|

[Previous

Page]

AMONG THE PRESTON

OPERATIVES (cont.)

CHAPTER XI.

|

|

|

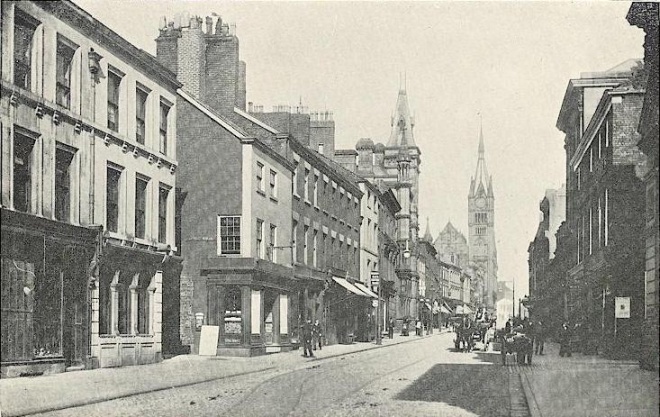

India Mill, Darwin ― courtesy Cotton Town

digitization project. |

We talked with the old schoolmistress in Cunliffe Street till it was "high

twelve" at noon, and then the kind jailer of learning's little

prison-house let all her fretful captives go. The clamorous elves

rushed through the doorway into the street, like a stream too big for its

vent, rejoicing in their new-found freedom and the open face of day.

The buzz of the little teaching mill was hushed once more, and the old

dame laid her knitting down, and quietly wiped her weak and weary eyes.

The daughters of music were brought low with her, but, in the last thin

treble of second childhood, she trembled forth mild complaints of her

neighbours' troubles, but very little of her own.

We left her to enjoy her frugal meal and her noontide

reprieve in peace, and came back to the middle of the town. On our

way I noticed again some features of street life which are more common in

manufacturing towns just now than when times are good. Now and then

one meets with a man in the dress of a factory worker selling newspapers,

or religious tracts, or back numbers of the penny periodicals, which do

not cost much. It is easy to see, from their shy and awkward manner,

that they are new to the trade, and do not like it. They are far

less dexterous, and much more easily "said," than the brisk young salesmen

who hawk newspapers in the streets of Manchester. I know that many

of these are unemployed operatives trying to make an honest penny in this

manner till better days return. Now and then, too, a grown-up girl

trails along the street, "with wandering steps and slow," ragged, and

soiled, and starved, and looking as if she had travelled far in the rainy

weather, houseless and forlorn. I know that such sights may be seen

at any time, but not near so often as just now; and I cannot help thinking

that many of these are poor sheep which have strayed away from the broken

folds of labour. Sometimes it is an older woman that goes by, with a

child at the breast, and one or two holding by the skirt of her tattered

gown, and perhaps one or two more limping after, as she crawls along the

pavement, gazing languidly from side to side among the heedless crowd, as

if giving her last look round the world for help, without knowing where to

get it, and without heart to ask for it. It is easy to give

wholesale reasons why nobody needs to be in such a condition as this; but

it is not improbable that there are some poor souls who, from no fault of

their own, drop through the great sieve of charity into utter destitution.

"They are well kept that God keeps." May the continual dew of

Heaven's blessing gladden the hearts of those who deal kindly with them!

After dinner I fell into company with some gentlemen who were

talking about the coming guild ― that ancient local festival, which is so

dear to the people of Preston, that they are not likely to allow it to go

by wholly unhonoured, however severe the times may be. Amongst them

was a gray-haired friend of mine, who is a genuine humorist. He told

us many quaint anecdotes. One of them was of a man who went to

inquire the price of graves in a certain cemetery. The sexton told

him that they were 1 pound on this side, and 2 pounds on the other side of

the knoll. "How is it that they are 2 pounds on the other side?"

inquired the man. "Well, becose there's a better view there,"

replied the sexton.

There were three or four millowners in the company, and, when

the conversation turned upon the state of trade, one of them said, "I

admit that there is a great deal of distress, but we are not so badly off

yet as to drive the operatives to work for reasonable wages. For

instance, I had a labourer working for me at 10s. a-week; he threw up my

employ, and went to work upon the moor for 1s. a-day. How do you

account for that? And then, again, I had another man employed as a

watchman and roller coverer, at 18s. a-week. I found that I couldn't

afford to keep him on at 18s., so I offered him 15s. a-week; but he left

it, and went to work on the moor at 1s. a-day; and, just now, I want a man

to take his place, and cannot get one." Another said, "I am only

giving low wages to my workpeople, but they get more with me than they can

make on the moor, and yet I cannot keep them." I heard some other

things of the same kind, for which there might be special reasons; but

these gentlemen admitted the general prevalence of severe distress, and

the likelihood of its becoming much worse.

|

STANZAS TO MY STARVING KIN

IN THE NORTH.

Sad are the sounds that are

breaking forth

From the women and men of the brave old North!

Sad are the sights for human eyes,

In fireless homes, 'neath wintry skies;

Where wrinkles gather on childhood's skin,

And youth's "clemm'd" cheek is pallid and thin;

Where the good, the honest ― unclothed, unfed,

Child, mother, and father, are craving for bread!

But faint not, fear not ― still have trust;

Your voices are heard, and your claims are just.

England to England's self is true,

And "God and the People" will help you through.

Brothers and sisters! full well ye have stood,

While the gripe of gaunt Famine has curdled your

blood!

No murmur, no threat on your lips have place,

Though ye look on the Hunger-fiend face to face;

But haggard and worn ye silently bear,

Dragging your death-chains with patience and

prayer;

With your hearts as loyal, your deeds as right,

As when Plenty and Sleep blest your day and your

night,

Brothers and sisters! oh! do not believe

It is Charity's GOLD ALONE

ye receive.

Ah, no! It is Sympathy, Feeling, and Hope,

That pull out in the Life-boat to fling ye a rope.

Fondly I've lauded your wealth-winning hands,

Planting Commerce and Fame throughout measure-

less lands;

And my patriot-love, and my patriot-song,

To the children of Labour will ever belong.

Women and men of this brave old soil!

I weep that starvation should guerdon your toil;

But I glory to see ye ― proudly mute ―

Showing souls like the hero, not fangs like the

brute.

Oh! keep courage within; be the Britons ye are;

HE, who driveth the

storm hath HIS hand on the star!

England to England's sons shall be true,

And "God and the People" will carry ye through!

ELIZA

COOK.. |

At two o'clock I sallied forth again, under convoy of another

member of the Relief Committee, into the neighbourhood of Messrs Horrocks,

Miller, and Co.'s works. Their mill is known as "Th' Yard Factory."

Hereabouts the people generally are not so much reduced as in some parts

of the town, because they have had more employment, until lately, than has

been common elsewhere. But our business lay with those distressed

families who were in receipt of relief, and, even here, they were very

easy to find.

The first house we called at was inhabited by a family of

five ― man and wife and three children. The man was working on the

moor at one shilling a-day. The wife was unwell, but she was moving

about the house. They had buried one girl three weeks before; and

one of the three remaining children lay ill of the measles. They had

suffered a great deal from sickness. The wife said, "My husband is a

peawer-loom weighver. He had to come whoam ill fro' his wark; an'

then they shopped his looms, (gave his work to somebody else,) an' he

couldn't get 'em back again. He'll get 'em back as soon as he con,

yo may depend; for we don't want to bother folk for no mak o' relief no

lunger than we can help." In addition to the husband's pay upon the

moor, they were receiving 2s. a week from the Committee, making altogether

8s. a week for the five, with 2s. 6d. to pay out of it for rent. She

said, "We would rayther ha' soup than coffee, becose there's moor heytin'

in it."

My friend looked in at the door of a cottage in Barton

Street. There was a sickly-looking woman inside. "Well, missis,"

said my friend, jocularly, "how are you? because, if you're ill, I've

brought a doctor here." "Eh," replied she, "aw could be ill in a

minute, if aw could afford, but these times winnot ston doctors' bills.

Besides, aw never were partial to doctors' physic; it's kitchen physic at

aw want. Han yo ony o' that mak' wi' yo?" she said, "My husban'

were th' o'erlooker o' th'weighvers at 'Owd Tom's.' They stopt to

fettle th' engine a while back, an' they'n never started sin'. But

aw guess they wi'n do some day."

We had not many yards to go to the next place, which was a

poor cottage in Fletcher's Row, where a family of eight persons resided.

There was very little furniture in the place, but I noticed a small shelf

of books in a corner by the window. A feeble woman, upwards of

seventy years old, sat upon a stool tending the cradle of a sleeping

infant. This infant was the youngest of five children, the oldest of

the five was seven years of age. The mother of the three-weeks-old

infant had just gone out to the mill to claim her work from the person who

had been filling her place during her confinement. The old woman

said that the husband was "a grinder in a card-room when they geet wed,

an' he addled about 8s. a week; but, after they geet wed, his wife larn't

him to weighve upo' th' peawer-looms." She said that she was no

relation to them, but she nursed, and looked after the house for them.

"They connot afford to pay mo nought," continued she, "but aw fare as they

fare'n, an' they dunnot want to part wi' me. Aw'm not good to mich,

but aw can manage what they wanten, yo see'n. Aw never trouble't

noather teawn nor country i' my life, an' aw hope aw never shall for the

bit o' time aw have to do on." She said that the Board of Guardians

had allowed the family 10s. a week for the two first weeks of the wife's

confinement, but now their income amounted to a little less than one

shilling a head per week.

|

|

|

India Mill, Darwin.

Courtesy Cotton Town

digitization project. |

Leaving this house, we turned round the corner into St Mary's Street

North. Here we found a clean-looking young working man standing shivering

by a cottage door, with his hands in his pockets. He was dressed in

well-mended fustian, and he had a cloth cap on his head. His face had a

healthy hunger-nipt look. "Hollo," said my friend, "I thought you was

working on the moor." "Ay," replied the young man, "Aw have bin, but we'n

bin rain't off this afternoon." "Is there nobody in?" said my friend. "Naw,

my wife's gone eawt; hoo'll not be mony minutes. Hoo's here neaw." A clean

little pale woman came up, with a child in her arms, and we went in. They

had not much furniture in the small kitchen, which was the only place we

saw, but everything was sweet and orderly. Their income was, as usual in

relief cases, about one shilling a head per week. "You had some lodgers,"

said my friend. "Ay," said she, "but they're gone." "How's that?" "We had a

few words. Their little lad was makin' a great noise i' the passage theer,

an' aw were very ill o' my yed, an' aw towd him to go an' play him at

tother side o' th' street, ― so, they took it amiss, an' went to lodge wi'

some folk i' Ribbleton Lone."

We called at another house in this street. A family of six lived there. The only furniture I saw in the place was two chairs, a table, a large

stool, a cheap clock, and a few pots. The man and his wife were in. She

was washing. The man was a stiff-built, shock-headed little fellow, with a

squint in his eye that seemed to enrich the good-humoured expression of

his countenance. Sitting smiling by the window, he looked as if he had

lots of fun in him, if he only had a fair chance of letting it off. He

told us that he was a "tackler" by trade. A tackler is one who fettles

looms when they get out of order. "Couldn't you get on at Horrocks's?"

said my friend. "Naw," replied he; "they'n not ha' men-weighvers theer." The wife said, "We're a deal better off than some. He has six days a week upo th' moor, an' we'n 3s. a week fro th' Relief Committee. We'n 2s. 6d. a

week to pay eawt on it for rent; but then, we'n a lad that gets 4d. a day

neaw an' then for puttin' bobbins on; an' every little makes a mickle, yo

known." "How is it that your clock's stopt?" said I. "Nay," said the

little fellow; "aw don't know. Want o' cotton, happen, ― same as

everything else is stopt for."

Leaving this house we met with another

member of the Relief Committee, who was overlooker of a mill a little way

off. I parted here with the gentleman who had accompanied me hitherto, and

the overlooker went on with me.

In Newton Street he stopped, and said, "Let's look in here." We went up

two steps, and met a young woman coming out at the cottage door. "How's

Ruth?" said my friend. "Well, hoo is here. Hoo's busy bakin' for Betty." We went in. "You're not bakin' for yourselves, then?" said he. "Eh, naw,"

replied the young woman, "it's mony a year sin' we had a bakin' o' fleawr,

isn't it, Ruth?" The old woman who was baking turned round and said, "Ay;

an' it'll be mony another afore we han one aw deawt."

There were three

dirty-looking hens picking and croodling about the cottage floor. "How is

it you don't sell these, or else eat 'em?" said he. "Eh, dear," replied

the old woman, "dun yo want mo kilt? He's had thoose hens mony a year; an'

they rooten abeawt th' heawse just th' same as greadley Christians. He did gi' consent for one on 'em to be kilt yesterday; but aw'll be hanged iv th'

owd cracky didn't cry like a chylt when he see'd it beawt yed. He'd as

soon part wi' one o'th childer as one o'th hens. He says they're so mich

like owd friends, neaw. He's as quare as Dick's hat-bant 'at went nine

times reawnd an' wouldn't tee. . . . We thought we'd getten a shop for yon

lad o' mine t'other day. We yerd ov a chap at Lytham at wanted a lad to

tak care o' six jackasses an' a pony. Th' pony were to tak th' quality to

Blackpool, and such like. So we fettled th' lad's bits o' clooas up and

made him ever so daycent, and set him off to try to get on wi' th' chap at

Lytham. Well, th' lad were i' good heart abeawt it; an' when he geet theer

th' chap towd him at he thought he wur very likely for th' job, so that

made it better, ― an' th' lad begun o' wearin' his bit o' brass o' summat

to eat, an' sich like, thinkin' he're sure o' th' shop. Well, they kept

him there, dallyin', aw tell yo, an' never tellin' him a greadley tale,

fro Sunday till Monday o' th' neet, an' then, ― lo an' behold, ― th' mon

towd him that he'd hire't another; and th' lad had to come trailin' whoam

again, quite deawn i'th' meawth. Eh, aw wur some mad! Iv aw'd been at th'

back o' that chap, aw could ha' punce't him, see yo!" "Well," said my

friend, "there's no work yet, Ruth, is there?" "Wark! naw; nor never will

be no moor, aw believe."

"Hello, Ruth!" said the young woman, pointing

through the window, "dun yo know who yon is?" "Know? ay," replied the old

woman; "He's getten aboon porritch neaw, has yon. He walks by me i'th

street, as peart as a pynot, an' never cheeps. But, he's no 'casion. Aw know'd him when his yure stickt out at top ov his hat; and his shurt would

ha' hanged eawt beheend, too, ― like a Wigan lantron, ― iv he'd had a

shurt."

CHAPTER XII.

|

"Oh, reason not the deed; our basest beggars

Are in the poorest things superfluous:

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man's life is cheap as beast's."

― King Lear. |

A short fit of rain came on whilst we were in the cottage in

Newton Street, so we sat a little while with Ruth, listening to her quaint

tattle about the old man and his feathered pets; about the children, the

hard times, and her own personal ailments; ― for, though I could not help

thinking her a very good-hearted, humorous old woman, bravely disposed to

fight it out with the troubles of her humble lot, yet it was clear that

she was inclined to ease her harassed mind now and then by a little

wholesome grumbling; and I dare say that sometimes she might lose her

balance so far as to think, like "Natterin' Nan," "No livin' soul atop o't

earth's bin tried as I've bin tried: there's nob'dy but the Lord an' me

that knows what I've to bide."

Old age and infirmity, too, had found Ruth out, in her

penurious obscurity; and she was disposed to complain a little, like Nan,

sometimes, of "the ills that flesh is heir to:" ―

"Fro' t' wind i't stomach, rheumatism,

Tengin pains i't gooms,

An' coughs, an' cowds, an' t' spine o't back,

I suffer martyrdom.

"Yet nob'dy pities mo, or thinks

I'm ailin' owt at all;

T' poor slave mun tug an' tew wi't wark,

Wolivver shoo can crawl." |

Old Ruth was far from being as nattle and querulous as the

famous ill-natured grumbler so racily pictured by Benjamin Preston, of

Bradford; but, like most of the dwellers upon earth, she was a little bit

touched with the same complaint.

When the rain was over, we came away. I cannot say that

the weather ever "cleared up" that day; for, at the end of every shower,

the dark, slow-moving clouds always seemed to be mustering for another

downfall. We came away, and left the "cant" old body "busy bakin'

for Betty," and "shooing" the hens away from her feet, and she shuffled

about the house.

|

THE SPINNER'S HOME. |

|

I can easily fling

Common cares to wind,

For every heart hath its grief,

And merits the sting,

Every soul having sinn'd,

But mine may not hope for relief.

I am loth to complain,

Though I might have had cause,

For hunger is hard to endure;

Yet I will not arraign

Either Heaven or the laws

Of my country because I am poor.

I have battled with Want,

For a terrible term,

And been silent, till silence seemed crime;

Yet I mean not to rant,

But will yield you a germ

Of plain truth in an unpolished rhyme.

My health—that is good;

My family—few;

Accustomed to labour withal,

'Tis a marvel we should,

Yet alas! it is true,

Either starve or be stinted—but call

At the cabin I live in

And see for yourselves;

The walls and the windows are there,

But the fire has ceased giving

Its light, and the shelves

And the table are foodless and bare.

These walls once were hung

With the triumphs of Art,

This pantry with plenty was stored,

And Happiness flung

Her rich light on the heart

Of the dear ones who sat at this board.

Those dear ones are dead—

Though it cost me a tear

To tell how they drew their last breath—

Be it so!—want of bread

Brought on fever—severe!

And fever and famine brought death.

And now my lone heart,

Like a plummet of lead

That is dropt in the sea's sullen wave,

Droopeth far, far apart

From its owner; its bed

Is down deep in our little ones' grave.

The loud-prattling tongue,

The sweet simple look,

Little feet patt'ring, over the floor

To the past must belong,

And the heart that must brook

Their deep loss is indeed rendered poor!

Long years may roll on,

Good times may return,

And life seem as sweet as of yore;

But our loved ones are gone,

And their beauties will burn

In our desolate dwelling no more!

WILLIAM

BILLINGTON

1863. |

A few yards lower in Newton Street, we turned up a low, dark

entry, which led to a gloomy little court behind. This was one of

those unhealthy, pent-up cloisters, where misery stagnates and broods

among the "foul congregation of pestilential vapours" which haunt the

backdoor life of the poorest parts of great towns. Here, those

viewless ministers of health ― the fresh winds of heaven ― had no free

play; and poor human nature inhaled destruction from the poisonous

effluvia that festered there. And, in such nooks as this, there may

be found many decent working people, who have been accustomed to live a

cleanly life in their humble way in healthy quarters, now reduced to

extreme penury, pinching, and pining, and nursing the flickering hope of

better days, which may enable them to flee from the foul harbour which

strong necessity has driven them to.

The dark aspect of the day filled the court with a tomb-like

gloom. If I remember aright, there were only three or four cottages

in it. We called at two of them. Before we entered the first,

my friend said, "A young couple lives here. They are very decent

people. They have not been here long; and they have gone through a

great deal before they came here." There were two or three pot

ornaments on the cornice; but there was no furniture in the place, save

one chair, which was occupied by a pale young woman, nursing her child.

Her thin, intelligent face looked very sad. Her clothing, though

poor, was remarkably clean; and, as she sat there, in the gloomy, fireless

house, she said very little, and what she said she said very quietly, as

if she had hardly strength to complain, and was even half-ashamed to do

so. She told us, however, that her husband had been out of work six

months. "He didn't know what to turn to after we sowd th' things,"

said she; "but he's takken to cheer-bottomin', for he doesn't want to lie

upo' folk for relief, if he can help it. He doesn't get much above a

cheer, or happen two in a week, one week wi' another, an' even then he

doesn't olez get paid, for folks ha' not brass. It runs very hard

with us, an' I'm nobbut sickly." The poor soul did not need to say

much; her own person, which evinced such a touching struggle to keep up a

decent appearance to the last, and everything about her, as she sat there

in the gloomy place, trying to keep the child warm upon her cold breast,

told eloquently what her tongue faltered at and failed to express.

The next place we called at in this court was a cottage kept

by a withered old woman, with one foot in the grave. We found her in

the house, sallow, and shrivelled, and panting for breath. She had

three young women, out of work, lodging with her; and, in addition to

these, a widow with her two children lived there. One of these

children, a girl, was earning 2s. 6d. a week for working short time at a

mill; the other, a lad, was earning 3s. a week. The rest were all

unemployed, and had been so for several months past. This 5s. 6d. a

week was all the seven people had to live upon, with the exception of a

trifle the sickly old woman received from the Board of Guardians.

As we left the court, two young fellows were lounging at the

entry end, as if waiting for us. One of them stepped up to my

friend, and whispered something plaintively, pointing to his feet. I

did not catch the reply; but my friend made a note, and we went on.

Before we had gone many yards down the street a storm of rain and thunder

came on, and we hurried into the house of an old Irishwoman close by.

My friend knew the old woman. She was on his list of

relief cases. "Will you let us shelter a few minutes, Mrs ― ?" said

he. "I will, an' thank ye," replied she. "Come in an' sit

down. Sure, it's not fit to turn out a dog. Faith, that's a

great storm. Oh, see the rain! Thank God it's not him that

made the house that made the pot! Dear, dear; did ye see the awful

flash that time? I don't like to be by myself, I am so terrified wi'

the thunder. There has been a great dale o' wet this long time."

"There, has," replied my friend; "but how have ye been getting on since I

called before?" "Well," said the old woman, sitting down, "things is

quare with us as ever they can be, an' that you know very well."

There was a young woman reared against the table by the

window. My friend turned towards her, and said, "Well, and how does

the Indian meal agree with you?" The young woman blushed, and

smiled, but said nothing; but the old woman turned sharply round and

replied, "Well, now, it is better nor starvation; it is chape, an' it

fills up ― an' that's all." "Is your son working?" inquired my

friend. "Troth, he is," replied she. "He does be gettin' a day

now an' again at the breek-croft in Ribbleton Lone. Faith, it is

time he did somethin', too, for he was nine months out o' work entirely.

I am got greatly into debt, an' I don't think I'll ever be able to get

over it any more. I don't know how does poor folk be able to spind

money on drink such times as thim; bedad, I cannot do it. It is hard

enough to get mate of any kind to keep the bare life in a body. Oh,

see now; but for the relief, the half o' the country would die out."

"You're a native of Ireland, missis," said I. "Troth, I am," replied

she; "an' had a good farm o' greawnd in it too, one time. Ah! many's

the dark day I went through between that an' this. Before thim bad

times came on, long ago, people were well off in ould Ireland. I

seen them wid as many as tin cows standin' at the door at one time. . . .

Ah, then! but the Irish people is greatly scattered now! . . . But, for

the matter of that, folk are as badly off here as anywhere in the world, I

think. I dunno know how does poor folk be able to spind money for

dhrink. I am a widow this seventeen year now, an' the divle a man or

woman uvver seen me goin' to a public-house. I seen women goin' a

drinkin' widout a shift to their backs. I dunno how the divvle they

done it. Begorra, I think, if I drunk a glass of ale just now, my

two legs would fail from under me immadiately ― I am that wake." The old

woman was a little too censorious, I think.

There is no doubt that even people who are starving do drink

a little sometimes. The wonder would be if they did not, in some

degree, share the follies of the rest of the world. Besides, it is a

well-known fact, that those who are in employ, are apt, from a feeling of

misdirected kindness, to treat those who are out of work to a glass of ale

or two, now and then; and it is very natural, too, that those who have

been but ill-fed for a long time are not able to stand it well.

After leaving the old Irishwoman's house, we called upon a

man who had got his living by the sale of newspapers. There was

nothing specially worthy of remark in this case, except that he complained

of his trade having fallen away a good deal. "I used to sell three

papers where I now sell one," said he. This may not arise from there

being fewer papers sold, but from there being more people selling them

than when times were good.

I came back to Manchester in the evening. I have

visited Preston again since then, and have spent some time upon Preston

Moor, where there are nearly fifteen hundred men, principally factory

operatives, at work. Of this I shall have something to say in my

next paper.

CHAPTER XIII.

|

"The rose of Lancaster for lack of nurture pales."

― Blackburn Bard. |

It was early on a fine morning in July when I next set off to

see Preston again; the long-continued rains seemed to be ended, and the

unclouded sun flooded all the landscape with splendour. All nature

rejoiced in the change, and the heart of man was glad. In Clifton

Vale, the white-sleeved mowers were at work among the rich grass, and the

scent of new hay came sweetly through our carriage windows. In the

leafy cloughs and hedges, the small birds were wild with joy, and every

garden sent forth a goodly smell. Along its romantic vale the

glittering Irwell meandered, here, through nooks, "o'erhung wi' wildwoods,

thickening green;" and there, among lush unshaded pastures; gathering on

its way many a mild whispering brook, whose sunlit waters laced the green

land with freakish lines of trembling gold. To me this ride is

always interesting, so many points of historic interest line the way; but

it was doubly delightful on that glorious July morning. And I never

saw Fishergate, in Preston, look better than it did then.

|

|

Fishergate, Preston

― courtesy 'Spinning the Web'. |

On my arrival there I called upon the Secretary of the

Trinity Ward Relief Committee. In a quiet bye-street, where there

are four pleasant cottages, with little gardens in front of them, I found

him in his studious nook, among books, relief tickets, and correspondence.

We had a few minutes' talk about the increasing distress of the town; and

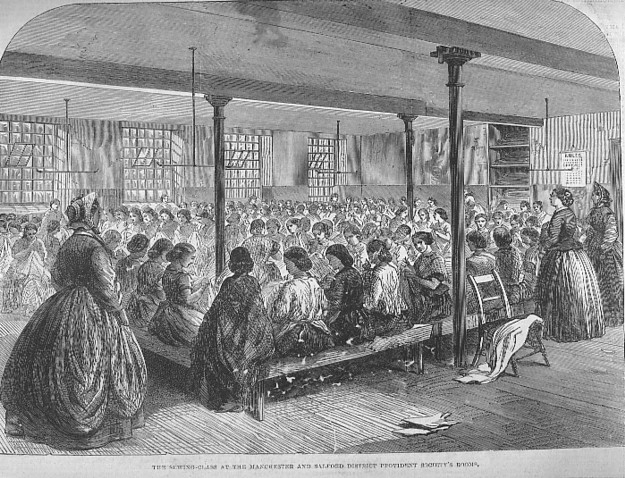

he gave me a short account of the workroom which has been opened in

Knowsley Street, for the employment of female factory operatives out of

work.

This workroom is managed by a committee of ladies, some of

whom are in attendance every day. The young women are employed upon

plain sewing. They have two days' work a week, at one shilling a

day, and the Relief Committee adds sixpence to this 2s. in each case.

Most of them are merely learning to sew. Many of them prove to be

wholly untrained to this simple domestic accomplishment. The work is

not remunerative, nor is it expected to be so; but the benefit which may

grow out of the teaching which these young women get here ― and the evil

their employment here may prevent, cannot be calculated. I find that

such workrooms are established in some of the other towns now suffering

from the depression of trade. Some of these I intend to visit

hereafter.

|

|

|

The sewing-class at the Manchester and Salford

District Provident Society's rooms.

Illustrated London News, November 29, 1862. |

|

SEWIN' CLASS SONG.

|

|

COME,

lasses, let's cheer up, an' sing, it's no use lookin' sad,

We'll mak' eawr sewin' schoo' to ring, an' stitch away loike mad;

We'll try an' mak' th' best job we con o' owt we han to do,

We read an' write, an' spell an' kest, while here at th' sewin'

schoo'.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing,

it's no use lookin' sad,

We'll mak' eawr sewin' schoo' to ring, an' stitch away loike mad.

Eawr Queen, th' Lord Mayor o' London, too, they send us lots o'

brass,

An' neaw, at welly every schoo', we'n got a sewin' class;

We'n superintendents, cutters eawt, an' visitors an' o;

We'n parsons, cotton mesturs, too, come in to watch us sew.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

Sin th' war begun, an' th' factories stopped, we're badly off, it's

true,

But still we needn't grumble, for we'n noan so mich to do;

We're only here fro' nine to four, an' han an heawer for noon,

We noather stop so very late nor start so very soon.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

It's noice au' easy sittin' here, there's no mistake i' that,

We'd sooner do it, a foine seet, nor root among th' Shurat;

We'n ne'er no floats to unweave neaw, we're reet enough, bi th'

mass,

For we couldn't have an easier job nor goin' to th' sewin' class.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

We're welly killed wi' kindness neaw, we really are, indeed,

For everybody's tryin' hard to get us o we need;

They'n sent us puddin's, bacon, too, an' lots o' decent clo'es,

An' what they'll send afore they'n done there's nob'dy here 'at

knows.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

God bless these kind, good-natured folk, 'at sends us o' this stuff,

We conno tell 'em o we feel, nor thank 'em hawve enuff;

They help to find us meat an' clooas, an' eddicashun, too,

An' what creawns o', they give us wage for goin' to th' sewin' schoo'.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

We'n sich a chance o' larnin' neaw we'n never had afore:

An' oh, we shall be rare an' wise when th' Yankee wars are o'er;

There's nob'dy then can puzzle us wi' owt we'n larned to do,

We'n getten polished up so weel wi' goin' to th' sewin' schoo'.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

Young fellows lookin' partners eawt had better come this way,

For, neaw we'n larned to mak' a shirt, we're ready ony day;

But mind, they'll ha' to ax us twice, an' mak' a deol ado,

We're gettin' rayther saucy neaw, wi' goin' to th' sewin' schoo'.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c.

There'll be some lookin' eawt for wives when th' factories start

ogen,

But we shall never court wi' noan but decent, sober men;

Soa vulgar chaps, beawt common sense, will ha' no need to come,

For sooner than wed sich as these, we'd better stop a whoam.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up and sing, &c.

Come, lasses, then, cheer up an' sing, it's no use lookin' sad,

We'll mak' eawr sewin' schoo' to ring, an' stitch away loike mad;

We live i' hopes afore so long, to see a breeter day,

For th' cleawd at's hangin' o'er us neaw is sure to blow away.

Chorus—Then, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing, &c. |

|

SAMUEL

LAYCOCK |

I spent an interesting half-hour with the secretary, after

which I went to see the factory operatives at work upon Preston Moor.

Preston Moor is a tract of waste land on the western edge of

the town. It belongs to the corporation. A little vale runs through a

great part of this moor, from south-east to north-west; and the ground

was, until lately, altogether uneven. On the town side of the little

dividing vale the land is a light, sandy soil; on the other side, there is

abundance of clay for brick-making.

|

|

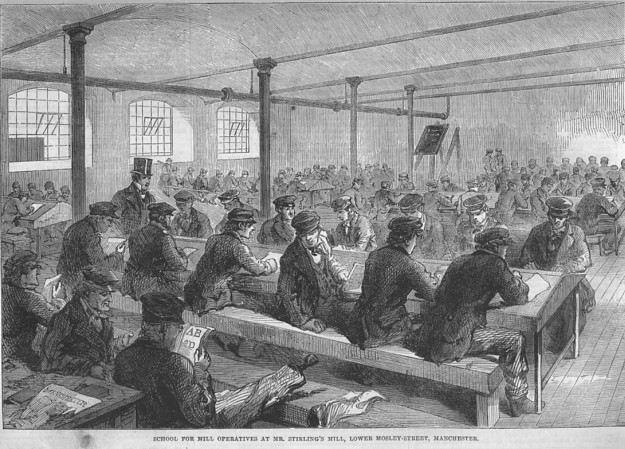

School for mill operatives at Mr. Stirling's mill,

Lower Mosely Street, Manchester.

Illustrated London News, November 29, 1862. |

Upon this moor there are now fifteen

hundred men, chiefly factory operatives, at work, levelling the land for

building purposes, and making a great main sewer for the drainage of

future streets. The men, being almost all unused to this kind of labour,

are paid only one shilling per day; and the whole scheme has been devised

for the employment of those who are suffering from the present depression

of trade.

The work had been going on several months before I saw it, and a

great part of the land was levelled. When I came in sight of the men,

working in scattered gangs that fine morning, there was, as might be

expected, a visible difference between their motions and those of trained

"navvies" engaged upon the same kind of labour. There were also very great

differences of age and physical condition amongst them ― old men and

consumptive-looking lads, hardly out of their teens. They looked hard at

me as I walked down the central line, but they were not anyway uncivil. "What time is 't, maister?" asked a middle-aged man, with gray hair, as he

wiped his forehead. "Hauve-past ten," said I. "What time says he?"

inquired a feeble young fellow, who was resting upon his barrow. "Hauve-past

ten, he says," replied the other. "Eh; it's warm!" said the tired lad,

lying down upon his barrow again. One thing I noticed amongst these men,

with very rare exceptions, their apparel, however poor, evinced that

wholesome English love of order and cleanliness which generally indicates

something of self-respect in the wearer ― especially among poor

folk. There is something touching in the whiteness of a well-worn shirt,

and the careful patches of a poor man's old fustian coat.

As I lounged about amongst the men, a mild-eyed policeman came up, and

offered to conduct me to Jackson, the labour-master, who had gone down to

the other end of the moor, to look after the men at work at the great

sewer ― a wet clay cutting ― the heaviest bit of work on the ground. We

passed some busy brick-makers, all plastered and splashed with wet clay

― of the earth, earthy. Unlike the factory operatives around them, these

men clashed, and kneaded, and sliced among the clay, as if they were

working for a wager. But they were used to the job, and working

piece-work.

A little further on, we came to an unbroken bit of the moor.

Here, on a green slope we saw a poor lad sitting chirruping upon the

grass, with a little cloutful of groundsel for bird meat in his hand,

watching another, who was on his knees, delving for earth-nuts with an old

knife. Lower down the slope there were three other lads plaguing a young

jackass colt; and further off, on the town edge of the moor, several

children from the streets hard by, were wandering about the green hollow,

picking daisies, and playing together in the sunshine.

There are several

cotton factories close to the moor, but they were quiet enough. Whilst I

looked about me here, the policeman pointed to the distance and said,

"Jackson's comin' up, I see. Yon's him, wi' th' white lin' jacket on."

Jackson seems to have won the esteem of the men upon the moor by his

judicious management and calm determination. I have heard that he had a

little trouble at first, through an injurious report spread amongst the

men immediately before he undertook the management. Some person previously

employed upon the ground had "set it eawt that there wur a chap comin'

that would make 'em addle a hauve-a-creawn a day for their shillin'." Of

course this increased the difficulty of his position; but he seems to have

fought handsomely through all that sort of thing. I had met him for a few

minutes once before, so there was no difficulty between us.

"Well, Jackson," said I, "heaw are yo gettin' on among it?" "Oh, very

well, very well," said he, "We'n more men at work than we had, an' we

shall happen have more yet. But we'n getten things into something like

system, an' then tak 'em one with another th' chaps are willin' enough. You see they're not men that have getten a livin' by idling aforetime;

they're workin' men, but they're strange to this job, an' one cannot

expect 'em to work like trained honds, no moor than one could expect a lot

o' navvies to work weel at factory wark. Oh, they done middlin', tak 'em

one with another."

I now asked him if he had not had some trouble with the

men at first. "Well," said he, "I had at first, an' that's the truth. I

remember th' first day that I came to th' job. As I walked on to th'

ground there was a great lump o' clay coom bang into my earhole th' first

thing; but I walked on, an' took no notice, no moor than if it had bin a

midge flyin' again my face. Well, that kind o' thing took place, now an'

then, for two or three days, but I kept agate o' never mindin'; till I

fund there were some things that I thought could be managed a deal better

in a different way; so I gav' th' men notice that I would have 'em

altered.

"For instance, now, when I coom here at first, there was a great

shed in yon hollow; an' every mornin' th' men had to pass through that

shed one after another, an' have their names booked for th' day. The

result wur, that after they'd walked through th' shed, there was many on 'em

walked out at t'other end o' th' moor straight into teawn a-playin' 'em. Well, I was determined to have that system done away with. An', when th'

men fund that I was gooin' to make these alterations, they growled a good

deal, you may depend, an' two or three on 'em coom up an' spoke to me

abeawt th' matter, while tother stood clustered a bit off. Well; I was beginnin' to tell 'em plain an' straight-forrud what I would have done,

when one o' these three sheawted out to th' whole lot, "Here, chaps, come

an' gether reawnd th' devil. Let's yer what he's for!"

"'Well,' said I,

'come on, an' you shall yer,' for aw felt cawmer just then, than I did

when it were o'er. There they were, gethered reawnd me in a minute, ― th'

whole lot, ― I were fair hemmed in. But I geet atop ov a bit ov a knowe,

an' towd 'em a fair tale, ― what I wanted, an' what I would have, an' I

put it to 'em whether they didn't consider it reet. An' I believe they see'd th' thing in a reet leet, but they said nought about it, but went

back to their wark, lookin' sulky. But I've had very little bother with 'em

sin'.

"I never see'd a lot o' chaps so altered sin' th' last February, as

they are. At that time no mortal mon hardly could walk through 'em 'beawt

havin' a bit o' slack-jaw, or a lump o' clay or summat flung a-him. But it

isn't so, neaw. I consider th' men are doin' very weel. But, come; yo mun

go deawn wi' me a-lookin' at yon main sewer."

CHAPTER XIV.

|

"Oh, let us bear the present as we may,

Nor let the golden past be all forgot;

Hope lifts the curtain of the future day,

Where peace and plenty smile without a spot

On their white garments; where the human lot

Looks lovelier and less removed from heaven;

Where want, and war, and discord enter not,

But that for which the wise have hoped and striven ―

The wealth of happiness, to humble worth is given.

"The time will come, as come again it must,

When Lancashire shall lift her head once more;

Her suffering sons, now down amid the dust

Of Indigence, shall pass through Plenty's door;

Her commerce cover seas from shore to shore;

Her arts arise to highest eminence;

Her products prove unrivall'd, as of yore;

Her valour and her virtue ― men of sense

And blue-eyed beauties ― England's pride and her defence."

― Blackburn Bard. |

Jackson's office as labour-master kept him constantly

tramping about the sandy moor from one point to another. He was

forced to be in sight, and on the move, during working hours, amongst his

fifteen hundred scattered workmen. It was heavy walking, even in dry

weather; and as we kneaded through the loose soil that hot forenoon, we

wiped our foreheads now and then. "Ay," said he, halting, and

looking round upon the scene, "I can assure you, that when I first took

howd o' this job, I fund my honds full, as quiet as it looks now. I

was laid up for nearly a week, an' I had to have two doctors. But,

as I'd undertakken the thing, I was determined to go through with it to th'

best o' my ability; an' I have confidence now that we shall be able to

feight through th' bad time wi' summat like satisfaction, so far as this

job's consarned, though it's next to impossible to please everybody, do

what one will. But come wi' me down this road. I've some men

agate o' cuttin' a main sewer. It's very little farther than where

th' cattle pens are i' th' hollow yonder; and it's different wark to what

you see here. Th' main sewer will have to be brought clean across i'

this direction, an' it'll be a stiffish job. Th' cattle market's

goin' to be shifted out o' yon hollow, an' in another year or two th'

whole scene about here will be changed."

Jackson and I both remembered something of the troubles of

the cotton manufacture in past times. We had seen something of the

"shuttle gatherings," the "plug-drawings," the wild starvation riots, and

strikes of days gone by; and he agreed with me that one reason for the

difference of their demeanour during the present trying circumstances lies

in their increasing intelligence. The great growth of free

discussion through the cheap press has done no little to work out this

salutary change. There is more of human sympathy, and of a

perception of the union of interests between employers and employed than

ever existed before in the history of the cotton trade. Employers

know that their workpeople are human beings, of like feelings and passions

with themselves, and like themselves, endowed with no mean degree of

independent spirit and natural intelligence; and working men know better

than beforetime that their employers are not all the heartless tyrants

which it has been too fashionable to encourage them to believe. The

working men have a better insight into the real causes of trade panics

than they used to have; and both masters and men feel more every day that

their fortunes are naturally bound together for good or evil; and if the

working men of Lancashire continue to struggle through the present trying

pass of their lives with the brave patience which they have shown

hitherto, they will have done more to defeat the arguments of those who

hold them to be unfit for political power than the finest eloquence of

their best friends could have done in the same time.

The labour master and I had a little talk about these things

as we went towards the lower end of the moor. A few minutes' slow

walk brought us to the spot, where some twenty of the hardier sort of

operatives were at work in a damp clay cutting. "This is heavy work

for sich chaps as these," said Jackson; "but I let 'em work bi'th lump

here. I give'em so much clay apiece to shift, and they can begin

when they like, an' drop it th' same. Th' men seem satisfied wi'

that arrangement, an' they done wonders, considerin' th' nature o'th job.

There's many o'th men that come on to this moor are badly off for suitable

things for their feet. I've had to give lots o' clogs away among'em.

You see men cannot work with ony comfort among stuff o' this sort without

summat substantial on. It rives poor shoon to pieces i' no time.

Beside, they're not men that can ston bein' witchod (wetshod) like some.

They haven't been used to it as a rule. Now, this is one o'th'

finest days we've had this year; an' you haven't sin what th' ground is

like in bad weather. But you'd be astonished what a difference wet

makes on this moor. When it's bin rain for a day or two th' wark's

as heavy again. Th' stuff's heavier to lift, an' worse to wheel; an'

th' ground is slutchy. That tries 'em up, an' poo's their shoon to

pieces; an' men that are wakely get knocked out o' time with it. But

thoose that can stand it get hardened by it. There's a great

difference; what would do one man's constitution good will kill another.

Winter time 'll try 'em up tightly. . . Wait there a bit," continued he,

"I'll be with you again directly."

He then went down into the cutting to speak to some of his

men, whilst I walked about the edge of the bank. From a distant part

of the moor, the bray of a jackass came faint upon the sleepy wind.

"Yer tho', Jone," said one of the men, resting upon his spade; "another

cally-weighver gone!" "Ay," replied Jone, "th' owd lad's deawn't his

cut. He'll want no more tickets, yon mon!" The country folk of

Lancashire say that a weaver dies every time a jackass brays.

Jackson came up from the cutting, and we walked back to where

the greatest number of men were at work. "You should ha' bin here

last Saturday," said he; "we'd rather a curious scene. One o' the

men coom to me an' axed if I'd allow 'em hauve-an-hour to howd a meetin'

about havin' a procession i' th' guild week. I gav' 'em consent, on

condition that they'd conduct their meetin' in an orderly way. Well,

they gethered together upo' that level theer; an' th' speakers stood upo'

th' edge o' that cuttin', close to Charnock Fowd. Th' meetin' lasted

abeawt a quarter ov an hour longer than I bargained for; but they lost no

time wi' what they had to do. O' went off quietly; an' they finished

with 'Rule Britannia,' i' full chorus, an' then went back to their wark.

You'll see th' report in today's paper."

This meeting was so curious, and so characteristic of the

men, that I think the report is worth repeating here: ―

"On Saturday afternoon, a meeting of the

parish labourers was held on the moor, to consider the propriety of having

a demonstration of their numbers on one day in the guild week. There

were upwards of a thousand present. An operative, named John Houlker,

was elected to conduct the proceedings. After stating the object of

the assembly, a series of propositions were read to the meeting by William

Gillow, to the effect that a procession take place of the parish labourers

in the guild week; that no person be allowed to join in it except those

whose names were on the books of the timekeepers; that no one should

receive any of the benefits which might accrue who did not conduct himself

in an orderly manner; that all persons joining the procession should be

required to appear on the ground washed and shaven, and their clogs,

shoes, and other clothes cleaned; that they were not expected to purchase

or redeem any articles of clothing in order to take part in the

demonstration; and that any one absenting himself from the procession

should be expelled from any participation in the advantages which might

arise from the subscriptions to be collected by their fellow-labourers.

These were all agreed to, and a committee of twelve was appointed to

collect subscriptions and donations. A president, secretary, and

treasurer were also elected, and a number of resolutions agreed to in

reference to the carrying out of the details of their scheme. The

managing committee consist of Messrs W. Gillow, Robert Upton, Thomas

Greenwood Riley, John Houlker, John Taylor, James Ray, James Whalley, Wm.

Banks, Joseph Redhead, James Clayton, and James McDermot. The men

agreed to subscribe a penny per week to form a fund out of which a dinner

should be provided, and they expressed themselves confident that they

could secure the gratuitous services of a band of music. During the

meeting there was great order. At the conclusion, a vote of thanks

was accorded to the chairman, to the labour master for granting them

three-quarters of an hour for the purpose of holding the meeting, and to

William Gillow for drawing up the resolutions. Three times three

then followed; after which, George Dewhurst mounted a hillock, and, by

desire, sang 'Rule Britannia,' the chorus being taken up by the whole

crowd, and the whole being wound up with a hearty cheer."

There are various schemes devised in Preston for regaling the

poor during the guild; and not the worst of them is the proposal to give

them a little extra money for that week, so as to enable them to enjoy the

holiday with their families at home.

It was now about half-past eleven. "It's getting on for

dinner time," said Jackson, looking at his watch. "Let's have a look

at th' opposite side yonder; an' then we'll come back, an' you'll see th'

men drop work when the five minutes' bell rings. There's many of 'em

live so far off that they couldn't well get whoam an' back in an hour; so,

we give'em an hour an' a half to their dinner, now, an' they work half an'

hour longer i'th afternoon."

We crossed the hollow which divides the moor, and went to the

top of a sandy cutting at the rear of the workhouse. This eminence

commanded a full view of the men at work on different parts of the ground,

with the time-keepers going to and fro amongst them, book in hand.

Here were men at work with picks and spades; there, a slow-moving train of

full barrows came along; and, yonder, a train of empty barrows stood, with

the men sitting upon them, waiting. Jackson pointed out some of his

most remarkable men to me; after which we went up to a little plot of

ground behind the workhouse, where we found a few apparently older or

weaker men, riddling pebbly stuff, brought from the bed of the Ribble.

The smaller pebbles were thrown into heaps, to make a hard floor for the

workhouse schoolyard. The master of the workhouse said that the

others were too big for this purpose ― the lads would break the windows

with them. The largest pebbles were cast aside to be broken up, for

the making of garden walks.

Whilst the master of the workhouse was showing us round the

building, Jackson looked at his watch again, and said, "Come, we've just

time to get across again. Th' bell will ring in two or three

minutes, an' I should like yo to see 'em knock off." We hurried over

to the other side, and, before we had been a minute there, the bell rung.

At the first toll, down dropt the barrows, the half-flung shovelfuls fell

to the ground, and all labour stopt as suddenly as if the men had been

moved by the pull of one string. In two minutes Preston Moor was

nearly deserted, and, like the rest, we were on our way to dinner.

AMONG THE WIGAN

OPERATIVES

CHAPTER XV.

|

"There'll be some on us missin', aw deawt,

Iv there isn't some help for us soon."

― Samuel

Laycock. |

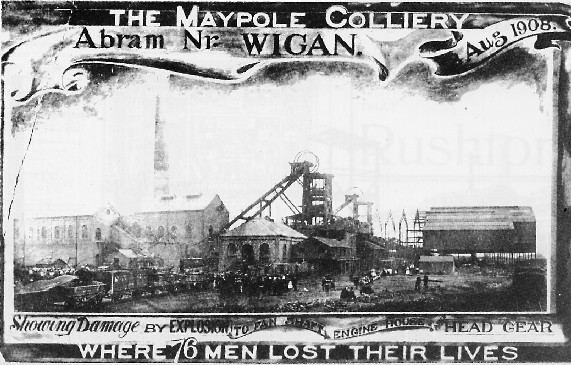

The next scene of my observations is the town of Wigan. The

temporary troubles now affecting the working people of Lancashire wear a

different aspect there on account of such a large proportion of the

population being employed in the coal mines. The "way of life" and the

characteristics of the people are marked by strong peculiarities. But,

apart from these things, Wigan is an interesting place.

The towns of

Lancashire have undergone so much change during the last fifty years that

their old features are mostly either swept away entirely, or are drowned

in a great overgrowth of modern buildings. Yet coaly Wigan retains visible

relics of its ancient character still; and there is something striking in

its situation. It is associated with some of the most stirring events of

our history, and it is the scene of many an interesting old story, such as

the legend of Mabel of Haigh Hall, the crusader's dame. The remnant of "Mab's

Cross" still stands in Wigan Lane. Some of the finest old halls of

Lancashire are now, and have been, in its neighbourhood, such as Ince Hall

and Crooke Hall. It must have been a picturesque town in the time of the

Commonwealth, when Cavaliers and Roundheads met there in deadly

contention. Wigan saw a great deal of the troubles of that time. The

ancient monument, erected to the memory of Colonel Tyldesley, upon the

ground where he fell at the battle of Wigan Lane, only tells a little of

the story of Longfellow's puritan hero, Miles Standish, who belonged to

the Chorley branch of the family of Standish of Standish, near this town. The ingenious John Roby, author of the "Traditions of Lancashire," was

born here. Round about the old market-place, and the fine parish church of

St Wilfred, there are many quaint nooks still left to tell the tale of

centuries gone by. These remarks, however, by the way. It is almost

impossible to sunder any place entirely from the interest which such

things lend to it.

Our present business is with the share which Wigan feels of the troubles

of our own time, and in this respect it is affected by some conditions

peculiar to the place. I am told that Wigan was one of the first ― if not

the very first ― of the towns of Lancashire to feel the nip of our present

distress. I am told, also, that it was the first town in which a Relief

Committee was organised.

The cotton consumed here is almost entirely of

the kind from ordinary to middling American, which is now the scarcest and

dearest of any. Preston is almost wholly a spinning town. In Wigan there

is a considerable amount of weaving as well as spinning. The counts spun

in Wigan are lower than those in Preston; they range from 10's up to 20's.

There is also, as I have said before, another peculiar element of labour,

which tends to give a strong flavour to the conditions of life in Wigan,

that is, the great number of people employed in the coal mines. This,

however, does not much lighten the distress which has fallen upon the

spinners and weavers, for the colliers are also working short time ― an

average of four days a week. I am told, also, that the coal miners have

been subject to so many disasters of various kinds during past years, that

there is now hardly a collier's family which has not lost one or more of

its most active members by accidents in the pits. About six years ago, the

river Douglas broke into one of the Ince mines, and nearly two hundred

people were drowned thereby. These were almost all buried on one day, and

it was a very distressing scene.

Everywhere in Wigan one may meet with the

widows and orphans of men who have been killed in the mines; and there are

no few men more or less disabled by colliery accidents, and, therefore,

dependent either upon the kindness of their employers, or upon the labour

of their families in the cotton factories. This last failing them, the

result may be easily guessed. The widows and orphans of coal miners almost

always fall back upon factory labour for a living; and, in the present

state of things, this class of people forms a very helpless element of the

general distress. These things I learnt during my brief visit to the town

a few days ago. Hereafter, I shall try to acquaint myself more deeply and

widely with the relations of life amongst the working people there.

I had not seen Wigan during many years before that fine August afternoon.

In the Main Street and Market Place there is no striking outward sign of

distress, and yet here, as in other Lancashire towns, any careful eye may

see that there is a visible increase of mendicant stragglers, whose

awkward plaintiveness, whose helpless restraint and hesitancy of manner,

and whose general appearance, tell at once that they belong to the

operative classes now suffering in Lancashire.

'Pitbrow lasses' sorting coal, Wigan ― courtesy of

wiganworld.

Beyond this, the sights I

first noticed upon the streets, as peculiar to the place, were, here, two

"Sisters of Mercy," wending along, in their black cloaks and hoods, with

their foreheads and cheeks swathed in ghastly white bands, and with strong

rough shoes upon their feet; and, there, passed by a knot of the women

employed in the coal mines. The singular appearance of these women has

puzzled many a southern stranger. All grimed with coal dust, they swing

along the street with their dinner baskets and cans in their hands,

chattering merrily. To the waist they are dressed like men, in strong

trousers and wooden clogs. Their gowns, tucked clean up, before, to the

middle, hang down behind them in a peaked tail. A limp bonnet, tied under

the chin, makes up the head-dress. Their curious garb, though soiled, is

almost always sound; and one can see that the wash-tub will reveal many a

comely face amongst them. The dusky damsels are "to the manner born," and

as they walk about the streets, thoughtless of singularity, the Wigan

people let them go unheeded by.

Before I had been two hours in the town, I

was put into communication with one of the active members of the Relief

Committee, who offered to devote a few hours of the following day to

visitation with me, amongst the poor of a district called "Scholes," on

the eastern edge of the town. Scholes is the "Little Ireland" of Wigan,

the poorest quarter of the town. The colliers and factory operatives

chiefly live there. There is a saying in Wigan ― that, no man's

education is finished until he has been through Scholes. Having made my

arrangements for the next day, I went to stay for the night with a friend

who lives in the green country near Orrell, three miles west of Wigan.

Early next morning, we rode over to see the quaint town of Upholland, and

its fine old church, with the little ivied monastic ruin close by. We

returned thence, by way of "Orrell Pow," to Wigan, to meet my engagement

at ten in the forenoon. On our way, we could not help noticing the unusual

number of foot-sore, travel-soiled people, many of them evidently factory

operatives, limping away from the town upon their melancholy wanderings. We could see, also, by the number of decrepid old women, creeping towards

Wigan, and now and then stopping to rest by the wayside, that it was

relief day at the Board of Guardians.

At ten, I met the gentleman who had

kindly offered to guide me for the day; and we set off together. There are

three excellent rooms engaged by the good people of Wigan for the

employment and teaching of the young women thrown out of work at the

cotton mills. The most central of the three is the lecture theatre of the

Mechanics' Institution. This room was the first place we visited.

Ten

o'clock is the time appointed for the young women to assemble. It was a

few minutes past ten when we got to the place; and there were some twenty

of the girls waiting about the door. They were barred out, on account of

being behind time. The lasses seemed very anxious to get in; but they were

kept there a few minutes till the kind old superintendent, Mr Fisher, made

his appearance. After giving the foolish virgins a gentle lecture upon the

value of punctuality, he admitted them to the room. Inside, there were

about three hundred and fifty girls mustered that morning. They are

required to attend four hours a day on four days of the week, and they are

paid 9d. a day for their attendance. They are divided into classes, each

class being watched over by some lady of the committee. Part of the time

each day is set apart for reading and writing; the rest of the day is

devoted to knitting and plain sewing.

The business of each day begins with

the reading of the rules, after which, the names are called over. A girl

in a white pinafore, upon the platform, was calling over the names when we

entered. I never saw a more comely, clean, and orderly assembly anywhere. I never saw more modest demeanour, nor a greater proportion of healthy,

intelligent faces in any company of equal numbers.

CHAPTER XVI.

|

"Hopdance cries in Tom's belly for two white

herrings.

Croak not, black angel; I have no food for thee."

― King Lear. |

I lingered a little while in the work-room, at the Mechanics'

Institution, interested in the scene. A stout young woman came in at a

side door, and hurried up to the centre of the room with a great roll of

coarse gray cloth, and lin check, to be cut up for the stitchers. One or

two of the classes were busy with books and slates; the remainder of the

girls were sewing and knitting; and the ladies of the committee were

moving about, each in quiet superintendence of her own class.

The room was

comfortably full, even on the platform; but there was very little noise,

and no disorder at all. I say again that I never saw a more comely, clean,

and well conducted assembly than this of three hundred and fifty factory

lasses. I was told, however, that even these girls show a kind of pride of

caste amongst one another. The human heart is much the same in all

conditions of life. I did not stay long enough to be able to say more

about this place; but one of the most active and intelligent ladies

connected with the management said to me afterwards, "Your wealthy

manufacturers and merchants must leave a great deal of common stuff lying

in their warehouses, and perhaps not very saleable just now, which would

be much more valuable to us here than ever it will be to them. Do you

think they would like to give us a little of it if we were to ask them

nicely?" I said I thought there were many of them who would do so; and I

think I said right.

After a little talk with the benevolent old superintendent, whose heart, I

am sure, is devoted to the business for the sake of the good it will do,

and the evil it will prevent, I set off with my friend to see some of the

poor folk who live in the quarter called "Scholes." It is not more than

five hundred yards from the Mechanics' Institution to Scholes Bridge,

which crosses the little river Douglas, down in a valley in the eastern

part of the town. As soon as we were at the other end of the bridge, we

turned off at the right hand corner into a street of the poorest sort ― a

narrow old street, called "Amy Lane." A few yards on the street we came to

a few steps, which led up, on the right hand side, to a little terrace of

poor cottages, overlooking the river Douglas. We called at one of these

cottages.

Though rather disorderly just then, it was not an uncomfortable

place. It was evidently looked after by some homely dame. A clean old cat

dosed upon a chair by the fireside. The bits of cottage furniture, though

cheap, and well worn, were all there; and the simple household gods, in

the shape of pictures and ornaments, were in their places still. A

hardy-looking, brown-faced man, with close-cropped black hair, and a mild

countenance, sat on a table by the window, making artificial flies, for

fishing. In the corner over his head a cheap, dingy picture of the trial

of Queen Catherine, hung against the wall. I could just make out the tall

figure of the indignant queen, in the well-known theatrical attitude, with

her right arm uplifted, and her sad, proud face turned away from the

judgment-seat, where Henry sits, evidently uncomfortable in mind, as she

gushes forth that bold address to her priestly foes and accusers.

|

|

|

Wigan: Old Folley ― courtesy of wiganworld. |

The man

sitting beneath the picture, told us that he was a throstle-overlooker by

trade; and that he had been nine months out of work. He said, "There's

five on us here when we're i'th heawse. When th' wark fell off I had a bit

o' brass save't up, so we were forced to start o' usin' that. But month

after month went by, an' th' brass kept gettin' less, do what we would;

an' th' times geet wur, till at last we fund ersels fair stagged up. At

after that, my mother helped us as weel as hoo could, ― why, hoo does neaw,

for th' matter o' that, an' then aw've three brothers, colliers; they've

done their best to poo us through. But they're nobbut wortchin' four days

a week, neaw; besides they'n enough to do for their own. Aw make no acceawnt o' slotchin' up an' deawn o' this shap, like a foo. It would

sicken a dog, it would for sure. Aw go a fishin' a bit neaw an' then; an'

aw cotter abeawt wi' first one thing an' then another; but it comes to no

sense. Its noan like gradely wark. It makes me maunder up an' deawn, like

a gonnor wi' a nail in it's yed. Aw wish to God yon chaps in Amerikey

would play th' upstroke, an' get done wi' their bother, so as folk could

start o' their wark again." This was evidently a provident man, who had

striven hard to get through his troubles decently. His position as overlooker, too, made him dislike the thoughts of receiving relief amongst

the operatives whom he might some day be called upon to superintend again.

A little higher up in Amy Lane we came to a kind of square. On the side

where the lane continues there is a dead brick wall; on the other side,

bounding a little space of unpaved ground, rather higher than the lane,

there are a few old brick cottages, of very mean and dirty appearance. At

the doors of some of the cottages squalid, untidy women were lounging;

some of them sitting upon the doorstep, with their elbows on their knees,

smoking, and looking stolidly miserable.

We were now getting near where

the cholera made such havoc during its last visit, ― a pestilent jungle,

where disease is always prowling about, "seeking whom it can devour." A

few sallow, dirty children were playing listlessly about the space, in a

melancholy way, looking as if their young minds were already "sicklied

o'er with the pale cast of thought," and unconsciously oppressed with

wonder why they should be born to such a miserable share of human life as

this. A tall, gaunt woman, with pale face, and thinly clad in a worn and

much-patched calico gown, and with a pair of "trashes" upon her stockingless feet, sat on the step of the cottage nearest the lane. The

woman rose when she saw my friend. "Come in," said she; and we followed

her into the house.

|

|

Wigan: Little London ― courtesy of wiganworld. |

It was a wretched place; and the smell inside was

sickly. I should think a broker would not give half-a-crown for all the

furniture we saw. The woman seemed simple-minded and very illiterate; and

as she stood in the middle of the floor, looking vaguely round she said,

"Aw can hardly ax yo to sit deawn, for we'n sowd o' th' things eawt o'th

heawse for a bit o' meight; but there is a cheer theer, sich as it is; see

yo; tak' that." When she found that I wished to know something of her

condition ― although this was already well known to the gentleman who

accompanied me ― she began to tell her story in a simple, off-hand way. "Aw've

had nine childer," said she; "we'n buried six, an' we'n three alive, an'

aw expect another every day."

In one corner there was a rickety little low

bedstead. There was no bedding upon it but a ragged kind of quilt, which

covered the ticking. Upon this quilt something lay, like a bundle of rags,

covered with a dirty cloth. "There's one o' th' childer, lies here, ill,"

said she. "It's getten' th' worm fayver." When she uncovered that little

emaciated face, the sick child gazed at me with wild, burning eyes, and

began to whine pitifully. "Husht, my love," said the poor woman; "he'll not

hurt tho'! Husht, now; he's noan beawn to touch tho'! He's noan o'th

doctor, love. Come, neaw, husht; that's a good lass!"

I gave the little

thing a penny, and one way and another we soothed her fears, and she

became silent; but the child still gazed at me with wild eyes, and the

forecast of death on its thin face. The mother began again, "Eh, that

little thing has suffered summat," said she, wiping her eyes; "an', as aw

towd yo before, aw expect another every day. They're born nake't, an' th'

next'll ha' to remain so, for aught that aw con see. But, aw dar not begin

o' thinkin' abeawt it. It would drive me crazy. We han a little lad o' mi

sister's livin' wi' us. Aw had to tak' him when his mother deed. Th'

little thing's noather feyther nor mother, neaw. It's gwon eawt a beggin'

this morning wi' my two childer. My mother lives with us, too," continued

she; "hoo's gooin' i' eighty-four, an' hoo's eighteen pence a week off th'

teawn. There's seven on us, o'together, an' we'n had eawr share o'

trouble, one way an' another, or else aw'm chetted.

|

|

Wigan: collier (note the clogs) ― courtesy of

wiganworld. |

"Well, aw'll tell yo'

what happened to my husban' o' i' two years' time. My husban's a collier. Well, first he wur brought whoam wi' three ribs broken

― aw wur lyin' in

when they brought him whoam. An' then, at after that, he geet his arm

broken; an' soon after he'd getten o'er that, he wur nearly brunt to

deeath i' one o'th pits at Ratcliffe; an' aw haven't quite done yet, for,

after that, he lee ill o'th rheumatic fayver sixteen week. That o' happen't i' two years' time. It's God's truth, maister. Mr Lea knows summat abeawt it

― an' he stons theer. Yo may have a like aim what we'n had

to go through. An' that wur when times were'n good; but then, everything

o' that sort helps to poo folk deawn, yo known. We'n had very hard deed,

maister ― aw consider we'n had as hard deed as anybody livin', takkin' o'

together."

This case was an instance of the peculiar troubles to which

colliers and their families are liable; a little representative bit of

life among the poor of Wigan.

|

|

|

Wigan: collier

― courtesy wiganworld. |

From this place we went further up into Scholes, to a dirty square, called the "Coal Yard." Here we called at the

house of Peter Y―, a man of fifty-one, and a weaver of a kind of stuff

called, "broad cross-over," at which work he earned about six shillings a

week, when in full employ. His wife was a cripple, unable to help herself;

and, therefore, necessarily a burden. Their children were two girls, and

one boy. The old woman said, "Aw'm always forced to keep one o'th lasses

a-whoam, for aw connot do a hond's turn." The children had been brought up

to factory labour; but both they and their father had been out of work

nearly twelve months. During that time the family had received relief

tickets, amounting to the value of four shillings a week. Speaking of the

old man, the mother said, "Peter has just getten a bit o' wark again,

thank God. He's hardly fit for it; but he'll do it as lung as he can keep ov his feet."

CHAPTER XVII.

|

"Lord! how the people suffer day by day

A lingering death, through lack of honest bread;

And yet are gentle on their starving way,

By faith in future good and justice led."

― Blackburn Bard. |

It is a curious thing to note the various combinations of

circumstance which exist among the families of the poor. On the

surface they seem much the same; and they are reckoned up according to

number, income, and the like. But there are great differences of

feeling and cultivation amongst them; and then, every household has a

story of its own, which no statistics can tell. There is hardly a

family which has not had some sickness, some stroke of disaster, some

peculiar sorrow, or crippling hindrance, arising within itself, which

makes its condition unlike the rest. In this respect each family is

one string in the great harp of humanity ― a string which, touched by the

finger of Heaven, contributes a special utterance to that universal

harmony which is too fine for mortal ears.

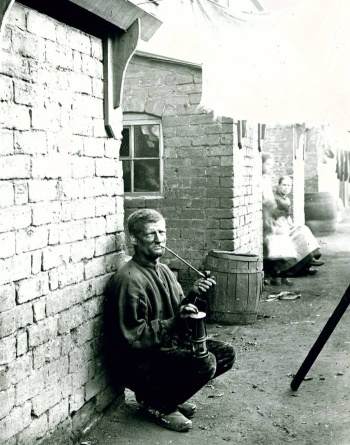

|

|

|

Eagle Court, Blackburn.

Courtesy 'Cotton Town digization project'. |

From the old weaver's house in "Coal Yard" we went to a

place close by, called "Castle Yard," one of the most unwholesome nooks I

have seen in Wigan yet, though there are many such in that part of the

town. It was a close, pestilent, little cul de sac, shut in by a

dead brick wall at the far end. Here we called upon an Irish family,

seven in number. The mother and two of her daughters were in.

The mother had sore eyes. The place was dirty, and the air inside

was close and foul. The miserable bits of furniture left were fit

for nothing but a bonfire.

"Good morning, Mrs K ― ," said my friend, as we entered the

stifling house; "how are you getting on?" The mother stood in the

middle of the floor, wiping her sore eyes, and then folding her hands in a

tattered apron; whilst her daughters gazed upon us vacantly from the

background. "Oh, then," replied the woman, "things is worse wid us

entirely, sir, than whenever ye wor here before. I dunno what will

we do whin the winter comes." In reply to me, she said, "We are

seven altogether, wid my husband an' myself. I have one lad was ill

o' the yallow jaundice this many months, an' there is somethin' quare

hangin' over that boy this day; I dunno whatever shall we do wid him.

I was thinkin' this long time could I get a ricommind to see would the

doctor give him anythin' to rise an appetite in him at all. By the

same token, I know it is not a convanient time for makin' appetites in

poor folk just now. But perhaps the doctor might be able to do him