WHAT reader of

books is there who does not feel that he owes a debt of gratitude to

Leigh Hunt, for his many beautiful thoughts, his always cheerful

views of life, and his generous efforts, extending over a period of

half a century, on behalf of the freedom and happiness of the human

family? His name is associated in our minds with all manner of

kindness, love, beauty, and gentleness. He has given us a fresh

insight into nature, made the flowers seem gayer, the earth greener,

the skies more bright, and all things more full of happiness and

blessing. By the magical touch of his pen, he "kissed dead things to

life." Age, which dries up the geniality of so many, brought no

change to him. To the last he was spoken of as the "grey-haired

boy,"—"the old-young poet, with grey hairs on his head, but youth in

his eyes,"—and the perusal of his Autobiography, written in his old

age, serves to bring out charmingly the prominent features of his

life.

Leigh Hunt's temperament doubtless owed something to the warm,

sunshiny clime in which his progenitors lived, that of Barbados, in

the West Indies. His grandfather was a clergyman there, and his

grandmother an O'Brien,—very proud of her alleged descent from

certain mythical Irish kings of that name. Their son (Leigh Hunt's

father) was sent to Philadelphia, then belonging to the English

American colonies, to be educated; and there he married and settled. But on the war of the American Revolution breaking out, he entered

so warmly into the cause of the British government, that he was

mobbed, narrowly escaped tarring and feathering, and ultimately fled

to England, his wife and little family following him. He was there

ordained a clergyman by the Bishop of London, and became famous as a

preacher of charity sermons. He was fond, however, of pleasurable

living; drank more than was good for him; got into pecuniary

difficulties, from which he never escaped; and lived a life of

shifts and expedients, always trusting, like Mr. Micawber, to

"something turning up." He found a brief friend in the Marquis of

Chandos, and was engaged by him as tutor for his nephew, Mr. Leigh,

after whom Leigh Hunt was subsequently named.

To be tutor in a duke's family is often a sure road to a bishopric,

or some other high promotion in the Church: but the tutor in this

case had no such good fortune: his West Indian temperament spoiled

all: he had ceased to think the British government perfect, and he

did not hesitate to express his opinions freely thereon. So, after

leaving this situation, he lapsed again into difficulties, and

afterwards into distress and debt. Still his happy and joyous nature

bore him up, even though he was haunted by duns and became familiar

with prisons. "Such an art had he," said his son, "of making his

home comfortable when he chose, and of settling himself to the most

tranquil pleasures, that, if she could have ceased to look forward

about her children, I believe, with all his faults, those evenings

would have brought unmingled satisfaction to her, when, after

settling the little apartment, brightening the fire, and bringing

out the coffee, my mother knew that her husband was going to read Saurin or Barrow to her, with his fine voice, and unequivocal

enjoyment."

Leigh Hunt's mother was of American birth, a Philadelphian; she had

"no accomplishments but the two best of all, a love of nature and a

love of books." She was a woman of great energy of principle, though

timid and gentle almost to excess. Her husband's great dangers at

Philadelphia, and the imminent risk of shipwreck which she, with her

family, ran on the voyage to England, had shaken her soul as well as

frame. Her son said of her:

"The sight of two men fighting in the

streets would drive her in tears down another road; and I remember,

when we lived near the Park, she would take me a long circuit out of

the way, rather than hazard the spectacle of the soldiers. Little

did she think of the timidity with which she was thus inoculating

me, and what difficulty I should have, when I went to school, to

sustain all those pure theories, and that unbending resistance to

oppression, which she inculcated. However, perhaps it ultimately

turned out for the best. One must feel more than usual for the sore

places of humanity, even to fight properly in their behalf. One

holiday, in a severe winter, as she was taking me home, she was

petitioned for charity by a woman, sick and ill-clothed. It was in

Black-friars Road, I think, about midway. My mother, with the tears

in her eyes, turned up a gateway, or some such place, and beckoning

the woman to follow, took off her flannel petticoat and gave it to

her. It is supposed, that a cold which ensued fixed the rheumatism

upon her for life. Her greatest pleasure, during her decay, was to

lie on a sofa, looking at the setting sun. She used to liken it to

the door of heaven; and fancy her lost children there waiting for

her."

As a man is but his parents, or some other of his ancestors,

drawn out, so Leigh Hunt, in his own life and history, was but a

repetition of his father and mother, and an embodiment of their

character in about equal proportions; inheriting from the one a

joyous and happy temperament, and from the other tenderness and a

deep love of nature and books.

Leigh Hunt was born at Southgate, in the parish of Edmonton, on the

19th of October, 1784, in the midst of the beautiful pastoral

scenery which he afterwards loved to paint in his works. During his

infancy he was delicate and sickly, and was watched over with great

tenderness by his mother. To assist his recovery, he was taken to

the coast of France for a short time, and returned improved in

health. He was very nervous, and easily frightened by his elder

brothers, who delighted to terrify him by ghost-stories and

pretended apparitions.

The great events which were passing in Hunt's childhood rose up

afterwards in his mind like a dream,—the American Revolution

completed, the French Revolution beginning; the eloquence of Burke,

and the rivalries of Pitt and Fox; the poetry of Cowper and Young,

and the novels of Miss Burney and Mrs. Inchbald; the violent

politics of Wilkes, and the gallantries of the young Prince of

Wales. These were the days of pigtails and toupees, when ladies wore

hoops, and lay all night with their hair three stories high, waiting

for the spectacle of next day,—a very different style of living and

dressing from the present.

The boy went to school at Christ Church Hospital, where Lamb and

Coleridge were also educated about the same time. The thrashing

system, which was then in vogue in all schools, horrified him; his

gentle spirit made him the sport of the other boys, and he "went to

the wall" till he gained strength and address to stand his own

ground. Even as a boy, he had the reputation of a romantic

enthusiast. He fought only once, beat his opponent, and made a

friend of him.

While only a school-boy, Leigh Hunt fell in love with the

Muses,—with Collins and Gray passionately,—and he already began to

write verses. He also fell in love in another way,—with a charming

cousin, Fanny Dayrell.

"Fanny was a lass of fifteen, with little

laughing eyes, and a mouth like a plum. I was then (I feel as if I

ought to be ashamed of it) not more than thirteen, if so old; but I

had read Tooke's Pantheon, and came of a precocious race. My cousin

came of one too, and was about to be married to a handsome young

fellow of three and twenty. I thought nothing of this, for nothing

could be more innocent than my intentions. I was not old enough, or

grudging enough, or whatever it was, even to be jealous. I thought

everybody must love Fanny Dayrell; and if she did not leave me out

in permitting it, I was satisfied. It was enough for me to be with

her as long as I could; to gaze on her with delight as she floated

hither and thither; and to sit on the stiles in the neighbouring

fields, thinking of Tooke's Pantheon. Three fourths of my heart was

devoted to friendship; the rest was in a vague dream of beauty, and

female cousins, and nymphs and green fields, and a feeling which,

though of a warm nature, was full of fear and respect."

In course of

time Fanny married, and his first passion died away, but was not

forgotten.

At Christ Church, Hunt formed intimacies with men afterwards famous

in literature. There was Wood, afterwards Fellow of Pembroke

College, Cambridge; Mitchell, the translator of Aristophanes, and a

Quarterly Reviewer; and Barnes, the future editor of the Times. With

the last named he learned Italian, and the two went shouting Metastasio together, as loud as they could bawl, over the Hornsey

fields.

At fifteen he took leave of his school books and school friends,

and, after going about eight years bareheaded, put on the fatal hat. He set about writing verses and haunting book-stalls,—the occupation

of no small part of his future life. The first verses he wrote were

collected and published by subscription. These, he confesses, were

but "a heap of imitations, all but absolutely worthless." The book

was, however, successful, particularly in the metropolis; and the

author found himself a kind of "Young Roscius" in verse. His

grandfather in America, sensible of the young author's fame, wrote

to him that, if he would come to Philadelphia, he would "make a man

of him;" to which his answer was, that "men grew in England as well

as America."

After joining as a private in the Volunteers, who were called into

existence by the rumour of Bonaparte's coming, and going the round

of the London theatres, taking his full of pleasures, Leigh Hunt

appeared, for the first time, as a prose essayist, in the columns of

the Traveller, now the Globe, newspaper, under the signature of "Mr. Town, Junior," for which he received as his reward some five or

six copies of each paper in which his essays appeared. He wrote a

long mock-heroic poem about the same time, and made several attempts

at farce, comedy, and tragedy reading largely in Goldsmith,

Voltaire, novels, and history, promiscuously. His brother, John

Hunt, set up a paper called "The News," in 1805, on which the

subject of our memoir, then in his twentieth year, went to live with

him, and wrote the theatricals for the journal. He there commenced

the system of independent criticism, and adhered to it, though he

afterwards frankly admitted that he then knew nothing of either

actors or acting. In the midst of his labours, he fell into

ill-health and melancholy; palpitations, hypochondria, dyspepsia—in

other words, the "literary disease" had attacked him. He

recovered, by ceasing his occupation for a time and taking exercise;

but he gained more than a cure. "One great benefit," he says,

"resulted to me from this suffering. It gave me an amount of

reflection such as, in all probability, I never should have had

without it; and if readers have derived any good from the graver

portion of my writings, I attribute it to this experience of evil. It taught me patience; it taught me charity (however imperfectly I

may have exercised either); it taught me charity even towards

myself; it taught me the worth of little pleasures, as well as the

utility and dignity of great pains; it taught me that evil itself

contained good; nay, it taught me to doubt whether any such thing as

evil, considered in itself, existed; whether things altogether, as

far as our planet knows them, could have been so good without it;

whether the desire, nevertheless, which nature has implanted in us

for its destruction, be not the signal and the means to that end;

and whether its destruction, finally, will not prove its existence,

in the meantime, to have been necessary to the very bliss that

supersedes it."

We could not, perhaps, have selected a passage from

Leigh Hunt's writings that embodies his philosophy more completely

than this does.

The year 1808 saw him and his brother John afoot with an important

enterprise,—the establishment of the since famous Examiner

newspaper. It started as a Radical print,—a bold thing in those

perilous times, when a man dared scarcely say the thing he would

without risk of Horsemonger Jail, or worse. The new paper attracted

attention, and brought around it many choice and kindred spirits. Leigh Hunt now mixed among literary men, whom he has described in

his Autobiography. Of Theodore Hook, Thomas Campbell, Horace Smith,

Fuseli, Matthews, Godwin, Bonnycastle, Byron, Shelley, Keats,

Wordsworth, and others, he furnishes many recollections. Horace

Smith (one of the authors of the "Rejected Addresses") he speaks of

as "delicious."

"A finer nature than Horace Smith's, except in the

single instance of Shelley, I never met with in man; nor even in

that instance, all circumstances considered, have I a right to say

that those who knew him as intimately as I did the other, would not

have had the same reasons to love him. Shelley said to me once: 'I

know not what Horace Smith must take me for, sometimes; I am

afraid he must think me a strange fellow; but it is so odd, that the

only truly generous person I ever knew, who had money to be generous

with, should be a stock-broker! And he writes poetry, too,'

continued Shelley, his voice rising in a fervour of astonishment,—'he writes poetry and pastoral dramas, and yet knows how to make

money, and does make it, and is still generous!'"

Here is an odd outline of a man!

"Bonnycastle was a good fellow: he

was a tall, gaunt, long-headed man, with large features and

spectacles, and a deep, internal voice, with a twang of rusticity in

it, and he goggled over his plate like a horse. I often thought that

a bag of corn would have hung well on him. His laugh was equine, and

showed his teeth upwards at the sides."

This was the famous

algebraist.

The Examiner, in which the brothers were boldly discussing the

politics of the day, very soon drew upon it the keen eyes of men in

power, who waited for an opportunity of pouncing upon it. The

remarks on a pamphlet published by Major Hogan, in which the

notorious Mrs. Clarke's dispensation of the Duke of York's patronage

in return for hard cash was broadly hinted, excited marked

attention, and the government commenced an action against the

proprietors of the paper, from which they were only saved by a

member of the House of Commons (Colonel Wardle) taking up the

subject, and bringing up Mrs. Clarke (whose relation to the Duke of

York was well known) for examination at the Bar of the House, when

the whole thing was exposed by her, with barefaced effrontery. Before another year was out, the government instituted a second

prosecution, for a sentence in an article which, at this time of

day, would look exceedingly mild, if appearing in the daily Times. The

Morning Chronicle was first prosecuted for having copied the

article, but the jury pronounced an acquittal, and the action

against the Examiner again fell to the ground. A third prosecution

was shortly commenced by the government against the proprietors, for

having copied an article from the Stamford News, against military

flogging; but on a trial, the jury acquitted them.

About this time, John Hunt started a quarterly magazine, called "The Reflector," which Leigh Hunt edited, and of

which only four

numbers appeared. Charles Lamb, Barnes (afterwards of the Times),

and some other Christ Church Hospital men, were amongst its

contributors. In it first appeared Leigh Hunt's "Feast of the Poets,"

in which he satirized many of his Tory contemporaries,—amongst

others Gifford, the editor of the Quarterly, the only man for whom

he seems to have entertained a thorough dislike. Amongst the

poetical effusions in the Reflector also appeared one on a famous

dinner given by the Prince of Wales to a hundred and fifty of his

particular friends. The Prince had just deserted the Whig party, and

gone over to the Tories, so that there was a strong savour of

political gall in the piece. About the same time, an article on the

Prince, in connection with the annual dinner on St. Patrick's day,

was inserted in the Examiner, and on this the government fastened,

as the means of crushing the paper and its proprietors. The point in

the article at which the Prince was understood to have taken violent

offence was, that he whom his adulators styled "an Adonis in

loveliness" should be plainly designated as "a corpulent man of

fifty," which he was. The government prosecution succeeded. The

proprietors of the paper were fined one hundred pounds, and

condemned to two years' imprisonment each, in separate jails!

Leigh Hunt's prison-life was thoroughly characteristic of him. He

was in a very delicate state of health when first imprisoned in

Horsemonger Jail, but he determined to make the best of it. His

wife and friends were allowed to be constantly with him. Owing to

his delicate state of health, the doctor proposed he should be

removed into the infirmary, and the proposal was granted. And now

see how a happy mind and a sound conscience can make even a

prison-house a place of joy.

"The infirmary was divided into four wards, with as many small rooms

attached to them. The two upper wards were occupied, but the two on

the floor had never been used; and one of these, not very

providently (for I had not yet learned to think of money) I turned

into a noble room. I papered the walls with a trellis of roses; I

had the ceiling coloured with clouds and sky; the barred windows I

screened with Venetian blinds; and when my book-cases were set up

with their nests, and flowers and a piano-forte made their

appearance, perhaps there was not a handsomer room on that side the

water. I took a pleasure, when a stranger knocked at the door, to

see him come in and stare about him. The surprise on issuing from

the Borough, and passing through the avenues of a jail, was

dramatic. Charles Lamb declared there was no other such room, except

in a fairy-tale.

"But I possessed another surprise, which was a garden. There was a

little yard outside the room, railed off from another, belonging to

the neighbouring ward. This yard I shut in with green palings,

bordered it with a thick bed of earth from a nursery, and even

contrived to have a glass-plot. The earth I filled with flowers and

young trees. There was an apple-tree, from which we managed to get a

pudding the second year. As to my flowers, they were

allowed to be perfect. Thomas Moore, who came to see me with Lord

Byron, told me he had seen no such heart's-ease. Here I wrote and

read in fine weather, sometimes under an awning. In autumn, my

trellises were hung with scarlet runners, which added to the flowery

investment. I used to shut my eyes in my arm-chair, and affect to

think myself hundreds of miles off.

"But my triumph was in issuing forth of a morning. A wicket out of

the garden led into the large one belonging to the prison. The

latter was only for vegetables; but it contained a cherry-tree,

which I saw twice in blossom. I parcelled out the ground, in

imagination, into favourite districts. I made a point of dressing

myself as if for a long walk; and then, putting on my gloves, and

taking my book under my arm, stepped forth, requesting my wife not

to wait dinner if I was too late. My eldest little boy, to whom Lamb

addressed some charming verses on the occasion, was my constant

companion, and we used to play all sorts of juvenile games together. It was, probably, in dreaming of one of these games (but the words

had a more touching effect on my ear) that he exclaimed one night in

his sleep, 'No, I'n not lost; I'm found.' Neither he nor I were very

strong at the time; but I have lived to see him a man of forty, and

wherever he is found, a generous hand and a great understanding will

be found together."

The two years slowly passed, during which the visits of many

friends, Hazlitt, Lamb, Shelley, Bentham, and others, cheered Leigh

Hunt's captivity. He read and wrote verses; composed the principal

part of the "Story of Rimini;" furnished articles and criticisms for

the Examiner; and anxiously looked forward to the hour of his

release. Meanwhile, there were generous friends who volunteered to

pay the fine for him, but their offer was declined. The Hunts would

bear their own burdens, and maintain their own independence while

they could. At length, on the 3d of February, 1805, they were free.

"It was now thought that I should dart out of my cage like a bird,

and feel no end in the delight of ranging. But, partly from

ill-health and partly from habit, the day of my liberation brought a

good deal of pain with it. An illness of a long standing, which

required a very different treatment, had by this time been burnt in

upon me by the iron that enters into the soul of the captive, wrap

it in flowers as he may; and I am ashamed to say, that, after

stopping a little at the house of my friend Alsager, I had not the

courage to continue looking at the shoals of people passing to and

fro as the coach drove up the Strand. The whole business of life

seemed a hideous impertinence. The first pleasant sensation I

experienced was when the coach turned into the New Road, and I

beheld the old hills of my affection, standing where they used to

do, and breathing me a welcome.

"It was very slowly that I recovered anything like a sensation of

health. The bitterest evil I suffered was in consequence of having

been confined so long in one spot. The habit stuck to me on my

return home, in a very extraordinary manner, and made, I fear, some

of my friends think me ungrateful. This weakness I have outlived;

but I have never thoroughly recovered the shock given to my

constitution. My natural spirits, however, have always struggled

hard to see me reasonably treated. Many things give me exquisite

pleasure, which seem to affect other men in a very minor degree; and

I enjoyed, after all, such happy moments with my friends, even in

prison, that, in the midst of the beautiful climate which I

afterwards visited, I was sometimes in doubt whether I would not

rather have been in jail than Italy."

The "Story of Rimini" was published shortly after Leigh Hunt's

release from prison. It was greatly and deservedly admired, but it

could not prove very remunerative to him. In order to meet demands

which had been accruing upon him, he also published "The

Indicator," but want of funds prevented the publication being

advertised and pushed as it deserved. The Examiner was now declining

in circulation and receipts, for the party against which it

struggled was entirely in the ascendant. We fear, also, that its

business management must have suffered from the long imprisonment of

the two proprietors, as well as from the acknowledged deficiency of

at least one of them in business capacity. "I had never attended,"

says Leigh Hunt,

"not only, to the business part of the Examiner,

but to the simplest money matter that stared at me on the face of

it. I could not tell anybody who asked me what was the price of its

stamp! Do I boast of this ignorance? Alas! Alas! I have no such

respect for the pedantry of absurdity, as that. I blush for it; and

I only record it out of a sheer, painful movement of conscience, as

a warning to those young authors who might be led to look on such

folly as a fine thing; which, at all events, is what I never thought

it myself. I did not think about it at all, except to avoid the

thought; and I only wish that the strangest accidents of education,

and the most inconsiderate habit of taking books for the only end of

life, had not conspired to make me so ridiculous. I am feeling the

consequences at this moment, in pangs which I cannot explain, and

which I may not live long to escape."

In the winter of 1821, Leigh Hunt set sail, with his wife and seven

children, on a voyage to Italy, to join Byron and Shelley, then

residing there. After a tremendous storm, the vessel in which they

sailed was driven into Dartmouth, where they re-landed, and passed

on to Plymouth, where they waited until May, 1822, and from thence

sailed to Leghorn. The residence in Italy was not pleasant; it was

embittered by the death of Shelley and of Keats, and the obvious

alienation of Byron. The tedium was not relieved by the pleasures

which opulence supplies, for, from this time, Leigh Hunt seems to

have been haunted by the ghost of Poverty. Everything that he

touched failed. "The Liberal," a quarterly publication brought out

by him while in Italy, reached only the fourth number, though Byron,

Shelley, and Hazlitt wrote for it, as well as himself. The literary

Examiner, a new publication, set up by his brother, also failed; and

the political Examiner, the newspaper, was now in the crisis of its

difficulties: it shortly after passed into other hands, when it

prospered. Leigh Hunt, in the midst of these failures, grew sick of

Italy. "I was ill, unhappy, and in a perpetual low fever," he says. He longed for the sight of English hedgerows and green fields, to

wander through paths leading over field and stile, across bay-fields

in June, and through woods full of wild-flowers. "To me," he says,

"Italy had a certain hard taste in the mouth. The mountains were

too bare, its outlines too sharp, its lanes too stony, its voices

too loud, its long summer too dusty. I longed to bathe myself in the

grassy balm of my native fields."

He reached home in 1823, and commenced anew a struggle with

difficulties. Perhaps "struggle" is too strong a word. Leigh Hunt

seems to have been playing with life, even with its sorrows, all the

way through. He was not a man to grapple with a difficulty and

overcome it; but to float alongside of it rather carelessly, and say

pleasant things about it. He had a good deal of his father's West

Indian temperament in him, and loved to lie basking in the sun,

building castles in the air. He wrote occasional essays and poems

from time to time, for monthly magazines; and, for a bookseller, who

had assisted him to return to England, a novel called "Sir Ralph

Esher." He also obtained pecuniary assistance from friends, and

struggled on the best way he could. He started a new periodical, "The Companion," which did not live long; then "The Tatler," a daily

literary and theatrical paper, which nearly killed him, as he wrote

it all; "Chat of the Week" was tried, and failed too. A

subscription list was got up for a new edition of his poems, which

helped him somewhat. Then he wrote for "The True Sun," which also

died; next he edited "The Monthly Reporter," which did not survive

long. "The London Journal" lived through two volumes, and then gave

up the ghost; it was too literary, too refined and recherché, for

the mass of cheap readers; it aimed too high above their heads. And

yet it contains some of Leigh Hunt's best writings, which will

perhaps live the longest. Next he wrote "Captain Sword and Captain

Pen," the "Legend of Florence," (a play,) and several other plays

not yet printed. All this mass of literary work barely enabled him

to live, eked out "though it was by frequent writings in the

Reviews. "The Legend of Florence " was his most profitable work,

bringing him in about two hundred pounds; and perhaps, too, it helped

him to his pension. He had, before this, on two occasions received

two hundred pounds from the Royal Bounty Fund, to enable him to

live. His more recent works were "The Palfrey," "Imagination and

Fancy," "Wit and Humour," "Stories from the Italian Poets," the "Jar

of Honey," the "Book for a Corner," and "The Town." Several of these

originally appeared as contributions to the magazines and

newspapers. His book entitled "Lord Byron and his Contemporaries"

was published many years ago, and it was one that its author himself

wished to be forgotten, and we say no more of it here.

Notwithstanding the life of ill-health, and of difficulty, which

Leigh Hunt led, it may be pronounced on the whole to have been a

happy life. It is the heart that makes life sweet, not the purse,—it

is pure and happy thoughts, a well-stored mind, and a genial nature,

full of sympathy for human kind. In all these respects, a happy lot

has been Leigh Hunt's, though wealth has been denied him. There are

few men who could say, like him, towards the close of life:

"I am

not aware that I have a single enemy, and I accept the fortunes,

good and bad, which have occurred to me, with the same disposition

to believe them the best that could have happened, whether for the

correction of what was wrong in me, or for the improvement of what

was right. I have never lost cheerfulness of mind or opinion. What

evils there are, I find to be, for the most part, relieved with many

consolations; some I find to be necessary to the requisite amount of

good; and every one of them I find come to a termination, for either

they are cured and live, or are killed and die; and in the latter

case I see no evidence to prove that a little finger of them aches

any more."

――――♦――――

HARTLEY COLERIDGE.

Hartley Coleridge (1796-1849), English

writer and eldest son of the poet

Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

|

"Nor child, nor man,

Nor youth, nor sage, I find my head is grey,

For I have lost the race I never ran:

A rathe December blights my lagging May;

And still I am a child; though I be old,

Time is my debtor for my years untold."

SONNETS. |

THE life of

Hartley Coleridge reminds one of a painful dream. There was little

health or soundness in it. The man was conscious of this himself,

and was full of lamentations as to his want of purpose and

self-control, which he took no pains to amend. That he had great

talents will be conceded,—that he had what is called genius is not

so clear. But what powers he had he grievously misused. He was

always calling on Jupiter, but would not help himself. In his poems

he preached purity, and in his life he practised self-indulgence. Is

such a career excusable in any man,—in a day-labourer or a

shopkeeper? then how much less excusable in one who was competent to

be a great teacher, and whose talents were equal to the highest

vocation?

We hold that the literary man or poet is as much under obligation to

lead a pure and virtuous life as any other man, and that the fact of

his talent or his genius is not a palliation, but an aggravation, of

offences committed by him against public morality. Intellectual

powers are gifts committed to men to subserve their own happiness,

as well as to promote the enlightenment of their kind. Poetic

powers, if employed by the possessor merely in dreamy indolence, and

in the indulgence of the luxury of imaginative thinking, are not

rightfully, but wrongfully, applied. In such a case the poet's

enjoyment is sensual and selfish. He may spend his time in arranging

phrases,—embodying beautiful ideas it may be; but all the while he

is not so much discovering, enforcing, or disseminating truth, as

luxuriating in his own tastes. If he spends his life in the

meantime wastefully and hurtfully, his great gifts are naught, and

might as well not have been. What is thought or thinking

worth, unless it help forward the life, and is illustrated in the

life? What are poetic dreams or imaginings, if the man's daily

conduct be at constant variance with them?

It used to be too much the case with the poets of a former

age, to claim a kind of immunity from the ordinary laws of life.

The poet used to be pictured as a man out at elbows. This old

notion might be a vulgar one, but it must have been formed on some

basis of experience. Hogarth's picture of the "Distressed

Poet" probably was not far from the truth. The literary

character has become greatly elevated since then, and the lives of

Wordsworth, Southey, Moore, Rogers, and others, amply prove that

poetic gifts are not incompatible with a fair share of ordinary

worldly prudence; that authors, as a class, are not necessarily

poor, hungry, and drunken. But there are still to be met with,

here and there, young dapperlings of poets, apt at stringing phrases

together about unrequited genius, and ready to cite the fate of

Burns, Savage, and Chatterton,—perhaps even to contemplate with

sympathy, if not with feelings akin to admiration, the lives of such

as Hartley Coleridge. Their sentimental reveries are full of

despair, sighs, cries of revolt, and hopelessness; and if you say a

word in deprecation of such a strain, they cry out, "Be still!

I am a poet;—you! you are only flesh and blood; you don't comprehend

me:—leave me to my illusions." But really intelligence and

poetry are not to be regarded apart from morality. It is not

enough that a man is intelligent, and writes delicious verse.

If he is a drunkard or immoral, we cannot excuse him any more than

an ordinary man. Genius affords no palliation in such a case;

where a man's talents are great, his blame is only the more if he

egregiously misuses them.

And yet we admit that much is to be said in palliation of the

life of Hartley Coleridge. Doubtless, our constitution and

character in no small degree depend upon the originators of our

being,—and not only so, but our tastes, idiosyncrasies, sympathies,

habits, and even modes of thought. Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

with his abounding gifts, was improvident, feeble of purpose, and

self-indulgent to excess; and his son seems to have inherited all

his frailties, together with a considerable portion of his genius.

The child was born in dreams, he lived in dreams, and in dreams he

died. He is said to have puzzled himself, when a child, about

the reality of existence! Sitting on the knee of old Jackson,

Southey's humble friend, he would pour out the most strange

speculations, and weave the wildest inventions. When only

eight years old, he found a spot upon the globe, which he peopled

with an imaginary nation, to whom he gave an imaginary name,

imaginary language, imaginary laws, and an imaginary senate.

These day-dreams he is said to have in course of time believed as

real; and his relations encouraged the dreamy boy, and made a wonder

of him. His dreams even became a more real world to him than

the actual world, in which he lived. Then his father early

crammed him with Greek, beginning at ten years old, though his

instruction in this, as in other branches of knowledge, was

interrupted and desultory. He had always abundant time to

build his castles in the air, and to carry on the affairs of his

dream-land, which he called Ejuxria. He was constantly forming

"plans,"—dreaming of doing things which were never to be done,—until

the practice became at length habitual with him, and was gradually

welded into his life.

Living in this dream-land of his, the boy became morbidly

shy. He never played with his fellows. He passed his

time in reading, walking, dreaming to himself, or telling his dreams

to others. His uncle, Southey, used to tell him that he had

two left hands. He lived not the life of other boys, but

spun romances and tales for them of immense length, and kept them

awake for hours together, when they lay in bed at night, during

their recital. For the boy had already the gift of

extraordinary powers of speech,—another inheritance from his gifted

father. But he never took a high place at school. Boys

of very commonplace talents, but with application and industry,

rarely failed to take the lead of him. "Unstable as water,

thou shalt not excel," might be said of his whole life. "While

at school," says his brother,

"a certain infirmity of will, the specific evil of

his life, had already shown itself. His sensibility was

intense, and he had not wherewithal to control it. He could

not open a letter without trembling. He shrank from mental

pain,—he was beyond measure impatient of constraint. He was

liable to paroxysms of rage, often the disguise of pity,

self-accusation, or other painful emotion,—anger it could hardly be

called,—during which he bit his arm or finger violently. He

yielded, as it were unconsciously, to slight temptations,—slight in

themselves, and slight to him,—as if swayed by a mechanical impulse

apart from his own volition. It looked like an organic

defect,—a congenital imperfection. I do not offer this as a

sufficient explanation. There are mysteries in our moral

nature upon which we can only pause and doubt."

Hartley went to college at Oxford, where he was supported by

his father's friends and relatives,—for his father was at the time

in embarrassed circumstances, and could not afford the

expense,—could scarcely even maintain himself. He there

distinguished himself chiefly by his extraordinary powers as a

converser at "wine-parties," where he would hold forth by the hour

on any subject that offered. He spent his vacations at

Highgate or Keswick, where he had the advantages of association with

many distinguished literary men. He was still living in

dreams,—reading Wordsworth more than the classics, and fitting

himself rather for the career of a dreamer than for the life of a

working, active man. He succeeded, however, in obtaining a

fellowship at Oriel, which was the source of no small joy to his

friends. But he enjoyed his position only for a very short

time. "At the close of his probationary year," says his

brother, "he was judged to have forfeited his Oriel Fellowship, on

the ground, mainly, of intemperance." This, we shall find, was

the great blemish of his after-life.

Then he went to London, to maintain himself by his pen; but

his dreamy, purposeless character accompanied him: he failed to

exert himself,—wanted industry,—made plans, which remained

such,—procrastinated from day to day,—and of course he failed.

The successful literary man must be a hard worker, and not a mere

dreamer; but this young man had never trained himself to habits of

industry, nor had any one else so trained him; so he failed,—taking

refuge in intoxication, and often disappearing for days together.

For about two years he resided in London, occasionally contributing

small pieces to the London Magazine; but this scrambling life

only served to aggravate his weaknesses, and the scheme was then

proposed of taking a school for him in the north of England.

Hartley's "genius" revolted at the proposal, but at last he

consented, commenced the work without heart, without purpose, and

failed again. That was at Ambleside, whither his friends had

thought it advisable now to remove him. His habits remained

the same, and he occasionally, though undesignedly, led others into

the same excess with himself. Yet he was not without bodily

and intellectual strength, had he but chosen to use it. In one

of his letters to his brother he says: "I cannot find that either my

cares or my follies have materially diminished my bodily or

intellectual vigour." He was perfectly conscious of the folly

and unworthiness of the course he was pursuing, and often overflowed

with wise moral reflections on the subject. But he would make

no effort to rise, and only sunk to lower depths. One of the

most eminent of his friends on the Lakes relates that he latterly

ceased to call on him,—

"it was so ridiculous and pitiable to find the poor,

harmless creature, amid the finest scenery in the world, and in

beautiful summer weather, dead drunk at ten o'clock in the morning."

A publisher at Leeds having engaged him to write a book on

the "Worthies of Yorkshire," found that the work proceeded so

slowly,—Hartley procrastinating from day to day, as was his

wont,—that he induced him to go over to Leeds and write it there.

While at Leeds, his life was of the usual description, fitful in

labour, irresolute, often desponding, and as often breaking off into

fits of dissipation and wandering. He would disappear for days

together, and the printer's boys were sent scouring about the

country in search for him,—sometimes finding him in a hedge-bottom,

at other times in an obscure beer-shop. When, after one of

these wanderings, he retraced his steps home by himself, he would

hang about the house at the end of the street, not having the

courage to enter, until some messenger, sent out to watch for his

return, would lead him back,—often in a pitiable state. All

this was very lamentable: and what is the more extraordinary, during

this time his brain was teeming with fancy, with poet's dreams, with

beautiful thoughts, such as an angel of purity might have

entertained. Never, perhaps, was there a life more utterly at

variance with his thoughts than that of Hartley Coleridge.

It was so to the end. He deplored his habits, but did

not change them. He lamented his indolence, but would not

work. His poetry breathed aspirations after purity, but his

life remained impure and grovelling. And yet he was beloved by

all,—loved because of his amiability, his inoffensiveness, his

almost helplessness. He remained (to use his own words)

|

"Yet to the last a rugged wrinkled thing,

To which young sweetness did delight to cling." |

Children doted on Hartley Coleridge,—himself a child.

Nature in him appeared reversed; for in his infancy he was a man in

the maturity of his fancy, and in his advanced years he was as a

helpless child among men,—a child with grey hairs, for his head

early became silver-white, though the grey hairs brought no wisdom

with them. And yet his literary culture was great; his

knowledge of books was immense; and the elegant manner in which he

would dilate upon lofty themes charmed all hearers. In the

aspect of nature, his converse was like that of a god.

The only after incidents that occurred worthy of note in

Hartley Coleridge's life were his temporary occupation as a

schoolmaster at Sedburgh, and his appearance as a contributor to

Moxon's edition of some of the older British Poets,—for which, after

great procrastination, he wrote the introduction to the works of

Massinger. A similar introduction to the works of Ford was

committed to him, and was in hand for years, but he had not

sufficient industry nor application to complete it. But he

occasionally contributed a paper to Blackwood's Magazine,

when the fit of writing came upon him. A collection of these

articles, with his "Marginalia," written by him in books while

reading them, has recently been published.

Such is a brief outline of this blurred and blotted life.

A few months before his death, he wrote the following lines in a

copy of his poems, alluding to his intention of publishing another

volume, which he had bound himself under bond to furnish, and, we

have been informed, had even been paid for, but which was never

furnished. The lines are entitled:

|

"FOLLOWED BY ANOTHER."

"O woful impotence of weak resolve,

Recorded rashly to the writer's shame!

Days pass away, and Time's large orbs revolve,

And every day beholds me still the same;

Till oft-neglected purpose loses aim,

And hope becomes a flat unheeded lie,

And conscience, weary with the work of blame,

In seeming slumber droops her wistful eye,

As if she would resign her unregarded ministry." |

It only remains to note the death of this poor fellow-being.

It occurred on the 6th of January, 1849, when in his fifty-third

year. "He died the death of a strong man, his bodily frame

being of the finest construction, and capable of great endurance."

The following incident relative to Wordsworth is related in the

biography by Hartley Coleridge's brother:—

"The day following Hartley's

death, Wordsworth walked over with me to Grasmere, to the

churchyard,—a plain enclosure of the olden time, surrounding the old

village church, in which lay the remains of his wife's sister, his

nephew, and his beloved daughter. Here, having desired the

sexton to measure out the ground for his own and Mrs. Wordsworth's

grave, he bade him measure out the space of a third grave, for my

brother, immediately beyond.

"'When I lifted up my eyes from my daughter's grave,' he

exclaimed, 'he was standing there!' pointing to the spot where my

brother had stood on the sorrowful occasion to which he alluded.

Then, turning to the sexton, he said, 'Keep the ground for us,—we

are old people, and it cannot be for long.'

"In the grave thus marked out my brother's remains were laid

on the following Thursday, and in little more than a twelvemonth his

venerable and venerated friend was brought to occupy his own.

They lie in the southeast angle of the churchyard, not far from a

group of trees, with the little beck, that feeds the lake with its

clear water, murmuring by their side. Around them are the

quiet mountains. It was a winter's day when my brother was

carried to his last home, cold, but fine, as I noted at the time,

with a few slight scuds of sleet and gleams of sunshine, one of

which greeted us as we entered Grasmere, and another smiled brightly

through the church window. May it rest upon his memory!"

We can add nothing to this. The recital is very

touching, and is done throughout with the extremest delicacy and

grace by his brother, who would lovingly palliate the errors of the

departed. He sleeps well by Wordsworth's side, Wordsworth

having been the model of all his poetry, and standing to him instead

of a father through the greater part of his unhappy life.

Hartley Coleridge's poetry reminds the reader of Wordsworth

in nearly every line, though it is Wordsworth diluted; and at its

best, the Lake poetry cannot much bear dilution. Excepting in

the sonnets which relate to his own personal unhappiness, the poems

sound like the echoes of other poets, rather than welling warm from

the writer's own heart. And though, in the personal sonnets

referred to, he paints his purposeless life and blighted career in

terse and poetic language, it were perhaps better that they had not

been written at all. His poems addressed to Childhood are

perhaps the most charming things in the collection. For poor

Hartley loved children, and they returned his love. He loved

women, too, but at a distance; and his despondency at his own want

of personal attractions for them is a frequent theme of his poetry.

The melancholy history of Hartley Coleridge is not without

its moral. It was perhaps his misfortune to be the son of a

poet, who gave little heed to the healthy training of his children.

The child's endowment of fancy, though a rare one, proved only a

source of unhappiness in after-life, having been cultivated, as it

was, to the entire disregard of those other practical qualities

which fit a man for useful intercourse with the world. Living

in a state of dreaminess and abstraction, his mind became unnerved,

and his manly powers fatally impaired. He indulged in poetic

thought rather as an effeminate luxury than as a means of

self-culture or a relaxation from the severer toils and duties of

life. He was, however, fully aware of the wrongness of his

course, as appears from his numerous melancholy plaints in stanzas

and sonnets. But he made no effort at self-help; he met

adversity and temptation half-way, and laid himself down at their

feet, a willing victim. Though we ought to be tolerant of the

frailties of genius, we cannot overlook its sins and follies, which

are but too often seized upon as excuses for excess by those who are

less gifted. We must bear in mind that high powers are

committed to man for noble uses,—that from him to whom much is given

much shall be required,—that however poetic may be a man's thoughts,

he is not thereby absolved from the observance of the practical

virtues of life, or from living soberly, purely, and religiously; on

the contrary, the man of high thinkings is expected to live thus

daily, and to make his life the practical record of his thoughts.

Though there were many things to love about Hartley Coleridge, we

trust his sad career may not be without its lesson and its warning

to others.

――――♦――――

DR. KITTO.

John Kitto (1804-54), English biblical scholar.

NOT long since,

we were attracted by the announcement in a second-hand book

catalogue, of "Essays and Letters, by Dr. Kitto, written in a

Workhouse." As one of the celebrities of the day, the

editor of the Pictorial Bible, the Cyclopædia of Biblical

Literature, and many other highly important works, which have

obtained an extensive circulation, and are greatly prized, we could

not but feel interested in this little book, and purchased it

accordingly. It has proved full of curious interest, and from

it we learned, that, besides having endured from an early age the

serious privation of hearing, the author has also suffered the lot

of poverty, and, by dint of gallant perseverance and manly courage,

he was enabled to rise above and triumph over both privations.

It is indeed true that Dr. Kitto's first book was "written in

a workhouse." And we must here tell the reader something of

his early history. The father of Dr. Kitto was a working mason

at Plymouth, whither he had been attracted by the demand for

labourers of all descriptions at that place, about the early part of

the present century. John Kitto was born there in 1804.

In his youth he received very little school education, though he

learned to read, and had already taken some interest in books, when

the serious accident occurred which deprived him of his hearing.

At that time his parents were in very distressed circumstances, and,

though little more than twelve years of age, the boy was employed by

his father to help him as a labourer, in carrying stones, mortar,

and such like. One day in February, 1817, when stepping from

the ladder to the roof of a house undergoing repair in Batter

Street, the little lad, with a load of slates on his head, lost his

balance, and, falling back, was precipitated from a height of

thirty-five feet into the paved court below!

Dr. Kitto has himself given a most vivid account of the

details of the accident in the interesting work by him, on "The Lost

Senses,—Deafness," some time since published by Charles Knight.

"Of what followed," says he,

"I know nothing. For one moment, indeed, I

awoke from that death-like state, and then found that my father,

attended by a crowd of people, was bearing me homeward in his arms;

but I had then no recollection of what had happened, and at once

relapsed into a state of unconsciousness.

"In this state I remained for a fortnight, as I afterwards

learned. These days were a blank in my life; I could never

bring any recollections to bear upon them; and when I awoke one

morning to consciousness, it was as from a night of sleep. I

saw that it was at least two hours later than my usual time of

rising, and marvelled that I had been suffered to sleep so late.

I attempted to spring up in bed, and was astonished to find that I

could not even move. The utter prostration of my strength

subdued all curiosity within me. I experienced no pain, but I

felt that I was weak; I saw that I was treated as an invalid, and

acquiesced in my condition, though some time passed—more time than

the reader would imagine—before I could piece together my broken

recollections, so as to comprehend it.

"I was very slow in learning that my hearing was entirely

gone. The unusual stillness of all things was grateful to

me in my utter exhaustion; and if, in this half-awakened state, a

thought of the matter entered my mind, I ascribed it to the unusual

care and success of my friends in preserving silence around me.

I saw them talking, indeed, to one another, and thought that, out of

regard to my feeble condition, they spoke in whispers, because I

heard them not. The truth was revealed to me in consequence of

my solicitude about a book [Kirby's Wonderful Magazine] which had

much interested me on the day of my fall. I asked for this

book with much earnestness, and was answered by signs which I could

not comprehend.

"'Why do you not speak?!' I cried; 'pray, let me have the

book.'

"This seemed to create some confusion; and at length someone,

more clever than the rest, hit upon the happy expedient of writing

upon a slate, that the book had been reclaimed by the owner, and

that I could not in my weak state be allowed to read.

"'But,' said I, in great astonishment, 'why do you write to

me, why not speak?! Speak, speak!'

"Those who stood around the bed exchanged significant looks

of concern, and the writer soon displayed upon his slate the awful

words, 'YOU ARE DEAF.'"

Various remedies were tried, but without avail. Some

serious organic injury had been done to the auditory nerve by the

fall, and hearing was never restored: poor Kitto remained

stone-deaf. The boy, thus thrown upon himself, devoted his

spare time—his time was now all spare time—to reading. Books

gradually became a source of interest to him, and he soon exhausted

the small stocks of his neighbours. Books were then much rarer

than now, and reading was regarded as an occult art, in which few

persons of the working class could venture to indulge.

The circumstances of Kitto's parents still continued very

poor. This, with other sources of domestic disquietude,

rendered his position for some years very unfortunate. At

length, in 1819, about two years from the date of his accident, on

an application for relief from the guardians of the poor of

Plymouth, young Kitto was taken from his parents and placed among

the boys of the workhouse. There he was instructed in the art

of shoemaking, with the view of enabling him thus to obtain his

livelihood. He was afterwards bound apprentice to a poor

shoemaker in the town, where his position was very miserable; so

much so, that an inquiry as to the apprentice's treatment was

instituted before the magistrates, the result of which was that they

discharged Kitto from his apprenticeship, and he was returned to the

workhouse, where he continued his shoemaking. He found a warm

friend in Mr. Bernard, the clerk to the guardians, and also in Mr.

Nugent, the master of the school. From these gentlemen he

obtained loans of books, mostly of a religious character.

He remained in the workhouse about four years; his deafness

condemned him to solitude; for, deprived of speech and hearing, he

had not the means of forming friends among his companions, such as

they were. At the same time, it is possible enough that his

isolation from the other occupants of the workhouse may have

preserved his purity, and encouraged him to cultivate his

intellectual powers to a greater extent than he might otherwise have

been disposed to do. Thrown almost exclusively upon his visual

perceptions, he enjoyed with an intensity of delight the beautiful

face of Nature,—the sun, the moon, the stars, and the glories of

earth. In after life he said:

"I must not refuse to acknowledge that, when I have

beheld the moon, 'walking in brightness,' my heart has been

'secretly enticed' into feelings having perhaps a nearer approach to

the old idolatries than I should like to ascertain. I mention

this because, at this distant day, I have no recollection of earlier

emotions connected with the beautiful than those of which the moon

was the object. How often, some two or three years after my

affliction, did I not wander forth upon the hills, for no other

purpose in the world than to enjoy and feed upon the emotions

connected with the sense of the beautiful in nature. It

gladdened me, it filled my heart, I knew not why or how, to view

'the great and wide sea,' the wooded mountain, and even the silent

town, under that pale radiance; and not less to follow the course of

the luminary over the clear sky, or to trace its shaded pathway

among and behind the clouds."

An exquisitely keen perception of the beautiful in trees was of

somewhat later development, as Plymouth, being by the sea-side, is

not favourable to the growth of oaks, and had nothing to boast of

but a few rows of good elms. Another great source of enjoyment

with him, at that early period, was to wander about the

print-sellers' and picture-framers' windows, and learn the pictures

by heart, watching anxiously from day to day for the cleaning out of

the windows, that he might enjoy the luxury of a new display of

prints and frontispieces. He scoured the whole neighbourhood

with this view, going over to Devonport, which he divided into

districts and visited periodically, for the purpose of exploring the

windows in each, with leisurely enjoyment at each visit.

A young man so peculiarly circumstanced, and with such

tastes, could not remain altogether overlooked; and he was so

fortunate as to attract the notice of two worthy gentlemen, who,

when he had reached the age of about twenty years, used every

exertion to befriend him. One of these was Mr. Harvey, a

member of the Society of Friends, well known as an accomplished

mathematician, who supplied young Kitto with books of a superior

quality to anything he had before had access to. Mr. Harvey,

when one day in a bookseller's shop, saw a lad of mean appearance

enter, and begin writing a communication to the master on a slip of

paper. On inquiry, he found him to be a deaf workhouse boy,

distinguished by his desire for reading and thirst for knowledge of

all kinds; and that he had come to borrow a book which the

bookseller had promised to lend him. Inquiries were made about

him, interest was excited in his behalf, and a subscription was

raised for his benefit. He was supplied with books, paper, and

pens, to enable him to pursue his literary occupations; and in a

short time, having secured the notice of Mr. Nettleton, one of the

proprietors of the Plymouth Journal, and also a guardian of

the poor, several of his productions appeared in the columns of that

journal. The case of the poor lad became the subject of

general conversation in the town; several gentlemen associated

themselves together as the guardians of the youth; after which Kitto

was removed from the workhouse, and obtained permission to read at

the public library. A selection of his writings, chiefly

written in the workhouse, was shortly afterwards published by

subscription, and the young man found himself in the fair way of

advancement. He made rapid progress in learning, acquiring a

knowledge of Hebrew and other languages, which he imparted to pupils

whom he shortly after obtained, the sons of a gentleman into whose

house he was taken as tutor. He read largely on all subjects,

but his early bias towards theological literature clung to him, and

he soon acquired an extensive and profound knowledge of scriptural

and sacred lore. At length he was enabled to turn his stores

of learning to rich account, in his Pictorial Bible and Cyclopaedia

of Biblical Literature, which many of our readers may have seen.

In his day, Dr. Kitto has also been an extensive traveller; having

been in Palestine, in Egypt, in the Morea, in Russia, and in many

countries of Europe.

"For many years," he says,

"I had no views towards literature beyond the

instruction and solace of my own mind; and under these views, and in

the absence of other mental stimulants, the pursuit of it eventually

became a passion which devoured all others. I take no merit

for the industry and application with which I pursued this

object,—none for the ingenious contrivances by which I sought to

shorten the hours of needful rest, that I might have the more time

for making myself acquainted with the minds of other men. The

reward was great and immediate, and I was only preferring the

gratification which seemed to me the highest. Nevertheless,

now that I am in fact another being, having but slight

connection—excepting in so far as 'the child is father to the

man'—with my former self; now that much has become a business which

was then simply a joy; and now that I am gotten old in experiences,

if not in years,—it does somewhat move me to look back upon that

poor and deaf boy, in his utter loneliness, devoting himself to

objects in which none around him could sympathize, and to pursuits

which none could even understand. There was a time—by far the

most dreary in that portion of my career—when an employment was

found for me, [it was when he was apprenticed to the shoemaker,] to

which I proceeded about six o'clock in the morning, and from which I

returned not until about ten at night. I murmured not at this,

for I knew that life had grosser duties than those to which I would

gladly have devoted all my hours; and I dreamed not that a life of

literary occupations might be within the reach of my hopes.

This was, however, a terrible time for me, as it left me so little

leisure for what had become my sole enjoyment, if not my sole good.

I submitted; I acquiesced; I tried hard to be happy; but it would

not do; my heart gave way, notwithstanding my manful struggles to

keep it up, and I was very thoroughly miserable. Twelve hours

I could have borne. I have tried it, and know that the leisure

which twelve hours might have left would have satisfied me; but

sixteen hours, and often eighteen, out of the

twenty-four, was more than I could bear. To come home weary

and sleepy, and then to have only for mental sustenance the moments

which, by self-imposed tortures, could be torn from needful rest,

was a sore trial; and now that I look back upon this time, the

amount of study which I did, under these circumstances, contrive to

get through, amazes and confounds me, notwithstanding that my habits

of application remain to this day strong and vigorous.

"In the state to which I have thus referred, I suffered much

wrong; and the fact that, young as I then was, my pen became the

instrument of redressing that wrong, and of ameliorating the more

afflictive part of my condition, was among the first circumstances

which revealed to me the secret of the strength which I had, unknown

to myself, acquired. The flood of light which then broke in

upon me not only gave distinctness of purpose to what had before

been little more than dark and uncertain gropings; but also, from

that time, the motive to my exertions became more mixed than it had

been. My ardour and perseverance were not lessened; and the

pure love of knowledge, for its own sake, would still have carried

me on; but other influences, the influences which supply the impulse

to most human pursuits, did supervene, and gave the sanction

of the judgment to the course which the instincts of mental

necessity had previously dictated. I had, in fact, learned the

secret, that knowledge is power; and if, as is said, all power is

sweet, then, surely, that power which knowledge gives is, of all

others, the sweetest."

In conclusion, we may add, that Dr. Kitto continued to lead a

happy and a useful life, cheered by the faces of children around his

table,—though, alas! he could not hear their voices. He

resided until his death, in 1854, in the beautiful environs of

London, that he might be within sight of old trees, without

which his heart could scarcely be satisfied. Indeed, with such

love and veneration did he regard them, that the felling of a noble

tree caused him the deepest emotion. But he delighted in the

faces of men, too, and nothing gave him greater delight than

to walk or drive through the crowded thoroughfares of the

metropolis. In this respect he resembled the amiable Charles

Lamb, to whom the crowd of Fleet Street was more delightful than all

the hills and of Westmoreland. "How often," said Dr. Kitto,

"at the end of a day's hard toil, have I thrown

myself into an omnibus, and gone into town, for no other purpose in

the world than to have a walk from Charing Cross to St. Paul's on

the one hand, or to the top of Regent Street on the other; or from

the top of Tottenham Court Road to the Post-Office. I know not

whether I liked this best in summer or winter. I could seldom

afford myself this indulgence but for one or two evenings a week,

when I could manage to bring my day's studies to a close an hour or

so earlier than usual. In summer there is daylight, and I

could better enjoy the picture-shops and the street incidents, and

might diverge so as to pass through Covent Garden, and luxuriate

among the finest fruits and most beautiful flowers in the world.

And in winter it might be doubted whether the glory of the shops,

lighted up with gas, was not a sufficient counterbalance for the

absence of daylight. Perhaps 'both are best,' as the children

say; and yield the same kind of grateful change as the alternation

of the seasons offers."

Thus, what we, who have our hearing entire, regard as a great

calamity, in Dr. Kitto ceased to be regarded as such. The

condition became natural to him, and his sweet temper and steady

habits of industry enabled him to pass through life honourably and

usefully. His life was a noble and valuable lesson to all

young men.

――――♦――――

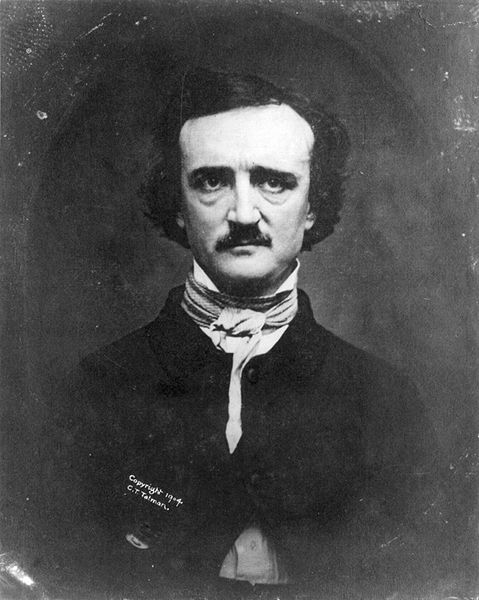

EDGAR ALLAN POE.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49): American writer, poet,

editor and literary critic.

A daguerreotype taken on 9th Nov. 1848. Picture

Wikipedia. [p.334]

RICHTER, writing

from Weimar, whither he had gone to see, eye to eye, the great men

with whose fame all Europe was ringing, said: "On the second day I

threw away my foolish prejudices about great authors: they are like

other people. Here, every one knows that they are like the

earth, which looks from a distance, from heaven, like a shining

moon; but when the foot is upon it, it is found to be made only

of Paris mud (boue de Paris)."

Alas! it is so. Those lofty gods whom we had worshipped

and bowed down before,—those gifted children of genius whose eyes

gazed eagerly into the unseen, and penetrated its depths far beyond

our ken,—when we approach them closer, and know them more

intimately, become stripped of their halo of glory. We find

that they are but men,—fallible, frail, and erring,—tempest-tossed

by passion and desire,—stumbling and halt, and often blind and

decrepit. We worship no more. The earth which, seen from

a distance, looks a beautiful moon, when the foot is on it, is but

rocks, clods, and "Paris mud"!

Sad indeed is the impression left on the mind by reading the

brief records of some of these unhappy children of genius: gifted,

but unhappy; loftily endowed, but fitful and capricious; with the

aspirations of an angel, but the low appetites of a brute; daringly

speculative, but grovellingly sensual;—such, in a few words, was the

life of Edgar Allan Poe: a being full of misery, but all beaten out

upon his own anvil; a man gifted as few are, but without faith or

devotion, and without any earnest purpose in life.

You have read his "Raven." You see the gloom and

despair of that unhappy youth's life written there. What a

dismal, tragic, remorseful transcript it is!—the croaking raven,

bird of ill omen, perched above its master's chamber-door,

responding with his doleful "Nevermore" to all his deep questions

and impatient feelings:—

|

"'Prophet,' said I, 'thing of evil!

Prophet still, if bird or devil!

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tost

thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted,

On this home by horror haunted,—tell me truly, I

implore,

Is there—is there balm in Gilead? Tell me, tell me, I

implore!

Quoth the raven,—'Nevermore!'

"'Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!' I

shrieked, upstarting;

Get thee back into the tempest, and the Night's

Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! quit the bust above

my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!'

Quoth the raven,—'Nevermore!'

"And the raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still

is sitting,

On the pallid bust of Pallas, just above my

chamber-door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamplight o'er him streaming throws his shadow

on the floor;

And my soul from out the shadow that lies floating on the floor,

Shall be lifted—nevermore!" |

By this light, read the following brief record of the poet's

blurred and blotted life.

Edgar Allan Poe was born at Baltimore, in 1811, of an old and

respectable family. His father was a lawyer, but having become

enamoured of an English actress, he married her, and followed her

profession for some years, until his death, which shortly followed.

Poe's mother died about the same time, and three children were left

destitute. But a wealthy gentleman, named Allan, who had no

children of his own, adopted Edgar, it was understood with the

intention of leaving him his heir. In 1816 Mr. Allan took the

boy to England with him, and placed him in a boarding-school at

Stoke Newington, near London, where he remained some four or five

years, under the Rev. Dr. Bransby, returning to America in 1822.

It will be obvious that the circumstances of Poe's early life

were very unfavourable to his healthy moral development.

Deprived of the blessings" of maternal nurture, without a home,

brought up among strangers, there is little cause to wonder at the

subsequent heartlessness towards others which he displayed, and the

excesses in which he indulged. Returned to America, he entered

the University of Charlottesville, in Virginia, in 1825.

Unfortunately, the students of that University were then

distinguished for their dissoluteness and their excesses in many

ways; and Edgar Poe was one of the most reckless of his class.

Although his talents were such as to enable him to master with ease

the most difficult studies, and to take the highest honours of his

year, his habits of gambling, intemperance, and general dissipation

were such as to cause his expulsion from the University.

Mr. Allan, his benefactor, had made him a liberal allowance;

but Poe nevertheless ran deeply into debt, chiefly to his gambling

friends; and when his drafts were presented to Mr. Allan for

payment, be declined to honour them; on which Poe wrote him an

abusive letter, left his house, abandoned his half-formed plans of

life, and suddenly left the country to take part as a volunteer,

like Byron, in the Greek Revolution. But he never reached

Greece. Whither he wandered, Heaven knows. Nothing was

heard of him until, after the lapse of a year, the American Minister

at St. Petersburgh was one morning summoned to save him from the

penalties incurred in a drunken debauch over night. Through

the Minister's intercession, he was set at liberty and enabled to

return to the United States.

His friend, Mr. Allan, was still willing to assist him, and,

at his request, Poe was entered as scholar in the Military Academy

at West Point; but again his dissipated habits displayed themselves.

He negleglted his duties and disobeyed orders, on which he was

cashiered, and once more returned to Mr. Allan's house, who was

still ready to receive him and treat him as a son. But a

circumstance shortly occurred which finally broke the connection

between the two. Mr. Allan married a second time, and the lady

was considerably his junior. Poe quarrelled with her, and, it

is said, ridiculed Allan. The lady's friends have averred that

the real cause of the rupture was, that Poe made disgraceful

overtures to the young wife, which throws another dark stain upon

his character. Whatever the real cause may have been, certain

it is, that he was now expelled from his patron's house in anger;

and when Mr. Allan died, some years after, he left nothing to Poe.

The young man had in the mean while published a small volume

of poetry, when he was not more than eighteen years of age.

This was very favourably received, and a little perseverance might

have enabled him to maintain himself creditably as a literary man.

But in one of his hasty and reckless fits, he enlisted as a private

soldier. He was recognized by some of his old fellow-students

at West Point, and they made efforts to obtain him a commission,

which promised to be successful; but, fitful in everything, before

the result of their kind application could be known, he deserted!

We next find Poe a successful competitor for certain prizes

offered by the proprietor of the Baltimore Visitor for the

best story and the best poem. Poe competed for both, and

gained both. The author was sent for, and made his appearance

in due time. He was in a state of the utmost destitution,

pale, ghastly, and filthy. His seedy frock-coat, buttoned up

to his throat, concealed the absence of a shirt, and his dilapidated

boots disclosed his want of stockings. Mr. Kennedy, the author

of "Horse-shoe Robinson," who was the adjudicator of the prize, took

an immediate interest in the young man, then only twenty-two years

old; and he accompanied him to a clothing store, where he provided

him with a respectable suit, with changes of linen, and, after

taking a bath, Poe once more appeared in the restored guise of a

gentleman.

Mr. Kennedy further used his influence in obtaining for Poe

some literary employment, and he was shortly engaged as joint editor

of the Southern Literary Messenger, published at Richmond.

He was now a literary man, living by his pen. The literary

profession is an honourable one, even noble, inasmuch as it is

identified with intellectual culture and high manly gifts. The

literary man exercises much power in the world. He helps to

form the opinions of other men; indeed, he makes public opinion.

All other powers have in modern times become weaker, while this has