|

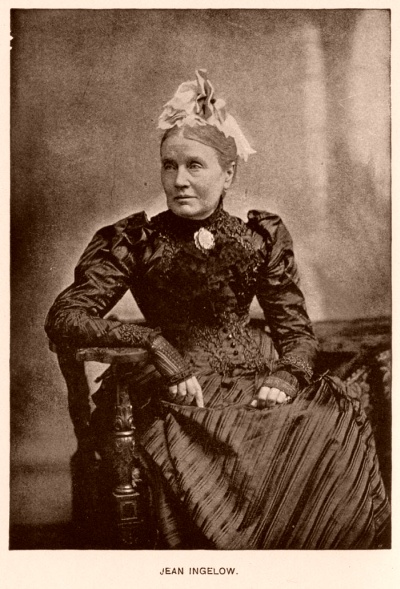

Poetess, novelist and author of charming

children's stories.

|

"A healthful hunger

for a great idea is the

beauty and

blessedness of life." |

"Why, if the swarms in the weaving and the spinning world are to be

thinned, who will bring a

revenue to the cotton-lord? If the crowded alley is to be deserted, who

will make our shirts and our gowns? and if at the parish school we bring

up all the children to fly like nestlings as soon as they are fledged,

where are our housemaids and nursemaids and cookmaids to come from?. . . . No; truly God made my

servant what he is; God placed me over him: let him work — it is his duty;

let me play — it is my birthright; and let none of us presume to wish

that God had placed us otherwise! That is what people say — at

least a great many of them."

Jean Ingelow on the

generally accepted need for the lower classes.

(1820-97)

Photo by Barrauds.

"At her Kensington home she gives what she calls

her "copyright dinners" — because they are paid for from the proceeds of

her books — at which she gathers poor people, old and young, to share her

pleasant bounty."

There's no such

thing as a 'free meal', except at Jean Ingelow's . . . Harper's Magazine, May 1888.

"Some of our writers have taken lately to ill-using our neat

and compact verb by ramming an adverb into its midst. They will

say, — 'To appreciatively drink bottled stout'; 'To energetically walk to

Paddington'; 'To incessantly think'; 'To ably reason'. Where was

this dog-English whelped? You should say, 'to think incessantly',

'to reason ably'. Let us suppose that 'bow-wow' means to drink.

Do you ever hear your dog say 'Bow — wagging my tail —wow'? . . .

Writing vulgar or ugly English is not

an indictable offence. I only wish it was . . ."

Jean Ingelow on the split infinitive.

"She was a

kind-looking, pleasant, middle-aged lady, with a fresh complexion

and brown hair, who cannot be better described than by saying that

she was very like her own writings. She looked a thoroughly

wholesome, practical person. Dr. Japp said to me long

afterwards that she had always seemed to him the very type of a

country banker's maiden sister."

ISABELLA

FYVIE

MAYO,

from

Recollections.

"A lady writer in an American paper thus described Jean Ingelow the

poetess:―"Miss Ingelow is a buxom,

fine-looking woman, somewhere near her forties. She has an

abundance of soft brown hair, which she winds in a graceful fashion

of her own about her well-shaped head; bright dark eyes, and a

lovely changing colour, which comes and goes in her cheeks at the

slightest provocation. She is shy, delicate, and reserved, and

has a true English aversion to being looked at, and a still greater

horror of being written about. Miss Ingelow is a thorough

Conservative in ideas as well as tastes."

THE

ABERDEEN JOURNAL

(8th May, 1872)

―――♦―――

Born at Boston,

Lincolnshire, JEAN INGELOW

was the eldest of the ten children of William Ingelow, a banker and

shipping merchant, and his

Scots wife, Jean. Following the failure of his banking business, the

family moved to Ipswich and then to London, where Jean spent the rest of

her life.

|

"My father’s house stood in a quiet country town,

through which a tidal river flowed. The banks of the river

were flanked by wooden wharves, which were supported on timbers, and

projected over the water. They had granaries behind them, and

one of my earliest pleasures was to watch the gangs of men who at

high tide towed vessels up the river, where, being moored before

these granaries, cargoes of corn were shot down from the upper

stories into their holds, through wooden troughs not unlike

fire-escapes. The back of my father’s house was on a level

with the wharves, and overlooked a long reach of the river.

Our nursery was a low room in the roof, having a large bow window,

in the old-fashioned seat of which I spent many a happy hour with my

brother, sometimes listening to the soft hissing sound made by the

wheat in its descent, sometimes admiring the figure-heads of the

vessels, or laboriously spelling out the letters of their names."

A description of childhood, from

. . . .

Off

the Skelligs. |

Educated at home by her mother and an aunt, while still a

girl Jean contributed poetry and tales to magazines under the pseudonym of

Orris. However, her first volume, A Rhyming Chronicle of

Incidents and Feelings, published anonymously, did not appear until

she was thirty. It impressed another Lincolnshire poet, Tennyson, with whom she was to become friends

(see letter). She followed this book of verse

with a novel, Allerton and Dreux [Vol. I;

Vol. II], published anonymously

in 1851. A reviewer described this work as "essentially religious, with a

spirit of earnest piety and serious feeling pervading throughout":

"essentially religious", I think, only sufficient to be remarked

upon in the early chapters,

and the story evolves

— but

slowly at times

(likewise in Off the Skelligs and Fated to be Free)

—

into an

interesting romance cum adventure, in which the personalities of two of its principals, Messrs

Dreux and Hewley, bearing some slight resemblance to Trollope's better

known divines (then yet to appear), Messrs Crawley and Slope.

|

"He was about the middle height,

extremely slender, had deep-set eyes, very smooth black

hair, and used to walk with an air of deep humility, his

eyes generally fixed on the ground. He seldom looked

any one in the face, spoke in a low, internal voice, and

often sighed deeply. He was not by any means without

his admirers, but most even of these were afraid of him.

He generally conveyed his wishes by insinuation, and

exercised his influence in an underhand way" . . . .

"Oh the annoyance of

being with one's superiors! thought Mr. Hewly, as the

conviction became more strong in his mind than ever, that

this man [Mr. Dreux], his own curate, was so far above him,

that he actually could not feel at ease with him, even in

his own house, unless he treated him with proper respect. .

. . When a man, remarkable for uprightness and honesty of

purpose, gets into contact with one of sinister disposition,

not at all straightforward, and conscious of defective

motives, he is sure to make him feel extremely

uncomfortable; he feels acutely that he is not honest, and

fancies the other feels it too."

Messrs Hewly and Dreux, from . . . .

Allerton and Dreux. |

From 1852,

Jean

contributed regularly to the evangelical Youth Magazine under her

pseudonym and was for a short time its editor. A compilation of these children's stories,

Tales

of Orris, illustrated by the eminent Pre-Raphaelite

artist, John Everett Millais,

appeared in 1860 and was well received (mostly repeated in Stories told

to a Child). However, major success was

to come in 1863 with Poems, a work that

ran through thirty editions in Jean's lifetime and met with wide acclaim in

the United States.

Poems commences with "Divided",

a tale in which two lovers walk happily hand-in-hand along opposite sides of a

rivulet. The rivulet broadens gradually into a stream as

it flows seaward and their handhold eventually breaks

across the widening gap. But they continue on regardless; they call to each other to come across,

but neither does. The

stream widens slowly into a river,

then into an estuary

and eventually the lovers lose sight of each other across the broad expanse, thus becoming

divided—

|

. . . .

Sing on! we sing in the glorious weather

Till one steps over the tiny strand,

So narrow, in sooth, that still together

On either brink we go hand in hand.

The beck grown wider, the hands must sever,

On either margin, our songs all done,

We move apart, while she singeth ever,

Taking the course of the stooping sun.

He prays "Come over"— I may not follow;

I cry "Return"—but he cannot come:

We speak, we laugh, but with voices hollow;

Our hands are hanging, our hearts are

numb.

A little pain when the beck grows wider;

"Cross to me now—for her wavelets swell:"

"I may not cross "—and the voice beside her

Faintly reacheth, tho' heeded well.

No backward path; ah! no returning;

No second crossing that ripple's flow

"Come to me now, for the West is burning;

Come ere it darkens;"—"Ah, no! ah, no!"

Then cries of pain, and arms outreaching—

The beck grows wider and swift and deep:

Passionate words as of one beseeching—

The loud beck drowns them; we walk, we

weep.

A braver swell, a swifter sliding;

The River hasteth, her banks recede:

Wing-like sails on her bosom gliding

Bear down the lily and drown the reed.

Stately prows are rising and bowing

(Shouts of mariners winnow the air),

And level sands for banks endowing

The tiny green ribbon that showed so fair.

While, O my heart! as white sails shiver,

And crowds are passing, and banks stretch

wide,

How hard to follow, with lips that quiver,

That moving speck on the far-off side.

Farther, farther—I see it—I know it—

My eyes brim over, it melts away;

Only my heart to my heart shall show it

As I walk desolate day by day . . . . |

|

The Cambridge History of English and American

Literature . . . . .

" . . . . if we had nothing of Jean Ingelow’s but the most

remarkable poem entitled Divided, it would be permissible to suppose

the loss, in fact or in might-have-been, of a poetess of almost the

highest rank. Absolutely faultless it is not; a very harsh critic

might urge even here a little of the diffuseness which has been

sometimes charged against the author’s work generally; a less stern

judge might not quite pardon a few affectations and “gushes,”

something like those of Tennyson’s early work. It might be

called sentimental by those who confound true and false sentiment in

one condemnation. But the theme and the allegorical imagery by

which it is carried out are true; the description, not merely

plastered on, but arising out of the necessary treatment of the

theme itself, is admirable; the pathos never becomes mawkish; and,

to crown all, the metrical appropriateness of the measure chosen and

the virtuosity with which it is worked out leave nothing to desire.

Jean Ingelow wrote some other good things, but nothing at all

equalling this; while she also wrote too much and too long.

If, as has been suggested above, this disappointingness is even

commoner with poetesses than with poets, there is a possible

explanation of it in the lives, more unoccupied until recently, of

women. Unless a man is an extraordinary coxcomb, a person of

private means, or both, he seldom has the time and opportunity of

committing, or the wish to commit, bad or indifferent verse for a

long series of years; but it is otherwise with woman. |

|

. . . . but true love cannot divide . . . .

|

And yet I know past all doubting, truly—

A knowledge greater than grief can dim—

I know, as he loved, he will love me duly—

Yea better—e'en better than I love him.

And as I walk by the vast calm river,

The awful river so dread to see,

I say, "Thy breadth and thy depth for ever

Are bridged by his thoughts that cross to me."

|

There has been much speculation over Jean's affaires

du coeur ― of which more below

― and one cannot help but feel that

an autobiographical theme underpins this pensive lyric.

|

"I have never been inside a

theatre in my life. I always say on such occasions,

that although our parents never took us, and I never go

myself out of habit and affectionate respect for their

memory, I do not wish to give an opinion or to say that

others are wrong to go. We must each act according to

our own convictions, and must ever use all tolerance towards

those who differ from us. We had many pleasures and

advantages. There was no dullness or gloom about our

home, and everything seemed to give occasion for mirth.

We had many trips abroad too, indeed, we spent most winters

on the Continent. I made an excursion with a brother

who was an ecclesiastical architect, and in this way I

visited every cathedral in France. Heidelberg is very

picturesque, and suggested many poetical ideas, but all

travelling enlarges one's mind and is an education."

Jean Ingelow, from . . .

Notable Women

Authors of the Day, by Helen C. Black (1906). |

――――♦――――

|

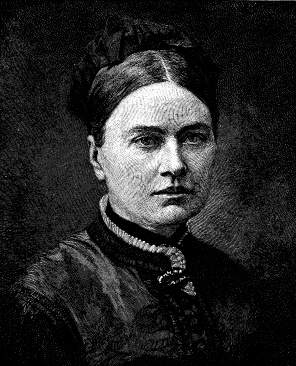

|

|

Photo by Barrauds.

|

"Against her ankles as she trod

The lucky buttercups did nod.

I leaned upon the gate to see:

The sweet thing looked, but did not speak;

A dimple came in either cheek,

And all my heart was gone from me."

|

Reflections |

In his review of Jean

Ingelow's Poems for the Athenæum,

Gerald Massey aptly described her ballad

"The High Tide on the Coast of

Lincolnshire (1571)" thus: ". . . . a poem full of power and

tenderness. The story is related by an old mother, whose son's

wife and babes were drowned. It is done with such a sweet,

Quakerly precision of manner, and such subtle touches of unconscious

self-portraiture, that the old lady lives before us"; indeed, the

heart-felt recounting of her tragic tale, worded in the style of her

time, is among the very best of Jean Ingelow's output and is poetry of a

high order. [See also Lafcadio Hearn on

High Tide.]

Massey's review is generally acknowledged to have launched

both Jean's literary career and, through its success, that of the

Massachusetts publishing house of Roberts Brothers. To establish some control of copyright in the American market, Massey

suggested to Jean that she contact his American publisher, Ticknor and

Fields. This she did, but for some unknown reason Poems went

to Roberts Brothers—also of Boston, Massachusetts—who were later to

publish others of Jean Ingelow's titles in great numbers.

Jean's first poetry collection was followed in 1867 by

A Story of

Doom and other Poems, in which the long

principal poem recounts the days immediately preceding Noah's

flood, concluding on the eve of the deluge—

|

And Niloiya said,

'My sons, if one of you will hear my words,

Go now, look out, and tell me of the day,

How fares it?'

And the fateful darkness grew.

But Shem went up to do his mother's will;

And all was one as though the frighted earth

Quivered and fell a-trembling; then they hid

Their faces every one, till he returned,

And spake not. 'Nay,' they cried, 'what hast thou seen?

Oh, is it come to this?' He answered them,

'The door is shut.' |

. . . . and the Ark is soon afloat.

Dragon, serpent, demons and

Satan feature among the cast, while in the romantic subplot appears a handsome

prince, who having eventually overcome his reservations on crossing

the social divide, marries a beautiful slave girl—

|

And now thyself

Art loveliest in mine eyes; I look, and lo!

Thou art of beauty more than any thought

I had concerning thee. Let, then, this robe,

Wrought on with imagery of fruitful bough,

And graceful leaf, and birds with tender eyes,

Cover the ripples of thy tawny hair.'

So when she held her peace, he brought her nigh

To hear the speech of wedlock; ay, he took

The golden cup of wine to drink with her,

And laid the sheaf upon her arms. He said,

'Like as my fathers in the older days

Led home the daughters whom they chose, do I;

Like as they said, "Mine honour have I set

Upon thy head!" do I. Eat of my bread,

Rule in my house, be mistress of my slaves,

And mother of my children.' |

|

15A,

HOLLAND STREET,

KENSINGTON.

DEAR MISS FYVIE,

"I have just received your note and the little tale called 'Janet

Campbell.' You asked to have it noticed on the cover of the

magazine, but as I could only mention it there, I prefer to write to

you privately.

"At your early age, my dear, it is better that you should be

cultivating your own mind than that you should attempt to interest

and amuse others. You are not able at present to write from your own

observation, but must

draw your characters and scenes from books. This is not good for

you, and if you ever wish to write really well, you must wait till

you have made your own observations on human nature. I think your

tale very much

better than most girls of your age would have written, but I do not

consider it worthy of a place in the magazine (which I only began

this month to edit), but I feel interested in your account of

yourself. If you like to write

to me, and tell me what is your condition in life, whether you are

at school, and what you are doing to improve yourself, I should be

happy to answer your letter, and if I can give you any advice, shall

be glad to do so.

"I would not advise you to write any more till you are sixteen, and

in the meantime I would take particular notice how books and papers

which interest you are written. Say to yourself when you read of

children: 'Do the

children that I know talk in this way, or act in this way?' If they

do, then consider the book well written. If they do not, then notice

in what the difference consists. You should do the same in reference

to grown-up

people, though the most useful studies for you are girls of your own

age, because you can understand their motives best.

"You are at present not mistress of your own language. In your nice

little note to me you say: 'It is MORE the wish of learning your

opinion concerning it rather than the hope of its being inserted,'

etc. You must not use

more than one of these words; the other is superfluous. Again, in

the tale you say: 'I do not dare do what is wrong,' 'You must be

made reveal your secret.' 'I do not dare to do what is wrong,' 'You

must be made to

reveal your secret,' would be more correct; or, better still, 'I

dare not do what is wrong.'

"And now I have not time to write more. I give you my address and

name, and if you like you can write to me.

"I am,

Yours sincerely,

JEAN INGELOW.

3 January, 1857

―――♦―――

From

Recollections of

Fifty Years, by

Isabella Fyvie Mayo. |

Monitions of the Unseen, and Poems of Love and

Childhood appeared in 1870. One critic,

perhaps suffering a surfeit of Coleridge,

while recognising that the poems in the collection were highly

individual, detected in them "dreamful quiet, of folding of the hands to

sleep, as if they had been inspired of poppy rather than of Hippocrene."

Another, while saying of the principal poem that "We have read nothing

from her pen which we like better", went on to conclude that "It may be

a question with some readers whether Jean Ingelow’s poems repay study.

They certainly require it." Yes, true—sometimes

. . . .

|

'A lame black beetle preaching like a fish;

A squinting planet in a gravy-dish;

Amorphous masses cooing to a monk;

Two fine old crusty problems, very drunk;

A pert parabola flirting with the Don;

And two Greek two Greek grammars, with on.'

'Off the Skelligs',

chpt. XX. |

Amorphous masses cooing to a monk? . . . but

then again much of Miss Ingelow's verse speaks quite

plainly. Take for example this delightful sonnet,

topical in our age in which there is much concern for the well-being of our natural

environment . . . .

|

ON THE BORDERS OF CANNOCK CHASE.

A COTTAGER leaned

whispering by her hives,

Telling the bees some news, as they lit down,

And entered one by one their waxen town.

Larks passioning hung o'er their brooding wives,

And all the sunny hills where heather thrives

Lay satisfied with peace. A stately crown

Of trees enringed the upper headland brown,

And reedy pools, wherein the moor-hen dives,

Glittered and gleamed.

A resting-place for light,

They that were bred here love it; but they say,

"We shall not have it long; in three years' time

A hundred pits will cast out fires by night,

Down yon still glen their smoke shall trail its way,

And the white ash lie thick in lieu of rime."

From . . . .Monitions

of the Unseen,

and Poems of Love and Childhood. |

In 1878, Jean's UK publisher, Longmans, Green & Co.,

brought out, unattributed, One

Hundred Holy Songs, Carols, and Sacred Ballads: Original, and Suitable

for Music. I find it curious that a collection of

verse by an established poet—and, as such, likely to sell well—should be published

in this way. Here one might speculate

that this was, perhaps, an early work that Longmans considered good enough to bring to market,

but not to attribute to their distinguished client. But if so, one

wonders whether the proud, principled and solvent Miss Ingelow would

have been content to disown her published verse or its inherent

religious beliefs? While I feel uneasy about attribution, the

poems are listed in COPAC

(not infallible) and other sources

among Jean Ingelow's output, and some do find their way into "Poems by

Jean Ingelow; Author's Complete Edition" published in 1896 by

Jean's American publisher, Roberts Brothers of Boston.

Regardless of speculation, contemporary reviewers

gave this anonymous collection their qualified

blessing. This from the Graphic . . . .

|

The author of 'One Hundred Holy Songs,

Carols and Sacred Ballads,' original, and suitable for music

(Longmans), has evident fervour, and a good deal of sound

taste, joined to mechanical skill. Strictly speaking, there

is not a carol nor a ballad in the book; the nearest

approach to the latter is 'When Children are Sick,' and the

next best is 'Service.' But perhaps the most successful

essay, amongst many which are pleasing, is 'All in the city

whose gates are gold,' although it should be 'streets' for

strict accuracy.

Graphic, 31 Aug., 1878 |

In the view of the Pall Mall Gazette (2nd Sept., 1878) the poems

"are very unequal in quality. In some taste, grammar, and rhythm

are lacking; but in others — not many

perhaps, in number — the author rises

to a level of our good Hymn writers." And the Gazette's

verdict? "The modest-looking little volume is one that the

compilers of hymn-books . . . cannot afford to neglect." This from

"One Hundred Holy Songs" (with a particularly attractive opening

stanza) . . . .

|

Thick Orchards All In White

"The time of the singing of birds is

come."

Thick orchards, all in white,

Stand 'neath blue voids of light,

And birds among the branches blithely sing,

For they have all they know;

There is no more, but so,

All perfectness of living, fair delight of spring.

Only the cushat dove

Makes answer as for love

To the deep yearning of man's yearning breast;

And mourneth, to his thought,

As in her notes were wrought

Fulfill'd in her sweet having, sense of his

unrest.

Not with possession, not

With fairest earthly lot,

Cometh the peace assured, his spirit's quest;

With much it looks before,

With most it yearns for more;

And 'this is not our rest,' and 'this is not

our rest.'

Give Thou us more. We

look

For more. The heart that

took

All spring-time for itself were empty still;

Its yearning is not spent

Nor silenced in content,

Till He that all things filleth doth it sweetly fill.

Give us Thyself. The May

Dureth so short a day;

Youth and the spring are over all too soon;

Content us while they last,

Console us for them past,

Thou with whom bides for ever life, and love,

and noon. |

(The unusual abbreviation "'dureth" in the final stanza also appears in "Afternoon

at a Parsonage" — O perfect love

that 'dureth long!)

Jean's muse departed public view for some years to return in 1885 with her

final

collection. But Poems of the Old Days and the New (published

in the U.K. as Poems by Jean Ingelow, Third Series) was even

less well received

than its predecessor, for her popularity as a poet was now in decline,

overshadowed by younger talents with new ideas. Thus the New York

Times (16 August, 1885) "Those who enjoyed the first offerings of

Jean Ingelow will do well to reserve their judgement if the present

volume appears to lack the originality and grace that they once admired":

or, as Jean Ingelow the novelist put it,. . . .

|

"Oh, what a curious place the world is,

and what a number of things are found out afresh in it! What

faded old facts stand forth in startling colours, as wonderful and

new, when youthful genius gets a chance of sitting still while it

passes, and making unnoticed studies of it."

From . . . .

Sarah De Berenger. |

Nonetheless, when Tennyson—himself an admirer of Jean's verse—died

in 1892, a group of Americans petitioned Queen Victoria to appoint Jean

Ingelow the first woman Poet Laureate. In the opinion of Christina Rossetti,

whose name was also linked to

the vacant laureateship, Jean Ingelow

"would be a formidable rival to most men, and to any woman," a

sentiment echoed by Gerald Massey in his review of

Poems for the Athenæum (1863), that "some

of the poetry has the strength of man's heart, the sweetness of woman's

mouth;" but Alfred Austin got the job—no

doubt to the relief of the Misses Ingelow and Rosetti—thought by some to

have been based more on political influence than poetic merit.

It was to be over a century before a woman (and also the first Scot),

Carol Ann Duffy, acquired

the (dubious) distinction of becoming the Laureate.

|

"I went out at five o'clock this morning,

before the dew was off, and walked to the edge of my friend

F.'s spinney to delight myself with the sight of a delicate

reach of wood-mellick, a grass of surpassing beauty.

There was no wind. The air only just moved enough to

make it tremble slightly, as if some ecstasy had overtaken

it and was moving it to part with a diamond drop here and

there from its purple panicles to the lush green of its

leaves. It was all shot in and out with sunshine, and

had an effect as of a bloom hanging over low green leaves

which stood up swordlike and still; or rather as of a mirage

or a mist, adorned here and there with butterflies newly

waked. I could have gazed on it longer, but the wild

hemlock, growing breast-high and crowned with a milky-way of

flowers, tempted me farther on."

A picture of early morning, from . . . John

Jerome. |

A number of Jean's poems were set to music by among

others, Sir Arthur Sullivan, and as

songs they became popular

Victorian/Edwardian salon pieces in an age when home music-making was

much more common than today ― indeed,

Schirmers were still publishing song setting of Jean's verse into the

1920s. When

Sparrows Build seems to have been particularly popular and no doubt its

royalties, with those from the others, contributed to her "pleasant

bounty". Some examples of song settings of

Jean's verse are available to download

under Sheet Music (I. &

II.).

In addition to her poetry, Jean published a handful of novels. Off the Skelligs

was published in 1872 (vide résumé

and review) followed in 1873 by Fated to be Free

, a sequel that spans the earlier story chronologically (vide résumé

and review). Judging from the comparatively large number of copies

that remain available on the

antiquarian book market, both books were very popular, especially in

America. They are not, however, up to the standard of Jean's next

two novels,

Sarah de Berenger and

Don John. In

Skelligs, the fire at sea and the rescue are particularly well

done but extended passages of dialogue elsewhere can prove dull, while

some of Jean's characters are

unconvincing; that of Valentine, particularly as he appears in the

sequel (Fated to be Free) is especially so (and would the eminently sensible Miss Graham

really consent to marry a consumptive nincompoop such as he?)

|

"Some people appear to feel that they are much wiser,

much nearer to the truth and to realities than they were when they

were children. They think of childhood as immeasurably beneath

and behind them. I have never been able to join in such a

notion. It often seems to me that we lose quite as much as we

gain by our lengthened sojourn here. I should not at all

wonder if the thoughts of our childhood, when we look back on it

after the rending of this vail of our humanity, should prove less

unlike what we were intended to derive from the teaching of life,

nature, and revelation, than the thoughts of our more sophisticated

days."

From...Off

the Skelligs. |

Sarah de Berenger, which

appeared in 1879 is a more convincing tale than the previous two.

A more tightly constructed and faster moving

story, the outcomes of Sarah de Berenger's

scheming, while forming an essential role

in the development of the ingenious plot,

play second fiddle to the trials of its long-suffering, stalwart, taciturn

heroine, Hannah Dill, who might more appropriately have lent her

name to the novel (vide

résumé

and review).

|

"Up and down the long hills they moved till the

crescent moon rose, and then till it grew dark and the great

horn-lantern was lighted, and the old man carried it, sometimes flashing

its light on his horse, sometimes on the green hedges, and into fields,

whose crops they could guess only by the smell of clover, or fresh-cut

hay, or beans that loaded the warm night air; anon, on whitewashed

cottages, whose inhabitants had long been asleep, and again upon the

faces of great cliff-like rocks, where cuttings had been made for the

road into the steep hills, and where strange curly ammonites and peaked

shells and ancient bones high up showed themselves for an instant in the

moving disk of light that rose and sank as the lantern swayed in the

carrier’s hand."

A night-time journey, from . . . .

Sarah De Berenger. |

Don John:

a story (1881 ―

résumé & review) and

John Jerome (1886

― résumé

& review) followed. In Don John (Donald Johnstone), the

author exploits in an equally ingenious manner a theme similar to its

predecessor, Sarah de Berenger, that being a puzzle concerning the true parentage of

children. The story ends with a twist, although an imaginative

reader might suspect the outcome as the plot later develops. But

John Jerome is nothing like its

predecessors, and at the outset requires perseverance, for in the

first four chapters of the book it seems as if the author is setting

down on paper her private musings ―

indeed, ramblings; it is almost as if Jean's

'Rossettians' had suddenly taken to painting in the style of

Picasso. There is no clue or hint as to what the story

― if indeed there is to be one

― might concern, or where it might

lead. As the New York Times reviewer put it, "Precise

readers, accustomed to the cut and dried ways of romance, may not

appreciate the introduction to 'John Jerome,' for it is rather

intangible at best and uncertain." But at Chapter V., a

more

conventional Miss Ingelow returns and

to further quote the NYT reviewer,

"Miss Ingelow's book, when you have done a little

plodding at the beginning, opens up briskly and pleasantly, and the

jaunt through the story is a delightful one." Those

interested in women's rights might find Jean's views on the subject (Chapter VII)

enlightening.

|

"O woman,

woman! you are in this transgression. I am sick of

hearing of Woman's Rights, while her faults are so many and

her foolishness is so great. Your star is already in the ascendant, and man is a

minority. How long will it be before you take heart and perceive

that, if you would but combine, nothing in the world could be done

'without the leave of you'"?

On women's rights, from . . . .

John Jerome, c. vii. |

Jean Ingelow's last novel,

A Motto

Changed (1893), appears only to have been published in the

United States, where it met with cool

reviews.

|

"A man's world, but woman bides her time.

'The mills of God grind slowly, but they grind exceeding

small.' As a man, I have my forebodings. I think

we shall catch it soon, when they find out, when they

combine and put us into our original places again, — when,

in short, their Maker turns again their captivity, and

removes the veil which hangs before their eyes . . . . It

may be partly on this account that I never omit a chance of

being obliging and helpful to a woman . . . . I hope this

will be remembered in my favour when her time comes."

On women's rights, from . . .

John Jerome, c.

vii. |

Among Jean's children's stories are

Studies for

Stories (1864—also illustrated by Millais),

Stories told to a Child (1865),

A Sister's Bye-Hours (1868), the

delightful and ever popular Mopsa

the Fairy (1869—and still in print) and The Little Wonder-horn

(1877), five of its fourteen stories later being published as

Wonder-Box Tales.

|

. . . .

About that time I had it in my power to make a slight return to Jean

Ingelow for the trouble she had bestowed on me. She had been a

celebrated woman for some time, and I told Mr. [Alexander] Strahan of some short

stories of

hers, which he at once desired to reprint. But she had kept no

copies, either in print or in manuscript. I persuaded my mother to

make a sacrifice of seven of her treasured volumes of the Youth's

Magazine. From them

were reprinted most, if not all, of the "Studies for Stories" and

"Stories told to a Child."

From

Recollections of

Fifty Years, by

Isabella Fyvie Mayo. |

The long narrative poem Gladys

and Her Island might also be considered a children's story

in verse ― the author describes it as a fable,

its final section being The

Moral ― for on the

surface it

exhibits much the character of a fantasy-adventure from a 'Girl's

Own Paper' of the period. In it, Gladys, having been granted the

exceptional boon of a day's holiday, sails to an unreal island world in

which she explores such exotic locations as the Garden of Eden and the

ruins of ancient Egypt. But the tale has no happy ending, for

Gladys must eventually return from her island of dreams to the real

world and to her lowly role as an unloved teaching assistant . . . .

"Who wind the robes of ideality

About the bareness of their lives, and hang

Comforting curtains, knit of fancy's yarn,

Nightly betwixt them and the frosty world." |

The biting social commentary that underpins Gladys must have given

contemporary readers pause for thought.

Isa Craig's The Schoolmistress

(from Good Words, 1878)

paints a similar picture.

――――♦――――

"It is not reason which makes faith

hard, but life."

Jean Ingelow spent her later life

at No. 6 Holland

Villas Road. . . .

|

". . . . in Kensington, a suburb of London, in a

two-story-and-a-half stone house, cream-colored, . . . . .

Tasteful grounds are in front of the home, and in the rear a large

lawn bordered with many flowers, and conservatories; a real English

garden, soft as velvet, and fragrant as new-mown hay. The

house is fit for a poet; roomy, cheerful, and filled with flowers.

One end of the large, double parlors seemed a bank of azalias and

honeysuckles, while great bunches of yellow primrose and blue

forget-me-not were on the tables and in the bay-windows."

From. . . .Lives of

Girls Who became Famous.

"Jean Ingelow thinks that women are entitled to either rights or

privileges and usually have one at the expense of the other.

For herself she has decided to waive the rights and cling to the

privileges."

Deseret News (Utah, U.S.A.), 18 March 1893.

PERSONAL MENTION

Two illustrious women who celebrate this year the

seventy-fifth anniversary of their birth are Florence Nightingale

and Jean Ingelow.

Salt Lake Tribune (U.S.A.), 13 June, 1895. |

JEAN INGELOW'S HOME.

But a few moment's ride from London is the Kensington

home of Jean Ingelow, whose poetry is so familiar to American

readers. This house is an old one, of cream colored stone, and

one scarcely knows whether it has two or three stories.

Liberal grounds surround the house, and even in Winter show a

gardener's care. In Summer the entire lawn is bordered and

dotted with flowers, for the poet is a pronounced horticulturalist.

Jean Ingelow's home is that of a poet, with books on every hand and

always within reach wherever you may chance to sit down. The

poet is now in middle life, but her face shows not the slightest

traces of years. Her manner is most friendly, her conversation

charming and she has a very musical voice. She enjoys a

remarkably correct knowledge of American literature, and titles of

all the latest American books being spoken by her with wonderful

fluency. Her character is eminently practical, without a touch

of sentimentality. All her literary writing is done in the

forenoon; her pen is never put to paper by gaslight. She

composes slowly, and her verses are often kept by her for a few

months before they are allowed to go out for publication. She

shuns society, and the most severe part of the winter is spent in

the south of France.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (U.S.A.), May 30, 1889. |

|

|

|

|

Jean Ingelow's home. |

"I have lived to thank God that

all my

prayers have not been

answered." |

|

. . . ."A few

words must be said in description of the pretty house in

Kensington where Miss Ingelow lives with her brother, and

into which, some thirteen years ago, they removed from Upper

Kensington to be further out and away from so much building.

Since this removal she says, "three cities have sprung up

around them!"

"The handsome square detached house

stands back in a fine, broad road, with carriage drive and

garden in front filled with shrubs, and half a dozen

chestnut and almond trees, which in this bright spring

weather are bursting out into leaf and flower. Broad stone

steps lead up to the hall door, which is in the middle of

the house.

"The entrance hall where hangs a portrait of the

author's maternal great-grandfather, the Primus of Scotland,

i.e., Bishop of Aberdeen opens into a spacious,

old-fashioned drawing-room of Italian style on the right. Large and lofty is this bright, cheerful room. A harp, on

which Miss Ingelow and her mother before her played right

well, stands in one corner. There is a grand pianoforte

opposite, for she was a good musician, and had a remarkably

fine voice in earlier years. On the round table in the deep

bay windows in front are many books, various specimens of

Tangiers pottery, and some tall plants of arum lilies in

flower.

"The great glass doors draped with curtains at the

further end, open into a large conservatory where Miss

Ingelow often sits in summer. It is laid down with matting

and rugs, and standing here and there are flowering plants

and two fine araucarias. The verandah steps on the left lead

into a large and well-kept garden with bright green lawn, at

the end of which through the trees may be discerned a large

stretch of green-houses, and a view beyond of the great

trees in the grounds of Holland Park.

"On the corresponding

side of the house at the back is the billiard-room, which is

Mr. Ingelow's study, leading into an ante-room, and in the

front is the dining-room, where the author's literary

labours are carried on. "I write in a common-place, prosaic

manner," she says; "I am afraid I am rather idle, for I only

work during two or three of the morning hours, with my

papers spread all about the table." Over the fireplace hangs

a painting on ivory of her father, and above it a portrait

of her mother, taken in her early married life. This

portrait, together with one of the poet herself when an

infant, is in pastels, and they were originally done as door

panels for her father's room; the colouring is yet unfaded."

From . . . "Notable Women

Authors of the Day", by Helen C. Black (1906) |

Holland Villas Road remains a smart area of

West London, its high Victorian residences well maintained and

mostly unspoiled by modern architectural tampering; and looking at her former

home, one cannot avoid the impression that Miss Ingelow prospered on the

products of her pen. But the

neighbourhood has changed. It's now a part of London's embassy belt,

and armed officers of the Diplomatic Protection Group loiter, their

distinctive red vehicles adding a hint of menace to the neighbourhood's

tranquillity.

There's no English Heritage "blue plaque" to

commemorate Jean's achievement among the poets and authors of her era,

but maybe that's as well, for as

Betjeman put it . . . "approval

of what is approved of . . . "

|

". . . . What think you of Jean

Ingelow, the wonderful poet? I have not yet read the

volume, but reviews with copious extracts have made me aware

of a new eminent name having arisen among us. I want

to know who she is, what she is like, where she lives.

All I have heard is an uncertain rumour that she is aged

twenty-one, and is one of three sisters resident with their

mother. A proud mother, I should think."

Christina Rossetti to Dora Greenwell, 31 Dec.

1863.

". . . . My acquaintance with Jean

Ingelow's poems to which you kindly introduced me, has been

followed by a very slight acquaintance with herself She

appears as unaffected as her verses, though not their equal

in regular beauty: however I fancy hers is one of those

variable faces in which the variety is not the least charm.'

Christina Rossetti to Anne Gilchrist, 1864.

". . . . I have lugged down with me a

six-volume Plato, and this promises me a prolonged mental

feast. Jean Ingelow's 8th edition is also here, to

impart to my complexion a becoming green tinge."

Christina to Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

Hastings, 23 Dec. 1864. |

Among the many writers that Jean knew were Tennyson (who remarked, "Miss

Ingelow, I do declare you do the trick better than I do"), Browning (to

whom, for a period following the death of his wife, it was rumoured

that she was romantically attached),

Massey (rumoured to have proposed marriage to her), Longfellow, Christina Rossetti, Adelaide Procter and Dora

Greenwell (see

letters).

She also knew the composer Virginia Gabriel ―

see Miss Gabriel's setting of

When sparrows build

the leaves break forth

(also, of Adelaide Procter's

Cleansing

fires). John Ruskin became a close

friend . . .

|

"Mr. Ruskin presently came up to me,

and entered into a charming conversation. He gathered

some of the flowers and gave them to me

― I kept them for a long

time ― then we walked round

a meadow close at hand which was just fit for the scythe,

and afterwards he took me to see a number of the curiosities

that he had collected. We soon became loving friends

and his friendship has been one of the great pleasures of my

life."

From . . .

Notable Women

Authors of the Day, by Helen C. Black (1906). |

Jean's political and religious

views were conservative, as is illustrated both in her writing and by

this contemporary account . . . .

|

". . . .

Later I heard that Miss Ingelow was extremely conservative, and was

very indignant when a petition for women's rights to vote was

offered for her signature. A rampant Radical told me this, and

shook her handsome head pathetically over Jean's narrowness; but

when I heard that once a week several poor souls dined comfortably

in the pleasant home of the poetess, I forgave her conservatism, and

regretted that an unconquerable aversion to dinner parties made me

decline her invitation."

From . . . .Jean

Ingelow, the Poetess. |

She was generous, routinely spending part of her royalties to

entertain at her home poor people identified by the local clergy to what she described

as her "copyright dinners" . . . .

|

". . . . I have set up a dinner-table for the sick poor, or

rather, for such persons as are just out of the hospitals, and are

hungry, and yet not strong enough to work. We have about

twelve to dinner three times a week, and hope to continue the plan.

It is such a comfort to see the good it does. I find it one of

the great pleasures of writing, that it gives me more command of

money for such purposes than falls to the lot of most women."

From. . . .Lives of

Girls Who became Famous. |

Jean Ingelow never married, but she is known to have

received at least one proposal, while for a number of years her name

was linked to that of the poet Robert Browning. In her

autobiography Recollections of Fifty Years,

Isabella Fyvie Mayo

tells us

that:

". . . .not even all Jean Ingelow's dignity and reserve

could save her from intrusive gossip. Some may remember that once it

was freely whispered that she was likely to become the second wife of

Robert Browning. There were absolutely no grounds for this rumour,

which, if it reached her, doubtless gave her pain, and is conceivably the

reason why, as her biographer puts it, 'the acquaintance between the two

poets never ripened into intimacy.' While the rumour was current

Mrs. S. C. Hall told me that Gerald Massey, who had felt as much

admiration for the poet as for her poems, had offered her his hand, he

being then a widower with a young family. He confided to Mrs. Hall

that Jean Ingelow had replied most kindly, but had assured him that her

acceptance of his offer was 'quite impossible.' 'Now nothing could

make my offer impossible,' said he naïvely,

'save the existence of an already-accepted lover. Who is visiting

the Ingelows' house just now? Why, Robert Browning has been seen

here! It must be he.' And so the rumour rose―an

inference transformed into an assertion."

In her biography of Jean Ingelow (Jean Ingelow, Victorian Poetess

― Rowan and Littlefield, 1972), Maureen Peters

refers to the 'Browning rumour' thus. . . .

"From time to time her name was linked

with various gentlemen, but the most persistent of the rumours concerned

her 'romance' with Robert Browning.

"Jean met the widowed poet in 1867 at a musical party

given by Virginia Gabriel. . . . Jean had evidently taken a liking to

Robert Browning, in which sentiment she was not alone. Most ladies

found a great deal to admire in the dapper little man with the beautiful

eyes. . . .A few days after that meeting with Robert Browning, Jean sent

him a copy of A Story of Doom.

"Four years later, Robert Browning was still denying .

. . . that there was any romance between Jean and himself―'I

never saw Miss Ingelow but once, at least four years ago, at a musical

party, where I said half a dozen words to her: only heard of her, as I

told you, by her writing a note to accompany her new book, a day or two

before I left London.' . . . . The persistence of the rumour does

suggest that a closer friendship existed between the two than he was

willing to admit."

So perhaps Massey was not wide of the mark in his

(albeit conceited)

deduction.

The 'Browning rumour' apart, some commentators speculate on

the existence of a personal tragedy in Jean's life, this being suggested by a theme prominent

in much of her poetry, that of loved ones lost at sea. But an

alternative and, perhaps, more plausible explanation for this recurring theme

of death at sea is put forward by Jennette Attwater Street in her

appraisal written shortly after

Jean Ingelow's death: "Her nurse was a sailor's widow, and as she talked

constantly in the children's presence of storms and wrecks, their

earliest sense of tragedy came to be connected with the sea." For

example, from When

Sparrows Build we have . . . .

O my lost love, and my own, own love,

And my love that loved me so!

Is there never a chink in the world above

Where they listen for words from below?

Nay, I spoke once, and I grieved thee sore,

I remember all that I said,

And now thou wilt hear me no more—no more

Till the sea gives up her dead. . . . . |

a poem that appears to have been a popular subject for the salon

composers of the age (see song

settings by Maria Lindsay and Virginia Gabriel). And other

references to death at sea include. . . .

|

. . . . the "Grace of Sunderland" was wrecked. . . .

And ne'er a one was saved.

They're lying now,

With two small children, in a row; the church

And yard are full of seamen's graves, and few

Have any names. . . .

From. . . 'Brothers and a Sermon'

_______________

. . . . and one could not hear

A word the other said for wind and sea

That raged and beat and thundered in the night—

The awfullest, the longest, lightest night

That ever parents had to spend. A moon

That shone like daylight on the breaking wave.

Ah, me! and other men have lost their lads,

And other women wiped their poor dead mouths,

And got them home and dried them in the house,

And seen the drift-wood lie along the coast,

That was a tidy boat but one day back, . . . .

From. . . 'Brothers and a Sermon' |

She drave at the rock with sternsails set

Crash went the masts in twain;

She staggered back with her mortal blow,

Then leaped at it again.

There rose a great cry, bitter and strong,

The misty moon looked out!

And the water swarmed with seamen's heads,

And the wreck was strewed about.

I saw her mainsail lash the sea

As I clung to the rock alone;

Then she heeled over, and down she went,

And sank like any stone.

From. . . 'Winstanley'

_______________

. . . . My boat, you shall find none fairer afloat,

In river or port.

Long I looked out for the lad she bore,

On the open desolate sea,

And I think he sailed to the heavenly shore,

For he came not back to me—Ah me! . . . .

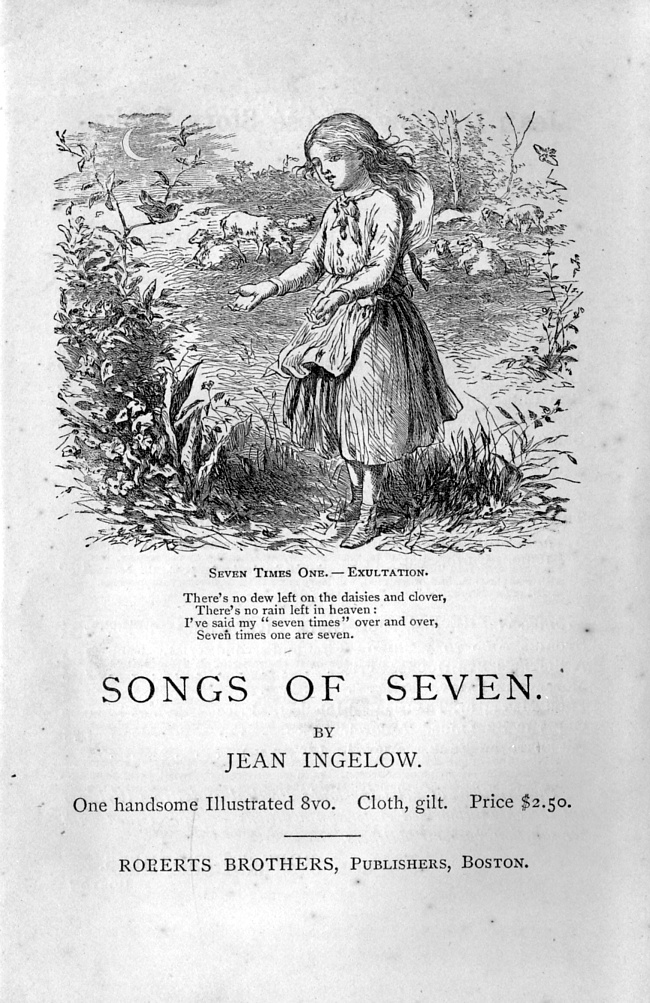

From. . . .'Songs of

Seven' |

. . . . and a more substantial extract. . . .

|

|

The wrecking of the Grace of Sunderland

. . . .

An old fisherman recounts the story of the parson.

. . .

" . . . . when he was a younger man

He went out in the lifeboat very oft,

Before the "Grace of Sunderland" was wrecked.

He's never been his own man since that hour;

For there were thirty men aboard of her,

Anigh as close as you are now to me,

And ne'er a one was saved.

They're lying now,

With two small children, in a row: the church

And yard are full of seamen's graves, and few

Have any names.

She bumped upon the reef;

Our parson, my young son, and several more

Were lashed together with a two-inch rope,

And crept along to her; their mates ashore

Ready to haul them in. The gale was high,

The sea was all a boiling seething froth,

And God Almighty's guns were going off,

And the land trembled.

When she took the ground,

She went to pieces like a lock of hay

Tossed from a pitchfork. Ere it came to that,

The captain reeled on deck with two small things,

One in each arm—his little lad and lass,

Their hair was long, and blew before his face,

Or else we thought he had been saved; he fell,

But held them fast. The crew, poor luckless souls.

The breakers licked them off; and some were crushed,

Some swallowed in the yeast, some flung up dead,

The dear breath beaten out of them: not one

Jumped from the wreck upon the reef to catch

The hands that strained to reach, but tumbled back

With eyes wide open. But the captain lay

And clung—the only man alive. They prayed

"For God's sake, captain, throw the children here!"

"Throw them!" our parson cried; and then she struck:

And he threw one, a pretty two-years child;

But the gale dashed him on the slippery verge,

And down he went. They say they heard him cry.

'Then he rose up and took the other one,

And all our men reached out their hungry arms,

And cried out, "Throw her, throw her!" and he did;

He threw her right against, the parson's breast,

And all at once a sea broke over them,

And they that saw it from the shore have said

It struck the wreck and piecemeal scattered it,

Just as a woman might the lump of salt

That 'twixt her hands into the kneading-pan

She breaks and crumbles on her rising bread.

'We hauled our men in: two of them were dead—

The sea had beaten them, their heads hung down;

Our parson's arms were empty, for the wave

Had torn away the pretty, pretty lamb;

We often see him stand beside her grave:

But 't was no fault of his, no fault of his. . . ."

From. . . 'Brothers and a Sermon' |

And Jean's muse often captures more relaxing

maritime scenes in both verse and in prose. The following is probably based on Jean's childhood

recollections of coastal trading

vessels being hauled manually, by a gang of 'towers', upriver to a

jetty—

|

THE DAYS WITHOUT ALLOY.

"When I sit on market-days amid the comers and the

goers,

Oh! full oft I have a vision of the days without alloy,

And a ship comes up the river with a jolly gang of towers,

And a 'pull'e haul'e, pull'e haul'e, yoy! heave, hoy!'

"There is busy talk around me, all about mine ears it hummeth,

But the wooden wharves I look on, and a dancing, heaving buoy,

For 'tis tidetime in the river, and she cometh—oh, she cometh !

With a 'pull'e haul'e, pull'e haul'e, yoy! heave, hoy!'

"Then I hear the water washing, never golden waves were brighter,

And I hear the capstan creaking—'tis a sound that cannot cloy.

Bring her to, to ship her lading, brig or schooner, sloop or lighter,

With a 'pull'e haul'e, pull'e haul'e, yoy! heave, hoy!'

"'Will ye step aboard, my dearest? for the high seas lie before us.'

So I sailed adown the river in those days without alloy.

We are launched! But when, I wonder, shall a sweeter sound

float o'er us

Than yon 'pull'e haul'e, pull'e haul'e, yoy! heave hoy!'"

From . . . .Monitions

of the Unseen, and Poems of Love and Childhood. |

― and from

The First Watch, the

second poem from the cycle Songs of

the Night Watches . . . .

|

Rock, and rock, and rock,

Over the falling, rising watery world,

Sail, beautiful ship, along the leaping main;

The chirping land-birds follow flock on flock

To light on a warmer plain.

White as weaned lambs the little wavelets curled,

Fall over in harmless play,

As these do far away;

Sail, bird of doom, along the shimmering sea,

All under thy broad wings that overshadow thee. |

― and some other evocative seaside cameos

in prose—

|

". . . . It was a still, warm day. A

great bulging cloud, black and low, was riding slowly up from the

south. The cliffs had gone into the brooding darkness of this

cloud, which had stooped to take them in. The water was

spotted with flights of thistledown, floated from the meadows behind

the church, and riding out to sea. Suddenly a hole was blown

in the advancing and lowering cloud; the sun glared through it, and

all the water where his light fell was green as grass, and the black

hulls of the crowded vessels glittered; while under the cliff a long

reach of peaked red roofs looked warmer and more homelike than ever,

and on the top of them the wide old church seemed to crouch, like a

great sea-beast at rest, and the ruined abbey, well up on the hill,

stood gaunt and pale, like the skeleton ribs and arms of a dead

thing in sore need of burial."

The harbour at Whitby, from. . . .

Sarah De Berenger |

|

" . . . . a thin mist would be hanging

across the entrance of the bay, like a curtain drawn from

cliff to cliff; presently this snowy curtain would turn of

an amber colour, and glow towards the centre; once I

wondered if that sudden glow could be a ship on fire, and

watched it in fear, but I soon saw the gigantic sun thrust

himself up, so near, as it seemed, that the farthest cliffs

as they melted into the mist appeared farther off than he—so

near, that it was surprising to count the number of little

fishing-boats that crossed between me and his great disc;

still more surprising to watch how fast he receded, growing

so refulgent that he dazzled my eyes, while the mist began

to waver up and down, curl itself, and roll away to sea,

till on a sudden up sprang a little breeze, and the water,

which had been white, streaked here and there with a line of

yellow, was blue almost before I could mark the change . . .

."

'The Lonely Rock', from . . . .

Stories Told to a Child. |

――――♦――――

|

THE TIMES

July 21, 1897.

―――♦―――

JEAN INGELOW.

Miss Jean Ingelow, who died yesterday at her residence in

Kensington, at the age of 77, was one of those writers who, without

being among the greatest of their age, yet appeal strongly to the

taste of the public of their day and win for their works a large, if

not a lasting, meed of popularity. One may hazard a guess that

Miss Ingelow's poems and stories are not much read by the younger

generation of today, whose taste lies in the direction of more

strenuous talent; but in the sixties and seventies her volumes were

sold in enormous numbers both in this country and in the United

States. One of them at least has gone through more than 20

editions, and the others were bought up in thousands and must have

bought in down to a fairly recent date a large income for books of

verse.

Miss Ingelow came, like Tennyson, of a Lincolnshire family, and the

poetry of the great Poet Laureate had a considerable influence on

hers. Her stories in blank verse—"Laurance," "Brothers and a

Sermon," and "Gladys and her Island" for instance—had a strong

Tennysonian ring, and the dainty sketches, "Supper at the Mill" and

"Afternoon at a Parsonage" might almost have been the early efforts

of the Laureate himself, though in the lyrics Miss Ingelow scarcely

succeeded so well in her blank verse, which was smooth and graceful

and only lacked higher qualities in being too obvious an echo of a

greater style. The poems by which she is, perhaps, best known

is one connected with her native county—"High Tide on the Coast of

Lincolnshire." These fine dramatic lines, with their haunting

rhythm and refrain have long been a favourite with public reciters,

and will live when their author's longer and more elaborate

works—such as "Story of Doom," a tale of the world before the

Flood—have been forgotten. Others that were very popular in

their day were "The Song of Seven," a kind of "Seven Ages of Women,"

and "Divided," which is more subjective in character than most of

her poems.

All Miss Ingelow's poetry has qualities that showed her to

possess a genuine gift of expressing herself in melodious verse, and

her powers were always devoted to worthy and to noble themes.

She never succumbed to what Matthew Arnold called "the strange

disease of modern life," and if there be one dominant note in her

song it is quiet joyfulness in the beauties of nature that forbids

anything like querulousness or morbidity. Her appreciation of

the sounds and sights of the country was constantly evident.

In her pages we hear the birds in full song, see the flowers in

bloom, and seem to be brought close to Nature by the thousand vivid

touches that build up the scenes brought before us. In the

poem "Honours" it was one of the lessons she taught that in this

love of natural beauty in its everyday form lay man's truest

happiness.

|

"For me the freshness in the morning hours,

For me the water's clear tranquillity,

For me the soft descent of chestnut flowers,

The cushant's cry for me. |

. . .

. . .

|

"For me the bounding-in of tides; for me

The laying-bare of sands when they retreat,

The purple flush of calm, the sparkling glee

When waves and sunshine meet." |

Besides her poems Miss Ingelow wrote a number of prose

works—fairy stories for children, related with much charm, and

novels appealing mainly to young people. The delicate fancy

and strong sense of character that marked her narrative poems were

also shown in these. But it is as a poet that she will be

remembered, a poet whose gifts were turned to high account, whose

works gave sincere pleasure to very many and offence or pain to

none. |

THE SCOTSMAN

21st July, 1897.

―――♦―――

DEATH OF JEAN INGELOW.

THE

death occurred yesterday, at her residence in Kensington, of Miss

Jean Ingelow, the poet and novelist.

To the younger generation her name is perhaps mainly associated with

the best of her lyrics which have found their way into the

anthologies, and by the many charming songs which Sullivan and other

musicians have enshrined in music. But in her day she achieved

a widespread popularity by her poems and by her novels, and she must

be ranked among those women writers who, while not attaining to

actual greatness, have nevertheless contributed much to the

sweetness and purity of Victorian letters. Miss Ingelow was

born about 1830 at Ipswich, and was thus a mere girl when the Queen

came to the throne. She began to attract public notice about

the time when Mrs Browning's song was failing. Her first book

of poems, entitled "A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and Feelings"

appeared anonymously in 1850, and she soon became a busy and popular

writer. Between 1860 and 1870 she produced abundantly, and to

this period belong "Deborah's Book and the Lonely Rock," "The

Suspicious Jackdaw," "The Minnows with Silver Tails," "Studies for

Stories," "A Story of Doom," "A Sister's Bye-hours," "The High Tide

on the Coast of Lincolnshire." She tried her hand at

novel-writing, and won considerable success with "Off the Skelligs"

(1872) and "Fated to be Free" (1875.) Miss Ingelow's verse

belongs essentially to the class of minor poetry; but it stands high

in its class, and will always find representation in any worthy

anthology of Victorian verse. The prominent note in her verse

was its simple spontaneity. Not that she could evade the

influence of Tennyson, the music of whose verse compelled imitation.

But the emotion, whether it take the shape of joy in the sunshine

and singing of the woods and meadows of England, or of a tender

feminine sympathy with human aspiration and suffering, proceeds from

the heart. In many of her shorter pieces she follows a

tendency of the age, to dream dreams and muse upon the things behind

this veil; but as she does not go too deep she is easily understood.

It is not difficult to point to places where prolixity, hasty work,

and lack of self-criticism may be charged against her; but in "The

High Tide upon the Coast of Lincolnshire," which, with its antique

dialect, won widespread popularity; "Winstanley," "The Long White

Seam," and elsewhere we have manifestations of the poetic gift

sufficient to entitle the writer to a high place among the singers

who have brightened the Victorian era. It is probably by her

shorter lyrical pieces that her name will be preserved. Many

of these are of exceeding beauty of phrase and feeling.

―――♦―――

THE SCOTSMAN

7th August ,1897.

In its obituary notice of Miss Jean Ingelow, the "Athenæum"

gives the following interesting details of her first collection of

poems:— It is, we believe, not generally known that although this

book was highly spoken of and admired, and the first edition was

exhausted with reasonable promptitude, its publishers (Messrs

Longman & Co.) were not prepared to follow it up by a second; and

when Miss Ingelow, accompanied by her mother, went to propose that

they should do so, they said that they did not consider it would be

prudent to incur the risk. As Miss Ingelow, who was much

disappointed, was leaving their establishment, she passed in the

doorway a man with a slip of paper in his hand, and two or three

minutes afterwards was overtaken by a clerk, who came to say that Mr

Longman would be much obliged if she would return to his office.

She went back, and was told that the man whom she had met had come

with an order for 500 copies of her book. This, of course,

necessitated the publication of a new edition, to be followed by

many more editions, and henceforth Miss Ingelow had no more

difficulties with publishers. |

|

Brooklyn

Eagle

21 July 1897

DEATH OF JEAN INGELOW.

If Jean Ingelow had died thirty years ago instead of yesterday her

loss would have called forth copious and heartfelt public lament

wherever the English language was read. To-day the younger

generation of readers feels an uneasy consciousness at the sight of

her name in the newspapers and wonders vaguely what she wrote.

So brief is fame. There is hardly an educated woman in America

over 30 years old who in her childhood did not recite the "Songs of

Seven" or "High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire." Those

poems were literally in everybody's mouth, yet a careful paper this

morning printed one of them as "The Song of the Siren," a title

which would have been as strange to gentle Jean Ingelow as

would one of Laura Jean Libber's perfervid romances.

And all of her one time popularity was deserved. For she was a

true poet, thought her range was narrow. Not the depths of

life, but its sweeter side was it given her to voice; the love of

children, of flowers, and all gentle themes were hers, and her note

if not deep was true and highly individual. Her quality was

deeply, truly womanly, and for that a generation of readers loved

her. She was a true poet also, in that when she had sung her

song she stopped. She has written little if anything for some

years now and her public was spared the pain of seeing its favorite

trying to trade on the reputation of her early successes.

After her volumes of poems, some twenty or more years ago, she wrote

four novels of which two at least, "Off the Skelligs" and "Fated to

Be Free," have great charm, but not those qualities which make a

story teller remembered beyond his own generation. They lack

that grip on all sides of life which ordains a man or woman to be a

novelist. Although they pleased a large circle of readers when

they were new they have now passed to the limbo of forgotten books.

Miss Ingelow will be remembered by her poems and by her life, which

like her writing was womanly and beyond reproach. Like her

fellow worker, Mrs. Oliphant, she has gone to her reward with the

record that she has written nothing base. |

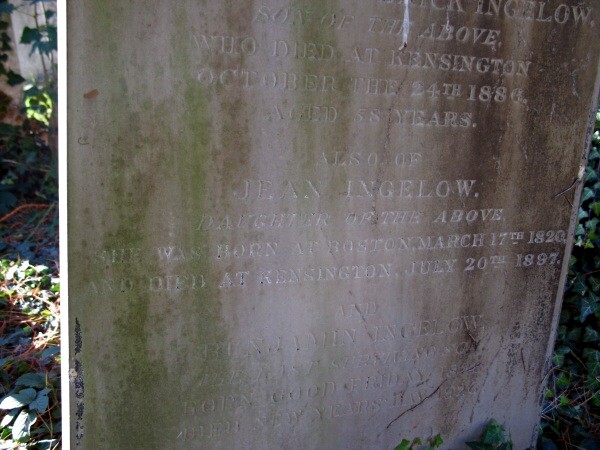

|

The New York Times

July 25, 1897.

BURIAL OF JEAN INGELOW.

_________

Many American Women Present at

the Poet's Internment.

LONDON, July 24.―The remains of Miss

Jean Ingelow, the distinguished poet and novelist, rest in the West

Brompton Cemetery, in the grave where she had buried her father,

mother, and brother. Many Americans were present at the

interment to-day, most of them women, some of whom brought baskets of

daisies because of Miss Ingelow's fondness for them, and her reference

to them in the "Songs of Seven."

John Ruskin sent a cross of roses, and Mme. Antoinette

Stirling, the singer, and Maxwell Gray and other well-known literary

people sent other flowers.

The Bishop of Wakefield officiated, and Mme. Stirling sang

"The Lord is My Shepherd" at the graveside. |

Jean died at her Kensington home on 20th July, 1897 and

was buried in the Ingelow family grave in Brompton Cemetery, West

London, where she lies with her parents and two of her

brothers, and sharing the company of many other notables down to the present

day. The cemetery ― the main

entrance of which is immediately adjacent to West Brompton tube

station ― is both a tribute to

the art of the monumental mason and an island of repose within the

turbulence of West London's busy streets ―

well worth a

visit!

|

SLEEP.

(A woman speaks.) |

|

O SLEEP, we are

beholden to thee, sleep,

Thou bearest angels to us in the night,

Saints out of heaven with palms. Seen by thy

light

Sorrow is some old tale that goeth not deep;

Love is a pouting child. Once I did sweep

Through space with thee, and lo, a dazzling sight—

Stars! They came on, I felt their drawing and

might;

And some had dark companions. Once (I weep

When I remember that) we sailed the tide,

And found fair isles, where no isles used to bide,

And met there my lost love, who said to me,

That 'twas a long mistake: he had not died.

Sleep, in the world to come how strange 'twill be

Never to want, never to wish for thee! |

It's difficult now to imagine the group of

distinguished mourners, including John Ruskin and led by the Bishop of

Wakefield who gathered around Jean's grave on the 24th July 1897 to hear

the operatic contralto

Antoinette Stirling sing "The Lord is my

Shepherd", for this simple unassuming grave is now overgrown and forgotten, yet here lies one of our

most distinguished

women poets.

Jean shares the grave with her parents, William and Jean,

and her brothers William Frederick and Benjamin.

|

COMFORT IN

THE NIGHT. |

|

SHE thought by

heaven's high wall that she did stray

Till she beheld the everlasting gate:

And she climbed up to it to long, and wait,

Feel with her hands (for it was night), and lay

Her lips to it with kisses; thus to pray

That it might open to her desolate.

And lo! it trembled, lo! her passionate

Crying prevailed. A little little way

It opened: there fell out a thread of light,

And she saw wingèd wonders

move within;

Also she heard sweet talking as they meant

To comfort her. They said, 'Who comes to-night

Shall one day certainly an entrance win;'

Then the gate closed and she awoke content. |

Should any reader wish to visit, enter the cemetery through the main gate

(West Brompton tube station entrance); then, following the main (central) pathway, turn into the

third pathway on your left; continue along it, taking the second

pathway on your left. Continue along that pathway, counting 26 graves

along the burial plot on your right-hand side; at the 26th grave, turn into the

burial plot and move away from the pathway for five rows. You will

approach the Ingelow family grave from behind the headstone shown

above. Careful how you go ― the ground is very

uneven.

|

WISHING. |

|

WHEN I reflect

how little I have done,

And add to that how little I have seen,

Then furthermore how little I have won

Of joy, or good, how little known, or been:

I long for other life more full, more keen,

And yearn to change with such as well have run—

Yet reason mocks me—nay, the soul, I weep,

Granted her choice would dare to change with none;

No,—not to feel, as Blondel when his lay

Pierced the strong tower, and Richard answered it—

No,—not to do, as Eustace on the day

He left fair Calais to her weeping fit—

No,—not to be Columbus, waked from sleep

When his new world rose from the charmèd

deep. |

|

THE

GUARDIAN

26th July, 1897.

FUNERAL OF MISS INGELOW.

The funeral of Miss Jean Ingelow took place on Saturday at

West Brompton Cemetery, her remains being laid in the grave

where her father, mother and brother lie buried. The

funeral service was conducted by the Bishop of Wakefield,

assisted by the Rev. G. Thornton, vicar of St. Barnabus,

Kensington. Among those who gathered at the graveside

were Madam Antoinette Sterling, Sir T. Weymss Reid, Sir

Reginald Palgrave, Mr. Mackenzie Bell, Mr. H. S. F. Jebb,

Mrs. Merriman, Mrs. Bassett, and Mr. and Mrs. W. C.

Alexander. The coffin, which was of polished oak, with

brass mountings, bore upon the breast-plate the words, "Jean

Ingelow. Born March 17, 1820; died July 20, 1897."

Above this there was fastened a magnificent cross of roses,

and on the card attached to it, "Mr. Ruskin. In sorrow

and affectionate memory." A bouquet of mignonette was

inscribed, "Antoinette Sterling. With dear love.

There is no death; there is no beginning or end to life."

There were numerous other floral tributes from friends and

admirers. After the Bishop of Wakefield had pronounced

the Benediction, Madame Antoinette Sterling sand, "The Lord

is my Shepherd," all present remaining uncovered until she

had finished. |

――――♦――――

|

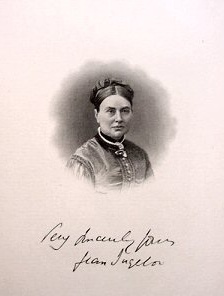

JEAN INGELOW

From an early photograph by

Elliott & Fry, London.

"A girl and a guinea are both alike. You

never know how good they are till you ring them." |

Jean Ingelow's 'Copyright Dinners.'

It was during the Holland Street days that Jean gave

her 'copyright dinners'—for so it appears they were called.

These dinners were of a very unostentatious description, and were

given twice a week to twelve convalescents, chosen by the Kensington

clergy. On one occasion I was present at the meal. The

dinners were served in a rather shabby, good sized room on what we

should call the drawing-room floor, in a street approached by an

archway close to the old churchyard, perhaps pulled down by this

time. A certain Mrs. Hulford, who owned the house, cooked the

dinners. They never varied: roast beef with Yorkshire pudding