|

――――♦――――

|

|

|

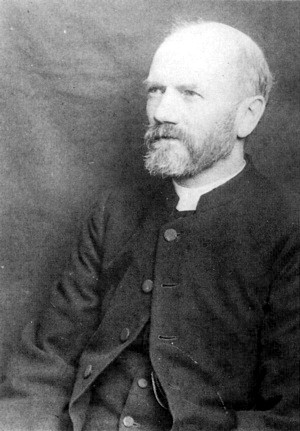

REV. FREDERICK

R. SMITH.

Taken at Manchester Road Wesleyan Church,

Burnley, 1914.

Photo: courtesy Burnley Reference

Library. |

BY the close of the 19th

Century, it appears, there was no serious ecclesiastical objection to a Wesleyan

Methodist minister writing novels, although adopting a pseudonym and a low

public profile as an author of popular light fiction were probably considered prudent.

This, I think, accounts for the

comparative dearth of information on the life of "JOHN

ACKWORTH", the pen name of the

REVEREND FREDERICK ROBERT

SMITH (1854-1917),

author of many delightful and, in their day, highly popular tales of

Lancashire working-class folk.

|

An old lady in Burnley described him:

"He was a little man with red

hair and a little pointed beard. You could just see him over the top

of the pulpit. He was a very good preacher". He had

"theatrical

mannerisms," while preaching. He would shout but lead

to the shout with a kind of crooning sound (sounds like a siren

song).

A description of Ackworth the preacher. |

What information I have been able to glean about Ackworth the man

(I suspect that the reverend gentleman would have

preferred to be addressed by his nom de plume in a literary context)

I have extracted in the main from several brief obituaries, from

material supplied by the Burnley and Salford reference libraries and from a

biographic sketch, "Clogshop Chronicles, a Victorian Best-seller", by Stanley Wood published in

The Dalesman

(October, 1979).

"John Ackworth" was born at Snaith, Humberside,

on 18th April 1854; as a writer he thus shares with

Samuel Laycock the unusual distinction of being a

Yorkshireman who became a notable author in the Lancashire

dialect, then spoken in various flavours by working-class folk throughout the greater

part of the

county (the Liverpool area excepted) but now, together with the old

industries and lifestyles, almost extinct.

Coming from a family of preachers ― his

great-grandfather, his two grandfathers, his father, and seven

uncles were in the ministry, and at least one brother ― it was to the

Wesleyan college at Headingley, Leeds, that Ackworth went to undertake his theological training

from which he emerged in 1879 to commence his ministry in the Castletown

circuit on the Isle of Man. In 1882 Ackworth married Annie

Bradley of Stockport; they were to have 4 sons and 3 Daughters.

Ackworth's first essays in writing were in The Isle of Man

Examiner, a fact he later acknowledged in The Methodist

Magazine, but it was in 1896 that he achieved great success

with his first book, "Clog Shop

Chronicles", a collection of Methodist tales cast in a

rural setting and featuring now long-forgotten scenes of Lancashire

working-class life and dialect humour ―

|

He was the village knocker-up, and

went his daily rounds with unfailing regularity every

morning, except Sunday, between the hours of four and

six. Over his shoulder he carried a long, light pole,

with wire prongs at the end, with which he used to

rattle at the bedroom windows of the sleepy factory

hands until he received some signal from within that he

had been heard.

Though employed and paid by the "hands," Jethro

regarded himself as representing the masters' interests,

and if a post was unoccupied or a loom "untented" when

the engine started at six o'clock, Jethro felt that it

was a reflection on his professional ability, and was

ashamed and hurt.

This doubtless accounted for the extraordinary zeal

which the old man put into his work. The knocker-up was

expected to go and knock a second time a few minutes

before six to stir up any drowsy one who might,

peradventure, have fallen asleep again, and into this

second round, which was to many the real signal for

rising, Jethro put all his resources. Not only the

windows but the doors were assailed, and in addition he

would give a word of exhortation in his thin piping

voice―

"Bob! Dust ye'r? It's five minutes to six! Ger

up, tha lazy haand (hound). If tha dusn't ger up Aw'll

come an poo' thi aat o' bed."

At the next call he would drop into a coaxing tone-

"Lizer! Jinny! Come, wenches! You'll ne'er ha'

breet een (eyes) if yo' lie i' bed like that."

Beckside's 'Knocker-up' . . . .

Clog Shop Chronicles.

|

__________

"GET

UP!" |

|

"GET

UP!"

the caller calls, "Get up!"

And in the dead of night,

To win the bairns their bite and

sup,

I rise a weary wight.

My flannel dudden donn'd, thrice

o'er

My birds are kiss'd, and then

I with a whistle shut the door

I may not ope again.

By

Joseph Skipsey |

|

|

. . . Such everyday events — set in the mythical cotton-mill villages of Beckside,

Scowcroft, Bramwell, etc., and painted by Ackworth in his charming

idylls — have long since followed the Lancashire cotton

industry, the dialect, and Methodist chapel life into virtual

oblivion. Samuel Smiles,

writing during the Victorian era (ca. 1860) on the history of our developing

road system, suggests that improved communications — or lessening

isolation — was an important factor in the disappearance of our

local dialects and customs, such as those on which Ackworth's tales

are based:

"The imperfect

communication existing between districts had the effect of

perpetuating numerous local dialects, local prejudices, and local

customs, which survive to a certain extent to this day; though they

are rapidly disappearing, to the regret of many, under the influence

of improved facilities for travelling. Every village had its

witches, sometimes of different sorts, and there was scarcely an old

house but had its white lady or moaning old man with a long beard.

There were ghosts in the fens which walked on stilts, while the

sprites of the hill country rode on flashes of fire. But the

village witches and local ghosts have long since disappeared,

excepting perhaps in a few of the less penetrable districts, where

they may still survive.

It is curious to

find that down even to the beginning of the seventeenth century, the

inhabitants of the southern districts of the island regarded those

of the north as a kind of ogres. Lancashire was supposed to be

almost impenetrable—as indeed it was to a considerable extent,—and

inhabited by a half-savage race."

But despite the social and economic changes that were taking place

even as Ackworth was writing, his stories will surely continue to delight today's

readers. As the Birmingham

Daily Gazette's critic put it when reviewing the 10th edition of

"Clog Shop

Chronicles" (still in print):

"The book

is distinctly a work of genius, the author is not only saturated

with his subject, but has the power to convey his impressions

vividly and distinctly. Humour, pathos, tragedy, abound. . . .

From first to last presents feasts of good things."

|

There was a sob

and a rustle at the door, and a pale, shamefaced factory

girl stepped forward, unwrapping as she did so a bundle

containing a five-weeks-old baby, and sobbing audibly

the while. "Look at

it, Mestur," she cried, holding out her little one.

"It's as bonny as ony o' them 'at Jesus tewk in His arms," and then,

pressing closer and almost forcing the baby upon him, she pleaded―"Tak' it, Mestur, tak' it. Aw know Aw'm aat o'

th' kingdom o' God, but Aw dunnot want mi babby to be."

In a moment the student, with face all awork, had snatched

the wee thing from its pleading mother, and was offering a simple

prayer for it as he held it in his arms. Then he sprinkled it

in the "Blessed Names," and, still holding it, prayed again,—prayed

for babe and mother too,—and then, as he handed the infant back, his

eyes wet with tears, he stooped down and tenderly kissed it.

"God bless yo' fur that" cried the agitated mother; "an'

ha'iver lung yo' live, an' wheriver yo' goa, yo' con remember as

there's wun poor woman as 'ull allis be prayin' for yo', if hoo is

nowt but a nowty factory wench an' a woman as is a sinner."

The student does what ordained clergymen

would not

― he christens an

illegitimate child. . . . The

Student. |

Readers unfamiliar with Victorian Lancashire

dialect should not be deterred ― Ackworth employs the

dialect in an economical way, using it to add vivid splashes of

colour to his cameos while ensuring that the story-line is framed in

sufficient plain English to enable the reader to "decode" the short

dialogue passages without recourse to a glossary. Despite the

experience of W. E. Adams, one quickly picks it up . . . .

"Here, however, I could not qualify

the conversation, for the reason that I had not then

made the acquaintance of the Lancashire dialect, which,

as I listened to it at Chorley, was as much like a

foreign language to me as anything I had heard before.

Only a word dropped here and there, such as "bobbin" and

"mill," led me to infer that the people, for part of the

time, were talking about work at the factories."

W. E. Adams: from "Memoires of a

Social Atom"

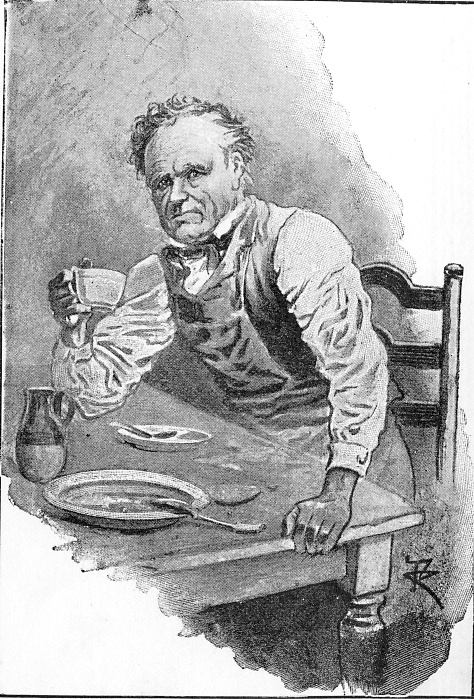

Jabez Longworth, autocratic proprietor of the clog shop, the focal point

of

life in Ackworth's mythical Lancashire mill-village of Beckside.

|

|

|

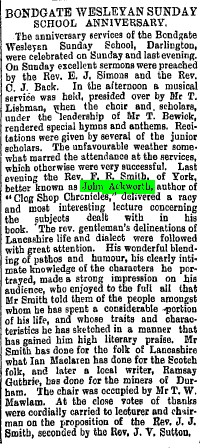

Northern Echo,

3 Oct. 1899. |

During the next 11 years Ackworth built on the "Clog Shop's"

immediate success with nine other titles, including two sequels to the "Clog Shop",

"Beckside Lights" (1897) and

"Doxie Dent" (1899), the heroine of the latter being an

enterprising mill lass of the kind that Gracie Fields was later to

immortalise on film. Ackworth gathered together other of his

Lancashire stories in the "Scowcroft Critics" (1898) and "The Mangle

House" (1902). "The Coming of the Preachers" (1901) is an

attractive 18th century tale, which chronicles the rise of

Methodism. "The Minder" (1900),

subtitled "The Story Of The Courtship, Call And Conflicts Of John

Ledger, Minder And Minister", recounts the trails and

tribulations of an impoverished young "minder" (a machine supervisor

in a cotton-mill) who eventually becomes a Methodist minister and,

after a tortuous courtship, marries the right girl. Set in the

fictional mill-town of Bramwell, the reader cannot help harking back

to Beckside or Scrowcroft and to their loveable characters; thus The Birmingham Gazette

— "Never have we seen a

finer study of principle and passion, religious fervour and human

love, than in the courtships and conflicts of John Ledger. It

is long since we read a finer novel".

|

The painter's shop was an institution in Bramwell; the new ministers

as they arrived began by suspecting and disliking it, then they came

to tolerate and fear it, and generally ended by accepting and making

the best of it. It was a sort of left wrist of the body

ecclesiastical, where the pulse of the circuit might be felt. It was

also the best place to procure or at least to hear of supplies for

vacant pulpits, and its proximity to the cattle market made it a

convenient place for the leaving of parcels of circuit plans,

magazines, and messages for country officials. Superintendents,

therefore, made use of it somewhat frequently, and all the more

willingly, perhaps, because they could always pick up there the

latest circuit gossip and the first mutterings of ecclesiastical

thunderstorms, with the comfortable knowledge that the trouble, when

it did come, would certainly not be worse than it had been

represented at the paint shop.

The ecclesiastical parliament building

of Bramwell . . . . "The

Minder" |

"Old Wenyon's Will" (1904) takes as its principal

theme the problems that stem from a bequest, by "Old Wenyon", of a

profitable public house to his disliked nephew, an ardent Methodist

teetotaller, on the condition that he and his family live there.

This otherwise charming story—a triumph for teetotalism and a

sound defeat for cupidity—includes a vivid depiction of alcoholic Billy Stiff's attack of

"cold turkey", which suggests that in his pastoral life Ackworth

had encountered alcoholism in the raw; thus a convincing portrayal of

that "rambling, raving lodger's" withdrawal symptoms . . . .

|

It took nearly an hour, and more

than one weary chase, to get the drink-ridden man to the

tollhouse, and once there the quiet little home became a

sort of pandemonium. Billy snatched at the

wonderful cakes like a ravenous beast, and then spat the

food out and yelled for drink. Twice he had to be

dragged from the door by main force, and twice he

collapsed in hopeless tears. He cursed the drink

in language that made his keepers shudder, and then

cursed them for keeping it from him. He coaxed,

and pleaded, and promised, and then laughed, and mocked,

and swore. He called Jeff all the tragedy names he

could remember, and made slobbering, demented appeals to

his wife as the "angel of the bower" . . . . and a

moment later Jeff experienced the greatest amazement of

that amazing day, for he found a man clinging to his

bare legs and sobbing, not with the whining, drunken

bathos of other occasions, but in deep, solemnest

earnestness, sobbing as only a man can sob.

The craving of alcoholic Billy Stiff. . .

. from Old Wenyon's Will |

A popular preacher, "Life's Working

Creed"― Ackworth's final title (so far as I've discovered) ― is a volume of his sermons "on the present day meaning

of the Epistle of James" (1909), which among other things serve to

provide the present day reader of Ackworth's tales with an insight

into the preaching that the Wesleyan worshippers of Beckside,

Scowcroft, Bramwell and elsewhere might well have heard . . . .

|

It is all very well for

comfortably placed ministers, arm-chair philosophers, successful

authors, and able editors to talk about the blessings of poverty—let

them come and try it. It is very beautiful to write on the 'simple

life' from a carpeted study and a soft easy-chair; let them come and

live in 71 Brick Street, and maintain a family on a pound a week,

and then see where their moralizings will be. . . .

Now, in this twentieth century, we are experiencing both the

blessedness of Socialism as an ideal, and its immense difficulty as

a practical system. The difficulty of all difficulties is how to

render help to a poor man without injuring him in character . . . .

Man on earth is the son of God in his gymnasium, and that place of

exercise has no value save what it derives from its relation to the

student. The gymnast does not spend his time in collecting and

hoarding up gymnastic appliances, his success is not measured by the

number of clubs, ladders, push-balls he accumulates, but by the

state of his muscles and the degree to which these instruments have

told upon his physical powers. Most of us have mysterious appliances

behind our bath-room doors, and Indian clubs and dumb-bells in our

bedrooms; we take golf, tennis, cricket, walking exercise, bicycling,

sea-side week-ends, and summer holidays, and yet we do not develop

our muscles half so thoroughly as that rough lad who spends his days

pulling trucks about on a pit bank. So with life—the soul's the

thing! What will benefit and develop—that is the question. . . . The soul is a young god, a glorious, undeveloped Hercules. You don't

feed giants on gingerbread and jam trifles; you don't wheel giants

about in perambulators and coddle them in cotton-wool and muslin

frills! You cannot develop the sinews of a giant by teaching him to

wave a fan. Your Hercules must have the labours of Hercules if he

would finally sit amongst the gods. . .

We believe in the

preciousness of human life, we know the disgraceful

details of infant mortality, the high death-rate in

slums, the lack of commonest necessities amongst our

fellows. We cry over descriptions of them in the

papers, we revel in luxurious pity under appeals at

public meetings; but, for all our tears and all our

sighs, if our faith carries us no further than that, it

is dead faith.

Ackworth's preaching. . . . from

Life's Working Creed. |

The "clogger" being

lectured by the irrepressible Doxie Dent ―

note Jabe's

Lancashire clogs.

|

LANCASHIRE

CLOGS:

were everyday wear for many Lancashire working-class

folk until (about) the 1920s. Unlike wooden Dutch

clogs, Lancashire clogs are a type of heavy boot or shoe

with lace-up cowhide sides and uppers and, typically,

thick wooden soles. The soles were normally carved

from alder (in wet places is extremely durable) or

unseasoned sycamore; both are easily worked and resist splitting. The finished clog

is shod with "irons", an iron edging similar to a

horse-shoe, designed to protect the sole

from wear. It took a "clogger" about two hours to

make the soles and a further two hours to make the

uppers.

Lancashire is also known for its "clog dancing", said to

be derived from cotton-mill workers emulating the sound

of their looms with their clogs. Dancing, or

"neet" clogs, don't have irons and are lighter than the

heavier working clogs. Ash is considered a good wood to

use for dancing clogs due to it being light and springy,

with plenty of bounce and a ringing tone (although the

young lady pictured was wearing rubber soles to prevent

slipping). The

cowhide uppers are sometimes highly tooled (decorated), coloured, and

might also have bells attached of the type

worn by Morris dancers—it's clogs similar to these that Jabe the clogger presents to

his adored niece, Doxie Dent. |

|

|

|

|

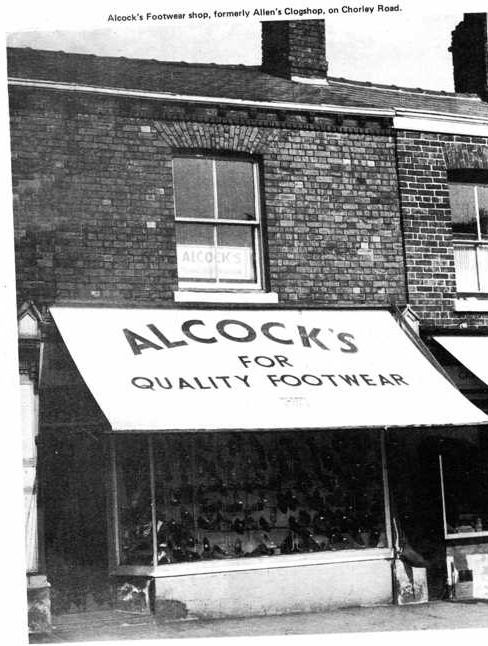

Before the close of the 19th

century, Alcock's footwear shop, Chorley Road, Swinton (above), had been a clog

shop owned by James Allen, a friend of the Rev. Fred

Smith who at that time (1891-94) was minister of St.

Paul's. Fred would call at the shop

for a chat every Monday morning ― as author "John Ackworth",

he would later cast local scenes and characters such as these as the fictional Beckside clog shop and

its acerbic (but kindly) proprietor, Jabez Longworth.

Beckside, incidentally, is thought to be modelled on Boothstown,

Salford, although Stoneclough near

Bolton is another candidate; in all probability Beckside

is a composite drawn from a number of such places.

Photo: courtesy Chris Carson. |

It's interesting to compare Ackworth with

two of the other authors listed in the website

index: the Lancashire dialect

author and poet,

Edwin Waugh, and Isabella Fyvie

Mayo ("Edward Garrett"), author of many moral stories and a

splendid autobiography.

Both Waugh and Ackworth portray ― even caricature ― the same types of

people; artisans, tradesmen,

working-class folk together with the occasional representative of

the middle classes, such as the local parson or a member of the

"squirearchy", all

of whom are presented in a rural Lancashire setting. In his short

tales of Lancashire life (e.g. "Tufts of Heater" I. &

II. and "Besom

Ben"), Waugh makes much more extensive use

of the dialect than Ackworth, and a

lexicon is a useful

companion for the uninitiated.

Slight differences in dialect crop up between the two, Waugh's being native

to the Rochdale area while Ackworth's is that of Bolton. A prominent difference in usage is in the

form of female address; Waugh employs the more common and gentle "lass"

while Ackworth's use of the much earthier "wench" takes some

coming to terms with

as a polite form of address. This is Waugh writing

about variations in the dialect . . . .

"And here it may be noticed that persons

who know little or nothing of the dialect of Lancashire are apt to

think of it as one in form and sound throughout the county, and

expect it to assume one unvaried feature whenever it is represented

in writing. This is a mistake, for there often exist

considerable shades of difference,—even in places not more than

eight or ten miles apart,—in the expression, and in the form of

words which mean the same thing; and sometimes the language of a

very limited locality though bearing the same general

characteristics as the dialect of the county in general, is rendered

still more perceptibly distinctive in feature by idioms and proverbs

peculiar to that particular spot."

Edwin Waugh: Preface to

Sketches of Lancashire Life,

1855.

But the most apparent

differences lie in attitudes to religion and choice of setting:

Waugh's tales are firmly secular whereas Ackworth's, while not overtly religious, adhere strictly to the

beliefs, the dogmatism and

the ways of life of a close-knit rural Methodist community.

|

There was probably not a shape in

hats or a cut in coats, from the early years of the

century to the very latest fashion, that was not

represented in that procession. Wide brims and

brims that were mere rims, bell-shaped and

"long-sleeved," chimneypots and bell-toppers, all were

there; and an assortment of black coats, from Nat

Scholes' sage-green cut-away to the newest and glossiest

superfine frock, that would have completely equipped the

nineteenth-century section of a sartorial museum.

Silently, sedately, with most obvious

self-consciousness, they filed out, as though a

wondering world were looking on.

Poor souls! . . . . there was nobody at all to behold

all this pride and glory. I beg pardon. In

almost every cottage door stood a perspiring and already

exhausted mother, still en deshabille, and as little

Tommy in his new velveteen suit and monster posy, or

Jane in her gay frock or gayer hat, moved proudly past,

there was a sudden glistening of motherly eyes, a sudden

uplifting of weary faces, and the work and worry of many

days seemed all too little for the sweet reward of that

proud moment.

A Sunday school procession. . .

. The Mangle House. |

For

instance, in Beckside, the scene of many of Ackworth's tales, "the

law as to the marriage with unbelievers, which according to Beckside

canons of interpretation meant all non-church members, was clear and

uncompromising" ― transgressors are shunned. Gamblers

are considered to lie well beyond the pale ― "An' whoa wur it as

ran a race fur brass yesterday amung bettors an' gamblers an'

pidgin-flyers?" asks the scandalised Sunday school

superintendent having received intelligence of such activity. And while Beckside has a public house, the chapel-going

villagers would regard it "sinful" to enter therein, let

alone partake; and the reader isn't invited across

its threshold either. Instead, Beckside's teetotal clog shop

replaces the village "pub" as the hub of information and governmental

decision-taking, Jabez

Longworth the "clogger" being its resident Speaker, while the

chapel and its Sunday school, visiting preachers and the "super"

(Methodist circuit superintendant) are called into play as occasion

demands. By comparison, Waugh often chooses the more worldly

setting of the town-square "pub" or a wayside inn in which

ale-fuelled conviviality is the order of the day. The publican

or one of his boozing cronies presides over the discussion, while an

attendant "lass" hovers to ensure that our speakers' thirsts are

adequately slaked

during an oft-lengthy session . . . .

|

"Are we to sit dry-mouth,

Bill, or how?"

"Nawe. Here, Betty, bring us a quart an' a quiftin'-pot."

"Ay; be sharp, Betty; I'm as dry as soot."

(BETTY

brings the drink.)

"Chalk it up, Betty; I haven't a hawp'ny about mi rags.

. . . Trinel; buttle, an' let's sup."

"I will, my lad. . . . An' I say, Betty, put that dur

to, an' let's ha' th' hole to ersels. Theer!

Now then, Bill, wipe thi face, and tak howd! We're

as reet as a ribbin." (Ed.—well, until the unwelcome

arrival on the scene of Bill's better half!)

Waugh, from

Bitter-Sweet. |

. . . . or . . . .

|

"Heigh, Hal o'

Nab's, an' Sam, an' Sue;

Heigh, Jonathan, art thou theer too?

We're o' alike,—there's nought to do;

So bring a quart afore-us."

Waugh, from

A

Run up the Rhine. |

|

"The next three days were the most

tormenting in Jeff's life. His wife had all a

childless woman's passion for nursing anything and

everything that came in her way, and all a nurse's

unreasonable imperiousness. Their only bed in the

cot across the road was appropriated for this

disreputable, spouting tramp; his wife occupied the long

settle, and he had to stretch his long legs where he

could. His wife was inevitable and had to be

endured, but why should he be tyrannised over by a

rambling, raving lodger, a starvation footpad, simply

because he 'hed sich grand eyes and quoted poetry'?"

A 'Shakesperian tramp' takes residence. . .

. from Old Wenyon's Will |

But this doesn't

mean that Waugh's tales are confined to inebriated antics ― his

popular "Barrel Organ" is

just one

notable departure from the tap-room ― or that those of Ackworth

are in any way stodgy or sanctimonious, a charge that can

sometimes be laid at the door of Isabella Fyvie Mayo.

Whereas Ackworth's tales have an unmistakable Methodist flavour, but

only that, Isabella's occasional lengthy bouts

of Christian preaching suggest that she could have made a successful

career for herself in the pulpit; indeed, strident

sermonizing pervades some ― but thankfully not all ― of her stories, "By

Still Waters" being an example of her religious beliefs

running amok and "Rab

Bethune's Double" of them being held in check. Ackworth takes a much more

subtle approach, contenting himself with relating

episodes in the life of his small Methodist community and conveying

his

message by way of parable rather than sermon.

|

The natural reticence of the

North-countryman leads him to avoid the use of "love"

whenever possible; and in Lancashire, "loike," the

weaker word, has come to be most commonly used about

amatory matters, and expresses the strongest possible

affection. When, therefore, Mrs. Barber employed

this term about her daughter's sentiments towards Luke

Yates, there was no room for doubt as to what she meant

by it. And if there had been, [her] manner as she

made the statement with which the last chapter closed

removed any such possibility.

From . . . . "Leah's

Love" |

Other than at Castletown and Worthing, Ackworth's ministry was served mostly in

northern circuits, including Farnworth, Lytham, Sheffield, Shotley

Bridge, York, St. Annes-on-Sea, St. Helens, Eccles (twice), Swinton,

and Manchester. His final posting was to Burnley in 1909

where, following his retirement in 1912, he became a supernumerary.

|

"You're come, Mr. Ledger, to one of

the most famous towns in Lancashire," said Betty . . . .

"Famous for what?" John asked, with an incredulous glance

round at the long chimneys, the heavy smoke, and the

dingy brick buildings.

"Famous for ugliness, sir, pure unmitigated colossal

ugliness; but never mind, it's the people that make the

place, and they are 'gradely folk.' We are jolly

here, sir; some of us jolly bad . . . . but all jolly."

A typical Ackworth setting . . . ."The

Minder". |

For some years

Ackworth had been in indifferent health, his illness eventually becoming

serious, and he died following an operation at the Victoria Hospital,

Burnley, on November 13th. 1917, leaving a widow, four sons, and three

daughters. Three sons were at the time serving in the Army, two being at

the front. John Ackworth's funeral took place at Manchester

Road Wesleyan Chapel, Burnley (now a block of flats), and he was buried in Burnley Cemetery

(grave A1716).

Annie died at the home of a daughter at Heaton Chapel, Stockport, on

27th December, 1943, aged 88.

|

. . . . He was the village

tripe-dresser, who did his business in a little wooden

lock-up shop which stood in the open space opposite the

big "Co-op. store." . . . . Talk was the breath of life to him, and as he

posed as a sort of village oracle . . . . A little,

emphatic, pugnacious individual, a bundle of

angularities and a walking compendium of crabbèd

Lancashire philosophy, he was, in spite of his trade, a

vegetarian, a teetotaler, and an anti-vaccinator; and

had a knobby, oversized head that was thatched with a

coat of coarse, dark-red hair, and which he wore at all

times and seasons, outdoor and in, uncovered. He

loved a wrangle as he loved nothing else in life, and he

and the schoolmistress were soon on terms of the most

intimate and delightful opposition. All subjects

were alike to him—and to her; neither ever gave way an

inch, and he being a philosopher, and she a woman, they

scorned the pettifogging limitations of logic and

natural sequence, and skipped about from topic to topic

with bewildering independence. He lodged with his

sister, Carrie's landlady, and soon learnt to know at

what hour she was ready to accept the gage of battle;

then, if it pleased him so to do, he would strut into

the parlour, and, spreading himself before the fire,

fling out a sentence incomprehensible to any third

person unacquainted with the last discussion, but

rousing and feather-raising to his eager lady disputant .

. . . That his own respect for her acuteness led him to

adopt her views and defend them against all comers, in

spite of his fierce opposition of them with her, was a

mere detail, and consistency was a virtue he most

heartily despised.

A typical Ackworth character . . . .

from Crooked Roots. |

As a

preacher, Ackworth was described as "striking, original, fearless,

thought-provoking, conscience-stirring, and not seldom attended with

remarkable power;" as a pastor, "he carried light and cheer wherever he

went."

|

. . . . preaching is a very serious

business. The power by whom he is commissioned,

the nature of the truths he announces, the incalculable

value of the souls to whom he is sent, and the

tremendous issues at stake, make the vocation of the

preacher positively oppressive in its responsibility.

Preaching, from . . . .

Life's Working Creed.

"To preach was his passion; it was the delight of his life. His

earnest yet genial disposition lit up the church. His preaching

consumed him as fire consumes dry timber."

A description of Ackworth the preacher. |

――――♦―――――

|