|

SAMUEL

BAMFORD

(1788-1872)

Silk

weaver, radical, poet

and

participant in the

"Peterloo

Massacre" |

|

"The people

are born in masses, we may almost say; they live in masses; they work in

masses; they drink in masses; they applaud in masses; they condemn in

masses; they joy in masses; they sorrow in masses; and, as surely as that

Etna will vomit fire, they will, unless they be wisely and timely dealt

with, some day, act in masses.

"I do not undertake to say that here is a power capable alone, of

disarranging the present order of things; but I do say that I am of

opinion, that here, in time

will be found, mind sufficient to conceive, and will—aided by

circumstances—to give the first impulse to a movement, the like of which

has not been known

in England. These explosive elements—ever increasing—cannot be

continually tampered with, without producing their result."

Samuel Bamford

From....Walks in South Lancashire |

|

|

"Bamford is a brave, old, fighting soldier, who has borne the brunt of the

battle for much of the political liberty and social reform which we at

this day enjoy and accept as a matter of course, without reflecting that

other men have laboured, and we have entered into the fruit of their

labour."

Geraldine Endsor Jewsbury

――――♦―――― |

|

SAMUEL

BAMFORD—weaver, radical

and poet—was born at Middleton, Lancashire, on 28 February 1788. He

was the son of an operative muslin weaver, afterwards governor of the

Salford workhouse, and was educated at the Middleton and the Manchester

grammar schools. He learned weaving, and was later employed as a

warehouseman in Manchester; it was during this period that he made an accidental

acquaintance with Homer's Iliad and with the poems of Milton, and

his life was thenceforward marked with a passionate taste for poetry,

which brought forth fruit in the shape of several crude productions of

his own.

Bamford appears to have led a somewhat unsettled life in his

youth. He was for a short time a sailor in the employ of a collier

trading between Shields and London, he then

resumed his place in the warehouse and at length settled down as a

weaver. It was about this time that his first poetry appeared in print

and he became known in his district as one who had practical

sympathy with the difficulties of his class. Mrs. Gaskell, in her novel Mary

Barton, quotes a poem of his, beginning ‘God help the

Poor,’ to

illustrate the popularity of his verses with the Lancashire labouring

classes in their times of trial.

Resistance to trade oppression was the order of the day, and Bamford

went about with the endeavour to discover the true means of relief. He

had many of the peculiar talents necessary for the popular leader, while

averse to violence in any shape. He was brought into great public

notoriety on the occasion of that meeting of local clubs the dispersal

of which became known as the "Peterloo Massacre". It was

proved that Bamford's contingent to the meeting was peaceful and

orderly, and that his speech was of the same tendency. Yet he suffered

an imprisonment of twelve months on account of this affair. He

subsequently, by his personal influence alone, hindered the operations

of loom-breakers in South Lancashire. About 1826 he became correspondent

of a London morning newspaper, and having ceased to be a weaver by

employment, he incurred some dislike or distrust on the part of his old

fellow-workmen. Yet he always pleaded their cause as opportunity served,

even when, as a special constable during the Chartist agitation, he

incurred the downright enmity of his own class.

In 1851, or thereabouts, Bamford obtained a comfortable

situation—almost a sinecure, which raised above the prospect of want—as a messenger

for the Inland Revenue at Somerset House. But he became

dissatisfied with London life and people, and pined for his native

county; and after a few years of government employment he returned to his

old trade of weaving.

|

|

A LESSON FROM THE LOOM

AWHILE I watched my busy shuttle fly

Across the loom between the op'ning sheads;

And then I thought, e'en thus at my employ,

I may a useful lesson learn. Like threads

Our lives are woven in the web of time;

Our moments are the picks which pass between

The sheads. And if we make the woof sublime,

The piece, perchance, may please when it is seen

By the Great Master's ever-watchful eye;

And of His praise we each may get a share,

And His dear approbation yield in joy

A rich reward for all our toil and care.

And we may find that when life's piece is made

We all shall be by Him far more than paid!

David Lawton |

|

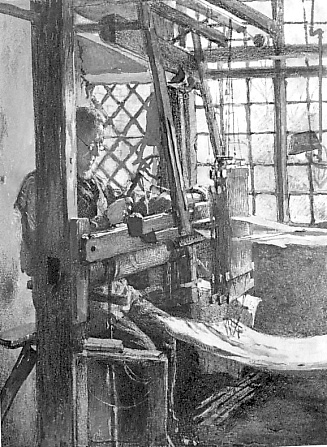

Hand-loom weaver. |

|

Samuel bamford died at Harpurhey, Lancashire, 13 April 1872, his last years having been provided for by the generosity of a few

friends. His public funeral was attended by thousands.

Bamford's fame rests both on his involvement in the history of radical politics and as a chronicler of social and political life in 19th Century

Lancashire. He was a prolific writer of leaflets and letters, as well as being a poet and a newspaper correspondent. His

autobiography, published in two volumes—'Passages in the Life of a Radical' (1839-41) and

'Early Days' (1848-49)—gives an authoritative and very readable account that reveals much of

the peasant way of life of the Lancashire artisan or craftsman in the

years immediately preceding the industrial era.

The high point of Bamford's involvement and influence in radical politics was between 1816 and 1821. The remainder of his long life—after

his quarrels with fellow radicals—is perhaps anticlimatic. His anti-Chartist attitudes and boundless egotism counted against him with many of his fellows.

Late in life he became increasingly cantankerous and jealous of his prestige as "the oldest living reformer" and as late as 1861 he believed government spies were keeping him under surveillance for his dangerous politics. By this time he had become one of "the prize platform bores of Lancashire political life", noting bitterly in his diary that someone else had been invited to give a lecture on parliamentary reform in Oldham Town Hall:

I was certainly much hurt to see that a young man, a young Parliamentary reformer, should be preferred to give a lecture on that subject whilst an old veteran like myself, who must have large knowledge of the subject from experience, and was on the verge of distress from want of encouragement in the way of lecturing, should be passed

by (May 13th 1861).

Despite this, Sam Bamford's early work is an important and accessible window on the 19th Century world.

|

|

Bibliography

Bamford's publications include:

-

An Account of the Arrest and Imprisonment of Samuel Bamford, Middleton, on Suspicion of High Treason,

1817;

-

The Weaver Boy, or Miscellaneous Poetry,

1819;

-

Homely Rhymes, 1843;

-

Passages in the Life of a Radical,

1840-4;

-

Walks in South Lancashire and on its Borders. With

Letters, Descriptions, Narratives and Observations Current and Incidental,

1844;

-

Tawk o'Seawth Lankeshur, by Samhul

Beamfort, 1850;

-

Life of Amos Ogden, 1853;

-

The Dialect of South Lancashire, or Tim Bobbin's Tummus and Meary,

with his Rhymes, with Glossary, 1854;

-

Early Days, 1849, 1859;

-

Homely Rhymes, Poems and

Reminiscences, 1864.

|

――――♦――――

|

"....Samuel Bamford, a man of Herculean mould, iron will, and indomitable

energy, whose 'Passages from the Life of a Radical' reveal the sufferings

he had endured, and the penalties he had incurred on behalf of his

political faith. He spoke his thoughts with fearless straightforwardness,

and was too earnest in all he said or did to study refinement in manner or

persuasiveness in speech. Underneath all this, however, there lay a gentle appreciativeness of all that was chaste and elevated in song or nervous in

composition; and his admiration of Prince's powers, though tempered by a

severe critical judgment, was always genial and unrestrained."

Bamford's visits to the 'Poets' Corner' were only occasional, for he

lived at Middleton, six miles from Manchester; but when he, Prince, and Rogerson met, the interchange of thought and sentiment was both

interesting and instructive. The latter sad days of Bamford were

alleviated by the kind consideration of a few friends, and he lies in the

churchyard of Middleton, where a 'monumental bust' distinguishes his

grave."

Lithgow—"The Life of John Critchley Prince",

Chpt. III. |

|

". . . . Directing my steps to the northward of my dwelling, I first

paused on gaining the summit of the highway across the township of Thornham, near Middleton, and looking around, I felt that a few minutes

would not be mis-spent in glancing over the bold and interesting scene

which was spread out before me. Going forth to note the brief joys and

sorrows of my fellowman, could I feel less than admiration and

thankfulness at the prospect of the goodly land which his beneficent

Creator had spread out for his habitations. To the west are the hills and

moors of Crompton, the green pastures year by year, cutting further up

into the hills; the ridge of Blackstone-edge, with Robin Hood's bed,

darkened as usual by shadows; whilst the moors, sweeping round to the

left, (the hills of Caldermoor, Whitworth, and Wuerdle) bend somewhat in

the form of a shepherd's crook around a fair and sunny vale, through which

the Roche flows past cottages, farms, and manufactories. Such is the scene

before us, fair and lovely at a distance, mute to the ear and tranquil to

the eye—like a cradle below the hills, where the bright day reposes amid

sweet airs and cooling streams. So much for the landscape before us; now

then, for the closer realities of our task. . . ."

The vista described by Bamford as he sets out on his 'Walks

Among the Workers.'

Samuel Bamford...."Walks in South

Lancashire." |

|

LINES TO A PLOTTING PARSON.

COME over the hills out of

York, parson Hay;

Thy living is goodly, thy mansion is gay;

Thy flock will be scattered if longer thou stay,

Our shepherd, our vicar—the good parson Hay.

Oh, fear not, for thou shalt have plenty indeed,

Far more than a shepherd so humble will need;

Thy wage shall be ample—two thousand or more,

Which rent and exaction will bring to thy store.

And if thou should'st wish for a little increase,

The lambs thou may'st sell, and the flock thou may'st

fleece;

The market is good—the prices are high—

And butchers are ready with money to buy.

Thy dwelling-house pleasantly stands on the hill,

The town lies below it, all quiet and still;

With a church at thine elbow for preaching and pray'r,

And a rich congregation to ponder and stare.

And here, like a good loyal priest, thou shalt reign,

The cause of thy patron* with zeal to maintain;

The poor and the hungry shall faint at thy word,

As thou threatens with hell in the name of the Lord.

Samuel Bamford

* The Archbishop of Canterbury.

|

EPITAPH ON DR. FORSTER, LATE

VICAR OF ROCHDALE.

Full three feet deep beneath this stone

Lies our late Vicar Forster,

Who clipp'd his sheep to'th' very bone,

But said no Pater Noster.

By ev'ry squeezing way, 'tis said,

Eight hundred he rais'd yearly:

Yet not a six-pence of this paid

To th' Curate――this looks

queerly!

His tenants all now praise the Lord

With hands lift up, and clapping,

And thank grim death, with one accord,

That he has ta'en him napping.

To Lambeth's Lord now let us pray,

No Pluralist he'll send us;

But should he do't, what must we say

Why――Lord above defend us!

Tim Bobbin

|

|

". . . . Here must be left behind the open fields, the sunny hill

sides, the garden plots with their stray flowers; the clear springs,

rilling by hedges and down rush-crofts, and shorn pastures, are no longer

to be noticed; but, instead of them, we see a multitude of human dwellings

crowded round huge factories, whose high taper funnels vomit clouds of

darkening smoke. . . . Poverty was increasing on all hands, and the people

were getting into a worse condition every week. A collector of rents

said people were crowding by two and three families into one house; they

could not pay rents for entire houses, and nearly all the workers, who

could raise money enough, were leaving the country. . . .

Pawnbrokers were crowded up with articles pledged by the poor; such

quantities had never been taken in before in the same space of time.

Much of their best clothes and bedding had been deposited long ago, and

now they were in the habit of bringing their meaner parts of dress for a

little present aid. Handkerchiefs, caps, pinafores, and aprons, they

would now pledge for a sixpence or a shilling. . . ."

Bamford describing conditions in Oldham, ca. 1841.

Samuel Bamford...."Walks

in South Lancashire." |

|

SAM BAMFORD

BORN 28TH FEBRUARY, 1788. DIED 13TH APRIL, 1872.

―――♦―――

|

|

TH' owd

veteran brid's toppled deawn fro' his pearch,

He'll charm us no more wi' his singing';

His voice has been hushed i'th' melodious grove,

Wheer feebler voices are ringin'!

He sang in his youth, in his green owd age;

An' he sang when i' monly prime;

Then, loike other warblers, he meaunted aloft,

To a fairer an' sunnier clime.

He sang fifty year sin', ere some o' us brids

Had managed to creep eawt o'th' shell;

An' sweetly an' grandly he poiped i' thoose days,

As th' owd Middletonians can tell!

Unloike other warblers an' songsters o'th' grove,

He ne'er changed his fithers, nor meawted;

For th' lunger he lived, an' th' harder he sung,

An' faster these ornaments spreawted.

He wur dragg'd fro' his nest once, at th' dead-time o'th' neet,

An' him an' his mate had to sever,

But it ne'er made no difference to him—not a bit,

For he sang just as sweetly as ever.

He warbled his notes in his own native shire,

When his pearch wur surreaunded wi' dangers;

An' he ne'er changed his tune when he'rn hurried awa

An' imprisoned 'mongst traitors an' strangers.

Owd Sam seldom flattered wi' owt 'at he wrote,

But for truthfulness allus wur famed;

When he feawnd ther' wur owt needed smitin', he smote,

An' cared nowt whoa praised or whoa blamed.

An' they wur songs, wur his,—not that maudlin' stuff;

Would-be poets spin eawt into rhyme;—

Ther's a genuine ring i' what great men sing,

Summat sweet, summat grand, an' sublime! |

|

|

He warbled when Waugh wur a fledglin' i'th'

nest,

An' had ne'er had a thowt abeawt meauntin';

An' young 'Lijah Rydin's had hardly begun

To give us his "Streams fro' th' owd Fountain."

Th' owd loom heawse i' Middleton rang wi' his notes,

An' his shuttle kept toime to his songs,

Ere he led up his neighbours to famed Peterloo,

To deneaunce what they felt to be wrongs.

He sang when his mate drooped away at his side,

Not a song o' rejoicin' or gladness,

But a low, plaintive dirge, softened deawn an' subdue

Wellin' eawt ov a heart full o' sadness.

He sang, too, when th' spoiler bore off his lone lamb,

Tho' his heart wi' deep sorrow wur riven;

Still he didn't despair, for he'd faith to believe

'At his dear ones had gone up to heaven.

He sang when th' breet sunshine illumined his path,

An' th' fleawers wur o bloomin' areawnd;

An' he sang, too, when th' storm-cleawds coom sweepin'

along,

An' threatened to crush him to th' greawnd.

He sang when his een had grown tearful an' dim,

An' his toppin' had turned thin an' grey;

An' th' muse never left this owd veteran bard,

Till Death coom an' took him away.

Thus he sung till he deed, an' his soul-stirrin' strains,

Never failed to encourage an' bless;

For he loved to rejoice wi' thoose hearts 'at rejoiced,

An' sorrow wi' thoose i' distress.

God bless him, an' iv ther's a spot up aboon,

Wheer dwell th' noble-minded an' pure,

Wheer th' songsters are gathered to strike up a tune,

Th' owd brid's perched amongst 'em we're sure!

Samuel Laycock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Samuel Laycock |

Ben Brierley |

John Critchley Prince |

|

THE

POET AT THE

GRAVE OF HIS

CHILD.

The Poet here

alluded to, is my friend Mr. Samuel Bamford, of Middleton, a

gentleman possessing high poetical powers, which, had

they been more

extensively cultivated, would have made him one of the most eminent, if

not the most eminent of our Lancashire Bards. |

|

A

BARD

stood drooping o'er the grave

Where his lost daughter slept,

Where nothing broke the stillness, save

The breeze that round him crept;

And as he plucked the weeds away

That grew above her slumbering clay,

He neither spoke nor wept:

But then he could not all disguise

The sadness looking from his eyes.

Indeed, it was a fitting tomb

For one so young and fair,

Where flowers, as emblems of her bloom,

Scented the summer air.

The primrose told her simple youth,

The violet her modest truth;—

Thus had a father's care

Brought the sweet children of the wild,

To deck the head-stone of his child.

Around that spot of hallowed rest

Grew many a solemn tree,

Where many a wild bird built its nest,

And sung with constant glee;

And hills upreared their mighty forms

Through Summer's light and Winter's storms;

And streams ran fresh and free,

Through many a green and silent vale,

Kept pure by heaven's untainted gale.

I looked upon the furrowed face

Of that heart-breaking sire,

Where I, methought, could plainly trace

The spirit's fading fire;

For he had stemmed the tide of years

In care, captivity, and tears;

And yet he touched the lyre

With cunning and unfailing hand,

For freedom in his native land. |

|

|

But now the darling child he had,

The last and only one,

Which always made his spirit glad,

From earth to heaven had gone,

And left him in his hoary age

To finish life's sad pilgrimage;

And, as he travelled on,

To soothe the sorrows of his mate,

And brood upon his lonely fate.

How oft together did they climb

The steep of Tandle hill,

And pause to pass the pleasant time

Beside the mountain rill;

Then he would read some cherished book

Within some leafy forest nook,

All cool, and green, and still:

Or homeward as they went along,

Sing of his own some artless song.

Such were the well-remembered themes

That told him of the past,

And well- might these recurring dreams

Some shade of sadness cast:

Those hearts whose strong affections cling

Too closely round some blessed thing,

Too often bleed at last,

When Death comes near the stricken heart,

To tear its dearest ties apart.

True Poet! touch thy harp again,

As Was thy wont of yore;

Its voice will charm the sting of pain,

As it hath done before:

Husband, subdue a mother's sorrow,—

Father, expect a brighter morrow,

And nurse thy grief no more;

Man, bow thee to the chastening rod,

And put thy holiest trust in God!

John Critchley Prince |

|

――――♦――――

|

SAMUEL BAMFORD.

BORN FEBRUARY 28TH, 1788. DIED APRIL

13TH, 1872. |

|

THIS day a

warrior bowed his plume, and died;

This day a noble spirit, purified,

Hath pierced the shadows of terrestial night,

And sought enshrinement in the "halls of light."

His was no stagnant life who gives this day

Back to his God a spirit weaned of clay.

For LIBERTY he donned

his mail and casque;

The GODDESS blessing

with a smile his task.

He saw that smile irradiate the world

Ere yet he closed his eyes. Boldly unfurled

He the proud banner when the maid was young

For whom he battled, and whose praise he sung.

Nor fought a braver champion in the field

Where men for freedom bled and died. His shield—

"MY HOME—MY

RIGHT—MANKIND"—the

motto bore,

Which to the last, with sheen undimmed, he wore.

Thick were the blows which rang upon his mail;

Deadly the thrusts that pierced it; but the trail

Of vanquished pennon, and the droop of crest,

His valour brooked not. His a nobler rest.

Five times unhorsed, and dashed upon the field;

Yet called he not for quarter, nor would yield

To foes outnumb'ring. Quick to saddle sprang

He yet again,—again his armour rang.

As falls the storm against the stubborn oak,

So fell upon his breast the battle stroke;

As stands the rock that heeds not flashing sky,

So stood his soul, man's thunder to defy.

And thus contending in that 'sanguined fray,

A victor now, next moment driv'n to bay,

His arm relinquished not its manly thrust

Till lay the foe in ignominious dust.

Then home came he with chaplets on his brow,

To doff his mail and casque. The knightly vow,

To free his country from a galling yoke,

Fulfilled with honour, he his weapon broke.

And in the evening of his life he lay

Watching the closing of a glorious day;

And as the summer's sun sinks in the west,

So sank our hero to his quiet rest.

Peace to thy honoured dust! No lay of mine,

Old soldier! e'er can reach a worth like thine!

Sing thine own requiem in that noble song

Thy life hath writ. Such themes to thee belong.

Ben

Brierley.

April 13th, 1872. |

――――♦――――

|

The Times.

(22 April, 1872) |

|

THE LATE

SAMUEL BAMFORD.—The

funeral of Samuel Bamford, the Lancashire Radical, and author of the book

entitled Passages in the Life of a Radical, and other works, was

performed on Saturday. Mr. Bamford died at the age of 84 years, on

Saturday 13th inst, at Moston, near Middleton, having been born in

February, 1788. He lived to be a patriarch among Reformers.

His connexion with political life dates from 1816, when he became

secretary of a Hampden Club at Middleton, but at all times was opposed to

physical force movements and violence. Writing his Passages in the Life

of a Radical 30 years ago during the Chartist movement, he warned his

fellow working men against errors committed a quarter of a century before,

when a good many had suffered through the vanity of leaders, as well as

the wickedness of enemies, and counselled them to seek their objects

through honesty and simplicity in a peaceful agitation. Bamford had

good reasons for giving his advice. A stalwart Lancashire weaver, he

had commenced political life determined to follow this course himself,

yet, through attending the meeting at Peterloo, Manchester, which was

intended to be a peaceful meeting to petition for Parliamentary reform and

a repeal of the Corn laws, but ended up in a massacre, he was apprehended

for a breach of the law, convicted, and sentenced to 12 month's

imprisonment. Since the period at which he wrote his book, Mr.

Bamford had lived a quiet and retired life, and through the liberality and

benevolence of a number of private individuals, he was supplied with the

means of passing the last 20 years of his life in comfort, though by no

means luxury. Towards the close of his life he had been made an

honorary member of the Manchester Literary Club, and it was through the

instrumentality of this club club that a committee was formed to honour

him with a public funeral. The Bishop at Manchester was invited to

conduct the funeral service, but was prevented by previous and unavoidable

pre-engagements. Writing to Mr. Haworth, the secretary of the

committee, his lordship says:—"Manchester, April 18,1872.—Sir,—I am

engaged to hold a confirmation of Saturday, the 20th, at 3 o'clock p.m.,

at Stand; so that I cannot take part in the ceremonial to which you invite

me. I am afraid, too, that it may wear too much the form of a

political demonstration for me befittingly to have borne a share in it,

even if I had been disengaged. Not that I consider 'politics' in the

highest sense of the word—an interest in what tends to promote the

commonweal—to be an interest alien from, or contrary to, the proper

functions of a minister of Christ; and I could have cordially united in

honouring the man who wrote Passages in the Life of a Radical, and

who, in that remarkable

book, avowed 'that nation to be the only |

party he would serve' (ii., p.235);

tried to teach the rich and poor, employers and employed, that they had

'been all in error as respects their relevant obligations' (i., 281);

sought to bring all classes together on the basis of mutual sympathy and

co-operation; believed that instead of wishing to create sudden changes

and to overthrow institutions, it were better that ignorance alone were

pulled down' (i., 279); and maintained that self-control and

self-amendment of the individual were the only solid 'basis of all public

reform' (ibid). If I had attended Samuel Bamford's funeral I should

have liked to have heard the last chapter of the first volume of his

memoirs read over his grave. It contains counsels that England seems

to me emphatically to need just now.—I remain, Sir, your faithful servant,

J. MANCHESTER.—Mr. John H. Haworth." The funeral procession entered

Middleton about 4 o'clock on Saturday afternoon, where many thousands of

visitors had collected from the surrounding districts to pay due honour to

the occasion. About 300 or 400 persons preceded the hearse walking

five abreast, after whom came mourning coaches and nearly 40 other

carriages of various descriptions. The church was crowded in every

part, the service being conducted by the Rev. Waldegrave Brewster, the

rector, who, in consequence of the coldness of the weather, read most of

the service within the building. The rector was good enough to

follow the suggestion of Bishop Fraser, by reading various extracts from

Bamford's Life of a Radical. The chapter referred to by his

Lordship is one appealing to working men and Chartists to show no

violence. "Come to thine own bosom and home and there commence a

reform, and let it be immediate and effectual." "It is true that the

middle and upper ranks have scarcely been just towards you; they have not

cultivated that friendship of which you are susceptible, and more worthy

than they. Had they done so you would not have been in the hands you

now are. But you can look above this misdirected pride and pity it.

The rich have been as unfortunate in their ignorance of your worth as you

have in the absence of their friendship. All ranks have been in

error as respects their relative obligations and prejudice has kept them

strangers and apart." The interesting proceedings inside the church

were followed by only a brief ceremony in depositing the coffin in its

last resting place. The church and burial ground being seated on an

eminence immediately overlooking the town, the thousands of people

collected there formed an exceedingly picturesque spectacle as witnessed

from the streets. The weather, though cold, was exceedingly fine,

and the proceedings passed off with the decorum benefiting such a

melancholy occasion. |

――――♦――――

|

|

|

|

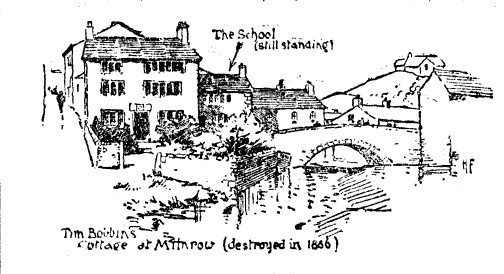

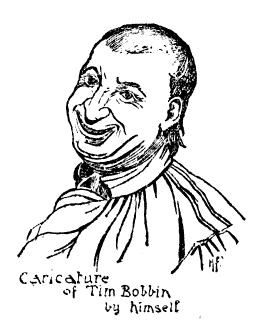

Tim Bobbin ―

two illustrations appearing in

The Manchester Times, 16th October, 1891. |

|

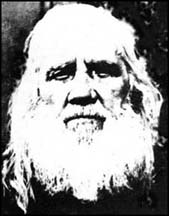

|

Painting, oil on board,

identified by the Rochdale Museum and by auctioneers Bonhams

as a self-portrait of

Tim Bobbin.

(By courtesy of David Coomber & Carole Bent,

"Celtic Connection.") |

――――♦――――

|

Manchester City News

19th July, 1924.

SAM BAMFORD.

――――♦――――

Romance of a Man of Action.

By James Middleton. |

|

The literary reputation of Sam Bamford

rests securely upon two autobiographical works that he wrote—one "Early

Days," the other "Passages in the Life of a Radical." The first of

these dealt with his experiences as boy and youth; the second is a record

of his career as a political reformer. These two books made a

notable contribution, not only to Lancashire authorship, but also to

English literature. Of the two "Early Days" is preferable for style,

whilst the "Passages" must be assigned pre-eminence for varied and

sustained interest. The two books are beautifully written in the

purest English and the choicest prose.

Early Adventures.

But whilst he was distinguished as a man of letters, and

dallied with verse, some of it good enough to be called poetry, he was

also a man of action. He was born into a brisk time. His

period might properly be described as Peterloo: Before and After. He

was born at Middleton, near Manchester, in February 1788, and, as he

remarked, he and the world came into trouble together. That so quiet

and remote a place should have found trouble only shows how much trouble

there must have been about. Bobbie Burns and the French Revolution

had put into circulation ideas which disturbed the ordinary rim of things.

The working classes were stirred to a quick interest in their own unhappy

condition. Hampden Clubs were formed: one at Middleton, to which

Bamford was appointed secretary. Into this welter Bamford was born.

It must have been a strange birth, for he says of it, "I was born a

Radical." By that token a stormy career awaited him.

As a boy he was adventurous. There was warm blood in

his veins, which he did not inherit from his mother, for she was a saint.

His father, in early manhood, was as merry a soul as Old King Cole.

He was given to drinking, and in his cups was ever ready to fight.

But the Wesleyans laid hold of him, and he became a changed man and

remained so.

As to the boy, his real adventures began with the music of a

fife and drum and a handful of ribbons. So fascinated was he that he

took the shilling and as much ale as he wanted, and was technically of the

Army. Curiously, he was never called up, and so missed military

service. As the Army failed to claim him he turned his thoughts to

the sea, and signed a contract to serve with a coasting vessel which

traded between South Shields and London. It was a change which

enabled him to see London, with its historical memorials. After

half-a-dozen voyages each way he tired of the life, deserted his ship, and

made for home and Middleton. He walked it. Had it not been for

playing the "old sailor" and dodging the marines and the press-gang

people, might have landed in prison even earlier than he did.

The Young Radical.

Being "born a Radical," he began to associate with people of

that order. The Hampden Society hired a chapel where regular

meetings were held. The members were concerned with such ordinary

things as an extension of the franchise and a change in the system of

parliamentary representation. The authorities, with the impulsive

timidity of autocratic governments, became alarmed, suspended the Habeas

Corpus Act, and forbade the holding of public meetings. This was a

challenge which the mildest reformer was bound to take up. Secret

meetings were held, sometimes in the dells of Tandle Hill late at night or

very early in the morning. There were drillings and marchings, and

pikes were to be seen. Bamford went in and out amongst these

preparations, exercising a restraining influence upon the people.

There were secret societies and spies, and plots. One day a young

man, a stranger, came to see Bamford to tell him that a plot was on foot

to make a Moscow of Manchester that night by burning it to the ground.

A light would shine in the heavens as the signal to all the surrounding

districts to march straight to |

the city and take their due allocation. The young man

was sent away, and Bamford and old "Dr." Healey went to sleep at a

neighbour's house in preparation for an alibi. There was no light in

the heavens except a harmless round-faced moon. These were

adventures in which Bamford would not join.

In Prison.

But all his precautions did not save him from the attentions

of the authorities. Nadin, the head of the police, came in the

night, arrested him in his own house, and carried him off in irons to "The

Tribulatory," which was Bamford's name for the Salford gaol. He was

taken to London; brought up at Bow-street, remanded to Lord Sidmouth, Lord

Castlereagh, and the Privy Council. A second appearance before the

Council followed. Bamford acknowledged that he was a parliamentary

reformer, and always should be so until that measure was obtained; that no

circumstance or situation whatever would induce him to disavow his

opinions, and that he considered it the glory of his life to have merited

the name of a reformer, but had never advocated its obtainment by

violence. After five examinations Bamford was discharged on his own

recognisances.

Peterloo and Afterwards.

Then Peterloo occurred, with its cuts and bruises inflicted

by the swords of the yeomanry. Bamford was present as leader of the

Middleton contingent. That was enough for Nadin. The police

banged on Bamford's door, which was opened when they said who they were

and what they wanted. They entered the dark room, police and

soldiers. The drawers were rummaged, his box was explored, and all

his books and papers were tumbled into a shawl, to be carried away.

Handcuffs were ordered and put on. This is how Bamford describes the

scene:—

The order was given to move; my wife burst into tears. I tried to

console her: said I should soon be with her again. I ascended into

the street, and shouted "Hunt and liberty." "Hunt and liberty"

responded my brave little helpmate, whose spirit was now roused. One

of the policemen, with a Pistol in his hand, swearing a deep oath, said he

would blow out her brains if she shouted again." Blow away was the

reply. "Hunt and liberty." "Hunt for ever."

The woman's brains remained in their proper place, the

procession moved off, and Bamford the Reformist was on his way to gaol

again.

This time he found himself a prisoner in Lincoln Castle,

where he became came seriously ill. His wife was allowed to visit

him, and a room was set apart for their joint accommodation. At the

end of the agreed period she returned to Middleton, but as Bamford's

health grew worse she returned to Lincoln Castle to nurse him back to

health. Under her wifely treatment he soon recovered his wonted

strength. When the term of his twelve months' imprisonment ended he

was released, and once more recognisances of rood behaviour were entered

into. Then it was the open street of a cathedral city, and after

that the open country. They were a long way from home, means of

travel were not plentiful; but Bamford and his wife were young and of a

cheerful spirit. They started to walk home.

It was in the merry month of May, and the weather appears to

have been bright and sunny. They passed through some of the most

beautiful parts of our lovely country. As they crossed, the wold

near the Yorkshire border they saw "the wind of heaven—the spirit of life"

They were only thirty three years of age, and all the toil and suffering

they had passed through all there was of endeavour and achievement, had

been accomplished within about fifteen years. Bamford had still his

autobiography to write and of it he made a wonderful story of love and

adventure. |

――――♦――――

|

TIM BOBBIN' GRAVE. |

|

I stoode beside Tim Bobbin' grave

'At looks o'er Ratchda' teawn;

An' th' owd lad 'woke within his yerth,

An' sed, "Wheer arto' beawn?"

"Awm gooin' into th' Packer-street,

As far as th' Gowden Bell;

To taste o' Daniel's Kesmus ale."

TIM.—"I cud like o saup mysel'."

"An' by this hont o' my reet arm,

If fro' that hole theaw'll reawk,

Theaw'st have o saup o'th' best breawn ale

'At ever lips did seawk."

The greawnd it sturr'd beneath my feet,

An' then I yerd o groan;

He shook the dust fro' off his skull,

An' rowlt away the stone.

I brought him op o deep breawn jug,

'At o gallon did contain;

An' he took it at one blessed draught,

An' laid him deawn again!

Sam Bamford. |

――――♦――――

|

Manchester City News.

22nd August 1925.

The Home at Charlestown.

――――♦―――― |

|

MR. JOSHUA HOLDEN

writes:—I believe I am correct in stating that Bamford wrote both

"Passages in the Life of a Radical" and "Early Days" while residing in a

little cottage in Charlestown, Blackley. Part of this hamlet still

remains, but the cottage in which Bamford lived has long ago disappeared.

A steep hill, much steeper than the present Charlestown Road, led from the

turnpike road up to Charlestown.

Bamford's cottage was the last on the right, and immediately

behind was a deep dell in which was a fern-festooned well, which never

failed in its supply. This dell now forms part of Boggart Hole

Clough. It was from this cottage, seventy-three years age, that

Bamford, at the age of sixty-four, went to London to take up an

appointment in Somerset House. He soon tired of his appointment and

pined for his old environments.

It was probably while sitting on one of the forms in a London

park that he wrote or conceived the idea, for his "Farewell to My

Cottage." In the London park, he sees strange children, and compares

them with those who loved him and Mima, and who did so many little acts of

kindness for them. Proctor, in "Memorials of Bygone Manchester,"

refers to this poem, and says that it was probably the last which Bamford

wrote. He also states that Bamford once expressed a desire that the

verses should be appended to a picture of his dwelling near "Boggart-Ho-Kloof."

This has never been done.

I enclose a copy, of the poem, and also a photograph of Charlestown

showing Bamford's cottage. I am looking forward, and doubtless many

others, to reading the "Looms of Destiny," for it would be difficult to

find a more varied life than that of Samuel Bamford for the groundwork of

a good story.

|

――――♦――――

|

FAREWELL TO MY COTTAGE. |

|

FAREWELL to my cottage, that stands on the

hill,

To valleys and fields where I wander'd at will,

And met early spring with her buskin of dew,

As o'er the wild heather a joyance she threw;

'Mid fitful sun beamings, with bosom snow-fair,

And showers in the gleamings, and wind-beaten hair,

She smil'd on my cottage, and buddings of green

On elder and hawthorn and woodbine were seen—

The crocus came forth with its lilac and gold,

And fair maiden snowdrop stood pale in the cold—

The primrose peep'd coyly from under the thorn,

And blithe look'd my cottage on that happy morn.

But spring pass'd away, and the pleasure was o'er,

And I left my cottage to claim it no more.

Farewell to my cottage—afar must I

roam,

No longer a cottage, no longer a home.

For broad must be earned, though my Cob I resign;

Since what I enjoy shall with honour be mine;

So up to the great city I must depart,

With boding of mind and a pang at my heart.

Here all seemeth strange, as if foreign the land,

A place and a people I don't understand;

And as from the latter I turn me away,

I think of old neighbours now lost, well-a-day,

I think of my cottage full many a time,

A nest among flowers at midsummer prime;

With sweet pink, and white rock, and bonny rose

bower,

And honeybine garland o'er window and door;

As prim as a bride ere the revels begin,

And white as a lily without and within.

Could I but have tarried, contented I'd been,

Nor envied the palace of lady the queen.

And oft at my gate happy children would play,

Or sent on an errand well pleased were they;

A pitcher of water to fetch from the spring,

Or wind-broken wood from my garden to bring;

On any commission they'd hasten with glee,

Delighted when serving clear Ima or me—

For I was their "uncle," and "gronny" was she.

And then as a recompense sure if not soon,

They'd get a sweet posy on Sunday forenoon,

Or handful of fruit would their willing hearts cheer;

I miss the dear children—none like

them are here,

Though offspring as lovely as mother e'er bore

At eve in the park I can count by the score.

But these are not ours—of a stranger

they're shy,

So I can but bless them as passing them by;

When ceasing their play my emotion to scan,

I dare say they wonder "what moves the old man."

Of ours, some have gone in their white coffin shroud,

And some have been lost in the world and its crowd;

One only remains, the last bird in the nest,

Our own little grandchild, the dearest and best.

But vain to regret, though we cannot subdue

The feelings to nature and sympathy true,

Endurance with patience must bear the strong part—

Sustain when they cannot give peace to the heart;

Till life with its yearnings and struggles is o'er,

And I shall remember my cottage no more.

Sam Bamford. |

――――♦――――

<>

|