|

THE

CENTURY

ILLUSTRATED MONTHLY

MAGAZINE.

November 1881, to April 1882

WHO WERE THE CHARTISTS?

by

W. J. LINTON. |

|

|

|

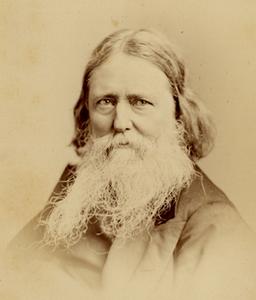

W. J. Linton

(1812-97) |

WHO were the Chartists?—a question to

be first answered by saying what Chartism was. A word of fear in England, from 1837,

for ten to fifteen years onward, of its sound scarcely an echo now remains.

In the Epilogue to Green's "Short History of the English People," these few words—"The

discontent of the poorer classes gave rise, in 1839, to riotous demands for the People's

Charter "—with briefest possible statement of the provisions of the Charter, are all the

information given of an agitation that stirred the whole island. Elsewhere it is spoken of

with the same superciliousness. Historians in general are not generous to the defeated,

nor care to waste their ink on chronicles of the "lower orders."

Two earnest writers, however, have treated the subject as more important: Carlyle in his

"Chartism," Kingsley in his "Alton Locke."

Nobly intentioned books these two, with serious endeavour toward truth; but in vain would one look even

there to learn either what Chartism meant or what manner of man this Chartist was.

Carlyle's writing is blurred by the confusion in the writer's mind between rights and mights: it is the work of a Jeremiah, who ends with Lamentations.

What is to be learned from it is the reason for that prevalent discontent of the poorer classes in which

Chartism had its birth. That is sufficiently exposed by both Carlyle and

Kingsley; but both were by their peculiar views unfitted for correct judgment of the movement or

the men. Having determined in their own minds that the one thing needful for the

masses is good guidance by a wiser few, no matter how appointed (of course presumed

divinely), satisfied that there lies the whole problem of government (Carlyle's aristocracy

of beneficent whip-bearers wanting only, according to Kingsley, the further benefit of

clergy), they not unnaturally concluded that all sound thinkers must be of the same opinion; and were so disenabled from understanding men who, certain that they had

been misgoverned by the aristocracy, and betrayed or neglected by the church (described

by even pious William Cowper as in those Georgian days "a priesthood such as Baal's

was of old"), had come to the opposite conclusion—that it was time for the many to

dethrone the few and take care of themselves. Chartism, indeed, was the plain operation of

democracy pure and simple; not republican, for it asked only popular rule, without thought

of organization of society. It was just a people's protest against absolutism, monarchical or oligarchical—against privilege and

class-legislation: a simple claim for some voice in the appointment of governors or

public servants. It said this: "Before all else, acknowledge men as

men! If you cannot do away with the inequalities of long-continued circumstance, do not aggravate

them by making them the very basis of your law, first rendering us unfit by your partial

regulations, and then keeping us down as a fair consequence of your own unjust prohibiting!"

This principle of Chartism—the looking to the suffrage as the inalienable right of

manhood—had so permeated the minds of Englishmen, owing in a great measure to the

wide circulation of Paine's "Rights of Man" (published in 1791—2), that in 1819 a petition

for universal suffrage, presented to the House of Commons by Major Cartwright, obtained a

million of signatures. The great Whig party had already taken up the same cry.

So early as 1780, the Duke of Richmond introduced a bill into the House of Lords, to give the

right of voting to "every man not contaminated by crime nor incapacitated for want of

reason." Three years later, in his celebrated "Letter to Colonel Sherman," he wrote:

"The subject of Parliamentary reform is that which, of all others, most deserves the attention of the

public, as I conceive it would include every other advantage which a nation can wish; and I have no hesitation

in saying that, from every consideration which I have been able to give this great question, that for many

years has occupied my mind, and from every day's experience to the

present hour, I am more and more convinced that the restoring the right

of voting to every man universally who is not incapacitated by nature

for want of reason, or by law for the commission of crime, is the only

reform that can be effectual and permanent."

At the same date a committee, of which Charles James Fox was chairman, appointed

by the electors of Westminster, recommended annual Parliaments, universal suffrage, equal

voting districts, no property qualification, voting by ballot, and payment of members.

The "Society of Friends of the People," established in 1792 by Charles Grey

(afterward the Earl Grey of the Reform Bill), James Mackintosh, and others, noblemen and members of the House of Commons, followed the

old lead; and the continued agitation resulted, in 1832, in the passing of what is called the

Reform Bill—a reform by which the middle classes were admitted to a share in the government, wherewith the Whig patriots, having come into office, were satisfied.

The working classes were not. Chartism, so long unnamed, but so nursed,

was, nevertheless, born of popular discontent —that "sick discontent," as Carlyle observes,

in which England, almost since the glorious Dutch Revolution, say for a century or more,

lay "writhing powerless on its fever bed, dark, nigh desperate "—the one sole recipe for

its woes, on the advent of a reformed government, a new poor-law and refusal of

outdoor relief. In which connection, under date of 1832, I read of fifteen hundred paupers in

one East London poor-house (that of Spitalfields, the silk weavers' district, many of them

descendants of Huguenots expelled from France) dying off "like rotten sheep" from

mere foulness of the atmosphere. No wild rumour this, but certified by medical authority.

In 1833 Leicester frame-work knitters received, for seventeen hours' work a day, a wage of

five shillings a week—one dollar a week—on which to support a family.

Six years later, wheat being at eighty-three shillings a quarter, the wages of agricultural

labourers were

considered fair when averaging seven shillings a week. But the poor are so improvident.

And in 1840 (here quoting again from Carlyle) we have "half a million of hand-loom

weavers working fifteen hours a day, in perpetual inability to procure thereby enough of

the coarsest food." And beyond all nakedness, hunger, or distress,

"the feeling of injustice that," as the seer remarks, "is insupportable to all men."

Ground enough, one would think, for discontent, for smouldering wrath, for impotent writhings, for even vindictive outrage, if nothing better can be

done. "Sullen, revengeful humour of revolt against the upper classes, decreasing respect

for what their temporal superiors command, decreasing faith in what their spiritual superiors teach, is more and more the universal

spirit of the lower classes." So Carlyle saw in 1840. Some other less heeded men saw it

earlier. Notable among these was Henry Hetherington, who, insomuch as one man can

be credited with the beginning of a popular movement, may be called the founder of

Chartism. He, with William Lovett,

James Watson, and a few others, all working-men, mis-liking secret societies or open violence, and wise enough, too, to perceive the

powerlessness of conspiring against the reigning oppression, sought, rather, to call forth legally

and peaceably such an expression of public opinion as should be sufficient of itself to obtain

redress. From a paper prepared by Hetherington in 1831 arose the "National

Union of the Working Classes," for "protection of working-men in the free disposal of

their labour" (anticipating free trade); to obtain "an

effectual reform in Parliament"

(Whig intentions already seen through); and "the enactment of a wise and comprehensive

code" (to do away with much grievous uncertainty of the law, especially with regard to offenses

of the poorer classes). The principles of the union, drawn up by

Lovett and Watson, as they were the principles which actuated the

framers of the People's Charter, may be worth giving in full:

|

"NATIONAL UNION OF THE WORKING CLASSES.

"We, the working classes of London, declare:

"1. All property (honestly acquired) to be sacred and inviolable.

"2. That all men are born equally free, and have certain natural and inalienable rights.

"3. That governments ought to be founded on those rights; and all laws instituted for the common

benefit in the protection and security of all the people, and not for the particular emolument or advantage of

any single man, family, or set of men.

"4. That all hereditary distinctions of birth are unnatural, and opposed to the equal rights of

man; and therefore ought to be abolished.

"5. That every man of the age of twenty-one years, of sound mind and not tainted by crime, has a

right, either by himself or his representatives, to a free voice in determining the nature of the laws, the

necessity for public contributions, the appropriation of them, their amount, mode of assessment, and

duration.

"6. That in order to secure the unbiased choice of proper persons for representatives, the mode of voting

should be by ballot; that intellectual fitness and moral worth, and not property, should be the qualification

for representatives; and that the duration of Parliament should be but for one year.

"7. We declare these principles to be essential to our protection as working-men, and the only sure

guarantees for the securing to us the proceeds of our labour; and that we

will never be satisfied with the enactment of any law or laws which does

not recognize the rights enumerated in this declaration."

|

In 1837, the London Working-men's Association held a conference with the few liberal

members of the House of Commons, the result of which was the appointment of a

committee of twelve persons to draw up a bill to be proposed to Parliament.

The committee consisted of Daniel O'Connell, M. P., John Arthur Roebuck, M. P., John Temple Leader,

M. P., Charles Hindley, M. P., Colonel T. Perronet Thompson, M. P., William Sharman

Crawford, M. P.; and, as deputies of the Working-men's Association, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, James Watson, Richard

Moore, William Lovett, and Henry Vincent. The work of writing fell to Lovett, who was

aided on legal points by Roebuck, who wrote the preamble. Carefully considered afterward, clause by clause, in the London Association,

and approved by associations throughout the country, the perfected draft came at last

before the public as the People's Charter—the outline of an act to provide for the just

representation of the people of Great Britain and Ireland in the Commons' House of Parliament, embracing the principles of universal

suffrage, no property qualification (for members), annual Parliaments, equal representation, payment of members, and vote by ballot.

The principles of this outlined act were, it will be seen, precisely those which, in 1780,

Charles James Fox had recommended to the electors of Westminster, which the leaders of

the great Whig party, not then in office, had deemed the only reform that could be

effectual or permanent. Now, fifty years later, this reform, asked for by the people

themselves and its practicability made manifest, was officially declared to be

revolutionary; and the very name of the People's Charter helped the opponents to a nickname.

Chartist (one believing in old Whig principles, and discontented because these principles were

abandoned by the party in power) became a word of reproach. Liberal politicians of the

Brougham and Burdett, and even of the Russell temper, would have none of it.

Such was the origin, such were the principles, of Chartism. And what sort of men were

the Chartists? "Insatiable wild beasts," said, almost unanimously, the contemporary liberal

and illiberal press. "Discontented rioters of the poorer classes," writes the more authoritative

historian. Yet the rioting was not extensive. Some there was: unimportant writhings, chiefly

of starving and ignorant agricultural labourers, stirred out of their accustomed apathy by the

falling of a few hasty and unconsidered words on the heaped-up dry fuel of their

misery; now and then a "riot" of less ignorant and more excitable mechanics—for the most part

provoked by police brutality, or the secret works of Government spies (as Cobbett, then

in Parliament, conclusively proved); this was all set down to Chartists, however innocent the

rioters of any thought of political action or concern with Chartism.

An abortive attempt to liberate a prisoner, in which the only blood shed was that of the would-be liberators, was

the one important item of wild-beastliness. And "insatiable" was an unhappy term for

men toward whose satisfaction nothing except the most liberal abuse was offered.

But Chartism (its objects were so just) meant rebuke to those in authority, and insofar was essentially

repugnant to the taste of the higher classes; wherefore, to borrow late slang, it was

"bad form" to associate or sympathize with those low fellows, the Chartists.

"What had mere working-men to do with the nation's government?

Let them leave that to their betters!" It was a time of reaction.

The current generation had not outgrown the scare of the French Revolution.

The "Young England" of a dreamily benevolent conservatism (Carlyle interpreted by Benjamin Disraeli—Genesis xliii. 34) and the Christian socialism of

Professor Maurice were not yet glimmering in the dawn. Respectable writers, like the class

for which they wrote, kept aloof from "the great unwashed "—public baths being not yet

numerous in England, and private not too frequent. Leigh Hunt alone was generous

enough to praise the public addresses of the Working-men's Association;

and Carlyle and Kingsley (Shelley's "Masque of Anarchy" belongs to

earlier days) stand as exceptions to the rule of neglect—they too, as I

have said, debarred from acquaintance with the men. I, being with

these Chartists through nearly the whole of the contest, in close

companionship with some of the leaders, had opportunity of knowing what

they were. Is it too soon to say?

Among them were some of the noblest, the most disinterested, the bravest, ay, and the

most intelligent men in England. I am not prouder of Mazzini's friendship, of the

friendship of some others whom England consents to honor, than I am of the friendship of these

men "of the poorer classes"—only working-men, my Chartist comrades.

Let me recall one: Cornelius George Harding, Chartist and gentleman:

|

"As true old Chaucer sang to us, so many years

ago,

He is the gentlest man who dares the gentlest deeds

to do:

However rude his birth or state, however low his

place,

He is the gentleman whose life right gentle thought

doth grace." |

This one was lowly placed, and of the poorest: a self-taught, loving, fragile lad, a

toiler from his childhood, and from boyhood (his father dead) the sole support of his

mother. Conscientious, diligent, studious, esteemed by his employers, loved by his

companions; public-spirited, unobtrusive, zealous, brave, devoted; gentle as a woman, pure as a girl, irreproachable as a

saint; never sparing himself when work was to be done as a republican missionary, or help was needed for a

friend; dying at the age of twenty-seven, of consumption, overwork, and that fever of the

enthusiast, the sword outwearing the too slender sheath:—I have known no more

beautifully natured man than this poor Chartist.

William Lovett was of the same gentle nature. Only a poor cabinet-maker—poor his life through, for he gave his days to the people

's service and took no reward.

A true patriot: history records none truer. Not self-seeking, nor ambitious, save of the fame of

good deeds. Not a strong man, but essentially good, of kindliest nature, clean, just, intelligent, peace-loving, although

"seditious"; and, if not strong, unflinching. What epitaph or praise needs be beyond his title—the

framer of the People's Charter? A charter greater than the "Great Charter," which did

not recognize the workman as a man. Another of history's riotous wild

beasts! This one would not have trodden upon a worm. Cornish by birth, born in

1800, at Newlyn,

a little fishing-town near Penzance, his father the captain of a small trading-vessel, drowned

at sea before the boy saw light, he was carefully brought up by his mother, a woman of

much character, intelligence, and piety, getting such schooling as was to be had by the

poorer classes in those days. All that was supposed sufficient to train up a child in quiet

and respectful ways was his: his mother's example and precept, Dr. Watts's divine songs,

the strict Methodist connection; but other influences could not be shut out from even

the child's simplicity. It was war-time. "Deeply engraven on the memory of my

boyhood," he writes in his autobiography ("Life and Struggles of William Lovett, in his pursuit of bread, knowledge, and freedom"),

were "the apprehensions and alarms amongst the inhabitants of our town regarding the

'press—gang.' The cry that ' the press—gang was coming,' was sufficient to cause all the

young and eligible men of the town to flock up to the hills and away to the country as fast as

possible, and to hide themselves in all manner of places till the danger was supposed to

be over. It was not always, however, that the road to the country was open to them, for the

authorities sometimes arranged that a troop of light-horse should be at hand to cut off

their retreat when the press-gang landed. Then might the soldiers be seen with drawn

swords, riding down the poor fishermen, often through fields of standing corn where they

had sought to hide themselves, while the press-gang were engaged in diligently

searching every house in order to secure their victims. In this way, as well as out of their boats

at sea, were great numbers taken away and many of them never heard of by their relations."

Such scenes probably lit the first sparks of his natural indignation against wrong.

When old enough, he was apprenticed to a rope-maker; afterward, rope-making being slack,

the war being over, he tried fishing, but could not do away with

seasickness; then, being of age, and not without considerable mechanical

ingenuity, he went to London to seek employment as a self-taught carpenter.

For a time he suffered the usual course of privation, but persevered; and, at first refused admission

into the Cabinet-makers' Society because he had not served an apprenticeship, he at last

was chosen president of the society. Anxious always to improve, strict in conduct,

temperate in his habits, he spared money for books, cheating his stomach with scant dinners,

joined the Mechanics' Institute, then new, attended lectures, etc. He tells an amusing

story—characteristic, too—of once returning from a lecture with Sir Richard Phillips, the

book-seller and author, who had some theory of gravitation in opposition to the Newtonian.

Glad, I suppose, to get an intelligent listener, the scientific book-seller led him round and

round St. Paul's church-yard in the moonlight, to broach his peculiar views, explaining them

occasionally by diagrams chalked on the shop-shutters, as need occurred.

In 1826 he married, making his own house-furniture—which furniture was seized five years later because he refused either to serve in the militia

or to pay the fine for a substitute,—his plea "no vote, no musket."

His daring conduct was not without effect. Public excitement led to discussion in Parliament, to exposure of the

system in practice; and no drawing for the militia has taken place from that time.

|

|

|

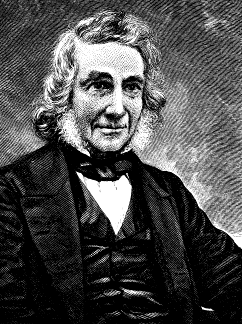

WILLIAM LOVETT |

By this he had become acquainted with the various endeavours then making for the amelioration of the condition of working-men, had

joined the "First London Co-operative Trading Association" (one of several associations

for the same purpose—the first established at Brighton in 1828), and was becoming proficient in politics.

So early as 1829, he drew up a petition for opening the British Museum on Sundays.

He was active also in the agitation for a free and unstamped press, begun

by Hetherington in 1830. Of his action, with Hetherington and Watson, in the

formation of the Union of the Working Classes, and the formation of the People's Charter, I

have already spoken. The addresses of the London Working-men's Association were, I

believe, his writing. I note one in especial, an address to the working-men of Belgium

on occasion of the imprisonment of one Jacob Katz for calling a meeting of his fellow-workmen in Brussels, to discuss their

grievances—the first public essay to break down the king-fostered antipathy between the

peoples. When a convention of delegates from all parts of the country met in London,

in 1839, to prepare and to procure signatures to a national petition for the Charter, Lovett

was chosen secretary. The frightened Government began to make arrests, to give opportunity for them also by needless provocation

of the people. An outrageous attack by the police, in July, 1839, on a peaceable meeting in

the Bull-ring, Birmingham, being condemned by this Convention, Lovett, as their secretary,

was arrested, and, with another member of

the Convention, John Collins, who had taken

the condemnatory resolutions to the printer,

was convicted of a "seditious libel," for

which they suffered twelve months' imprisonment in Warwick Gaol.

Unconverted, he

came out of prison. After the failure of

Chartism, the rest of his life was given mainly

to educational movements; and two educational works by him, "Elementary Anatomy

and Physiology," and "Social and Political

Morality," have been highly spoken of. There was no lack of the

old-time earnest philanthropic spirit when I last saw the old man, in

London, in the beginning of 1873.

No rioter he, but simply a good citizen, fully

impressed with his duty as a man, benevolent and earnest.

|

|

|

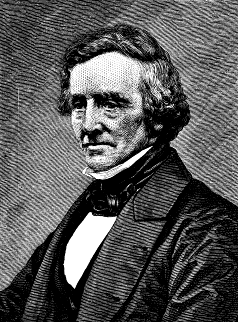

HENRY

HETHERINGTON |

|

"None more single-minded, few so brave, so generous as he. The most chivalrous of our party. He

could neglect his own interests (by no means a virtue,

but there is never lack of rebukers for all failings of

that kind), but he never did and never could neglect

his duty to the cause be bad embraced, to the principles he had avowed. There was no notoriety-hunting

in him—as, indeed, so mean a passion has no place in

any true man. And he was of the truest. He would

toil in any unnoticeable good work toward human

freedom, in any forlorn hope, or even, when he saw

that justice was with them, for men who were not of

his party, as cheerfully and vigorously as most other

men will labor for money, or fame, or respectability.

He was a real man—one of that select and glorious

company of those who are completely in earnest.

His principles were not kept in the pocket of a Sunday coat (I don't know that he always had a Sunday

change of any sort); but were to him the daily light

which led his steps. If strife and wrath lay in his

path, it was seldom from any fault of his; for though

hasty, as a man of impulsive nature and chafed by

some heavy afflictions, he was not intolerant, nor

quarrelsome, nor vindictive. Men who did not know

him have called him violent. He was, as said before,

hasty and impetuous, but utterly without malice; and he would not have

harmed his worst enemy, though, in truth, he heartily detested

tyranny and tyrants. One of the truest and bravest of the

warm-hearted." |

With Hetherington I was closely associated: editing for him in, I think,

1841—2, the "Odd-Fellow" (so called because it was, to some extent, the

organ of the societies of that name), a weekly unstamped broad sheet,

for which I also wrote the political leaders. I had acted with him in

Chartist matters for some years before. Of him, I may repeat some

few of words written to be spoken over his grave, as I was too far away

to attend the burial.

Born in London, in 1792, he was brought up as a printer; afterward in business as a

book-seller and news-agent. One of the founders, with Doctor Birkbeck, of the first

Mechanics' Institute, he was active in every movement for the instruction and moral

elevation, as well as the political and social enfranchisement, of the working classes.

For four years, 1831—4, he led the fight for a

free press,—fined, imprisoned, hunted as an

outlaw, but at last defeating the Government,

obtaining from a special jury the

verdict that his "Poor Man's Guardian,"

for which he and others had suffered, was a

strictly legal publication. How severe the

fight, may be known from the mere fact that

over five hundred persons, during those four

years, were imprisoned for selling the strictly

legal but too radical publications. These

prisoners and their families had all to be

supported by those who sympathized with

the movement, mostly working-men, some few

nobly exceptional men of station and influence giving generous help. Chief of these

last was Julian Hibbert, the chairman and

treasurer of the "Victim Fund," a man who,

dying sadly, asked that no record might

remain of him. "I ask only silence." Too

late now to dispute his wish. All that can be

said of him is that, a man of "family," some

means, high culture, and most generous

nature, he was the chief prop of Hetherington's great endeavour. Not unlike Shelley

his portrait shows him; what I have heard of his character continues the resemblance.

Obnoxious to the Government on account

of his determined resistance to the hinderances

of a free press, Hetherington was a marked

man also as a prominent Chartist. In the Convention he sat as delegate for London and for

Stockport. A fervid speaker, ready and clear,

humorous or sarcastic as occasion required,

often eloquent, he was very popular; yet he

was sufficiently master of himself to escape

prosecution in the day of arrests for "sedition." He had, perhaps, had his share of

punishment for the unstamped. Not quite, it was

thought by the Government, which in 1841

obtained a conviction against him for publishing (rather for selling in the ordinary

way of business, he not being the publisher) certain "Letters to the Clergy." He defended himself, and so eloquently as to call forth a warm

eulogy from Chief Justice Denman; and,

technically guilty, escaped with four months'

imprisonment in a debtor's prison, the lightest

punishment on record for so heinous an offense. The champion of a free and untaxed

press is a proper title for Henry Hetherington. He died of

cholera, in 1849. Outside of comradeship, some evidence of his

worth may be found in the following resolution:

|

"We, the Directors of the Poor of the Parish of St.

Pancras, at present assembled, sincerely deplore the

loss of our much respected friend Mr. Henry Hetherington; and cannot allow the earliest opportunity to

pass without offering this poor tribute to his worth,

talent, energy, urbanity, and zeal. In him the poor,

and more especially the infant, have lost a powerful

advocate, the Directors a valuable coadjutor, the rate-payers an economical distributor of their funds, and

mankind a sincere philanthropist."—Passed unanimously at a

meeting of the Board of Directors, August

21, 1849. |

|

|

|

|

|

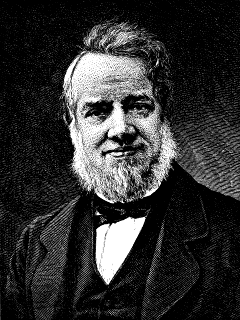

JAMES

WATSON |

Close to Hetherington, their public life

coincident, their friendship "beyond the love

of women," was James Watson; he, too, a

working-man, some seven years younger than

his friend, born at Malton in Yorkshire, in

1799, his father a day-labourer of "the poorer class," who died when James was about a

year old. Like Lovett, he owed everything

in early life to his mother. At twelve years

of age apprenticed to a clergyman (no unusual

thing in those days) to learn field labour,

house-service, etc.; after that employed as

warehouseman at Leeds; then book-seller's shopman in London; store-keeper for a cooperative association; compositor and

publisher; he worked his steady way to independence, helped by a wife worthy of

him; and

was able in his declining years, in spite of prison hinderances and long devotion of his

energies to the public service, to enjoy some

years of well-earned ease before his death, in 1874. Of him, my very dear friend,—I knew

him intimately for nearly forty years,—how

shall I speak impartially? I can but describe

him as I knew him. A man of the old Puritan type, such a man (though neither poet nor

statesman) as Milton or Vane would have

held dear. A man most single-hearted, profoundly religious (certainly of no denomination), simple, clear-thoughted, earnest, trusty,

and inflexible. Not to be daunted (he endured three long imprisonments for selling

publications—now freely sold— disapproved of by the then Government), not to be enticed

by pleasure. A plain, self-taught, good man,

with all the virtues of his class—the honest

working class of which England is justly

proud, and besides that the indomitable spirit

of a Wickliffe, and such gentleness withal

as that of him whom Shelley characterized as

"gentlest of the wise"—Leigh Hunt. Happily married, though with no family, yet fond

of children, and loved by every child that

came near him; a man of kindliest affections,

but severe in his self-devotion to the good of

his fellows and of humanity, his exertions as a

publisher and active politician, public speaker

and teacher, given freely, and his example

consecrated to the bettering of mankind, of

his own class to begin with. A close thinker,

very thoughtful, yet practical, prudent and

sure in action, wise in council, of unblamable

life, austere in himself, and if severely just yet

never cruel in his judgments, severe only

because, though he might pity the evil-doer,

he could have no sympathy with evil. Habitually grave, for life was serious, and suffering rife around him, yet sedate and cheerful.

A man of the Cromwell period, a gentler Ironside. A man whom all who had to do with

esteemed and trusted, whom all who knew

loved. Perfectly healthy-souled, whole! I

call him a working-man, for I have always

looked upon him as such, though in most of

his life a tradesman, a book-seller. But his

business was for daily bread, not profit—his

only means of livelihood at last, and at first

chosen with a view to supply his fellow workmen with political and social information else

beyond their reach. If the sale of a book

supplied his current wants, the modest fare

and surroundings of a decent mechanic, he

was content. If profit came, it went to bring

out some new work which might be of advantage to his class. His first capital came

from Julian Hibbert, who had nursed him

through a severe sickness, who saw what the man was, and who in his will left him four

hundred and fifty guineas, in token of his

esteem and friendship. His first publications

were set up by himself, and with his own

hands printed on a press—the gift, with the types, of Julian Hibbert.

He published nothing

merely for profit. His shop was his church. It was only by dint of constant economy and

self-denial that he saved enough to provide a

small annuity for his old age, with after provision for his wife. In his later years of

comparative retirement, still interested, if not so

active as before, in political matters, his lodging (two rooms only) was in the

neighbourhood

of the Crystal Palace, in order that he might

almost daily study the works of art and manufacture there exhibited, and enjoy the music.

Looking back upon his life, knowing of it

from its beginning to its close, I find it flawless. I cannot detect a single stain upon the

record of threescore and fifteen years.

Not unworthy to be also his friend was

Richard Moore, by profession a carver, not

without talent to have commanded wealth,

had he cared for wealth as he cared for the

public service. His name is not prominent in

histories, yet to him, with Hetherington and

Watson, more than to any other men, we are

indebted for a free press in England. What labour was involved in that, even after Hetherington's defeat of the Government and the

consequent reduction of the tax on newspapers from fourpence to one penny each, may

be learned from my stating that the committee appointed by the "People's Charter

Union" as the "Newspaper (penny) Stamp Abolition Committee" (afterward committee

of the "Association for Repeal of all the

Taxes on Knowledge," of which Moore was

unpaid permanent chairman, and C. Dobson Collet, another Chartist, unpaid secretary,

from its formation, in 1849, to the abolition

of the duty on paper, in 1861) had to meet

four hundred and seventy-three times. To

give other phases of his career would be but

to repeat the course of his comrades. In all that Hetherington, Lovett, and Watson did,

Moore stood beside them. For forty years

an active politician, without office or reward. No man had an ill word of him.

Another

Chartist whose life was without stain, to be

duly honoured in coming republican days, when men shall proudly record

the earlier struggles of the people. He died in 1878, aged

sixty-eight. From one of several obituary notices, all of the same

character, I borrow the following:

|

|

|

"There was something singularly earnest, gentle, and chivalrous in his character. Few men have

enjoyed the confidence and friendship of leading politicians more than he.

Cobden, Milner Gibson, Mazzini,

and all the prominent English radicals and liberal

exiles, he could reckon among his friends. I do not

suppose that, for the better part of half a century, during which he has served the public, he ever received

the value of a day's wages. The purity of his life was

only equalled by his disinterestedness." |

|

|

RICHARD MOORE |

|

|

From my own personal knowledge I know this to be the truth.

With the other two framers of the People's Charter,

Vincent and Cleave, I had but slight acquaintance. Vincent, — originally, I

believe, a compositor, an enthusiastic and eloquent speaker, — on the failure of Chartism,

took to general lecturing; he was popular

and successful, and was heard also in this

country. Cleave, a book-seller (he had been

at sea in his youth), was active in the battle

of the unstamped as well as for the Charter.

Rude and bluff in manner, he had, says Lovett, who knew him better than I did,

"a

warm and generous heart; always ready to

aid the good cause, and to lend a helping

hand to the extent of his means. He laboured

hard and made great sacrifices.

|

|

JOHN

FROST |

Not unremembered be John Frost, the

Newport linen-draper. He had been mayor

of Newport, too, so hardly of seditious tendencies. A man of mature age, over fifty,

when he led that mad attempt to take Vincent

out of prison. A respectable, worthy, well-esteemed, quiet man, with nothing to gain

but everything to lose by his insurgency, like

William Smith O'Brien, impelled solely by a

chivalrous sense of public duty. I care not if

it be called Quixotic. I would, indeed, there

were not so few of men so earnest. His followers—say rather those who chose him for

their leader—were hot-headed Welsh miners,

excited by braggart talk of probable outbreaks elsewhere. This "rebellion" put down

by a few soldiers, Frost and two companions,

Williams and Jones, were tried for high treason, convicted, of course, and, left for execution, would certainly have been hanged but for

the urgency of petitions in their favour and the

ill omen of the appearance of an executioner at

the young Queen's wedding; so the sentence

was commuted to transportation for life—to

any man of wholesome, decent habits, a punishment severer than death.

Horrible beyond

telling was the condition of our penal settlements in those days. After some years the

convict's sufferings were lightened, and, but a

few years ago, the remainder of his sentence

remitted, Frost returned from Australia to

die in England in 1877—hale, hearty-looking old man of ninety-three, unchanged in his

opinions.

|

|

|

THOMAS

COOPER |

More heat was in impulsive Thomas Cooper, the poor

shoe-maker, who beguiled captivity by writing the "Purgatory of

Suicides; a

Prison Rhyme," in ten books, which, with

part of an historical romance, a series of simple tales, and a small Hebrew guide, were the

fruits of two years and eleven weeks' confinement in Stafford Gaol.

The author speaks of

himself as one "who bent over the last and

wielded the awl till three-and-twenty, — struggling amidst weak health and deprivation

to acquire a knowledge of languages, — and

whose experience in after life was at first limited to the humble sphere of a school-master,

and never enlarged beyond that of a laborious

worker on a newspaper." His imprisonment

was for "seditious conspiracy "—a speech

made by him to some colliers on strike having been followed, without his purpose or his

knowledge, by riot. He stood two trials—first for taking part in the riot, when he proved

an alibi; the second for conspiring to produce the riot, for which, after a ten days' trial, he

pleading for himself, he was convicted. To return to his poem. Noteworthy on account

of the circumstances under which it was produced, it also deserves credit for

itself: a poem

well conceived, wrought out with no ordinary amount of power, and not wanting in poetic imagination. A few lines may suffice to show its form,—lines of which

Ebenezer Elliott, the

"Corn-law Rhymer," would not have been ashamed. The opening of the third

book:

|

"Hail, glorious Sun!

Great exorcist, that bringest up the train

Of childhood's joyance and youth's dazzling dreams

From the heart's sepulchre, until again

I live in ecstasy 'mid woods and streams

And golden flowers that laugh while kiss'd by thy

bright beams.

"Ay! once more, mirror'd in the silver Trent,

Thy noontide majesty I think I view,

With boyish wonder; or, till drowsed and spent

With eagerness, peer up the vaulted blue

With shaded eyes, watching the lark pursue

Her dizzy flight; then on a fragrant bed

Of meadow sweets, still sprent with morning dew,

Dream how the heavenly chambers overhead

With steps of grace and joy the holy angels tread.

|

Hasty as Cooper was, a man of warm feelings and some sensitiveness of temper, he was as

kind-hearted as hasty, a "wild beast" whose soul was full of good-will toward men, guileless as a child, and with all a poet's love of the simple loveliness of nature. He was a man, too, of good sense and

thought; his "Letters to Young Men," written in such English as Cobbett wrote, are of the same solid stuff.

He was also an eloquent speaker. I believe he is now a preacher of some dissenting persuasion.

I do not recollect if he was a Chartist before he was graduated at

Stafford; but I know he was heartily and actively with us after he came thence.

I was well acquainted with and much esteemed him.

Some words I must spare for Thomas Powell, whom I knew when he was a shop-man with his friend

Hetherington. He, a fiery little Welshman, had more of the rebel in him, albeit a sensible man, clever and wary—a man who might have led an insurrection.

He had twelve months in prison, not for inciting, but for seditious staying of action—so

proving that he had influence beyond that of the mere inciter. What quality he had, how

trusted and trustworthy he was, one little anecdote will show. When Hetherington was indicted for selling Haslam's

"Letters to the Clergy," he made up his mind to suffer imprisonment rather than pay a fine.

He had been mulcted enough in former days, and this time "they should take it out of his bones."

A friend (Chartist also, Hugh Williams, a Carmarthen lawyer, Cobden's brother-in-law) lent him a sum sufficient to purchase his whole property, books, presses, household stuff, etc.

This handed to Powell, the property valued by a

broker to make the sale legal, Powell bought

all, paying the ready money for it. Hetherington returned his friend's loan, and coming

out of prison (he was not fined) received back

his own from Powell. There were no vouchers or receipts passed to vitiate the transaction.

So these Chartists trusted one another. A restless, not an irritable man, on the

failure of Chartism, Powell took a party of emigrants to South America.

That enterprise also

failed. He died soon after, in Trinidad.

The men I have spoken of are hardly to

be dismissed as rioters, nor will mere personal

discontent appear to be the motor of their

lives. I have said the rioting with which

Chartists are credited by history was not

extensive, however the number of Government prosecutions may appear to contradict

me. I note that all of these, my friends and

fellow-workers, except young Harding and

Moore, were what a liberal Home Secretary

would classify as convicts: convicted of offenses against existing powers, punished

with imprisonment, not for crime, but, as good

old Lamennais has it in his "Words of a

Believer," for having wished to serve their

fellows. The Chartist convict list (how much

of it of the same character?) was indeed a

lengthy one, deductions made for matters

which had no concern with Chartism. One

Vernon, of whom I recall nothing but his

sentence, had eighteen months of jail. James Bronterre O'Brien, an Irishman, one of

the most able among us, some while editor of

Hetherington's "Poor Man's Guardian," had

eighteen months. Sharpe, Williams, and Holberry died in prison. Cuffey, Ellis, Lacy,

Dowling, Fay, and Mullins were transported.

I know not if any of them ever returned.

Ernest Jones, a later Chartist,—a man of what

is called good family, a barrister, and with

some poetical talent,—had two years, with exceptionally harsh treatment. Feargus O'Connor (an honester but less capable O'Connell),

whose demagogic egotism did more than

anything else to discredit, mislead, and ruin

the cause, proved his sincerity by twelve

months in York Castle. And my friend

George Julian Harney (resident in the

United States for the last seventeen years,

the only survivor of the fifty-three members

of the Chartist Convention of 1839), three

times imprisoned for selling unstamped newspapers, had his share of numerous occasional

arrests. Fifty-seven men were at one time

on trial together, the majority defending

themselves, Harney leading, and O'Connor closing the defence. Arrests, convictions,

punishments were plentiful enough. Proving what? For sample of what might constitute offense: four

labouring men in Lancashire, in

1831, sentenced to twelve months' imprisonment for unlawfully assembling on a Sunday.

But I am not writing a history of Chartism.

I am speaking here of Chartists. Convicts

as they were (so were Eliot, Vane, Sidney,

and one Russell), may we not also call them

martyrs, sufferers for a righteous cause?

Few words may sum up the history: Mistakes, discouragement, dissensions, confusion,

desertions, apathy, and despair. Is it not the

story of almost all popular, of all first, attempts?

Matters not to blame the blundering bluster

of O'Connor, to condemn the impolicy of

accepting recruits from among the trading

politicians who join but to betray. Two things insured our failure: we were not equal to our

task, and also we were before our time. Note

yet a third: there was no organization toward

action. Our work was a protest; we had no

plan beyond that. Others will learn wisdom from our failings; and the time will grow.

I have picked my men for praise—the

best I knew, the leaders of the earlier movement, most of them members of the

London associations. Other good men I could

name, if not many of that stamp or height of

worthiness, both in London and in the provinces. I have not taken these as exceptions.

All the rest were not "wild beasts." One million two hundred and eighty-three thousand

persons signed the first Chartist petition,

presented to the House of Commons on the 4th of June, 1839. Surely good and bad

were in that number. But though there were

no record of personal worth, this would be

no less true: That since the days when

the chief of English gentlemen endeavoured to

found a religious commonwealth, failing not

from lack of earnestness, bravery, or wisest

counsel, but because they, too, were before

their time, and because they would build upon

an impossible foundation,—the letter of an

obsolete law,—no nobler or more righteous

thought has stirred the soul of Britain than stirred it in this misunderstood attempt of

working-men to raise the character of British

life by lifting law and life to the ground of

natural right,—the only basis of a nation. Pale as that star of Chartism showed in the

horizon, lingeringly as the clouds yet obscuring it may pass away, I yet dare to think

that it heralded the morning of the Republic. |

|

___________________________ |

|

Note:

I am glad to be able to give portraits of Hetherington and Watson (though Hetherington's is from a poor

drawing, not doing him justice) as they were in the most active period of their lives.

The other portraits are all from

photographs taken at an advanced age, but may show how time can render even

"rioters"

venerable-looking and humanize the traits of the most unsatisfactory of "wild beasts."

Cooper writes to the friend who obtained

for me his portrait: "I am in my seventy-seventh year. I enclose you a photograph taken only a month ago,

so Linton will have the latest likeness." Frost's photograph was taken on his return to England, after the

remission of his convict sentence.

At Ayr, in Scotland, public subscription has placed a statue

to the memory of one of these "convicts,"

Doctor John Taylor (born at Newark-castle, Ayrshire, 1805, died in 1842), delegate from Paisley to the Chartist

Convention of 1839. I did not know him personally, but the inscription underneath the statue, from those

who did know him, may be sufficient attestation of his worth. The legend runs

thus: "In commemoration

of his virtues as a man and his services as a reformer. Professionally, he was alike the poor man's generous

friend and physician; politically, he was the eloquent and unflinching advocate of the people's

cause, freely sacrificing health, means, social status, and even personal

liberty, to the advancement of measures then considered extreme, but now

acknowledged to be essential to the well-being of the state."

Watson, also, over the grave at Norwood, has his memorial stone

— a plain granite obelisk, with the following words: "James Watson,

1874; erected by a few friends, as a token of regard for his integrity of

character and his brave efforts to secure the right of free speech and a

free and unstamped press."

Convicted of patriotism!

|

|