|

|

|

EDWIN WAUGH

(1817-90)

Poet and author in the Lancashire dialect. |

"If a man was a pair of steam-looms, how carefully would he be oiled, and

tended, and mended, and made to do all that a pair of looms could do. What

a loom, full of miraculous faculties, is he compared to these—the

master-piece of nature for creative power and for wonderful variety of

excellent capabilities! Yet, with what a profuse neglect he is cast away,

like the cheapest rubbish on the earth!"

EDWIN WAUGH.

"His poems have great

lyrical beauty and intimate tenderness and charm, nor is there

lacking that homely humour and heart-stirring pathos which finds

their best medium in dialect."

MAY YATES, "A LANCASHIRE

ANTHOLOGY" (1923).

"Any valid estimate of his merits must proceed

upon the assumption that he is provincial. He never regarded

himself as anything else. He is intentionally and deliberately

local. His subjects all spring, so to speak, from his native

soil; and he is always at his best when he uses the dialect of the

county in which he was born. In short, he asked for no higher

honour than to be entered on the roll of Lancashire writers; and

among these he holds a place of undisputed eminence."

GEORGE MILNER,

Introduction to "Lancashire Sketches"

――――♦―――― |

|

The following is extracted from. . . .

A Garland of

Lancashire

Prose

by

G. Halstead Whittaker. [1]

Waugh is

the prince of Lancashire dialect poets. He sings of the

moorlands, the breezes of which blow healthy spirits through the

characters that people his pages.

|

"In the black profound between, we heard the lake

lashing its rocky shore; but nothing of it was visible. The scene was

gloomily grand. I would not exchange the robe of stormy

darkness which Ennerdale wore that night for all that sunlight can do to

make it gay. The wild changes of weird light which stole from the moon

through those flying clouds made the view more savage still. We

laboured along the splashy road, through everything that makes a man

damp, but the wild sublimity of the scene repaid for all."

Ennerdale, from. . .

Rambles in the Lake Country. |

He was born at Rochdale, January 29th, 1817. His

father's ancestors were Northumbrian, his grandfather settled in

Rochdale, where he married a Lancashire lass. When nine he

lost his father, and some years of poverty ensued. At twelve

he became an errand boy for a printer, and two years later was

apprenticed to another printer. His apprenticeship completed

he worked in the trade in various towns for six years—London, Durham

and Wakefield—then returned to Rochdale. |

|

". . . the parish looks, when

seen from some of the hills in the immediate neighbourhood,

something like a green sea of tempest-tossed meadows and pasture

lands, upon which fleets of cotton mills ride at anchor, their brick

masts rising high into the air, and their streamers of smoke waving

in the wind."

A view of Rochdale, from . . .

Sketches of Lancashire Life. |

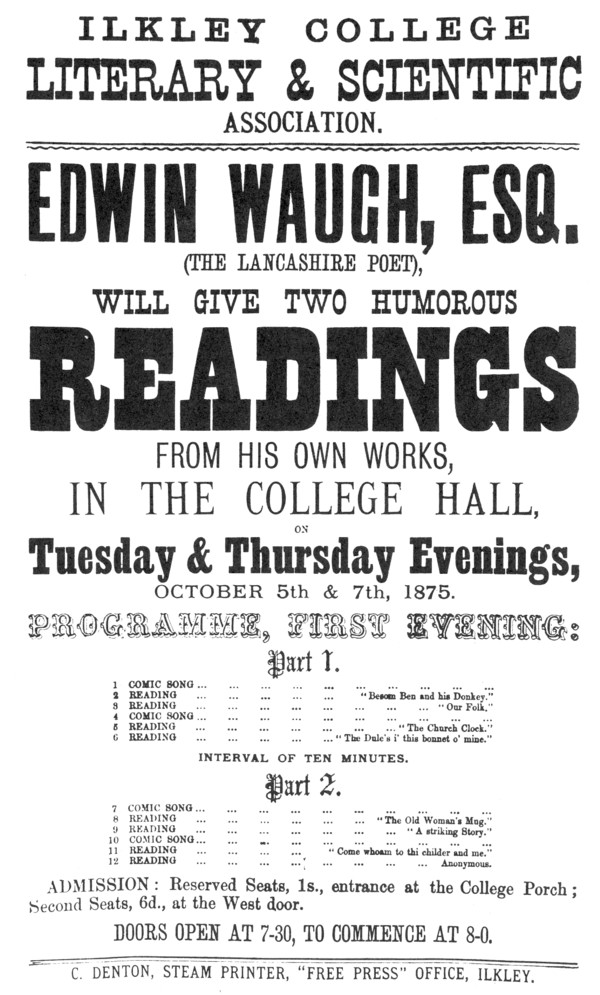

In 1847 he left the trade to take up secretarial work. His

literary work began in 1852, and his most famous poem "Come whoam

to thi childer an' me" was written in 1856 on the leaf of a

diary in the Clarence Hotel, Manchester, Friday, June l0th. |

|

COME WHOAM TO THI CHILDER AN' ME.

* |

|

Aw've just mended th' foire wi' a cob;

Owd Swaddle has brought thi new shoon;

There's some nice bacon-collops o' th' hob,

An' a quart o' ale-posset i' th' oon;

Aw've brought thi top-cwot, doesta know,

For th' rain's comin' deawn very dree;

An' the' har-stone's as white as new snow;

Come whoam to thi childer an' me.

When aw put little Sally to bed,

Hoo cried, 'cose her feyther weren't theer,

So aw kiss's the' little thing, an' aw said

Thae'd bring her a ribbin fro' th' fair;

An' aw gave' her her doll, an' some rags,

An' a nice little white cotton-bo';

An' aw kiss'd her again; but hoo said

'At hoo wanted to kiss thee an' o.

An' Dick, too, aw'd sick wark wi' him,

Afore aw could get him upstairs;

Thae towd him thae'd bring him a drum,

He said, when he're saying' his prayers;

Then he looked i' my faze, an' he said,

"Has the' boggarts taen houd o' my dad?"

An' he cried whole his e'en were quite red;—

He likes thee some weel, does yon lad! |

At the' lung-length, aw geet 'em laid still;

An' aw hearken't folks' feet 'at went by;

So aw iron't o' my clooas reet weel,

An' aw hang'd 'em o' th' maiden to dry;

When aw'd mended thi stockin's an' shirts,

Aw sit deawn to knit i' my cheer,

An' aw rayley did feel rayther hurt,—

Mon, aw'm one-ly when theaw artn't theer.

Aw've a drum an' a trumpet for Dick;

Aw've a yard o' blue ribbin for Sal;

Aw've a book full o' babs; an' a stick,

An' some 'bacco an' pipes for mysel;

Aw've brought thee some coffee an' tay,—

Iv thae'll feel i' my pocket, there'll see;

An' aw've bought tho a new cap to-day,—

For aw olez bring summat for thee!

"God bless thee, my lass; aw'll go whoam,

An' aw'll kiss thee an' th' childer o reawnd;

Thae knows, 'at wheerever aw roam,

Aw'm fain to get back to th' owd greawnd;

Aw can do wi' a crack o'er a glass;

Aw can do wi' a bit ov a spree;

But aw've no gradely comfort, my lass,

Except wi' yon childer an' thee." |

|

"Come Whoam"

was published next day by the Manchester Examiner and Times and was

noticed by David Kelly, a bookseller, who arranged to have it printed on

cards, one of which was given to each customer. [Also sold by Kelly and

Slater at 1d.] Baroness Burdett-Coutts saw a copy, and ordered

twenty thousand, which she distributed. The original MS.

became the property of the Manchester Literary Club. The first draft

has "Owd Roddle" on the second line. It is set to music in "Dialect

Songs of the North," by P. Delavanti. (Ed.—available under the

first Sheet Music tab at the top of this page).

|

They who, half-fed, feed the breadless,

in

the travail of distress;

They who, taking from a little, give to those

who still

have less;

They who, needy, yet can pity when they look

on greater

need;

These are Charity's disciples, ― these are

Mercy's sons

indeed.

The

Cotton Famine. |

Waugh's mother venerated John Wesley and remembered how the

preacher had smoothed her hair when on a visit to her father.

Edwin's favourite books were the dictionary and Wesley's Hymns — which

awoke the poet in him. He learned many of them, and a Welsh

neighbour gave him a penny for each hymn he could recite. From this

sound basis sprang Waugh's unmatchable Lancashire songs. His poems

are not merely words, they are an expression of the music that was in his

heart. It is fitting that so many of them are now set to music, and

sung so well by Mr. Hamilton Harris, Mr. Hugh Beech and others. The

music is often by Robert Jackson, but this is not the music they first

knew. Every song by Edwin Waugh sings itself, for in the conception

of them he collaborated with his fiddle — playing a simple air while

composing the words. He makes the fiddle much more than a musical

instrument in "Eawr Folk", a gallery of his own relatives and friends:

|

My Uncle Sam's a fiddler; an'

I fain could yer him play

Fro' set o' sun till winter neet

Had melted into day ;

For eh—sich glee—sich tenderness!

Through every changin' part,

It's th' heart 'at stirs his fiddle,—

An' his fiddle stirs his heart.

An' when he touches th' tremblin' string,

'At knows his thowt so weel,

It seawnds as iv an angel tried

To tell what angels feel. |

His "To my owd fiddle" betrays the fiddle-lover:

|

I sometimes think it's gradely wick,

There's singin' brids inside on't;

An' not a string but's swarming thick

Wi' little elves astride on't! |

In "The Old Fiddler," the opening sketch of Waugh's book

"Tufts of Heather," the old fiddler's playing of the tune "Remember the

Poor" is described in words in which Waugh the fiddler undoubtedly

predominates.

|

"Heywood seemed to rest from its labours, and

rejoice in the glory and gladness which clothed the heavens and the

earth. The long factory chimneys, which had been bathing

their smokeless tops all night in the cool air, now looked up serenely

through the sunshine at the blue sky, as if they, too, were glad to get

rid of the week-day fume, and gaze quietly again upon the loveliness of

nature; and all the whirling spinning machinery of the town was lying

still and silent as the overarching heavens. Another Sabbath had dawned

upon the world."

Heywood on Sunday, from . . .

Sketches of Lancashire Life. |

His love songs such as "Th' Sweetheart Gate" and "The Dule's

i' this bonnet o' mine" are perfect. His prose is vigorous, flecked

with words of uncommon power. Often he tells stories within a story,

such as the famous "Owd Cronies; or Wassail in a country inn," — the inn

being the Old Boar's Head, Middleton. Here Jone o' Gavelock tells

his famous tale of the Lancashire Volunteers.

|

"The Langdale road goes up through a narrow defile, between Harter Fell and

Grey Friars, where the stream is heard rushing deep below, overfrowned by

precipitous crags. Emerging from this pass, it is worthwhile to linger a

few minutes at Birk Brig. There, the stream comes down in a narrow

channel, where the rocks are worn into quaint arches, and fantastic

shapes, that might be the ruins of some water-spirit's palace. The

river settles here in pools of clear green-tinged water, beautiful

as liquid emerald. Some of these pools, or "pots," are ten feet deep."

The River Duddon near Seathwaite, from. . .

Rambles in the Lake Country. |

"A Lift on the Way" has been said to contain a sermon in

every verse:

|

Life's road's full o' ruts ; it's slutchy an' it's dree,

An' money a warn-eawt limper lies him deawn there to dee ;

Then, fleawnd'rin' low i' th' gutter, he looks round wi' dismay

To see if aught P the' world can give a lift on the way. |

His poetry reveals the nature lover. His is not a

cribbed or confined outlook. All charm of the wide sweeping moors,

fresh breezes, clear shies, and the inspiration that comes from the hills

are distilled to an exquisite degree in his poetry. Take these

stanzas from his "I've worn my bits o' shoon away."

|

It's what care I for cities grand,

We never shall agree;

I'd rayther live where the' layrock sings,

A country teawn for me!

A country teawn, where one can meet

Wi' friends an' neighbours known;

Where one can lounge i' the' market place

An' see the meadows mown.

Yon' moorlan' hills are bloomin' wild

At the' endin' o' July;

Yon' woodlan' cloofs, an' valleys green,

The sweetest under th' sky;

Yon' dainty rindles, dancing' deawn

Fro' th' meawntains into th' plain;

As soon as the' new moon rises, lads,

I'm off to th' moors again! |

The later years of Waugh's life were connected with Manchester. He

was a founder of the Literary Club in 1862. In 1876 his copyrights

were taken over by a committee, thus relieving him of the commercial

burdens of authorship. In 1882 he was granted a Civil List pension

of £90, he was then suffering from cancer on the tongue. Living at

Kersal Moor he was on the fringe of the moorland scenes he loved so well,

but for health reasons he removed to New Brighton [Ed.

― tip of the Wirral peninsula, then in Cheshire], where he died April

30th, 1890. He was interred at Kersal Church, where his personal

friends' last act was to drop sprigs of rosemary on his coffin, saying

"That's in remembrance."

|

"On the brow of Red Bank, the tower and gables

of St. Chad's catholic church overlook the swarming hive of

ignorance, toil and squalor, which fills the valley of the Irk and

which presents a fine field for those who desire to spread the

gospel among the heathen, and enfranchise the slave . .

. . Up rose a grove of tall chimneys from the dusky

streets lining the banks of that little slouchy stream, creeping

through the hollow, slow and slab, towards its confluence with the

Irwell, at Hunt's Bank . . . .

By the time we had taken a few reluctant sniffs of the

curiously-compounded air of that melancholy waste, we began to

ascend the incline, and lost sight of the Irk, with its factories,

dye-houses, brick-fields, tan-pits, and gas-works; and the unhappy

mixture of stench, squalor, smoke, hard work, ignorance, and sin .

. . ."

Manchester, as seen from a train; from . . . .

Sketches of Lancashire Life. |

The Works of Edwin Waugh, edited by Geo. Milner, were

published in eight volumes, "Sketches," "Besom Ben" and "Chimney Corner

Stories," "Tufts of Heather" and "Poems and Songs."

Dialect Writer's Memorial, Broadfield Park, Rochdale.

He is commemorated on the Rochdale Dialect Writers' Memorial, erected, as is stated below

(footnote 2), with Waugh's medallion portrait thereon

―

"In grateful memory of four Rochdale writers of the Lancashire dialect who

have preserved for our children in verse and prose that will not die, the

strength and tenderness, the gravity and humours of the folk of our day,

in the tongue and talk of the people."

Erected in the

year 1900.

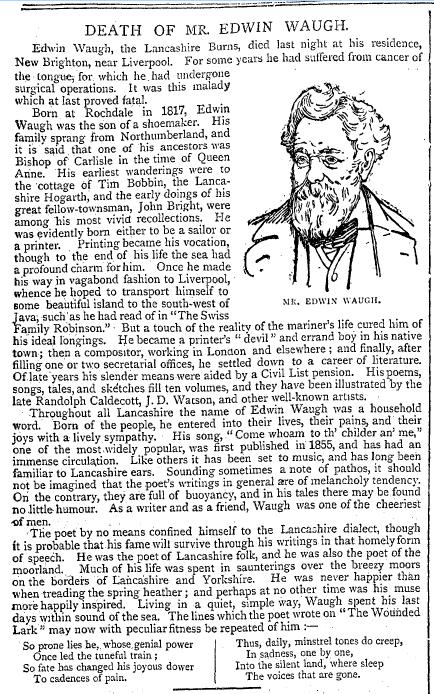

Obituary, Pall Mall Gazette, 1st May, 1890.

――――♦――――

|

EDWIN WAUGH.

BORN JANUARY 29th, 1817; DIED APRIL 30th,

1890. |

|

THOU'ST

left our choir at last,—the sweetest singer

That ever warbled o'er thy native heath!

Thy sky-notes, wild, have often made me linger,

To catch the fulness of their silv'ry breath.

Though caged within the town, thy soul was ever

Hovering fondly o'er its moorland nest;

And nought of city life thy heart could sever

From that dear land where thou hadst hoped to rest.

We're silent now, since thou hast left, and gone

To join the crowd of songsters gone before;

Prince,

Bamford,

Swain have winged it, one by one,

And songs of homely life are heard no more.

Farewell, old "layrock"! freed from earthly toil,

And anguish bravely borne, as 'twere thy cross;

Flutt'ring with broken wing o'er fields of moil,

To find thy glory in thy country's loss.

Gone are the echoes from the woods and bowers

Thou'rt won't to visit when the twilight fell,

To mingle with their melodies and flowers

Thy songs, so fragrant of the heathery dell.

We mourn thee now as one snatched from the nest,

And cast away in Death's remorseless train;

Still we're consoled to think that it were best

To die, than linger in unceasing pain.

Thou hadst deserved a better fate than this,

Whose notes have made the welkin ring with joy;

If ought there be to spare of heavenly bliss,

Thou'st earned a meed, and that without alloy.

Ben

Brierley. |

――――♦――――

|

"Dull November was

closing, sullen and sad, with wan, uncertain skies and dwindling

days, whose sombre light,—oft obscured by clouds of driving

sleet,—was hastening to its shortest span. The pallid sun

shone fitfully, with faint, cold ray, upon delightless fields—where

a few starved cattle were cropping the sodden aftermath with

listless dislike; and an air of desolation pervaded all the withered

scene. In the open country, the year's gay foliage lay

mouldering slushily in the ditches and on the lonely walks; and a

damp odour of decaying verdure sicklied the air of the little vale

which, a few weeks ago, smiled so sweetly in the floral beauty of

summer. Oft, now, across the bleak moor, sighed 'the sad

genius of the coming storm.' Keen winds that skirmish in the

van of approaching winter were beginning to wait and whistle wildly

through 'bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang;' and

in lonely woods, gaunt, leafless boughs creaked gloomily in the

blast, where no other sound was heard. Everything from earth

to sky told that before long the white shroud of the year would hide

the faded scene. The voice of the streamlet, as it hurried

cheerlessly down the hollow of the clough, between flowerless banks,

rose now with pensive tone upon the silent air; for the fields were

desolate, and the song-birds of summer were all gone,—all but the

twittering red robin, creeping nearer, day by day, to the haunts of

man with his cheerful little trill, as the weather grew colder, and

the dying year deepened into days of 'darkness and of gloominess, of

clouds and of thick darkness, even very dark, and no brightness in

it, for the land is darkened.'"

Waugh: the onset of winter, from . . . .

The Wrong Chimney. |

――――♦――――

by

Ben

Brierley.

|

The writer had not

heard from his poetical friend for a considerable time. The

circumstance suggested this epistle, which Mr. Waugh included in an

edition of his own poems. |

|

WHAT

ails thee, Ned? Thour't not as 'twur,

Or else no' what I took thee for,

When fust thou made sich noise an' stir

I' this quare pleck.

Hast' flown at Fame wi' sich a ber,

As t' break thy neck?

Or arty droppin' fithers, eh;

An' keepin' th' neest warm till some day,

Toart April-tide, or sunny May,

When thou may'st spring,

An' warble out a new-made lay,

On strengthened wing?

For brids o' sung mun ha' they mou't,

As weel as other brids I doubt;

But though they peearch beneath a spout,

Or roost 'mong heather,

They're saved fro' mony a shiverin' bout,

By hutchin' t'gether.

Come, let owd Mother Dumps a-be,

An' wag thy yead wi' friendly glee;

Fly o'er, a humble brid to see—

This wo'ld is wide—

There's reaum for booath thee an' me,

An' more beside.

Come, scrat' thy bill, an' bat thy wings;

Hark how the merry "Layrock" sings!

Good news fro' flowerlond he brings

In his glad throat;

An' conno' thou, 'mong lesser things,

Put in a note?

The buds that peep fro' every spray;

The cock that wakkens up the day;

The thrush that sings its roundelay

I' bower an' tree,

Shout—"Come, owd brid, an' have a say

I' nature's spree!"

For 'tis a spree, this life o' ours;

Drinkin' wine fro' cups o' flowers,

An' takkin' insence in i' showers,

Enoogh to crack us;

Or havin' glorious neetly cowers

Wi' a fithered Bacchus.

Fly o'er thysel, or if thou chooses

To bring some other brids o' th' Muses,

Pike out a flock, an' come an' rooze this,

My peearchin cote;

The mou't seize him who then refuses

To tune his throat.

Foremost in flight, on gentle wing,

The "Prestwich Philomela" [1]

bring.

It swells my crop to yer him sing,

I' plaintive strain;

To squeeze his claw wi' friendly wring

I would be fain.

Then ther's that owd gray-toppined lark,

Who sang when thou an' I wur dark,

Long years sin', o'er toart th' "Little Park,"

"Bamford" [2]

his name;

Let's give our years a reverent jark,

An' own his fame.

Bring in thy train thoose brids o' note,

Blithe "Charlie," [3]

with his wattled throat,

An' "Dick,"' [4]

who never sang nor wrote

To hurt his fellow;

With him, [5]

who aye wi' "seed-box" sote

To mak' brids mellow.

Bring him who to the Past still clings, [6]

Who in some moss-grown ruin sings,

Whilst delvin' deep for bygone things

I' tombs an' ditches;

Now croonin' o'er the deeds o' kings,

Or pranks o' witches.

An' bring that honest soul thy skoo' in, [7]

Who notes what other birds are dooin';

Who at a "weed" is aules pooin',

To sweel his throttle

Who if he's mute is surely brewin'

Some genial prattle.

An' bring that grizzly weazent wren, [8]

Who twitters nobbut now an' then;

Who "ale" prescribes to "physic" men,

An' brids as weel.

(If souls obeyed his guidin' ken,

They'd starve the de'il.)

An' to mak' up the festive cage,

Bring that plump brid, the "Happy Page;" [9]

Who'd give in song the exact gauge

Of throat o' viper, [10]

An' tell, by countin' fishers, th' age

O' woodland piper.

Wi' hop an' twitter, chirp an' sung,

We'd drive the scamperin' hours alung;

An' it thy glee, an' 'Lijah's lung

I' tone should slacken,

Ther'd be enoogh o' Charlie's tongue

To keep us wakken.

We'd ha' "Tim's

Grave," an "Th'

Sweetheart Gate,"

An' "Owd Pegge's" cure for th' wakkerin' state;[11]

An "Jerry," [12]

too, should shake his pate

Wi' monkey claiver;

An' if yo'rn short o' rhymin prate,

I'd croon "Th' Owd Wayver."

We mit o' love an' friendship sing;

O' Charity's exhaustless spring;

O' Beauty, that wi' radiant wing,

Charms brid and bard;

An' then, for th' sake o'th' fun 'twould bring,

Try th' jokin' "card." [13]

A neet o' sick like mirthfu' croozin',

No friend forgettin'—no foe abusin';

Now leaud i' sung, now sweetly musin',

Were "bliss divine;"

An' to the soul a deep infusin'

O' Jove's best wine.

Thus may we flutter through life's grove,

Now crack's wi' glee, now steeped i' love,

Till wingin' to that roost above,

Where dwell the blest,

We find, like Noah's faithful dove,

A place o' rest. |

____________

|

1. |

Charles Swain; author of "The Mud" and other poems. |

|

2. |

Samuel Bamford; author of "Passages

in the Life of a Radical," &c. |

|

3. |

Charles Hardwick; author of "The History of Preston," &c. |

|

4. |

R.

R. Bealey; author of "After Business Jottings," &c. |

|

5. |

Joseph Chatwood, President of the Manchester Literary Club. |

|

6. |

John

Harland; Editor of "Baine's History of Lancashire," &c. |

|

7. |

J.

P. Stokes, Esq., Correspondent of the Times. |

|

8. |

Elijah Ridings; author of the "Village Muse," &c. |

|

9. |

John

Page (Felix Folio); author of "Street Dealers and Quacks," &c. |

|

10. |

Mr.

Page, in "Letters on Natural History," maintains that the viper,

in time of danger, swallows its young. |

|

11. |

Vide "Ale versus Physic," by Elijah Ridings. |

|

12. |

Alluding to a humorous story about a "monkey," told with

considerable gusto by Charles Hardwick. |

|

13. |

A

term much used in conversation by one of the worthies above

named. |

――――♦――――

FOOTOTES.

1. A more comprehensive account (to that

above) of Waugh's life and writing is given by George Milner in the 'Preface

and Introduction' to his edition of Waugh's "Lancashire Sketches".

2. The

Dialect Writer's Memorial (shown above) is dedicated to four Rochdale dialect writers:

Oliver Ormerod (1811-79), Edwin Waugh (1817-90), Margaret Rebecca Lahee

(1831-95), John Trafford Clegg (1857-95).

3. "Come whoam

to thi childer an' me" conveys an impression of Waugh, the man,

that was not borne out in reality. In his diaries,

Samuel Bamford, after sending his wife

to warn a prospective landlady of Waugh's charcater, speaks thus (29

August 1861): ". . . . My wife had, I learned put her on her guard with

respect to his character; told her about his wife and three children being

on the parish at Rochdale [i.e. in the workhouse]; about his having

been living with a woman in Stangeways, who was supposed to have kept him,

or nearly so, and about his general habits of profligacy and faithlessness

in his arrangements. . . . " |

<>

|