|

[Previous Page]

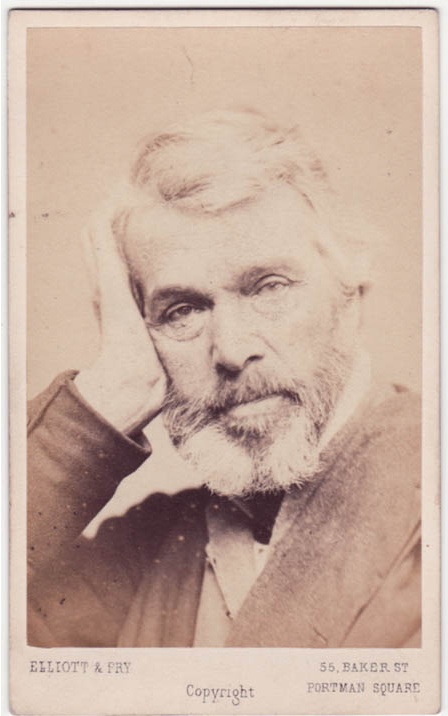

LORD JOHN RUSSELL.

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, KG, GCMG, PC

(1792-1878):

English Liberal politician and twice Prime Minister.

SYDNEY

SMITH, in his amusing

and clever letter to Archdeacon Singleton, thus describes Lord John

Russell:—"There is not a better man in England than Lord John

Russell; but his worst failure is, that he is utterly ignorant of

all moral fear; there is nothing he would not undertake. I

believe he would perform the operation for the stone, build St.

Peter's, or assume (with or without ten minutes' notice) the command

of the Channel fleet; and no one would discover by his manner that

the patient had died, the church tumbled down, and the Channel fleet

been knocked to atoms. I believe his motives are always pure,

and his measures often able; but they are endless, and never done

with that pedetentous pace and that pedetentous mind in which it

behooves the wise and virtuous improver to walk. He alarms the

wise Liberals; and it is impossible to sleep soundly while he has

the command of the watch."

This, though a smart sketch, is by no means correct; indeed,

it is as nearly as possible the reverse of correct. What

Sydney Smith averred Lord John Russell to be, that assuredly he is

not. No man is less rash than he; no man is slower to initiate

measures. By nature and temperament, he is eminently

conservative. Sir Robert Peel, who was proverbially cautious,

was bolder than he; witness his thoroughgoing measure on the Corn

Laws. Gladstone, also a careful, slow man, has shot far ahead

of Russell in matters of finance. Had Lord John Russell not

been a man of great tact, discretion, and caution, he never could

have secured the confidence of his large body of followers.

And when he has lost adherents, and excited suspicions amongst those

who sit upon his own side of the House, it has almost invariably

been through his holding back,—his disposition to stand still and

even to recede,—certainly never through his enterprise or boldness.

Lord John Russell is an eminently respectable politician.

His high family connections give him influence, and his pure

personal character commands respect. He is a man of carefully

cultivated powers, of sound judgment, of large experience, and of

undoubted patriotism. He is beloved, as well as admired.

But he is not a man of genius; he is neither brilliant nor original;

his qualities are of a more solid, practical, and useful kind.

He has excellent tact, his style of speaking is exactly suited to

the House of Commons, and, though he is not eloquent, no man makes

more appropriate and telling speeches, or is more attentively

listened to. He is not an orator, yet he succeeds better than

many orators do, for he labours to convince. And he does this

in spite of his deficiency in those graces which are so greatly

admired in other speakers. His physique is against him.

He is a little, quiet, modest, almost insignificant-looking

personage. His features are sharp, and his frame fragile.

When he is first pointed out, you wonder that such a man can be a

leader of the House of Commons, and of the many great, bulky men you

find there. But, as Ben Jonson says,

|

"It is not growing, like a tree,

In bulk, doth make man better be." |

And when Lord John Russell speaks, you soon find that in him,

as in all of us, "the mind's the measure of the man." His

manner, at first, is rather hesitating, and his voice is feeble in

tone and quality. It is somewhat monotonous, and seemingly

incapable of that fine modulation which is admired so much in the

orations of Disraeli. There is an aristocratic twang and

thorough House of Commons tone about it. As he warms, he

becomes freer and easier, but he rarely rises into enthusiasm.

When he has said a good thing, which he does in the most polished

manner, he turns round, as if to receive the cheers of his

supporters, which are always ready; and his statesmanlike views,

expounded in felicitous diction, rarely fail to command the

admiration of both sides of the House. He is always

self-possessed, and on emergencies he is never found wanting in

skill and energy. It is these qualities, and his long

experience of Parliamentary tactics, which have given Lord John his

present eminent position in the British legislature.

He entered the House of Commons when a very young man.

He was born in 1792,—the third son of the late Duke of Bedford,—and

he was returned to Parliament in 1813, as member for Tavistock, one

of the family boroughs. He thus commenced his Parliamentary

career at twenty-one years of age, and has continued a member of the

House of Commons almost without interval since then,—that is, for a

period of nearly fifty years. His maiden speech was made on

the Alien Bill, in the year 1814. The speech which he then

delivered very much resembled one of his speeches now; it was terse,

pointed, argumentative, and enlivened by playful satire and wit.

In that speech he alluded to the question of Parliamentary Reform,

to which he afterwards devoted himself so thoroughly, and made the

question almost his own in the House of Commons. It would be

beside our purpose to quote the early sentiments of Lord John on

this topic, but it appears to us that not only was his mind,

character, and style of oratory formed at that early period of his

career, but that he has added little to these except what careful

culture and the maturing influence of years and experience have

necessarily effected. In this respect he strikingly differs

from Peel, Disraeli, and many of his famous contemporaries.

From 1814 to 1831 he revived from time to time the discussion

of Whig Reform, as opposed to Radical Parliamentary Reform. To

the latter he was always opposed; and he withstood Burdett,

O'Connell, and Hunt as emphatically as Sir Harry Inglis himself

could do. His plans were invariably moderate, and on one

occasion, at the request of Lord Castlereagh, he withdrew his

resolutions for the disfranchisement of certain corrupt boroughs, on

the understanding that Grampound only was to be disfranchised, which

was done. But two years later, in 1821, he renewed his

efforts, proposing to extend the measure of disfranchisement of

rotten boroughs, and transfer the seats to large towns then

unrepresented. The question was taken up out of doors,

agitation increased from year to year, until March, 1831, when Lord

John proposed the first Reform Bill in the House of Commons.

The measure was thought to be very revolutionary at the time; but

experience has shown that it was rather conservative than otherwise.

Still it was a great and important constitutional change, to which

Lord John Russell's exertions were greatly instrumental. Since

then he has been prominently before the public as a practical

statesman, as a Liberal leader in the House of Commons, and

occasionally as Prime Minister of Britain. He has represented

during his career the moderate liberalism of his age, and his

exertions have been devoted quite as much to restraining the too

eager amongst his own followers, as to urging on the lagging spirit

of his opponents. One thing is clear and admitted, that Lord

John Russell is a thoroughly honest politician, animated by a pure

sense of duty, and that, while many others of our public men have

proved faithless, he has adhered pretty constantly to his early

moderate Whig principles and opinions.

We turn now to Lord John Russell's career as an author, for

he, like many other members of the present administration, has been

a writer of books. His success as a writer has, however, been

but moderate, and we question whether the copyright of his works

would be regarded by any bookseller as a desirable investment.

That he has sought to achieve reputation as a writer of books is,

however, creditable to him as a man; and it indicates a literary

taste which is honourable even to a lord. He has written a

novel, —"The Nun of Aronea;" a play, "Don Carlos;" a

biography,—"Lord William Russell; a history,—"Memoirs of the Affairs

of Europe;" and he has written several essays and tracts on

political subjects. His last works are his "Memoirs and

Letters of Fox," and his "Memoirs and Letters of Moore,"—both of

which might have been better done.

To speak the truth, his Lordship does not shine as an author.

We have inquired for "The Nun of Aronea " at the circulating

library, but the librarian's answer was, "Never heard of such a

book." The Nun may therefore be regarded as a mere curiosity

of literature, interesting only as a Prime Minister's first literary

enterprise. Several of the leading Whig ministers made their

literary début in the same line. The Marquis of

Normanby's novel, entitled "No," is, we suppose, still inquired

after, though it is a somewhat sickly affair. The Duke of

Argyle and Sir William Molesworth are also authors, but of a more

solid, philosophical kind. It is not improbable that Lord

Byron—with whom Lord John Russell was intimate in his early years,

travelling with him in Portugal in 1809—had some influence in

directing Lord John Russell's attention to imaginative literature.

His journey in Spain seems to have suggested to him the subject of

the drama commenced by him about the same time, though not published

for many years after, on the subject of "Don Carlos." This

play has been a good deal ridiculed by his Lordship's literary

opponents, yet it is a favourable specimen of his literary powers,

even though bearing it be not equal to Schiller's tragedy bearing

the same title. The Westminster Review has

characterized the speeches in the play, which are intended to be

dignified, as "grand nonsense, which, of all things, is the most

unsupportable;" and added, that "there is not a vestige of poetical

feeling, nor a single passage that rises above commonplace, not a

character or creation in the whole dramatis personæ; they are

mere automata; a more undignified, pitiful puppet than Philip could

not be walked through five acts of any play; nor a more puling,

characterless personage than Don Carlos, whose mawkish

sentimentality would overpower even a boarding-school miss of the

last generation." This, however, is too severe. For

example, the following passage is well written, and it will be read

with interest now, as indicating, under the guise of a fictitious

character, the source of the writer's own after-success in the

political drama in which he has played so prominent a part:

|

Valdez.

It was my aim.

And I obtained it not for empty glory,

For as I rooted out the weeds of passion,

One still remained, and grew till its tall plant

Struck root in every fibre of my heart:

It was ambition,—not the mean desire

Of rank or title, but great, glorious sway

O'er multitudes of minds.

Lucero. That you have gained.

Valdez. I have indeed, and why?

I'll tell thee why.

. . . .

. . My appetites

Were in one potent essence concentrate,

I neither loved, nor feasted, nor played dice;

Power was my feast, my mistress, and my game.

Thus I have acted with a will entire,

And wreathed the passion that distracted others

Into a sceptre for myself. |

Another of Lord John's early essays, if not his first, was a

book entitled "Essays and Sketches of Life and Character, by a

Gentleman who has left his Lodgings." The pseudonyms assumed

by his Lordship on this occasion was "Joseph Skillet," who ushered

the essays into notice with a rather humorous preface, explaining

how the MSS. came into his possession, and why he determined

to print them. This was a fashion in vogue at the time, and

probably the author of Waverley helped it by the very amusing

prefaces which he usually prefixed to his novels. Joseph

Skillet's essays were not, however, very brilliant, though somewhat

dogmatic. They indicated considerable reading, and a

cultivated literary taste. There is some smartness about the

essays, but we search them in vain for one original thought.

Take, for instance, a passage on "Men of Letters:"—

"There is no class of persons, it

may be observed, whose feelings are more open to remark than men of

letters. In the first place, they are raised on an eminence,

where everything they do is carefully observed by those who have not

been able to get so high. In the next place, their occupation,

especially if they are poets, being either the expression of

superabundant feeling or the pursuit of praise, they are naturally

more sensitive and quick in their emotions than any other class of

men: hence a thousand little quarrels and passing irritabilities.

In the next place, they have the power of wounding deeply those of

whom they are envious. A man who shoots envies another who

shoots better. A shoemaker even envies another who makes more

popular shoes; but the sportsman and the shoemaker can only say they

do not like their rivals; the author cuts his brother author to the

bone with the sharp edge of an epigram or bon mot."

But Lord John's reputation as a literary man rather rests on

his political works than on any of those above mentioned. In

1820 he published a Life of his distinguished ancestor, Lord William

Russell. This is a good, readable biography, though we are

disposed to suspect biographies written by descendants of

distinguished men. They can scarcely be called impartial, as

they are concerned to spare the deceased in matters about which the

public are interested in knowing the whole truth. The "Life of

Lord William Russell" is rather too much of a collection, in the

style of Moore's Life and Letters. In the art of biography,

Lord John certainly is not great. Speaking of the opinion of

his relative, the author states: "The political opinions of Lord

Russell were those of a Whig. His religious creed was that of

a mild and talented Christian." But he adds, speaking

of his animosity to the Catholics: "It must be owned that the

violence of Lord Russell against the Roman Catholics betrayed him

into credulity." Thus, the mild and talented Christian,

according to the author, was a man of violent animosity and a

credulous zealot.

Lord John, when recently speaking at Bristol, on the subject

of English History, was very hard upon Hume and others, who fell

infinitely short of his own high standard. But it is clear

that the history of England, written in the above style, would be

neither accurate nor instructive.

In 1821 another work appeared from Lord John Russell's pen,

entitled "An Essay on the History of the English Government and

Constitution, from the Reign of Henry the Seventh to the present

Time." This work is fragmentary, being only the latter half of

the treatise originally proposed by his Lordship, which was to

embrace an examination of the history of constitutional monarchies.

The Essay contains a summary of the then political opinions of his

Lordship on poor laws, national debt, liberty of the press,

Parliamentary reform, public schools, and such like subjects.

The conclusion of the treatise contains the pith of it, as

postscripts often do, and it is as follows: "There was a practical

wisdom in our ancestors, which induced them to alter and vary the

form of our institutions as they went on, to suit the circumstances

of the time, and reform them according to the dictates of

experience. They never ceased to work upon one frame of

government, as a sculptor fashions the model of a favourite statue.

It is an act now seldom used, and the disuse has been attended with

evils of the most alarming magnitude." Cobbett would have

found a rich subject for his sarcasm in this sentence, had he

analyzed it in his usual scarifying style,—for it is anything but

well written,—yet you see through the author's meaning clearly

enough; the Westminster Review thus briefly criticised it:

"The sentence exhibits the tinkering propensities of Lord John to

mend the constitutional kettle." In former days, his Lordship

was a zealous supporter of the Corn Laws, which he looked upon as

"preventing the abandonment of agriculture in England;" and he very

highly approved Lord Lauderdale's scheme of coining guineas of the

value of twenty-one shillings paper currency, as a measure necessary

for "the safety of the State" and the satisfaction of the claims of

the national creditor.

One of the best-written sentences in the last-mentioned Essay

is that in which his Lordship describes the character of the

political lawyer,—a description, however, by no means complimentary

to the Bar:

"Generally speaking, the first disposition of a lawyer, it

must be confessed, is to inquire boldly and argue sharply upon

public abuses. They are not apt to indulge any bigoted

reverence for the depositaries of power; and, on the other hand,

they value liberty as the guardian of free speech. But the

close of a lawyer's life is not always conformable to his outset.

Many who commence by too warm an admiration for popular privileges,

end by too frigid a contempt for all enthusiasm. They are

accustomed to let their tongues for the hour, and by a natural

transition they sell them for a term of years, or for life.

Commencing with the vanity of popular harangues, they end by the

meanest calculations of avarice." This is certainly sense, but

happily not quite correct. There are lawyers who have ratted;

but even ministers are not infallible; and there are men of all

political parties the close of whose lives is not always conformable

to their outset,—for which, indeed, they are as often entitled to

our praise as to our blame.

The largest work which Lord John has published, and that on

which he has bestowed most pains, is his "Memoirs of Europe from the

Peace of Utrecht," published in two quarto volumes, in 1824; and it

has since reached a fourth edition. This bespeaks the public

approval. But the book is dull, and lends no fresh interest to

the history of the period. It is a dry compilation, an

annotated chapter of historical events; but it is not history,

unless it be the dropsy of history. Beside Macaulay, Alison,

and Martineau, his Lordship indeed looks small. But he

continued to write other historical works; the principal of which

are, "The Establishment of the Turks in Europe; an Historical Essay,

with Preface," published in 1828, in which the author regarded with

rather a favourable eye the doctrines of Mahomet, but failed to give

any clear idea of the history or government of Turkey in Europe.

Another historical essay followed, in 1832, on "The Causes of the

French Revolution," a gossiping book about Voltaire, Rousseau, and

the court of Louis; but its title is evidently a misnomer.

Indeed, his Lordship was now so immersed in the political life of

the House of Commons, that works of an elaborate or carefully

studied character were scarcely to be expected from his pen.

Nevertheless, he has since appeared as an author, or rather as an

editor,—in 1842, as the editor of the "Correspondence of John,

Fourth Duke of Bedford," and more recently as the editor of Tom

Moore's and Charles James Fox's "Life and Correspondence." The

subjects are in themselves of great interest, and deserve able and

careful treatment. Whether they have received that, let the

critics and the public be the judges. It is clear, however,

that Lord John Russell's reputation with posterity will not depend

upon his literary works. His true arena is the House of

Commons,—the theatre of his greatest intellectual efforts and his

most decided triumphs.

――――♦――――

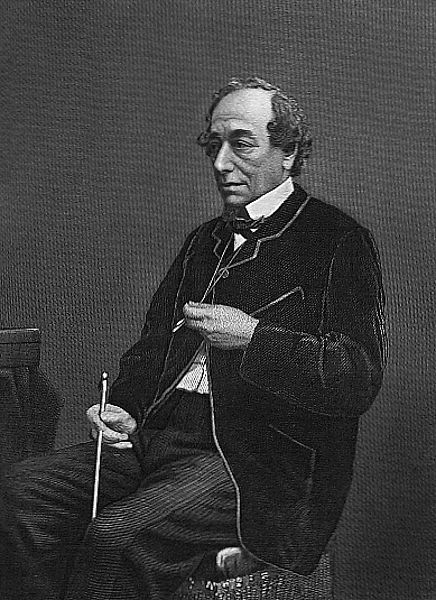

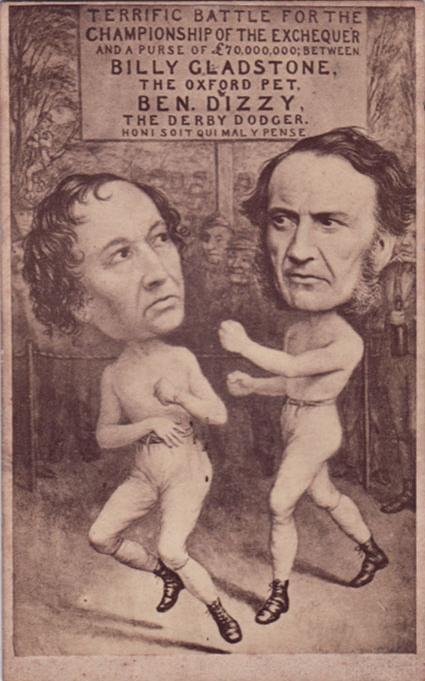

THE RT. HON. BENJAMIN DISRAELI.

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC,

FRS (1804-81):

English statesman and twice Prime Minister.

Picture Wikipedia.

THE distinguished

Conservative leader of the House of Commons is entitled to be

regarded as a literary, quite as much as a political character.

He had achieved a reputation as an author long before his advent as

a debater; and, not improbably, it was his careful training in the

former capacity which laid the foundations of his success in the

latter.

This British statesman is of Jewish descent. His

grandfather, Benjamin Disraeli, was a Venetian merchant, settled for

many years in England. He left a moderate fortune to his son,

Isaac Disraeli, the well-known author of the "Curiosities of

Literature," and other works. Mr. Isaac Disraeli lived at the

old house, No. 6 Bloomsbury Square, where Benjamin, the future

Chancellor of the Exchequer, was born, in December, 1805.

The son took after the father's tastes, and very early made

his début in literature. After a careful course of

school instruction, and an ineffectual attempt on the part of his

father to make a city merchant of him, the youth made a tour in

Germany, in his eighteenth year, and on his return to England he set

about the composition of his first work, which was published while

he was yet a minor, in the beginning of 1826. The book was a

novel, in five volumes,—the well-known "Vivian Grey." Its

appearance caused considerable excitement in the literary world; it

quite puzzled the busy idlers of high life by its pictures of

fashionable society, which, however faithful they may have been,

were calculated to give the general reader a thorough contempt for

that blasé region of humanity. But those caterers for

the press, who assumed to represent the aristocratic portion of

society, pronounced the pictures drawn in "Vivian Grey" to be

impudently false and outrageously absurd. However this may be,

the book was eagerly read, and was the "talk of the season."

It exhibited almost reckless power, was full of daring sarcasm, and,

though often false and absurd, was yet, throughout, (we speak more

especially of the first two volumes, which are complete in

themselves,) original and coherent.

It is curious, at this time of day, to read "Vivian Grey" by

the light thrown upon its pages by the more recent career of its

author. Thus regarded, it is something of a prophetic

book. It contained the germs of nearly all the subsequent

fruit of Mr. Disraeli's mind,—to the extent of his political

aspirations, his struggles, and his successes. They are all

foreshadowed there. Although, in the third volume (published a

year after the first two), he disclaimed the charge of having

attempted to paint his own portrait in the book, it is nevertheless

very clear that, in imagination, he was the hero of his own tale,

and that the characters or puppets which he exhibited and worked

were such as he would have formed had he the making of the world;

nay, more, they were such as he subsequently found ready-made to his

hand.

In "Vivian Grey" you have the fast young man in upper-class

life,—a brilliant, fashionable, clever, sardonic, heartless,

ambitious youth,—possessed by an ardent craving for political

intrigue, and a keen desire for fame and power, to achieve which he

has no scruples about the means, employing tricks, falsities, and

grand coups de théâtre, provided these will serve his

purpose. The motto standing on the title-page bespeaks the

character of Vivian Grey:

|

"Why then the world's mine oyster,

Which I with sword will open." |

One of the prominent characters in the book is the Marquis de

Carabas,—an aristocratic booby,—one of those ciphers with a figure

before it, in the shape of a title, which give ciphers so much value

in modern society. This Marquis de Carabas had been in

power,—and he might be again. So Vivian clings to his skirts,

makes a friend of him, intrigues for him, and hopes by his aid to

vault into power and office, though despising, all the while, the

Marquis's heart, intellect, and character. Vivian first gains

his Lordship's favour at a dinner-party, by helping him out in an

argument by a quotation from Bolingbroke (invented by Vivian for the

occasion), and he afterwards secures the noble lord by furnishing

him with a receipt for making "Tomahawk Punch." From a

dissertation on punch, Vivian diverges into a conversation about

Power, and of course he succeeds, in his usual all-powerful way, in

rousing the old lord's slumbering ambition. Here is a curious

passage:

"'Is power a thing so easily to be

despised, young man?' asked the Marquis.

"'O, no, my lord, you do mistake me,' eagerly burst forth

Vivian; 'I am no cold-blooded philosopher, that would despise

that, for which, in my opinion, men—real men—should alone

exist. Power! O, what sleepless nights! what days of hot

anxiety! what exertions of mind and body! what travel! what hatred!

what fierce encounters! what dangers of all possible kinds, would I

not endure, with a joyous spirit, to gain it!' . . . .

"It must not be supposed that Vivian was, to all the world,

the fascinating creature that he was to the Marquis of Carabas.

Many complained that he was reserved, silent, haughty. But the

truth was, Vivian Grey often asked himself, 'Who is to be my enemy

to-morrow?' He was too cunning a master of the human mind not

to be aware of the quicksands upon which all greenhorns strike; he

knew too well the danger of unnecessary intimacy. A

SMILE FOR A FRIEND, AND A SNEER FOR THE WORLD,

is the way to govern mankind, and such was the motto of Vivian Grey.

"Now, Vivian Grey was conscious that there was at least one

person in the world who was no craven, either in body or mind; and

so he had long come to the comfortable conclusion that it was

impossible that his career could be anything but the most brilliant

. . . . . Not that it must be supposed, even for a moment, that

Vivian Grey was what the world calls conceited. O, no!

he knew the measure of his own mind, and had fathomed the depth of

his powers with equal skill and impartiality; but in the process he

could not but feel that he could conceive much, and

dare do more."

Vivian climbs well. He forms a party, and seems on the

eve of vaulting with them into power. At this time his father

(a retired literary gentleman) writes to him as follows. It is

Vivian Grey's other self that speaks; and perhaps Benjamin Disraeli

himself may yet look back with interest at this prophetic utterance

of his youth:—

"'You are now, my dear son, a member of what is

called le grand monde,—society formed on anti-social

principles. Apparently, you have possessed yourself of the

object of your wishes; but the scenes you live in are very movable;

the characters you associate with are all masked; and it will

always be doubtful whether you can retain that long which has been

obtained by some slippery artifice. Vivian, you are a

juggler; and the deception of your sleight-of-hand tricks

depends upon instantaneous motion. When the selfish combine

with the selfish, bethink you how many projects are doomed to

disappointment; how many cross interests baffle the parties, at the

same time joined together without ever uniting. What a mockery

is their love! but how deadly are their hatreds! All this

great society, with whom so young an adventurer has trafficked,

abate nothing of their price in the slavery of their service and the

sacrifice of violated feelings. What sleepless nights has it

cost you to win over the disobliged, to conciliate the discontented,

to cajole the contumacious! You may smile at the hollow

flatteries, answering to flatteries as hollow, which, like bubbles

when they touch, dissolve into nothing; but tell me, Vivian, what

has the self-tormentor felt at the laughing treacheries which force

a man down into self-contempt?'"

An old political character, Cleveland, thus discourses to

Vivian:—

"'O Grey! of all the delusions

which flourish in this mad world, the delusion of that man is the

most frantic who voluntarily, and of his own accord, supports the

interest of a party. I mention this to you because it is a

rock on which all young politicians strike. Fortunately, you

enter life under different circumstances from those which usually

attend most political débutants. You have your

connections formed and your views ascertained. But if, by any

chance, you find yourself independent and unconnected, never, for a

moment, suppose that you can accomplish your objects by coming

forward, unsolicited, to fight the battle of a party. They

will cheer your successful exertions, and then smile at your

youthful zeal; or, crowing themselves for the unexpected succour, be

too cowardly to reward their unexpected champion. No, Grey,

make them fear you, and they will kiss your feet.'"

It will be seen, from these extracts, that the book is

intensely political in its character, and is not without its close

bearings upon the career of the author himself. Its sketches

of character were found so clever, its satire so keen and

relentless, its dialogue so brisk and effervescent, that "Vivian

Grey" became the rage of the day, and there was a decided run upon

it at all the circulating libraries. Not improbably its great

success dazzled the author. Finding himself suddenly raised to

a giddy eminence, he struggled convulsively to retain it; and in his

next novel, entitled "Contarini Fleming, or, The Physiological

Romance," the faults of "Vivian Grey" came out again in a still more

exaggerated form. There was the same flashiness and force, the

same dashing satire and exaggerated character, the same strong

self-portraiture, the same desire to astonish people, and take them,

as it were, by storm. And yet, withal, the book was full of

brilliant writing and captivating imagery; and though the taste

which dictated it was often false, the thoughts were generally

striking and the language chaste, elegant, and classical.

In the meantime, the author had made an extensive tour

through foreign countries, visiting Italy, Greece, and Albania;

passing from thence, in the winter of 1829-30, to Constantinople.

In the following spring he visited the land of his fathers, and

traversed the scenes made memorable by the deeds and history of the

children of Israel,—a portion of his tour which seems to have

exercised great influence on his ardent imagination. From

Syria, he travelled on to Egypt and Nubia, and returned to England

in 1831, where he found the nation in the throes of the Reform

agitation. He could not fail to be influenced by the stirring

events passing around him at this time; but, still under the deep

shadow of Eastern tradition and romance, he now gave birth to his

"Wondrous Tale of Alroy,"—which the critics universally hailed as a

damning proof of the young author's confirmed literary lunacy.

The book was beautifully written, yet it was an exhibition of

romance run mad, which no elegances of style could redeem.

Wild, incongruous, and raving, it was laughed at unmercifully,—and

for a writer to be laughed at in England, when he means to be

serious! every one knows what the fate of that writer is. But

Disraeli had pluck in him, and he recovered himself in time, though

not before he had perpetrated several other literary absurdities of

an extraordinary kind. One of these was his "Revolutionary

Epic," in commemoration of the great revolutionists of modern times,

from Robespierre down to John Frost. Only the first part of

this poem was given to the world; but the author promised future

instalments, should the plaudits of the public encourage him to

proceed. In his Preface, however, he added, "That if the

decision of the public should be in the negative, then will he,

without a pang, hurl his lyre to Limbo." As the public laughed

at the poem, nothing more has been heard of the sequel of the

"Revolutionary Epic."

After the lapse of a few years, Mr. Disraeli again appeared

before the public in a succession of novels. Abandoning the

ultra-romantic style he had adopted in the "Wondrous Tale of Alroy,"

and the ultra-sardonic manner of "Vivian Grey," he consented to

enter upon a more beaten track, in which, by dint of perseverance

and hard work, he was soon enabled to get ahead of most of his

contemporaries. "Henrietta Temple," "Venetia," and "The Young

Duke," were rather sickening in their love passages, but the stories

were well told. "Violette the Danseuse" (which has been

generally attributed to him) was a charming tale, though there was

about it rather too much of the "man about town." His later

tales are well known; they are certainly his best;—"Coningsby,"

published in 1844 "Sybil," in 1845; and "Tancred," in 1847.

"Coningsby" and "Sybil" are of a strongly political

character; they might almost be regarded as a kind of official state

papers, embodying the theories of Young England as to politics,

society, and history. "Coningsby" was hailed, on its

appearance, as an exceedingly clever novel,—clever in the higher

acceptation of the term. It exhibited moral courage, mental

independence, and worthy aims. It showed, on the writer's

part, a strong desire to make Conservatism popular: and even while

scouting democracy, he made his court to it. "Coningsby" is

eminently a novel of progress; it might almost be termed democratic.

The pictures of the aristocracy and their toadies, given there, do

not make us fall in love with them,—most probably they were not

intended to do so. In delineating the corruption of the rotten

boroughs, though Disraeli may not equal Thackeray or Dickens, he yet

furnishes us with capital pictures, broadly painted, and full of

truthful vigour. His Rigby, Monmouth, Taper, and Tadpole, will

not soon be forgotten.

But it is difficult to ascertain from these

novels, or even from Mr. Disraeli's speeches, what his precise

principles are. One thing he is very enthusiastic about, and

that is, the Judaic element in civilization, and he from time to

time cries up "the pure Caucasian breed," and "the Venetian origin

of the British Constitution." But his notions about the said

British Constitution are very peculiar. He decries the

representative part of it, which many take to be its vital element.

He sets the press and public opinion above the Parliament.

"Opinion," says he, "is now supreme, and speaks in print. The

representation of the press is far more complete than the

representation of Parliament. Parliamentary representation was

the happy device of a ruder age, to which it was admirably adapted;

an age of semi-civilization, when there was a leading class in the

community; but it exhibits many symptoms of desuetude. It is

now controlled by a system of representation more vigorous and

comprehensive." And then he goes on to say that, "If we are

forced to revolutions, let us propose to our consideration the idea

of a free monarchy, established on fundamental laws, itself the apex

of a vast pile of municipal and local government, ruling an educated

people, represented by a free and intellectual press;" in fact, a

kind of parental despotism, or combination of absolutism and

democracy, such as is now being tried on the other side of the

English Channel. All this may seem rather destructive in its

tendencies. Indeed, Mr. Disraeli's forte is not

constructiveness: he is good at pulling down; but any hodman can do

this. The great practical genius must show how he can build.

If we were called upon, after a perusal of Mr. Disraeli's writings

and speeches, to give a definition of his politics, we should

say,—his sentiments are Tory, his presentiments are Radical; he

feels like a Paladin, he thinks like a Republican. As for his

proper political party, though he may at present be the leader of

a party, his own is really to make yet. He has but few

sympathies with the men whom he leads, and they have few or none

with him. The Buckingham county aristocracy turn up their

noses at him; but let these and other county magnates beware how

they spit upon the Jewish gabardine. He may plant his foot

upon their necks yet. He has himself publicly stated in the

House of Commons, that he had little sympathy for either of the

great political parties into which the public men of England have

heretofore been divided; and in "Coningsby," while he avers that

"the Whigs are worn out," and Radicalism is polluting," he also

emphatically declares that "Conservatism is a sham."

Indeed, Mr. Disraeli is a thorough sceptic as regards all

that we denominate social progress. He scouts it as a

delusion, and represents it as a hoax. This is made very clear

in his most careful novel, "Tancred." As the Edinburgh

Review observed, in noticing the work on its appearance:

"All that we are accustomed most to admire and

desiderate, all that we are wont to rest upon as most stable amid

the fluctuating fortunes of the world,—the progress of civilization,

the development of human intelligence, the co-ordinate extension of

power and responsibility among the masses of mankind, the advance of

self-reliance and self-control, all, in truth, for which not we

alone, but all other nations, have been yearning, and fighting, and

praying for the last three centuries,—all that has been done by the

Reformation, by the English and French Revolutions, by American

Independence,—is here proclaimed an entire delusion and failure; and

we are taught that we can now only hope to improve our future by

utterly renouncing our past."

"Tancred " falls back upon an old idea of Mr. Disraeli's,—the

supremacy of the Jewish race, and their alleged prerogative of being

at once the moral ruler and political master of humanity.

Indeed, we are strongly impressed with the idea that this

distinguished man's life and opinions have been in no small degree

influenced by the fact of his own peculiar origin and ancestry.

We say this in no offensive or hostile spirit. But a man

cannot ignore his own blood; and of all races of men, the "peculiar

people" cling the most tenaciously to their traditions, kindred, and

ancestry. A Jew never becomes thoroughly influenced by the

national spirit of the people among whom he lives; he is a Jew

still; his home and country are in the East,—still in the promised

land. What is more, he cannot sympathize fully with the ideas

of progress and civilization entertained by other races. He is

neither inspired by the military and adventurous spirit of the Celt,

nor the colonizing, laborious enterprise of the Saxon. He does

not cling to the soil until it becomes native to him. Though

centuries pass away, the Jewish family, like the Gypsy, remains the

same. It never merges nor subsides, like the Saxon, Danish, or

Norman, into the nation amid which it has planted itself.

This essential characteristic of the Jew will be found to

form the true key to "Coningsby," "Sybil," and especially to

"Tancred" and also to those peculiarly "destructive" and altogether

indefinite political views entertained (so far as can be collected

from his speeches and writings) by the distinguished subject of our

present memoir. In "Tancred," the old Judaic notions as to the

race will be found revived in their most intense form. He

there represents "the slumber of the East as more vital than the

waking life of the rest of the globe;" and Europe is described as

"that quarter of the globe to which God has never spoken." "'I

know well,' says Tancred, in Palestine, 'though born in a northern

or distant isle, that the Creator of the world speaks with men only

in this land; and that is why I am here.'" "Is it to be

believed," writes Mr. Disraeli, speaking in his own proper person,

"that there are no peculiar and eternal qualities in a land thus

visited, which distinguish it from all others? that Palestine is

like Normandy or Yorkshire, or even Athens or Rome?" Strange,

that the country gentlemen of England should have adopted this

Fetichist for their leader!

We have left ourselves but small space to refer to the

political career of Mr. Disraeli; but it is not necessary we should

refer to this at any length. In "Vivian Grey" his political

views seemed bounded by a desire to find a Marquis de Carabas.

The feverish excitement of the Reform Bill, which stimulated him to

become the poet of the epoch, brought him out in the character of a

Radical, or rather a hater of the Whigs; because, after all, he

never seems to have clung very closely to Radicalism. However,

he went down to High Wycombe as a candidate for that borough, in

1832, recommended by Mr. Hume and Sir E. L. Bulwer. Mr.

O'Connell was, at the same time, applied to for a character.

Mr. Disraeli was defeated; a second election took place in the same

year, when he was again defeated; and he tried the borough a third

time, in 1835, when he was a third time defeated. It seems

that the late Earl Grey, on hearing of Disraeli having contested the

Wycombe election with his relative, Colonel Grey, asked of some one

the question, "Who is he?" and immediately the young aspirant for

Parliamentary honours issued a furious pamphlet under this title.

It was originally published by Hatchard of Piccadilly, but is not

now to be had. It was a furious onslaught on the Whigs, very

eloquent, but in many places very unintelligible.

A vacancy in the representation of Marylebone shortly after

occurred, on which Disraeli announced himself as a candidate,

published placards, and canvassed the constituency; but he did not

go to the poll. Joseph Hume, on whom he called, gave him "the

cold shoulder;" for the old veteran could not see very clearly

through the young politician's hodgepodge notions of Anti-Whig

Liberalism, Tory Radicalism, and Absolutist Democracy, which he had

just developed in an address to the electors of High Wycombe, under

the title of "The Crisis Examined." So, abandoning the hope of

getting into Parliament on Joseph Hume's or Daniel O'Connell's

shoulders, the Young-Englander suddenly wheeled round on the other

tack, and forthwith came out in the character of a full-blown Tory.

He went down to Taunton to oppose Mr. Labouchere, and was defeated.

A furious altercation between him and O'Connell afterwards took

place, in which the latter denounced him, in his usual coarse,

Swift-like style, as one who, "if his genealogy were traced, would

be found to be the true heir-at-law of the impenitent thief who died

upon the cross." On this, Disraeli, stung to fury, challenged

Morgan O'Connell to fight him in a duel; but Morgan declined;

Disraeli was bound over to keep the peace, and the correspondence

was published. In his letter to O'Connell he concluded with

these words: "We shall meet at Philippi, where I will seize

the first opportunity of inflicting castigation for the insults you

have lavished upon me." The correspondence was a good deal

laughed at, and Disraeli had by this time certainly succeeded in

reducing himself to the lowest possible plight as a public man.

But he had genius in him, and resolution; and he worked his way

upward again, as we shall see.

He began to recover himself through means of the

press,—always his great power. He wrote a very clever,

brilliant, and admirable essay, entitled, "A Vindication of the

English Constitution;" and shortly after, he published in the

Times newspaper a series of very clever letters, afterwards

collected in a volume, entitled the "Letters of Runnymede."

They were racy, brilliant, satirical, and well-informed, though

occasionally rather insolent in their smartness. It is also

supposed that, about the same time, and even down to a recent date,

Mr. Disraeli contributed frequently to the leading columns of "The

Thunderer."

At length, Mr. Disraeli succeeded in obtaining admission to

Parliament, as one of the members for the borough of Maidstone.

This was at the general election in 1837. No great

expectations were formed of him, and yet there was some curiosity

excited respecting his début as an orator. He had

delivered some blazing philippics against the Whigs out of doors,

and uttered sundry mystic speeches, rather overlaid with classical

allusions. The gentlemen of the House of Commons expected that

Disraeli would make a fool of himself; and he did not disappoint

them. His first effort was a ludicrous failure,—his maiden

speech being received with "loud bursts of laughter." The

newspapers said of him, that he went up like a rocket, and came down

like its stick. You may conceive the chagrin of the young

legislator,—whose speech had been composed in the grandest and most

ambitious strain of eloquence, but was received as if every period

concluded a pun or a flash of wit. It was as if Hamlet had

been played as a comedy! But towards the conclusion, he threw

in a sentence worthy of being quoted, for it was a true prophecy.

Writhing under the shouts of laughter which had drowned so much of

his studied eloquence, he exclaimed in an almost savage voice: "I

have begun several times many things, and have often succeeded at

last. I shall sit down now, but the time will come when

YOU WILL HEAR ME!" The time did

come,—for Disraeli now stands confessed to be one of the greatest

orators within the walls of the British Parliament.

The subsequent career of Disraeli furnishes an admirable

lesson to all men: it shows what determination and energy will do.

He owed all his success to hard work and patient industry. He

began carefully to unlearn his faults, to study the character of his

audience, to cultivate the arts of speech, and to fill his mind with

the elements of Parliamentary knowledge. He soon felt that

success in oratory was not to be obtained at a bound, but had to be

patiently worked for. His triumph did come; but it came

slowly, and by degrees. A year and a half elapsed before he

again attempted to address the House; and then the results of his

care and study showed themselves in an excellent speech on the

presentation of the Chartist Petition. He had already thrown

away his poetic and historical imagery, and took his stand on facts,

feelings, and strong common-sense. In the following year, he

delivered a speech full of strong sympathy for the incarcerated

Chartists, Lovett and

Collins, disclaiming the plea of mercy on the part of the state

in their behalf, and insisting that they were the really aggrieved

parties. His speeches on copyright and education in the

following year were much admired, and also his famous attack on

foreign consular establishments in the session of 1842. These

speeches served to efface the recollection of his first egregious

failure, though he had not yet achieved a very high position in the

House.

In 1844 Mr. Disraeli commenced his series of oratorical

attacks on Sir Robert Peel, and continued them with invincible

pertinacity, and with growing power and force of satire, until the

fall of that lamented statesman, and even for some time after.

It is said that Disraeli had been slighted in his aspirations for

office,—at all events, he had been overlooked; for Sir Robert Peel

always preferred to have under him men of strongly practical

qualities. How that may be, we cannot tell; but certainly, the

vehement personal attacks,—the stinging, biting satire launched

through the teeth,—the almost vengeful wrath with which Disraeli

pursued the minister, and met him with his poisoned shafts at every

turn,—exhibited a determined personal hostility, which must have had

its foundation in some slighted ambition or exasperated individual

feeling. So far as Disraeli was concerned, it was war to the

knife, and to the death. A series of assaults, so long

sustained and so vindictive, is probably unexampled in the history

of Parliamentary warfare. There was a large and growing party

of malcontents, too, in the House, who did not fail to urge on the

satire of Disraeli by their laughter and applause. His irony

became more and more polished, keen, and penetrating. His

speeches were full of refinement, but equally full of venom.

The adder lurked under the rose-leaves: the golden arrows were

tipped with deadly poison. No wonder that the sensitive

subject of all those speeches should have writhed under the hands of

his ruthless, but too skilful anatomist.

Take a few instances of Disraeli's satire. On one

occasion, he characterized the Premier as only "a great

Parliamentary middleman." And what is a middleman? "He

was a man who bamboozled one party and plundered the other, till,

having obtained a position to which he was not entitled, he called

out, 'Let us have no party! Let us have fixity of tenure!'"

This passage, however, has since been quoted against Mr. Disraeli

himself. Then he went on to describe his great Parliamentary

antagonist's speeches, recorded in Hansard, as "dreary pages of

interminable talk; full of predictions falsified, pledges broken,

calculations that had gone wrong, and budgets that had blown up.

And this not relieved by a single original thought, a single

generous impulse, or a single happy expression." Then he

described the Peel policy as "a system so matter-of-fact, yet so

fallacious; taking in everybody, though everybody knew he was

deceived; a system so mechanical, yet so Machiavellian, that he

could hardly say what it was, except a sort of humdrum hocus-pocus,

in which the 'Order of the Day' was moved to take in a nation;" and

he concluded the speech by calling on the House to prove that

"cunning is not caution, nor habitual perfidy high policy of state,"

exhorting them to "dethrone a dynasty of deception, by putting an

end to this intolerable yoke of official despotism and Parliamentary

imposture." It was in the course of the same session (1846)

that Mr. Disraeli made the happy hit of representing Sir Robert Peel

as having "caught the Whigs bathing, and run away with their

clothes,"—an idea which Punch seized upon, and worked out

with characteristic vigour. There was also a terrible sting in

his apparently off-hand, but probably studied remark on Sir Robert

Peel's habit of quotation, in which he advised him to "stick to

quotation; because he never quoted any passage that had not

previously received the full meed of Parliamentary approbation."

Of course, any mere description would fail to convey the

screaming delight with which such palpable hits were hailed on one

side of the House, and the blank dismay which they caused on the

other. Their sting lay in the tone with which the words were

uttered, and in the position of the contending parties at the time.

They were addressed to minds familiar with the person attacked, with

his history as written in Hansard, and hot with the living politics

of the day. To those who read them on the printed paper, they

may seem comparatively dead and pointless.

Disraeli's boldness increased with his success. There

was no other man on his side to compare with him. He towered

infinitely above the host of country gentlemen, who, though

exasperated Protectionists, were nevertheless for the most part

dumb, and could only find a vent for their eloquence in cheering

Disraeli's bitter attacks on the Premier. The session of 1846

brought his oratory to its climax. He then took the lead in

opposing the Premier's measure of Corn-Law Repeal, and delivered on

the occasion several of his ablest speeches, full of cutting sarcasm

and powerful invective. In the debate on the third reading of

the Corn Bill, in a strain of withering irony, he acquitted the

Premier of meditated deception in his adoption of Free-Trade

principles, "seeing that he had all along, for thirty or forty

years, traded on the ideas of others; that his life had been one

great appropriation clause; and that he had ever been the burglar of

other men's intellects." He also denounced him as the

"political pedlar, who, adopting the principles of Free Trade, had

bought his party in the cheapest market, and sold them in the

dearest." The feeling which dictated these speeches was

obviously not so much deep-rooted conviction as personal hostility

and revenge; and though Disraeli's followers may have cheered, they

could not but, at the same time, condemn much of what he so

eloquently uttered. Sir Robert Peel fell from power, and only

then did his enemy's attacks cease.

The subsequent history of Mr. Disraeli is too well known to

require comment at our hands. We do not here discuss politics

or parties. In this sketch we have aimed merely at giving an

idea of the littérateur and the statesman, whose talents,

energy, and industry have already carried him so high, and may

possibly carry him higher.

Hughendon Manor near High Wycombe, Disraeli's seat

from 1848 until his death. Now

a National Trust property. Picture Wikipedia.

With the features and general portraiture of Disraeli the

reader of Punch is already familiar; indeed, that useful

periodical may be regarded as a gallery of the portraits of living

men of mark. His external appearance is very characteristic.

A face of ashy paleness, large dark eyes, curling black hair, a

stooping gait, an absorbed look, a shuffling walk,—these are his

external marks; and once seen, you will not fail to remember

Disraeli. There is something unusual, indeed quite foreign, in

his appearance; and you could not by any possibility mistake him for

a Saxon. Notwithstanding his position, he is an exceedingly

isolated being. He makes no intimates, has few or no personal

friends,—he seems to be lonely and self-absorbed, feeding upon his

own thoughts.

|

|

|

Disraeli

and Queen Victoria, during

the latter's visit to Hughenden Manor

at the height of the Eastern crisis.

Picture Wikipedia. |

As a debater, Mr. Disraeli is entitled to a very

high rank, perhaps the highest in the present House of Commons.

But it must be confessed that his oratory is entirely intellectual.

He never touches the heart: his greatest efforts have been

satirical,—of the scathing, blighting, and destroying kind: his best

speeches have been eminently of a destructive character. Yet

their finish has been perfect,—perfect as a product of the mere

intellect. He never carries away his auditors in a fit of

enthusiasm, as O'Connell and Shiel could do. The feeling he

leaves with you is that of high admiration of his intellectual

powers,—and you cannot help saying, "What a remarkably clever man

Disraeli is!" Though usually ungainly and somewhat

supercilious in his action, no speaker can be more effective than he

is in making his "points." His by-play, as actors call it, is

perfect; and to his sneers and sarcasms he gives the fullest force

by the most subtle modulations of his voice, by transient

expressions of the features, and by the inimitable shrug; and, while

the House is convulsed by the laughter which he has raised at an

adversary's expense, he himself usually remains as apparently

unmoved and impassive, as if he were not an actor in the scene.

Such is but a brief and imperfect sketch of this remarkable

man,—lately Chancellor of the British Exchequer. His position

is a lofty one, and he has earned it solely by his talent and his

industry. He has already achieved success in many ways; but he

is competent to do much more. Whether he succeed as a great

statesman, and found an enduring reputation as a patriot and

benefactor of men, depends entirely upon himself.

――――♦――――

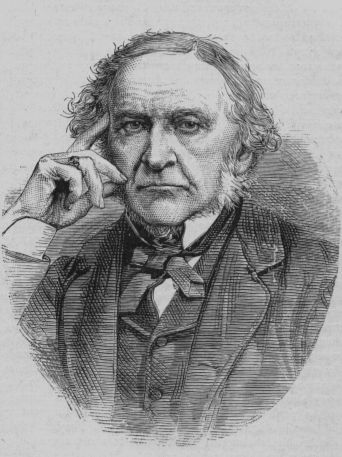

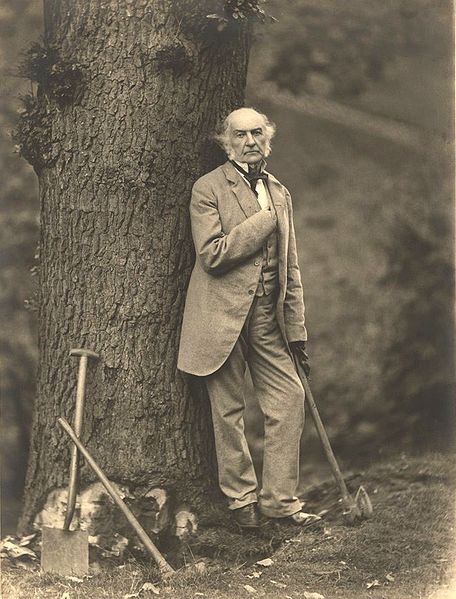

THE RT. HON. W. E. GLADSTONE.

William Ewart Gladstone (1809-98): English Statesman

and four times Prime Minister. Picture Wikipedia.

THE present

Chancellor of the British Exchequer has sprung from the middle ranks

of the people. His father, the late Sir John Gladstone, of

Fasque, was in early life a small tradesman in the town of Leith,

where he was born. The family originally came from Biggar, in

Lanarkshire, and were respectable people, though in humble

circumstances. John Gladstone, or Gladstones, as he was then

called, did not succeed in business at Leith, and afterwards removed

to Liverpool, where, at the age of twenty-two, he began the world

anew, in a very small way; but by dint of industry, energy, and

frugality, and through shrewd knowledge of men, of life, and of

business, he rapidly succeeded in accumulating an immense fortune,

chiefly in the West Indian and American trade. Indeed, rapid

though the success of Liverpool men often is, that of John Gladstone

was almost unprecedented. This was, in a great measure, owing

to his commercial skill and enterprise, which led him to embark in

ventures from which other merchants held aloof; but the safety and

wisdom of which, rash though to some they might appear, were amply

justified by the result. For example, he was the first

Liverpool merchant who ventured upon the East India trade, now of

such vast extent; his vessel, the Kinginsall, having been the very

first that sailed from Liverpool to Calcutta. He thus opened

up an immense field of profitable trade to Liverpool; and, while he

largely increased his own fortunes, he proved a benefactor to his

fellow-townsmen, which they were never slow to acknowledge.

John Gladstones not only succeeded as a merchant, but he also

achieved distinction as a member of Parliament. At different

times he represented Lancaster, Woodstock, and Berwick. Though

a Conservative, he was a man of liberal tendencies, being one of Mr.

Canning 's most attached supporters; and when Canning visited

Liverpool, during the time he represented that town, he invariably

made Seaforth House (Mr. Gladstone's residence) his temporary home.

In 1835, he obtained permission, by royal license, to drop the final

letter s in his name; and in 1846 he was created a baronet of

the United Kingdom. Having purchased extensive estates in his

native country, at Fasque and Belfour, in Kincardineshire, he

chiefly resided there in his later years, leaving his extensive

Liverpool business to the management of his sons.

Sir John Gladstone was twice married,—first to a Liverpool

lady, the daughter of Joseph Hall, Esq., by whom he had no issue;

and, secondly, to Miss Anne Robertson, a daughter of Andrew

Robertson, Provost (or Mayor) of Dingwall, a small town in the north

of Scotland, situated in the Highland county of Ross. By this

lady Sir John Gladstone had a family of four sons and two daughters.

The fourth son, William Ewart, is the subject of our present sketch.

Readers of the newspapers may have observed that, not long ago, he

paid a visit to Dingwall, the early home of his mother; and that he

still associates that place of his kindred, in his memory, with many

tender recollections. He was, on the occasion referred to,

presented with the freedom of the burgh,—a usual mode of

complimenting public men in the towns of the North; and it generally

affords an opportunity for much pleasant speech-making and exchange

of compliments, which on the above occasion was not neglected.

Sir John Gladstone, like Sir Robert Peel the elder, early

designed his son William for the legislature, and educated him with

the view of placing him there. Doubtless the youth long

remembered the beautiful face and the lofty career of Canning, his

father's favourite political leader; and he may have received

impressions from those visits of Canning to his father's house while

he was yet a boy, which exercised no slight influence upon his

subsequent career. William Ewart Gladstone was born in 1809;

he was sent to Eton School in 1821, and entered Christ Church,

Oxford, as a student, in 1829. He there distinguished himself

by his diligence, good conduct, studious habits, and classical

attainments. Amongst his fellow-students were the present Lord

Canning, with whom he entered as a student, the Duke of Newcastle,

Lord Dalhousie, Lord Elgin, Lord Harris, and Mr. Sidney Herbert.

Great hopes were entertained of his future career, even at that

early age; and these were not diminished by his appearance in 1831,

when he took a double first-class and his degree of B.A. He

had even then, too, achieved considerable eminence as a debater at

the meetings of the Oxford Debating Society, where he assumed that

liberal tone of Conservative politics which has since distinguished

him.

The Conservative party was not very strong in talent at that

time, and the burden of the battle in Parliament fell upon Peel, who

gallantly, but ineffectually, struggled to resist the democratic

tendencies of the age. When Mr. Gladstone entered the House of

Commons for Newark, in December, 1832, he was accordingly welcomed

as an important accession to the debating phalanx of the

Conservatives. Nor were public expectations in "the young

Oxonian" disappointed. In two years he had made a position in

the House, though he was then not more than twenty-five years of

age. One secret of his success as a speaker was, not that he

was so eloquent, as that he was so diligent. He made himself

thoroughly acquainted with the subjects upon which he spoke;

mastered bluebooks, statistics, Parliamentary history, and political

economy; the driest and most repulsive subjects were encountered and

unravelled by him in his search for facts. Such men always

succeed in the House. It is seen that they are conscientious

and well-informed, and when they speak, the audience know that they

have really got something to say.

Mr. Gladstone at first did what the Conservative

members of Parliament then felt impelled to do,—united with his

fellow-representatives of similar views to stem the tide of

"Reform." His first speech was delivered in reply to Lord

Howick, on the question of Negro emancipation, in which he urged the

right of the planters to compensation. He opposed, in

successive Parliaments, the reform of the Irish Church, the

reduction of the number of Irish bishops, the "Appropriation

Clause," the Dissenters' Chapel Bill, the endowment of Maynooth, the

emancipation of the Jews, and many other measures, on which his

views have since entirely changed. Indeed, Mr. Gladstone, in

the early period of his career, was regarded in the light of an

Oxford bigot; and he was stigmatized as a man of a narrow head, and

a still narrower heart. The Whig Examiner named him the

"Pony Peel," regarding Peel himself as the "Joseph Surface" of

politics. We need scarcely say how different is the

appreciation in which Mr. Gladstone is now held.

It takes a long course of education in the practical business

of life to bring out the true qualities of a man; and Mr.

Gladstone's career only proves the truth of this observation.

It appears to us that Mr. Gladstone's history may be divided into

two distinct parts;—one dating from his entry into the House of

Commons down to the death of Sir Robert Peel; the other, since that

event. During nearly the whole of the first period, he was a

pure Conservative,—his efforts being mainly devoted to resist all

change or "reform;" whereas during the second period, or since Sir

Robert Peel's famous Free-Trade policy was introduced, he has been

engaged in the initiation and practical carrying out of a series of

changes and reforms of the most extensive and influential character.

Among the many remarkable gifts of Sir Robert Peel was that

of detecting and appreciating character. He rarely failed in

the selection of the right man to support him in carrying out his

policy to a successful issue; and from an early period, he seems to

have appreciated the qualities of Mr. Gladstone. He saw much

deeper into him than most men. While others saw in him a

clever chopper of "Oxford logic," a man who could only split straws

and promulgate extreme notions of High-Church policy, Peel saw in

him a clear-sighted, practical man, of liberal tendencies and large

views. No one doubted Mr. Gladstone's scholarship, his skill

as a debater, or his earnestness as a religious man; but he seems to

have been regarded as one who lived amongst abstractions rather than

realities, and whose mind was too much filled with the theories of

the schoolmen and theologians, to attract any active sympathy from

men living in a practical and rather commonplace age.

During that first period of his career, Mr. Gladstone's style

of oratory was somewhat peculiar. It was very deferential,

subdued, mild, and rather casuistical; yet there was a mysterious

sort of charm about it, which invariably riveted the attention of

the House. Sincerity in any cause will always command

attention and respect; and these Mr. Gladstone invariably obtained.

His manner was singular in the House of Commons, where dapper

debaters and glib-tongued orators, with very little in their heads,

are always ready enough to spring to their feet, and arrogantly

deliver themselves of platitudes or blarney, to the disgust of

reporters and the dismay of the Speaker. Yet here was a man of

the most profound scholarship, who, in the quietest possible tone of

voice,—mild, clear, and harmonious,—in an abstracted, absorbed, and

unaffected manner, delivered himself of the serious utterances of a

deeply reflective and religious spirit. He was never personal,

and he carefully avoided all appeals which could serve to rouse the

violence of political or religious rancour. His

finely-organized mind shrank from all this; he thus made few

enemies, and gradually increased the number of his friends and

admirers. Still he was looked upon very much in the light of a

resurrectionized monk, quite out of his element in a hard-mouthed

modern legislature.

Now we must speak of his practical qualities, which shortly

afterwards came into light. As we have observed, Peel marked

him as a useful man, and he early secured him as a practical ally.

Mr. Gladstone's character has two distinct sides, the theoretical

and the practical, the latter of which Peel was the first to detect.

In 1834 he was nominated a Lord of the Treasury, an office which was

afterwards changed for that of Under-Secretary for the Colonies.

Great was the surprise of the quid nuncs at the intimation of

the last appointment. "What could Peel be thinking about, that

he should appoint Gladstone, the young Oxonian and religious

theorist, to so important an office?" But the quid nuncs

did not know, as Peel knew, that Gladstone had one character for the

study and another for the secretary's desk. In the latter

capacity, he soon distinguished himself as an intelligent, active,

painstaking official, thoroughly practical, knowing the business

details of his office, and, in short, possessed of all those

qualities which make the successful statesman. Peel knew his

man better than the quid nuncs, and they were afterwards

found ready enough to admit his eminent abilities. Mr.

Gladstone's first tenure of office was, however, short, as he went

out with Sir Robert Peel's ministry in 1835, on their defeat upon

the Appropriation Clause.

He remained out of office until the year 1841; and in the

interval he occupied a good deal of his leisure on literary topics.

He was a diligent contributor to periodicals; he wrote a very

admirable review of the Life of Blanco White in the Quarterly,

and published several anonymous political pamphlets. But the

work which excited the greatest interest was that entitled "The

State in its Relations with the Church," which he published at

Amiens in 1838. This book embodied his then views of the

Church, and deservedly excited a great deal of notice. It

formed the subject of one of Macaulay's best essays in the

Edinburgh Review, and it was defended by

Dr. Arnold in his Introductory

Lectures on Modern History. There were few Reviews which

passed by this book at the time of its appearance; and though Mr.

Gladstone there put forward views of the most extreme kind,

calculated to excite the most keen religious controversy,—leading,

as they seemed to lead, to religious persecution,—still they were so

evidently sincere, and the result of such conscientious inquiry, and

set before the reader in such mild and plausible language, that they

excited little hostility, though a very great deal of criticism.

Mr. Gladstone, having laid down his principle, did not

scruple to push it to its consequences, although in somewhat vague

and misty logic. His theory was based on the principle, that

all "power," as the gift of God, is to be used for his glory; and

that, in consequence, the possessors of all such power—statesmen,

legislators, and magistrates—are called upon to hallow it by joint

acts of worship. Hence the state must select a religion,

establish it, and make the people adopt it, discouraging every other

form of religion,—not by direct persecution, but by excluding the

professors of the non-established religion from civil offices, and

from all marks of national honour. Mr. Macaulay handled the

subject of Mr. Gladstone's essay in a masterly manner, showing that

the profession of a state religion by the entire members of the

state would be a gross absurdity, and not only so, but a base

tyranny. To that essay we beg to refer the attention of the

reader who would see the whole subject of Mr. Gladstone's work

thoroughly discussed in all its bearings.

Macaulay was, however, very complimentary to Mr. Gladstone.

He congratulated him, a young and rising politician, on the devotion

of a portion of his leisure to study and research; setting himself

down to the preparation of a grave and elaborate treatise on an

important part of the philosophy of government. Mr. Macaulay

also recognized in Mr. Gladstone a man well qualified for

philosophical investigation. "His mind," he says,

"is of large grasp; nor is he deficient in

dialectical skill. But he does not give his intellect fair

play. There is no want of light, but a great want of what

Bacon would have called dry light. His rhetoric, though often

good of its kind, darkens and perplexes the logic which it should

illustrate. Half his acuteness and diligence, with a barren

imagination and scanty vocabulary, would have saved him from all his

mistakes. The book, though not a good book, shows more talent

than many good books. It abounds with eloquent and ingenious

passages; it bears the signs of much patient thought; it is written

throughout with excellent taste and temper; nor does it, so far as

we have observed, contain one expression unworthy of a gentleman, a

scholar, or a Christian."

Doubtless, Mr. Gladstone was still under the strong

influences of the High-Church principles inculcated at Oxford when

he wrote his book. The main aim of the teaching of that

seminary seems to be to direct the mind backwards, rather than

forwards; to revive old traditions, and renovate old forms; to feed

upon old books, and cherish old thoughts; to make men lead lives of

the tenth century, instead of the nineteenth. But, as Mr.

Macaulay well remarks,

"It is to no purpose that a man resists the influence

which the vast mass, in which he is but an atom, must exercise on

him. He may try to be a man of the tenth century, but he

cannot. Whether he will or no, he must be a man of the

nineteenth century. He shares in the motion of the moral as

well as in that of the physical world. He can no more be as

intolerant as he would have been in the days of the Tudors, than he

can stand in the evening exactly where he stood in the morning.

The globe goes round from west to east, and he must go round with

it."

What Mr. Gladstone mainly wanted at this time, to bring out

his better qualities, was more abundant intercourse with men, and

larger acquaintance with the living world about him. And,

fortunately for himself and his country, those opportunities shortly

after occurred to him. In 1841 Sir Robert Peel returned to

power, and, with his usual sagacity, filled his offices with the

best men about him. Many of these were comparatively young and

untried, but they amply justified the selection of their chief.

Mr. Gladstone, the Oxonian, was, strange to say, placed at the Board

of Trade, first as Vice-President, and afterwards as President.

He was also made Master of the Mint, and a member of the Cabinet.

Sir Robert Peel received most valuable aid from his young coadjutor,

with whom he confidentially consulted in all the difficult debates

which arose out of his proposed modifications of commercial law.

Mr. Gladstone, who had been regarded, even by many of his own party,

as a dreamy enthusiast, astonished the public by the mastery which

he exhibited over the minutiæ of commercial and financial

arrangements, pursuing the business of his office into the minutest

details, and bringing to bear upon practical questions a large

amount of information, drawn from all sources,—from the

under-current of commerce which flows in warehouses and

country-houses, as well as from the more readily accessible library,

full of statistical tables and Parliamentary returns. He was

unwearied in his assiduity, and always ready to defend the measure

of his chief. Indeed, during the progress of the Free-Trade

measures, he was confessedly Sir Robert's right arm. And not

in Parliament only was he indefatigable, but also in the press.

In his pamphlet, published in 1844, "On the Ministry and the Sugar

Duties," he brought the full force of fact and argument to bear in

favour of the total abolition of differential duties; and in an able

article published by him in the "Colonial and Foreign Quarterly," he

showed a disposition to go much further in the direction of Free

Trade than was supposed to be contemplated by the party then in

power.

In 1845 Mr. Gladstone resigned office, on conscientious

grounds. Having, in his book on "The State in its Relations to

the Church," stated opinions adverse to the continued endowment of