|

[Previous

Page]

CHAPTER XVI

CHARTISM

IT has already been mentioned that I found myself

very early in life whirling and swirling round the political maelstrom.

I was a very youthful atom indeed when, fired by the enthusiasm that

seemed to impregnate the air, I became a member of the National Chartist

Association—the association that was formed to demand the immediate

adoption of the People's Charter. The Chartist movement was the only

movement of the time that seemed calculated to captivate the imagination

of young and earnest politicians. I had not then reached the mature

age of seventeen. Before I was two years older I was taking the

chair at Chartist meetings and corresponding with members of Parliament

concerning the treatment of Chartist prisoners. But even at that

time I was "a Chartist and something more," for it appeared to me that the

Charter fell far short of the ideal that ought to be sought and must be

attained before society could be constituted on a proper basis. And

so, while still active in Chartist circles, I was at the age of eighteen

years and a half elected president of a Republican Association! Of

course I had all the confidence of youth. What did statesmen or

philosophers know about the way to manage national affairs, or the

principles on which governments should be based, compared with what I and

my comrades knew? We had generous impulses in those days at all

events. We lacked judgment, discretion, every sort of prudent

virtue; but we despised all mean and sordid interests. It is perhaps

the only excuse that can be offered for the conceit and presumption with

which we of the younger race of politicians astounded and affronted our

elders.

The Chartist movement was some eight or ten years old when I

entered it. The history of the movement—probably the greatest

popular movement of the nineteenth century—has yet to be written.

Materials for a work worthy of the subject are perhaps not abundant. The "Life

of Thomas Cooper," the "Life and Struggles of William Lovett," the

sketch published many years ago by R. G. Gammage, will assist the future

historian. But the story of that stormy episode in the political

life of the working classes could only have been told with effect by a

writer who shared in its passions and was a witness of its weaknesses.

And one by one all those who possessed the requisite acquaintance with the

period have disappeared from the scene. John Arthur Roebuck was

(with an exception to be presently named) the last survivor of the

politicians who, meeting in conference in 1837, passed the resolutions

which afterwards formed the basis of the People's Charter. But as

the most interesting period of the Chartist movement did not commence till

after the Charter had been formally approved at a great meeting in

Birmingham in 1838, there were others besides Roebuck who could have

related as it ought to be related the history of the great agitation.

These, too, however, have also disappeared. So it is extremely

unlikely that any competent or satisfactory narrative of a stupendous

national crisis will ever now be given to the world.

The demand for universal suffrage and other changes in the

mode of representation grew out of the natural discontent of the masses of

the people with the Reform Bill of 1832. That great measure—for,

after all, it was a great measure—satisfied the middle classes; but it

made no change whatever in the political position of the bulk of working

men. There had been a sort of understanding that the power which

would be acquired by the passing of the Reform Bill would be used

afterwards for securing still further improvements in the distribution of

the franchise. But when the expectations thus formed were not

realised, the working classes established associations of their own.

One of these had been initiated by a Cornish carpenter named William

Lovett. The People's Charter, as intimated above, was the outcome of

a conference between representatives of Lovett's association and certain

members of Parliament who sympathised with the popular demand. The

members of Parliament comprised Daniel O'Connell, Charles Hindley, John

Temple Leader, [15] William Sharman Crawford, John

Fielden, Thomas Wakley, John Bowring, Daniel Whittle Harvey, Thomas

Perronet Thompson, and John Arthur Roebuck.

|

|

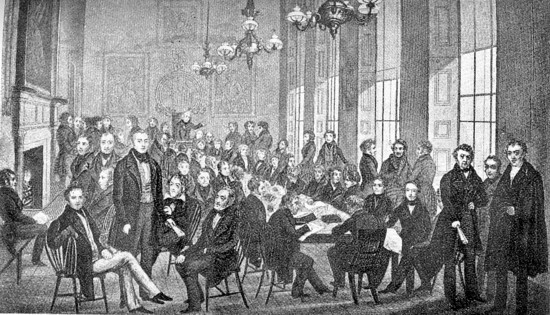

THE CHARTIST CONVENTION OF 1839.

(From a contemporary print.) |

Having agreed to certain

propositions, the conference appointed a committee of twelve persons—six

members of Parliament and six members of the London Working Men's

Association—to draw up a Bill embodying the principles that had been

approved. The working men so appointed were Henry Hetherington, John

Cleave, James Watson, Richard Moore, William Lovett, and Henry Vincent,

while the six members of Parliament were O'Connell, Roebuck, Leader, Hindley, Thompson, and Crawford. The document which was drawn up by the

committee, and which came soon to be known as the People's Charter, made

formal demands for six points—universal suffrage, vote by ballot, annual

parliaments, equal electoral districts, payment of members, and the

abolition of the property qualification. The Charter, adopted at a

great meeting held in Birmingham on Aug. 6th, 1838, was submitted to a

meeting held in Palace Yard, London, in the following month, when one of

the resolutions was moved by Ebenezer

Elliot, then famous as the "Corn-Law Rhymer."

It was resolved at both gatherings to call a Convention of

Delegates, and to obtain signatures to a National Petition beseeching

Parliament to enact the Charter. The Convention, which consisted of

fifty-five delegates, said to have been elected by three millions of

persons, met first in London, and subsequently in Birmingham. The

meeting in London was held at the British Coffee House, Feb. 4th, 1839.

A print of the scene, giving portraits of some of the principal members of

the Convention, was published at the time. All the members are now

dead, George Julian Harney, who died in 1897, being, I believe, the last

survivor. The National Petition, bearing, it was alleged, 1,280,000

signatures, was placed in the hands of Mr. Thomas Attwood, then member for

Birmingham, the leading spirit of one of the Political Unions which had

been chiefly instrumental in carrying the Reform Bill. There were

probably exaggerations as to the numbers which took part in the election

of delegates; but the rapidity with which the movement spread to every

part of the country, and the enthusiasm with which it was received in all

the great centres of population, could not be exaggerated. The

portentous agitation was viewed with some alarm by the Government, which

set about an attempt to arrest it. Unfortunately, the purposes of

the Government were assisted by the Chartists themselves; for they

indulged in foolish language, resorted to foolish threats, and commenced

preparations for still more foolish proceedings. Arms were bought;

bands were drilled; the "sacred month" was suggested. But the

Convention dissolved in the autumn of 1839, and the Charter was as far off

as ever.

The popular power which the movement had developed, however,

did not dissolve with the Convention. Many men of mark and vigour,

besides the originators of the Charter, joined the agitation. Not

the least eloquent of these was Thomas Cooper, and not the least energetic

George Julian Harney. But the most prominent of them all was an

Irishman—Feargus O'Connor. Gifted with great talent for winning the

favour and applause of the populace, O'Connor was then and for long

afterwards the idol of the day. Hundreds of thousands of working men

were almost as devoted to him as the better spirits of Italy at a later

date were devoted to Joseph Mazzini. When he addressed in the rich

brogue of his native country "the blistered hands and unshorn chins of the

working classes," he appeared to touch a chord which vibrated from one end

of the kingdom to the other. Wherever he went he was sure of a vast

and appreciative audience.

The popularity of the Northern Star, which O'Connor

had established as the organ of the movement, was almost equal to his own.

But, powerful as O'Connor was, and vast as was the circulation of the

Northern Star, no great progress seemed to be made in influencing either

the Ministry or the Parliament. A new Convention was subsequently summoned

in London—John Frost having in the meantime made his abortive attempt at

Newport—and a new association was projected by Lovett. Bitter feuds,

however, broke out between O'Connor and the rest of the Chartist leaders,

so that much of the strength of the agitation was wasted in personal

squabbles. Moreover, the most absurd schemes were proposed for forcing the

Government to yield to the popular demands.

I have alluded to the "sacred month." This was a

proposition that the working classes should enter upon a strike for that

period throughout the whole country. Thomas Cooper tells us how an

old Chartist, who had been a member of the first Convention, proposed at a

meeting in the Potteries "that all labour cease till the People's Charter

becomes the law of the land." The same wild scheme, not long

subsequently, was submitted by Dr. McDouall, who had then become a

prominent leader of the movement, to a meeting of the Chartist Executive

in Manchester. Another singular device was that the people should

abstain from consuming excisable articles, so as to paralyse the financial

arrangements of the Government. There were partial strikes in

Lancashire; Chartist families here and there (my own included) abstained

for a time from using tea, coffee, sugar, spirits, and tobacco; but the

attempt to obtain the Charter by these means failed as utterly as the

attempt of Frost to promote an insurrection of the labouring classes in

Wales.

The aims and claims of the Chartists were, to a certain

extent, shared and approved by middle-class Radicals. With the view

of separating what was reasonable in the movement from what was

ridiculous—the principles of the Charter from the violent means which were

advocated to secure them—there had been formed what was called the

Complete Suffrage party. Joseph Sturge, an estimable Quaker of

Birmingham, was the chief figure in the new party. Associated with

Edward Miall, Laurence Heyworth, the Rev. Thomas Spencer, and the Rev.

Patrick Brewster, Mr. Sturge had entered into negotiations with Lovett,

Collins, Bronterre O'Brien, and other old Chartists who dissented from

O'Connor's tactics. The result was another conference—the Birmingham

Conference of 1843. Four hundred delegates assembled on the

occasion. The Conference was, perhaps, the most important—certainly

the most influential—gathering of the kind that had been held since the

Charter had been promulgated. Thomas Cooper, who was present,

informs the readers of his biography "that the best orator in the

Conference was a young friend of Lovett's, then a subordinate in the

British Museum, but now known to all England as the highly successful

barrister, Serjeant Parry." But neither Parry's eloquence nor

Sturge's good intentions could evoke harmony out of the discordant

elements that had then met together. If there had been anything like

union, the political future of England might have been changed. As

it was, the Conference broke up in confusion.

The divisions which were manifested in Sturge's Conference

became more marked in the councils of the Chartists themselves.

O'Connor added to these divisions by mixing up with the demand for the

suffrage his disastrous and preposterous Land Scheme. Nevertheless,

he kept his hold of the movement down to the time of the great

demonstration on April 10th, 1848. Excited by the events which had

just taken place in France, the Chartists thought they saw an opportunity

of impressing the Government with the extent of their numbers, if not with

the justice of their claims. Unfortunately, they only succeeded in

frightening the Government into acts of trepidation and terror. Nor

did the new National Petition they promoted produce any effect on the

Legislature. The failure of the demonstration on Kennington Common

marked a turning-point in the history of Chartism. Down to that time

it had at least maintained its position in the country; but after that

time it began to decline.

The authority and influence of the great Feargus, weakened by

the events of April 10th, weakened still further by the gradual collapse

of his land ventures, rapidly faded away. Other men became prominent

in what remained of the movement—Ernest Jones,

Gerald Massey, and the founder of

Reynolds's Newspaper. Various attempts were likewise made to

resuscitate the agitation—notably by Thornton Hunt and

George Jacob Holyoake. But

Chartism as a political force was beyond redemption. Julian Harney

and Ernest Jones helped to keep it alive by means of publications—Red

Republicans, Friends of the People, Vanguards, Notes to the People,

People's Papers, and other periodicals whose very names are now almost

forgotten. But the few that continued the struggle quarrelled among

themselves. Harney at last abandoned the now hopeless business.

Jones, however, supported by a declining number of adherents, maintained

the fight down to 1857, when he too was starved into surrender.

Penury was the lot also of one of the best known of the Chartist

officials. For many years during the latter period of the agitation

the name of John Arnott as general secretary appeared at the foot of all

the official notices of the Chartist Association. Some time about

1865 I was standing at the shop door of a Radical bookseller in the

Strand. A poor half-starved old man came to the bookseller,

according to custom, to beg or borrow a few coppers. It was John

Arnott! Chartism was then, as it really had been for a long time before, a

matter of history.

CHAPTER XVII

YOUNG CHARTISTS AND OLD

FEW men now living, I fancy, had an earlier

introduction to Chartism than I had. My people, though there wasn't

a man among them, were all Chartists, or at least all interested in the

Chartist movement. If they did not keep the "sacred month," it was

because they thought the suspension of labour on the part of a few poor

washerwomen would have no effect on the policy of the country. But

they did for a time abstain from the use of excisable commodities.

There were other indications of their tendencies. We had a dog

called Rodney. My grandmother disliked the name because she had a

curious sort of notion that Admiral Rodney, having been elevated to the

peerage, had been hostile to the people. The old lady, too, was

careful to explain to me that Cobbett and Cobden were two different

persons—that Cobbett was the hero, and that Cobden was just a middle-class

advocate. One of the pictures that I longest remember—it stood

alongside samplers and stencilled drawings, and not far from a china

statuette of George Washington—was a portrait of John Frost. A line

at the top of the picture indicated that it belonged to a series called

the Portrait Gallery of People's Friends. Above the head was a

laurel wreath, while below was a representation of Mr. Frost appealing to

justice on behalf of a group of ragged and wretched outcasts. I have

been familiar with the picture since childhood, and cherish it as a

memento of stirring times.

Another early recollection is that of a Sunday morning

gathering in a humble kitchen. The most constant of our visitors was

a crippled shoemaker, whose legs were of little use except to enable him

to hop or hobble about on a pair of crutches. Larry—we called him

Larry, because his Christian name was Laurence, and we knew no other—made

his appearance every Sunday morning, as regular as clockwork, with a copy

of the Northern Star, damp from the press, for the purpose of

hearing some member of our household read out to him and others "Feargus's

letter." The paper had first to be dried before the fire, and then

carefully and evenly cut, so as not to damage a single line of the almost

sacred production. This done, Larry, placidly smoking his cutty

pipe, which he occasionally thrust into the grate for a light, settled

himself to listen with all the rapture of a devotee in a tabernacle to the

message of the great Feargus, watching and now and then turning the little

joint as it hung and twirled before the kitchen fire, and interjecting

occasional chuckles of approval as some particularly emphatic sentiment

was read aloud. But Larry had other gods besides Feargus. One

was William Cobbett. Among his cherished possessions were two little

volumes of Cobbett's works—the "Legacy to Parsons" and the "Legacy to

Labourers." These volumes, I recollect (for Larry, though I was but

a lad, loaned them to me as a special and particular favour), were

preserved in wash-leather cases, each made to fit so exactly and close so

tightly that no spot or stain of any sort should reach the precious pages

within. Poor old Larry had a brave and wholesome heart in a most

misshapen frame. Dead for fifty years, he yet lives in at least one

loving memory.

The humble shoemaker, though he longed for the emancipation

of his class, and made what sacrifices he could to achieve it, turned his

modest circumstances to the best account. No pot-house politician

he. Larry and his wife were as cheerful a couple as could be found

in the town. Riches are not necessary to produce the blessings and

comforts of home. A bright fireside is not incompatible even with

poverty, or at least with the very humblest of means. This was

demonstrated in Larry's cottage. It consisted of just two rooms—a

kitchen and a loft—though it had what are almost unknown advantages in

large towns: a plot of ground for flowers in front and a bigger plot for

fruits and vegetables at the back. But it is Larry's kitchen—at once

his parlour and his workshop—that lives in my recollection. To say

that it was as "clean as a new pin" is to give but a faint idea of the

spotless brightness of everything in it. The very floor, brick

though it was, was better scrubbed than many a dining table I have seen

since. The pots and pannikins, the cans and canisters, those simple

tin or pewter ornaments of the mantelshelf, shone like silver. All

else about the apartment, where there was a place for everything and

everything was in its place, was equally conspicuous for the polish that

was given to it. Larry's cottage, as the result of the industry of

Larry's wife, was a veritable palace for cleanliness and comfort.

Even the old cripple's low shoes were a wonder; for they shone so

brilliantly that a cat, seeing her reflection in them, as in the pictorial

advertisements of Day and Martin's blacking of that time, would have

almost arched her back for a conflict with her counterpart. And the

venerable couple, in spite of their penury, were probably as happy a

couple as any in the kingdom. If all Chartist homes had been as well

kept as Larry's, there might have been less discontent in the country, but

there would have been more force and vitality in the movement to which the

masses of the people gave their sanction. As a striking example of

devotion to political ideals among the poor, the lame old shoemaker

retains a treasured place in the recollection of the days that are gone.

While I was still a boy, though even then interested in

political affairs, our town was visited by two of the Chartist chiefs.

One was Feargus O'Connor, the other Henry Vincent. Some excitement

was caused by the intimation that the former gentleman was expected to

arrive by a certain route at a certain time. I joined a party of

elder people to go out and meet him. We went to a neighbouring

village, sat on a bridge, and waited. Our visitor did not come—at

least, not our route. That night or the next night I have a faint

recollection of seeing an orator in his shirtsleeves addressing a crowd in

the markets. It was Feargus. He was expected again in the

first month of 1848, when a procession of carts and waggons passed through

the town on the way to Snig's End, one of the estates which had been

purchased under the Land Scheme. This time, however, he did not come

at all. Vincent's visit occurred about 1841. It was after the

"young Demosthenes," as he was called, had suffered two periods of

imprisonment—first in Monmouth Gaol, and afterwards at Millbank and Oakham.

The meetings he addressed were held in a stable or coach-house—at any rate

the room or building was in a livery stable yard. I recollect the

locality well, though not a word that was said there. What I do

recollect also is the suspicions that were expressed in our household as

to the cause of the change of tone observable in Vincent's utterances

before and after imprisonment. The fiery and reckless orator of 1839

had become sober and restrained. The simple people of that day could

only account for the change on the ground that the Government had somehow

found means to influence or corrupt him. When Vincent next appeared

in the town, it was as the spokesman of the Peace Society, not of the

Chartist Association.

Chartism had interested me as any other stirring movement

with which my friends and relatives were connected would have done.

But the time soon arrived when I became interested in it on my own

account. The local leader of the party was a blacksmith—J. P.

Glenister. Others with whom I became associated—all much older than

myself—were shoemakers, tailors, gardeners, stonemasons, cabinetmakers,

the members of the first-named craft greatly predominating. There

had been an earlier leader of the name of Millsom, a plasterer; but he, I

think, was then dead. Next to Glenister's the names I best remember

among my old associates—all forgotten now save by a very few—were those of

Hemmin, Sharland, [16] Glover, Hiscox, Knight, Ryder,

and Winters. They were earnest and reputable people—much above the

average in intelligence. Glenister was probably the least educated

among them. But he had one qualification which the others had not—he

could make a speech. Not much of a speech, perhaps, though the

speaker generally contrived to make his audience understand what he wanted

to say. The old blacksmith usually, in virtue of his standing among

us, presided over our meetings. One night, while he was so

presiding, somebody spoke of Tom Paine. Up jumped the chairman.

"I will not sit in the chair," he cried in great wrath, "and hear that

great man reviled. Bear in mind he was not a prize-fighter.

There is no such person as Tom Paine. Mister Thomas Paine, if you

please." Glenister soon afterwards emigrated with his family to

Australia, and one heard of him occasionally as doing well in his new

home—which, being an honest and industrious man, he was every way likely

to do.

It came to pass that the insignificant atom who writes this

narrative, having all the effrontery of youth, took a somewhat prominent

part in the Chartist affairs of the town. The first important

business in which he was concerned was the National Petition for the

Charter which was set afloat immediately after the French Revolution of

1848. It was alleged to have received 5,700,000 signatures; but the

number was subsequently reduced to 2,000,000, which included many

fictitious names—the work of knaves and enemies in order to bring

discredit on the document. The animated scenes at our meetings where

the petition lay for signature are still fresh in the memory. Then

came active operations for getting Chartist leaders to the town.

Thomas Cooper was rather a frequent visitor. Two

impressions remain—one, that he recited Satan's speech from Milton with

magnificent effect; the other, that he had a most irritable temper.

I had been concerned with another youth in organizing a lecture at the

Montpellier Rotunda. We had occasion to whisper to each other about

some matter of business while the lecture was being delivered.

Cooper caught sight of us, stopped, and then covered us with confusion as

he solemnly assured the company that he would only resume his discourse

"when those two young men have finished their conversation." The

matter of business, whether it suffered from the delay or not, had to

stand over till the close of the meeting.

Cooper's visit happened in March, 1851. Three months

later came Ernest Jones. Our gathering, in default of a better

place, was held in a market garden. It was not a large

gathering—only 150 or 200 present, the result, probably, of showery

weather. Jones had been in prison the year before for uttering

seditious language. The treatment he had suffered was abominable.

Petitions for inquiry were promoted; a select committee of the House

Commons was appointed to investigate; a blue book containing the evidence

was printed; and there, I think, the matter ended. As chairman of

one of the meetings, I had some correspondence with Mr. Grenville

Berkeley, then member for Cheltenham. The hon. gentleman was

courteous in his replies, sent me a copy of the blue book, but could not,

or at any rate did not, do anything else.

Our next Chartist visitor, I recollect, was Mr. R. G.

Gammage, the author of a sketch of the history of Chartism [Ed.—"History

of the Chartist Movement"], who subsequently studied medicine under

great difficulties, and settled down as a practitioner in Sunderland.

Gammage's visit coincided with the occurrence of the General Election of

1852. We therefore got him nominated so that he might have an

opportunity of making a speech from the hustings. This was all we

wanted, for of course it would have been utterly useless to go to the poll

in the then state of the franchise. Suffice it to say that Gammage

made what we all thought a capital speech for the Charter.

There will be other occasions for describing the old

electoral methods. But I may perhaps be excused for referring in

this place to an affair preliminary to the contest of 1852 in which I bore

a small part. The Chartists, even though they had few votes, were at

that time numerous enough to make their favour worth cultivating.

The agents of the Whig party therefore organized an open-air meeting of

the working classes in the Montpellier Gardens. It was attended by

about 2,000 persons. The resolutions were ingeniously framed to

propitiate the Chartists and at the same time assist the candidature of

the Whig nominee. Having, I suppose, made myself conspicuous at some

of our meetings, I was invited to take part with Glenister in this

gathering of working men. One of my aunts happened to be passing the

Gardens, heard the cheers and saw the crowd, and so went to see what was

the matter. Great was her astonishment to observe her precocious

nephew on the platform proclaiming at the top of his voice the inalienable

right of every man to the suffrage! The agents of Mr. Craven

Berkeley, then the Whig candidate for the town, turned the meeting to good

account, advertising in all the local papers the resolutions that had been

adopted, with the names of the working men and others who had proposed and

seconded them. I was told I had done well on the occasion. [17]

If so, it was the only time I ever did well in like circumstances.

But I had an uneasy consciousness that we had been "used" by the party

wire-pullers; as, indeed, we no doubt had been. Used or not,

however, we had the satisfaction a few weeks later of hearing our own

candidate propound the true doctrine from the hustings.

CHAPTER XVIII

FOOLISH AND FIERY CHARTISTS

CHARTISTS were of many sorts. There were

moral-force Chartists and physical-force Chartists; there were Chartists

and something more; there were whole-hog Chartists, bristles and all; and

there were Chartists who cried aloud, "The Charter to-day, and roast beef

the day after!" Indeed, the divisions among them were almost

endless—at least as endless as the men who set up as leaders, for every

little leader had his little following, while the bigger leaders had

bigger followings. It was these divisions that robbed the movement

of the power it would otherwise have wielded and of the success it would

otherwise have achieved. But the chief cause of dissension was the

means that should be pursued to attain the end desired. While the

wiser heads were advocates of moral pressure, the more foolish and furious

contended that carnal and lethal weapons were the only weapons Governments

could be made to fear or understand.

There was, no doubt, some excuse for the wilder spirits of

the movement, inasmuch as the middle classes not long before had set the

example of truculence. The men of 1832, who demanded "The Bill, the

whole Bill, and nothing but the Bill," were just as violent in the

language they used as the bitterest of the Chartists. Nor did they

scruple to threaten the direst consequences to the aristocracy, and even

to royalty itself, if reform should be denied. An instance of the

desperate measures to which the middle classes were prepared to resort at

that period was disclosed to William Lovett by one of the principals

engaged to carry out the scheme. "When," writes Lovett, "the Duke of

Wellington was called to the Ministry, with the object, it was believed,

of silencing the Political Unions and putting down the Reform agitation,

an arrangement was entered into between the leading Reformers of the North

and Midland Counties and those of London for seizing the wives and

children of the aristocracy and carrying them as hostages into the North

until the Reform Bill was passed. My informant, Mr. Francis Place,

told me that a thousand pounds were placed in his hands in furtherance of

the plan, and for hiring carriages and other conveyances, a sufficient

number of volunteers having prepared matters and held themselves in

readiness. The run upon the Bank, however, having been effective in

driving the Tories from office, this extreme measure was not necessary."

Moreover, the surrender of the Duke of Wellington, who confessed that he

had to choose between civil war and compliance with the wishes of the

people, had gone a long way to warrant the conclusion that Governments

were more amenable to force than to reason.

The Chartists had, perhaps, another excuse in the ferocious

sentiments which a minister of religion had uttered in the course of the

agitation against the New Poor Law. This agitation was in full swing

when the Charter was framed. The year which witnessed the inception

of that instrument witnessed also the unrestrained eloquence of Joseph

Rayner Stephens. This reverend firebrand, whose biography has been

written by George Jacob Holyoake, was not a Chartist. As a matter of

fact, he seemed to care little for the political rights of the people so

long as certain of their social and domestic rights were not infringed.

But it was no fault of his that he did not plunge the land into fire and

bloodshed. Speaking at Hyde on Nov. 14th, 1838, just after the

Charter had been promulgated, he advised his hearers to "get a large

carving-knife, which would do very well to cut a rasher of bacon or run

the man through who opposed them."

Earlier in the same year (on January 1st) Mr. Stephens was in

Newcastle. This is what he is reported to have said there:— "The

people are not going to stand this (the New Poor Law), and he would say

that, sooner than wife and husband, and father and son should be sundered

and dungeoned and fed on 'skillee'—sooner than wife or daughter should

wear the prison dress—sooner than that, Newcastle ought to be, and should

be, one blaze of fire, with only one way to put it out, and that was with

the blood of all who supported this abominable measure."

Mr. Stephens declared in the same speech—"He was a

revolutionist by fire; he was a revolutionist by blood, to the knife, to

the death. If an unjust, unconstitutional, and illegal parchment was

carried in the pockets of the Poor Law Commissioners, and handed over to

be slung on a musket or a bayonet, and carried through their bodies by an

armed force or by any force whatever (that was a tidy sentence), and if

this meeting decided that it was contrary to law and allegiance to the

Sovereign—that it was altogether a violation of the Constitution and of

common sense—it ought to be resisted in every legal way. It was law

to think about it, and to talk about it, and to put their names on paper

against it, and after that to go to the Guildhall and to speak against it.

And when that would not do, it was law to ask what was to be done next.

And then it would be law for every man to have his firelock, his cutlass,

his sword, his pair of pistols, or his pike, and for every woman to have

her pair of scissors, and for every child to have its paper of pins and

its box of needles—(here the orator's voice was drowned in the cheers of

the meeting)—and let the men, with a torch in one hand and a dagger in the

other, put to death any and all who attempted to sever man and wife."

With such examples before them, it was not surprising that

the Chartists also used violent language. Nor was it surprising,

perhaps, that they went further, and conceived violent projects.

Violent projects were certainly conceived in many parts of

the country. A plot was formed to seize Dumbarton Castle; Frost,

Williams, and Jones endeavoured to raise an insurrection in Wales; there

was even a scheme to burn down Newcastle. The story of the Tyneside

episode is told by Thomas Ainge Devyr. The book in which it is

recorded is rightly enough named—"The Odd Book of the Nineteenth Century."

It was published by its author in New York in 1882. Patrick Ford had

at that time accorded Devyr "the privilege of having letters addressed to

him at the office of the Irish World." It was in that office

in that year that I made his acquaintance. The acquaintance was

renewed some years later, when Devyr, then a very old man, revisited the

scene of the agitation in which he had taken an active part fifty years

before. My old friend had led an adventurous life—in Ireland, in

England, in America. He was a Nationalist in Ireland, a Chartist in

England, a kind of revolutionist even in America. Anyway, he had

only scorn and contempt for the politicians of America. "Democrats?"

he said to me: "they call themselves Democrats, but they are all thieves."

While in England, he served on the staff of the Northern Liberator—a

Radical newspaper which had been established in Newcastle by Augustus

Beaumont, a member of the Jamaica Legislature, but which was afterwards

acquired by Robert Blakey, then a prosperous furrier in Morpeth, later a

professor in an Irish College. Devyr, as a writer on the

Liberator and the corresponding secretary of the revived Northern

Political Union, seems to have written most of the turgid manifestoes of

the party that appeared during 1838. Many are set out at length in

his "Odd Book." It is clear, too, that he was closely associated

with the sanguine or sanguinary men of the period—Thomas Horn, Robert

Peddle, John Rewcastle, Dr. Hume, William Thompson, John Mason, Thomas

Hepburn, James Ayre, Richard Ayre, John Blakey, Edward Charlton, and a

blind orator named Cockburn—down to the time when he deemed it prudent to

seek safety across the Atlantic. Now to his story.

Disturbances occurred in Birmingham early in August, 1838.

"Then," says Devyr, "commenced the work of 'preparation,' and from that

time to November we computed that 60,000 pikes were made and shafted on

the Tyne and Wear." The number, he admits, would seem to be

exaggerated. But—"I was present in some part of nearly every

Saturday at the pike market, to take sharp note of the sales. The

market was held in a long garret room, over John Blakey's clog shop in the

Side. In rows were benches or boards on tressels, among which the

Winlaton and Swalwell chain-makers and nail-makers brought in their

interregnum of pikes, each a dozen or two, rolled up in the smith's apron.

The price for a finished and polished article was two and sixpence.

For the article in a rougher shape, but equally serviceable, the price was

eighteenpence." Besides pikes and pike-shafts, caltrops, intended to

be strewn over the roads for the purpose of laming the horses of the

cavalry, were manufactured at Winlaton. On one occasion, as Devyr

tells us, a case of fifty muskets and bayonets was imported from

Birmingham. And shells and hand-grenades were manufactured to

scatter destruction all around.

The conspirators meant business, or at any rate mischief.

One of the orators had declared—"If the magistrates Peterloo us, we will

Moscow England." The secret organization, according to Devyr, took

the form of classes of twelve, each with a captain, and all sworn to obey

orders, maintain secrecy, and execute death upon traitors. "It was

strongly urged that on the night of the 'rising' all the Corporation

police should be slain on their beats." The outbreak was to begin on

a Saturday night. But only seventy men out of ten times that number

who had enrolled themselves gathered on the night preceding it.

"Finding they were not in a condition for a stand-up fight, it was

strongly urged that the torch should be resorted to." Newcastle was

to be reduced to a heap of blackened and smoking ruins.

Meantime, news had arrived of the failure in Wales. It

was resolved to await events. But the old desire for burning and

bloodshed came back again. "We have resolved to do it," cried John

Mason: "we must rouse the people by some desperate action, and the torch

is to be the action." Devyr protested; but the conspirators informed

him that "flame and combat would have full possession of Newcastle before

midnight." All the same, the day dawned without disturbance, and

soon afterwards the conspirators were either in flight or in hiding.

Such is the story of my Irish friend, Thomas Ainge Devyr.

It is a story I have heard old Chartists dispute, and other old Chartists

say they believe. Devyr concludes his narrative with the mention of

two humorous incidents. One was that James Ayre, a builder to trade,

declared when he was arrested that he would agitate no more in the old

way, but for the time to come would "agitate the bricks and mortar."

The other incident was that Robert Peddle, "a man of all work or any

work," threatened Devyr and Rewcastle with the scaffold, because they

would not furnish him with a horse and carriage to capture Alnwick Castle!

The castle, Peddle averred, contained arms and treasure, while "its

pastures were filled with just such rations as the revolutionary forces

required." "A young butcher followed in his train for several days

to take charge of this department!"

The spirit of violence, or rather to threaten violence,

animated some of the physical-force Chartists long after the Newcastle

conspirators had fled or been imprisoned. When George Julian Harney

was nominated on the hustings at Wakefield against Lord Morpeth, an old

friend of mine who was present describes the striking effect produced as a

forest of oak saplings rose in the air in answer to the call for a show of

hands for the Chartist candidate. Nor was it the Government alone

that was apprehensive of disorder on the day of the memorable

demonstration on Kennington Common. The fear was general that the

great gathering would end in a deluge of blood. I remember reading

in the newspapers of the time (and not without a glow of satisfaction on

my own part) how an Irish orator had exclaimed that London would be in the

hands of the Chartists on April 10th, and that that would be the signal

for insurrection in all parts of the kingdom. A later friend of my

own, I know, went armed to the gathering. Happily, neither he nor

others had occasion to use their weapons. An echo of the trepidation

among simple folks was heard as late as 1854. When a deaf old lady

in Gateshead was alarmed by the great explosion of that year, she hurried

away to her friends in Sunderland. Asked what was the matter, she

replied: "Aa's afeared the Chartist bodies hev brokken lowse!"

CHAPTER XIX

THE FATHERS OF THE CHARTER

THE usual notion of an agitator is that he is a man

with the "gift of the gab"—what the Americans call a spellbinder.

But five of the six representatives of the Working Men's Association who

assisted in framing the People's Charter were not platform people at all.

None of the five—John Cleave, Henry Hetherington, William Lovett, James

Watson, Richard Moore—made any pretence to oratory, and seldom appeared

before the public in person. But every one of them was as thoroughly

honest and single-minded as any similar number that ever entered a public

movement. Moreover, they had all been concerned more or less

intimately in the great struggle for a free press. Lovett, a born

organizer, organized many political and social associations of an advanced

character—advanced, I mean, for that time. Cleave and Hetherington

were printers—Hetherington the printer of that Poor Man's Guardian

which helped so much to establish the liberty of unlicensed printing.

I had the honour of the acquaintance of Moore and Watson. Moore,

married to a niece of Watson's, lived a life of industry and great

domestic happiness in Bloomsbury, took an active part in the Radical

affairs of the Borough of Finsbury, and served his day and generation

effectually as the chairman of the committee of the Society for the Repeal

of the Taxes on Knowledge. But of Watson, whom I knew intimately for

twenty years, I must write at greater length.

James Watson was a native of Malton, where he was born in

1799. His mother, who was left a widow soon after he was born,

obtained a situation at the parsonage, where she read Cobbett's Register

and "saw nothing bad in it." James himself was apprenticed to the

clergyman to learn field labour; but his indentures, owing to the reverend

gentleman leaving Yorkshire for another part of the country, were

cancelled before he had finished his time. Thereupon the youth set

out for Leeds in search of friends and employment. While working in

a warehouse, he too began to read Cobbett's Register and "saw nothing bad

in it." Besides Cobbett's writings, he early made the acquaintance

of other Radical literature of the day—Wooler's Black Dwarf and Carlile's

Republican. He made the acquaintance also of some of the Radical

politicians of Leeds. Richard Carlile was at that time fighting the

Government for the right of free discussion. When the intrepid

bookseller, his wife and sister, were thrown into prison, he appealed to

his political friends in the country to come up and help him. Watson

was the second volunteer who went from Leeds. For the heinous

offence of selling publications of which the authorities did not approve,

he was, as I shall have occasion to show, thrice condemned to

imprisonment.

It was while assisting in the agitation for a free press that

Watson learned the art of a compositor, in the office in which the

Republican was printed. There was then in London, associated

with all the fearless movements of that exciting time, a young man of rare

talent and large fortune—Julian Hibbert. When Watson was attacked

with cholera in 1825, Hibbert took him to his house, nursed him, and saved

his life. After his recovery, Hibbert, who had set up a press of his

own, employed him to print some works in Greek. Watson's friend and

saviour, around whom there hangs a haze of mystery and romance that can

never be penetrated, died early, leaving Watson his press and printing

materials. With the help of Hibbert's legacy, after an interval of

propagandism on behalf of the views of Robert Owen, the Yorkshire Radical

commenced business as a printer and publisher on his own account.

For something like a quarter of a century, assisted by his estimable wife,

who was as devoted as himself to the propagation of Radical ideas, he sent

forth a flood of the most advanced literature of the day. The works

he issued were the classics of the working classes—such as Paine's "Rights

of Man," Godwin's "Political Justice," Lamennais' "Modern Slavery,"

Volney's "Ruins of Empires," and Owen's "Essays on the Formation of

Character." His little shop, too, was the rendezvous of Radical

writers and thinkers. We shall see presently that he did not neglect

other duties while attending to his own business. Watson contrived,

by printing and folding as well as selling his publications, to make

Radicalism pay its way. So that when he retired from the publishing

trade in 1854 he had realised a small but sufficient competence.

Thereafter, with one or two exceptions, as when he assisted

in 1858 to form a committee of defence for Edward Truelove, then being

prosecuted by the Government for publishing an alleged libel on Louis

Napoleon, he lived a life of quiet enjoyment and well-earned ease.

Dying in 1874, he left behind him a name and fame that ought not, even by

Radicals of a later era, to be allowed to perish or sink into oblivion.

If I devote a little further space to recollections of James Watson, it is

because the exposition will serve to elucidate the dejected condition of

the press when he and other daring men of the period undertook its

emancipation. Radicals of our day have had no experience, and can

form but a poor conception, of the trials, difficulties, and privations to

which the Radicals of a former generation were exposed. The struggle

for an unstamped press was maintained with a courage and enthusiasm which

almost excite one's wonder—which certainly arouse one's admiration—as its

incidents are recalled to mind. It was the policy of the Government

of that date to repress alike liberty of thought and liberty of speech.

The former of these objects was sought by prosecutions for what were then

called blasphemous and seditious publications; to attain the latter, no

newspaper was allowed to be issued without a fourpenny stamp.

Carlile, Hetherington, Cleave, and Watson, aided by a host of Radicals in

the provinces—notably Abel Heywood in Manchester—fought the Government on

its own ground. We have seen how Carlile, his wife and sister, were

all in prison at one time. Carlile himself spent nearly ten years of

his life in prison altogether. The number of his shopmen and

assistants, men and women, who shared his fate, could be counted by the

score. Hetherington, publishing his Poor Man's Guardian in

defiance of the stamp law, brought another contingent for the Government

to prosecute and imprison. No fewer than five hundred persons were

sent to gaol in the course of three years and a half for selling the

unstamped Guardian alone! Mr. Spring Rice, at that time

Chancellor of the Exchequer, informed the House of Commons in 1836, that

three hundred persons had been imprisoned in the course of a few weeks for

selling unstamped papers in the streets, and that, too, without in the

slightest degree decreasing the sale! Indeed, the gaols of the

country were almost choked with political prisoners, when the Government,

assigning as a reason the impossibility of enforcing the law, surrendered

to the champions of a free press.

It was during this magnificent agitation that James Watson

underwent his three imprisonments—twelve months in 1823 for selling

Palmer's "Principles of Nature," six months in 1833 for selling the

Poor Man's Guardian, and six months again in the following year for

selling the Conservative, another of Hetherington's papers.

What he suffered in these repeated incarcerations is told in the memoir

which Mr. W. J. Linton wrote and published in 1880 [Ed. possibly this

article]. Suffice

it to say that he was "subjected to the same treatment as pick-pockets,

swindlers, passers of bad money, committers of rape and other criminal

acts of a like kind." It will perhaps surprise many who read what I

am now writing that it was through such tortures as these, inflicted on

hundreds of the best people in the country, that we eventually came into

possession of an untaxed and unfettered press. Owing to the

exertions of Watson and his comrades, the stamp duty was reduced from

fourpence to a penny. But the agitation did not stop here, though it

afterwards took another form. As everybody knows, or ought to know,

the efforts of the Society for the Repeal of the Taxes on Knowledge

resulted on the total abolition, not only of the stamp duty, but of the

paper duty as well.

And now I may be pardoned a few words on the personal

qualities of the man. James Watson had the purity of a saint, the

spirit of a hero, the courage of a martyr. He was not only free from

reproach—he was, like Cæsar's wife, above

suspicion. The trying period during which he was most prominent was

fatal to many reputations. It was an age of imputation. But

nobody, from first to last, ever questioned Watson's sincerity.

While lying in prison, he wrote to his wife that "the study of the cause

and remedy for human woe engrossed all his thoughts." The man who

thus wrote while surrounded by some of the lowest criminals of a

metropolitan city had literally no ambition—none, at least, of a vulgar or

even a personal sort. He neither cared for the platform nor sought

reputation as a writer. It was his business and his pride to give

currency to thoughts and opinions which were calculated, he believed, to

improve and elevate mankind. From his shop, almost always in an

obscure thoroughfare in the centre of the publishing trade, most of the

Radical literature of the last generation was distributed over the

country. But the work for which he will be best held in remembrance

is the service he rendered to the cause of the freedom of the press.

The sixth member of the Working Men's Association which

originated the People's Charter was Henry Vincent. And he differed

from his five colleagues in that he was an orator, or at any rate a

speaker who could, as it were, carry his audiences off their feet.

Mr. Vincent, also a printer to trade, very early in life threw himself

into the political agitation which then prevailed in the country. An

earnest and impassioned advocate of the extension of the franchise, he was

only about twenty-four years of age when he joined the committee which

formulated the Charter. Of the movement which followed the

promulgation of the demand for the famous six points, he was, as already

mentioned, designated the Demosthenes. It was in that character that

he denounced the Government of the day as a set of knaves. Using

still stronger language at Newport, Monmouthshire, he was prosecuted and

imprisoned in 1839. The riots in that town, for which Frost,

Williams, and Jones were condemned to death, were alleged at the trial of

the three prisoners to have had for their object, not an armed

insurrection of the people, but the rescue of the Demosthenes of Chartism.

Reference has been made in a previous chapter to the

suspicions that were entertained to account for the marked moderation in

the tone of Vincent's speeches after he came out of Monmouth Gaol.

So far as the change was ascribed to the effect of improper influences, I

have not the least doubt that the imputation was absolutely unwarranted.

Mr. Vincent had grown wiser in prison—that was all. It was no long

time subsequent to his release that he turned his great talents as a

speaker into other channels, though, I believe, he never altered his

opinions as to the justice of the principles he had formerly done so much

to spread abroad. Within a month of his restoration to liberty, he

married a daughter of his old colleague, John Cleave. A man of fine

presence, of powerful voice, of impressive delivery, Henry Vincent became

one of the most popular lecturers of the day. Towards the end of the

sixties he was lecturing in the Music Hall, Newcastle. I went to

hear him. It was a fine performance—splendid as a piece of

declamation, but neither pregnant with thought nor of much value as a

literary effort. But the torrent of words, poured forth with the

skill of a master, brought down thunders of applause. Henry Vincent

died in 1879, save John Temple Leader the last survivor of the Chartist

Fathers.

|

|

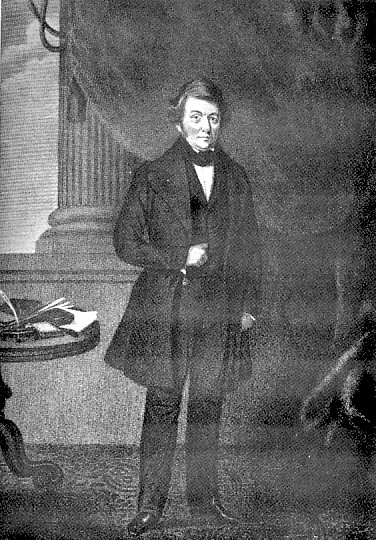

JOHN FROST.

(From a contemporary engraving) |

CHAPTER XX

JOHN FROST AND THE NEWPORT RIOT

ONE of the most stirring events in the history of

Chartism occurred at a very early stage of the struggle. I allude to

the riot at Newport. The People's Charter was adopted at Newhall

Hill, Birmingham, on August 6th, 1838. Within twelve months of that

date Henry Vincent had been arrested in London, brought to Newport, tried

at Monmouth, and sentenced to a year's imprisonment in Monmouth Gaol.

Great was the excitement thoughout Wales, for the prisoner was a prime

favourite in that quarter of the country. There were disturbances in

Newport when he was brought there in custody, and there were disturbances

again when he was brought before the magistrates. The popular

excitement increased from the time of Vincent's conviction on August 2nd,

till it culminated in an armed attack on Newport on November 4th. It

is probable that the explosive character of the people of the Principality

lent itself then, as it has lent itself frequently since, to turbulent

proceedings. Be this as it may, Wales became for the time being the

cockpit of the kingdom. And the name of the chief actor in the

turbulent proceedings which marked the close of 1839 was for many years

honoured and revered by the working people as no other name in England

was.

John Frost, a prosperous linen-draper in the town, had been

Mayor of Newport in 1836. Three years later he had so completely

identified himself with the popular movement that he was one of the

leading figures in the first Chartist Convention. Furthermore, he

exercised great influence over the working people in the Welsh mountains.

Associated with Williams and Jones, he put himself at the head of an

operation which was presumed to have had for its object the overthrow of

the constituted authorities, but which the legal defenders of the

prisoners at the subsequent trial at Monmouth contended had no more

serious design than the rescue of Vincent from prison. Miners and

others, armed with muskets and pitchforks, descended from the mountains

many thousands strong. The seizure of Newport by the Welsh

Chartists, so the agents of the Government alleged, was to have been taken

as a signal for the Chartists of the Midlands to rise in insurrection

also. Whatever the intention, the attempt at Newport was an entire

failure. A great storm in the hills delayed the march of the reputed

insurgents, frustrated the intended surprise, and enabled the authorities

to prepare for the defence of the town. But much blood was shed, and

some dozen lives were lost, during the attack on the Westgate Hotel.

Occupied by the mayor and magistrates, and defended by constables and

soldiers, the hotel was never captured. Marks of the conflict,

however, remained for years afterwards in the wooden pillars which

supported the porch. When the hotel was rebuilt some years ago, the

old pillars, pierced with bullet-holes, were considered of sufficient

historic interest to be preserved in the hall of the new building.

There they will probably remain for many generations to testify to the

tragic scenes that were witnessed around them in 1839.

The leaders of the movement—Frost, Williams, and Jones—were

arrested, tried for high treason, and sentenced to be executed. I

remember my elders telling me as a boy the horrifying detail, that the

condemned men could hear in their cells the noise of the carpenters

erecting the gallows. The extreme sentence, however, was commuted to

transportation for life. As a consequence of these occurrences, John

Frost was regarded as a hero and a martyr throughout the Southern and

Midland Counties. The three companions in adversity were despatched

in a convict hulk with a cargo of other prisoners to a penal colony at the

Antipodes. Fifteen years were spent by them among those unhappy

culprits who in due course helped to found some of the settlements that

have now become flourishing communities of free and honoured citizens.

First a conditional and then a free pardon having been

granted to him and his companions, Frost returned to this country in 1856.

It was a period of public apathy. An attempt was made to give him a

popular reception. But by that time the Chartist movement had

practically died out, Ernest Jones, with scarcely a shirt to his back,

vainly striving to keep the cause alive. The exile had come back to

a country that had almost forgotten him. Still there was a

procession in London. I remember seeing it pass through Fleet

Street. It was a sorry affair. What was worse, it excited the

derision of the shopkeepers who bestowed any notice on it at all.

Two or three hundred people at the most constituted what was intended for

a great democratic demonstration. Poor Frost retired to Stapleton,

near Bristol, whence he contributed to the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle

fragmentary accounts of his experiences and sufferings, and there, nearly

twenty years later, he died at a very advanced age.

But Frost's name and memory are still respected in Newport.

Only a few years ago a later Mayor of Newport was presented with a watch

that had been presented to Mr. Frost at the time he occupied the same

position. And the new owner of the watch, as he informed the

dinner-party at which it was handed to him, was present when the old

Chartist was arrested. "John Frost," he added, "was a very clever

fellow; but unfortunately he got carried away by his feelings until he

lost himself." Though nobody doubts now, even if anybody ever

doubted, that the project of the Welsh Chartists was utterly lacking in

prudence and foresight, the man who led them and shared in their dangers

must at least be credited with generous impulses.

The condition of our penal settlements was at that date

indescribably horrible. Humane ideas in regard to the treatment of

offenders had then hardly even begun to enter the minds of people in

authority. After his return home, Mr. Frost endeavoured to arouse

the attention of the public to the gravity of the ulcerous iniquities we

had established in the southern hemisphere. For this purpose he

published a pamphlet on the subject. Therein he described, as far it

was permissible for any decent person to describe, the infinite horrors of

convict life. I must have written to him about the publication, for

I find a reply in a letter dated December 4th, 1873. "You tell me,

my dear sir," he says, "that you have read my pamphlet with great

interest. I cannot explain to you my feelings when I found the utter

indifference to the state of society among the convicts and the cause

which produced it. I sent this pamphlet to members of both Houses of

Parliament, and the only notice taken was by a member of the House of

Commons, who sent me the pamphlet back again." But the old

Chartist's exposures may have had an effect of which the author was

unaware. Certain it is, at any rate, that the system of

transportation has long since been abolished, and with it have disappeared

the penal settlements themselves. No more will any political or any

other offender suffer tortures such as must have driven to distraction all

but the coarsest and most degraded of the prisoners subjected to it.

I have said that some fragmentary papers of Mr. Frost's were

published in the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. They were the

outcome of a suggestion that the venerable gentleman should write out his

recollections of the exciting events in which he had taken part. "I

have received your letter," he replied on December 4th, 1873, "and shall

feel pleasure in complying with your request." The fragments already

mentioned were the result. Then came the following letter, the

handwriting of which betrayed no sign of age or weakness :—

|

STAPLETON, Dec. 15, 1873.

MY DEAR SIR,—I

have received your letter and the Chronicle which accompanied

it. I have seen no newspaper so full of useful and interesting

matter. I shall be happy if I can to extend the circulation.

I have for years been thinking on the subject of my long and

suffering life, and I feel anxious that the circumstances should be

placed before the public in a way likely to be interesting to the

rising generation.

The plan I propose is this:—In the letter which I sent you I

describe my situation after the escape from Newport, my return to

the town, my apprehension, and my being placed in Monmouth Gaol.

The next letter should contain an account of the trial, the verdict

of the jury, the committal of myself and my companions to the

condemned cell, what took place during our confinement there, our

removal to Chepstow and passage to the York hulk at

Portsmouth, our passage to Van Dieman's Land on the Mandason

convict ship, our passage to the penal settlement at Port Arthur, my

residence there as clerk to the magistrates, my transfer without any

offence to one of the gangs, and other interesting matter connected

with the treatment of the convicts and the terrible effects

resulting from it. Then should follow an account of the

various situations I filled in the colony for fifteen years, my

conditional pardon, the voyage from Hobart Town to Callao, the

voyage from Callao to America, my residence there for twelve months,

my free pardon, and the events from 1856 to 1873.

I will endeavour to render the narrative instructive and

amusing. However, one thing must not be forgotten. I am

in my eighty-ninth year: therefore it can hardly be expected that

the narrative will be such as a younger man would produce. A

few weeks ago I had a terrible fall, which has shaken my mind and

body terribly, and from the effects of which I shall not recover.

My memory has suffered, but not as to past events: these are almost

as fresh as ever. I am also much troubled about my eyes.

I am apprehensive that I shall become a poor blind old man.

May God avert it!

I am, dear sir, respectfully your obedient servant,

JOHN

FROST. |

The fears which crossed Mr. Frost's mind when he penned this

letter were unhappily realised. I heard from him no more. Nor

did any further instalment of the narrative he sketched for himself ever

reach the Chronicle office. Mr. Frost died a few weeks later.

It is much to be regretted that he did not live to complete the task he

had planned. Had he so lived, many inaccurate statements that were

made at his trial would have received authoritative correction, while much

interesting light would have been thrown on a somewhat obscure phase of

Chartist history.

|