|

[Previous Page]

CHAPTER VII.

GEORGE STEPHENSON'S FARTHER IMPROVEMENT IN THE LOCOMOTIVE—THE HETTON

RAILWAY—ROBERT STEPHENSON AS VIEWER'S APPRENTICE AND STUDENT.

STEPHENSON'S

experiments on fire-damp, and his labours in connection with the

invention of the safety-lamp, occupied but a small portion of his

time, which was necessarily devoted, for the most part, to the

ordinary business of the colliery. From the day of his

appointment as engine-wright, one of the subjects which particularly

occupied his attention was the best practical method of winning and

raising the coal. Nicholas Wood has said of him that he was

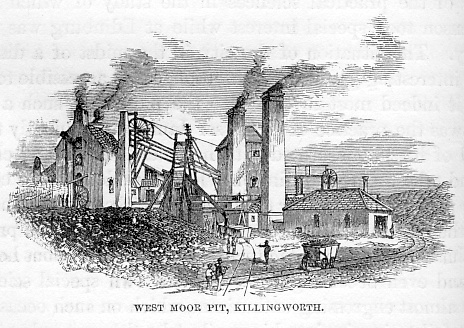

one of the first to introduce steam machinery underground with that

object. Indeed, the Killingworth mines came to be regarded as

the models of the district; and when Mr. Robert Bald, the celebrated

Scotch mining engineer, was requested by Dr. (afterward Sir David)

Brewster to prepare the article "Mine" for the "Edinburgh

Encyclopaedia,'' he proceeded to Killingworth principally for the

purpose of examining Stephenson's underground machinery. Mr.

Bald has favoured us with an account of his visit made with that

object in 1818, and he states that he was much struck with the

novelty, as well as the remarkable efficiency of Stephenson's

arrangements, especially in regard to what is called the underdip

working.

"I found," he says,

"that a mine had been commenced near the main

pit-bottom, and carried forward down the dip or slope of the coal,

the rate of dip being about one in twelve; and the coals were drawn

from the dip to the pit-bottom by the steam machinery in a very

rapid manner. The water which oozed from the upper winning was

disposed of at the pit-bottom in a barrel or trunk, and was drawn up

by the power of the engine which worked the other machinery.

The dip at the time of my visit was nearly a mile in length, but has

since been greatly extended. As I was considerably tired by my

wanderings in the galleries, when I arrived at the forehead of the

dip, Mr. Stephenson said to me, 'You may very speedily be carried up

to the rise by laying yourself flat upon the coal-baskets,' which

were laden and ready to be taken up the incline. This I at

once did, and was straightway wafted on the wings of fire to the

bottom of the pit, from whence I was borne swiftly up to the light

by the steam machinery on the pit-head."

The whole of the working arrangements seemed to Mr. Bald to

be conducted in the most skilful and efficient manner, reflecting

the highest credit on the colliery engineer.

Besides attending to the underground arrangements, the

improved transit of the coals above ground from the pit-head to the

shipping-place demanded an increasing share of Stephenson's

attention. Every day's experience convinced him that the

locomotive constructed by him after his patent of the year 1815 was

far from perfect, though he continued to entertain confident hopes

of its complete eventual success. He even went so far as to

say that the locomotive would yet supersede every other

traction-power for drawing heavy loads. It is true, many

persons continued to regard his travelling engine as little better

than a dangerous curiosity; and some, shaking their heads, predicted

for it "a terrible blow-up some day." Nevertheless, it was

daily performing its work with regularity, dragging the coal-wagons

between the colliery and the staiths, and saving the labour of many

men and horses.

There was not, however, so marked a saving in the expense of

haulage as to induce the colliery masters to adopt locomotive power

generally as a substitute for horses. How it could be

improved, and rendered more efficient as well as economical, was

constantly present to Stephenson's mind. He was fully

conscious of the imperfections both in the road and the engine, and

gave himself no rest until he had brought the efficiency of both up

to a higher point. Thus he worked his way inch by inch, slowly

but surely, and every step gained was made good as a basis for

farther improvements.

At an early period of his labours, or about the time when he

had completed his second locomotive, he began to direct his

particular attention to the state of the road, perceiving that the

extended use of the locomotive must necessarily depend in a great

measure upon the perfection, solidity, continuity, and smoothness of

the way along which the engine travelled. Even at that early

period he was in the habit of regarding the road and the locomotive

as one machine, speaking of the Rail and the Wheel as "Man and

Wife."

All railways were at that time laid in a careless and loose

manner, and great inequalities of level were allowed to occur

without much attention being paid to repairs. The consequence

was a great loss of power, as well as much wear and tear of the

machinery, by the frequent jolts and blows of the wheels against the

rails. Stephenson's first object, therefore, was to remove the

inequalities produced by the imperfect junction between rail and

rail.

At that time (1816) the rails were made of cast iron, each

rail being about three feet long; and sufficient care was not taken

to maintain the points of junction on the same level. The

chain, or cast-iron pedestals into which the rails were inserted,

were flat at the bottom, so that whenever any disturbance took place

in the stone blocks or sleepers supporting them, the flat base of

the chair upon which the rails rested being tilted by unequal

subsidence, the end of one rail became depressed, while that of the

other was elevated. Hence constant jolts and shocks, the

reaction of which very often caused the fracture of the rails, and

occasionally threw the engine off the road.

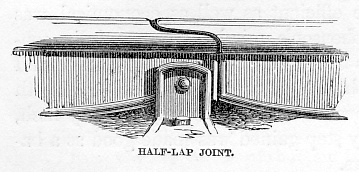

To remedy this imperfection, Mr. Stephenson devised a new

chair, with an entirely new mode of fixing the rails therein.

Instead of adopting the butt joint which had hitherto been used in

all cast-iron rails, he adopted the half-lap joint, by which means

the rails extended a certain distance over each other at the ends

like a scarf-joint. These ends, instead of resting on the flat

chair, were made to rest upon the apex of a curve forming the bottom

of the chair. The supports were also extended from three feet

to three feet nine inches or four feet apart. These rails were

accordingly substituted for the old cast iron plates on the

Killingworth Colliery Railway, and they were found to be a very

great improvement on the previous system, adding both to the

efficiency of the horse-power (still used on the railway) and to the

smooth action of the locomotive engine, but more particularly

increasing the efficiency of the latter.

This improved form of the rail and chair was embodied in a

patent taken out in the joint names of Mr. Losh, of Newcastle, iron

founder, and of Mr. Stephenson, bearing date the 30th of September,

1816. Mr. Losh being a wealthy, enterprising

iron-manufacturer, and having confidence in George Stephenson and

his improvements, found the money for the purpose of taking out the

patent, which in those days was a very costly as well as troublesome

affair. At the same time, Mr. Losh guaranteed Stephenson a

salary of £100 per annum, with a share in the profits arising from

his inventions, conditional on his attending at the Walker

Iron-works two days a week—an arrangement to which the owners of the

Killingworth Colliery cheerfully gave their sanction.

The specification of 1816 included various important

improvements in the locomotive itself. The wheels of the

engine were improved, being altered from cast to malleable iron, in

whole or in part, by which they were made lighter as well as more

durable and safe. The patent also included the ingenious and

original contrivance by which the steam generated in the boiler was

made to serve as a substitute for springs—an expedient already

explained in a preceding chapter.

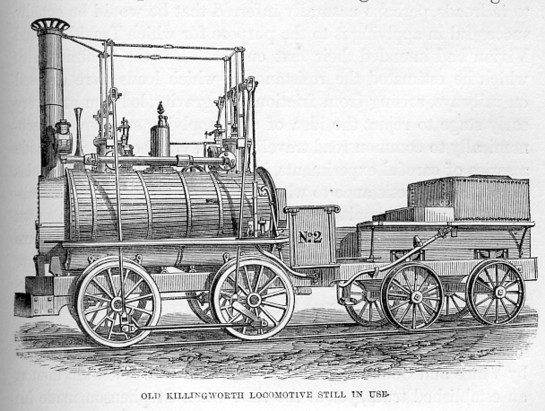

The result of the actual working of the new locomotive on the

improved road amply justified the promises held forth in the

specification. The traffic was conducted with greater

regularity and economy, and the superiority of the engine, as

compared with horse traction, became still more marked. And it

is a fact worthy of notice, that the identical engines constructed

by Stephenson in 1816 are to this day in regular useful work upon

the Killingworth Railway, conveying heavy coal-trains at the speed

of between five and six miles an hour, probably as economically as

any of the more perfect locomotives now in use.

George Stephenson's endeavours having been attended with such

marked success in the adaptation of locomotive power to railways,

his attention was called by many of his friends, about the year

1818, to the application of steam to travelling on common roads.

It was from this point, indeed, that the locomotive had started,

Trevithick's first engine having been constructed with this special

object. Stephenson's friends having observed how far behind he

had left the original projector of the locomotive in its application

to railroads, perhaps naturally inferred that he would be equally

successful in applying it to the purpose for which Trevithick and

Vivian had intended their first engine. But the accuracy with

which he estimated the resistance to which loads were exposed on

railways, arising from friction and gravity, led him at a very early

stage to reject the idea of ever applying steam-power economically

to common road travelling. In October, 1818, he made a series

of careful experiments, in conjunction with Mr. Nicholas Wood, on

the resistance to which carriages were exposed on railways, testing

the results by means of a dynamometer of his own contrivance.

The series of practical observations made by means of this

instrument were interesting, as the first systematic attempt to

determine the precise amount of resistance to carriages moving along

railways. It was then for the first time ascertained by

experiment that the friction was a constant quantity at all

velocities. Although this theory had long before been

developed by Vince and Coulomb, and was well known to scientific men

as an established truth, yet, at the time when Stephenson made his

experiments, the deductions of philosophers on the subject were

neither believed in nor acted upon by practical engineers. To

quote again from the MS. account supplied to the author by Robert

Stephenson for the purposes of his father's "Life:"

"It was maintained by many that

the results of the experiments led to the greatest possible

mechanical absurdities. For instance, it was maintained that,

if friction were constant at all velocities upon a level railway,

when once a power was applied to a carriage which exceeded the

friction of that carriage by the smallest possible amount, that same

small excess of power would be able to convey the carriage along a

level railway at all conceivable velocities. When this

position was put by those who opposed the conclusions at which my

father had arrived, he felt great hesitation in maintaining his own

views; for it appeared to him at first sight really to be—as it was

put by his opponents—an absurdity. Frequent repetition,

however, of the experiments to which I have alluded, left no doubt

upon his mind that his conclusion that friction was uniform at all

velocities was a fact which must be received as positively

established; and he soon afterward boldly maintained that that which

was an apparent absurdity was, instead, a necessary consequence.

I well remember the ridicule that was thrown upon this view by many

of those persons with whom he was associated at the time.

Nevertheless, it is undoubted, that, could you practically be always

applying a power in excess of the resistance, a constant increase of

velocity would of necessity follow without any limit. This is

so obvious to most professional men of the present day, and is now

so axiomatic, that I only allude to the discussion which took place

when these experiments of my father were announced for the purpose

of showing how small was the amount of science at that time blended

with engineering practice. A few years afterward, an excellent

pamphlet was published by Mr. Silvester on this question; he took up

the whole subject, and demonstrated in a very simple and beautiful

manner the correctness of all the views at which my father had

arrived by his course of experiments.

"The other resistances to which carriages were exposed were

also investigated experimentally by my father. He perceived

that these resistances were mainly three—the first being upon the

axles of the carriage; the second, which may be called the rolling

resistance, being between the circumference of the wheel and the

surface of the rail; and the third being the resistance of gravity.

"The amount of friction and gravity he accurately

ascertained; but the rolling resistance was a matter of greater

difficulty, for it was subject to great variation. He,

however, satisfied himself that it was so great, when the surface

presented to the wheel was of a rough character, that the idea of

working steam-carriages economically on common roads was out of the

question. Even so early as the period alluded to he brought

his theoretical calculations to a practical test; he scattered sand

upon the rails when an engine was running, and found that a small

quantity was quite sufficient to retard and even stop the most

powerful locomotive engine that he had at that time made. And

he never failed to urge this conclusive experiment upon the

attention of those who were wasting their money and time upon the

vain attempt to apply steam to common roads.

"The following were the principal arguments which influenced

his mind to work out the use of the locomotive in a directly

opposite course to that pursued by a number of ingenious inventors,

who, between 1820 and 1836, were engaged in attempting to apply

steam-power to turnpike roads. Having ascertained that

resistance might be taken as represented by 10 lbs. to a ton weight

on a level railway, it became obvious to him that so small a rise as

1 in 100 would diminish the useful effort of a locomotive by upward

of fifty per cent. This fact called my father's attention to

the question of gradients in future locomotive lines. He then

became convinced of the vital importance, in an economical point of

view, of reducing the country through which a railway was intended

to pass to as near a level as possible. This originated in his

mind the distinctive character of railway works as

contra-distinguished from all other roads; for in railroads he early

contended that large sums would be wisely expended in perforating

barriers of hills with long tunnels, and in raising low ground with

the excess cut down from the adjacent high ground. In

proportion as these views fixed themselves upon his mind, and were

corroborated by his daily experience, he became more and more

convinced of the hopelessness of applying steam locomotion to common

roads; for every argument in favour of a level railway was an

argument against the rough and hilly course of a common road.

He never ceased to urge upon the patrons of road steam-carriages

that if, by any amount of ingenuity, an engine could be made which

could by possibility traverse a turnpike road at a speed at least

equal to that obtainable by horse-power, and at a less cost, such an

engine, if applied to the more perfect surface of a railway, would

have its efficiency enormously enhanced. For instance, he

calculated that if an engine had been constructed, and had been

found to travel uniformly between London and Birmingham at an

average speed of 10 miles an hour—conveying, say, 20 or 30

passengers at a cost of 1s. per mile, it was clear that the

same engine, if applied to a railway, instead of conveying 20 or 30

people, would have conveyed 200 or 300 people, and instead of a

speed of 10 or 12 miles an hour, a speed of at least 30 to 40 miles

an hour would have been obtained."

At this day it is difficult to understand how the sagacious

and strong- common-sense views of Stephenson on this subject failed

to force themselves sooner upon the minds of those who were

persisting in their vain though ingenious attempts to apply

locomotive power to ordinary roads. For a long time they

continued to hold with obstinate perseverance to the belief that for

such purposes a soft road was better than a hard one—a road easily

crushed better than one incapable of being crushed; and they held to

this after it had been demonstrated in all parts of the mining

districts that iron tram-ways were better than paved roads.

But the fallacy that iron was incapable of adhesion upon iron

continued to prevail, and the projectors of steam-travelling on

common roads only shared in the common belief. They still

considered that roughness of surface was essential to produce

"bite,'' especially in surmounting acclivities; the truth being that

they confounded roughness of surface with tenacity of surface and

contact of parts, not perceiving that a yielding surface which would

adapt itself to the tread of the wheel could never become an

unyielding surface to form a fulcrum for its progression.

Although Stephenson's locomotive engines were in daily use

for many years on the Killingworth Railway, they excited

comparatively little interest. They were no longer

experimental, but had become an established tractive power.

The experience of years had proved that they worked more steadily,

drew heavier loads, and were, on the whole, considerably more

economical than horses. Nevertheless, eight years passed

before another locomotive railway was constructed and opened for the

purposes of coal or other traffic.

It is difficult to account for this early indifference on the

part of the public to the merits of the greatest mechanical

invention of the age. Steam-carriages were exciting much

interest, and numerous and repeated experiments were made with them.

The improvements effected by McAdam in the mode of constructing

turnpike roads were the subject of frequent discussions in the

Legislature, on the grants of public money being proposed, which

were from time to time made to him. Yet here at Killingworth,

without the aid of a farthing of government money, a system of road

locomotion had been in existence since 1814, which was destined,

before many years, to revolutionize the internal communications of

England and of the world, but of which the English public and the

English government as yet knew nothing.

But Stephenson had no means of bringing his important

invention prominently under the notice of the public. He

himself knew well its importance, and he already anticipated its

eventual general adoption; but, being an unlettered man, he could

not give utterance to the thoughts which brooded within him on the

subject. Killingworth Colliery lay far from London, the centre

of scientific life in England. It was visited by no savans nor

literary men, who might have succeeded in introducing to notice the

wonderful machine of Stephenson. Even the local chroniclers

seem to have taken no notice of the Killingworth Railway. The

"Puffing Billy" was doing its daily quota of hard work, and had long

ceased to be a curiosity in the neighbourhood. Blenkinsop's

clumsier and less successful engine—which has long since been

disused, while Stephenson's Killingworth engines continue working to

this day—excited far more interest, partly, perhaps, because it was

close to the large town of Leeds, and used to be visited by

strangers as one of the few objects of interest in that place.

Blenkinsop was also an educated man, and was in communication with

some of the most distinguished personages of his day on the subject

of his locomotive, which thus obtained considerable celebrity.

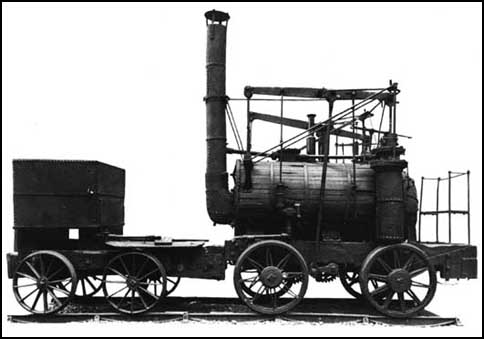

William Hedley's "Puffing Billy", 1814, Wylam

Colliery,

the world's oldest surviving steam locomotive.

The first engine constructed by Stephenson to order, after

the Killingworth model, was made for the Duke of Portland in 1817,

for use upon his tram-road, about ten miles long, extending from

Kilmarnock to Troon, in Ayrshire. It was employed to haul the

coals from the duke's collieries along the line to Troon harbour.

Its use was, however, discontinued in consequence of the frequent

breakages of the cast-iron rails, by which the working of the line

was interrupted, and accordingly horses were again employed as

before. [p.207]

There seemed, indeed, to be so small a prospect of

introducing the locomotive into general use, that Stephenson—perhaps

conscious of the capabilities within him—again recurred to his old

idea of emigrating to the United States. Before entering as

sleeping partner in a small foundry at Forth Banks, Newcastle,

managed by Mr. John Burrell, he had thrown out the suggestion to the

latter that it would be a good speculation for them to emigrate to

North America, and introduce steam-boats on the great inland lakes

there. The first steamers were then plying upon the Tyne

before his eyes, and he saw in them the germ of a great revolution

in navigation. It occurred to him that the great lakes of

North America presented the finest field for trying their wonderful

powers. He was an engineer, and Mr. Burrell was an

iron-founder; and between them, he thought they might strike out a

path to fortune in the mighty West. Fortunately, this idea

remained a mere speculation so far as Stephenson was concerned, and

it was left to others to do what he had dreamed of achieving.

After all his patient waiting, his skill, industry, and perseverance

were at length about to bear fruit.

In 1819, the owners of the Hetton Colliery, in the county of

Durham, determined to have their wagon-way altered to a locomotive

railroad. The result of the working of the Killingworth

Railway had been so satisfactory that they resolved to adopt the

same system. One reason why an experiment so long continued

and so successful as that at Killingworth should have been so slow

in producing results perhaps was, that to lay down a railway and

furnish it with locomotives, or fixed engines where necessary,

required a very large capital, beyond the means of ordinary

coal-owners; while the small amount of interest felt in railways by

the general public, and the supposed impracticability of working

them to a profit, as yet prevented the ordinary capitalists from

venturing their money in the promotion of such undertakings.

The Hetton Coal Company were, however, possessed of adequate means,

and the local reputation of the Killingworth engine-wright pointed

him out as the man best calculated to lay out their line and

superintend their works. They accordingly invited him to act

as the engineer of the proposed railway. Being in the service

of the Killingworth Company, Stephenson felt it necessary to obtain

their permission to enter upon this new work. This was at once

granted. The best feeling existed between him and his

employers, and they regarded it as a compliment that their colliery

engineer should be selected for a work so important as the laying

down of the Hetton Railway, which was to be the longest locomotive

line that had, up to that time, been constructed in the

neighbourhood. Stephenson accepted the appointment, his

brother Robert acting as resident engineer and personally

superintending the execution of the works.

The Hetton Railway extended from the Hetton Colliery,

situated about two miles south of Houghton-le-Spring, to the

ship-places on the banks of the Wear, near Sunderland. Its

length was about eight miles; and in its course it crossed Warden

Law, one of the highest hills in the district. The character

of the country forbade the construction of a flat line, or one of

comparatively easy gradients, except by the expenditure of a much

larger capital than was placed at Stephenson's command. Heavy

works could not be executed; it was therefore necessary to form the

line with but little deviation from the natural conformation of the

district which it traversed, and also to adapt the mechanical

methods employed for its working to the character of the gradients,

which in some places were necessarily heavy.

Although George Stephenson had, with every step made toward

its increased utility, become more and more identified with the

success of the locomotive engine, he did not allow his enthusiasm to

carry him away into costly mistakes. He carefully drew the

line between the cases in which the locomotive could be usefully

employed and those in which stationary engines were calculated to be

more economical. This led him, as in the instance of the

Hetton Railway, to execute lines through and over rough countries,

where gradients within the powers of the locomotive engine of that

day could not be secured, employing in their stead stationary

engines where locomotives were not practicable. In the present

case, this course was adopted by him most successfully. On the

original Hetton line there were five self-acting inclines—the full

wagons drawing the empty ones up—and two inclines worked by fixed

reciprocating engines of sixty-horse power each. The

locomotive travelling engine, or "the iron horse," as the people of

the neighbourhood then styled it, worked the rest of the line.

On the day of the opening of the Hetton Railway, the 18th of

November, 1822, crowds of spectators assembled from all parts to

witness the first operations of this ingenious and powerful

machinery, which was entirely successful. On that day five of

Stephenson's locomotives were at work upon the railway, under the

direction of his brother Robert; and the first shipment of coal was

then made by the Hetton Company at their new staiths on the Wear.

The speed at which the locomotives travelled was about four miles an

hour, and each engine dragged after it a train of seventeen wagons

weighing about sixty-four tons.

While thus advancing step by step—attending to the business

of the Killingworth Colliery, and laying out railways in the

neighbourhood—he was carefully watching over the education of his

son. We have already seen that Robert was sent to school at

Newcastle, where he remained about four years. While Robert

was at school, his father, as usual, made his son's education

instrumental to his own. He entered him a member of the

Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Institute, the subscription to

which was three guineas a year. Robert spent much of his

leisure hours there, reading and studying; and when he went home in

the afternoons, he was accustomed to carry home with him a volume of

the "Repertory of Arts and Sciences," or of some work on practical

science, which furnished the subject of interesting reading and

discussion in the evening hours. Both father and son were

always ready to acknowledge the great advantages they had derived

from the use of so excellent a library of books; and, toward the

close of his life, the latter, in recognition of his debt of

gratitude to the institution, contributed a large sum for the

purpose of clearing off the debt, but conditional on the annual

subscription being reduced to a guinea, in order that the usefulness

of the Institute might be extended.

Robert left school in the summer of 1819, and was put

apprentice to Mr. Nicholas Wood, the head viewer at Killingworth, to

learn the business of the colliery. He served in that capacity

for about three years, during which time he became familiar with

most departments of underground work. His occupation was not

unattended with peril, as the following incident will show.

Though the use of the Geordy lamp had become general in the

Killingworth pits, and the workmen were bound, under a penalty of

half a crown, not to use a naked candle, it was difficult to enforce

the rule, and even the masters themselves occasionally broke it.

One day Nicholas Wood, the head viewer, Moodie, the under viewer,

and Robert Stephenson, were proceeding along one of the galleries.

Wood with a naked candle in his hand, and Robert following him with

a lamp. They came to a place where a fall of stones from the

roof had taken place, on which Wood, who was first, proceeded to

clamber over the stones, holding high the naked candle. He had

nearly reached the summit of the heap, when the fire-damp, which had

accumulated in the hollow of the roof, exploded, and instantly the

whole party were blown down, and the lights extinguished. They

were a mile from the shaft, and quite in the dark. There was a

rush of the work-people from all quarters toward the shaft, for it

was feared that the fire might extend to more dangerous parts of the

pit, where, if the gas had exploded, every soul in the mine must

inevitably have perished. Robert Stephenson and Moodie, on the

first impulse, ran back at full speed along the dark gallery leading

to the shaft, coming into collision, on their way, with the hind

quarters of a horse stunned by the explosion. When they had

gone half way, Moodie halted, and bethought him of Nicholas Wood.

"Stop, laddie!" said he to Robert, "stop; we maun gang back and seek

the maister." So they retraced their steps. Happily, no

farther explosion took place. They found the master lying on

the heap of stones, stunned and bruised, with his hands severely

burnt. They led him to the bottom of the shaft; and he

afterward took care not to venture into the dangerous parts of the

mine without the protection of a Geordy lamp.

The time that Robert spent at Killingworth as viewer's

apprentice was of advantage both to his father and himself.

The evenings were generally devoted to reading and study, the two

from this time working together as friends and co-labourers.

One who used to drop in at the cottage of an evening well remembers

the animated and eager discussions which on some occasions took

place, more especially with reference to the growing powers of the

locomotive engine. The son was even more enthusiastic than his

father on the subject. Robert would suggest numerous

alterations and improvements in detail. His father, on the

contrary, would offer every possible objection, defending the

existing arrangements—proud, nevertheless, of his son's suggestions,

and often warmed and excited by his brilliant anticipations of the

ultimate triumph of the locomotive.

These discussions probably had considerable influence in

inducing Stephenson to take the next important step in the education

of his son. Although Robert, who was only nineteen years of

age, was doing well, and was certain, at the expiration of his

apprenticeship, to rise to a higher position, his father was not

satisfied with the amount of instruction which he had as yet given

him. Remembering the disadvantages under which he had himself

laboured through his ignorance of practical chemistry during his

investigations connected with the safety-lamp, more especially with

reference to the properties of gas, as well as in the course of his

experiments with the object of improving the locomotive engine, he

determined to furnish his son with a better scientific culture than

he had yet attained. He also believed that a proper training

in technical science was indispensable to success in the higher

walks of the engineer's profession, and he determined to give Robert

the education, in a certain degree, which he so much desired for

himself. He would thus, he knew, secure an able co-worker in

the elaboration of the great ideas now looming before him, and with

their united practical and scientific knowledge he probably felt

that they would be equal to any enterprise.

He accordingly took Robert from his labours as under viewer

in the West Moor Pit, and in October, 1822, sent him for a short

coarse of instruction to the Edinburgh University. Robert was

furnished with letters of introduction to several men of literary

eminence in Edinburgh, his father's reputation in connection with

the safety-lamp being of service to him in this respect. He

lodged in Drummond Street, in the immediate vicinity of the college,

and attended the Chemical Lectures of Dr. Hope, the Natural

Philosophy Lectures of Sir John Leslie, and the Natural History

Class of Professor Jameson. He also devoted several evenings

in each week to the study of practical Chemistry under Dr. John

Murray, himself one of the numerous designers of a safety-lamp.

He took careful notes of the lectures, which he copied out at night

before he went to bed, so that, when he returned to Killingworth, he

might read them over to his father. He afterward had the notes

bound up and placed in his library.

Long years after, when conversing with Thomas Harrison, C.E,

at his house in Gloucester Square, he rose from his seat and took

down a volume from the shelves. Mr. Harrison observed that the

book was in MS., neatly written out. "What have we here?" he

asked. The answer was, "When I went to college, I knew the

difficulty my father had in collecting the funds to send me there.

Before going I studied short-hand; while at Edinburgh I took down

verbatim every lecture; and in the evenings, before I went to bed, I

transcribed those lectures word for word. You see the result

in that range of books." From this it will be observed that

the maxim of "Like father, like son," was one that strictly applied

to the Stephensons.

Robert was not without the pleasure of social intercourse

either during his stay at Edinburgh. Among the letters of

introduction which he took with him was one to Robert Bald, the

mining engineer, which proved of much service to him. "I

remember Mr. Bald very well," he said on one occasion, when

recounting his reminiscences of his Edinburgh college life.

"He introduced me to Dr. Hope, Dr. Murray, and several of the

distinguished men of the North. Bald was the Buddle of

Scotland. He knew my father from having visited the pits at

Killingworth, with the object of describing the system of working

them in his article intended for the 'Edinburgh Encyclopaedia.'

A strange adventure befell that article before it appeared in print.

Bald was living at Alloa when he wrote it, and when finished he sent

it to Edinburgh by the hands of young Maxton, his nephew, whom he

enjoined to take special care of it, and deliver it safely into the

hands of the editor. The young man took passage for New Haven

by one of the little steamers which then plied on the Forth; but on

the voyage down the Frith she struck upon a rock nearly opposite

Queen's Ferry, and soon sank. When the accident happened,

Maxton's whole concern was about his uncle's article. He durst

not return to Alloa if he lost it, and he must not go on to

Edinburgh without it. So he desperately clung to the chimney

chains with the paper parcel under his arm, while most of the other

passengers were washed away and drowned. And there he

continued to cling until rescued by some boatmen, parcel and all,

after which he made his way to Edinburgh, and the article duly

appeared."

Returning to the subject of his life in Edinburgh, Robert

continued: "Besides taking me with him to the meetings of the Royal

and other societies, Mr. Bald introduced me to a very agreeable

family, relatives of his own, at whose house I spent many pleasant

evenings. It was there I met Jeannie M――.

She was a bonnie lass, and I, being young and susceptible,

fairly fell in love with her. But, like most very early

attachments, mine proved evanescent. Years passed, and I had

all but forgotten Jeannie, when one day I received a letter from

her, from which it appeared that she was in great distress through

the ruin of her relatives. I sent her a sum of money, and

continued to do so for several years; but the last remittance not

being acknowledged, I directed my friend Sanderson to make

inquiries. I afterward found that the money had reached her at

Portobello just as she was dying, and so, poor thing, she had been

unable to acknowledge it."

One of the practical sciences in the study of which Robert

Stephenson took special interest while at Edinburgh was that of

geology. The situation of the city, in the midst of a district

of highly interesting geological formation, easily accessible to

pedestrians, is indeed most favourable to the pursuit of such a

study; and it was the practice of Professor Jameson frequently to

head a band of his pupils, armed with hammers, chisels, and

clinometers, and take them with him on a long ramble into the

country, for the purpose of teaching them habits of observation, and

reading to them from the open book of Nature itself. The

professor was habitually grave and taciturn, but on such occasions

he would relax and even become genial. For his own special

science he had an almost engrossing enthusiasm, which on such

occasions he did not fail to inspire into his pupils, who thus not

only got their knowledge in the pleasantest possible way, but also

fresh air and exercise in the midst of glorious scenery and in

joyous company.

At the close of this session, the professor took with him a

select body of his pupils on an excursion along the Great Glen of

the Highlands, in the line of the Caledonian Canal, and Robert

formed one of the party. They passed under the shadow of Ben

Nevis, examined the famous old sea-margins known as the "parallel

roads of Glen Roy," and extended their journey as far as Inverness,

the professor teaching the young men, as they travelled, how to

observe in a mountain country. Not long before his death,

Robert Stephenson spoke in glowing terms of the great pleasure and

benefit which he had derived from that interesting excursion.

"I have travelled far, and enjoyed much," he said, "but that

delightful botanical and geological tour I shall never forget; and I

am just about to start in the Titania for a trip round the

east coast of Scotland, returning south through the Caledonian

Canal, to refresh myself with the recollection of the first and

brightest tour of my life."

Toward the end of the summer the young student returned to

Killingworth to re-enter upon the active business of life. The

six months' study had cost his father £80—a considerable sum to him

in those days; but he was amply repaid by the additional scientific

culture which his son had acquired, and the evidence of ability and

industry which he was enabled to exhibit in a prize for mathematics

which he had won at the University.

We may here add that by this time George Stephenson, after

remaining a widower fourteen years, had married, in 1820, his second

wife, Elizabeth Hindmarsh, the daughter of a respectable farmer at

Black Callerton. She was a woman of excellent character,

sensible, and intelligent, and of a kindly and affectionate nature.

George's son Robert, whom she loved as if he had been her own, to

the last day of his life spoke of her in the highest terms; and it

is unquestionable that she contributed in no small degree to the

happiness of her husband's home.

The story was for some time current that, while living at

Black Callerton in the capacity of engine-man, twenty years before,

George had made love to Miss Hindmarsh, and, failing to obtain her

hand, in despair he had married Paterson's servant. But the

author has been assured by Mr. Thomas Hindmarsh, of Newcastle, the

lady's brother, that the story was mere idle gossip, and altogether

without foundation.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER VIII.

GEORGE STEPHENSON ENGINEER OF THE STOCKTON AND DARLINGTON RAILWAY.

IT

is not improbable that the slow progress made by railways in public

estimation was, in a considerable measure, due to the comparative

want of success which had attended the first projects. We do

not refer to the tram-roads and railroads which connected the

collieries and iron-works with the shipping-places. These were

found convenient and economical, and their use became general in

Durham and Northumberland, in South Wales, in Scotland, and

throughout the colliery districts. But none of these were

public railways. Though the Merthyr Tydvil Tram-road, the

Sirhoway Railroad, and others in South Wales, were constructed under

the powers of special acts, they were exclusively used for the

private purposes of the coal-owners and iron-masters at whose

expense they were made. [p.216]

The first public Railway Act was that passed in 1801,

authorizing the construction of a line from Wandsworth to Croydon,

under the name of "The Surrey Iron Railway." By a subsequent

act, powers were obtained to extend the line to Reigate, with a

branch to Godstone. The object of this railway was to furnish

a more ready means for the transport of coal and merchandise from

the Thames to the districts of south London, and at the same time to

enable the lime-burners and proprietors of stone-quarries to send

the lime and stone to London. With this object, the railroad

was connected with a dock or basin in Wandsworth Creek capable of

containing thirty barges, with an entrance lock into the Thames.

The works had scarcely been commenced ere the company got

into difficulties, but eventually 26 miles of iron-way were

constructed and opened for traffic. Any person was then at

liberty to put wagons on the line, and to carry goods within the

prescribed rates, the wagons being worked by horses, mules, and

donkeys. Notwithstanding the very sanguine expectations which

were early formed as to the paying qualities of this railway, it

never realized any adequate profit to the owners. But it

continued to be worked, principally by donkeys for the sake of

cheapness, down to the passing of the act for constructing the

London and Brighton line in 1837, when the proprietors disposed of

their undertaking to the new company. The line was accordingly

dismantled; the stone blocks and rails were taken up and sold; and

all that remains of the Wandsworth, Croydon, and Merstham Railway is

the track still observable to the south of Croydon, along Smitham

Bottom, nearly parallel with the line of the present Brighton

Railway, and an occasional cutting and embankment, which still mark

the route of this first public railway.

The want of success of this undertaking doubtless had the

effect of deterring projectors from embarking in any similar

enterprise. If a line of the sort could not succeed near

London, it was thought improbable that it should succeed anywhere

else. The Croydon and Merstham line was a beacon to warn

capitalists against embarking in railways, and many years passed

before another was ventured upon.

Sir Richard Phillips was one of the few who early recognized

the important uses of the locomotive and its employment on a large

scale for the haulage of goods and passengers by railway. In

his "Morning Walk to Kew" he crossed the line of the Wandsworth and

Croydon Railway, when the idea seems to have occurred to him, as it

afterwards did to Thomas Gray, that in the locomotive and the

railway were to be found the germs of a great and peaceful social

revolution:

"I found delight," said Sir Richard, in his book published in

1813,

"in witnessing at Wandsworth the economy of horse

labour on the iron railway. Yet a heavy sigh escaped me as I

thought of the inconceivable millions of money which have been spent

about Malta, four or five of which might have been the means of

extending double lines of iron railway from London to Edinburgh,

Glasgow, Holyhead, Milford, Falmouth, Yarmouth, Dover, and

Portsmouth. A reward of a single thousand would have supplied

coaches and other vehicles, of various degrees of speed, with the

best tackle for readily turning out; and we might, ere this, have

witnessed our mail-coaches running at the rate of ten miles an hour

drawn by a single horse, or impelled fifteen miles an hour by

Blenkinsop's steam-engine. Such would have been a legitimate

motive for over-stepping the income of a nation, and the completion

of so great and useful a work would have afforded rational ground

for public triumph in general jubilee."

There was, however, as yet, no general recognition of the

advantages either of railways or locomotives. The government

of this country never leads in any work of public enterprise, and is

usually rather a drag upon industrial operations than otherwise.

As for the general public, it was enough for them that the

Wandsworth and Croydon Railway did not pay.

Mr. Tredgold, in his "Practical Treatise on Railroads and

Carriages," published in 1825, observes:

"Up to this period railways have

been employed with success only in the conveyance of heavy mineral

products, and for short distances where immense quantities were to

be conveyed. In the few instances where they have been intended for

the general purposes of trade, they have never answered the

expectations of their projectors. But this seems to have arisen

altogether from following too closely the models adopted for the

conveyance of minerals, such modes of forming and using railways not

being at all adapted for the general purposes of trade."

The ill success of railways was generally recognized.

Joint-stock companies for all sorts of purposes were formed during

the joint-stock mania of 1821, but few projectors were found daring

enough to propose schemes so unpromising as railways. Hence

nearly twenty years passed between the construction of the first and

the second public railway in England; and this brings us to the

projection of the Stockton and Darlington, which may be regarded as

the parent public locomotive railway in the kingdom.

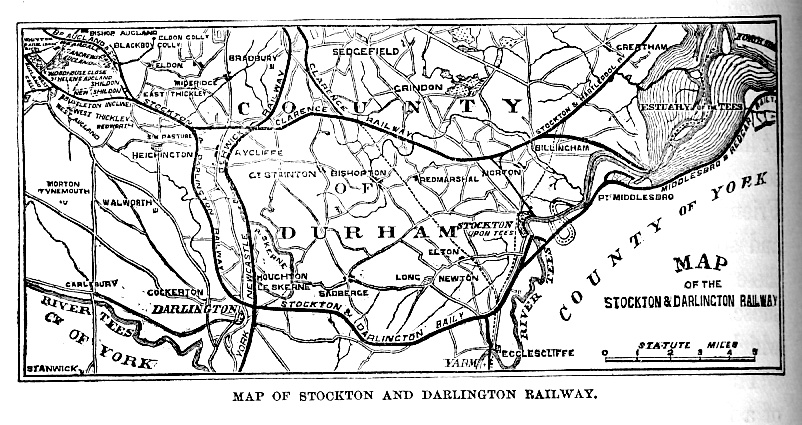

The district lying to the west of Darlington, in the county

of Durham, is one of the richest mineral fields of the North.

Vast stores of coal underlie the Bishop Auckland Valley, and from an

early period it was felt to be an exceedingly desirable object to

open up new communications to enable the article to be sent to

market. But the district lay a long way from the sea, and, the

Tees being unnavigable, there was next to no vend for the Bishop

Auckland coal.

It is easy to understand, therefore, how the desire to obtain

an outlet for this coal for land sale, as well as for its transport

to London by sea, should have early occupied the attention of the

coal-owners in the Bishop Auckland district. The first idea

that found favour was the construction of a canal. About a

century ago, in 1766, shortly after the Duke of Bridgewater's Canal

had been opened between Worsley and Manchester, a movement was set

on foot at Darlington with the view of having the country surveyed

between that place and Stockton-on-Tees.

Brindley was requested to lay out the proposed line of canal;

but he was engrossed at the time by the prosecution of the works on

the Duke's Canal to Liverpool, and Whitworth, his pupil and

assistant, was employed in his stead; George Dixon, grandfather of

John Dixon, engineer of the future Stockton and Darlington Railway,

taking an active part in the survey. In October, 1768,

Whitworth presented his plan of the proposed canal from Stockton by

Darlington to Winston, and in the following year, to give weight to

the scheme, Brindley concurred with him in a joint report as to the

plan and estimate.

Nothing was, however, done in the matter. Enterprise

was slow to move. Stockton waited for Darlington, and

Darlington waited for Stockton, but neither stirred until twenty

years later, when Stockton began to consider the propriety of

straightening the Tees below that town, and thereby shortening and

improving the navigation. When it became known that some

engineering scheme was afoot at Stockton, that indefatigable writer

of prospectuses and drawer of plans, Ralph Dodd, the first projector

of a tunnel under the Thames, the first projector of the Waterloo

Bridge, and the first to bring a steam-boat from Glasgow into the

Thames, addressed the Mayor and Corporation of Stockton in 1796 on

the propriety of forming a line of internal navigation by Darlington

and Staindrop to Winston. Still nothing was done. Four

years later, another engineer, George Atkinson, reported in favour

of a waterway to connect the then projected Great Trunk Canal, from

about Boroughbridge to Piersebridge, with the Tees above Yarm.

At length, in 1808, the Tees Navigation Company, slow in

their movements, obtained an act enabling them to make the short cut

projected seventeen years before, and two years later the cut was

opened, and celebrated by the inevitable dinner. The Stockton

people, who adopted as the motto of their company "Meliora speramus,"

held a public meeting after the dinner to meditate upon and discuss

the better things to come. They appointed a committee to

inquire into the practicability and advantages of forming a

railway or canal from Stockton by Darlington to Winston.

Here, then, in 1810, we have the first glimpse of the railway; but

it was long before the idea germinated and bore fruit. The

collieries must be got at to make the new cut a success, but how

for a long time remained the question.

Sixteen months passed, and the committee at Stockton went to

sleep. But it came up again, and this time at Darlington, with

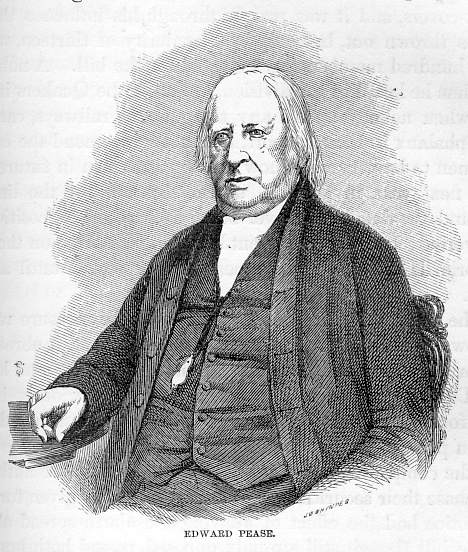

Edward Pease as one of the members. The Darlington committee

met and made their report, but they could not decide between the

respective merits of a railroad and a canal. It was felt that

either would be of great advantage. To settle the question,

they determined to call the celebrated engineer, John Rennie, to

their aid, and he was ready with his report in 1813. His

report was not published, but it is understood that he was in favour

of a canal on Brindley and Whitworth's line, though he afterward

inclined to a tram-road. Still nothing was done. War was on

foot in Europe, and enterprise was every where dormant. The

scheme must therefore wait the advent of peace. At length

peace came, and with it a revival of former projects.

At Newcastle, a plan was set on foot for connecting the Tyne

with the Solway Frith by a canal. A county meeting was held on

the subject in August, 1817, under the presidency of the high

sheriff. Previous to this time, Sir John Swinburne had stood

up for a railway in preference to a canal; but when the meeting took

place, the opinion of those present was in favour of a canal—Mr.

William Armstrong (father of the present Sir William) being one of

the most zealous advocates of the water-road. Yet there were

even then railroads in the immediate neighbourhood of Newcastle, at

Wylam and Killingworth, which had been successfully and economically

worked by the locomotive for years past, but which the Northumbrians

seem completely to have ignored. The public head is usually

very thick, and it is difficult to hammer a new idea into it. Canals

were established methods of conveyance, and were every where

recognized; whereas railways were new things, and were straggling

hard to gain a footing. Besides, the only public railway in

England, the Wandsworth, Croydon, and Merstham, had proved a

commercial failure, and was held up as a warning to all speculators

in tram-ways. But, though the Newcastle meeting approved of a

canal in preference to a railway from the Tyne to the Solway,

nothing was really done to promote the formation of either.

The movement in favour of a canal was again revived at

Stockton. A requisition, very numerously signed by persons of

influence in South Durham, was presented to the Mayor of Stockton in

May, 1818, requesting him to convene a public meeting "to consider

the expediency of forming a canal for the conveyance of coal, lime,

etc., from Evenwood Bridge, near West Auckland, to the River Tees,

upon a plan recently made by Mr. George Leatham, engineer."

Among the names attached to the petition we find those of Edward,

John, and Thomas Pease, and John Dixon, Darlington. They were

doubtless willing to pull with any party that would open up a way,

whether by rail or by water, between the Bishop Auckland coal-field

and Stockton, whether the line passed through Darlington or not.

An enthusiastic meeting was held at Stockton, and a committee

was appointed, by whom it was resolved to apply to Parliament for an

act to make the intended canal "if funds are forthcoming."

Never was there greater virtue in an if. Funds were not

forthcoming; the project fell through, and a great blunder was

prevented. When the Stockton men had discussed and resolved

without any practical result, the leading men of Darlington took up

the subject by themselves, determined, if possible, to bring it to

some practical issue. In September, 1818, they met under the

presidency of Thomas Meynell, Esq. Mr. Overton, who had laid

down several coal railways in Wales, was consulted, and, after

surveying the district between the Bishop Auckland coal-field and

the Tees, sent in his report. Mr. Rennie also was again

consulted. Both engineers gave their opinion in favour of a

railway by Darlington in preference to a canal by Auckland, "whether

taken as a line for the exportation of coal or as one for a local

trade." The committee accordingly reported in favour of the

railway.

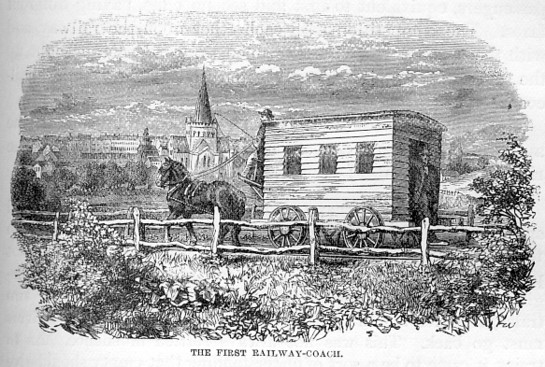

It is curious now to look back at the modest estimate of

traffic formed by the committee. They considered that the

export trade in coal "might be taken, perhaps, at 10,000 tons a

year, which is about one cargo a week!" It was intended to

haul the coal by horse-power; a subsequent report stating "on

undoubted authority" that one horse of moderate power could easily

draw downward on the railway, between Darlington and Stockton, about

ten tons, and upward about four tons of loading, exclusively of the

empty wagons. No allusion was made to passengers in any of the

reports; nor did the committee at first contemplate the

accommodation of traffic of this description.

A survey of the line was then ordered, and steps were taken

to apply to Parliament for the necessary powers to construct the

railway. But the controversy was not yet at an end.

Stockton stood by its favourite project of a canal, and would not

subscribe a farthing toward the projected railway; but neither did

it subscribe toward the canal. The landlords, the road

trustees, the carriers, the proprietors of donkeys (by whom coals

were principally carried for inland sale), were strenuously opposed

to the new project; while the general public, stupid and sceptical,

for the most part stood aloof, quoting old saws and keeping their

money in their pockets.

Several energetic men, however, were now at the head of the

Stockton and Darlington Railway project, and determined to persevere

with it. Among these, the Peases were the most zealous.

Edward Pease might be regarded as the back-bone of the concern.

Opposition did not daunt him, nor failure discourage him. When

apparently overthrown and prostrate, he would rise again like Antæus,

stronger than before, and renew his efforts with increased vigour.

He had in him the energy and perseverance of many men. One who

knew him in 1818 said, "He was a man who could see a hundred years

ahead." When the author last saw him in 1854, a few years

before his death, Mr. Pease was in his eighty-eighth year; yet he

still possessed the hopefulness and mental vigour of a man in his

prime. Still sound in health, his eye had not lost its

brilliancy, nor his cheek its colour, and there was an elasticity in

his step which younger men might have envied.

In getting up a company for surveying and forming a railway,

Mr. Pease had great difficulties to encounter. The people of

the neighbourhood spoke of it as a ridiculous undertaking, and

predicted that it would be ruinous to all concerned in it.

Even those most interested in the opening up of new markets for the

sale of their coal were indifferent, if not hostile. Mr. Pease

nevertheless persevered in the formation of a company, and he

induced many of his friends and relations to follow his example.

The Richardsons and Backhouses, members, like himself, of the

Society of Friends, influenced by his persuasion, united themselves

with him; and so many of the same denomination (having confidence in

these influential Darlington names) followed their example and

subscribed for shares, that the railway obtained the designation,

which it long retained, of "The Quakers' Line."

The Stockton and Darlington scheme had to run the gauntlet of

a fierce opposition in three successive sessions of Parliament.

The application of 1818 was defeated by the Duke of Cleveland who

afterward profited so largely by the railway. The ground of

his opposition was that the line would interfere with his

fox-covers, and it was mainly through his influence that the bill

was thrown out, but only by a majority of thirteen, upward of one

hundred members having voted for the bill. A nobleman said,

when he heard of the division, "Well, if the Quakers in these times,

when nobody knows any thing about railways, can raise such a phalanx

in their support, I should recommend the country gentlemen to be

very wary how they oppose them in future."

The next year, in 1819, an amended survey of the line was

made, and, the duke's fox-cover being avoided, his opposition was

thus averted; but, on Parliament becoming dissolved on the death of

George III., the bill was necessarily suspended until another

session. |

|

In the mean time the local opposition to the measure revived,

and now it was led by the road trustees, who spread it abroad that

the mortgagees of the tolls arising from the turnpike-road leading

from Darlington to West Auckland would be seriously injured by the

formation of the proposed railway. On this, Edward Pease

issued a printed notice, requesting any alarmed mortgagee to apply

to the company's solicitors at Darlington, who were authorised to

purchase their securities at the prices originally given for them.

This notice had the effect of allaying the alarm spread abroad; and

the bill, though still strongly opposed, passed both houses of

Parliament in 1821.

The preamble of the act sets forth the public utility of the

proposed line for the conveyance of coal and other commodities from

the interior of the county of Durham to Stockton and the northern

parts of Yorkshire. Nothing was said about passengers, for

passenger-traffic was not yet contemplated; and nothing was said

about locomotives, as it was at first intended to work the line

entirely by horse-power. The road was to be free to all

persons who chose to place their wagons and horses upon it for the

haulage of coal and merchandise, provided they paid the tolls fixed

by the act.

The company were empowered to charge fourpence a ton per mile

for all coal intended for land sale, but only a halfpenny a ton per

mile for coal intended for shipment at Stockton. This latter

proviso was inserted at the instance of Mr. Lambton, afterward Earl

of Durham, for the express purpose of preventing the line being used

in competition against his coal loaded at Sunderland; for it was not

believed possible that coal could be carried at that low rate except

at a heavy loss. As it was, however, the rate thus fixed by

the act eventually proved the vital element of success in the

working of the undertaking.

While the Stockton and Darlington Railway scheme was still

before Parliament, we find Edward Pease writing letters to a York

paper, urging the propriety of extending it southward into Yorkshire

by a branch from Croft. It is curious now to look back upon

the arguments by which Mr. Pease sought to influence public opinion

in favour of railways, and to observe the very modest anticipations

which even its most zealous advocate entertained as to their

supposed utility and capabilities:

"The late improvements in the

construction of railways," Mr. Pease wrote, "have rendered them much

more perfect than when constructed after the old plan. To such

a degree of utility have they now been brought that they may be

regarded as very little inferior to canals.

"If we compare the railway with the best lines of common

road, it may be fairly stated that in the case of a level railway

the work will be increased in at least an eightfold degree.

The best horse is sufficiently loaded with three quarters of a ton

on a common road, from the undulating line of its draught, while on

a railway it is calculated that a horse will easily draw a load of

ten tons. At Lord Elgin's works, Mr. Stevenson, the celebrated

engineer, states that he has actually seen a horse draw twenty-three

tons thirteen cwt. upon a railway which was in some parts level, and

at other parts presented a gentle declivity!

"The formation of a railway, if it creates no improvement in

a country, certainly bars none, as all the former modes of

communication remain unimpaired; and the public obtain, at the risk

of the subscribers, another and better mode of carriage, which it

will always be to the interest of the proprietors to make cheap and

serviceable to the community.

"On undertakings of this kind, when compared with canals, the

advantages of which (where an ascending or descending line can be

obtained) are nearly equal, it may be remarked that public opinion

is not easily changed on any subject. It requires the

experience of many years, sometimes ages, to accomplish this, even

in cases which by some may be deemed obvious. Such is the

effect of habit, and such the aversion of mankind to any thing like

innovation or change. Although this is often regretted, yet,

if the principle be investigated in all its ramifications, it will

perhaps be found to be one of the most fortunate dispositions of the

human mind.

"The system of cast-iron railways is as yet to be considered

but in its infancy. It will be found to be an immense

improvement on the common road, and also on the wooden railway.

It neither presents the friction of the tram-way, nor partakes of

the perishable nature of the wooden railway, and, as regards

utility, it may be considered as the medium between the navigable

canal and the common road. We may therefore hope that as this

system develops itself, our roads will be laid out as much as

possible on one level, and in connection with the great lines of

communication throughout the country."

Such were the modest anticipations of Edward Pease respecting

railways in the year 1821. Ten years later, an age of

progress, by comparison, had been effected.

Some time elapsed before any active steps were taken to

proceed with the construction of the railway. Doubts were

raised whether the line was the best that could be adopted for the

district, and the subscribers generally were not so sanguine about

the undertaking as to induce them to press it forward.

One day, about the end of the year 1821, two strangers

knocked at the door of Mr. Pease's house in Darlington, and a

message was brought to him that some persons from Killingworth

wanted to speak with him. They were invited in, on which one

of the visitors introduced himself as Nicholas Wood, viewer at

Killingworth, and then turning to his companion, he introduced him

as George Stephenson, engine-wright, of the same place.

Mr. Pease entered into conversation with his visitors, and

was soon told their object. Stephenson had heard of the

passing of the Stockton and Darlington Act, and desiring to increase

his railway experience, and also to employ in some larger field the

practical knowledge he had already acquired, he determined to visit

the known projector of the undertaking, with the view of being

employed to carry it out. He had brought with him his friend

Wood for the purpose at the same time of relieving his diffidence

and supporting his application.

Mr. Pease liked the appearance of his visitor: "there was,"

as he afterward remarked when speaking of Stephenson, "such an

honest, sensible look about him, and he seemed so modest and

unpretending. He spoke in the strong Northumbrian dialect of

his district, and described himself as 'only the engine-wright at

Killingworth; that's what he was.'"

Mr. Pease soon saw that our engineer was the very man for his

purpose. The whole plans of the railway were still in an

undetermined state, and Mr. Pease was therefore glad to have the

opportunity of profiting by Stephenson's experience. In the

coarse of their conversation, the latter strongly recommended a

railway in preference to a tram-road. They also discussed

the kind of tractive power to be employed, Mr. Pease stating that

the company had based their whole calculations on the employment of

horse-power. "I was so satisfied," said he afterward,

"that a horse upon an iron road would draw ten tons for one ton on a

common road, that I felt sure that before long the railway would

become the king's highway."

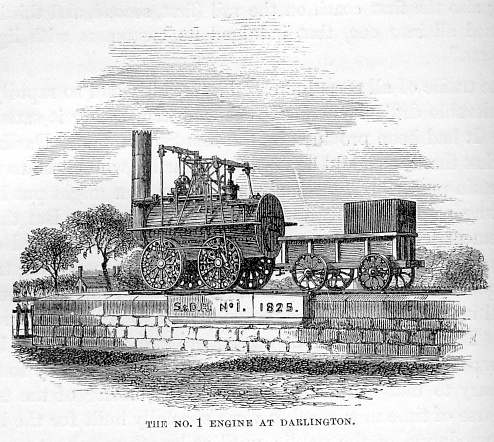

But Mr. Pease was scarcely prepared for the bold assertion

made by his visitor, that the locomotive engine with which he had

been working the Killingworth Railway for many years past was worth

fifty horses, and that engines made after a similar plan would yet

entirely supersede all horse-power upon railroads. Stephenson

was daily becoming more positive as to the superiority of his

locomotive, and hence he strongly urged Mr. Pease to adopt it. "Come

over to Killingworth," said he, "and see what my engines can do;

seeing is believing, sir." Mr. Pease accordingly promised that

on some early day he would go over to Killingworth, and take a look

at the wonderful machine that was to supersede horses.

The result of the interview was, that Mr. Pease promised to

bring Stephenson's application for the appointment of engineer

before the directors, and to support it with his influence; whereon

the two visitors prepared to take their leave, informing Mr. Pease

that they intended to return to Newcastle "by nip;" that is, they

expected to get a smuggled lift on the stage-coach by tipping

Jehu—for in those days the stage-coachmen regarded all casual

roadside passengers as their proper perquisites. They had,

however, been so much engrossed by their conversation that the lapse

of time was forgotten, and when Stephenson and his friend made

inquiries about the return coach, they found the last had left, and

they had to walk eighteen miles to Durham on their way back to

Newcastle.

Mr. Pease having made farther inquiries respecting

Stephenson's character and qualifications, and having received a

very strong recommendation of him as the right man for the intended

work, he brought the subject of his application before the directors

of the Stockton and Darlington Company. They resolved to adopt

his recommendation that a railway be formed instead of a tram-road;

and they farther requested Mr. Pease to write to Stephenson,

desiring him to undertake a resurvey of the line at the earliest

practicable period.

A man was dispatched on a horse with the letter, and when he

reached Killingworth he made diligent inquiry after the person named

on the address, "George Stephenson, Esquire, Engineer." No

such person was known in the village. It is said that the man

was on the point of giving up all farther search, when the happy

thought struck some of the colliers' wives who had gathered about

him that it must be "Geordie the engine-wright" the man was in

search of, and to Geordie's cottage he accordingly went, found him

at home, and delivered the letter.

About the end of September Stephenson went carefully over the

line of the proposed railway for the purpose of suggesting such

improvements and deviations as he might consider desirable. He

was accompanied by an assistant and a chainman, his son Robert

entering the figures while his father took the sights. After

being engaged in the work at interval for about six weeks,

Stephenson reported the result of his survey to the Board of

Directors, and showed that, by certain deviations, a line shorter by

about three miles might be constructed at a considerable saving in

expense, while at the same time more favourable gradients—an

important consideration—would be secured.

It was, however, determined in the first place to proceed

with the works at those parts of the line where no deviation was

proposed, and the first rail of the Stockton and Darlington Railway

was laid with considerable ceremony, near Stockton, on the 23d of

May, 1822.

It is worthy of note that Stephenson, in making his first

estimate of the cost of forming the railway according to the

instructions of the directors, set down, as part of the cost, £6200

for stationary engines, not mentioning locomotives at all. It

was the intention of the directors, in the first place, to employ

only horses for the haulage of the coals, and fixed engines and

ropes where horse-power was not applicable. The whole question

of steam-locomotive power was, in the estimation of the public, as

well as of practical and scientific men, as yet in doubt. The

confident anticipations of George Stephenson as to the eventual

success of locomotive engines were regarded as mere speculations;

and when he gave utterance to his views, as he frequently took the

opportunity of doing, it even had the effect of shaking the

confidence of some of his friends in the solidity of his judgment

and his practical qualities as an engineer.

When Mr. Pease discussed the question with Stephenson, his

remark was, "Come over and see my engines at Killingworth, and

satisfy yourself as to the efficiency of the locomotive. I

will show you the colliery books, that you may ascertain for

yourself the actual cost of working. And I must tell you that

the economy of the locomotive engine is no longer a matter of

theory, but a matter of fact." So confident was the tone in

which Stephenson spoke of the success of his engines, and so

important were the consequences involved in arriving at a correct

conclusion on the subject, that Mr. Pease at length resolved on

paying a visit to Killingworth in the summer of 1822, in company

with his friend Thomas Richardson, a considerable subscriber to the

Stockton and Darlington undertaking to inspect the wonderful new

power so much vaunted by their engineer. [p.230-1]

When Mr. Pease arrived at Killingworth village, he inquired

for George Stephenson, and was told that he must go over to the West

Moor, and seek for a cottage by the roadside with a dial over the

door—"that was where George Stephenson lived." They soon found

the house with the dial, and, on knocking, the door was opened by

Mrs. Stephenson. In answer to Mr. Pease's inquiry for her

husband, she said he was not in the house at present, but that she

would send for him to the colliery. And in a short time

Stephenson appeared before them in his working dress, just as he had

come out of the pit.

He very soon had his locomotive brought up to the crossing

close by the end of the cottage, made the gentlemen mount it, and

showed them its paces. Harnessing it to a train of loaded

wagons, he ran it along the railroad, and so thoroughly satisfied

his visitors of its power and capabilities, that from that day

Edward Pease was a declared supporter of the locomotive engine.

In preparing the Amended Stockton and Darlington Act, at

Stephenson's urgent request Mr. Pease had a clause inserted, taking

power to work the railway by means of locomotive engines, and to

employ them for the haulage of passengers as well as of merchandise.

[p.230-2] The act

was obtained in 1823, on which Stephenson was appointed the

Company's engineer, at a salary of £300 per annum; and it was

determined that the line should be constructed and opened for

traffic as soon as practicable.

He at once proceeded, accompanied by his assistants, with the

working survey of the line, laying out every foot of the ground

himself. Railway surveying was as yet in its infancy, and was

slow and difficult work. It afterward became a separate branch

of railway business, and was intrusted to a special staff.

Indeed, on no subsequent line did George Stephenson take the sights

through the spirit-level with his own hands and eyes as he did on

this railway. He started very early—dressed in a blue tailed

coat, breeches, and top-boots—and surveyed until dusk. He was

not at any time particular as to his living; and, during the survey,

he took his chance of getting a little milk and bread at some

cottager's house along the line, or occasionally joined in a homely

dinner at some neighbouring farm-house. The country people

were accustomed to give him a hearty welcome when he appeared at

their door, for he was always full of cheery and homely talk, and,

when there were children about the house, he had plenty of humorous

chat for them as well as for their seniors.

After the day's work was over, George would drop in at Mr.

Pease's to talk over the progress of the survey, and discuss various

matters connected with the railway. Mr. Pease's daughters were

usually present; and, on one occasion, finding the young ladies

learning the art of embroidery, he volunteered to instruct them. [p.231]

"I know all about it," said he, "and you will wonder how I learned

it. I will tell you. When I was a brakesman at

Killingworth, I learned the art of embroidery while working the

pitmen's button-holes by the engine fire at nights." He was

never ashamed, but, on the contrary, rather proud, of reminding his

friends of these humble pursuits of his early life. Mr.