|

[Previous Page]

FRANCIS JEFFREY.

SOME thirty years

since, we happened to visit the High Courts of Session, held in

Edinburgh, in the purlieus of the old Scotch Parliament-House.

These are the chief law courts of Scotland; and though they are

always objects of interest to a visitor, they were perhaps more so

at that time than they are now, in consequence of their being then

professionally frequented by several men of world-wide reputation.

We remember well the striking entrance to those courts; they

occupy one side of a square, opposite to the old cathedral church of

St. Giles's where Jenny Geddes initiated the great Rebellion of two

centuries back, by hurling her "cuttystool" at the head of the

officiating bishop, on his proposing to read the collect for the

day. "Diel colic the wame o' thee!" shouted Jenny, as she

hurled her stool at the bishop; and from that point the Revolution

began. John Knox, at an earlier period, used to deliver his

thrilling harangues in the same church; and in the space now forming

the square—which was used as a cemetery previous to the

Reformation—the mortal remains of that undaunted reformer were laid;

of whom the Regent Murray said, as he was lowered into his grave,

"There lies one who never feared the face of man." Another

portion of the square was formerly occupied by the old jail or Tolbooth of Edinburgh, celebrated throughout the world by Scott's

novel of "The Heart of Mid-Lothian." [p.137]

But it had been demolished some years before the period of our

visit.

Entering the courts by a door in the southwest corner of the

square, and crossing a spacious vestibule, we passed through a pair

of folding doors, and found ourselves in the famous

Parliament-House. It is a noble hall, upwards of one hundred

and twenty feet long, and about fifty wide. Its lofty roof is

oak, arched with gilt pendants, in the style of Westminster Hall.

This was the place in which the Scottish Parliament held its

sittings for about seventy years previous to the Union. It was

in a bustle, as it usually is during the sittings of the court, with

advocates promenading in their wigs and gowns; writers (Anglice

solicitors), with their blue and red bags crammed with bundles of

legal documents, scudding hither and thither; litigants, with

anxious countenances, collected in groups, anxiously discussing the

progress of their "case;" whilst above the din and hum which filled

the hall there occasionally rose the loud voice of the criers,

summoning the counsel in the different causes to appear before their

lordships.

All the courts open into this hall, and we entered one of

these; we think it was the Justiciary Court. We have no

recollection of the cause that was being tried; some petty

horse-warranty affair or other, about which a great deal of clever

sarcasm and eloquence was displayed. But though we have

forgotten the cause that was tried, we have not forgotten the

pleader. He rose immediately after his burly opponent had

seated himself,—Patrick Robertson, for a long time the wit of the

Parliament-House,—the author of a book of poems, published a few

years ago, full of gravity, but without poetry,—afterwards Lord

Robertson. The advocate who rose to reply was a man the very

opposite in feature, form, and temperament to Patrick Robertson.

A little, slender, dark-eyed man, of a highly intellectual

appearance; his head was small,—indeed, the opponents of phrenology

have asserted that his head was so small, that it was enough of

itself to overthrow that science,—but then it was exquisitely

formed, the organs were beautifully balanced, the bulk of the brain

lay over the forehead, and the outline was such as to give one the

impression of the finest possible organization. He wore no

wig; and his black hair was brushed straight up from his beautiful

forehead.

When he rose to his feet, the hum of the court was stilled

into silence; and one who accompanied us said, "You see that little

man there going to speak?" "Yes." "That's FRANCIS

JEFFREY, of the Edinburgh Review."

And Jeffrey went on with his speech in a high-keyed, sharp, clear,

and acute strain, not rising into eloquence, but running on in a

smart and copious, yet somewhat precise manner: indeed, one might

have denominated his style of speech and of argument as a little

finical; yet it was unusually complete and highly finished, like

everything else that he did.

But there was in the same court that day one whose reputation

and whose genius infinitely transcended Jeffrey's, great though

these may have been. Sitting immediately under the Lord

President, at the clerk's table, were two men, one on each side,—the

clerks of the Court of Session. "You see that man at the table

there,—the one with the white hair and the overhanging brow?"

"Yes, I see two; they have both white hair, and are both

heavy-browed." "Yes; but I mean the one to the Lord

President's right,—immediately before Patrick Robertson there."

"The one with his head stooping over his papers, writing?"

"Yes: see, he is now rising up, and going across the room." "I

see him,—surely I know that face; I must have seen the man before."

"You may have seen the portrait of him often enough,—it is SIR

WALTER SCOTT!" In

a moment we recognized the Great Wizard of the North, whose magical

pen had quickened into life the long dead and buried past, and

created shapes of magical beauty by the aid of his wonderful

fancy,—the greatest literary celebrity of the age! His face,

as we saw it then, presented but few indications of those remarkable

intellectual powers, which might almost be said to blaze in

the features of Jeffrey. It was heavy, solid, lourd,

and homely,—somewhat like the face of a country-bred farmer's man,

grown old in harness, and rather "back" with his rent. He

limped across the court to one of the advocates or writers to the

signet, to whom he delivered a paper, and then returned to his seat.

The terrible crash of Sir Walter Scott's fortunes had occurred,

through the failure of his publisher, but a few years before; and

here was the hard-working man, still toiling at his post of clerk of

court during the day,—to enter upon his laborious literary labours

on returning home,—with the view of desperately retrieving the loss

of his fortune and estate.

One other man we may mention,—then a comparatively young

advocate in good business. His eye, of all his features,

struck us the most. Never did we see a more beautiful,

piercing eye before. Keen, black, and penetrating, it seemed

to look through you. Once afterwards, we encountered the eye

in Princes' Street, and recognized the man on the instant. It

was Henry Cockburn, the author of the "Life of Jeffrey." He

had the look of a man of genius; and was long afterwards known as a

highly acute and able lawyer. But he had never before done

anything in literature that we know of, until he wrote the life of

his friend Jeffrey; yet we mistake much if it do not take its place

among the best standard biographies of our time. We should not

be surprised if, like Boswell's Johnson, it were read when the books

of the author whose life is commemorated are allowed to lie on the

shelf.

Not that there is any vivid interest in Jeffrey's life; happy

and prosperous people have usually little history. Life flows

on in a smooth current; everything succeeds with them; they gather

wealth and fame with years, and die full of honours, which are

recorded on a mausoleum. But certainly there was about the

life of Jeffrey—even independently of the literary merits of Lord

Cockburn's portraiture of him—much that is instructive, interesting,

and delightful.

Jeffrey was a man full of bonhomie. He was an honest-minded,

independent man; a most industrious, hard-working, and perseverant

man; and, withal, a genuinely-loving man. But above all, he was the

founder of the "Edinburgh Review." This was the great event of his

life. By means of that eminently able organ of opinion, he elevated

criticism into a magistrature. He invested it with dignity, and

administered it like a judge, according to certain laws. He became

an oracle of taste in poetry, literature, and art. He did not merely

follow the literary fashion of the day, but he directed it, and for

many years presided over the highest critical organ in the country. Yet it will be confessed, that, if we look into the collected

edition of his works, they have comparatively little interest for

us. Even the most effective criticism is necessarily of an ephemeral

character. Like a thrilling Parliamentary speech, its chief interest

consists in its appropriateness to the time, the circumstances, and

the audience to whom it is addressed. At best, literary criticism is

but a clever and discriminating judgment upon books. The books so

criticised are now either dead and forgotten, or they have secured a

footing, and live on independent of all criticism. Yet criticism is

not without its value, as Jeffrey and his fellow-labourers amply

proved.

The leading incidents of Francis Jeffrey's life

are soon told. He was born in Charles Street, George's Square,

in the Old Town of Edinburgh, on the 22d of October, 1773. His

father was a depute clerk, in the Court of Session. His mother

was an amiable, intelligent woman, who died when Francis was but a

boy. The youth was educated at the Edinburgh High School,

where he remained for six years. Here is an incident of his

boyhood:—

"One day in the winter of 1786-87, he was standing in the High

Street, staring at a man whose appearance struck him; a person

standing at a shop door tapped him on the shoulder, and said, 'Ay, laddie! ye may weel

look at that man! that's ROBERT BURNS.' He never saw Burns

again."

From Edinburgh High School, Jeffrey proceeded to Glasgow University,

where he studied with distinction during two sessions. In the

"Historical and Critical Club," he astonished the members by the

force and acuteness of his criticisms on the essays submitted for

discussion. Thus early did the peculiar bent of his mind display

itself. He worked very hard,—was a systematic student,—took copious

notes, cast into his own forms of expression, of all the lectures,—and read largely on all subjects. He returned to Edinburgh, and

attended the law classes there in the two sessions of 1789–91, still

studying and composing essays on various subjects, but chiefly on

life and its philosophy.

"It was about this time (1790 or 1791) that he had the honour of

assisting to carry the biographer of Johnson, in a state of great

intoxication, to bed. For this, he was rewarded next morning by Mr.

Boswell, who had learned who his bearers had been, clapping his

head, and telling him that he was a very promising lad, and that,

'If you go on as you've begun, you may live to be a Bozzy yourself

yet.'"

He next went to Oxford to study, and remained there for a season,

but he never entered fully into the life of the place, and evidently

detested it. He did not find a single genial companion. He says of

the meetings of the students, "O these blank parties!—the

quintessence of insipidity,—the conversation dying from lip to

lip,—every countenance lengthening and obscuring in the shade of

mutual lassitude,—the stifled yawn contending with the affected

smile one every cheek,—and the languor and stupidity of the party

gathering and thickening every instant, by the mutual contagion of

embarrassment and disgust . . . . In the name of heaven, what do such beings

conceive to be the order and use of society? To them, it is no

source of enjoyment; and there cannot be a more complete abuse of

time, mind, and fruit." He detests the law, too. "This law," he

says, "is vile work. I wish I had been born a piper." There was only

one thing that he hoped to learn at Oxford, and that was the English

pronunciation. And he certainly succeeded in acquiring it after a

sort, but he never spoke it as an Englishman is wont to do. As Lord

Holland said of him afterwards, "He lost the broad Scotch at Oxford,

but he gained only the narrow English in its place."

He returned to Edinburgh in July, 1792, and again attended the law

lectures there. He joined the Speculative Society, then numbering

among its active members many afterwards highly celebrated

men,—Scott, Brougham, Grant (afterwards Lord Glenelg), Petty

(afterwards Marquis of Lansdowne), Francis Horner, and others. Jeffrey distinguished himself by several admirable papers which he

read before the society; and also by the part which he took in the

discussions. But, like many susceptible young minds, at this time,

he was haunted by fits of despondency. He could not take the world

by storm: few knew that he lived. How was he to distinguish himself?

He would be a Poet! Writing to his sister about this time, he said,

"I feel I shall never be a great man, unless it be as a

Poet!" But

afterwards he says more calmly, "My poetry does not improve; I think

it is growing worse every week. If I could find the heart to abandon

it, I believe I should be the better for it." He nevertheless went

on writing tragedies, love poems, sonnets, odes, and such like; but

they never saw the light. Once, indeed, he went so far as to leave a

poem with a bookseller, to be published,—and fled to the country;

but finding some obstacle had occurred, he returned, recovered the

manuscript,—rejoicing that he had been saved,—and never repeated so

perilous an experiment.

In 1794, Jeffrey was called to the Scotch bar. The times were sick

and out of joint. The French Revolution was afoot, and its violence

tended to drive some men sternly back upon the past, and to impel

others wildly forward into the future. Some took a middle course;

and while they discountenanced all violent change, sought after

constitutional progress and social improvement. To this middle

party, Jeffrey early attached himself. He joined himself to the

Whigs, though to do so at that day was to erect a lofty barrier in

the way of his own success. Yet he did so, courageously and

resolutely; and he held to his course. He had several noble allies;

among whom may be named Brougham, Horner, and Erskine (the brother

of the Lord Chancellor). At the bar, Jeffrey got on very slowly. Very few fees came in, and these were chiefly from his father's

connections. He began to despair of success, and even went to

London with the object of becoming a literary "grub." He was

furnished with letters to authors, newspaper editors, and

publishers. But, fortunately, they received him coldly, and he

returned to Edinburgh to reoccupy himself with essay writing,

translating from the Greek, and waiting for clients. The clients did

not come yet, and he began seriously to despair of ever achieving

success in his profession.

"I cannot help," he wrote at this time, "looking upon a slow,

obscure, and philosophical starvation at the Scotch bar, as a

destiny not to be submitted to. There are some moments when I think

I could sell myself to the minister or to the devil, in order to get

above these necessities." He also entertained the idea of trying the

English bar, or going out to India, like so many other young

Scotchmen of his day. He had now been five years at the bar, and

could not yet, as the country saying goes, "make saut to his kail." In the seventh year of his practice, he says, "My profession has

never yet brought me £100 a year." But this is the history of nearly

all young men in their first ascent of the steeps of professional

enterprise.

Yet Jeffrey's poor prospects did not prevent him falling in love

with a girl as poor as himself, and he married her. The young lady

was, however, of good family: she was the daughter of Dr. Nelson,

Professor of Church History at St. Andrew's. The young pair settled

down in Buccleuch Place, in the Old Town; and the biographer informs

us that "his own study was only made comfortable at the cost of £7

18s.; the, banqueting-hall rose to £13 8s.; and the drawing-room

actually rose to £22 19s." He made a careful inventory of all the

costs of furnishing, which is still preserved.

But his marriage seemed to have been the starting-point of

Jeffrey's success. He devoted himself sedulously to his profession. Clients appeared in greater numbers; he began to be looked upon as a

rising man; and when once the ball is fairly set a-rolling, it goes

on comparatively easy. Shortly after, the famous Edinburgh Review

was projected by himself and Sydney Smith, though the merit of

suggesting the work is undoubtedly due to the latter. Sydney Smith's

account of its origin is this: "One day we happened to meet in the

eighth or ninth story, or flat, in Buccleuch Place, the elevated

residence of the then Mr. Jeffrey. I proposed that we should set up

a Review; this was acceded to with acclamation. I was appointed

editor, and remained long enough in Edinburgh to edit the first

number of the Edinburgh Review." But Jeffrey's aptness for editorial

work, his peculiar critical ability, together with the fact of his

being the only settled man of the lot permanently located in

Edinburgh, soon led to his undertaking the entire control of the

Review, and furnishing the principal part of the writing. The first

number of the Edinburgh Review appeared in October, 1802, and the

effect produced by it was almost electrical. It was so bold, so

novel, so spirited and able,—so unlike anything of the kind that had

heretofore appeared,—that its success from the first was decided. It

afforded a gratifying proof of the existence of liberal feeling in a

part of the country where before one dull, dead, uniform level of

slavish obsequiency had prevailed. It gave a voice to the dormant

feeling of independence which nevertheless still survived. The

effect upon public opinion was most wholesome, and the influence of

the Review went on increasing from year to year. Horner, Sydney

Smith, and Brougham soon left Edinburgh for England, to enter upon

public life; but Jeffrey stood by the Review, and continued its

main-stay. When Horner left Edinburgh, he made a present of his bar

wig to Jeffrey, who "hoped that in time it would attract fees" besides admiration. But Jeffrey never liked to wear a wig, and soon

abandoned it for his own fine black hair. Among the greatest bores

which he experienced was attending Scotch appeals in the House of

Lords in London, when he had to sit under a great load of serge and

horsehair, perhaps in the very height of the dog-days

His practice increased, while his fame in connection with the Review

spread his name abroad. His severe handling of many of the writers

of the day, brought down upon him a good deal of bitter speech,—such

as Lord Byron's "English Bards and Scotch Reviewers." His severe

review of Moore's lascivious love poems brought him into collision

with that gentleman, and an innocuous duel was the consequence; but

after that they remained warm friends. There was little of interest

in Jeffrey's life for many years after this occurrence. It flowed on

in an equable and widening current of steady prosperity. His wife

died in 1805, and was sincerely lamented by him. The letter which he

wrote to his brother on the occasion is exceedingly beautiful, —full

of affectionate and deep feeling for the departed. "I took no

interest," he says, "in anything which had not some reference to

her. I had no enjoyment away from her, except in thinking what I

should have to tell or to show her on my return; and I have never

returned to her, after half a day's absence, without feeling my

heart throb and my eye brighten with all the ardour and anxiety of a

youthful passion. All the exertions I ever made in the world were

for her sake entirely. You know how indolent I was by nature, and

how regardless of reputation and fortune; but it was a delight to me

to lay these things at the feet of my darling, and to invest her

with some portion of the distinction she deserved, and to increase

the pride and vanity she felt for her husband, by accumulating these

public tests of his merit. She had so lively a relish for life, too,

and so unquenchable and unbroken a hope in the midst of protracted

illness and languor, that the stroke which cut it off forever

appears equally cruel and unnatural. Though familiar with sickness,

she seemed to have nothing to do with death. She always recovered so

rapidly, and was so cheerful and affectionate and playful, that it

scarcely entered into my imagination that there could be one

sickness from which she would not recover." But Jeffrey did not

remain single. A few years after, in 1813, we find him on his way to

the United States, to bring home his second wife,—a grand-niece of

the famous John Wilkes. He wooed and won her, and an admirable wife

she made him.

There are only a few other prominent landmarks in Jeffrey's career

which we would note in the midst of his prosperous life. In 1820 he

was elected Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow, and delivered

a noble speech on his installation. In 1829 he was elected Dean of

the Faculty of Advocates, a post of high honour in the profession.

On being elected, he gave up the editorship of the Review, after

superintending it for a period of twenty-seven years. In 1830 the

Whigs came into office, and Jeffrey was appointed Lord Advocate,—the

first law officer of the Crown for Scotland. This was the height of

his ambition. He could only climb a step higher, which he did a few

years later, when he was made a judge, and died Lord Jeffrey, in

January, 1850.

His friend and fellow-judge has admirably depicted Jeffrey as he

lived,—in his home life, which was beautiful, and in his public

career, which was honourable, useful, and meritorious. He was a most

affectionate man. In one of his letters,—and they are, perhaps, the

most charming portions of the work,—he says, "I am every hour more

convinced of the error of those who look for happiness in anything

but concentred and tranquil affection." His intellect was sharp and

bright,—not so powerful as keen. His knowledge was various rather

than profound. His taste was exquisite; his sense of honour very

fine; and his manner was full of gentleness and kindness. Withal, he

was an earnest, resolute man, whose heart glowed in the conflicts of

the world. In conclusion we may add, that Lord Jeffrey, in his

valuable life, has furnished a further illustration of what

honourable, persistent industry and application will do for a man in

this life; for it was mainly this that raised him from obscurity and

dependence to a position of affluence and worldly renown.

――――♦――――

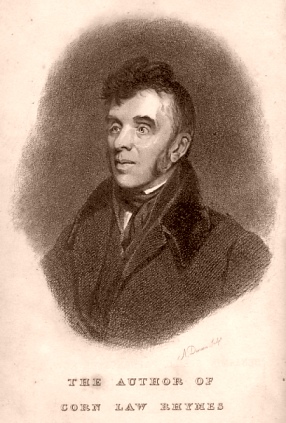

EBENEZER ELLIOTT.

Ebenezer Elliott (1781-1849)

Ironmaster, political activist and poet.

EBENEZER

ELLIOTT, the Sheffield

iron-merchant, a poet of no mean fame, was extensively known beyond

the bounds of his own locality as "the Corn-Law Rhymer." Though for

a time identified with a political movement, to which he consecrated

the service of his lyre, he had nevertheless the world-wide vision

of the true poet, who is of no sect nor party. Any one who reads his

poems will not fail to note how closely his soul was knit to

universal Nature —how his pulse beat in unison with her,—how deeply

he read and how truly he interpreted her meanings. With a heart

glowing for love of his kind, out of which indeed his poetry first

sprung, and with a passionate sense of wrongs inflicted upon the

suffering poor, which burst out in words of electric, almost

tremendous power, there was combined a tenderness and purity of

thought and feeling, and a love for Nature in all her moods, of the

most refined and beautiful character. In his scathing denunciations

of power misused, how terrible he is; but in his expression of

beauty, how sweet! Bitter and fierce though his rhymes are when his

subject is "the dirt-kings,—the tax-gorged lords of land," we see

that all his angry spirit is disarmed when he takes himself out to

breathe the fresh breath of the heavens, in the green lane, on the

open heath, or up among the wild mountains. There he takes Nature to

his bosom,—calls her by the sweetest of names, pours his soul out

before her, gives her his whole heart, and yields up to her his

manly adoration. You see this beautiful side of the poet's

character in his exquisite poems entitled "The Wonders of the Lane,"

"Come and Gone," "The Excursion," "The Dying Boy to the Sloe

Blossom," "Flowers for the Heart," "Don and Rother," and even in

"Win-hill," that most powerful of his odes. The utterance is

that of a man, but the heart is tender as that of a woman.

These exquisite little poems of Elliott, in their terseness and

vividness of expression, and their sweetness and delicacy of

execution, cannot fail to remind one of the kindred magical power

and genius of Robert Burns.

Elliott's life proved, what is still a disputed point, that

the cultivation of poetic tastes is perfectly compatible with

success in trade and commerce. It is a favourite dogma of some

men, that he who courts the Muses must necessarily be unfitted for

the practical business of life; and that to succeed in trade, a man

must live altogether for it, and never rise above the consideration

of its little details. This is, in our opinion, a notion at

variance with actual experience. Generally speaking, you will

find the successful literary man a man of industry, application,

steadiness, and sobriety. He must be a hard worker. He

must apply himself. He must economize time, and coin it into

sterling thought, if not into sterling money. His habits tell

upon his whole character, and mould it into consistency. If he

be in business, he must be diligent to succeed in it; and his

intelligence gives him resources which to the ignorant man are

denied. It may not have been so in the last century, when the

literary man was a rara avis, a world's wonder, and was feted

and lionized until he became irretrievably spoilt; but now, when all

men have grown readers, and a host of men have become writers, the

literary man is no longer a novelty: he drags quietly along in the

social team, engages in business, succeeds, and economizes, just as

other men do, and generally to much better purpose than the

illiterate and the uncultivated. Some of the most successful

men in business, at the present day, are men who regularly wield the

pen in the intervals of their daily occupations,—some for

self-culture, others for pleasure, others because they have

something cheerful or instructive to utter to their fellow-men; and

shall we say that those men are less usefully employed than if they

had been cracking filberts over their wine, sleeping over a

newspaper, gadding at clubs, or engaging in the frivolity of evening

parties?

Ebenezer Elliott was a man who profitably applied his leisure

hours to the pursuit of literature, and while he succeeded in

business, he gained an eminent reputation as a poet. After a

long life spent in business, working his way up from the position of

a labouring man to that of an employer of labour, a capitalist, and

a merchant, he retired from active life, built a house on a little

estate of his own, and sat under his "vine and fig-tree" during the

declining years of his life; cheered by the prospect of a large

family of virtuous sons and daughters growing up around him in

happiness and usefulness.

We enjoyed the pleasure of a visit to this gifted man, at his

own fireside, little more than a month before his death. It

was one of the last lovely days of autumn, when the faint breath of

Summer was still lingering among the woods and fields, as if loath

to depart from the earth she had gladdened; the blackbird was still

piping his mellifluous song in the hedges and coppice, whose foliage

was tinted in purple, russet, and brown, with just enough of green

to give that perfect autumnal tint, so beautifully pictorial, but

impossible to paint in words. The beech-nuts were dropping

from the trees, and crackled under foot, and a rich, damp smell rose

from the decaying leaves by the road-side. After a short walk

through a lovely, undulating country, from the Darfield station of

the North Midland Railway, along one of the old Roman roads, so

common in that part of Yorkshire, and which leads into the famous

Watling Street, near the town of Pontefract, we reached the village

of Old Houghton, at the south end of which stands the curious Old

Hall,—an interesting relic of Middle-Age antiquity. Its

fantastic gable-end, projecting windows, quaint doorway, diamond

"quarrels," and its great size looming up in the twilight, with the

well-known repute which the house bears of being "haunted," made us

regard it with a strange, awe-like feeling: it seemed like a thing

not of this every-day world; indeed, the place breathes the very

atmosphere of the olden time, and a host of associations connected

with a most interesting period of old English history are called up

by its appearance. It reminds one of the fantastic old Tabard,

in Dickens's "Barnaby Rudge "(we think it is); and the resemblance

is strengthened by the fact of this Old Hall being now converted

into a modern public-house, the inscription of "Licensed to be drunk

on the premises," &c., being legibly written on a sign-board over

the fantastic old porch. "To what base uses," alas! do our old

country-houses come at last! Being open to the public, we

entered; and there we found a lot of the village labourers,

ploughmen, and delvers, engaged, in a boxed-off comer of the Old

Squire's Hall, drinking their Saturday night's quota of beer, amidst

a cloud of tobacco-smoke; while the mistress of the place, seated at

the tap in another corner of the apartment, was dealing out her

potations to all comers and purchasers. A huge black deer's

head and antlers projected from the wall, near the door, evidently

part of the antique furniture of the place; and we had a glimpse of

a fine broad stone staircase, winding up in one of the deep bays of

the hall, leading to the, state apartments above. Though

strongly tempted to seek a night's lodging in this haunted house, as

well as to explore the mysteries of the interior, we resisted the

desire, and set forward on our journey to the more inviting house of

the poet.

We reached Hargate, Hill, the house and home of Ebenezer

Elliott, in the dusk of the autumn evening. There was just

light enough to enable us to perceive that it was situated on a

pleasant height, near the hill-top, commanding an extensive prospect

of the undulating and finely-wooded country towards the south; on

the north stretched away an extensive tract of moorland, covered

with gorse-bushes. A nicely-kept flower-garden and grass-plot

lay before the door, with some of the last of the year's roses still

in bloom. We had a cordial welcome from the poet, his wife,

and two interesting daughters,—the other members of his large family

being settled in life for themselves,—two sons, clergymen, in the

West Indies, two in Sheffield, and others elsewhere. Elliott

looked the wan invalid that he was, pale and thin; and his hair was

nearly white. Age had deeply marked his features since last we

saw him; and, instead of the iron-framed, firm-voiced man we had

seen and heard in Palace Yard, London, some eleven years before, and

in his own town of Sheffield at a more recent date, he now seemed a

comparatively weak and feeble old man. An anxious expression

of face indicated that he had suffered much acute pain,—which indeed

was the case. After he had got rid of that subject, and begun

to converse about more general topics, his countenance brightened

up, and, under the stimulus of delightful converse, he became, as it

were, a new man. With all his physical weakness, we found that

his heart beat as warm and true as ever to the cause of human kind.

The old struggles of his life were passed in review, and fought over

again; and he displayed the same zeal and entertained the same

strong faith in the old cause which he had rhymed about so long

before it seized hold of the public mind. He mentioned, what I

had not before known, that the Sheffield Anti-Corn-Law Association

was the first to start the system of operations afterwards adopted

by the League, and that they first employed Paulton as a public

lecturer; but to Cobden he gave the praise of having popularized the

cause, knocked it into the public head by dint of sheer hard work

and strong practical sense, and to Cobden he still looked as the

great leader of the day,—one of the most advanced and influential

minds of his time. The patriotic struggle in Hungary had

enlisted his warmest sympathies; and he spoke of Kossuth as "cast in

the mould of the greatest heroes of antiquity." Of the Russian

Emperor he spoke as "that tremendous villain, Nicholas," and he

believed him to be so infatuated by his success in Hungary, that he

would not know where to stop, but would rush blindly to his ruin.

The conversation then led towards his occupations in this remote

country spot, whither he had retreated from the busy throng of men,

and the engrossing pursuits and anxieties of business. Here he said

he had given himself up to meditation and thought; nor had he been

idle with his pen either, having a volume of prose and poetry nearly

ready for publication. Strange to say, he spoke of his prose as the

better part of his writings, and, as be himself thought, much

superior to his poetry. But he is not the first instance of a great

writer who has been in error as to the comparative value of his own

works. On that question the world, and especially posterity, will

pronounce the true verdict.

He spoke with great interest of the beautiful scenery of the

neighbourhood, which had been a source to him of immense joy and

delight; of the two great old oaks, near the old Roman road, about a

mile to the north, under the shade of which the Wapontake formerly

assembled, and in the hollow of one of which, in more recent times,

Nevison the highwayman used to take shelter, but it was burnt down

in spite, after his execution, by a band of Gypsies; of the glorious

wooded country which stretched to the south,—Wentworth, Wharncliffe,

Conisborough, and the fine scenery of the Dearne and the Don; of the

many traditions which still lingered about the neighbourhood, and

which, he said, some Walter Scott, could he gather them up before

they died away, would make glow again with life and beauty.

"Did you see," he observed, "that curious Old Hall on your

way up? The terrible despot Wentworth, Lord Strafford, married

his third wife from that very house, and afterwards lived in it for

some time; and no wonder it is rumoured among the country folks as

'haunted;' for if it be true that unquiet, perturbed spirits have

power to wander over the earth, after the body to which they had

been bound is dead, his could never endure the peaceful rest of the

grave. After Wentworth's death it became the property of Sir

William Rhodes, a stout Presbyterian and Parliamentarian. When

the great civil war broke out, Rhodes took the field with his

tenantry, on the side of the Parliament, and the first encounter

between the two parties is said to have taken place only a few miles

to the north of Old Houghton. While Rhodes was at Tadcaster

with Sir Thomas Fairfax, Captain Grey (an ancestor of the present

Earl Grey), at the head of a body of about three hundred Royalist

horse, attacked the Old Hall, and, there being only some thirty

servants left to defend it, took the place and set fire to it,

destroying all that would burn. But Cromwell rode down the

cavaliers with his ploughmen at Marston Moor, not very far from here

either, and then Rhodes built the little chapel that you would see

still standing apart at the west end of the Hall, and established a

godly Presbyterian divine to minister there; forming a road from

thence to Driffield, about three miles off, to enable the

inhabitants of that place to reach it by a short and convenient

route. I forget how it happened," he continued, "I believe it

was by marriage,—but so it was, that the estate fell into the

possession, in these latter days, of Monckton Milnes, to whom it now

belongs. But as Monk Frystone was preferred as a family

residence, and was in a more thriving neighbourhood, the chief part

of the land about was sold to other proprietors, and only some three

holdings were retained, in virtue of which Mr. Milnes continues lord

of the manor, and is entitled to his third share of the moor or

waste lands in the neighbourhood, which may be reclaimed under

Enclosure Acts. But the Old Hall has been dismantled, and all

the fine old furniture and tapestry and paintings have been removed

down to the new house at Monk Frystone."

And then the conversation turned upon Monckton Milnes, his

fine poetry, and his "Life of Keats,"—on Keats, of whom Elliott

spoke in terms of glowing eulogy as that great "resurrectionized

Greek,"—on Southey, who had so kindly proffered his services in

advancing the interests of Elliott's two sons, the clergymen, whose

livings he obtained for them,—on Carlyle, whom he admired as one of

the greatest of living poets, though writing not in rhyme,—and on

Longfellow, whose "Evangeline" he had not yet seen, but longed to

read. And thus the evening stole on with delightful converse

in the heart of that quiet, happy family, the listeners recking not

that the lips of the eloquent speaker would soon be moist with the

dews of death. Shortly after the date of this visit, we sent

the poet a copy of "Evangeline," of which he observed, in a letter

written after a delighted perusal of it: "Longfellow is indeed a

poet, and he has done what I deemed an impossibility,—he has written

English hexameters, giving our mighty lyre a new string! When

Tennyson dies, he should read 'Evangeline' to Homer." Poor

Elliott! That task, if a possible one, be now his!

We cannot better conclude this brief sketch than by giving

the last lines which Elliott wrote, while autumn was yet lingering

round his dwelling, and the appearance of the robin red-breast near

the door augured the approach of winter. They were written at

the request of the poet's daughter (who was married only about a

fortnight before his death), to the air of "'Tis time this heart

should be unmoved":

|

"Thy notes, sweet Robin, soft as dew,

Heard soon or late, are dear to me;

To music I could bid adieu,

But not to thee.

"When from my eyes this life-full throng

Has past away, no more to be;

Then, Autumn's primrose, Robin's song,

Return to me." |

――――♦――――

GEORGE BORROW.

SINCE the

publication of "The Bible in Spain," a singularly interesting and

fascinating book, few English writers have excited so deep a

personal interest as George Borrow,—Gypsy George,—Don Giorgio,—the

Gypsy Hogarth. The writer projected so much of himself into

that book, as well as into his "Gypsies of Spain," his first

published work, and gave us such delightful glimpses of his own life

and experience, as keenly to whet our curiosity, and make us eagerly

long to know more about him.

Here was a travelling missionary of the Bible Society, who

knew all about Gypsy life and lingo, was familiar with the lowest

haunts of field thieves and mendicants, and up to all their

gibberish; a horse-sorcerer and whisperer, a student of pugilism

under Thurtell, and himself no mean practitioner in "the noble art

of self-defence," but withal a man of the most varied gifts and

accomplishments,—a philologist or "word-master," knowing nearly

every language in Europe and the East,—a racy and original writer,

with the force of Cobbett and the learning of Parr,—the translator

of the Bible, or parts of it, into Mantchou, Basque, Romany, or

gypsy-tongue, and many other languages, and of old Danish ballads

into English,—a person of fascinating conversation and of powerful

eloquence. Fancy these varied gifts embodied in a man standing six

feet two in his stocking-soles, his frame one of iron, his daring

and intrepidity unmatched, and you have placed before your mind's

eye George Borrow, the Bible Missionary,—the Gypsy Hogarth,—the

emissary of Exeter Hall,—the quondam pupil of Thurtell,—Lavengro,

the Word-master!

One wishes to know much of this extraordinary being.

What is his history? What has been his life? It must be full

of novel experiences, the like of which was never before written.

Well, he has written a book called "Lavengro," in which he proposes

to satisfy the public curiosity about himself, and to illustrate his

biography as "Scholar, Gypsy, and Priest." The book, however,

is not all fact; it is fact mixed liberally with fiction,—a kind of

poetic rhapsody; and yet it contains many graphic pictures of real

life,—life little known of, such as exists to this day among the

by-lanes and on the moors of England. One thing is obvious,

the book is thoroughly original, like all Mr. Borrow has written.

It smells of the green lanes and breezy downs,—of the field and the

tent; and his characters bear the tan of the sun and the marks of

the weather upon their faces. The book is not written as a

practised book-maker would write it; it is not pruned down to suit

current tastes. Borrow throws into it whatever he has picked

up on the highways and by-ways, garnishing it up with his own

imaginative spicery ad libitum, and there you have it,

Lavengro the Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest"! But the work is

not yet completed, seeing that he has only as yet treated us to the

two former parts of the character; "The Priest" is yet to come, and

then we shall see how it happened that Exeter Hall was enabled to

secure the services of this gifted missionary.

From his childhood George Borrow was a wanderer, and

doubtless his early associations and experiences gave their colour

to his future life. His father was a captain of militia about

the beginning of the present century, when the principal garrison

duties of the country were performed by that force. The

regiment was constantly moving about from place to place, and thus

England, Scotland, and Ireland passed as a panorama before the eyes

of the militia officer's son. He was born at East Dereham, in

Norfolk, when the regiment was lying there in 1803. Borrow

claims the honour of gentle birth, for his father was a Cornish

gentillatre, and by his mother he was descended from an old Huguenot

family, who were driven out of France at the Revocation of the Edict

of Nantes, and, like many other of their countrymen, settled down in

the neighbourhood of Norwich. Borrow the elder was a man of

courage, and though never in battle, he fought with his fists, and

vanquished "Big Ben Brain," in Hyde Park, a feat of which his son

thinks highly, and the more so, as Big Ben Brain, four months after

the event, "was champion of England, having vanquished the heroic

Johnson. Honour to Brain, who, at the end of four other

months, worn out by the dreadful blows which he had received in his

manly combats, expired in the arms of my father, who read the Bible

to him in his later moments,—Big Ben Brain." Such are the

son's own words in his autobiographic "Lavengro."

Borrow had one brother older than himself, an artist, a pupil

of Haydon, the historical painter. He died abroad in

comparative youth, but after he had given promise of excellency in

his profession. This elder brother was the father's

favourites; for George, when a child, was moody and reserved,—a

lover of nooks and retired corners, shunning society, and sitting

for hours together with his head upon his breast. But the

family were constantly wandering and shifting about, following the

quarters of the regiment, sometimes living in barracks, sometimes in

lodgings, and sometimes in camp. At a place called Pett, in

Sussex, they thus lived under canvas walls, and here the first

snake-charming incident in the child's life occurred:—

"It happened that my brother and

myself were playing one evening in a sandy lane, in the

neighbourhood of this Pett camp; our mother was at a slight

distance. All of a sudden a bright yellow, and, to my

infantine eye, beautiful and glorious object, made its appearance at

the top of the bank from between the thick quickset, and, gliding

down, began to move across the lane to the other side, like a line

of golden light. Uttering in a cry of pleasure, I sprang

forward, and seized it nearly by the middle. A strange

sensation of numbing coldness seemed to pervade my whole arm, which

surprised me the more, as the object, to the eye, appeared so warm

and sunlike. I did not drop it, however, but, holding it up,

looked at it intently, as its head dangled about a foot from my

hand. It made no resistance; I felt not even the slightest

struggle; but now my brother began to scream and shriek like one

possessed. 'O mother, mother!' said he, 'the viper! my brother

has a viper in his hand!' He then, like one frantic, made an

effort to snatch the creature away from me. The viper now

hissed amain, and raised its head, in which were eyes like hot

coals, menacing, not myself, but my brother. I dropped my

captive, for I saw my mother running towards me; and the reptile,

after standing for a moment nearly erect, and still hissing

furiously, made off, and disappeared. The whole scene is now

before me as vividly as if it occurred yesterday,—the gorgeous

viper, my poor, dear, frantic brother, my agitated parent, and a

frightened hen clucking under the bushes,—and yet I was not three

years old."

Borrow cites this as an instance of the power which some

persons possess of exercising an inherent power or fascination—call

it mesmeric, if you will—over certain creatures; and he afterwards

cites instances of the same kind, or the taming of wild horses by

the utterance of words or whispers, or by certain movements, which

seemed to have power over them.

Thus the family wandered through Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, and

Kent. At Hythe, the sight of a huge Danish skull, the

headpiece of some mighty old Scandinavian pirate, lying in the old

penthouse adjoining the village church, struck the boy's imagination

with awe; and, like the apparition of the viper in the sandy lane,

it dwelt in his mind, affording copious food for thought and wonder.

"An undefinable curiosity for all that is connected with the Danish

race began to pervade me; and if, long after, when I became a

student, I devoted myself, with peculiar zest, to Danish lore, and

the acquirement of the old Norse and its dialects, I can only

explain the matter by the early impression received at Hythe from

the tale of the old sexton beneath the penthouse, and the sight of

the huge Danish skull."

Borrow's acquaintance with books began with the most

fascinating of all boys' books,—one which has preserved its

popularity undiminished for more than a hundred years, and, while

boys' nature remains as now, will hold a high place in English

literature,—the entrancing, fascinating, delightful "Robinson

Crusoe." He afterwards fell in with another almost equally

interesting book, by the same writer, "Moll Flanders," which an old

apple-woman on London Bridge lent him to read while he sat behind

her stall there; but "Robinson" exercised by far the greatest

influence on his mind, and probably helped, in no slight degree, to

give a direction to his after career.

His child-wanderings continued; Winchester, Norman's Cross,

near Peterborough (where French prisoners were then kept), and many

other places, passed before his eyes. At Norman's Cross, when

he was some seven years of age, he met with a serpent-charmer; the

man was catching vipers among the woods, and the boy accompanied him

in his wanderings, learning from him his art of catching vipers.

When the old man left the neighbourhood, he made the boy a present

of one of those reptiles, which he had tamed, and rendered quite

harmless by removing the fangs.

Three years passed at Norman's Cross, during which the boy

learned Lilly's Latin Grammar. Then the regiment removed

towards the north, halting, for a time, first in one town and then

in another,—in Yorkshire, in Northumberland, and then beyond the

Tweed, at Edinburgh, where the regiment was quartered in the Castle,

standing high upon its crag, overlooking all the other houses in

that interesting city. Here he was initiated into the boy-life

of Edinburgh,—the "bickers" on the North Loch and along the Castle

Hill, between the New Town and the Old, already immortalized by Sir

Walter Scott. He entered a pupil in the High School, and

gathered, before he left, some further acquaintance with Latin and

other tongues. Oddly enough, one of the cronies whom he picked

up when residing in the Castle, or engaged in "bickers" on the face

of the crag, was David Haggart, then a drummer-boy, afterwards the

most notorious of Scotch criminals, and hanged for murdering the

jailer at Dumfries, in a desperate attempt to escape. But

Borrow's sympathies are so entirely with the criminal and Gypsy

class, that he does not hesitate to compare Haggart with

Tamerlane!—the only difference being that "Tamerlane was a heathen,

and acted according to the lights of his country,—he was a robber

while all around were robbers, whereas Haggart"—then, after a

strange eulogium of the "strange deeds" of Haggart, he concludes,

"Thou mightest have been better employed, David! but peace be with

thee, I repeat, and the Almighty's grace and pardon!"

Two years passed in Edinburgh, during which time the young

Borrow acquired, to his father's horror, the unmistakable dialect of

"the High School callant." Then they left; the militia corps

returned to England, and were disbanded. Another year passed

in quiet life; 1815 arrived, and Napoleon's return from Elba again

threw the whole isle into consternation. The militia were

raised anew, and though the French were quelled, disturbances were

threatened in Ireland, and thither the corps with which Borrow's

father, and now his elder brother, were connected, were shipped from

a port in Essex, and landed at Cork, in Ireland, in the autumn of

the year above named. Up the country they went; it became

wilder as they proceeded,—the people along the road-sides, with whom

the soldiers jested in the patois of East Anglia, answered them in a

rough, guttural language, strange and wild. The soldiers stared at

each other, and were silent. It was Irish-Celtic that the

people spoke, and soon, when the regiment got settled in quarters,

young Borrow set to work, and learnt it from one of his

school-fellows, taking lessons in Irish from him in exchange for a

pack of cards.

Borrow's brother having been sent up the country with a small

detachment of men, the younger brother went to visit him in his

quarters,—crossed the bogs, passed many old ruined castles far up on

the heights, on many of which "the curse of Cromwell" fell. He

was overtaken by a snowstorm when crossing a bog, and had nearly

been devoured by a wild smuggler and his dog, when a few words of

Irish uttered by him at once cleared his road. At length he

reached his brother, in a wild out-of-the-way place, "the officer's"

apartments being in a kind of hay-loft, reached by a ladder.

Young Borrow now learnt to ride; and it is delightful to hear him

when he breaks out in praise of horseflesh. One morning, a

horse is led out by a soldier, that the youth might "give him a

breathing:" he thus describes the horse:—

"The cob was led forth; what a

tremendous creature! I had frequently seen him before, and

wondered at him; he was barely fifteen hands, but he had the girth

of a metropolitan dray-horse; his head was small in comparison with

his immense neck, which curved down nobly to his wide back; his

chest was broad and fine, and his shoulders models of symmetry and

strength. He stood well and powerfully upon his legs, which

were somewhat short. In a word, he was a gallant specimen of

the genuine Irish cob, a species at one time not uncommon, but at

the present day nearly extinct."

He mounted, and the horse set off, the youth on its bare

back. In two hours he made the circuit of the Devil's

Mountain, and was returning along the road bathed with perspiration,

but screaming with delight,—the cob laughing in his quiet equine

way, scattering foam and pebbles to the left and right, and trotting

at the rate of sixteen miles an hour. Hear his enthusiasm on

the subject of the First Ride!

"O, that ride! that first ride!

most truly it was an epoch in my existence, and I still look back to

it with feelings of longing and regret. People may talk of

first love,—it is a very agreeable event, I dare say,—but give me

the flush, and triumph, and glorious sweat of a first ride, like

mine on the mighty cob! My whole frame was shaken, it is true;

and during one long week I could hardly move foot or hand, but what

of that? by that one trial I had become free, as I may say, of the

whole equine species. No more fatigue, no more stiffness of

joints, after that first ride round the Devil's Hill on the cob."

His passion for horses seems almost equal, indeed, to his

passion for boxing, for Bibles, for languages, and for Gypsy life.

His sense of physical life is intense; and wherever muscular energy

has full play, he seems to be in his native element.

Afterwards, when in the middle of one of his sermons at Cordova (see

his "Gypsies of Spain"), it occurs to him that the breed of horses

at that ancient city is first-rate, and off he goes at full gallop,

like a hunter who hears a horn, into a masterly sketch of the

Andalusian Arab, and how to groom him! But one day, while in

Ireland, an accident occurred which introduced him to his first

lesson in "horse-whispering":—

"By good luck a small village was

at hand, at the entrance of which was a large shed, from which

proceeded a most furious noise of hammering. Leading the cob

by the bridle, I entered boldly. 'Shoe this horse, and do it

quickly, a-gough,' said I to a wild, grimy figure of a man, whom I

found alone, fashioning a piece of iron.

" 'Arrigod yuit?' said the fellow, desisting from his work,

and staring at me.

" 'O, yes; I have money,' said I, 'and of the best,' and I

pulled out an English shilling.

" 'Tabhair chugam?' said the smith, stretching out his grimy

hand.

" 'No, I shan't,' said I; 'some people are glad to get their

money when their work is done.'

"The fellow hammered a little longer, and then proceeded to

shoe the cob, after having first surveyed it with attention.

He performed his job rather roughly, and more than once appeared to

give the animal unnecessary pain, frequently making use of loud and

boisterous words. By the time the work was done, the creature

was in a state of high excitement, and plunged and tore. The

smith stood at a short distance, seeming to enjoy the irritation of

the animal, and showing, in a remarkable manner, a huge fang, which

projected from the under jaw of a very wry mouth.

" 'You deserve better handling,' said I, as I went up to the

cob, and fondled it; whereupon it whinnied, and attempted to touch

my face with its nose.

" 'Are ye not afraid of that beast?' said the smith, showing

his fang; 'arrah! it's vicious that he looks.'

" 'It's at you, then; I don't fear him;' and thereupon I

passed under the horse, between its hind legs.

" 'And is that all you can do, agrah?' said the smith.

" 'No,' said I, 'I can ride him.'

" 'Ye can ride him; and what else, agrah?'

" 'I can leap him over a six-foot wall,' said I.

" 'Over a wall; and what more, agrah?'

" 'Nothing more,' said I; 'what more would you have?'

" 'Can you do this, agrah?' said the smith; and he uttered a

word, which I had never heard before, in a sharp, pungent tone.

The effect upon myself was somewhat extraordinary, a strange thrill

ran through me; but with regard to the cob it was terrible; the

animal forthwith became like one mad, and reared and kicked with the

utmost desperation.

" 'Can you do that, agrah?' said the smith.

" 'What is it?' said I, retreating; 'I never saw the horse so

before.'

" 'Go between his hind legs, agrah,' said the smith,—'his

hinder legs;' and he again showed his fang.

" 'I dare not,' said I; 'he would kill me.'

" 'He would kill ye! and how do ye know that, agrah?'

" 'I feel he would,' said I; 'something tells me so.'

" 'And it tells ye truth, agrah; but it's a fine beast, and

it's a pity to see him in such a state; Io agam airt leigeas;' and

here he muttered another word, in a voice singularly modified, but

sweet and almost plaintive. The effect of it was almost

instantaneous as that of the other, but how different! the animal

lost all its fury, and became at once calm and gentle. The

smith went up to it, coaxed and patted it, making use of various

sounds of equal endearment; then turning to me, and holding out once

more the grimy hand, he said, 'And now ye will be giving me the

Sassanach ten-pence, agrah!' "

But at length the militia were all disbanded, and the Borrows

returned to England, where they settled down at Norwich. The

two boys were now growing up, and the elder was put to study

painting; the second, George, was still at his books and rambles.

His thoughts were in the fields, but he learnt French, Italian, and

German. His spare hours were spent in fishing or shooting, and

sometimes in the practice of the "noble art of self-defence."

One day, when attending the horse-fair at Norwich, attracted thither

by the sight of the fine animals which he so admired, he fell in

with the son of the Gypsy man he had before met in the lane at

Norman's Cross, and shortly after he followed him to his tent beyond

the moor. The father and mother, described in our previous

extract, had by this time been "bitchadey pawdel," that is,

"banished beyond seas for crime," and their son, Jasper Pentulengro,

now the Pharaoh of the Gypsies, had to shift for himself. From

this time Borrow's intercourse with the wandering Gypsies was

frequent; he accompanied them to fairs, learnt their language,

acquired the art of horse-shoeing, familiarized himself with their

ways of living,—much to the horror of his parents, who were

disgusted with his loose and wandering habits.

But the boy was now fast growing up into the man, and

something must be done to break him in to the ways of civilized

life; his father accordingly cast about for him, and at length

succeeded in getting the young man articled to a lawyer in Norwich.

But he hated the drudgery of the desk, and made no progress in the

study of the law. Blackstone was neglected for Danish ballads

and Welsh poems. He made the grossest blunders in his

business, and his master wished to get rid of him; but time sped on,

and he remained, alternating his studies of Ab Gwilym by readings of

the life of Moore Carew, "the King of the Beggars," and Murray and

Latroon's histories of Illustrious Robbers and Highwaymen.

Then a celebrated fight would come off in the neighbourhood, and be

sure our youth was present there. Extraordinary it is, how

Borrow, the missionary, should be the one man living to eulogize

this pastime in his books! but he does it, both in his "Gypsies in

Spain" and in "Lavengro." In both he tells us how Thurtell,

the murderer, taught him the use of "the gloves;" and there is one

famous fight, which he has described in glowing language in both

these books, which was got up by Thurtell and Gypsy Will, the latter

his instructor in horse-riding.

"I have known the time," he says,

"when a pugilistic encounter between two noted

champions was almost considered in the light of a national affair;

when tens of thousands of individuals, high and low, meditated and

brooded upon it, the first thing in the morning and the last at

night, until the great event was decided. But the time is

past, and many people will say, Thank God that it is; all I have to

say is, that the French still live on the other side of the water,

and are still casting their eyes hitherward; and that, in the days

of pugilism, it was no vain boast to say, that one Englishman was a

match for two of t'other race; at present it would be a vain boast

to say so, for these are not the days of pugilism."

And again he says: "What a bold and vigorous aspect pugilism

wore at that time! and the great battle was just then coming off;

the day had been decided upon, and the spot, a convenient distance

from the old town;—and to the old town were now flocking the

bruisers of England, men of tremendous renown. Let no one

sneer at the bruisers of England; what were the gladiators of Rome,

or the bullfighters of Spain in its palmiest days, compared to

England's bruisers? Pity that corruption should have crept in

amongst them,—but of that I wish not to speak; let us still hope

that a spark of the old religion, of which they were the priests,

still lingers in the hearts of Englishmen." No, Mr. Borrow,

the glories of pugilism, like those of duelling, bull-baiting, and

bull-running, have all departed, and yet England stands where it

did; nay, we are even strongly of opinion that the English race,

instead of retrograding thereby, has achieved an unquestionable

moral advancement. But we willingly pass over this part of Mr.

Borrow's confessions, which, though racily written, have a very

unhealthful tendency.

At length Borrow's father dies; his articles have expired,

and he is thrown upon the world on his own resources. He went

to London, like most young men full of themselves and yet wanting

help. He packed up his translations of the Danish ballads, and

of Ab Gwilym's Welsh poetry, and sought for a publisher on his

arrival in London. Of course he failed, but he got an

introduction to Sir Richard Phillips, and through his

instrumentality Borrow obtained some task-work from a publisher,

though the remuneration derived from it was so trifling he could

scarcely subsist. He compiled lives of highwaymen and

criminals, and at length, when reduced to his last shilling, wrote a

story, which enabled him to raise sufficient cash to quit the

metropolis, which he did on the instant, and started on a pedestrian

excursion through the country. His life in London occupies the

second volume of "Lavengro;" it seems spun out, and reads

heavy,—very inferior in interest to the first volume, which contains

the cream of the book. In the country he falls in with a

disconsolate tinker, who has been driven off his beat by the

"Flaming Tinman," a gigantic and brutal ruffian. "Lavengro"

buys the tinker's horse, cart, and equipment, and enters upon a life

of savage freedom, many parts of which are most graphically

depicted. At length he falls in with the "Flaming Tinman," and

a desperate fight takes place between them; he vanquishes the

tinman, and gains also one of the tinman's two wives, who remains

with him in the Mumper's Dingle, where they encamp; and here

"Lavengro" ends.

He does not tell us whether his encounter with the "Flaming

Tinman," or his knowledge of Gypsy and hedge-life, had anything to

do with his after career; or how it was that he became a Bible

Society's agent; probably he may tell us something more of that by

and by.

In the meantime we may add what we know of his public history

in connection with the Bible Society, who, in engaging him, possibly

had an eye more to the end than the means. Specimens of his "Kaempe

Viser," from the Danish, were printed at his native place, Norwich,

in 1825; and, shortly after, he was selected by the Bible Society to

introduce the Scriptures into Russia. He resided there for

several years, during which time he mastered its language, the

Sclavonian, and its Gypsy dialects. He then prepared an

edition of the entire Testament in the Tartar Mantchou, which was

published at St. Petersburg, in 1835, in eight volumes. It was

at St. Petersburg that he published versions into English from

thirty languages. In the meantime he had been in France, where

he was a spectator, if not an actor, in the Revolution of the

Barricades. Then he went to Norway, crossed into Russia again,

sojourned among the Tartars, among the Turks, the Bohemians, passed

into Spain, from thence into Barbary,—in short, the sole of his foot

has never rested; his course has been more erratic than that of any

Gypsy, far more eccentric than that of his brother missionary, Dr.

Wolff, the wandering Jew. In his "Bible in Spain" occurs the

following passage, which flashes a light upon his remarkably varied

history:—

"I had returned from a walk in the

country, on a glorious sunshiny morning of the Andalusian winter,

and was directing my steps towards my lodging. As I was

passing by the portal of a large gloomy house near the gate of Xeres,

two individuals, dressed in zamarras, emerged from the archway, and

were about to cross my path, when one, looking in my face, suddenly

started back, exclaiming in the purest and most melodious French,

'What do I see? if my eyes do not deceive me, it is himself.

Yes, the very same, as I saw him first at Bayonne; then, long

subsequently, beneath the brick wall at Novogorod; then beside the

Bosphorus; and last, at—at—O my respectable and cherished friend,

where was it that I had last the felicity of seeing your

well-remembered and most remarkable physiognomy?'

"Myself. —'It was in the south of Ireland, if I

mistake not; was it not there that I introduced you to the sorcerer

who tamed the savage horses by a single whisper into their ear?

But tell me, what brings you to Spain and Andalusia,—the last place

where I should have expected to find you?'

"Baron Taylor. And wherefore, my most

respectable B――? Is not Spain the land of the arts; and is not

Andalusia of all Spain that portion which has produced the noblest

monuments of artistic excellence and inspiration? But first

allow me to introduce you to your compatriot, my dear Monsieur W――,'

turning to his companion, (an English gentleman, from whom, and from

his family, I subsequently experienced unbounded kindness and

hospitality on various occasions and at different periods, at

Seville,) I allow me to introduce to you my most cherished and

respectable friend; one who is better acquainted with Gypsy ways

than the Chef de Bohémiens à Triana; one who is an expert

whisperer and horse-sorcerer; and who, to his honour I say it, can

wield hammer and tongs, and handle a horse-shoe with the best of the

smiths amongst the Alpujarras of Granada.'"

From his great knowledge of languages, physical energies, and

extraordinary intrepidity, it will be clear enough that Mr. Borrow

was not ill adapted for the dangerous mission on which he was

engaged; indeed, he seems to have been pointed out as the very man

for the work. It is not child's play to go into foreign

countries, such as Russia and Spain, and distribute Bibles.

Fortunately for his success in Spain, the country was in a state of

great disorder and turbulence at the time of his mission there, so

that his movements were not so much watched as they would otherwise

have been; yet, as it was, he became familiar with the interiors of

half the jails in the Peninsula. There he cultivated his

acquaintance with the Gypsies and other vagabond races, and gathered

new words for his Romany vocabulary.

While in Spain, however, he did more than cultivate Romany

and distribute Bibles; he brought out Bishop Scio's version of the

New Testament in Spanish; he translated St. Luke into the Gypsy

language, and edited the same in Basque,—one of the languages most

difficult of attainment, because it has no literature; it has other

difficulties, for it is hard to learn,—and the Basque people tell a

story of the Devil (who does not lack abilities) having been

detained among them seven years trying to learn the language, which

he at last gave up in despair, having only been able to learn three

words. Humboldt also tried to learn it, with no better success

than his predecessor. But no difficulty was too great for

Borrow to overcome; he acquired the Basque, thus vindicating his

claim to the title of "Lavengro," or word-master.

If any of our readers should happen not yet to have read "The

Bible in Spain," we advise them to read it forthwith. Though

irregular, without plan or order, it is a thoroughly racy, graphic,

and vigorous book, full of interest, honest, and straightforward,

and without any cant or affectation in it; indeed, the man's

prominent quality is honesty, otherwise we should never have seen

anything of that strong love of pugilism, horsemanship, Gypsy life,

and physical daring of all kinds, of which his books are full.

He is a Bible Harry Lorrequer,—a missionary Bampfylde Moore

Carew,—an Exeter Hall bruiser,—a polyglot wandering Gypsy.

Fancy these incongruities,—and yet George Borrow is the man who

embodies them in his one extraordinary person!

――――♦――――

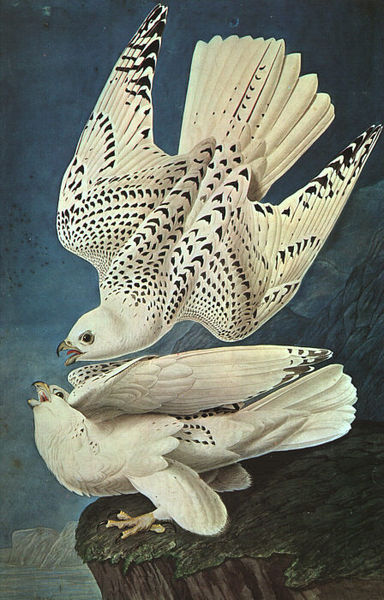

AUDUBON THE ORNITHOLOGIST.

John James Audubon (1785-1851), ornithologist,

naturalist, hunter,

and painter. Picture Wikipedia.

THE great

naturalist of America, John James Audubon, left behind him, in his

"Birds of America" and "Ornithological Biography," a magnificent

monument of his labours, which through life were devoted to the

illustration of the natural history of his native country. His

grand work on the Biography of Birds is quite unequalled for the

close observation of the habits of birds and animals which it

displays, its glowing pictures of American scenery, and the

enthusiastic love of nature which breathes throughout its pages.

The sunshine and the open air, the dense shade of the forest, and

the boundless undulations of the prairies, the roar of the sea

beating against the rock-ribbed shore, the solitary wilderness of

the Upper Arkansas, the savannas of the South, the beautiful Ohio,

the vast Mississippi, and the green steeps of the Alleghanies,—all

were as familiar to Audubon as his own home. The love of

birds, of flowers, of animals,—the desire to study their habits in

their native retreats,—haunted him like a passion from his earliest

years, and he devoted almost his entire life to the pursuit.

He was born to competence, of French parents settled in

America, in the State of Pennsylvania,—a beautiful green undulating

country, watered by fine rivers, and full of lovely scenery.

"When I had hardly yet learned to walk," says he, in his

autobiography prefixed to his work,

"the productions of nature that lay spread all around

were constantly pointed out to me. They soon became my

playmates; and before my ideas were sufficiently formed to enable me

to estimate the difference between the azure tints of the sky and

the emerald hue of the bright foliage, I felt that an intimacy with

them, not consisting of friendship merely, but bordering on frenzy,

must accompany my steps through life; and now, more than ever, am I

persuaded of the power of those early impressions. They laid such

hold of me, that, when removed from the woods, the prairies, and the

brooks, or shut up from the view of the wide Atlantic, I experienced

none of those pleasures most congenial to my mind. None but aerial

companions suited my fancy. No roof seemed so secure to me as that

formed of the dense foliage under which the feathered tribes were

seen to resort, or the caves and fissures of the massy rocks to

which the dark-winged cormorant and the curlew retired to rest, or

to protect themselves from the fury of the tempest."

Audubon seems to have inherited this intense love of nature

from his father, who eagerly encouraged the boy's tastes, procured

birds and flowers for him, pointed out their elegant movements, told

him of their haunts and habits, their migrations, changes of livery,

and so on,—feeding the boy's mind with vivid pleasure and

stimulating his quick sense of enjoyment. As he grew up

towards manhood, these tastes grew stronger within him, and he

longed to go forth amid the forests and prairies of America to

survey the native wild birds in their magnificent haunts. But,

meanwhile, he learned to draw; he painted birds and flowers, and

acquired a facility of delineation of their forms, attitudes, and

plumage. Of course he only reached this through many failures

and defeats; but he was laborious and full of love for his pursuit,

and in such a case ultimate success is certain.

John James Audubon:

Mourning Dove , Zenaida macroura,

hand-coloured engraving/aquatint.

Picture Wikipedia.

His education was greatly advanced by a residence in France,

whither he was sent to receive his school education, returning to

America at the age of seventeen. In Paris, he had the

advantage of studying under the great David. He revisited the

woods of the New World with fresh ardour and increased enthusiasm.

His father gave him a fine estate on the banks of the Schuylkill;

and amidst its beautiful woodlands, its extensive fields, its hills

crowned with evergreens, he pursued his delightful studies.

Another object about the same time excited his passion, and he soon

rejoiced in the name of husband. But though Audubon loved his

wife most fondly, his first ardent love had been given to nature.

It was his genius and destiny, which he could not resist, and he was

drawn on towards it in spite of himself.

He engaged, however, in various branches of commerce, none of