|

|

|

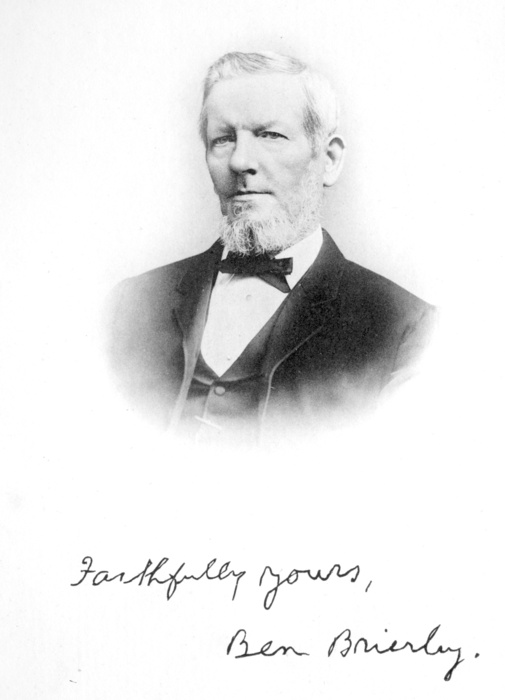

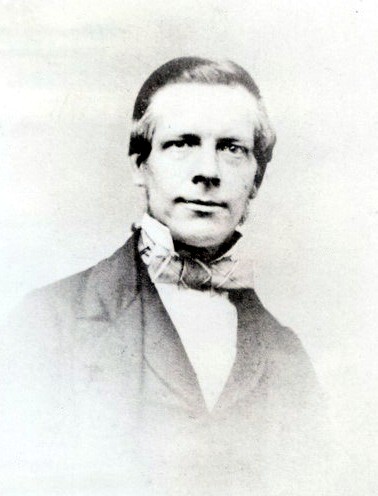

BENJAMIN

["Ben"] BRIERLEY (1825–1896),

poet and novelist.

Photographed

June, 1894. |

Ed.— in addition to the pieces

that appear below, JAMES DRONSFIELD

has written a good biographic sketch of Brierley, which

appears as the

Preface to AB-O'TH-YATE

SKETCHES, Vol. I., while Brierley

himself provides a similar piece in the chapter entitled "Failsworth"

in AB-O'TH-YATE

SKETCHES, Vol. III.

――――♦――――

From

THE OLDHAM CHRONICLE

June 27, 1925.

BEN BRIERLEY CENTENARY.

|

|

|

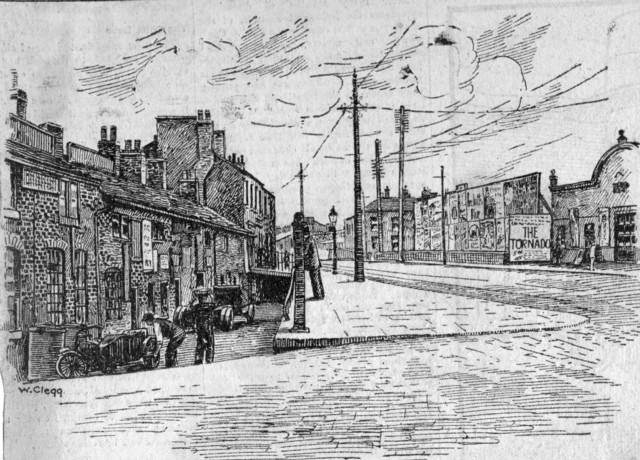

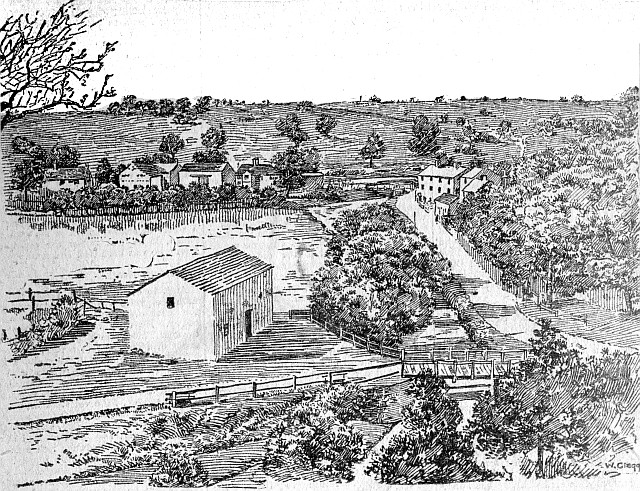

BEN

BRIERLEY'S BIRTHPLACE, AS SEEN TO-DAY. It is on Oldham Road,

Failsworth, between the Pole and the Canal Bridge. The actual house,

marked by a tablet, is the last on the left. Brierley wrote:—"This

hole (the space between the houses and the wall supporting the

raised footpath), called 'The Rocks' from its being walled with

stone, is wedge-shaped, and I was placed at the thin end. The upper

portion of the house has since been rebuilt and now forms a dwelling

of itself—the lower part now serving as a foundation." |

BEN

BRIERLEY was born at

Failsworth on June 26, 1825. He is therefore entitled by lapse of

time to have his centenary celebrated, and his friends and

neighbours have decided that it shall be. He was born at "The Rocks"

in Failsworth, but it must not be supposed that "The Rocks" stands

for some imposing residence. It was a mean looking birthplace,

scarcely fit for anyone to be born in. It was a bit of sunken

roadway left low down by the construction of the turnpike road to Austerlands which had to be carried over the Rochdale canal at a

higher level. A row of houses formed one side of the gully, facing a

heavy stone retaining wall which supported the upper road. Hence its

name. Ben was born in the end house, the dead end of what he

afterwards referred to as "this hole." The house is still there and

so is the gully and may seen to this day. A higher storey was added

to the house which opens on to the present highway. The place is

marked by a tablet affixed to the wall.

|

"Swinging, at first drowsily, as if they were not quite roused from

sleep, but growing louder and quicker as they opened their eyes, the

bells began their welcome to the New-born Year. How they chased each

other in the race of harmony! The little ones sometimes tumbling

over the big ones, the latter growling good-humouredly betimes at

the eagerness of their forward companions, and putting in their

ding-dongs like veterans who had rung-in many a New Year, and knew

what it was to go about their work soberly. But merrier still the

young ones grew, and got so frolicsome in their madcap glee, that

the old ones, as if resolving not to be outdone by their juniors,

fling away discipline altogether, and lumber away in the race like

giants at child-play. Away they go, helter-skelter, little and big,

old and young, light tones and deep, making such a row in that

bedlam of a steeple, that the spiders, frightened out of their wits,

retreat to the farthest nooks of their several lairs, and ponder

over the remains of murdered flies that strew the floors of their

airy charnel-houses."

New Year bells, from

Christmas at Ringwood Hall |

Ben was well provided for in the important matter of parents. His

father, James Brierley, had been a soldier, and had fought at

Waterloo, having two years added to his term by reason of that

service, with a pension increased accordingly. He was present as a

plain citizen at Peterloo as many other Failsworth people were. It

is probable that Ben inherited his erect figure and quick step from

his father. It is equally probable that he derived from his mother

his kind and gentle disposition. She had a wonderful influence over

the boy. She had a splendid voice and sang much in the home. He had

great reverence for her. Her name was Esther and so devoted was he

to her that he vowed he would never marry any woman unless she was

called Esther. And it was so, for in the fullness of time Esther was

found waiting for Ben.

Education.

Born in pre-education days his chances of schooling were of the

scantiest. There was a school round the corner in Pole Lane to which

he went. He was evidently an intelligent boy and a trier. He says of

himself at that age: "I was an apt pupil and rose from the A,B,C's

before I was five years old. I took the first prize in spelling. The

word to be spelt was 'victuals,' the prize three marbles. Victuals

was ever a hard word to spell and particularly at the time when Ben

was going in five. The marbles would be welcome even to a child so

young. It is worth noting that this facility in spelling

remained with him, and it was considered by good judges that his

spelling of dialect words was most correct. Possibly

Sam Bamford

might on some counts have run away with the marbles. Little Ben

stayed on at the Pole Lane Academy till Coronation Day when William

IV was crowned but left school the day after and never went to day

school again.

|

|

|

|

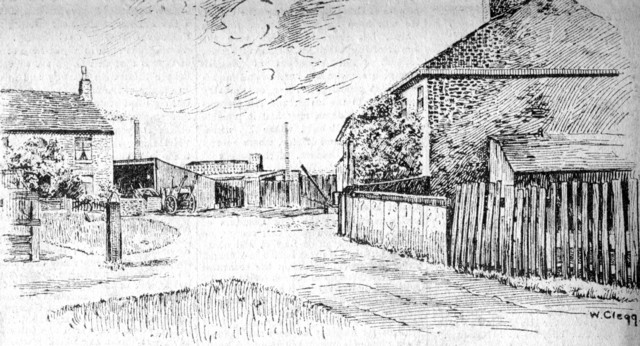

Bardsley Fold, off Lord Lane, Failsworth―Brierley's

Walmsley Fowt. The home of Ab o'th Yate

is on the right of the drawing. |

|

The family "flitted" to Hollinwood and one day a week he was put

under tuition at a Sunday School held in a garret in Bower Lane,

conducted by some excellent people irreverently nicknamed "Ranters,"

being somewhat loud in their declarations of faith. He was passed

into the Bible class before he had gone through the New Testament,

that being the order of the promotion. He took to reading, and

bought "Cleaves's Gazette," one penny weekly. Noticing this, a

reading man lent him "Pickwick Papers." He helped to form a mutual

improvement class and on returning to Failsworth joined a similar

class, there he read Burns and Byron, bought a Byron tie and took to

cultivating melancholy for the first and last time in his career. Brierley often remarked that he "had to make his own ladder before

he began to climb." But he did climb and became one of the goodly

company of the great self-taught.

Literary Instincts.

Brierley felt the stirrings within, which impelled him towards

literary effort. He was moved towards poetry and indited verses "On

the death of a little hen." That poem is not now in print and

probably never was. He tried drama and was driven to write a

play which must needs be a tragedy, "Marinello, the Monk," which was

staged under the direction of the author. There were daggers in the

play, and Brierley took one of the more dangerous parts. So well did

he act that Esther threatened to have no more to do with him as he was

"sich a bad un." This and other plays were staged upon three planks,

a window bottom and the top of a staircase, and the "tea-fed audience

were delighted."

|

"Th' fowt begun a-stirrin'.

Th' childer i' white—bless the'r little souls!—flyin'

abeaut like little angels. An' owd men i' black

cooats ut they'd worn eaut o' recollection, an' some, aw

dar'say, wur the'r feythers afore 'em, wur tryin' to put

th' childer i' a double row for t' receive th' Prince,

but it wur moor nur they could manage for a while,

becose th' childer mit ha' had wick-silver i' the'r

shoon. At last they geet 'em summat like streight,

an' as they o stood up, every little lass had a posey i'

her hont, an' it wur enoogh to mak' a lad wish he're a

wench, for a grander seet couldno' be pictur't.

Ther mony a mother lookin' eaut at th' chamber window,

tryin' to hide summat ut trembled in her e'en, as hoo

looked at a bit o' white deawn below. Ther one o'

eaur Ab's childer amung th' lot; an' th' owd gron-rib

thowt th' wench's mother mit ha' put a bit moor blue in

her starch, for th' frock wur th' colour of a primrose.

Mother-in-law agen! aw thowt. Dowter never con

pleeas."

Welcoming the Prince of Wales, from

Ab-o'th'-Yate

Sketches. |

Failsworth itself was a poor sort of place, it had just been rescued

from the heath. The soil was thin and surly, and swampy in places,

more fit to carry rushes than corn. Agriculture was in its primitive

stage. The farmsteads that were scattered at wide intervals over the

land were what would now be called "milk farms," with pigs and

poultry to make out with. The farmhouses were set in folds or, in

dialect "fowts," a term even now in common use. There are still

Hardman Fold, Fletcher Fold, and Bardsley Fold. The last named was

rechristened by Brierley for his own literary purposes and became

the famous "Walmsley Fowt," the abiding place of "Ab o'th Yate." The

few cottages that clustered in and about these fowts housed such

labourers and craftsmen as were needed for the services incidental

to farm life, carpenters, builders, smiths and the like. The other

principal industry was that of silk weaving carried on in cottage

loom houses. The people were of rugged speech and rough in manner. They had practically no education, and had to make the best they

could of their natural intelligence. They were given to such sports

as cock-fighting, dog fighting and bull-baiting with an occasional

bout of bear-baiting. Their social recreations centred largely in

the village ale-house and the "hush shop," which

flourished by hiding its light within a brewing mug.

|

|

|

|

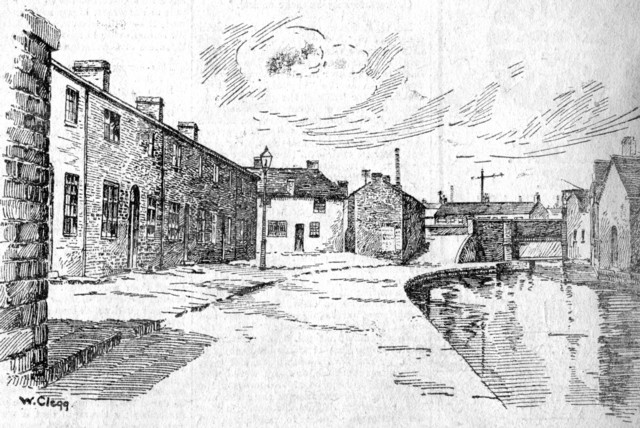

TH' CUT SIDE, off Hollins Road. Brierley lived in the

third house from the far end of the row for many years. Describing

this spot he writes:—"There was a farmhouse on the opposite side of

the canal. A spacious orchard, the trees in which were covered in

bloom, ran to the edge of the water. A thorn fence, well

grown, in which I looked for birds' nests was within a few yards of

the door. |

|

An Interesting Folk.

Into this community Ben Brierley was born; and considering what he

was to be and to do he could hardly have been born in a better

place. These men and women, their occupations and recreations, their

habits and associations, were the raw material of the literature

that was to be. He realised that the proper place to start the

business was where he happened to be. The men dressed in homespun or

moleskin, the women wore caps and bedgowns and shod themselves in

clogs. When the men went "a-buntin'" they brought out their best

tall hat, blue swallow tail, with shining buttons, knee breeches,

and shoon clasped with buckles the colour of silver. These humble

folk supplied what the very modern novelist would call "life." Brierley arrived just in time to see the boggarts go, the very last

of them. Men they were in shadowy grey, turning to a rusty black,

who had dealings "wi th' owd lad" seen and not seen, heard making

noises with or without chains. Ben Brierley's friends being

superstitious believed in them, or, rather, were much afraid of

them. Witches, too, there were—seen and conversible—who killed

cattle with a look, and brought fever to the village with a

mysterious word. They were often bent and old, and feaw of face,

dressed dinghy, and leaned upon a crooked stick. Boggarts and

witches came in and out of these tales investing them with the

dread of the occult. Brierley did not invent them, he found them

there in the popular mind as things that were veritable.

First Venture.

Ben Brierley's first serious venture in literature was "A Day Out,"

which appeared in the "Manchester Spectator." It was an

unpretentious piece of writing, merely an account of a simple

journey of observation, a walk through the fields, along the brook

side, through sloughs into the Nook which he made his own; talks by

the way, refreshing, invigorating conversation; encounters with

characters whose discourse had a racy energy which is chiefly found

in the quiet place of the countryside. In this record we seem to get

the plan of Brierley's literary design.

|

It seems that Brierley's better half wrote up

her household accounts in chalk, on the back of the

kitchen door. Thus, when Ab decided to carry out an

audit of her expenditure . .

. .

"Aw're never betther puzzled i' mi life nur when aw looked o'er this

wooden shop-book, an' tried to mak' eaut th' meeanin' o'th' figures

ut wur on it. Aw knew ut a o meant a shillin', an' a hauve-moon

six-pence. Aw knew, too, ut a lung choak stood for a penny, an' a

short un for a haupenny; an' ut an x wur a farthin'. Aw could add up

th' whul lot, an' knew heaw mich it coome to. But what had th' brass

bin spent on? Theere wur th' rub! Aw should ha' to co' in mi client

to explain."

Ben Brierley,

The Owd Buttery Dur, or

Ab's Audit |

There are in it the same kind of people who move through his later

writings. Owd Israel, who was a "fizzer at telling a tale," and that

other man who could "smell a pa'son a fielt off," and the other one

who described bad ale as "brewed besoms." This first real attempt at

literature was welcomed by the "Manchester Guardian," the

"Manchester Examiner and Times," and the far-off "Saturday Review." Those who think of Brierley as a writer in dialect only should read

"A Day Out," and they would find that he had a good command of

excellent English. His short sketches were full of good writing. In

"The Jacobin" he displays true narrative power. It is based upon an

incident which occurred in "The Rocks" at the turn of the centuries

when Tom Paine flourished as a bogey, and had the distinction of

being burnt in effigy at frequent intervals, amid signs of popular

execration. A simple weaver was suspected of having in his

possession a copy of "The Rights of Man." He was visited by a

military personage who demanded that the book should be delivered up

to him. The man retired into the house and returned with a copy of

the Bible. "What is that?" said the man of the sword. "The only book

of the rights of Man that I read," was the reply. And the mob that

had caused this domiciliary visit was sharply rebuked.

The Dialect.

But it was in the dialect that Brierley did his best work. His

characters are always talking, and that in the vernacular. It is in

their conversation that they reveal themselves. Some of them use

strange words not to be found in any dictionary. The words are "whoamly,"

because they are "whoam-made" intended for domestic use and seldom

stray from the neighbourhood. Not only are the verbs singular but

the nouns also, and some words that do not perhaps belong to any of

the parts of speech. What a world of meaning can be thrown into "Theigher." How "gloppent" leaves one wondering. And "gullook"

can only be guessed at. "Seechin' for gawp seed" is a sentence that

is hardly amenable to ordinary parsing. "Keawer thi deawn while aw

pow thi yure" is difficult when written, impossible when spoken

except to the knowing ear. "Threapin', " "thrutchin'," "hutchin'

up," were terms in daily use which modern refinement has not yet

suppressed. Of these "gradely" is the most distinguished word. It is

of such words that the characters in Brierley's writings make up

their conversation.

|

|

|

|

DAISY NOOK, as seen from the Droylsden side. A

survey of Brierley's life and writings would be incomplete without

reference—pictorial or otherwise—to the still charming spot in the

Medlock Vale popularised by his tales and sketches. |

|

|

|

Meeting of the

Manchester Literary Club c. 1865.

Samuel Bamford is third from

the left,

back row; Brierley is seated fourth from the right,

centre row; Edwin Waugh is seated on

the extreme right. |

|

Lancashire Humour.

Brierley's strong point was his humour. It was the

Lancashire variety he dealt in, and that means particularly the

humour of the countryside. It was jovial and jolly. When

it laughed it opened its mouth and guffawed without thinking that it

might be ill-mannered. With Brierley it sometimes took the

form of the practical joke, often of the "biter bit " variety.

One of his most interesting characters was "Fause Juddy," a very

good fellow, who might, however, be easily taken in. This was

he who figures so amusingly in "Catchin' a Weasel," one of

Brierley's best tales. It turned on the occurrence of the

first of April. "Ab" himself, having been made into a "foo,"

set out to find another, and found an easy victim in Juddie.

The story is dramatically perfect. "Th' Boggart o' th' Stump"

is another rollicking sketch. The purchase of the stuffed

monkey and its installation on a stump by a field path might be

expected to provide fun. Joe and Bill stood and stared at they

knew not what. It was a hare, a cat, a scorpion, a cherubin,

all in turn. Then it was "Th' Owd Lad," and there was nothing

for it but flight. The same impression struck the vow-making

swain who left his trusting girl at sight of "Jacko," ran down the

hill, but not too far to prevent his calling out "Tak' her, Mesthur

Sattin, hoo mends stockins' ov a Sunday."

Dramatisation.

Brierley dramatised several of his stories, "Thistledown

Hall," "The Cobler's Stratagem," "Fratchingtons of Fratchingthorpe"

and "Insurin' his Life." But his greater success in this

direction was "The Layrock of Langleyside." As "The Lancashire

Weaver Lad" it succeeded in passing the ordeal of the legitimate

stage, being performed at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, Brierley

himself taking the part of the weaver. As an actor he showed

good talent and delineated his own characters in a realistic

fashion. Incidentally it illustrated at once his poetic merit

and an unsuspected musical ability. There is a song in this

drama which the weaver sings, with a chorus which calls for much

sprightliness from the singers. Here is a stave, or two:

|

Yo' gentlemen o' with yor heawnds and yor parks,

Yo' may gamble and sport till yo' dee-e,

Bo' a quiet heawse-nook, a good wife an' a book

Is more to the likin's o' me.

Aw care no' for titles, nor heawses nor lond,

Owd Jone's a name fittin' for me.

An' gie me a thatch wi a wooden dur latch

An' six feet o' greawnd when a dee-e.

Chorus:

Wi' mi pickers and pins

An' mi wellers to th' shins,—

My linderins, shuttle and yeald hook,

Mi treddles an' sticks,

Mi weight-ropes and bricks,

"What a life," said the weaver o' Well-brook. |

To the unskilled person the chorus is almost unreadable, certainly

unsingable, but Brierley could get out of it all that he had put

into it.

His mastery of the humorous spirit was shown in the sketches

which followed the discovery of "Ab o' th' Yate," perhaps his most

successful delineation. They went together to Blackpool, to

London, sailed to the Isle of Man, and visited the United States,

leading a rollicking life together. "Owd Ab" was both humorist

and philosopher, and these journeyings of his were tours of

observation in which he gathered up not so much information as

impressions. As a critic he could be very caustic. On

shams and hypocrisy of every shade and kind he was severe and, on

occasion, almost fierce, but he was of charitable disposition,

considerate, and tolerant of mere differences of opinion.

Honesty and sincerity he demanded.

Journalist and Novelist.

Brierley was associated with journalism and was sub-editor of

the "Oldham Times " for some years. He ventured into London as

most authors are tempted to do. Many of his sketches and some

of his novels, "Red Windows Hall" being one, appeared in the

supplement to the "Manchester Weekly Times." His big venture

was the publication of "Ben Brierley's Journal," which continued for

a period of sixteen years. It was a popular production.

Brierley's literary ambitions never soared very high. He was

content to turn into literature the simple lives and experiences of

the humble people he knew so well. He never wandered far away

from his own place either for his Lancashire subjects, characters or

plots. Geographically he covered little ground.

Middleton and Tandle Hills across to Bardsley and Littlemoss

embraced the whole of his country. Yet within this narrow

space he found the materials for half a score or so of goodly

volumes including a volume of poetry with the title of "Spring

Blossoms." He was a lover of Nature, fond of gardens and

flowers and the still life of the country. He delivered an

"Oration" to the Ashton-under-Lyne Horticultural Society. That

was in the day when orations were still a fashion.

As regards his position in Lancashire literature, Ben

Brierley was the middle figure of the Lancashire trinity standing

between Waugh and

Laycock. As a prose writer

he is not much below Waugh in merit, as a poet he does not come up

to Laycock. His achievement was that he took of the simple

things of humble life and put them in a literary setting where they

will be permanently enshrined. They are a record of things

that were. He has done for Failsworth in his own modest way

what Barrie did for Thrums and Hardy for Wessex. For this he

is to be had in affectionate remembrance.

――――♦――――

|

ANNIE,

ONLY CHILD OF BEN.

AND ESTHER BRIERLEY;

Born November 7th, 1856. Died June 13th,

1875. |

|

WE thought she

was our own for yet awhile;

That we had earned her, by our love, of Heav'n,

To be a life's comfort, not a season's smile,

Then tears for ever. "'Tis to be forgiven,"

We deemed her mortal—not an angel sent

From out a mission host, on mercy bent.

We were beguiled by her sweet ways of love—

The growth of her affections round two stems—

As if they were of her, and from above,

We did not note that from her heart the gems

Of her devotion were bestrewn in show'rs

Where'er she went, and gathered like spring flowers

And her last words (coherent)—"I have lived,

And have not lived"—were full of earthly tone

And utterance. They, too, our hearts deceived;

Nor were we mindful till, when left alone,

We heard the flutter of a dove-like wing,

And a sweet strain, such as the seraphs sing.

Then knew we she had come in mortal guise,

To teach us love, and charity, and grace;

With sun-gold in her hair, heaven in her eyes,

And all that's holy in her preaching face.

The scales had fallen, and our vision then

Saw that an angel graced the homes of men. |

――――♦――――

|

|

|

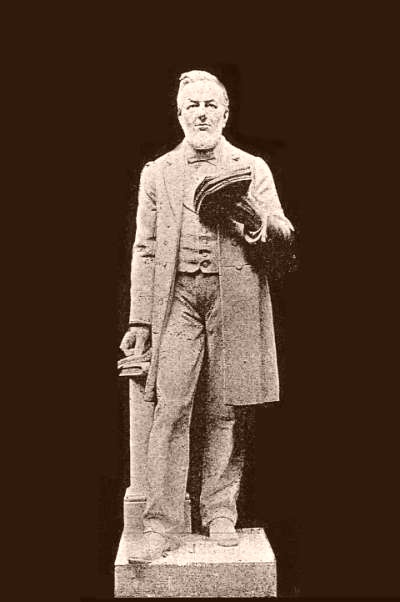

The Brierley statue in

Portland stone by John Cassidy,

above, was destroyed during the 1980s. |

BEN BRIERLEY

("Ab-O'th'-Yate ").

BORN JUNE 26th, 1825.

DIED JANUARY 18th, 1896.

|

THREE voices now are hushed; three singers sweet

Are gone to sing their stirring songs elsewhere —

Waugh, Laycock, Brierley. Now, methinks, they greet

And mingle voices in yon happier sphere.

Each one a son of toil, a child of song,

Has added to his county's fair renown;

Has striven to make his fellows pure and strong,

And worthily has worn the poet's crown.

Not least, though last to go, we mourn to-day

Fun-loving, mirth-provoking Ben, whose mind

Was like a child's — transparent, yet relined,

And whose creations cannot pass away.

Now by his darling's side lay him to rest,

And may each mourner feel that God knows best.

David Lawton |

――――♦――――

THE GUARDIAN

May 2, 1898.

THE BEN BRIERLEY STATUE.

UNVEILING AT QUEEN'S PARK.

MR. G. MILNER ON DIALECTAL WRITERS.

The statue erected in Queen's Park as a monument to the late

Ben Brierley, the famous Lancashire writer, was unveiled on Saturday

by Mr. George Milner, chairman of the Committee who have had the

project in hand. A description of the statue has already

appeared in our columns. In spite of rainy weather, a large

crowd of people thronged the space in front of the main entrance to

the Museum in order to witness the unveiling ceremony. This

was shortened somewhat because of the rain, and it was arranged to

hear the chief speeches afterwards indoors. Sir W. H. Bailey

took the chair on a temporary platform and he explained that he did

so in the absence of the Lord Mayor (Mr. Alderman Gibson), who was

unable to attend owing to indisposition. The Lord Mayor had,

however, written a letter in which he said: "I should have liked by

my personal presence to testify my appreciation of a man who in his

day did so much to brighten the lives and make happier the homes of

the masses of the people."

Mr. George Milner expressed his sense of the honour done him

in asking him to unveil the statue, and he attributed the selection

to the fact that he was chairman of the Monument Committee and also

chairman of the Manchester Literary Club, of which Brierley was one

of the founders and at his death one of the vice presidents.

He would ask why they were there to unveil that monument.

Because Benjamin Brierley was a great and voluminous writer, at any

rate so far as what they called the Lancashire dialect was

concerned, and he was a man who had a very wide circle of readers

and admirers. In proof of that he need only say that the idea

of that statue was only made public on the 3rd September, and so

large and generous was the immediate support given that by the

present date they had the statue completed. Though he knew how

Mr. Brierley was esteemed by the Lancashire people, he was not

prepared for the way in which the people, and especially the poorer

people, came forward to help in the setting up of that monument.

It was because Brierley was a dialectal writer of eminence that they

put up the statue, but it was also because he gave a noble example

of what a poor man, suffering from absolute poverty and even

starvation in his youth, could do to get himself such an education

as Brierley got. He was a typical Lancashire man; he had a

typical Lancashire character for downright outspokenness—character

involving great love of independence. Brierley was, in fact,

like his own "Weaver of Wellbrook," in that old song, which many of

them knew—

|

Aw care no' for titles, nor heawses nor lond,

Owd Jone's a name fittin' for me.

An' gie me a thatch wi a wooden dur latch

An' six feet o' greawnd when a dee-e. |

They had given Brierley the six feet of ground he asked for

in the graveyard near that spot, but they also gave him help while

he lived. Now that he was dead they gave him what would be

found to be a noble statue.—Mr. Milner then unveiled the statue amid

applause. He added that he believed it would be an honour and

credit to Manchester. Those who knew Brierley said it was an

admirable representation of him, and he hoped it would long

perpetuate the name and fame and memory of the sturdy Lancastrian

whom it represented so excellently, and that future generations of

working men and women, seeing the honour that had been conferred on

one of their own class and order, might find in it an incentive to

resolute and self-denying service labour in that pursuit of

knowledge which always brought its own exceedingly great

reward.—(Applause.)

|

|

|

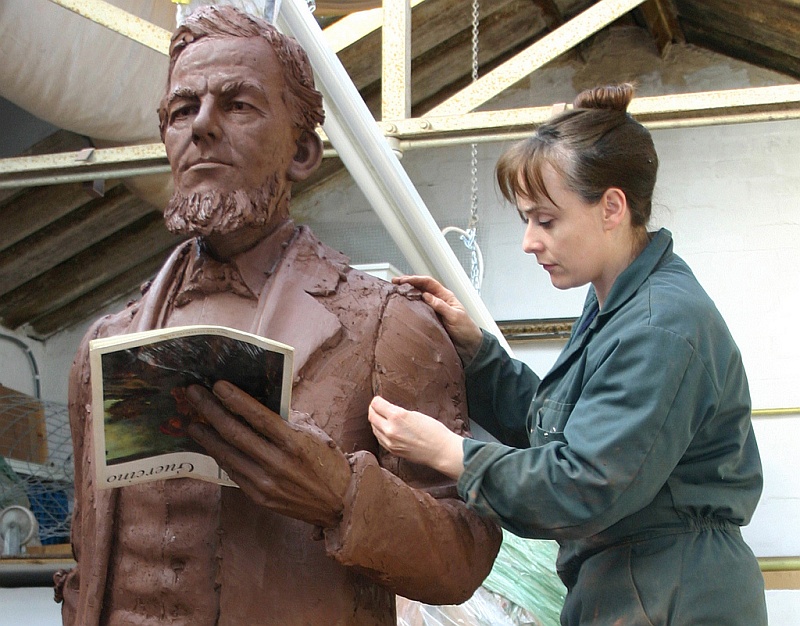

Denise Dutton putting the finishing touches to Ben Brierley in her

Stoke studio.

Photograph by kind permission of

Ted McAvoy.

|

|

|

|

Ben

Brierley in bronze by Denise Dutton,

unveiled at Failsworth in 2006. |

|

――――♦――――

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

FROM Momus, 1879.

A GALLERY of

Lancashire worthies would be indeed incomplete without the

well-known features of Ben Brierley, whose name is a "household

word" in every home, and whose individuality is a type of Lancashire

pathos and humour with all its quaint conceits and dialectic

mannerisms. He has achieved his popularity not only by

voluminous literary work, but by a large-hearted and discreet

philanthropy that endeavours to elevate the class from which he

sprung by calling attention to its wants and grievances, and at the

same time instilling those habits of self-help and self-control,

without which all charitable organizations are simply worthless.

Mr. Brierley was born at the Rocks, in Failsworth, June 26th,

1825. He attended the school in that village till his sixth

year, when his parents, who were in very humble circumstances,

removing to Hollinwood, little Benny lost the advantages of a day

school, his services being required at the bobbin-wheel. But

to him who is bent on self-improvement, difficulties are only

obstacles to be surmounted, and at the Hollinwood Night and

Primitive Methodist Sunday Schools, our hero was grafted in the

rudiments of the three R's, and such was his love for reading, that

at the very early age of seven, he had read his bible through no

less than three times. In 1840 he returned to Failsworth Old

School, and was instrumental in forming a Mutual Improvement

Society, which proved to be the germ of a Mechanics' Institute.

To an uncle, who was a leading spirit in that school he owes his

introduction to Shakspere, Byron, and Shelley, the perusal of whose

works had a marked effect on his future career,

|

"And lured him on to those inspiring toils

By which man masters men." |

At any rate, about this time his "muse began to labour," and

one of the very first deliveries was a sketch entitled "My uncle's

garden," commemorative of the Sunday mornings spent therein happy

and edifying conversation, which was, as Brierley says, something to

be remembered for a lifetime. This sketch was published in

1849, in the supplement of the Manchester Spectator; but his

labours, consecutively as hand-loom weaver, piecer, and silk warper,

prevented him for some time from following the bent of his

inclination. When we state that for nine years he had to walk

to and from his work nine miles each day our readers may imagine he

had but little time for the cultivation of his literary faculties,

and it was only during those peregrinations to and fro that he could

find time to indulge in reading, which had now become one of the

necessities of his existence. In 1855 he married; and, shortly

afterwards, work in his branch of trade failing, accepted the

sub-editorship of the Oldham Times, but left that situation

in 1862, having obtained a short engagement in London. During

his stay in the metropolis he was introduced to the Savage Club, and

made the acquaintance of the Brough Brothers, Andrew Halliday, Tom

Robertson, and other well-known dramatic celebrities. When

Colman's Magazine, which had been started by members of the

club, collapsed, Mr. Brierley returned to Manchester, where he has

since resided, settling down as an author and reader of his own

works, in both of which capacities he has achieved a popularity

second to no man in the county. The library of a Lancashire

home would indeed be incomplete without the works of Ben

Brierley—his unadulterated patois being alike relished by his

readers and hearers throughout the whole Palatinate.

Mr. Brierley's married and literary career may be said to be

co-existent, for in 1855 was written "Jimmie the Jobber" a little

story which he submitted to a friend, who strongly advised him not

to publish it; but, stimulated by the success of Edwin Waugh, whose

"Come whoam to thi

childer an' me" had about that time rendered its author famous,

he resolved to publish it in one form or another, and the sketch

appeared in the Manchester Spectator, and, being afterwards

published in book form, had a good sale, as had also his succeeding

ventures. His success led to his introduction to the editor of

the Weekly Times, and he at once commences to write for the

supplement of that journal. But strong as was Brierley's

attachment to journalistic literature, his love of the drama was

still stronger; and, aspiring to histrionic honours, be produced a

dramatic version of his "Layrock of Langleyside," in which he

himself played the principal part, and achieved a decided success as

an impersonator of Lancashire character. As an author, Mr.

Brierley possesses the qualifications of genial humour and touching

pathos; and his early associations have given him a grip of his

subject of which he has not been slow to avail himself, his mind

being quick to appropriate those quaint oddities of Lancashire life

which his keen eye is ever ready to detect.

A turning point in his life was the institution of Ben

Brierley's Journal, which attained great popularity, and a

marvellous circulation, the "gude fowk" of Lancashire being

delighted with the bright and healthy stories, written in their own

idiomatic language, and with a grasp of their social characteristics

which an intimate acquaintance can alone evolve. Though Ben's

poetry is overshadowed by his prose, he has an undeniable poetic

temperament, and some of his shorter pieces are real gems. In a

short sketch like this we cannot enumerate his multitudinous works

which, if we mistake not, have been published in a complete form in

some fifteen or twenty volumes.

In the November of 1875 Mr. Brierley was elected a City

Councillor, and although his candidature had been almost regarded as

a joke, Ab'-o'th'-Yate was not long in proving to his constituents

that their confidence had not been misplaced. His maiden

speech was in support of the Free Libraries Committee's successful

attempt to prevent the Reference Department being located in the

attic of the New Town Hall. The peroration will be long

remembered by the parody on Longfellow's "Excelsior," the concluding

lines of which were as follow—

|

"Oh! what would Grundy say, or Lamb,

If, without aid of 'bus or tram,

They sought up there their heads to cram?

All right Excelsior—but d—n

The Town Hall Stairs." |

On resuming his seat, amid shouts of laughter and applause,

Alderman Lamb rose to reply, but confessed it required considerable

nerve to follow the new councillor. Ben Brierley had made his

mark, and the first vacancy found him one of the Free Libraries

Committee. His municipal experiences, more especially in

connection with the Nuisances Committee, led him to raise the

question "What shall we do with our poor?" No man was better

qualified to give an opinion on the subject, and the dailies, by

ventilating the question, proved that he had hit the right nail on

the head. The Artisans' Dwelling Act, although shelved by the

Health Committee, was another instance of Brierley's sympathies for

the humbler classes; and his letter on the "Domestic Economy

Congress," entitled A Flourish of Trumpets, was described by

a well-known barrister as a "skinner."

His sphere of usefulness may be most aptly described by the

fact that he has, during his municipal career, served on a greater

number of Committees and Sub-Committees of General purposes, than

perhaps any other member of the Corporation, viz: "Nuisances,"

"Hackney Coach," "Lamp and Scavenging," "Free Libraries," "Parks and

Cemeteries," and "Baths and Wash-houses Committees," Public Rooms

and Printing and Stationery Sub-Committees."

Here is an amount of work of which any Councillor may well be

proud; but in addition to this Mr. Brierley, in connection with the

relief organisations during the past winter, assisted on the

platform in no less than twenty-two entertainments, his services

always being gratuitous, even to the payment of his personal

expenses.

Such a man may well be popular, and when Ab'-o'th'-Yate

crosses the Atlantic, on a visit to our American cousins, during the

ensuing autumn, and such I believe is his intention, thousands of

admirers will not only wish him God speed, but a quick return to the

old country—spots which his graphic pen has rendered dear to many a

town-dweller. I have before alluded to his dramatic instincts,

and may as well call attention to the fact that he, in conjunction

with his friend Mr. Dottie, will appear during the month of

September at the Theatre Royal, in his own drama of "The Lancashire

Weaver Lad." The occasion will be a most interesting one, and

no doubt advantage will be taken of such an opportunity to prove to

Ben Brierley the estimation in which he is held by his

fellow-citizens.

|

――――♦――――

|

AT MY DAUGHTER'S GRAVE.

ON HER NINETEENTH BIRTHDAY. |

|

NOVEMBER'S

chills hang in the sullen air,

The earth is shrouded in funeral gloom;

The trees around seem fretful, weird, and bare,

As here I stand beside thy silent tomb,—

My daughter!—loved alike by sire and friend—

Thy Mother's idol, thus to thee I bend!

It seems an age since last I saw thy face,

Smiling to make e'en death a loveliness;

And as the scalding tears each other chase

Down cheeks that ever must be flooded thus,

I feel 'twould be the prime reward of prayer,

To see the glory of thine eyes and hair.

Now cold's the hearth that once thy presence warmed;

Dark is the room of which thou wert the light;

Silent the music which my soul hath charmed,

When home, and wounded, from the world's stern fight.

Thy stool—thy chair—the couch—all vacant now—

Cry through the darkness—"Annie, where art thou?"

Thy mother nightly lingers at the gate,

To watch thy coming; and as pale the lights,

She says—"How long—how very long—to wait!

Such girls as she should not stay out at nights.

All her companions are in bed ere this,

And I'm still waiting for her 'good night' kiss."

This day thou would'st have marked thy nineteenth year;

A day looked forward too long months ago;

That should have brought to us, nor sigh, nor tear,

But such sweet joy as only parents know.

Who could have dreamt, or felt the galling fear,

That thou would'st hold thy birthday revels here?

A bridal wreath bedecks thy marble brow;

The robes* enwrap thy form that should have swept

The path which leads to where we plight the vow

Of love eternal—broken oft, or kept.

If shades commingle 'round thy hallowed bed,

Then thou'lt beseem the bridals of the dead.

Ah, frenzied dreams—ah, visions wild and strange,

That haunt for aye this wilderness of air!

If in the great, inevitable change,

Thou, God, seeth fit to show Thy mercies where

Love's blossoms are by thousands largely shared,

This garden of one flow'r Thou might'st have spared.

They who would tell me life is but a span

Know not affliction—not the loss of thee.

'Tis woe, laid heavy on the soul of man,

That makes of time a drear eternity.

Life's sunniest moments fly the swallow's flight,

But oh, how slowly creeps the hours of night!

Great God! whose Will it was to take away

The only lamb that nestled in our fold—

If through His tears who wept on Calvary

The dear one's face we may again behold;

Oh, let thy messenger of love descend,

To give assurance such shall be the end!

My pray'r is heard, a voice from out the clouds

Proclaims in trumpet clangour to the dead

"Arise ye, shake ye off your mortal shrouds,

And put on Heaven's eternal robes instead!"

I feel the flutter of an angel's wing

And hear Heaven's choir their sweet Hosannas sing.

The vision's past; the gloom is thickening round,

The mists enwrap me with an icy fold.

But here my soul hath its best solace found,

And turned to summer warmth the wintry cold.

Thus, hoping, dear, thy face again to see,

I weave those immortelles of song to thee!

Ben Brierley |

|

* She was buried in

full brides-maid's costume, intended to have been worn at the

wedding of a cousin. The poor girl begged of her mother, a

few days before she died, that she might be allowed to wear the

dress on the wedding-day, if not able to attend the ceremony.

The request was complied with; it served for her shroud. |

<>

|