

――――♦――――

<>

|