|

".......those who

knew him can recall the frail looking man, with the pale expansive

forehead, the deep-set lustrous, melancholy eyes, together with the

impression he gave you of one who had endured much, and had been patient

in his endurance, but who, with all his shyness and timidity of address,

was not without latent strength, and a marked individuality of character.

The truth was that in spite of his melancholy aspect, this knight of the

sorrowful countenance was a very mirthful man, into whose verse, humour

was introduced as by a natural process. None of his poetical compeers

stuck more closely to the [Lancashire]

dialect....he was wise in limiting himself to the folk-speech; had he

tried to write like Shakespeare, our poet would have failed."

JOHN MORTIMER.

Manchester Literary Club.

――――♦―――― |

|

|

|

When'er thi mood for humour lay,

Tha used it in a rousin' way;

But said what tha had got to say

Without assumption;

Thi rhymes are forcible an' gay,

An' full o' gumption. |

WILLIAM CRYER

from...To the Memory of Samuel

Laycock

――――♦――――

Samuel Laycock, Lancashire Poet.

(1826-1893)

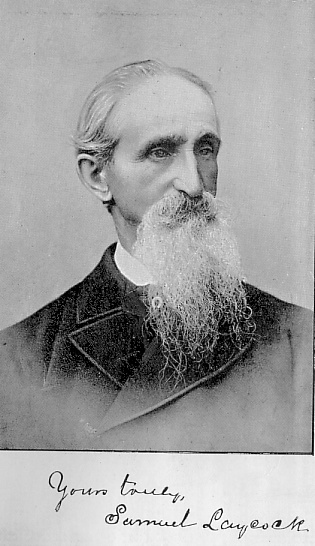

Physically, he was small and spare, with a

large and striking head. The face was refined, shrewd, and

kindly, with a latent expression of pensive sadness. Ben

Brierley in a skit, spoke of him as "all head." He carefully

cultivated a beard. His manners were gentle and unassuming,

his demeanour quiet and subdued, the true interpreter of Lancashire

working folk, at the hearthstone and in the intimacy of family life,

plucking the very heart-strings. Laycock's philosophy was

simple and was gathered from everyday experiences. There was

no subtlety or complexity in his verses; no enigma of existence

troubled him; no hot passion swept through him. When he was

thrilled to poetic emotion, however, he wrote well. Laycock sowed,

reaped, and harvested, and gained the esteem of innumerable

Lancashire people.

――――♦―――― |

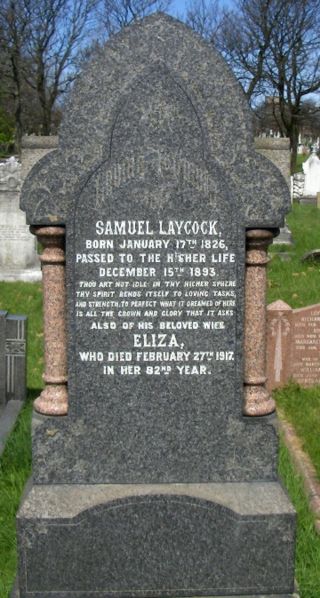

b. 17th January, 1826 at Intake Head, Marsden near

Huddersfield, the son of John Laycock, a weaver.

d. 15th December, 1893 at Blackpool and interred Blackpool Cemetery. |

|

SAMUEL LAYCOCK.

BORN JANUARY 17TH, 1826.

DIED DECEMBER 15TH, 1893.

|

BARD of the loom, the workshop, and the mill,

Whose lowly songs for lowly folks were sung,

Thy death a thousand hearts with grief doth fill;

For thou didst speak to men in their own tongue,

And teach them how to see with clearer light

And hopeful vision through their ills and strife;

So that with patience they might view aright

The comedy and tragedy of life.

Adieu, sweet singer, gone to sing elsewhere,

Thy voice has ceased within our earthly choir,

To join the swelling chorus sung up there;

And we shall miss the music of thy lyre;

But in our memories we shall cherish long

The sweet remembrance of thy life and song.

David Lawton |

――――♦――――

|

One does not

expect to find a Yorkshireman among the foremost writers of poetry in

the Lancashire dialect, but

SAMUEL LAYCOCK was

such.

Laycock's grandfather

was a farmer, and during his childhood young Sam spent many happy years on

the farm and roaming the countryside surrounding Marsden, a small town

lying between Saddleworth and Huddersfield (see

Mi Gronfeyther and

Marsden). His was a strict

upbringing. At the age of six he began his formal education—so far

as his part-time work would permit—at a day school run by the Rev.

Jonathan Bond (described by Laycock as "an old Scotchman"), the same

cleric who on the 12th February 1826 had baptised Sam at the Buckley Hill

Independent Chapel in Marsden. This may also have been where Laycock

records his meagre education being supplemented by attending Sunday

School.

At the age of nine, Laycock commenced

working full time (6 a.m. to 8 p.m.) at Robert Bowers' Woollen Mill,

Marsden, for which he received a weekly wage two shillings. When Laycock was 11 years of age, the family moved to Stalybridge,

then at the centre of the cotton industry, an industry that suffered

periodic times of depression—"when't trade wur slack." When working,

he earned his living as a power loom weaver eventually becoming foreman, an

occupation he continued until 1862 when the blockade on Confederate cotton

exports imposed by the North during the America Civil War caused mass

unemployment and much hardship among the Lancashire cotton workers, a

period that became known as the "Cotton Famine" (or "Cotton Panic").

|

|

|

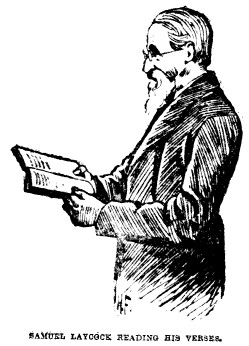

Manchester Times

23 December, 1892. |

Laycock began to write poetry in the 1850s but it

was during the period of the Cotton famine, when he began to compose his famine songs

and poems inspired by both the circumstances and the influence of the

Lancashire poet Edwin Waugh (see stanza three,

Presentation), that his poetry attracted

serious attention. Laycock was

eventually to become known throughout

Lancashire and beyond for his dialect poems and, together with Edwin Waugh and Ben

Brierley, is now acknowledged to be one of the grand masters of the genre.

In 1825, the Stalybridge Mechanics' Institute was founded in

Shepley Street, with a reading room in Queen Street, the aim being to

educate the growing number of cotton workers. When Laycock later gave up work in the cotton industry,

he was for

six years the Institute's Librarian and Hall Keeper, and also acted as Curator to the Addison Literary Club. Ably

assisted by his wife and family he began a bookselling business in Oldham

Market Place, but despite much hard work the business failed. Around

1867, for reasons of health, he moved to the Lancashire coast where, for a

short time, he was Curator of the Whitworth Institute at Fleetwood (later

the

Fielden Library, predecessor to

the present Fleetwood Library). In 1868, he moved down the coast to

the seaside resort of Blackpool where he began work as a photographer (see

Ben Brieley, Adventures at Blackpool). His health

improved, but by 1887 failing eyesight caused him to relinquish the

photographic business.

|

"....Samuel Laycock is the popular and vernacular poet of

Lancashire, who since the time of the cotton famine has been

recognized as the lyrical spokesman of his own people. His

poems in dialect are vigorous and racey. He is less at home in

literary English, and here his native genius sometimes deserts him

and he shrinks into the commonplace. But his vernacular lyrics

are spontaneous and original productions, instinct with the working

life of Lancashire, and full of good humour and good sense."

THE

TIMES

Friday, October 13, 1893. |

Laycock was an honorary and (from all reports) a

highly respected member of the Manchester Literary Club. He was also

a member of the Burnley

Literary and Philosophical Society and was elected a member of the

Blackpool Free Library Committee just six weeks before he died.

Besides numerous poems published as broadsheets, his published books are:

"Lancashire Rhymes and Homely Tales" (printed by John Heywood

of Manchester and sold at 2s 6d each; Poems and Songs

(1864—see reviews); Poems and Songs:

enlarged edition (1875); Warblin's fro'

an Owd Songster (1893 and 1894); and The Collected Writings of Samuel

Laycock, which appeared posthumously in 1900. However, the bulk

of Laycock's writing by which he most wished to be remembered appears in Warblin's.

Samuel Laycock died of influenza and pneumonia, aged 67, at

his home at 48, Foxhall Road, Blackpool, on the 15th December, 1893, and

was buried in Layton Cemetery, Blackpool. A local and county committee under the chairmanship of James

F. Farrar was formed to decide on a suitable memorial, which was placed in

Marsden Park. It was

later resolved that a portrait in oils painted by Mr. S. Lawson Booth, J.P., of

Southport should be presented to the Corporation Art Gallery in Queen

Street, and at an imposing ceremony it was unveiled at the Town Hall by

Mr. Hall Caine September 7th, 1920. The portrait is now believed to

be held by the

Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, but is not on display.

Laycock was thrice married:

. . . . to Martha Broadbent, a cotton weaver,

at the Independent (Congregational) Church in Tintwistle, on 9th December

1850. Martha died of Tuberculosis on August 1852;

. . . . to Hannah Woolley of Stalybridge, at

the Independent (Congregational) Chapel at Ryecroft, Ashton, on 30th

October 1858. Hannah died on 24th December 1863, two weeks after the

birth of "Bonny Brid";

. . . . to Eliza Pontefract of Holmfirth, at

the Unitarian Chapel, Stamford Road, Mossley, in June 1864.

――――♦―――― |

|

|

|

|

Broadsheets by courtesy of Blackpool Central Library.

――――♦―――― |

|

A LITTLE POSIE TO THE

MEMORY OF SAMUEL LAYCOCK

by

WILLIAM CRYER

(1845-1917) |

|

THE minor bard has work to do,

A heaven-sent mission to pursue,

And needful is he as the few

Great sons of song;

To chant his cheery message to

The toiling throng!

Sing, peasant Clares, through English lanes,

Your simple songs to country swains;

And wake, sweet Tannahills, your strains

"Ayont the Tweed."

Who shall declare what are your gains

For human need?

Still rise the lark to glory higher,

The thrush pour out its heart's desire,

And our rapt, longing souls inspire

With love's warm pledge!

Yet bless the robin's breast of fire

In some thorn hedge!

* *

* *

* *

My dear, owd songster, I am just

Talkin' to thee,—an' aw needs must,—

As if tha'd ne'er had "dust to dust,"

Said fondly o'er thee;

An' aw shall tell the truth, aw trust,

An' not a story.

This little posie, I have brought,

I' thy remembrance, is nought,

Judged bi itsel, but warmest thought,

Tha may be sure,

Did prompt it, as might come, unsought,

Ten thousan' moor!

Though homely was the harp tha strung,

Tha put some spirit i' thy song ;

It made owd folks agen feel yung,

To yer thee sing!

As winter's gloom aside tha flung,

At shout o' spring!

What did thi life ston for, mi friend?

But o' thoose blessed things that tend

Mad strife and bitterness to end,

Or make 'em less,

An' gie this world a sweeter blend

Of happiness!

There is a humanness about

Thi verses, leavin' one no doubt,

The meanest thing tha would not scout,

If it wur good;

An' for humanity tha fowt,

As best tha could.

The things tha liked were surely sent

To make us moor wi' life content;

When sad at heart, or labour-spent

Wi need, at times,

Some liltin' song, some floral scent,

Or merry chimes!

When times are bad, an' faces glum,

It tak's some courage then to hum

A "welcome," should a stranger come,

But that tha did;

An' soon tha made it feel awhoam,

That "bonny brid"!

Tha coom i' t' nick o' time to sing

Thi songs o' courage, an, to bring

Some cups o' comfort fro' the spring

O' livin' hope

And bid sad hearts to faith to cling,

An' not to mope!

Tha liked to play, when work wur done,

Tha liked a bit o' gradely fun,

To crack a joke, an' make a pun,

Some friend to chaff;

Tha liked, as weel as glint o' sun,

A hearty laugh!

Tha kept thi faith i' God an' men,

An' trusted friendship's gowden chen,

Or else tha ne'er had sung agen,

But deed repinin'!

Tha seed, as wi' a prophet's ken,

Some hope-star shinin'!

The common things o' life tha took

An' glorified, bi word an' look;

An open mind tha ne'er forsook,

One weel may tell;

An' by reflections i' thi book

One sees thisel.

The things tha honoured are a sign

Ut tha wur blest wi' feelin's fine;

And O' may sich a friend bi mine,

Yo heavenly powers!

Who loves, as wi' a touch divine,

Childther an' flowers!

Thi soul wur manly, it wur mild,

An' thine were no pretensions wild;

Religion pure an, undefiled,

To thee wur sweet;

Wi' Jesus, an' a little child,

Tha felt o' reet!

Domestic joys tha loved to own,

Tha liked to see a clen hearthstone,

Where sat owd Darby and his Joan,

So cant an' cosy;

Tha liked to walk a country lone,

Tha loved a posie!

When skies wur dark, an' fortune black,

Wi' dogged steps tha kept thi track;

To ease the burden on thi back,

Tha made a jest on't;

Feelin' a sore, tha had a knack

To make the best on't.

The shiftless mon, wi vision dense,

Ne'er won a word o' thy defence;

This thing tha kept in evidence,

Nor feared to show it,

A mon may ha' both grit an' sense

An' be a poet!

Tha met rebuffs a time or two,

But bore them without mich ado;

Of milk o' humankindness few

Had richer dower;

And ne'er a trouble tha passed through

Could turn it sour: |

Tha had thi failin's, aw doubt not,

Knew best thisel thi wakest spot;

But, judgin' o' the human lot,

Wi' thee as sample,

A blessed confidence we've got,

And hope that's ample.

When'er thi mood for humour lay,

Tha used it in a rousin' way;

But said what tha had got to say

Without assumption;

Thi rhymes are forcible an' gay,

An' full o' gumption.

Owd bard, an' seer, our aims are one!

For when thi flash o' humour shone,

Tha felt life's solemn purpose, mon,

One plainly sees;

An' knew that life was meant for none

For selfish ease.

Wi' pathos, worthy highest creed,

Tha did for human progress plead;

Banned war, that doth the nations bleed,

An' robs the bosom

O' that which is its pride, indeed,

Young manhood's blossom!

In words impassioned, deemed uncouth,

Save to a northern ear, forsooth!

Tha towd this patriot's land the truth,

An' sought to robe her

Wi' things o' beauty and o' ruth,

An' make her sober!

Tha did not blame the rich becose

O' what they had, but for the woes

Some viewed unfeelingly, an' chose

Their hearts to harden;

An' counted these the wust o' foes

For God to pardon!

The field tha showed, where men o' war

Could try their strength on ills that jar

Wi' social order, an' that mar

The bliss o' life!

An' "grapple wi' their evil star,"

I' Godly strife!

An' though the feight bi stern an' tough.

In spite o' cynic sneer and scoff,

The world will yet bi better off,

An' see wi' loathin'

Its foul, immoral garb, an' doff

Its dirty clothin'!

Reet fain our famous shire should be

To honour sich a mon as thee;

One o' that minstral company

Fro' labour sprung;

An' cheered wi' light o' poesy,

Hath toiled an' sung!

Whose songs have lured us fro' the street

To seek betimes the moorland sweet;

An' climb wi' joy, fair scene to greet,

Yon upland wild;

Or cull the flowers, in some retreat,

Like happy child!

Bade us our native hills look on,

When Pendle's brow wi' glory shone,

While Blackstone Edge, an' Rivington,

Claimed us in turn!

An' as we talked an' journeyed on

Our hearts would burn!

Thi rhymin' ware tha did not puff,

For tha had wit an' sense enough,

To know that diamonds i' the rough

Some day would get

Inspection, an' like honest stuff,

Bi valued yet.

Tha found out, lad, an' very quick,

Wi'th' Muse one should not get so thick,

For hoo con hardly keep one wick,

Shuzhow he Sings!

An' gies one but a scanty lick

O' life's good things!

Tha did not come fro' folks o' rank,

Who had a good account at bank;

But ony fayther, to be frank,

What'er he be,

Would proudly the Almighty thank

For son like thee!

To trouble's storm tha set thi teeth,

An' passed life's wintry sky beneath,

Stood on its lone an' barren heath,

Wild waste o' round!

What time tha laid affection's wreath

On hallowed mound.

Tha took up very little space

I' this big world, but filled thi place

Wi' moral dignity an' grace,

As friend an' brother;

Dared this life's road, nor feared to face

T' way to another.

Humour an' pathos—blessed twain!

Blended their music i' thi strain,

An' for our ills tha did retain

A feelin' tender;

An' so, this honour wi are fain

This day to render.

Tha hardly could ha' thought that here,

I' bussy, drivin' Lancashire,

Wi' should ha' stopped to give a cheer

For Laycock's lays!

An' grant his work and life's career,

Due meed of praise.

Fro' little things, I've yerd it said,

Great things have groon, so I've bin led

Some little wayside seed to spread

While talkin' to thi;

May some sound heart an' thoughtful yead

Receive it duly.

As lung as Blackpool's breezes blow,

As lung as childther,—bless 'em O!—

Shall crowd its beach, an' pleasure show,

Thi name shall linger;

And honest admiration grow

For sich a singer! |

|

from "LAYS AFTER LABOUR"

(BLACKSHAW, BOLTON,

1902)

――――♦―――― |

|

|

|

|

JOHN BULL AN' HIS TRICKS!

(Glossary of Lancashire dialect) |

ON THE DEATH OF THE LATE RICHARD

OASTLER.

THE SUCCESSFUL CHAMPION OF THE TEN HOURS BILL. |

|

OH, forshame on thee, John! forshame on thee, John!

The murderin' owd thief 'at theaw art:

Tha'rt a burnin' disgrace to humanity, mon,

Tho' theaw thinks thisel' clever an' smart.

Tha'rt a beggar for sendin' eawt Bibles an' beer,

An' calling it "Civilization;"

While thee an' thi dear christian countrymen here,

Are chettin' an' lyin' like station.

Thee tak' my advoice, John, an' get a good brush,

An' sweep well abeawt thi own door;

An' put th' bit o' th' lond at tha's stown to some use,

Ere theaw offers to steal ony moor.

An' let th' heathens a-be; for tha's no need to fear

'At they're loikely to get into hell:

My opinion is this—if there's onyone near

A place o' that mack— it's thisel'.

It's thee 'at aw meon, John, theaw hypocrite, theaw;

Wi' thi Sundayfied, sanctified looks!

Doesta think 'at ole th' milk comes fro' th' paps o' thy ceaw!

Is ole th' wisdom beawnd up i' thy books!

An' what abeawt th' mixture o' cotton an' clay,

'At theaw thrusts on thi unwillin' nayburs?

Eh John, tha'rt a "Cure," but tha'll catch it some day,

When tha's ended these damnable labours.

Tha may wee! tell the Lord what a wretch theaw art, John,

For tha pulls a long face on a Sunday;

An', to prove what tha says, tha does o' 'at tha con

To rob thi poor nayburs on th' Monday.

What business has theaw to go battin' thi wings.

An' crowin' on other folks middin?

Doesta think thi black brothers sich mean cringin' things

As to give up their whoams at thy biddin'?

An' tha's th' cheek to thank God, when tha meets wi' success,

As iv He stooped stooped to sanction sich wark!

Neaw one would ha, thowt 'at tha couldn't ha' done less

Than to keep sich loike actions i' th' dark.

Iv tha meons to go on wi' committin' these sins—

Sins tha'll ne'er get weshed eawt or forgiven—

Tha should try to keep matters as quiet as tha con,

An' ne'er let em' know up i' heaven.

Tha wur allus a bullyead, i' thi best o' thi days;

An' this ole thi nayburs must know;

An', tho' tha seems pious, an' pulls a long face,

They con manage to see through it o.

But when tha goes sneakin' an' tries to cheat God,

It strikes me tha'rt goin' to' far.

Aw'm noan mitch surproised at thi impudence, John;

Aw'm only surprised heaw tha dar!

What business has theaw to be sendin' eawt thieves,

To steal slices off other foalks' bread?

It would look better on thee to rowl up thi sleeves,

An' work for thi livin' instead.

Aw' tell thi what John—an' tak' notice o' this—

Tha ne'er knew a nation to thrive,

Wheer th' bees preferred feightin' to good honest wark;—

They're like drones stealin' honey fro' th' hive!

Iv tha's th' sense ov a jackass tha'll tarry awhoam,

An' keep th' own garden i' fettle;

But tha'd rather be eawt wi' thi Bible an' gun,

An' robbin' some other mon's kettle.

Neaw drop these mean tricks—this contemptible wrong,

An' behave a bit more loike a mon;

Or aw'll gie thee another warm dose before long,

For aw'm gradely ashamed on thee, John!

Sam Laycock. |

WEEP on! weep on! a People's tears are due;

We've lost a friend, right noble, brave, and true.

No traitor he, to flatter, then deceive;

No, 'tis for honest worth that now we grieve.

'Tis meet and right that we our sorrows blend,

For Richard Oastler was the Poor Man's Friend.

Time, wealth, and influence—all he freely gave,

To snap the fetters of the Factory Slave.

O ye, who like myself were doomed to toil

In pent-up rooms, 'mid stench of gas and oil—

Bone, blood, and muscle, time and talent given—

Shut from the pure, the blessed air of heaven—

Think of the boon his pen and tongue secured,

The insults, jeers, and hardships he endured.

Think of the time when children, young in years,

Paced the dark streets, their eyes bedewed with tears;

Dragged from their beds, their labour had begun,

Long ere those eyes beheld the morning sun.

Their feeble limbs were clammy still with sweat,

When that bright orb had run his course and set.

No time for needful rest or healthful play,

On, on they toiled from weary day to day.

Their cheeks, once ruddy, now were sunk and pale,

And crowded graveyards told a mournful tale;

For, ere brave Oastler raised his arm to save,

Poor worn-out childhood found an early grave.

But, oh! a brighter day has dawned, and now

The youthful toiler wipes his sweaty brow,

And leaves his workshop at an early hour,

E're the cold dew hath shut his favourite flower.

The workman now, his daily labour o'er,

Can trim the garden at his cottage door;

Draw up his chair beside the chimney nook,

And spend an hour in poring o'er some book;

Or with the poet soar on fancy's wing,

And learn from him how sweet it is to sing.

Read how the man with patriotic zeal,

Gives time and talent for his country's weal;

How the philanthropist leaves home and friends,

And, like his Lord, o'er human frailty bends.

At close of day the labourer can repair

O'er hill and dale, midst prospects bright and fair.

Far in the west the gorgeous setting sun

Sinks to his rest like one whose work is done;

While from the eastern hills, the moon's pale light

Heralds her advent as the Queen of Night.

Above the head, the gold-tinged clouds are seen;

Beneath the feet, a carpet fair and green.

He hears the milkmaid chant her simple air,

The good old farmer offer up his prayer;

And he recalls to mind that happy day

When first his mother taught her child to pray;

And though she's dead, he thinks he sees her now,

With silvery hair smoothed o'er her wrinkled brow,

And hears that well-known voice say tenderly

"Prepare, my son, prepare to follow me."

He hastens home, a tear is in his eye;

But, though he weeps, his soul is filled with joy.

Dark brooding care that preyed upon his mind

Is now dispelled, and wisely left behind;

Gone is the downcast look and manner strange;

His evening's walk has wrought this happy change.

All honour to the men whose tongue and pen

Secured this precious boon to toiling men—

The leisure hour, the season doubly fair,

To roam the fields and breathe the balmy air.

Brave men were these—they toiled and laboured hard,

Until at length success was their reward.

A thousand blessings on thy hoary head,

Thou veteran "King!" What, though thy spirit's fled,

Thy name shall live amongst the good and brave,

And thousands yet unborn will seek thy grave

With grateful hearts, to drop a tear or two

On the green sod that hides thee from their view.

Crowd round his tomb, ye youths and maidens fair,

For, oh! a noble-minded man lies there!

When such an one as Oastler was departs,

His greatest monument is grateful hearts.

Sam Laycock. |

|

BEN BRIERLEY

AND SAM

LAYCOCK

MEET AT BLACKPOOL.

(An extract from "Adventures at Blackpool" by

Ben Brierley, 1881.)

We coome to an owd-fashint sort of a heause, wi' a churn-milk-and-traycle-coloured

front, ut I could see wur co'ed "Oak Cottage," an' ut somb'dy o' th'

name o' "Samuel Laycock" lived at it, an' took likenesses. A

mon ut favvort bein' made eaut o' humbrell wire wur potterin abeaut

amung some picthurs ut wur in a glass case fixed to th' railins i'

th' front o' th' heause. He're stript in his shirt sleeves,

an' wur bare-yead. Thinkin' he met tell me summat abeaut

thoose ut lived theere, I axt him if he knew Sam Laycock. He

said he thowt he did.

"Is he owt akin to him ut writes po'try? " I axt.

"Th' same potato," he said.

"Never, surely!" I said.

"Yo'n find they're booath one."

"Dost think I could get to have a peep at him?" I said.

"Well, if yo'n mak' yor hont into a telescope, an' look at me,"

he said, "yo'n see his wife's husbant." An' he gan me a squint

eaut of abeaut th' twentieth part o' one e'e, as if here usin a

spyin'-glass hissel'.

"Theau doesno' say!" I said, quite in a gloppent way.

"Well, I'm fain t' see thee, owd lad!—that I am. Let's

have a wag o' thy pen-howder." An' we shaked honds heartily,

while Sam Smithies wur lookin' at th' likenesses. "An' theau

writes po'try?"

"A bit; sometimes."

"Dost think theau could manufactur a line or two abeaut

me?" I said.

He twitched up his snuffer as a hoss does it tail when flees

are plaguin' it; an' givin' me another pin-yead look eaut o'th'

telescope peeper, said—

"I'll try."

"Blaze away, then," I said.

He scrat his toppin abeaut a minit, an' then he said—

|

Ther' coome a stranger to my dur;—

At fast aw wondered who he wur;

But when aw seed his knobbly pate,

Thinks aw t' mysel'—that's Ab-o'-th' Yate. |

"Brayvo!" I said. "Po'try an' fortin-tellin' come'n as

nattural to thee as atin' and drinkin'. But theau'rt no' doin'

mich i' th' jingle line neaw, I think?"

"Nawe; I ha' no time," he said. "Folk ut come a-seein'

me, an' stoppin' at my heause—I tak' in visitors, yo' seen—find me

as mich as I con do wi' takkin their likenesses. Th' day's

rayther too far gone neaw, or else I could like t' ha' ta'en

someb'dy's ut I've been wantin' to see a good while."

"Wait till t' morn, an' theaus't have a fling at me," I said;

"an, I'll bring this tother chap wi' me. I darno' tell thee

whoa he is neaw; but he's a great mon!"

"Is he?" Laycock said, wi' another screwin up o' one side of

his jib.

"Ay," I said, "theau'll be surprised when theau yers his

name." An' wishin' one another a good afternoon we parted for

t' meet again th' day after.

[Ed. - after several adventures, Brierley, wife and friends

return to Laycock's studio to have their "picthurs" taken . . . .]

This londed us into Sam Laycock's "portergraphtin" place, as eaur

Sal coes it, where we fund th' owd lad just finishin off a sleepy

babby, ut wur bein' takken becose th' mother thowt it wur so mich

like an angel it met no' tarry here lung. I conno' tell what effect

fittin' it wi' a pair o' wings would ha' had, but—well, it's no use

hurtin' th' woman's feelins. Hoo looks at her own wi' a mother's

e'en, I reckon.

"Do I see th' owd rib?" Sam Laycock said, puttin' eaur Sal at th'

end o' his telescope.

"Ay, th' owd stockinmender," I said; an' they shaked honds. "An'

this is that Sam Smithies theau's yerd tell on."

"What, him ut paid for that pop i' Lunnon?" Laycock said, puttin'

his new acquaintance under th' fire of his peepin'-battery.

"Th' same owd swell, an' this lady's his wife." Then ther a general

paw-waggin' followed.

"Shall I ha' th' pleasure o' takkin' o yo'r likenesses?" Laycock

said, snifterin a good netful o' fish.

"Theau may tak' these women an' his yorneyship," Sam Smithies said;

"but if anybody ever taks me it'll be when I'm asleep. I dunno'

believe i' sich vanity."

I hardly think Laycock looked so weel pleeast at that, though he

said nowt, but begun a preparin' for wark. Sam's wife wur takken th'

fust, an' very nice an' lady-like hoo looked, wi' a book before her

an' a garden beheend her. It strikes me there's a deeal moore books

figure'n i' likenesses than ever wur read. When it coome to eaur

Sal's turn there a regilar commotion i'th' place. Heaw must hoo be

takken? Sittin' or stondin'? Wi' her bonnet on, or bare-yead? What

must hoo do wi' her arms, an' heaw must hoo shape her face? I said I thowt hoo'd best sit, an' keep her bonnet on, as it would look moore

becomin' her years. If hoo'd had a "Dolly Varden" hat on hoo'd ha'

bin as grand as a pot shepherdess.

"There's a lady stoppin' wi' us ut has one," Laycock said; "I dar

say hoo'd land it for a job o' this sort."

"Fotch it then," 'I said, "an' let's decorate th' owd picthur

gradely."

No sooner said than done. Laycock shot into th' heawse like a

tooth-drawer, an' th' next minit he're back again, bringin' with him

a hat ut favvort bein' made for bakin' loaves in. Eaur Sal had her

bonnet off in a crack, an' th' hat i'th' place on't. Bein' witheawt

shinnon, hoo'd nowt to tilt it forrard with, so we geet a coffee cup

an' stuck that under, an' rare an' gallus th' owd crayther lookt as

hoo sit theere.

"What mun I do wi' my honds, Mesther Laycop?" hoo said, balancin'

her hat like a meauntebank balancin' a pow.

"Put one upo' th' table an' th' tother upo' yo'r knee," Laycock

said. An' he popt his yead under a little pall, an' surveyed th' owd

ticket through his machinery. "Con yo manage to sit still?"

"Not if eaur Ab keeps pooin' his face at me," hoo said, wrythin' her

meauth abeaut.

I wurno pooin' my face at her. I're nobbut doin' my best to look as

if I hadno' tasted drink."

"Oh," I said, "I'll goo into th' fowt if yo' conno' get on wi' me

bein' here;" so I sidled to th' dur, wheere I could peep, an' watch

heaw things wur gooin' on.

Laycock twitcht his yead fro' under th' little pall, an' lookin' at

eaur Sal, said—

"Yo're skennin', Missis."

"Whoa con help it," th' owd lass said, "when they'n getten a tae

sarvice o'th' top o' their yead?" Then hoo tried to set her e'en as

straight as hoo could, an' fix hersel' like a clockcase.

"Look at this," Laycock said, puttin' his finger on a nail yead ut

wur stickin' eaut o'th' corner of a cubbort.

"Ay, well, I see it," eaur Sal said, followin' Sam's finger

wi' her e'en. "It looks like a nail yead."

"Well, keep lookin' at it till I tell yo' to stop," Laycock said;

an' he darted under th' little pall again.

"I conno' mak it int' nowt nobbut a nail yead, chus heaw I look at

it," th' owd rib said, thinkin' hoo're bein had on th' stick.

"Yo' may no' just neaw," Laycock said; "but if yo'n look lung enoogh

yo'n see it turned into a diamond pin." Then didno' th' owd gel

stare?

While hoo're watchin' for th' change ut would never happen Laycock

took aim with his machine, keaunted twenty, an' then said o wur

o'er; but eaur Sal said hoo wanted to see th' nail yead change int'

a diamond pin. Heawever, as Sam towd her it met tak' a milliont

year, an' happen a day or two beside, hoo could see through it o. Th'

owd lad winked at me, an' said hoo met leeave her seeat, an' goo an'

join Sam Smithies' wife i'th' heause; he shouldno' be above ten

minits. As for me, he thowt I'd best come another day, an' tak' a

lesson off th' order o' Good Tremblers, or summat he co'ed 'em, an'

I should mak' a nicer picthur'.

I're quite inclined for takkin' his advice.

"I reckon it's as chep sittin' as stondin'," Sam Smithies said, as

soon as Laycock had shut hissel' up in his dark hole. An' he

dropt his carcase upo' th' cheear ut eaur Sal had just laft, an' wur

asleep i' two minits.

"Neaw for it!" I said to Laycock as soon as he popt eaut of his den:

"this mon said whenever he'd his likeness takken it ud be when he're

asleep; so neaw there's a chance. Get that magic lantern ready, an'

have a shot at him. Eh, what a picthur'!"

An' he wur a picthur' too. His chin had dropt upo' his shoother, an'

his face wur poo'd eaut of o human shape, as if it had bin made o'

indy-rubber, wi' his bottom lip hangin' deawn like a leather apporn. I just lifted his hat up quietly (he wore a straw un, like a

sailor), un raked his yure deawn o'er his e'en; an' if yo' could ha'

fund owt like him eautside "Sot's Hole," I'd ha' forfeited my clogs. Laycock had th' likeness takken in a snifter, an' just as he're

hoidin' hissel' i'th' little dungeon Sam Smithies wakkent.

"Come, Ab; this boat," he said, givin' his clooas a shake: "a bit of

a blow'll do us good." An' just then he see'd hissel' i'th' lookin'-glass. "Theighur!" he said, "I'm a bonny lookin' article at anyrate. I

should mak a rare picthur' for a tap-reaum shouldno' I, Ab?"

"Ay," I said, "thee o' one side, an' owd Blucher o'th' tother. It ud

be th' makkin' o'th' Owd Bell." Little did he think he'd find hissel'

hung theere afore he're mony days owder. |

―――♦―――

|

THE WRECK OF THE "MEXICO."

BY

JAMES EDWARD ARCHIBALD.

[Ed.―see

also Laycock's Tribute to the

Drowned and Prologue.]

The barque Mexico. |

|

THEY fell not on field of battle, the

heroes I sing today;

They died not amid the turmoils and bloodshed of warlike fray;

They fought not with angry foemen; they faced no glittering steal;

And the sound they heard when dying was not artillery's peal.

The scene of their many conflicts was the boundless treacherous sea;

The turmoils that swept around them was the winds' high revelry;

The foe they fought was the storm fiend; they faced his artillery

dread,—

The rolling, roaring thunder, and the lightening flash o'er-head,

Old England reveres her heroes, and round each honoured name

She twines in loving remembrance the fadeless laurels of fame;

And I wot no braver worthies are named in that long array

Than the noble Lancashire heroes whom a nation morns to-day.

'Twas a night in bleak December, wintery, squally, and cold;

On land blew the storm-wind chilly, whistling o'er hill and wold;

The housewife piled still higher the coals in them glowing grate,

And sighed, with womanly pity, for the homeless and desolate.

But 'twas out on the angry ocean that the storms attained its

height;

'Twas there that the howling tempest showed most its relentless

might.

It hastened away from the north-west right over the sea to roam,

Chasing the scudding billows, and cresting their peaks with foam.

The fishers of Southport and Lytham and fair St. Annes-on-the-Sea,

Looked out o'er the troubled waters that where wild as wild could

be;

They saw the gale was increasing and growing in strength each hour,

And they thought of the luckless sailors who were feeling its

fearful power.

And from many a hardy fisher as he hurried towards his home,

And turned his back on the tempest and the mass of seething foam,

There went up prayer to heaven for all those who might be

Battling fiercely and bravely for their lives on that awful sea.

But look! what means that signal now cleaving the wintry air?

Look! can your eyes discern it—miles away over there?

And, see, there goes another! a line of light, a streak!

What is it? Is it a signal, or only a meteor's streak?

Ask of the sturdy fishers as down from their homes they pour:

Ask of their wives and children as they gather along the shore.

They have no need to question, they have no need to guess,

For well they know those are tokens of some vessel in distress.

And then came a consultation—what was it best to do?

Was there a chance to reach her and rescue the shipwrecked crew?

The fishermen looked on the ocean—a wild and awesome scene—

And they felt the breath of the tempest, cruel and piercing keen;

And then they gazed at the signals and thought of the sailors'

lives;

And then they gazed at their homesteads and thought off their

children and wives;

And then they looked towards the boathouse where they knew their

lifeboat lay.

Ready to cleave the waters as she had done before that day.

Was there a coward among them? Was there and arrant knave

Unwilling to face the conflict, to battle with wind and wave?

Was there a frightened fisher in all that company

Afraid or unwilling to venture out on that angry sea?

Was there among the women a single anxious wife

Who begged of her fisher husband not to risk his precious life?

Was there a loving mother who urged her only son,

To let the deed of daring by other than he be done?

No, for Lancashire sailors are brave as any on earth;

No, for Lancashire women are women of sterling worth;

Lancashire's sons and daughters are noble and bold and true;

Lancashire's sons and daughters in danger dare and do.

Southport, St. Annes and Lytham, each her lifeboat manned

And soon they were out on the ocean fast leaving behind the land;

And the crowds on the sea-shore gathered, right lustily cheered each

crew,

And eagerly watched their progress until they were lost to view.

It was three hours after midnight when the watchers on Lytham beach,

Scanning the raging waters as far as the eye could reach,

Out in the hazy distance, distinguished amid the foam

The form of their cherished lifeboat, the Charles Biggs,

heading for home.

And as through the storm and the darkness the tight little craft

drew near

From the good folks of Lytham there went up cheer after cheer;

And the men in the lifeboat shouted to let their comrades know

They had saved the whole of the sailors of the wrecked ship

Mexico.

But, alas! no sounds of cheering were heard at St. Annes-on-the-Sea,

For no signs of the Laura Janet filled the watchers' hearts

with glee;

And the anxious fishers and women who wandered alone the shore

Saw nought but the white-tipped breakers, heard nought but the

tempest's roar.

Wearily, sad and slowly passed the long hours away

Until in the east horizon appeared the first glimpse off day;

And from many a sorrowing watcher, oppressed with grief and care,

There rose to the God of waters an earnest and heartfelt prayer:—

"O God of the earth and the heavens! O Maker of sea and land!

Who holdest the boundless ocean in the hollow of Thine hand!

Bring back to us all our dear ones, and calm this troubled sea

As Thou didst in long-past ages the waters of Galilee!"

But vain was all expectation, and vain was each searching glance

The fishers that dreadful morning cast over the broad expanse;

The fears of the doubtful grew stronger, and ere the close of the

day

The hopes of the lightest-hearted to anguish and grief gave way.

From the panic-stricken Southport there came the sorrowful tale

That twenty-seven brave heroes had died in that awful gale!

St. Annex' ill-fated lifeboat hand lost the whole of her crew,

And Southport's Eliza Fernley had lost all hers save two.

Then over St. Annes and Southport the pall of affliction lay

Like a gloomy cloud rain-laden in the sky on a winter day;

And mothers, fathers and children, sisters, brothers and wives,

Mourned for the men who had perished in trying to save men's lives.

And when through the whole of Britain the terrible tale was heard,

The nation's pulse was quickened and the nation's heart was stirred;

And the wealthy gave of their plenty, and the poor of their earnings

small,

To keep from poverty's clutches the bereaved who had lost their

all.

Old England reveres her heroes, and round each honoured name

She twines in loving remembrance the fadeless laurels of Fame ;

And I wot no braver worthies are named in that long array

Than the Lancashire heroes who perished at duty's call that day. |

<>

|