|

[Previous

Page]

|

|

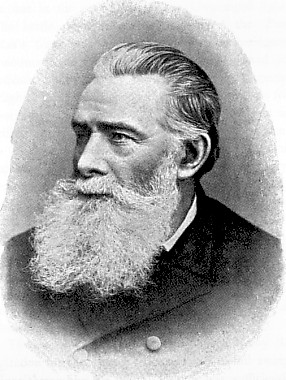

FEARGUS O'CONNOR.

(From a contemporary engraving.) |

CHAPTER XXI

FEARGUS O'CONNOR

SIR GEORGE CORNEWALL

LEWIS once wittily said something to this effect,

that life would be tolerable but for its amusements. Much in the

same way, it might have been said that the Chartist movement would have

been tolerably successful but for its leaders—some of them. There

were many able men in the ranks—earnest and eloquent men. Some of

them were earnest without being eloquent; a few, perhaps, were eloquent

without being earnest. The great fault of all, more or less, was

impatience—a desire to reap the harvest before they had sown the seed.

Next to this fault was the disposition to quarrel. But quarrelling

was almost inevitable when not one man, but many men, desired to become

dictator's. It was almost equally inevitable when such a man as

Feargus O'Connor, who had few of the qualities of a powerful leader save

extraordinary force of character, had acquired absolute dominion over the

cause. O'Connor quarrelled with all in turn—McDouall, O'Brien,

Cooper, Harney. There were minor quarrels too—between Bronterre

O'Brien and Ernest Jones, between Ernest Jones and Julian Harney, besides

other rivalries among smaller men in the movement. And we of the

rank and file took sides with one or the other—with fatal consequences, of

course, to the movement itself.

The ascendency of Feargus O'Connor would have been

unaccountable but for the fact that he owned the Northern Star.

That paper, besides being the source of his power, was a sort of small

gold mine to the proprietor. It was almost the only paper that the

Chartists read, and it had in consequence a very extended circulation.

Through it Feargus every week addressed a letter to his followers—"The

blistered hands and unshorn chins of the working classes." The

letter was generally as full of claptrap as it was bestrewn with words and

sentences in capital type. But the turgid claptrap took. The

people of that period seemed to relish denunciation, and O'Connor gave

them plenty of it. Blatant in print, he was equally blatant on the

platform. More of a demagogue than a democrat, he was fond of posing

as the descendant of Irish kings. "Never a man of my order," he was

in the habit of declaring, "has devoted himself as I have done to the

working classes." It was his delight, too, to boast that he had

"never travelled a mile or eaten a meal at the people's expinse." He

even claimed in 1851 that he had spent £130,000 in the cause of the

Charter. It pleased the working people to hear themselves addressed

as "Fustian Jackets," "Old Guards," and "Imperial Chartists." Nor

did it displease them when their leader assumed a royal title and called

himself "Feargus Rex."

The reports of some of his speeches indicate the kind of

fustian in which he now and then indulged. Here is part of what he

is recorded to have said at a meeting in Palace Yard, Westminster, on

September 17th, 1838:—

The people were called pickpockets. Now, he would

ask, what difference was there between a rich pickpocket and a poor

pickpocket? Why, there was this difference—the poor man picked the

rich man's pocket to fill his belly, and the rich man picked the poor

man's belly to fill his pocket. The people had borne oppression too

long and too tamely. He had never counselled the people to physical

force, because he felt that those who did so were fools to their own

cause; but at the same time those who decried it preserved their authority

by physical force alone. What was the position in which the working

classes stood? Why, they were Nature's children, and all they wanted

was Nature's produce. They had been told to stand by the old

constitution. Why, that was the constitution of tallow and wind.

The people wanted the railroad constitution, the gas constitution, but

they did not want Lord Melbourne and his tallow constitution; neither did

they want Lord Melbourne and his fusty laws. What they wanted was a

constitution and laws of a railroad genius, propelled by a steam power,

and enlightened by the rays of gas. They wanted a Legislature who

had the power as well as the inclination to advance after the manner he

had just pointed out. They wanted that the science of legislation

should not stand still. The people had only to show the present

House of Commons that they were determined, and its reform must take

place. But still, such men as Sir Robert Peel and little Johnny

Russell would try and get into it, even though they got through the

keyhole. But it was said the working classes were dirty fellows, and

that among them they could not get six hundred and fifty-eight who were

fit to sit in the House of Commons. Indeed! He would soon

alter that. He would pick out that number from the present meeting,

and the first he chose he would take down to Mr. Hawes's soap factory;

then he would take them where they should reform their tailors' bills; he

would next take them to the hairdresser and perfumer, where they should be

anointed with the fashionable stink; and having done that by way of

preparation, he would quickly take them into the House of Commons, when

they would be the best six hundred and fifty-eight that ever sat within

its walls. He counselled them against all rioting, all civil war;

but still, in the hearing of the House of Commons, he would say that,

rather than see the people oppressed, rather than see the constitution

violated, while the people were in daily want, if no man would do so, if

the constitution were violated, he would himself lead the people to death

or glory.

This was a specimen of Feargus's early style. Mr. Gammage has preserved a

specimen of his later. Describing a speech delivered at the Hall of

Science, Manchester, in August 1846, when he was fighting with other

Chartists about his Land Scheme, Gammage says:—

While addressing the meeting, O'Connor hit upon every sentence calculated

to rouse the hostility of his audience against his detractors, and to

elevate himself. He told them he had the evidence of a respectable

gentleman (whom he did not say), and also that of a boy, that at the

Examiner office they were in league with navvies to assassinate him,

which led to groans and cries of "Oh! the villains!" Again he said,

"Villains who quaff your sweat, gnaw your flesh, and drink the blood of

infants, suppose that I too would crush their little bones, lap up their

young blood, luxuriate on woman's misery, and grow fat upon the labourer's

toil." (Shouts of "No, never!" and waving of hats and hand

kerchiefs.) "No, I could go to bed supperless, but such a meal would

give me the nightmare; nay, an apoplexy." (Loud cheers, and "God

Almighty bless thee!") "I have now brought money with me to repay

every shareholder in Manchester." (Shouts of "Nay, but we won't have

it!") "Well, then, I'll spend it all." (Laughter and cries of

"Do, and welcome!") Again, he said, as an instance of his

condescension, "It was related of the Queen, that when she visited the

Duke of Argyle's, she took up the young Marquis of Lorne, and actually

gave him a kiss, and this was mentioned as a fine trait in her character.

Why, he (O'Connor) took up forty or fifty children a day and wiped their

noses, and hugged them. (Cheers, and expressions of sympathy from

the females in the gallery.) Did they think he was the man to wring

a single morsel from their board, or to prevent their parents from

educating and bringing them up properly? No, he was not: he loved

the children, and their mothers also, too much for that." (A female

in the gallery: "Lawk bless the man!") For more than three hours did

O'Connor address the crowded and excited meeting, which was so densely

packed before he commenced that the reporters had to be pushed through the

windows into the hall.

It was considered curious that Feargus's visits to towns in

the provinces generally synchronised with the appearance in the same towns

of a lady who was then a star in the theatrical world. This lady was

Mrs. Nisbett. There was as much gossip in Chartist circles about the

two as there was in Irish circles forty or fifty years later about Mr.

Parnell and Mrs. O'Shea. O'Connor himself does not seem to have made

much secrecy of the relations between himself and the actress; for in a

letter to a person who had helped him at the Oldham election, dated August

28th, 1835, he sent his best regards to the man and his wife, "in which

Mrs. Nisbett begs to join." The alliance, such as it was, was

probably consecrated by some measure of affection, since it was stated

that the lady, when O'Connor had to be removed to a lunatic asylum, left

the stage, and nursed and tended him as long as he lived.

The common notion of O'Connor outside the ranks of his

personal followers was that he was a charlatan and a humbug—an adventurer

who traded on the passions of the people for his own profit and advantage.

A correcter notion would have been that he was a victim of his own

delusions. It is certain that he did more than any other man in the

movement—more probably than all the other men in the movement put

together—to ruin the Chartist cause. But this is not to say that he

was dishonest. The Land Scheme which he grafted on to the demand for

political reform was one of the wildest and maddest schemes that ever

entered into the mind of a rational being. It was doomed to disaster

from the very beginning, and it brought loss and disappointment upon all

who touched it. The originator of the scheme, however, was the

greatest sufferer, for he lost his reason. The fact that the failure

had this terrific effect may perhaps be regarded as at least some evidence

of the man's sincerity.

The melancholy fate of Feargus O'Connor was, I think, hardly

more melancholy than that of another Irishman who figured prominently in

the Chartist agitation. James Bronterre O'Brien was "a Chartist and

something more." It seemed to him that political reform was less

important than agrarian reform and currency reform. The doctrines he

taught on these latter subjects made him an authority among a small school

of Chartists. But poor Bronterre ended his days as a loafer in Fleet

Street. It was there that I used to see him towards the close of his

career—shabby, snuffy, beery. A good speaker even to the last, he

was in demand at the Cogers and other debating halls of the Metropolis.

For opening a discussion in a pothouse, he was rewarded with five

shillings and his night's liquor. Another O'Brien shone or flickered

in the same arenas. And of him or of Bronterre—I am not sure which—a

wit of the period parodied Tennyson:

And I saw the great O'Brien sloping slowly to the West.

CHAPTER XXII

TWO DOCTORS AND A SCHOOLMASTER

THE more conspicuous of the early leaders of the

Chartists (next to those already mentioned) were John Taylor, Peter Murray

McDouall, Thomas Cooper, and George Julian Harney. The two first

were Scotchmen, both members of the medical profession, and both advocates

of what were called "ulterior measures."

Dr. Taylor, a native of Ayr, was arrested in Birmingham,

during the sitting of the first Convention in that town, for alleged

participation in the Bull Ring Riots of 1839. Harney describes him

as looking like "a cross between Byron's Corsair and a gipsy king," with

"a lava-like eloquence that set on fire all combustible matter in its

path." It was said that he had inherited a fortune of £30,000, the

greater part of which he spent on revolutionary enterprises.

Insurrections in Greece and conspiracies in France were alike in his line.

A picturesque figure was Dr. Taylor. Hardly less picturesque was Dr.

McDouall, whose long cloak and general style helped to give him the

appearance of a hero of melodrama. McDouall also was often in

trouble with the authorities. Subsequent to 1848, he settled down to

the practice of his profession in Ashton-under-Lyne. But not for

long. Agitation had unfitted him for a regular life. Friends

subscribed funds to enable him to emigrate to Australia, where, according

to a sworn statement of his widow, he died "about May, 1854." That

Dr. McDouall was a man of some taste and culture may perhaps be gathered

from the following lines, written to the air of the "Flowers of the

Forest" while he was a prisoner in Chester Castle, previous to 1840:—

|

Now Winter is banished, his dark clouds have

vanished,

And sweet Spring has come with her treasures so rare;

The young flowers are springing—the wee birds are singing,

And soothing the breast that is laden wi' care.

But loved ones are weeping—their long vigils keeping—

The dark prison cell is the place of their doom;

The sun has nae shining to soothe their repining—

To gild or to gladden their dwellings of gloom.

To them is ne'er given the loved light of heaven,

Though sair they are sighing to view it again;

Though fair flowers are blowing, in full beauty glowing,

They flourish or fade for the captives in vain.

And thus are they lying—in lone dungeons dying—

The sworn friends of freedom—the tried and the true;

By slow famine wasted—life's bright vision blasted—

'Tis Summer's prime shaded by Winter's dark hue.

In vain are they wailing—nae tears are availing,

But tyrants exult o'er their victims laid low,

Or look on unheeding, though life's race is speeding;

Their fears will depart with the death of their foe.

But I look not so proudly, and laugh not so loudly,

Nor dream that the struggle of freedom is o'er;

Your prisons may martyr the chiefs of our Charter,

But the bright spark it kindled shall burn as before.

And Winter is coming, wi' wild terrors glooming,

To weaken the sunbeam and wither the tree;

The loud thunder crashing—the red lightning flashing,

Are the might of a people resolved to be free. |

No more remarkable testimony to the exciting character of the

decade from 1839 to 1849 can be adduced than the fact that almost every

man who rose to prominence in the Chartist ranks during that period came

under the lash of authority. Thomas

Cooper was no exception to the rule. Either the Chartists were

too much given to violent language and threats, or the magistrates and

judges were too much given to a stringent interpretation of the law.

We owe to Cooper's incarceration, however, that remarkable prison poem,

the "Purgatory of Suicides."

First a shoemaker, then a schoolmaster, afterwards a newspaper reporter,

the author of the "Purgatory" had reached what might well be called the

years of discretion before he plunged into the stormy waters of Chartism.

While serving as reporter on a Leicester journal, he came to learn the

miseries of the Leicester stockingers. Also, in his official

capacity, he came to attend Chartist meetings. The two experiences

combined to drive him into the Chartist whirlpool. From reporting

Chartist lectures he came to deliver Chartist lectures himself.

Before long he was the acknowledged leader of the Leicester Chartists.

Somehow, he associated Shakspeare with Chartism, and gave to his

particular society the name of the bard. Other eccentricities could

probably at this time have been laid to his charge. But the charge

which caused him to be prosecuted in the first instance was that of having

preached arson at Hanley. Acquitted on this count, he was afterwards

prosecuted for sedition and conspiracy, receiving sentence of two years'

imprisonment. When he had served his time and written his poem, he

varied his speeches for the Charter with lectures on literary, critical,

and historical subjects. Among his lectures was a series on

Strauss's "Leben Jesu," then just translated by Marianne Evans, better

known later as George Eliot. I remember to this day the strange

effect which the reading of the summary of these discourses produced on a

youthful and unsettled mind. The summary appeared in Cooper's

Journal, a weekly periodical of much greater value than the common run

of Chartist publications. But the lecturer did not himself long

remain steadfast to the views he expounded. As he had changed from

piety to rationalism, so he changed from rationalism to piety again.

And the rest of his long and active life was spent in preaching the Gospel

to all the earth that he could reach.

Thomas Cooper had the "defect of his qualities." I have

given one example of his irritability. Many others were known to his

friends. Indeed, he was quite unfit for controversy. This he

came to acknowledge himself: so that all through his later career as a

lecturer and preacher he systematically declined discussion. Warm in

his friendships, he was bitter in his animosities. An old comrade

has recorded how, while he was still on good terms with O'Connor, he broke

off in a speech he was delivering in Paradise Square, Sheffield, to lead

the crowd in singing the Chartist song:

|

The Lion of Freedom has come from his den;

We'll rally around him again and again! |

When he quarrelled with the Lion of Freedom, as he did soon afterwards, he

was as impassioned in denunciation as he had before been in praise.

But Thomas Cooper had other qualities that redeemed his

defects. Innumerable instances of his kindness and generosity are

recorded. It is a loving trait in his character that he never forgot

or neglected any old friend whom he knew to be living in any of the towns

he visited during his later peregrinations. These peregrinations

continued till he was near or past eighty years of age. When his

work was done, and just before he died at the venerable age of

eighty-eight, he received a grant of £200 from the public funds. The

grant was made on the application of Mr. A. J. Mundella, then member for

Sheffield, one of his earliest political converts at the time he was

leading the Leicester Chartists. Close upon a quarter of a century

before his demise in 1892 (that is to say, in 1868) he corrected an

erroneous report respecting himself in an amusing letter to the Lincoln

Gazette:—"The Nottingham papers say I am dead. I don't think it

is true. I don't remember dying any day last week, though they say I

died at Lincoln on Tuesday. 'Lord, Lord,' as Falstaff said, I how

the world is given to lying!"'

Thomas Cooper, besides being a preacher and lecturer of no

mean ability, was a man of marked literary eminence. Poet, essayist,

novelist, he was also the author of a model biography. "The

Life of Thomas Cooper, Written by Himself," published twenty years

before he died, is so admirable a piece of work that it will keep alive

his fame for years and years to come. But it contains one passage

which does not, perhaps, do justice to his reasoning powers. It is a

passage in which he claims that his life was once saved by what seemed

like a special intervention of Providence. When on his way from

London to fulfil an engagement in the provinces, and about to enter a

railway carriage at Euston Station, he was induced by a porter to take a

seat in another part of the train. The carriage which he did not

enter was smashed to atoms in a collision, the people in it being killed

or maimed, while the carriage which he did enter was in no way injured!

Thomas Cooper left it to be inferred from his narrative that Providence

had interposed to save his life.

The story is as little credible as another story of a similar

kind about Bishop Wilberforce—Wilberforce of Oxford and Winchester.

One night, so this latter story runs, the Bishop was returning home from

his club. A man's figure passed him in the street, ran up the steps

to his front door, and then suddenly turned round and faced him. The

man's figure was his own. Back went the Bishop to his club instead

of entering his house. Next morning he heard that a chimney-stack

had fallen through the roof on to his bed!

CHAPTER XXIII

GEORGE JULIAN HARNEY

NO leader of the Chartist movement left behind him a

fairer record than George Julian Harney. He was the last survivor of

the National Convention of 1839. John Frost lived to a greater age

than Harney; but he was an older man when he associated himself with the

agitation. Frost died at eighty-nine, Harney at eighty-one.

Frost had reached years of maturity at the time of the Convention; Harney

was only twenty-two. It is likely that he was the youngest member of

that notable assembly. When he died in 1897, there died with him a

fund of information about the exciting political events in which he had

taken part that can now never be supplied.

|

|

GEORGE JULIAN HARNEY.

(From a photo taken in 1886.) |

It was the eventful struggle against the Newspaper Stamp

Act—a struggle which filled the common gaols of the country with earnest

men and women—that first drew Harney into politics. He was then

sixteen years of age. For three years afterwards he was in the very

thick of the Unstamped fight. The battle raged most fiercely around

the Poor Man's Guardian, which, as Henry Hetherington announced on

the title-page, was "published in defiance of law, to try the power of

Right against Might." Harney was twice thrown into prison for short

terms in London. His offence was that of selling the Poor Man's

Guardian. Then he went to Derby to commit the same "crime."

"One Saturday evening," he wrote, "at a court hastily, unusually, and for

all practical purposes privately held, I was sentenced to pay a fine of

£20 and costs, or go to prison for six months." He underwent the

imprisonment; but the pains of it, as he gratefully recorded, "were

somewhat mitigated by the humane intervention of the late Mr. Joseph

Strutt—an honoured name—then Mayor." The revolt of the people—for it

was a revolt—was, as already narrated, completely successful.

Three years after the imprisonment at Derby the agitation for

the People's Charter was in full swing. Notwithstanding his youth,

Harney was sufficiently well known throughout the country to be elected

one of the delegates for Newcastle to the Convention of 1839. The

proper title of that body—for it is as well to be particular in historic

matters—was the General Convention of the Industrial Classes. The

delegates for Newcastle—Robert Lowery and Dr. Taylor were Harney's

colleagues—were "elected at a large open-air meeting in the Forth on

Christmas Day, 1838, which meeting was attended by deputations, in some

instances processions, from the district on both sides of the Tyne."

Among other extravagant things that Harney seems to have favoured was the

"sacred month." It was one of the "ulterior measures" the Convention

discussed when the House of Commons had rejected the National Petition for

the Charter. All the delegates from Newcastle supported it.

But the scheme was foolish, and, being foolish, failed—though it is fair

to point out that the old Chartists differed from all later strikers in

this, that they sought nothing for themselves alone, and that the

sacrifices they proposed to make were intended to achieve objects that

would, as they believed, benefit the nation at large.

Harney had the reputation of being a fiery orator. He

was certainly consumed with enthusiasm. It was almost impossible for

such a man at such a time to avoid coming into collision with the

authorities. Two such collisions occurred—first in 1839, for a

speech at Birmingham; the second in 1842, for taking part with fifty or

sixty others in a convention at Manchester. For the Birmingham

speech Harney was arrested in Northumberland, handcuffed to a constable,

and taken back to Warwickshire. The arrest took place at two o'clock

in the morning. There were fewer railway facilities in those days

than there are now, accounting for the circuitous route the captors

pursued with their prisoner. First a hackney coach from Bedlington

to Newcastle; then the ferry across the Tyne to Gateshead; then the rail

from Gateshead to Carlisle; then the stage coach over Shap Fell to

Preston, at that time the terminus of the North-Western Railway; and

finally the train from Preston to Birmingham. But the police in the

end had all their trouble for nothing, since the grand jury at Warwick

declined to find a true bill against their prisoner. Harney was next

arrested at Sheffield for the Manchester business. The trial of the

fifty or sixty Chartists was held at Lancaster in March, 1843.

Harney was appointed by his comrades to lead the defence. This he

did with so much energy and eloquence that O'Connor, in the published

report of the trial, bore the following testimony:—"It would perhaps be

invidious to point particular attention to the address of any individual

where all acquitted themselves so well; but the speech of Harney will be

read with peculiar interest, and fully justifies the position which he

occupied as first speaker." But this trial was abortive, too; for,

though the prisoners, or some of them, were found guilty, the Court of

Queen's Bench afterwards pronounced the indictment bad.

Meantime, Harney had gone through his first Parliamentary

contest—if such a term can be given to encounters in which never a vote

was given to the Chartist candidate. Lord Morpeth, afterwards Earl

of Carlisle, was in 1841 seeking the suffrages of the electors of the West

Riding of Yorkshire. Harney was nominated in opposition. The

nomination took place at Wakefield. It has already been mentioned

that an extraordinary effect was produced when, in response to the call

for a show of hands for the Chartist, a forest of oak saplings rose in the

air. But Harney's great feat in the candidate line was in opposing

Lord Palmerston at Tiverton in 1847. Nominated by a Chartist butcher

named Rowcliffe, he delivered a vigorous criticism of Lord Palmerston's

foreign policy in a speech two hours long. The "judicious

bottle-holder," as the noble lord was called, is said to have confessed

that his policy had never before been subjected to so searching an

examination. Nor did he forget his old opponent. Years

afterwards, when somebody was soliciting subscriptions in the lobby of the

House of Commons for Chartists in distress, Palmerston asked about his

"old acquaintance, one Julian Harney." Being told that Harney was in

America, he replied: "I hope he is well; he gave me a dressing at

Tiverton, I remember." The contest at Tiverton was remarkable,

inasmuch as the opposition candidate, though he went to the poll, did not

receive a single vote. The borough returned two members, and the

result of the election is thus recorded in the Parliamentary Poll Book:—

|

John Heathcote (Liberal) .

. . 148

Viscount Palmerston (Liberal) .

. 127

George Julian Harney (Chartist) .

. 0

|

Besides lecturing and agitating in all parts of the country,

Harney was busy with journalism. He was first sub-editor and then

editor of O'Connor's paper, the famous Northern Star. When,

owing to a disagreement with O'Connor, he severed his connection with the

Star, he started periodicals of his own—first the Democratic

Review, then the Red Republican, and then the Friend of the

People. I was a subscriber to them all. Also he founded in

1849 a society called the Fraternal Democrats. I had always voted

for Harney as a member of the Chartist Executive, and now I joined the

Fraternal Democrats. A letter to him on the subject brought about an

acquaintance which, becoming more and more intimate as the years advanced,

lasted till his death—a period of nearly half a century. The

collapse of the Chartist movement drove Harney to other ventures.

From 1855 to 1862 he was editing the Jersey Independent. Then

he betook himself to America, where he remained till, broken in health, he

settled down at Richmond-on-Thames to struggle and die. It was under

his cheerful and untiring guidance that I saw the sights of Boston in

1882. He was then living at Cambridge, not far from the "spreading

chestnut tree" under which the "village smithy" stood, nor far from the

house of Longfellow himself. The old Chartist had adorned his home

in Massachusetts, as he did afterwards his apartments at Richmond, with

portraits and relics of the poets he loved, of the patriots he admired,

and of the friends and colleagues with whom he had worked—Shakspeare,

Byron, Shelley, Burns; Kosciusko, Kossuth, Mazzini, Hugo; Cobbett, Oastler,

Frost, O'Connor; Linton, Cowen, Engels, Marx. Some of the portraits

are now mine. Among the relics was a handful of red earth from the

memorial mound of Kosciusko at Cracow.

It was Harney's opinion that the art of letter-writing was

dying out. He himself, however, did his utmost to keep it alive.

Hundreds of his letters, now lying in lavender, testify to his epistolary

industry—all characteristic and all long, some long enough to fill a

newspaper column. In his letters as in his private intercourse, he

was an incorrigible joker. He joked even about his ailments and his

agonies. For years he was a martyr to rheumatism. As far back

as January, 1884, he wrote me from Cambridge, U.S. :—"I am 'all in the

Downs.' The rheumatism in the shoulder less painful (of late), but

always there. But my understandings wuss and wuss—especially my

feet. By Heaven! the man with the peas in his shoes hardly had a

worse time of it. That ass might have boiled his peas; but there is

no such resource for me. Aching, burning, shooting, and other

varieties of pain; and no sham pain either—as West [18]

would say, 'not a blessed dhrop.' " Closing a longer account of his

increased infirmities ten years later, he sardonically exclaimed: "Oh!

what a piece of work is man!" While residing at Richmond as the

guest of a daughter of another old Chartist agitator, though he was

wracked and twisted and helpless, he amused everybody with his jests.

Mrs. Harney, who had a profitable connection as a teacher of languages in

Boston, had to let him come to England alone. Once, when she had

crossed the Atlantic to stay with him, she took him out in a Bath chair.

Loud were his jokes with the chairman. "Oh, Julian!" cried Mrs.

Harney. "Ah!" said the servant-maid to the hostess, "Mrs. Harney

doesn't know Mr. Harney as well as we do!"

All his sufferings notwithstanding, he was able to the very

last to write or dictate admirable contributions to the Newcastle

Weekly Chronicle. These contributions were generally on

books—not formal reviews, but discursive comments on authors and their

works, interspersed with delightful touches of personal experience.

It is not a matter of feeling, but of fact, that one of the most effective

pieces written in 1896 on the centenary of Burns's death came from

Harney's pen. Occasionally he diverged into politics. Here he

aroused both anger and enthusiasm—anger in one party, enthusiasm in

another. The Editor had as much as he could do to keep the peace

among his readers when Harney had his fling at Mr. Gladstone. The

old Chartists hated the Whigs more than they hated the Tories. Much

in the same way, Harney disliked the Liberals more than he disliked the

Conservatives. It was not quite easy to account for his intense

rancour against Mr. Gladstone, whom he called, not the Grand Old Man, but

the Grand Old Mountebank. The mention of Mr. Gladstone, even after

he was dead, seemed to have the same effect as a red rag is supposed to

have on a mad bull. Yet the veteran was judicious and impressive

when he discussed political principles instead of political parties.

A testimonial was presented to him shortly before he died. Replying

to the deputation which presented it, he thoughtfully said: "We have not

now so much to seek freedom as to conserve it, to make good use of it, to

guard against faddists who would bring us under new restrictions as bad or

perhaps worse than the old." For the rest, he expressed his

philosophy of government in the pregnant lines of Byron :

|

I wish men to be free,

As much from mobs as kings, from you as me. |

The last days of the old Chartist were rendered as happy and

as comfortable as his pains and his helplessness would allow by the

devoted attentions of his wife. That lady, sacrificing her

professional business in America, came over to nurse him to the end.

When that end came, there passed away from earth no worthier citizen or

braver spirit than George Julian Harney.

CHAPTER XXIV

THE LATER CHIEFS OF CHARTISM

THE history of the-Chartist movement is divisible

into two periods—the period before and the period after 1848. During

the former period, the movement was, speaking generally, gaining strength;

during the latter, it was unmistakably losing it. Some of the

leaders whose names are familiar to the student of politics were connected

only with the earlier phase of the agitation; others were connected with

both its earlier and its later phases; others, again, came into it only

when the popular fervour for the Charter was transparently declining.

The most noted of the later leaders was undoubtedly

Ernest Jones. Like Thomas Cooper,

Ernest Jones plunged into the agitation, not as a youth, but as a man of

mature years. Feargus O'Connor claimed descent from an Irish King;

Ernest Jones was the godson of a German King. The royal favour was

bestowed upon the younger chief of Chartism while his father was serving

as equerry at the Court of Hanover. The family did not return to

England till Ernest had already given indications of those poetic and

literary talents which he afterwards so abundantly displayed. The

fiery and sympathetic spirit of the youth had also been shown in an

attempt to assist the insurgent Poles. Although he was educated for

the law and was admitted to the Bar, he had no need to pursue the

profession till late in life. Certain land speculations of his,

however, cost him his fortune. It was then that he joined the

Chartists. Mr. George Howell has told the story of these

transactions in a series of articles that were published in the

Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. The narrative, based for the most

part on a singularly bald diary kept by Ernest Jones, leaves the

impression, whether well or ill founded, that Chartism would not have

gained its conspicuous recruit if his speculations in land had not

terminated disastrously.

But Ernest Jones made up for his late entrance into the

movement by the enthusiasm and even violence of his advocacy. It

came about that he shared the fate of all the other leading spirits of

Chartism: he was prosecuted and imprisoned. No consideration was at

that time shown to political prisoners, and less than usual was shown to

Ernest Jones. The indignities he suffered, however, neither damped

his ardour nor curbed his tongue. But he could not keep alive a

dying cause. A last flicker of the candle occurred when it was

proposed to establish a People's Paper under the joint editorship

and control of Harney and Jones. The proposed editors quarrelled;

the scheme came to naught; Harney quitted the field; and his rival was

left with a feeble and squalid following to carry on what remained of the

agitation. Ernest Jones kept the old flag flying till he was almost

starved into surrender. When near its last gasp, he was in the habit

of addressing open-air assemblages on Sunday mornings in Copenhagen

Fields, now the site of Smithfield Cattle Market. I walked from a

distant part of London, through miles of streets, to hear him. It

was during the Indian Mutiny. The old fervour and the old eloquence

were still to be noted. But the pinched face and the threadbare

garments told of trial and suffering. A shabby coat buttoned close

up round the throat seemed to conceal the poverty to which a too faithful

adherence to a lost cause had reduced him. A year or two later even

Ernest Jones had to confess that Chartism was dead. He turned his

attention again to the law, settled in Manchester, and was soon on the

road to acquiring a lucrative practice.

Then came his great discussion on Democracy with John Stuart

Blackie, the famous professor of Edinburgh [Ed.—see Blackie 'On

Democracy'; see Jones 'Democracy

Vindicated']. It was about this time that I saw and heard

him at Newcastle Assizes. Josiah Thomas, a botanical practitioner

who was highly respected in the town, was charged with some technical

error. Ernest Jones was retained for the defence. The defence

was so well managed that the accused, much to the gratification of the

general public, was honourably acquitted. Not long afterwards, just

when he was on the point of being chosen one of the members for

Manchester, Ernest Jones died. Before this sad and sudden event

occurred, it is satisfactory to know that Harney and Jones, comrades in a

great fight, had become reconciled.

Ernest Jones was a poet: so was

Gerald Massey, the Felix Holt of George Eliot's novel. But

Gerald Massey was more fortunate that Ernest Jones in the attentions he

received from authority; for while Jones was prosecuted by one Government,

Massey was favoured with a pension from another. There was nothing

dishonourable in either transaction, so far as the recipients of

punishment or pension were concerned. It was Massey's poetry that

won the kindly notice of the advisers of the Crown. The poet was

very young when he caught the fever of revolutionary politics. Poor

as he was, he yet found means to start a revolutionary paper—the

Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom. If it did not live long, that was

not because it had not merit enough to entitle it to live.

Unfortunately, the Chartist movement, when Gerald Massey joined it, was in

a moribund condition. But he made his mark in it before it died.

Harney was publishing his Red Republican, one of the best of his

literary ventures. There appeared in it some verses in praise of

Marat that seemed to ring like a trumpet. They were written by the

Hon. George Sydney Smythe, afterwards Lord Strangford. Harney had

copied them from a work entitled "Historic Fancies." No young

Revolutionist could have read them without a thrill. Far greater was

the thrilling sensation when the verses were dramatically recited.

Gerald Massey used to recite them at Chartist meetings. A friend of

mine who had heard him described the effect as magical. But the poet

not only declaimed the inspiring poems of others: he wrote inspiring poems

of his own. One of these, appearing in Harney's publication, led on

to fortune. It is Harney who tells the story. I had a long

letter from him in 1884—as long as this chapter—written from Cambridge,

Boston, Massachusetts, where I had enjoyed his hospitality two years

before. The letter is full of characteristic humour—as, indeed, all

his letters were. The humour is notable even in the way he relates

how Gerald Massey came to attract the notice of the authorities:—"Hepworth

Dixon had no umbrella. Taking refuge from the rain in a news-shop

doorway, he saw the Red Republican. He bought a copy, and

read Gerald Massey's 'Song

of the Red Republican.' That introduced Massey to the Athenæum.

The Athenæum introduced Massey to

good society. Lord Alfred and Lady Beatrice were struck by the

beauty of the poetry and the face of the young R.R.; and so, and so, at

last a pension." The poet has enjoyed the pension for many years,

has devoted much of his time since to inquiries into mystic subjects, but

did not forget his old comrade when a testimonial, mainly promoted by the

Editor of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, was presented to George

Julian Harney on the anniversary of his eightieth birthday.

The founder of Reynolds's Newspaper was better known

to the public of his day as a writer of romances than as a political

leader. Yet he came to the front as a Chartist chief subsequent to

the ferment which the Revolution of 1848 caused all over the Continent.

George W. M. Reynolds occupied about the same position in English

literature as Eugene Sue occupied in French literature. The stories

he published dealt mainly with mysteries and scandals, especially

mysteries and scandals of courts and society. To a certain extent he

was before his time. The reading public in the middle years of the

century thought his romances coarse and vulgar, and left them to the

appreciation of the patrons of penny numbers. With the taste for

sensation and salacious details which the modern novelist and the modern

dramatist have cultivated, it is not at all unlikely that he would, if he

had flourished at the end of the century, have been admitted to the

hierarchy of fiction. It was understood that he was the son of an

admiral, and that he had wasted a fortune of ten thousand pounds in the

attempt to establish a daily newspaper before he found his vocation as the

author of highly-flavoured tales. Reynolds's Miscellany was a

popular periodical when the excitement produced by the French Revolution

encouraged its proprietor to undertake another adventure. This was

Reynolds's Political Instructor, to which Bronterre O'Brien and

other Chartists and Democrats contributed, and in which the portraits and

biographies of prominent Chartists and Democrats were printed every week.

Reynolds's Political Instructor was the forerunner of Reynolds's

Weekly Newspaper. Reynolds himself came then before the public

in person, made speeches on Chartist platforms, and was elected a member

of the Chartist Executive. I do not think, however, that any large

number of Chartists accepted him seriously. O'Connor and O'Brien,

Jones and Harney, all had their followers; but Reynolds had no such

distinction. Indeed, it was rather as a charlatan and a trader than

as a genuine politician that G. W. M. was generally regarded by the rank

and file of Chartism.

The movement was already fast declining when Thornton Hunt,

George Jacob Holyoake, and

William James Linton began to take an

active interest in its fortunes. Hunt was less of a Chartist than a

Littérateur, Holyoake less of a

Chartist than a Socialist, Linton less of a Chartist than a Republican.

The election of all to the Chartist Executive failed to save the cause.

R. G. Gammage and James Finlen were still lecturing in the provinces; but

George White, John West, and James Leech seemed to have dropped out of the

running. The Executive consisted of nine members. Of these

nine members on January 1st, 1850, only two or three are remembered even

by name now:—Thomas Brown, James Grassby, Thomas Miles, Edmund Stallwood,

William Davies, G. J. Harney, John Milne, G. W. M. Reynolds, and John

Arnott. An election later in the same year gave the following

result:—Reynolds, 1,805; Harney, 1,774; Jones, 1,757; Arnott, 1,505;

O'Connor, 1,314; Holyoake, 1,021; Davies, 858; Grassby, 811; Milne, 709.

Not elected:—Hunt, 707 ; Stallwood, 636; Fussell, 611; Miles, 515; Le

Blond, 456; Linton, 402; Wheeler, 350; Shaw, 326; Leno, 94; Delaforce, 89;

Ferdinando, 59; Finlen, 44. Thornton Hunt was elected subsequently,

but Bronterre O'Brien, Gerald Massey, and Thomas Cooper had declined to

stand. It will be noted that the highest vote in 1850 was 1,805,

indicating that the number of active members of the National Chartist

Association was probably not more than two or three thousand. In

1852, however, even this small membership must have fallen off one half,

for the highest vote recorded then was only 900. Four new names

appear in the list of the Executive for that year—those of W. J. Linton,

John Shaw, J. J. Beezer, and Thomas

Martin Wheeler. Anthony came to bury Cæsar,

not to praise him. The new members must have come to bury Chartism,

not to praise it. Funds were falling short, too. The

subscriptions for the first quarter of 1852 amounted to no more than

£27—hardly sufficient to pay the secretary's salary, not to speak of

office expenses, with never a penny for printing or propagandism.

The Chartist movement was indeed dead, though neither then nor later was

there any formal burial.

But the movement could not in one sense be considered to have

failed. The principles embodied in the Charter have been at least

partially recognised. The suffrage has been extended; the property

qualification has been abolished; vote by ballot has been enacted; and the

anomalies connected with electoral divisions have been rectified.

Payment of members and annual Parliaments are really the only two of the

six points of the Charter that yet remain untouched. The changes

effected in the law, however, are less remarkable than the changes

effected in public sentiment. People who have not shared in the

hopes of the Chartists, who have no personal knowledge of the deep and

intense feelings which animated them, can have little conception of the

difference between our own times and those of fifty or sixty years ago.

The whole governing classes—Whigs even more than Tories—were not only

disliked, they were positively hated by the working population. Nor

was this hostility to their own countrymen less manifest on the side of

the "better orders." More or less of the antagonism here indicated

continued down to the death of Lord Palmerston. Then a

transformation was worked in the sentiments of the great body of the

people. Thanks to the political earnestness, but still more to the

political intrepidity, of later statesmen, working men, enfranchised by

household suffrage, commenced for the first time to associate themselves

closely and actively with the orthodox parties in the State. We

still have our disputes; we still differ materially in opinion on

questions of the day; we still prefer Mr. Balfour to Sir

Campbell-Bannerman or Sir Campbell-Bannerman to Mr. Balfour; but we are no

longer, in the sense we once were, two nations.

CHAPTER XXV

A ROMANCE OF THE PEERAGE

DURING the whole period of the Chartist agitation,

and indeed for years before and after it, the representation of Cheltenham

was controlled and practically owned by the Berkeleys. But who were

the Berkeleys? The answer to that question is a romance of the

peerage that has frequently been recounted before the law courts.

The romance begins towards the end of the eighteenth century.

Berkeley Castle, the Berkeley estates, and the Berkeley earldom were held

in 1784 by Frederick Augustus, the fifth Earl of Berkeley. Frederick

Augustus seems to have been a rake of the first water. The evidence

adduced at the several trials to establish the claim to the earldom leaves

no doubt on that point. Nor does the lady whom he married after many

years of illicit connection appear to have been a model of virtue.

The lady was Mary Cole—called by the common folk Moll Cole—the daughter of

a Gloucester butcher. Mary, as well as at least one of her sisters,

fell an easy prey to the blandishments of rank and wealth. Both were

no doubt attractive in person, and both became the mistresses of men of

fashion. Susan figures only in the chronicles of scandal; but Mary,

owing to the attempts that were made to prove that she was married to the

Earl of Berkeley eleven years before she actually was married, figured

also in the chronicles of the law. None of these discreditable facts

would perhaps have become public property if the illegitimate products of

Mary's misalliance had shown the same respect for the honour of their

mother as the eldest of her legitimate sons did.

Mary Cole gave birth to several sons before she became

Countess of Berkeley. William Fitzhardinge Berkeley, afterwards Earl

Fitzhardinge, was the eldest of these sons. Among the others were

Henry Fitzhardinge Berkeley, member for Bristol, the mover of an annual

resolution in favour of the Ballot; Craven Fitzhardinge Berkeley, member

for Cheltenham, but not otherwise notable; and Maurice Fitzhardinge

Berkeley, an Admiral of the Fleet and member for Gloucester, who, on the

death of his elder brother, was elevated to the peerage as Baron

Fitzhardinge. There were also legitimate sons of the connection

between Mary Cole and the fifth Earl of Berkeley, for the couple were

married at St. Mary's, Lambeth, in 1796. The eldest of these

legitimate sons was Thomas Moreton Fitzhardinge Berkeley, while another

was Grantley Fitzhardinge Berkeley, who made some little noise as a

novelist and a writer of books on sporting matters. When the fifth

Earl of Berkeley died in 1810, William, the eldest son, who had sat in the

House of Commons as Viscount Dursley, claimed the earldom, but, as the

result of a great trial in 1811, failed to sustain the claim. Some

years later, probably for political reasons, Colonel Berkeley, as William

came to be called, was created first Baron Segrave and then Earl

Fitzhardinge. The eldest of the legitimate sons of the Earl of

Berkeley, Thomas Moreton Fitzhardinge Berkeley, chivalrously declined to

claim the peerage and property because it would have been necessary, in

order to establish his title, to asperse the character of his mother.

The earldom at his death went, therefore, to a distant kinsman, a

descendant of the fourth Earl of Berkeley. The ruling of the House

of Lords in 1811 was confirmed, after another and last trial, by the House

of Lords in 1891. Many extraordinary facts adduced in the case were

recited by the Lord Chancellor in delivering the final judgment of the

law.

A desire seems to have entered the minds of the Earl and

Countess of Berkeley, somewhat late in life, to make out that they had

been secretly married in Gloucestershire in 1785, eleven years before they

were admitted to have been married in Lambeth. To bolster up this

claim there were believed to have been tamperings with the parish register

of Berkeley, the earl himself, it was alleged, having had a hand in the

forgeries. But Mary Cole, according to her own testimony, was at the

very time when the banns of marriage were said to have been published at

Berkeley (published, by the way, in an inaudible voice by the officiating

clergyman) living in Kent in the service of a Mrs. Foote. Other

evidence of the butcher's daughter, contravening the pretensions she

subsequently set up, was given at second hand by the Rev. John Chapeau.

Mary Cole at the period of the conversation to which the reverend

gentleman testified was known as Miss Tudor, the mistress of Lord

Berkeley. Mr. Chapeau, taking shelter from the rain in Miss Tudor's

house in London, found her discharging a servant who had come from the

country, and trying to persuade her to return to her friends. The

girl refusing, "saying she liked to stay in London better," Miss Tudor

remarked to Mr. Chapeau that "a girl with a good countenance, and

dismissed from service without money, would be sure to fall a prey to some

man or other." And then she added that she had once been in a

similar situation herself.

The story Miss Tudor thereupon related to Mr. Chapeau, as

given in Mr. Chapeau's evidence, is one of the most extraordinary, that

was ever told, even at second hand, in a court of law. Being

discharged and destitute, so she is said to have said, she at first found

refuge in the house of a friend of her mother's. The kindness she

received there, however, was not long continued; for the gentleman,

fearing scandal, informed her that she must go down to her friends in

Gloucester. So she was turned adrift with a present. Mary had

two sisters in London, one of whom, Ann Farren, was living in dirt and

penury. The other sister, Susan, she had been enjoined by her mother

never to speak to again. But she was so distressed at the miserable

circumstances in which she found Ann Farren, and so reluctant to remain in

her house, that she resolved to disobey her mother. And now comes

the most wonderful part of the narrative she is alleged to have imparted

to Mr. Chapeau:—

I went to my sister Susan's, took up the knocker, and gave a loud rap.

Who should come to the door but (as if it had been on purpose) my sister

Susan herself, dressed out in all the paraphernalia of a fine lady going

to the opera? She took me into her arms, carried me into the

parlour, and gave me refreshment; began to tear a great many valuable

laces of 16s. a yard to equip me for the opera, and when I was so dressed

I looked like a devil. I went to the opera, and was entertained with

it, and at night returned again to my sister's; and there I found a table

well spread, not knowing that my sister ever had any fortune. At

that table were Lord Berkeley, Sir Thomas Kipworth, I think a Mr.

Marriott, and a Mr. Howarth. The evening went off very dull, and

they soon left the place. The next night we went to the play in the

same manner and returned in the same manner, and with no other difference

than a young barrister, whom I thought agreeable, and if I had been

frequently with him should have liked him very much. When they went

away, I requested my sister to give me a cheerful evening that we might

recount over our youthful stories. The day was fixed, and our supper

consisted of a roast fowl, sausages, and a bowl of punch. In the

midst of our mirth a violent noise was heard in the passage, and in rushed

two ruffians, one seizing my sister by the right hand and the other by the

left, trying to drag her out of the house in order to carry her to a

sponging-house.

The rest of this amazing story is given in Mr. Chapeau's own words:—

She told me the men declared they would not quit Susan, her sister, unless

they received a hundred guineas. She fainted away; then, when she

came to herself, she found Lord Berkeley standing by her sister Susan who

was not there before. Miss Tudor fell upon her knees, and desired my

Lord Berkeley to liberate her sister; that she had no money to do it

herself, and, if he would do it, he might do whatever he would with her

own person. He paid down a hundred guineas; the ruffians quitted

their hold; and my lord carried off the lady. "Mr. Chapeau," she

concluded, "I have been as much sold as any lamb that goes to the

shambles."

Strange and almost incredible as this narrative is, it was

accepted by Lord Eldon in 1811, and was not questioned by his successor

eighty years later. Further, as the Lord Chancellor of 1891

remarked, not only was Lady Berkeley not called to contradict it, but

evidence was given by the Marquis of Buckingham that corroborated it.

Lord Berkeley told him, the marquis deposed, that "he had got hold of Mary

Cole in London, and that he had paid a large sum of money for her."

The Marquis of Buckingham's story was in other particulars hardly less

astounding than that of Mary Cole. The Earl of Berkeley, he said,

was afraid, from the circumstances of his family, that the castle and

honour of Berkeley would be severed from the title. To avert this

catastrophe, as he thought it, he entertained the idea that his brother's

son, who would probably inherit the title, should marry his (Lord

Berkeley's) illegitimate daughter. The child who was thus to be

bartered was at the time only three years old. But the device, as

the Lord Chancellor explained, was not pursued, not because of the infancy

of the girl, but because she died before it could be accomplished.

Gossip was making free with Lord Berkeley's affairs even

before Lord Berkeley died. Thus Lady Jerningham, whose correspondence was

published in 1896, wrote from Brighton in 1806:—

Lady Berkeley was a Housemaid, but always a Virtuous Woman. Lord

Berkeley's Fancy for Her was so Imperious that he resolved upon regular

matrimony. After a time, Repenting of this measure, he prevailed on

the Clergyman to tear the Leaf out of the Register that witnessed his

being a married man. But then again Regret Came, as a Child had

arrived every year, so He married the same Maid again; and the fourth Son

was Supposed to be the inheritor of his title. But soon after, the

Clergyman who had first tied Him in Wedlock dyeing, He then declared the

date of his previous marriage and proclaimed that his first Born Son was

Lord Dursley. He Could not Say this during the Clergyman's Life, as

the tearing the Register is Felony. So all this made a sad work, but

Lord Thurlow declared there is not a doubt but that the first marriage was

Legal, and the Eldest Son is accordingly Stiled Lord Dursley.

The sons of the fifth Earl of Berkeley, legitimate and

illegitimate, washed a lot of their dirty linen in public. William,

the eldest son, was, like his father, a desperate rake, and made his house

at Cheltenham—where he lived at one time with the wife of Alfred Bunn,

the "poet Bunn" of Drury Lane—the centre of many scandals. [19]

A fascinating Don Juan he must have been too; for it was said that prudent

mammas made it a point of sending their daughters away when his lordship

came to town. Nevertheless, it was the custom to ring the bells of

the parish church when Lothario paid his periodical visits to German

Cottage. Moreover, he propitiated the fashionable classes by

providing stags for them to hunt and hounds with which to hunt them.

But it came to pass one day that the parish bells were silent when Earl

Fitzhardinge honoured the place with his presence. Loud was the

clamour which arose, especially as about the same time the nominee of

Berkeley Castle was rejected by the electors. The august patron of

the borough, we were told, would withdraw his patronage; his house and

furniture would be put up to auction; the glory of German Cottage would be

no more. As a matter of fact, he did for a season refuse to supply

the stags for the hunt, and imperiously demanded that the hounds should be

at once returned to Berkeley Castle. A furious quarrel broke out among the

brothers also. Grantley, who figured conspicuously in the quarrel, was

member for one of the divisions of Gloucestershire. As I remember him, he

was a tremendous dandy. It was during the general election of 1847, when

Grantley Berkeley had revolted against his brother, and when Grenville

Berkeley, a cousin of his, was set up in opposition, that the family's

dirty linen was washed in public. Grantley, in spite of his dandified

appearance, or perhaps because of it, was the more popular candidate ;

anyway, he carried the election against Grenville. [20]

The political literature of the time, however, throughout the whole

constituency of West Gloucestershire was besmirched with personal

scandals.

The story of the Berkeley family, interesting as a romance of

the peerage, is not without interest also as exemplifying the enormous

political influence which territorial nobles, notwithstanding the scandal

of their private lives, exercised in England even after the Reform Bill of

1832. |