|

An independent and

independent-minded Victorian, who left a legacy of writings and activity

in one of the most controversial issues of her age, the employment

of women.

|

|

|

EMILY FAITHFULL

(1835-95)

Publisher, lecturer, writer and activist

for women's welfare. |

EMILY

FAITHFULL

was born at Headley Rectory, Surrey, England, in 1835, the youngest

daughter in the Rev. Ferdinand Faithfull's large family. She was

educated both at home and, from the age of 13, at a

boarding school in Kensingston before being presented at court in 1857,

aged 21.

Emily later joined a small number of determined middle-class

women—the Langham Place Group (or Circle)—set on achieving

social reform. The Group, which included among its members

Adelaide Procter, Barbara

Leigh Smith (later Bodichon), Bessie Rayner Parkes, Jessie Boucherett,

Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn and Isa Craig,

took their name from the office of their campaigning periodical, the

English Woman's Journal, established in 1859 at 19 Langham Place,

London. Their aim was to improve the situation of women by pressing

for legal reform in women's status (including suffrage), exploring new

forms of employment and campaigning for improved educational

opportunities.

Emily's particular concern was the lack of opportunity in

Victorian Britain for women to acquire a trade or profession. Her

interest in women's employment grew out of her membership of the Society

for Promoting the Employment of Women, for which she served as Secretary

in 1859, and her membership of the committee of the National Association

for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS). Bessie Rayner Parkes

was also a member of this committee and it was she who introduced Emily to

the printing press. They employed Austin Holyoake, the brother of

George Jacob Holyoake, to

instruct them in composing, which demonstrated to Emily that this was

a suitable occupation for women.

|

"....True marriage is the crown and glory of a

woman's life; but it must be founded on love, and not on the desire

of a home or of support, while nothing can be more deplorable,

debasing, and corrupting than the loveless marriages brought about

in our upper society by a craving ambition and a longing for a good

settlement. Loveless marriages and a different standard of

morality for men and women are the curses of modern society...."

"Woman's

Needs"; a lecture at Steinway Hall, New York,

4th April, 1873 |

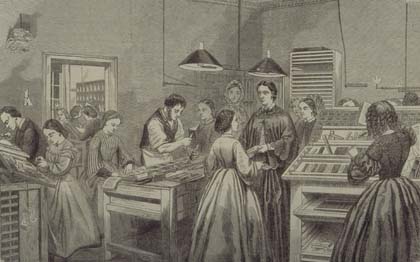

In 1860, Emily put her concern for

the employment of women into practice when she founded a printing works,

the "Victoria Press," at which she employed women as compositors and men

to do some of the presswork and heavy lifting.

|

THE TIMES

8 June, 1860.

THE EMPLOYMENT

OF WOMEN.—A

conversasioné of the Society

for Promoting the Employment of Women, in connexion with the

National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, was held

at 19, Langham-place on the evening of Friday, June 29. Lord

Shaftesbury took the chair at 9 o'clock, by which time a numerous

and influential audience had assembled. The chairman, in an

opening address, explained and enforced the principles of the

society, congratulated the members on the success which has attended

their efforts during the first year, and enforced the necessity of

still further extending their operations. Mr. Cookson urged

law engrossing as a suitable occupation for women, described the

office established by the society, which is already supported by

several solicitors, and gave an interesting account of the work done

there. Mr. Hastings spoke of printing as particularly well

adapted to women, and read a paper contributed by Miss Emily

Faithfull, on the introduction of women to the printing trade.

Mr. Mackenzie read a paper by Miss J. Bouchererett on bookkeeping,

stating that a want of knowledge of accounts was one great reason of

the disinclination to employ women in shops, showing how they might

be better fitted for the offices of cashiers and bookkeepers, and

announcing that a school to supply these deficiencies had been

opened by the society. Vice-Chancellor Wood spoke of the other

occupations for women, and recommended that they should be employed

as clerks in post-offices, and as managers in hotels, as

hairdressers, &c. He read a paper by Miss Parkes on the same

subject, and concluded with an eloquent appeal for further

subscriptions. The audience were then introduced into a lower

room, where the interesting collection of women's work in law

engrossing, printing, designing, &c., was exhibited, and excited

much admiration.

__________________

The Victoria Press.

Emily provided the typesetters with tall,

three-legged stools to alleviate some of the fatigue of standing at

the case during their twelve to fourteen-hour working day.

__________________

The Times

23rd July 1860

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir,—The

assistance the movement "for promoting the employment of women" has

received from you induces me to ask you to insert this letter in

The Times, as I think many will be glad to hear, so great is the

success of this office, that I have more work at this moment than my

12 women compositors can undertake, and I shall therefore be glad to

receive six or eight girls immediately. They must be under 16 years

of age, and apply personally at my office next week.

Your very truly,

EMILY FAITHFULL.

The Victoria Press, 9, Great Corum-street, July 21. |

Her efforts met with hostility from the printer's union, with

presses being sabotaged; to use Emily's own words . . . .

". . . . the girl apprentices were subjected to all kinds

of annoyance. Tricks of a most unmanly nature were resorted to, their frames

and stools were

covered with ink to destroy their dresses unawares, the letters were mixed

up in their boxes, and the cases were emptied of "sorts." The men who

were induced to come into the office to work the presses and teach the

girls, had to assume false names to avoid detection, as the printers'

union forbade their aiding the obnoxious scheme."

Despite this difficulty, the Victoria Press acquired a

reputation for good quality printing and, in 1862, its proprietor was appointed "Printer and Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty."

The Press continued

in operation for twenty years, producing a solid body of work including

thirty-five volumes of the Victoria Magazine, which advocated the

right of women to gainful employment and, between 1860 and 1864, the

Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social

Science. Originally located at Great Coram Street, in 1862 the press

moved to Farringdon Street, London, where the printing was carried out

with steam presses.

|

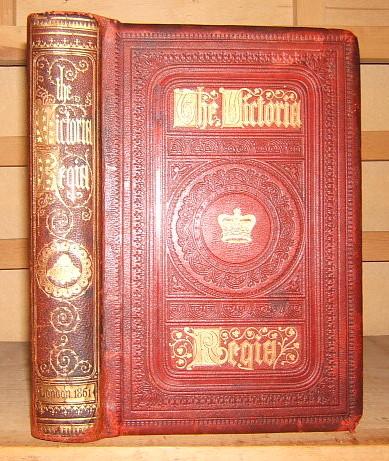

The Times

(28 December, 1861)

. . . . Next deserves to be noticed the Victoria

Regia (Emily Faithfull and Co, a joint-stock volume in which

Tennyson, Thackeray, Tom Taylor, Mrs. Grote, Lord Carlisle, Monckton

Miles, John Forester, Coventry Patmore, Matthew Arnold, Anthony

Trollope, and others, have taken shares. The editor of the volume is

Miss Procter, and the volume is "printed and published by Emily

Faithfull and Co., Victoria Press (for the employment of woman.)"

More than a year ago Miss Faithfull opened her office in order to

prove that the sphere of women in our country is much too

restricted. She thought that they would at least make admirable

compositors, and she desired, after a few months experience, to

produce a volume which should be a choice specimen of the skill

attained in her establishment. A number of our best authors have

been interested in the experiment, and have given their

contributions, while the Queen has accepted the dedication of the

work. Thus, from the social, as well as from a literary point of

view, the book in very attractive. The germ of the volume is Mr.

Tennyson's poem—

|

"THE SAILOR BOY.

"He rose at dawn, and flushed with hope

"Shot o'er the seething harbour bar,

"And reached the ship and caught the rope,

"And whistled to the morning star.

"And while he whistled long and loud

"He heard a fierce mermaiden cry,

"‘Boy, tho’ thou are young and proud,

"‘I see the place where thou wilt lie.

"‘The sands and yeasty surges mix

"‘In cave s about the dreary bay,

"‘And on thy ribs the limpet sticks,

"‘And in thy heart the scrawl shall play.’

"‘Fool,’ he answer’d , ‘Death is sure

"‘To those that stay and those that roam,

"‘But I will never more endure

"‘To sit with empty hands at home.

"‘My mother clings about my neck,

"‘My sisters clamour "Stay, for shame!"

"‘My father raves of death and wreck,—

"‘They are all to blame, they are all to blame.

"‘God help me! save I take my part

"‘Of danger on the roaring sea,

"‘A devil rises in my heart,

"‘Far worse than any death to me.’" |

|

|

|

|

The Victoria Regia,

bound in full red morocco.

A Volume of

Original Contributions in Poetry & Prose. Edited by Adelaide

A. Procter. Printed & Pub. by Emily Faithfull & Co., Victoria

Press, 1861. Surviving copies can fetch a high price on the

antiquarian book market. |

In 1864, William Wilfred Head became a partner in the

Victoria Press, taking over its management in 1865 and buying it out in

1867 (the transfer of ownership appears to have been 'unfriendly'—see

letters to

The Times). Head continued to run the press as an employment opportunity for women until

1881 when ownership was transferred to the Queen Printing and Publishing

Company.

|

"....We hear the

interests and rights of women spoken of as if these could be

separated from those of man, as if men and women were creatures of a

different kind. A most common and mischievous error is that which

would make woman the mere shadow and attendant of her lord, as if a

shadow could be a true helpmeet...."

"Woman's

Needs"; a lecture at Steinway Hall, New York,

4th April, 1873 |

In May, 1863, Emily commenced the Victoria Magazine

in which for eighteen years she continuously and earnestly advocated the

claims of women to remunerative employment.

|

The Times

(30 July, 1864)

. . . .

While Admiral Codrington was doing his duty to his Sovereign and his

country in the Crimea, he was obliged to leave his wife alone in

this country, but he made arrangements for her comfort, and at her

desire a lady whom she had selected became her companion during his

absence. That lady was Miss Emily Faithfull, of the Victoria Press,

and of 1, Taviton-street, Russell-square. The Admiral was absent

from April, 1856, until August 1856. Upon his return he found reason

to complain of his wife's conduct in some small matters, and some

slight differences arose between them, but nothing of any serious

importance occurred, and the Admiral had not the slightest reason

for suspecting her of any misconduct. The learned counsel then read

several letters written by Mrs. Codrington to the Admiral in the

latter part of 1856, while she was on a visit to some friends in the

country, showing that up to that time they were upon affectionate

terms. In the spring of 1857 there was a remarkable occurrence to

which it was necessary to call their attention. After the Admiral's

return from the Crimea Miss Faithfull, who had been his companion

during his absence, still continued an inmate of his house. From

time to time Mrs. Codrington had proposed that she should sleep with

Miss Faithfull, stating that she was subject to asthmas, and in the

spring of 1857 she positively and absolutely declined again to enter

the same bed with the Admiral, and she insisted on having a separate

bed and sleeping with the Miss Faithfull. This led to serious

disputes, and the Admiral, as he was in duty bound, communicated

with his wife's father and mother. Mr. and Mrs. Smith accordingly

went to the house, everybody was heard, the matter was explained,

and the result was that Miss Faithfull was dismissed from the house,

with the full concurrence of Mr. Smith. After this investigation had

taken place a packet was sealed up and placed by Mr. Smith in the

hands of General Sir William Codrington, the Admiral's brother, for

the purpose, as he said, of justice being done to the Admiral. .

. . |

In 1864, Emily was involved in the much publicised divorce of

Admiral Sir Henry Codrington, in which the admiral alleged that his wife, Helen Jane,

had ". . . . committed adultery with David Anderson and divers

other persons." The story presented in court by the petitioner

was, among other things—and in effect—that Emily had stolen his wife's

affections during a period in which she lived as Helen's companion in the

Codrington household. For her part, the respondent alleged . . . .

|

The Times

(30 July, 1864)

. . . . that

when the petitioner and respondent were occupying separate but

adjoining rooms in Eccelstone-square, the petitioner had one night

come in a night dress from his own room into the respondent's room

and had got into the bed where the respondent and Miss Faithfull

were then sleeping together, and had attempted to have connexion

with Miss Faithfull, and was only prevented from effecting his

purpose by Miss Faithfull's resistance. . . . |

Emily chose not to come forward to substantiate this allegation, which

would have subjected her to cross-examination by the petitioner's

counsel.

Overall, Codrington v. Codrington damaged Emily's

reputation within the Langham Place Group although surprisingly for an age

when the subjects of social scandal were considered more dangerously

contagious than today, it did not prevent marks of official recognition being

bestowed. In 1886, Emily received a grant of £100 from the Royal

Bounty fund and from 1889—"in consideration of her services as a writer

and worker on behalf of the emigration, education and employment of women"—an

annual civil-list pension of £50. In 1888, she was

presented with an inscribed and engraved portrait of Queen Victoria in recognition

of her dedicated work over thirty years in the interests of women.

Emily's only novel, "Change Upon Change", was

published in 1868. In this tragic love story

naive, honest and hard-working Wilfred falls for his coquettish cousin, Tiny,

the tale gradually working its way towards an increasingly predictable outcome.

It was later

republished in New York as "A Reed

Shaken with the Wind" (1873).

|

"A stormy day, raining a little ― and all the

ilexes and cypresses ink-black in the foreground, and, beyond, a

burning sheet of gold on the Campagna, and the piles of mountains all mixed up in

the clouds; some bright peaks of snow with bronze

light, the stormy, violent light that gives snow

such a wonderful colour, reminding one at the same

time of metal and of the softest, mellowest swan's

plumage. Then, the next mountain the fullest

lapis blue, and far off in the sunshine Soracte piled up all alone,

quite light cobalt in a sky of the fairest blue . . . . the only thing that

was not ink-black in the foreground was the Tiber,

and Heaven only knows where it got its flaming

brightness as it twisted under the black clouds on

its winding way. Yes, Rome is a wonderful place when you see

all that (and a thousand things besides) up at the top of a tower, and at the bottom

such statues as the Mars in repose, the Juno's head, and several

others which are beyond description beautiful."

Rome, from

'A Reed

Shaken with the Wind' |

|

SHOP ASSISTANTS.

Saleswomen in shops. This is a good employment for a strong young

person. A tall figure is considered an advantage, and the

power of standing for many hours is requisite. A good deal of

fatigue has to be undergone at first, but a shop girl told me that

after a few weeks, they get used to standing it seems as natural as

sitting. The life is far more healthy to most persons than

that of dressmaker.

The power of making out a bill with great rapidity and perfect

accuracy is also necessary, and this is the point where women

usually fail. A poor half-educated girl keeps a customer

waiting while she is trying to add up the bill, or perhaps does it

wrong, and in either case excites reasonable displeasure. This

displeasure is expressed to the master of the establishment, who

dismisses the offender and engages a well-educated man in her place.

He pays him double wages, but then feels sure that his assistant

will not drive away customers by his incapacity.

Parents who intend their daughters to become saleswomen should take

care that they are thoroughly proficient in arithmetic. Good manners

are also requisite . . . the higher the class of shop, the more

obliging and polished the manners of the assistants are expected to

be. The slightest want of politeness to customers, even if

they are themselves unreasonable and rude, is a breach of honesty

towards the owner of the establishment, for if customers are

offended they are likely enough to withdraw to some other shop.

No one, therefore, ought to enter on this employment who does not

posses entire self-command.

Salaries from £30 to £50 a year, with board and lodging. These

situations are usually obtained by private recommendation.

Emily Faithfull, Choice of a

Business for Girls (1864). |

Emily was a gifted and compelling speaker who became well known on the

lecture circuit, her talks being aimed mostly at furthering the interests of her

sex. She lectured widely and successfully in England and in the

United States, to which she made three lecture tours (1872-3, 1882-3, and

1883-4), publishing her account in "Three Visits to America" (1884).

Trans-Atlantic travel was not, at that time, without its perils; two out

of three of Emily's return passages to the U.S.A. were booked in steamers that were wrecked on their

previous voyages with considerable loss of life (see

Emily's own account).

|

"....She gave the best, and perhaps the only detailed resumé

of the industrial and educational progress of the women of England

yet given from the platform in this country. It cheered and

inspired her listeners, and the outbursts of applause that

frequently greeted her showed that speaking from her own heart she

had reached the hearts of others, and appealing for justice and

right, she was rewarded with respectful and appreciative

consideration...."

From the

Brooklyn Eagle,

April 1882. |

|

New York Herald

(2nd February, 1873)

Miss Emily Faithfull on British Notabilities.

Association Hall was more than than crowded yesterday afternoon, for

it was filled to overflowing, with an audience of ladies to listen

liken to Miss Emily Faithfull. Anna Dickinson, who was

scarcely recognizable until she spoke, so elegantly and fashionably

was she attired, introduced Miss Faithfull in a few characteristic

sentences, expressive of the delight she felt in introducing one so

eminent and so faithful to all that was promotive of the welfare of

woman, and her delight, she said, received a warmer glow in the

remembrance that Miss Faithfull was from "the mother land."

The subject of the lecture was Glimpses of Great Men and

Woman whom I Have Known;" and Miss Faithfull blended her own

personal experience with a cameo-kind of or personal sketch of the

more prominent of the men and women she referred to. The first

glimpse was at Lady Morgan, the authoress of "The Wild Irish Girl,"

whom the lecturer knew and was present at many of her receptions.

Lady Morgan was, she said, a firm believer in the practice long

adopted in the royal family of England, of giving to each of the

daughters an accomplishment or trade that they were specially fitted

for, that would place them above the adversities consequent upon the

accidents of fortune. then she spoke of the following:—Palmerston,

Tennyson, Disraeli, Lord Brougham, Lord Carlisle, Sir John Bowring,

Mrs Gaskell, Mrs Jameson, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Adelaide Procter,

Frederick D. Maurice, John Gibson, David Livingstone, Harriet Hosmer,

Lady Franklin, Caroline Norton, George Eliot, John Ruskin, Thomas

Carlyle, Baroness Burdett Coutts and Florence Nightingale.

This wondrous galaxy of brilliant stars in the the firmament

of fame twinkled and glittered, one after the other, as Miss

Faithfull revealed them to the view of her audience interspersing

each revelation with so much gossip, practical sense and high

sentiment, that the two hours' lecture was no more wearisome to the

attention than a pleasant gossip with a fascinating woman. |

In 1874, Emily was involved in setting up the Women's Printing

Society and, in 1877, the short-lived West London

Express. In 1881, she helped to found the International Musical,

Dramatic and Literary Association, which aimed to secure better protection

through copyright.

Census records throw

some additional light on Emily's life and

associates. The 1861 Census records her as a "Master

Printer" living at 19 Langham Place,

Marylebone, a "visitor" in the household of Matilda Mary Hays.

Matilda Hays is an interesting personality. A novelist and writer—she translated George Sand—she

was for a time (with Bessie Rayner Parkes) co-editor of The English Woman's

Journal, while Emily refers to Matilda in her article on "Women

Compositors" as a "partner" in the running of the Victoria

Press. Of difficult temperament, Matilda — "Max" or "Mathew"

to her intimates —was fond of masculine attire; according

to Elizabeth Browning, she "dressed like a man down to the waist".

Matilda had been the long-time companion of the American actress Charlotte

Cushman, until the latter transferred her affections to the sculptor

Emma Stebbins. Their unfriendly separation in 1857

concluded with Miss Cushman paying Matilda a cash sum in recognition of the years

she had devoted to their relationship at the expense of her career. Matilda

then became closely attached to Adelaide Procter, receiving

the dedications of Adelaide's

poem "A Retrospect" and

also of the first series of "Legends and Lyrics."

Following Adelaide's early death (in 1864), Matilda was awarded a Civil List

pension of £100 "in consideration of her constant labour of mind and

her distinguished attainments in literature" (The Times, 6

July, 1866) after which she drops from view and all that is known

subsequently is that she died at Toxteth, Liverpool, in September 1897.

|

|

|

Charlotte Cushman and Matilda Hays

". . . . Miss Cushman had genius of the highest

order. Her acting had a magnetic

effect upon those on the stage with her; for the time being she lifted

them up to a level near her own, for the atmosphere of genius is felt

behind the footlights as

much as it is in the auditorium. Her two watchwords

were "Devotion and Work," secrets of success which aspirants for dramatic

honours, however celebrated, would do well to take to heart, for no great

eminence can be ever reached without them. . . . "

Emily Faithfull, "Three

Visits to America" |

The census for 1871 records Emily, now described as a "Printer and Publisher",

living at 15 Princes Street, Westminster, at the head of a

large household comprising Kate M. Pattison, a "Secretary"; a

butler, his wife and three servants; and two lady lodgers, Eliza Rowney

(44) and Sarah C. Smith (17), both of whom are described as "Annuitants."

Ten years later finds Emily living at 52 Bryanston Square, Marylebone, at

the head of a somewhat smaller household comprising a cook and servant,

and two "visitors", Henry Mann, a "Manchester Cotton Merchant" and

the previously mentioned "Kate M. Pattison", now described as an "Actress"—Kate's age, given as 22 in 1871,

now appears as 25, no doubt in acknowledgment of the sensitivities of the

acting profession.

Finally, the 1891 Census records Emily, described as a "Journalist and Author",

living at 10 Plymouth Grove, Chorlton-cum-Medlock, Manchester, her

household comprising Charlotte Robinson (31), a "boarder" and by

occupation a "Home art-decorator" and who accompanied

Emily to America as her "secretary"; Elizabeth Begg (34) a "visitor"

"Living on her own means"; together with a cook and a servant.

It is surprising to learn that Emily, who suffered from asthma and bronchitis

for many years, was a heavy smoker, at least at

the time of her first American visit for in an article on "Smoking

Ladies," a Chicago journalist posed the following question to her

readers: ". . .

. For does not fat, famous and frolicsome Emily Faithfull smoke like a

Lake Michigan tug boat?" And it was from a bronchial disorder

that Emily

was to succumb at the age of 60 on the 31 May, 1895, leaving a legacy of

writings and activity in one of the most controversial issues of her age,

the employment of women.

|

Salt Lake

Tribune

(3rd June, 1895)

Emily Faithfull London June 2—The Times

announces the death of Emily Faithfull. Miss Faithfull was

born in 1835. She was presented at the court in her 21st year.

Becoming interested in the condition of women, she collected a band

of female compositors and in 1860 founded a typographical

establishment in which women were employed and for which she

obtained the approval of Queen Victoria, who appointed Miss

Faithfull printer and publisher in ordinary to her Majesty. In

May, 1863, Miss Faithfull started a monthly publication called the

Victoria Magazine in which for eighteen years the claims of

women to remunerative employment were earnestly set forth. In

1868 she published a novel entitled "Change Upon Change." She

achieved a marked success as a lecturer. In 1872-3 Miss

Faithfull visited the United States. After a third tour in

America in 1882-3 she published a book entitled, "Three Visits to

America," containing vivid descriptions of the various feminine

industries she found among the Mormons in Salt Lake City. In

commemoration of thirty years dedicated to her sex, Miss Faithfull

received in 1889 an engraving of her Majesty, which was sent her by

the Queen, bearing an inscription in her own handwriting, and

followed by a Civil Service pension. |

|

The Scotsman

(18th September, 1895)

By her will of the 18th October 1893 Miss Emily Faithfull, of 10

Plymouth Grove, Manchester, who died an the 31st May last, leaving

property of the value of £859, bequeathed all her personal estate

and effects to her friend Miss Charlotte Robinson, home art

decorator to Her Majesty, of 64 King Street and 10 Plymouth Grove,

Manchester, and 20 Brook Street, London, and the testator adds in

her will:—

"It is my desire that she retain during her life the pictures of my

mother, and grandfather and mother, and the portraits presented to

me by the Queen and the Queen of Roumania. At her death I hope

she will leave them to any member or members of my family she

pleases, remembering my preference for my nephew, Ferdinand

Faithfull Begg, to whose affectionate kindness I am most indebted.

I should like the said Ferdinand Faithfull Begg to have the volumes

of the Spectator and National Review at my death, and

any political volumes likely to be acceptable. I feel sure

that any loving members of my family, who may survive me, will

appreciate my desire that the few possessions I have should be

retained for the exclusive use, and as the absolute property, of my

beloved friend Charlotte Robinson, as some little indication of my

gratitude for the countless services for which I am indebted to her,

as well as for the affectionate tenderness and care which made the

last five years of my life the happiest I ever spent. I

desire, if possible, to be cremated, believing such a method of

disposition of my mortal remains is in the best interests of the

living; but in this matter I am willing to abide by the decision of

my friend Charlotte Robinson, and wish her, in conjunction with

Ferdinand Faithfull Begg, to accept all responsibility respecting

the arrangements which may have to be made, but I desire to have the

utmost simplicity observed and all unnecessary expense avoided." |

|

The Times

(5 January, 1895)

The remains of the late Miss Emily Faithfull, whose

work on behalf of women and its generous recognition by the Queen

made her name so widely known, were cremated yesterday at Chorlton-cum-Hardy,

near Manchester. The service was conducted by the Dean of

Manchester, and Mr. J. W. Maclure, M.P. was among those present. |

|