|

[Previous Page]

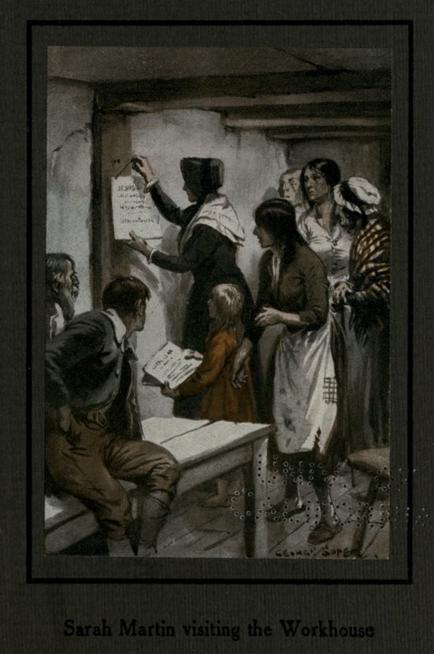

SARAH MARTIN.

Sarah Martin (1791-1843): English prison visitor and philanthropist.

AMONG the distinguished women in the humble ranks of society, who

have pursued a loving, hopeful, benevolent, and beautiful way

through life, the name of Sarah Martin will long be remembered. Not

many of such women come into the full light of the world's eye. Quiet and silence befit their lot. The best of their labours are

done in secret, and are never noised abroad. Often the most

beautiful traits of a woman's character are confided but to one dear

breast, and lie treasured there. There are comparatively few women

who display the sparkling brilliancy of a

Margaret Fuller, and whose

names are noised abroad like hers on the wings of fame. But the

number of women is very great who silently pursue their duty in

thankfulness, who labour on,—each in their little home-circle,—training the minds of growing youth for active life, moulding future

men and women for society and for each other, imbuing them with

right principles, impenetrating their hearts with the spirit of

love, and thus actively helping to carry forward the whole world

towards good. But we hear comparatively little of the labours of

true-hearted women in this quiet sphere. The genuine mother, wife,

or daughter is good, but not famous. And she can dispense with the

fame, for the doing of the good is its own exceeding great reward.

Very few women step beyond the boundaries of home and seek a larger

sphere of usefulness. Indeed, the home is a sufficient sphere for

the woman who would do her work nobly and truly there. Still, there

are the helpless to be helped, and when generous women have been

found among the helpers, why should we not rejoice in their good

works, and cherish their memory? Sarah Martin was one of such,—a

kind of Elizabeth Fry, in a humbler sphere. She was born at Caister,

a village about three miles from Yarmouth, in the year 1791. Both

her parents, who were very poor people, died when she was but a

child; and the little orphan was left to be brought up under the

care of her poor grandmother. The girl obtained such education as

the village school could afford,—which was not much,—and then she

was sent to Yarmouth for a year, to learn sewing and dressmaking in

a very small way. She afterwards used to walk from Caister to

Yarmouth and back again daily, which she continued for many years,

earning a slender livelihood by going out to families as an

assistant dressmaker at a shilling a day.

It happened that, in the year 1819, a woman was committed to the

Yarmouth jail for the unnatural crime of cruelly beating and

ill-using her own child. Sarah Martin was at this time eight and

twenty years of age, and the report of the above crime, which was

the subject of talk about the town, made a strong impression on her

mind. She had often, before this, on passing the gloomy walls of the

borough jail, felt an urgent desire to visit the inmates pent up

there, without sympathy, and often without hope. She wished to read

the Scriptures to them, and bring them back lovingly—were it yet

possible—to the society against whose laws they had offended. Think

of this gentle, unlovely, ungifted, poor young woman taking up with

such an idea! Yet it took root in her and grew within her. At length

she could not resist the impulse to visit the wretched inmates of

the Yarmouth jail. So one day she passed into the dark porch with a

throbbing heart, and knocked for admission. The keeper of the jail

appeared. In her gentle, low voice, she mentioned the cruel mother's

name, and asked permission to see her. The jailer refused. There was

"a lion in the way,"—some excuse or other, as is usual in such

cases. But Sarah Martin persisted. She returned; and at the second

application she was admitted.

Sarah Martin afterwards related the manner of her reception in the

jail. The culprit mother stood before her. She was surprised at the

sight of a stranger. "When I told her," says Sarah Martin, "the

motive of my visit, her guilt, her need of God's mercy, &c., she

burst into tears, and thanked me!" Those tears and thanks shaped the

whole course of Sarah Martin's subsequent life.

A year or two before this time Mrs. Fry had visited the prisoners in

Newgate, and possibly the rumour of her labours in this field may

have in some measure influenced Sarah Martin's mind; but of this we

are not certain. Sarah Martin herself stated that, as early as the

year 1810 (several years before Mrs. Fry's visits to Newgate), her

mind had been turned to the subject of prison visitation, and she

had then felt a strong desire to visit the poor prisoners in

Yarmouth jail, to read the Scriptures to them. These two

tender-hearted women may, therefore, have been working at the same

time, in the same sphere of Christian work, entirely unconscious of

each other's labours. However this may be, the merit of Sarah Martin

cannot be detracted from. She laboured alone, without any aid from

influential quarters; she had no persuasive eloquence, and had

scarcely received any education; she was a poor seamstress,

maintaining herself by her needle, and she carried on her visitation

of the prisoners in secret, without any one vaunting her praises:

indeed, this was the last thing she dreamt of. Is there not, in this

simple picture of a humble woman thus devoting her leisure hours to

the comfort and improvement of outcasts, much that is truly noble

and heroic?

Sarah Martin continued her visits to the Yarmouth jail. From one she

went to another prisoner, reading to them and conversing with them,

from which she went on to instructing them in reading and writing. She constituted herself a schoolmistress for the criminals, giving

up a day in the week for this purpose, and thus trenching on her

slender means of living. "I thought it right," she says

"to give up

a day in the week from dressmaking to serve the prisoners. This,

regularly given, with many an additional one, was not felt as a

pecuniary loss, but was ever followed with abundant satisfaction,

for the blessing of God was upon me."

She next formed a Sunday service in the jail, for reading of the

Scriptures, joining in the worship as a hearer. For three years she

went on in this quiet course of visitation, until, as her views

enlarged, she introduced other ameliorative plans for the benefit of

the prisoners. One week, in 1823, she received from two gentlemen

donations of ten shillings each, for prison charity. With this she

bought materials for baby-clothes, cut them out, and set the females

to work. The work, when sold, enabled her to buy other materials,

and thus the industrial education of the prisoners was secured;

Sarah Martin teaching those to sew and knit who had not before

learnt to do so. The profits derived from the sale of the articles

were placed together in a fund, and divided amongst the prisoners on

their leaving the jail to commence life again in the outer world. She, in the same way, taught the men to make straw hats, men's and

boys' caps, gray cotton shirts, and even patchwork,—anything to keep

them out of idleness, and from preying upon their own thoughts. Some, also, she taught to copy little pictures, with the same

object, in which several of the prisoners took great delight. A

little later on, she formed a fund out of the prisoners' earnings,

which she applied to the furnishing of work to prisoners upon their

discharge; "affording me," she says, "the advantage of observing

their conduct at the same time."

Thus did humble Sarah Martin, long before the attention of public

men had been directed to the subject of prison discipline, bring a

complete system to maturity in the jail of Yarmouth. It will be

observed that she had thus included visitation, moral and religious

instruction, intellectual culture, industrial training, employment

during prison hours, and employment after discharge. While learnèd

men, at a distance, were philosophically discussing these knotty

points, here was a poor seamstress at Yarmouth, who, in a quiet,

simple, and unostentatious manner, had practically settled them all!

In 1826 Sarah Martin's grandmother died, and left her an annual

income of ten or twelve pounds. She now removed from Caister to

Yarmouth, where she occupied two rooms in an obscure part of the

town; and from that time devoted herself with increased energy to

her philanthropic labours in the jail. A benevolent lady in

Yarmouth, in order to allow her some rest from her sewing, gave her

one day in the week to herself, by paying her the same on that day

as if she had been engaged in dressmaking. With that assistance, and

a few quarterly subscriptions of two shilling and sixpence each, for

Bibles, Testaments, tracts, and books for distribution, she went on,

devoting every available moment of her life to her great purpose. But her dressmaking business—always a very fickle trade, and at best

a very poor one—now began to fall off, and at length almost entirely

disappeared. The question arose, Was she to suspend her benevolent

labours, in order to devote herself singly to the recovery of her

business? She never wavered for a moment in her decision. In her own

words,

"I had counted the cost, and my mind was made up. If, whilst

imparting truth to others, I became exposed to temporal want, the

privation so momentary to an individual would not admit of

comparison with following the Lord, in thus administering to

others."

Therefore did this noble, self-sacrificing woman go

straightforward on her road of persevering usefulness.

She now devoted six or seven hours in every day to her

superintendence over the prisoners, converting what would otherwise

have been a scene of dissolute idleness into a hive of industry and

order. Newly-admitted prisoners were sometimes refractory and

unmanageable, and refused to take advantage of Sarah Martin's

instructions. But her persistent gentleness invariably won their

acquiescence, and they would come to her and beg to be allowed to

take their part in the general course. Men old in years and in

crime, pert London pickpockets, depraved boys, and dissolute

sailors, profligate women, smugglers, poachers, the promiscuous

horde of criminals which usually fill the jail of a seaport and

county town, all bent themselves before the benign influence of this

good woman; and under her eyes they might be seen striving, for the

first time in their lives, to hold a pen, or master the characters

in a penny primer. She entered into their confidences, watched,

wept, prayed, and felt for all by turns; she strengthened their good

resolutions, encouraged the hopeless, and sedulously endeavoured to

put all, and hold all, in the right road of amendment.

What was the nature of the religious instruction given by her to the

prisoners may be gathered from Captain Williams's account of it, as

given in the "Second Report of the Inspector of Prisons" for the

year 1836:

"Sunday, November 29, 1835.—Attended divine service in the

morning at the prison. The male prisoners only were assembled. A

female resident in the town officiated; her voice was exceedingly

melodious, her delivery emphatic, and her enunciation extremely

distinct. The service was the Liturgy of the Church of England; two

psalms were sung by the whole of the prisoners, and extremely

well,—much better than I have frequently heard in our best-appointed

churches. A written discourse, of her own composition, was read by

her; it was of a purely moral tendency, involving no doctrinal

points, and admirably suited to the hearers. During the performance

of the service, the prisoners paid the profoundest attention and the

most marked respect; and, as far as it was possible to judge,

appeared to take a devout interest. Evening service was read by her,

afterwards, to the female prisoners."

Afterwards, in 1837, she gave up the labour of writing out her

addresses, and addressed the prisoners extemporaneously, in a

simple, feeling manner, on the duties of life, on the connection

between sin and sorrow on the one hand, and between goodness and

happiness on the other, and inviting her fallen auditors to enter

the great door of mercy which was ever wide opened to receive them. These simple but earnest addresses were attended, it is said, by

very beneficial results; and many of the prisoners were wont to

thank her, with tears, for the new views of life, its duties and

responsibilities, which she had opened up to them. As a writer in

the Edinburgh Review has observed, in commenting on Sarah Martin's

jail sermons:

"The cold, laboured eloquence which boy-bachelors are

authorized by custom and constituted authority to inflict upon us;

the dry husks and chips of divinity which they bring forth from the

dark recesses of the theology (as it is called) of the fathers, or

of the Middle Ages, sink into utter worthlessness by the side of the

jail addresses of this poor, uneducated seamstress."

But Sarah Martin was not satisfied merely with labouring among the

prisoners in the jail at Yarmouth. She also attended in the evenings

at the workhouse, where she formed and superintended a large school;

and afterwards, when that school had been handed over to proper

teachers, she devoted the hours so released to the formation and

superintendence of a school for factory-girls, which was held in the

capacious chancel of the old Church of St. Nicholas. And after the

labours connected with the class were over, she would remain among

the girls for the purpose of friendly intercourse with them, which

was often worth more than all the class lessons. There were personal

communications with this one and with that; private advice to one,

some kindly inquiry to make of another, some domestic history to be

imparted by a third; for she was looked up to by these girls as a

counsellor and friend, as well as schoolmistress. She had often

visits also to pay to their homes; in one there would be sickness,

in another misfortune or bereavement; and everywhere was the good,

benevolent creature made welcome. Then, lastly, she would return to

her own poor, solitary apartments, late at night, after her long

day's labour of love. There was no cheerful, ready-lit fire to greet

her there, but only an empty, locked-up house, to which she merely

returned to sleep. She did all her own work, kindled her own fires,

made her own bed, cooked her own meals. For she went on living upon

her miserable pittance in a state of almost absolute poverty, and

yet of total unconcern as to her temporal support. Friends supplied

her occasionally with the necessaries of life, but she usually gave

away a considerable portion of these to people more destitute than

herself.

Picture Internet Text Archive.

She was now growing old; and the borough authorities at Yarmouth,

who knew very well that her self-imposed labours saved them the

expense of a schoolmaster and chaplain, (which they were now bound

by law to appoint,) made a proposal of an annual salary of £12 a

year! This miserable remuneration was, moreover, made in a manner

coarsely offensive to the shrinkingly sensitive woman; for she had

preserved a delicacy and pure-mindedness throughout her life-long

labours which, very probably, these Yarmouth bloaters could not

comprehend. She shrank from becoming the salaried official of the

corporation, and bartering for money those labours which had,

throughout, been labours of love.

"Here lies the objection," she said,

"which oppresses me: I have

found voluntary instruction, on my part, to have been attended with

great advantage; and I am apprehensive that, in receiving payment,

my labours may be less acceptable. I fear, also, that my mind would

be fettered by pecuniary payment, and the whole work upset. To try

the experiment, which might injure the thing I live and breathe for,

seems like applying a knife to your child's throat to know if it

will cut . . . . Were you so angry,"

—she is writing in answer to the

wife of one of the magistrates, who said she and her husband would

"feel angry and hurt" if Sarah Martin did not accept the

proposal,—

"were were you so angry as that I could not meet you, a

merciful God and a good conscience would preserve my peace; when, if

I ventured on what I believed would be prejudicial to the prisoners,

God would frown upon me, and my conscience too, and these would

follow me everywhere. As for my circumstances, I have not a wish

ungratified, and am more than content."

But the jail committee savagely intimated to the high-souled woman:

"If we permit you to visit the prison, you must submit to our

terms;" so she had no alternative but to give up her noble

labours altogether, which she would not do, or receive the miserable

pittance of a "salary" which they proffered her. And for two more

years she lived on, in the receipt of her official salary of £12 per

annum,—the acknowledgment of the Yarmouth Corporation for her

services as jail chaplain and schoolmaster!

In the winter of 1842, when she had reached her fifty-second year,

her health began seriously to fail, but she nevertheless continued

her daily visits to the jail,—"the home," she says, "of my first

interest and pleasure,"—until the 17th of April, 1843, when she

ceased her visits. She was now thoroughly disabled; but her mind

beamed out with unusual brilliancy, like the flickering taper before

it finally expires. She resumed the exercise of a talent which she

had occasionally practised during her few moments of leisure,—that

of writing sacred poetry. In one of these, speaking of herself on

her sick-bed, she says:

|

I seem to lie

So near the heavenly portals bright,

I catch the streaming rays that fly

From eternity's own light. |

Her song was always full of praise and gratitude. As artistic

creations, they may not excite admiration in this highly critical

age; but never were verses written truer in spirit, or fuller of

Christian love. Her whole life was a noble poem,—full also of true

practical wisdom. Her life was a glorious comment upon her own

words:—

|

The high desire that others may be blest

Savours of heaven. |

She struggled against fatal disease for many months, suffering great

agony, which was partially relieved by opiates. Her end drew nigh.

She asked her nurse for an opiate to still her racking torture. The

nurse told her that she thought the time of her departure had come. Clasping her hands, the dying Sister of Mercy exclaimed, "Thank God!

thank God!" And these were her last words. She died on the 15th of

October, 1843, and was buried at Caister, by the side of her

grandmother. A small tombstone, bearing a simple inscription,

written by herself, marks her resting-place; and, though the tablet

is silent as to her virtues, they will not be forgotten:—

|

Only the actions of the just

Smell sweet, and blossom in the dust. |

――――♦――――

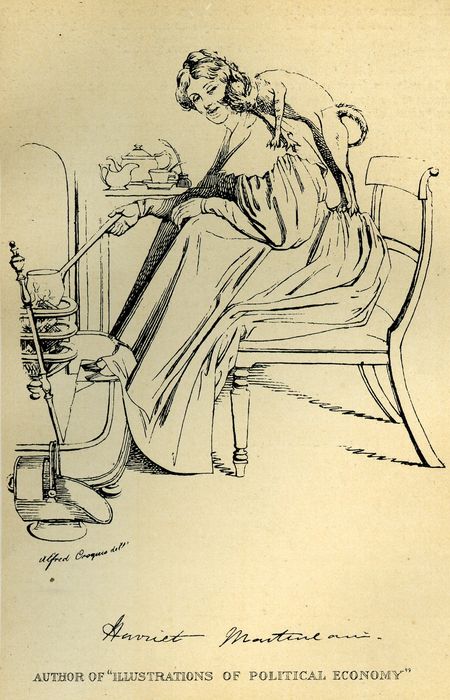

HARRIET MARTINEAU.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876): English

auther

and journalist.

Picture Internet Text Archive.

HARRIET

MARTINEAU is one of

the ablest and most vigorous of our living prose-writers. We cannot

call to mind any woman of modern or of past times, who has produced

a larger number and variety of solid, instructive, and interesting

books. She has written well on political economy, on history, on

foreign travel, on psychology, and on education; she has produced

many clever tales and novels; her books for children and for men are

alike good. She has been a copious contributor to the monthly and

quarterly reviews, and she is at present understood to be a regular

writer of leading articles for one of the best-conducted of our

morning daily papers. Her life has been one of hard work, and she

seems to work for the love of it, as well as for love of her kind. Even when laid on her bed by sickness, she went on writing, as if it

had become habitual to her, and then produced one of her most

delightful books, her "Life in the Sick-room."

Miss Martineau is a woman with a manly heart and head. In saying

this, we neither desire to cast a reflection on the sex to which she

belongs, nor upon herself. It would be well for women generally, did

they cultivate as she has done the spirit of self-help and

self-reliance. We believe it would tend to their greater usefulness

as well as happiness, and render them more efficient co-operators

with men in all the relations of life. In ordinary cases, unmarried

daughters are a burden in a "genteel" family of slender means; but

in Miss Martineau's case, she has throughout been a mainstay of

support to herself and family. Her father was a manufacturer at

Norwich, descended from a French refugee family,—French Protestants

having settled down there in considerable numbers after the

Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Commercial embarrassments having

overtaken the Martineaus, the sons and daughters were under the

necessity of bestirring themselves in aid of their family, which

they did, honourably and successfully. Miss Martineau, who had first

taken to writing as a recreation, afterwards followed it as a

pursuit and a profession; and in so doing she realized a competency. What was more, she carefully cherished her independence as a writer;

and when, overtaken by illness, her political friends, then in

power, bestirred themselves to help her, and, in 1840, obtained for

her the offer of a considerable government pension,—with a

conscientious and high-minded feeling, which in these modern times

finds few if any imitators, she declined to receive it,—holding it

to be wrong that she, a political writer, should receive a pension

which was not offered by the people, but by a government which, in

her opinion, did not represent the people. She sincerely preferred

retaining her independence and entire freedom of speech with respect

to government and all its affairs,—a decision which, however much it

may be at variance with our ideas of worldly prudence, we cannot but

respect and admire. More recently, also, she has displayed her force

of character in another direction; we mean by the publication, in

conjunction with Mr. Atkinson, of the "Letters on Man's

Development," &c. [p.500] With her views, as set forth in that book, we have

no sympathy; and we cannot but deplore, in common with her numerous

friends, that she was so ill-advised as to publish it. Nevertheless,

it was a thoroughly honest act on her part: done at the risk of her

popularity, reputation, and good name. She had arrived at

conclusions opposed to those generally entertained on certain

points; and as a writer, she conceived that the "cause of truth"

required that she should make a clean breast of it. Here, we think,

she committed a grievous mistake; for it can form no part of the

duty of any public writer to publish whatever crude notions may get

uppermost in her head. The error has, however, been committed; and

we merely allude to it here as furnishing a striking illustration of

Miss Martineau's character; somewhat similar to her defence of

Mesmerism in the Athenæum, when scarcely a voice, except that of

Dr. Elliotson, had been raised in its favour.

Miss Martineau displayed reflective powers at an early age. Possibly

her deafness, to which she was subject as a child, by shutting her

out to some extent from conversational intercourse with those about

her, encouraged habits of reflectiveness. She was a timid child, but

a quick and accurate observer. Her excellent work on "Household

Education" contains some autobiographical revelations of her

childhood, of a most curious and interesting character. One of

these—describing the feelings of wonder, and almost awe, with which

she contemplated a newly-born sister, when she herself was about

nine years of age—lets us into a remarkable phase of an observant

and thoughtful child's mind. Here is an account of her early

reading, from the same interesting book:—

"One Sunday afternoon, when I was seven years old, I was prevented

by illness from going to chapel,—a circumstance so rare, that I felt

very strange and listless. I did not go to the maid who was left in

the house, but lounged about the drawing-room, where, among other

books which the family had been reading, was one turned down upon

its face. It was a dull-looking octavo volume, thick, and bound in

calf, as untempting a book to the eyes of a child as could well be

seen: but, because it happened to be open, I took it up. The paper

was like skim-milk,—thin and blue, and the printing very ordinary. Moreover, I saw the word 'Argument,'—a very repulsive word to a

child. But my eye caught the word 'Satan;' and I instantly wanted

to know how anybody could argue about Satan. I saw that he fell

through Chaos; found the place in the poetry; and lived heart, mind,

and soul in Milton from that day till I was fourteen. I remember

nothing more of that Sunday, vivid as is my recollection of the

moment of plunging into Chaos: but I remember that from that time

till a young friend gave me a pocket edition of Milton, the

calf-bound volume was never to be found, because I had got it

somewhere: and that, for all those years, to me the universe moved

to Milton's music. I wonder how much of it I knew by heart,—enough

to be always repeating some of it to myself, with every change of

light and darkness, and sound and silence,—the moods of the day and

the seasons of the year. It was not my love of Milton which required

the forbearance of my parents,—except for my hiding the book, and

being often in an absent fit. It was because this luxury had made me

ravenous for more. I had a book in my pocket,—a book under my

pillow; and in my lap as I sat at meals; or rather on this last

occasion it was a newspaper. I used to purloin the daily paper

before dinner, and keep possession of it, with a painful sense of

the selfishness of the act; and with a daily pang of shame and

self-reproach, I slipped away from the table when the dessert was

set on, to read in another room. I devoured all Shakespeare, sitting

on a footstool, and reading by firelight, while the rest of the

family were still at table. I was incessantly wondering that this

was permitted; and intensely, though silently, grateful I was for

the impunity and the indulgence. It never extended to the omission

of any of my proper business. I learned my lessons; but it was with

the prospect of reading while I was brushing my hair at bedtime; and

many a time have I stood reading, with the brush suspended, till I

was far too cold to sleep. I made shirts with due diligence, being

fond of sewing; but it was with Goldsmith, or Thomson, or Milton

open on my lap, under my work, or bidden by the table, that I might

learn pages and cantos by heart. The event justified my parents in

their indulgence. I read more and more slowly, fewer and fewer

authors, and with ever-increasing seriousness and reflection, till I

became one of the slowest of readers, and a comparatively sparing

one."

Miss Martineau was born in June, 1802, and was already an author at

twenty years of age, in 1822, when she published her first little

volume, entitled "Devotional Exercises," for the use of young

persons. This book was soon followed by another of the same

description, entitled "Addresses, with Prayers and Hymns, for the

Use of Families and Schools." These works were of the "Orthodox

Unitarian" school, to which class of religionists the Martineau

family belonged. A number of minor publications followed, chiefly

little tales,—some of them intended for children; but the writer's

powers were growing apace, and when, in March, 1830, the Monthly

Repository published an advertisement by the Committee of the

British and Foreign Unitarian Association, offering premiums for the

production of three tracts, the object of which should be the

introduction and promotion of Christian Unitarianism amongst the

Roman Catholics, the Mahometans, and the Jews respectively, she

determined to compete for the prizes. Three distinct sets of judges

were appointed to adjudicate upon the essays sent in; and when their

decision had been come to, much to their own surprise, they found

that the same writer had won all the three prizes! Miss Martineau

was the successful essayist. It is not our business to enter upon

the subject of these essays, which were, perhaps, such as Miss

Martineau herself would not now write. They were, however, much

praised at the time they appeared, and exhibit a vigour of thought

and a finish of style remarkable in so young a writer. But, previous

to the production of these essays, Miss Martineau had been

practising her hand extensively in the pages of the Monthly

Repository, where we find her publishing "Essays on the Art of

Thinking," in 1829, with numerous criticisms on books, articles on

education, morals, and politics,—tales, chiefly religious, poems,

and parables.

|

|

|

The house in which Harriet Martineau

was born at Norwich, England.

Picture Internet Text Archive. |

But Miss Martineau's name did not come prominently before the public

as an author until the appearance of her "Illustrations of Political

Economy," which originated in the following way. A country

bookseller asked her to write for him some little work of fiction,

leaving the choice of subject to herself. About that time

machine-breaking riots were frequent in the manufacturing districts;

and as the subject would doubtless be a good deal discussed in the

Martineaus' home, the head of which was a manufacturer, an

interesting plot was at once suggested. "The Rioters," a story, was

the result; and it was followed by another in the following year,

entitled "The Turn Out." In these tales the author afterwards

confessed that she wrote Political Economy for the first time

without knowing it. Some time after, on reading Miss Marcet's

"Conversations on Political Economy," the idea occurred to her of

illustrating the principles of this science in a narrative form. She

repeatedly discussed the subject with her mother and brother, now

the Rev. James Martineau. She had neither authors nor booksellers to

consult; nevertheless she began her series, and wrote her "Life in

the Wilds," with which the series of proposed "Illustrations"

commenced. But the great difficulty was to find a publisher. No

bookseller would take the thing in hand; and many dissuaded her from

the project, prophesying that it was sure to fail. She endeavoured

to raise a subscription amongst her friends for the purpose of

publishing the first tale; but the subscription broke down. She

offered the tale to the Society for the Diffusion of Useful

Knowledge, but they rejected it at once. The work went "the round of

the trade," but no bookseller of any standing would entertain the

idea of publishing it. At last, after great difficulty, Miss

Martineau succeeded in inducing a comparatively unknown publisher to

usher the first "Illustration" into the world; but not before she

had surrendered to him those advantages which, in virtue of the

authorship, she ought to have been able to retain for herself. The

book appeared, and its extraordinary success surprised

everybody,—none more than the numerous publishers who had refused

it. Other and better tales followed, which sold in large editions;

and their merit was extensively recognized abroad, where they were

translated into French and German, and soon became almost as popular

as they were at home. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful

Knowledge afterwards applied to Miss Martineau to write a series of

tales illustrative of the Poor Laws; but they were not so successful

as her earlier tales, perhaps on account of the nature of the

subject. Nor had she afterwards any difficulty in finding publishers

for her numerous future works.

The list of successful books rejected by publishers would be a

curious one. Milton could with difficulty find a publisher for his

"Paradise Lost;" Crabbe's "Library," and other poems, were refused

by Dodsley, Beckett, and other London publishers, though Mr. Murray

many years after purchased the copyright of them for £3,000. Keats

could only get a publisher by the help of his friends. That

ever-wonderful book by De Foe, which is the charm of boyhood in all

lands, "Robinson Crusoe," was refused by one publisher after

another, and was at last sold to an obscure bookseller for a mere

trifle; whereas if De Foe could have published it at his own risk,

it would have made his fortune. Bulwer's "Pelham" was at first

rejected by Mr. Bentley's reader; but fortunately Mr. Bentley

himself read it and approved, by mere accident. The "Vestiges of

Creation," which has passed through ten large editions within a few

years, was repeatedly refused. Thackeray's "Vanity Fair" was

rejected by a magazine. "Mary Burton" and "Jane Eyre" went the

round of the trade. Howitt offered his "Book of the Seasons" to

successive publishers, and was at length so disgusted with their

repeated refusals, that he was on the point of pitching the

manuscript over London Bridge to sink or swim. Even "Uncle Tom's

Cabin" could scarcely find a publisher in London; but at last a

respectable printer got hold of a copy, and was so riveted by it

that he sat up half the night reading it, then woke up his wife, and

made her read it too; after which he determined to reprint it, and

his steam-engine and printing-presses were kept going by Uncle Tom

for many months after. It would thus appear that "the fathers," as

Southey calls the publishers, are not always a wise and far-sighted

race,—though the many failures of books accepted render them

sometimes preternaturally cautious, as in the case of Miss

Martineau's oft-rejected, but eventually highly successful

"Illustrations of Political Economy."

Harriet Martineau, by Daniel Maclise from Fraser's

Magazine's Gallery of

Illustrious Literary Characters. Picture the

Library of Congress.

The number of excellent works which Miss Martineau has since

produced has been very great, all of them indicating careful

preparation and study, close observation, and conscientious

thinking. The two able works, in three volumes each, on "Society in

America" and "Western Travel," contained the results of an

extensive tour made by her in the United States, with a view to the

improvement of her health, in the year 1834. These works are still

amongst the best of their kind, and have not been surpassed by later

writers in description of scenery, manners, and incidents of travel,

or in searching analyses of the social and domestic institutions of

the United States. A later work, of a somewhat similar character,

published by Miss Martineau in 1848, on "Eastern Life," contained

the results of her travels in the East; but it was nothing like so

well received as her previous books, jarring strongly upon the

religious sympathies and convictions of the majority of her readers;

and also, as we cannot but think, perverting and misrepresenting

many important events in Egyptian and Hebrew history. The

descriptive part of the work was, however, admirably executed; and

there are many passages in it which will bear comparison with even

the most graphic descriptions in the marvellous "Eothen."

Between the appearance of these works, numerous other books from her

pen were turned off, almost too numerous to mention. Among her minor

works we would particularly mention one comparatively little known,

entitled "How to Observe—Morals and Manners." In a small compass, it

exhibits a prodigious amount of observation, as well as of reading

and reflection. It is a model of composition, full of wisdom,

beauty, and quiet power. We recommend those who have not yet seen it

to read the book, and they will rise from its perusal with a better

idea of the moral and intellectual powers of Miss Martineau than we

can convey by any description of our own.

To Knights series of Guide-books she contributed "The Maid of All

Work," "The Lady's Maid," and "The Housemaid" (guides to service),

and "The Dressmaker" (guide to trade). She also found time to write

several good novels,—"Deerbrook," "The Hour and the Man," and four

volumes of "The Playfellow," a series of tales for children;

besides numerous able articles in Tait's Magazine and the

Westminster Review. When the People's Journal was

started, she became a copious contributor to it, and there published

the principal portion of her excellent work on "Household

Education." Long illness confined her to her bed and her room,

during which she wrote her "Life in the Sick-Room." She then lived

at Tynemouth, overlooking the sea, the coast, and the river, near

Shields, the scenery about which, as viewed from her chamber window,

she vividly describes in that book. Take, for instance, the

following charming passage:—

"Between my window and the sea is a green down, as green as any

field in Ireland; and on the nearer half of this down, hay-making

goes forward in its season. It slopes down to a hollow, where the

prior of old preserved his fish, there being sluices formerly at

either end, the one opening upon the river, and the other upon the

little haven below the Priory, whose ruins still crown the rock. From the prior's fish-pond the green down slopes upwards again to a

ridge; and on the slope are cows grazing all summer, and half-way

into the winter. Over the ridge I survey the harbour and all its

traffic, the view extending from the light-houses far to the right,

to a horizon of sea to the left. Beyond the harbour lies another

country, with, first, its sandy beach, where there are frequent

wrecks,—too interesting to an invalid,—and a fine stretch of rocky

shore to the left; and above the rocks a spreading heath, where I

watch troops of boys flying their kites: lovers and friends taking

their breezy walks on Sundays; the sportsman with his gun and dog;

and the washerwomen converging from the farm-houses on Saturday

evenings to carry their loads, in company, to the village on the yet

farther height. I see them, now talking in a cluster, as they walk

each with her white burden on her head, and now in file, as they

pass through the narrow lane; and finally, they part off on the

village green, each to some neighbouring house of the gentry. Behind

the village and the heath stretches the railroad, and I watch the

train triumphantly careering along the level road and puffing forth

its steam above hedges and groups of trees, and then labouring and

panting up the ascent till it is at last lost between two heights,

which at last bound my view. But on these heights are more

objects;—a windmill, now in motion and now at rest; a lime-kiln, in

a picturesque rocky field; an ancient church-tower, barely visible

in the morning, but conspicuous when the setting sun shines upon it;

a colliery, with its lofty wagon-way, and the self-moving wagons

running hither and thither, as if in pure wilfulness; and three or

four farms, at various degrees of ascent, whose yards, paddocks, and

dairies I am better acquainted with than their inhabitants would

believe possible. I know every stack of the one on the heights. Against the sky I see the stacking of corn and hay in the season,

and can detect the slicing away of the provender, with an accurate

eye, at the distance of several miles. I can follow the sociable

farmer in his summer-evening ride, pricking on in the lanes where he

is alone, in order to have more time for the unconscionable gossip

at the gate of the next farm-house, and for the second talk over the

paddock-fence of the next, or for the third or fourth before the

porch or over the wall where the resident farmer comes out, pipe in

mouth, and puffs away amidst his chat, till the wife appears, with a

shawl over her cap, to see what can detain him so long, and the

daughter follows, with her gown turned over her head (for it is now

chill evening), and at last the sociable horseman finds he must be

going, looks at his watch, and, with a gesture of surprise, turns

his steed down a steep, broken way to the beach, and canters home

over the sands, left hard and wet by the ebbing tide, the white

horse making his progress visible to me through the dusk."

While Miss Martineau was thus confined to her sick-room, gazing upon

such pictures as these, she heard at a distance of the wonders of

Mesmerism, how it had raised the palsied from their couch, cured the

epileptic, and soothed the nerves of the distracted. Having tried

every imaginable remedy, she determined to try this; and whether

from the potency of the remedy or the force of the patient's

imagination, certain it was that she was shortly after restored to

health. The cure has been variously accounted for, some avowing that

Nature had accomplished a crisis, and worked out a remedy for

herself; others, with Miss Martineau, insisting on the curative

power of the mesmeric passes. The subject was well discussed in the

Athenæum a few years since, by Miss Martineau on the one side, and

by the editor on the other; nor would it be an easy matter to sum up

the net results of the controversy. With all Miss Martineau's amount

of unbelief on some points, we cannot but regard her as extremely

credulous on others; and though she is liberal to the full on

general questions, there are topics on which she seems to us

(particularly in her book on "Man's Development") to be a

considerable bigot. It is quite possible to be bigoted against

bigotry, and to be superstitious in the very avoidance of

superstition. There was a good deal of force in the rough saying of

Luther, that the human mind is like a drunken peasant on horseback:

set him up on one side and he falls down on the other.

Miss Martineau's best book is the "History of England during the

Peace," published by Charles Knight. It is an extremely able,

painstaking, and, we think, impartial history of England since 1815. It exhibits the results of great reading and research, as well as of

accurate observation of life and manners. It is, unquestionably, the

best work of the kind; indeed, it may be said to stand by itself as

a history of our own times. Its execution does the author much

credit, and we trust she will long be spared to produce books of

equally unexceptionable quality and character.

――――♦――――

MRS. CHISHOLM.

Caroline Chisholm [née Jones], (1808–77):

English philanthropist and immigration administrator.

Picture internet Text Archive.

HOW innumerable

are the ways in which men and women can benefit their

fellow-creatures! There is not a human being, howsoever humble, but

can dispense help to others. It needs but the willing heart and the

ready hand. There is no want of opportunity for good works to those

who will desire to perform them. Where will you begin? With your

next-door neighbour? This is what John Pounds did. But if you wish

for a larger theatre for your philanthropy, you need have no

difficulty in finding it out. Most of the genuine philanthropic

workers have, however, been directed by no particular effort of

choice. The field of labour has lain in their way, and they have set

to work forthwith. It was the duty which lay nearest to them, and

they set about doing it. Many others had passed it by, and saw no

field for exertion there; but the discerning eye of the true lover

of men saw the work at a glance, and without the slightest hope or

desire for fame, without any expectation of public recognition or

eulogium, at once entered diligently and earnestly upon the

performance of the duty.

Such was the field of labour to which Mrs. Chisholm devoted herself. She was residing in Sydney, New South Wales, when she was distressed

by the sight of many young women arriving at that place without

guide or protector, without any idea of the wants of the colony, or

how to set about obtaining proper situations there; and often these

poor girls, on landing at Sydney, thousands of miles from home,

wandered about in the streets, homeless and destitute, for days

together. The heart of this good woman was moved by the sight,

and she could not fail to see the moral evils that might arise from

such a state of things. She forthwith resolved to place

herself in loco parentis to these helpless female emigrants,

and to shelter and protect them until they could be comfortably

provided for in the colony. She applied to the Governor for

the use of a government building, which was conceded to her, with

the cautious red-tape proviso, that Mrs. Chisholm "would guarantee

the government against any expense." This she did, and the

first "Female Emigrants' Home" was opened. She then appealed

to the public for support, and her appeal was liberally responded

to. She freely devoted her own time gratuitously to the

protection of her humbler sisters.

Great success attended the establishment of the Female

Emigrants' Home. It soon became crowded; and then she had to

devote herself to obtaining situations for them, to make room for

the fresh arrivals. As many of the female emigrants (a

considerable proportion of whom were Irish) were found unsuitable

for service in Sydney, but were well adapted for the rough country

work of the interior, Mrs. Chisholm proceeded to form branch

establishments in the principal towns throughout the colony, and

travelled into the interior with this view, taking a large number of

the young women with her. The great demand for female labour

which everywhere existed enabled her to effect their settlement

without much difficulty; and by forming committees of ladies, and

opening many country depots, or homes, she provided for the

settlement of many others who were to follow. Mrs. Chisholm's

exertions were cheerfully aided by the inhabitants of the country

districts; for she was doing them a great service, at the same time

that she was providing for the comfortable settlement of her young

protégées. In the first instance, she had to defray

their travelling expenses, but these were afterwards refunded; the

inhabitants of the districts providing supplies of the requisite

food. Where a District Emigrants' Home was established,

handbills were distributed throughout the neighbourhood, announcing

that "Persons requiring Servants are provided with them on applying

at this Institution." The young women were supported at the

Emigrants' Home until places were found for them. Shortly

after, Emigrants' Homes for men were in like manner established, and

Mrs. Chisholm's operations at length assumed a colonial importance;

and when the success of her labours began to be apparent, she had no

want of ardent co-operators and fellow-labourers. The

following is the account which she herself gave of the progress of

her work, before the Lords' Committee on Colonization, in the year

1848.

"I met with great assistance from

the country committees. The squatters and settlers were always

willing to give me conveyance for the people. I never wanted

for provisions of any kind; the country people always supplied them.

A gentleman who was examined before your Lordships the other day—Mr.

William Bradley, a native of the colony—called upon me, and told me

that he approved of my views, and that, if I required anything in

carrying my country plan into operation, I might draw upon him for

money, provisions, horses, or indeed anything that I required.

I had no necessity to draw upon him for a sixpence, the people met

my efforts so readily; but it was a great comfort for me at the time

to be thus supported. I was never put to any expense in

removing the people, except what was unavoidable. At public

inns the females were sheltered, and I was provisioned myself,

without any charge: my personal expenses at inns during my seven

years' service amounted only to £1 18s. 6d. My efforts,

however, were in various ways attended with considerable loss to

myself: absence from home increased my family expenditure, and the

clerical expense fell heavy upon me; in fact, in carrying on this

work, the pecuniary anxiety and risk were very great. I will

mention one impediment in the way of forwarding emigrants as engaged

servants into the interior: numbers of the masters were afraid, if

they advanced the money for their conveyance by the steamers, &c.,

they would never reach their stations. I met this

difficulty,—advanced the money; confiding in the good feeling of the

man that he would keep to his agreement, and in the principle of the

master that he would repay me. It is most gratifying to me to

state, that although in hundreds of cases the masters were then

strangers to me, I only lost throughout £16 by casualties.

Sometimes I have paid as much as £40 for steamers and land

conveyance.

"My object was always to get one placed. I never

attempted more than one at first. Having succeeded in getting

one female servant in a neighbourhood, I used to leave the feeling

to spread. The first thing that gave me the idea that I could

work in this manner was this: with some persuasion I induced a man

to take a servant, who said that it would be making a fine lady of

his wife. However, I spoke to him and told him the years his

wife had been labouring for him; this had the desired effect.

The following morning I was told by a neighbouring settler: 'You are

quite upsetting the settlement, Mrs. Chisholm; my wife is uncommonly

cross this morning; she says she is as good as her neighbour, and

she must have a servant; and I think she has as much right to one.'

It was amongst that class that the girls eventually married best.

If they married one of the sons, the father and mother would be

thankful; if not, they would be protected as members of the family.

They slept in the same room with their own daughters.

"One of the most serious impediments I met with in

transacting business in the country, was the application made for

wives. Men came to me and said, 'Do make it known in Sidney

what miserable men we are; do send wives to us.' The shepherds

would leave their sheep, and would come for miles with the greatest

earnestness for the purpose.

"I never did make a match, and I told them that I could not

do anything of the kind; but the men used to say, 'I know that, Mrs.

Chisholm, but it is quite right that you should know how very

thankful we shall be;' and they would offer to pay the expense of

conveyance, &c. I merely mention this to show the demand made

for wives in the interior.

"Even up to this date they are writing to me, and begging

that I will get their friends and relations to go. I am

constantly receiving letters from them; they say that, 'If my sister

was here, she would do so well.' Certainly I should not feel

the interest I do in female emigration, if I did not look beyond

providing families with female servants; if I did not know how much

they are required as wives, and how much moral good may be done in

this way."

For six years Mrs. Chisholm was engaged in this admirable

work, travelling many hundred miles to form branch committees and

depots, sometimes convoying with her out of Sydney as many as one

hundred and fifty females at one time. During that period she

succeeded in settling, throughout the colony, not fewer than eleven

thousand immigrants of both sexes, and doing the work which ought

properly to have been done by the colonial government. She

endeavoured to induce the government to take upon itself the

management and superintendence of the office for the settlement of

emigrants which she established in Sydney, but without effect.

The governor and the government emigration agent gave her great

praise, and sent home reports glowing with gratitude for her

philanthropic exertions in aid of the friendless emigrants; but they

provided her with no substantial aid, confining themselves to empty

words. The noble woman persevered with her work, not at all

disheartened by the result of her repeated applications.

At length Mrs. Chisholm returned to England,—not to suspend

her operations, but to extend them. Having planted her Local

Committees and Emigrants' Homes all over the colony, where they are

carefully superintended by the inhabitants of the several districts,

she could venture to leave them and visit England with another noble

purpose in view. Having provided the machinery for locating

and settling emigrants on their arrival in New South Wales, she

desired to rouse the mother country to send out its surplus

labourers, its unemployed or half-employed, or greatly-underpaid

women, to a country where they would be made welcome, and experience

no difficulty in securing at least the means of comfort and physical

well-being.

The most recent scheme which Mrs. Chisholm has originated, in

connection with the same movement, is the Family Colonization Loan

Society, whose object it is to aid poor and struggling families to

emigrate, by advancing small loans for the purpose, to be afterwards

repaid by them after reaching the colony; and also to effect the

reunion of the separated members of families—parents and children,

brothers and sisters, wives and husbands—in the Australian colonies,

by the same means. For instance, by means of this society,

servant-girls in Australia may remit through its agents their weekly

contributions of two shillings towards the emigration of their

parents, or for their support at home. Assistance is also

given by the society in enabling parties to trace out and

communicate with their relatives who have emigrated, and in other

ways to keep up family relationships and restore domestic ties.

And it is matter of gratification to know that the emigrants sent

out by Mrs. Chisholm are more eagerly sought after and better liked

in the colony than any that enter it. One of the notable

features of these detachments of emigrants is this, that they are

arranged into groups, each member of which is, to a certain extent,

responsible for every other, no one being admitted except after due

inquiry. Thus all immoral contamination is avoided, and a high

standard of character is maintained, while a kind of family

relationship is established among the members of the several groups.

The practical good which Mrs. Chisholm is effecting, by her

unwearied exertions in this cause, can scarcely be computed.

She is the happy means of introducing many worthy and industrious

individuals to positions of competency and independence; and is

engaged, in the most effective way, in extending the influence of

civilization and Christian liberty to the remote ends of the earth.

What reward she may meet with among men maybe of small moment to

her, but of her greatest reward she is certain.

At one of the public meetings of emigrants in London, the

Earl of Shaftesbury expressed his cordial admiration of the

intelligent zeal and indefatigable exertions of Mrs. Chisholm.

The audience, said he, had probably heard something of Bloomerism,

the highest order of which Mrs. Chisholm had attained; for she had

the heart of a woman, and the understanding of a man. He

wished her "God speed," and prayed that she might be made more and

more instrumental in carrying out her great and beneficent purposes.

To which we add a hearty Amen! [p.517]

THE END.

Cambridge: Stereotyped and Primed by Welch, Bigelow,

& Co. |