|

"I found him a

stalwart son of toil, and every inch a gentleman. In cast of face,

he recalls Tennyson somewhat, though more bronzed and browned. He is

as sweet and gentle as a woman in manner, and recited some beautiful

things of his own with a special freshness to which one is quite

unaccustomed."

Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

"He waited quietly until he felt the spirit of that which he

was about to do come upon him. Then he was as one possessed,

everything but the poem was forgotten, but that he made live, or

perhaps I should more truly say that he incarnated it; he actually

became the poem himself. His features changed with every expression

of the verse, his hands, nay, even his fingers, expressed the

meaning of the words, and that meaning thoroughly revealed itself.

It was far beyond what you had thought of, but it stood out clear

for you ever afterwards."

Robert Spence Watson, on Skipsey's recitation.

|

|

|

|

JOSEPH SKIPSEY,

"The Pitman Poet."

(1832-1903)

"GET UP!"

the caller calls, "Get up!"

And in the dead of night,

To win the bairns their bite and sup,

I rise a weary wight.

My flannel dudden donn'd, thrice o'er

My birds are kiss'd, and then

I with a whistle shut the door

I may not ope again.

______________________

THE stars are

twinkling in the sky,

As to the pit I go;

I think not of the sheen on high,

But of the gloom below.

Not rest nor peace, but toil and strife,

Do there the soul enthral;

And turn the precious cup of life

Into a cup of gall. |

|

|

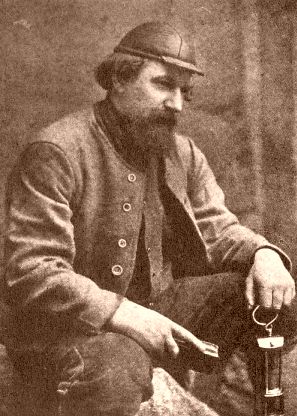

JOSEPH SKIPSEY was born

March 17, 1832, in Percy Main, Northumberland, the eighth child of Cuthbert

Skipsey (d. 1832) and his wife, Isabella. He began colliery

work at seven years of age (disregard nine in the Times

obituary)

as a 'trapper,' opening and closing ventilation doors.

During the long shifts, Skipsey taught himself to read and write using

discarded playbills and advertisements, swiftly graduating to Pope,

Milton, Blake, and Shakespeare. He soon began to compose his own

poetry, publishing his first poems in local

newspapers.

Skipsey's first poetry volume was published in Morpeth in 1859, but no copy is known to be extant. It did, however,

attract the attention of the editor of the Gateshead Observer who

found Skipsey employment as an under store-keeper, one of a number of

opportunities he had to leave the harsh conditions of life as a

miner, but this and other occupations away from the mines were to prove

uncongenial.

Skipsey met his wife during a visit to London in 1854.

Sarah Ann Fendley, was born at Watlington, Norfolk; she became his lifelong

companion and was to bear him eight children. |

|

A SONG

in devotion I sing to my Annie—

Ah! be startled not to discover I long,

To fold in my arms and possess what so many

And many a time is the theme of my song.

My manhood's dissolved at the sight of thy beauty,

And while heart can feel and such beauty is known,

What youth could be kept by a mere sense of duty

From yearning to call the enchanter his own?

The saint he may blame—so to do is the fashion—

And carp at my feelings and call them a sin;

Could beauty like thine be the price of his passion,

He'd rush to perdition the jewel to win.

To view thy locks blacker than coal and thy glances;

To hear thy voice, sweetest of music—ay, ay—

Thy manifold beauty my spirit entrances,

And reason deserts me when Annie is nigh!

|

|

|

In 1863, following a fatal accident to one of his

children, Skipsey moved to Newcastle, where Robert Spence

Watson secured him a job as assistant librarian to the

Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. But the work

did not suit him, the pay was poor and he returned to work in the mines

where he remained until 1882. Skipsey's biographer, Spence Watson, wrote of his

abilities as a librarian thus . . . .

"It must be admitted that he did not fill the appointment in an

altogether satisfactory way. As a rule a librarian must know where

his books are, and he must know something of what is inside them and be

able to satisfy the wishes of members who desire to refer to them, or to

borrow them, but perhaps the less a sub-librarian knows of the inside of

books the better. At all events, Skipsey ... would become

absorbed in some passage of a well-known author, and he would scarcely

recognise the eager and impatient member who wished for his services

forthwith. So before a year had passed he naturally grew

discontented and unhappy, and his friends had many a discussion as to what

the best line of action really was. ... His friends at length

advised him to return to the coal-mines, and he did so, and worked

patiently hewing for many a year."

In 1883, some twenty years after he had left the post of assistant

librarian, Skipsey returned to the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical

Society to deliver a lecture, 'The Poet as Seer and Singer'. He was to

publish two further poetry collections; the first, 'Carols

from the Coalfields' (1886), drew praise from

Oscar Wilde, who likened the poems to those of William Blake.

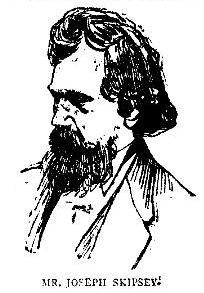

Following his meeting with Skipsey, the artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti noted:

"I found him a stalwart son of toil, and every inch a gentleman.

In cast of face, he recalls Tennyson somewhat, though more bronzed and

browned. He is as sweet and gentle as a woman in manner, and

recited some beautiful things of his own with a special freshness to which

one is quite unaccustomed."

In recognition of his literary work, Skipsey was awarded an annual civil

list pension of £10, later increased to £25. Another outcome of his

growing literary reputation was that Walter Scott (of Newcastle) engaged

Skipsey as the first general editor of the "Canterbury Poets" series.

His introductory essays,

especially that on Robert Burns's Poems and Songs show particular insight. |

|

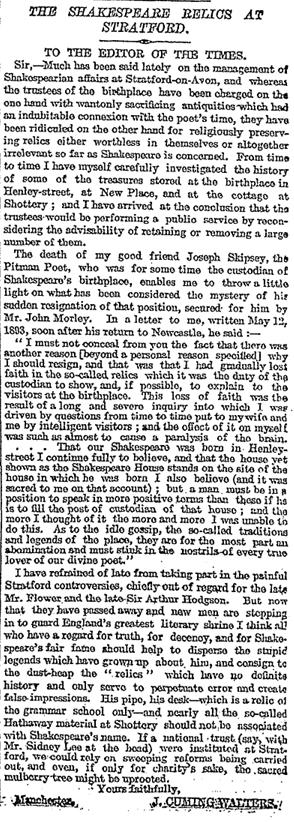

Shakespeare's birthplace in Henley Street (ca. 1900).

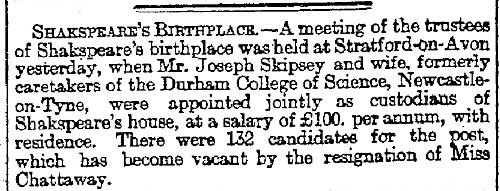

Birmingham Daily Post, 10th

June, 1889.

|

|

|

Pall Mall Gazette, 1889. |

|

|

In 1889 Skipsey was appointed custodian of Shakespeare's birthplace at

Stratford-on-Avon on the recommendation of Burne-Jones, Tennyson, Rossetti,

Bram Stoker and other eminent men, but he left after two years, writing to a

friend — he asked for the letter not to be published until after his death —

that the chief reason why he had resigned was because he had gradually lost

all faith in the so called relics which, as custodian, it was his duty to

show, and if possible explain to the visitors at the birthplace.

How is it that none of the relics have any definite history, and only serve

to perpetuate error and create false impressions?. . . .

"About ten years ago Mr. Joseph Skipsey, who for some

considerable time had been a highly esteemed custodian of the so-called

birthplace [Shakespeare's] in Stratford (placed there on the

recommendation of Mr. John Morley) suddenly and unexpectedly

resigned his position and left town. It appears, however, that

he made an explanation at the time in writing which he entrusted to a

friend, but with the injunction that nothing should be divulged to the

public concerning it until after his death. He died in 1903.

In The Times newspaper (London), of recent date we now have a full

statement of the case in Mr. Skipsey's own words. He

resigned in effect because he was disgusted with the innumerable frauds to

which he found himself committed there in the discharge of his official

duties. As to the relics, he expressly declared that they had

become on thorough investigation a 'stench in his nostrils.'"

—The Truth

concerning Stratford-on Avon, by Edwin Reed. |

|

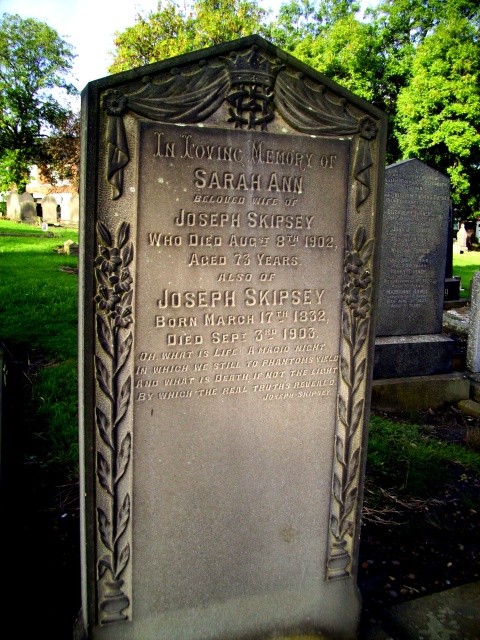

After relinquishing his post at Stratford-on-Avon,

he and his wife returned to their roots in the North East of England

where they spent the remainder of their lives, living on his pension and

helped by their children with whom they lived in turns. Sarah Skipsey

died in August 1902 and Joseph died in the house of his son Cuthbert at

Low Fell, Gateshead, on the 3rd September 1903, aged seventy-one. He was

interred in Gateshead Cemetery. Two of his five sons and the eldest

of three daughters survived him.

Photo courtesy Anthea Lang.

OH,

what is Life? A magic night

In which we still to phantoms yield;

And what is Death, if not the light

By which the real truth's reveal'd? |

A brief obituary appeared in The Times

. . . .

|

Mr. JOSEPH

SKIPSEY, a well-known

North Country writer, has died at his residence, Low Fell, near

Newcastle-on-Tyne, in his 71st year. Mr. Skipsey,

who was well known as the "Miner Poet," was born at Percey Main, and

during the greater part of his life worked in the mines, going below

the surface at the age of nine years. In 1880, through the

influence of Mr. John Morley, M.P., and Dr. Spence Watson

he was appointed caretaker of Shakespeare's house, Stratford-on-Avon,

but afterwards returned north. Mr. Skipsey, who was

self-educated, published five volumes of verse. |

Skipsey's best work is that written during the period before

he achieved the literary success of the 1870s that drew him away from his

family roots and the colliery life that he knew.

|

DEAR

critics, pray, what have I done

That thus you frown so? tell me truly?

"You've for your neck a halter spun,

In blaming of our race unduly!" |

Rossetti described

"Get Up!" as "equal to

anything in the language for direct and quiet pathetic force";

indeed, the strength of Skipsey's poetry lies in the direct simplicity of

his language and expression of feeling,

much of

which is evident in "The Hartley Calamity"

(1862), a powerful and affecting ballad in which

he recounts

the tragedy of the 204 men and boys (most of

the male population of the village) who

suffocated in the colliery after a six-day struggle to dig them out .

. . .

|

"Are we entombed?" they seem to ask,

For the shaft is closed, and no

Escape have they to God's bright day

From out the night below.

.

.

.

.

"O, father, till the shaft is cleared,

Close, close beside me keep;

My eye-lids are together glued,

And I—and I—must sleep."

"Sleep, darling, sleep, and I will keep

Close by—heigh-ho!"— To keep

Himself awake the father strives—

But he—he too—must sleep.

.

.

.

.

And fathers, and mothers, and sisters, and

brothers—

The lover and the new-made bride

A vigil kept for those who slept,

From eve to morning tide. |

|

|

Simplicity of style also comes to the fore in Skipsey's many homely

and endearing vignettes of

the colliery village life of his times, such as in "Willy

to Jinny", "Kit never went down", "The

Collier Lad", "Mother wept", and "Mary

of Crofton".

|

THEY

cry, "How light the heart and bright,

From which proceed such strains of gladness!"

They can't discern the pangs that burn,

And seek to drive the bard to madness.

From pryers vain, he hides his pain,

And while with skill his harp he's plying,

They mark the bloom upon the tomb,

But not the ruin in it lying! |

In later life Skipsey became part of Spence Watson's wide

circle; his table talk was said to have been 'trenchant and to the point.'

In "Joseph Skipsey: his Life and Work" (T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1909) Watson recalls

Skipsey's manner in reciting poetry . . . .

"He waited quietly until he felt the spirit of that

which he was about to do come upon him. Then he was as one

possessed, everything but the poem was forgotten, but that he made live,

or perhaps I should more truly say that he incarnated it; he actually

became the poem himself. His features changed with every expression

of the verse, his hands, nay, even his fingers, expressed the meaning of

the words, and that meaning thoroughly revealed itself. It was far

beyond what you had thought of, but it stood out clear for you ever

afterwards."

――――♦――――

The Times

8th September, 1903.

――――♦――――

|

Kit never Went Down.

NO, Kit never went down into

Halliwell town,

But he flung at each lover a jest,

Till he Nan the brunette on a merry eve met,

When his pride it was put to a test.

The youth gave her a wink, she returned with a

blink

That conquered his heart and possest;

And when next he went down into Halliwell town,

He went with a rose in his breast! |

|

|

Corrections.

Ed.—Skipsey's

great grandson, Roger J. Skipsey, has kindly provided the following information

(see also Family Documents) which

corrects the factual errors that appear in the biographic sketch by

Basil

Bunting:

1. The date of birth given in Basil Bunting's

biographic sketch is incorrect. Skipsey was born on 17th. of March

1832.

2. Skipsey married Sarah Fendley in December 1868

(after the deaths of five of their children). Their three children

who survived into old age were:

Elizabeth Ann Pringle Skipsey b. 1860, married John Harrison;

Joseph Skipsey b.1869 married Sarah Leech (three single

daughters);

Cuthbert Skipsey b.1872 (one single daughter and Roger J.

Skipsey's father, Joseph Fendley Skipsey).

3. There is no record of sons James and William, or of

a granddaughter Jane, referred to in Bunting's sketch.

4. Joseph Skipsey died on the 3rd. of September 1903

at Cuthbert Skipsey's home at 5 Kells Gardens, Low Fell, Gateshead, not

with his daughter Elizabeth at Harraton as previously cited.

――――♦――――

|

|

Percy Main Colliery |

|

|

The following works by Joseph Skipsey are reproduced in these pages:

|

POETRY:

INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS, on:

|

|

――――♦――――

<>

|