|

|

THE POETRY OF JEAN INGELOW

|

mong the

women poets of England, most critics would, I imagine, agree in

assigning the first place to Elizabeth Barret Browning. The

next place belongs probably to Jean Ingelow. True, it is not a

very difficult matter to decide the order of merit, seeing that

English poetesses of any note may be counted almost on the fingers

of one hand. It might be interesting to discuss the question

whether there is any peculiarity in the female character to account

for this rareness of the poetic gift. That women can write

poetry, and poetry of a very high order, no one who has studied the

works of Mrs. Browning, Jean Ingelow or

Adelaide Proctor, can reasonably

doubt.

The most striking feature of Miss Ingelow's poetry, and that

which renders it so peculiarly attractive, is its metrical beauty.

To appreciate this fully, it ought to be read aloud, in order, as

George Macdonald said in one of his most fascinating books, to "get

all the good of its outside as well as inside—its sound as well as

thought, the one being the ethereal body of the other." Read

thus, Jean Ingelow carries you away upon a flood of delicious sound

which wholly fascinates and almost intoxicates you with its beauty.

Everyone must be struck by the wonderful ease of expression, the

smoothness, the exquisite music of her rhymes. Hers truly is

|

"The voice which like a stream could run

Smooth music from the roughest stone." |

She is, above all, a singer, and she sings with a sweet rhythmic

cadence which entrances us, so that we are in danger of forgetting

the sense in the delight of the sound. If poetry consistent

only in beauty of form, she would be an infinitely greater poet than

Mrs. Browning. Take, for example, the worst poem (probably)

that she ever wrote, "Divided," and

read it aloud, listening to the sound and shutting your mind to the

meaning, and how deliciously melodious it his. Or take such a

verse as this, chosen, at haphazard, from "Requiescat

in Pace":—

|

"Men must die—one dies by day, and near

him moans his mother;

They dig his grave, tread it down, and go from it full

loth.

And one dies about the midnight, and the wind moans and no other,

And the snows give him a burial. And God

loves them both," |

It is really difficult to choose examples of special beauty where

all is so beautiful. It would hardly be going too far to

assert that Jean never wrote an unmusical line, and never could

write one. Perhaps the most striking instance or this

wonderful gift of poetic beauty is that ballad written for the

Portfolio Society, "Persephone."

Place that side by side with any one of the best of E. B. Browning's

ballads, and how infinitely superior it is in the mere external

qualities of form, rhythm, and melody.

|

"She reigns upon her dusky throne,

'Mid shades of heroes dread to see;

Among the dead she breathes alone,

Persephone — Persephone!

Or seated on the Elysian hill

She dreams of earthly daylight still,

And murmurs of the daffodil.

"A voice in Hades soundeth clear,

The shadows mourn and flit below;

It cries—'Thou Lord of Hades hear,

And let Demeter's daughter go.

The tender corn upon the lea

Droops in her goddess gloom when she

Calls for her lost Persephone.'" |

The second special characteristic of Miss Ingelow's poetry

is, I think, its facility of expression. As she is a living

writer, and therefore has not yet been torn to pieces and dissected

by the biographers and critics, we do not know the secrets of her

manner of working; but if the impression produced on the readers

mind be considered a trustworthy guide, her poems run straight from

her brain (or soul) on to the paper, and hardly need an after touch.

Half their charm lies in their apparent spontaneity and absence of

effort.

Thirdly, she is pre-eminently the poetess of nature, as she

is, and because she is, the High-priestess of Beauty. She

seems to have drunk so deep of nature's loveliness that she is

inebriated with it. Like Shelley—though in a lesser degree—she

often catches the every spirit of nature and photographs it in her

verse. The well-known ballad, "The

High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire," is an example of what I

mean. It is not merely that she describes the scene—the flat

Lincolnshire fen, the river flowing through the reeds, the solitary

figure standing out against the sunset sky—so that we can see it in

the mind's eye; the power of vivid description is no uncommon gift;

but that the very verse itself seems permeated with the tranquil

beauty of the afternoon, so that you seem to feel the strange hush,

the lazy stillness, the indescribable sensation which such an

afternoon does actually produce on the mind. And this effect

is given, not with pages of elaborate description, but with broad

strong touches such as:"

". . . dark against day's golden

death,

She moved where Luidis wandereth; |

Or . . . .

"The swanherds where their sedges are

Moved on in sunset's golden breath.' |

But no quotations can give any idea of the effect produced by

reading the poem carefully through, and giving oneself up to the

enjoyment of it. Another instance of this peculiar power is

found, to my mind, in the description of dawn in

book vi of "A Story of Doom ":

|

. . . . . . .

. "Then he lift

His eyes, and day had dawned. Right suddenly

The moon withheld her silver, and she hung

Frail as a cloud. The ruddy flame that

played

By night on dim, dusk trees, and on the flood,

Crept red amongst the logs, and all the world

And all the water blushed and bloomed. The

stars

Were gone, and golden shafts came up, and touched

The feathered heads of palms, and green was born

Under the rosy cloud, and purples flew

Like veils across the mountains." |

Or read that beautiful poem, "Scholar and

Carpenter"—a poem which is peculiarly characteristic of its

author as regards the three points which I have mentioned,

especially the first seven verses culminating in that splendid

outburst of trust and confidence:

|

"Grand is the leisure of the earth

She gives her happy myriads birth,

And afters harvest fears not dearth,

But goes to sleep in snow-wreaths dim.

Dread is the leisure up above,

The while He sits whose name is Love,

And waits, as Noah did for the dove,

To wit if she would fly to him." |

In the fourth verse of the same poem she tells us what she considers

to be the secret of her sympathy with nature. Speaking of her

heart, she says—

|

"The morning freshness that she viewed

With her own meanings she endued,

And touched with her solicitude

The natures she did meditate." |

Now those lines give the keynote to Jean Ingelow's poetry, the

keynote both to its strength and to its weakness, its merits and

defects. Her poetic nature is like a rare and sensitive

instrument, played on by nature in all her moods. When she

yields herself wholly to nature, and simply writes down the

impressions of her influence, as they photograph themselves upon her

brain, she succeeds most perfectly. But when, reversing the

position, she considers nature as the instrument to be played on by

her soul, she fails. Take, for instance, a thoughtful little

poem, and one not very easy to understand, "The

Nightingale Heard by the Unsatisfied Heart." She speaks of

the nightingale thus:

|

"But thou in the trance of light.

Stayest the feeding night,

And Echo makes sweet her lips with

the utterance wise;

And casts at our glad feet,

In a wisp of fancies fleet,

Life's fair, life's unfulfilled,

impassioned prophecies.

Her central thought full well

Thou hast the wit to tell,

To take the sense o' the dark and

to yield it so;

The moral of moonlight

To set in a cadence bright,

And sing our loftiest dream that we

thought none did know." |

Now is it a fair criticism to call those lines untrue in sentiment?

Passing over their quite unnecessary obscurity, I accuse them of a

far greater fault―namely, untruth

to the spirit of nature in ascribing to the nightingale thoughts

belonging only to the human soul, instead of describing the human

soul producing those thoughts under the influence of nature, or, if

you will, drawing out the thoughts inherent in nature and expressed

to the soul of the listener in the nightingale's song. For

surely the great and eternal truths of God lie hid in the heart of

nature, as heat lies imprisoned in the black heart of the coal, and

only the God-given fire of human thought has power to draw them

forth into life. Not that a poet is necessarily untrue when he

puts into the mouth of nature human thought, so long as that thought

is in harmony with nature. But there is an incongruity (or so

at least it seems to me) in a nightingale having "the wit to tell

life's central thought," and "sing our loftiest dream that we

thought none did know."

The chief fault of Jean Ingelow's poetry is, surely, that it

is often too fanciful to be true. One is reminded in reading

it of a deep saying of that great and beautiful thinker whom I have

already quoted—"Fancy plays like a squirrel in its circular prison,

and is happy; but Imagination is a pilgrim on the earth, and her

home is in heaven." She fails most when she tries to go

deepest. Her writing is essentially feminine; her strength

lies in delicacy of imagination, power of description, warm human

sympathies, deep religious sentiments and emotions. Whenever

she becomes metaphysical, whenever she begins to reason deeply, she

becomes obscure and often laboured. Take, for instance, the

poem called "Honours", especially

the second part. The Subject is not an original; it deals with

the old problems and difficulties of life; but there is a vagueness

and want of consecutive argument, clearness, and comprehension in

its treatment, so that the reader is apt to get tired and impatient

with the effort to follow the tangled thread of the poet's thought.

Near the end of the poem she rises to a far more congenial sphere of

religious feeling, and instantly becomes beautify and interesting.

It is the Same with "Scholar and Carpenter"; a poem of a far higher

order, I venture to think, and the fault is even more pronounced in

some of the "Songs on the Voices of

Birds," and in the "Song of the Uncommunicated Ideal," a poem as

vaguer and obscure as its title.

It is as a ballad-writer, a story-teller in verse, that Miss

Ingelow is at her best. She has a great power of telling a

story, especially a pathetic story. I think that "Laurance,"

"Brothers and a Sermon," and "The

Dreams that came True," are good specimens of her stories in

verse, as "Persephone" and the "High

Tide" are the most striking of her ballads properly so called.

The sermon in "Brothers and a Sermon" is perhaps the best poem she

has ever written. It is full of deep religious feeling—not

merely religious sentiment, but real, living, practical faith in a

personal God—faith which finds expression in deep, passionate

sympathy with human suffering. No one can read it without

being elevated, or at least impressed, by its sublime earnestness,

without being touched by its heartrending pictures of human misery

in the stories of "The Drunkard's Wife," and of "The Outcast Woman,"

by the exquisite contrast between human cruelty and hardness and the

Divine tenderness and compassion.

I cannot forbear to quote a few lines which to my mind are

especially beautiful. The preacher is describing a wife

listening to her husband's drunken song, as he comes home across the

snow:

|

"O thou poor soul, it is the night—the night;

Against thy door drifts up the silent snow,

Blocking thy threshold: 'Fall,' thou sayest, 'fall, fall,

Cold snow, and lie and be trod underfoot.

Am not I fallen? Wake up, and pipe, O wind,

Dull wind, and beat and bluster at my door;

Merciful wind, sing me a hoarse rough song,

For there is other music made to-night

That I would fain not hear. Wake, thou still sea,

Heavily plunge. Shoot on, white waterfall.

O, I could long, like thy cold icicles,

Freeze, freeze, and hang upon the frosty cliff.

And not complain, so I might melt at last.

In the warm summer sun, as thou wilt do!

"'But woe is me! I think there is no sun;

My sun is sunken, and the night grows dark;

None care for me. The children cry for bread,

And I have none, and nought can comfort me;

Even if the heavens were free to such as I,

It were not much, for death is long to wait,

And heaven is far to go!'

"And speakest thou thus,

Despairing of the sun that sets to thee,

And of the earthly love that wanes to thee,

And of the heaven that lieth far from theirs?

Peace, peace, fond fool! One draweth near thy door

Whose footsteps leave no print across the snow;

Thy sun has risen with comfort in His face,

The smile of heaven, to warm thy frozen heart,

And bless with saintly hand. What! is it long

To wait and far to go? Thou shalt not go;

Behold, across the snow to thee he comes,

Thy heaven desends, and is it long to wait?

Thou shalt not wait: 'This night, this ,night,' He saith,'

I stand at the door and knock.'" |

Jean Ingelow is probably more widely read as a novelist than

as a poet. It is the taste of the age to prefer prose to

poetry, and the fashion just now with many writers to extol

prose-poetry at the expense of verse. Miss Ingelow herself,

poet as she is, speaks slightingly of versifying in one of her

latest stories, "John Jerome." True, a poet is not only, or

necessarily, a writer of verses. There been plenty of

"glorious poets that never have written a line," and plenty more,

like Macdonald, who have written excellent prose-poems. "He

who forgives not is not forgiven, and the prayer of the Pharisee is

as the weary beating of the surf of hell, while the cry of a soul

out of its fire sets the heart-strings of love trebling." None

but a poet could have written that, and no setting of rhyme and

metre could make the poem more perfect. And yet the poet—not

the versemaker—has a higher claim to our gratitude in verse than in

prose, for many reasons, of which three will suffice:

(1) Verse is more difficult than prose. It costs more

labour, and therefore deserves to be rated higher.

(2) Verse is essence of thought, concentrated, condensed, and

therefore more forcible than prose, which, however beautiful in

form, must of necessity be more prolix and diffuse.

(3) Verse is, generally speaking, a more beautiful setting

than prose. I grant that the passage from George Macdonald

just quoted is an exception to this rule. But is it not so

just because it is so rhythmic, so melodious, that it seems prose

trembling on the very verge of averse?

The ordinary prose-poet hews his thought, like gold, from the

mine of his mind, and offers it to the world in the rough; the

verse-poet, after that he has hewn it from the mine, melts it in the

crucible of emotion, stamps it with the impress of his soul's

labour, and sends it forth to the world in a form that will ring on

when the equally golden thought of the prose-poet has, from its

inferiority of form, been lost and forgotten.

K. E. COLEMAN.

|

|

――――♦――――

DON JOHN.

[by JEAN INGELOW:

Roberts 1885.]

"The motif stems to be hackneyed; but it is

not so, for here we have the time-honored expedient of changing children

at nurse treated in an entirely unprecedented, and yet perfectly

plausible fashion. The irresponsible young wet-nurse whose

imagination has been fired, and her head head turned, by an immense

consumption of the fiction furnished by a cheap circulating library,

makes, in the first instance instance, in mere wantonness, the

experiment of substituting her child for the one which had been confided

— somewhat too unquestioningly — to her care, while a severe epidemic of

scarlatina took its long course through the nursery of her employers.

Again a chain of curious and very creditably-devised chances favor —

almost necessitate — the maintenance of the deception; and at length it

comes about, through the sudden death, by accident, of her accomplice in

the dangerous game she had been playing, that the nurse herself is not

entirely certain whether it is the Johnstone baby or hers which the

family reclaim, while she is herself prostrated by severe illness.

The frightened woman keeps her guilty and yet rather absurd secret for a

little while, but then the miserable confession will out, and the

unhappy parents who have been the victims of this enraging trick find

that they can do no better than pack the unprincipled nurse off to

Australia, adopts this other child, and bring up the twin boys exactly

alike. The history of the growth of their characters, and the

development of their fates, is a singular and affecting one. It is

the best told of Miss Ingelow's tales, — the most direct and dramatic

and symmetrical; and, in short, Don John is, to our mind, a beautiful

little story; a finished and charming specimen of that minor English

fiction which is often as good, from a literary point of view, as the

best produced elsewhere." [Atlantic. |

|

――――♦――――

AN UNCONVENTIONAL NOVEL.

JOHN JEROME. HIS THOUGHTS AND WAYS. A Book without a

Beginning. By JEAN INGELOW, Boston: ROBERTS BROTHERS.

If Jean Ingelow were of the masculine gender we might describe the

author of "John Jerome" as making romance in shirt sleeves, so free and

easy are the methods. You know from the subtitle that it is a

story without a beginning, which means, we suppose, that a romance may

commence anywhere. Precise readers, accustomed to the cut and

dried ways of romance, may not appreciate the introduction to "John

Jerome," for it is rather intangible at best and uncertain. John

Jerome hunts the larvæ of lepidopterous

insects, teaches little village boys to distinguish the differences

between ordinary caterpillars and silkworms, and takes a decided

interest in the ailanthus. John Jerome has a limp. Some

years before in England, where the story takes place, two little girls

had broken through the ice, and John Jerome had saved them but had been

hurt in the rescue, and rheumatism had set in, and he had been slightly

crippled. Katharina and Anna, his cousins, were the young women he

had saved. Grateful? Of course they were. The girls

loved their savior, but Alma had married later a very queer man,

Godfrey, and Katharina had engaged herself to another. With

Katharina John Jerome's relationship is of the happiest kind, and it is

at her instigation that he writers the book.

"John Jerome" is endowed with many original ideas.

Occasionally he has a bad fit of spleen, and is wont to argue his

conditions of mind with himself in dialogues where "I" and "myself"

interchange ideas. If a man is dissatisfied with everything the

following is presented as an infallible receipt for a cure: You choose

two Japanese fans with magenta sunsets, a half pint of raw green

gooseberries, and three cats, and you establish yourself near a tallow

chandler's, and you "eat the gooseberries, beat the cats, and look hard

at the screens, considering remorsefully all the time how we have ruined

the taste of the Japanese for art and given them nothing to make up for

the loss. When you have set your teeth on edge with the

gooseberries, and are chilled to the bone with the east wind, and have

breathed the odors of tallow and listened to the discord of the cats,

release them and return home." Jean Ingelow indulges in many

whimsicalities, and is as discursive as Southey in his "Doctor."

Here are disquisitions on female beauty where it is conclusively shown

that the ideal Greek woman had a small head and big feet and that the

beauty of mediæval times had a

vivacious look and not a languid one. Miss Ingelow is not a Vernon

Lee, but her art criticisms are sharp and clever. This may be a

slur on the Rossettians, who admire "a hungry and despairing face, with

a lean, lanky figure, and what our grandmothers called gooseberry eyes."

We idealize "the wrong way." Flattery has made women

Juno-eyed, with feet that won't support her. In the current of the

story Jean Ingelow has her talk about women and women's rights.

John Jerome sees a troop ship depart, and philosophizes on the "girls we

left behind us." What are women's faults? First, she loves

luxury, but principally she never will rise to the height of her

aspirations, because she is wanting in the power of organization, and

her greatest defect is that "she does not love her own, she loves the

more selfish sex." In man there is human nature, in woman a vast

deal of human art; and finally Jean Ingelow sums it up when Katharina

remarks, "Women are not angels."

The whimsicalest of all men is Godfrey, who has married Anna.

Godfrey lives in a travelling van, associates with tinkers, he has a

Borrowish flavor. Godfrey is a bit crazy, and so is his wife, but

his method of living in the heather gives Jean Ingelow the opportunity

to write delightfully of nature, and her fine poetical faculties have in

prose their full swing. Katharina is not happy, although John

Jerome is her best friend. Another, which other is Tudor Smutt,

treats the pretty Kathrina as would a cad. Kathrina's grandmother,

from whom she has expected money, her nieces being her prospective

heiresses, suddenly loses her means. Tudor Smutt, who is a snob,

marries Lavinia Cohen, who is greasy but opulent. George Jerome,

with the limp, goes to the United States, where he finds a bone-setter.

A bone-setter is a humbug, and always was one, but there is a dark

closet in the brightest mind. We do not mean to say that the

author believes in the bone-setter, but it looks as if she did.

Anyhow, the bone-setter does his work for the man with the limp, and

Jerome hobbles no more. He comes home, and Katharina, who has

loved him, only believing that she once did care for the prig Smutt,

eventually marries John Jerome, who really after all never had anything

more "than a limp not worth mentioning." Miss Ingelow's book, when

you have done a little plodding at the beginning, opens up briskly and

pleasantly, and the jaunt through the story is a delightful one.

|

|

――――♦――――

ATLANTIC MONTHLY

Vol LXXIII., 1894.

A MOTTO

CHANGED, by Jean Ingelow. (Harpers.) The

changed motto is; “A little less than

kin, and more than kind,” and presumably has reference to the fact that

the young hero is really only the adopted child of his reputed father,

he having been one of those infants, not uncommon in fiction, who are

found on wrecked vessels, the sole survivors. The not very

interesting love-story of this youth forms the main motive of the tale,

though the heroine’s precocious little brother, — who, when first

introduced to us, is discussing the question “whether we owe any duties

towards vermin,” — unlike his delightful predecessors, the clever and

original children in the author’s earliest novel, is sometimes

distinctly tiresome. This condemnation the story itself could not

escape, — being as it is slight in texture, commonplace in incident, and

weak in characterization, — if it were not so brief in the telling.

|

|

_______________

HARPER'S MAGAZINE

Vol. LXXXVIII., 1894.

THE young people of

twenty-five or thirty years ago used to read, with no little interest

and pleasure, certain pretty, healthful stories written for them by Miss

Jean Ingelow, then a comparatively young person herself. They were

all about girls and boys, and a suspicious jackdaw, and minnows with

silver tails, and wild-duck-shooters, and such things, and they did

nobody any harm, although they are now almost forgotten. “Off the

Skelligs” came much later from the same writer, and attracted marked

attention from a more mature class of readers. It was an unusual

tale, of undoubted but unequal merit. Since then Miss Ingelow has

rarely been heard of and it is with a feeling almost of surprise that

her name is found upon the cover of a new novel. A Motto

Changed is not a child’s story altogether, although its heroine

and its hero are very youthful. The lover is just of age, and

young for his years, and the girl he loves is not very high up in her

teens; but fathers and mothers will be touched by their joys and their

sorrows, and sons and daughters will follow them eagerly to the end of

their career, as Miss Ingelow has set it down. There is a funny

little chap of eight or nine who makes remarkable statements about the

duty which mankind owes to vermin; and there is a funnier half-Malay,

half-English, white and brown baby—both of whom will appeal to a very

juvenile set of readers indeed. The book, therefore, is destined

to meet with general popularity, which, without being in any way a great

or an unusual book, it certainly deserves. |

|

_______________

NEW YORK TIMES

19 December, 1893.

A Novel by Jean Ingelow.

A MOTTO CHANGED; OR, A LITTLE LESS THAN KIN AND MORE THAN

KIND. A Novel. By Jean

Ingelow. New-York: Harper & Brothers.

Jean Ingelow retains her old faculty for story telling.

She interests you without seeming to make an effort to be interesting,

and with scarcely any apparent artifice. She wastes no time on

elaborate descriptions of places or people. From the opening of

this new novel, a simple love story with plenty of variety of character

and incident, the reader's attention is held closely. She lets her

personages speak for themselves, and they speak well.

Sometimes her English is a little odd for a poet whose songs

are so simple and charming. But "onto" is in the dictionary, and

"presented with" has passed into common speech, even if Mr. Pater and

Mr. James and Mr. Aldrich and others whom we esteem as teachers of

modern English avoid that word and that phrase.

Rhodes Mainwaring is a big, burly, blonde youth of

twenty-one, simple, sound-hearted, unsophisticated, idle, because he has

never had any real inducement to choose a calling, but not lazy and a

real hero. Isabel, whom he loves, is a pretty, ordinary,

well-bred, middle-class girl. The course of their love does not

run smoothly, at first, but its story is very pretty and touching, and

the book is full of delightful humor that belongs to is as a component

part of the fabric.

The characters are all well drawn, especially grave, elderly

Mr. Larkin, who writes "leaders" on important topics, and his little

boy, the son of his second wife, who is the most pleasing example of the

precocious child we have lately met with in fiction. The study of

his infantile mind grappling with scientific problems of its own

invention is most amusing and most natural too. Rowland was

probably taken directly from real life. |

|

――――♦――――

NEW YORK TIMES

August 7, 1897.

Of Jean Ingelow.

ANECDOTES ABOUT HER AND FACTS

ABOUT HER BOOKS.

The late Jean Ingelow (giving the "g" in the surname a softened sound)

was born in 1820 in Boston, Lincolnshire. Her father, who was a

banker, moved to Ipswich, and The Academy says that "banking and

Evangelicalism have conspicuously run together in certain families, and

they did in hers. Almost Quakerlike some of her likings and

aversions might he called." Something that she seems to have always

held in horror was human strife, and so in Jean Ingelow's verse there

never is any allusion to war. The call of the bugle, the cry to arms

were distressing sounds to her. She carried this so far that it is

said when she had written in "Kismet" the story of a lad's love for

liberty and his delight in the sea, some critic told her that boys in

reading the book might be fired with the idea of entering the navy.

That so disturbed Jean Ingelow that she took the work and revised it

carefully, changing some of the parts.

Jean Ingelow's early life, her first ambitions, are by no

means easy to follow. Exceedingly modesty, she was particularly

reticent about herself. To those who knew her intimately she would

sometimes express astonishment at her own success. Perfectly quiet

in her manner, she was deliberate in all she did, and she was forty-three

before she published her first acknowledged book of verse.

It is to our credit that appreciation of Jean Ingelow first

came from the United States, and it is possible that she is even better

liked here than in England. Counting the number of volumes purchased

as evidence of merit, it is computed that over 200,000 volumes of Jean

Ingelow's works have found purchasers in this country. Oliver

Wendell Holmes and James Russell Lowell were among her earliest admirers,

and praise from either of these was praise indeed. "Tennyson was

generous in his encomiums," and above all Ruskin, "whose praise has always

been precious to women, was at her feet."

Jean Ingelow's first collected edition of poems was published

by Messrs. Longman & Co. It was taken up by the public in rather a

deliberate manner. Anyhow, in good time this first edition was

exhausted. Then Miss Ingelow went to London to treat with her

publishers for a second edition. But the Messrs. Longman, so it is

said, rather declined venturing on a second edition. There might

have been risks, so it was intimated, which the house did not deem it

prudent to take then. Miss Ingelow, somewhat disappointed, was

leaving the establishment when she passed a man hurrying up to the office

of the Messrs. Longman, and presently she was asked to return, a messenger

having been sent her. It seems somebody had just asked for 500

copies of "Jean Ingelow's Poems," and at once the necessity of a second

edition became imperative. It had taken some year or more for the

appreciation of her poems to come, but from that time on her merits were

confirmed, and so we have to-day the twenty-third English edition of her

first series of "Poems." "Imagine my feelings of envy and

humiliation," Christina Rossetti is reported to have said when she

received only a volume of the eighteenth edition of "Jean Ingelow's

Poems." The first edition of "Poems by Jean Ingelow" appeared in

1863. Her first volume was "A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and

Feelings," issued anonymously in 1850.

With fairly comfortable means, though Miss Ingelow received

handsome compensation for her works, it is believed that the money she

derived from her copyrights was for the major part dispensed in charity.

She was the most generous of women.

There is an amusing story told relating to nightingales,

which sweet songsters she often Introduces in her verses. But

nightingales were mere hearsays to her, for up to 1868 she had never heard

one. Paying a special visit to some friends who boasted of a grove

in which nightingales warbled, Miss Ingelow went out one May evening to

listen to the bird orchestra. To greet so distinguished an audience

the nightingales were singing their sweetest, and all else were silent.

Then Miss Ingelow said: "Are they singing? I don't hear anything."

The lady was by no means deaf, but the fact is she had forgotten to remove

some cotton from hers ears, for, the evening being damp and raw, she had

been afraid of catching a possible cold.

To pose as a poet was something Jean Ingelow despised.

She liked best to talk plain prose. She carried this so far that

when invited to some dinner as a celebrity, and expected to show off, she

was invariably disappointing. She talked well enough, but discussed

invariably commonplace topics.

To write such fine verse as did Jean Ingelow means that she

had strong powers of concentration. The idea comes, but to make it

grow, to give it leafage and flowers, to endow the blooms with perfume, is

a longer, a slower process. Some one who knew her well says that in

the time when she was writing she did not read much, and she was

"singularly ignorant of contemporaneous literature." Once she

said, "It is a great price to pay for writing successfully, but I dare not

read what others are writing in the same vein. I have such a dread

of unconsciously borrowing their ideas."

Poems that are fully twenty years old must have a vital force

of their own so as to be read to-day. Poets come and poets go, and

their verses reflect the incidents, the feelings of the present moment,

and this is but natural. The flicker of one sunrise is the prelude

of the sombreness of a night which follows, but the sweetness, the

freshness, the naturalness of the true poet are not evanescent.

It is Jean Ingelow's pitying tenderness which leaves its

Impress. How often has not Elizabeth's call to her cows been

repeated?

|

Cusha! cusha! cusha! calling

Ere the early dews were falling.

*

*

*

*

*

*

Leave your meadow's grasses mellow,

Mellow, mellow:

Quit your cowslips, cowslips yellow,

Come uppe Whitefoot, come uppe Light-foot,

Quit the stalks of parsley hollow,

Hollow, hollow."

[High Tide on the

Coast of Lincolnshire] |

What a sweet, sad refrain is here! True grief never

found a more poignant utterance than in these six lines:

|

Is there never a chink in the world above

Where they listen for words from below?

Nay, I spoke once, and I grieved thee sore,

I remember all that I said,

And now thou wilt hear me no more-no more

Till the sea gives up her dead."

[Supper at the Mill] |

The remains of Miss Ingelow were interred in the family grave

at West Brompton Cemetery. Besides relatives and friends present,

there were a number of Americans, chiefly ladies. The Bishop of

Wakefield and the Rev. G. R. Thornton of St. Barnabas's performed the

funeral service. The coffin, which was of polished oak, with brass

mountings, bore upon the breastplate the words, "Jean Ingelow. Born March

17, 1820; died July 20, 1897." Above this was fastened a cross of

roses, and on the card were the words, "Mr. Ruskin. In sorrow and

affectionate memory." A bouquet of sweet mignonette was inscribed,

"Antoinette Sterling. With dear love. There is no death; there

is no beginning or end to life." Maxwell Gray sent a wreath of

laurel leaves, intertwined with gold braid, and the words, "Ave, atque

vale!" After the Bishop of Wakefield had pronounced the benediction,

Mme. Antoinette Sterling by the open grave sang "The Lord Is My Shepherd."

|

|

____________________________

Lives

of

Girls Who Became Famous.

by

Sarah K. Bolton,

Author of Poor Boys Who Became Famous, Social

Studies in England, etc.

1914.

JEAN INGELOW.

THE same friend who had

given me Mrs. Browning's five volumes in blue and gold, came one day with

a dainty volume just published by Roberts Brothers, of Boston. They

had found a new poet, and one possessing a beautiful name. Possibly

it was a nom de plume, for who had heard any real name so musical

as that of Jean Ingelow?

I took the volume down by the quiet stream that flows below

Amherst College, and day after day, under a grand old tree, read some of

the most musical words, wedded to as pure thought as our century has

produced.

The world was just beginning to know The High Tide on the

Coast of Lincolnshire. Eyes were dimming as they read,—

|

"I looked without, and lo! my sonne

Came riding downe with might and main:

He raised a shout as he drew on,

Till all the welkin rang again,

'Elizabeth! Elizabeth!'

(A sweeter woman ne'er drew breath

Than my sonne's wife Elizabeth.)

"'The olde sea wall (he cried) is downe,

The rising tide comes on apace,

And boats adrift in yonder towne

Go sailing uppe the market-place.'

He shook as one who looks on death:

'God save you, mother!' straight he saith;

'Where is my wife, Elizabeth?'" |

And then the waters laid her body at his very door, and the

sweet voice that called, "Cusha! Cusha! Cusha!" was stilled forever.

The Songs of Seven soon became as household words,

because they were a reflection of real life. Nobody ever pictured a

child more exquisitely than the little seven-year-old, who, rich with the

little knowledge that seems much to a child, looks down from superior

heights upon—

|

"The lambs that play always, they know no better;

They are only one times one." |

So happy is she that she makes boon companions of the

flowers:—

|

"O brave marshmary buds, rich and yellow,

Give me your honey to hold!

"O columbine, open your folded wrapper,

Where two twin turtle-doves dwell!

O cuckoopint, toll me the purple clapper

That hangs in your clear green bell!"

|

At "seven times two," who of us has not waited for the great

heavy curtains of the future to be drawn aside?

|

"I wish and I wish that the spring would go faster,

Nor long summer bide so late;

And I could grow on, like the fox-glove and aster,

For some things are ill to wait."

|

At twenty-one the girl's heart flutters with expectancy:—

"I leaned out of window, I smelt the white clover,

Dark, dark was the garden, I saw not the gate;

Now, if there be footsteps, he comes, my one lover;

Hush nightingale, hush! O sweet nightingale wait

Till I listen and hear

If a step draweth near,

For my love he is late!" |

At twenty-eight, the happy mother lives in a simple home,

made beautiful by her children:—

|

"Heigho! daisies and buttercups!

Mother shall thread them a daisy chain."

|

At thirty-five a widow; at forty-two giving up her children

to brighten other homes; at forty-nine, "Longing for Home."

"I had a nestful once of my own,

Ah, happy, happy I!

Right dearly I loved them, but when they were grown

They spread out their wings to fly.

O, one after another they flew away,

Far up to the heavenly blue,

To the better country, the upper day,

And—I wish I was going too." |

The Songs of Seven will be read and treasured as long as

there are women in the world to be loved, and men in the world to love

them.

My especial favorite in the volume was the poem Divided.

Never have I seen more exquisite kinship with nature, or more delicate and

tender feeling. Where is there so beautiful a picture as this?

|

"An empty sky, a world of heather,

Purple of fox-glove, yellow of broom;

We two among them, wading together,

Shaking out honey, treading perfume.

"Crowds of bees are giddy with clover,

Crowds of grasshoppers skip at our feet,

Crowds of larks at their matins hang over,

Thanking the Lord for a life so sweet.

*

*

*

*

*

"We two walk till the purple dieth,

And short, dry grass under foot is brown;

But one little streak at a distance lieth

Green like a ribbon to prank the down.

"Over the grass we stepped into it,

And God He knoweth how blithe we were!

Never a voice to bid us eschew it;

Hey the green ribbon that showed so fair!

*

*

*

*

*

"A shady freshness, chafers whirring,

A little piping of leaf-hid birds;

A flutter of wings, a fitful stirring,

A cloud to the eastward, snowy as curds.

"Bare, glassy slopes, where kids are tethered;

Round valleys like nests all ferny lined;

Round hills, with fluttering tree-tops feathered,

Swell high in their freckled robes behind.

*

*

*

*

*

"Glitters the dew and shines the river,

Up comes the lily and dries her bell;

But two are walking apart forever,

And wave their hands for a mute farewell.

*

*

*

*

*

"And yet I know past all doubting, truly—

And knowledge greater than grief can dim—

I know, as he loved, he will love me duly—

Yea, better—e'en better than I love him.

"And as I walk by the vast calm river,

The awful river so dread to see,

I say, 'Thy breadth and thy depth forever

Are bridged by his thoughts that cross to me.'"

|

In what choice but simple language we are thus told that two

loving hearts cannot be divided.

Years went by, and I was at last to see the author of the

poems I had loved in girlhood. I had wondered how she looked, what was her

manner, and what were her surroundings.

In Kensington, a suburb of London, in a two-story-and-a-half

stone house, cream-colored, lives Jean Ingelow. Tasteful grounds are

in front of the home, and in the rear a large lawn bordered with many

flowers, and conservatories; a real English garden, soft as velvet, and

fragrant as new-mown hay. The house is fit for a poet; roomy,

cheerful, and filled with flowers. One end of the large, double

parlors seemed a bank of azalias and honeysuckles, while great bunches of

yellow primrose and blue forget-me-not were on the tables and in the

bay-windows.

But most interesting of all was the poet herself, in middle

life, with fine, womanly face, friendly manner, and cultivated mind.

For an hour we talked of many things in both countries. Miss Ingelow

showed great familiarity with American literature and with our national

questions.

While everything about her indicated deep love for poetry,

and a keen sense of the beautiful, her conversation, fluent and admirable,

showed her to be eminently practical and sensible, without a touch of

sentimentality. Her first work in life seems to be the making of her

two brothers happy in the home. She usually spends her forenoons in

writing. She does her literary work thoroughly, keeping her

productions a long time before they are put into print. As she is never in

robust health, she gives little time to society, and passes her winters in

the South of France or Italy. A letter dated Feb. 25, from the Alps

Maritime, at Cannes, says, "This lovely spot is full of flowers, birds,

and butterflies." Who that recalls her Songs on the Voices of Birds,

the blackbird, and the nightingale, will not appreciate her happiness with

such surroundings?

With great fondness for, and pride in, her own country, she

has the most kindly feelings toward America and her people. She says

in the preface of her novel, Fated to be Free, concerning this work and

Off the Skelligs, "I am told that they are peculiar; and I feel that they

must be so, for most stories of human life are, or at least aim at being,

works of art—selections of interesting portions of life, and fitting

incidents put together and presented as a picture is; and I have not aimed

at producing a work of art at all, but a piece of nature." And then

she goes on to explain her position to "her American friends," for, she

says, "I am sure you more than deserve of me some efforts to please you.

I seldom have an opportunity of saying how truly I think so."

Jean Ingelow's life has been a quiet but busy and earnest

one. She was born in the quaint old city of Boston, England, in 1830

[ED.—in fact 1820]. Her father was a well-to-do banker; her

mother a cultivated woman of Scotch descent, from Aberdeenshire.

Jean grew to womanhood in the midst of eleven brothers and sisters,

without the fate of struggle and poverty, so common among the great.

She writes to a friend concerning her childhood:—

"As a child, I was very happy at times,

and generally wondering at something.... I was uncommonly like other

children.... I remember seeing a star, and that my mother told me of God

who lived up there and made the star. This was on a summer evening.

It was my first hearing of God, and made a great impression on my mind.

I remember better than anything that certain ecstatic sensations of joy

used to get hold of me, and that I used to creep into corners to think out

my thoughts by myself. I was, however, extremely timid, and easily

overawed by fear. We had a lofty nursery with a bow-window that

overlooked the river. My brother and I were constantly wondering at

this river. The coming up of the tides, and the ships, and the jolly

gangs of towers ragging them on with a monotonous song made a daily

delight for us. The washing of the water, the sunshine upon it, and

the reflections of the waves on our nursery ceiling supplied hours of talk

to us, and days of pleasure. At this time, being three years old,

... I learned my letters.... I used to think a good deal, especially about

the origin of things. People said often that they had been in this

world, that house, that nursery, before I came. I thought everything

must have begun when I did.... No doubt other children have such

thoughts, but few remember them. Indeed, nothing is more remarkable

among intelligent people than the recollections they retain of their early

childhood. A few, as I do, remember it all. Many remember

nothing whatever which occurred before they were five years old.... I have

suffered much from a feeling of shyness and reserve, and I have not been

able to do things by trying to do them. What comes to me comes of

its own accord, and almost in spite of me; and I have hardly any power

when verses are once written to make them any better.... There were

no hardships in my youth, but care was bestowed on me and my brothers and

sisters by a father and mother who were both cultivated people."

To another friend she writes:

"I suppose I may take for granted that

mine was the poetic temperament, and since there are no thrilling

incidents to relate, you may think you should like to have my views as to

what that means. I cannot tell you in an hour, or even in a day, for

it means so much. I suppose it, of its absence or presence, to make

far more difference between one person and another than any contrast of

circumstances can do. The possessor does not have it for nothing.

It isolates, particularly in childhood; it takes away some common

blessings, but then it consoles for them all."

With this poetic temperament, that saw beauty in flower, and

sky, and bird, that felt keenly all the sorrow and all the happiness of

the world about her, that wrote of life rather than art, because to live

rightly was the whole problem of human existence, with this poetic

temperament, the girl grew to womanhood in the city bordering on the sea.

Boston, at the mouth of the Witham, was once a famous

seaport, the rival of London in commercial prosperity, in the thirteenth

century. It was the site of the famous monastery of St. Botolph,

built by a pious monk in 657. The town which grew up around it was

called Botolph's town, contracted finally to Boston. From this town

Reverend John Cotton came to America, and gave the name to the capital of

Massachusetts, in which he settled. The present famous old church of

St. Botolph was founded in 1309, having a bell-tower three hundred feet

high, which supports a lantern visible at sea for forty miles.

The surrounding country is made up largely of marshes

reclaimed from the sea, which are called fens, and slightly elevated

tracts of land called moors. Here Jean Ingelow studied the green

meadows and the ever-changing ocean.

Her first book, A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and

Feelings, was published in 1850, when she was twenty, and a novel, Allerton and Dreux, in 1851; nine years later her

Tales of Orris.

But her fame came at thirty-three, when her first full book of Poems

was published in 1863. This was dedicated to a much loved brother,

George K. Ingelow:—

"YOUR LOVING SISTER

OFFERS YOU THESE POEMS, PARTLY AS

AN EXPRESSION OF HER AFFECTION, PARTLY FOR THE

PLEASURE OF CONNECTING HER EFFORT

WITH YOUR NAME."

The press everywhere gave flattering notices. A new

singer had come; not one whose life had been spent in the study of Greek

roots, simply, but one who had studied nature and humanity. She had

a message to give the world, and she gave it well. It was a message

of good cheer, of earnest purpose, of contentment and hope.

|

"What though unmarked the happy workman toil,

And break unthanked of man the stubborn clod?

It is enough, for sacred is the soil,

Dear are the hills of God.

"Far better in its place the lowliest bird

Should sing aright to him the lowliest song,

Than that a seraph strayed should take the word

And sing his glory wrong."

"But like a river, blest where'er it flows,

Be still receiving while it still bestows."

"That life

Goes best with those who take it best.

—it is well

For us to be as happy as we can!"

"Work is its own best earthly meed,

Else have we none more than the sea-born throng

Who wrought those marvellous isles that bloom afar."

|

The London press said:

"Miss Ingelow's new volume exhibits abundant evidence that

time, study, and devotion to her vocation have both elevated and welcomed

the powers of the most gifted poetess we possess, now that Elizabeth

Barrett Browning and Adelaide Proctor sing no more on earth. Lincolnshire

has claims to be considered the Arcadia of England at present, having

given birth to Mr. Tennyson and our present Lady Laureate."

The press of America was not less cordial. "Except Mrs.

Browning, Jean Ingelow is first among the women whom the world calls

poets," said the Independent.

The songs touched the popular heart, and some, set to music,

were sung at numberless firesides. Who has not heard the Sailing

beyond Seas?

|

"Methought the stars were blinking bright,

And the old brig's sails unfurled;

I said, 'I will sail to my love this night

At the other side of the world.'

I stepped aboard,—we sailed so fast,—

The sun shot up from the bourne;

But a dove that perched upon the mast

Did mourn, and mourn, and mourn.

O fair dove! O fond dove!

And dove with the white breast,

Let me alone, the dream is my own,

And my heart is full of rest.

"My love! He stood at my right hand,

His eyes were grave and sweet.

Methought he said, 'In this fair land,

O, is it thus we meet?

Ah, maid most dear, I am not here;

I have no place,—no part,—

No dwelling more by sea or shore!

But only in thy heart!'

O fair dove! O fond dove!

Till night rose over the bourne,

The dove on the mast as we sailed past,

Did mourn, and mourn, and mourn." |

Edmund Clarence Stedman, one of the ablest and fairest among American

critics, says:—

"As the voice of Mrs. Browning grew silent, the songs of

Miss Ingelow began, and had instant and merited popularity. They sprang up

suddenly and tunefully as skylarks from the daisy-spangled,

hawthorn-bordered meadows of old England, with a blitheness long unknown,

and in their idyllic underflights moved with the tenderest currents of

human life. Miss Ingelow may be termed an idyllic lyrist, her lyrical

pieces having always much idyllic beauty. High Tide, Winstanley, Songs of

Seven, and the Long White Seam are lyrical treasures, and the author

especially may be said to evince that sincerity which is poetry's most

enduring warrant."

Winstanley is especially full of pathos and action. We watch this heroic

man as he builds the lighthouse on the Eddystone rocks:—

|

"Then he and the sea began their strife,

And worked with power and might:

Whatever the man reared up by day

The sea broke down by night.

* * * * *

"A Scottish schooner made the port

The thirteenth day at e'en:

'As I am a man,' the captain cried,

'A strange sight I have seen;

"'And a strange sound heard, my masters all,

At sea, in the fog and the rain,

Like shipwrights' hammers tapping low,

Then loud, then low again.

"'And a stately house one instant showed,

Through a rift, on the vessel's lea;

What manner of creatures may be those

That build upon the sea?'" |

After the lighthouse was built, Winstanley went out again to see his

precious tower. A fearful storm came up, and the tower and its builder

went down together.

Several books have come from Miss Ingelow's pen since 1863. The following

year, Studies for Stories was published, of which the Athenæum said,

"They are prose poems, carefully meditated, and exquisitely touched in by

a teacher ready to sympathize with every joy and sorrow." The five stories

are told in simple and clear language, and without slang, to which she

heartily objects. For one so rich in imagination as Miss Ingelow, her

prose is singularly free from obscurity and florid language.

Stories told to a Child was published in 1865, and

A Story of Doom, and

Other Poems, in 1868, the principal poem being drawn from the time of the

Deluge. Mopsa the Fairy, an exquisite story, followed a year later, with

A

Sister's Bye-hours, and since that time, Off the Skelligs in 1872,

Fated

to be Free in 1875, Sarah de Berenger in 1879, Don John in 1881, and

Poems

of the Old Days and the New, recently issued. Of the latter, the poet

Stoddard says: "Beyond all the women of the Victorian era, she is the most

of an Elizabethan . . . . She has tracked the ocean journeyings of Drake,

Raleigh, and Frobisher, and others to whom the Spanish main was a second

home, the El Dorado of which Columbus and his followers dreamed in their

stormy slumbers . . . . The first of her poems in this volume, Rosamund, is a

masterly battle idyl."

Her books have had large sale, both here and in Europe. It is stated that

in this country one hundred thousand of her Poems have been sold, and half

that number of her prose works.

Miss Ingelow has not been elated by her deserved success. She has told the

world very little of herself in her books. She once wrote a friend:—

"I am

far from agreeing with you 'that it is rather too bad when we read

people's works, if they won't let us know anything about themselves.' I

consider that an author should, during life, be as much as possible,

impersonal. I never import myself into my writings, and am much better

pleased that others should feel an interest in me, and wish to know

something of me, than that they should complain of egotism."

It is said that the last of her Songs with Preludes refers to a

brother who lies buried in Australia:—

|

"I stand on the bridge where last we stood

When delicate leaves were young;

The children called us from yonder wood,

While a mated blackbird sung.

* * * * *

"But if all loved, as the few can love,

This world would seldom be well;

And who need wish, if he dwells above,

For a deep, a long death-knell?

"There are four or five, who, passing this place,

While they live will name me yet;

And when I am gone will think on my face,

And feel a kind of regret." |

With all her literary work, she does not forget to do good personally. At

one time she instituted a "copyright dinner," at her own expense, which

she thus described to a friend: "I have set up a dinner-table for the sick

poor, or rather, for such persons as are just out of the hospitals, and

are hungry, and yet not strong enough to work. We have about twelve to

dinner three times a week, and hope to continue the plan. It is such a

comfort to see the good it does. I find it one of the great pleasures of

writing, that it gives me more command of money for such purposes than

falls to the lot of most women." Again, she writes to an American friend:

"I should be much obliged to you if you would give in my name twenty-five

dollars to some charity in Boston. I should prefer such a one as does not

belong to any party in particular, such as a city infirmary or orphan

school. I do not like to draw money from your country, and give none in

charity."

Miss Ingelow is very fond of children, and herein is, perhaps, one secret

of her success. In Off the Skelligs she says:—

"Some people appear to feel

that they are much wiser, much nearer to the truth and to realities, than

they were when they were children. They think of childhood as immeasurably

beneath and behind them. I have never been able to join in such a notion. It often seems to me that we lose quite as much as we gain by our

lengthened sojourn here. I should not at all wonder if the thoughts of our

childhood, when we look back on it after the rending of this vail of our

humanity, should prove less unlike what we were intended to derive from

the teaching of life, nature, and revelation, than the thoughts of our

more sophisticated days."

Best of all, this true woman and true poet as well, like Emerson, sees and

believes in the progress of the race . . . .

|

"Still humanity grows dearer,

Being learned the more," |

. . . .

she says, in that tender poem, A Mother showing the Portrait of her Child. Blessèd optimism! that amid all the shortcomings of human nature sees the

best, lifts souls upward, and helps to make the world sunny by its

singing. |

|

____________________________

JEAN INGELOW

from

"Recollections of Fifty Years"

by

ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO

("Edward Garrett").

I met my girlhood's correspondent, Jean Ingelow, at the

Halls' house [Ed.―Mrs. S. C. Hall, née

Anna Maria

Fielding], when they were her neighbours in Holland Street. She

was a kind-looking, pleasant, middle-aged lady, with a fresh complexion

and brown hair, who cannot be better described than by saying that she

was very like her own writings. She looked a thoroughly wholesome,

practical person. Dr. Japp [Ed. ―Alexander

Japp] said to me long afterwards that she had always seemed to him the

very type of a country banker's maiden sister. In the course of our

conversation she said to me, with an air of solicitude, that she hoped I

took care that my publishers were doing me justice. She was a woman who

hated personal publicity. In advanced age, not very long before her

death, she showed some impatience towards a publisher who was anxious to

secure a new photograph of her. Something of this reserve she must have

carried into her private life, for one of her biographers has told us

that nothing was ever known of the end of her one shadowy love-affair

with a young naval officer. Long before I heard this I had written

that, whether or not it be true that every author's work is for ever

haunted by one dominant idea, we might certainly say that the paramount

note of Jean Ingelow's writing was of clinging love mysteriously

severed. Think of "Divided," of the creepy "House in the Dell," and of

the thread underlying so many of the plots of her stories.

Yet not even all Jean Ingelow's dignity and reserve could save her

from intrusive gossip. Some may remember that once it was freely

whispered that she was likely to become the second wife of Robert

Browning. There were absolutely no grounds for this rumour, which, if

it reached her, doubtless gave her pain, and is conceivably the reason

why, as her biographer puts it, "the acquaintance between the two poets

never ripened into intimacy." While the rumour was current Mrs. S. C.

Hall told me that Gerald Massey, who had felt as much admiration for the

poet as for her poems, had offered her his hand, he being then a widower

with a young family. He confided to Mrs. Hall that Jean Ingelow had

replied most kindly, but had assured him that her acceptance of his

offer was "absolutely impossible." "Now, nothing could make my offer

impossible," said he naively, "save the existence of an already-accepted

lover. Who is visiting the Ingelow' house just now? Why, Robert

Browning has been seen there! It must be he." And so the rumour

rose—an inference transformed into an assertion.

Dean Kitchin, who knew the Ingelow family in their youth, says that

he thinks "Jean" Ingelow was then but plain "Jane."

*

*

*

*

*

*

On the day when Queen Victoria went to St. Paul's to return

thanks for the Prince of Wales's recovery from dangerous illness, we

were invited to witness the procession from 56, Ludgate Hill, the

offices of Good Words and the Sunday Magazine. . . . So we

arrived in Ludgate Hill soon after St. Paul's clock struck 6 a.m. We

were not at all too soon; the street was already full, and we heard

afterwards that some of the people had taken up their positions the

night before, and had come well provided with food! . . . . With Pinwell,

the artist, and his sweet young wife we had some very pleasant talk

during those hours of waiting for the procession. Mr. Pinwell had

illustrated one or two of my stories, and some of his drawings had

delighted me by their evidence of his comprehension of my "characters,"

often a very sore point as between writer and artist. He was a

pleasant-looking, genial man, well-built, with a healthy country

complexion—the last man whom one would have thought destined to an early

grave.

Jean Ingelow was there, keenly interested to watch the crowd, and

she actually persuaded two gentlemen (Dr. Donald MacLeod was one of

them) to take her out into it, so thoroughly did she enjoy contact with

happy, homely humanity. She expressed herself as pained to see that Dr.

George Macdonald's young daughters had brought play-books with them,

which they read, instead of throwing themselves heart and soul into the

humours of the animated scene before them.

|

|

____________________________

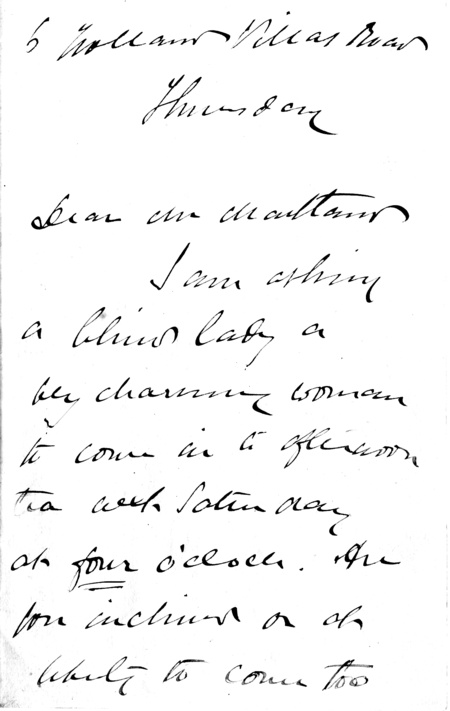

So far as I can tell, Jean's note reads as follows . . .

|

5 Holland Villas Road

Thursday

Dear Mr Maitland

I am asking a blind lady a very charming woman to come in to

afternoon tea Saturday at four o'clock. Are you

inclined or at liberty to come too.

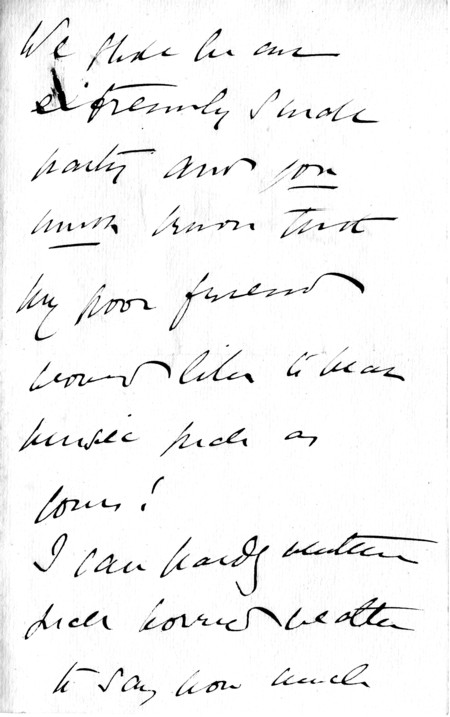

We shall be an extremely small party and you must know that

my poor friend would like to hear music such as yours!

I can hardly mention such horrid weather to say how much

pleased I should be to have your mother also & Mrs

Maitland but if the weather is tolerable tomorrow I shall

if possible come & ask her personally.

Very sincerely yours

Jean Ingelow

ED.―if

you can offer other suggestions for the final paragraph, I

would be pleased to hear from you. |

|

|

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)