|

HOME-LIFE OF THE LANCASHIRE FACTORY FOLK DURING THE COTTON

FAMINE.

PREFACE

――――♦――――

The following chapters are reprinted from the columns of the Manchester

Examiner and Times, to which Paper they were contributed by the Author

during the year 1862.

――――♦――――

AMONG THE BLACKBURN

OPERATIVES

CHAPTER I.

"Poor Tom's a-cold. Who gives anything to poor Tom?"

― King Lear.

|

AW WOD THIS WAR WUR ENDED. |

|

There's nobuddy knows wod we'n gooan

through

Sin' th' factories stopt at fost,

An' heaw mitch life's bin wasted too,

An heaw mitch brass we'n lost;

Aw trys sometimes to reckon up,

Bud keawntin connud mend id;

When aw sit deawn wi nowt to sup—

Aw wod this war wur ended.

A boddy's lifetime's nod so lung—

Nod them as lives to th' lungust;

Sooa dusend id seem sadly wrung

For th' healthiest an' strungust

To give three wul years' pith an' pride

To rust an' ruin blended,

An ravin up o'th' loss beside?—

Aw wod this war wur ended!

A dacent chap ull do his best,

An' eawt o' wod he's earnin

Ged th' owdest son a trade, an' th' rest

O' th' lads a bit o' learnin;

Bud iv he's eawt o' wark; wey then,

Unschollard, unbefriended,

His childer grow up into men—

Aw wod this war wur ended!

As times hes bin, aw owt some "tin"

For shop stuff ut Lung Nailey's,

An' case aw cuddent pay 't, yo sin,

He's gooan an' sent th' bum bailies ;

They'n sowd us up, booath pot an' pooak,

An' paid th' owd scoor off splendid;

They just dun wod they will wi fooak.—

Aw wod this war wur ended!

Neaw aw feer noather dun nor bum,

Wi o their kith an' kin'—

They'll fetch nowt eawt o' th' heawse, by

gum!

Becose there's nowt left in.

Aw'm welly weary o mi life,

An' cuddend, if aw'd spend id,

Ged scran for th' kids, mysel, an' th' wife.—

Aw wod this war wur ended!

Some forrud foos ull rant reet hard,

An' toke a deal o' nonsense;

Bud let um gabble tell theyr terd,

Id's reet enuff i' one sense;

They waste their brass an' rack their brains,

Yet, be nod yo offended,

They'll ged their labour for their pains,

Bud th' war's nod theerby ended!

Some factory maisters tokes for t' Seawth

Wi' a smooth an' oily tongue,

Bud iv they'd sense they'd shut their

meawth,

Or sing another song;

Let liberty nod slavery

Be fostered an' extended—

Four million slaves mun yet be free,

An' then t' war will be ended. |

|

WILLIAM

BILLINGTON

BLACKBURN,

1863.

|

Blackburn is one of the towns which has suffered more than the rest in the

present crisis, and yet a stranger to the place would not see anything in

its outward appearance indicative of this adverse nip of the times.

But to any one familiar with the town in its prosperity, the first glance

shows that there is now something different on foot there, as it did to me

on Friday last.

The morning was wet and raw, a state of weather in

which Blackburn does not wear an Arcadian aspect, when trade is good.

Looking round from the front of the railway station, the first thing which

struck me was the great number of tall chimneys which were smokeless, and

the unusual clearness of the air. Compared with the appearance of

the town when in full activity, there is now a look of doleful holiday, an

unnatural fast-day quietness about everything. There were few carts

astir, and not so many people in the streets as usual, although so many

are out of work there. Several, in the garb of factory operatives,

were leaning upon the bridge, and others were trailing along in twos and

threes, looking listless and cold; but nobody seemed in a hurry.

Very little of the old briskness was visible. When the mills are in

full work, the streets are busy with heavy loads of twist and cloth; and

the workpeople hurry in blithe crowds to and from the factories, full of

life and glee, for factory labour is not so hurtful to healthy life as it

was thirty years ago, nor as some people think it now, who don't know much

about it.

There were few people at the shop windows, and fewer

inside. I went into some of the shops to buy trifling things of

different kinds, making inquiries about the state of trade meanwhile, and,

wherever I went, I met with the same gloomy answers. They were doing

nothing, taking nothing; and they didn't know how things would end.

They had the usual expenses going on, with increasing rates, and a

fearfully lessened income, still growing less. And yet they durst

not complain; but had to contribute towards the relief of their starving

neighbours, sometimes even when they themselves ought to be receiving

relief, if their true condition was known. I heard of several

shopkeepers who had not taken more across their counters for weeks past

than would pay their rents, and some were not doing even so much as that.

This is one painful bit of the kernel of life in Blackburn just now, which

is concealed by the quiet shell of outward appearance.

Beyond this unusual quietness, a stranger will not see much

of the pinch of the times, unless he goes deeper; for the people of

Lancashire never were remarkable for hawking their troubles much about the

world. In the present untoward pass, their deportment, as a whole,

has been worthy of themselves, and their wants have been worthily met by

their own neighbours. What it may become necessary to do hereafter,

does not yet appear. It is a calamity arising, partly from a wise

national forbearance, which will repay itself richly in the long run.

But,

apart from that widespread poverty which is already known and relieved,

there is, in times like the present, always a certain small proportion,

even of the poorest, who will "eat their cake to th' edge," and then

starve bitterly before they will complain. These are the flower of

our working population; they are of finer stuff than the common staple of

human nature. Amongst such there must be many touching cases of

distress which do not come to light, even by accident. If they did,

nobody can doubt the existence of a generous will to relieve them

generously.

To meet such cases, it is pleasant to learn, however, as

I did, that there is a large amount of private benevolence at work in

Blackburn, industriously searching out the most deserving cases of

distress. Of course, this kind of benevolence never gets into the

statistics of relief, but it will not the less meet with its reward.

I heard also of one or two wealthy men whose names do not appear as

contributors to the public relief fund, who have preferred to spend

considerable sums of money in this private way. In my wanderings

about the town I heard also of several instances of poor people holding

relief tickets, who, upon meeting with some temporary employment, have

returned their tickets to the committee for the benefit of those less

fortunate than themselves. Waiving for the present all mention of

the opposite picture; these things are alike honourable to both rich and

poor.

|

|

|

|

|

Top ―

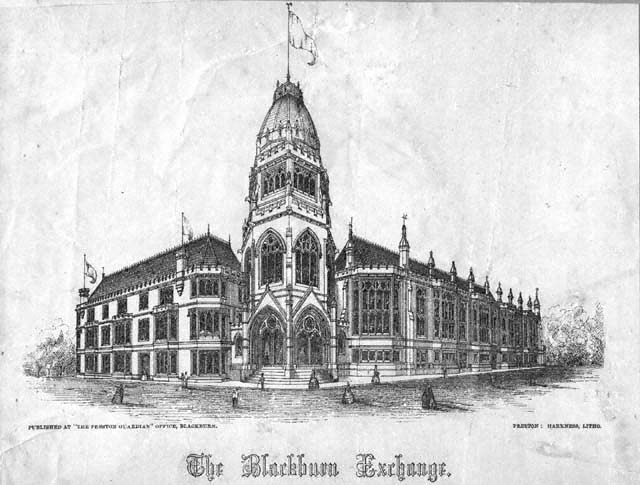

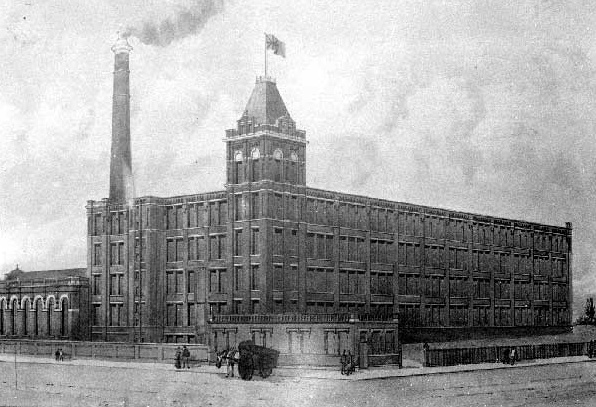

Architect’s drawing of Blackburn Cotton Exchange, 1863. The

Cotton Exchange could have been Blackburn’s most impressive

building, but didn’t reach completion, having been started just as

the cotton famine crippled Lancashire’s textile industry. Above ―

as completed.

Courtesy of the 'Cotton

Town digitization project.' |

A little past noon, on Friday, I set out to visit the great

stone quarries on the southern edge of the town, where upwards of six

hundred of the more robust factory operatives are employed in the lighter

work of the quarries. This labour consists principally of breaking

up the small stone found in the facings of the solid rock, for the purpose

of road-mending and the like. Some, also, are employed in

agricultural work, on the ground belonging to the fine new workhouse

there. These factory operatives, at the workhouse grounds, and in

the quarries, are paid one shilling a day ― not much, but much better than

the bread of idleness; and for the most part, the men like it better, I am

told.

The first quarry I walked into was the one known by the name

of "Hacking's Shorrock Delph." There I sauntered about, looking at

the scene. It was not difficult to distinguish the trained quarrymen

from the rest. The latter did not seem to be working very hard at

their new employment, and it can hardly be expected that they should,

considering the great difference between it and their usual labour.

Leaning on their spades and hammers, they watched me with a natural

curiosity, as if wondering whether I was a new ganger, or a contractor

come to buy stone. There were men of all ages amongst them, from

about eighteen years old to white-headed men past sixty. Most of

them looked healthy and a little embrowned by recent exposure to the

weather; and here and there was a pinched face which told its own tale.

I got into talk with a quiet, hardy-looking man, dressed in soil-stained

corduroy. He was a kind of overlooker. He told me that there

were from eighty to ninety factory hands employed in that quarry.

"But," said he, "it varies a bit, yo known. Some on 'em gets knocked

up neaw an' then, an' they han to stop a-whoam a day or two; an' some on 'em

connot ston gettin' weet through ― it mays 'em ill; an' here an' theer one

turns up at doesn't like the job at o' ― they'd rayther clem. There

is at's both willin' an' able; thoose are likely to get a better job,

somewheer. There's othersome at's willin' enough, but connot ston th'

racket. They dun middlin', tak 'em one wi' another, an' considerin'

that they're noan use't to th' wark. Th' hommer fo's leet wi' 'em;

but we dunnot like to push 'em so mich, yo known ― for what's a shillin' a

day? Aw know some odd uns i' this delph at never tastes fro mornin'

till they'n done at neet, ― an' says nought abeawt it, noather. But

they'n families. Beside, fro wake lads, sick as yon, at's bin

train't to nought but leet wark, an' a warm place to wortch in, what con

yo expect? We'n had a deeal o' bother wi 'em abeawt bein' paid for

weet days, when they couldn't wortch. They wur not paid for weet

days at th' furst; an' they geet it into their yeds at Shorrock were to

blame. Shorrock's th' paymaister, under th' Guardians. But,

then, he nobbut went accordin' to orders, yo known. At last, th'

Board sattle't that they mut be paid for weet and dry, ― an' there's bin

quietness sin'. They wortchen fro eight till five; an', sometimes,

when they'n done, they drilln o' together i'th road yon ― just like

sodiurs ― an' then they walken away i' procession. But stop a bit; ―

just go in yon, an' aw'll come to yo in a two-thre minutes."

|

Extract

from the . . . .

NEW YORK TIMES

26 November, 1862.

BLACKBURN. |

|

The returns of out-relief presented to the Board of

Guardians, show a further increase of destitution. The number

of persons relieved in the Union during the week was 20,082.

The chief constable's return shows 45 mills are entirely closed,

throwing idle no fewer than 17,337 persons. With the small

average of two persons for every worker, there are, therefore,

35,000 dependent on charity for support, but which number, on making

allowance for other trades likewise depressed, may be extended to

36,000 who are relieved to an amount "considerable under 2s. per

head," from all sources. We believe the Committee contemplates

taking charge of 20,000 and of relieving them with 1s. 6d. each per

week, 6d. below the sum stated by Sir JAMES

KAY SHUTTLEWORTH,

to maintain life and health. |

He

returned, accompanied by the paymaster, who offered to conduct me through

the other delphs. Running over his pay-book, he showed me, by

figures opposite each man's name, that, with not more than a dozen

exceptions, they had all families of children, ranging in number from two

to nine. He then pointed out the way over a knoll, to the next

quarry, which is called "Hacking's Gillies' Delph," saying that he would

follow me thither. I walked on, stopping for him on the nearest edge

of the quarry, which commanded a full view of the men below. They

seemed to be waiting very hard for something just then, and they stared at

me, as the rest had done; but in a few minutes, just as I began to hear

the paymaster's footsteps behind me, the man at the nearest end of the

quarry called "Shorrock!" and a sudden activity woke up along the line.

Shorrock then pointed to a corner of the delph where two of these poor

fellows had been killed the week before, by stones thrown out from a fall

of earth.

We went down through the delph, and up the slope, by the

place where the older men were at work in the poorhouse grounds.

Crossing the Darwen road, we passed the other delphs, where the scene was

much the same as in the rest, except that more men were employed there.

As we went on, one poor fellow was trolling a snatch of song, as he

hammered away at the stones. "Thir't merry, owd mon," said I, in

passing. "Well," replied he, "cryin' 'll do nought, wilt?" And

then, as I walked away, he shouted after me, with a sort of sad smile,

"It's a poor heart at never rejoices, maister."

|

|

|

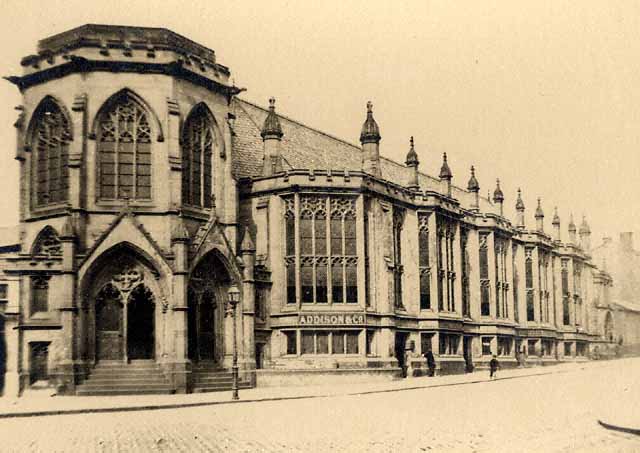

Provision-shop where goods are obtained for tickets

issued by the Manchester and Salford

Provident Society.

Illustrated London News, November 29, 1862. |

Leaving the

quarries, we waited below, until the men had struck work for the day, and

the whole six hundred came trooping down the road, looking hard at me as

they went by, and stopping here and there, in whispering groups. The

paymaster told me that one-half of the men's wages was paid to them in

tickets for bread ― in each case given to the shopkeeper to whom the

receiver of the ticket owed most money ― the other half was paid to them

in money every Saturday.

|

|

|

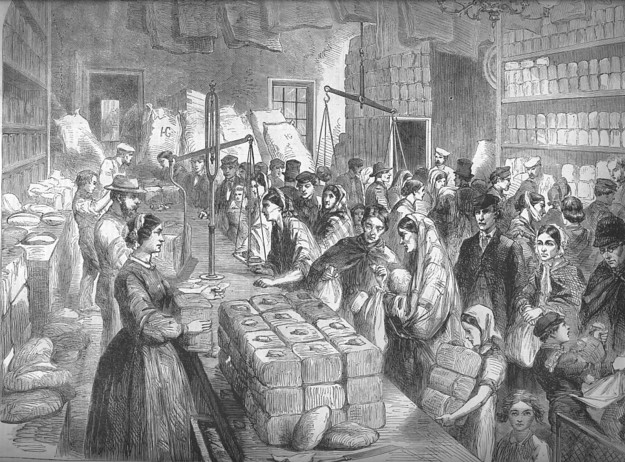

Blackburn soup kitchen voucher, 1862. Vouchers

such a these were distributed by the clergy and other relief

organisations to unemployed mill workers during the Cotton Famine.

Tickets were also issued for bread and coal

― courtesy of the 'Cotton Town

digitization project.' |

Before returning to town I learnt that

twenty of the more robust men, who had worked well for their shilling a

day in the quarries, had been picked out by order of the Board of

Guardians, to be sent to the scene of the late disaster, in Lincolnshire,

where employment had been obtained for them, at the rate of 3s. 4d. per

day. They were to muster at six o'clock next morning to breakfast at

the soup kitchen, after which they were to leave town by the seven o'clock

train.

I resolved to be up and see them off. On retiring to

bed at the "Old Bull," a good-tempered fellow, known by the name of

"Stockings," from the fact of his being "under-boots," promised to waken

me by six o'clock; and so I ended the day, after watching "Stockings"

write "18" on the soles of my boots, with a lump of chalk.

"Stockings" might as well have kept his bed on Saturday morning. My

room was close to the ancient tower, left standing in the parish

churchyard; and, at five o'clock, the beautiful bells of St Marie's struck

up, filling my little chamber with that heart-stirring music, which, as

somebody has well said, "sounds like a voice from the middle ages."

I could not make out what all this early melody meant; for I had forgotten

that it was the Queen's birthday.

The old tower was in full view

from my bed, and I lay there a while looking at it, and listening to the

bells, and dreaming of Whalley Abbey, and of old features of life in

picturesque Blackburnshire, now passed away. I felt no more

inclination for sleep; and when the knock came to my door, I was dressed

and ready.

There were more people in the streets than I expected,

and the bells were still ringing merrily. I found the soup kitchen a

lively scene. The twenty men were busy at breakfast, and there was a

crowd waiting outside to see them off. There were several members of

the committee in the kitchen, and amongst them the Rev. Joseph V. Meaney,

Catholic priest, went to and fro in cheerful chat. After breakfast,

each man received four pounds of bread and one pound of cheese for the

day's consumption. In addition to this, each man received one

shilling; to which a certain active member of the committee added

threepence in each case. Another member of the committee then handed

a letter to each of the only three or four out of the twenty who were able

to write, desiring each man to write back to the committee, ― not all at

once, but on different days, after their arrival. After this, he

addressed them in the following words :―

"Now, I hope that every man will

conduct himself so as to be a credit to himself and an honour to

Blackburn. This work may not prove to be such as you will like, and

you must not expect it to be so. But, do your best; and, if you find

that there is any chance of employment for more men of the same class as

yourselves, you must write and let us know, so as to relieve the distress

of others who are left behind you. There will be people waiting to

meet you before you get to your journey's end; and, I have no doubt, you

will meet with every fair encouragement. One-half of your wages will

be paid over to each man there; the other half will be forwarded here, for

the benefit of your families, as you all know. Now go, and do your

duty to the best of your power, and you will never regret it. I wish

you all success."

At half-past six the men left the kitchen for the

station. I lingered behind to get a basin of the soup, which I

relished mightily. At the station I found a crowd of wives,

children, and friends of those who were going away. Amongst the

rest, Dr Rushton, the vicar of Blackburn, and his lady, had come to see

them off. Here a sweet little young wife stood on the edge of the

platform, with a pretty bareheaded child in her arms, crying as if her

heart would break. Her husband now and then spoke a consoling word

to her from the carriage window. They had been noticed sharing their

breakfast together at the kitchen.

A little farther on, a poor old

Irishwoman was weeping bitterly. The Rev. Mr Meaney went up to her,

and said, "Now, Mrs Davis, I thought you had more sense than to cry."

"Oh," said a young Irishwoman, standing beside her, "sure, she's losin'

her son from her." "Well," said the clergyman, cheeringly, "it's not

your husband, woman." "Ah, thin," replied the young woman, "sure,

it's all she has left of him." On the door of one compartment of the

carriage there was the following written label :― "Fragile, with care."

"How's this, Dennis?" said the Catholic priest to a young fellow nearest

the door; "I suppose it's because you're all Irishmen inside there."

In another compartment the lads kept popping their heads out, one after

another, shouting farewells to their relatives and friends, after which

they struck up, "There's a good time coming!" One wag of a fellow

suddenly called out to his wife on the platform, "Aw say, Molly, just run

for thoose tother breeches o' mine. They'n come in rarely for weet

weather." One of his companions replied, "Thae knows hoo cannot get

'em, Jack. Th' pop-shops are noan oppen yet." One hearty cheer

arose as the train started, after which the crowd dribbled away from the

platform.

I returned to the soup kitchen, where the wives, children,

and mothers of the men who had gone were at breakfast in the inner

compartment of the kitchen. On the outer side of the partition five

or six pinched-looking men had straggled in to get their morning meal.

When they had all done but one, who was left reared against

the wooden partition finishing his soup, the last of those going away

turned round and said, "Sam, theaw'rt noan as tickle abeawt thi mate as

thae use't to be." "Naw," replied the other, "it'll not do to be

nice these times, owd mon. But, thae use't to think thisel' aboon

porritch, too, Jone. Aw'll shake honds wi' tho i' thae's a mind, owd

dog." "Get forrud wi' that stuff, an' say nought," answered Jone.

I left Sam at his soup, and went up into the town. In the course of

the day I sat some hours in the Boardroom, listening to the relief cases;

but of this, and other things, I will say more in my next.

CHAPTER II.

|

|

|

Cotton Famine Relief Office, Stalybridge.

Courtesy Tameside Local Studies and Archives Centre. |

A little after ten o'clock on Saturday forenoon, I went into the

Boardroom, in the hope of catching there some glimpses of the real state

of the poor in Blackburn just now, and I was not disappointed; for amongst

the short, sad complainings of those who may always be heard of in such a

place, there was many a case presented itself which gave affecting proof

of the pressure of the times. Although it is not here where one must

look for the most enduring and unobtrusive of those who suffer; nor for

the poor traders, who cannot afford to wear their distress upon their

sleeves, so long as things will hold together with them at all; nor for

that rare class which is now living upon the savings of past labour ― yet,

there were many persons, belonging to one or other of these classes, who

applied for relief evidently because they had been driven unwillingly to

this last bitter haven by a stress of weather which they could not bide

any longer.

There was a large attendance of the guardians; and they

certainly evinced a strong wish to inquire carefully into each case, and

to relieve every case of real need. The rate of relief given is this

(as you will have seen stated by Mr Farnall elsewhere) :― "To single able

bodied men, 3s. for three days' work. To the man who had a wife and

two children, 6s. for six days' work, and he would have 2s. 6d. added to

the 6s., and perhaps a pair of clogs for one of his children. To a

man who had a wife and four children, 10s. was paid for six days' labour,

and in addition 4s., and sometimes 4s. 6d., was given to him, and also

bits of clothing and other things which he absolutely wanted."

|

Extract from the . . . .

NEW YORK TIMES

26 November, 1862.

PRESTON. |

|

So far as the statistics of the Relief Committee have been made up,

it appears that the distress in this town is steadily and fearfully

increasing. The police returns of the state of employment in

mills are as follows: Number fully employed, 3,813; five days 663;

four days, 2,276; three days 7,181; two days 665; and totally

unemployed, 12,874. The number out of work unconnected with

the mills is estimated at 600, and the total weekly loss of wages at

£13,500. No less than 41½ per cent.

of the entire population are now receiving relief from the

Committed, the numbers being 8,617 cases, comprising 34,227 persons.

In addition to this, 330 females have been employed at the

sewing-schools, and 900 persons supplied with nutritious food from

the sick kitchen. This increased is the largest yet reported

since the cotton crises began.

The avenues of the poor offices are utterly impassable except

by the interference of the police officer in attendance, and the

Poor law officials are engaged until 9 and even 10 o'clock at night

in the performance of their duties.

The fever in Preston is spreading. It has chiefly

arisen in families where there has been a long-continued want of

nutritious aliment or a protracted sameness of food among the

paupers operatives. It is said by the medical officers to be

the same as the fever which raged so virulently not long ago in

Ireland, with similar causatives. The Relief Committee have

wisely varied the quality of the food given to those dependent on

their charity, and they are now dispensing very excellent meat soup,

which is joyfully received. |

Sitting at that Board I saw some curious ― some painful things. It

was, as one of the Board said to me, "Hard work being there."

In one

case, a poor, pale, clean-looking, and almost speechless woman presented

herself. Her thin and sunken eyes, as well as her known

circumstances, explained her want sufficiently, and I heard one of the

guardians whisper to another, "That's a bad case. If it wasn't for

private charity they'd die of starvation." "Yes," replied another;

"that woman's punished, I can see."

Now and then a case came on in

which the guardians were surprised to see a man ask for relief whom

everybody had supposed to be in good circumstances. The first

applicant, after I entered the room, was a man apparently under forty

years of age, a beerhouse keeper, who had been comparatively well off

until lately. The tide of trouble had whelmed him over. His

children were all factory operatives, and all out of work; and his wife

was ill. "What; are you here, John?" said the chairman to a

decent-looking man who stepped up in answer to his name. The poor

fellow blushed with evident pain, and faltered out his story in few and

simple words, as if ashamed that anything on earth should have driven him

at last to such an extremity as this.

In another case, a clean old decrepid man presented himself. "What's brought you here, Joseph?"

said the chairman. "Why; aw've nought to do, ― nor nought to tak

to." "What's your daughter, Ellen, doing, Joseph?" "Hoo's eawt

o' wark." "And what's your wife doing?" "Hoo's bin bed-fast

aboon five year." The old man was relieved at once; but, as he

walked away, he looked hard at his ticket, as if it wasn't exactly the

kind of thing; and, turning round, he said, "Couldn't yo let me be a

sweeper i'th streets, istid, Mr Eccles?"

A clean old woman came up,

with a snow-white nightcap on her head. "Well, Mary; what do you

want?" "Aw could like yo to gi mo a bit o' summat, Mr Eccles, ― for

aw need it" "Well, but you've some lodgers, haven't you, Mary?"

"Yigh; aw've three." "Well; what do they pay you?" "They pay'n

mo nought. They'n no wark, ― an' one connot turn 'em eawt."

|

AW'VE HARD WARK TO HOWD

UP MI YED. |

|

WHEEREVER aw trudge neaw-a-days,

Aw'm certain to see some owd friend

Lookin' anxiously up i' my face,

An' axin' when times are beawn t' mend.

Aw'm surprised heaw folk live, aw declare,

Wi' th' clammin' an' starvin' they'n stood;

God bless 'em, heaw patient they are!

Aw wish aw could help 'em, aw would.

But really aw've nowt aw con give,

Except it's a bit ov a song,

An' th' Muses han hard wark to live,

One's bin hamper'd an' powfagg'd so long;

Aw've tried to look cheerful an' bowd,

An' yo know what aw've written an' said,

But iv truth mun be honestly towd,

Aw've hard wark to howd up mi yed!

There'll be some on us missin' aw deawt

Iv there isn't some help for us soon;

We'n bin jostled an' tumbled abeawt,

Till we're welly o knocked eawt o' tune;

Eawr Margit, hoo frets an' hoo cries,

As hoo sits theer, wi' th' choilt on her knee

An' aw connot blame th' lass, for hoo tries

To be cheerful an' gradely wi' me.

Yon Yankees may think it's rare fun,

Kickin' up sich a shindy o'th' globe;

Confound 'em, aw wish they'd get done,

For they'd weary eawt th' patience o' Job!

We shall have to go help 'em, that's clear,

Iv they dunno get done very soon;

Iv eawr Volunteers wur o'er theer,

They'd sharpen 'em up to some tune.

Neaw it's hard for a mortal to tell

Heaw long they may plague us this road;

Iv they'd hurt nob'dy else but thersel,

They met fo eawt and feight till they'rn stow'd.

Aw think it's high time someb'dy spoke,

When so many are cryin' for bread;

For there's hundreds an' theawsands o' folk,

Deawn i' Lancashire hardly hawve fed.

Th' big men, when they yer eawr complaint,

May treat it as "gammon " an' "stuff,"

An' tell us we use to' much paint,

But we dunnot daub paint on enuff,

If they think it's noan true what we sen,

Ere they charge us wi' tellin' a lie,

Let 'em look into th' question loike men,

An' come deawn here a fortnit an' try. |

|

SAMUEL

LAYCOCK |

This was all quite true. "Well, but you live with your son; don't

you?" continued the chairman. "Nay," replied the old woman, "he

lives wi' me; an' he's eawt o' wark, too. Aw could like yo to

do a bit o' summat for us. We're hard put to 't." "Don't you

think she would be better in the workhouse?" said one of the guardians.

"Oh, no," replied another; "don't send th' owd woman there. Let her

keep her own little place together, if she can."

Another old woman

presented herself, with a threadbare shawl drawn closely round her gray

head. "Well, Ann," said the chairman, "there's nobody but yourself

and your John, is there?" "Nawe." "What age are you?" "Aw'm

seventy." "Seventy!" "Aye, I am." "Well, and what age is

your John?" "He's gooin' i' seventy-four." "Where is he, Ann?"

"Well, aw laft him deawn i' th' street yon; gettin' a load o' coals in."

There was a murmur of approbation around the Board; and the old woman was

sent away relieved and thankful.

There were many other affecting

cases of genuine distress arising from the present temporary severity of

the times. Several applicants were refused relief on its being

proved that they were already in receipt of considerably more income than

the usual amount allowed by the Board to those who have nothing to depend

upon. Of course there are always some who, having lost that fine

edge of feeling to which this kind of relief is revolting, are not

unwilling to live idly upon the rates as much and as long as possible at

any time, and who will even descend to pitiful schemes to wring from this

source whatever miserable income they can get. There are some, even,

with whom this state of mind seems almost hereditary; and these will not

be slow to take advantage of the present state of affairs. Such

cases, however, are not numerous among the people of Lancashire.

It

was a curious thing to see the different demeanours and appearances of the

applicants ― curious to hear the little stories of their different

troubles. There were three or four women whose husbands were away in

the militia; others whose husbands had wandered away in search of work

weeks ago, and had never been heard of, since. There were a few very

fine, intelligent countenances among them. There were many of all

ages, clean in person, and bashful in manner, with their poor clothing put

into the tidiest possible trim; others were dirty, and sluttish, and noisy

of speech, as in the case of one woman, who, after receiving her ticket

for relief, partly in money and partly in kind, whipped a pair of worn

clogs from under her shawl, and cried out, "Aw mun ha' some clogs afore aw

go, too; look at thoose! They're a shame to be sin!"

Clogs

were freely given; and, in several cases, they were all that were asked

for. In three or four instances, the applicants said, after

receiving other relief, "Aw wish yo'd gi' me a pair o' clogs, Mr Eccles.

Aw've had to borrow these to come in." One woman pleaded hard for

two pair, saying, "Yon chylt's bar-fuut; an' he's witchod

(wet-shod), an' as ill as he con be." "Who's witchod?" asked the

chairman. "My husban' is," replied the woman; "an' he connot ston it

just neaw, yo mun let him have a pair iv yo con." "Give her

two pairs of clogs," said the chairman. Another woman took her clog

off, and held it up, saying,

"Look at that. We're o' walkin' o'th floor; an' smoor't wi' cowds."

One decent-looking old body, with a starved face, applied. The

chairman said, "Why, what's your son doing now? Has he catched no

rabbits lately?" "Nay, aw dunnot know 'at he does. Aw get

nought; an' it's me at wants summat, Mr Eccles," replied the old

woman, in a tremulous tone, with the water rising in her eyes.

"Well, come; we mustn't punish th' owd woman for her son," said one of the

guardians.

Various forms of the feebleness of age appeared before

the Board that day. "What's your son John getting, Mary?" said the

chairman to one old woman. "Whor?" replied she. "What's your

son John getting?" The old woman put her hand up to her ear, and

answered,

"Aw'm rayther deaf. What say'n yo?" It turned out that her son

was taken ill, and they were relieved.

In the course of inquiries I

found that the working people of Blackburn, as elsewhere in Lancashire,

nickname their workshops as well as themselves. The chairman asked a

girl where she worked at last, and the girl replied, "At th'

'Puff-an'-dart.'" "And what made you leave there?" "Whau, they

were woven up." One poor, pale fellow, a widower, said he had "worched"

a bit at "Bang-the-nation," till he was taken ill, and then they had

"shopped his place," that is, they had given his work to somebody else.

Another, when asked where he had been working, replied, "At Se'nacre Bruck

(Seven-acre Brook), wheer th' wild monkey were catched." It seems

that an ourang-outang which once escaped from some travelling menagerie,

was re-taken at this place.

I sat until the last application had

been disposed of, which was about half-past two in the afternoon.

The business had taken up nearly four hours and a half.

I had a good deal of conversation with people who were

intimately acquainted with the town and its people; and I was informed

that, in spite of the struggle for existence which is now going on, and

not unlikely to continue for some time, there are things happening amongst

the working people there, which do not seem wise, under existing

circumstances.

The people are much better informed now than they

were twenty years ago; but, still, something of the old blindness lingers

amongst them, here and there. For instance, at one mill, in

Blackburn, where the operatives were receiving 11s. a week for two looms,

the proprietor offered to give his workpeople three looms each, with a

guarantee for constant employment until the end of next August, if they

would accept one and a quarter pence less for the weaving of each piece.

This offer, if taken, would have raised their wages to an average of 14s.

6d. a week. It was declined, however, and they are now working, as

before, only on two looms each, with uncertainty of employment, at 11s. a

week. Perhaps it is too much to expect that such things should die

out all at once. But I heard also that the bricklayers' labourers at

Blackburn struck work last week for an advance of wages from 3s. 6d. a day

to 4s. a day. This seems very untimely, to say the least of it.

Apart from these things, there is, amongst all classes, a kind of cheery

faith in the return of good times, although nobody can see what they may

have to go through yet, before the clouds break. It is a fact that

there are more than forty new places ready, or nearly ready, for starting,

in and about Blackburn, when trade revives.

After dinner, I walked down Darwen Street. Stopping to

look at a music-seller's window, a rough-looking fellow, bareheaded and

without coat, came sauntering across the road from a shop opposite.

As he came near he shouted out, "Nea then Heaw go!" I turned round;

and, seeing that I was a stranger, he said, "Oh; aw thought it had bin

another chap." "Well," said I, "heaw are yo gettin' on, these

times?" "Divulish ill," replied he. "Th' little maisters are

runnin' a bit, some three, some four days. T'other are stopt o'

together, welly. . . . It's thin pikein' for poor folk just neaw.

But th' shopkeepers an' th' ale-heawses are in for it as ill as ony mak.

There'll be crashin' amung some on 'em afore lung."

After this, I

spent a few minutes in the market-place, which was "slacker" than usual,

as might be expected, for, as the Scotch proverb says, "Sillerless folk

gang fast through the market."

Later on, I went up to Bank Top, on

the eastern edge of the town, where many factory operatives reside.

Of course, there is not any special quarter where they are clustered in

such a manner as to show their condition as a whole. They are

scattered all round the town, living as near as possible to the mills in

which they are employed. Here I talked with some of the small

shopkeepers, and found them all more or less troubled with the same

complaint. One owner of a provision shop said to me, "Wi'n a deeal

o' brass owin'; but it's mostly owin' by folk at'll pay sometime.

An' then, th' part on 'em are doin' a bit yo known; an' they bring'n their

trifle o' ready brass to us; an' so we're trailin' on. But folk han

to trust us a bit for their stuff, dunnot yo see,―or else it would be 'Wo-up!'

soon." I heard of one beerhouse, the owner of which had only drawn

ls. 6d. during a whole week. His children were all factory

operatives, and all out of work. They were very badly off, and would

have been very glad of a few soup tickets; but, as the man said, "Who'd

believe me if aw were to go an' ax for relief?" I was told of two

young fellows, unemployed factory hands, meeting one day, when one said to

the other, "Thae favvurs hungry, Jone." "Nay, aw's do yet, for

that," replied Jone. "Well," continued the other; "keep thi heart

eawt of thi clogs, iv thi breeches dun eawt-thrive thi carcass a bit, owd

lad." "Aye," said Jone, "but what mun I do when my clogs gi'n way?"

"Whaw, thae mun go to th' Guardians; they'n gi tho a pair in a minute."

"Nay, by ――," replied Jone, "aw'll dee

furst!"

In the evening, I ran down to the beautiful suburb called

Pleasington, in the hope of meeting a friend of mine there; not finding

him, I came away by the eight o'clock train. The evening was

splendid, and it was cheering to see the old bounty of nature gushing

forth again in such unusual profusion and beauty, as if in pitiful charity

for the troubles of mankind. I never saw the country look so rich in

its spring robes as it does now.

AMONG THE PRESTON

OPERATIVES

CHAPTER III.

|

|

|

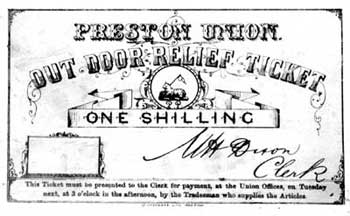

"This ticket must be presented

to the Clerk for payment, at the

Union Offices, on Tuesday

next, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon,

by the tradesman who supplies the articles."

Used by unemployed cotton

workers at Preston to buy

goods

during the Cotton Famine. |

Proud Preston, or Priest-town, on the banks of the beautiful Ribble, is a

place of many quaint customs, and of great historic fame. Its

character for pride is said to come from the fact of its having been, in

the old time, a favourite residence of the local nobles and gentry, and of

many penniless folk with long pedigrees. It was here that Richard Arkwright shaved chins at a halfpenny each, in the meantime working out

his bold and ingenious schemes, with patient faith in their ultimate

success. It was here, too, that the teetotal movement first began, with

Anderson for its rhyme-smith.

Preston has had its full share of the

changeful fortunes of England, and, like our motherland, it has risen

strongly out of them all. War's mad havoc has swept over it in many a

troubled period of our history. Plague, pestilence, and famine have

afflicted it sorely; and it has suffered from trade riots,

"plug-drawings," panics, and strikes of most disastrous kinds.

Proud

Preston ― the town of the Stanleys and the Hoghtons, and of "many a crest

that is famous in story" ― the town where silly King Jamie disported himself

a little, with his knights and nobles, during the time of his ruinous

visit to Hoghton Tower, ― Proud Preston has seen many a black day. But, from

the time when Roman sentinels kept watch and ward in their old camp at

Walton, down by the Ribble side, it has never seen so much wealth and so

much bitter poverty together as now.

The streets do not show this poverty;

but it is there. Looking from Avenham Walks, that glorious landscape

smiles in all the splendour of a rich spring-tide. In those walks the

nursemaids and children, and dainty folk, are wandering as usual airing

their curls in the fresh breeze; and only now and then a workless

operative trails by with chastened look. The wail of sorrow is not heard

in Preston market-place; but destitution may be found almost anywhere

there just now, cowering in squalid corners, within a few yards of

plenty ― as I have seen it many a time this week. The courts and alleys

behind even some of the main streets swarm with people who have hardly a

whole nail left to scratch themselves with.

Before attempting to tell something of what I saw whilst wandering amongst

the poor operatives of Preston, I will say at once, that I do not intend

to meddle with statistics. They have been carefully gathered, and often

given elsewhere, and there is no need for me to repeat them. But, apart

from these, the theme is endless, and full of painful interest. I hear on

all hands that there is hardly any town in Lancashire suffering so much as

Preston. The reason why the stroke has fallen so heavily here, lies in the

nature of the trade.

In the first place, Preston is almost purely a cotton

town. There are two or three flax mills, and two or three ironworks, of no

great extent; but, upon the whole, there is hardly any variety of

employment there to lighten the disaster which has befallen its one

absorbing occupation. There is comparatively little weaving in Preston; it

is a town mostly engaged in spinning. The cotton used there is nearly all

what is called "Middling American," the very kind which is now most scarce

and dear. The yarns of Preston are known by the name of "Blackburn

Counts." They range from 28's up to 60's, and they enter largely into the

manufacture of goods for the India market. These things partly explain why

Preston is more deeply overshadowed by the particular gloom of the times

than many other places in Lancashire.

About half-past nine on Tuesday

morning last, I set out with an old acquaintance to call upon a certain

member of the Relief Committee, in George's Ward. He is the manager of a

cotton mill in that quarter, and he is well known and much respected among

the working people. When we entered the mill-yard, all was quiet there,

and the factory was still and silent. But through the office window we

could see the man we wanted. He was accompanied by one of the proprietors

of the mill, turning over the relief books of the ward. I soon found that

he had a strong sense of humour, as well as a heart welling over with

tenderness. He pointed to some of the cases in his books.

The first was

that of an old man, an overlooker of a cotton mill. His family was

thirteen in number; three of the children were under ten years of age;

seven of the rest were factory operatives; but the whole family had been

out of work for several months. When in full employment the joint earnings

of the family amounted to 80s. a week; but, after struggling on in the

hope of better times, and exhausting the savings of past labour, they had

been brought down to the receipt of charity at last, and for sixteen weeks

gone by the whole thirteen had been living upon 6s. a week from the relief

fund. They had no other resource.

I went to see them at their own house

afterwards, and it certainly was a pattern of cleanliness, with the little

household gods there still. Seeing that house, a stranger would never

dream that the family was living on an average income of less than

sixpence a head per week. But I know how hard some decent folk will

struggle with the bitterest poverty before they will give in to it. The

old man came in whilst I was there. He sat down in one corner, quietly

tinkering away at

something he had in his hands. His old corduroy trousers were well

patched, and just new washed. He had very little to say to us, except that

"He could like to get summat to do; for he wur tired o' walkin' abeawt."

Another case was that of a poor widow woman, with five young children. This family had been driven from house to house, by increasing necessity,

till they had sunk at last into a dingy little hovel, up a dark court, in

one of the poorest parts of the town, where they huddled together about a

fireless grate to keep one another warm. They had nothing left of the

wreck of their home but two rickety chairs, and a little deal table reared

against the wall, because one of the legs was gone. In this miserable

hole ― which I saw afterwards ― her husband died of sheer starvation, as was

declared by the jury on the inquest. The dark, damp hovel where they had

crept to was scarcely four yards square; and the poor woman pointed to one

corner of the floor, saying, "He dee'd i' that nook." He died there, with

nothing to lie upon but the ground, and nothing to cover him, in that

fireless hovel. His wife and children crept about him, there, to watch him

die; and to keep him as warm as they could.

When the relief committee

first found this family out, the entire clothing of the family of seven

persons weighed eight pounds, and sold for fivepence, as rags. I saw the

family afterwards, at their poor place; and will say more about them

hereafter. He told me of many other cases of a similar kind. But, after

agreeing to a time when we should visit them personally, we set out

together to see the "Stone Yard," where there are many factory hands at

work under the Board of Guardians.

|

|

|

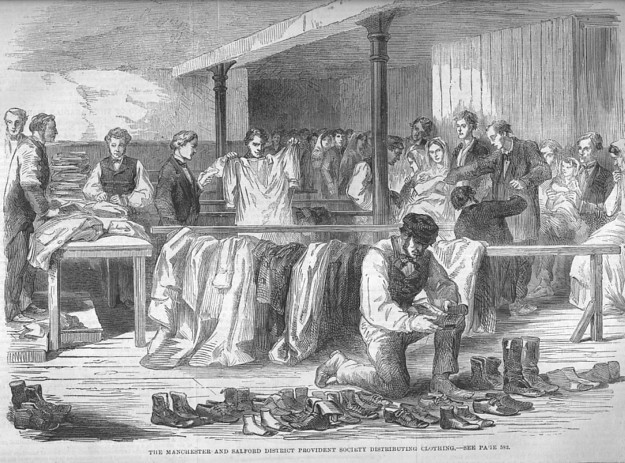

Unemployed

weavers selecting clothing.

Illustrated London News, November 29, 1862.

The last resort for the unemployed during the cotton

famine was to sell their clothing. As winter approached this could

have fatal consequences. National appeals such as Tiplady’s

letter

to The Times prompted sympathetic donors to send money and

parcels of unwanted clothing. There were reports from Darwen of

weavers wearing hunting coats and riding boots!

Courtesy of the 'Cotton Town digitization

project.' |

The "Stone Yard" is close by the Preston and Lancaster Canal. Here there

are from one hundred and seventy to one hundred and eighty, principally

young men, employed in breaking, weighing, and wheeling stone, for road

mending. The stones are of a hard kind of blue boulder, gathered from the

land between Kendal and Lancaster. The "Labour Master" told me that there

were thousands of tons of these boulders upon the land between Kendal and

Lancaster. A great deal of them are brought from a place called "Tewhitt

Field," about seven mile on "t' other side o' Lancaster."

At the "Stone

Yard" it is all piece-work, and the men can come and go when they like. As

one of the Guardians told me, "They can oather sit an' break 'em, or kneel

an' break 'em, or lie deawn to it, iv they'n a mind." The men can choose

whether they will fill three tons of the broken stone, and wheel it to the

central heap, for a shilling, or break one ton for a shilling.

The persons

employed here are mostly "lads an' leet-timber't chaps." The stronger men

are sent to work upon Preston Moor. There are great varieties of health

and strength amongst them. "Beside," as the Labour Master said, "yo'd

hardly believe what a difference there is i'th wark o' two men wortchin'

at the same heap, sometimes. There's a great deal i'th breaker, neaw; some

on 'em's more artful nor others. They finden out that they con break 'em

as fast again at after they'n getten to th' wick i'th inside. I have known

an' odd un or two, here, that could break four ton a day, ― an' many that

couldn't break one, ― but then, yo' know, th' men can only do accordin' to

their ability. There is these differences, and there always will be."

As

we stood talking together, one of my friends said that he wished "Radical

Jack" had been there. The latter gentleman is one of the guardians of the

poor, and superintendent of the "Stone Yard." The men are naturally

jealous of misrepresentation; and, the other day, as "Radical Jack" was

describing the working of the yard to a gentleman who had come to look at

the scene, some of the men overheard his words, and, misconceiving their

meaning, gathered around the superintendent, clamorously protesting

against what he had been saying. "He's lying!" said one. "Look at these honds!" cried another; "Wi'n they ever be fit to go to th' factory wi'

again?"

Others turned up the soles of their battered shoon, to show their cut and

stockingless feet. They were pacified at last; but, after the

superintendent had gone away, some of the men said much and more, and "if

ever he towd ony moor lies abeawt 'em, they'd fling him into th' cut."

The

"Labour Master" told me there was a large wood shed for the men to shelter

in when rain came on. As we were conversing, one of my friends exclaimed,

"He's here now!" "Who's here?" "Radical Jack." The superintendent was

coming down the road. He told me some interesting things, which I will

return to on another occasion. But our time was up. We had other places to

see.

As we came away, three old Irishwomen leaned against the wall at the

corner of the yard, watching the men at work inside. One of them was

saying, "Thim guardians is the awfullest set o' min in the world! A man

had better be transpoorted than come under 'em. An' thin, they'll try you,

an' try you, as if you was goin' to be hanged." The poor old soul had

evidently only a narrow view of the necessities and difficulties which

beset the labours of the Board of Guardians at a time like this.

On our

way back to town one of my friends told me that he "had met a sexton the

day before, and had asked him how trade was with him. The sexton replied

that it was "Varra bad ― nowt doin', hardly." "Well, how's that?" asked the

other. "Well, thae sees," answered the sexton, "Poverty seldom dees. There's far more kilt wi' o'er-heytin' an' o'er-drinkin' nor there is wi'

bein' pinched."

CHAPTER IV.

Leaving the "Stone Yard," to fulfil an engagement in another

part of the town, we agreed to call upon three or four poor folk, who

lived by the way; and I don't know that I could do better than say

something about what I saw of them.

As we walked along, one of my companions told me of an

incident which happened to one of the visitors in another ward, a few days

before. In the course of his round, this visitor called upon a

certain destitute family which was under his care, and he found the

husband sitting alone in the house, pale and silent. His wife had

been "brought to bed" two or three days before; and the visitor inquired

how she was getting on. "Hoo's very ill," said the husband.

"And the child," continued the visitor, "how is it?" "It's deeod,"

replied the man; "it dee'd yesterday." He then rose, and walked

slowly into the next room, returning with a basket in his hands, in which

the dead child was decently laid out. "That's o' that's laft

on it neaw," said the poor fellow. Then, putting the basket upon the

floor, he sat down in front of it, with his head between his hands,

looking silently at the corpse. Such things as these were the theme

of our conversation as we went along, and I found afterwards that every

visitor whom it was my privilege to meet, had some special story of

distress to relate, which came within his own appointed range of action.

In my first flying visit to that great melancholy field, I

could only glean such things as lay nearest to my hand, just then; but

wherever I went, I heard and saw things which touchingly testify what

noble stuff the working population of Lancashire, as a whole, is made of.

One of the first cases we called upon, after leaving the

"Stone Yard," was that of a family of ten ― man and wife, and eight

children. Four of the children were under ten years of age, ― five

were capable of working; and, when the working part of the family was in

full employment, their joint earnings amounted to 61s. per week.

But, in this case, the mother's habitual ill-health had been a great

expense in the household for several years.

This family belonged to a class of operatives ― a much larger

class than people unacquainted with the factory districts are likely to

suppose ― which will struggle, in a dumb, enduring way, to the death,

sometimes, before they will sacrifice that "immediate jewel of their

souls" ― their old independence, and will keep up a decent appearance to

the very last. These suffer more than the rest; for, in addition to

the pains of bitter starvation, they feel a loss which is more afflicting

to them even than the loss of food and furniture; and their sufferings are

less heard of than the rest, because they do not like to complain.

This family of ten persons had been living, during the last nine weeks,

upon relief amounting to 5s. a week. When we called, the mother and

one or two of her daughters were busy in the next room, washing their poor

bits of well-kept clothing. The daughters kept out of sight, as if

ashamed. It was a good kind of cottage, in a clean street, called "Maudland

Bank," and the whole place had a tidy, sweet look, though it was

washing-day. The mother told me that she had been severely afflicted

with seven successive attacks of inflammation, and yet, in spite of her

long-continued ill-health, and in spite of the iron teeth of poverty which

had been gnawing at them so long, for the first time, I have rarely seen a

more frank and cheerful countenance than that thin matron's, as she stood

there, wringing her clothes, and telling her little story.

The house they lived in belonged to their late employer,

whose mill stopped some time ago. We asked her how they managed to

pay the rent, and she said, "Why, we dunnot pay it; we cannot pay it, an'

he doesn't push us for it. Aw guess he knows he'll get it sometime.

But we owe'd a deal o' brass beside that. Just look at this shop

book. Aw'm noan freetend ov onybody seein' my acceawnts. An'

then, there's a great lot o' doctor's-bills i' that pot, theer.

Thoose are o' for me. There'll ha' to be some wark done afore things

can be fotched up again. . . . Eh; aw'll tell yo what, William,

(this was addressed to the visitor,) it went ill again th' grain wi' my

husband to goo afore th' Board. An' when he did goo, he wouldn't say

so mich. Yo known, folk doesn't like brastin' off abeawt theirsel'

o' at once, at a shop like that. . . . Aw think sometimes it's very

weel that four ov eawrs are i' heaven, ― we'n sich hard tewin' (toiling),

to poo through wi' tother, just neaw. But, aw guess it'll not last

for ever."

As we came away, talking of the reluctance shown by the

better sort of working people to ask for relief, or even sometimes to

accept it when offered to them, until thoroughly starved to it, I was told

of a visitor calling upon a poor woman in another ward; no application had

been made for relief, but some kind neighbour had told the committee that

the woman and her husband were "ill off." The visitor, finding that

they were perishing for want, offered the woman some relief tickets for

food; but the poor soul began to cry, and said; "Eh, aw dar not touch 'em;

my husban' would sauce me so! Aw dar not take 'em; aw should never

yer the last on't!"

When we got to the lower end of Hope Street, my guide stopped

suddenly, and said, "Oh, this is close to where that woman lives whose

husband died of starvation." Leading a few yards up the by-street,

he turned into a low, narrow entry, very dark and damp. Two turns

more brought us to a dirty, pent-up corner, where a low door stood open.

We entered there.

It was a cold, gloomy-looking little hovel. In my

allusion to the place last week I said it was "scarcely four yards

square." It is not more than three yards square. There was no

fire in the little rusty grate. The day was sunny, but no sunshine

could ever reach that nook, nor any fresh breezes disturb the pestilent

vapours that harboured there, festering in the sluggish gloom. In

one corner of the place a little worn and broken stair led up to a room of

the same size above, where, I was told, there was now some straw for the

family to sleep upon. But the only furniture in the house, of any

kind, was two rickety chairs and a little broken deal table, reared

against the stairs, because one leg was gone.

A quiet-looking, thin woman, seemingly about fifty years of

age, sat there, when we went in. She told us that she had buried

five of her children, and that she had six yet alive, all living with her

in that poor place. They had no work, no income whatever, save what

came from the Relief Committee. Five of the children were playing in

and out, bare-footed, and, like the mother, miserably clad; but they

seemed quite unconscious that anything ailed them. I never saw finer

children anywhere. The eldest girl, about fourteen, came in whilst

we were there, and she leaned herself bashfully against the wall for a

minute or two, and then slunk slyly out again, as if ashamed of our

presence. The poor widow pointed to the cold corner where her

husband died lately. She said that "his name was Tim Pedder.

His fadder name was Timothy, an' his mudder name was Mary. He was a

driver (a driver of boat-horses on the canal); but he had bin oot o' wark

a lang time afore he dee'd."

I found in this case, as in some others, that the poor body

had not much to say about her distress; but she did not need to say much.

My guide told me that when he first called upon the family, in the depth

of last winter, he found the children all clinging round about their

mother in the cold hovel, trying in that way to keep one another warm.

The time for my next appointment was now hard on, and we

hurried towards the shop in Fishergate, kept by the gentleman I had

promised to meet. He is an active member of the Relief Committee,

and a visitor in George's ward. We found him in. He had just

returned from the "Cheese Fair," at Lancaster. My purpose was to

find out what time on the morrow we could go together to see some of the

cases he was best acquainted with. But, as the evening was not far

spent, he proposed that we should go at once to see a few of those which

were nearest.

We set out together to Walker's Court, in Friargate.

The first place we entered was at the top of the little narrow court.

There we found a good-tempered Irish-woman sitting without fire, in her

feverish hovel. "Well, missis," said the visitor, "how is your

husband getting on?" "Ah, well, now, Mr. T――," replied she, "you

know, he's only a delicate little man, an' a tailor; an' he wint to work

on the moor, an' he couldn't stand it. Sure, it was draggin' the

bare life out of him. So, he says to me, one morning, "Catharine,"

says he, "I'll lave off this a little while, till I see will I be able to

get a job o' work at my own trade; an' maybe God will rise up some thin'

to put a dud o' clothes on us all, an' help us to pull through till the

black time is over us." So, I told him to try his luck, any way; for

he was killin' himself entirely on the moor. An' so he did try; for

there's not an idle bone in that same boy's skin. But, see this,

now; there's nothin' in the world to be had to do just now ― an' a dale

too many waitin' to do it ― so all he got by the change was losin' his

work on the moor. There is himself, an' me, an' the seven childer.

Five o' the childer is under tin year old. We are all naked; an' the

house is bare; an' our health is gone wi' the want o' mate. Sure it

wasn't in the likes o' this we wor livin' when times was good."

Three of the youngest children were playing about on the

floor. "That's a very fine lad," said I, pointing to one of them.

The little fellow blushed, and smiled, and then became very still and

attentive. "Ah, thin," said his mother, "that villain's the boy for

tuckin' up soup! The Lord be about him, an' save him alive to me, ―

the crayter! . . . An' there's little curly there,―the rogue!

Sure he'll take as much soup as any wan o' them. Maybe he wouldn't

laugh to see a big bowl forninst him this day." "It's very well they

have such good spirits," said the visitor. "So it is," replies the

woman, "so it is, for God knows it's little else they have to keep them

warm thim bad times."

|

|

Atlas Mill, Ashton-under-Lyne.

Courtesy Tameside Local Studies and Archives Centre. |

CHAPTER V.

The next house we called at in Walker's Court was much like

the first in appearance ― very little left but the walls, and that little,

such as none but the neediest would pick up, if it was thrown out to the

streets. The only person in the place was a pale, crippled woman;

her sick head, lapped in a poor white clout, swayed languidly to and fro.

Besides being a cripple, she had been ill six years, and now her husband,

also, was taken ill. He had just crept off to fetch medicine for the

two.

We did not stop here long. The hand of the Ancient

Master was visible in that pallid face; those sunken eyes, so full of

deathly languor, seemed to be wandering about in dim, flickering gazes,

upon the confines of an unknown world. I think that woman will soon

be "where the weary are at rest." As we came out, she said, slowly, and in

broken, painful utterances, that "she hoped the Lord would open the

heavens for those who had helped them."

A little lower down the court, we peeped in at two other

doorways. The people were well known to my companion, who has the

charge of visiting this part of the ward. Leaning against the

door-cheek of one of these dim, unwholesome hovels, he said, "Well, missis;

how are you getting on?" There was a tall, thin woman inside.

She seemed to be far gone in some exhausting illness. With slow

difficulty she rose to her feet, and, setting her hands to her sides,

gasped out, "My coals are done." He made a note, and said,

"I'll send

you some more." Her other wants were regularly seen to on a certain

day every week. Ours was an accidental visit.

We now turned up to another nook of the court, where my

companion told me there was a very bad case. He found the door fast.

We looked through the window into that miserable man-nest. It was

cold, gloomy, and bare. As Corrigan says, in the "Colleen Bawn,"

"There was nobody in ― but the fire ― and that was gone out." As we

came away, a stalwart Irishman met us at a turn of the court, and said to

my companion, "Sure, ye didn't visit this house." "Not to-day;"

replied the visitor. "I'll come and see you at the usual time."

The people in this house were not so badly off as some others. We

came down the steps of the court into the fresher air of Friargate again.

Our next walk was to Heatley Street. As we passed by a

cluster of starved loungers, we overheard one of them saying to another, "Sitho,

yon's th' soup-maister, gooin' a-seein' somebry." Our time was

getting short, so we only called at one house in Heatley Street, where

there was a family of eleven ― a decent family, a well-kept and orderly

household, though now stript almost to the bare ground of all worldly

possession, sold, bitterly, piecemeal, to help to keep the bare life

together, as sweetly as possible, till better days.

The eldest son is twenty-seven years of age. The whole

family has been out of work for the last seventeen weeks, and before that,

they had been working only short time for seven months. For thirteen

weeks they had lived upon less than one shilling a head per week, and I am

not sure that they did not pay the rent out of that; and now the income of

the whole eleven is under 16s., with rent to pay. In this house they

hold weekly prayer-meetings. Thin picking ― one shilling a week, or

less ― for all expenses, for one person. It is easier to write about

it than to feel what it means, unless one has tried it for three or four

months.

Just round the corner from Heatley Street, we stopped at the

open door of a very little cottage. A good-looking young Irishwoman

sat there, upon a three-legged stool, suckling her child. She was

clean; and had an intelligent look. "Let's see, missis," said the

visitor, "what do you pay for this nook?" "We pay eighteenpence a

week ― and they will have it ― my word." "Well, an' what

income have you now?" "We have eighteenpence a head in the week, an'

the rent to pay out o' that, or else they'll turn us out."

Of course, the visitor knew that this was true; but he wanted

me to hear the people speak for themselves.

"Let's see, Missis Burns, your husband's name is Patrick,

isn't it?" "Yes, sir; Patrick Burns." "What! Patrick Burns,

the famous foot-racer?" The little woman smiled bashfully, and

replied, "Yes, sir; I suppose it is."

|

|

View of Hollins Mill, Mossley.

Courtesy Tameside Local Studies and Archives Centre. |

With respect to what the woman said about having to pay her

rent or turn out, I may remark, in passing, that I have not hitherto met

with an instance in which any mill-owner, or wealthy man, having cottage

property, has pressed the unemployed poor for rent. But it is well

to remember that there is a great amount of cottage property in Preston,

as in other manufacturing towns, which belongs to the more provident class

of working men. These working men, now hard pressed by the general

distress, have been compelled to fall back upon their little rentals,

clinging to them as their last independent means of existence. They

are compelled to this, for, if they cannot get work, they cannot get

anything else, having property. These are becoming fewer, however,

from day to day. The poorest are hanging a good deal upon those a

little less poor than themselves; and every link in the lengthening chain

of neediness is helping to pull down the one immediately above it.

There is, also, a considerable amount of cottage property in Preston,

belonging to building societies, which have enough to do to hold their own

just now. And then there is always some cottage property in the

hands of agents.

Leaving Heatley Street, we went to a place called "Seed's

Yard." Here we called upon a clean old stately widow, with a calm, sad

face. She had been long known, and highly respected, in a good

street, not far off, where she had lived for twenty-four years, in fair

circumstances, until lately. She had always owned a good houseful of

furniture; but, after making bitter meals upon the gradual wreck of it,

she had been compelled to break up that house, and retire with her five

children to lodge with a lone widow in this little cot, not over three

yards square, in "Seed's Yard," one of those dark corners into which

decent poverty is so often found now, creeping unwillingly away from the

public eye, in the hope of weathering the storm of adversity, in penurious

independence.

The old woman never would accept relief from the parish,

although the whole family had been out of work for many months. One

of the daughters, a clean, intelligent-looking young woman, about

eighteen, sat at the table, eating a little bread and treacle to a cup of

light-coloured tea, when we went in; but she blushed, and left off until

we had gone ― which was not long after. It felt almost like

sacrilege to peer thus into the privacies of such people; but I hope they

did not feel as if it had been done offensively.

We called next at the cottage of a hand-loom weaver ― a poor

trade now in the best of times ― a very poor trade ― since the days when

tattered old "Jem Ceawp" sung his pathetic song of "Jone o' Greenfeelt" ―

|

"Aw'm a poor cotton weighver, as ony one knows;

We'n no meight i'th heawse, an' we'n worn eawt er clothes;

We'n live't upo nettles, while nettles were good;

An' Wayterloo porritch is th' most of er food;

This clemmin' and starvin',

Wi' never a farthin' ―

It's enough to drive ony mon mad." |

This family was four in number ― man, wife, and two children. They

had always lived near to the ground, for the husband's earnings at the

loom were seldom more than 7s. for a full week. The wife told us

that they were not receiving any relief, for she said that when her

husband "had bin eawt o' wark a good while he turn't his hond to shaving;"

and in this way the ingenious struggling fellow had scraped a thin living

for them during many months. "But," said she, " it brings varra

little in, we hev to trust so much. He shaves four on 'em for a

haw-penny, an' there's a deal on 'em connot pay that. Yo know,

they're badly off ― (the woman seemed to think her circumstances rather

above the common kind); an' then," continued she, "when they'n run up a

shot for three-hawpence or twopence or so, they cannot pay it o' no shap,

an' so they stoppen away fro th' shop. They cannot for shame come,

that's heaw it is; so we lose'n their custom till sich times as summat

turns up at they can raise a trifle to pay up wi'. . . . He has nobbut one

razzor, but it'll be like to do." Hearken this, oh, ye spruce

Figaros of the city, who trim the clean, crisp whiskers of the well-to-do!

Hearken this, ye dainty perruquiers, "who look so brisk, and smell so

sweet," and have such an exquisite knack of chirruping, and lisping, and

sliding over the smooth edge of the under lip, ― and, sometimes, agreeably

too, ― "an infinite deal of nothing," ― ye who clip and anoint the hair of

Old England's curled darlings! Eight chins a penny; and three

months' credit! A bodle a piece for mowing chins overgrown with hair

like pin-wire, and thick with dust; how would you like that? How

would you get through it all, with a family of four, and only one razor?

The next place we called at was what my friend described, in

words that sounded to me, somehow, like melancholy irony, ― as "a poor

provision shop." It was, indeed, a poor shop for provender. In

the window, it is true, there were four or five empty glasses, where

children's spice had once been. There was a little deal shelf here

and there; but there were neither sand, salt, whitening, nor pipes.

There was not the ghost of a farthing candle, nor a herring, nor a marble,

nor a match, nor of any other thing, sour or sweet, eatable or saleable

for other uses, except one small mug full of buttermilk up in a corner ―

the last relic of a departed trade, like the "one rose of the wilderness,

left on its stalk to mark where a garden has been." But I will say

more about this in the next chapter.

|

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)