|

[Previous page]

CHAPTER XX.

ROBERT STEPHENSON'S VICTORIA BRIDGE, LOWER CANADA—ILLNESS AND DEATH. |

|

GEORGE

STEPHENSON bequeathed to

his son his valuable collieries, his share in the engine manufactory

at Newcastle, and his large accumulation of savings, which, together

with the fortune he had himself amassed by railway work, gave Robert

the position of an engineer millionaire—the first of his order.

He continued, however, to live in a quiet style; and although he

bought occasional pictures and statues, and indulged in the luxury

of a yacht, he did not live up to his income, which went on

accumulating until his death.

There was no longer the necessity for applying himself to the

laborious business of a Parliamentary engineer, in which he had now

been occupied for some fifteen years. Shortly after his

father's death, Edward Pease recommended him to give up the more

harassing work of his profession; and his reply (15th of June, 1850)

was as follows:

"The suggestion which your kind note contains is

quite in accordance with my own feelings and intentions respecting

retirement; but I find it a very difficult matter to bring to a

close so complicated a connection in business as that which has been

established by twenty-five years of active and arduous professional

duty. Comparative retirement is, however, my intention, and I

trust that your prayer for the Divine blessing to grant me happiness

and quiet comfort will be fulfilled. I can not but feel deeply

grateful to the Great Disposer of events for the success which has

hitherto attended my exertions in life, and I trust that the future

will also be marked by a continuance of His mercies."

Although Robert Stephenson, in conformity with this expressed

intention, for the most part declined to undertake new business, he

did not altogether lay aside his harness, and he lived to repeat his

tubular bridges both in Egypt and Canada. The success of the

tubular system, as adopted at Menai and Conway, was such as to

recommend it for adoption wherever great span was required, and the

peculiar circumstances connected with the navigation of the Nile and

the St. Lawrence may be said to have compelled its adoption in

carrying railways across both those rivers.

Two tubular bridges were built after our engineer's designs

across the Nile, near Damietta, in Lower Egypt. That near

Ben-ha contains eight spans or openings of 80 feet each, and two

centre spans, formed by one of the largest swing-bridges ever

constructed, the total length of the swing-beam being 157 feet, a

clear waterway of 60 feet being provided on either side of the

centre pier. The only novelty in these bridges consisted in

the road being carried upon the tubes instead of within them, their

erection being carried out in the usual manner by means of workmen,

materials, and plant sent out from England. The Tubular Bridge

constructed in Canada, after Mr. Stephenson's designs, was of a much

more important character, and deserves a fuller description.

The important uses of railways had been recognized at an

early period by the inhabitants of North America, and in the course

of about thirty years more than 25,000 miles of railway, mostly

single, were constructed in the United States alone. The

Canadians were more deliberate in their proceedings, and it was not

until the year 1840 that their first railway, 14 miles in length,

was constructed between Laprairie and St. John's, for the purpose of

connecting Lake Champlain with the River St. Lawrence. From

this date, however, new lines were rapidly projected; more

particularly the Great Western of Canada, and the Atlantic and St.

Lawrence (now forming part of the Grand Trunk), until in the course

of a few years Canada had a length of nearly 2000 miles of railway

open or in course of construction, intersecting the provinces almost

in a continuous line from Rivière du Loup, near the mouth of the St.

Lawrence, to Port Sarnia, on the shores of Lake Huron.

But there still remained one most important and essential

link to connect the lines on the south of the St. Lawrence with

those on the north, and at the same time place the city of Montreal

in direct railway connection with the western parts of Canada.

The completion of this link was also necessary in order to maintain

the commercial communication of Canada with the rest of the world

during five months in every year; for, though the St. Lawrence in

summer affords a splendid outlet to the ocean—toward which the

commerce of the colony naturally tends—the frost in winter is so

severe, that during that season Canada is completely frozen in, and

the navigation hermetically closed by the ice.

The Grand Trunk Railway was designed to furnish a line of

land communication along the great valley of the St. Lawrence at all

seasons, following the course of the river, and connecting the

principal towns of the colony. But stopping short on the north

shore, nearly opposite Montreal, with which it was connected by a

dangerous and often impracticable ferry, it was felt that, until the

St. Lawrence was bridged by a railway, the Canadian system of

railways was manifestly incomplete. But how to bridge this

wide and rapid river! Never before, perhaps, was a problem of

such difficulty proposed for solution by an engineer. Opposite

Montreal, the St. Lawrence is about two miles wide, running at the

rate of about ten miles an hour; and at the close of each winter it

carries down the ice of 2000 square miles of lakes and rivers, with

their numerous tributaries.

As early as the year 1846, the construction of a bridge at

Montreal was strongly advocated by the local press as the only means

of connecting that city with the projected Atlantic and St. Lawrence

Railway. But the difficulties of executing such a work seemed

almost insurmountable to those best acquainted with the locality.

The greatest difficulty was apprehended from the tremendous shoving

and pressure of the ice at the break-up of winter. At such

times, opposite Montreal, the whole river is packed with huge blocks

of ice, and it is often seen piled up to a height of from 40 to 50

feet along the banks, placing the surrounding country under water,

and occasionally doing severe damage to the massive stone buildings

erected along the noble river front of the city.

But no other expedient presented itself but a bridge, and a

survey was made accordingly at the instance of the Hon. John Young,

one of the directors of the railway. A period of colonial

depression having shortly after occurred, the project slept for a

time, and it was not until six years later, in 1852, when the Grand

Trunk Railway was under construction, that the subject was again

brought under discussion. In that year, Mr. Alexander M. Ross,

who had superintended the construction of Robert Stephenson's

tubular bridge at Conway, visited Canada, and inspected the site of

the proposed structure, when he at once formed the opinion that a

tubular bridge carrying a railway was the most suitable means of

crossing the St. Lawrence, and connecting Montreal with the lines on

the north of the river.

The directors felt that such a work would necessarily be of a

most formidable and difficult character, and before coming to any

conclusion they determined to call to their assistance Mr. Robert

Stephenson, as the engineer most competent to advise them in the

matter. Mr. Stephenson considered the subject of so much

interest and importance that, in the summer of 1853, he proceeded to

Canada to inquire as to all the facts, and examine carefully the

site of the proposed work. He then formed the opinion that a

tubular bridge across the river was not only practicable, but by far

the most suitable for the purpose intended, and early in the

following year he sent an elaborate report on the whole subject to

the directors of the railway. The result was the adoption of

his recommendation and the erection of the Victoria Bridge, of which

Robert Stephenson was the designer and engineer, and Mr. A. M. Ross

the joint and resident engineer in directly superintending the

execution of the undertaking. The details of the plans were

principally worked out in Mr. Stephenson's office in London, under

the superintendence of his cousin, Mr. George Robert Stephenson,

while the iron-work was for the most part constructed at the Canada

Works, Liverpool, from whence it was shipped, ready for being fixed

in position on the spot.

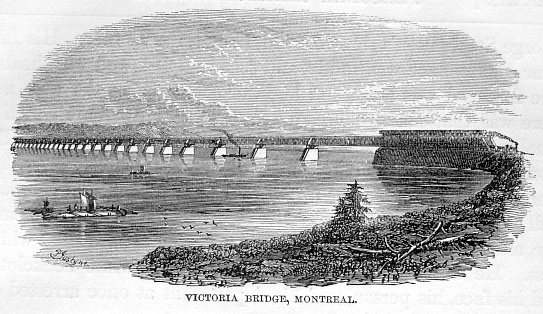

The Victoria Bridge is, without exception, the greatest work

of its kind in the world. For gigantic proportions, and vast

length and strength, there is nothing to compare with it in ancient

or modern times. The entire bridge, with its approaches, is

only about sixty yards short of two miles in length, being five

times longer than the Britannia Bridge across the Menai Straits,

seven and a half times longer than Waterloo Bridge, and more than

ten times longer than Chelsea Bridge. The two-mile tube across

the St. Lawrence rests on twenty-four piers, which, with the

abutments, leave twenty-five spaces or spans for the several parts

of the tube. Twenty-four of these spans are 242 feet wide; the

centre span—itself a huge bridge—being 330 feet. The road is

carried within the tube 60 feet above the level of the river, so as

not to interfere with its navigation.

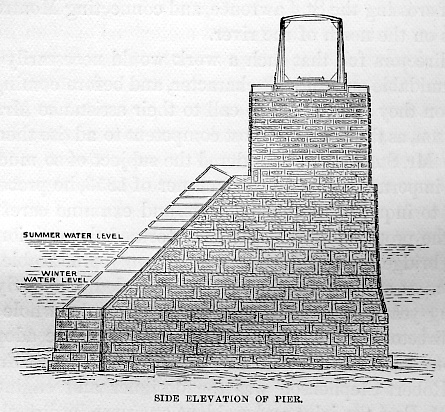

As one of the principal difficulties apprehended in the

erection of the bridge was that arising from the tremendous

"shoving" and ramming of the ice at the break-up of winter, the

plans were carefully designed so as to avert all danger from this

cause. Hence the peculiarity in the form of the piers, which,

though greatly increasing their strength for the purpose intended,

must be admitted to detract considerably from the symmetry of the

structure as a whole. The western face of each pier—that is,

the up-river side—has a large wedge-shaped cutwater of stone-work,

presenting an inclined plane toward the current, for the purpose of

arresting and breaking up the ice-blocks, and thereby preventing

them from piling up and damaging the tube carrying the railway.

The piers are of immense strength. Those close to the

abutments contain about 6000 tons of masonry each, while those which

support the great centre tube contain about 12,000 tons. The

former are 15 feet wide, and the latter 18. Scarcely a block

of stone used in the piers is less than seven tons in weight, while

many of those opposed to the force of the breaking-up ice weigh

fully ten tons.

As might naturally be expected, the getting in of the

foundations of these enormous piers in so wide and rapid a river was

attended with many difficulties. To give an idea of the

water-power of the St. Lawrence, it may be mentioned that when the

river comes down in its greatest might, large stone boulders

weighing upward of a ton are rolled along by the sheer force of the

current. The depth of the river, however, was not so great as

might be supposed, varying from only five to fifteen feet during

summer, when the foundation-work was carried on.

The method first employed to get in the foundations was by

means of dams or caissons, which were constructed on shore, floated

into position, and scuttled over the places at which the foundations

were to be laid, thus at once forming a nucleus from which the dams

could be constructed. The first of such dams was floated, got

into position, scuttled, and sunk, and the piling fairly begun, on

the 19th of June, 1854. By the 15th of the following month the

sheet-piling and puddling was finished, when the pumping of the

water out of the enclosed space by steam-power was proceeded with,

and in a few hours the bed of the river was laid almost dry, the toe

of every pile being distinctly visible. By the 22d the first

stone of the pier was laid, and on the 14th of August the masonry

was above water-level.

The getting in of the foundations of the other piers was

proceeded with in like manner, though frequently interrupted by

storms, inundations, and collisions of timber-rafts, which

occasionally carried away the moorings of the dams.

Considerable difficulty was in some places experienced from the huge

boulder-stones lying in the bed of the river, to remove which

sometimes cost the divers several months of hard labour. In

getting in the foundations of the later piers, the method first

employed of sinking the floating caissons in position was abandoned,

and the dams were constructed of "crib-work," [p.479]

which was found more convenient, and less liable to interruption by

accident from collision or otherwise.

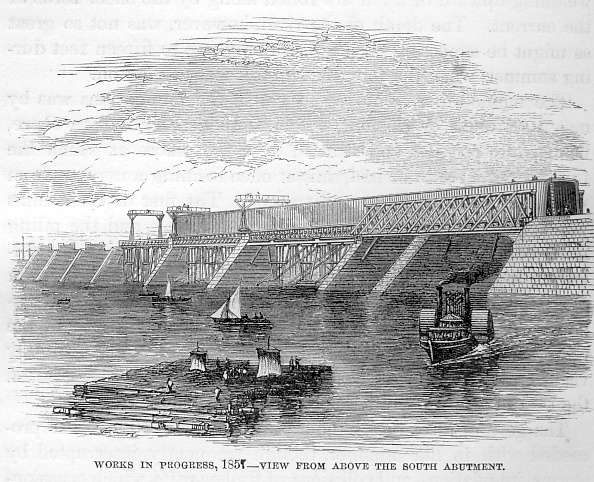

By the spring of 1857 a sufficient number of piers had been

finished to enable the erection of the tubes to be proceeded with.

The operations connected with this portion of the work were also of

a novel character. Instead of floating the tubes between the

piers and raising them into position by hydraulic power, as at

Conway and Menai, which the rapid current of the St. Lawrence would

not permit, the tubes were erected in situ on a staging

prepared for the purpose, as shown in the following engraving. |

|

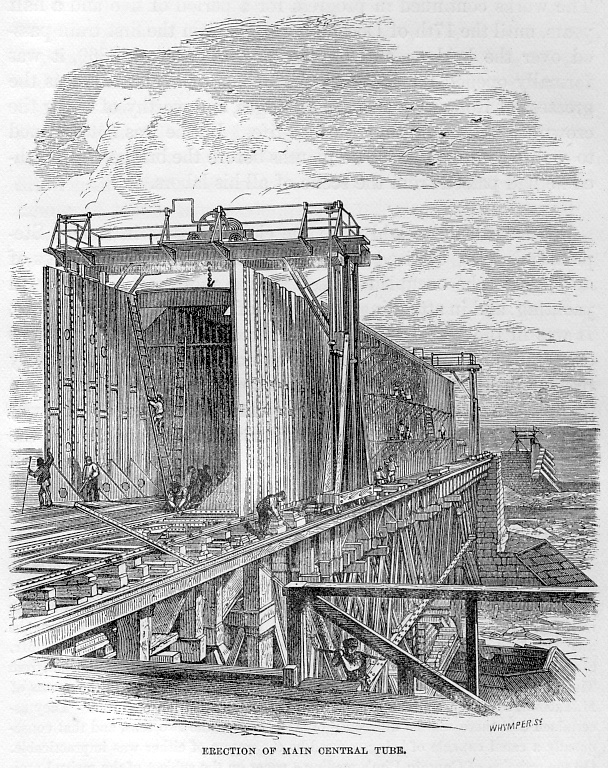

Floating scows, each 60 feet by 20, were moored in position,

and kept in their place by piles sliding in grooves. These

piles, when firmly fixed in the bed of the river, were bolted to the

sides of the scows, and the tops were levelled to receive the sills

upon which the framing carrying the truss and platform was erected.

Timbers were laid on the lower chords of the truss, forming a

platform 24 feet wide, closely planked with deals. The upper

chords carried rails, along which moved the "travellers" used in

erecting the tubes. The plates forming the bottom of each tube

having been accurately laid and riveted, and adjusted to level and

centre by oak wedges, the erection of the sides was next proceeded

with, extending outward from the centre on either side, this work

being closely followed by the plating of the top. Each tube

between the respective pairs of piers was in the first place erected

separate and independent of its adjoining tubes; but after

completion, the tubes were joined in pairs and firmly bolted to the

masonry over which they were united, their outer ends being placed

upon rollers so arranged on the adjoining piers that they might

expand or contract according to variations of temperature.

The work continued to make satisfactory progress down to the

spring of 1858, by which time fourteen out of the twenty-four piers

were finished, together with the formidable abutments and approaches

to the bridge. Considerable apprehensions were entertained as

to the security of the piers and the unfinished parts of the work at

the usual breaking-up of the ice. We take the following

account from a letter written by Mr. Ross to Mr. Stephenson

descriptive of the scene.

"On the 29th of March, the ice

above Montreal began to show signs of weakness, but it was not until

the 31st that a general movement became observable, which continued

for an hour, when it suddenly stopped, and the water rose rapidly.

On the following day, at noon, a grand movement commenced; the

waters rose about four feet in two minutes, up to a level with many

of the Montreal streets. The fields of ice at the same time

were suddenly elevated to an incredible height; and so overwhelming

were they in appearance, that crowds of the townspeople, who had

assembled on the quay to watch the progress of the flood, ran for

their lives. This movement lasted about twenty minutes, during

which the jammed ice destroyed several portions of the quay wall,

grinding the hardest blocks to atoms. The embanked approaches

to the Victoria Bridge had tremendous forces to resist. In the

full channel of the stream, the ice in its passage between the piers

was broken up by the force of the blow immediately on its coming in

contact with the cutwaters. Sometimes thick sheets of ice were

seen to rise up and rear on end against the piers, but by the force

of the current they were speedily made to roll over into the stream,

and in a moment after were out of sight. For the two next days

the river was still high, until on the 4th of April the waters

seemed suddenly to give way, and by the following day the river was

flowing clear and smooth as a millpond, nothing of winter remaining

except the masses of bordage ice which were strewn along the shores

of the stream. On examination of the piers of the bridge, it

was found that they had admirably resisted the tremendous pressure;

and though the timber "crib-work" erected to facilitate the placing

of floating pontoons to form the dams was found considerably

disturbed and in some places seriously damaged, the piers, with the

exception of one or two heavy stone blocks, which were still

unfinished, escaped uninjured. One block of many tons' weight

was carried to a considerable distance, and must have been torn out

of its place by sheer force, as several of the broken fragments were

found left in the pier."

Toward the end of January, 1859, the plating of the bottom of

the great central tube was begun. The execution of this part

of the undertaking was of a very formidable and difficult character.

The gangs of men employed upon it were required to work night and

day, though the season was mid-winter, as it was of great importance

to the navigation that the staging should be removed by the time

that the ice broke up and the river became open. The night

gangs were lighted at their work by wood-fires filling huge

braziers, the bright glow of which illumined the vast snow-covered

ice-field in the midst of which they worked at so lofty an

elevation; and the sight as well as the sounds of the hammering and

riveting, the puffing of the steam-engines, and the various

operations thus carried on, presented a scene the like of which has

rarely been witnessed. The work was not conducted without

considerable risk to the men, arising from the intense cold.

The temperature was often 20° below zero, and notwithstanding that

they all worked in thick gloves, and that care was taken to protect

every exposed part, many of them were severely frostbitten.

Sometimes, when thick mist rose from the river, they would become

covered with icicles, and be driven from their work.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, the laying of the great

central tube made steady progress. By the 17th of February the

first pair of side-plates was erected; on the 28th, the bottom was

riveted and completed; 180 feet of the sides was also in place, and

100 feet of the top was plated; and on the 21st of March the whole

of the plating was finished. A few days later the wedges were

knocked away, and the tube hung suspended between the adjoining

piers. On the 18th of May following the staging was all

cleared away, with the moored scows and the crib-work, and the

centre span of the bridge was again clear for the navigation of the

river.

|

|

The first stone of the bridge was laid on the 22d of July,

1854. The works continued in progress for a period of five and

a half years, until the 17th of December, 1859, when the first train

passed over the bridge; and on the 25th of August, 1860, it was

formally opened for traffic by the Prince of Wales. It was the

greatest of Robert Stephenson's bridges, and worthy of being the

crowning and closing work of his life. But he was not destined

to see its completion. Two months before the bridge was

finished he had passed from the scene of all his labours.

We have little to add as to the closing events in Robert

Stephenson's life. Retired in a great measure from the

business of an engineer, he occupied himself for the most part in

society, in yachting, and in attending the House of Commons and the

Clubs. It was in the year 1847 that he entered the House of

Commons as member for Whitby; but he does not seem to have been very

regular in his attendance, and only appeared on divisions when there

was a "whip" of the party to which he belonged. He was a

member of the Sewage and Sanitary Commissions, and of the Commission

which sat on Westminster Bridge. He very seldom addressed the

House, and then only on matters relating to engineering. The

last occasions on which he spoke were on the Suez Canal [p484]

and the cleansing of the Serpentine.

Besides constructing the railway between Alexandria and

Cairo, he was consulted, like his father, by the King of Belgium as

to the railways of that country; and he was made Knight of the Order

of Leopold because of the improvements which he had made in

locomotive engines, so much to the advantage of the Belgian system

of inland transit. He was consulted by the King of Sweden as

to the railway between Christiana and Lake Miösen, and in

consideration of his services was decorated with the Grand Cross of

the Order of St. Olaf. He also visited Switzerland, Piedmont,

and Denmark, to advise as to the system of railway communication

best suited for those countries. At the Paris Exhibition of

1855 the Emperor of France decorated him with the Legion of Honour

in consideration of his public services; and at home the University

of Oxford made him a Doctor of Civil Laws. In 1855 he was

elected President of the Institute of Civil Engineers, which office

he held with honour and filled with distinguished ability for two

years, giving place to his friend Mr. Locke at the end of 1857.

Mr. Stephenson was frequently called upon to act as

arbitrator between contractors and railway companies, or between one

company and another, great value being attached to his opinion on

account of his weighty judgment, his great experience, and his

upright character; and we believe his decisions were invariably

stamped by the qualities of impartiality and justice. He was

always ready to lend a helping hand to a friend, and no petty

jealousy stood between him and his rivals in the engineering world.

The author remembers being with Mr. Stephenson one evening at his

house in Gloucester Square when a note was put into his hand from

his friend Brunel, then engaged in his fruitless efforts to launch

the Great Eastern. It was to ask Stephenson to come

down to Blackwall early next morning, and give him the benefit of

his judgment. Shortly after six next morning Stephenson was in

Scott Russell's building-yard, and he remained there until dusk.

About midday, while superintending the launching operations, the

balk of timber on which he stood canted up, and he fell up to his

middle in the Thames mud. He was dressed as usual, without

great-coat (though the day was bitter cold), and with only thin

boots upon his feet. He was urged to leave the yard and change

his dress, or at least dry himself; but, with his usual disregard of

health, he replied, "Oh, never mind me; I'm quite used to this sort

of thing;" and he went paddling about in the mud, smoking his cigar,

until almost dark, when the day's work was brought to an end.

The result of this exposure was an attack of inflammation of the

lungs, which kept him to his bed for a fortnight.

He was habitually careless of his health, and perhaps he

indulged in narcotics to a prejudicial extent. Hence he often

became "hipped," and sometimes ill. When Mr. Sopwith

accompanied him to Egypt in the Titania, in 1856, he

succeeded in persuading Mr. Stephenson to limit his indulgence in

cigars and stimulants, and the consequence was that by the end of

the voyage he felt himself, as he said, "quite a new man."

Arrived at Marseilles, he telegraphed from thence a message to Great

George Street, prescribing certain stringent and salutary rules for

observance in the office there on his return. But he was of a

facile, social disposition, and the old associations proved too

strong for him. When be sailed for Norway in the autumn of

1859, though then ailing in health, he looked a man who had still

plenty of life in him. By the time he returned his fatal

illness had seized him. He was attacked by congestion of the

liver, which first developed itself in jaundice, and then ran into

dropsy, of which he died on the 12th of October, in the fifty-sixth

year of his age. He was buried by the side of Telford in

Westminster Abbey, amid the departed great men of his country, and

was attended to his resting-place by many of the intimate friends of

his boyhood and his manhood. Among who assembled round his

grave were some of the greatest men of thought and action in

England, who embraced the sad occasion to pay the last mark of their

respect to this illustrious son of one of England's greatest

working-men.

It would be out of keeping with the subject thus drawn to a

conclusion to pronounce any panegyric on the character and

achievements of George and Robert Stephenson. These, for the

most part, speak for themselves ; and both were emphatically true

men, exhibiting in their lives many valuable and sterling qualities.

No beginning could have been less promising than that of the

elder Stephenson. Born in a poor condition, yet rich in

spirit, he was from the first compelled to rely upon himself, every

step of advance which he made being conquered by patient labour.

Whether working as a brakesman or an engineer, his mind was always

full of the work in hand. He gave himself thoroughly up to it.

Like the painter, he might say that he had become great "by

neglecting nothing." Whatever he was engaged upon, he was as

careful of the details as if each were itself the whole. He

did all thoroughly and honestly. There was no "stamping" with

him. When a workman, he put his brains and labour into his

work; and when a master, he put his conscience and character into

it. He would have no slop-work executed merely for the sake of

profit. The materials must be as genuine as the workmanship

was skilful. The structures which he designed and executed

were distinguished for their thoroughness and solidity; his

locomotives were famous for their durability and excellent working

qualities. The engines which he sent to the United States in

1832 are still in good condition; and even the engines built by him

for the Killingworth Colliery, upward of thirty years since, are

working there to this day. All his work was honest,

representing the actual character of the man.

He was ready to turn his hand to anything—shoes and clocks,

railways and locomotives. He contrived his safety-lamp with

the object of saving pitmen's lives, and periled his own life in

testing it. With him to resolve was to do. Many men knew

far more than he, but none was more ready forthwith to apply what he

did know to practical purposes. It was while working at

Willington as a brakesman that he first learned how best to handle a

spade in throwing ballast out of the ships' holds. This casual

employment seems to have left upon his mind the most lasting

impression of what "hard work" was; and he often used to revert to

it, and say to the young men about him, "Ah, ye lads! there's none

o' ye know what wark is." Mr. Gooch says he was proud

of the dexterity in handling a spade which he had thus acquired, and

that he has frequently seen him take the shovel from a labourer in

some railway cutting, and show him how to use it more deftly in

filling wagons of earth, gravel, or sand. Sir Joshua Walmsley

has also informed us that, when examining the works of the Orleans

and Tours Railway, Stephenson, seeing a large number of excavators

filling and wheeling sand in a cutting, at a great waste of time and

labour, went up to the men and said he would show them how to fill

their barrows in half the time. He showed them the proper

position in which to stand so as to exercise the greatest amount of

power with the least expenditure of strength; and he filled the

barrow with comparative ease again and again in their presence, to

the great delight of the workmen. When passing through his own

workshops he would point out to his men how to save labour and get

through their work skilfully and with ease. His energy

imparted itself to others, quickening and influencing them as strong

characters always do, flowing down into theirs, and bringing out

their best powers.

His deportment to the workmen employed under him was

familiar, yet firm and consistent. As he respected their

manhood, so they respected his masterhood. Although he

comported himself toward his men as if they occupied very much the

same level with himself, he yet possessed that peculiar capacity for

governing which enabled him always to preserve among them the

strictest discipline, and to secure their cheerful and hearty

services. Mr. Ingham, M.P. for South Shields, on going over

the workshops at Newcastle, was particularly struck with this

quality of the master in his bearing toward his men. "There

was nothing," said he, "of undue familiarity in their intercourse,

but they spoke to each other as man to man; and nothing seemed to

please the master more than to point out illustrations of the

ingenuity of his artisans. He took up a rivet, and expatiated

on the skill with which it had been fashioned by the workman's

hand—its perfectness and truth. He was always proud of his

workmen and his pupils; and, while indifferent and careless as to

what might be said of himself, he fired up in a moment if

disparagement were thrown upon any one whom he had taught or

trained."

In manner, George Stephenson was simple, modest, and

unassuming, but always manly. He was frank and social in

spirit. When a humble workman, he had carefully preserved his

sense of self-respect. His companions looked up to him, and

his example was worth much more to many of them than books or

schools. His devoted love of knowledge made his poverty

respectable, and adorned his humble calling. When he rose to a

more elevated station, and associated with men of the highest

position and influence in Britain, he took his place among them with

perfect self-possession. They wondered at the quiet ease and

simple dignity of his deportment; and men in the best ranks of life

have said of him that "he was one of Nature's gentlemen."

Probably no military chiefs were ever more beloved by their

soldiers than were both father and son by the army of men who, under

their guidance, worked at labours of profit, made labours of love by

their earnest will and purpose. True leaders of men and lords

of industry, they were always ready to recognize and encourage

talent in those who worked for and with them. Thus it was

pleasant, at the openings of the Stephenson lines, to hear the chief

engineers attributing the successful completion of the works to

their assistants; while the assistants, on the other hand, ascribed

the principal glory to their chiefs.

George Stephenson, though a thrifty and frugal man, was

essentially unsordid. His rugged path in early life made him

careful of his resources. He never saved to hoard, but saved

for a purpose, such as the maintenance of his parents or the

education of his son. In his later years he became a

prosperous and even a wealthy man; but riches never closed his

heart, nor stole away the elasticity of his soul. He enjoyed

life cheerfully, because hopefully. When he entered upon a

commercial enterprise, whether for others or for himself, he looked

carefully at the ways and means. Unless they would "pay," he

held back. "He would have nothing to do," he declared, "with

stock-jobbing speculations." His refusal to sell his name to

the schemes of the railway mania—his survey of the Spanish lines

without remuneration—his offer to postpone his claim for payment

from a poor company until their affairs became more prosperous, are

instances of the unsordid spirit in which he acted.

Another marked feature in Mr. Stephenson's character was his

patience. Notwithstanding the strength of his convictions as

to the great uses to which the locomotive might be applied, he

waited long and patiently for the opportunity of bringing it into

notice; and for years after he had completed an efficient engine, he

went on quietly devoting himself to the ordinary work of the

colliery. He made no noise nor stir about his locomotive, but

allowed another to take credit for the experiments on velocity and

friction which he had made with it upon the Killingworth railroad.

By patient industry and laborious contrivance he was enabled, with

the powerful help of his son, almost to do for the locomotive what

James Watt had done for the condensing engine. He found it

clumsy and inefficient, and he made it powerful, efficient, and

useful. Both have been described as the improvers of their

respective engines; but, as to all that is admirable in their

structure or vast in their utility, they are rather entitled to be

described as their inventors. They have both tended to

increase indefinitely the mass of human comforts and enjoyments, and

to render them cheap and accessible to all. But Stephenson's

invention, by the influence which it is daily exercising upon the

civilization of the world, is even more remarkable than that of

Watt, and is calculated to have still more important consequences.

In this respect it is to be regarded as the grandest application of

steam-power that has yet been discovered.

George Stephenson's close and accurate observation provided

him with a fullness of information on many subjects which often

appeared surprising to those who had devoted to them a special

study. On one occasion the accuracy of his knowledge of birds

came out in a curious way at a convivial meeting of railway men in

London. The engineers and railway directors present knew each

other as railway men and nothing more. The talk had been all

of railways and railway politics. Stephenson was a great

talker on those subjects, and was generally allowed, from the

interest of his conversation and the extent of his experience, to

take the lead. At length one of the party broke in with,

"Come, now, Stephenson, we have had nothing but railways! can not we

have a change, and try if we can talk a little about something

else?" "Well," said Stephenson, "I'll give you a wide range of

subjects; what shall it be about?" "Say birds' nests!"

rejoined the other, who prided himself on his special knowledge of

the subject. "Then birds' nests be it." A long and

animated conversation ensued: the bird-nesting of his boyhood—the

blackbird's nest which his father had held him up in his arms to

look at when a child at Wylam—the hedges in which he had found the

thrush's and the linnet's nests—the mossy bank where the robin

built—the cleft in the branch of the young tree where the chaffinch

had reared its dwelling—all rose up clear in his mind's eye, and led

him back to the scenes of his boyhood at Callerton and Dewley Burn.

The colour and number of the birds' eggs—the period of their

incubation—the materials employed by them for the walls and lining

of their nests, were described by him so vividly, and illustrated by

such graphic anecdotes, that one of the party remarked that, if

George Stephenson had not been the greatest engineer of his day, he

might have been one of the greatest naturalists.

His powers of conversation were very great. He was so

thoughtful, original, and suggestive. There was scarcely a

department of science on which he had not formed some novel and

sometimes daring theory. Thus Mr. Gooch, his pupil, who lived

with him when at Liverpool, informs us that when sitting over the

fire, he would frequently broach his favourite theory of the sun's

light and heat being the original source of the light and heat given

forth by the burning coal. "It fed the plants of which that

coal is made," he would say, "and has been bottled up in the earth

ever since, to be given out again now for the use of man." His

son Robert once said of him, "My father flashed his bull's eye full

upon a subject, and brought it out in its most vivid light in an

instant: his strong common sense and his varied experience,

operating on a thoughtful mind, were his most powerful

illuminators."

The Bishop of Oxford related the following anecdote of him at

a recent public meeting in London: "He heard the other day of an

answer given by the great self-taught man, Stephenson, when he was

speaking with something of distrust of what were called competitive

examinations. Stephenson said, 'I distrust them for this

reason—they will lead, it seems to me, to an unlimited power of

cram;' and he added, 'Let me give you one piece of advice—never to

judge of your goose by its stuffing!'"

George Stephenson had once a conversation with a watchmaker,

whom he astonished by the extent and minuteness of his knowledge as

to the parts of a watch. The watchmaker knew him to be an

eminent engineer, and asked how he had acquired so extensive a

knowledge of a branch of business so much out of his sphere.

"It is very easily to be explained," said Stephenson; "I worked long

at watch-cleaning myself, and when I was at a loss, I was never

ashamed to ask for information."

His hand was open to his former fellow-workmen whom old age

had left in poverty. To poor Robert Gray, of Newburn, who

acted as his brideman on his marriage to Fanny Henderson, he left a

pension for life. He would slip a five-pound note into the

hand of a poor man or a widow in such a way as not to offend their

delicacy, but to make them feel as if the obligation were all on his

side. When Farmer Paterson, who married a sister of George's

first wife, Fanny Henderson, died and left a large young family

fatherless, poverty stared them in the face. "But ye ken,"

said our informant, "George struck in fayther for them."

And perhaps the providential character of the act could not have

been more graphically expressed than in these simple words.

On his visit to Newcastle, he would frequently meet the

friends of his early days, occupying very nearly the same station in

life, while he had meanwhile risen to almost world-wide fame; but he

was not less hearty in his greeting of them than if their relative

position had remained the same. Thus, one day, after shaking

hands with Mr. Brandling on alighting from his carriage, he

proceeded to shake hands with his coachman, Anthony Wigham, a still

older friend, though he only sat on the box.

Robert Stephenson inherited his father's kindly spirit and

benevolent disposition. We have already stated that he was

often called in as an umpire to mediate between conflicting parties,

more particularly between contractors and engineers. On one

occasion Brunel complained to him that he could not get on with his

contractors, who were never satisfied, and were always quarrelling

with him. "You hold them too tightly to the letter of your

agreement," said Stephenson; "treat them fairly and liberally."

"But they try to take advantage of me at all points," rejoined

Brunel. "Perhaps you suspect them too much?" said Stephenson.

"I suspect all men to be rogues," said the other, "till I find them

to be honest." "For my part," said Stephenson, "I take all men

to be honest till I find them to be rogues." "Ah then, I fear

we shall never agree," concluded Brunel.

Robert almost worshiped his father's memory, and was ever

ready to attribute to him the chief merit of his own achievements as

an engineer. "It was his thorough training," we once heard him

say, "his example, and his character, which made me the man I am."

On a more public occasion he said, "It is my great pride to remember

that, whatever may have been done, and however extensive may have

been my own connection with railway development, all I know and all

I have done is primarily due to the parent whose memory I cherish

and revere." [p.493]

To Mr. Lough, the sculptor, he said he had never had but two

loves—one for his father, the other for his wife.

Like his father, he was eminently practical, and yet always

open to the influence and guidance of correct theory. His main

consideration in laying out his lines of railway was what would best

answer the intended purpose, or, to use his own words, to secure the

maximum of result with the minimum of means. He was

pre-eminently a safe man, because cautious, tentative, and

experimental; following closely the lines of conduct trodden by his

father, and often quoting his maxims.

In society Robert Stephenson was simple, unobtrusive, and

modest, but charming and even fascinating in an eminent degree.

Sir John Lawrence has said of him that he was, of all others, the

man he most delighted to meet in England—he was so manly yet gentle,

and withal so great. While admired and beloved by men of such

calibre, he was equally a favourite with women and children.

He put himself upon the level of all, and charmed them no less by

his inexpressible kindliness of manner than by his simple yet

impressive conversation.

His great wealth enabled him to perform many generous acts in

a right noble and yet modest manner, not letting his right hand know

what his left hand did. Of the numerous kindly acts of his

which have been made public, we may mention the graceful manner in

which he repaid the obligations which both himself and his father

owed to the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Institute when

working together as fellow experimenters many years before in their

humble cottage at Killingworth. The Institute was struggling

under a debt of £6200, which impaired its usefulness as an

educational agency. Mr. Stephenson offered to pay one half the

sum provided the local supporters of the Institute would raise the

remainder, and conditional also on the annual subscription being

reduced from two guineas to one, in order that the usefulness of the

institution might be extended. His generous offer was accepted

and the debt extinguished.

Both father and son were offered knighthood, and both

declined it. During the summer of 1847, George Stephenson was

invited to offer himself as a candidate for the representation of

South Shields in Parliament. But his politics were at best of

a very undefined sort. Indeed, his life had been so much

occupied with subjects of a practical character that he had scarcely

troubled himself to form any decided opinion on the party political

topics of the day, and to stand the cross-fire of the electors on

the hustings might possibly have proved an even more distressing

ordeal than the cross-questioning of the barristers in the

Committees of the House of Commons. "Politics," he used to

say, "are all matters of theory—there is no stability in them; they

shift about like the sands of the sea; and I should feel quite out

of my element among them." He had, accordingly, the good sense

respectfully to decline the honour of contesting the representation

of South Shields.

We have, however, been informed by Sir Joseph Paxton that,

although George Stephenson held no strong opinions on political

questions generally, there was one question on which he entertained

a decided conviction, and that was the question of Free Trade.

The words used by him on one occasion to Sir Joseph were very

strong. "England," said he, "is, and must be, a shopkeeper;

and our docks and harbours are only so many wholesale shops, the

doors of which should always be kept wide open." It is curious

that his son should have taken precisely the opposite view of this

question, and acted throughout with the most rigid party among the

Protectionists, supporting the Navigation Laws and opposing Free

Trade, even to the extent of going into the lobby with Colonel

Sibthorp, Mr. Spooner, and the fifty-three "cannon-balls", on the

26th of November, 1852. Robert Stephenson to the last spoke in

strong terms as to the "betrayal of the Protectionist party" by

their chosen leader, and he went so far as to say that he "could

never forgive Peel."

But Robert Stephenson will be judged in after times by his

achievements as an engineer rather than by his acts as a politician;

and, happily, these last were far outweighed in value by the immense

practical services which he rendered to trade, commerce, and

civilization, through the facilities which the railways constructed

by him afforded for free intercommunication on between men in all

parts of the world. Speaking in the midst of his friends at

Newcastle in 1850, he observed:

"It seems to me but as yesterday

that I was engaged as an assistant in laying out the Stockton and

Darlington Railway. Since then, the Liverpool and Manchester,

and a hundred other great works have sprung into existence. As

I look back upon these stupendous undertakings, accomplished in so

short a time, it seems as though we had realized in our generation

the fabled powers of the magician's wand. Hills have been cut

down and valleys filled up; and when these simple expedients have

not sufficed, high and magnificent viaducts have been raised, and,

if mountains stood in the way, tunnels of unexampled magnitude have

pierced them through, bearing their triumphant attestation to the

indomitable energy of the nation, and the unrivalled skill of our

artisans."

As respects the immense advantages of railways to mankind

there can not be two opinions. They exhibit, probably, the

grandest organization of capital and labour that the world has yet

seen. Although they have unhappily occasioned great loss to

many, the loss has been that of individuals, while, as a national

system, the gain has already been enormous. As tending to

multiply and spread abroad the conveniences of life, opening up new

fields of industry, bringing nations nearer to each other, and thus

promoting the great ends of civilization, the founding of the

railway system by George Stephenson and his son must be regarded as

one of the most important events, if not the very greatest, in the

first half of this nineteenth century.

|

――――♦――――

|