|

[Previous

Page]

AMONG THE PRESTON

OPERATIVES (cont.)

CHAPTER VI.

Returning to the little shop mentioned in my last ― the

"little provision shop," where there was nothing left to eat ― nothing,

indeed, of any kind, except one mug of buttermilk, and a miserable remnant

of little empty things, which nobody would buy; four or five glass bottles

in the window, two or three poor deal shelves, and a doleful little

counter, rudely put together, and looking as if it felt, now, that there

was nothing in the world left for it but to become chips at no distant

date. Everything in the place had a sad, subdued look, and seemed

conscious of having come down in the world, without hope of ever rising

again; even the stript walls appeared to look at one another with a stony

gaze of settled despair.

|

THE TIMES

LONDON, SATURDAY, ARIL 19 1862.

The almost incessant rain has abated; the sky is clear and bright

the spring flowers are out in spite of the cold, and the bloom is on

every shrub and fruit-bearing tree. So far there never was a

pleasantly Easter. But while the seasons run their course

there is one season not returning. A population of millions is

now suffering as much as if the sun had reappeared shorn of half its

beams or Nature had suddenly shown signs of decay. A terrible

cotton dearth deprives countless hands, thorough populous districts

and crowded cities, of the means of earning bread. It is all

the same as if the grain had perished by blight or the root by rot;

for, though though the food is in the country, or within purchasable

distance, the means of purchase are not to be found; and people

perish, as was said in the days of "Protection," in the midst of

full granaries and piles of provisions. An inscrutable PROVIDENCE

ever varies the dispensation. It was once a fiscal system;

then it was a bad harvest; then it was an overstocked market; then

it was the periodical rebellion of labour against capital.

Ingenious men endeavoured to forecast the next shape of calamity,

and imagined a quarrel with the United States, in which they would

attempt to starve us out, and humble us to terms by withholding

their cotton. The Americans themselves grew proud of our

dependence. But that has now happened which neither happened

before nor so much as occurred to any prophets of ill. The

cotton crop has been shut up on the soil that that bore it by a

disruption of the States themselves; and for once we are the "baser

nature" that

"comes

"Between the pass and fell incensed points

"Off mighty opposites." |

The myriads who a few years ago were reading with tears the tragic

tale of Negro suffering and wrong little thought that they would one

day exchange a sentimental for an actual participation in that

story. The American Abolitionist, having preached to them in

vain, now enforces a reluctant consistency, and denies them

slave-grown cotton. The result is a national disaster.

It does not seem to abate, and no one can say what pass it will come

to. For a time there was hope, founded chiefly on the

difficulty of supposing that so estrange a state of things could

last long. The war was to end soon by the mere process of

exhaustion. The blockade was to be set at nought. There

was to be an European intervention. There might be a

circuitous traffic. Perhaps the calculations were wrong.

Perhaps the stocks where an invitation. Probably a hundred

times that number of victims are now suffering only a more

protracted form of the same tortures, and we are almost afraid to

plead for them, there are so many scruples and difficulties.

Has not cotton produced a wealth and an aristocracy of its own?

Has it not been stated, without contradiction, that five millions,

and, indeed, much more, have been by this very rise in prices which

we call the cotton death? Have not some of the millowners

themselves laid up stocks, and then sold them at a great profit ―

nay, even for exportation to New York? Were it our object to

harden the heart, there is much that might be said; but such

statements very often have no just relevance to the cease, for none

can tell under what circumstances cotton has been bought or sold,

and the public have not a right to require that it should be worked

at a loss. Again, we might be told, with more or less truth,

that much of the present distress is the result of improvident

habits on the part of the people, who for some years past have been

earning extraordinarily high wages, and have neglected to lay by.

But all this is no answer to the question before us. The fact

of an unprecedented distress is what we have to do with. Thus

far, the local resources have not failed. But, as the poor

girls said, "Cannot we do something to help them?" There is a

cry for Englishwomen from British Columbia, from Queensland, from

Melbourne, and from other prosperous colonies. We hear now and

then of a hundred thousand pounds, more or less, going abegging, and

positively craving the advise and of good sensible people for its

judicious employment. Would that something would inspire a

millionaire or two to address themselves to the noble and necessary

work of supplying helpmeets for all these scattered and solitary ADAMS!

But we cannot wait for this. We must look ahead and watch the

peril in our course. Here is a fearful mass of destitution

that may an day prove too great for the local resource. It

must not be too soon adopted by the State, but it may be too late,

and meanwhile it must not be forgotten by any whom it many concern.

|

But there was a clean, matronly woman in the place, gliding about from

side to side with a cloth in her hands, and wiping first one, then

another, of these poor little relics of better days in a caressing way.

The shop had been her special care when times were good, and she clung

affectionately to its ruins still. Besides, going about cleaning and

arranging the little empty things in this way looked almost like doing

business. But, nevertheless, the woman had a cheerful, good-humoured

countenance. The sunshine of hope was still warm in her heart;

though there was a touch of pathos in the way she gave the little rough

counter another kindly wipe now and then, as if she wished to keep its

spirits up; and in the way she looked, now at the buttermilk mug, then at

the open door, and then at the four glass bottles in the window, which had

been gazed at so oft and so eagerly by little children outside, in the

days when spice was in them. . . .

The husband came in from the little back room. He

was a hardy, frank-looking man, and, like his wife, a trifle past middle

age, I thought; but he had nothing to say, as he stood there with his

wife, by the counter side. She answered our questions freely and

simply, and in an uncomplaining way, not making any attempt to awaken

sympathy by enlarging upon the facts of their condition. Theirs was

a family of seven ― man, wife, and five children. The man was a

spinner; and his thrifty wife had managed the little shop, whilst he

worked at the mill. There are many striving people among the factory

operatives, who help up the family earnings by keeping a little shop in

this way. But this family was another of those instances in which working

people have been pulled down by misfortune before the present crisis came

on. Just previous to the mills beginning to work short time, four of

their five children had been lying ill, all at once, for five months; and,

before that trouble befell them, one of the lads had two of his fingers

taken off, whilst working at the factory, and so was disabled a good

while. It takes little additional weight to sink those whose chins

are only just above water; and these untoward circumstances oiled the way

of this struggling family to the ground, before the mills stopped. A

few months' want of work, with their little stock of shop stuff oozing

away ― partly on credit to their poor neighbours, and partly to live upon

themselves ― and they become destitute of all, except a few beggarly

remnants of empty shop furniture.

Looking round the place, I said, "Well, missis, how's

trade?" "Oh, brisk," said she; and then the man and his wife smiled

at one another. "Well," said I, "yo'n sowd up, I see, heawever."

"Ay," answered she, "we'n sowd up, for sure ― a good while sin';" and then

she smiled again, as if she thought she had said a clever thing.

They had been receiving relief from the parish several weeks; but she told

me that some ill-natured neighbour had "set it eawt," that they had sold

off their stock out of the shop, and put the money into the bank.

Through this report, the Board of Guardians had "knocked off" their relief

for a fortnight, until the falsity of the report was made clear.

After that, the Board gave orders for the man and his wife and three of

the children to be admitted to the workhouse, leaving the other two lads,

who were working at the "Stone Yard," to "fend for theirsels," and find

new nests wherever they could. This, however, was overruled

afterwards; and the family is still holding together in the empty shop, ―

receiving from all sources, work and relief, about 13s. a week for the

seven, ― not bad, compared with the income of very many others.

It is sad to think how many poor families get sundered

and scattered about the world in a time like this, never to meet again.

And the false report respecting this family in the little shop, reminds me

that the poor are not always kind to the poor. I learnt, from a

gentleman who is Secretary to the Relief Committee of one of the wards,

that it is not uncommon for the committees to receive anonymous letters,

saying that so and so is unworthy of relief, on some ground or other.

These complaints were generally found to be either wholly false, or

founded upon some mistake. I have three such letters now before me.

The first, written on a torn scrap of ruled paper, runs thus: ―

"May 19th, 1862. ― If you please be so kind as to look

after ― Back Newton Street Formerly a Resident of ―

as i think he is not Deserving Relief. ― A Ratepayer."

In each case I give the spelling, and everything else, exactly as in the

originals before me, except the names. The next of these epistles

says: ―

"Preston, May 29th. ― Sir, I beg to inform you that ―

, of Park Road, in receipt from the Relief Fund, is a very unworthy

person, having worked two days since the 16 and drunk the remainder and

his wife also; for the most part, he has plenty of work for himself his

wife and a journeyman but that is their regular course of life. And the S

― _s have all their family working full time. Yours respectfully."

These last two are anonymous. The next is written in a very good

hand, upon a square piece of very blue writing paper. It has a name

attached, but no address: ―

"Preston, June 2nd, 1862. ― Mr. Dunn, ― Dear Sir, Would you

please to inquire into the case of ― , of ― .the are a family

of 3 the man work four or more days per week on the moor the woman works 6

days per week at Messrs Simpsons North Road the third is a daughter 13 or

14 should be a weaver but to lasey she has good places such as Mr. Hollins

and Horrocks and Millers as been sent a way for being to lasey. the man

and woman very fond of drink. I as a Nabour and a subscriber do not think

this a proper case for your charity. Yours truly, ― ."

The committee could not find out the writer of this, although a name is

given. Such things as these need no comment.

The next house we called at was inhabited by an old widow and

her only daughter. The daughter had been grievously afflicted with

disease of the heart, and quite incapable of helping herself during the

last eleven years. The poor worn girl sat upon an old tattered kind

of sofa, near the fire, panting for breath in the close atmosphere.

She sat there in feverish helplessness, sallow and shrunken, and unable to

bear up her head. It was a painful thing to look at her. She

had great difficulty in uttering a few words. I can hardly guess

what her age may be now; I should think about twenty-five.

Mr Toulmin, one of the visitors who accompanied me to

the place, reminded the young woman of his having called upon them there

more than four years ago, to leave some bedding which had been bestowed

upon an old woman by a certain charity in the town. He saw no more

of them after that, until the present hard times began, when he was

deputed by the Relief Committee to call at that distressed corner amongst

others in his own neighbourhood; and when he first opened the door, after

a lapse of four years, he was surprised to find the same young woman,

sitting in the same place, gasping painfully for breath, as he had last

seen her. The old widow had just been able to earn what kept soul

and body together in her sick girl and herself, during the last eleven

years, by washing and such like work. But even this resource had

fallen away a good deal during these bad times; there are so many poor

creatures like herself, driven to extremity, and glad to grasp at any

little bit of employment which can be had. In addition to what the

old woman could get by a day's washing now and then, she received 1s. 6d.

a week from the parish. Think of the poor old soul trailing about

the world, trying to "scratch a living" for herself and her daughter by

washing; and having to hurry home from her labour to attend to that sick

girl through eleven long years. Such a life is a good deal like a

slow funeral. It is struggling for a few breaths more, with the

worms crawling over you. And yet I am told that the old woman was

not accustomed to "make a poor mouth," as the saying goes. How true

it is that "a great many people in this world have only one form of

rhetoric for their profoundest experiences, namely ― to waste away and

die."

|

THE TIMES,

April 23, 1862.

DISTRESS

IN LANCASHIRE.

―――◊―――

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir,—I have read with feelings of the deepest interests and

gratitude your leader of Saturday, the 19th inst., on the subject of

the present distress existing in Lancashire. We owe you many

thanks for that well-timed and useful article. I trust it will

prove an appeal that will call forth the benevolence of the wealthy.

It would be wrong in me to expect that the town in which I live

should receive more than a fair proportion of help, because,

unhappily, I know that many places are in the same distressed

condition. Blackburn has witnessed many sad reverses in the

cotton manufacturing business, but never since them Bank's panic of

1825-6 has it experienced so extensive and disastrous a reverse as

that which now exist, and which has reduced a large proportion of

the operatives to pecuniary ruin and nearly absolute starvation.

At the time to which I have referred in 1826, the town comprised

about 23,000 or 30,000 inhabitants, and, for the period of nine

months, 14,000 of that number were maintained by a distribution of

oatmeal, bread, and bacon. The Government of that day, through

the late Sir Robert Peel, sent £1,000 to our aid. Most

unfortunately for themselves and for the town, the distressed

handloom weavers where persuaded that their calamity was caused by

the introduction of the powerloom, and, goaded by evil counsels,

aggravated by hunger and distress, they madly sought remedy in the

destruction of that machinery—an act which eventually plunged them

into deeper difficulties and retarded the employment of capital for

some time. No such perverse and wrong-headed conduct operates

at the present crisis. Thrown into adversely by no act or

circumstance over which they have any control, we see a numerous

and, for the most part, an orderly and industries population

deprived of work, reduced to poverty—to abject mendicity—while their

fellow operatives, a little more fortunate, are subsisting on wages

derived from short time, averaging about threes days per week,—wages

that barely realize sufficient for food and rent. The number

of persons absolutely dependent on the pittance allowed by the Board

of Guardians and the dole from the Relief Fund is over 10,000, that

is about one-sixth of the whole population, and I may add that at

least 20,000 are on short time. Consequently, one-half of the

people are sufferers in the general distress. This fearful

state of things, had it happened some years ago, I apprehend would

have led to serious bread riots, but thanks to the advance of

education, and, let us say, to the good sense of the operatives,

this appalling distress has hitherto been borne with silent,

enduring, and exemplary patience and resignation. No threats,

no outbreaks, no violent popular demonstration have been manifested;

but ever cheerfulness to a certain extent and a wonderful feeling of

helping one another have marked the conduct of the suffering

unemployed. Let it be borne in mind by your fair readers, that

a large proportion of the hands are factory girls whose ages range

from 13 to 20 years, and who are capable of earning an average of

from 10s. to 14s. per week, girls who have been carefully

disciplined in habits of industry from early childhood, and are now,

for the most part, scholars and teachers in our Sunday schools.

It is gainful to reflect that these factory girls have to grieve

over the loss of their neat apparel as article after article is

pawned or sold for bread. I may give one touching instance of

this description. Being a bookseller, I was applied to by a

modest girl, 17 or 18 years old, to purchase from her a Wesleyan

Hymn-book. She had been out of work for 16 weeks, and there

were two companions with her in the same unhappy plight. An

aged gentleman, himself the father of several grown-up daughters,

happened to be present and commiserated her case. Probably

this little Hymn-book, and her Bible, with a few religious

periodicals were all the library of this poor girl, all to be sold

for food; possibly her long-cherished Bible will be the last

sacrifice designed to pinching poverty and distress. Cannot

your matronly readers feel for her position and for many such poor

factory girls; cannot some of them lend a helping hand? It is

hard to sit at home all the livelong day, sighing for work, pinched

by hunger, and surrounded by fearful temptations, timid and

trembling, yet forced to the cruel necessity of seeking alms.

I am sure there is generosity enough in this land of ours to meet

this fearful aspect of affairs. Look at the noble munificence

shown to the widows and orphans of the colliers who perished in the

Hartley coalpit. A little help will assist many an

aching parent's heart, who trembles as he looks aground upon his

grown up family, and contemplates with sad dismay the breaking up of

his humble household and the utter annihilations of his own and his

children's home. I would in conclusions of my appeal just

advert to the fact that during the Crimean war the factory

operatives of Blackburn contributed a large amount to the Royal

Patriotic Fund for our suffering soldiers. I send you a

printed pamphlet (18 pages) exhibiting the contributions of one part

of the town — Park-ward, where you have sums from one penny upwards,

amounting in the whole to £549. 16s. 9d., by 2,800 contributors.

I regret not being able to give you the particulars of the other

five wards; but I may say the sympathy and liberality was alike

universal. In the late famine in India, also, the operatives

did their share, and I am happy to state that even now those

operatives in work are subscribing handsomely to their fellow

workmen in adversity. If these statements shall induce the

charitably disposed to help in this "hour of need," they may rely

upon it many grateful prayers for their prosperity will be offered

up, and by none more than by

Your most humble and obedient servant.

CHARLES TIPLADY,

A Member of

the Relief Committee.

53,

Church-street, Blackburn. |

Our next visit was to an Irish family. There was an old

woman in, and a flaxen-headed lad about ten years of age. She was

sitting upon a low chair, ― the only seat in the place, ― and the tattered

lad was kneeling on the ground before her, whilst she combed his hair out.

"Well, missis, how are you getting on amongst it?" "Oh, well, then,

just middlin', Mr T. Ye see, I am busy combin' this boy's hair a

bit, for 'tis gettin' like a wisp o' hay."

There was not a vestige of furniture in the cottage,

except the chair the old woman sat on. She said, "I did sell the

childer's bedstead for 2s. 6d.; an' after that I sold the bed from under

them for 1s. 6d., just to keep them from starvin' to death. The

childer had been two days without mate then, an' faith I couldn't bear it

any longer. After that I did sell the big pan, an' then the new

rockin' chair, an' so on, one thing after another, till all wint entirely,

barrin' this I am sittin' on, an' they wint for next to nothin' too.

Sure, I paid 9s. 6d. for the bed itself, which was sold for 1s. 6d.

We all sleep on straw now."

This family was seven in number. The mill at

which they used to work had been stopped about ten months. One of

the family had found employment at another mill, three months out of the

ten, and the old man himself had got a few days' work in that time.

The rest of the family had been wholly unemployed, during the ten months.

Except the little money this work brought in, and a trifle raised now and

then by the sale of a bit of furniture when hunger and cold pressed them

hard, the whole family had been living upon 5s. a week for the last ten

months. The rent was running on. The eldest daughter was

twenty-eight years of age. As we came away Mr Toulmin said to me,

"Well, I have called at that house regularly for the last sixteen weeks,

and this is the first time I ever saw a fire in the place. But the

old man has got two days' work this week ― that may account for the fire."

It was now close upon half-past seven in the evening, at

which time I had promised to call upon the Secretary of the Trinity Ward

Relief Committee, whose admirable letter in the London Times,

attracted so much attention about a month ago. I met several members

of the committee at his lodgings, and we had an hour's interesting

conversation. I learnt that, in cases of sickness arising from mere

weakness, from poorness of diet, or from unsuitableness of the food

commonly provided by the committee, orders were now issued for such kind

of "kitchen physic" as was recommended by the doctors. The committee

had many cases of this kind. One instance was mentioned, in which,

by the doctor's advice, four ounces of mutton chop daily had been ordered

to be given to a certain sick man, until further notice. The thing

went on and was forgotten, until one day, when the distributor of food

said to the committeeman who had issued the order, "I suppose I must

continue that daily mutton chop to so-and-so?" "Eh, no; he's been

quite well two months?" The chop had been going on for ninety-five

days.

We had some talk with that class of operatives who are both

clean, provident, and "heawse-preawd," as Lancashire folk call it.

The Secretary told me that he was averse to such people living upon the

sale of their furniture; and the committee had generally relieved the

distress of such people, just as if they had no furniture, at all.

He mentioned the case of a family of factory operatives, who were all

fervent lovers of music, as so many of the working people of Lancashire

are. Whilst in full work, they had scraped up money to buy a piano;

and, long after the ploughshare of ruin had begun to drive over the little

household, they clung to the darling instrument, which was such a source

of pure pleasure to them, and they were advised to keep it by the

committee which relieved them. "Yes," said another member of the

committee, "but I called there lately, and the piano's gone at last."

Many interesting things came out in the course of our

conversation. One mentioned a house he had called at, where there

was neither chair, table, nor bed; and one of the little lads had to hold

up a piece of board for him to write upon. Another spoke of the

difficulties which "lone women" have to encounter in these hard times.

"I knocked so-and-so off my list," said one of the committee, "till I had

inquired into an ill report I heard of her. But she came crying to

me; and I found out that the woman had been grossly belied." Another

(Mr Nowell) told of a house on his list, where they had no less than one

hundred and fifty pawn tickets. He told, also, of a moulder's

family, who had been all out of work and starving so long, that their poor

neighbours came at last and recommended the committee to relieve them, as

they would not apply for relief themselves. They accepted relief

just one week, and then the man came and said that he had a prospect

of work; and he shouldn't need relief tickets any longer. It was

here that I heard so much about anonymous letters, of which I have given

you three samples.

Having said that I should like to see the soup kitchen, one

of the committee offered to go with me thither at six o'clock the next

morning; and so I came away from the meeting in the cool twilight.

Old Preston looked fine to me in the clear air of that

declining day. I stood a while at the end of the "Bull" gateway.

There was a comical-looking little knock-kneed fellow in the middle of the

street ― a wandering minstrel, well known in Preston by the name of

"Whistling Jack." There he stood, warbling and waving his band, and

looking from side to side, ― in vain. At last I got him to whistle

the "Flowers of Edinburgh." He did it, vigorously; and earned his

penny well. But even "Whistling Jack" complained of the times.

He said Preston folk had "no taste for music." But he assured me the

time would come when there would be a monument to him in that town.

CHAPTER VII.

About half-past six I found my friend waiting at the end of

the "Bull" gateway. It was a lovely morning. The air was cool

and clear, and the sky was bright. It was easy to see which was the

way to the soup kitchen, by the stragglers going and coming. We

passed the famous "Orchard," now a kind of fairground, which has been the

scene of so many popular excitements in troubled times. All was

quiet in the "Orchard" that morning, except that, here, a starved-looking

woman, with a bit of old shawl tucked round her head, and a pitcher in her

hand, and there, a bare-footed lass, carrying a tin can, hurried across

the sunny space towards the soup kitchen. We passed a new inn,

called "The Port Admiral." On the top of the building there were three

life-sized statues ― Wellington and Nelson, with the Greek slave between

them ― a curious companionship. These statues reminded me of a

certain Englishman riding through Dublin, for the first time, upon an

Irish car. "What are the three figures yonder?" said he to the

car-boy, pointing to the top of some public building. "Thim three is

the twelve apostles, your honour," answered the driver. "Nay, nay,"

said the traveller, "that'll not do. How do you make twelve out of

three?" "Bedad," replied the driver, "your honour couldn't expect

the whole twelve to be out at once such a murtherin' wet day as this." But

we had other things than these to think of that day.

|

|

|

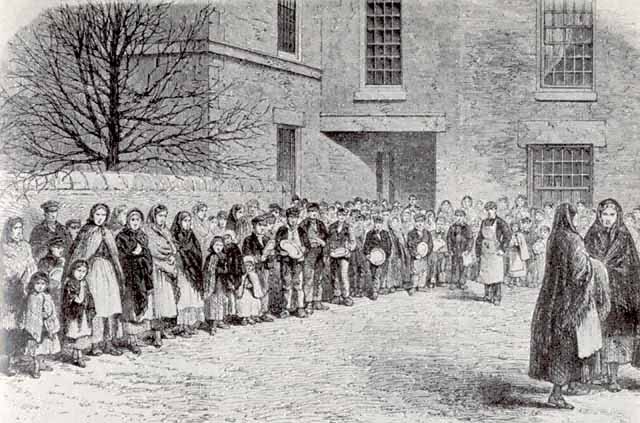

"The

Cotton Famine: operatives waiting for their breakfast in Mr

Chapman's Courtyard,

Mottram, near Manchester"

― Illustrated London News,

1862.

Courtesy of the 'Cotton Town digitzation project'. |

As we drew near the baths and washhouses, where the soup

kitchen is, the stream of people increased. About the gate there was

a cluster of melancholy loungers, looking cold and hungry. They were

neither going in nor going away. I was told afterwards that many of

these were people who had neither money nor tickets for food ― some of

them wanderers from town to town; anybody may meet them limping, footsore

and forlorn, upon the roads in Lancashire, just now ― houseless wanderers,

who had made their way to the soup kitchen to beg a mouthful from those

who were themselves at death's door. In the best of times there are

such wanderers; and, in spite of the generous provision made for the

relief of the poor, there must be, in a time like the present, a great

number who let go their hold of home (if they have any), and drift away in

search of better fortune, and, sometimes, into irregular courses of life,

never to settle more.

Entering the yard, we found the wooden sheds crowded with

people at breakfast ― all ages, from white-haired men, bent with years, to

eager childhood, yammering over its morning meal, and careless till the

next nip of hunger came. Here and there a bonny lass had crept into

the shade with her basin; and there was many a brown-faced man, who had

been hardened by working upon the moor or at the "stone-yard." "Theer,

thae's shap't that at last, as how?" said one of these to his friend, who

had just finished and stood wiping his mouth complacently. "Shap't

that," replied the other, "ay, lad, aw can do a ticket and a hafe (three

pints of soup) every morning."

Five hundred people breakfast in the sheds alone, every day.

The soup kitchen opens at five in the morning, and there is always a crowd

waiting to get in. This looks like the eagerness of hunger. I

was told that they often deliver 3000 quarts of soup at this kitchen in

two hours. The superintendent of the bread department informed me

that, on that morning, he had served out two thousand loaves, of 3lb.

11oz. each. There was a window at one end, where soup was delivered

to such as brought money for it instead of tickets. Those who came

with tickets ― by far the greatest number ― had to pass in single file

through a strong wooden maze, which restrained their eagerness, and

compelled them to order. I noticed that only a small proportion of

men went through the maze; they were mostly women and children. There was

many a fine, intelligent young face hurried blushing through that maze ―

many a bonny lad and lass who will be heard of honourably hereafter.

The variety of utensils presented showed that some of the

poor souls had been hard put to it for things to fetch their soup in.

One brought a pitcher; another a bowl; and another a tin can, a world too

big for what it had to hold. "Yo mun mind th' jug," said one old

woman; "it's cracked, an' it's noan o' mine." "Will ye bring me

some?" said a little, light-haired lass, holding up her rosy neb to the

soupmaster. "Aw want a ha'poth," said a lad with a three-quart can

in his hand. The benevolent-looking old gentleman who had taken the

superintendence of the soup department as a labour of love, told me that

there had been a woman there by half-past five that morning, who had come

four miles for some coffee. There was a poor fellow breakfasting in

the shed at the same time; and he gave the woman a thick shive of his

bread as she went away. He mentioned other instances of the same

humane feeling; and he said, "After what I have seen of them here, I say,

'Let me fall into the hands of the poor.'"

|

"They who, half-fed, feed the breadless, in the travail of distress;

They who, taking from a little, give to those who still have less;

They who, needy, yet can pity when they look on greater need;

These are Charity's disciples, ― these are Mercy's sons indeed." |

We returned to the middle of the town just as the shopkeepers

in Friargate were beginning to take their shutters down. I had

another engagement at half-past nine. A member of the Trinity Ward

Relief Committee, who is master of the Catholic school in that ward, had

offered to go with me to visit some distressed people who were under his

care in that part of the town.

We left Friargate at the appointed time. As we came

along there was a crowd in front of Messrs Wards', the fishmongers.

A fine sturgeon had just been brought in. It had been caught in the

Ribble that morning. We went in to look at the royal fish. It

was six feet long, and weighed above a hundred pounds. I don't know

that I ever saw a sturgeon before. But we had other fish to fry; and

so we went on.

The first place we called at was a cellar in Nile Street.

"Here," said my companion, "let us have a look at old John." A gray-headed

little man, of seventy, lived down in this one room, sunken from the

street. He had been married forty years, and if I remember aright,

he lost his wife about four years ago. Since that time, he had lived

in this cellar, all alone, washing and cooking for himself. But I

think the last would not trouble him much, for "they have no need for fine

cooks who have only one potato to their dinner." When a lad, he had

been apprenticed to a bobbin turner. Afterwards he picked up some

knowledge of engineering; and he had been "well off in his day." He

now got a few coppers occasionally from the poor folk about, by grinding

knives, and doing little tinkering jobs. Under the window he had a

rude bench, with a few rusty tools upon it, and in one corner there was a

low, miserable bedstead, without clothing upon it. There was one

cratchinly chair in the place, too; but hardly anything else. He had

no fire; he generally went into neighbours' houses to warm himself.

He was not short of such food as the Relief Committees bestow. There

was a piece of bread upon the bench, left from his morning meal; and the

old fellow chirruped about, and looked as blithe as if he was up to the

middle in clover. He showed us a little thing which he had done "for

a bit ov a prank." The number of his cellar was 8, and he had cut

out a large tin figure of 8, a foot long, and nailed it upon his door, for

the benefit of some of his friends that were getting bad in their

eyesight, and "couldn't read smo' print so low deawn as that."

"Well, John," said my companion, when we went in, "how are you getting

on?" "Oh, bravely," replied he, handing a piece of blue paper to the

inquirer, "bravely; look at that!" "Why, this is a summons," said my

companion. "Ay, bigad is't, too," answered the old man. "Never

had sich a thing i' my life afore! Think o' me gettin' a summons for

breakin' windows at seventy year owd. A bonny marlock, that, isn't

it? Why, th' whole street went afore th' magistrates to get mo off."

"Then you did get off, John?" "Get off! Sure, aw did. It

wur noan o' me. It wur a keaw jobber, at did it. . . . Aw'll tell yo

what, for two pins aw'd frame that summons, an' hang it eawt o' th'

window; but it would look so impudent."

|

|

|

|

|

|

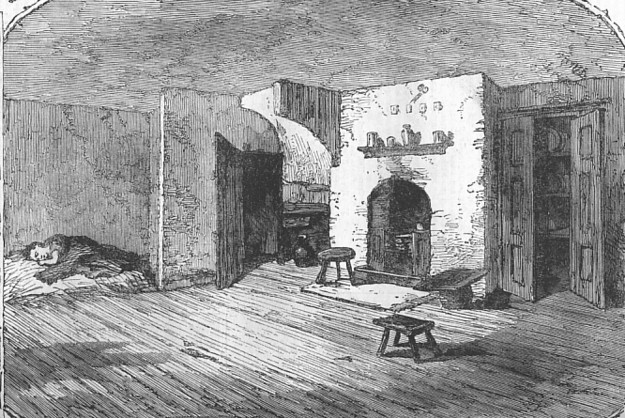

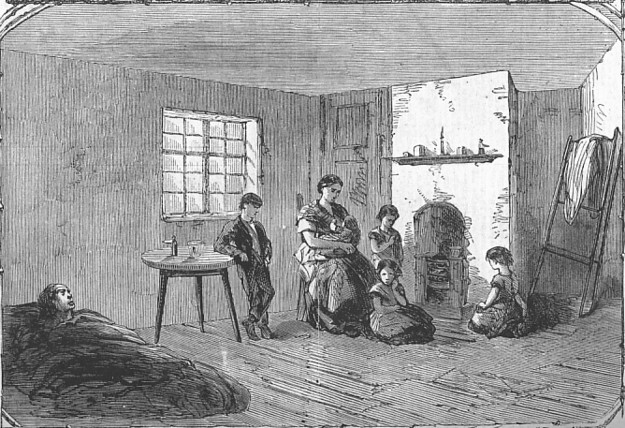

|

Cotton Operative's dwelling

― Illustrated London News.

Courtesy of the 'Cotton Town digitzation project'. |

Old John's wants were inquired into, and we left him fiddling among his

rusty tools.

We next went to a place called Hammond's Row ― thirteen

poor cottages, side by side. Twelve of the thirteen were inhabited

by people living, almost entirely, upon relief, either from the parish or

from the Relief Committee. There was only one house where no relief

was needed. As we passed by, the doors were nearly all open, and the

interiors all presented the same monotonous phase of destitution.

They looked as if they had been sacked by bum-bailiffs.

The topmost house

was the only place where I saw a fire. A family of eight lived there. They

were Irish people. The wife, a tall, cheerful woman, sat suckling her

child, and giving a helping hand now and then to her husband's work. He

was a little, pale fellow, with only one arm, and he had an impediment in

his speech. He had taken to making cheap boxes of thin, rough deal,

afterwards covered with paper. With the help of his wife he could make one

in a day, and he got ninepence profit out of it ― when the box was sold. He was working at one when we went in, and he twirled it proudly about

with his one arm, and stammered out a long explanation about the way it

had been made; and then he got upon the lid, and sprang about a little, to

let us see how much it would bear. As the brave little tattered man stood

there upon the box-lid, springing, and sputtering, and waving his one arm,

his wife looked up at him with a smile, as if she thought him "the

greatest wight on ground."

There was a little curly-headed child standing

by, quietly taking in all that was going on. I laid my hand upon her head;

and asked her what her name was. She popped her thumb into her mouth, and

looked shyly about from one to another, but never a word could I get her

to say. "That's Lizzy," said the woman; "she is a little visitor belongin'

to one o' the neighbours. They are badly off, and she often comes in. Sure, our childer is very fond of her, an' so she is of them. She is fine

company wid ourselves, but always very shy wid strangers. Come now, Lizzy,

darlin'; tell us your name, love, won't you, now?" But it was no use; we

couldn't get her to speak.

In the next cottage where we called, in this

row, there was a woman washing. Her mug was standing upon a stool in the

middle of the floor; and there was not any other thing in the place in the

shape of furniture or household utensil. The walls were bare of

everything, except a printed paper, bearing these words:

"The wages of sin is death. But the gift of God is eternal life, through

Jesus Christ our Lord."

We now went to another street, and visited the

cottage of a blind chair-maker, called John Singleton. He was a kind of

oracle among the poor folk of the neighbourhood. The old chair-maker was

sitting by the fire when we went in; and opposite to him sat "Old John,"

the hero of the broken windows in Nile Street. He had come up to have a

crack with his blind crony. The chair-maker was seventy years of age, and

he had benefited by the advantage of good fundamental instruction in his

youth. He was very communicative. He said he should have been educated for

the priesthood, at Stonyhurst College. "My clothes were made, an'

everything was ready for me to start to Stonyhurst. There was a stagecoach

load of us going; but I failed th' heart, an' wouldn't go ― an' I've

forethought ever sin'. Mr Newby said to my friends at the same time, he

said, 'You don't need to be frightened of him; he'll make the brightest

priest of all the lot ― an' I should, too. . . . I consider mysel' a young

man yet, i' everything, except it be somethin' at's uncuth to me." And

now, old John, the grinder, began to complain again of how badly he had

been used about the broken windows in Nile Street. But the old chair-maker

stopped him; and, turning up his blind eyes, he said, "John, don't you be

foolish. Bother no moor abeawt it. All things has but a time."

CHAPTER VIII.

A man cannot go wrong in Trinity Ward just now, if he wants

to see poor folk. He may find them there at any time, but now he

cannot help but meet them; and nobody can imagine how badly off they are,

unless he goes amongst them. They are biding the hard time out

wonderfully well, and they will do so to the end. They certainly

have not more than a common share of human frailty. There are those

who seem to think that when people are suddenly reduced to poverty, they

should become suddenly endowed with the rarest virtues; but it never was

so, and, perhaps, never will be so long as the world rolls.

In my rambles about this ward, I was astonished at the dismal

succession of destitute homes, and the number of struggling owners of

little shops, who were watching their stocks sink gradually down to

nothing, and looking despondingly at the cold approach of pauperism.

I was astonished at the strings of dwellings, side by side, stript, more

or less, of the commonest household utensils ― the poor little bare

houses, often crowded with lodgers, whose homes had been broken up

elsewhere; sometimes crowded, three or four families of decent working

people in a cottage of half-a-crown a-week rental; sleeping anywhere, on

benches or on straw, and afraid to doff their clothes at night time

because they had no other covering. Now and then the weekly visitor

comes to the door of a house where he has regularly called. He lifts

the latch, and finds the door locked. He looks in at the window.

The house is empty, and the people are gone ― the Lord knows where.

Who can tell what tales of sorrow will have their rise in the pressure of

a time like this ― tales that will never be written, and that no

statistics will reveal.

|

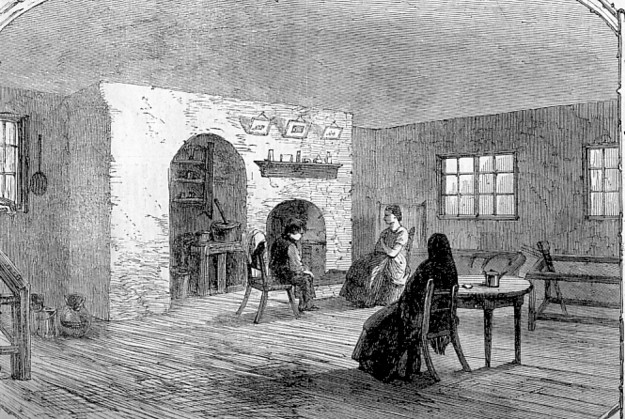

|

Workers at Fairfield Mills, Droylsden.

Courtesy Tameside Local Studies and Archives Centre. |

Trinity Ward swarms with factory operatives; and, after our

chat with blind John, the chair-maker, and his ancient crony the grinder

from Nile Street, we set off again to see something more of them.

Fitful showers came down through the day, and we had to shelter now and

then. In one cottage, where we stopped a few minutes, the old woman

told us that, in addition to their own family, they had three young women

living with them ― the orphan daughters of her husband's brother.

They had been out of work thirty-four weeks, and their uncle ― a very poor

man ― had been obliged to take them into his house, "till sich times as

they could afford to pay for lodgin's somewheer else." My companion

asked whether they were all out of work still. "Naw," replied the

old woman, "one on 'em has getten on to wortch a few days for t' sick

(that is, in the place of some sick person). Hoo's wortchin' i' th'

cardreawn at 'Th' Big-un.'" (This is the name they give to Messrs Swainson

and Birley's mill.)

The next place we called at was the house of an old joiner.

He was lying very ill upstairs. As we drew up to the door, my

companion said, "Now, this is a clean, respectable family. They have

struggled hard and suffered a great deal, before they would ask for

relief." When we went in, the wife was cleaning her well-nigh empty

house. "Eh," said she," I thought it wur th' clubman comin', an' I

wur just goin' to tell him that I had nothin' for him." The family

was seven in number ― man, wife, and five children. The husband, as

I have said, was lying ill. The wife told me that they had only 6s.

a-week coming in for the seven to live upon.

My companion was the weekly visitor who relieved them.

She told me that her husband was sixty-eight years old; she was not forty.

She said that her husband was not strong, and he had been going nearly

barefoot and "clemmed" all through last winter, and she was afraid he had

got his death of cold. They had not a bed left to lie upon.

"My husband," said she, "was a master joiner once, an' was doin' very

well. But you see how we are now."

There were two portraits ― oil paintings ― hanging against

the wall. "Whose portraits are these?" said I. "Well; that's

my master ― an' this is me," replied she. "He would have 'em taken

some time since. I couldn't think o' sellin' 'em; or else, yo see,

we've sold nearly everything we had. I did try to pawn 'em, too,

thinkin' we could get 'em back again when things came round; but, I can

assure yo, I couldn't find a broker anywhere that would tak' 'em in."

"Well, Missis," said my companion, "yo have one comfort; you are always

clean." "Eh, bless yo!" replied she, "I couldn't live among dirt!

My husban' tells me that I clean all the luck away; but aw'm sure there's

no luck i' filth; if there is, anybody may tak' it for me."

The rain had stopt again; and after my friend had made a note

respecting some additional relief for the family, we bade the woman good

day. We had not gone far before a little ragged lass looked up

admiringly at two pinks I had stuck in my buttonhole, and holding up her

hand, said, "Eh, gi' me a posy!"

My friend pointed to one of the cottages we passed, and said

that the last time he called there, he found the family all seated round a

large bowl of porridge, made of Indian meal. This meal is sold at a

penny a pound. He stopped at another cottage and said, "Here's a

house where I always find them reading when I call. I know the

people very well." He knocked and tried the latch, but there was

nobody in.

As we passed an open door, the pleasant smell of oatcake

baking came suddenly upon me. It woke up many memories of days gone

by. I saw through the window a stout, meal-dusted old woman, busy

with her wooden ladle and baking-shovel at a brisk oven. "Now, I

should like to look in there for a minute or two, if it can be done," said

I. "Well," replied my friend, "this woman is not on our books; she

gets her own living in the way you see. But come in; it will be all

right; I know her very well." I was glad of that, for I wanted to

have a chat with her, and to peep at the baking.

"Good morning, Missis," said he; "how are you?" "Why,

just in a middlin' way." "How long is this wet weather going to

last, think you?" "Nay, there ye hev me fast; ― but what brings ye

here this mornin'?" said the old woman, resting the end of her ladle on

the little counter; "I never trouble sic like chaps as ye." "No,

no," replied my friend; "we have not called about anything of that kind."

"What, then, pray ye?" "Well, my friend, here, is almost a stranger

in Preston; and as soon as ever he smelt the baking, he said he should

like to see it, so I took the liberty of bringing him in." "Oh, ay;

come in, an' welcome. Ye're just i' time, too; for I've bin sat at

t' back to sarra (serve) t' pigs."

"You're not a native of Lancashire, Missis," said

I. "Why, wheer then? come, now; let's be knowin', as ye're so

sharp." "Cumberland," said I. "Well, now; ye're reight, sewer

enough. But how did ye find it out, now?" "Why, you said that

you had been out to sarra t' pigs. A native of Lancashire would have

said 'serve' instead of 'sarra.'" "Well, that's varra queer; for

I've bin a lang time away from my awn country. But, whereivver do ye

belang to, as ye're so bowd wi' me?" said she, smiling, and turning over a

cake which was baking upon the oven. I told her that I was born a

few miles from Manchester. "Manchester! never, sewer;" said she,

resting her ladle again; "why, I lived ever so long i' Manchester when I

was young. I was cook at th' Swan i' Shudehill, aboon forty year

sin."

She said that, in those days, the Swan, in Shudehill,

was much frequented by the commercial men of Manchester. It was a

favourite dining house for them. Many of them even brought their own

beefsteak on a skewer; and paid a penny for the cooking of it. She

said she always liked Manchester very well; but she had not been there for

a good while. "But," said she, "ye'll hev plenty o' oatcake theer ―

sartin." "Not much, now," replied I; "it's getting out o' fashion."

I told her that we had to get it once a week from a man who came all the

way from Stretford into Manchester, with a large basketful upon his head,

crying "Woat cakes, two a penny!" "Two a penny!" said she; "why,

they'll not be near as big as these, belike." "Not quite," replied

I. "Not quite! naw; not hauf t' size, aw warnd! Why, th' poor

fellow desarves his brass iv he niver gev a farthin' for th' stuff to mak

'em on. What! I knaw what oatcake bakin' is."

Leaving the canny old Cumberland woman at her baking, we

called at a cottage in Everton Gardens. It was as clean as a

gentleman's parlour; but there was no furniture in sight except a table,

and, upon the table, a fine bush of fresh hawthorn blossom, stuck in a

pint jug full of water. Here, I heard again the common story ― they

had been several months out of work; their household goods had dribbled

away in ruinous sales, for something to live upon; and now, they had very

little left but the walls. The little woman said to me, "Bless yo,

there is at thinks we need'n nought, becose we keepen a daycent eawtside.

But, I know my own know abeawt that. Beside, one doesn't like to

fill folk's meawths, iv one is ill off."

It was now a little past noon, and we spent a few minutes

looking through the Catholic schoolhouse, in Trinity Ward ― a spacious

brick building. The scholars were away at dinner. My friend is

master of the school. His assistant offered to go with us to one or

two Irish families in a close wynd, hard by, called Wilkie's Court.

In every case I had the great advantage of being thus accompanied by

gentlemen who were friendly and familiar with the poor we visited.

This was a great facility to me.

Wilkie's Court is a little cul de sac, with about

half-a-dozen wretched cottages in it, fronted by a dead wall. The

inhabitants of the place are all Irish. They were nearly all kept

alive by relief from one source or other; but their poverty was not

relieved by that cleanliness which I had witnessed in so many equally poor

houses, making the best use of those simple means of comfort which are

invaluable, although they cost little or nothing.

In the first house we called at, a middle-aged woman was

pacing slowly about the unwholesome house with a child in her arms.

My friend inquired where the children were. "They are in the houses

about; all but the one poor boy." "And where is he?" said I.

"Well, he comes home now an' agin; he comes an' goes; sure, we don't know

how. . . . Ah, thin, sir," continued she, beginning to cry, "I'll tell ye

the rale truth, now. He was drawn away by some bad lads, an' he got

three months in the New Bailey; that's God's truth. . . . Ah, what'll I do

wid him," said she, bursting into tears afresh; "what'll I do wid him?

sure, he is my own!"

We did not stop long to intrude upon such trouble as this.

She called out as we came away to tell us that the poor crayter next door

was quite helpless.

The next house was, in some respects, more comfortable than

the last, though it was quite as poor in household goods. There was

one flimsy deal table, one little chair, and two half-penny pictures of

Catholic saints pinned against the wall. "Sure, I sold the other

table since you wor here before," said the woman to my friend; "I sold it

for two-an'-aightpence, an' bought this one for sixpence." At the

house of another Irish family, my friend inquired where all the chairs

were gone. "Oh," said a young woman, "the baillies did fetch uvverything away, barrin' the one sate, when we were livin' in Lancaster

Street." "Where do you all sit now, then?" "My mother sits

there," replied she, "an' we sit upon the flure." "I heard they were

goin' to sell these heawses," said one of the lads, "but, begorra,"

continued he, with a laugh, "I wouldn't wonder did they sell the ground

from under us next."

In the course of our visitation a thunder storm came on,

during which we took shelter with a poor widow woman, who had a plateful

of steeped peas for sale, in the window. She also dealt in rags and

bones in a small way, and so managed to get a living, as she said, "beawt

troublin' onybody for charity." She said it was a thing that folk

had to wait a good deal out in the cold for.

It was market-day, and there were many country people in

Preston. On my way back to the middle of the town, I called at an

old inn, in Friargate, where I listened with pleasure a few minutes to the

old-fashioned talk of three farmers from the Fylde country. Their

conversation was principally upon cow-drinks. One of them said there

was nothing in the world like "peppermint tay an' new butter" for cows

that had the belly-ache. "They'll be reet in a varra few minutes at

after yo gotten that into 'em," said he.

As evening came on the weather settled into one continuous

shower, and I left Preston in the heavy rain, weary, and thinking of what

I had seen during the day. Since then I have visited the town again,

and I shall say something about that visit hereafter.

CHAPTER IX.

The rain had been falling heavily through the night. It was

raw and gusty, and thick clouds were sailing wildly overhead, as I went to

the first train for Preston.

It was that time of morning when there is a lull in the

streets of Manchester, between six and eight. The "knocker-up" had

shouldered his long wand, and paddled home to bed again; and the little

stalls, at which the early workman stops for his half-penny cup of coffee,

were packing up. A cheerless morning, and the few people that were

about looked damp and low spirited.

I bought the day's paper, and tried to read it, as we flitted

by the glimpses of dirty garret-life, through the forest of chimneys,

gushing forth their thick morning fumes into the drizzly air, and over the

dingy web of Salford streets. We rolled on through Pendleton, where

the country is still trying to look green here and there, under increasing

difficulties; but it was not till we came to where the green vale of

Clifton opened out, that I became quite reconciled to the weather.

Before we were well out of sight of the ancient tower of Prestwich Church,

the day brightened a little. The shifting folds of gloomy cloud began to

glide asunder, and through the gauzy veils which lingered in the

interspaces, there came a dim radiance which lighted up the rain-drops

"lingering on the pointed thorns;" and the tall meadow grasses were

swaying to and fro with their loads of liquid pearls, in courtesies full

of exquisite grace, as we whirled along. I enjoyed the ride that raw

morning, although the sky was all gloom again long before we came in sight

of the Ribble.

I met my friend, in Preston, at half-past nine; and we

started at once for another ramble amongst the poor, in a different part

of Trinity Ward. We went first to a little court, behind Bell

Street. There is only one house in the court, and it is known as "Th'

Back Heawse." In this cottage the little house-things had escaped

the ruin which I had witnessed in so many other places. There were

two small tables, and three chairs; and there were a few pots and a pan or

two. Upon the cornice there were two pot spaniels, and two painted

stone apples; and, between them, there was a sailor waving a union jack,

and a little pudgy pot man, for holding tobacco. On the windowsill

there was a musk-plant; and, upon the table by the staircase, there was a

rude cage, containing three young throstles.

The place was tidy; and there was a kind-looking old couple

inside. The old man stood at the table in the middle of the floor,

washing the pots, and the old woman was wiping them, and putting them

away. A little lad sat by the fire, thwittling at a piece of stick.

The old man spoke very few words the whole time we were there, but he kept

smiling and going on with his washing. The old woman was very civil,

and rather shy at first; but we soon got into free talk together.

She told me that she had borne thirteen children. Seven of them were

dead; and the other six were all married, and all poor.

"I have one son," said she; "he's a sailmaker. He's th'

best off of any of 'em. But, Lord bless yo; he's not able to help

us. He gets very little, and he has to pay a woman to nurse his sick

wife. . . . This lad that's here, ― he's a little grandson o' mine; he's

one of my dowter's childer. He brings his meight with him every day,

an' sleeps with us. They han bod one bed, yo see. His father

hasn't had a stroke o' work sin Christmas. They're badly off.

As for us ― my husband has four days a week on th' moor, ― that's 4s., an'

we've 2s. a week to pay out o' that for rent. Yo may guess fro that,

heaw we are. He should ha' been workin' on the moor today, but

they've bin rain't off. We've no kind o' meight i' this house bod

three-ha'poth o' peas; an' we've no firin'. He's just brokken up an

owd cheer to heat th' watter wi'. (The old man smiled at this, as if

he thought it was a good joke.) He helps me to wesh, an' sich like;

an' yo' know, it's a good deal better than gooin' into bad company, isn't

it? (Here the old man gave her a quiet, approving look, like a good

little lad taking notice of his mother's advice.) Aw'm very glad of

a bit o' help," continued she, "for aw'm not so terrible mich use, mysel'.

Yo see; aw had a paralytic stroke seven year sin, an' we've not getten

ower it. For two year aw hadn't a smite o' use all deawn this side.

One arm an' one leg trail't quite helpless. Aw drunk for ever o'

stuff for it. At last aw gat somethin' ov a yarb doctor. He

said that he could cure me for a very trifle, an' he did me a deal o'

good, sure enough. He nobbut charged me hauve-a-creawn. . . .

"We never knowed what it was to want a meal's meight till

lately. We never had a penny off th' parish, nor never trouble't

anybody till neaw. Aw wish times would mend, please God! . . . We

once had a pig, an' was in a nice way o' gettin' a livin'. . . . When

things began o' gooin' worse an' worse with us, we went to live in a

cellar, at sixpence a week rent; and we made it very comfortable, too.

We didn't go there because we liked th' place; but we thought nobody would

know; an, we didn't care, so as we could put on till times mended, an'

keep aat o' debt. But th' inspectors turned us out, an' we had to

come here, an' pay 2s. a week. . . .

"Aw do not like to ask for charity, iv one could help

it. They were givin' clothin' up at th' church a while sin', an'

some o' th' neighbours wanted me to go an' ax for some singlets, ye see aw

cannot do without flannels, ― but aw couldn't put th' face on." Now,

the young throstles in the cage by the staircase began to chirp one after

another. "Yer yo at that! "said the old man, turning round to the

cage; "yer yo at that! Nobbut three week owd!" "Yes," replied

the old woman; "they belong to my grandson theer. He brought 'em in

one day ― neest an' all; an' poor nake't crayters they were.

He's a great lad for birds." "He's no worse nor me for that,"

answered the old man; "aw use't to be terrible fond o' brids when aw wur

yung."

After a little more talk, we bade the old couple good day,

and went to peep at the cellar where they had crept stealthily away, for

the sake of keeping their expenses close to their lessening income.

The place was empty, and the door was open. It was a damp and

cheerless little hole, down in the corner of a dirty court.

We went next into Pole Street, and tried the door of a

cottage where a widow woman lived with her children less than a week

before. They were gone, and the house was cleared out. "They

have had neither fire nor candle in that house for weeks past," said my

companion. We then turned up a narrow entry, which was so dark and

low overhead that my companion only told me just in time to "mind my hat!"

There are several such entries leading out of Pole Street to little courts

behind. Here we turned into a cold and nearly empty cottage, where a

middle-aged woman sat nursing a sick child. She looked worn and ill

herself, and she had sore eyes. She told me that the child was her

daughter's. Her daughter's husband had died of asthma in the

workhouse, about six weeks before. He had not "addled" a penny for

twelve months before he died. She said, "We hed a varra good heawse

i' Stanley Street once; but we hed to sell up an' creep hitherto.

This heawse is 2s. 3d. a week; an' we mun pay it, or go into th' street.

Aw nobbut owed him for one week, an' he said, 'Iv yo connot pay yo mun

turn eawt for thoose 'at will do.' Aw did think o' gooin' to th'

Board," continued she, "for a pair o' clogs. My een are bad; an' awm

ill all o'er, an' it's wi' nought but gooin' weet o' my feet. My

daughter's wortchin'. Hoo gets 5s. 6d. a week. We han to live

an' pay th' rent, too, eawt o' that." I guessed, from the little

paper pictures on the wall, that they were Catholics.

In another corner behind Pole Street, we called at a cottage

of two rooms, each about three yards square. A brother and sister

lived together here. They were each about fifty years of age.

They had three female lodgers, factory operatives, out of work. The

sister said that her brother had been round to the factories that morning,

"Thinking that as it wur a pastime, there would haply be somebody off; but

he couldn't yer o' nought." She said she got a trifle by charing,

but not much now; for folks were "beginnin' to do it for theirsels."

We now turned into Cunliffe Street, and called upon an Irish

family there. It was a family of seven ― an old tailor, and his wife

and children. They had "dismissed the relief," as he expressed it,

"because they got a bit o' work." The family was making a little

living by ripping up old clothes, and turning the cloth to make it up

afresh into lads' caps and other cheap things. The old man had had a

great deal of trouble with his family. "I have one girl," said he,

"who has bothered my mind a dale. She is under the influence o' bad

advice. I had her on my hands for many months; an', after that, the

furst week's wages she got, she up, an' cut stick, an' left me. I

have another daughter, now nigh nineteen years of age. The trouble I

have with her I am content with; because it can't be helped. The

poor crayter hasn't the use of all her faculties. I have taken no

end o' pains with her, but I can't get her to count twenty on her finger

ends wid a whole life's tachein'. Fortune has turned her dark side

to me this long time, now; and, bedad, iv it wasn't for contrivin', an'

workin' hard to boot, I wouldn't be able to keep above the flood. I

assure ye it goes agin me to trouble the gentlemen o' the Board; an' so

long as I am able, I will not. I was born in King's County; an' I

was once well off in the city of Waterford. I once had 400 pounds in

the bank. I seen the time I didn't drame of a cloudy day; but things take

quare turns in this world. How-an-ever, since it's no better, thank

God it's no worse. Sure, it's a long lane that has never a turn in

it."

CHAPTER X.

|

"There's nob'dy but the Lord an' me

That knows what I've to bide."

― Natterin Nan. |

The slipshod old tailor shuffled after us to the door, talking about the

signs of the times. His frame was bowed with age and labour, and his

shoulders drooped away. It was drawing near the time when the

grasshopper would be a burden to him. A hard life had silently

engraved its faithful records upon that furrowed face; but there was a

cheerful ring in his voice which told of a hopeful spirit within him

still. The old man's nostrils were dusty with snuff, and his poor

garments hung about his shrunken form in the careless ease which is common

to the tailor's shop board.

I could not help admiring the brave old wrinkled workman as

he stood in the doorway talking about his second-hand trade, whilst the

gusty wind fondled about in his thin gray hair. I took a friendly

pinch from his little wooden box at parting, and left him to go on

struggling with his troublesome family to "keep above the flood," by

translating old clothes into new.

We called at some other houses, where the features of life

were so much the same that it is not necessary to say more than that the

inhabitants were all workless, or nearly so, and all living upon the

charitable provision which is the only thin plank between so many people

and death, just now. In one house, where the furniture had been

sold, the poor souls had brought a great stone into the place, and this

was their only seat. In Cunliffe Street, we passed the cottage of a

boilermaker, whom I had heard of before. His family was four in

number. This was one of those cases of wholesome pride in which the

family had struggled with extreme penury, seeking for work in vain, but

never asking for charity, until their own poor neighbours were at last so

moved with pity for their condition, that they drew the attention of the

Relief Committee to it. The man accepted relief for one week, but

after that, he declined receiving it any longer, because he had met with a

promise of employment. But the promise failed him when the time

came. The employer, who had promised, was himself disappointed of

the expected work. After this; the boilermaker's family was

compelled to fall back upon the Relief Committee's allowance. He who

has never gone hungry about the world, with a strong love of independence

in his heart, seeking eagerly for work from day to day, and coming home

night after night to a foodless, fireless house, and a starving family,

disappointed and desponding, with the gloom of destitution deepening

around him, can never fully realise what the feelings of such a man may be

from anything that mere words can tell.

In Park Road, we called at the house of a hand-loom weaver.

I learnt, before we went in, that two families lived here, numbering

together eight persons; and, though it was well known to the committee

that they had suffered as severely as any on the relief list, yet their

sufferings had been increased by the anonymous slanders of some

ill-disposed neighbours. They were quiet, well-conducted working

people; and these slanders had grieved them very much. I found the

poor weaver's wife very sensitive on this subject. Man's inhumanity

to man may be found among the poor sometimes. It is not every one

who suffers that learns mercy from that suffering. As I have said

before, the husband was a calico weaver on the hand-loom. He had to

weave about seventy-three yards of a kind of check for 3s., and a full

week's work rarely brought him more than 5s. It seems astonishing

that a man should stick year after year to such labour as this. But

there is a strong adhesiveness, mingled with timidity, in some men, which

helps to keep them down.

In the front room of the cottage there was not a single

article of furniture left, so far as I can remember. The weaver's

wife was in the little kitchen, and, knowing the gentleman who was with

me, she invited us forward. She was a wan woman, with sunken eyes,

and she was not much under fifty years of age. Her scanty clothing

was whole and clean. She must have been a very good-looking woman

sometime, though she seemed to me as if long years of hard work and poor

diet had sapped the foundations of her constitution; and there was a

curious changeful blending of pallor and feverish flush upon that worn

face. But, even in the physical ruins of her countenance, a pleasing

expression lingered still. She was timid and quiet in her manner at

first, as if wondering what we had come for; but she asked me to sit down.

There was no seat for my friend, and he stood leaning against the wall,

trying to get her into easy conversation. The little kitchen looked

so cheerless and bare that dull morning that it reminded me again of a

passage in that rude, racy song of the Lancashire weaver, "Jone o'

Greenfeelt" ―

|

"Owd Bill o' Dan's sent us th' baillies one day,

For a shop-score aw owed him, at aw couldn't pay;

But, he were too lat, for owd Billy at th' Bent

Had sent th' tit an' cart, an' taen th' goods off for rent, ―

They laft nought but th' owd stoo;

It were seats for us two,

An' on it keawr't Margit an' me.

"Then, th' baillies looked reawnd 'em as sly as a meawse,

When they see'd at o'th goods had bin taen eawt o' th' heawse;

Says tone chap to tother, 'O's gone, ― thae may see,' ―

Says aw, 'Lads, ne'er fret, for yo're welcome to me!'

Then they made no moor do,

But nipt up wi' owd stoo,

An' we both letten thwack upo' th' flags.

"Then aw said to eawr Margit, while we're upo' the floor,

'We's never be lower i' this world, aw'm sure;

Iv ever things awtern they're likely to mend,

For aw think i' my heart that we're both at th' fur end;

For meight we han noan,

Nor no looms to weighve on,

An' egad, they're as good lost as fund.'" |

We had something to do to get the weaver's wife to talk to us

freely, and I believe the reason was, that, after the slanders they had

been subject to, she harboured a sensitive fear lest anything like doubt

should be cast upon her story. "Well, Mrs," said my friend, "let's

see; how many are you altogether in this house?" "We're two

families, yo know," replied she; "there's eight on us all altogether."

"Well," continued he, "and how much have you coming in, now?"

He had asked this question so oft before, and had so often

received the same answer, that the poor soul began to wonder what was the

meaning of it all. She looked at us silently, her wan face flushed,

and then, with tears rising in her eyes, she said, tremulously, "Well, iv

yo' cannot believe folk ― " My friend stopped her at once, and said,

"Nay, Mrs ―, you must not think that I

doubt your story. I know all about it; but my friend wanted me to

let you tell it your own way. We have come here to do you good, if

possible, and no harm. You don't need to fear that." "Oh,

well," said she, slowly wiping her moist forehead, and looking relieved,

"but yo know, aw was very much put about o'er th' ill-natur't talk as

somebody set eawt." "Take no notice of them," said my friend; "take

no notice. I meet with such things every day." "Well,"

continued she, "yo know heaw we're situated. We were nine months an'

hesn't a stroke o' wark. Eawr wenches are gettin' a day for t' sick,

neaw and then, but that's all. There's a brother o' mine lives with

us, ― he'd a been clemmed into th' grave but for th' relief; an' aw've

been many a time an' hesn't put a bit i' my meawth fro mornin' to mornin'

again. We've bin married twenty-four year; an' aw don't think at him

an' me together has spent a shillin' i' drink all that time. Why, to

tell yo truth, we never had nought to stir on. My husband does bod

get varra little upo th' hand-loom i' th' best o' times ― 5s. a week or

so. He weighves a sort o' check ― seventy-three yards for 3s."

The back door opened into a little damp yard, hemmed in by

brick walls. Over in the next yard we could see a man bustling

about, and singing in a loud voice, "Hard times come again no more."

"Yon fellow doesn't care much about th' hard times, I think," said I.

"Eh, naw," replied she. "He'll live where mony a one would dee, will

yon. He has that little shop, next dur; an' he keeps sellin' a bit

o' toffy, an' then singin' a bit, an' then sellin' a bit moor toffy, ― an'

he's as happy as a pig amung slutch."

Leaving the weaver's cottage, the rain came on, and we sat a

few minutes with a young shoemaker, who was busy at his bench, doing a

cobbling job. His wife was lying ill upstairs. He had been so

short of work for some time past that he had been compelled to apply for

relief. He complained that the cheap gutta percha shoes were hurting

his trade. He said a pair of men's gutta percha shoes could be

bought for 5s. 6d., whilst it would cost him 7s. 6d. for the materials

alone to make a pair of men's shoes.

When the rain was over, we left his house, and as we went

along I saw in a cottage window a printed paper containing these words,

"Bitter beer. This beer is made of herbs and roots of the native

country." I know that there are many poor people yet in Lancashire

who use decoctions of herbs instead of tea ― mint and balm are the

favourite herbs for this purpose; but I could not imagine what this herb

beer could be, at a halfpenny a bottle, unless it was made of nettles.

At the cottage door there was about four-pennyworth of mauled garden stuff

upon an old tray. There was nobody inside but a little ragged lass, who

could not tell us what the beer was made of. She had only one

drinking glass in the place, and that had a snip out of the rim. The

beer was exceedingly bitter. We drank as we could, and then went

into Pump Street, to the house of a "core-maker," a kind of labourer for

moulders. The core-maker's wife was in. They had four

children. The whole six had lived for thirteen weeks on 3s. 6d. a week.

When work first began to fall off, the husband told the visitors who came

to inquire into their condition, that he had a little money saved up, and

he could manage a while. The family lived upon their savings as long

as they lasted, and then were compelled to apply for relief, or "clem."

It was not quite noon when we left this house, and my friend

proposed that before we went farther we should call upon Mrs G

―, an interesting old woman, in Cunliffe

Street. We turned back to the place, and there we found

|

"In lowly shed, and mean attire,

A matron old, whom we schoolmistress name,

Who boasts unruly brats with birch to tame." |

In a small room fronting the street, the mild old woman sat,

with her bed in one corner, and her simple vassals ranged upon the forms

around. Here, "with quaint arts," she swayed the giddy crowd of

little imprisoned elves, whilst they fretted away their irksome school

time, and unconsciously played their innocent prelude to the serious drama

of life. As we approach the open door ―

|

"The noises intermix'd, which thence resound,

Do learning's little tenement betray;

Where sits the dame disguised in look profound,

And eyes her fairy throng, and turns her wheel around." |

The venerable little woman had lived in this house fourteen

years. She was seventy-three years of age, and a native of Limerick.

She was educated at St Ann's School, in Dublin, and she had lived fourteen

years in the service of a lady in that city. The old dame made an

effort to raise her feeble form when we entered, and she received us as

courteously as the finest lady in the land could have done. She told

us that she charged only a penny a-week for her teaching; but, said she,

"some of them can't pay it." "There's a poor child," continued she,

"his father has been out of work eleven months, and they are starving but

for the relief. Still, I do get a little, and I like to have the

children about me. Oh, my case is not the worst, I know. I