|

INTRODUCTION

(from 'Mopsa the Fairy,'

in the Everyman's Library series)

JEAN INGELOW

may be said to have begun her study of the art of writing child-rhymes and

the tales that are akin to them under Jane and Ann Taylor. A

friendship had sprung up between the families at Walton-on-the-Naze in

Essex, where the Ingelow youngsters used to stay; and "Greedy Dick" and

"Mrs. Duck, the notorious glutton," were among their favourite characters.

In her first book, however, Jean Ingelow showed that she had a note and a

child-fantasy of her own. They are seen in her fairy-ballad of Mimie

and of the forest where the child-fairy lived:

|

"When the clouded sun goes in--

Waiting for the thunder,

We can hear their revel din

The moss'd greensward under.

"And I tell you, all the birds

On the branches singing

Utter to us human words

Like a silver ringing."

|

Her earliest impressions are reflected in some lines found in

Mopsa, which tell of a ship coming up the river with a jolly gang

of towing men. She was born at Boston, Lincolnshire, on the 17th of

March 1820; the daughter of a banker who had married a Scottish wife, Jean

Kilgour. Her grandfather owned some of the ships that came up the

Boston water; and the scenery of that fen country entered into her inner

mind. Her fine ballad, "High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire," was

one outcome of those early days. In middle life she came to live in

London, and she wrote of the city and its shifting and unending throng;

but her best pages are those, whether verse or prose, that reflect the

things of the seashore and waterside, the "empty sky," the "world of

heather," which she knew as a child in Lincolnshire and Essex.

Ipswich, Filey Brig in Yorkshire, and other places are to be counted in

her own history; and some of the memories that are a picture of her early

days may be found in her long story Off the Skelligs, where she

sketches her birthplace, and the house by the wharves, with a room in the

rooftree overlooking the ships and a long reach of the river.

Jean Ingelow died in Kensington in 1897; and a memorial brass

is to be seen bearing her name in the church of St. Barnabas there.

|

|

――――♦――――

The Queen of Victorian Verse.

Ray Carradine salutes the work

of a great Lincolnshire poet.

[This article first appeared in Lincolnshire Life,

September 1995, and

is reproduced by kind permission of the Editor.]

|

|

|

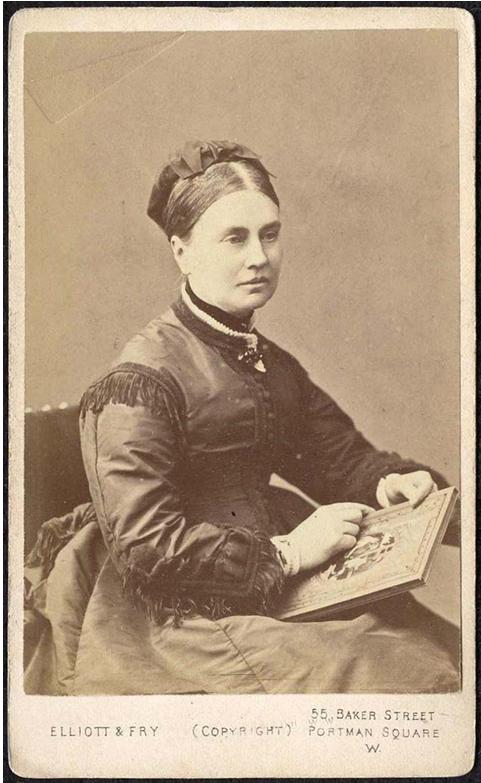

JEAN INGELOW

(1820-97) |

FEW PEOPLE nowadays are

familiar with the poems and stories of Jean Ingelow; it was a

different matter during her lifetime, however, when she enjoyed great

popularity both here and in America. Her work was much admired by

another Lincolnshire wordsmith, Alfred Lord Tennyson, whom she met by

chance in the street after the publication of her volume 'Poems'.

"Miss Ingelow," the Poet Laureate announced, shaking her warmly by the

hand, "I declare you do the trick better than I do."

Jean was born in Boston on 17th March 1820, the eldest child

of William and Jean Ingelow. William, a banker, and his wife were a

devoted couple, well respected members of the community who lived in South

Place, overlooking the river. A short distance away, in the same

square, lived William's parents, and when a fire destroyed their home the

Ingelows moved in with Jean's grandfather.

From the nursery of her grandfather's large Georgian house

the young Jean viewed the river activity, watching vessels loaded with

cargoes of grain, listening to the songs of the men at work and watching

the sunlight glinting on the water. It was a scene that she loved

and one which remained with her always.

In 1825 financial difficulties beset the Ingelows. The

bank failed, William was declared bankrupt, the family home was sold and

alternative accommodation sought. Despite the reduced circumstances,

however, the atmosphere at home remained happy; the family continued to

grow and by 1831 the Ingelows had seven children.

Mrs Ingelow, a woman of Scottish descent, was a staunch

member of the evangelical movement and held strong beliefs: although she

loved music dancing was forbidden, as was the playing of card games.

Family prayers were held morning and night, and those who were late

attending had to pay a small fine, placed in a missionary box for the

conversion of less enlightened souls.

Jean, a shy, sensitive and thoughtful child, helped to look

after her younger brothers and sisters, though their education lay in the

hands of Aunt Rebecca, a strong-willed woman who lived at nearby Skirbeck.

Aunt Rebecca's marked antipathy towards marriage probably influenced young

Jean, for there was a strong bond of affection between the two and Jean

never married.

In 1834 William Ingelow was appointed manager of a bank in

Ipswich, and the family moved to Suffolk. Jean was upset at the

thought of leaving her beloved Lincolnshire, but the blow was cushioned

when she learnt that Aunt Rebecca would be going with them. Now Mrs

Ingelow took over her children's education, placing religious instruction

and morally uplifting poetry high on the syllabus.

The Ingelows' house in Ipswich was a large one and Jean had

the luxury of her own room. It was at this time that she first began

to write, although her mother gave her little encouragement. Mrs

Ingelow considered that her daughter could better serve the large family

by sewing, reading or doing household chores. Undeterred, the

intrepid Jean solved the problem by scribbling her verse on the back of

her bedroom shutters; her first poem described Catherine of Aragon's grief

over her divorce from Henry VIII.

Writing was clearly a family trait: the younger Ingelow

children produced their own newspaper, called St Stephen's Herald, typeset

by a friend and sold for one penny, to which Jean occasionally contributed

poems under the pen-name of Orris. When her mother discovered that

the verses were intended to entertain the younger children she viewed them

in a somewhat different light.

|

|

|

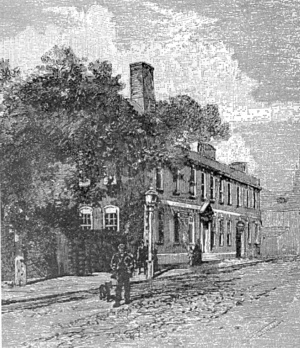

Jean Ingelow's home in South Square, Boston |

When Jean was about eighteen she met the one true love of her life, a

sailor who came to stay at the family home. Little is known of him,

for Jean had been brought up to be discreet and reticent about affairs of

the heart. She never spoke of her feelings for the young man,

although it seems clear that there was some kind of understanding between

them. It is probable that he set sail and that his ship was lost at

sea, for many of her poems describe unhappy love affairs in which the

lover dies or fails to return home.

More unhappiness was on the horizon. In 1845 the bank

in Ipswich closed and the Ingelows were forced to move once more.

Though Jean was optimistic that the publication of her poems might ease

the family's growing financial burdens, she received scant encouragement

from her parents, who considered that her writing was nothing more than a

harmless pastime. An old family friend, the Reverend Edward Harston,

then curate of Tamworth, was more supportive, however: he edited Jean's

first published volume, 'A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and Feelings',

which appeared in 1850. Included were verses dedicated to the memory

of three of Harston's children who had died in rapid succession.

The Ingelows moved to London and Jean followed up her volume

of poems with a novel, 'Allerton and Dreux', but neither this nor the

poetry was to set the literary world on fire. From 1852 she

contributed regularly to the evangelical 'Youth Magazine' under her

pseudonym, and in 1860 a compilation of these stories, 'Tales of Orris',

appeared and met with more success. The heavily moral children's

tales found favour with strict Victorian parents, but it was 'Poems',

published in 1863 under her own name, which established her as a major

literary figure. She found herself on friendly terms with notables

such as Robert Browning, Christina Rossetti and Tennyson himself.

Despite her shyness Jean showed an admirable head for

business when contacting American publishers, and she enjoyed great

success in the United States. She received royalties from many

editions of her works, although international copyright did not arrive

until 1891 and many pirate copies were in circulation which yielded her

nothing. Other collections followed, one of which included the

ambitious poem 'A Story of Doom'; relating the bible story of Noah and the

Ark, it was too diffuse to be universally popular.

Her best-known poem, 'High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire,

1571' cleverly used poetic licence to merge together two flood disasters

from her native county. The sixteenth-century calamity inspired the

theme and tempo but the story originated from the flooding at Fosdyke in

1810, when a Mr Birkett's servant girl lost her life while milking the

cows. 'Divided', another much acclaimed poem, tells of a couple

walking on opposite sides of a stream; as it widens they drift further

apart until they become separated forever.

In the spring of 1855 Jean moved with her parents and her

unmarried sisters and brothers to 15 Holland Street, Kensington, where she

lived for over twenty years until her mother's death. To achieve the

solitude required for writing she rented a nearby apartment, and novels

followed: the well loved children's tale 'Mopsa the Fairy', 'Off the

Skelligs' and 'Sarah de Berenger', as well as more poems.

Success matured her and in middle-age she lost much of the

coyness and uncertainty that had marred her youth. Her name was

romantically linked with a number of gentlemen, including Robert Browning

after the death of his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, but Jean never

married. When her mother died in the late 1870s the house at

Kensington (later the site of a block of flats known as Ingelow House) was

put on the market; Jean went to live with her bachelor brothers, for

maiden ladies seldom lived alone in Victorian times.

In 1892, when Jean's great friend and mentor Alfred Lord

Tennyson died, her name was put forward as a possible successor for the

position of Poet Laureate. A petition to that effect, signed by many

of the leading writers of the day, arrived from America; Queen Victoria

gave the matter due consideration but chose Alfred Austin instead.

Britain was becoming more enlightened in the Naughty Nineties but the idea

of a female Poet Laureate was too great an innovation.

Whether Jean would have accepted the post had it been offered

is open to debate; by now she was in her seventies and her popularity was

beginning to wane. Perhaps the fact that her fellow writers held her

in such high esteem was gratification enough. Times and tastes were

changing, and Jean's strict religious upbringing and high moral values,

reflected in her stories and verses, were losing their appeal.

Jean Ingelow was essentially a product of Victorian times and

her verses were admirably suited to that period. She died on 20th

July 1897, aged seventy-seven, and was buried at Brompton Cemetery.

At St Botolph's Church, in her home town of Boston; a handsome stained

glass window honours the memory of a much loved Victorian poet.

|

|

――――♦――――

JEAN INGELOW.

FROM

WOMEN AUTHORS OF THE DAY.

BY

HELEN C. BLACK

LONDON: MACLAREN

AND COMPANY,

1906.

"TALENT does what it

may; Genius, what it must." To no one could the definition apply

more appropriately than to the well-known and gifted poetess, Jean

Ingelow. She came into the world full-blown; she was a poet in

mind from infancy; she was born just as she is now, without improvement,

without deterioration. From her babyhood, when she could but just

lisp her childish hymns, she was always distressed if the rhyme were not

perfect, and as she was too young to substitute another word with the

same meaning, she used simply to make a word which was an echo of the

first, quite oblivious of the meaning. Every trifling incident, a

ray of sunlight, a flower, a singing bird, a lovely view all inspired

her with a theme for expression, and she had a joy in so expressing

herself.

Jean Ingelow was born near Boston, Lincolnshire. She

was one of a large family of brothers and sisters; she was never sent to

school, and was brought up entirely at home, partly by teachers of whom

she regrets to say she was too much inclined to make game, but more by

her mother, who, being a very clever woman of a poetical turn of mind,

mainly educated her numerous family herself. Her father was a

banker at Suffolk, a man of great culture and ability. "It was a

happy, bright, joyous childhood," says Miss Ingelow; "there was an

originality about us, some of my brothers and sisters were remarkably

clever, but all were droll, full of mirth, and could caricature well.

We each had a most keen sense of the ridiculous. Two of the boys

used to go to a clergyman near for instruction, where there was a small

printing machine. We got up a little periodical of our own and

used all to write in it, my brothers' schoolfellows setting up the type.

It was but the other day one of these old schoolfellows dined with us,

and reminded me that he had put my first poems into type."

Many of these verses are still in existence, but the

girl-poet had yet another place, and an entirely original one, where in

secret she gave expression to her muse. In a large upper room

where she slept, the windows were furnished with old-fashioned folding

shutters, the backs of which were neatly "flatted," and formed an

excellent substitute for slate or paper. "They were so

convenient," she remarks, smiling. "I used to amuse myself much in

this way. I opened the shutters and wrote verses and songs on

them, and then folded them in. No one ever saw them until one day

when my mother came in and found them, to her great surprise."

Many of these songs, too, were transmitted to paper and were preserved.

Whilst on a visit to some friends in Essex, Jean Ingelow and

some young companions wrote a number of short stories and sent them for

fun to a periodical called The Youth's Magazine. She signed

her contributions "Orris," and was delighted when she received an

intimation that they were accepted and that the editor "would be glad to

get more of them." Meantime, she went on accumulating a goodly

store of poems, songs, and verses; many were burnt and others directly

they were written were carefully hidden away in old manuscript books,

but the day was fast approaching when they were to see the light.

In the affectionate give and take of a witty, united, and cultured

family, her brothers and sisters used to laugh merrily at her efforts

and often parodied good-naturedly her poems, though secretly they were

proud of them. The method of bringing out this book, which was her

first great success and was destined shortly to become so famous, was

very curious. A brother wishing to give her pleasure offered to

contribute to have her MSS. printed. This was done, and the

next move was to take them to a publisher, Mr. Longman. "My mother

and I went together," says Miss Ingelow; "she consented to allow my name

to appear; we were all rather flustered and excited over it, it seemed

altogether so ridiculous." Very far from "ridiculous," however,

was the result. Mr. Longman at first looked doubtful, but soon

recognising the merits of the work, took up the matter warmly, with the

excellent effect that in the first year four editions of a thousand

copies each were sold and the young poet's fame was secured. The

book bore the simple and unpretending title, "Poems,

by Jean Ingelow." [Ed.―see Gerald Massey's

review

for the Athenæum.]

"It was a long time before I could make up my mind if I liked

it or not," says the author. "I could not help writing, it is

true, but it seemed to make me unlike other people; being one of so many

and being supposed to be sensible, and to behave on the whole like other

people, and trying to do so, and delighting in the companionship of my

own family more than in any other, I am not at all sure that I was

pleased when I was suddenly called a poet, because that is a

circumstance more than most others which sets one apart, but they were

all so joyous and made much fun over it."

This first volume of poems has been re-published and yet

again and again, until up to the present time it has reached its

twenty-sixth edition, in different forms and sizes. One of these

was brought out as an édition de

luxe, and is profusely illustrated. Jean Ingelow's poetry is

too well known and widely read to need much comment. In this

remarkable volume, probably the most quoted and best recollected verses

are to be found under the title of "Divided," "Song of Seven," "Supper

at the Mill," "Looking over a Gate at a Mill," "The Wedding Song,"

"Honours," "The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire," "Brothers and a

Sermon," "Requiescat in Pace," "The Star's Monument," yet when this is

said, you turn to another and yet another, and would fain name the last

read the best. Where all are sweet, sound, and healthy; where all are

full of feeling, bright with suggestions, and thoroughly understandable,

how hard it is to choose! And who has not read and heard over and

over again that exquisite song which

has been set to music no less than thirteen times, "When sparrows

build"? Also, "Sailing Beyond Seas," with the beauteous refrain:

|

O fair dove! O fond dove!

And dove with the white breast,

Let me alone, the dream is my own,

And my heart is full of rest.

|

To the most superficial reader the tender and real humanity

of these entirely original poems is evident, while to the student who

goes further into the fascinating work, deeper treasures are discovered;

you realise more and more her own personality, her own distinctive

style, and get many a glimpse of the pure heart and lofty aspiration of

the gifted singer.

But to return to the original issue of this first published

book. In consequence of its success, Mr. Strahan made an immediate

application for any other work by the same pen; accordingly Jean

Ingelow's early short tales, signed "Orris," were collected and

published under the title of "Stories told to a Child." This, too,

went through many editions, one of which was illustrated by Millais and

other eminent artists. A further request for longer stories

resulted in the production of a volume called, "Studies for Stories."

[Ed.― see Isabella Fyvie Mayo's

account.]

These delightful sketches, professedly written for young

girls, soon attracted children of much older growth. While simple

in construction and devoid of plot, they are full of wit and humour, of

gentle satire and fidelity to nature. They are prose poems,

written in faultless style and are truthful word-paintings of real

everyday life.

Jean Ingelow has ever been a voluminous writer, but only an

odd volume or so of her own works is to be found in her house. She

"gives them away, indeed, scarcely knows what becomes of them," she

says. Among many other of her books is one called "A

Story of Doom, and other Poems," which has likewise passed into many

editions. Here stand out pre-eminently "The Dreams that come

true," "Songs on the Voices of Birds," "Songs of the Night Watches,"

"Gladys and her Island," ("An Imperfect Fable with a Doubtful Moral,") "Lawrance,"

and "Contrasted Songs." "A Story of Doom" may be called an epic.

It deals with the closing days of the antediluvian world, while its

chief figures are Noah, Japhet, Amarant the slave, the impious giants,

and the arch-fiend. Her portraiture of these persons, natural and

supernatural, is very powerful and impressive. "Lawrance" is

unquestionably an idyll worthy to be ranked with "Enoch Arden."

Told, at once, with much dramatic power and touching simplicity, there

is a fresh, pure atmosphere about it which makes it intensely natural

and sympathetic. One of the poems in a third volume, republished

four or five years ago, is called "Echo and the Ferry," which is a great

favourite and is constantly chosen for recitation. In the "Song

for the Night of Christ's Resurrection," breathes the deeply devotional

and sincerely religious spirit of the author who was brought up by

strictly evangelical parents, yet is there no trace of narrowness or

bigotry in Jean Ingelow or her writings. She is large-hearted,

single-minded, and tolerant in all matters.

"It may seem strange to say so," observes your gentle

hostess, whilst a smile illuminates the speaking countenance; "but I

have never been inside a theatre in my life. I always say on such

occasions, that although our parents never took us, and I never go

myself out of habit and affectionate respect for their memory, I do not

wish to give an opinion or to say that others are wrong to go. We

must each act according to our own convictions, and must ever use all

tolerance towards those who differ from us. We had many pleasures

and advantages. There was no dulness or gloom about our home, and

everything seemed to give occasion for mirth. We had many trips

abroad too, indeed, we spent most winters on the Continent. I made

an excursion with a brother who was an ecclesiastical architect, and in

this way I visited every cathedral in France. Heidelberg is very

picturesque, and suggested many poetical ideas, but all travelling

enlarges one's mind and is an education."

One event which caused the keenest amusement to these happy

young people, all blessed with excellent spirits, sparkling wit, and

general enjoyment of everything, occurred when a pretty, kindly,

appreciative notice appeared in some paper of a person called by her

name. There was hardly a single item in it that was really true,

even to the description of her birthplace, which was described vaguely

as being stationed on the sea-beach and flanked by two lighthouses,

"between which the lonely child might have been seen to wander for hours

together nursing her poetic dreams, dragging the long trails of seaweed

after her, and listening to the voice of the waves." This

supposititious little biography was productive of the greatest merriment

to her brothers and sisters. The first impulse was to answer it,

to disclaim the solitary wanderings and poetic dreams, and to describe

the place correctly; but although urged by friends to do this, Jean

Ingelow on reflection decided to let it pass, and in the end the

laughter died out. "To a poetic nature," she remarks, "expression

is a necessity, but once expressed, the thought and feeling that

inspired it may often be forgotten. I am sure that I could not

repeat one of my own poems from beginning to end just as I wrote it.

I have a distinct theory too, that one is not taught, one is born to it.

I was never able to make a great effort in my life, but what I can do at

all, I can do at once, and having thought a good deal on any subject I

know very little more than I did at first. Things come to me

without striving, besides I am quite unromantic. I never wrote in

a hurry. We might all be laughing and talking together, yet if I

went up to my room and sat alone, I could at once write in a most sad

and melancholy strain. I was not studious as a child, though I

remember a great epoch in my life was reading 'The Pilgrim's Progress,'

when I was seven years old, and I was perfectly well able to perceive

the deep imaginative powers of it, but I always wanted to study what was

not in books."

But if Jean Ingelow's books are sold by thousands in England,

they are sold by tens of thousands in America. Her publishers

there for many years used to send her a handsome royalty on their sales;

some years ago, however, five other American publishers brought out her

poetical works simultaneously, since which time she has received

nothing! She is probably the first woman-poet who has met with not

only world-wide popularity, but who might if it had been needful, have

lived very well by the proceeds of her verse alone. A few years

ago Messrs. Longman brought out, by request, a new edition of her books.

Altogether, she declares herself to "have been a very fortunate woman,

and almost always happy in her publishers, too."

In later years Jean Ingelow has written many prose works of

fiction, notably "Off the Skelligs," "Fated

to be Free," "Don John," "Sarah

de Berenger," "Mopsa, the Fairy,"

"John Jerome," etc. "Off the

Skelligs" was the first novel by the author whose name had hitherto been

almost exclusively associated with verse, and it was received with more

than ordinary interest. The book teems with incident; the poetic

vein may be traced in the realistic pictures of child life, in the

description of the lovely scenery depicted in the yachting trip, and in

the graphic and stirring account of the burning ship and rescue of its

passengers. "Fated to be Free" is a sequel to the previous work.

The book opens with a powerful description of an old manor house and

family over whose head hangs the mysterious blight of some unknown

misfortune, which is cleverly indicated rather than described, and

though tragical in the main, the sorrow is not allowed to overshadow the

story too heavily, for here and there humour and wit sparkle out, while

the whole betrays the writer's deep intuitive knowledge of human hearts

and human lives. "Mopsa, the Fairy" has been called "A poem in

prose, for the use of children," and a better name for it could not be

found. It is, as the title implies, a tale of fairyland in its

brightest aspect, and is told with the purity of conception and the

excellence of execution which characterise the gifted author's writings.

A few words must be said in description of the pretty house

in Kensington where Miss Ingelow lives with her brother, and into which,

some thirteen years ago, they removed from Upper Kensington to be

further out and away from so much building. Since this removal she

says, "three cities have sprung up around them!" The handsome

square detached house stands back in a fine, broad road, with carriage

drive and garden in front filled with shrubs, and half a dozen chestnut

and almond trees, which in this bright spring weather are bursting out

into leaf and flower. Broad stone steps lead up to the hall door,

which is in the middle of the house. The entrance hall where hangs

a portrait of the author's maternal great-grandfather, the Primus of

Scotland, i.e., Bishop of Aberdeen opens into a spacious, old-fashioned

drawing-room of Italian style on the right. Large and lofty is this

bright, cheerful room. A harp, on which Miss Ingelow and her

mother before her played right well, stands in one corner. There

is a grand pianoforte opposite, for she was a good musician, and had a

remarkably fine voice in earlier years. On the round table in the

deep bay windows in front are many books, various specimens of Tangiers

pottery, and some tall plants of arum lilies in flower. The great

glass doors draped with curtains at the further end, open into a large

conservatory where Miss Ingelow often sits in summer. It is laid

down with matting and rugs, and standing here and there are flowering

plants and two fine araucarias. The verandah steps on the left

lead into a large and well-kept garden with bright green lawn, at the

end of which through the trees may be discerned a large stretch of

green-houses, and a view beyond of the great trees in the grounds of

Holland Park. On the corresponding side of the house at the back

is the billiard-room, which is Mr. Ingelow's study, leading into an

ante-room, and in the front is the dining-room, where the author's

literary labours are carried on. "I write in a common-place,

prosaic manner," she says; "I am afraid I am rather idle, for I only

work during two or three of the morning hours, with my papers spread all

about the table." Over the fireplace hangs a painting on ivory of

her father, and above it a portrait of her mother, taken in her early

married life. This portrait, together with one of the poet herself

when an infant, is in pastels, and they were originally done as door

panels for her father's room; the colouring is yet unfaded.

The conversation turning upon memory for Jean Ingelow holds

pronounced theories on this subject she leads the way back to the

conservatory and points out the picture of her grandfather's house,

called Ingelow House after her, with which her very earliest

recollections are associated, and her memory dates back to when she was

but seventeen months old! She says that "friends smile at

this and think that she is romancing, but if people made attempts to

recollect their very early days, certain visions which have passed into

the background for many years would rise again with a distinctness which

would make it impossible to mistake them for inventions, and also make

it certain that the records of this life are not annihilated, but only

covered." She took some trouble to collect facts as to "first

recollections" of many people, and found that two at least could

remember events which were proved to have happened at the age of

eighteen and twenty-two months respectively. In further support of

this theory she relates an amusing and curious incident of dormant

memory in early childhood which actually happened in her own family.

Miss Ingelow's mother went on a visit to her own father, who lived in

London, accompanied by her infant son aged eleven months and his nurse.

One day the nurse brought the baby into his mother's room and put him on

the floor, which was carpeted all over, where he crept about and amused

himself whilst she dressed her mistress. When the toilet was

completed, a certain ring which Mrs. Ingelow generally wore was missing.

Search was made but it was never found and shortly after the visit

ended, and the matter was almost forgotten. Mother and child again

went on the same visit exactly a year later, accompanied by the same

nurse, who took the boy into the same room. His mother saw him

look around him, and deliberately walk up to one corner, turn back a bit

of the carpet and produce the ring. He never gave any account of

it nor did he seem to remember it later; he had probably found it on the

floor and hidden it for safety it could hardly have been for mischief

and had forgotten all about it until he saw the place again, as he was

too young when the ring was missed to understand what the talk and

search about it meant. "He was by no means a precocious child,"

adds Miss Ingelow, "nor did he show later any remarkable qualities in

his powers of learning or remembering lessons."

She lost her mother thirteen years ago, and her father passed

away before the publication of her first book of poetry, the book of

which he would have been so proud. "It was a joy to me," says the

poetess, "when I found that people began to read my verses, and I can

never forget too my pleasure when first introduced to Mr. Ruskin and he

asked my mother and me to luncheon at his house. Of course, I was

far too modest to be willing to talk to him, especially in my mother's

presence; but after luncheon I got away from them, leaving them in high

discourse, and surreptitiously stole down to look at a bush of roses

which were very much to my mind. Mr. Ruskin presently came up to

me, and entered into a charming conversation. He gathered some of

the flowers and gave them to me ― I

kept them for a long time ― then we

walked round a meadow close at hand which was just fit for the scythe,

and afterwards he took me to see a number of the curiosities that he had

collected. We soon became loving friends and his friendship has

been one of the great pleasures of my life. Sir Arthur Helps, too,

was for many years a dear friend."

Miss Ingelow is, as may be supposed, a great reader, though

she observes, "that few people take as long a time in reading a book as

she does." Her preference is for works of a religious tone,

chiefly those of eminent divines. "I do not want to use the word

'fastidious,'" she adds, "but perhaps I am more bornée

than most people in my taste in literature. Even some of Sir

Walter Scott's and many of Thackeray's novels I cannot read, but I am

fond of 'Vanity Fair,' and Dickens, and delight in several of

Shakespeare's masterpieces, reading them over and over again."

She is "resting" for a while now. The poetic vein, she

says, is not strongly upon her for the moment, but it invariably

returns. Meantime it is to be hoped that the day may not be far

distant when the public will rejoice to welcome yet more sweet strains

from the pen of the great and gifted poet.

|

|

――――♦――――

APPRECIATIONS OF POETRY

BY

LAFCADIO HEARN

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1916.

This volume contains a second selection from the lectures which

Lafcadio Hearn delivered at the University of Tokyo between 1896 and

1902.

CHAPTER IX.

A NOTE ON JEAN INGELOW

As the term is drawing to a close, so that we shall have only two or

three more days together, I have thought it better, having completed the

last lecture, not to begin a new lecture upon the same scale, but to

give a short lecture about some single famous poem. And I have

chosen for this purpose Jean Ingelow's famous poem, "The High Tide on

the Coast of Lincolnshire." Sometimes a poet becomes celebrated by

the writing of one poem only. This happens to be the case with

Miss Ingelow. She wrote several volumes of poems which were very

popular in England and even in America. But popularity, during the

lifetime of a writer, is no proof of literary merit; and it was not so

in Miss Ingelow's case. She really wrote only one great poem; and

by that one poem her name will always be preserved in the history of

English literature.

The subject of this poem ought to interest you. The

subject is only too familiar in Japan — a tidal wave (tsunami).

There are few more terrible things possible for man to endure, in the

form of what are called "natural visitations," than earthquakes and

tidal waves. These two dreadful forms of calamity have been more

common in this country than in Europe; but Europe has not been entirely

exempt from them. There is only one other kind of natural calamity

which can be at all compared with them — a volcanic eruption. But

it is seldom indeed that a volcanic eruption, in any civilised country,

produces such destruction of life as may be caused by an earthquake or a

tidal wave.

It is about three hundred years since England had a great

cataclysm of this sort; and it has never been forgotten by the people of

the coast where it happened. That coast happens to be quite low.

At one time, indeed, it was little better than a great salt-marsh.

But several miles inland there was very good farm-land, and plenty of

farms and towns and villages. Miss Ingelow herself lived

very near the scene of her poem. You must imagine a river

flowing through the low country, widening very much toward the mouth —

the river Lindis; Boston town stands near the bank. When the tidal

wave came, the immediate effect was to force the river back, so that

even distant parts of the country which the sea could not reach were

flooded by the river. There is only one more thing to tell you

about the poem — that it is written in English of the sixteenth century,

yet there are only two or three queer words in it; everything is easy to

understand. The verses are of different form and the stanzas of

irregular length.

|

The old mayor climbed the belfry-tower,

The ringers ran by two, by three;

"Pull, if ye never pulled before;

Good ringers, pull your best," quoth he.

"Play uppe, play uppe, O Boston bells!

Ply all your changes, all your swells.

Play uppe 'The Brides of Enderby.'"

|

The church tower of St, Botolph's, which still stands, is the

belfry-tower here referred to. That was long before the time of

telegraphs and railroads, and the only way of quickly sending news of

danger through the country used to be to ring the great bells of the

churches. It was therefore very important to have good bells; and

every great church had a number of them, all of different sizes, so

arranged that different tunes could be played upon them. You can

still hear this kind of ringing in many parts of Europe. The tunes

are usually very simple tunes known to all the people, and commonly hymn

tunes, but not always. In time of danger it was agreed that

particular tunes should be played. In the district of

Lincolnshire, the tune that meant danger was the tune of an old ballad,

called "The Brides of Enderby," and when people heard the church bells

play it they knew that something terrible was going to happen. I

believe you know it requires a number of men to ring the bells in this

way; and it used to be a regular calling. The word "changes" in

the sixth line means variation in the modern musical sense; the word

"swells" refers to a particular way of ringing two or more bells

together, so that the sounds of all would blend into one great wave of

tone.

You must understand that the whole story is being told by an

old grandmother; she relates everything as she saw it and felt it, in a

simple and touching way.

|

Men say it was a stolen tyde —

The Lord that sent it, He knows all;

But in myne ears doth still abide

The message that the bells let fall:

And there was naught of strange, beside

The flights of mews and peewits pied

By millions crouched on the old sea wall.

I sat and spun within the doore,

My thread brake off, I raised myne eyes;

The level sun, like ruddy ore,

Lay sinking in the barren skies;

And dark against day's golden death

She moved where Lindis wandereth,

My Sonne's faire wife, Elizabeth.

"Cusha! Cusha! Cusha!" calling,

Ere the early dews were falling,

Farre away I heard her song.

"Cusha! Cusha!" all along;

Where the reedy Lindis floweth,

Floweth, floweth.

From the meads where melick groweth

Faintly came her milking song —

"Cusha! Cusha! Cusha!" calling,

"For the dews will soone be falling;

Leave your meadow grasses mellow,

Mellow, mellow.

Quit your cow-slips, cow-slips yellow;

Come uppe Whitefoot, come uppe Lightfoot;

Quit the stalks of parsely hollow.

Hollow, hollow,

Come uppe Jetty, rise and follow.

From the clovers lift your head;

Come uppe Whitefoot, come uppe Lightfoot

Come uppe Jetty, rise and follow,

Jetty, to the milking shed."

|

The expression "stolen tide" in the first stanza is strange

to you, I think; it is strange even to English readers who are not aware

that country-folk often use the word "stolen" in the sense of contrary

to nature, monstrous, magical. Now you have the old grandmother

talking to you, recalling her memories. She tells you that upon

the evening of the great tidal wave, the first thing that startled her

was the sound of the church bells signalling danger. It startled

her so that she broke the thread which she was spinning at the door;

then she looked up to see if there was anything unusual in sky or field.

Nothing in the sky; it was what she called "a barren sky" — that is, a

sky without a single cloud; and the sun was sinking beautifully, making

all the West full of gold light. Nothing in the field — no, but

what was that upon the sea-wall? Of course you know what a

sea-wall is; they are very common in Japan, built to protect fishing

villages or low coasts against the surf of heavy storms. Yes;

there was something strange on the sea-wall; millions of sea-birds were

crowded there — white gulls, and parti-coloured gulls, called peewits

from their melancholy cry. The danger was probably from the sea —

but what was it? While wondering what it could be, the old woman

heard her son's wife singing to the cows. I am not sure whether

you know about this custom. Milk-cows, in England, are left all

day to graze in the meadows, when the weather is fine; and at evening

they are called home, milked, and put in their stables. The men or

boys who take care of them, or the girls — dairymaids as they are termed

— often sing a kind of song to call the animals home; they come at once

when they hear the song. Names are given to them, usually names

indicating the appearance of the cow, or something peculiar about it.

In this song, the name Whitefoot probably means a red or a black cow

with pure white feet. The name Lightfoot might mean a thoroughbred

cow — that is, a cow of very fine race — with a particularly light quick

walk. The name Jetty probably refers to a perfectly black cow,

black as jet. There is nothing else to explain, except the queer

old word "melick," the name of a particular kind of grass.

"Cow-slips" are, you know, long yellow flowers, very common in European

fields.

|

If it be long, ay, long ago

When I beginne to think howe long,

Againe I hear the Lindis flow,

Swift as an arrowe, sharpe and strong;

And all the aire, it seemeth me,

Bin full of floating bells (sayth shee),

That ring the tune of Enderby.

Alle fresh the level pasture lay,

And not a shadowe mote be seene,

Save where full fyve good miles away

The steeple towered from out the greene.

And lo! the great bell farre and wide

Was heard in all the country side

That Saturday at eventide.

The swanherds where their sedges are

Moved on in sunset's golden breath,

The shepherde lads I heard afarre,

And my Sonne's wife, Elizabeth;

Till floating o'er the grassy sea

Came downe that kyndly message free.

The "Brides of Mavis Enderby."

Then some looked uppe into the sky,

And all along where Lindis flows

To where the goodly vessels lie,

And where the lordly steeple shows.

They sayde, "And why should this thing be?

What danger lowers by land or sea?

They ring the tune of Enderby!

"For evil news from Mablethorpe,

Of pyrate galleys warping downe;

For shippes ashore beyond the scorpe,

They have not spared to wake the towne:

But while the west bin red to see,

And storms be none, and pyrates flee,

Why ring 'The Brides of Enderby'?"

|

The conditional mood at the beginning of the first of the

stanzas just quoted, is only suggested; there is no sequence, no main

clause. You must understand the meaning to be something like this:

"You ask me if it was long ago. If it was long ago! Ah,

perhaps, it was long ago — yet when I try to think how long ago it was,

I see and hear everything so plainly that it seems to me even now."

In the fourth line, the adjectives "sharp and strong" refer, of course,

to the arrow — a heavy war-arrow would fly much faster and with a louder

sound than the sporting arrow. Archery was still kept up in the

sixteenth century. But the old woman is not thinking only of the

arrow; she is thinking of the sound made by the strong current of the

river. It had a sharp sound, she tells us, like the sound of a

heavy arrow. Notice in the sixth line the use of "bin" for "is."

In the following stanza, you need only observe the curious old perfect

"mote" used where we would now say "might" or "could." In the

third line, you will find the term "good miles." Why should people

speak of a good mile or a good distance? In such places the word

"good" has the sense of "at least," "fully," "not less than."

The description goes on very vividly; after speaking of the

beautiful clear weather, with nothing in all the level of the flat

country to break the skyline, except the far-away shape of the church

steeple, the old woman speaks of the swans in the high river grass, the

shouting of the shepherd boys, calling home their sheep, and the sweet

song of the young wife waiting to milk the cows as they return from

pasture. There was nothing at all of danger visible; and the

peasants wondered why the bells sounded danger. Observe in the

fourth of this group of stanzas the use of the word "lowers" in the

sixth line. To-day we more commonly spell it "lour" — though

originally the meaning was very much the same. When clouds hang

down very low, it is a sign of storm; when brows are lowered in a frown

it is a sign of anger. So when we speak of a lowering sky we mean

a threatening sky; but however we spell the word, we pronounce it with a

very full sound of "ow" in the sense of "to threaten." "What

danger is threatening us from the land or from the sea'?" That is

what the people ask each other. Why do they ring the bells in that

way? If pirates had attacked the neighbouring port of Mablethorpe,

or if there were any ships wrecked beyond the rock-line (scorpe), then

there would be some reason for calling up all the people. The

expression "wake" the town, does not mean to awaken, but to summon, to

call. This is a quaint idiom.

Very suddenly, though, the old grandmother learns what the

danger is:

|

I looked without, and lo! my sonne

Came riding downe with might and main!

He raised a shout as he drew on,

Till all the welkin rang again,

"Elizabeth! Elizabeth!"

(A sweeter woman ne'er drew breath

Than my Sonne's wife, Elizabeth.)

"The olde sea-wall (he cried) is downe,

The rising tide comes on apace,

And boats adrift in yonder towne

Go sailing uppe the market-place."

He shook as one that looks on death:

"God save you, mother!" straight he saith;

"Where is my wife, Elizabeth?"

"Good Sonne, where Lindis winds away.

With her two bairns I marked her long;

And ere yon bells beganne to play

Afar I heard her milking song."

He looked across the grassy lea,

To right, to left, "Ho Enderby!"

They rang "The Brides of Enderby!"

With that he cried and beat his breast;

For, lo! along the river's bed

A mighty eygre reared his crest.

And uppe the Lindis raging sped.

It swept with thunderous noises loud;

Shaped like a curling snow-white cloud,

Or like a demon in a shroud.

|

In the fourth line of the first of the above stanzas occurs

the word "welkin," much less often used now than formerly. It most

commonly signifies the sky, the vault of heaven. But we may often

understand the word merely in the sense of atmosphere, the whole expanse

of blue air. Indeed the word chiefly lingers in modern use in this

meaning, as is illustrated by the common idiom "to make the welkin

ring," This simply means to make all the air shake, and resound

with a noise or a shout. It is thus that the word is used in the

present poem.

In the following stanza observe the word "apace" — it is now

very old-fashioned. The meaning is "very quickly" or "suddenly" —

so that it does not at all appear to be what it means. We are apt

to think of the verb "to pace," meaning to walk slowly with full

strides; but apace is exactly the contrary of slowly. In the next

stanza the word "bairns," meaning young children, is familiar to anybody

acquainted with Scotch dialect; and we have got accustomed to think of

the word as purely Scotch. But it is not: it is very old English,

and is much used in the provinces outside of Scotland. In the next

stanza we find an especially curious and very ancient word, "eygre."

This word can be found in the most ancient Anglo-Saxon poems, and it

still lingers in various English provincial dialects. But it is

not often spelt in this way; the common spelling is "eagre." It

means an immense wave or billow; and it has a very weird effect in this

stanza. For it is the real tidal wave that the old woman describes

by that terrible word. All the flood that had come before was only

the precursor of the great sea rising to follow. Now it comes

roaring up the river, with a sound of thunder — all black below, all

white above with foam, so that it suggests to the old grandmother's

terrified fancy the idea of a great black demon moving with a funeral

shroud thrown over his head. You must understand that she sees the

wave at an angle, not in front. Now comes an excellent description

of the immediate result of the wave.

|

And rearing Lindis backward pressed,

Shook all her trembling bankes amaine;

Then madly at the eygre's breast

Flung uppe her weltering walls again,

Then bankes came downe with ruin and rout —

Then beaten foam flew round about —

Then all the mighty floods were out.

So far, so fast, the eygre drave,

The heart had hardly time to beat,

Before a shallow seething wave

Sobbed in the grasses at oure feet:

The feet had hardly time to flee

Before it brake against the knee,

And all the world was in the sea.

|

You must understand that the Lindis River flowing through a

very low country, constantly liable to inundation, has to be confined

between artificial banks to provide against accidents. In England

there are but very few rivers to which it has been found necessary to

furnish artificial banks; but in America many great rivers have to be

thus banked for immense distances. For instance, the great

Mississippi River flows between artificial banks for a distance of many

hundreds of miles; and when you read of terrible floods in the Southern

States, it generally means that the banks have been somewhere broken.

These banks rise much above the surrounding country, like great walls.

So it was in the landscape of the present poem — the river was flowing

between high banks like walls. When the great wave came from the

sea, moving at a tremendous speed, the first effect was to check and

throw back the river current; and this made a great counter wave.

But the counter wave could not resist the pressure of a sea wave; and

the consequence was that the whole force of the river was diverted

sidewards, with the result that the banks were at once broken to pieces.

That caused an immediate inundation of fresh water; but the fresh water

inundation was almost instantly followed by the rush of the sea, a much

more dangerous and terrible affair.

In the fourth line of the stanza about the rising of the

river, you must understand the word "weltering" to have the meaning of

the word "liquid"; and the term "weltering walls" to signify only high

waves rising like walls in vain opposition to the mighty tidal wave.

In the stanza following, the term "shallow seething wave" refers to the

first burst of the fresh water over the country; but the last three

lines of the same stanza refer to the rush of the sea following after.

Before a person had time even to move, the water was up to his knees;

the next minute it was high enough to cover the greater part of the

houses.

|

Upon the roofe we sate that night,

The noise of bells went sweeping by;

I marked the lofty beacon light

Stream from the church tower, red and high —

A lurid mark and dread to see;

And awsome bells they were to me,

That in the dark rang "Enderby."

They rang the sailor lads to guide

From roofe to roofe who fearless rowed;

And I — my sonne was at my side,

And yet the ruddy beacon glowed;

And yet he moaned beneath his breath,

"O come in life, or come in death!

O lost! my love, Elizabeth!"

|

Some of the houses, of two or three stories and strongly built,

withstood the flood for a time, and people took refuge upon the roofs.

Then from the neighbouring port sailors came with boats, and went from

roof to roof, to take the people away. The phrase "sailor-lads"

does not necessarily mean sailor boys or young sailors, though the

English "lad" strictly means a person between the ages of boyhood and of

manhood — let us say from sixteen to twenty-one. That is the

strict meaning; but for a very long time this word had a caressing

meaning, when it is attached to another word so as to make such

compounds, as for example, soldier-lads, sailor-lads. In these

instances the word "lad" has a meaning something like "dear" or "good."

The beacon fire, lighted upon the top of a church tower, is described as

"lurid." This word "lurid" has somewhat changed its meaning in

modern times. It is from the Latin, and the Latin meaning was a

dim green or a very dim yellow. The idea suggested by the Latin

word was the gloomy light in a deep forest, or the indistinct light in a

time of eclipse. But modern writers have used it a great deal, and

somewhat incorrectly, in the signification of red light — light having

an awful colour; for the ancient word always conveyed some idea of fear,

and this idea has never been lost in English. Whenever you see in

literature something described as lurid, you may be sure that the

meaning is a terrible and unnatural light. Of course the church

tower, used for a beacon light, had a square flat roof. As a

matter of fact, when we see the word "church tower" used in English, a

flat-topped tower is meant; the pointed form being more correctly

indicated by the word "spire."

So much for the scene described — the tragedy continues with

the lamentation of the sorrowing husband for his lost wife and children.

He asks her to come to him alive or dead, so that he may at least know

what has become of her in that awful night. If you think a moment

about the matter, you will see that the expression is quite natural;

people usually almost expect that those whom they loved will give them

some signs in case of sudden death — such as a visit in dreams, or an

apparitional visit. In this case the wife comes to her husband

dead, but not as a ghost:

|

And didst thou visit him no more?

Thou didst, thou didst, my daughter deare;

The waters laid thee at his doore.

Ere yet the early dawn was clear.

Thy pretty bairns in fast embrace,

The lifted sun shone on thy face,

Downe drifted to thy dwelling-place.

|

Many poets have used this fancy, in poetry about death by

drowning, and perhaps the idea first came into superior poetry with the

study of the popular ballads. In many English ballads we read

about the corpse of a mother and a child being carried by some flood or

storm to the door of the husband; sometimes the floating body which thus

returns is that of a betrayed girl. The idea is artistically

excellent, because it is so natural that no amount of use can wear it

out. It was a favourite incident with Rossetti. The

narrative continues, with certain reflections:

|

That flow strewed wrecks about the grass,

That ebbe swept out the flocks to sea;

A fatal ebbe and flow, alas!

To manye more than myne and me;

But each will mourn his own (she saith).

And sweeter woman ne'er drew breath

Than my Sonne's wife, Elizabeth.

|

In this stanza you must understand that the word "flow" means the

incoming tide, as ebb means the outgoing tide, though the use of the

word "flow," all by itself, in the first line is a little unusual.

The fifth line is the line to which I particularly wish to call your

attention:

But each will mourn his own.

This line, simple as any commonplace, simple as the most trite of

household phrases, is nevertheless, by reason of its opportune use in

this place, a very fine bit of human poetry. The old grandmother

remembers and relates the great destruction of life, both of animals and

human beings; and in the recollection of that immense calamity, with the

vision of a thousand past sorrows before her, she suddenly feels like

reproaching herself for talking so much about her own particular grief.

She apologises for this involuntary selfishness by citing the old saying

that each person feels his or her own sorrow most; "each will mourn his

own"; perhaps it is bad, yet who can help it, and who can fail to find a

kindly excuse for it?

Really that is almost the best line in the poem; and I want

to talk about it, because it suggests so many things. It is quite

true that each person best understands sorrow or joy by his or her

sorrow and joy; and in a certain way, a person is not wrong in imagining

his joy or pain to be the greatest joy or the greatest pain in the whole

world. There are many proverbial sayings, quoted in opposition to

the indulgence of personal feeling; I suppose that they really serve a

good purpose by checking a tendency to over-effusiveness. For

example, you have heard many sayings about the admiration of a mother

for her child, to the effect that every mother thinks her own child to

be the very best child alive. So a son invariably thinks that his

own mother is the best of all mothers; he may not say so, but he is very

likely to think so. And there are household phrases relating to a

corresponding feeling on the part of brother and sister, husband and

wife, father and son. The tendency to laugh at or to repress

expressions of such innocent feeling certainly have their special use:

we must so think of them. But most people utter the mockery, and

there stop — without asking themselves anything about the reason and

about the truth of such feeling. After all, there is a great deal

of truth in it. The value of an affection, the value of a

personality, to each of us is quite special. The son who thinks of

his mother as the best of all mothers thinks quite truly so far as the

relation of that mother to himself is concerned. She is the best

of all mothers for him; and no human being could ever take her place.

So with the relation of the child to the parent. It is a question

of relativity. Everybody feels this — though it is not easily

expressed by simple minds, which can only think as the old grandmother

thinks in the story, that each one cannot help "mourning his own," and

faintly justify by an appeal to universal experience, the declaration

that no one could be sweeter or better than the one who has been lost.

The poem concludes with the memories of the song and the singer:

|

I shall never hear her more

By the reedy Lindis shore,

"Cusha! Cusha! Cusha!" calling,

Ere the early dews be falling;

I shall never hear her song

"Cusha! Cusha!" all along.

Where the sunny Lindis floweth,

Goeth, floweth;

From the meads where melick groweth,

When the water winding down,

Onward floweth to the town.

I shall never see her more

Where the reeds and rushes quiver,

Shiver, quiver;

Stand beside the sobbing river.

Sobbing, throbbing, in its falling

To the sandy lonesome shore;

I shall never hear her calling,

"Leave your meadow grasses mellow.

Mellow, mellow;

Quit your cow-slips, cow-slips yellow;

Come uppe Whitefoot, come uppe Lightfoot;

Quit your pipes of parsley hollow.

Hollow, hollow;

Come up Lightfoot, rise and follow;

Lightfoot, Whitefoot,

From your clovers lift the head;

Come uppe Jetty, follow, follow,

Jetty, to the milking shed."

|

|

|

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)