|

ON THE CENTENARY OF J. C. PRINCE.

BORN JUNE 21ST, 1808.

DIED MAY 5TH, 1860.

|

THOU sleep'st, O son of toil and child of song,

But still thy strains are swelling in the air;

The music thou hast made doth roll along,

Awakening kindred echoes everywhere.

Men pause and listen to thy tuneful lyre,

Catch from it something of the spirit's flame,

Which kindles in their hearts a strong desire

To conquer sin and rise above their shame.

Cold poverty thy ardour could not stay,

Nor shake thy spirit from its love of right.

Though sore beset, thou still didst pour thy lay,

And turn with hopeful courage towards the light,

And point thy fellows to their highest good —

A life of true and helpful brotherhood.

Nor hast thou sung in vain, for men have heard

And blest thee, humble singer, for thy strain;

Because its magic power their souls hath stirred,

And made them strong to fight with self and pain.

Yea, this is thine, and this the truest fame —

The power to cheer, and sooth and elevate,

And teach high truth; and so thy lowly name

Is great in worth, not with the world's vain state.

Hence, though thy voice is hushed, thy songs still live,

Inspiring hearts that love the pure and sweet.

And this centenary men gladly give

To thy dear memory the praises meet —

The honour which they feel to thee belongs,

Immortal singer of immortal songs.

David Lawton |

――――♦――――

|

|

|

|

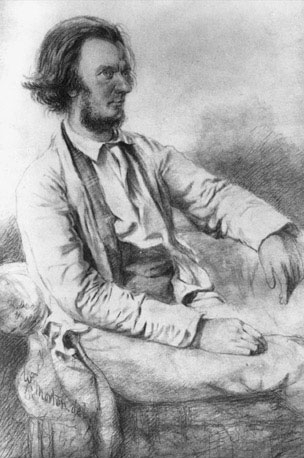

JOHN CRITCHLEY PRINCE

(1808-1866)

"He knew every string upon the lyre of life, and

swept its chords with the hand of a master."

Picture courtesy of

Tameside Local History and Archives. |

"......No casual visitor to the Poets' Corner

could fail to notice a dark-complexioned, delicate, fragile-looking man,

with a finely moulded head, who drank slowly but steadily, and said

little, but whose dark eyes, which gleamed through the glasses of a

constantly-worn pair of spectacles, seemed the eyes of a man who might

have much to say. The indication was deceptive, for the owner of them,

John Critchley Prince, was among the silent singers. Never was there a man

of genius—and genius Prince undoubtedly possessed—whose conversation

gave less evidence of his powers......."

From Frazer's Magazine, 1881.

――――♦――――

"......It has been said that the poems of a man are beaten out

upon the anvil of his life; and there are comparatively few poetic

works to which this aphorism is more applicable than those of John

Critchley Prince....."

Lithgow "The Life of John Critchley

Prince."

――――♦――――

"......He was not a prince of this world; and few men of his mental calibre cared

less for the dross that causes so wide a gulf between all classes of

society. The garret or the cellar, with a favourite friend or

author, was a paradise to Prince."

JOHN BARON.

――――♦――――

"....Those who judged Prince solely from appearances, and those

who, seeing only his faults, allowed themselves to be blinded as to

the good within him, were incompetent to form a just estimate of

such a man, and could not, certainly, wash their hands of that for

which they were not altogether irresponsible.

Although highly gifted he was very human; and in regarding

his weaknesses every allowance should be made for the circumstances

of his life, and the peculiarity of his temperament.

Simple-minded and highly sensitive, few had suffered more keenly

from the natural foes of humanity; and his mental constitution was

such as predisposed him to temptations and to influences which were

calculated to weaken the power of his volition.....

.....Those who knew him best, loved him most; and however he may

have erred, however he was misjudged and misunderstood, the higher,

better self of the man, and the genius of the poet, still survive in

the rich legacy of song which he has bequeathed to posterity."

Lithgow "The Life of John Critchley

Prince."

――――♦―――― |

Born in Wigan, Lancashire, to Joseph Prince and his wife Nancy,

JOHN CRITCHLEY PRINCE received some little formal education at a Baptist Sunday

School. At nine years of age he began work with his father as a

'reed-maker', a 'reed' being a tool used by hand-loom weavers to separate

threads. At eighteen, he married Ann Orme, a resident of Hyde near Manchester where

Prince was to live for a number of years, and eventually to die. A

family soon followed and by 1830 the pair had a son and two daughters.

|

A NIGHT

THOUGHT.

How grandly solemn is this arch of

night,

How wonderfully beautiful and vast,

Crowded with worlds enswathed in living light,

Coeval with th' immeasurable past!

With what a placid and effulgent face

The mild moon travels 'mid her golden

isles,

And on the earth, asleep in night's embrace,

Pours the sweet light of her serenest

smiles!

Can I, O God, who tremble here with awe,

Doubt the Designer, scoff at the

design,

Deny that all is of Thy wisdom Thine,

Fashioned by Thee, and governed by Thy law?

I marvel at that being who can

see,

In those, Thy mighty works, no evidence of Thee.

JOHN

CRITCHLEY

PRINCE

|

Employment prospects being bleak, Prince sought work in France, but to no

avail (see the tale, "Pauline Peronne"). After suffering much hardship during his return journey

(related in "Sketch of the Author's

Life"), he arrived

home

to find his family in the Wigan poorhouse. In later years Prince moved

around Lancashire, mainly in Blackburn, Ashton and Hyde, searching for

casual

work. He supplemented his income by contributing poems to local

periodicals and scrounging off acquaintances.

Prince published his first poetry collection, "Hours With the Muses", in 1841. It

sold well, running to five editions and attracting attention in London. Other collections followed,

some published

and sold privately by the author; "Dreams and Realities" in 1847, "The

Poetic Rosary" in 1850, "Autumn Leaves" in 1856 and "Miscellaneous Poems"

in

1861.

Included within these are several short prose pieces,

such as "Passion

and Penitence", "A Stray Leaf",

"Random Thoughts," and "Changes

for the Better",

which demonstrate no mean talents as a story-teller

and essayist.

The record suggests that in his day Prince was considered an accomplished member

of Manchester's community of poets

and writers, being ranked among such local notables as

Samuel Bamford, Elijah Ridings and

John

Bolton Rogerson.

|

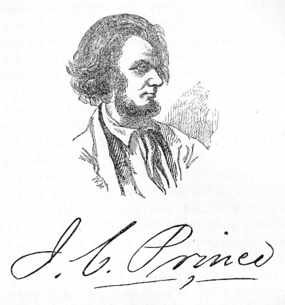

TRIBUTARY STANZAS TO J. C. PRINCE.

BY

JOHN BOLTON

ROGERSON |

|

When first I saw thy sweet and polished lines,

Though they were penn'd not by a scholar'd hand,

Even as the sun through mist of morning shines,

I knew that they were destined to command

The praise and wonder of thy native land;

And on the banner of wide-circling fame

Inscribe, in dazzling hues, thy then unhonoured

name!

And so it is!—thy aspirations high,

Thy powerful pleadings for a suffering race;

Thy ardent love for heavenly Poesy,—

The feelings pure which in each line we trace,—

Have for thee gained a proud and envied place

Among the bards, who heavenwards cleave their

way,

And gain by strength of wing, a bright immortal day.

Thou need'st not now, a wretched outcast, tread

With slow and weary steps a foreign shore;—

England will find a shelter for thy head,

And thou shalt know the want of food no more:

Be true unto thyself—there is in store

A future, rich in many happy days,

And thou shalt find the bard treasured as are his

lays. |

Walk forth and worship Nature as thou

hast,—

Drink in the beauty of her vales and streams;

Wander again, as when, in days long past,

Thy soul, enwrapt in its poetic dreams,

Became instinct with holy Sabbath themes;

And then, in thoughts majestic and sublime,

Poured forth the noble strain which shall contend

with time.

Give us thy songs of freedom once again—

Raise high thy voice for liberty and love;

Tell to the world the woes of toiling men,

And thou their dearest champion wilt prove—

Perchance the great and mighty then may'st move:

Speak in thy wonted tones aloud of wrong—

Who may divine the power and influence of

song?

Hang not thy harp upon the willows now—

Be not with what thou'st won alone content;

A wreath more glorious yet may grace thy brow—

On high achievement be thy mind still bent;

Gifts like to thine were surely never meant

To be unused or thrown neglected by—

Well is he paid whose dower is immortality!

Manchester, May 1842. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

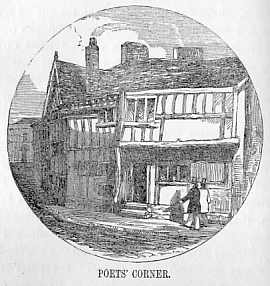

The Sun

Inn, Long Millgate, Manchester,

during the 1840s, the scene of 'poetic soireés'

attended by Prince, Rogerson and other local bards. |

Various effort were made by well-wishers to help Prince alleviate his

poverty and acquire a better

living, including several cash grants from the Royal Bounty Fund, but each

failed through his

addiction to alcohol, the "fiend" whose ravishes he

deplored in his verse (see "The

Saving Angel") and who he tried in vain to overcome (see "Abjuration").

|

"Of the poet Prince,

who was sadly addicted to intemperance, he said, 'Prince writes like

an angel and lives like a devil.' Prince had borrowed a

sovereign from Dugdale, which . . .he failed to pay back.

Dugdale, not being able by other means to come by his own,

determined to try what poetry and wit combined could do. He

wrote a poem, "The Sovereign," and dedicated it to the "Prince," and

every stanza began with Prince, and ended with Sovereign.

"Still he will stick to the sovereign!" "Republican, Radical,

too, and still he sticks close to the—sovereign!" Poor

Prince! He couldn't pay, but pleaded for

forgiveness, and composed the

beautiful moral poem of that title. This was in December,

1849. . . . . .

. . . . . ."About this time the Scotchmen

of Blackburn gave a banquet to the "Bards of Blackburn."

Prince, at the time residing in the town, and being invited, of

course, took precedence, and was elected president of the meeting,

the Bard of Ribblesdale being installed in the vice-chair. All

the loyal and royal toasts having been duly honoured, "The Town and

Trade of Blackburn," "The Lancashire Witches," and other toasts were

given. The president at length proposed "The health of the

worthy 'vice,' "remarking, while upon his feet, that he had

unbounded admiration for Mr. Dugdale as a man, but that he was no

poet. Dugdale's turn came. In response he gave "Our

Worthy President," and professed a boundless admiration for his

talent as a poet, but drily added, "he is no man."

|

|

Anecdotes concerning the Blackburn poet Richard

Dugdale,

related by

William Billington. |

By 1860 poverty appears to have been biting hard, or maybe Prince's

creative genius was on the wane, or both, for in a letter published

in the Ashton Reporter for the 14 January of that year, he is accused of ".....being

in the habit of palming upon publishers and editors compositions

said to be original, but are in reality only second hand pieces,

having been slightly altered in the wording or measure...."

|

DAILY NEWS

30 January 1856. |

|

JOHN CRITCHLEY

PRINCE—We have received

from a correspondent half-a-guinea, in aid of the author of the

verses "The Child and the Dew-drops," which appeared in the Daily

News of Monday last. The money has been transmitted to Mr.

Prince; but we have to request such of our readers as are disposed

to follow the good example of our correspondent to transmit their

donations direct to the poet, whose address was given in our

Monday's issue. |

His first wife having died in 1858, Prince married Ann Taylor in 1862.

This apart, his final years were marred by declining

health and the hardship resulting from the near collapse of the Lancashire cotton industry

during the American Civil War, a time known in the locality as the 'Cotton Famine'.

|

DEAR

wife, we struggle in a time

Saddened by many a shade,

For warfare in another clime

Has paralysed my trade;

And 'mong the thousands of our class,

So meanly clothed and fed,

We've had our share of grief, alas!

Pining for needful bread.....

JOHN

CRITCHLEY

PRINCE |

John Critchley Prince died at Hyde, in 1866, almost

blind and partially paralysed by a stroke suffered shortly after his

second marriage. He is buried there in St George's churchyard.

....Funereal month!

thy cold oppressive frown,

Piercing the tangled byways of the town,

Shadows a thousand hearthstones, where the soul

Is warped and withered, by the stern control

Of such realities as almost seem

The dark distortions of a madman's dream:

Fathers sit brooding o'er their wretched state,

With looks of anger, and with hearts of hate;

Mothers, with haggard and bewildered air,

Survey their little starvelings, and despair;

Children, grown prematurely old, decay

In apathetic squalor, day by day,

And still and stealthy cunning takes the place

Of childhood's natural gaiety and grace;

While their harsh destiny implants such seeds

As rankly germinate in moral weeds,

Which thrust the flowers of gentleness apart,

And drain the dews of goodness from the heart.

JOHN

CRITCHLEY

PRINCE |

|

――――♦―――― |

|

JOHN

CRITCHLEY PRINCE

The might of right, the love of love,

the fire

Of hope and aspiration urged him on,

While Prince for peace and freedom tuned his lyre.

Though bright its light, his lamp of life still shone

In this direction and in this alone.

The true, the brave, the fair, the beautiful,

Are gathered up and garnered in his lays.

With skill 'twas his the choicest flowers to cull,

Enhancing still their perfume and their blaze.

And may our workman-poet's well won bays,

His glowing garland grow nor dim nor dull—

The pure, the gladsome current of his song,

Fresh, smooth, and clear, if seldom deep or strong,

Through countless years its wealth of waters roll along!

WILLIAM

BILLINGTON |

JOHN

CRITCHLEY PRINCE.

Amongst the workmen-poets of our land

He stands—a Prince by nature, as by name;

A bright star in the firmament of fame,

Shedding a radiance beautiful and grand!

Though lowly born, his was a master's hand;

And wondrously he swept the heaven-sent lyre,

As, now with sweetness, then with martial fire,

He sang the songs that so belovèd

stand.

While frail in life, he had a noble mind,

For nobly rings the music of his song;

He laboured for the welfare of mankind,

A champion of the weak against the strong.

Long may those sweet and fervent songs endure

That show his "love for freedom and the poor."

GEORGE

HULL |

|

JOHN CRITCHLEY

PRINCE.

FAREWELL,

thou gifted singer! thy sweet songs

Have charmed the ears of thousands in our land:

Now thou art gone, we feel that we have lost

One of the greatest of the gifted band.

Tho' thou art dead, thy honoured name shall live

For ages yet to come: and thy pure lays

Be read and prized by myriads yet unborn,

And in their hearts thy songs shall find a place.

His like again, alas! we may not see:

Few living Bards have sung so well as he!

SAMUEL

LAYCOCK |

|

Considering Prince's dismal situation—he borrows from

Shakespeare "my mean estate" to describe his lot—his verse is,

for the most part, surprisingly optimistic. A notable exception

is "Death of a Factory Child", in which Prince addresses the harsh social conditions

of the day of which he had much

first-hand experience (Gerald Massey's

"Lady Laura"

part II takes a similar theme)........

|

DEATH OF A FACTORY CHILD.

Hear me! ye firm and uncorrupted few,

Followers of freedom! and of virtue too!

Ye, who are pleading with a noble zeal

For poor men's rights—rejoicing in their weal;

Friends of the parent—guardians of the child—

Whose frames are wasted, and whose souls defiled

Within these halls of tyranny which stand,

Gloomy and vast, o'er all the sinking land.

Too long, my harp hath breath'd of fancy's dreams

Too long responded to unworthy themes.

Farewell ye once-lov'd fictions of my youth,

Its future tones shall harmonise with truth.

To rouse the Labourer in peril's hour;

To cheer the victims of a lawless pow'r;

To wake that slumbering energy of soul

Which brooks no wrong, and spurns unjust controul;

To add me feeble voice to that which rings

With awful thunder in the ear of kings;

This is my hourly hope, my daily aim;

If virtuous men approve, I seek no higher fame:

The long drear winter night was gathering fast;

The snow danced wildly on the fitful blast;

Within yon Bastile's suffocating walls,

(Whose very name my sickening soul appals,)

The gas which burns to light these living graves

Gleam'd on the faces of a thousand slaves.

I saw, and knew one gentle victim there,

The youngest of a widow'd mother's care:

Hard had he labour'd since the morning hour,—

But now his little hands relax'd their pow'r—

Yet, urg'd by curses or severer blows,

Without one moment's brief, but sweet, repose,

From frame to frame the exhausted sufferer crept,

Piec'd the frail threads, and, uncomplaining, wept.

While yet the night was boisterous and chill—

While winds were loud, and snows were drifting still,

The bell gave out its long expected sound,

The mighty engine engine ceased its weary round.

Forth rush'd the the captives,—a degraded train!—

Till morn should summon them to toil again.

Some to the maddening ale-cup rashly sped;

Some to the short oblivion of their bed;

But he whose tale is woven in my song—

The first to fall, of that devoted throng—

With mingl'd cold and pain his tears ran o'er,

As the keen ice-wind entered every pore.

I ask'd his ailment, but he did not speak;

His fate was written on his ghastly cheek,—

I strove to help him with a friendly hand:

Alas! poor boy! he could not walk or stand.

I clasp'd my arms around his wasted form,

And bore him through the fury of the storm;

Up the dark street my eager footsteps bent,

Cursing the power that doom'd him, as I went;

His mother met me, with unfeign'd alarms,

And snatch'd the slaughter'd victim from my arms,

Kiss'd his pale lips, and call'd upon his name;

He murmur'd faintly, but no answer came.

I turn'd in grief from her imploring cries;

Unbidden tears were springing in my eyes;

Yet, breathing words of hope, I sought my home,

To ponder upon miseries to come.

The wond'rous wizard, Sleep, had now unfurl'd

His drowsy pennons over half the world;

The widow's children to their beds were gone,

And left her calm, yet mournfully, alone—

Alone with him, the idol of her heart.

Whose sinless soul was yearning to depart;

She, mute at length, with sorrow and dismay,

Wept, o'er his shattered frame, the night away.

Time was, ere commerce seal'd his early doom;

Shut up in Moloch's life destroying womb;

Ere yet the roses of his cheeks were pale,

He ran uncurb'd o'er mountain, moor, and vale:

Lur'd by the hives of bees, the voice of birds,

Sweet and familiar, as his mother's words,—

With buoyant step he sallied forth at morn,

And pluck'd his hasty dinner from the thorn;

He knew each sylvan and sequester'd nook;

He watch'd the secret mazes of the brook

Thread the dark forest; roam'd the laughing fields,

Deck'd with each golden bud that summer yields,

The same, though changeful nature frown'd or smil'd,

A healthful, innocent, and joyous child.

Thus, in the mourner's harass'd mind were glass'd,

These sad, yet sweet, reflections of the past,

Until these thrilling words her vision broke:—

'Mother! dear mother!'- twas her boy who spoke.

With fever'd lips he ask'd the cooling draught,

And, long and deeply, from the cup he quaff'd;

But, scarcely had he turn'd his head to rest:

Fondly secure upon his mother's breast,

A sound, which woke no feeling but of fear,

With well-known import smote his startled ear—

A sound alas! which prov'd his dying knell,—

The horrid clangour of the Bastile bell!

Then, starting up, he gaz'd on vacant space,

Cried, as he listen'd with bewilder'd face,

'Oh! mother, mother, I can work no more,

My head is painful, and my feet are sore;

Forgive me, mother, if I thus complain—

I fear I never shall be well again;

And if I die, O! do not weep for me,

But make my grave beneath some pleasant tree,

Where summer flowers around its roots may spring,

And summer birds within its branches sing;

And tell my loving sisters when they weep,

I saw my gentle father, in my sleep;

And, as he kindly looked and sweetly smil'd;

I thought he call'd me his own happy child.'

The suffrer spake his last—his eyes grew dim;

The cruel spoiler palsied ev'ry limb;

One sigh—before the victory was won,—

One gentle tremor—and the strife was done;—

Whilst the glad spirit, freed from chains of clay,

Soar'd to her native realms, away, away.

My painful task is drawing to a close;

I would not dwell upon a parent's woes.

She mourned for him, as mothers always mourn,

Yet, did not seem to wish for his return.

She laid him in the earth with decent pride,

For poor men's charity the means supplied;

And one poor bard to whom the child was known,

Inscrib'd these lines upon his humble stone:—

EPITAPH

Here sleep the relics of an orphan flower,

Crush'd by the brutal foot of lawless pow'r;

Another victim to the thousands slain

Within the mighty slaughterhouse of gain.

O! come ye kind philanthropists, who feel

The noblest int'rests in the people's weal,

Pause on this infant-martyr's new turn'd grave,

Swear to emancipate the British slave;

Tell the oppressor, that the widow's God,

Injustice, wields an all-avenging rod.

And if the pow'rs of human virtue fail,

The hand of heaven will certainly prevail.

JOHN

CRITCHLEY PRINCE.

1841. |

|

<>

|