|

HUGH MILLER

|

Hugh Miller (1802-56): Scottish stone mason, self-taught

geologist, writer and newspaper editor.

A Calotype by David Octavius Hill and

Robert Adamson, 1843. Picture Wikipedia. |

MEN may learn much that is

good from each other's lives,—especially from good men's lives. Men

who live in our daily sight, as well as men who have lived before us, and

handed down illustrious examples for our imitation, are the most valuable

practical teachers. For it is not mere literature that makes men,—it

is real, practical life, that chiefly moulds our nature, enables us to

work out our own education, and to build up our own character.

HUGH

MILLER has very strikingly worked out

this idea in his admirable autobiography, entitled, "My Schools and

Schoolmasters." It is extremely interesting, even fascinating, as a book;

but it is more than an ordinary book,—it might almost be called an

institution. It is the history of the formation of a truly noble and

independent character in the humblest condition of life,—the condition in

which a large mass of the people of this country are born and brought up;

and it teaches all, but especially poor men, what it is in the power of

each to accomplish for himself. The life of Hugh Miller is full of

lessons of self-help and self-respect, and shows the efficacy of these in

working out for a man an honourable competence and a solid reputation. It

may not be that every man has the thew and sinew, the large brain and

heart, of a Hugh Miller,—for there is much in what we may call the breed

of a man, the defect of which no mere educational advantages can supply;

but every man can at least do much, by the help of such examples as his,

to elevate himself, and build up his moral and intellectual character on a

solid foundation.

We have spoken of the breed of a man. In Hugh Miller we have an

embodiment of that most vigorous and energetic element of English national

life,—the Norwegian and Danish. In times long, long ago, the daring and

desperate pirates of these nations swarmed along the eastern coasts. In

England they were resisted by force of arms, for the prize of England's

crown was a rich one; yet, by dint of numbers, valour, and bravery, they

made good their footing in England, and even governed the eastern part of

it by their own kings until the time of Alfred the Great. And to this day

the Danish element amongst the population of the east and northeast of

England is by far the prevailing one. But in Scotland it was different.

They never reigned there; but they settled and planted all the eastern

coasts. The land was poor and thinly peopled; and the Scottish kings and

chiefs were too weak—generally too much occupied by intestine broils—to

molest or dispossess them. Then these Danes and Norwegians led a

seafaring life, were sailors and fishermen, which the native Scots were

not. So they settled down in all the bays and bights along the coast of

Scotland, and took entire possession of the Orkneys, Shetland, and Western

Isles, the Shetlands having been held by the crown of Denmark down to a

comparatively recent period. They never amalgamated with the Scotch

Highlanders; and to this day they speak a different language, and follow

different pursuits. The Highlander was a hunter, a herdsman, a warrior,

and fished in the fresh waters only. The descendants of the Norwegians,

or the Lowlanders, as they came to be called, followed the sea, fished in

salt waters, cultivated the soil, and engaged in trade and commerce.

Hence the marked difference between the population of the town of

Cromarty—where Hugh Miller was born, in 1802—and the population only a few

miles inland; the townspeople speaking Lowland Scotch, and being dependent

for their subsistence mainly on the sea,—the others speaking Gaelic, and

living solely, upon the land.

These Norwegian colonists of Cromarty held in their blood the very same

piratical propensities which characterized their forefathers who followed

the Vikings. Hugh Miller first saw the light in a long, low-built house,

built by his great-grandfather, John Feddes, "one of the last of the

buccaneers;" this cottage having been built, as Hugh Miller himself says

he has every reason to believe, with "Spanish gold." All his ancestors

were sailors and seafaring men; when boys they had taken to the water as

naturally as ducklings. Traditions of adventures by sea were rife in the

family. Of his grand-uncles, one had sailed round the world with Anson,

had assisted in burning Paeta, and in boarding the Manilla galleon;

another, a handsome and powerful man, perished at sea in a storm; and his

grandfather was dashed overboard by the jib-boom of his little vessel when

entering the Cromarty Firth, and never rose again. The son of this last,

Hugh Miller's father, was sent into the country by his mother to work upon

a farm, thus to rescue him, if possible, from the hereditary fate of the

family. But it was of no use. The propensity for the salt water, the

very instinct of the breed, was too powerful within him. He left the

farm, went to sea, became a man-of-war's man, was in the battle with the

Dutch off the Dogger Bank, sailed all over the world, then took "French

leave" of the royal navy, returned to Cromarty with money enough to buy a

sloop and engage in trade on his own account. But this vessel was one

stormy night knocked to pieces on the bar of Findhorn, the master and his

men escaping with difficulty; then another vessel was fitted out by him,

by the help of his friends, and in this he was trading from place to place

when Hugh Miller was born.

What a vivid picture of sea-life, as seen from the shore at least, do

we obtain from the early chapters of Miller's life! "I retain," says he,

"a vivid recollection of the joy which used to light up the household on

my father's arrival, and how I learned to distinguish for myself his sloop

when in the offing, by the two slim stripes of white that ran along her

sides, and her two square topsails." But a terrible calamity—though an

ordinary one in sea-life—suddenly plunged the sailor's family in grief;

and he, too, was gathered to the same grave in which so many of his

ancestors lay,—the deep ocean. A terrible storm overtook his vessel near

Peterhead; numbers of ships were lost along the coast; vessel after vessel

came ashore, and the beach was strewn with wrecks and dead bodies, but no

remnant of either the ship or bodies of Miller and his crew was ever cast

up. It was supposed that the little sloop, heavily laden, and labouring

in a mountainous sea, must have started a plank and foundered. Hugh

Miller was but a child at the time, having only completed his fifth year.

The following remarkable "appearance," very much in Mrs. Crowe's way, made

a strong impression upon him at the time. The house-door had blown open,

in the gray of evening, and the boy was sent by his mother to shut it.

"Day had not wholly disappeared, but it was fast posting on to night,

and a gray haze spread a neutral tint of dimness over every more distant

object, but left the nearer ones comparatively distinct, when I saw at the

open door, within less than a yard of my breast, as plainly as ever I saw

anything, a dissevered hand and arm stretched towards me. Hand and arm

were apparently those of a female: they bore a livid and sodden

appearance; and directly fronting me, where the body ought to have been,

there was only blank, transparent space, through which I could see the dim

forms of the objects beyond. I was fearfully startled, and ran shrieking

to my mother, telling what I had seen; and the house-girl, whom she next

sent to shut the door, affected by my terror, also returned frightened,

and said that she, too, had seen the woman's hand; which, however, did not

seem to be the case. And finally, my mother going to the door, saw

nothing, though she appeared much impressed by the extremeness of my

terror, and the minuteness of my description. communicate the story as it

lies fixed in my memory, without attempting to explain it: its coincidence

with the probable time of my father's death, seems at least curious."

The little boy longed for his father's return, and continued to gaze

across the deep, watching for the sloop with its two stripes of white

along the sides. Every morning he went wandering about the little

harbour, to examine the vessels which had come in during the night; and he

continued to look out across the Moray Forth long after anybody else had

ceased to hope. But months and years passed, and the white stripes and

square topsails of his father's sloop he never saw again. The boy was

the son of a sailor's widow, and so grew up, in sight of the sea, and with

the same love of it that characterized his father. But he was sent to

school; first to a dame school, where he learnt his letters; he then

worked his way through the Catechism, the Proverbs, and the New Testament

and emerged into the golden region of "Sinbad the Sailor," "Jack the

Giant-Killer," "Beauty and the Beast," and "Aladdin and the Wonderful

Lamp." Other books followed,—the Pilgrim's Progress, Cook's and Anson's

Voyages, and Blind Harry the Rhymer's History of Wallace; which first

awoke within him a strong feeling of Scottish patriotism. And thus his

childhood grew, on proper child-like nourishment. His uncles were men of

solid sense and sound judgment, though uncultured by scholastic

education. One was a local antiquary, by trade a working harness-maker;

the other was of a strong religious turn: he was a working cartwright, and

in early life had been a sailor, engaged in nearly all Nelson's famous

battles. The examples and the conversation of these men were for the

growing boy worth any quantity of school primers: he learnt from them far

more than mere books could teach him.

But his school education was not neglected either.

From the dame's school he was transferred to the town's grammar school,

where, amidst about one hundred and fifty other boys and girls, he

received his real school education. But it did not amount to much.

There, however, the boy learnt life,—to hold his own,—to try his powers

with other boys,—physically and morally, as well as scholastically.

The school brought out the stuff that was in him in many ways, but the

mere book-learning was about the least part of the instruction.

The school-house looked out on the beach, fronting the opening of the

Frith, and not a boat or a ship could pass in or out of the harbour of

Cromarty without the boys seeing it. They knew the rig of every craft,

and could draw them on their slates. Boats unloaded their glittering

cargoes on the beach, where the process of gutting afterwards went busily

on; and to add to the bustle, there was a large killing-place for pigs not

thirty yards from the school door, "where from eighty to a hundred pigs

used sometimes to die for the general good in a single day; and it was a

great matter to hear, at occasional intervals, the roar of death rising

high over the general murmur within, or to be told by some comrade,

returned from his five minutes' leave of absence, that a hero of a pig had

taken three blows of a hatchet ere it fell, and that, even after its

subjection to the sticking process, it had got hold of Jock Keddie's hand

in its mouth, and almost smashed his thumb." Certainly it is not in every

grammar-school that such lessons as these are taught.

Miller was put to Latin, but made little progress in it,—his master

had no method, and the boy was too fond of telling stories to his

schoolfellows in school hours to make much progress. Cock-fighting was a

school practice in those days, apparently the master having a perquisite

of two-pence for every cock that was entered by the boys on the days of the

yearly fight. But Miller had no love for this sport, although he paid his

entry money with the rest. In the mean time his miscellaneous reading

extended, and he gathered pickings of odd knowledge from all sorts of odd

quarters,— from workmen, carpenters, fishermen and sailors, old women,

and, above all, from the old boulders strewed along the shores of the

Cromarty Frith. With a big hammer, which had belonged to his

great-grandfather, John Feddes, the buccaneer, the boy went about chipping

the stones, and thus early accumulating specimens of mica, porphyry,

garnet, and such like, exhibiting them to his uncle Alexander, and other

admiring relations. Often, too, he had a day in woods to visit his

uncle, when working as a sawyer,—his trade of cartwright having, failed.

And there, too, the boy's attention was excited by the peculiar geological

curiosities which lay in his way. While searching among the stones and

rocks on the beach, he was sometimes asked, in humble irony, by the farm

servants who came to load their carts with sea-weed, whether he "was

gettin' siller in the stanes," but was so unlucky as never to be able to

answer their question in the affirmative. Uncle Sandy seems to have been

a close observer of nature, and in his humble way had his theories of

ancient sea beaches, the flood, and the formation of the world, which he

duly imparted to the wondering youth. Together they explored caves,

roamed the beach for crabs and lobsters, whose habits Uncle Sandy could

well describe; he also knew all about moths and butterflies, spiders, and

bees,—in short, was a born natural-history man, so that the boy regarded

him in the light of a professor, and, doubtless, thus early obtained from

him the bias toward his future studies.

|

|

|

A Calotype by Hill and Adamson (ca.

1843-47). |

There was the usual number of hair-breadth

escapes in Miller's boy-life. One of them, when he and a companion had

got cooped up in a sea cave, and could not return because of the tide,

reminds us of the exciting scene described in Scott's Antiquary. There

were school-boy tricks, and schoolboy rambles, mischief-making in

companionship with other boys, of whom he was often the leader. Left very

much to himself, he was becoming a big, wild, insubordinate boy; and it

became obvious that the time was now come when Hugh Miller must enter that

world-wide school in which toil and hardship are the severe but noble

masters. After a severe fight and wrestling-match with his schoolmaster,

he left school, avenging himself for his defeat by penning and sending by

the teacher, that very night, a copy of satiric verses, entitled "The

Pedagogue," which occasioned a good deal of merriment in the place.

His boyhood over, and his school training ended, Hugh Miller must now

face the world of toil. His uncles were most anxious that he should

become a minister; and were even willing to pay his college expenses,

though the labour of their hands formed their only wealth. The youth,

however, had conscientious objections: he did not feel called to the

work; and the uncles, confessing that he was right, gave up their point.

Hugh was accordingly apprenticed to the trade of his choice,—that of a

working stone-mason; and he began his labouring career in a quarry

looking out upon the Cromarty Firth. This quarry proved one of his best

schools. The remarkable geological formations which it displayed awakened

his curiosity. The bar of deep-red stone beneath, and the bar of pale-red

clay above, were noted by the young quarryman, who, even in such

unpromising subjects, found matter for observation and reflection. Where

other men saw nothing, he detected analogies, differences, and

peculiarities, which set him a-thinking. He simply kept his eyes and his

mind open; was sober, diligent, and persevering; and this was the secret

of his intellectual growth.

Hugh Miller takes a cheerful view of the lot of labour. While others

groan because they have to work hard for their bread, he says that work is

full of pleasure, of profit, and of materials for self-improvement. He

holds that honest labour is the best of all teachers, and that the school

of toil is the best and noblest of all schools, save only the Christian

one,—a school in which the ability of being useful is imparted, and the

spirit of independence communicated, and the habit of persevering effort

acquired. He is even of opinion that the training of the mechanic, by the

exercise which it gives to his observant faculties, from his daily

dealings with things actual and practical, and the close experience of

life which he invariably acquires, is more favourable to his growth as a

Man, emphatically speaking, than the training which is afforded by any

other condition of life. And the array of great names which he cites in

support of his statement is certainly a large one. Nor is the condition

of the average well-paid operative at all so dolorous, according to Hugh

Miller, as many modern writers would have it to be. "I worked as an

operative mason," says he, "for fifteen years,—no inconsiderable portion

of the more active part of a man's life; but the time was not altogether

lost. I enjoyed in those years fully the average amount of happiness, and

learned to know more of the Scottish people than is generally known. Let

me add, that from the close of the first year in which I wrought as a

journeyman, until I took final leave of the mallet and chisel, I never

knew what it was to want a shilling; that my two uncles, my grandfather,

and the mason with whom I served my apprenticeship—all working-men—had had

a similar experience; and that it was the experience of my father also. I

cannot doubt that deserving mechanics may, in exceptional cases, be

exposed to want; but I can as little doubt that the cases are exceptional,

and that much of the suffering of the class is a consequence either of

improvidence on the part of the completely skilled, or of a course of

trifling during the term of apprenticeship,—quite as common as trifling at

school,—that always lands those who indulge in it in the hapless position

of the inferior workman."

There is much honest truth in this observation. At the same time, it

is clear that the circumstances under which Hugh Miller was brought up and

educated are not enjoyed by all workmen,—are, indeed, experienced by

comparatively few. In the first place, his parentage was good, his father

and mother were a self-helping, honest, intelligent pair, in humble

circumstances, but yet comparatively comfortable. Thus his early

education was not neglected. His relations were sober, industrious, and

"God-fearing," as they say in the north. His uncles were not his least

notable instructors. One of them was a close observer of nature, and in

some sort a scientific man, possessed of a small but good library of

books. Then Hugh Miller's own constitution was happily trained. As one

of his companions once said to him, "Ah, Miller, you have stamina in you,

and will force your way; but I want strength; the world will never hear

of me." It is the stamina which Hugh Miller possessed by nature, that

were born in him, and were carefully nurtured by his parents, that enabled

him as a working-man to rise, while thousands would have sunk or merely

plodded on through life in the humble station in which they were born.

And this difference in stamina and other circumstances is not sufficiently

taken into account by Hugh Miller in the course of the interesting, and,

on the whole, exceedingly profitable remarks, which he makes in his

autobiography on the condition of the labouring poor.

We can afford, in our brief space, to give only a very rapid outline

of Hugh Miller's fifteen years' life as a workman. He worked away in the

quarry for some time, losing many of his finger-nails by bruises and

accidents, growing fast, but gradually growing stronger, and obtaining a

fair knowledge of his craft as a stone-hewer. He was early subjected to

the temptation which besets most young workmen,—that of drink. But he

resisted it bravely. His own account of it is worthy of extract:—

"When overwrought, and in my depressed moods, I learned to regard the

ardent spirits of the dram-shop as high luxuries; they gave lightness and

energy to both body and mind, and substituted for a state of dulness and

gloom one of exhilaration and enjoyment. Usquebhae was simply happiness

doled out by the glass, and sold by the gill. The drinking usages of the

profession in which I laboured were at this time many; when a foundation

was laid, the workmen were treated to drink; they were treated to drink

when the walls were levelled for laying the joists; they were treated to

drink when the building was finished; they were treated to drink when an

apprentice joined the squad; treated to drink when his 'apron was washed;'

treated to drink when his ' time was out;' and occasionally they learnt to

treat one another to drink. In laying down the foundation stone of one of

the larger houses built this year by Uncle David and his partner, the

workmen had a royal 'founding-pint,' and two whole glasses of the whiskey

came to my share. A full-grown man would not have deemed a gill of

usquebhae an overdose, but it was considerably too much for me; and when

the party broke up, and I got home to my books, I found, as I opened the

pages of a favourite author, the letters dancing before my eyes, and that

I could no longer master the sense. I have the volume at present before

me, a small edition of the Essays of Bacon, a good deal worn at the

corners by the friction of the pocket, for of Bacon I never tired. The

condition into which I had brought myself was, I felt, one of

degradation. I had sunk, by my own act, for the time, to a lower level of

intelligence than that on which it was my privilege to be placed; and

though the state could have been no very favourable one for forming a

resolution, I in that hour determined that I should never again

sacrifice my capacity of intellectual enjoyment to a drinking usage; and,

with God's help, I was enabled to hold my determination."

A young working mason, reading Bacon's Essays in his by-hours, must

certainly be regarded as a remarkable man; but not less remarkable is the

exhibition of moral energy and noble self-denial in the instance we have

cited.

It was while working as a mason's apprentice, that the lower Old Red

Sandstone along the Bay of Cromarty presented itself to his notice; and

his curiosity was excited and kept alive by the infinite organic remains,

principally of old and extinct species of fishes, ferns, and ammonites,

which lay revealed along the coasts by the washings of waves, or were

exposed by the stroke of his mason's hammer. He never lost sight of this

subject; went on accumulating observations and comparing formations, until

at length, when no longer a working mason, many years afterwards, he gave

to the world his highly interesting work on the Old Red Sandstone, which

at once established his reputation as an accomplished scientific

geologist. But this work was the fruit of long years of patient

observation and research. As he modestly states in his autobiography,

"the only merit to which I lay claim in the case is that of patient

research, —a merit in which whoever wills may rival or surpass me; and

this humble faculty of patience, when rightly developed, may lead to more

extraordinary developments of idea than even genius itself." And he adds

how he deciphered the divine ideas in the mechanism and framework of

creatures in the second stage of vertebrate existence.

But it was long before Hugh Miller accumulated his extensive

geological observations, and acquired that self-culture which enabled him

to shape them into proper form. He went on diligently working at his

trade, but always observing and always reflecting. He says he could not

avoid being an observer; and that the necessity which made him a mason,

made him also a geologist. In the winter months, during which mason-work

is generally superseded in country places, he occupied his time with

reading, sometimes with visiting country friends,—persons of an

intelligent caste,—and often he strolled away amongst old Scandinavian

ruins and Pictish forts, speculating about their origin and history. He

made good use of his leisure. And when spring came round again, he would

set out into the Highlands, to work at building and hewing jobs with a

squad of other masons,—working hard, and living chiefly on oatmeal brose.

Some of the descriptions given by him of life in the remote Highland

districts are extremely graphic and picturesque, and have all the charm of

entire novelty. The kind of accommodation which he experienced may be

inferred from the observation made by a Highland laird to his uncle James,

as to the use of a crazy old building left standing beside a group of neat

modern offices. "He found it of great convenience," he said, "every time

his speculations brought a drove of pigs, or a squad of masons, that

way." This sort of life and its surrounding circumstances were not of a

poetical cast; yet the youth was now about the poetizing age, and during

his solitary rambles after his day's work, by the banks of the Conon, he

meditated poetry, and began to make verses. He would sometimes write

them out upon his mason's kit, while the rain was dropping through the

roof of the apartment upon the paper on which he wrote. It was a rough

life of poetic musing, yet he always contrived to mix up a high degree of

intellectual exercise and enjoyment with whatever manual labour he was

employed upon; and this, after all, is one of the secrets of a happy

life. While observing scenery and natural history, he also seems to have

very closely observed the characters of his fellow workmen, and he gives

us vivid and life-like portraits of some of the more remarkable of them in

his Autobiography. There were some rough and occasionally very wicked

fellows among his fellow-workmen, but he had strength of character, and

sufficient inbred sound principle, to withstand their contamination. He

was also proud,—and pride in its proper place is an excellent

thing,—particularly that sort of pride which makes a man revolt from doing

a mean action, or anything which would bring discredit on the, family.

This is the sort of true nobility which serves poor men in good stead

sometimes, and it certainly served Hugh Miller well.

His apprenticeship ended, he "took jobs" for himself,—built a cottage

for his Aunt Jenny, which still stands, and after that went out working as

journeyman-mason. In his spare hours, he was improving himself by the

study of practical geometry, and made none the worse a mason on that

account. While engaged in helping to build a mansion on the western coast

of Ross-shire, he extended his geological and botanical observations,

noting all that was remarkable in the formation of the district. He also

drew his inferences from the condition of the people,—being very much

struck, above other things, with the remarkably contented state of the

Celtic population, although living in filth and misery. On this he

shrewdly observes: "It was one of the palpable characteristics of our

Scottish Highlanders, for at least the first thirty years of the century,

that they were contented enough, as a people; to find more to pity than to

envy in the condition of their Lowland neighbours; and I remember that at

this time, and for years after, I used to deem the trait a good one. I

have now, however, my doubts on the subject, and am not quite sure whether

a content so general as to be national may not, in certain circumstances,

be rather a vice than a virtue. It is certainly no virtue, when it has

the effect of arresting either individuals or peoples in their course of

development; and is perilously allied to great suffering, when the men who

exemplify it are so thoroughly happy amid the mediocrities of the present

that they fail to make provision for the contingencies of the future."

Trade becoming slack in the North, Hugh Miller took ship for

Edinburgh, where building was going briskly on (in 1824), to seek for

employment there as a stone-hewer. He succeeded, and lived as a workman

at Niddry, in the neighbourhood of the city, for some time; pursuing at

the same time his geological observations in a new field, Niddry being

located on the carboniferous system. Here also he met with an entirely

new class of men,—the colliers,—many of whom, strange to say, had been

born slaves; the manumission of the Scotch colliers having been

effected in comparatively modern times,—as late as the year 1775! So

that, after all, Scotland is not so very far ahead of the serfdom of

Russia.

Returning to the North again, Miller next began business for himself

in a small way, as a hewer of tombstones for the good folks of Cromarty.

This change of employment was necessary, in consequence of the hewer's

disease, caused by inhaling stone-dust, which settles in the lungs, and

generally leads to rapid consumption, afflicting him with its premonitory

symptoms. The strength of his constitution happily enabled him to throw

off the malady, but his lungs never fairly recovered their former vigour.

Work not being very plentiful, he wrote poems, some of which appeared in

the newspapers; and in course of time a small collection of these pieces

was published by subscription. He very soon, however, gave up poetry

writing, finding that his humble accomplishment of verse was too narrow to

contain his thinking; so next time he wrote a book it was in prose, and

vigorous prose too, far better than his verse. But Miller had meanwhile

been doing what was better than either cutting tombstones or writing

poetry: he had been building up his character, and thereby securing the

respect of all who knew him. So that, when a branch of the Commercial Bank

was opened in Cromarty, and the manager cast about him to make selection

of an accountant, whom should he pitch upon but Hugh Miller, the

stone-mason? This was certainly a most extraordinary selection; but why

was it made? Simply because of the excellence of the man's character. He

had proved himself a true and a thoroughly excellent and trustworthy man

in a humble, capacity of life; and the inference was, that he would carry

the same principles of conduct into another and higher sphere of action.

Hugh Miller hesitated to accept the office, having but little knowledge of

accounts, and no experience in book-keeping; but the manager knew his

pluck and determined perseverance in mastering whatever he undertook;

above all, he had confidence in his character, and he would not take a

denial. So Hugh Miller was sent to Edinburgh to learn his new business at

the head bank.

Throughout life, Miller seems to have invariably put his conscience

into his work. Speaking of the old man with whom he served his

apprenticeship as a mason, he says: "He made conscience of every stone

he laid. It was remarked in the place, that the walls built by Uncle

David never bulged nor fell; and no apprentice nor journeyman of his was

permitted, on any plea, to make 'slight work.'" And one of his own

Uncle James's instructions to him on one occasion was, "In all your

dealings, give your neighbour the cast of the baulk,—'good measure,

heaped up and running over,'—and you will not lose by it in the end."

These lessons were worth far more than what is often taught in schools,

and Hugh Miller seems to have framed his own conduct in life on the

excellent moral teaching which they conveyed. Speaking of his own career

as a workman, when on the eve of quitting it, he says: "I do think I acted

up to my uncle's maxim; and that, without injuring my brother workmen by

lowering their prices. I never yet charged an employer for a piece of

work that, fairly measured and valued, would not be rated at a slightly

higher sum than that at which it stood in my account."

Although he gained some fame in his locality by his poems, and still

more by his "Letters on the Herring Fisheries of Scotland," he was not, as

many self-raised men are, spoilt by the praise which his works called

forth. "There is," he says, "no more fatal error into which a working-man

of a literary turn can fall, than the mistake of deeming himself too good

for his humble employments; and yet it is a mistake as common as it is

fatal. I had already seen several poor wrecked mechanics, who, believing

themselves to be poets, and regarding the manual occupation by which they

could alone live in independence as beneath them, had become in

consequence little better than mendicants,—too good to work for their

bread, but not too good virtually to beg it; and looking upon them as

beacons of warning, I determined that, with God's help, I should give

their error a wide offing, and never associate the idea of meanness with

an honest calling, or deem myself too good to be independent." Full of

this manly and robust spirit, Hugh Miller pursued his career of

stone-hewing by day, and prose composition when the day's work was done,

until he entered upon his new vocation of banker's accountant. He showed

his self-denial, too, in waiting for a wife until he could afford to keep

one in respectable comfort,—his engagement lasting over five years,

before he was in a position to fulfil his promise. And then he married,

wisely and happily.

At Edinburgh, by dint of perseverance and application, Mr. Miller

shortly mastered his new business, and then returned to Cromarty, where he

was installed in office. His "Scenes and Legends of the North of

Scotland" were published about the same time, and were well received; and

in his leisure hours he proceeded to prepare his most important work, on

"The Old Red Sandstone." He also contributed to the "Border Tales," and

other periodicals. The Free-Church movement drew him out as a polemical

writer: and his Letter to Lord Brougham on the Scotch Church Controversy

excited so much attention, that the leaders of the movement in Edinburgh

invited him to undertake the editing of the Witness newspaper, the organ

of the Free-Church party. He accepted the invitation, and continued to

hold the editorship until his death, in 1856.

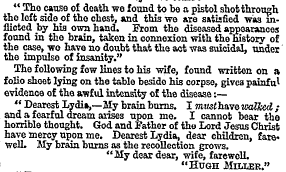

The circumstances connected with his decease were of a most

distressing character. On entering his room one morning, he was found

lying dead, shot through the body, and under circumstances which left no

doubt that he had died by his own hand. He had for some time been closely

applying himself to the completion of his "Testimony of the Rocks,"

without rest or relaxation, or due attention to his physical health.

Under these circumstances, overwork of the brain speedily began to tell

upon him. He could not sleep,—if he lay down and dozed, it was only to

wake in a start, his head filled with imaginary horrors; and in one of

these fits of his disease he put an end to his life;—a warning to all

brainworkers, that the powers of the human constitution may be strained

until they break, and that even the best and strongest mind cannot

dispense with the due observance of the laws which regulate the physical

constitution of man.

|

|

|

Extract from Miller's obituary in

THE TIMES, 29 Dec 1856. |

――――♦――――

RICHARD COBDEN.

|

|

|

Richard Cobden (1804-65),

Manufacturer, Radical and Liberal statesman. |

RICHARD

COBDEN was born on the 3d of June, 1804, at

Dunford farm-house, near Medhurst, a village in Sussex, far from the

noise and bustle of towns. When a little boy, he tended his father's

sheep in the fields, and helped to do the usual work of the farm as he

grew older. His grandfather, who was head bailiff of Medhurst, carried

on business as a maltster there, and he is still spoken of by the old

people in the village as "Maltster Cobden." The family must have been

long settled in the neighbourhood, "Cobden's Lane" and "Cobden's Farm"

being still remembered places. Indeed, many of these old English farmers

have a very ancient ancestry,—older than the Norman Conquest; for when

the Normans came, the Cobdens, and such as they, were already settled

cultivators of the soil. Richard Cobden, however, cares little about

ancestry, and thinks mainly of the duties which each man owes to the

generation in which he lives, and of the manner in which he performs

them.

Maltster Cobden did not succeed in life; and his son, Richard's father,

eventually gave up farming, when the old house at Dunford was pulled

down, and the family left the neighbourhood. Richard had meanwhile

acquired the very slenderest possible rudiments of education, when he

was sent to be employed as a boy in a London warehouse extensively

engaged in the cotton-print trade. He there drudged his way upward from

the lowest point, training himself in habits of industry, as well as in

self-culture. He was very diligent, very observant, and very well

conducted. In a properly-managed house of business, promotion in such

cases follows as a matter of course; and Richard Cobden was gradually

advanced from the lowest towards the highest offices in the firm.

Circumstances occurred which led his employers to send him into the

North of England, as traveller for the firm; and then it was that he

made his first acquaintance with Manchester. He observed the abundant

opportunities which the district presented for business, and the scope

which it afforded for enterprise and energy; and he determined, when the

opportunity should offer, to begin there on his own account. Two of his

fellow-servants, Messrs. Sherroff and Foster, shortly after offered to

join him, and in a few years we find them engaged in a calico-printing

business at Sabden, in the neighbourhood of Clitheroe, in Lancashire. The firm prospered, and subsequently Cobden separated from his first

partners, and began the same business on a larger scale, in company with

his elder brother, at Chorley, also in Lancashire.

Meanwhile Richard settled in Manchester, and conducted the warehouse

branch of the business there. The Cobden prints became celebrated for

their taste, as well as quality; they competed successfully with the

best quality of London goods, and soon fetched the highest prices in the

market. An instance of their success may be incidentally mentioned. A

gentleman who happened to visit Mr. Cobden's warehouse in Manchester

was there favoured with the sight of some new printed muslin of a

peculiar pattern, about three days before they were issued to the

public. In less than a week from the day these dresses were despatched

from the warehouse, the same gentleman was at Chichester, and, walking

in the direction of Goodwood, he met some ladies of the Duke of

Richmond's family wearing the identical prints; and, in a few days

after, the same gentleman was at Windsor, and saw the Queen walking on

the slopes wearing a dress of the same kind,—so instantly did the

"Cobden prints" take the lead in the fashionable world. For Mr. Cobden

studied public taste, as he has since studied public opinion, and he

rarely, if ever, made a speculation (and this branch of trade is always

exceedingly precarious and hazardous) in which he was not completely

successful. He had, indeed, been so successful as a man of business at

the time when the Anti-Corn-Law agitation commenced, that, had he

retired then, he could have done so with a saved capital of about

£60,000.

Mr. Cobden was not for some time known in connection with public affairs

in Manchester. He was too modest and retiring to take a prominent part

in the strife of politics, however much he may have felt interested in

public questions. One of the first movements to which he gave himself

was the overthrowing of the old lord-of-the-manor government of

Manchester, and its constitution as a municipal borough, under its

present charter; and we may incidentally mention, that one of the first

members of the Manchester Council was "Mr. Alderman Cobden." He also

appeared, on several occasions, as the advocate of public education free

from sectarian bias, and made several public appearances as a supporter

of the British and Foreign Society's schools.

He was also mainly instrumental in establishing the Manchester Athenæum,

an institution for the intellectual recreation and improvement of young

men chiefly belonging to the mercantile class. His project met with

considerable opposition from the slow-going old merchants of the place;

and many years after, at the meeting of a country Mechanics' Institute,

he thus alluded to the subject.

"It has," said he,

"been objected, that the poor may be too much

educated. But you may just as well be afraid of all the poor riding

about in coaches and four, or playing the piano, as fear that they will

be too well educated. Admitting that it would be unwise to educate the

poor as well as the rich are educated,—admitting it for argument's

sake,—there are two great, and I fear wholly insuperable obstacles, to

that state of things ever arriving; the one is the want of time, the

other the want of means. So long as these obstacles exist, the rich need

be in no fear that the poor will be better educated than they are. I

remember waiting on a person holding this doctrine in Manchester about

sixteen years ago, where I and others were engaged in the work of

starting the Manchester Athenæum. I was employed in waiting upon the

principal merchants, manufacturers, and tradesmen of the town, asking

for subscriptions with that object. One gentleman met me with this

objection: 'I think the people are a good deal too much educated

already. I don't think we shall be safe if they are to be educated any

more; and our property will be in danger if this goes on.' I met him by

putting to him this question: 'Will you tell me in what period of the

world's history you would rather have lived than the present, in order

to have had your vast fortune safer than it is now?' Well, he could not

answer me. I urged him to point out the period he would have selected:

'Would you have preferred the last reign, or the reign before, or the

reign of George I., or the reign of Queen Anne, or that of Queen

Elizabeth, in order to have lived in greater security both as regards

your person and property?' Why, he could not tell me. And so I answered

my own question by saying: 'You would be much safer if you lived thirty

or forty years hence; but not if you were to go back to any time,

however remote.' This is the tendency of those institutions; and yet

people are to be found who charge against them that they produce

disaffection, disloyalty, and revolution. Now, disloyalty and revolution

come to the people from misgovernment; and misgovernment is more likely

to be attempted upon an ignorant than upon an educated people. We have

been well told that 'oppression makes wise men mad.' And I remember

this being very well applied by a man who was lecturing upon the Corn

Laws at Bury,—a man perhaps not highly educated, yet by no means

destitute of shrewdness. The lecturer said, 'Oppression makes wise men

mad. If it maks "wise men mad," what mun it do wi' fooils then?' I

think, gentlemen, you will agree with the inference which the lecturer

left his auditory to draw, that whatever effect misgovernment or

oppression had upon wise men, it must produce worse and more disastrous

effects when the ignorant and the fools come to deal with it. Therefore,

you cannot do a worse thing than to encourage ignorance."

Such is an illustration of the homely yet forcible style in which Mr.

Cobden is accustomed to fix important truths in the minds of the

audiences he addresses.

It was not until the year 1835—when he made a visit to Turkey and the

East, partly with an eye to business—that Mr. Cobden became known beyond

the bounds of his own district as a keen observer and an original

thinker. The result of this visit was the publication of the pamphlet

entitled "England, Ireland, and America, by a Manchester Manufacturer." In that little work, we find almost the whole policy of Mr. Cobden

foreshadowed. Peace, retrenchment, non-intervention, and free trade were

there his first watchwords, and he did not abandon them. He held that

what England should do was, not to occupy herself with what Russia could

or would do in the East, but to abolish the Corn Laws, stick to trade

and commerce, and refuse to meddle with questions of foreign politics,

in which, his opinion was, England could do no good, but might work

infinite mischief. The idea of a Free-Trade Association, such as was

afterwards adopted by the Anti-Corn-Law League, seems, even at that

early period, to have occurred to the mind of Mr. Cobden.

"Here let us observe," said he, in the pamphlet referred to,

"that it

is worthy of surprise how little progress has been made in the study of

that science of which Adam Smith was, more than half a century ago, the

great luminary. We regret that no society has been formed for the

purpose of disseminating a knowledge of the just principles of trade. Whilst agriculture can boast almost as many associations as there are

British counties, whilst every city in the kingdom contains its

botanical, phrenological, or mechanics' institutions, and these again

possess their periodical journals, (and not merely these, for even war

sends forth its United Service Magazine,) we possess no association of

traders, united together for the common object of enlightening the world

upon a question so little understood, and so loaded with obloquy, as

free trade. We have our Banksian, our Linnæan, our Hunterian societies;

and why should not at least our greatest commercial and manufacturing

towns possess their Smithian societies, devoted to the purposes of

promulgating the beneficent truths of the 'Wealth of Nations'? Such

institutions, by promoting a correspondence with similar societies, that

could probably be organized abroad, (for it is our example in questions

affecting commerce that strangers follow,) might contribute to the

spread of liberal and just views of political science, and thus tend to

ameliorate the restrictive policy of foreign governments, through the

legitimate influence of the opinions of its people. Nor would such

societies be fruitless at home. Prizes might be offered for the best

essays on the corn question; or lecturers might be sent to enlighten the

agriculturists, and to invite discussion upon a subject so difficult,

and of such paramount importance to all."

The views, thus enunciated in 1835, Mr. Cobden consistently pursued in

his after career; and his last public act has been an effort to

ameliorate the restrictive policy of the government of England's nearest

neighbour, France,—with what good result yet remains to be seen. But we

anticipate.

From this time forward Mr. Cobden was regarded as a leading public man

in Manchester. His judgment was sought after and valued; his eminent

business talent was fully recognized; and he was usually invited to take

part in any public movements of importance affecting the interests of

the district. Yet he never thrust himself on the attention of his

fellow-citizens; rather shunning than courting the public applause. Modesty, diffidence, and an entire absence of vanity and jealousy, have

throughout distinguished his career as a public man. In 1837 he was

invited to stand as a candidate for the borough of Stockport, but on a

contest his opponent was returned by a majority of votes. It was

probably better that he remained out of Parliament at the time,

otherwise the organization and conduct of the Anti-Corn-Law League might

not have been so successful as in his hands it subsequently proved to

be. The beginning of this celebrated movement was comparatively

insignificant. One Dr. Birney—who was never afterwards heard

of—advertised a lecture against the Corn Laws in the Bolton Theatre, on

the 4th of August, 1838, but his performance was so unsatisfactory that

he was hissed off the stage; on which a gentleman named Paulton, who was

sitting in one of the boxes, rushed forward to save the flying Doctor. He himself undertook to deliver the lecture, and did so. Next week, and

the next again, he called the people together on the same subject; and

the movement was thus born. Mr. Paulton next gave his lectures at

Manchester and Leeds, at which latter town we heard them, at the end of

1838, delivered before a very small and comparatively indifferent

audience. In the meantime a small number of persons at Manchester

formed themselves into a Committee, and raised a fund in five-shilling

subscriptions to support the movement. The Manchester Chamber of

Commerce met on the 13th of December, 1838, to discuss a motion of which

notice had been given, relative to petitioning Parliament for a total

repeal of the Corn Laws; and at that meeting Mr. Cobden took a bold and

decided part as the advocate of the measure, and he submitted a petition

which was carried by a great majority. Larger subscriptions were raised;

lecturers were sent out from Manchester to all parts of the kingdom;

convocations of leading men were held in various towns; a special organ,

the Anti-Bread-Tax Circular, was started to record progress and

chronicle facts; and a Free-Trade Hall, capable of accommodating immense

meetings, was erected on the site of the field of Peterloo, [p.109] to

give force and energy to the movement. The League had by this time also

got its name. At a meeting of three hundred delegates held in London

about the beginning of 1839, when Mr. Cobden spoke of the Hanseatic

League, and asked those present "why they should not have a League of

the towns of England against the aristocracy who ruled them, ruined

their trade, and had just refused them a hearing," some one called out,

"An Anti-Corn-Law League!" Mr. Cobden continued, "Yes! An Anti- Corn-Law

League!" And thus the name was given.

Though the League and its proceedings gave rise to much discussion in

the public press and in Parliament, the number of those who actively

directed the movement was at first very small, and their position

comparatively insignificant. Mr. Cobden himself thus described the early

days of the League to the writer of this memoir in 1841:—

"The work," said he,

"has been done by a very few,—so few that we have

been the laughing-stock even of ourselves, as we sat and chuckled over

the splutter we were making in the name of The League. You have not an

idea how insignificant a body the working members of the League really

comprise. Still we worked. When we could not hold public meetings, we

got up little hole-and-corner meetings. Two years and a half ago we

called a public meeting; the Chartist leaders attacked us on the

platform at the head of their deluded followers. We were nearly the

victims of physical force. I lost my hat, and all but had my head split

with the leg of a stool. In retaliation for this, we deluged the town

with short tracts printed for the purpose. We called meetings of each

trade, and held conferences with them at their own lodges. We found

ready listeners and many secret allies, even amongst the Chartists. We

resolutely abstained from discussing the Charter or any other party

question. We stuck to our subject; and the right-minded amongst the

working-men gave us credit for being in earnest, which is all that is

necessary to secure the confidence of the people. Our strength grew, and

the result is that we can now hold a public meeting at any moment. We

shall work on in Manchester; there is much that remains to be done. Why

do I go over our exploits? Not for egotistical display,—we have done no

more than our duty,—but simply to give you the assurance that everything

may be done in Leeds and elsewhere by working perseveringly in the cause

of Corn-Law Repeal."

In this earnest spirit did Richard Cobden labour for many years,

Manchester being the centre of a series of operations which radiated

therefrom unto the remotest districts of Britain. It is impossible to

describe the extent of his labours in connection with this great

movement,—correspondence with the leaders of public opinion,

encouragement to the desponding, help to the weak, and stimulus to the

inert,—everywhere was his pen and voice at work. At public meetings he

was put in the front rank, for he never put himself there. But, as he

said, he was always ready to fill up any gap. His enthusiastic belief in

the economical truths which he advocated bore him up in the face of

overwhelming opposition;—he hoped against hope, and was resolute when

others were full of despair. Yet even he was not without his moments of

private doubt and fear. Writing in November, 1841, he said:—

"I am told from all sides, that unless we do something, and

strike a blow, we shall lose confidence. What can we do? There is always

danger of being made ridiculous by showing one's teeth before one is

able to bite. If we were to attempt a coup, and it were to fail like

the Chartist holiday, we should be laughed at forever. Should some

practical measures not be speedily carried, they will come too late,—and what rational man can say that we are in a fair way for doing

anything very soon? Still, what more can we do, than what we are doing? At least, we are not standing in the way of a more hopeful movement; for

of the three questions that now agitate the people,—Repeal of Corn Law,

Repeal of Union, and Charter,—I can't help thinking that our question

stands in the place of the favourite in the public mind. Bad is the

prospect even of the best; but so long as there is no better to which to

resign the course, we must work away with whip and spur, keeping our

head steadily towards the far-distant winning-post."

Usually, however, Mr. Cobden was much more sanguine in his

anticipations, and never allowed any exertions to flag for want of

encouragement and stimulus on his part.

At length Mr. Cobden was sent to Parliament to carry forward there the

advocacy of the Repeal. In 1840 he was invited to stand for Manchester,

but declined to do so, on the ground that he was not to be allowed to

enter Parliament a free man; the committee who waited on him having

represented the expediency of letting principle be subservient to party

arrangements,—a thing to which Mr. Cobden declared that his conscience

would never allow him to give his assent. But the Whig government, which

he was expected to support, having fallen to pieces, and Peel having

been made minister to maintain the Corn Laws, the ground was now clear,

and Mr. Cobden offered himself again at Stockport, and this time he was

returned.

Many were the predictions of his political enemies, that his appearance

in Parliament would be a failure. Cobden was now to "find his level." The poor farmer's son could never lift up his head amongst the proud

lords of the soil, and dare to measure his strength with them, nor would

his have been the first popular reputation of which St. Stephen's had

been the death. But Cobden was not a mere popular spouter. He had been

admirably disciplined by business, by reading, and by reflection; he

was an apt and fluent speaker, full of treasured information; above all,

he possessed great moral courage and earnestness, and deep-rooted

convictions. Such a man was sure of making himself heard by any

audience. The following is Mr. Bright's account of Cobden's first

appearance in Parliament:—

"Mr. Cobden," said he,

"entered the House of Commons in the year 1841,

two years before I became a member of that house. I believe I was in the

gallery on the night when he made his first speech. I happened to sit

close to a gentleman, not now living,—Mr. Horace Twiss,—who had once

himself been a member of the House, but who was then occupied in the

gallery, writing the Parliamentary summary of the proceedings which were

published morning after morning in the columns of the Times newspaper. Mr. Cobden had a certain reputation when he went into Parliament, from

the course he had taken before the public in connection with the Corn

Law out of doors. There was great interest as to his first speech, and

the position he would take in the House. Horace Twiss was a Tory of the

old school. He appeared to have the greatest possible horror of anybody

who was a manufacturer or calico-printer coming down into that assembly

to teach our senators wisdom. As the speech went on I watched his

countenance and heard his observations, and when Mr. Cobden sat down he

threw it off with a careless gesture, and said, 'Nothing in him; he is

only a barker.'"

In his first speech, as in his last, Mr. Cobden's object was to

convince. He never strove to triumph, but to persuade. The things he

said might be disagreeable, but he must say them quietly, winningly,

and at length persuasively. He secured the ear of the House, and

steadily made his position good. The Anti-Corn-Law movement came to be

recognized as a great fact, even within the walls of Parliament. It made

its way there steadily, as well as throughout the country; and at

length, in 1846, the long and arduous struggle was brought to a

close,—Sir Robert Peel proclaiming that the person to whom the honour of

the triumph was mainly due was Richard Cobden.

We believe that Mr. Cobden was influenced by no narrow political motives

in his great enterprise to secure freedom of trade for England with the

nations of the world. It was not a mere money question with him, but one

of ultimate human happiness and civilization. While he has a keen eye to

the actual necessities of living men, he has also his eye directed

towards the future, and sees in the consummation of the measure for

which he so zealously laboured, the triumph of peace, and the prevalence

of social happiness. "I believe," said he, at a public meeting in

Manchester, "that the physical gain will be the smallest gain to

humanity from its success. I see in free trade that which shall act on

the moral world as the law of gravitation in the universe,—drawing men

together, thrusting aside the antagonism of race and creed and language,

and uniting us in the bonds of eternal peace. I believe that the desire

and the motive for large and mighty empires, for gigantic armies and

great navies, for those materials which are used for the destruction of

life and the desolation of the rewards of labour, will die away. I

believe that such things will cease to be necessary, or to be used, when

man becomes one family, and freely exchanges the fruits of his labour

with his brother man." Mr. Cobden, we believe, sees as clearly as most

thinking men, that the struggle for free commerce is only part of a

struggle for a still larger freedom; and that beyond the question of

political economy there is also the great problem of social economy to

be solved,—how the means of happiness are to be the most equitably

distributed for the well-being of those who produce them.

On the fall of Peel's government, Lord John Russell communicated to Mr.

Cobden his intention of offering him a seat in the new Cabinet; but,

fearing lest the position should interfere with his independence of

speech and action, Cobden declined the offer. As a relief from the

turmoil of public life, he proceeded to make a tour on the Continent,

which was intended to be a holiday; but the ovations which he received

during his journey made it rather appear the mission of a propagandist. During his absence, the largest constituency in England—that of the West

Riding of York—spontaneously elected him as their representative; and he

accepted the honour. One of the things which most struck him while abroad

was the hosts of armed men, withdrawn from industry, who were kept up in

every Continental nation,—men in the prime of life, assembled in immense

armies, for the purpose of watching each other across their respective

frontiers,—millions of idle soldiers, eating off the very head of

industry, breeding future revolutions and convulsions, if not bringing

political perdition upon the great states of Europe. He saw too, that,

in consequence of this vast armature of the Continental nations, England

was, in a measure, compelled to maintain a similar attitude; and,

desirous of abating the evil, he appealed to public opinion, and

strongly pleaded for a general national disarmament. A Peace Society was

formed, and convocations were held in London, Paris, Brussels, and

Berlin; but we need scarcely say that the movement was followed by no

practical results, for Europe now bristles with bayonets more than ever,

and all the European governments are sedulously arming their subjects

with Enfields, Minies, and needle-guns, one of the chief topics of the

day being the discussion of the respective merits of rifled cannon of

recent invention. Yet Mr. Cobden was right; and when reaction sets

in,—as set in again it assuredly will,—the truth and the elevated

consistency of his views will not fail to be extensively recognized. The

unpopularity, however, of Mr. Cobden's advocacy of peace principles,

more especially in connection with the Russian war, lost him his seat in

Parliament; and it was not until during his absence on a visit to

America, in 1859, that he was returned without opposition for the

borough of Rochdale.

During Mr. Cobden's almost exclusive devotion to the cause of Free Trade

for so many years, his extensive business was necessarily neglected, and

when he proceeded to take stock at the close of the agitation which

ended in the repeal of the Corn Laws, he found he was scarcely square

with the world. The nation whom he had served so well generously came

forward to his assistance at this juncture, and a subscription of £70,000 was raised, which enabled him to pay off his debts, and to return

to his little estate at Medhurst, which was purchased with a portion of

the fund. The greater part of the remainder was unhappily invested by

his friends in Illinois Central Bonds, and there it remained

unproductive. A subsequent voluntary subscription has since been raised

by his friends, and already amounts to about £40,000, which we trust Mr.

Cobden will long live to enjoy. Unquestionably the same amount of energy

and devotedness applied to business, which Mr. Cobden gave to the cause

of Free Trade, could not have failed to build up for him a gigantic

fortune; and it is only right that so beneficent a worker should not

suffer the loss of his fortune, through his devotion to a great public

cause.

Take him all in all, Mr. Cobden is a man of rare intelligence, of

unswerving industry, and of spotless integrity. In qualities of head and

heart, we believe him to be excelled by few men. His conscientiousness

is of the highest order. Though he has had much political enmity to

encounter, no one has ever charged him with doing a mean thing, or

prostituting the great power he unquestionably wielded to subserve any

personal or selfish end. His eloquence—or rather his persuasiveness—is

remarkable. He practises none of the graces of the orator. His style is

simple, almost homely, but thoroughly logical and convincing; and his

matter is full always of facts. He emphatically hits the nail on the

head, clinching it at both sides. In person he is pale, lean, and wiry,

of melancholic features; and his voice is thin, and sounds somewhat

nasal. Yet, with these personal disadvantages, the influence which he

exercises as a speaker is something extraordinary. We believe the secret

to lie in his immense fund of common sense, his great practical sagacity

and shrewdness, his evident honesty of purpose and earnest

straightforwardness, and, at the same time, the clearness and simplicity

of speech which enables him to bring his reasonings and his facts

completely home to the judgment, and appeal so powerfully to the silent

judge in every man's bosom. It matters not what description of audience

he addresses,—be they members of Parliament, Manchester manufacturers,

Stockport operatives, or Sussex ploughmen,—he invariably secures and

rivets their attention. He thoroughly knows the men he addresses; he

adapts himself to them; he enters into their very minds and hearts; he

carries them along with him entirely; and thus achieves triumphs as

great as if he were the most accomplished of orators.

――――♦――――

SIR EDWARD BULWER LYTTON.

FEW living writers

have done more, or achieved a higher standing in his own peculiar line

of literature, than Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton has done. That he has been

a very hard worker, his numerous works bear ample witness. When Sir

Walter Scott died, Bulwer at once succeeded him in the living and

hopeful interest of the readers of fiction, and he has since retained

his supremacy over all writers of the same school.

But not only has he succeeded as a novelist; he has been equally

successful as a dramatist. For, is not "The Lady of Lyons" the most

popular of modern plays? What modern drama is to be compared with it in

point of attraction and living interest? It may be open to the

strictures of the critic, but it has been unequivocally successful,

unprecedentedly productive to managers, and in the hands of a good

company it is really an exceedingly beautiful play.

But Bulwer has done more than this. He has written a History, which may

take its place on the same shelves with Gibbon and Arnold and Grote. His

"Athens, its Rise and Fall," has extorted praise from all quarters, and

is a noble historical work, though but a fragment. In this department of

literature Bulwer has succeeded where even Scott failed; for the History

of Napoleon of the latter will be forgotten, while his Waverley and

Ivanhoe will continue the delight of thousands.

Bulwer's success has been equally marked in other

literary directions. He has written essays which might take their

place beside the choicest specimens of Charles Lamb or Leigh Hunt.

His leading articles in newspapers, and his reviews in the monthlies and

quarterlies, have been mistaken for the productions of the most elegant

living writers. His political pamphlet, published on the death of

Earl Spencer, was one of the most brilliant productions of its kind.

His poems, also, have been eminently successful; and many of

them are beautiful in a high degree. Let any one read his "Lay of

the Beacon," and say if Bulwer is not entitled to be called a successful

poet, as well as a successful novelist, a successful dramatist, and a

successful historian.

Now, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton must unquestionably have worked

hard to achieve success in these several paths of literature. On

the score of mere industry, there are few, if any, living English

writers who have produced so much, and none who have produced so much of

the same quality. And when you consider that he was born to

comparative ease, and did not need to work so hard, it will be admitted,

we think, that his industry is entitled to all the greater praise.

Riches are quite as great a hindrance to intellectual labour as poverty

can be; their temptations are difficult to be forborne, and they are

often not resisted. To hunt, and shoot, and live at ease,—to

frequent operas, and clubs, and Almack's, enjoying the variety of London

sight-seeing, morning calls, and Parliamentary small-talk, during "the

season," and then off to the country mansion, with its well-stocked

preserves and its thousand delightful pleasures, alternated with a few

months on the Scotch moors, or a run across the Continent, to Venice or

Rome,—all this is excessively attractive, and is not by any means

calculated to make a man "scorn delights and live laborious days."

And yet by Bulwer these pleasures, all within his reach, were

to a great extent necessarily forborne, when he assumed the position and

pursued the career of a literary man. Though he did not require to

do so, he yet volunteered to work hard; doubtless he must have taken a

high pleasure in the work, otherwise we should have seen much less of

him as an author than we have done. Indeed, all his sympathies

seem to be literary, as his labours mainly are. His society is

literary, and his public acts are identified with literature. One

of his earliest Parliamentary efforts was to obtain an Act enabling

dramatic authors to receive benefit from the acting of their plays in

provincial theatres, which formerly they were unable to do. He

also aided in the reduction of the stamp duty on newspapers, and in the

improvement of the law of copyright. And recently, we have seen

him co-operating with a body of dramatists, artists, and literary men,

in the philanthropic effort to establish a Guild of Literature and Art,

in the shape of a Life Insurance Company, connected with other admirable

arrangements, by which the independence and comfort of literary men and

women in advanced years will be secured.

Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton (1803-73):

English novelist, poet, playwright, and politician.

Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton is the younger son of the late

General Bulwer of Heydon Hall, in the county of Norfolk. His elder

brother, Sir Henry Lytton Bulwer, the author of "The Monarchy and Middle

Classes of France," was for some time English Ambassador at Madrid,—he

is now Ambassador at Washington,—and inherits the paternal family

estate. Sir Edward, on the death of his mother, in 1843, succeeded

to the estate of Knebworth, of which she was heiress, and then he

assumed the final name of Lytton. The literary talent of the

family seems to come mainly from the mother's side. Her father was

a great scholar, the first Hebraist of his day, and above Porson himself

in the judgment of Dr. Parr. He wrote dramas in Hebrew, but he

neglected his estates, which were fast going to decay under the care of

stewards, when Mrs. Bulwer, his daughter, whose husband died and left

her a young widow, went back to reside at Knebworth, with her family.

She was a woman of great energy, and at once employed herself in the

improvement of the Knebworth estate, and the preservation of what

remained of the old hall. In a beautiful paper, contained in the

volume of essays called "The Student," Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton says,

the old manorial seat was formerly of vast extent, "built round a

quadrangle at different periods, from the date of the second crusade to

that of the reign of Elizabeth. It was in so ruinous a condition

when my mother came to its possession, that three sides of it were

obliged to be pulled down; the fourth, yet remaining, is in itself a

house larger than most in the country, and still contains the old oak

hall, with its lofty ceiling and raised music-gallery. The park

has something of the character of Penshurst; and its venerable avenues,

which slope from the house down the gradual acclivity, giving wide views

of the opposite hills, crowned with cottages and spires, impart to the

scene that peculiarly English, half-stately and wholly cultivated

character, upon which the poets of Elizabeth's day so much loved to

linger."

"In this old place," Sir Edward says, "the happiest days of

my childhood glided away." In the course of his writings, he shows

a tender regard for his mother, who educated him here, and he delights

to acknowledge the deep obligations under which he lay to her, by the

direction she gave to his taste and studies, and the beneficial

influence which she exercised upon his character in early life. In

the beautiful dedication of his collected works to his mother, he says:

"Left yet young, with no ordinary accomplishments and gifts, the sole

guardian of your sons, to them you devoted the best years of your useful

and spotless life; and any success it be their fate to attain in the

paths they have severally chosen, would have its principal sweetness in

the thought that such success was the reward of one whose hand aided

every struggle, and whose heart sympathized with every care. From

your graceful and accomplished taste I early learned that affection for

literature which has exercised so large an influence over the pursuits

of my life; and you who were my first guide were my earliest critic."

The boy began to write verses when five or six years old,

which shows that early taste or early direction must have guided his

hand. Alluding to the gentle and polished verses of his mother, in

the dedication referred to, he says, "It was those easy lessons, far

more than the harsher rudiments learned subsequently in schools, that

taught me to admire and to imitate." And he adds to this a

reverential acknowledgment of the qualities, compared with which all

literary accomplishments are poor: "Happy, while I borrowed from your

taste, could I have found it not more difficult to imitate your

virtues,—your spirit of action and extended benevolence, your cheerful

piety, your considerate justice, your kindly charity,—and all the

qualities that brighten a nature more free from the thought of self than

any it has been my lot to meet with." One of the last works of her

old age was the erection and endowment of an almshouse for the widows of

the poor, which she just lived to complete, an example which her son is

nobly imitating in the Guild of Literature and Art, which he is now

exerting himself to establish.

Bulwer's first appearance before the public was in the

character of a poet. At Cambridge, where he studied, he was the

successful competitor for the prize poem of his year; and shortly after,

in 1826, he published his first book, bearing the juvenile title of

"Weeds and Wild-Flowers." In the year following, he published

"O'Neil, or the Rebel," a poetical tale, after the manner of Byron's

"Corsair." It resembled the verse of Byron, without the poetry.

The wings of the young writer were scarcely fledged yet, and it took him

many efforts before he could rise above the imitative and commonplace.

"Falkland," his first novel, published in the same year (1827), was also

a failure: it was decidedly Byronesque, and, but for the author's

subsequent celebrity, would soon have been utterly forgotten. He

himself became ashamed of it, and refused to include it in his collected