MRS. ISA

CRAIG-KNOX

"Isa Craig"

(1831-1903)

Victorian social reformer, women's rights activist,

journalist, poetess and novelist.

――――♦――――

|

". . . . Here is a human being sunk to the lips in sin and

suffering, unable to extricate herself, haunted by thoughts of

self-destruction. Let her alone: cold, hunger, and disease

will soon put an end to her sufferings; or in the kindly

December darkness, she may drop into the murky Thames.

This, perhaps, is the 'cold-blooded economical' way of disposing

of the case. . . ."

From....Emigration as

a Preventive Agency

A paper by Isa Craig, 1858. |

". . . . To be told that you are not wanted, that in the

great busy world there is no need for you, that you and yours

might perish unregarded, and never be missed out of the

multitude, must be a bitter experience, and yet it is a common

one; alas! so very common. "

From....Peggy Oglivie's

Inheritance

A novel by Isa Craig. |

|

" . . . . Under the wing of a national school in Dublin

there is a ragged school of a kind which appears to meet the necessities

of the case . . . . . to secure regular attendance it is found necessary

to furnish the first meal of the day, a simple piece of bread, as the

children are often kept at home till it can be earned or begged, so

entire is the destitution of their homes."

From . . . .

Education in Ireland

A paper by Isa Craig, 1861. |

|

"I have simply expressed the thoughts and feelings

suggested by nature and the scenes of life in the tone and language that

came at their command. Recognising in poetry an art to be

cultivated with enthusiasm for its own sake, as well as the sake of the

refined enjoyment which its exercise bestows, I have aspired as far as

possible to render these poems artistic efforts."

Isa Craig. |

|

"Girls must marry," she said, "especially girls who have

nothing. What else can they do? They are a burden on

their friends, that's all, and discontented with their lot; and

they can't pick and choose like a man. They must wait for

an offer, and it's not every girl who has more chances than one.

They can't afford to throw away a good one."

A Victorian woman's view on marriage, from . . .

. Heroine of Home

A novel by Isa Craig. |

――――♦――――

ISABELLA CRAIG, the only child of John Craig, a Scottish hosier and glover, was born in

Edinburgh on October 17, 1831. Following the death of her parents

while she was still a child, Isa lived with her grandmother, attending

school until 1840―there is a suggestion

in some contemporary publications that she may have contributed to the family income

by needle-work. In 1853, Isa secured a

position on the staff of The Scotsman, writing

literary reviews and articles on social questions; she had already from

an early age contributed poems (signed

either "Isa"

or "C.") to The Scotsman and to various periodicals, and in 1856

her first volume of poems ("Poems by Isa")

was published by Blackwood of Edinburgh.

|

THE violet in thy shade all meekly lies,

And spends its hidden life in sweet perfume,

Till, meekly shutting up its dying eyes,

It yields to fresher buds a space to bloom.

The apple stands not on the wind-swept hill,

Where storms may toss its branches to and fro,

And nip its blossoms with untimely chill,

In their first crimson flush, ere pale they grow,

To their white death; but in the vale it dwells,

Spreading its cloud of bloom, delicious show!

And golden green and ruddy fruitage swells,

Till heavy hangs the richly-laden bough:

And thus within the heart that lieth low,

The fruits of love to all their fulness grow.

ISA CRAIG |

In 1856 Isa met Elizabeth ("Bessie")

Rayner Parkes (1829–1925)―a campaigner for women's

rights, journalist, poetess and author―the pair contributing to a Glasgow women's

periodical, the Waverley Journal. Bessie, who became its Editor

in April 1857, advertised the paper as "a working woman's journal" and

later established an office in Princes Street, London, where Isa

assisted her.

|

HE

WAVERLEY. A Working-Woman's Journal; devoted to the legal and

industrial interests of women. Edited by Bessie Rayner Parkes.

Published fortnightly. Price 4p. To be had from the

office, 14A, Princes Street, Cavendish

Square; and from Tweedie, 337, Strand. Also at 147, Fleet

Street.

|

_______________

An advertisement appearing in G. J. Holyoake's

'The Reasoner', 28 October, 1857. |

|

In 1857 Isa moved to London where she took up an

appointment as Assistant Secretary of the "National Association for the

Promotion of Social Science" (NAPSS); the Secretary was

barrister G. W. Hastings, son of Dr. Sir Charles Hastings, founder of

what was to become the British Medical Association.

The

English Woman's Journal

strongly supported both NAPSS and the new

"Ladies' Sanitary Association", founded by NAPSS to carry 'a social and

sanitary crusade' into the homes of the poor. Between 1857 and its

final conference in 1884, NAPSS served as a forum for discussion on

Victorian social questions (approximately five thousand papers were

delivered to the Association, published in nearly fifty volumes) and

acted as an influential adviser to governments. It attracted many

powerful contributors, including politicians, civil servants, the first

British feminists, intellectuals (such as John Stuart

Mill, John Ruskin, F. D. Maurice and Charles Kingsley) and

reformers, and influenced policy and legislation on matters as diverse

as public health and women’s legal and social emancipation.

Mary Carpenter, famous for her work with ragged and

criminal children, reputedly became the first woman to speak in public

in Britain when she addressed the Association’s

inaugural congress in

Birmingham in October 1857.

|

The

Times

1st February 1859

Advertisement.—Isa Craig and "The English Woman's

Journal."—The new number of "The English Woman's Journal" for

February 1 contains a new poem by Isa Craig, "The

Ballad of the Brides of Quair." Miss Craig has been a

regular contributor to "The English Woman's Journal" since its

commencement in March, 1858. Readers will find her full

signature in the numbers of June and January to a poem and a prose

article. Published by "The English Woman's Journal" Company,

limited, at their office, 14a, Princes-street, Cavendish-square,

W., and by Piper and Co., Paternoster-row. Price, 1s. |

The Waverley Journal had

ceased publication by 1858, but it was soon followed by the English Woman's Journal,

which was

supported by other committed independent women among whom were Matilda

Mary Hays (1820?–1897: novelist,

translator of George Sand and the Journal's co-editor);

Adelaide Anne Procter

(1826-64: poetess and women's activist);

Emily

Faithfull (1835-95: publisher, lecturer and

women's activist; a Surrey rector's daughter, Emily later founded the Victoria Press where she trained

young working-class women as compositors); and Maria

Susan Rye (1829–1903) social reformer,

promoter of emigration and briefly Secretary of the committee to

reform the law on married women's property, who was especially

interested in finding work for educated middle-class women. Maria

established an office to copy legal documents in Lincolns Inn Fields,

and was a founder of the "Female Middle-Class Emigration Society"

(in her "Recollections",

Isabella Fyvie Mayo describes

Maria as "a tall lady, severe of aspect and speech.") Sarah Lewin was employed as secretary and bookkeeper. In December

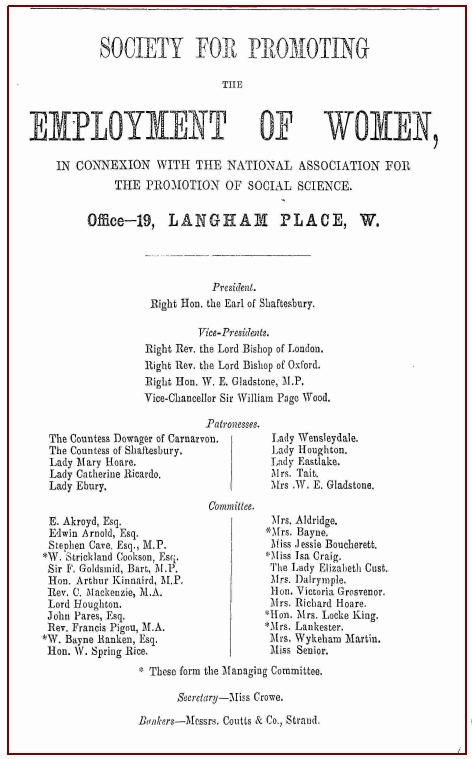

1859, the Journal moved to more spacious premises at 19, Langham

Place, where a reading room and coffee shop were provided, and

associated societies could meet to develop initiatives.

|

The

Times

18th November 1859

EMPLOYMENT OF WOMEN.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir,—As

you have called public attention to the subject of the

employment of women, I beg to inform you that at a meeting of

the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science

yesterday it was moved by Mr. G. W. Hastings, and seconded by

the Hon. Arthur Kinnaird, M.P., and carried,—

"That the following be

appointed a committee to consider and report to the council on

the best means which the association can adopt to assist and

present movement for increasing the industrial employment of

women—the Right Hon. the Earl of Shaftesbury, the Hon. A.

Kinnaird, M.P., Mr. E. Ackroyd, Mr. Hastings, Miss Adelaide

Proctor, Miss Boucherette, Miss Faithfull, Miss Craig."

If you will kindly

insert this letter in your columns it will greatly facilitate

the object of the committee, which is to obtain information as

to the channels already open to female industry, and as to the

opening of others into which it would be desirable to direct

it. As secretary to the committee, I shall be happy to

receive any communications on the subject, and am, Sir, yours

obediently,

ISA CRAIG.

3, Waterloo-place, Pall-mall, S.W., Nov.

17. |

|

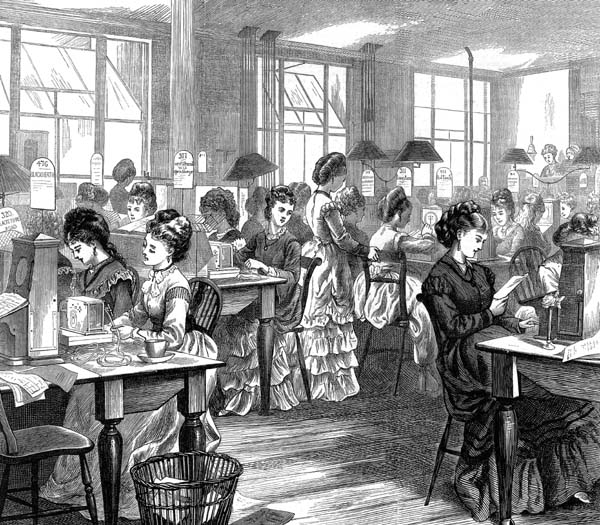

In 1860, Maria Rye established the Telegraph

School for Women at 6 Great Coram Street, London, one of

several organisations she established to further female employment.

Rye had previously published ‘The Rise and Progress of the

Telegraphs’ in 1859. Isa Craig served as the school's

Secretary.

The major theme of the English Woman's Journal was employment, and associated with it

were the needs to improve the education of women of all classes and the

social responsibilities of middle-class women for working-class women.

These concerns raised the issue of the appropriate division of labour

between men and women and the extent to which these feminists supported

the employment of married women. Questions about class and status

were also significant. Women who sought employment seemed too

often constrained by notions of gentility and the appropriateness of

employment for a 'lady' . . . .

'EMPLOYMENT FOR WOMEN,—Miss Isa Craig addresses the following as a

letter to the Times :—

"The cause of

working-women has found an able and generous advocate in 'S.G.O.' [Ed.―letter

below]. He touches the heart of the question when he

maintains that in securing her independence the dignity of woman is

deeply concerned. The power of independent industry, which

saves her from a mercenary marriage, renders her equally free to

serve the needs of the world, or to become the fit and noble

helpmate of a working man—and in these days, what Englishman is not

a worker by hand or brain? Brave champion that we have found

in 'S.G.O.,' we have—I do not mean to be strictly statistical—five

million good as he. We have the great body of the respectable

working-classes, as our manual workers are distinctly called, whose

sisters and daughters are independent labourers in many branches of

non-domestic industry; we hope the time is coming when they will see

their true interests, and withdraw their wives from the labour

market. But among them, closer to the heart of nature, coming

in contact with the great human needs of soul and body in their

simplest forms, the 'communion of labour' may often be found in its

highest possible perfection. Then we have the large

lower-middle class, whose husbands and fathers know the value of

their womankind as clerks and shopkeepers, limited as their

education has been. Higher in the social scale, cultivated men

seek eagerly the help and companionship of cultivated women.

It seems therefore, that the views of your correspondent must be

mistaken, or must be held by only a very limited class of society,

whose opinions cannot deserve notice. These 'lords of

creation,' these despisers of women, are not many among 'those who

hold their heads high' in honourable manhood.

Miss

Faithful, Miss Rye, Miss Bessie Parkes, will tell of the respectful

kindness, the generous aid of the men with whom they have come in

contact. And why? They have asked help, not declared

war. They have owned that women can co-operate, but never can

and never ought to compete with man. If the woman's cause is

the man's, so are the woman's difficulties. The problem of one

is the problem of both. And this of the social and industrial

position of women can only be solved by both working hopefully and

helpfully together, holding one another in mutual honour and

esteem. The National Association for

the Promotion of Social Science originated much of the

discussion on this subject, which has been carried on so ably in

your columns. Many of the schemes of female employment now

attracting public attention had their origins in its committee;

among them that of printing pursued by Miss Faithful, and that of

law copying, which Miss Rye, in addition to her labours in the cause

of emigration, carries out in her office in Portugal Street,

Lincoln's Inn. The meeting of the Association in London in

June will afford a further and fitting opportunity for the

discussion of the question, which will be introduced by papers from

several of the ladies engaged in the practical working of the plans

which former discussions originated.

I am, Sir,

yours faithfully,

ISA CRAIG, Assistant-Secretary to the

National

Association for the Promotion of Social

Science.

3, Waterloo-place, Pall-mall, S.W., April 29

[1862]" ' Matilda Hays comments on Isa's letter ― TO THE EDITOR OF THE DAILY NEWS.

(5th MAY, 1862.)

SIR,―The following letter was addressed

by me to the Times on May 1. As it has not appeared I shall be much

obliged if you will give it the benefit of your circulation.

"TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

"Sir,―Your correspondent, Miss Isa

Craig, says most truly that 'woman's cause is man's;' but not I think

equally truly, that to 'man's advocacy' it should be left, unless,

indeed, that advocacy has always shown itself so manly as that of 'S.G.O.'

"Again, Miss Craig says, 'that woman never can, or ought to compete with

man;' and here again I cordially join issue. Nature, in making man

and woman so unlike in their very likeness, has herself affixed the

power and limit of both, and so entirely do I hold this, that I believe

that when women shall become an acknowledged power in the world, as well

as in the home, taking their share in the world's work and progress,

man, in place of competitors, will find their labours of head and heart

supplemented and perfected to a degree yet undreamt of. Society

will become purified, and many of the worst evils under which we (men

and women) now labour and groan, will disappear in the recognition of a

power hitherto denied or held in abeyance, and which I, for one, cannot

believe the Almighty to have bestowed in vain.

"As a fellow-labourer with the ladies who Miss Craig mentions, I too can

and do testify to 'the respectful kindness, the generous aid of the men

with whom we have come in contact,' while personally I can and do

gratefully testify to the friendship of many good and noble men.

"But these are not the men who talk and write of 'our women' with covert

sneer and ribaldry, from which 'generous' men, as well as women, turn

with disgust.

"May the 'five million good as S.G.O.' rally round us, and with hand and

voice help the good work which, neither in my thought nor Miss Craig's,

is to further separate the sexes, (a separation to whatever extent it

exists, be it remembered, brought about by men and not by women), but

may render man and women the helpmates God intended then to be.―I

am, &c.

"MATILDA

M. HAYS."

London, May 3.

|

|

|

Bessie Raynor Parkes

(1829-1925) |

A commentator writing in the

Scotsman had this to say about the English Woman's Journal...."It has all along been distinguished, and

continues to be so, by a lady-like good taste and sense, which

preserve if from offensive manifestations of 'strong-mindedness' on

the one hand, and an earnestness and definiteness of purpose raising

it above the frivolity of crotchet and fashions on the

other." Alas, lack of frivolity was to contribute to the

Journal's downfall. Writing to

Barbara Bodichon in December 1862, the Journal's Editor, Emily Davies, believed

that the Journal would never have a

'very large circulation', but that the inclusion of 'a good tale'

would help attract the public, while the 'solid matter' would help

keep it 'special.' But the Journal

failed to win a viable circulation, and by 1862 its financial future

had become uncertain. It struggled on, but with internal

disagreements among its members adding to its problems it closed

eventually in 1864. Bessie Parkes went on to start the Alexandra Magazine, but it too failed and,

following her marriage to Louis Belloc, she gradually withdrew from

feminist activities. Bessie died in 1925; her son was the

writer Hilaire Belloc [Ed. see also Bessie's

poem The Mersey and the

Irwell]. The Journal,

however, did live on. In 1866 it was revived by Jessie

Boucherett, who renamed it the Englishwoman's Review, and in this form it

continued in publication until 1910.

In her role as Assistant

Secretary to NAPSS, Isa epitomised the independent single

woman of her age. Nevertheless, and perhaps unsurprisingly

considering her background, she does appear to have been daunted by the

magnitude of her task, in its early years at least. In a letter

dated September 1860 with regard to a forthcoming conference at Glasgow,

she writes thus: "I hope I shall not break down at Glasgow. I like

the work, but I tremble at the meetings. I begin to feel that I

must be doomed to go through them, for some evil done in a previous

state of existence" [and from the same letter: "I like to see our

Social Science men advanced for they are bound to advance Social

Science"]. But this was an age in which women

played essential but supporting roles, and regardless of what her

feelings might have been about her work for NAPSS, when Isa married her cousin John

Knox in 1866 she retired from paid employment. Her marriage

announcement in the Pall Mall Gazette (19 May, 1866) stated

simply―

Knox―Craig―At

St. John's, Lewisham, Mr. J. Knox to Miss Isa Craig, 17th inst.

|

"Just let any one work out the problem of

keeping eleven souls in London on twenty-one shillings a week.

Take four shillings for rent, and one shilling and sixpence for

fire, light, and such indispensable articles as soap, &c., and

fifteen and sixpence remains—that is, one shilling and fivepence

to feed and clothe each. Give each a pound of bread a day,

and the father two—bread being their staple food—and the sum

that remains is five shillings. A shilling's worth of

potatoes be used weekly; another shilling will go for tea,

sugar, and coffee for the father and mother, and very poor stuff

it will be; sixpence for milk for the infants, sixpence for the

dripping for the bread and potatoes of the elder children; two

shillings for bacon and cheese for the father, and a little

meat, now and then, for the nursing mother. There is not

one shilling left, and all have to be clad, and one or two kept

at school; and there is nothing but dripping for the children's

bread, and they cannot live in health without something more and

something else. The addition of a pennyworth of sprats for

dinner makes the little ones jump for joy. Of course the

infants do not use a pound of bread, but the growing boys and

girls make up for this."

Isa Craig on working-class economics: from . . .

.

Round the Court. |

The witnesses included Hastings, Bessie Raynor Parkes, Emily Davis

and Jane Crow. It was reported widely in the press that―

|

Miss Isa Craig, having yielded her position of

Assistant-Secretary of the Social Science Association, to

practise social science in a new capacity―to

study practically, in fact, the law of marriage―a

number of the members subscribed and have presented to her a

silver tea service and salver, as a wedding present. The

inscription on the salver is: "To Isa Craig, from her

grateful and attached friends of the National Social Science

Association, 17th May, 1866."

|

――――♦――――

|

The

Times

23rd July 1860

TO THE EDITOR OF

THE TIMES.

Sir,—The assistance the movement "for

promoting the employment of women" has received from you

induces me to ask you to insert this letter in The Times, as I think many will be

glad to hear, so great is the success of this office, that I

have more work at this moment than my 12 women compositors can

undertake, and I shall therefore be glad to receive six or

eight girls immediately. They must be under 16 years of age,

and apply personally at my office next week.

Your

very truly,

EMILY

FAITHFULL.

The Victoria Press, 9, Great

Corum-street, July 21.

The

Victoria

Press |

――――♦――――

Notice appearing in the Alexandria Magazine,

May 1st, 1864.

――――♦――――

ISA

CRAIG'S LITERARY

LIFE.

Largely self-educated in literature, Isa was an admired poet in

her day, first attracting fame as the winner of the

Robert Burns

Centenary Competition at The Crystal Palace in 1858 in the face

of over 600 entrants, including some strong competition (among the

finalists were Frederick Myers, Arthur J. Munby, and J. Stanyan

Bigg; Gerald Massey's entry, "A Centenary Song", was placed fourth,

while among those unplaced was a respectable poem ― "Robert

Burns: A Centenary Ode" ― by the Scots

"Pedlar Poet", James Macfarlan).

The Scotsman for 27th January 1859

carried the following report of the Burns Centenary event — and the non-appearance of Miss Craig to receive

her 50 guineas prize! .....

|

LONDON.

At the

Crystal Palace, the Burns Centenary was celebrated on Tuesday

with much enthusiasm. Upwards of 14,000 persons were

present during the day. There was a grand concert and

great interest was imputed to the proceedings by the unveiling

of Calder Marshall's bust of Burns, and the exhibition of a

number of relics of the poet. The recitation of the prize

poem, however, was the chief attraction, and at three o'clock

the scene from nave to transept, and orchestra to orchestra,

and gallery to gallery, presented an imposing amphitheatre of

listeners riveted to the spot, until Mr Phelps appeared upon

the platform and enjoined silence. He opened the

envelope with the mottos of the author of the successful poem,

and announced it to be "Isa Craig, Ranelagh Street,

Pimlico." He then recited the poem with much taste and

elocutionary power. The Morning

Herald, in noticing this stage of the proceedings,

says:—"At the close of the recitation of the poem by Mr

Phelps, a proclamatory placard was hoisted over the orchestra,

the name of the successful competitor not having been caught

by multitudes around, with the inscription in large black

rubrics on a white ground of 'The author of the poem is Ian

Craig.' Calls then arose for Isa Craig to come before

the scenes, and multitudinous and mysterious were the

conjectures indulged in by the bystanders as to who Isa Craig

could really be. Some suggested that it was a mistake

for 'Ailsa Craig;' others read it Esau Craig; while many

pronounced the whole affair to be a mystery and a myth, seeing

that the fortunate prizeholder did not make her appearance to

be complimented. The crowd indulged in these dreamy

disquisitions and conjectures until the scene and the subject

were altogether changed by the striking up of the band for the

supplemental concert. From all that we could ascertain,

however, from the most reliable sources, we find that Isa

Craig is a young Scots lady, and that the mysterious

monosyllable 'Isa' is a breviate or nomme de plume for Isabella; that

she belongs to the single sisterhood, and has been a

contributor to Chambers' Journal,

the Scotsman, and the Englishwomen's Magazine, and is said

to have published a small volume of poems. From feelings

either of timidity or poetical delicacy and pride, Miss Craig

neither came before the curtain, nor did she pay a visit to

the Company's treasury to receive the fifty guineas, although

the check had been waiting for her acceptance all day.

Speaking of the prize poem and its author, the Morning Star says:— "speculation has

been rife as to who was the author of the above very beautiful

composition, and the name of more than one distinguished

person has been confidently mentioned. There is even now

a shrewd suspicion that 'Isa Craig' hides a name much less

obscure."

――――♦――――

THE

TIMES

27th January 1859

THE BURNS PRIZE ODE.

Miss

Craig, the successful competitor for prize and poetical

distinction, is a young Scotchwoman,—a native of Edinburgh,

and for two years past resident in London. Early left an

orphan, she was reared and educated under the care of a

grandmother not in affluent circumstances. With

praiseworthy industry and, and self cultivation of her

intellectual powers, she early resolved to work out her own

pecuniary independence. By occasional poetical

contributions to the Edinburgh Scotsman she gained the notice and

kindness of Mr. John Ritchie, the oldest and principal

proprietor of that journal, and for some years she was

employed by this early patron and friend in its literary

department. In 1856 Messrs. Blackwood published in a small

volume a collection of Miss Craig's fugitive metrical

compositions, under the title Poems by

Isa. The author has also been a contributor under

the signature "O." to the poetry of the National Magazine. In August,

1857, on Miss Craig's first visit to a London friend, Mr.

Hastings, the hon. secretary of the national Association of

Social Science, engaged her services in the organization of

the society, and to this association Miss Craig is still

attached as a literary assistant. The published

transactions of the association owe much to her talent and

good judgement. At the Liverpool meeting in October

last, Miss Craig attracted general notice and commendation by

her unobtrusive conduct and tack in the management of some

departments of the business. Miss Craig was absent at

the Crystal Palace meeting, really ignorant of the success of

her literary competition, and of the award of the

judges. It had happened that she had not seen the

mottoes on the successful poem made available some days

since. The chances of a young Scotchwoman against 621

male and female competitors did not tempt her to attend the

adjudication, and she was not informed of her success till

late after the termination of the meeting at Sydenham

Palace.

――――♦―――― |

|

FAIR valley, clothed with richest,

freshest green,

While parched are all

the world's wide ways beside,

Thine is

the shady spot, the verdant screen,

The gentle banks where quiet waters

glide.

'Tis sweet to wander in thy

narrow ways,

Too narrow for the

chariot-wheels of pride;

'Tis sweet to

shelter from the noontide rays,

Where

all unsunned thy cool-eyed flowerets hide:

To feed thy stream flows many a tinkling

rill,

Hastening with tribute it may

not refuse.

With gushing crystal thus

its founts to fill,

The thirsty

heights are drained of all their dews;

And thus into the heart that

lieth low,

The purest streams of

highest wisdom flow.

ISA CRAIG

|

In 1863, during the height of the

American Civil War, cotton exports to the cotton-processing towns of

Lancashire were disrupted, resulting in factory closures and great

hardship among the working populace of the area. To help raise

money to alleviate their hardship, Isa undertook to compile and edit

a volume of verse containing contributions from notable poets of the

day, among whom was Christina Rossetti . . . .

|

45

Upper Albany St. N.W.

Thursday, 13th

November. [1862]

Madam

Mme. Bodichon, asking me to contribute a

little piece to the volume to be sold at the Lancashire

Distress exhibition, told me that you had kindly undertaken to

see the edition through the press. I therefore, though

unknown to you, take the liberty of directing my Royal Princess to your hands,

trusting that so I am in accord with your wishes. If R.P. is too long, I have by me plenty

of shorter pieces, though none I fear on so appropriate a

theme. May I ask you to favour me by forwarding to me

the proof of my piece as I am desirous to correct it myself,

thinking that so fewer errors are likely to creep in.

As I know not what

poets are on your list, nor how many may be wished for,

perhaps I had better say that if you would like a piece from

the pen of C.B. Cayley the translator of Dante, I think it

possible I might be able to procure one for the volume as Mr

Cayley is our old friend. But of course I cannot promise

that he would do us such a favour. I only think it is

not impossible.

With hearty wishes for a blessing on our common cause, permit

me, Madam, to remain

Yours

faithfully

Christina G. Rossetti. |

The result was a charming volume, Poems: an offering to

Lancashire . . . .

|

Just

ready.

OEMS:

An Offering to Lancashire. By CHRISTINA ROSSETTI, GEORGE

MACDONALD, "V.", W. B. SCOTT, R. MONKTON MILNES, MARY HOWITT,

"G.E.M.", W. ALLINGHAM, ISA CRAIG, and others. Price 3s.

6d. Printed and published for the Art Exhibition for the

Relief of Distress in the Cotton Districts. Emily

Faithfull, printer and publisher in ordinary to Her Majesty,

Victoria Press offices, 83A Farrington-street, E.C. and 9,

Great Coram-street, W.C.

From The Times, December 24, 1862. |

|

HARD is the lot of the worker:

His heart had need be brave,

With death in life to wrestle

From the cradle to the grave.

Sternly the sorrows meet him

In the thick of the mortal fray—

But the night must serve for weeping—

Work must be done by

day.

From....Brothers |

There the dying soldier lay,

Pillowed on the bloody clay;

As the battle thunder pealed,

Earth seemed sinking 'neath his head,

And the skies above him reeled,

As his bosom bled.

They died at Alma

in the fight—

Mournful Alma!

From....They Died at Alma |

Following her marriage in 1866, what little can

be gleaned about the remainder of Isa's literary career comes from

several short newspaper articles, from Cassell's newspaper

advertising (their reluctance to credit authors in their advertising

makes attribution difficult) and from a search through the

periodicals of the period.

Between 1865 and 1867 Isa is reported to have edited

The Argosy, a monthly

magazine "of tales, travels, essays and poems."

Because the record of Isa's later life is

sparsely populated with fact, one is tempted to speculate; here,

perusal of the Index to the 1866 collected edition of The

Argosy suggests who her literary acquaintances might have been. Besides

her friend of the Langham Place Group, Bessie Rayner Parkes, it is unsurprising to find listed many well-known

literary women of the period ―

Jean Ingelow, Christina Rossetti, Margaret Oliphant,

Matilda Betham-Edwards, Menella

Smedley

and Marguerite Agnes Power. Among the male

contributors are William Allingham, Anthony Trollop, and fellow

Scots Alexander Smith (see Isa's

memorial essay), George MacDonald and Robert Buchanan.

But Isa's tenure at The Argosy was short-lived. During 1866 the

magazine's reputation was damaged by the serialisation of Charles

Reade’s sexually frank tale of bigamy, "Griffith

Gaunt". Its strait-laced publisher, Alexander Strahan,

horrified by the backlash, sold the magazine to Mrs

Henry Ellen Wood in October

1867, and she conducted it successfully until her death in 1887 when

her son took over. The Argosy ceased publication in

1901.

Following her brief

tenure as The Argosy's editor, Isa continued to write for the

periodicals of the age, including Good Words, The Sunday Magazine and, in

particular, The Quiver, a pious monthly periodical from the Cassell

stable intended "For Sunday and General Reading".

However, Isa's work is difficult to identify due to magazine (and

sometimes book) publishers of

the period often attributing only 'indirect' reference to authorship by

citing others of the author's published titles ― for example,

the hardback edition of Deepdale Vicarage, a story originally

serialized in The Quiver (1866-7), is attributed "by the author

of Mark Warren" rather than to its author, Mary Kirby ―

and on occasions the publisher gives no attribution whatever.

|

"The court stood at the back of a leading thoroughfare—a long, ugly

street, with rather high houses, and shops on the ground floors.

Every third shop sold something eatable, and nearly every sixth

appeared to be a drinking-shop. Behind the thoroughfare there were

acres of crowded dwellings, studded thickly with workshops and small

factories. In front of it, shutting it in, was a pawnbroker's on the

one side and a tobacconist's on the other. The houses within had no

outlook except into the court itself. They were built back to back,

a perfect contrivance for the exclusion of air and the manufacture

of fever. At the foot rose a high dead wall, and in one corner was

the general dustbin, redolent in summer of fearful odours."

A description of the Court . . . . from

Round

the Court. |

In Isa's case, two of her serialized stories from

The Quiver ―

Peggy Ogilvie's Inheritance (serialized in The Quiver, 1867-8) and

Esther West (serialized

in The

Quiver, 1868-9, and attributed to "THE AUTHOR

OF PEGGY OGLIVIE'S

INHERITANCE")― subsequently

found their way into hardback editions, both

being attributed by the publisher to Isa Craig-Knox (by 1891,

Esther West had reached its ninth edition and is again in print). There is

a reference on the title page of the former to the author also having written

Round the Court, a

series of scenes of Victorian domestic working-class life

(serialized in The

Quiver, 1867), which Cassells attribute thus: "BY

A RENT-COLLECTOR".

In similar vein Cassells attribute A Heroine of the Home

(serialized in The Quiver, 1880) to "THE

AUTHOR OF 'ESTHER

WEST', 'PEGGY OGLIVIE'S

INHERITANCE,' ETC."

which, by reference to the hardback editions of these stories,

translates to Isa Craig (this, incidentally, appears to be Isa's

last published story). In contrast, Cassells do attribute

Fanny's Fortune, (The Quiver,

1874) to Isa Craig-Knox, additionally referring in this story's title

line to the author having written "Two Years" (The

Quiver, 1870—attributed to "the author of Esther West,

etc. etc"). Thus, one proceeds in ferreting

out Isa's literary contributions to the periodicals of her day.

|

". . . . they are not criminals, and

they are not paupers. They have a wholesome

horror of the workhouse and the prison, and of the former even more

than the latter. They may not, at first sight, appear so interesting

as convicts and casuals; but then people know all about convicts and

casuals — and they know little or nothing about honest working

people. They would not make so many mistakes about them if

they did know them . . . . not that I uphold their

thriftless ways and drinking customs, they are the ruin in

of them; but it is only fair to show how hard their battle

is to keep sober, and before the world. They have to

struggle, not with poverty only, but with sickness, and

weakness, and weariness, and 'bad times,' and 'knocking

about;' and, at the root of all, with ignorance and want of

guidance. . . . In the true sense of the word "respectable,"

many of the poorest of the poor are respectable in the

highest degree . . . ."

The Court—a description of its tenants . . .

from

Round the Court. |

I doubt that other titles attributed to Isa Craig in the "COPAC

National, Academic, and Specialist Library Catalogue" are

correct; these are Mark Warren,

Deepdale

Vicarage, In Duty Bound and Hold Fast By Your Sunday. In her

autobiography "Leaflets from My Life: A Narrative Autobiography"

(1888), Mary Kirkby claims authorship of these titles (some written

jointly with her sister Elizabeth) describing

briefly the circumstances in which they were written for The

Quiver magazine. In the case of Hold Fast By Your Sundays,

other evidence which links this title to the Kirby sisters is (a) a reference on the

title page to the author having written "Margaret's Choice",

another title claimed in Mary Kirby's autobiography; and (b)

reference in the book's Introduction, written in 1889, to the

author's death ― Isa Craig died in 1903―which leads me to suspect that the author

of this title is most likely Elizabeth Kirby.

Outside of her writing for the periodicals, Isa published

three volumes of poetry: Poems by

Isa (1856); Duchess

Agnes, a Drama, and Other Poems (1864, which includes a

drama ― see

Gerald Massey in the Athenæum);

and Songs of Consolation (1874).

I have collected others of Isa's poems that do not appear within her

published collections under Poems: a

miscellany. Her educational books, Little Folk's History of England

(1871); Tales on The Parables (1872:

the second series here reproduced);

and Easy History for Upper Standards (1885) were popular

during her life.

Why Isa's literary life should have come to a

close at a comparatively early age is a mystery. Apart from Easy History for Upper Standards

(an adaption of her earlier Little Folk's History of England)

referred to, after 1880 I can find no further newspaper advertising

of her poetry and serialized stories in the Quiver or in

other periodicals, and nothing further is listed in the British

Library catalogue.

Isa's private life is also a mystery. I have been

unable to trace her entry in the 1871 Census,

but that for 1881 records her living with her husband, John Knox

(age 42, "Iron Merchant/Monger") and daughter Margaret (age 11,

"Scholar") at 13,

South Hill Park, Hampstead; resident with her are her brother-in-law,

William C. Knox (age 43, "Book Keeper/Clerk, iron-trade") and

Angelina E. Smith (age 18, "General Servant").

The 1891

Census records the same household, but having removed to 88 Breakspears Road, Brockley, Deptford.

And in 1901, the Knox family were living at

the same address, now with their daughter (aged 31), Mary E.

Parkinson (aged 32, described as a "visitor" ), and two servants;

and it was here that Isa Craig-Knox died on 23rd December,

1903. |

According to Google Streetview, 88 Breakspears Road.

|

The Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography describes her thus: "A sparkling, happy-go-lucky

person, Isa was loved by all who knew her." A contemporary edition

of the Morning Post had this to say . . . .

"The world of

letters has just lost an interesting figure in the person of Mrs Isa

Craig-Knox, who passed away at her residence at Brockley on

Wednesday, in her seventy-third year. In competition with six

hundred and twenty rivals she won the prize which was offered in

connection with the Burns centenary for the best ode to the

poet. Mrs Knox published several volumes of poems and many

popular novels. She also wrote some children's books

and, in addition to the literary work which she did for the Scotsman for many years, contributed to

most of the principal magazines. In 1857 she left Scotland for

London in order to assist Mr Hastings in organising the National

Association for the Promotion of Social Science, and she acted as

his secretary and literary assistant until her marriage with her

cousin, Mr John Knox, a descendant of the great reformer."

Following her death, Isa's husband remained at

their home in Breakspears Road where he died on 19th August, 1921, aged

82 years. I have been unable to trace what became of Isa's daughter,

Margaret.

In 1892, Isa's former overlord at NAPSS, G. W.

Hastings, by then the Liberal Unionist Member of Parliament for

Worcestershire East ― and perceived to be a vastly respectable figure

― experienced the rare and dubious distinction of expulsion from the

House of Commons following his conviction for fraud. As a Trustee for property under the will of

one John

Brown, Hastings had appropriated to himself over £20,000 from the

estate. He was jailed for five years. Following his release he published "A Vindication of

Warren Hastings", his famous ancestor who was impeached in 1787 for

corruption, although in his case he was later acquitted.

|

|

"BLOW BREEZE OF

SPRING."

A song.

Words by Isa Craig set to music by

Florence Gilbert. |

|

Sheet

music

(.pdf, 164KB) |

Midi

(.mid, 10KB) |

|

"BEAUTIFUL

SNOW"

A song.

Words by Isa Craig set to music by John

Blockley.

Sheet

music

(.pdf,

3MB) |

――――♦――――

|

KEAT'S SONNET "TO AILSA CRAIG"

ALTERED TO

SUIT A RECENT OCCASION.

To Isa

Craig. |

|

Hearken, thou lady-poet Candidate!

Give answer with thy pen,

the land-fowl's wing,

When were they musings prompted first to sing?

Where, from the sun, was thy gift hid till

late?

How long is't since the mighty power,

Fate,

Bade thee to print

thy fancy's pondering?

Slept it in scraps asunder, wandering,

Or

where the desk its papers congregate?

Thou answer'st not, for thou art modest,

maid!

They life consists

of two contrasted ways,—

The last in light,

the former in shade;

First with thy hopes, last with the people's

praise,—

Veil'd wast till occasion thee

display'd,

And crown'd thee evermore with

laurel bays.

MARY

COWDEN CLARKE

Nice, February 9, 1859.

|

――――♦――――

|

SPRING.

A

SONNET.

I LOVE the spring, although her changeful

skies

Weep oftener than smile—a child in

tears,

With a smile lurking in her glad blue

eyes;

And on her brow a coronal appears

Of fair and dewy flowers—the primrose pale,

And crocus bud of purple, white, and gold,—

While woodland voices all her coming hail,

And at her touch the cradled leaves unfold.

I love the spring-time for the lengthening

light

And coming beauty. 'Tis

like childhood's hours,

When life is all

before us stretching bright,

And full with

promise of its summer flowers,—

When tears

are soonest shed and soonest dried,

And love

hath no disguise, and beauty hath no pride.

ISA CRAIG |

――――♦――――

|

SISTERS, HELP

SISTERS.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

[3rd April, 1862]

Sir,—Will you kindly allow me space to draw

public attention to a quiet, unostentatious work which has now for

some little time been carried or by certain ladies, some of whom are

well known to be deep thinkers in all which concerns their sex, able

writers, and very hard workers?

It in well known that a

persevering attempt has now for some time been made to find

employment for a class of women whose condition in life is a very

pitiable one, women just educated enough to be above the work of

domestic service, but not sufficiently so to be equal to the duties

of governesses. Miss Faithfull, with her printing

establishment, has opened out one, but I fear as yet very limited

field of labour. Miss M. Rye has an office for copying law

papers, engrossing deeds, writing circulars, even copying sermons

and petitions. I hope the Revised Code Agitation has at least done

this good, that it has found her penwomen some bread. I believe a

lady named Craig procures employment at telegram work for other

women of this class. Miss Bessie Parkes and Miss Jane Lewin are two

more of these active ladies, in some circles well known for their

energy in this movement.

I speak from the best

authority when I say that these ladies all find that all they can

achieve in the way of finding employment for these unfortunate

members their sex is but very little indeed, compared with the

demand made upon them. It is not that they weary of their

labour of love, or are daunted in it, but they have arrived at the

conviction that an outlet must be found for some portion of the

stream of deserving applicants beyond the shores of Great Britain;

the battle of life here for educated women is, and has been for many

a year, so severe, that they and their kind champions at last feel

some—many—-must retreat, or be altogether beaten down.

A

field is now open to them, they are ready to seek its

occupation. It was found that this very class of women are

much wanted in Australia and Natal; that the colonists are often

seriously inconvenienced for want of the very same educated workers,

for whom the mother county can find no employment.

The

mere servant class this country has found in great numbers, and most

wisely aided the colonists to immigrate, to the great benefit of

both parties. But what is wanted is that class of woman

capable of filling the highest branches of domestic services,

capable of active as a governess; if unaccomplished, yet with |

education and ability sufficient to give a

plain good education to the children of the middle classes. Again, I

speak advisedly, there is room for schoolmistresses, who, though yet

below the standard now sought for in England, are yet well equal to

the task of teaching all that we are now going to demand as the

absolutely necessary education of our own poor people's

children.

These ladies of whom I have

spoken, with others whose names I do not make prominent, are

prepared to satisfy the public that this is true as regards the

demand in the colonies, as they are ready also to prove they have

the material to meet the demand. They argue that it is a

course good as to its policy to send out large numbers of these

women, as it is, to their knowledge, a noble field of charity.

They have communicated with persons of influence in the colonies.

They have done more;—they have already commenced, and with success,

their work, sending out some of their poor clients to these

colonies, and the result has been most satisfactory; they were at

once employed in positions of respectability, and at salaries which

it would have hopeless for them to have expected here.

Now, Sir, I do not wish to open any subscription list in your

columns, to start a "society" with all its live and dead stock of

expensive machinery. I don't desire a "meeting," a "bazaar," or even

a "festival," with a Duke in the chair, and a tavern bill in

incubation.

If you permit this letter to

appear, I hope it may induce a few of the wealthy ladies of the land

to communicate personally with any of

these

ladies whose names I have given. A letter to Miss H. Rye, 12,

Portugal-street, Lincoln's-inn, would, I am sure, procure an

interview with herself or any of her colleagues. It would be

shown by plain unmistakeable facts that there is a great merciful

work in hand, which will be cheered by sympathy, and can be most

materially aided by a very small ******* little money ******

ambitious to seek help by glorifying their work, as one in which at

great cost a great display is made; they are hard thinkers—a little

blue, if you will, just enough so to

make them wise as well as good. It is women's work,—I wish to

enlist such in it. I think I will undertake to say that for

every farthing given or lent them they will give an amount which

will satisfy even your obedient servant,

S.G.O.

____________

Ed. Text marked '***' was illegible in the

original.

|

|

――――♦――――

And to end, a fantasy . . . .

ISA IN THE

GARDEN.

|

|

ISA in

the garden stands,

And the winds, with

unseen hands,

Lift the midnight of her

hair

From her brow so white and fair.

Isa plucks with

finger-tips

One sweet rose; her crimson

lips

Match the colour and the tone,

But the dew is all their own.

And I think, as Isa

stands

With the rose within her hands,

Other sounds are in her ear

Than the river's gliding near.

Whispers soft as

whispers be

When love lends its voice, and

she

Hears its thrilling music stream

Through the wonder-gate of dream.

And then gentle

whispers say—

"Isa, Isa, come away,

We have in our fairy bower

One sweet spray of orange flower;

"This we keep to clasp

your brow

When your heart has breathed its

vow,

And you move away beside

One who claims you as his bride."

Isa smiles as still

she stands

With the rose within her

hands,

So I turn away and leave

Isa yet a maiden Eve.

ALEXANDER ANDERSON |

<>

|