|

"'TO BE SURE I CAN,' REPLIED THE LARK."

――――♦――――

|

CONTENTS |

| |

PAGE |

|

THE

OUPHE OF THE WOOD |

11. |

|

THE

FAIRY WHO JUDGED HER NEIGHBOURS

|

28. |

|

THE

PRINCE'S DREAM

|

39. |

|

THE

WATER-LILY |

52. |

|

A LOST

WAND |

66. |

|

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS |

|

|

PAGE |

|

"'TO

BE SURE I CAN,' REPLIED

THE LARK" |

Frontispiece |

|

"SO

HE SAT DOWN AS CLOSE TO THE FIRE AS HE COULD,

AND SPREAD OUT HIS

HANDS TO THE FLAMES" |

13. |

|

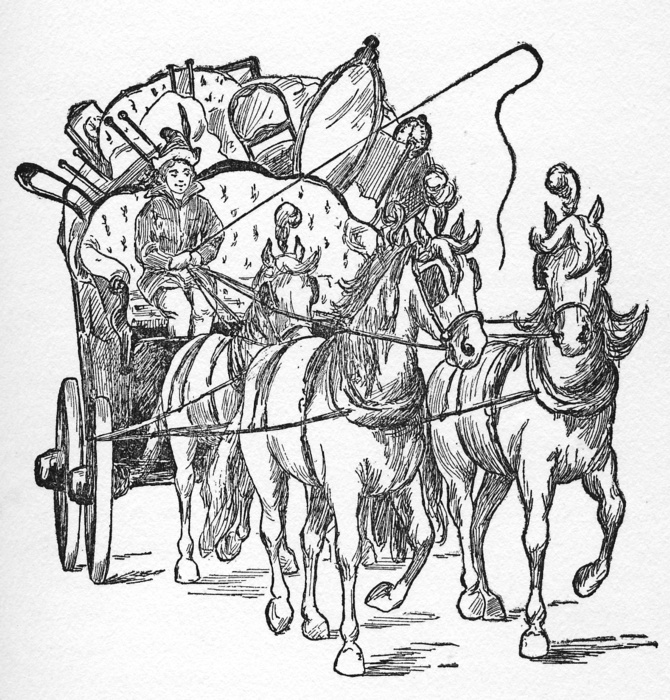

"COMING

HOME ON TOP OF IT, DRIVING THE FOUR GRAY

HORSES HIMSELF"

|

19. |

|

"WHILE

SHE WAS FITTING ON HER SHOES, SHE SAW THE

LARK'S

FRIEND" |

35. |

|

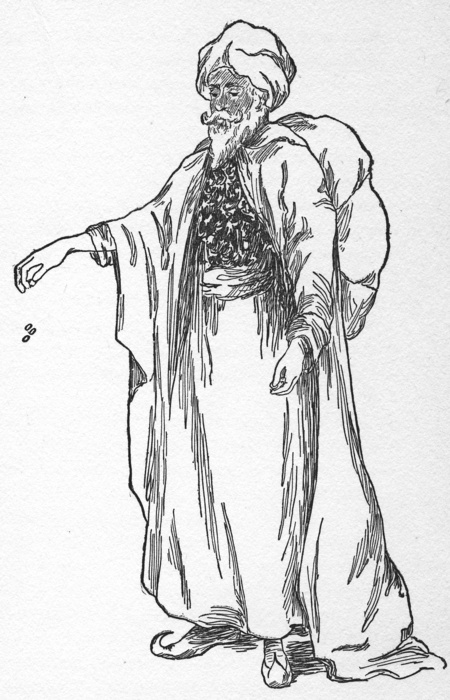

"THEN

HE RECLINED BESIDE THE CHAFING-DISH AND

INHALED THE HEAVY PERFUME" |

45. |

|

"'I

COULD NOT DO SO,' HE, REPLIED, 'ONLY THAT AS I

GO ON

I KEEP LIGHTENING IT'"

|

49. |

|

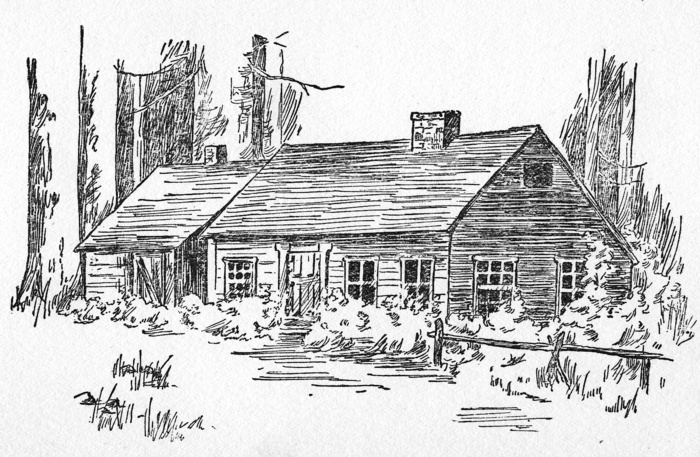

"LIVED

ON THE BORDERS OF ONE OF THE GREAT AMERICAN

FORESTS" |

56. |

|

"THE

NEXT MOMENT A BEAUTIFUL LITTLE CREATURE STOOD

UPON HIS HAND"

|

58. |

|

"'OH,

DON'T GO,' CRIED HULDA.

'I AM GOING UPSTAIRS TO

FETCH MY WAND"'

|

77. |

|

"THE

PEDLAR HAD NOW SUNK UP TO HIS WAIST" |

95. |

――――♦――――

|

WONDER-BOX TALES

THE OUPHE

OF THE WOOD

"AN Ouphe!" perhaps you exclaim, "and pray what might that be?"

[1]

An Ouphe, fair questioner, though you may never have heard of him,

was a creature well known (by hearsay, at least) to your

great-great-grandmother. It was currently reported that every forest

had one within its precincts, who ruled over the woodmen, and

exacted tribute from them in the shape of little blocks of wood

ready hewn for the fire of his underground palace, such blocks as

are bought at shops in these degenerate days, and called in London

"kindling."

It was said that he had a silver axe, with which he marked those

trees that he did not object to have cut down; moreover, he was

supposed to possess great riches, and to appear but seldom above

ground, and when he did to look like an old man in all respects but

one, which was that he always carried some green ash-keys about with

him which he could not conceal, and by which he might be known.

Do I hear you say that you don't believe he ever existed? It matters

not at all to my story whether you do or not. He certainly does not

exist now. The Commissioners of Woods and Forests have much to

answer for, if it was they who put an end to his reign; but I do not

think they did; it is more likely that the spelling-book used in

woodland districts disagreed with his constitution.

After this short preface please to listen while I tell you that once

in a little black-timbered cottage, at the skirts of a wood, a young

woman sat before the fire rocking her baby, and, as she did so,

building a castle in the air: "What a good thing it would be," she

thought to herself, "if we were rich!"

It had been a bright day, but the evening was chilly; and, as she

watched the glowing logs that were blazing on her hearth, she wished

that all the lighted part of them would turn to gold.

She was very much in the habit this little wife of building

castles in the air, particularly when she bad nothing else to do, or

her husband was late in coming home to his supper. Just as she was

thinking how late he was there was a tap at the door, and an old man

walked in, who said:

"Mistress, will you give a poor man a warm at your fire?"

"And welcome," said the young woman, setting him a chair.

So he sat down as close to the fire as he could, and spread out his

hands to the flames.

"So he sat down as close to the fire as he could,

and spread out his hands to the flames."

He had a little knapsack on his back, and the young woman did not

doubt that he was an old soldier.

"Maybe you are used to the hot countries," she said.

"All countries are much the same to me," replied the stranger. "I

see nothing to find fault with in this one. You have fine

hawthorn-trees hereabouts; just now they are as white as snow; and

then you have a noble wood behind you."

"Ah, you may well say that," said the young woman. "It is a noble

wood to us; it gets us bread. My husband works in it."

"And a fine sheet of water there is in it," continued the old man. "As I sat by it to-day it was pretty to see those cranes, with red

legs, stepping from leaf to leaf of the water-lilies so lightly."

As he spoke he looked rather wistfully at a little saucepan which

stood upon the hearth.

"Why, I shouldn't wonder if you were hungry," said the young woman,

laying her baby in the cradle, and spreading a cloth on the round

table. "My husband will be home soon, and if you like to stay and

sup with him and me, you will be kindly welcome."

The old man's eyes sparkled when she said this, and he looked so

very old and seemed so weak that she pitied him. He turned a little

aside from the fire, and watched her while she set a brown loaf on

the table, and fried a few slices of bacon; but all was ready, and

the kettle had been boiling some time before there were any signs of

the husband's return.

"I never knew Will to be so late before," said the stranger. Perhaps

he is carrying his logs to the saw-pits."

"Will! exclaimed the wife. "What, you know my husband, then? I

thought you were a stranger in these parts."

"Oh, I have been past this place several times," said the old man,

looking rather confused; "and so, of course, I have heard of your

husband. Nobody's stroke in the wood is so regular and strong as

his."

"And I can tell you he is the handiest man at home," began his wife.

"Ah, ah," said the old man, smiling at her eagerness; "and here he

comes, if I am not mistaken."

At that moment the woodman entered.

"Will," said his wife, as she took his bill-hook from him, and hung

up his hat, "here's an old soldier come to sup with us, my dear." And as she spoke, she gave her husband a gentle push toward the old

man, and made a sign that he should speak to him.

"Kindly welcome, master," said the woodman. "Wife, I'm hungry; let's

to supper."

The wife turned some potatoes out of the little saucepan, set a jug

of beer on the table, and they all began to sup. The best of

everything was offered by the wife to the stranger. The husband,

after looking earnestly at him for a few minutes, kept silence.

"And where might you be going to lodge to-night, good man, if I'm

not too bold?" asked she.

The old man heaved a deep sigh, and said he supposed he must lie

out in the forest.

"Well, that would be a great pity," remarked his kind hostess. "No

wonder your bones ache if you have no better shelter." As she said

this, she looked appealingly at her husband.

"My wife, I'm thinking, would like to offer you a bed," said the

woodman; "at least, if you don't mind sleeping in this clean

kitchen, I think that we could toss you up something of that sort

that you need not disdain."

"Disdain, indeed!" said the wife. "Why, Will, when there's not a

tighter cottage than ours in all the wood, and with a curtain, as we

have, and a brick floor, and everything so good about us "

The husband laughed; the old man looked on with a twinkle in his

eye.

"I'm sure I shall be humbly grateful," said he.

Accordingly, when supper was over, they made him up a bed on the

floor, and spread clean sheets upon it of the young wife's own

spinning, and heaped several fresh logs on the fire. Then they

wished the stranger good night, and crept up the ladder to their own

snug little chamber.

"Disdain, indeed!" laughed the wife, as soon as they shut the door. "Why, Will, how could you say it? I should like to see him disdain

me and mine. It isn't often, I'll engage to say, that he sleeps in

such a well-furnished kitchen."

The husband said nothing, but secretly laughed to himself.

"What are you laughing at, Will?" said his wife, as she put out the

candle.

"Why, you soft little thing," answered the woodman, "didn't you see

that bunch of green ash-keys in his cap; and don't you know that

nobody would dare to wear them but the Ouphe of the Wood? I saw him

cutting those very keys for himself as I passed to the sawmill this

morning, and I knew him again directly, though he has disguised

himself as an old man."

"Bless us!" exclaimed the little wife; "is the Wood Ouphe in our

cottage? How frightened I am! I wish I hadn't put the candle out."

The husband laughed more and more.

"Will," said his wife, in a solemn voice, "I wonder how you dare

laugh, and that powerful creature under the very bed where you lie!"

"And she to be so pitiful over him," said the woodman, laughing till

the floor shook under him, "and to talk and boast of our house, and

insist on helping him to more potatoes, when he has a palace of his

own, and heaps of riches! Oh, dear! oh, dear!"

"Don't laugh, Will," said the wife, "and I'll make you the most

beautiful firmity [2]

you ever tasted tomorrow. Don't let him hear you laughing."

"Why, he comes for no harm," said the woodman. "I've never cut down

any trees that he had not marked, and I've always laid his toll of

the wood, neatly cut up, beside his foot-path, so I am not afraid. Besides, don't you know that he always pays where he lodges, and

very handsomely, too?"

"Pays, does he?" said the wife. "Well, but he is an awful creature

to have so near one. I would much rather he had really been an old

soldier. I hope he is not looking after my baby; he shall not have

him, let him offer ever so much."

The more the wife talked, the more the husband laughed at her fears,

till at length he fell asleep, whilst she lay awake, thinking and

thinking, till by degrees she forgot her fears, and began to wonder

what they might expect by way of reward. Hours appeared to pass away

during these thoughts. At length, to her great surprise, while it

was still quite dark, her husband called to her from below:

"Come down, Kitty; only come down to see what the Ouphe has left

us."

As quickly as possible Kitty started up and dressed herself, and ran

down the ladder, and then she saw her husband kneeling on the floor

over the knapsack, which the Ouphe had left behind him. Kitty rushed

to the spot, and saw the knapsack bursting open with gold coins,

which were rolling out over the brick floor. Here was good fortune! She began to pick them up, and count them into her apron. The more

she gathered, the faster they rolled, till she left off counting,

out of breath with joy and surprise.

"What shall we do with all this money?" said the delighted woodman.

They consulted for some time. At last they decided to bury it in the

garden, all but twenty pieces, which they would spend directly. Accordingly they dug a hole and carefully hid the rest of the money,

and then the woodman went to the town, and soon returned laden with

the things they had agreed upon as desirable possessions; namely, a

leg of mutton, two bottles of wine, a necklace for Kitty, some tea

and sugar, a grand velvet waistcoat, a silver watch, a large clock,

a red silk cloak, and a hat and feather for the baby, a quilted

petticoat, a great many muffins and crumpets, a rattle, and two new

pairs of shoes.

How enchanted they both were! Kitty cooked the nice things, and they

dressed themselves in the finery, and sat down to a very good

dinner. But, alas! the woodman drank so much of the wine that he

soon got quite tipsy, and began to dance and sing. Kitty was very

much shocked; but when he proposed to dig up some more of the gold,

and go to market for some more wine and some more blue velvet

waistcoats, she remonstrated very strongly. Such was the change that

had come over this loving couple, that they presently began to

quarrel, and from words the woodman soon got to blows, and, after

beating his little wife, lay down on the floor and fell fast asleep,

while she sat crying in a corner.

The next day they both felt very miserable, and the woodman had such

a terrible headache that he could neither eat nor work; but the day

after, being pretty well again, he dug up some more gold and went to

town, where he bought such quantities of fine clothes and furniture

and so many good things to eat, that in the end he was obliged to

buy a wagon to bring them home in, and great was the delight of his

wife when she saw him coming home on the top of it, driving the four

gray horses himself.

|

"Coming home on top of it, driving the four grey horses himself."

|

They soon

began to unpack the goods and lay them out on the grass, for the

cottage was far too small to hold them.

"There are some red silk curtains with gold rods," said the woodman.

"And grand indeed they are!" exclaimed his wife, spreading them over

the onion bed.

"And here's a great looking-glass," continued the woodman, setting

one up against the outside of the cottage, for it would not go in

the door.

So they went on handing down the things, and it took nearly the

whole afternoon to empty the wagon. No wonder, when it contained,

among other things, a coral and bells for the baby, and five very

large tea-trays adorned with handsome pictures of impossible

scenery, two large sofas covered with green damask, three bonnets

trimmed with feathers and flowers, two glass tumblers for them to

drink out of, for Kitty had decided that mugs were very vulgar

things, six books bound in handsome red morocco, a mahogany table,

a large tin saucepan, a spit and silver waiter, a blue coat with

gilt buttons, a yellow waistcoat, some pictures, a dozen bottles of

wine, a quarter of lamb, cakes, tarts, pies, ale, porter, gin, silk

stockings, blue and red and white shoes, lace, ham, mirrors, three

clocks, a four-post bedstead, and a bag of sugar candy.

These articles filled the cottage and garden; the wagon stood

outside the paling. Though the little kitchen was very much

encumbered with furniture, they contrived to make a fire in it; and,

having eaten a sumptuous dinner, they drank each other's health,

using the new tumblers to their great satisfaction.

"All these things remind me that we must have another house built,"

said Kitty.

"You may do just as you please about that, my dear," replied her

husband, with a bottle of wine in his hand.

"My dear," said Kitty, "how vulgar you are! Why don't you drink out

of one of our new tumblers, like a gentleman?"

The woodman refused, and said it was much more handy to drink it out

of the bottle.

"Handy, indeed!" retorted Kitty; "yes, and by that means none will

be left for me."

Thereupon another quarrel ensued, and the woodman, being by this

time quite tipsy, beat his wife again. The next day they went and

got numbers of workmen to build them a new house in their garden. It

was quite astonishing even to Kitty, who did not know much about

building, to see how quick these workmen were; in one week the house

was ready. But in the meantime the woodman, who had very often been

tipsy, felt so unwell that he could not look after them; therefore

it is not surprising that they stole a great many of his fine

things while he lay smoking on the green damask sofa which stood on

the carrot bed. Those articles which the workmen did not steal the

rain and dust spoilt; but that they thought did not much matter, for

still more than half the gold was left; so they soon furnished the

new house. And now Kitty had a servant, and used to sit every

morning on a couch dressed in silks and jewels till dinner-time,

when the most delicious hot beefsteaks and sausage padding or roast

goose were served up, with more sweet pies, fritters, tarts, and

cheese-cakes than they could possibly eat. As for the baby, he had

three elegant cots, in which he was put to sleep by turns; he was

allowed to tear his picture-books as often as he pleased, and to eat

so many sugar-plums and macaroons that they often made him quite

ill.

The woodman looked very pale and miserable, though he often said

what a fine thing it was to be rich. He never thought of going to

his work, and used generally to sit in the kitchen till dinner was

ready, watching the spit. Kitty wished she could see him looking as

well and cheerful as in old days, though she felt naturally proud

that her husband should always be dressed like a gentleman, namely,

in a blue coat, red waistcoat, and top-boots.

He and Kitty could never agree as to what should be done with the

rest of the money; in fact, no one would have known them for the

same people; they quarrelled almost every day, and lost nearly all

their love for one another. Kitty often cried herself to sleep a

thing she had never done when they were poor; she thought it was

very strange that she should be a lady, and yet not be happy. Every

morning when the woodman was sober they invented new plans for

making themselves happy, yet, strange to say, none of them

succeeded, and matters grew worse and worse. At last Kitty thought

she should be happy if she had a coach; so she went to the place

where the knapsack was buried, and began to dig; but the garden was

so trodden down that she could not dig deep enough, and soon got

tired of trying. At last she called the servant, and told her the

secret as to where the money was, promising her a gold piece if she

could dig it up. The servant dug with all her strength, and with a

great deal of trouble they got the knapsack up, and Kitty found that

not many gold pieces were left. However, she resolved to have the

coach, so she took them and went to the town, where she bought a

yellow chariot, with a most beautiful coat of arms upon it, and two

cream-colored horses to draw it.

In the meantime the maid ran to the magistrates, and told them she

had discovered something very dreadful, which was, that her mistress

had nothing to do but dig in the ground and that she could make

money come coined money: "which," said the maid, "is a very

terrible thing, and it proves that she must be a witch."

The mayor and aldermen were very much shocked, for witches were

commonly believed in in those days; and when they heard that Kitty

had dug up money that very morning, and bought a yellow coach with

it, they decided that the matter must be investigated.

When Kitty drove up to her own door, she saw the mayor and aldermen

standing in the kitchen waiting for her. She demanded what they

wanted, and they said they were come in the king's name to search

the house.

Kitty immediately ran up-stairs and took the baby out of his cradle,

lest any of them should steal him, which, of course, seemed a very

probable thing for them to do. Then she went to look for her

husband, who, shocking to relate, was quite tipsy, quarrelling and

arguing with the mayor, and she actually saw him box an alderman's

ears.

"The thing is proved," said the indignant mayor; "this woman is

certainly a witch."

Kitty was very much bewildered at this; but how much more when she

saw her husband seize the mayor yes, the very mayor himself and

shake him so hard that he actually shook his head off, and it rolled

under the dresser! "If I had not seen this with my own eyes," said

Kitty, "I could not have believed it even now it does not seem at

all real."

All the aldermen wrung their hands.

"Murder! murder!" cried the maid.

"Yes," said the aldermen, "this woman and her husband must

immediately be put to death, and the baby must be taken from them

and made a slave."

In vain Kitty fell on her knees; the proofs of their guilt were so

plain that there was no hope for mercy; and they were just going to

be led out to execution when why, then she opened her eyes, and

saw that she was lying in bed in her own little chamber where she

had lived and been so happy; her baby beside her in his wicker [3]

cradle was crowing and sucking his fingers.

"So, then, I have never been rich, after all," said Kitty;

"and it

was all only a dream! I thought it was very strange at the time that

a man's head should roll off."

And she heaved a deep sigh, and put her hand to her face, which was

wet with the tears she had shed when she thought that she and her

husband were going to be executed.

"I am very glad, then, my husband is not a drunken man; and he does

not beat me; but he goes to work every day, and I am as happy as a

queen."

Just then she heard her husband's good-tempered voice whistling as

he went down the ladder.

"Kitty, Kitty," said be, "come, get up, my little woman; it's later

than usual, and our good visitor will want his breakfast."

"Oh, Will, Will, do come here," answered the wife; and presently her

husband came up again, dressed in his fustian jacket, and looking

quite healthy and good-tempered not at all like the pale man in

the blue coat, who sat watching the meat while it roasted.

"Oh, Will, I have had such a frightful dream," said Kitty, and she

began to cry; "we are not going to quarrel and hate each other, are

we?"

"Why, what a silly little thing thou art to cry about a dream," said

the woodman, smiling. "No, we are not going to quarrel as I know of. Come, Kitty, remember the Ouphe."

"Oh, yes, yes, I remember," said Kitty, and she made haste to dress

herself and come down.

"Good morning, mistress; how have you slept?" said the Ouphe, in a

gentle voice, to her.

"Not so well as I could have wished, sir," said Kitty.

The Ouphe smiled. "I slept very well," he said. "The supper was

good, and kindly given, without any thought of reward."

"And that is the certain truth," interrupted Kitty: "I never had

the least thought what you were till my husband told me."

The woodman had gone out to cut some fresh cresses for his guest's

breakfast.

"I am sorry, mistress," said the Ouphe, "that you slept uneasily

my race are said sometimes by their presence to affect the dreams of

you mortals. Where is my knapsack? Shall I leave it behind me in

payment of bed and board?"

"Oh, no, no, I pray you don't," said the little wife, blushing and

stepping back; "you are kindly welcome to all you have had, I'm

sure: don't repay us so, sir."

"What, mistress, and why not?" asked the Ouphe, smiling. "It is as

full of gold pieces as it can hold, and I shall never miss them."

"No, I entreat you, do not," said Kitty, "and do not offer it to my

husband, for maybe he has not been warned as I have."

Just then the woodman came in.

"I have been thanking your wife for my good entertainment," said the

Ouphe, "and if there is anything in reason that I can give either of

you "

"Will, we do very well as we are," said his wife, going up to him

and looking anxiously in his face.

"I don't deny," said the woodman, thoughtfully, "that there are one

or two things I should like my wife to have, but somehow I've not

been able to get them for her yet."

"What are they?" asked the Ouphe.

"One is a spinning-wheel," answered the woodman; "she used to spin

a good deal when she was at home with her mother."

"She shall have a spinning-wheel," replied the Ouphe; "and is there

nothing else, my good host?"

"Well," said the woodman, frankly, "since you are so obliging, we

should like a hive of bees."

"The bees you shall have also; and now, good morning both, and a

thousand thanks to you."

So saying, he took his leave, and no pressing could make him stay to

breakfast.

"Well," thought Kitty, when she had had a little time for

reflection, "a spinning-wheel is just what I wanted; but if people

had told me this time yesterday morning that I should be offered a

knapsack full of money, and should refuse it, I could not possibly

have believed them!"

FOOTNOTES

1. Ouphe, pronounced "oof," is an old-fashioned word for

goblin or elf.

2. Firmity: generally written frumenty; wheat boiled in milk with

sugar and fruit.

3. Wicker: made of willow twigs like a basket.

――――♦――――

|

|

THE FAIRY WHO JUDGED HER

NEIGHBOURS.

THERE was once a

Fairy who was a good Fairy, on the whole, but she had one very bad

habit; she was too fond of finding fault with other people, and of

taking for granted that everything must be wrong if it did not

appear right to her.

One day, when she had been talking very unkindly of some

friends of hers, her mother said to her: "My child, I think if you

knew a little more of the world, you would become more charitable.

I would therefore advise you to set out on your travels; you will

find plenty of food, for the cowslips are now in bloom, and they

contain excellent honey. I need not be anxious about your

lodging, for there is no place more delightful for sleeping in than

an empty robin's nest when the young have flown. And if you

want a new gown, you can sew two tulip leaves together, which will

make you a very becoming dress, and one that I should be proud to

see you in."

The young Fairy was pleased at this permission to set out on

her travels; so she kissed her mother, and bade good-by to her

nurse, who gave her a little ball of spiders' threads to sew with,

and a beautiful little box, made of the egg-shell of a wren, to keep

her best thimble in, and took leave of her, wishing her safe home

again.

The young Fairy then flew away till she came to a large

meadow, with a clear river flowing on one side of it, and some tall

oak-trees on the other. She sat down on a high branch in one

of these oaks, and, after her long flight, was thinking of a nap,

when, happening to look down at her little feet, she observed that

her shoes were growing shabby and faded. "Quite a disgrace, I

declare," said she. "I must look for another pair.

Perhaps two of the smallest flowers of that snapdragon which I see

growing in the hedge would fit me. I think I should like a

pair of yellow slippers." So she flew down, and, after a

little trouble, she found two flowers which fitted her very neatly,

and she was just going to return to the oak-tree, when she heard a

deep sigh beneath her, and, peeping out from her place among the

hawthorn blossoms, she saw a fine young Lark sitting in the long

grass, and looking the picture of misery.

"What is the matter with you, cousin?" asked the Fairy.

"Oh, I am so unhappy," replied the poor Lark; "I want to

build a nest, and I have got no wife."

"Why don't you look for a wife, then?" said the Fairy,

laughing at him. "Do you expect one to come and look for you?

Fly up, and sing a beautiful song in the sky, and then perhaps some

pretty hen will hear you; and perhaps, if you tell her that you will

help her to build a capital nest, and that you will sing to her all

day long, she will consent to be your wife."

"Oh, I don't like," said the Lark, "I don't like to fly up, I

am so ugly. If I were a goldfinch, and had yellow bars on my

wings, or a robin, and had red feathers on my breast, I should not

mind the defect which now I am afraid to show. But I am only a

poor brown Lark, and I know I shall never get a wife."

"I never heard of such an unreasonable bird," said the Fairy.

"You cannot expect to have everything."

"Oh, but you don't know," proceeded the Lark, that if I fly

up my feet will be seen; and no other bird has feet like mine.

My claws are enough to frighten any one, they are so long; and yet I

assure you, Fairy, I am not a cruel bird."

"Let me look at your claws," said the Fairy.

So the Lark lifted up one of his feet, which he had kept

hidden in the long grass, lest any one should see

"It looks certainly very fierce," said the Fairy. "Your

hind claw is at least an inch long, and all your toes have very

dangerous-looking points. Are you sure you never use them to

fight with?"

"No, never!" said the Lark, earnestly; "I never fought a

battle in my life; but yet these claws grow longer and longer, and I

am so ashamed of their being seen that I very often lie in the grass

instead of going up to sing, as I could wish."

"I think, if I were you, I would pull them off," said the

Fairy.

"That is easier said than done," answered the poor Lark.

"I have often got them entangled in the grass, and I scrape them

against the hard clods; but it is of no use, you cannot think how

fast they stick."

"Well, I am sorry for you," observed the Fairy; "but at the

same time I cannot but see that, in spite of what you say, you must

be a quarrelsome bird, or you would not have such long spurs."

"That is just what I am always afraid people will say,"

sighed the Lark.

"For," proceeded the Fairy, "nothing is given us to be of no

use. You would not have wings unless you were to fly, nor a

voice unless you were to sing; and so you would not have those

dreadful spurs unless you were going to fight. If your spurs

are not to fight with," continued the unkind Fairy, "I should like

to know what they are for?"

"I am sure I don't know," said the Lark, lifting up his foot

and looking at it. "Then you are not inclined to help me at

all, Fairy? I thought you might be willing to mention among my

friends that I am not a quarrelsome bird, and that I should always

take care not to hurt my wife and nestlings with my spurs."

"Appearances are very much against you," answered the Fairy;

"and it is quite plain to me that those spurs are meant to scratch

with. No, I cannot help you. Good morning."

So the Fairy withdrew to her oak bough, and the poor Lark sat

moping in the grass while the Fairy watched him. "After all,"

she thought, "I am sorry he is such a quarrelsome fellow, for that

he is such is fully proved by those long spurs."

While she was so thinking, the Grasshopper came chirping up

to the Lark, and tried to comfort him.

"I have heard all that the Fairy said to you," he observed,

"and I really do not see that it need make you unhappy. I have

known you some time, and have never seen you fight or look out of

temper; therefore I will spread a report that you are a very

good-tempered bird, and that you are looking out for a wife."

The Lark upon this thanked the Grasshopper warmly.

"At the same time," remarked the Grasshopper, "I should be

glad if you could tell me what is the use of those claws, because

the question might be asked me, and I should not know what to

answer."

"Grasshopper," replied the Lark, "I cannot imagine what they

are for that is the real truth."

"Well," said the kind Grasshopper, "perhaps time will show."

So he went away, and the Lark, delighted with his promise to

speak well of him, flew up into the air, and the higher he went the

sweeter and the louder he sang. He was so happy, and he poured

forth such delightful notes, so clear and thrilling, that the little

ants who were carrying grains to their burrow stopped and put down

their burdens to listen; and the doves ceased cooing, and the little

field-mice came and sat in the openings of their holes; and the

Fairy, who had just begun to doze, woke up delighted; and a pretty

brown Lark, who had been sitting under some great foxglove leaves,

peeped out and exclaimed, "I never heard such a beautiful song in my

life never!"

"It was sung by my friend, the Skylark," said the

Grasshopper, who just then happened to be on a leaf near her.

"He is a very good-tempered bird, and he wants a wife."

"Hush!" said the pretty brown Lark. "I want to hear the

end of that wonderful song."

For just then the Skylark, far up in the heaven, burst forth

again, and sang better than ever so well, indeed, that every

creature in the field sat still to listen; and the little brown Lark

under the foxglove leaves held her breath, for she was afraid of

losing a single note.

"Well done, my friend!" exclaimed the Grasshopper, when at

length he came down panting, and with tired wings; and then he told

him how much his friend the brown Lark, who lived by the foxglove,

had been pleased with his song, and he took the poor Skylark to see

her.

The Skylark walked as carefully as he could, that she might

not see his feet; and he thought he had never seen such a pretty

bird in his life. But when she told him how much she loved

music, he sprang up again into the blue sky as if he was not at all

tired, and sang anew, clearer and sweeter than before. He was

so glad to think that he could please her.

He sang several songs, and the Grasshopper did not fail to

praise him, and say what a cheerful, kind bird he was. The

consequence was, that when he asked the brown Lark to overlook his

spurs and be his wife, she said:

"I will see about it, for I do not mind your spurs

particularly."

"I am very glad of that," said the Skylark. "I was

afraid you would disapprove of them."

"Not at all," she replied. "On the contrary, now I

think of it, I should not have liked you to have short claws like

other birds; but I cannot exactly say why, for they seem to be of no

use in particular."

This was very good news for the Skylark, and he sang such

delightful songs in consequence, that he very soon won his wife; and

they built a delightful little nest in the grass, which made him so

happy that he almost forgot to be sorry about his long spurs.

The Fairy, meanwhile, flew about from field to field, and I

am sorry to say that she seldom went anywhere without saying

something unkind or ill-natured; for, as I told you before, she was

very hasty, and had a sad habit of judging her neighbours.

She had been several days wandering about in search of

adventures, when one afternoon she came back to the old oak-tree,

because she wanted a new pair of shoes, and there were none to be

had so pretty as those made of the yellow snapdragon flower in the

hedge hard by.

While she was fitting on her shoes, she saw the Lark's

friend.

|

"While she was fitting on her shoes, she saw the Lark's friend."

|

"How do you do, Grasshopper?" asked the Fairy.

"Thank you, I am very well and very happy," said the

Grasshopper; "people are always so kind to me."

"Indeed!" replied the Fairy. "I wish I could say that

they were always kind to me. How is that quarrelsome Lark who

found such a pretty brown mate the other day?"

"He is not a quarrelsome bird indeed," replied the

Grasshopper. "I wish you would not say that he is."

"Oh, well, we need not quarrel about that," said the Fairy,

laughing; "I have seen the world, Grasshopper, and I know a few

things, depend upon it. Your friend the Lark does not wear

those long spurs for nothing."

The Grasshopper did not choose to contend with the Fairy, who

all this time was busily fitting yellow slippers to her tiny feet.

When, however, she had found a pair to her mind

"Suppose you come and see the eggs that our pretty friend the

Lark has got in her nest," asked the Grasshopper. "Three pink

eggs spotted with brown. I am sure she will show them to you

with pleasure."

Off they set together; but what was their surprise to find

the poor little brown Lark sitting on them with rumpled feathers,

drooping head, and trembling limbs.

"Ah, my pretty eggs!" said the Lark, as soon as she could

speak, "I am so miserable about them they will be trodden on, they

will certainly be found."

"What is the matter?" asked the Grasshopper. "Perhaps

we can help you."

"Dear Grasshopper," said the Lark, "I have just heard the

farmer and his son talking on the other side of the hedge, and the

farmer said that to-morrow morning he should begin to cut this

meadow."

"That is a great pity," said the Grasshopper. "What a

sad thing it was that you laid your eggs on the ground!"

"Larks always do," said the poor little brown bird; and I did

not know how to make a fine nest such as those in the hedges.

Oh, my pretty eggs! my heart aches for them! I shall never

hear my little nestlings chirp!"

So the poor Lark moaned and lamented, and neither the

Grasshopper nor the Fairy could do anything to help her. At

last her mate dropped down from the white cloud where he had been

singing, and when he saw her drooping, and the Grasshopper and the

Fairy sitting silently before her, he inquired in a great fright

what the matter was.

So they told him, and at first he was very much shocked; but

presently he lifted first one and then the other of his feet, and

examined his long spurs.

"He does not sympathize much with his poor mate," whispered

the Fairy; but the Grasshopper took no notice of the speech.

Still the Lark looked at his spurs, and seemed to be very

deep in thought.

"If I had only laid my eggs on the other side of the hedge,"

sighed the poor mother, "among the corn, there would have been

plenty of time to rear my birds before harvest time."

"My dear," answered her mate, "don't be unhappy." And

so saying, he hopped up to the eggs, and laying one foot upon the

prettiest, he clasped it with his long spurs. Strange to say,

it exactly fitted them.

"Oh, my clever mate!" cried the poor little mother, reviving;

"do you think you can carry them away for me?"

"To be sure I can," replied the Lark, beginning slowly and

carefully to hop on with the egg in his right foot; "nothing more

easy. I have often thought it was likely that our eggs would

be disturbed in this meadow; but it never occurred to me till this

moment that I could provide against this misfortune. I have

often wondered what my spurs could be for, and now I see." So

saying, he hopped gently on till he came to the hedge, and then got

through it, still holding the egg, till he found a nice little

hollow place in among the corn, and there he laid it and came back

for the others.

"'To be sure I can,' replied the Lark."

"Hurrah!" cried the Grasshopper, "Larkspurs forever!"

The Fairy said nothing, but she felt heartily ashamed of

herself. She sat looking on till the happy Lark had carried

the last of his eggs to a safe place, and had called his mate to

come and sit on them. Then, when he sprang up into the sky

again, exulting and rejoicing and singing to his mate that now he

was quite happy, because he knew what his long spurs were for, she

stole gently away, saying to herself, "Well, I could not have

believed such a thing. I thought he must be a quarrelsome bird

as his spurs were so long; but it appears that I was wrong, after

all."

――――♦――――

THE PRINCE'S DREAM

IF we may credit

the fable, there is a tower in the midst of a great Asiatic plain,

wherein is confined a prince who was placed there in his earliest

infancy, with many slaves and attendants, and all the luxuries that

are compatible with imprisonment.

Whether he was brought there from some motive of state,

whether to conceal him from enemies, or to deprive him of rights,

has not transpired; but it is certain that up to the date of this

little history he had never set his foot outside the walls of that

high tower, and that of the vast world without he knew only the

green plains which surrounded it; the flocks and the birds of that

region were all his experience of living creatures, and all the men

he saw outside were shepherds.

And yet he was not utterly deprived of change, for sometimes

one of his attendants would be ordered away, and his place would be

supplied by a new one. The prince would never weary of

questioning this fresh companion, and of letting him talk of cities,

of ships, of forests, of merchandise, of kings; but though in turns

they all tried to satisfy his curiosity, they could not succeed in

conveying very distinct notions to his mind; partly because there

was nothing in the tower to which they could compare the external

world, partly because, having chiefly lived lives of seclusion and

indolence in Eastern palaces, they knew it only by hearsay

themselves.

At length, one day, a venerable man of a noble presence was

brought to the tower, with soldiers to guard him and slaves to

attend him. The prince was glad of his presence, though at

first he seldom opened his lips, and it was manifest that

confinement made him miserable. With restless feet he would

wander from window to window of the stone tower, and mount from

story to story; but mount as high as he would there was still

nothing to be seen but the vast, unvarying plain, clothed with

scanty grass, and flooded with the glaring sunshine; flocks and

herds and shepherds moved across it sometimes, but nothing else, not

even a shadow, for there was no cloud in the sky to cast one.

The old man, however, always treated the prince with respect, and

answered his questions with a great deal of patience, till at length

he found a pleasure in satisfying his curiosity, which so much

pleased the poor young prisoner, that, as a great condescension, be

invited him to come out on the roof of the tower and drink sherbet

with him in the cool of the evening, and tell him of the country

beyond the desert, and what seas are like, and mountains, and towns.

"I have learnt much from my attendants, and know this world

pretty well by hearsay," said the prince, as they reclined on the

rich carpet which was spread on the roof.

The old man smiled, but did not answer; perhaps because he

did not care to undeceive his young companion, perhaps because so

many slaves were present, some of whom were serving them with fruit,

and others burning rich odours on a little chafing-dish that stood

between them.

"But there are some words to which I never could attach any

particular meaning," proceeded the prince, as the slaves began to

retire, "and three in particular that my attendants cannot satisfy

me upon, or are reluctant to do so."

"What words are those, my prince?" asked the old man.

The prince turned on his elbow to be sure that the last slave had

descended the tower stairs, then replied:

"O man of much knowledge, the words are these Labour, and

Liberty, and Gold."

"Prince," said the old man, "I do not wonder that it has been

hard to make thee understand the first, the nature of it, and the

cause why most men are born to it; as for the second, it would be

treason for thee and me to do more than whisper it here, and sigh

for it when none are listening; but the third need hardly puzzle

thee; thy hookah [1]

is bright with it; all thy jewels are set in it; gold is inlaid in

the ivory of thy bath; thy cup and thy dish are of gold, and golden

threads are wrought into thy raiment."

"That is true," replied the prince, "and if I had not seen

and handled this gold, perhaps I might not find its merits so hard

to understand; but I possess it in abundance, and it does not feed

me, nor make music for me, nor fan me when the sun is hot, nor cause

me to sleep when I am weary; therefore when my slaves have told me

how merchants go out and brave the perilous wind and sea, and live

in the unstable ships, and run risks from shipwreck and pirates, and

when, having asked them why they have done this, they have answered,

'For gold,' I have found it hard to believe them; and when they have

told me how men have lied, and robbed, and deceived; how they have

murdered one another, and leagued together to depose kings, to

oppress provinces, and all for gold then I have said to myself,

either my slaves have combined to make me believe that which is not,

or this gold must be very different from the yellow stuff that this

coin is made of, this coin which is of no use but to have a hole

pierced through it and hang to my girdle, that it may tinkle when I

walk."

"Notwithstanding this," said the old man, "nothing can be

done without gold; for it is better than bread, and fruit, and

music, for it can buy them all, since all men love it, and have

agreed to exchange it for whatever they may need."

"How so?" asked the prince.

"If a man has many loaves he cannot eat them all," answered

the old man; "therefore he goes to his neighbour and says, 'I have

bread and thou hast a coin of gold let us exchange;' so he

receives the gold and goes to another man, saying, 'Thou hast two

houses and I have none; lend me one of thy houses to live in, and I

will give thee my gold;' thus again they exchange."

"It is well," said the prince; "but in time of drought, if

there is no bread in a city, can they make it of gold?"

"Not so," answered the old man, "but they must send their

gold to a city where there is food, and bring that back instead of

it."

"But if there was a famine all over the world," asked the

prince, "what would they do then?"

"Why, then, and only then," said the old man, they must

starve, and the gold would be nought, for it can only be changed for

that which is; it cannot make that which is not."

"And where do they get gold?" asked the prince. "Is it

the precious fruit of some rare tree, or have they whereby they can

draw it down from the sky at sunset? "

"Some of it," said the old man, "they dig out of the ground."

Then he told the prince of ancient rivers running through

terrible deserts, whose sands glitter with golden grains and are

yellow in the fierce heat of the sun, and of dreary mines where the

Indian slaves work in gangs tied together, never seeing the light of

day; and lastly (for he was a man of much knowledge, and had

travelled far), he told him of the valley of the, Sacramento in the

New World, and of those mountains where the people of Europe send

their criminals, and where now their free men pour forth to gather

gold, and dig for it as hard as if for life; sitting up by it at

night lest any should take it from them, giving up houses and

country, and wife and children, for the sake of a few feet of mud,

whence they dig clay that glitters as they wash it; and how they

sift it and rock it as patiently as if it were their own children in

the cradle, and afterward carry it in their bosoms, and forego on

account of it safety and rest.

"But, prince," he went on, seeing that the young man was

absorbed in his narrative, "if you would pass your word to me never

to betray me, I would procure for you a sight of the external world,

and in a trance you should see those places where gold is dug, and

traverse those regions forbidden to your mortal footsteps."

Upon this, the prince threw himself at the old man's feet,

and promised heartily to observe the secrecy required, and entreated

that, for however short a time, he might be suffered to see this

wonderful world.

Then, if we may credit the story, the old man drew nearer to

the chafing-dish which stood between them, and having fanned the

dying embers in it, cast upon them a certain powder and some herbs,

from whence as they burnt a peculiar smoke arose. As their

vapours spread, he desired the prince to draw near and inhale them,

and then (says the fable) assured him that when he should sleep he

would find himself, in his dream, at whatever place he might desire,

with this strange advantage, that he should see things in their

truth and reality as well as in their outward shows.

So the prince, not without some fear, prepared to obey; but

first he drank his sherbet, and handed over the golden cup to the

old man by way of recompense; then he reclined beside the

chafing-dish and inhaled the heavy perfume till he became

overpowered with sleep, and sank down upon the carpet in a dream.

"Then he reclined beside the chafing-dish and inhaled

the heavy perfume."

The prince knew not where he was, but a green country was

floating before him, and he found himself standing in a marshy

valley where a few wretchθd

cottages were scattered here and there with no means of

communication. There was a river, but it had overflowed its

banks and made the central land impassable, the fences had been

broken down by it, and the fields of corn laid low; a few wretchθd

peasants were wandering about there; they looked half-clad and

half-starved. "A miserable valley, indeed!" exclaimed the

prince; but as he said it a man came down from the hills with a

great bag of gold in his hand.

"This valley is mine," said he to the people; "I have bought

it for gold. Now make banks that the river may not overflow,

and I will give you gold; also make fences and plant fields, and

cover in the roofs of your houses, and buy yourselves richer

clothing." So the people did so, and as the gold got lower in

the bag the valley grew fairer and greener, till the prince

exclaimed, "O gold, I see your value now! O wonderful,

beneficent gold!"

But presently the valley melted away like a mist, and the

prince saw an army besieging a city; he heard a general haranguing

his soldiers to urge them on, and the soldiers shouting and

battering the walls; but shortly, when the city was well-nigh taken,

he saw some men secretly giving gold among the soldiers, so much of

it that they threw down their arms to pick it up, and said that the

walls were so strong that they could not throw them down. "O

powerful gold!" thought the prince thou art stronger than the city

walls!"

After that it seemed to him that he was walking about in a

desert country, and in his dream he thought, "Now I know what labour

is, for I have seen it, and its benefits; and I know what liberty

is, for I have tasted it; I can wander where I will, and no man

questions me; but gold is more strange to me than ever, for I have

seen it buy both liberty and labour." Shortly after this he

saw a great crowd digging upon a barren hill, and when he drew near

be understood that he was to see the place whence the gold came.

He came up and stood a long time watching the people as they

toiled ready to faint in the sun, so great was the labour of digging

up the gold.

He saw some who had much and could not trust any one to help

them to carry it, binding it in bundles over their shoulders, and

bending and groaning under its weight; he saw others hide it in the

ground, and watch the place clothed in rags, that none might suspect

that they were rich; but some, on the contrary, who had dug up an

unusual quantity, he saw dancing and singing, and vaunting their

success, till robbers waylaid them when they slept, and rifled their

bundles and carried their golden sand away.

"All these men are mad," thought the prince, "and this

pernicious gold has made them so."

After this, as he wandered here and there, he saw groups of

people smelting the gold under the shadow of the trees, and he

observed that a dancing, quivering vapour rose up from it which

dazzled their eyes, and distorted everything that they looked at;

arraying it also in different colours from the true one. He

observed that this vapour from the gold caused all things to rock

and reel before the eyes of those who looked through it, and also,

by some strange affinity, it drew their hearts toward those who

carried much gold on their persons, so that they called them good

and beautiful; it also caused them to see darkness and dullness in

the faces of those who had carried none. "This," thought the

prince, "is very strange;" but not being able to explain it, he went

still farther, and there he saw more people. Each of these had

adorned himself with a broad golden girdle, and was sitting in the

shade, while other men waited on them.

"What ails these people?" he inquired of one who was looking

on, for he observed a peculiar air of weariness and dullness in

their faces. He was answered that the girdles were very tight

and heavy, and being bound over the regions of the heart, were

supposed to impede its action, and prevent it from beating high, and

also to chill the wearer, as, being of opaque material, the warm

sunshine of the earth could not get through to warm them.

"Why, then, do they not break them asunder," exclaimed the

prince, "and fling them away?"

"Break them asunder!" cried the man; "why, what a madman you

must be; they are made of the purest gold!"

"Forgive my ignorance," replied the prince; "I am a

stranger."

So he walked on, for feelings of delicacy prevented him from

gazing any longer at the men with the golden girdles; but as he went

he pondered on the misery he had seen, and thought to himself that

this golden sand did more mischief than all the poisons of the

apothecary; for it dazzled the eyes of some, it strained the hearts

of others, it bowed down the heads of many to the earth with its

weight; it was a sore labour to gather it, and when it was gathered

the robber might carry it away; it would be a good thing, he

thought, if there were none of it.

After this he came to a place where were sitting some agθd

widows and some orphan children of the gold-diggers, who were

helpless and destitute; they were weeping and bemoaning themselves,

but stopped at the approach of a man whose appearance attracted the

prince, for he had a very great bundle of gold on his back, and yet

it did not bow him down at all; his apparel was rich, but he had no

girdle on, and his face was anything but sad.

"Sir," said the prince to him, "you have a great burden; you

are fortunate to be able to stand under it."

"I could not do so," he replied, "only that as I go on I keep

lightening it;" and as he passed each of the widows, he threw gold

to her, and, stooping down, hid pieces of it in the bosoms of the

children.

"'I could not do so,' he replied, 'only that as I go

on I keep lightening it.'"

"You have no girdle," said the prince.

"I once had one," answered the gold-gatherer; "but it was so

tight over my breast that my heart grew cold under it, and almost

ceased to beat. Having a great quantity of gold on my back, I

felt almost at the last gasp; so I threw off my girdle, and being on

the bank of a river, which I knew not how to cross, I was about to

fling it in, I was so vexed! 'But no,' thought I, 'there are

many people waiting here to cross besides myself. I will make

my girdle into a bridge, and we will cross over on it.'"

"Turn your girdle into a bridge!" said the prince,

doubtfully, for he did not quite understand.

The man explained himself.

"And, then, sir, after that," he continued, "I turned

one-half of my burden into bread, and gave it to these poor people.

Since then I have not been oppressed by its weight, however heavy it

may have been; for few men have a heavier one. In fact, I

gather more from day to day."

As the man kept speaking, he scattered his gold right and

left with a cheerful countenance, and the prince was about to reply,

when suddenly a great trembling under his feet made him fall to the

ground. The refining fires of the gold-gatherers sprang up

into flames, and then went out; night fell over everything on the

earth, and nothing was visible in the sky but the stars of the

southern cross.

"It is past midnight," thought the prince, "for the stars of

the cross begin to bend."

He raised himself upon his elbow, and tried to pierce the

darkness, but could not. At length a slender blue flame darted

out, as from ashes in a chafing-dish, and by the light of it he saw

the strange pattern of his carpet and the cushions lying about.

He did not recognize them at first, but presently he knew that he

was lying in his usual place, at the top of his tower.

"Wake up, prince," said the old man.

The prince sat up and sighed, and the old man inquired what

he had seen.

"O man of much learning!" answered the prince, "I have seen

that this is a wonderful world; I have seen the value of labour, and

I know the uses of it; I have tasted the sweetness of liberty, and

am grateful, though it was but in a dream; but as for that other

word that was so great a mystery to me, I only know this, that it

must remain a mystery forever, since I am fain to believe that all

men are bent on getting it; though, once gotten, it causeth them

endless disquietude, only second to their discomfort that are

without it. I am fain to believe that they can procure with it

whatever they most desire, and yet that it cankers their hearts and

dazzles their eyes; that it is their nature and their duty to gather

it; and yet that, when once gathered, the best thing they can do is

to scatter it!"

The next morning, when he awoke, the old man was gone.

He had taken with him the golden cup. And the sentinel was

also gone, none knew whither. Perhaps the old man had turned

his golden cup into a golden key.

FOOTNOTE.

1. Hookah: a kind of pipe for smoking tobacco, used

in Eastern Europe and Asia.

――――♦――――

THE WATER-LILY

MY father and

mother were gone out for the day, and had left me charge of the

children. It was very hot, and they kept up a continual fidget. I

bore it patiently for some time, for children will be restless in

hot weather, but at length I requested that they would get something

to do.

"Why don't you work, or paint, or read, Hatty? I demanded of my

little sister.

"I'm tired of always grounding those swans," said Harriet, "and my

crochet is so difficult; I seem to do it quite right, and yet it

comes wrong."

"Then why don't you write your diary?

"Oh, because Charlie won't write his."

"A very bad reason; his not writing leaves you the more to say;

besides, I thought you promised mamma you would persevere if she

would give you a book."

"And so we did for a long time," said Charlie; "why, I wrote pages

and pages of mine. Look here!"

So saying, he produced a copy-book with a marbled cover, and showed

me that it was about half-full of writing in large text.

"If you wrote all that yourself, I should think you might write

more."

"Oh, but I am so tired of it, and besides, this is such a very hot

day."

"I know that, and to have you leaning on my knee makes me no cooler;

but I have something for you to do just now, which I think you will

like."

"Oh, what is it, sister? May we both do it?"

"Yes, if you like. You may go into the field to gardener, and ask

him to get me a water-lily out of the stream; I want one to finish

my sketch with."

"You really do want one? you are not pretending, just to give us

something to do?

"No, I really want one; you see these in the glass begin to wither."

"Make haste then, Hatty. Sister, you shall have the very best lily

we can find."

Thereupon they ran off, leaving me to inspect the diary. Its first

page was garnished with the resemblance of a large swan with curly

wings; from his beak proceeded the owner's name in full, and

underneath were his lucubration. The first few pages ran as follows:

"Wednesday. To-day mamma said, as all the others were writing

diaries, I might do one too if I liked, so I said I should, and I

shall write it every day till I am grown up. I did a long division

sum, a very hard one. We dined early to-day, and we had a boiled leg

of mutton and an apple pudding, but I shall not say another time

what we had for dinner, because I shall have plenty of other things

to say."

"Friday. Gardener has been mending the palings; he gave me

five nails; they were very good ones, such as I like. He said if any

boy that he knew was to pull nails out of his wall trees when he'd

done them, he should certainly tell their papa of them. Aunt Fanny

came and took away Sophy to spend a fortnight. Uncle Tom came too;

he said I was a fine boy, and gave me a shilling."

"Saturday. My half-holiday. Hurrah! I went and bought two

hoop-sticks for me and Hatty; they cost four-pence each."

"Sunday. On Sunday I went to church."

"Monday. To-day I had a cold, and after school I was just

going to bowl my hoop when Orris said to mamma it rained, and ma

said she couldn't think of my going out in the rain, and so I

couldn't go. After that Orris called me to come into her room, and

gave me a four-penny piece and two pictures, so now I've got

eight-pence. Orris is very kind, but sometimes she thinks she ought

to command, because she is the eldest."

"Tuesday. I shall not write my diary every day, unless I

like."

"Wednesday. I dined late with papa and mamma and the elder

ones: it rained. If the others won't tell me what to say, of course

I don't know."

"Friday. I went to the shop and bought some tin tax. I don't

like writing diaries particularly. It will be a good thing to leave

off till the holidays."

I had only got so far when the children ran in with a beautiful

water-lily. They had scarcely deposited it in my hand when they both

exclaimed in a breath:

"And what are we to do now?"

"You may bring me a glass of water to put it in."

This was soon done, and then the question was repeated. I saw there

was but one chance of quiet, so I resolved to make a virtue of

necessity, and say that if they would each immediately begin some

ordinary occupation, I would tell them a story. What child was ever

proof against a story?

"But we are to choose what it shall be about?" said one of them.

"Why?"

"Oh, never mind why. Shall we tell her, Harriet? Well, it's because

you tell cheating stories: you say, 'I'll tell you a story about a

girl, or a cottage, or a thimble, or anything you like,' and it

really is something about us."

"You may choose, then."

"Then it shall be about the lily we got for you."

"Give me ten minutes to think about it, and collect your needles and

pencils."

Upon this they brought together a heap of articles which they were

not at all likely to want, and after altering the position of their

stools and discussing what they would do, and changing their minds

many times, declared at length that they were quite ready.

"Now begin, please. There was once "So I accordingly began. "There was once a boy who was very fond of pictures. There were not

many pictures for him to look at, for his mother, who was a widow,

lived on the borders of one of the great American forests. She had

come out from England with her husband, and now that he was dead,

the few pictures hanging on her walls were almost the only luxuries

she possessed. |

"Lived on the borders of one

of the great American forests."

|

"Her son

would often spend his holidays in trying to copy them, but as he had

very little application, he often threw his half-finished drawings

away, and once he was heard to say that he wished some kind-hearted

fairy would take it in hand and finish it for him.

"'Child,' said the mother, 'for my part I don't believe there are

any such things as fairies. I never saw one, and your father never

did; but by all accounts, if fairies there be, they are a jealous

and revengeful race. Mind your books, my child, and never mind the

fairies.'

"'Very well, mother,' said the boy.

"'It makes me sad to see you stand gazing at the pictures,' said his

mother, coming up to him and laying her hand on his curly head; 'why, child, pictures can't feed a body, pictures can't clothe a

body, and a log of wood is far better to burn and warm a body.'

"'All that is quite true, mother,' said the boy.

"'Then why do you keep looking at them, child?'

"The boy hesitated, and then answered, 'I don't know, mother.'

"'You don't know! nor I neither. Why, child, you look at the dumb

things as if you loved them. Put on your cap and run out to play.'

"So the boy went out, and wandered toward the forest till he came to

the brink of a sheet of water. It was too small to be called a lake,

but it was deep, clear, and overhung with crowds of trees. It was

evening, and the sun was getting low. There was a narrow strip of

land stretching out into the water. Pine-trees grew upon it; and

here and there a plane-tree or a sumach dipped its large leaves

over, and seemed intent on watching its own clear reflection.

"The boy stood still, and thought how delightful it was to see the

sun red and glorious between the black trunks of the pine-trees. Then he looked up into the abyss of clear sky overhead, and thought

how beautiful it was to see the little frail clouds folded over one

another like a belt of rose-coloured waves. Then he drew still nearer

to the water, and saw how they were all reflected down there among

the leaves and flowers of the lilies; and he wished he were a

painter, for he said to himself, 'I am sure there are no trees in

the world with such beautiful leaves as these pines; I am sure there

are no other clouds in the world so lovely as these; I know this is

the sweetest piece of water in the world, and, if I could paint it,

every one else would know it too.' He stood still for awhile,

watching the water-lilies as they closed their leaves for the night,

and listening to the slight sound they made when they dipped their

heads under water. 'The sun has been playing tricks with these

lilies as well as with the clouds,' he said to himself, 'for when I

passed by in the morning they swayed about like floating snowballs,

and now there is not a bud of them that has not got a rosy side. I

must gather one, and see if I cannot make a drawing of it.' So he

gathered a lily, sat down with it in his hand, and tried very hard

to make a correct sketch of it in a blank leaf of his copy-book. He

was far more patient than usual, but he succeeded so little to his

own satisfaction, that at length he threw down the book, and,

looking into the cup of his lily, said to it, in a sorrowful voice,

'Ah, what use is it my trying to copy anything so beautiful as you

are? How much I wish I were a painter!'

"As he said these words he felt a slight quivering in the flower;

and, while he looked, the cluster of stamens at the bottom of the

cup floated upward, and glittered like a crown of gold; the dewdrops

which hung upon them changed into diamonds before his eyes; the

white petals flowed together; the tall pistil was a golden wand; and

the next moment a beautiful little creature stood upon his hand,

clad in a robe of the purest white, and scarcely taller than the

flower from which she sprung.

"The next moment

a beautiful little creature stood upon his hand."

"Struck with astonishment, the boy kept silence. She lifted up her

face, and opened her lips more than once. He expected her to say

some wonderful thing; but, when at length she did speak, she only

said, 'Child, are you happy?'

"'No,' said the boy, in a low voice, 'because I want to paint, and

I cannot.'

"'How do you know that you cannot?' asked the fairy.

"'Oh, fairy,' replied the boy, 'because I have tried a great many

times. It is of no use trying any longer.'

"'What if I were to help you?' said the fairy.

"'There would then indeed be some pleasure in the work and some

chance of success,' said the boy.

"'I was just closing my leaves for the night,' answered the fairy,

'when you drew me out of the water; and I should have made you feel

the effects of my resentment if it had not happened that you are the

favourite of our race. Under the water, at the bottom of this lake,

are our palaces and castles; and when, after visiting the upper

world, we wish to return to them, we close one of these lilies over

us, and sink in it to our home. The wish that I heard you utter just

now induced me to appear to you. I know a powerful charm which will

ensure your success and the accomplishment of your highest wishes;

but it is one which requires a great deal of care and patience in

the working, and I cannot put you in possession of it unless you

will promise the most implicit obedience to my directions.'

"'Spirit of a water-lily!' said the boy, 'I promise with all my

heart.'

"'Go home, then,' continued the fairy, 'and you will find lying on

the threshold a little key: take it up.'

"'I will,' answered the boy; 'and what then shall I do?'

"'Carry it to the nearest pine-tree,' said the fairy, 'strike the

trunk with it, and a keyhole will appear. Do not be afraid to unlock

that magic door. Slip in your hand, and you will bring out a

wonderful palette. I have not time now to tell you half its virtues,

but they will soon unfold themselves. You must be very careful to

paint with colours from that palette every day. On this depends the

success of the charm. You will find that it will soon give grace to

your figures and beauty to your colouring; and I promise you that,

if you do not break the spell, you shall not only in a few years be

able to produce as beautiful a copy of these flowers as can be

wished, but your name shall become known to fame, and your genius

shall be honoured, and your pictures admired on both sides the

Atlantic.'

"'Can it be possible?' said the boy; and the hand trembled on which

stood the fairy.

"'It shall be so, if only you do not break the charm,' said the

fairy; 'but lest, like the rest of your ungrateful race, you should

forget what you owe to me, and even when you grow older begin to

doubt whether you have ever seen me, the lily you gathered will

never fade till my promise is accomplished.'

"So saying, she gathered around her the folds of her robe, crossed

her arms, and dropping her head on her breast, trembled slightly;

and, before the boy could remark the change, he had nothing in his

hand but a flower.

"He looked up. All the beautiful rosy flowers were faded to a shady

gray. The gold had disappeared from the water, and the forest was

dense and gloomy. He arose with the lily in his hand, went slowly

home, laid it in a casket to protect it from injury, and then

proceeded to search for the palette, which he shortly found; and,

lest he should break the spell, he began to use it that very night.

"Who would not like to have a fairy friend? Who would not like to

work with a magic palette? Every day its virtues become more

apparent. He worked very hard, and it was astonishing how soon he

improved. His deep, heavy outlines soon became light and clear; and

his colouring began to assume a transparent delicacy. He was so

delighted with the fairy present that he even did more than was

required of him. He spent nearly all his leisure time in using it,

and often passed whole days beside the sheet of water in the forest. He painted it when the sun shone, and it was spotted all over with

the reflection of fleeting white clouds; he painted it covered with

water-lilies rocking on the ripples; by moonlight, when two or three

stars in the empty sky shone down upon it; and at sunset, when it

lay trembling like liquid gold.

"But the fairy never came to look at his work. He often called to

her when he had been more than usually successful; but she never

made him any answer, nor took the least notice of his entreaties

that he might see her again.

"So a long time several years passed away. He was grown up to be

a man, and he had never broken the charm; he still worked every day

with his magic palette.

"No one in these parts cared at all for his pictures. His mother's

friends told him he would never get his bread by painting; his

mother herself was sorry that he chose to waste his leisure so; and

the more because the pictures on her walls were brighter far than

his, and had clouds and trees of far clearer colour, not like the

common clouds and misty hills that he was so fond of painting, and

his faintly coloured distant forest, with uncertain and variable

hues, such as she could see any day when she looked out at her

window.

"It made the young man unhappy to hear all this fault found with his

proceedings, but it never made him leave off using the fairy's

palette, though about this time he himself began to doubt whether he

should ever be a painter. One evening he sat at his easel, trying in

vain to give the expression he wished to an angel's face, which

seemed to get less and less like the face in his heart with every

touch he gave it. On a sudden he threw down his brush, and with a

feeling of bitter disappointment upbraided himself for what he now

thought his folly in listening to the fairy, and accepting her

delusive gift. What had he got by it hitherto? Nothing but his

mother's regrets and the ridicule of his companions. He threw

himself on his bed. It grew dark; he could no longer be vexed with

the sight of his unfinished angel; and angel he fell asleep and

forgot his sorrow.

"In the middle of the night he suddenly awoke. His chamber was full

of moonlight. The lid of the casket where he kept the lily had

sprung open, and his fairy friend stood near it.

"'American painter,' she said, in a reproachful voice, 'since you

think I have been rather a foe than a friend to you, I am ready to

take back my gift.'

"But sleep had now cooled the young painter's mind, and softened his

feelings of vexation, so that he did not find himself at all willing

to part with the palette. While he hesitated how to excuse himself,

she further said, 'But if you still wish to try what it can do for

you, take this ring which my sister sends you; wear it, and it will

greatly assist the charm.'

"The youth held out his hand and took the ring. As he cast his eyes

upon it, the fairy vanished. He turned it to the moonlight, and saw

that it was set with a stone of a transparent blue colour. It had

the property of reflecting everything bright that came near it; and

there was a word engravers upon it. He thought he could not be

sure but he thought the word was 'Hope.'

"After this, and during a long time, I can tell you no more about

him: whether he finished the angel's face, and whether it pleased

him at last, I do not know. I only know that, in process of time,