|

[Jannock]

THE BARREL ORGAN.

―――♦―――

I CAME out at

Haslingden town-end with my old acquaintance, "Rondle o'th Nab,"

better known by the name of "Sceawter," a moor-end farmer and cattle

dealer. He was telling me a story about a cat that squinted,

and grew very fat because to use his own words it "catched two

mice at one go." When he had finished the tale, he stopped

suddenly in the middle of the road, and looking round at the hills,

he said, "Nea then, I'se be like to lev yo here. I mun turn

off to 'Dick o' Rough-cap's' up Musbury Road. I want to

bargain yon heifer. He's a very fair chap, is Dick ― for a

cow-jobber. Bu yo may as weel go up wi' me, an' then go forrud

to our house. We'n some singers comin' to-neet."

"Nay," said I, "I think I'll tak up through Horncliffe, an'

by the moor-gate, to t' 'Top o' t' Hoof."'

"Well, then," replied he, " yo mun strike off at the lift

hond, about a mile fur on; an' then up th' hill side, an' through th'

delph. Fro theer yo mun get upo' the owd road as weel as yo

con; an' when yo'n getten it, keep it. So good day, an' tak

care o' yorsel'. Barfoot folk should never walk upo'

prickles." He then turned, and walked off. Before he had

gone twenty yards he shouted back, "Hey I say! Dunnot forget

th' cat."

It was a fine autumn day; clear and cool. Dead leaves

were whirling about the road-side. I toiled slowly up the hill

to the famous Horncliffe Quarries, where the sounds of picks,

chisels, and gavelocks, used by the workmen, rose strangely clear

amidst the surrounding stillness. From the quarries I got up,

by an old pack-horse road to a commanding elevation at the top of

the moors. Here I sat down on a rude block of mossy stone,

upon a bleak point of the hills, overlooking one of the most

picturesque parts of the Irwell valley. The country around me

was part of the wild tract still known by its ancient name of the

Forest of Rossendale. Lodges of water and beautiful reaches of

the winding river gleamed in the evening sun, among green holms and

patches of woodland, far down the vale; and mills, mansions,

farmsteads, churches, and busy hamlets succeeded each other as far

as the eye could see. The moorland tops and slopes were all

purpled with fading heather, save here and there, where a

well-defined tract of green showed that cultivation had worked up a

little plot of the wilderness into pasture land. About eight

miles south a gray cloud hung over the town of Bury, and, nearer, a

flying trail of white steam marked the rush of a railway train along

the valley. From a lofty perch of the hills, on the

north-west, the sounds of Haslingden church bells came sweetly upon

the ear, swayed to and fro by the unsettled wind, now soft and low,

borne away by the breeze, now full and clear, sweeping by me in a

great gush of melody, and dying out upon the moorland wilds behind.

Up from the valley came drowsy sounds that tell the wane of day, and

please the ear of evening as she draws her curtains over the world.

A woman's voice floated up from the pastures of an old farm-house,

below where I sat, calling the cattle home. The barking of

dogs sounded clear in different parts of the vale, and about

scattered hamlets, on the hill sides. I could hear the far-off

prattle of a company of girls, mingled with the lazy jottings of a

cart, the occasional crack of a whip, and the surly call of a driver

to his horses, upon the high road, half a mile below me. From

a wooded slope, on the opposite side of the valley, the crack of a

gun came, waking the echoes for a minute; and then all seemed to

sink into a deeper stillness than before, and the dreamy surge of

sound broke softer and softer upon the shores of evening, as

daylight sobered down. High above the green valley, on both

sides, the moorlands stretched away in billowy wildernesses dark,

bleak, and almost soundless, save where the wind harped his wild

anthem upon the heathery waste, and where roaring streams filled the

lonely cloughs with drowsy uproar. It was a striking scene,

and it was an impressive hour. The bold, round, flat-topped

height of Musbury Tor stood gloomily proud, on the opposite site,

girdled off from the rest of the hills by a green vale. The

lofty outlines of Aviside and Holcombe were glowing with the

gorgeous hues of a cloudless October sunset. Along those wild

ridges the soldiers of ancient Rome marched from Manchester to

Preston, when boars and wolves ranged the woods and thickets of the

Irwell valley. The stream is now lined all the way with busy

populations, and evidences of great wealth and enterprise. But

the spot from which I looked down upon it was still naturally wild.

The hand of man had left no mark there, except the grassgrown

pack-horse road. There was no sound nor sign of life

immediately around me.

The wind was cold, and daylight was dying down. It was

getting too near dark to go by the moor tops, so I made off towards

a cottage in the next clough, where an old quarryman lived, called "Jone

o'Twilter's." The pack-horse road led by the place. Once

there I knew that I could spend a pleasant hour with the old folk,

and, after that, be directed by a short cut down to the great

highway in the valley, from whence an hour's walk would bring me

near home. I found the place easily, for I had been there in

summer. It was a substantial stone-built cottage, or little

farm-house, with mullioned windows. A stone-seated porch,

whitewashed inside, shaded the entrance; and there was a little barn

and a shippon, or cow-house attached. By the by, that word "shippon,"

must have been originally "sheep-pen." The house nestled deep

in the clough, upon a shelf of green land, near the moorland stream.

On a rude ornamental stone, above the threshold of the porch, the

date of the building was quaintly carved, "1696," with the initials,

"J. S.," and then, a little lower down, and partly between these,

the letter "P.," as if intended for "John and Sarah Pilkington."

On the lower slope of the hill, immediately in front of the house,

there was a kind of kitchen garden, well stocked, and in very fair

order. Above the garden, the wild moorland rose steeply up,

marked with wandering sheep tracks. From the back of the

house, a little flower garden sloped away to the edge of a rocky

hank. The moorland stream ran wildly along its narrow channel,

a few yards below; and, viewed from the garden wall at the edge of

the bank, it was a weird bit of stream scenery. The water

rushed and roared here; there it played a thousand pranks; and

there, again, it was full of graceful eddies; gliding away at last

over the smooth lip of a worn rock, a few yards lower down. A

kind of green gloom pervaded the watery chasm, caused by the thick

shade of trees over spreading from the opposite bank. It was a

spot that a painter might have chosen for "The Kelpie's Home."

The cottage door was open, and I guessed by the silence

inside that old "Jone" had not reached home. His wife, Nanny,

was a hale and cheerful woman, with a fastidious love of cleanliness

and order, and quietness too, for she was more than seventy years of

age. I found her knitting, and slowly swaying her portly form

to and fro in a shiny old-fashioned chair by the fireside. The

carved oak clock-case in the corner was as bright as a mirror; and

the slow and solemn ticking of the ancient time-marker was the

loudest sound in the house. But the softened roar of the

stream outside filled all the place, steeping the senses in a drowsy

spell. At the end of a long table under the front window sat

Nanny's grand-daughter, a rosy, round-faced lass, about twelve years

old. She was turning over the pictures in a well-thumbed copy

of "Culpepper's Herbal." She smiled, and shut the book, but

seemed unable to speak, as if the poppied enchantment that wrapt the

spot had subdued her young spirit to a silence which she could not

break. I do not wonder that old superstitions linger in such

nooks as that. Life there is like bathing in dreams. But

I saw that they had heard me coming; and when I stopped in the

doorway, the old woman broke the charm by saying, "Nay sure!

What? han yo getten thus far? Come in, pray yo."

"Well, Nanny," said I, "where's th' owd chap?"

"Eh," replied the old woman, "it's noan time for him yet.

But I see," continued she, looking up at the clock, "it's gettin'

further on than I thought. He'll be here in abeawt

three-quarters of an hour that is, if he doesn't co', an' I hope

he'll not, to-reel. I'll put th' kettle on. Jenny, my

lass, bring him a tot o' ale."

I sat down by the side of a small round table, with a thick

plane-tree top, scoured as white as a clean shirt; and Jenny brought

me an old-fashioned blue-and-white mug, full of home-brewed.

"Toast a bit o' hard brade," said Nanny, "an' put it into

't."

I did so.

The old woman put the kettle on, and scaled the fire; and

then, settling herself in her chair again, she began to re-arrange

her knitting-needles. Seeing that I liked my sops, she said, "Reitch

some moor cake-brade. Jenny 'll toast it for yo."

I thanked her, and reached down another piece, which Jenny

held to the fire on a fork. And then we were silent for a

minute or so.

"I'll tell yo what," said Nanny, "some folk's o'th luck i'th

world."

"What's up, now, Nanny?" replied I.

"They say'n that Owd Bill at Fo' Edge, has had a dowter wed,

an a cow cauve't, an' a mare foal't o' i' one day. Dun yo co'

that nought?"

Before I could reply, the sound of approaching footsteps came

upon our ears. Then, they stopped, a few yards off; and a

clear voice trolled out a snatch of country song:

|

Owed shoon an'

stockins,

An' slippers at's made o' red leather!

Come, Betty, wi' me,

Let's shap to agree,

An' hutch of a cowd neet together.

Mash-tubs and barrels!

A mon connot al'ays be sober!

A mon connot sing

To a bonnier thing

Than a pitcher o' stingin' October! |

"Jenny, my lass," said the old woman, see who it is.

It's oather 'Skedlock' or 'Nathan o' Dangler's.'"

Jenny peeped through the window, an' said, "It's Skedlock.

He's lookin' at th' turmits i'th garden. Little Joseph's wi'

him. They're comin' in. Joseph's new clogs on."

Skedlock came shouldering slowly forward into the cottage a

tall, strong, bright-eyed man of fifty. His long, massive

features were embrowned by habitual exposure to the weather, and he

wore the mud-stained fustian dress of a quarryman. He was

followed by a healthy lad, about twelve years of age a kind of

pocket-copy of himself. They were as like one another as a new

shilling and an old crown piece. The lad's dress was of the

same kind as his father's, and he seemed to have studiously acquired

the same cart-horse gait, as if his limbs were as big and as stark

as his father's.

"Well, Skedlock," said Nanny, "thae's getten Joseph witho, I

see. Does he go to schoo yet?"

"Nay; he reckons to wortch o'th delph wi' me, neaw."

"Nay, sure. Does he get ony wage?"

"Nawe," replied Skedlock; "he's drawn his wage wi' his teeth,

so fur. But he's larnin', yo known he's Larnin'.

Where's your Jone? I want to see him abeawt some plants."

"Well," said Nanny, "sit tho down a minute. Hasto no

news? Thae'rt seldom short of a crack."

"Nay," said Skedlock, scratching his rusty pate, "aw don't

know 'at aw've aught fresh." But when he had looked into the

fire for a minute or so, his brown face lighted up with a smile, and

drawing a chair, he said, "Howd, Nanny; han yo yerd what a do they

had at the owd chapel yesterday?"

"Nawe."

"Eh, dear! . . . Well, yo known, they'n had a deal o' bother

about music up at that chapel, this year or two back. Yo'n bin

a singer yo'rsel, Nanny, i' yo'r young days never a better."

"Eh, Skedlock," said Nanny; "aw us't to think I could ha'

done a bit forty year sin an' I could, too though I say it mysel.

I remember gooin' to a oratory once, at Bury. Deborah Travis

wur theer, fro Shay. Eh! when aw yerd her sing 'Let the Bright

Seraphim,' aw gav in. Isherwood wur theer; an' her at's Mrs.

Wood neaw; an' two or three fro Yorkshire road on. It wur the

grand'st sing 'at ever I wur at i' my life. . . . Eh, I's never

forget th' practice neets 'at' we use't to have at Israel Grindrod's!

Johnny Brello wur one on 'em. He's bin deead a good while. . .

. That's wheer I let of our Sam. He sang bass at that time. .

. . Poor Johnny! He's bin deead aboon five-an-forty year, neaw."

"Well, but Nanny," said Skedlock, laying his hand on the old

woman's shoulder, "yo known what a hard job it is to keep th' bant

o'th nick wi' a rook o' musicianers. They cap'n the world for

bein' diversome an' bad to plez. Well, as I wur sayin'

they'n had a deeal o' trouble about music this year or two back, up

at th' owd chapel. Th' singers fell out wi' the players.

They mostly dun do. An' th' players did everything they could

to plague th' singers. They're so like. But yo may have

a like aim, Nanny, what mak' o' harmony they'd get out o' sich wark

as that. An' then, when Joss o' Piper's geet his wage raise't

five shillin' a year Dick o' Liddy's said he'd ha' moor too, or

else he'd sing no moor at that shop. Here noan beawn to be

snape't bi a tootlin' whipper-snapper like Joss a bit of a

bow-legged whelp, twenty year yunger nor hissel. Then there

wur a crack coom i' Billy Tootle bassoon; an' Billy stuck to't that

some o'th lot had done it for spite. An' there were sich

fratchin, an' cabals among 'em as never wur known. An' they

natter't, an' brawlt, an' played one another o' maks o' ill-contrive't

tricks. Well, yo' may guess, Nanny ――

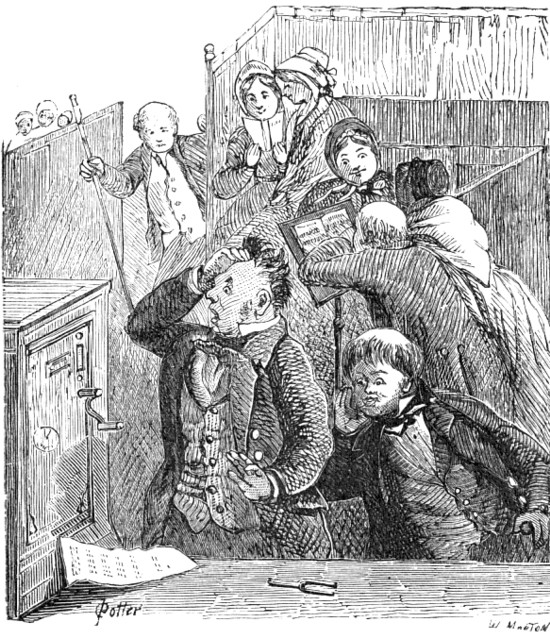

"One Sunday mornin', just afore th' sarvice began, some o'th'

singers slipt a pepper-box, an' a hawp'oth o' grey peighs, an' two

young rattons, into old Thwittler double-bass; an' as soon as he

began a-playin', th' little things squeak't an' scatter't about i'th

inside, till they thrut o' out o' tune. Th' singers couldn't

get forrud for laughin'. One on 'em whisper's to Thwittler,

an' axed him if his fiddle had getten th' bally-warche. But

Thwittler never spoke a word. His senses wur leavin' him very

fast. At last, he geet so freeten't, that he chuck't th'

fiddle down, an' darted out o'th chapel, beawt hat; an' off he ran

whoam, in a cowd sweat, wi' his yure stickin' up like a cushion-full

o' stackin'-needles. An' he bowted straight through th' heawse,

an' reet up-stairs to bed, wi' his clooas on, beawt sayin' a word to

chick or choilt. His wife watched him run through th' heawse;

but he darted forrad, an' took no notice o' nobody. 'What's up

now,' thought Betty; an' hoo ran after him. Wen hoo geet

up-stairs th' owd lad had getten croppen into bed; an' he wur ill'd

up, o'er th' yed. So Betty turned th' quilt deawn, an' hoo

said, 'Whatever's to do witho, James?' 'Howd thi noise,' said

Thwittler, pooin' th' clooas o'er his yed again, 'howdy thi noise!

I'll play no moor at yon shop!' an' th' bed fair wackert again; here

i' sich a fluster. 'Mun I make tho a saup o' gruel?' said

Betty. 'Gruel be !' said Thwittler, poppin' his yed out o'

th' blankets. 'Didto ever yer of onybody layin' th' devil wi'

meighl-porritch?' An' then he poo'd th' blanket o'er his yed

again. 'Where's thi fiddle?' said Betty. But, as soon as

Thwittler yerd the fiddle name's, he gav a wild skrike, an' crope

lower down into bed."

"Well, well," said the old woman, laughing, and laying her

knitting down, "aw never yerd sich a tale i' my life."

"Stop, Nanny," said Skedlock, "yo'st yer it out, now."

"Well, yo seen, this mak o' wark went on fro week to week,

till everybody geet weary on it; an' at last, th' chapel-wardens

summon't a meetin' to see if they couldn't raise a bit o' daycent

music, for Sundays, beawt o' this trouble. An' they talked

back an' forrud about it a good while. Turn o'th Dingle

recommended 'em to have a Jew's harp an' some triangles. But

Bobby Nooker said, 'That's no church music! Did anybody ever

yer "Th' Owd Hundred" played on a triangle?' Well, at last

they agreed that the best way would be to have some sort of a

barrel-organ one o' thoose that they winden up at the side, and

then they play'n o' theirsel, beawt ony fingerin' or blowin'.

So they order't one made, wi' some favourite tunes in 'Burton,'

an' 'Liddy,' an' 'French,' an' 'Owd York,' an' sick like.

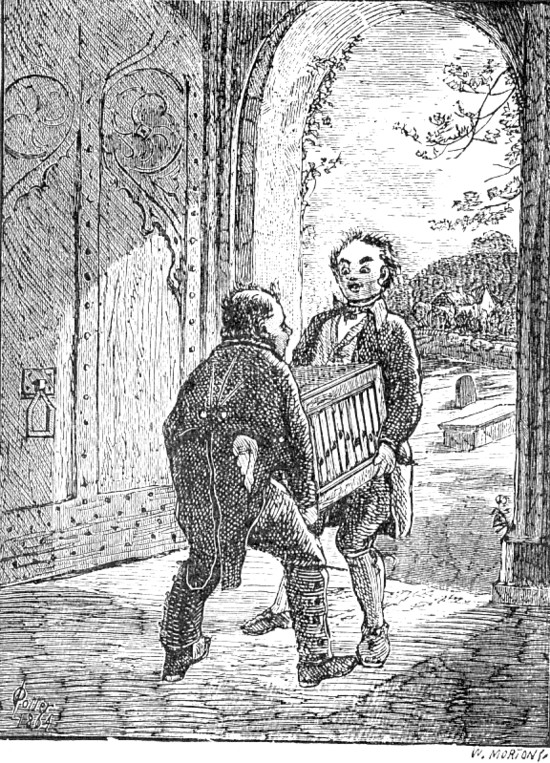

Well, it seems that Robin o' Sceawter's, th' carrier his feyther

went by th' name o' 'Cowd an' Hungry;' he're a quarryman by trade; a

long, hard, brown-looking felley, wi' een like gig-lamps, an' yure

as strung as a horse's mane. He looked as if he'd bin made

nowt o' owd dur-latches an' reawsty nails. Robin, the carrier,

is his owdest lad; an' he favvurs a chap at's bin brought up o'

yirth-bobs an' scaplins. Well, it seems that Robin brought

this box-organ up fro th' town in his cart o'th' Friday neet; an' as

luck would have it, he had to bring a new weshin'-machine at th'

same time for owd Isaac Buckley at th' Hollins Farm. When he

geet th' organ in his cart, they towd him to be careful an' keep it

th' reet side up; an' he wur to mind an' not shake it mich, for it

wur a thing that wur yezzy thrut eaves o' flunters.

Well, I think Robin mun ha' bin fuddle't or summat that neet but I

dunnot know; for he's sich a bowster-yed, moo, that aw'll be sunken

if aw think he knows th' difference between a weshin'-machine an' a

church organ, when he's at the sharpest. But let that leet as

it will. What dun yo think, but th' blunderin' foo at after

o' that had bin said to him went an' 'liver't th' weshin'-machine

at th' church, an' the organ at th' Hollins Farm."

"Well, well," said Nanny, "that wur a bonny come off, as heaw.

But how wenten they on at after?"

"Well, I'll tell yo, Nanny," said Skedlock. "Th' owd clerk

wur noan in when Robin geet to th' dur wi' his cart that neet, so

his wife coom wi' a leet in her hond, an' said, 'Whatever hasto

getten for us this time, Robert!' 'Why,' said Robin, 'it's

some mak of a organ. Where win yo ha't put, Betty?' 'Eh,

I'm fain thae's brought it,' said Betty. 'It's for th' chapel,

an' it'll be wanted for Sunday. Sitho, set it deawn i'

this front reawm here, an' mind what thae'rt doin' with it.'

So Robin, an' Barfoot Sam, an' Little Wamble, 'at looks after th'

horses at Th' Rompin' Kitlin, geet it eawt o'th cart. When

they geet how'd 'on't, Robin said, 'Neaw lads; afore yo starten;

mind what yo'r doin'; an' be as ginger as yo con. That's a

thing 'at's soon thrut eawt o' gear it's a organ.' So they

hove, an' poo'd, an' grunted, an' thrutch't, till they geet it set

down i'th' parlour; an' they pretended to be quite knocked up wi' th'

job. 'Betty,' said Robin, wipin' his face wi' his sleeve,

'it's bin dry weather latly.' So th' owd lass took th' hint,

an' fotched 'em a quart o' ale. While they stood i'th middle

o'th floor suppin' their ale, Betty took th' candle an' went a-lookin'

at this organ; an' hoo couldn't tell whatever to make on it. . . .

Did'n yo ever see a weshin'-machine, Nanny?"

"Never i' my life," said Nanny. "Nor aw dunnot want. Gi

me a greight mug, an' some breawn swoap, an' plenty o' soft wayter,

an' yo may tak your machines for me."

"Well," continued Skedlock, "it's moor liker a grindlestone

nor a organ. But, as I were tellin' yo

"Betty stare't at this thing, an' hoo walked round it, an'

scrat her yed, mony a time, afore hoo venture's to speak. At

last hoo said, 'Aw'll tell tho what, Robert; it's a quare-shaped

'un. It favvurs a yung mangle! Doesto think it'll be

reet?' 'Reet?' said Robin, swipin' his ale off; 'oh, aye; it's

reet enough. It's one of a new pattern 'at's just com'd up.

It's o' reet, Betty. You may see that birth hondle.'

'Well,' said Betty, 'if it's reet, it's reet. But it's noan

sich a nice-lookin' thing for a church, that isn't!' Th'

little lass wur i'th parlour at th' same time, an' hoo said, 'Yes.

See yo, mother. I'm sure it's right. You must turn this

here handle, an' then it'll play. I seed a man playin' one

yesterday, an' he had a monkey with him dressed like a soldier.'

'Keep thy little rootin' fingers off that organ,' said Betty.

'Theaw knows nought about music. That organ musn't be touched

till thi father comes whoam mind that, neaw. . . . But, sartinly,'

said Betty, takin' the candle up again, 'I cannot help lookin' at

this thing. It's sich a quare un. It looks like summat

belongin' maut-grindin, or summate o' that.' 'Well,' said

Robin, 'It has a bit o' that abeawt it, sartinly. . . . But yon find

it's o' reet. They're awterin' o' their organs to this

pattern, neaw. I believe they're for sellin' th' organ at

Manchester owd church, so as they can ha' one like this.'

'Thous never says?' said Betty. 'Yigh,' said Robin, 'it's true

what I'm telling yo. But aw mun be off, Betty. Aw've to

go to th' Hollins to-neet yet.' 'Why, arto takkin' thame

summit?' 'Aye; some mak o' a new fangle't machine for weshin'

shirts and things.' 'Nay, sure!' said Betty. 'Aw'll tell

tho what, Robert; they're goin' on at a great rate up at that shop.'

'Aye, aye,' said Robin. 'Mon, there's no end to some folk's

pride till they come'n to th' floor; an' then there isn't,

sometimes.' 'There isn't, Robert; there isn't. An' I'll

tell tho what; thoose lasses o' theirs they're as proud as

Lucifer. They're donned more like mountebanks' foos nor

gradely folk wi' their fither't hats, an' their fleawnces, an'

their hoops, an' things. Aw wonder how they can for shame o'

their face. A lot o' mee-mawing snickets! But they're no

better nor porritch, Robert, when they're looked up.' 'Not a

bit, Betty not a bit! But I mun be off. Good neet to

yo!' 'Good neet, Robert,' said Betty. An' away he went

wi' th' cart up to th' Hollins."

"Aw'l tell tho what, Skedlock," said Nancy; "that woman's a

terrible tung!"

"Aye, hoo has," replied Skedlock; "an' her mother wur th'

same. But, let me finish my tale, Nanny, an' then"

"Well, it wur pitch dark when Robin geet to th' Hollins

farm-yard wi' his cart. He gave a ran-tan at th' back dur, wi'

his whip-hondle; and when th' little lass coom with a candle, he

said, 'Aw've getten a weshin'-machine for yo'. As soon as th'

little lass yerd that, hoo darted off, tellin' o' th' house that the

new weshi-machine wur come'd. Well, yo known, they'n five

daughters; an' very cliver, honsome, tidy lasses they are, too, as

what owd Betty says. An' this news brought 'em o' out o' their

nooks in a fluster. Owd Isaac wur sit o'th' parlour, havin' a

glass wi' a chap that he'd bin sellin' a cowt to. Th' little

lass went bouncin' into th' reawm to him; an' hoo sed, 'Eh, father,

th' new weshin'-machine come'd!' 'Well, well,' said Isaac,

pattin' her o'th' yed; 'go thi ways an' tell thi mother. Aw'm

no wesher. Thae never sees me weshin', doesto? I bought

it for yo lasses; an' yo mun look after it yorsels. Tell some

o'th' men to get it into th' wesh-house.' So they had it

carried into th' wesh-house; an' when they geet it unpacked they

were quite astonished to see a grand shinin' thing, made o'

rose-wood, an' cover't wi' glitterin' kerly-berlys. Th' little

lass clapped her hands, an' said, 'Eh, isn't it a beauty?' But

th' owd'st daughter looked hard at it, an' hoo said, 'Well, this is

th' strangest washin'-machine that I ever saw!' 'Fetch a bucket o'

water,' said another, 'an' let's try it!' But they couldn't

get it oppen, whatever they did; till, at last, they found some

keighs, lapt in a piece o' breawn paper. 'Here they are,' said

Mary. Mary's the owd'st daughter, yo known. 'Here they

are;' an' hoo potter't an' rooted abeawt, tryin' these keighs, till

hoo fund one that fitted at th' side, an' hoo twirled it round an'

round till hoo'd wund it up; and then yo may guess how capt they wur,

when it started a-playin' a tune. 'Hello!' said Robin.

'A psaum-tune, bith mass! A psaum-tune eawt ov a weshin'-machine!

Heawe's that?' An' he star't like a throttled cat.

'Nay,' said Mary, 'I cannot tell what to make o' this!' Th'

owd woman wur theer, an' hoo said, 'Mary, Mary, my lass, thou's gone

an' spoilt it the very first thing, theaw has. Theaw's bin

tryin' th' wrong keigh, mon; thou has, for sure. Try another

keigh. Turn th' weshin' on, an' stop that din, do.'

Then Mary turned to Robin, an' hoo said, 'Whatever sort of a

machine's this, Robin?' 'Nay,' said Robin, 'I dunnot know,

beawt it's one o' thoose at's bin made for weshin' surplices.'

But Robin begun a-smellin' a rat; an', as he didn't want to ha' to

tak it back th' same neet, he pike't off out at th' dur, while they

were hearkenin' th' music; an' he drove whoam as fast as he could

goo. In a minute or two th' little lass went dancin' into the

parlour to Owd Isaac again, an' hoo cried out, 'Father, you must

come here this minute! the weshin'-machine's playin' th' Old

Hundred!' 'It's what?' cried Isaac, layin' his pipe down.

'It's playin' th' Old Hundred! It is, for sure! Oh, it's

beautiful! Come on!' An' hoo tugged at his lap to get

him into th' weshhouse. Then the owd woman coom in, and hoo

said, 'Isaacs, whatever i' the name o' fortin' hasto bin blunderin'

and doin' again? Come thi ways an' look at this machine thae's

bought us. It caps me if yon yowling divvle 'll do ony weshin'.

Thae surely doesn't want to ha' thi shirt set to music, doesto?

Thou'll ha' thi breeches agate o' singin' next. We'n noise

enough i' this hole beawt yon startin' a skrikin'. Thae 'll

ha' th' house full o' fiddlers an' doancers in a bit.' 'Well,

well,' said Isaac, aw never yerd sich a tale i' my life. Yo'n

bother't me a good while about a piano but if we'n getten a weshin'-machine

that plays church music, we're set up, wi' a rattle! But aw'll

come an' look at it.' An' away he went to the wesh-house, wi'

the little lass pooin' at him, like a kitlin' drawin' a stone-cart.

Th' owd woman followed him, grumblin' o' th' road, 'Isaac, this is

what comes on tho stoppin' so lat' i'th' town of a neet.

There's al'ays some blunderment or another. Aw lippen on tho

happenin' a sayrious mischance, some o' these neets. I towd

tho mony a time. But thae taks no moor notice o' me nor if

aw're a milestone, or a turmit, or summate. A mon o' thy years

should have a bit o' sense.' 'Well, well,' said Isaac, hobblin'

off, 'do howd thi din, lass! I'll go an' see what ails it.

There's olez summat to keep one's spirit's up, as Ab o' Slender's

said when he broke his leg.' But as soon as Isaac see'd th'

weshin'-machine, he brast eawt a-laughin', an' he sed: 'Hello! Why,

this is th' church organ! Who's brought it?' 'Robin o'

Sceawter's.' 'It's just like him. Where's th' maunderin'

foo gone to?' 'He's off whoam.' 'Well,' said Isaac, let

it stop where it is. There 'll be somebody after this i'th

mornin'.' An' they had some rare fun th' next day, afore they

geet these things swapt to their gradely places. However, th'

last thing o' Saturday neet th' weshin'-machine wur brought up fro

th' clerk's, an' the organ wur takken to the chapel."

"Well, well," said the old woman; "they geet 'em reet at the

end of o', then?"

"Aye," said Skedlock; "but aw're not quite done yet, Nanny."

"What, were'n they noan gradely sorted, then, after o?"

"Well," said Skedlock, "I'll tell yo."

"As I've yerd th' tale, this new organ wur tried for th'

first time at mornin' sarvice, th' next day. Dick-o'-Liddy's,

th' bass singer, wur pike'd eawt to look after it, as he wur an' owd

hond at music; an' the parson would ha' gan him a bit of a lesson,

th' neet before, how to manage it, like. But Dick reckon't

that nobody'd no 'casion to larn him nought belungin' sich like

things as thoose. It wur a bonny come-off if a chap that had

been a noted bass singer five-and-forty year, an' could tutor a

claronet wi' ony mon i' Rossenda Forest, couldn't manage a

box-organ, beawt bein' teyched wi' a parson. So they gav him

th' keys, and leet him have his own road. Well, o' Sunday

forenoon, as soon as th' first hymn wur gan out, Dick whisper't

round to th' folk i'th singin'-pew, 'Now for't! Mind yor hits!

Aw'm beawn to set it agate!' An' then he went, an' wun

the organ up, an' it started a-playin' 'French;' an' th' singers

followed, as weel as they could, in a slattery sort of a way.

But some on 'em didn't like it. They reckon't that they made

nought o' singin' to machinery. Well, when th' hymn' wur done,

th' parson said, 'Let us pray'; an' down they went o' their knees.

But just as folk wur gettin' their een nicely shut, an' their faces

weel hud i' their hats, th' organ banged off again wi' the same

tune. 'Hello!' said Dick, jumpin' up, 'th' divvle's off again,

bith mass!' Then he darted at the organ; an' he rooted about

wi' th' keys, tryin' to stop it. But th' owd lad wur i' sich a

fluster, that istid o' stoppin' it, he swapped th' barrel to another

tune.

"That made him warse nor ever. Owd Thwittler whisper'd

to him, 'Thire, Dick; thae's shapt that nicely! Give it

another twirl, owd brid!' Well, Dick sweat, an' futter't about

till he swapped th' barrel again. An' then he looked round th'

singin'-pew, as helpless as a kitlin'; an' he said to th' singers,

'Whatever mun aw do, folk?' an' tears coom into his een. 'Roll

it o'er,' said Thwittler. 'Come here, then,' said Dick.

So they roll't it o'er, as if they wanted to teem th' music out on

it, like ale out of a pitcher. But the organ yowlt on; and

Dick went wur an' wur. 'Come here, yo singers,' said Dick,

come here; let's sit us down on't! Here, Sarah; come, thee;

thou'rt a fat un!' An' they sit 'em down on it; but o' wur no

use. Th' organ wur reet ony end up; an' they couldn't smoor th'

sound. At last Dick gav in; an' he leant o'er th' front o' th'

singin'-pew, wi' th' sweat runnin' down his face; an' he sheawted

across to th' parson, 'Aw cannot stop it! I wish yo'd send

somebry up.'

"Just then owd Pudge, th' bang-beggar, coom runnin' into th'

pew, an' he fot Dick a souse at back o' th' yed wi' his pow; an' he

said, 'Come here, Dick; thou'rt a foo. Tak howd; an-let's

carry it eawt.' Dick whisked round an' rubbed his yed, an' he

said, 'Aw say, Pudge, keep that pow to thisel', or else I'll send my

shoon against thoose ribbed stockin's o' thine.' But he went

an' geet howd, an' him an' Pudge carried it into th' chapel-yard, to

play itsel' out i' th' open air. An' it yowls o' th' way as

they went, like a naughty lad bein' turn't out of a reawm for cryin'.

Th' parson waited till it wur gone; an' then he went on wi' th'

sarvice. When they set th' organ down i'th chapel-yard, owd

Pudge wiped his for-yed, an' he said, 'By th' mass, Dick, thae'll

get the bag for this job.' 'Why, what for?' said Dick. 'Aw've

no skill of sich like squallin'-boxes as this. If they'd taen

my advice, an' stick't to th' bass fiddle, aw could ha' stopt that

ony minute. It has made me puff carryin' that thing. I

never once thought that it'd start again after th' hymn wur done.

Eh, I wur some mad! If aw'd had a shool-full o' smo' coals i'

my hond, aw'd ha' chuck't 'em into't. . . . Yer tho', how it's

grindin' away just th' same as nought wur. Ay, thae may weel

play th' Owd Hundred, divvleskin! Thae's made a funeral o' me

this mornin'! . . . But, aw say, Pudge, th' next time at there's

aught o' this sort agate again, aw wish thee'd be as good as keep

that pow o' again thine to thysel', wilco? Thae's raise't a

knob at th' back o' my yed th' size of a duck-egg; an' it'll be

twice as big bi mornin'. How would yo like me to slap tho o'

th' chops wi' a stockin'-full o' slutch, some Sunday, when thae'rt

swaggerin' i'th' front o'th' parson?'"

"While they stood talkin' this way, one o'th singers coom

runnin' out o' th' chapel bare yed, an' he shouted out, 'Dick,

thae'rt wanted, this minute! Where's that pitch-pipe?

We'n gated wrang twice o' ready! Come in, wi thou!' 'By

th' mass,' said Dick, dartin' back; 'I'd forgetten o' about it.

I's never see through this job to mi deein' day.' An' off he

ran, an' laft owd Pudge sit upo' th' organ grinnin' at him. . . .

That's a nice do isn't it, Nanny?"

"Eh," said the old woman, "I never yerd sich a tale i' my

life. But thae's made part o' that out o' thi own yed,

Skedlock."

"Not a word," said he; "not a word. Yo han it as I had

it, Nanny; as near as I can tell."

"Well," replied she, "how did they go on at after that?"

"Well," said he, "I haven't time to stop to-neet, Nanny; I'll

tell yo some time else; I thought Jone would ha' bin here by now.

He mun ha' code at 'Th' Rompin Kitlin'; but, I'll look in as I go

by.'"

"I wish thou would, Skedlock. An' dunnot go an' keep

him, now; send him forrad whoam."

"I will, Nanny I dunnot want to stop, mysel'. Con yo

lend me a lantron?"

"Sure I can. Jenny, bring that lantron; an' leet it.

It'll be two hours before th' moon rises. It's a fine neet,

but it's dark."

When Jenny brought the lantern, I bade Nanny "Good night,"

and took advantage of Owd Skedlock's convoy down the broken paths,

to the high road in the valley. There we parted; and I had a

fine starlight walk to "Th' Top o' th' Hough " on that breezy

October night.

After a quiet supper in "Owed Bob's" little parlour, I took a

walk round about the quaint farmstead, and through the grove upon

the brow of the hill. The full moon had risen in the cloudless

sky; and the view of the valley as I saw it from "Grant's Tower"

that night, was a thing to be remembered for a man's lifetime.

――――♦――――

TOLD BY THE WINTER FIRE.

CHAPTER I.

|

Now all our neighbours' chimneys smoke,

And Christmas logs are burning;

With baked meats all their ovens choke,

And every spit is turning.

Outside the door let sorrow lie

And if for cold it chance to die,

We'll tomb it in a Christmas pie,

And evermore be merry.

GEORGE

WITHER. |

|

By the crackling fire

We'll hold our little, snug, domestic

court.

SHAKESPEARE. |

HIGH upon the

southern slope of Waddington Fell in the midst of a few green

fields, an old country inn stands, with its gable-end close to the

roadside, and the heathery moors rising wild behind it. Its

comfortable shelter was well known to all who travelled across those

storm-swept heights; and when the shades of night had folded up the

wide landscape, its cheerful light gleamed like a star upon the dark

breast of the moorland hill, far down into the vale, whilst an

inviting ray from the little window at the end of the building threw

a beam of bright welcome across the lonely road to every passer-by.

The front of the house looked down upon one of the finest expanses

in all the famous valley of the Ribble a region of clear rivers

and pure air, remarkable for the natural beauty of its scenery;

abounding in historic memorials of the olden time, and in sweet

pictures of rural life. . . .

At the foot of the fell, where the bleak but beautiful

heather-land dies away into rich meadows and pastures green, the

blue smoke curls up from the chimneys of the hamlet of Waddington,

the old town of Wada, a famous chieftain of Saxon times, whose

stronghold in those rude days occupied a remarkable conical eminence

still called "Waddow," about a mile south of the hamlet, and hard by

the banks of the Ribble. Waddington is still a quaint, quiet,

sweet-looking, rustic village, through the heart of which a limpid

stream comes wimpling down from the moors. It still retains many

features of bygone days. Its ancient church is an object of interest

to the antiquary; and close by the little stream which trails its

pleasant undersong through the quiet air of the village, by night

and day stands Waddington Old Hall, the last shelter of Henry the

Sixth, after lurking, from place to place, for years amongst these

northern wilds. It was from this ancient manor-house that he fled at

last, and was pursued and overtaken by Talbot, of Bashall, and his

men, whilst crossing the river at Brunkerley hipping-stones, about a

mile south of the village. This sealed the fate of that feeble and

unfortunate monarch; for he was conveyed thence, a prisoner, to

London, where he fell into the hands of his enemies. . . .

Looking

still from the front of the old inn, upon the fellside, into the

beautiful valley which spreads far and wide at its foot, the sweet

old town of Clitheroe stands upon a gently rising ground, about

three miles to the south, with the ruined Norman castle of the Lacys lords

of the Honor of Clitheroe upon a bold rock over-frowning the

market-place. Beyond that, the scene is bounded, on the south, by

the grand ridge of Pendle, stretching five miles, from the "big end"

of the hill, near the pretty village of Downham; on the east, to the

wooded slopes; on the west, where the hill declines into green

holms, and rich meadows, amongst which the ancient hamlet of Whalley,

and its ruined abbey, rest by the side of the river Calder.

Altogether, the landscape seen from the front of the old inn which

is the scene of our story is a glorious sight. In the Saxon period

of our history, this beautiful valley is said to have been one of

the most remarkable battle-grounds in all the north, between

conflicting Saxon chiefs, and between the Saxon and the Dane. The

landscape has certainly been wilder, and more thickly wooded, then;

but grim old Pendle the heather-crested monarch of the scene stands

there yet, in silent and solitary pride, untouched by change,

through all the lapse of centuries; and the whole country, as seen

from the wild side of Waddington Fell, must retain much of the same

general aspect that it had a thousand years ago; for,

|

Though much the centuries take, and much bestow,

Most, through them all, immutable remains,

Beauty, whose world-wide empire never wanes,

Sole permanence in being's ceaseless flow. |

It was Christmas Eve; and every lonely homestead upon the wild

moors was touched with the cheerful temper of that blessed festival

which warms the heart of man with the kindliest remembrances of all

the year. During many days past the weather had been keen and clear,

delighting every eye, and rejoicing the hearts of the young and

strong with its bracing beauty for old winter was wearing its

brightest robe, and hill and dale, and "every common sight," in all

the wide landscape was lovely to the view. The heathery slope of

Waddington Fell was white all over with a shining robe of seed

pearls; and every leafless tree, and rough thorn hedge every little

winter-nipped bush, and fern-clad wayside well, was festooned with

fairy frost-work, which twinkled in the sun. Even the rude-built

walls and fences, the lonely "rubbing stoops," in the midst of the

frozen fields, and the farm gear about the yard of the old inn, were

all decked in the glittering enchantment of cunning nature's

happiest wintry mood. The rugged rut-worn moorland roads were hard

as iron; and the crisp snow by the roadside crackled under the

traveller's foot. As twilight deepened down, and the distant

landscape began to fade from view, the blue smoke curled up thicker

than usual from the chimneys of the old house, into the pure

mountain air, for the landlord and his wife were preparing for a

jovial night for their own little family, and for any stray

travellers who might chance to cross the fell that night, from the

Trough of Bolland into Ribblesdale, after the sun had gone down. The

ordinary business of the solitary household was all arranged for the

night. The horses in the stable had been fed and foddered down; the

two cows had been milked;

|

The sheep were in the fold,

And the cattle were in shed; |

Little Liddy, the housemaid, had finished her work in the dairy, and

was in her chamber trimming herself up, after the ruder labours of

the day; "Amos o' Lumpyed's," the hostler, and general servant-man

upon the farm connected with the inn, had gone down to Clitheroe on

an errand; and old George, the landlord, known all over the Forest

of Bolland by the name of "Judd o' Sheep Jamie's" old George and

his wife, Betty, had the lower part of the house all to themselves;

for, in those days, that wild fell was not much travelled, and there

had not been a customer in the place since two hours before the sun

went down. But it was Christmas Eve; and the hearty old couple knew

it was a time not unlikely to bring strange visitors over from

Newton-in-the-Forest, on their way to Clitheroe, after nightfall.

Day was declining; but the candles were not yet lighted for old

George and his wife felt an unconscious delight in the mystic charm

of the lingering twilight hour, which filled the sweet old house

with such a dreamy beauty, at the close of a fine day. The kitchen

looked more bright and cheerful even than usual. Everything in the

place had a holiday appearance, for the landlady had decorated its

walls with evergreens, amongst which the traditional mistletoe-bush,

hanging from the low ceiling, amongst hams and flitches of bacon,

and great branches of red-berried holly, here and-there, twinkled

conspicuously in the firelight. The fire was piled up high in the

wide chimney, and its rosy glow lit up the whole room, in which

everything, great and small, was radiant with the beauty of perfect

cleanliness and order. The round-topped table was covered with a

snow-white cloth, upon which tea-things were laid for the landlord and his wife, and Liddy, the servant-girl. The great kettle hung upon

its usual hook, above the glowing grate; and a quaint tea-pot, which

rarely made its appearance, stood upon the hob. Betty had brought

her best old china out, too, for the occasion; and, in addition to

the usual simple fare of home-baked bread and sweet mountain butter,

of her own making, with a dish of fried eggs and bacon, several

dainties of the season, amongst which were spice cakes, and cheese,

and mince pies, occupied the board; and upon the great oak dresser,

under the window, a cold chine of beef stood ready for all comers. It was a pleasant sight; and the good old couple looked around with

quiet delight, as they went to and fro. Everything seemed to wink

and chuckle with glee; and the antique eight-day clock, in the

corner, ticked more blithely than usual as the ruddy firelight

played upon its polished mahogany case, across the white-scoured

floor of the kitchen.

The landlord had sat down in his arm-chair by the fire, and was

enjoying the luxury of a quiet smoke, whilst looking contentedly

around.

"Come, George," said the landlady, drawing her chair up to the

table, "come an' get thi baggin'!"

The old man laid down his pipe, and rising slowly from his seat,

till his tall figure seemed almost to touch the low ceiling of the

kitchen, he yawned, and said, "Well, I'm willin', lass; but afore I

begin, I think I'll stretch my legs a minute or two." Then, with a

slow and heavy footstep, he sauntered out at the doorway, to look at

the night.

By this time the full moon was up and it was as light as day. The

frost-pearled moorside was one glittering expanse of silvery

brilliants, under the soft radiance of the queen of night; and the

clear blue sky was thickly "fretted with golden fires." The cold

seemed to strengthen as the night came on, and the snow, which had

lain freezing for many a day, was now so hard that the foot left no

mark upon its surface.

"Betty, lass," said the old man, calling to his wife, "come here a

minute! I never seed a finer neet i' my life! This is gooin' to be

one o'th' grand owd-fashioned wintry Kesmasses with a bit o'

howsome (wholesome) nip in it sich as there use't to be when I wur a

lad! Look here, mon! It's full moon; an' it's as leet as noonday! I

could see to read th' almanac very near! An' th' stars are as thick

i'th' sky as a swarm o' gowden midges!"

The old woman came to the doorway, and looked out.

"Ay," said she, gazing round upon the bright scene, "it is a bonny

neet, for sure! But come thi ways in; thou's no hat on, an' thou'll

get coud, i' tho stops theer much lunger! Come thi ways in, an'

let's get er baggins!"

The old man came slowly back into the house, muttering that a bit o'

frost would do nobody no harm.

"Come, Liddy," said the old woman, shouting upstairs to the

servant-girl, "whatever arto doin' so long up theer? Come thi ways

down! Th' baggin's ready!"

The girl a rosy little rustic Hebe came downstairs, looking sweet

and tidy, from top to toe, and the three sat down to the table

together.

CHAPTER II.

|

Some say, that ever against that season

comes

Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirits can walk abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, no witch hath power to charm;

So hallow'd and so gracious is the time.

SHAKESPEARE. |

|

'Twas Christmas broached the mightiest

ale;

'Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

A Christmas gambol oft would cheer

The poor man's heart through half the year.

SIR

WALTER SCOTT. |

"NOW then,'' said

the landlady, beginning to fill the cups, "let's fo' to. It

looks as if we wur gooin' to ha' th' house to ersels Christmas Eve

as it is so we may as weel try to make th' best on't. Now,

Liddy, lass; reitch to an' don't be shy. Here, George;

thou'll sweeten for thisel.' I lippen't o' some of our

Jonathan's childer cumin' up, fro' Waddin'ton, an' to tell th'

truth, I feel raither disappointed."

"Thou doesn't need," said the old man. "It's Christmas

Eve, as thou says, an' folk are o getherin' round their own

hearthstones, among theirsels."

"Well; an' aren't they our own gront-childer? George,

thou talks silly."

"Never mind, lass. They known th' gate, if they

wanten to come. But, give 'em time, mon give 'em time. . . .

Now, when I wur a lad, my faither wouldn't ha' had one on us away

fro' whoam at Christmas time, upo' no 'count. We were a great

family, an' a bit scatter't, mony a mile asunder, but he said

that he like't to gether o his flock together into th' owd fowd, upo'

Longridge Fell, every Yule-time, so that he could reckon 'em up, an'

see their faces once more, bi th' feet of a roarin' winter fire.

He said it did him good; an' it did, too. As for my mother,

I don't think hoo could ha' poo'd through th' winter if hoo hadn't

sin her childer, an' her childer's childer about her, fro' o

sides, owd an' yung, an' there wur a grand swarm on us, little

an' big, when we wur o together; for two o'th' lads an' three o'

my sisters were wed, an' they brought th' yung uns wi' 'em. I

can remember us musterin' thirty i'th' owd kitchen, the very

Christmas afore my mother deed; an' a heartier family I never clapt

een on, for there weren't one on 'em that wur oather sick, or

soory, or sore an' that's sayin' a good deeol, i' sich a world as

this is."

"Well, George," replied she, "I think that we'n a reet to

expect our own childer to come an' see us i'th' same way.

They'd never missed yet; an' it looks very strange. They're o'

that we han left; an' I shan't feel reet if they don't come."

"Don't fret thisel to soon, lass. There's time enough.

What, th' eawl-leet's noan o'er yet. Make thisel comfortable.

Thou'll see this kitchen turn't th' wrang side up afore th' neet's

o'er. I shouldn't wonder if they aren't comin' gigglin' up th'

fellside this very minute, as merry as ingle-crickets."

"Well," said the old woman, wiping her eyes, "we's see. . . .

I could like to yer their feet."

"Nay, nay, lass," said he, "don't goo an' fret thisel about

nought. Thou'll have 'em among these mince-pies afore aught's

lung. I'll be bound that th' childer are as anxious to come up

as thou art for 'em to come. Dry thi een, lass, do! . . .

Here, afore I begin o' mi baggin' I'll put some moore dry eldin' upo'

that fire. We'n make a shine i'th' hole, whether onybody comes

or not."

And the stalwart old fell-ranger for in his younger days he

had been by turns a shepherd and a gamekeeper rose from the table

and fetched a great tree-root from the outhouse, which he planted

fairly upon the glowing fire. The well-dried log ignited at

once, and the flame went roaring up the wide chimney, filling the

kitchen with a ruddier light even than before.

"Theer," said he, "that looks like Kesmass, doesn't it?

We's need no candles for a bit. That'll make this house shine

down th' dark moorside like a great lantron! I'll be bund

little Nelly's clappin' her honds just this minute, an' sayin',

'Look yon! I can see my gronny's window! Hello, Liddy;

who's left this spade o'th' nook here?"

The girl rose from her seat at the table.

"It's Amos," said she. "He left it when he coom in to

his baggin', afore he set off to Clithero."

"Well, tak it into th' shippon. It's no business here.

Let's ha' th' house as tidy as we con, as it's Kesmass Eve."

The girl went out with the spade, and the old man sat down

again to his evening meal.

"I'll tell tho what, George," said the landlady, as she

filled his cup, "yon lad's raither of a careless turn. How

does thou get on wi' him?"

"Well," replied he, "Owd Bill wur worth a dozen on him!

Poor owd Bill he wur a great loss. I miss him as if he'd bin

my own brother he'd bin wi' us so lung."

"Well," said the landlady, "we han th' satisfaction o' knowin'

that we made him as comfortable as we could as long as he wur

bedridden."

"Aye," said he, "it's an ill thing to have to look back

when folk are laid by for ever an' remember that yo didn't do as

yo should to 'em while they wur alive."

"It is," said she, "it is. . . . But we ha' not that on er

minds, George as how 'tis."

"Nawe, we ha'not, lass," replied he. . . . . As for this new

lad this Amos he's nobbut a shiftless, shammockin' sort of a

craiter, as far as he's gone. He's sin nought an' he knows

nought an' he'll not do so mich, if he can help it. I doubt

th' lad's had an ill bringin'-up, an' he's some idle bwons in his

pelt. He's a lither lump o' stuff-except at eatin' an' drinkin.'

At dinner-time, he'll count four; but, when it comes to a bit o'

solid work, he isn't aboon th' hauve of a gradely chap. But

he'll happen mend we's see in a bit."

"I wonder what's keepin' him i' Clithero till now?"

"Bother thi yed noan about th' lad. He'll turn up of

hissel. I dare say he's let (alighted upon, met with) o' some

of his owd cronies. Thou knows it's holiday time, an' yung

cowts are jumpin' th' fences a bit; an' one connot expect th' lad to

keep his feet just th' same as if it wur a common wortchin'-day.

I guess he'll ha' bits o' runs of his own th' same as other yung

craiters an' he may run a bit, as far as I am concarn't."

"He should be in afore bedtime."

"What does it matter? We're noon boun to bed yet.

Never mind th' lad. If he comes, he comes; an' if he doesn't

it'll make little odds, for there's nought mich for him to do

to-morn."

"Wilto have another cup?"

"Nawe, I've done very weel. Poo up to th' hob, an'

let's make ersels comfortable. Liddy 'ill side these things."

He then rose from the table, and taking the arm-chair in the

corner, he lit his pipe; and, for the next hour or two, the time

glided by in quiet chat with his wife, who sat rocking herself on

the opposite side of the fire, the kind old man trying, all the

while, to divert the mind of his good dame from the unusual solitude

of their hearth on Christmas Eve.

Whilst they were thus conversing together, a loud sough of

wind went moaning round their solitary dwelling, and the doors of

the outhouses began to rattle.

"Hollo," said the old man, "th' wind's risin'! What's

comin' now?" and looking up at the window he saw that the sky had

become overcast. Then, rising from his chair, he went to the

door, and found that a sudden change had come over the scene.

The wind swept fiercely in at the open doorway. The moon had

disappeared, and the sky, lately so bright and clear, was now one

wild scene of commotion. Dark clouds were flying across the

heavens, and wild-driving mist and sleet filled all the air.

Not a star was now in sight. Every moment the air grew

thicker; the wind grew wilder; and the flying sleet began to be

mingled with thick flakes of snow.

"What a change!" said the old man, closing the door.

We're gooin' to have a snowstorm; an' not a little 'un, noather.

We don't need to expect onybody up fro' Clithero to-neet now, if

this howds out. . . . Liddy, goo an' put a leet i' yon end window

that looks upo' th' roadside, so that onybody may see it that

happens to come o'er th' top o'th' fell."

CHAPTER III.

|

In winter's tedious nights, sit by the

fire

With good old folks, and let them tell thee tales.

SHAKESPEARE. |

|

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roared with blithesome din;

If unmelodious was the song,

It was a hearty note, and strong.

SCOTT. |

THE storm grew

wilder, and the snow fell faster every minute. The air was

thick with flying flakes, and the whole landscape was, now, one

ghastly sheet of white. As the snow increased, the wind sank

down to a steady, sullen moan, as if overladen, and the usual

stillness of the moorland solitude deepened to a death-like hush,

which added to the appalling aspect of the scene.

A light, planted in the little window at the gable-end of the

house, now threw a cheerful ray across the lonely road which led

down the fell-side. The doors and shutters were all fastened.

The old landlady and the little household settled down, in full

expectation of passing this Christmas Eve in quiet seclusion amongst

themselves; and another hour had glided by, during which the snow

came down faster and thicker, when somebody lifted the latch, which

was followed by a loud knock at the door, and voices heard in

conversation outside.

"There's somebody here at last," said the old man, going to

the door just as the knock was repeated louder than before.

"Who's theer?" cried he, before drawing the bolt of the door.

"There's three on us," replied a merry voice in the storm

outside; "there's me, an' Jack o'th' Tinker's, an' Alick o'

Cauve-lickt Antony's. We'n com'd o'er th' top, by Wallapa

Well, out o' Newton-i'-Bollan'. Oppen th' dur. We connot

get no fur (further)."

The landlord threw the door open at once, and in rushed the

three travellers, muffled to the chin, and all white with snow.

"Lads," said he, glancing at the wintry storm before he

closed the door again, "yo'n brought a wild neet wi' yo'!"

"Nay," replied the spokesman of the three, looking round the

kitchen, as he shook the snow from his clothing, we'n left it

beheend us, an' between yo' an' me, maister, I'm fain to get under

cover, for we're just about done up. Con we stop o' neet?"

"Yo' may, if yo'n a mind an' welcome!" said the old

landlord.

"That's th' mak! (make, sort.)"

"Here," said the landlady, setting three chairs around the

hearth, "draw up, an' warm yo'; for yo' mun have had a terrible

trawnce o'er th' fell i' this storm."

"Thank yo', mistress," replied the rattle-pate who had first

spoken, "I like th' look o' this side o' th' house, I con tell yo'!

An' it's a good job we geet in, too, for Alick here's noan weel."

"What's th' matter?"

"He's a terrible pain in his inside."

"Eh dear! Does he tak' nought for it?"

"Yigh, three or four times a day, an' sometimes moor."

"Some mak' o' bottle, I guess?"

"Nay; it's mostly pills."

"What mak' o' pills?"

"They're for th' stomach."

"Oh! that's wheer it tak's him, is it?"

"Aye, aye," said the landlord, laughing; "I'm a bit trouble't

wi' th' same complaint mysel'. But yo'n com'd to th' reet shop

for bein' cure't this time. We're seldom short o' hunger

physic i' this house, thank God! . . . Liddy, set th' cowd beef upo'

th' table, an' let these lads thwite (to cut with a thwittle) at it

a bit."

The table was quickly spread with substantial Christmas fare,

and the hungry travellers sat down. For about half-an-hour

every man of the three "played a good stick," as the old saying

goes, chatting blithely together all the while; and when they had

eaten their fill they rose and took their seats around the hearth

again, in merry mood. They had hardly got well settled before

a whining and scratching was heard at the door.

"Hello, Alick," said Billy o' Mall's o' Jumper's, the

"ready-mouth" of the party, "thou's laft thi dog out! Oppen th'

dur!"

Little Liddy opened the door, and in rushed the dog, whisking

the snow from his hide all over the floor.

"I'll tell tho what, Alick," said Billy, "that dog o' thine's

a quare-lookin' craiter. What breed dosto co' it?"

"Nay, thou fastens me now," replied Alick. "It's a

mixtur o' maks (kinds). Sometimes I think it's a tarrier, an'

sometimes I think it'll turn out a foomart-dog; but th' yure's to

short. It's a bit o' bull about th' nose; but it looks as if

it had bin clemmed at t'other end, for th' hinder-quarter's nipt in

like a greyhount whelp. I doubt it's had moore faithers than

one. But I like th' dog, for o that it's sich a feaw un. It's

good to nought mich but for a bit o' company. It followed me

whoam fro' th' fair about a month sin', an' I didn't like to send it

away in th' wide world, to be starve't, an' punce't, an knocked

about fro' window to wole."

"Well, you're a good pair, Alick," said Billy, "an', as far

as I'm concarn't, I'se be sorry if ever you're parted. . . But

it reminds me," continued he, "of a dog that I bought one

Whit-Monday. When I took it whoam my wife stare't at this

thing a bit; an' at last hoo said, 'Now, then, what hasto getten

this time?' 'Well,' I said, 'it pretends to be a dog.'

'A dog, eh?' said hoo. 'I shouldn't ha' thought it; for it's

feaw enough for a corn-boggart. What, thou'll turn this house

into a gradely menagerie soon, what wi' th' hens, an' th' pigeons,

an' th' poll-parrot, an' two canaries. Thou'rt nought short

but a camel, an' two or three monkeys, an' thou't be set up for

life. But I'm noan boun to ha' that thing i' this house, I can

tell thou.' An' I said hoo should, an' hoo said hoo wouldn't;

an' we fell out abeawt it. But while we wur at it ding-dong,

th' cat coom in an' settle't o disputes wi' a rattle. Th' cat

had just kettle't that mornin', an' as soon as it seed th' dog it

flew at it, an' for a minute or two I couldn't tell which wur which,

they wur so mixt up together. An' they whuzzed round like a

fizz-gig.

First I geet a wap o'th' dog, then I seed a bit o'th' cat;

but I couldn't sort em at o; an' between yeawlin', an' scrattin',

an' spittin', an' squeakin', they kickt up such a din that it made

mi yure stone o' one end. At last th' cat jumped onto th'

table, wheer th' dinner wur set out, an' th' dog jumped after it.

Then they set th' pots agate o' flyin'; an amung th' rest, a dishful

o' bacon collops went to th' floor. Our Sall flew at 'em wi' a

quart pot in her hond; but, as hoo wur gooin', hoo happen't to set

her foot onto a bacon collop, an' away hoo went across the floor in

a great slur (slide), wi' her legs a yard asunder, an' hoo never

stops till hoo coom bang again th' edge o'th' clock wi' her nose,

an' down hoo went, back'ards, upo' th' floor, wi her nose bleedin'.

'Oh, I'm kilt,' cried Sall, 'I'm kilt!' an' I went to help her; but,

just as I wur bendin' down, hoo up wi' her foot and took me bang

between th' een, wi' sich a welt that sparks flew i' o' directions;

an' down I went staggerin', th' hinder-end first, into a mugful o'

dough, that stood at th' end o' th' dresser and there I stuck

fast. By this time hoo'd getten to her feet; and while I wur

busy, tryin' to wriggle mysel' out o' th' mug, hoo flung an' owd

birdcage at mi yed, that wur stonnin o'th' nook an' that wur

followed wi' a mugful o' starch that coom flusk into my face, an'

filled my mouth an' een, till I wur as blint as a bat.

I don't know what hoo sent th' next, but I kept feeling one

cloat after another, as thick as leet, an' when I coom to reckon

mysel' up, I found that I'd a pair o' prime black een, an' a cut o'

mi foryed, an' four or five fresh lumps o' my yed for hoo had me

fast, an' hoo kept hommerin' at it like a nail-maker i' full wark.

After I'd getten the starch out o' mi een, I wur a good bit afore I

could rive mysel' out o' th' mug an' then I fund that I'd as mich

bakin'-stuff stickin' to th' thick end o' mi breeches as would ha'

made a couple o' four-pond loaves. While this wur agate, th'

cat had run up to th' top o'th' eight-day clock, an' th' dog had

gone yeawlin' out at th' dur, wi' a quart pot after it. I know

not where th' dog's londed, but it took off toward Yor'shire, an'

I've never sin it fro' that day to this; an' I don't think I ever

shall as lung as our Sall's alive. . . . Well, when I'd poo'd

mysel' out o'th mug, I fund our Sall rear't up again th' dresser,

strokin' her nose, an' tryin' to get her breath; an' I believe, to

th' best o' my remembrance, that I said some words that I never

yeard in a chapel but I'll not mention 'em again. An' hoo

left me nought short, for hoo towd me moore about my private

character than ever I knew afore. It made my yure stone up, I

con tell yo. But let that drop; for I don't like to think on't;

an' I don't want it to goo ony fur. . . .

Well, as I stoode o'th' middle o'th' floor, tryin' to poo

this stuff off mi breeches, we looked at one another for a minute or

two. At last, I said to her, 'Now, then, owd lass; what does

to think o' thisel'? Thou'rt a bonny baigle (beagle, dog), for

onybody to look at!' 'Ay; an' so art thou,' said Sall.

'Thou'd make a rare alehouse sign, if thi pictur' wur takken as thou

stops!' 'Well,' I said, 'I should look a bit different, owd

lass, for thou's takken some pains wi' this face o' mine this last

twothre minutes.' 'Sarve tho reet, thou 'greight idle

rack-an'-hook!' said Sall. 'Where's that pratty dog o' thine?

Thou'd better look after it! It's a pity to lose sich a thing

as yon. It should ha' stopt, an' had a bit o' some'at to eat.

I doubt th' poor thing's noan satisfied wi' his maister. Go

thi ways, an' look for it, or else somebody'l bi steighlin it.

Poor thing! Folk shouldn't be rough wi' things that connot

speak for theirsels.' 'Never thee mind, owd lass,' I said;

'I'll ha' that dog back here if I'm a livin' mon whether thou

likes it or not.' 'I would, lad,' said Sall; 'an' bring a wild

craiter or two, at th' same time; an' let's set up a show!'

'Nay,' I said, 'there needs no moore wild craiters where thou art.

An', as for a show, that nose o' thine would fotch brass just this

minute, if I had tho in a caravan. But, I'll be gooin',

an' th' next time I come thou'll be fain to see me, whether I've a

dog or not.' 'Take thisel' out o' mi seet, an' keep thi

heels this road on!' cried Sall. An' as I went out at th' dur-hole,

a rollin'-pin flew close by my ear-hole, an' broke a weshin'-mug

that stoode at tother side o'th' road. . . . I coom off, an' left

her to it a bit.'

Billy's dog story put all the company into a merry temper and

the night wore on in cheery chat and story. As it drew near

midnight, the storm gradually abated, and the heavens grew bright

again.

"Now then," said the old landlord, looking up at the clock,

"it'll be Christmas Day i' two minutes! Fill up, lads!"

The old clock in the corner struck twelve; and everybody

listened to the last stroke.

"Stop!" said the old man. "Husht! . . . Ay, yon's

Clithero Church bells!"

The merry peal, mellowed by distance, came floating up the

fellside, with the glad tidings of the happiest feast of all the

year.

"A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!" cried old George,

rising to his feet; and as the toast went blithely round the

kitchen, a burst of music arose under the window. It was the

Christmas waits, who had wandered up from Clitheroe to salute old

George and his wife.

Sweetly into the wintry air arose Dr. Byrom's fine carol,

"Christians, awake, salute the happy morn!" sung to the well-known,

glad old tune, which was composed for it by Wainwright, the organist

of Manchester Old Church.

The landlord threw the door wide open, and cried, "A Merry

Christmas to yo o'! Come in, an' let's look at yo! I'm

fain to see yo, by th' mass! Come in. But who han we

here?" said he, laying his hand upon the shoulder of a little

figure, muffled in a red cloak. The child threw its cloak off,

and held up its laughing mouth to be kissed.

"Eh, it's our Nelly!" cried the old landlady. "Eh, my

darlin', my darlin'!"

"Yes," said the child, "an' my father's here; an' our George,

an' our Mary; an' Kate an' Annie are comin' up, beside! "

"Eh, my darlin's my darlin's!" cried the kind old matron,

bursting into tears of joy, as she clasped her children to her

breast, again and again, one after another.

And it was a blithe Christmas morning in that old house upon

Waddington Fell Side.

――――♦――――

OWD CRONIES.

THE face of

nature has been so much changed in Lancashire during the last eighty

years that it is hard to conceive what the country was like three or

four centuries ago. Almost within the memory of living man,

the rise of modern industrialism, and the combination upon the same

spot of the elements essential to success in manufacturing

enterprise coal, stone, clay, iron, and water the great energy of

the old inhabitants; the vast influx of population from other

quarters, and the rapid growth of wealth and towns these things

altogether have overwhelmed the ancient features of the land like a

sudden deluge; and now the county which, up to a century ago, had

seen least of change, has, since that time, undergone greater

alteration in its appearance and way of life than any other part of

the kingdom.

In ancient days, when men never dreamt of the slumbering

wealth beneath the surface, its soil was reckoned among the poorest

in England, and its people among the hardiest; its range of hills

rolled across the country in stormy waves of lonely moorland; its

cloughs were impassable swamps; its forests were wild

hunting-grounds, kept for the pleasure of the king and the nobles of

the land its roads were chiefly ancient bridle-paths; and upon its

plains there were vast tracts of wild heath and spongy moss.

Sterile, remote, and unattractive, it held little communion with the

rest of the kingdom, except when stirred by some great event which

roused the whole land to war. Then, indeed, the strong-bred

bowmen and billmen of Lancashire mustered from their leafy nooks and

followed the banners of their proud aristocracy to many a

well-fought field, where their stern front and deadly shafts have

spread dismay amongst the boldest foes.

In those wild times Lancashire was famous over all England

for its terrible bowmen. In many of its ancient towns as at

Rochdale and Bury there are places which, though now covered by

modern streets, still bear the name of "The Butts," where the

ancient population practised archery, then the warlike sport of the

yeomanry of England. Some parts of Lancashire cherish the old

love of archery to this day: and on the south-eastern border of the

county the legends of Robin Hood are still associated with the land.

Upon the wild western slope of Blackstone Edge an immense crag

stands alone the rugged monarch of the moorland in the lowmost

part of which there is a small cave, known all over the country side

by the name of " Robin Hood's Bed," and upon the opposite hills

there are great boulders, which he is said to have flung across the

valley.

Ancient Lancashire was a comparatively roadless wild; and its

sparse population scattered about in quaint hamlets and isolated

farm-nooks were a rough, bold, and independent race, clinging

tenaciously to the language, manners, and traditions of their

fore-elders; and despising all the rest of the world, of which they

knew next to nothing. Its simple life was singularly

self-contained, and what little traffic it had was carried on by

strings of pack-horses, upon rugged tracks, which had been the

pathways of the ancient inhabitants of the land from the earliest

historic times. These facts leak out in all that we read of

Lancashire in the olden time. The learnθd Camden, after

travelling over the rest of the kingdom, implored the protection of

Heaven before entering on a region so little known and of such wild

repute as Lancashire was in those days; and Arthur Young the famous

Suffolk agriculturist, writing about the end of the last century,

complains in vigorous, old-fashioned English about the state of the

Lancashire roads at that time. He lived long enough, however,

to see the beginning of a new state of things in that county.

CHAPTER I.

MIDDLETON IN THE OLDEN TIME.

|

O' crom-full o' ancientry.

OUR FOLK. |

IN the time of

the Plantagenets, when the woods of Lancashire were wild and thick,

when its air was pure, and its rivers clear, and all the country

wore the livery of nature, Middleton must have been one of the most

picturesque villages in the county. In those days, when the

neighbouring hamlet of Blackley was deep in the heart of a forest

when "Boggart Ho' Clough" was a "deer leap," and "Th' White Moss"

was a lonely waste of evil repute, little Middleton, with its fine

old manorial hall, its moated rectory, its timber-built houses, and

its venerable church upon the hill, must have been a pretty nest of

rural life in the midst of a green and quiet country. Even

now, when the land has been stript of its ancient woods, and all

nature seems to have been pressed into the service of modern

necessities, the country around is prettily varied in feature, and

the little town is pleasant to the eye. The history of the

place is obscure until the beginning of the thirteenth century when

Henry the Third was king, in whose reign a church existed, upon the

site of the present one. In the same reign the manor was held,

"by military service," by a family bearing the local name the

Middletons of Middleton; one of whom, Sir James Middleton, is

associated with the foundation of a chantry chapel in the ancient

church of Rochdale, five miles off. From the Middletons this

manor passed, in the reign of Henry the Fourth, into the hands of

the Bartons, then a famous family in Lancashire. From the

Bartons the lordship of Middleton passed into the possession of the

Asshetons men of great renown in their day. Baines says:

Margaret, the daughter of John

Barton, Esq., having married Ralph Assheton, Esq., a son of Sir John

Assheton, knight, of Ashton-under-Lyne, he became lord of Middleton

in her right, in the seventeenth of Henry the Sixth, 1438, and was

the same year appointed a page of honour to that king. He was

knight-marshal of England, lieutenant of the Tower of London, and

sheriff of Yorkshire, 1473-1474. He attended the Duke of

Gloucester at the battle of Haldon, or Hutton Field, Scotland, in

order to recover Berwick, and was created a knight banneret

on the field for his gallant services, 1483. On the succession

of Richard the Third to the Crown, he created Ralph vice-constable

of England, by letters patent in 1483.

And thus it was that the little town of Middleton emerged from its

old historic obscurity, and became associated thenceforth with the

great events of the times, through connection with the Asshetons, in

the person of Sir Ralph Assheton the terrible "Black Lad" of

Lancashire story one of the most ambitious and active members of a

powerful family, of whose tyranny tradition still preserves the

remembrance. Dr. Hibbert, in his history of Ashton-under-Lyne,

says of this famous favourite of a cruel king:

He committed violent excesses in

this part of the kingdom. In retaining also for life the

privilege of guld riding, he, on a certain day in the spring,

made his appearance in this manner, clad in black armour (whence his

name of "Black Lad"), mounted on a charger, and attended by a

numerous train of his followers, in order to levy the penalty

arising from neglect of clearing the land from carr gulds [Ed.

― 'corn marigolds']. The name o' the "Black Lad" is at

present regarded with no other sentiment than that of horror.

Tradition has, indeed, still perpetuated the prayer that was

fervently ejaculated for a deliverance from his tyranny:

|

Sweet Jesu, for Thy mercy sake,

And for Thy bitter passion,

Save us from the axe of the Tower,

And from Sir Ralph of Assheton. |

The present church seems to have been built upon the site of

the previous edifice, by Sir Richard Assheton, a grandson of the

"Black Lad." On the south side of the church is the following

inscription, which indicates both the rebuilders and the date of the

present edifice: "Ricardus Assheton et Anne, uxor ejus, Anno D'ni

MDXXXIIII." This Sir Richard was, for his valour and bravery

at the battle of Flodden Field, knighted by Henry the Eighth, and

had divers privileges granted within his manor of Middleton.

An ancient window of stained glass commemorates the death of sixteen

of the band of Middleton archers, who fought under Sir Richard in

that famous fray. The church contains numerous monuments of

the Asshetons; and part of the armour of the same "Sir Richard,"