|

ISABELLA

FYVIE MAYO

is little remembered today, but during the later decades of the 19th

century this determined, independent-minded and hard-working woman

became a widely published poetess and author, much of her prose output being published

― both in the U.K. and in North America ― under the

nom de plume,

"EDWARD GARRETT".

She also became a speaker on liberal

causes, particularly on the themes of religion, pacifism and animal

welfare.

The following

biographic sketch draws mainly on Isabella's splendid autobiography, "Recollections

of Fifty Years" (see the sections in italics that

follow), which provides a vivid account of the

difficulties and hardships faced by Victorian middle-class women who

attempted to earn their own living . . . .

|

". . . . women who earn money by doing

whatever work they are best able to do, are not much

honoured yet. It is thought that they lose their

womanliness. Girls who choose to live on relations

who are neither very able nor very willing to maintain

them, are commonly thought more lady-like. Many

men would not care to marry a woman who had worked for

her bread. People don't say these things quite

plainly . . . . they only act them. They would

tell us that they respected us, but they would not ask

us to a dinner party. They might say they wished

their daughters were like us, but they would not be

pleased if their sons wanted to marry us."

Perception of the Victorian working woman, from "Doing

and Dreaming" |

――――♦――――

Isabella Fyvie was born in London on 10th December, 1843, to Scottish

parents, Margaret Thomson and George Fyvie. She was the

youngest of the couple's

eight children, five of whom died in

childhood including

their four sons. Isabella was educated privately, mainly at a girls' school near Covent

Garden.

In 1851 her father died. George Fyvie had owned a

successful bakery, but following his death the business went into

decline: "for this startling reverse there were several causes. The

environment had changed; residents had gone off to suburbs. My

mother had little business acumen or enterprise, and could not adapt

herself to new conditions." The executor of her

father's estate "proved a broken reed. He took no interest, gave no advice.

He knew how to prosper financially himself, but he never helped

anybody else to prosperity." The outcome was that the

family fell heavily into debt and while still a girl

―

who had enjoyed

a comfortable, Victorian, middle-class upbringing

― Isabella was obliged to seek a living as best she could. "My life-and-death fight for bread and independence"

was to last from 1860

to 1869, but the family debts were repaid eventually and in

the process Isabella acquired "a mass of knowledge, both of facts

and different ways of looking at them, and of human nature generally"

― life's greatest lessons are

taught outside the classroom.

|

"Did anybody ever resolve to do anything without instantly finding

an opening by which to carry out his resolution? Possibly the opening

was always there, only waiting the opened vision and outstretched

hand to

recognize and seize it."

'Actions speaking louder then words',

from "Doing

and Dreaming" |

Her first business venture during these hardship

years was to sell embroidered strips, made by her sister and herself, to a stall-holder in a London street

bazaar, who "bought them for 9d. each (2s. 3d. in all) and the strips had cost at

least 3d., and the embroidery cotton about 1½d.

. . . It was a cruel task." But on her seventeenth birthday

(1861) Isabella was invited to meet

Mrs. S. C. Hall (Anne Maria Fielding), then editor of the St. James's Magazine,

whose attention had been drawn to Isabella's promising verse.

It "proved a memorable date

. . . . little could I dream it then, but on that birthday I was

born into a friendship that never fainted or failed (though it was

often tried)." Mrs Hall advised her to give up writing for

several years, and

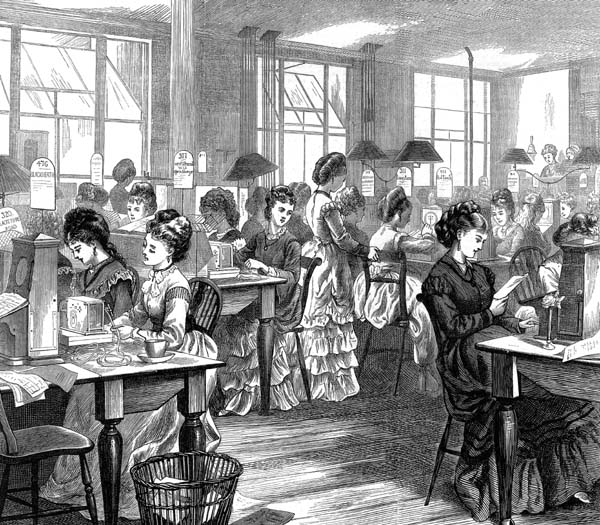

found her work in a telegraph office. But

"the noise of the machines

was incessant, and, without being loud, was most irritating to the

nerves" . . . .

|

"O, how Mary loathed the daily

surrounding of her life. Years afterwards it would

return to her as a nightmare—the big bare chamber at the

top of the huge house in Telegraph Court, the sun

flaring down through the dusty skylights, the long rows

of soiled wooden desks dotted with machines whose horrid

metallic clack went on relentlessly. There were at

least a hundred girls in that room; some stolidly

absorbed in their functions, some only too ready to turn

aside to furtive novel or snatch of chatter."

Life in a telegraph office, from "Rab

Bethune's Double" |

. . . . After two weeks, and feeling that she could

no longer continue, she again sought Mrs Hall's help. "'You must leave at once,' she

said. 'We must find you something else.' 'When one door shuts,

another opens' was a favourite proverb of hers." Armed

with an introduction to Bessie Rayner Parkes ― a redoubtable

campaigner for women's education and legal rights ― Isabella

was found casual secretarial work through the

'Office for the Employment of Women', an enterprise created by the

'Langham Place Group.'

Isabella's first assignment was to address

envelopes at the sum of three shillings per

1500. Her employer was a 'gentleman' running for public office

who permitted her, unwittingly, to learn "a little of the ways of

wire-pulling and of corruption". Later, during a a

period in which she provided holiday cover at the Office for the Employment of Women

[NOTE 1.],

Isabella

received at first hand an insight into the plight of

'distressed gentlewomen,' often

much older and less capable than herself . . . .

|

". . . . The work at the society's offices was rather depressing. It meant

confronting, advising, and making notes concerning an ever-flowing

stream of feminine misfortune, misery, and incapacity. Most of the

women who came to the office belonged to the middle classes, and

nearly all were middle-aged. There was a deadly gentility about

them, and though they represented themselves as in dire distress, or

as dependent on relations not able or willing to maintain them, they

were frequently very well dressed—quite grand, indeed, as compared

with my own shabby little self. They were "ready to do anything." They could do nothing. They seemed to hope for work on the plea that

they were "so well connected."

Those who really moved my sympathy were old governesses, who could

no longer get pupils, and who, though they had earned considerable

salaries, had saved nothing, often because they had supported agèd

parents, or had educated young brothers, now sometimes dead, but

more often married and ungrateful. I remember one of these ladies,

with a face still bright and winning, who took a sovereign from her

purse, and holding it up, said, "This is my last." I remember, too,

an attractive young woman, with an earnest, anxious face, who gave

her name with the prefix of "Mrs.," and was eager for work, because

her husband was incapacitated by illness. What became of those poor

people? Of course, when my little term of office ended, I heard no

more about them. It was rather a heart-breaking experience, the more

so because I felt, even then, that most of these poor people needed

to be helped out of themselves before anybody could give them any

other help worth having. . . ."

ISABELLA

FYVIE MAYO,

from . . .

"Recollections of Fifty Years" |

Other assignments followed including work as a copyist, and as

an amanuensis to a "literary woman." She

― identified only as Miss Y

― was

"decidedly a 'character'" who, being a Scot, "invariably decried

all things English . . . . an aggravating woman,

and I can understand that she could make herself most objectionable

to many people." Aggravating or not, Miss Y

― who it later transpired had a serious drink problem ― was a welcome

source of income at six pence per hour. Another

interesting employer was the dilapidated Countess of B;

"We drove from her house in an ordinary cab, and I

wondered why our cab attracted so much attention, till I realized

that her liveried servant was on the box." But the

countess, a Roman catholic, failed to attract the approval of the

vigilant Mrs. Hall, who "regarded it as a

Popish plot to entrap a promising young woman." Years

later, such experiences were to provide Isabella with dashes of colour for

her story-lines . . .

|

"As for her other employers, they

numbered people with hobbies and crazes,—one, a dear old

lady, sweet and gracious as spring lilac, who had strong

convictions that the Isle of Man had been peopled by the

lost Ten Tribes; another, of high rank, who accepted

Mary's help in arranging valuable papers, to which her

own position gave her access, and in whose mansion Mary

went happily up and down—now taking tea with the

marchioness in her boudoir, and then with the

housekeeper and the ladies' maids in their little room

downstairs."

From "Rab

Bethune's Double" |

Isabella's next venture was as a legal

copyist, work that required a combination of technique, precision and

swiftness.

Of such sweatshop labour she had this to say

―"Once work came in—as it often did—in the evening, and the

time marked for its return compelled me to work through that night,

all the next day, the following night, and the day after till about

seven in the evening. During that time I paused only to snatch

some food . . . . and for about two hours' sleep." And, when

an assignment was complete,

"we could not be released for

home at once, lest more work should come in. I was so tired and

sleepy that I laid my chair down on the [office's]

rag rug, used one of its

rungs as a pillow, and there I straightway enjoyed an incredibly

sweet snatch of slumber."

|

"Even the dry law papers which she copied had lessons for

Charlotte—hints of the subtlety and magnitude of hereditary

influences, of strange secret compensating laws of nature, to say

nothing of occasional terrible

revelations of social depths and complications beneath the smooth

surface of society, each working itself into some great problem that

the race must solve some day."

Isabella recycling life-experiences, from

"Doing

and Dreaming". |

Isabella excelled as a law-writer, eventually becoming

self-employed. But, when she in turn offered employment to 'gentlewomen'

in sore need of income, the memory of her time as secretary in the

Office for the Employment of Women was to revisit her

― this, of one "lady" that she sent to work as a copyist ― "when

she found that she would have to sit in the gentleman's library,

himself at work at another table, she refused to stay. She

said it was not proper, and she was so well-connected!"

Some 30 years later Isabella was to recall such experience: in her

novel "Rab Bethune's Double," young Mary Olrig, having gained a

position as trainee telegraph operator (unpaid during training!) meets

an unsuccessful

applicant as she leaves the telegraph office

. . . .

|

"Well, I'm glad I've seen the place,"

remarked the elder woman, with an acid smile. "Now

my mind can be at rest about it. For I see it is

not the place for a lady by birth, so very well

connected as I am in the Church and the Army—of course,

it is a very good opportunity for plain, strong, young

girls, fit for roughing it; my dear, I suppose you are

to be congratulated."

The unhealthy influence of social

connections, from "Rab

Bethune's Double" |

. . . . Such were the social constraints faced by Victorian

middle-class women, even in the face of penury. This type of

experience was to teach Isabella an important commercial truth in

her law-writing business, that her "first

duty was not the philanthropic teaching and training of incompetent

women, but rather of getting and keeping as much work as I could

. . . . I fell into the habit of seeking assistance only from

the men law-writers."

From an early age, Isabella had shown interest in writing

both verse and stories . . . .

|

15A,

HOLLAND STREET,

KENSINGTON.

DEAR MISS FYVIE,

"I have just received your note and the little tale called 'Janet

Campbell.' You asked to have it noticed on the cover of the

magazine, but as I could only mention it there, I prefer to write to

you privately.

"At your early age, my dear, it is better that you should be

cultivating your own mind than that you should attempt to interest

and amuse others. You are not able at present to write from your own

observation, but must

draw your characters and scenes from books. This is not good for

you, and if you ever wish to write really well, you must wait till

you have made your own observations on human nature. I think your

tale very much

better than most girls of your age would have written, but I do not

consider it worthy of a place in the magazine (which I only began

this month to edit), but I feel interested in your account of

yourself. If you like to write

to me, and tell me what is your condition in life, whether you are

at school, and what you are doing to improve yourself, I should be

happy to answer your letter, and if I can give you any advice, shall

be glad to do so.

"I would not advise you to write any more till you are sixteen, and

in the meantime I would take particular notice how books and papers

which interest you are written. Say to yourself when you read of

children: 'Do the

children that I know talk in this way, or act in this way?' If they

do, then consider the book well written. If they do not, then notice

in what the difference consists. You should do the same in reference

to grown-up

people, though the most useful studies for you are girls of your own

age, because you can understand their motives best.

"You are at present not mistress of your own language. In your nice

little note to me you say: 'It is MORE the wish of learning your

opinion concerning it rather than the hope of its being inserted,'

etc. You must not use

more than one of these words; the other is superfluous. Again, in

the tale you say: 'I do not dare do what is wrong,' 'You must be

made reveal your secret.' 'I do not dare to do what is wrong,' 'You

must be made to

reveal your secret,' would be more correct; or, better still, 'I

dare not do what is wrong.'

"And now I have not time to write more. I give you my address and

name, and if you like you can write to me.

"I am,

Yours sincerely,

JEAN INGELOW.

3 January, 1857

―――♦―――

From . . . .

Recollections of

Fifty Years |

. . . . Throughout these sweatshop years Isabella maintained her

assault on that

near impregnable bastion into the literary world,

the Editor's desk, which provided yet another memory she

was later to recall . . . .

|

"Mary had had a sad day. The

morning post had brought back a poem which she had sent

weeks before to a certain magazine. And it looked

so crisp and fresh that she doubted if the editor had

done more than transfer it, unread, from the envelope in

which she sent it to that which she had enclosed . . . .

when she came home in the evening, tired out, with damp

garments, she found another post packet waiting for her.

This was a story returned from another quarter.

The manuscript was rather voluminous, but in this

instance it had been so fingered and dog-eared, that it

could never be sent on another adventure, with such

ill-omened marks of foregone failure palpable upon it."

Yet another rejection slip, from "Rab

Bethune's Double" |

. . . . Gradually, her early essays in verse

began to attract attention ― "My earnings in the first year of these efforts were

£30. In the second they were £60; in the third and fourth, about

£80; in the fifth, my tiny literary earnings having somewhat

increased, nearly £100" [See POEMS,

which contains examples of Miss Fyvie's early verse, as published in

Good Words and other Victorian periodicals]. Then, in 1867, came the

breakthrough

― "having earned yet another £100, that "miracle" happened to me—of a

publisher's asking an unknown girl to write a serial for an

important magazine, paying her £300 for it, and inviting her to write

another on the same terms." The publisher was

Alexander Strachan. It later

transpired that she had been invited to contribute to the

Sunday Magazine to fill a gap left by a defaulting

contributor, Strahan acting on the advice of Alexander Japp,

another of Isabella's future friends. "Mr. Strahan himself was, it seems, very

nervous about the matter, which is not surprising."

|

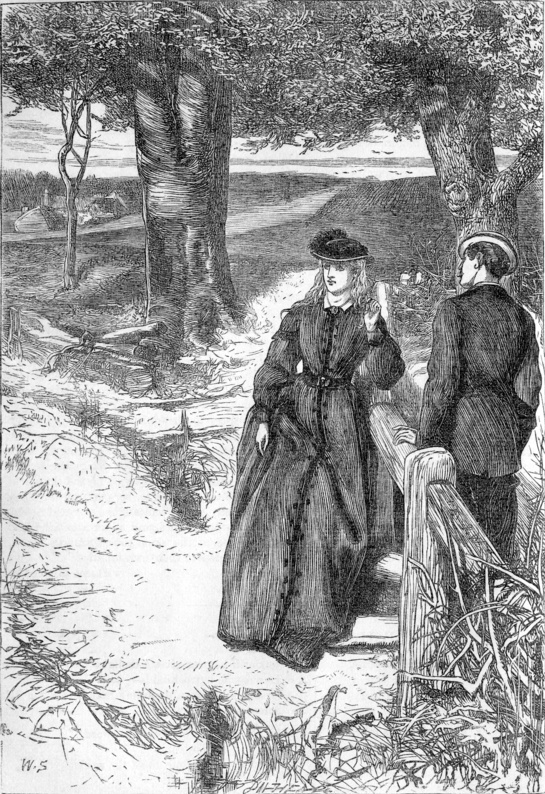

BESIDE THE STILE. |

|

WE both walked

slowly o'er the yellow grass,

Beneath the sunset sky:

And then he climbed the stile I did not pass,

And there we said Good-bye.

He paused one moment, I leaned on the stile,

And faced the hazy lane:

But neither of us spoke until we both

Just said Good-bye again.

And I went homeward to our quaint old farm,

And he went on his way:

And he has never crossed that field again,

From that time to this day.

I wonder if he ever gives a thought

To what he left behind:—

As I start sometimes, dreaming that I hear

A footstep in the wind.

If he had said but one regretful word,

Or I had shed a tear,

He would not go alone about the world,

Nor I sit lonely here.

Alas! our hearts were full of angry pride,

And love was choked in strife:

And so the stile, beyond the yellow grass,

Stands straight across our life.

ISABELLA FYVIE

From Good Words, 1867.

――――♦―――― |

Strachan had already

decided on the plot and advertised the story, which was to come from the

pen of "Edward Garrett" (a nom de plume) ― "He

had jotted down, in his quaint handwriting, on a tiny scrap of paper

(which I still possess), a few of the subjects with which he wished

me to deal—the sick, the lonely, the outcast, and so forth. I

was to take the standpoint of an old City merchant. 'Apart

from that, I leave you to do your best with the matter,' said he."

Isabella decided on a serialised novel, the outcome being "The

Occupations of a Retired Life," the first of her many successful

compositions in the genre. "On Christmas Eve, while I was

out, Mr. Strahan called at our house, and left for me a cheque as

"one-third payment" for 'The Occupations of a Retired Life,' which

raised his payment for it to £300 [the initial offer had been

for £100]. Within a day or two afterwards he told me that

his firm would be prepared to take as much work of any kind as I was

likely to do. From that time till Mr. Strahan left the firm (I

think in 1873) I worked only for his magazines."

|

Aberdeen Weekly Journal

18th September, 1893.

Mrs Isabella Fyvie Mayo, who writes fiction both

in her own name and under the nom de plume of

"Edward Garrett," is the widow of a London

solicitor. Her father came of a race of

Aberdeenshire farmers of the old-fashioned kind,

who worked with their own hands and in whose

kitchen the birr of the spinning-wheel was

seldom silent. Her mother was the

descendant of a similar family among the

"Borderers" on Tweedside. |

In later years, Isabella Fyvie Mayo

and "Edward Garrett" between them became a prolific and successful

poetess and author, being published widely

in both the U.K. and the U.S.A. Her stories usually appeared in serialized

form in

one of the popular periodicals of the day including The Sunday Magazine, Good Words, The Quiver,

The Argosy, The Girl's Own Paper,

and

Onwards and Upwards, often being

followed by hard-back editions. Their sentimental plots are sometimes heavily

embroidered with Christian morality ―

"a

catholicity of religious sentiment" as one

reviewer described it ― that no doubt answered the pious requirements of the

journals for which they were intended, but which rather limit their appeal today.

Time and again her sermonizing gives the impression that, had

it been possible at the time for a woman to take holy orders,

Isabella

would have been well equipped to have done so.

|

"For there is a life which will bear us

company and keep us safe on either—that Life which is

the Light from above and the Way from below, the

revelation of the love and character of God, his Father

and ours; the life of Him who was born in a manger and

tempted in the wilderness, who wept and was indignant,

who loved and was lonely, who was applauded and

outlawed, who gave himself up to God's Will in

Gethsemane, that He might be given away on Calvary!

'God forgive me, if I am daring,' thought Sarah Russell

; 'but I almost think that those who tread the longer

way home may gain some secrets of sweet and sacred

companionship which they would not give up for the

swifter journey. The two disciples did not know

Jesus till the walk to Emmaus was over; but when He was

revealed did they wish the way had been shorter?

And yet for those who miss the gems that lurk in the

dark waters of deep experience, and who miss the

glimpses gained from Pisgah heights of mental triumph,

there remain the unreckoned mysteries of that especial beatitude: "Blessed are they

who have not seen, and yet have believed." But after all, that

blessing remains for every one of us, and for one as much as

another, for, in the vastness of the truth and love of God, the

little differences in our developments of faith and grasps of law

dwindle as do the differing mountains of the earth as it hangs in

boundless ether! He who knows most and believes most is he who,

climbing height after height in the spiritual life, is clear-eyed

enough to see height after height rising above him, and pausing to

look up on the unknown hills beyond, as well as to survey the

conquered land that lies behind, is honest-hearted enough to own

that he knows nothing, except that it is his duty to go forward in

the name of God!'"

From . . . "By

Still Waters (a story for quiet hours)" |

Other than devoting time to writing, Isabella travelled widely (Chapter

VIII., "Recollections"), became a prison visitor (Chapter

X., "Recollections"), a lecturer/campaigner, and the first woman member of the Schools Board for Aberdeen.

Reports in the Aberdeen press during the 1890s portray an ardent socialist

who, at the time of the Second Boer War,

was a vociferous supporter of the ant-war movement, her publically

expressed views attracting much hostility! She was also a

translator of Tolstoy [NOTE 2.].

But in somewhat surprising contrast to what one might expect of a progressive Christian,

is her uncompromising attitude to 'fallen women' wishing

to enter domestic service: "But there are some very sinister aspects of the domestic employment

of women who have lost character. Why should a fellow-servant,

possibly some decent working-man's innocent young daughter, be

exposed to household association with some Magdalen who quite

possibly "loved not much" anything or anybody but her own

sensuality and idleness?" ―

so much for the compassion of the age.

|

|

|

MR.

AND MRS.

JOHN RYALL

MAYO.

"Of medium height, with large,

sparkling eyes and a broad, intellectual forehead,

but a face of great sweetness and

gentleness." |

In July, 1870, Isabella married John Ryall Mayo, a solicitor,

and in the autumn of that year they visited Canada. John Mayo died in 1877, leaving her with a son, George (born 1871). Although her short

married life appears to have been happy,

her "Recollections" tell us little about it or her

husband (to whom the book is dedicated), and nothing about her son.

She might have had more to say about both it and about other aspects

of her work ― including her interest in Tolstoyan philosophy

― in a later volume of memoires that she planned, but did not live

to write.

|

"The first duty of the British workers is

to refrain from entering the Army or Navy, these being

the tools whereby their landowning class defend their

own possessions at home, and exploit and seize on the

land of others abroad. The British working man has

been too often misled into rejoicing in the evil of war

on the pleas that it "increases employment" and "gives

new fields for labour," while he has remained blind to

the fact that within the last twenty years millions of

acres in his own country have passed out of cultivation

and become mere playgrounds for the exploiters of

industry."

From Isabella's 'Note' to a "A

Great Iniquity"

by LEO TOLSTOY |

Isabella died at her

home, "Bishop's Gate", in Old Aberdeen on 13th

May, 1914.

|

|

Bishop's Gate, Old Aberdeen. |

|