|

INTRODUCTION.

THE spirit which

has awakened, pervades, and moves the multitude, is that of

intellectual inquiry. The light of thought is illuming the

minds of the masses; kindled by the cheap publications, the

discussions, missionaries, and meetings of the last ten years: a

light which no power can extinguish, nor control its vivifying

influence. For the spark once struck is inextinguishable, and

will go on extending and radiating with increasing power; thought

will generate thought; and each illumined mind will become a centre

for the enlightenment of thousands, till the effulgent blaze

penetrates every cranny of corruption, and scare selfishness and

injustice from their seats of power. Chartism is an

emanation of this spirit: its aim is the regeneration of all, the

subjugation of none; its objects, as righteous as those of its

opponents are wicked and unjust, are to place our institutions on

the basis of justice, to secure labour its reward and merit its

fruits, and to purify the heart and rectify the conduct of all, by

knowledge, morality, and love of freedom. Discord and folly

have to some extent unhappily prevailed, for want of sufficient

investigation, but still Chartism has already been led by knowledge

beyond the crushing influence of irresponsible and vindictive

persecutors; and though prejudice and faction may contend with it

for a season, it is yet destined to become a great and efficient

instrument of moral and intellectual improvement.

It will be well, therefore, for all those who seek the

happiness and prosperity of their country—who seek to enjoy the

fruits of honest industry, to extend their hands and exercise their

hearts in acts of benevolence and humanity—to make wiser

preparations to meet this growing spirit than are advised in the

arming proclamations, and found in the acts of whiggery. Our

rulers may exasperate by coercion, but they will find it powerless

in conquering the minds and subduing the hearts of the millions; of

men who, tracing their burthens to exclusive legislation, are

determined to obtain their just share of political right at any

sacrcifice. Those who madly rule the destinies of England

may adopt the same policy their equally inane predecessors pursued

towards unhappy Ireland; and like them may succeed in widening the

gulph between rich and poor, and severing those feelings of justice

and humanity which ought to unite man with his brother man.

They may extend their blue-coated gend'armiere from town to

village; they may fortify with soldiery every workshop, and convert

the peaceful hills and dales of England into one great arsenal, to

keep the haughty and extravagant few in possession of unjust power

and domination: but in the maddened attempt they will throw back the

rolling tide of intellectual and civilizing refinement; they will

generate a military, suspicious, cunning, and vindictive spirit in

the people, which, with taxation, oppression, want, and misery, will

afford abundant materials for the storm of a frenzied and desolating

revolution.

But will the spirit of Christianity, philosophy, and justice

permit of these results? Will those whose active charity has

caused them to explore, midst dangers and death, the remotest tent

and wildest glen to instruct the mind and humanize the savage heart,

forbear to exercise their benevolence in favour of their care-worn

brethren at home? Shall Christian eloquence be employed

against every species of slavery, but such as is found in the

fields, the factories, and workshops of Britain? Will those

who esteem all mankind as "brethren, and all the nations of the

earth as one great family"—whose golden rules of Christian duty are

based on principles of brotherly love, equality, and justice, permit

these glorious principles to be outraged by men of wealth and power,

merely because they profess to tolerate the teaching of principles

they once persecuted and still scorn to practise? Will the

followers of him who ever denounced extortion and injustice, and

proclaimed that the poor and oppressed were the especial objects of

his mission, remain silent spectators of oppression and injustice?

Will the teachers and preachers of his inspired precepts be so far

forgetful of their duty, as to side with the exclusive and

oppressive few, whose ambitious projects and mercenary designs have

converted earth's fruitful blessings and man's happiness into the

curses of war, destruction, and misery?—with men who, not satisfied

with the black record of the last hundred and fifty years of

blood and human wretchedness, the curse of which still crushes

us to earth, [1.] are still pursuing the

steps of their fathers, in warring against the rights and liberties

of humanity?

Can Christians read of those scenes of blood and

carnage which exclusive legislation has engendered without horror?

Can their imagination depict the fraudulent means by which fathers,

husbands, and brothers have been torn from their families and homes,

to bleed and die midst hecatombs of victims, without feeling the

virtuous desire to remove the unholy and brutalizing cause?

But these, say the advocates of exclusiveness, are the acts of days

past, of scenes conscientiously-lamented, and never to be renewed by

any government. Friends of peace and humanity, trust not these

deceitful boasters; hug not the specious deception to your hearts,

but rather let the violated rights, the burning cottages, the slain,

unburied, brute-devoured victims in Canada be their answers.

Nay, refer them to ominous truths nearer home, and let the

formidable answers to our supplications for "justice," in the

shape of rifle-brigades, mortars, rockets, and bludgeon men,

convince you of the improved feelings of exclusive and class

legislation.

The black catalogue of recorded crimes which all history

develops, joined to the glaring and oppressive acts of every day's

experience, must convince every reflective mind that

irresponsible power, vested in one man or in a class of men, is

the fruitful source of every crime. For men so circumstanced,

having no curb to the desires which power and dominion occasion,

pursue an intoxicating and expensive career, regardless of the

toiling beings who, under forms of law, are robbed to support their

insatiable extravagance. The objects of their cruelty may lift

up their voices in vain against their oppressors, for their moral

faculties having lost the wholesome check of public opinion, they

become callous to the supplications of their victims.

Irresponsible, except to their own order, and equally

extravagant and regardless, are those who now hold the political

power of England. The working classes, therefore, having long

felt the evils resulting from this irresponsible authority, in the

partial laws they have enacted and unjustly executed, in the

partial and over-burthening taxation they have imposed upon them,

and in the insolence of those who live on the plunder they have

exacted, seek to establish a wholesome and

RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT, such as shall develop the energies

and promote the happiness of all classes in the state.

And it remains to be seen whether the generous and

philanthropic minds with which our country abounds will second these

exertions. Whether those who are really intent on reforming

vice will perceive the necessity for beginning at the root of the

evil, having so often felt the difficulty of improving the plant

by merely trimming its branches. And still more difficult will

assuredly be their efforts, morally and socially, to improve the

people of this country, while the present anomalous system of

representation is permitted, with all its demoralizing influences.

While we see vicious examples of bribery, fraud, perjury, and

intemperance held forth, in all their admitted baseness and public

notoriety, as means by which the post of "honour" and seat of

"justice" may be obtained; thus sapping the very vitals of morality,

by diverting the aspiring minds of our country from the just and

honest pursuit of public estimation and public reward. While

by far the greater number of our legislators begin their political

career by the adoption of such unworthy means, can we be surprised

at the corrupt, unfeeling, and often immoral conduct, so many of

them display, or wonder at the varied and multitudinous crudities

they dignify with the name of laws?

And when the effects of all these corrupting and pernicious

influences are seen and felt throughout the length and breadth of

the land, engendering poverty, vice, and crime, are we not justified

in directing the public mind to the attainment of political

reformation, as the most certain and direct means of all

moral as of all social reformation.

Can it any longer be doubted that ignorance and poverty,

springing from careless, extravagant, and vicious rulers, originate

the numerous and increasing demands for our gaols, bridewells,

penitentiaries, treadmills, and other useless means of punishment,

together with our workhouses, asylums, and infirmaries—institutions

which the want of proper education and encouragement to industry and

frugality occasion?

A considerable number of individuals may be found, who see

and lament the evils referred to, and trace them to the source

described, but are deterred from exerting themselves to effect the

change we aim at, by the drunken and profligate examples they daily

witness. While they are anxious to effect a radical reform in

our institutions, and turn to contemplate the proposal of political

equality—of trusting men of such demoralizing habits with the

suffrage, they are too often led to conclude that the change would

be the greater evil. But we would anxiously advise persons who

have arrived at such conclusions, to review their facts and

re-exercise their judgments; and, according to their sincerity, we

think they will see just cause for changing their opinions.

Have they satisfied themselves, in the first place, that the

majority of drunken and vicious characters are not already in

possession of the franchise? Else, what other reason can they

assign for the extent of bribery and intemperance so prevalent at

our elections; when the vicious propensities of those who have

votes to dispose of are basely gratified, by men equally base

and destitute of principle to administer to such servile and brutal

appetites? But, granting that the soul-degrading vice of

drunkenness is still too prevalent among the most ignorant of the

working classes, what is the political injury that could

possibly arise from giving them votes under the provisions of the

Charter? Were the franchise, indeed, to be extended, and

the present electoral arrangements preserved, the septennial act

retained, and all the inducements for bribery afforded as at

present; there might, indeed, be some chance of the circle of

drunken voters being inconveniently enlarged, to the trouble and

expense of those who purchase a seven years influence in

parliament to indemnify them for the outlay.

Nay, further, have those objectors to the rights of the

industrious classes, on the plea of intemperance, examined the facts

and evidence that from time to time have been published regarding

the source of the evil, and still fail to perceive its origin

in the misgovernment of the people?

When they learn that the mental and physical debility arising

from protracted and excessive toil, begets a craving appetite for

stimulants to assist them beyond (or to restore) their natural

powers, and find that wholesome and nutritious ones are not always

within the reach or means of the poor; they must assuredly perceive

that our social and political arrangements must be highly defective,

to occasion such degrading results.

When they perceive the mass of the population toiling from

youth to age like beasts of burthen, with little means or time for

intellectual or moral improvement, debarred by cruel and vexatious

laws from cheerful exercise or joyous recreations, and encouraged in

the pernicious habit of drunkenness by the facilities which

government holds out, in order to exact its revenue of

FIFTEEN MILLIONS from the sale of intoxicating

and poisonous ingredients, can they any longer doubt the

originating cause, or fail to perceive that the best remedy will

be a just government?

When, under all these social and political disadvantages,

they find the spirit of temperance and sobriety pervading the ranks

of labour, daily diminishing the amount of drunkenness and

dissipation—when they perceive an enlightened and inquiring mind

generating other habits and feelings among them—when they see them

struggling for political rights as means of improving their class

and dignifying their country, can these objectors any longer refuse

to aid them in their great and noble undertaking?

Are the patient, forbearing, hard-working population of

Britain less qualified for freedom than are the working classes of

Switzerland and America—countries where peace, industry, and

property, bear conclusive evidence in favour of Universal

Suffrage?

In the democratic cantons of Switzerland, agriculture and

manufactures, being combined, produce prosperity in every cottage.

Knowledge and Freedom, twin-sisters, have caused them to outspeed

their neighbours in all the ingenuity and refinements of art.

Their laws, based on equality, are few, just, and respected;

customs, excise, and prohibitory laws, are banished from among them;

justice, cheaply and impartially administered, is every man's

protecting guardian; morality, intelligence, and comfort gladden

every home; and when the most distant infringement on their rights

has been threatened, the spirit of democratic freedom has warmed

each heart and nerved each arm to guard them.

America, the home and refuge for the destitute of all

nations, is as prosperous as she is free. She is daily adding

town to town and village to village, and making neighbours of her

most distant population, by the most stupendous achievements of art.

Her trade and commerce, increasing with her people, give abundance

to industry; and idleness is nowhere respected for its pedigree

among them. She has no debt to embarrass her industry or tame

her spirit. Her taxes are few, and applied to the education

and benefit of her people. For the last fifty years she has

had poverty, prejudice, and vice transplanted from every clime to

blend with her people and impede her progress. And

notwithstanding all are allowed freely to share in her institutions,

upon principles of equality, she has continued to select men for her

presidents and rulers whose characters, conduct, and abilities, in

peace or war, are rarely equalled and never surpassed. The

only stain in her star-bespangled banner is that remnant of kingly

dominion, the slavery of her coloured population; which, like

its damning brother, the infant slavery of England, is more a

feature of wealth and class domination, than of the spirit of her

people or her democratic institutions. But in proportion as

knowledge is extending its humanizing influence over the selfishness

of extending wealth, and the power and prejudices created by its

dominion, so is American slavery fast sinking to that oblivious pit,

where all the impediments which now obstruct the happiness of

black and white are destined to sink for ever.

Nor need the advocates of democratic government, as known in

modern days, confine themselves to the two countries alluded to, for

facts and illustrations in proof of its superiority over governments

based on any other foundation. During the few years the

democratic principle has prevailed in Norway, the rapid improvement

and increased prosperity of her people, have shone forth the more

conspicuously by the dark contrast afforded by her neighbour Sweden,

a country blessed by nature with far greater means of happiness, but

wanting the stimulating soul of freedom to convert them to the

mental and physical uses of her people.

In Spain, a country blessed by God, and for ages cursed by

the despotism of man—a country where plundering nobles and

liberty-hating priests have bowed the people to the dust—even there,

during the brief period of their popular constitution, their

slumbering energies were awakened to generate industry, prosperity,

and happiness, to which they were previously strangers, and which

again vanished, when the liberty was crushed which first awakened

them.

In fact, an example can scarcely be produced in modern

history of any people, whose laws and institutions have been founded

on popular control, without exhibiting distinguishing and

beneficial results, above all others.

The opponents of democracy have not failed to collect the

vices and follies of the ancient republics, and to display

them in all their glaring inconsistencies before us, as so many

proofs of the inefficiency and mischief of popular governments.

But these ingenious sophists fail at the same time to point out a

peculiar feature of modern democracy, which completely nullifies

their argument; that feature is popular representation.

By this great improvement in legislation numerous evils which were

felt in the ancient democracies are avoided; for while every man can

exercise his influence over his representative, to effect his

political desires, the passions and prejudices of the multitude are

kept back from the deliberations of legislation, or the decisions of

justice. Under the representative system, the power of

wealth and influence of oratory may exercise an indirect and

pernicious influence in parliament; but their potent effects cannot,

as in the assemblies of Greece, be brought directly to bear upon the

people, whose decisions were oftener biassed by interest or feeling,

than governed by reason. Moreover, when antiquity is

referred to for examples descriptive of the general or political

acts of the multitude, it should be remembered that our higher

standard of morality, together with the art of printing and

popularizing knowledge, have given advantages in favour of our

population, so as to render such references useless by way of

comparison.

But, viewing democracy under all forms, ancient or modern,

and estimating its merits by the impulse it has given to intellect,

morality, art, science, and all that contribute to the civilization

of man, where are the results of kingly or aristocratical dominion

that can outvie it in the contrast? True it is, that man may

be goaded by coercion, or compelled by necessity, to beautify and

enrich the land of his tyrants; but the most noble and enduring

records of his power, his intellectual and moral greatness,

must spring from energies which freedom alone can awaken.

Those splendid remains and ruins of kingly dominion, those monuments

of human slavery and mindless folly, which now stand in solitary and

crumbling majesty, are destined to fall and be forgotten; but the

moral and intellectual records of Grecian and Roman freedom

still exist in all their sterling and pristine excellence, mingling

with the laws, institutions, literature, and refinements of society,

and will be carried down the stream of posterity, and continue to

exercise their civilizing influence when the hoary pyramids are

crumbled into dust.

But what are the arguments adduced against our principles by

our most decided opponents? or, rather, what are the groundless

assertions their prejudices and fears have originated? The

ancient and honourable institutions of England, say they, are the

cause of her greatness; her power in peace—her success in war—her

holy religion—her trade, commerce, and extensive dominion—all spring

from "the harmonious government of King, Lords, and Commons."

That to uphold the power and dominion she has acquired, under

these fostering influences, force has been necessary abroad and at

home; offices of trust, service and rewards have had to be created,

and "a debt necessarily contracted in providing all these

requisites."

That the liquidation of that debt being as impossible

as it would be imprudent, (seeing its numerous claimants add to the

stability of the government,) "its interest must be

punctually and honourably paid."

That to meet this annual interest of

TWENTY-EIGHT MILLIONS, "taxes have been imposed to a

burthensome though to a necessary extent."

That this great amount of taxation being severely felt

by the middle and working classes, and strong feelings moreover

being entertained by them against the established church, the army,

the corruptions of the navy, and other necessary parts of our

institutions; great danger is to be apprehended from any extension

of the suffrage which "may give the masses a preponderating and

injurious influence in the Commons' House of Parliament."

That Universal Suffrage may give them this influence;

and from their present deficiency of political information, united

with their prejudices against our well-balanced constitution, they

are the more likely to be influenced by violent and designing men,

to destroy it altogether, and consequently involve in that

convulsion "titles, rank, wealth, commerce, and all that constitute

the pride and glory of England."

Such is the general tenor of the arguments (openly or

enigmatically expressed) against the claims of the industrious

classes, by the opposing factions of Whig and Tory.

Whether the "greatness" of England has emanated from the

clashing and opposing interests denominated a "well-balanced

constitution," or from her great natural resources and advantages,

combined with the most enterprizing, skilful, and industrious

population in the world, is a question common sense observers may

easily determine, especially if they take the history of our rulers

in one hand, and that of her people in the other. So far from

agreeing with those constitutional admirers, in all

probability they would decide, that much of what is called

"greatness " is only insignificance and folly; and that

THE TRUE GREATNESS OF ENGLAND HAS ARISEN IN SPITE OF

THE IGNORANCE, OBSTINACY, AND WICKEDNESS OF HER RULERS.―Impartial

observers might further determine, that the selfish ambition which

caused our rulers to war against the rights and liberties of all

nations, and to sacrificed every principle of humanity and justice

in extending our colonial dominion, the more effectually to

obtain power and wealth for themselves and their dependents; is

treason against the God of justice, and arraign them as culprits

before his tribunal, for the blood they have spilt, and the treasure

they have wasted. And therefore the enormous expenditure

consequent on their atrocities, so far from being called "national,"

should be designated "THE BLACK RECORD OF EXCLUSIVE

LEGISLATION." That men in power

should so far practise on the credulity of a people as to incur such

a debt, and for such a purpose, still to go on increasing it beyond

all hopes of payment; still to tax and oppress them for its support,

and transmit the burthen to posterity; and still endeavour to

persuade them of its numerous advantages, will form a wonder without

a parallel in the world's history. But inasmuch as these men,

together with their cunning and trafficing associates, have suceeded

in beguiling the innocent, the friendless, and the

fatherless into the belief that the "funded debt of England"

(this imaginative monster) is of all investments the most profitable

and secure; and consequently have caused them to invest in it the

savings of their industry, the provision for their children, and

support for their old age; humanity and justice, being the great

characteristics of Englishmen, will rise up in any future

legislature to shield and protect such victims of our

debt-contracting and liberty-destroying despots.

When the "justice" can be demonstrated of calling upon

one man to support another man's religion; when tithes, pluralities,

and high church debauchery can find encouragement from scripture;

when standing armies in peace, and navies useless for war, present

better uses than resting places for noble and gentle

fledgelings; when true merit presents its claims, and real

service applies for reward, and when none but the useful and

necessary expenditure of our government is presented to a

British public;—the church, army, and navy, will meet their reward,

and have little to apprehend from popular prejudice or popular

suffrage.—Those strange apprehensions which certain persons feel

from the people's desire to be admitted in their own Parliament

House, and, according to their old "constitutional right,"

manage and economise the national expenditure, would seem to

indicate troubled and guilty consciences. Else why these

dreadful forebodings about the people managing their own affairs?

According to the "Constitution," the Commons' House belongs

to the common people. History inform us, that, at

different periods, they have adopted difference modes of choosing

it, from Universal Suffrage [2] to

that of individual choice; and if they find their present mode an

improper one, they have surely a right to change it for a better,

without the interference of those who belong to the other parts of

the Constitution. If those they once elected as servants have

gradually assume the mastery, and by the power they were first

invested with have rendered the People's House a corrupt and

subservient instrument for party and faction to plunder and oppress

the industrious with impunity, it is indeed time to talk or radical

reform, in order that the people's portion of the Constitution

may be placed in its original position, fairly to "balance" all the

others. But if those sticklers for our Constitution, who are

industriously opposing the efforts now making to reform the

House of Commons, fail to recognize in their reading of that

Constitution the right of Universal Suffrage; it will remain for

them to prove its great and superior excellence to the

satisfaction of the multitude. And great must be their

ingenuity if, in these inquiring times, they can persuade them that

universal labour and universal taxation do not fully entitle them to

Universal Suffrage.

The supposition that Universal Suffrage would give the

working classes a preponderating power in the House of

Commons, is not borne out by the experience of other countries.

They are far from possessing such a power even in America, where

wealth and rank have far less influence than with us, and where the

exercise of the suffrage for more than half a century have given

them opportunities to get their rights better represented than they

are. But wealth with them, as with us, will always

maintain an undue influence, till the people are morally

and politically instructed; then, indeed, will wealth secure

its just and proper influence, and not, as at present, stand

in opposition to the claims of industry, intellect, merit, freedom,

and happiness. But the great advantages of the suffrage in the

interim will be these: it will afford the people general and

superior means of instruction; it will awaken and concentrate

human intellect to remove the evils of social life; and will compel

the representatives of the people to redress grievances, improve

laws, and provide means of happiness in proportion to the

enlightened desires of public opinion. Such indeed are the

results we anticipate from the passing of the PEOPLE'S

CHARTER.

The assumption that the working classes would elect "violent

and designing men" is equally absurd and groundless, as their public

conduct on several occasions testifies. For, setting aside, as

altogether worthless, the idea our opponents entertain, that all who

differ from them in politics are "violent and designing," we

maintain that, taking into account the whole of the political or

municipal contests of the last seven years, the candidates who have

been elected by the multitude by a shew of hands, have been

better qualified for their respective offices, both

intellectually and morally, than those who were

subsequently elected by the privileged class of voters.

It would be invidious were we to mention names, and draw parallels

in proof of this assertion; but if any man of unbiassed mind will

contrast the cases that have come within the range of his experience

during that period, he will agree with its general correctness.

Whether such discrimination in working men betrays the "want of

political information," and proves the superior mental qualification

of electors, can only be partially proved, and that by examining the

meritorious acts of the successful candidates. It would

be well, however, if those who taunt the industrious classes with

their "political ignorance," had first reviewed their political

struggles during the last ten or twelve years. If they had

considered their efforts to establish the rights of free discussion,

to open mechanics' institutions, establish reading rooms and

libraries, form working men's associations, and others of a like

character; and, above all, their sufferings and difficulties in

establishing a cheap press, by which millions of periodicals are

weekly diffusing their enlightening influences throughout the

empire; and then, if those scoffers at the ignorance of the millions

had considered their present efforts to obtain their political

rights, we think they would have reserved their illiberal taunts for

others than the working classes. True it is that individual

exceptions among the middle and upper classes have meritoriously

assisted in all those efforts; but the energies, sufferings, and

pence of the working classes mainly effected those glorious

triumphs. The aristocracy, for the most part, have ever been

active persecutors of all political improvement; and the middle

classes, too intent on buying, selling, and speculating, have

remained apathetic or sneering spectators of the efforts of the many

till success showed the prospect of advantage, and patronage

appeared profitable.

It is further said, that considerable doubts are entertained

of the propriety of trusting the working classes with power, lest

they use it to the prejudice of rank and property, and

the injury of our institutions. But what foundation is

there for such doubts? In what country of the world are the

rights of property more respected? Where are there more laws

to guard it, and where are such laws more easily enforced, than in

England? In fact, the patient submission to arbitrary and

unjust laws for securing property (laws in opposition to their

constitutional rights), constitute the weakness of Englishmen.

When property has been threatened by foreign foe or domestic

spoiler, who have been more forward to defend or active to guard it,

than the calumniated and unprotected sons of labour? Petty

spoilers exist in every country, but the grand enemies and violators

of property in England are to be found among the enemies of the

labourer. Corrupt and blundering politicians, gambling

fundholders, speculating tricksters in trade and commerce, these are

the great violators of the rights of property; men who, by one

specious act or knavish trick, swamp the prosperity of millions, and

convert in a moment the most enlivening-prospects of industry to the

desolation of despair. But even in those convulsions of

ignorance or fraud, who are keener sufferers than the working

classes? or who have had more useful experience to convince them of

the necessity of property being fixed on the firmest foundations,

than those whose homes of comfort have been rendered miserable by

those political or commercial panics? Where, too, are the

claims of merit or the legitimate influence of rank better

appreciated than with us? or where are the efforts of humanity and

benevolence better supported and encouraged than among the labouring

population of England? Then away with those ungenerous

surmises, those fears and anxieties respecting them. Their

interests are blended width the interests of property, and they

have sufficient good sense to perceive it—their hopes of happiness

are based on the prosperity of their country, and all and everything

appertaining to individuals, to classes, to our laws or institutions

which can in any way be promotive of general prosperity, will ever

be held sacred and inviolate by the industrious and generous hearted

people of Great Britain and Ireland.

But, say some of our most captious and prejudiced opponents,

while there is some truth in these observations regarding the

general disposition and feelings of the working classes if they were

left to their own unbiassed judgments, an exception must be made to

that mischievous and discontented party who, under the names of

"Reformers," "Radicals," and "Chartists," are actively engaged in

spreading dangerous opinions among the people, and exciting them to

acts of violence, incendiarism, and revolution. Now, as we

belong to this very "discontented party," and plead guilty to the

title of "Chartist," and are as active too as our humble abilities

permit in propagating what the enemies of truth call "dangerous

opinion;" yet we beg to disclaim on behalf of Chartists generally

the charge of "violence and incendiarism." The term

"revolutionary" may be very appropriate in characterising all

effectual reforms.—But what proofs of "violence or incendiarism"

have they to adduce against the great body of the Chartists?

unless, indeed, like Warwickshire juries, they find their verdict on

one case by the facts of another. A few individuals may

certainly be found in different parts of the country, whose feelings

or sympathies have at times got the better of their judgments, and

prompted them to talk violently or behave unjustly; and others from

very different motives may have committed very illegal and wicked

acts; but we hold it to be equally as unjust to condemn the great

body of Chartists for such acts, as it would be to condemn the whole

of the aristocracy or any other class of persons, because bad men

have frequently been found among them. But such conduct would

appear to be a part of the tactics of our opponents, in order to

afford a pretext for prosecution, and to scare the timid and

unreflecting from our ranks. It has been customary, time

immemorial, for the advocates of injustice and gainers by corruption

to impugn the motives and execrate the names of every man who,

sympathising with his brethren, has been induced to step out of

their ranks to make known their grievances and embody their feelings

in the language of truth. And the time has been when such

daring conduct has met with torture and death. The progress of

opinion has, however, limited the power of despotism; and slander,

persecution, and imprisonment are the modern instruments for

stifling grievances, and checking the progress of truth. If,

however, those persons to whom fate has consigned the destinies of

government ever profited by experience, it might be supposed that

they had had already sufficient to convince them of the fallacy of

such persecuting efforts. It is true they may crush victim

after victim, and by reeking swords and revengeful laws strike back

one timid adherent after another, in the vain attempt to keep back

just principles; but the energies and sympathies God has implanted

in the human mind will ever cause such principles to be fostered,

and will ever embolden new advocates to extend their dominion.

But corrupt and selfish rulers seldom reason on future consequences;

they have hitherto been blindly permitted to cut through every

obstacle by force, to add injustice to the misery they create, and

thus transmit new difficulties to their successors. Happy

would it be however for posterity, if all those who are seeking to

promote the happiness of mankind raised their voices against such

monstrous injustice, and, instead of siding with unjust governors,

investigated the claims of the governed. Had this been done

towards the Chartists, or had even those men who professed

the principles of Chartism before they were combined in a definite

and practical form, been true to their professions, and put

themselves, as they ought, in front of the public will they helped

to create, much of the bitterness of feeling and violence of

language which disappointment and distrust occasioned would have

been spared, and, ere now, one of the most important of triumphs

achieved in favour of human liberty.

What, let it be asked, are the claims of the Chartists? what

is their character? and who are the men so designated? Are

their claims unjust? are they unreasonable? are their characters

depraved? are they men dangerous to the welfare and happiness of

society? Let all those uninterested in the corruptions of the

present system ask those questions; let them examine carefully,

investigate impartially; and Chartism will soon have additional

defenders. They will find their claims to be based on just,

scriptural, and constitutional foundations. They will find

their principles ably set forth in the annals of whiggery, and

vindicated by the most eloquent and talented of British statesmen.

And if the most active and reflecting portion of our population, the

most temperate and industrious, and the most earnest in their desire

to see justice substituted for oppression, truth for falsehood, and

knowledge for ignorance, have any claims of character the reverse of

depravity, then such investigators would find that Chartism and the

character of the Chartists have been grossly misrepresented; for of

the majority of such characters are their ranks composed.

Doubtlessly they are not free, any more than other bodies, from

individuals who are prompted by vain, ambitious, or interested

motives; nor are they all equally temperate in language or action;

but of this we are certain, from our intimate knowledge of the

working classes, that the Chartists are the elite of that

class, both intellectually and morally, and are influenced by the

most generous and disinterested desire to promote the happiness of

their fellow-men. Their general character must not be

estimated by individual or isolated cases of violence or folly.

They have often been deceived themselves by the high-sounding

professions of individuals both within and without St.

Stephen's; and when they have seen their most humble supplications

scoffed at and disregarded, a different or a louder tone must not be

set down to their prejudice. In fact, the experience of the

past would seem to indicate that the passions of the multitude are

frequently God's messengers to teach their oppressors justice; for

when they have spurned alike reason and argument, they have often

yielded to passion what they have refused to sober justice.

There is little hope, however, that our modern rulers will improve

upon the old; but if all those truly benevolent minds who are

labouring earnestly to improve the condition of the multitude, would

carry their investigations to the root of our political and social

evils—would separate themselves from corrupt oppressors, and unite

with those of the industrious classes who are in pursuit of the same

object as themselves; they would find the great body of the

Chartists the most efficient instruments that could be desired in

carrying forward all the beneficial reforms contemplated; and the

Chartists, in return, animated by such co-operation, would prove the

most zealous, temperate, and powerful auxiliaries in banishing

intemperance, poverty, and crime, and in raising the intellectual

and moral character of the people beyond the expectations of the

most sanguine philanthropist.

But, fellow-workmen, while we ought to be anxious for the

co-operation of good men among all classes, we should mainly rely on

our own energies to effect our own freedom. For if we fail in

activity, perseverance, and watchful exertions, and supinely trust

our liberties to others, our disappointment will remind us of our

folly, and new burthens and restrictions place our hopes at a still

greater distance. Benevolent and well-intentioned individuals

of all classes have warmly espoused our principles, and have

zealously laboured to extend them; and thousands, we trust, will yet

be found equally ardent and effective. But when we consider

the various influences of rank, wealth, and station, which are

continually operating to deter all those above our own sphere from

becoming the open and daring advocates of our rights; and consider,

moreover, the numerous links of relationship, professions,

business-connection, interest, and friendship, which bind them to

our present system; we should be the more readily convinced of the

necessity of self-reliance, and the more firmly resolved by

the concentration of every mental and moral energy nature has given

US, TO BUILD UP THE SACRED TEMPLE OF OUR OWN

LIBERTIES. The means are within our grasp, if we

judiciously apply them, and no power on earth can prevent the

consummation of so glorious an achievement. Then shall we the

better appreciate what we have intellectually and morally erected;

then shall we stand on its threshold erect, and enter its precincts

rejoicing—possessing rights and feelings which no earthly power can

confer, and inspired with a mental devotedness to use them for our

country's welfare. And when we shall be no more, then may our

children proudly point to that edifice raised by their hard-working

progenitors when they were depressed by poverty, weakened by toil,

and cursed by corrupt and plundering oppressors. Let our hopes

then be built on our own united exertions, and let those exertions

be proportioned to the magnitude of our object, and success will

soon yield us a bountiful reward.

In proportion to our earnestness and perseverance will our

numbers be extended, will our resources and influence increase, and

will men of all ranks find it to be their interests to advocate the

principles they now spurn, and to associate with the men they now

stigmatize and persecute.

Unquestionably a superficial consideration of the exertions

we have made and the disappointments we have experienced, during the

last three or four years, is too apt to dispirit us. For,

while lamenting our poverty and complaining of our burthens, we have

seen one oppressive project after another introduced into

parliament, supported by those we thought our friends, and

eventually carried by large majorities. We have exhausted

reason and argument to show the injustice of such measures, and have

prayed and supplicated in vain against their enactment.

Finding our rights and interests daily sacrificed by such conduct,

we sought a share in the making of the laws we were called upon to

obey. We availed ourselves of the constitutional usages of our

country, we met in millions, and peaceably petitioned for redress.

While our complaints were disregarded, our arguments exasperated and

our numbers excited the terror of our oppressors. Hence, every

delusive scheme was invented to check the progress of our

principles, and every species of force employed to silence the voice

of our advocates. The right of public meeting was invaded by

despotic mandates, and a new system of espionage adopted to control

our boasted freedom of speech and liberty of action. In fact,

every means that our rulers could devise and their minions execute,

have been adopted to keep us in social and political bondage.

But, fellow-countrymen, while the recollection of such

injustice may cast a momentary cloud across our hopes, the voice of

duty should arouse us to redouble our exertions in a cause so noble

as the one we have espoused. If we remain in apathy, be

assured that the misery of the Irish peasant will be our lot or that

of our offspring; for, as certain as the demon of misrule has

withered the energies and drained out the vitals of that unfortunate

country, so will it drive out British capital by its taxation,

monopolies, and oppression; and, by drying up the resources of

labour, break down and extinguish our middle-class population, and

reduce us to such degradation and wretchedness as in all ages have

ever followed the track of unjust government and corrupt spoilers.

But if we stand forward as a band of brothers, linked in the cause

of benevolence and justice, and resolve, at any sacrifice, to avert

a fate so miserable to ourselves and posterity, our numbers,

our resources, and combined operations, will surely

reward us with success.

But, then, it may be asked, what other form of combination,

what other means than those we have already employed, can be adopted

to accomplish our political and social salvation? Must we

again spend our pence and breath in useless prayers for justice?

Must we, whose industry sustains the state, and whose arms defend

it, humbly crave our rights from those who profit by our wrongs and

get rewarded for our servility with blugeons and sabres?

Fellow-countrymen, while these last questions have occupied our most

serious attention, we cannot recommend the repetition of such

useless and hopeless labours. The most important questions

that, we conceive, have engaged our attention during the last twelve

months are these:—How can we best create and extend an enlightened

public opinion in favour of the People's Charter, such as shall

peaceably cause its enactment; and how shall that opinion be

morally and politically trained and concentrated, so as to

realize ALL THE SOCIAL HAPPINESS that can

be made to result from the powers and energies of representative

democracy? While we have no disposition to renew the unwise

and unprofitable discussion regarding "moral" and "physical" force;

and while we maintain that the people have the same right to

employ similar means to regain their liberties, as have been used to

enslave them, we are anxious, as we have ever been, to effect our

object in peace. And though we incurred no small share

of censure from the most ardent of our brethren, for contending for

the superiority of our moral energies over our physical abilities,

we think the disposition we evinced, and the part we performed, both

in and out of the Convention, towards carrying all and every

righteous measure into effect likely to promote the passing of

the Charter, will sufficiently exonerate us from any charge of

cowardice, as well as from any selfish predilection in favour of our

own opinions. And, however we may regret, we are not disposed

to condemn, the confident reliance many of our brethren placed on

their physical resources, nor complain of the strong feelings they

manifested against us, and all who differed in opinion from them.

We are now satisfied that many of them experience more acute

sufferings, and daily witness worse scenes of wretchedness, than

sudden death can possibly inflict, or battle-strife disclose to

them. For, what worse can those experience on earth who, from

earliest morn to latest night, are toiling in misery, yet starving

while they toil—who, possessing all the anxieties of fond parents,

cannot satisfy their children with bread—who, susceptible of every

domestic affection, perceive their hearths desolate, and little ones

neglected, while the wives of their bosoms are exhausting every

toiling faculty in the field or workshop, to add to the scanty

portion which merely serves to protract their lives of care-worn

wretchedness? Men thus steeped in misery, and standing on the

very verge of existence, cannot philosophise on prudence; they are

disposed to risk their lives on any chance which offers the prospect

of immediate relief, as the only means of rendering life

supportable, or helping them to escape death in its most agonizing

forms. When we further reflect on the circumstances which have

hitherto influenced the great mass of mankind, we are not surprised

at the feeling that prevails in favour of physical force. When

we consider their early education—their school-book heroes—their

historical records of military and naval renown—their idolized

warriors of sea and land—their prayers for conquest, and

thanksgivings for victories—and the effect of all these influences

to expand their combative faculties, and weaken their moral powers,

we need not wonder that men generally place so much reliance on

physical force, and undervalue the superior force of their reason

and moral energies. Experience, however, will eventually

dispel this delusion, and will cause reformers to hold in reserve

the exercise of the former, till the latter has been proved to be

ineffectual. Nor can we help entertaining the opinion, that

recent experience has greatly served to lessen the faith of the most

sanguine in their theory of force, and caused them to review

proposals they once spurned as visionary and contemptible.

While we never doubted the constitutional right of Englishmen to

possess "arms," we have doubted the propriety of placing reliance on

such means for effecting our freedom; and further reflection has

convinced us, that far more effective and certain means are within

our reach.

Thus far we have deemed it necessary to explain our views on

this point, and now let us cast the mantle of oblivion over all past

follies and by-gone dissensions; we have one great object in view,

and must be one in soul to achieve it. We have suffered

persecution for that object, but have not been convinced of the

justice of our enemies—we have been crushed with severity, but our

spirits have not been broken—calumny has assailed our cause, but has

failed to lessen our attachment to it—the triumph of our principles

has been delayed, but it will not be the less certain. But,

fellow-countrymen, in order to ensure this speedily, we should

endeavour, in the first place, to satisfy ourselves as to the

most efficient kind of combination, and then direct all our

energies to its accomplishment. And in this pursuit we must

avoid all contentious feelings, and carefully and calmly consider

the different propositions that may be submitted for our

consideration. With this desire, we respectfully submit that

our combination should be such as to induce all those to join us who

are sincerely interested in the social and political improvement of

the millions—such as shall render us the most efficient aid to

effect these objects, while it places us in the best possible

position to enforce our political claims—and such as in our progress

will afford ourselves and children the means of superior education,

so that permanent benefits and substantial fruits may result from

our labours. As some persons, however, may imagine that such

important results are not within the compass of practicability,

while others may suppose that the numerous objects embraced in such

a plan are calculated to place our political emancipation at a

greater distance, we proceed at once to submit the following "Plan,

Rules, and Regulations," for the consideration of our brethren;

hoping we shall hereafter be able to demonstrate its practicability,

and prove it to be the nearest means towards the

accomplishment of our great object—that of securing to all men

THEIR EQUAL POLITICAL AND SOCIAL RIGHTS.

――――♦――――

PROPOSED

PLAN, RULES, AND REGULATIONS

OF AN ASSOCIATION, TO BE ENTITLED,

THE NATIONALS ASSOCIATION

OF THE

UNITED KINGDOM,

For Promoting the Political and Social Improvement

of the People.

――――♦――――

WHILE general or

local associations are not wanting for extending in charity the

dogmas and exclusiveness of sects, or proclaiming the

ostentatiousness of pride—for spreading knowledge and sympathy

abroad, while both are greatly needed at home—for the mitigation of

the physical and mental ills of life, while the originating causes

are neglected—for the acquisition of languages, literature, and

professional skill—for refining the tastes and enriching the

imaginations of mankind—for investigating the properties of all

nature, from the most minute object to the most stupendous—and for

rendering the powers and uses of every element subservient to the

production of wealth; there seems to be wanting an association

paramount in importance to all—ONE FOR POLITICALLY

AND SOCIALLY IMPROVING THE PEOPLE. To supply this great

national deficiency, it is proposed that an association be

established, and that the following be its objects:

First. To unite, in one general body, persons of

all CREEDS, CLASSES, and

OPINIONS, who are desirous to promote the

political and social improvement of the people.

Second. To create and extend an

enlightened public opinion in favour of the principles of the PEOPLE'S

CHARTER, and by every just means secure its

enactment; so that the industrious classes maybe placed in

possession of the franchise, the most important step to all

political and social reformation.

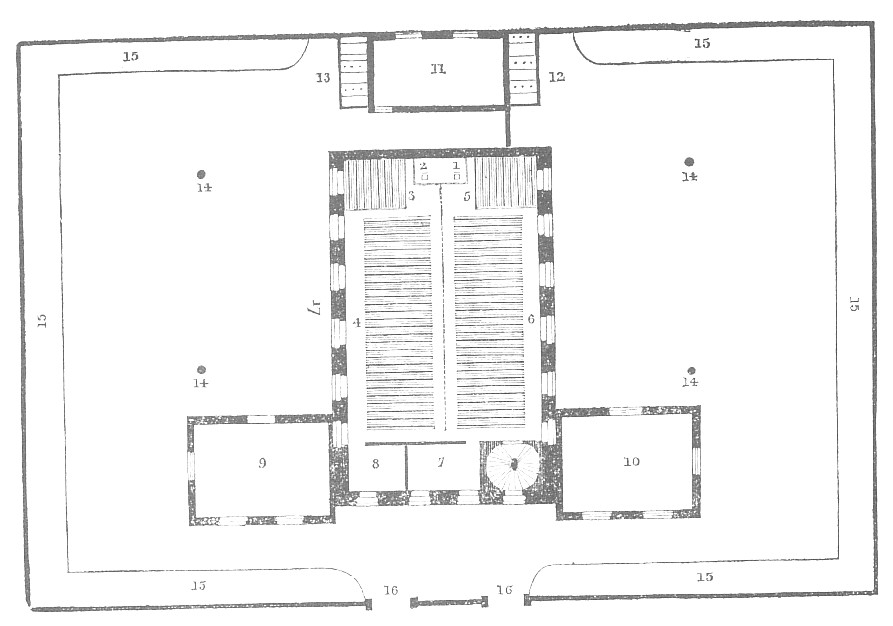

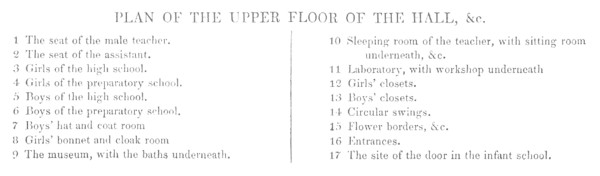

Third. To erect PUBLIC HALLS or

SCHOOLS FOR THE PEOPLE throughout

the kingdom, upon the most approved principles, and in such

districts as may be necessary. Such halls to be used during the day

as INFANT, PREPARATORY, and

HIGH SCHOOLS, in which the children

shall be educated on the most approved plans the association can

devise; embracing physical, mental, moral, and political

instruction;—and used of an evening for PUBLIC LECTURES, on

physical, moral, and political science; for READINGS,

DISCUSSIONS,

MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENTS, DANCING, and such other healthful and

rational recreations as may serve to instruct and cheer the

industrious classes after their hours of toil, and prevent the

formation of vicious and intoxicating habits. Such halls to have two

commodious play-grounds, and, where practicable, a pleasure garden,

attached to each; apartments for the teachers, rooms for hot and

cold baths, for a small museum, a laboratory and general workshop,

where the children may be taught experiments in science, as well as

the first principles of the most useful trades.

Fourth. To establish, in such towns or districts as may be found

necessary, NORMAL or TEACHERS' SCHOOLS, for the purpose of

instructing schoolmasters and mistresses in the most approved

systems of physical, mental, moral, and political training.

Fifth. To establish, on the most approved system, such

AGRICULTURAL

and INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS as may be required, for the education and

support of the orphan children of the association, and for

instructing them in some useful trade or occupation.

Sixth. To establish CIRCULATING LIBRARIES, from a hundred to two

hundred volumes each, containing the most useful works on politics,

morals, the sciences, history, and such instructive and entertaining

works as may be generally approved of. Such libraries to vary as

much as possible from each other, and to be sent in rotation from

one town or village in the district to another; there to be placed

in the hands of a responsible person, to be lent out according to

the rules, and, after a stated time, forwarded to the next district.

Seventh. To print, from time to time, such

TRACTS and PAMPHLETS as

the association may consider necessary for promoting its objects,

and, when its organization is complete, to publish a monthly or

quarterly national periodical.

Eighth. To offer premiums, whenever it may be considered advisable,

for the best essays on the instruction of children; for the best

description of school-books for infants, juveniles, and adults; or

for any other object promotive of the social and political welfare

of the people.

Ninth. To appoint as many MISSIONARIES as may be deemed necessary,

to visit the different districts of the kingdom, for the purposes of

explaining the views of the association, for promoting its efficient

organization, for lecturing on its different objects, for visiting

the different schools when erected, and otherwise seeing that the

intentions of the general body are carried into effect in the

several localities, according to the instructions they may receive

from the general board.

Tenth. To devise, from time to time, the best means by which the

members in their several localities may collect subscriptions and

donations in aid of the above objects, may manage the

superintendence of the halls and schools of their respective

districts, may have due control over all the affairs of the

association, and share in all its advantages, without incurring

personal risk, or violating the laws of the country.

RULES.

――♦――

OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION.

THE affairs of

this association shall be conducted by a general board of

management, a president, vice-president, treasurer, secretary, and

such sub-committees and assistants as may be found necessary.

GENERAL BOARD—HOW CHOSEN.

Every county possessing five hundred members of this

association shall be privileged to elect one member to the

general board of management; and if possessing more than twice that

number, may elect two members, but no more. Their election

shall take place in the month of May in each year, in the following

manner:—A public meeting of all the members of the association

within the county shall be called, by public advertisement, for the

purpose of electing a member or members of the general board, of

which meeting six days' notice shall be given. On the day of

meeting, after the proposers, seconders, and candidates have

explained their views, the voting shall commence, and the votes be

collected as follows: As many balloting boxes as may be found

necessary shall be placed in different parts of the meeting, each

box having as many partitions as there are candidates (or one box

for each, if found more convenient); and on the top and front of

each partition shall be legibly affixed the names of the respective

candidates. Two scrutineers shall be appointed by each

candidate to stand by each balloting place, to see that none but

persons qualified do vote, and that the voting is conducted fairly.

The members of the association shall then vote with their cards

of the last quarter, and them only (and persons unwell or

residing at a distance may send their cards, and empower their

friends to vote for them); which cards they shall drop into the

partitions of their favourite candidates, through a slit on the top

of each partition. [3] After it has

been publicly announced from the hustings that the balloting is

about to be closed, and a further reasonable time allowed for all

members present to vote, the balloting shall cease. The boxes

shall then be sealed, and taken away to the first convenient place,

where, in the presence of the candidates, or their friends, the

scrutineers shall count the votes. After which they shall at

once proceed to the hustings, and publicly announce the names and

numbers of the respective candidates, and declare the persons who

are elected.

OFFICERS—HOW CHOSEN.

The president, vice-president, treasurer, secretary, and such

other officers as may be required, shall be elected by the

general board on the first day of its sittings in each year; the

election shall be by ballot, and decided by a majority of votes.

All members of the association (whether elected to the general board

or not) shall be eligible to fill any office according to their

competency.

MEMBERS—THEIR ELIGIBILITY.

All persons, male and female, approving of the

objects, and conforming to the rules of the association, are

eligible to become members, and share in all its advantages,

on paying in advance the sum of one shilling for a card—the

same to be renewed every quarter.

THE PRESIDENT—HIS DUTIES.

It shall be the duty of the president to attend all meetings

of the general board, and preside over their deliberations. He

shall see that all questions are discussed consecutively, according

to the notices given; that no member speak more than once on the

same question, unless in reply; and that proper order and decorum be

preserved. He shall sign all official orders or documents

passed by the board, as well as all money orders voted by them, or

commissioned by their authority. He shall be empowered to

order an especial meeting of the board to be summoned on any

extraordinary occasion, as well as to order a meeting of the

officers of the association to be called, whenever he may deem it

necessary.

THE VICE-PRESIDENT—HIS DUTIES.

During the time the president is present, the vice-president

shall assist in the business of the board, and when he is absent,

shall preside over their deliberations. He shall also perform

such other duties appertaining to the office of president as he may

require of him under his written authority.

THE TREASURER—HIS DUTIES.

The treasurer shall cause all moneys received by him to pass

through the hands of the bankers, and shall keep a correct account

from their books of all moneys transmitted to them, and the names of

the persons from whom sent. He shall pay all bills of the

association under an order of the general board, and signed by the

president or vice-president, but not otherwise. He shall see

that all checks on the bankers are signed by himself and the

president or vice-president. His accounts of receipts and

expenditure shall be open for the inspection of the general board,

and other officers of the association, whenever they meet; and every

year he shall prepare a general balance-sheet, to be laid before the

board the first day of its sittings.

THE SECRETARY—HIS DUTIES.

The secretary shall attend all meetings of the general board,

as well as all meetings of the officers of the association, and keep

correct minutes of their proceedings; which minutes he shall read

over at the next meeting. He shall conduct all the

correspondence of the association, and confer with its officers

respecting all business of importance. He shall see that new

cards are issued for the members (of a different colour each

quarter), and are forwarded to the members of the general board, as

hereafter provided. All moneys, either subscriptions or

donations, which pass into his hands, he shall hand over to the

treasurer, and keep a correct account of the same, as well as of all

petty cash he may have expended, and make out a balance-sheet of the

same, to be laid before the general board the first day of its

sittings.

MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL BOARD―THEIR DUTIES.

The members of the general board shall meet in London the

first Monday in June in each year, for the transaction of

business; they shall hold their sittings from day to day (Sunday

excepted), but shall not prolong them beyond a fortnight; and in

case an extraordinary meeting be convened by the president, their

sittings shall not exceed that time. Their meetings shall be

open to gentlemen of the press, and such members of the association

as the room will accommodate. The expenses of the members of

the board to and from London must be defrayed by the members of

their respective counties. It shall also be their duty to

receive, from the secretary, the new cards for the members every

quarter; as well as to appoint responsible and proper persons to

issue the same to members (or persons desirous of becoming members)

in different parts of their respective counties. They shall

keep a list of the names and residence of the persons they may so

appoint, as well as a correct account of the cards they entrust to

them for distribution. They shall also see that such persons

do properly fill up the cards, and keep a correct list of the

members who purchase them; so that the numbers not disposed of may

be returned when required. It shall also be their duty to see

that no cards are issued on credit, and that the receipts of those

sold are returned to them before they send out the cards of the next

quarter. At the commencement of every quarter they shall cause

all sums in their possession to be transmitted to the bankers of the

association in the names of the treasurer, president, and

vice-president for the time being; and at the same time send the

particulars to the secretary, who, on ascertaining that the money is

received, shall transmit them a receipt. They shall be paid

the portages of all letters and carriages of all parcels by the

treasurer of the association.

SUB-COMMITTEE―THEIR DUTIES.

The president, vice-president, treasurer, and secretary, for

the time being, together with such members of the general board as

choose to attend, shall be considered a perpetual sub-committee

when the board is not sitting. They shall meet every three

months, or oftener if required, for the purpose of performing such

business as may be necessary, their powers having been previously

defined by the general board.

THE MISSIONARIES―THEIR DUTIES.

The missionaries shall be appointed by the general board, at

a weekly salary, out of which they shall pay all the expenses of

their mission. It shall be their duty to visit such places

and perform such duties as the board may require, according to a

plan of their route and written instructions they shall receive.

It shall be their especial duty to perfect the organization of the

association in each county they may be called upon to visit, to

explain its objects and advantages, to visit the different schools,

see that the books and tracts of the association are properly

circulated, and that its rules are everywhere properly observed.

They shall be supplied by the association with placards for calling

such meetings as may be required, together with tracts for

distribution, and cards and rules, if necessary.

COUNTIES TO BE DIVIDED INTO DISTRICTS.

In order to divide the different counties into districts,

according to such numbers of the association in each as would render

the erection of a hall and establishment of schools useful, it shall

be the duty of the members of the general board to call a general

meeting, on the first of October in each year, of all the

persons they have appointed to issue members' cards in different

parts of their respective counties. The persons so assembled

in each county shall determine the number of districts in their

county, according to the number of paying members, which shall be

denominated hall districts. They shall then make out a proper

list of such districts, which, having been signed by the chairman of

the meeting, and five others, shall be forwarded to the secretary of

the association, for purposes hereafter mentioned.

THE ERECTION OF DISTRICT HALLS.

At the annual meeting of the general board, they shall

determine, according to the funds in the hands of the bankers, how

many district halls shall be erected; and in order that the funds

may be usefully and justly apportioned, the following plan shall be

adopted:—The names of all the counties in which there are

five hundred members of the association shall be written on as many

different slips of paper, which slips shall be carefully folded and

put into a balloting box properly constructed for the purpose.

A person shall then be called into the room, and requested to draw

out as many of the said slips as it has been previously resolved to

erect halls; the names on which slips shall be the counties in which

they shall be erected. The counties having been so determined

on, the names of the districts in each successful

county shall be written on similar slips of paper, and each county

separately balloted for in like manner; the last drawn slip in each

county shall be the district in which the hall shall be erected.

As soon as the balloting is concluded, the secretary shall write to

each of the successful districts, requesting them to call a general

meeting of the members of the association residing in the district,

for the purpose of electing twelve proper persons for

superintending the erection of the hall, and for its management when

erected, as well as seven trustees, in whose names the property

shall be invested in trust for the benefit of the district,

according to rules and regulations which the general board shall

provide for those several purposes. It shall also be the duty

of the association to appoint a qualified person to see that the

hall is erected in accordance with its plans and objects; but if any

additional sum be added by the subscriptions or donations of the

district, such sums may be applied to beautify or enlarge it in any

manner, so long as the original design be complied with.

NORMAL SCHOOLS.

In order to provide such schools as the association may

establish with efficient teachers, it shall be the duty of the

general board to establish, as soon as possible, such normal schools

(with model schools attached to them) as may be required. They

shall found them in such places, and on such rules and regulations,

as in their judgment will best promote the objects of the

association. They shall also see that such normal schools are

provided with proper school-teachers or directors, and supplied with

the best works on physical, mental, moral, and political training;

as well as such school apparatus as will best serve to perfect the

teachers in the art of properly training the rising generation.

The rules referred to shall declare the qualifications for admitting

persons to be instructed as teachers, and after they have studied

the time required by the rules, and have been declared fully

competent by the directors, they shall be provided with

credentials of the association attesting the same; and after a

sufficient number of such teachers are properly qualified, none

shall be employed in the schools of the association but those

provided with such certificates.

AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS.

It shall be the duty of the general board to establish (as

soon as their funds will enable them) such agricultural and

industrial schools as may be found necessary for the educating,

supporting, and instructing in some useful trade or occupation

the orphan children of the association. They shall be

established on the most approved plans, and in such situations as

the board may consider desirable, and shall be provided with such

efficient means of instruction and support as shall hereafter be set

forth in the rules and regulations of the association.

SUPERINTENDENTS TO BE ANNUALLY ELECTED.

After the first election of the superintendents of the halls

and schools as before provided for, an annual election of them shall

take place in the month of July in each year, in the following

manner:— The old superintendents (or any twenty members, if they

refuse), shall cause a notice to be stuck on the front of the hall

door a fortnight previous to the election, announcing the time when

and place where the meeting of the members of the district shall

take place for the purpose of electing twelve superintendents for

the next year, and stating the time when all nominations must be

given in. Lists of the persons so nominated shall then be

printed, and one be sent to each of the members, who shall mark off

on the list the twelve persons he or she approves of; and on

the day of the meeting shall drop such list in a box made for that

purpose. Four scrutineers shall then be appointed to examine

such lists, and declare who are the persons elected. The

superintendents of the last year shall be eligible to be re-elected.

RESIGNATIONS OR DEATHS.

On the resignation or death of any member of the general

board, his place shall be filled up in the same manner as is pursued

at a general election; excepting that the members shall be supplied

with voting tickets instead of their quarterly cards. On the

resignation or death of any general officer of the association, his

place shall be filled up or supplied by the sub-committee, till the

next meeting of the general board. And on the resignation or

death of any district superintendent, the duties shall be performed

by his colleagues till the next annual election.

ALTERATION OF RULES.

Any member of the general board desirous of proposing any

alteration or amendment in the rules and regulations of the

association, shall give two days' notice of the same, and the

alteration be determined on by a majority of votes.

――――♦――――

RULES FOR THE CIRCULATING

LIBRARIES.

The general board shall determine, from time to time, the

number of circulating libraries, and the description of books, that

shall be provided in conformity with the objects of the association.

The case for each library shall be fitted up with moveable

partitions, and so constructed as to form a strong box when shut,

and (by hinging it in the centre of the back) a book-case when open.

The books in each case shall be properly numbered, and a

catalogue and rules enclosed in each case, which shall be fastened

with a lock and key.

The district teachers shall be the librarians, and in the

event of there being none in a district, the members of the

association therein shall select responsible persons to act as

librarians, and shall send the names of such persons to the

secretary of the association.

The general sub-committee shall cause the libraries to be

sent in rotation to the difference counties; and the

librarians shall send them in rotation to the several districts

in each county.

Each library shall be retained in a district three months,