|

CHAPTER I.

RIOTS OF 1815 AND 1816—WILLIAM COBBETT—HAMPDEN CLUBS—DELEGATE

MEETINGS—LEADERS OF REFORM—THE FIRST TRAITOR.

|

|

|

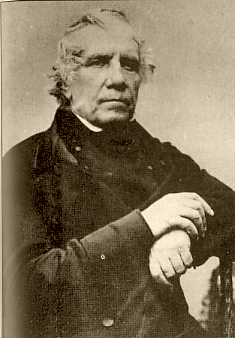

Samuel Bamford (ca. 1860) |

IT is matter of history that whilst the laurels were

yet cool on the brows of our victorious soldiers on their second

occupation of Paris, the elements of convulsion were at work amongst the

masses of our labouring population; and that a series of disturbances

commenced with the introduction of the Corn Bill in 1815, and continued,

with short intervals, until the close of the year 1816. In London and

Westminster riots ensued, and were continued for several days whilst the

bill was discussed; at Bridport, there were riots on account of the high

price of bread; at Bideford there were similar disturbances to prevent the

exportation of grain; at Bury, by the unemployed, to destroy machinery; at

Ely, not suppressed without bloodshed; at Newcastle-on-Tyne, by colliers

and others; at Glasgow, where blood was shed; at Preston, by unemployed

weavers; at Nottingham, by Luddites, who destroyed thirty frames; at

Merthyr Tydvil, on a reduction of wages; at Birmingham, by the unemployed;

and at Dundee, where, owing to the high price of meal, upwards of one

hundred shops were plundered. At this time the writings of William Cobbett

suddenly became of great authority; they were read on nearly every cottage

hearth in the manufacturing districts of South Lancashire, in those of

Leicester, Derby, and Nottingham; also in many of the Scottish

manufacturing towns. Their influence was speedily visible. He

directed his readers to the true cause of their sufferings—misgovernment;

and to its proper corrective—parliamentary reform. Riots soon become

scarce, and from that time they have never obtained their ancient vogue

with the labourers of this country.

Let us not descend to be unjust. Let us not withhold

the homage which, with all the faults of William Cobbett, is still due to

his great name. Instead of riots and destruction of property,

Hampden clubs were now established in many of our large towns, and the

villages and districts around them. Cobbett's books were printed in

a cheap form; the labourers read them, and thenceforward became deliberate

and systematic in their proceedings. Nor were there wanting men of

their own class, to encourage and direct the new converts. The

Sunday Schools of the preceding thirty years had produced many working men

of sufficient talent to become readers, writers, and speakers in the

village meetings for parliamentary reform. Some also were found to

possess a rude poetic talent, which rendered their effusions popular, and

bestowed an additional charm on their assemblages; and by such various

means, anxious listeners at first, and then zealous proselytes, were drawn

from the cottages of quiet nooks and dingles, to the weekly readings and

discussions of the Hampden clubs. One of these clubs was established

in 1816, at the small town of Middleton, near Manchester; and I, having

been instrumental in its formation, a tolerable reader also, and a rather

expert writer, was chosen secretary. The club prospered, the number

of men increased, the funds raised by contributions of a penny a week

became more than sufficient for all out-goings, and, taking a bold step,

we soon rented a chapel which had been given up by a society of Kilhamite

Methodists. This place we threw open for the religious worship of

all sects and parties, and there we held our meetings on the evenings of

Monday and Saturday in each week. The proceedings of our society;

its place of meeting—singular as being the first place of worship occupied

by reformers (for so in those days we were termed), together with the

services of religion connected with us—drew a considerable share of public

attention to our transactions, and obtained for the leaders some

notoriety. They, like the young aspirants of the present, and all

the other days, whose heads are as warm as their hearts, could sing with

old John Bunyan—

|

"Then fancies fly away,

We fear not what men say." |

Several meetings of delegates from the surrounding districts were held at

our chapel, on which occasions the leading reformers of Lancashire were

generally seen together. One of our delegate meetings deserves

particular notice. It was held on Sunday, the 16th December, 1816,

when it was determined to send out missionaries to other towns and

villages, particularly to Yorkshire. The experiment was considered

somewhat hazardous, for at that time the great towns of Yorkshire,

Halifax, Bradford, and Leeds, to which they were bound, had shown but

small sympathy with the cause of reform. They went, however, and, I

believe, made an impression which awakened the cause in that county.

At this meeting a man of the name of William Wilson appeared as the

delegate from Moston; he was known to several present, and, being

considered a good reformer, was chosen secretary for the occasion.

He thus took copies of all the resolutions and proceedings. Soon

afterwards it was discovered that he was in communication with the police

of Manchester. He then left the district, abandoning his wife and a

young family of children, and was next heard of as a police officer in

London, to which place his wife and children followed him. Can this

have been our first traitor?

On the 1st of January, 1817, a meeting of delegates from

twenty-one petitioning bodies was held in our chapel, when resolutions

were passed declaratory of the right of every male to vote, who paid

taxes; that males of eighteen should be eligible to vote; that parliaments

should be elected annually; that no placeman or pensioner should sit in

parliament; that every twenty thousand inhabitants should send a member to

the House of Commons; and that talent and virtue were the only

qualifications necessary. Such were the moderate views and wishes of

the reformers in those days, as compared with the present. The

ballot was not insisted upon as a part of reform. [1]

Concentrating our whole energy for the obtainment of annual parliaments

and universal suffrage, we neither interfered with the House of Lords, nor

the bench of bishops, nor the working of factories, nor the corn laws, nor

the payment of members, nor tithes, nor church rates, nor a score of other

matters which in these days have been pressed forward with the effect of

distracting the attention and weakening the exertions of reformers; any

one or all of which matters would be far more likely to succeed with a

House of Commons elected on the suffrage we claimed than with one returned

as at present. [2] Quoting scripture, we did, in

fact say, first obtain annual parliaments, and universal suffrage, and,

"all these things shall be added unto you."

Some of the nostrum-mongers of the present day would have

been made short work of by the reformers of that time; they would not have

been tolerated for more than one speech, but handed over to the civil

power. It was not until we became infested by spies, incendiaries,

and their dupes—distracting, misleading, and betraying—that physical force

was mentioned amongst us. After that our moral power waned, and what

we gained by the accession of demagogues, we lost by their criminal

violence, and the estrangement of real friends.

CHAPTER II.

AUTHOR'S VIEWS ON EDUCATION AND ANNUAL PARLIAMENTS.

IT may not be amiss to state that the opinions

contained in this work, whether of persons or transactions, are those of

the writer at the period they refer to. Time, the ameliorator of all

things, has not passed him without leaving some experience; and the

lessons of that severe handmaid, making him better acquainted with mankind

and himself, have somewhat matured his judgment and increased his charity;

changing also, he hopes for the better, some of his views both of men and

things. Hence, though elsewhere he will speak of the conduct of

Henry, now Lord Brougham, strongly, as he felt at the time; he would, in

his present frame of mind, make large allowances. Our educators are,

after all, the best reformers, and are doing the best for their country,

whether they intend so or not. In this respect, Lord Brougham is the

greatest man we have. He led popular education from the dark and

narrow crib where he found it, like a young colt, saddled and cruelly

bitted by ignorance, for superstition to ride. He cut the straps

from its sides and the bridle from its jaws, and sent it forth strong,

beautiful, and free. [3]

Still, we want something more than mere intellectuality; that

is already vigorous in produce, whilst souls lie comparatively waste.

The Persians of old first taught their children to speak the truth, and

that was a wise beginning; but, like the embalming of the Egyptians, lost

to the present day. The young mothers of England, and the anxious

fathers, should do more—they should give life to the souls of their

offspring, and encourage and strengthen as well as comfort their young

hearts. Their constant lesson should be, "With thy whole soul, love

and support whatsoever is right. With thy whole soul, hate and

oppose whatsoever is wrong. Fear not anything, save the

contamination of sin." The schoolmaster might then finish the

intellect; and the spirit of Him who said, "Father, forgive them," should

be invoked to shed its dove-like mercy over all. Education so

grounded and built upon, would bring us hearts, and brave ones too,

brimful of nobleness and truth, and heads to work anything requisite for

their country. Intellect neglected may be repaired; but a soul once

in ruin, nothing human can restore.

Nor would the writer at the present day be found praying for

annual parliaments, though he would endeavour to attain the same end by

better means. Annual general elections would, he is convinced, be a

great political evil to the country; and reviewing all that he has seen of

elections, he does say, they are generally conducted in a manner which is

disgraceful to civilised society. The infamy they generate is

equalled by the bungling knavery of their management. He needs not

go into their history, but he would ask a rational man to note the

proceedings of one of these "good old English" events; and then say

whether it were not more like "hell broke loose" than anything human.

Who could wish for annual recurrence of these things throughout the

nation? Frequent enough their visitation when they can no longer be

avoided. General elections annually would be annual curses; and

single borough or county elections are best let alone until there be good

cause. As, in his petition to the House of Commons, in 1837, the

writer would pray that we might have the benefit without the disturbing

force. He would say, let the House of Commons be, like that of the

Lords, indissoluble; members to render an account of their conduct

annually; individual members liable to be displaced by their constituents

at any time, and elected, displaced, or retained, as private servants are,

viz., as they do well their duty, or otherwise. The sense of the

electors to be taken annually—by ballot in districts; all elections to be

by ballot. No hustings, no nomination farce, no mob gatherings, no

ruffianism, no demagogueism, no canting and deception of the multitudes,

nor opportunity for the display of insolence and ignorance to win a

passing clap or huzza. Many evils would be done away with,

excitement would be moderated, sober-mindedness would take the place of

extravagance, Court intrigue or ascendency of faction would not have the

power of dispersing the people's servants, nor of throwing the country

into a ferment of brute passion, to take advantage of it. Such a

plan would the writer substitute for that of annual parliaments, and so

far his opinions have changed on that point.

CHAPTER III.

MEETINGS AT THE CROWN AND ANCHOR TAVERN, LONDON—HENRY HUNT—THOMAS

CLEARY—WILLIAM COBBETT—MAJOR CARTWRIGHT—LORD COCHRANE.

THE Hampden Club of London, of which Sir Francis

Burdett was the chairman, having issued circulars for a meeting of

delegates at the "Crown and Anchor," for the purpose of discussing a Bill

to be presented to the House of Commons, embracing the reform we sought, I

was chosen to represent the Middleton Club on that occasion. I shall

not notice the abuse which this small honour brought upon my shoulders,

further than to say, that it gave me an unexpected insight into the

weakness of some whom I had considered as the best of friends to myself

and the cause. I thus early got a dose of disgust which would have

banished me from amongst them, had I not considered that by retiring I

should abandon my duty and gratify my new enemies. I therefore took

up my cross, forgave them, and attended my appointment in London.

I had scarcely alighted from the coach at the "Elephant and

Castle," ere I was accosted by Benbow, [4] who took me

to his own lodgings near Buckingham Gate, where I became comfortably

settled for the present. He had been in London some time, agitating

the labouring classes at their trades meetings and club-houses. That

night he conducted me to the Crown and Anchor Tavern; and whilst I stood

gazing around a large hall, which seemed wonderfully grand and silent for

a tavern, a gentleman came out of a room and accosted my companion, who

increased my curiosity and awe by pronouncing the name of Mr. Hunt. [5]

He invited us within; and we there found a small party of delegates,

recently arrived, in friendly conversation with Mr. Cleary, the secretary

of the London Club. This was an event in my life. Of Mr. Hunt

I had imbibed a high opinion, and his first appearance did not diminish my

expectations. He was gentlemanly in his manner and attire, six feet

and better in height, and extremely well formed. He was dressed in a

blue lapelled coat, light waistcoat and kerseys, and topped boots; his leg

and foot were about the firmest and neatest I ever saw. He wore his

own hair; it was in moderate quantity and a little grey. His

features were regular, and there was a kind of youthful blandness about

them which, in amicable discussion, gave his face a most agreeable

expression. His lips were delicately thin and receding; but there

was a dumb utterance about them which in all the portraits I have seen of

him was never truly copied. His eyes were blue or light grey—not

very clear nor quick, but rather heavy; except as I afterwards had

opportunities for observing, when he was excited in speaking; at which

times they seemed to distend and protrude; and if he worked himself

furious, as he sometimes would, they became blood-streaked, and almost

started from their sockets. Then it was that the expression of his

lip was to be observed—the kind smile was exchanged for the curl of scorn,

or the curse of indignation. His voice was bellowing; his face

swollen and flushed; his griped hand beat as if it were to pulverise; and

his whole manner gave token of a painful energy, struggling for utterance.

Such was the appearance of Mr. Hunt as I saw him that night,

and on subsequent occasions. His every-day manners, exhibiting the

quality and operations of his mind, will, of necessity, occupy some

portion of the future pages of this work. He was constantly, perhaps

through good but misapplied intentions, placing himself in most arduous

situations. No repose, no tranquillity for him. He was always

beating against a tempest of his own or of others' creating. He had

thus more to sustain than any other man of this day and station, and

should be judged accordingly.

Thomas Cleary, the secretary of the Hampden Club, was also in

the room; he was perhaps twenty-five or twenty-six years of age, about

middle stature, slightly formed, and had a warmth and alacrity in his

manner which created at once respect and confidence. He was, and I

have no doubt is yet, if he be living, worthy of and enjoying the esteem

of all who know him. Hunt ferociously traduced his character at a

subsequent election for Westminster, but the shame recoiled on the

calumniator. Afterwards he attempted to fix upon Cleary the stigma

of being a Government spy, and intimated that he tried about this time to

involve some of the delegates in illegal transactions—a charge as absurd

as it was false.

The day of meeting arrived; Sir Francis Burdett was in the

country, and the worthy old Major Cartwright [6] took

the chair. With a picture of that venerable patriot in my

recollection, let me pause, and render the tribute due to integrity and

benevolence. He was far in years—I should suppose about seventy;

rather above the common stature, straight for his age; thin, pale, and

with an expression of countenance in which firmness and benignity were

most predominant. I see him, as it were, in his long brown surtout

and plain brown wig, walking up the room, and seating himself placidly in

the head seat. A mild smile played on his features, as a

simultaneous cheer burst from the meeting. Cobbett stood near his

right hand. I had not seen him before. Had I met him anywhere

save in that room and on that occasion, I should have taken him for a

gentleman farming his own broad estate. He seemed to have that kind

of self-possession and ease about him, together with a certain bantering

jollity, which are so natural to fast-handed and well-housed lords of the

soil. He was, I should suppose, not less than six feet in height;

portly, with a fresh, clear, and round cheek, and a small grey eye,

twinkling with good-humoured archness. He was dressed in a blue

coat, yellow swansdown waistcoat, drab kersey small clothes, and top

boots. His hair was grey, and his cravat and linen were fine, and

very white. In short, he was the perfect representation of what he

always wished to be—an English gentleman-farmer.

The proceedings of the meeting it is not requisite that I

should go into; they have long been matters of record. The absence

of the baronet was the subject of much observation by the delegates; and

yet, in deference to his wishes, as was understood, a resolution was

introduced and supported by Cobbett, limiting the suffrage to

householders. This was opposed by many, and especially by the

delegates from the manufacturing district; some of whom were surprised

that so important a concession should be made to the opinion of any

individual. Hunt treated the idea with little respect, and I thought

he felt no discomfort at obtaining a sarcastic fling or two at the

baronet. Cobbett advocated the restricted measure, scarcely in

earnest, and weakly, and alleging the impracticability of universal

suffrage. The discussion proceeded for some time and no one grappled

the objection; until, fearing the resolution would be adopted, I in a few

words explained how universal suffrage might be carried into effect, by

taking the voters from the Militia list, or others made on the same plan.

Hunt took up the idea, in a way which I thought rather annoyed Cobbett,

who at length arose, and expressed his conviction of its practicability,

giving me all the merit of his conversion. Resolutions in favour of

universal suffrage and annual parliaments were thereupon carried, and soon

afterwards the meeting was adjourned to the day following. Several

of our country delegates were now presented to Cobbett by Benbow, who

appeared to act almost as master of the ceremonies. I was not

however introduced to the great man, and soon after he left the room.

On the day when Parliament was opened, a number of the

delegates met Hunt at the Golden Cross, Charing Cross, and from thence

went with him in procession to the residence of Lord Cochrane, [7]

in Palace Yard, where a large petition from Bristol, and most of those

from the north of England, were placed in his lordship's hands.

There had been some tumult in the morning; the Prince Regent had been

insulted on his way to the house, and this part of the town was still in a

degree of excitement. We were crowded around, and accompanied by a

great multitude, which at intervals rent the air with shouts. Now it

was that I beheld Hunt in his element. He unrolled the petition,

which was many yards in length, and it was carried on the heads of the

crowd perfectly unharmed. He seemed to know almost every man of

them, and his confidence in, and entire mastery over them, made him quite

at ease. A louder huzza than common was music to him; and when the

questions were asked eagerly, "Who is he?" "What are they about?" and the

reply was, "Hunt! Hunt! huzza!" his gratification was expressed by a stern

smile. He might be likened to the genius of commotion, calling forth

its elements, and controlling them at will. On arriving at Palace

Yard, we were shown into a room below stairs, and whilst Lord Cochrane and

Hunt conversed above, a slight and elegant young lady, dressed in white,

and very interesting, served us with wine. She is, if I am not

misinformed, now Lady Dundonald. At length his lordship came to us.

He was a tall young man; cordial and unaffected in his manner. He

stooped a little, and had somewhat of a sailor's gait in walking; his face

was rather oval; fair naturally, but now tanned and sun-freckled.

His hair was sandy, his whiskers rather small, and of a deeper colour; and

the expression of his countenance was calm and self-possessed. He

took charge of our petitions, and being seated in an armchair, we lifted

him up and bore him on our shoulders across Palace Yard, to the door of

Westminster Hall, the old rafters of which rung with the shouts of the

vast multitude outside.

CHAPTER IV.

SIR FRANCIS BURDETT—VISIT TO KNIGHTSBRIDGE BARRACKSTRADE CLUBS OF

LONDON—PRESTON AND WATSON—SCENE IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS—HENRY BROUGHAM.

ABOUT this time I was formally introduced to Mr.

Cobbett, by Benbow. He received me in a manner which was highly

gratifying to my feelings. This was at his office, or rooms, in

Newcastle Street, Strand. A number of other delegates were present,

but I thought Cobbett gave the preference above all, to our friend Fitton

of Royton; whose sarcastic vein had particularly pleased him. Fitton

had, in a speech at a public meeting, designated a certain class in

Manchester, "The Pigtail Gentry;" a ludicrous idea certainly, and one

which made Cobbett laugh till his sides shook. No man could enjoy a

bit of sarcasm better than he.

A number of us went one morning to visit Sir Francis Burdett

at his house in Park Place. The outside was but of ordinary

appearance; and the inside was not much better, so far as we were

admitted. To me it seemed like a cold, gloomy, barely furnished

house; which I accounted for by supposing that it was perhaps the style of

all great mansions. We were shown into a large room, the only

remarkable thing in which was a bust of John Horne Tooke. Sir

Francis came to us in a loose grey vest coat, which reached far towards

his ankles. He had not a cravat on his neck; his feet were in

slippers; and a pair of white cotton stockings hung in wrinkles on his

long spare legs, which he kept alternately throwing across his knees, and

rubbing down with his hands, as if he suffered, or recently had, some pain

in those limbs. He was a fine-looking man on the whole, of lofty

stature, with a proud but not forbidding carriage of the head. His

manner was dignified and civilly familiar; submitting to rather than

seeking conversation with men of our class. He, however, discussed

with us some points of the intended Bill for Reform candidly and freely,

and concluded with promising to support universal suffrage, though he was

not sanguine of much cooperation in the house. Under these

circumstances we left Sir Francis; approving much that we found in and

about him, and excusing much of what we could not approve. He was

one of our idols, and we were loath to give him up.

Still I could not help my thoughts from reverting to the

simple and homely welcome we received at Lord Cochrane's and contrasting

it with the kind of dreary stateliness of this great mansion and its rich

owner. At the former place we had a brief refection, bestowed with a

grace which captivated our respect, and no health was ever drunk with more

sincere goodwill than was Lord Cochrane's; the little dark-haired and

bright-eyed lady seemed to know it, and to be delighted that it was so.

But here scarcely a servant appeared, and nothing in the shape of

refreshment was seen.

On the afternoon of a Sunday, Mitchell went with me to

endeavour to find a former playfellow of mine, who was now a soldier in

the Foot Guards. He had fought the campaigns of Portugal, Spain, and

France; and we now found him a colour-serjeant at Knightsbridge barracks.

The brave fellow received us with every demonstration of friendship.

I told him what business had brought us to London, and that my fellow

visitor was here on the same errand. Our business made no difference

with him; he brought forth his ration, and we took a hearty lunch, after

which we went with him to the non-commissioned officers' room at the

canteen. About half-a-dozen serjeants were there, to whom my friend

introduced us, making known, without the least reserve, or show of it, the

business we were come upon to the metropolis. That seemed not to

weigh with them, and we were soon in a free conversation on the subject of

parliamentary reform. When objections were stated, they listened

candidly to our replies, and a good-humoured discussion, half serious,

half joking, was promoted on both sides. I and Mitchell had with us,

and it was entirely accidental, a few of Cobbett's Registers, and

Hone's political pamphlets, to which we sometimes appealed, and read

extracts from. The soldiers were delighted; they burst into fits of

laughter; and on the copies we had being given them, one of them read the

Political Litany through, to the further great amusement of himself and

the company. Thus we passed a most agreeable evening, and parted

only at the last hour. Mitchell and I returned to the city; neither

of us, I firmly believe, having any further thought of the circumstance

than to regret that evenings so rationally and so peaceably spent came so

seldom.

Very soon after this a law was passed, making it death to

attempt to seduce a soldier from his duty. Could it possibly be that

the occurrences of this evening led to the enactment of that law?

Several times I attended meetings of trades' clubs, and other

public assemblages of the working men. They would generally be found

in a large room, an elevated seat being placed for the chairman. On

first opening the door, the place seemed dimmed by a suffocating vapour of

tobacco, curling from the cups of long pipes, and issuing from the mouths

of the smokers, in clouds of abominable odour, like nothing in the world

more than one of the unclean fogs of their streets, though the latter were

certainly less offensive and probably less hurtful. Every man would

have his half-pint of porter before him; many would be speaking at once,

and the hum and confusion would be such as gave an idea of there being

more talkers than thinkers, more speakers than listeners. Presently,

"order" would be called, and comparative silence would ensue; a speaker,

stranger or citizen, would be announced with much courtesy and compliment.

"Hear, hear, hear," would follow, with clapping of hands and knocking of

knuckles on the tables till the half-pints danced; then a speech, with

compliments to some brother orator or popular statesman; next a resolution

in favour of parliamentary reform, and a speech to second it; an amendment

on some minor point would follow; a seconding of that; a breach of order

by some individual of warm temperament; half a dozen would rise to set him

right, a dozen to put them down, and the vociferation and gesticulation

would become loud and confounding. The door opens, and two persons

of middle stature enter; the uproar is changed to applause, and a round of

huzzas welcome the new-comers. A stranger like myself inquiring—Who

is he, the foremost and better dressed one?—would be answered, "That

gentleman is Mr. Watson the elder, who was lately charged with high

treason, and is now under bail to answer an indictment for a misdemeanour

in consequence of his connection with the late meeting at Spa Fields."

The person spoken of would be supposed to be about fifty years of age,

with somewhat of a polish in his gait and manner, and a degree of

respectability and neatness in his dress. He was educated for a

genteel profession, that of a surgeon; had practised it, and had in

consequence moved in a sphere higher than his present one. He had

probably a better heart than head; the latter had failed to bear him up in

his station, and the ardour of the former had just before hurried him into

transactions, from the consequences of which he had not yet escaped.

His son at this time was concealed in London, a large reward having been

offered for his apprehension. The other man was Preston, a

co-operator with Watson, Hooper, and others, in late riots. He was

about middle age, of ordinary appearance, dressed as an operative, and

walked with the help of a stick. I could not but entertain a

slightful opinion of the intellect and trustworthiness of these two men,

when, on a morning or two afterwards, at breakfast with me and Mitchell,

they narrated with seeming pride and satisfaction their several parts

during the riots. Preston had mounted a wall of the Tower, and

summoned the guard to surrender. The men gazed at him—laughed; no

one fired a shot—and soon after he fell down, or was pulled off by his

companions, who thought (no doubt) he had acted fool long enough.

Such were two of the most influential leaders of the London

operative reformers. I repeat that I thought meanly of their

qualifications for such a post. But how blind is human perception,

how slow should we be to condemn! I myself was at the same moment

going hand and heart with some who were as little to be depended upon as

the above, and yet I could not perceive my situation. The blind were

then leading the blind.

During the debate on the report of the Green Bag [8]

Committee, I obtained an order for admission to the gallery of the House

of Commons. I well recollect, though I cannot describe, all the

conflicting emotions which arose within me as I approached that assembly,

with the certainty of now seeing and hearing those whom I considered to be

the authors of my country's wrongs. Curiosity certainly held its

share of my feelings; but a strong dislike to the "boroughmonger crew" and

their measures held a far larger share. After a tough struggle at

elbowing and pushing along a passage, up a narrow staircase, and across a

room, I found myself in a small gallery, from whence I looked on a dimly

lighted place below. At the head of the room, or rather den, for

such it appeared to me, sat a person in a full loose robe of, I think,

scarlet and white. Above his head were the royal arms, richly

gilded; at his feet several men in robes and wigs were writing at a large

table, on which lamps were burning, which cast a softened light on a rich

ornament like a ponderous sceptre of silver and gold, or what appeared to

be so. Those persons I knew must be the Speaker and the clerks of

the House; and that rich ornament could be nothing else than the

"mace"—the same thing, or one in its place, to which Cromwell pointed and

said, "Take away that bauble; for shame—give way to honester men."

On each side of this pit-looking place, leaving an open space in the

centre of the floor, were some three or four hundreds of the most

ordinary-looking men I had ever beheld at one view. Some were

striking exceptions; several young fellows in military dresses gave relief

to the sombre drapery of the others. Canning, with his smooth, bare,

and capacious forehead, sat there, a spirit beaming in his looks like that

of the leopard waiting to spring upon its prey. Castlereagh, with

his handsome but immovable features; Burdett, with his head carried back,

and held high as in defiance; and Brougham, with his Arab soul ready to

rush forth and challenge war to all comers. The question was to me

solemnly interesting, whilst the spectacle wrought strangely on my

feelings. Our accusers were many and powerful, with words at will,

and applauding listeners. Our friends were few and far between, with

no applauders save their good conscience, and the blessings of the poor.

What a scene was this to be enacted by the "collective wisdom of the

nation." Some of the members stood leaning against pillars, with

their hats cocked awry; some were whispering by half-dozens; others were

lolling upon their seats; some, with arms a-kimbo, were eye-glassing

across the house; some were stiffened immovably by starch, or pride, or

both; one was speaking, or appeared to be so, by the motion of his arms,

which he shook in token of defiance, when his voice was drowned by a howl

as wild and remorseless as that from a kennel of hounds at feeding time.

Now he points, menacing, to the ministerial benches—now he appeals to some

members on this side—then to the Speaker; all in vain. At times he

is heard in the pauses of that wild hubbub, but again he is borne down by

the yell which awakes on all sides around him. Some talked aloud;

some whinnied in mock laughter, coming, like that of the damned, from

bitter hearts. Some called "order, order," some "question,

question;" some beat time with the heel of their boots; some snorted into

their napkins; and one old gentleman in the side gallery actually coughed

himself from a mock cough into a real one, and could not stop until he was

almost black in the face.

And are these, thought I, the beings whose laws we must obey?

This the "most illustrious assembly of freemen in the world?" Perish

freedom then, and her children too. O! for the stamp of stern old

Oliver on this floor; and the clank of his scabbard, and the rush of his

iron-armed band, and his voice to arise above this babel howl—"Take away

that bauble"—"Begone; give place to honester men."

Such was my first view of the House of Commons; and such the

impressions strongly forced on my feelings at the time. The speaker

alluded to was Henry Brougham. I heard at first very little of what

he said, but I understood from occasional words, and the remarks of some

whom I took for reporters, that he was violently attacking the ministers

and their whole home policy. That he was so doing might have been

inferred from the great exertions of the ministerial party to render him

inaudible, and to subdue his spirit by a bewildering and contemptuous

disapprobation. But they had before them a wrong one for being

silenced, either by confusion or menace. Like a brave stag, he held

them at bay, and even hurled back their defiance with "retorted scorn."

In some time his words became more audible; presently there was

comparative silence, and I soon understood that he had let go the

ministry, and now, unaccountable as it seemed to me, had made a dead set

at the reformers. Oh! how he did scowl towards us—contemn and

disparage our best actions and wound our dearest feelings! Now

stealing near our hearts with words of wonderful power, flashing with

bright wit and happy thought; anon like a reckless wizard changing

pleasant sunbeams into clouds, "rough with black winds and storms," and

vivid with the cruellest shafts. Then was he listened to as if not a

pulse moved; then was he applauded to the very welkin. And he stood

in the pride of his power, his foes before him subdued, but spared; his

friends derided and disclaimed, and his former principles sacrificed to

"low ambition," and the vanity of such a display as this.

I would have here essayed somewhat with respect to Canning,

and the character and effects of his eloquence; but little appertaining to

him remained on my mind. Every feeling was absorbed by the

contemplation of that man whom I now considered to be the most perfidious

of his race. I turned from the spectacle with disgust, and sought my

lodgings in a kind of stupor, almost believing that I had escaped from a

monstrous dream.

Such was my first view of Henry Brougham; and such the

impressions I imbibed and long entertained of that extraordinary man.

He sinned then, and has often done so since, against the best interests of

his country; bowing to his own image, and sacrificing reason and principle

to caprice or offended self-love. But has he not done much for

mercy, and for the enlightenment of his kind? See the African

dancing above his chains! Behold the mild but irresistible light

which education is diffusing over the land! These are indeed

blessings beyond all price—rays of unfading glory. They are Lord

Brougham's; and will illumine his tomb when his errors and imperfections

are forgotten.

CHAPTER V.

HABEAS CORPUS ACT SUSPENDED-BLANKET MEETING AT MANCHESTER—MARCH AND

DISPERSION OF THE BLANKETEERS -TREASONABLE PLOT—JOSEPH HEALEY, THE DOCTOR;

HIS OBSERVATIONS AND DISCOVERIES IN THE WELKIN.

SOON afterwards I left the great Babylon, heartily

tired of it, and returned to Middleton, where events rapidly pressed on my

attention.

On the morning of Sunday, the 8th of March, Benbow called on

me at Middleton. I had lost sight of him since my return from

London; the Habeas Corpus Act was already suspended, and I supposed from

some remarks of his that he had thought it best not to be so much in

public at Manchester as he previously had been. He had, however,

taken a great share in getting up and arranging the Blanket Meeting; and

now, after commending the intended proceeding, and dwelling on the good

effects it would produce, he asked me to join in the meeting and

expedition, and to bring as many of my neighbours as I could. I

flatly refused; and stated my reasons, which will shortly appear. He

enlarged his commendations, calculating with certainty that the

Blanketeers would march to London, thousands in number; and that their

petitions would be graciously, if not with some awe, received by the

Prince Regent in person. I maintained my opinions—he answered with

reproaches; I treated the plan as a chimera, and held lightly the judgment

of its proposers and concoctors. Benbow went away in a huff, and I

remained with a lowered opinion of my former comrade.

On the night of Sunday, the 9th of March, I was requested to

attend a meeting in the house of one of my neighbours, where a number of

friends wished to hear my opinion with reference to the Blanket Meeting.

I went to them and spoke freely in condemnation of the measure. I

endeavoured to show them that the authorities of Manchester were not

likely to permit their leaving the town in a body, with blankets and

petitions, as they proposed; that they could not subsist on the road; that

the cold and wet would kill numbers of them, who were already enfeebled by

hunger and other deprivations; that soldiers always marched in divisions

for the easier procurement of food and lodgings; and that an irregular

multitude like themselves, could not, on an emergency, be provisioned, and

quartered. That they need not expect to be welcome wherever they

went, especially in such of the rotten boroughs as fell in their way,

against the franchise of which they were petitioning; that the inhabitants

would bolt their doors against them; and that if they took possession by

force; there was the law to punish them. That many persons might

join their ranks who were not reformers but enemies to reform, hired

perhaps to bring them and their cause into disgrace; that, if these

persons began to plunder on the road, the punishment and disgrace would be

visited on the whole body; that they would be denounced as robbers and

rebels, and the military would be brought to cut them down or take them

prisoners. In conclusion, I earnestly cautioned them against having

anything to do with the proposed meeting, and intimated that the parties

who had got it up were not to be depended upon; that their blind zeal

overran every reasonable consideration; and that if they, my neighbours,

took part in the meeting, they would probably repent when it was too late.

Whether it was in consequence of what I said I cannot tell; but I was

afterwards gratified on hearing that no person from Middleton went as a

Blanketeer.

But of this meeting, which was our first great absurdity, I

must write more particularly.

It was one of the bad schemes which accompanied us from

London, and was the result of the intercourse of some of the deputies with

the leaders of the London operatives—the Watsons, Prestons, and Hoopers.

Mitchell and Benbow had cultivated, rather close acquaintance, with these

men, little suspecting, I have no doubt, that their new friends had

already fallen under the influence of instigators who betrayed all their

transactions to the Government. But the London leaders, or at least

such of them as I conversed with, were, as I have shown, men of frank

character and bearing, and apparently of sincere intention; and their

manner, flattering by the confidence it bestowed, naturally led to a

reciprocal feeling, and to the formation of connections, the effects of

which now began to appear.

Our maxim had hitherto in all our proceedings been "Hold fast

by the laws." It was the maxim of Major Cartwright, our venerable

political father, and had been adhered to with a religious observance.

But doctrines varying from this now began to be broached, and measures

hinted, which, if not in direct contravention of the law, were but

ill-disguised subterfuges for evading its intentions.

The meeting took place according to appointment; but I not

being there, my brief description must be taken as the account of others.

The assemblage consisted almost entirely of operatives, four or five

thousand in number; and was held on that piece of ground (St. Peter's

Field) which afterwards obtained so melancholy a celebrity. Many of

the individuals were observed to have blankets, rugs, or large coats,

rolled up and tied, knapsack like, on their backs; some carried bundles

under their arms; some had papers, supposed to be petitions rolled up; and

some had stout walking sticks. The magistrates came upon the field

and read the Riot Act; the meeting was afterwards dispersed by the

military and special constables, and twenty-nine persons were apprehended,

amongst whom were two young men, named Bagguley and Drummond, who had

recently come into notice as speakers, and who being in favour of extreme

measures, were much listened to and applauded. But my warm friend,

Benbow, took care not to make his appearance on that occasion.

On the Riot Act being read, about three hundred persons left

the meeting to commence their march to London. Some of them formed a

straggling line in Mosley Street, and marched along Piccadilly, being

continually joined by others, until the whole body was collected, near

Ardwick Green. The appearance of these misdirected people was

calculated to excite in considerate minds pity rather than resentment.

Some appeared to have strength in their limbs and pleasure in their

features, others already with doubt in their looks and hesitation in their

steps. A few were decently clothed and well appointed for the

journey; many were covered only by rags which admitted the cold wind, and

were already damped by a gentle but chilling rain. Some appeared

young, with health on their cheeks, every care behind and hope alone

before; the thoughts of others were probably reverting to their homes on

the hill-sides, or in the sombre alleys of the town, where wives and

children had resigned them for a time, in hopes of their return with

plenty, and never more to part. Here a youth was waving his hand to

a damsel pale and tremulous with alarm; yonder an attenuated being, giving

back, after kissing it, a poorly child to the arms of its mother—he

hastens towards his comrades with willing but feeble steps, looking back

on those, so poor, but oh! how dear—the child is hushed with a caress, the

mother turning it gently to her cold and nurtureless bosom, nurtureless of

everything save deep and tender love. Her looks are still directed

the way he goes; he has disappeared: and whilst her tears flow the poor

but cleanly mantle is drawn over the little one, and in a conflict of

grief, hope, and fear, she thoughtfully wends to her obscure and cheerless

abode. A body of yeomanry soon afterwards followed those

simple-minded men, and took possession of the bridge at Stockport.

Many then turned back to their homes; a body of them crossed the river

below, and entered Cheshire; several received sabre wounds, and one man

was shot dead on Lancashire hill. Of those who persisted in their

march it is only necessary to say that they arrived at nine o'clock at

night in the market place at Macclesfield, being about one hundred and

eighty in number. Some of them lay out all night, and took the

earliest dawn to find their way home. Some were well lodged and

hospitably entertained by friends; some paid for quarters, and some were

quartered in prison. Few were those who marched the following

morning. About a score arrived at Leek, and six only were known to

pass Ashborne bridge. And so ended the Blanket Expedition!

"What would you really have done," I said to one of them, "supposing you

had got to London?" "Done?" he replied, in surprise at the question;

"why iv wee'd nobbo gett'n to Lunnun, we shud ha' tan th' nation, an'

sattl't o'th dett." Such, and about as rational, were some of the

incoherent dreams which at this time began to find favour in the eyes of

the gross multitude.

But another cause was assigned for the dispersion of the

Blanketeers. It was said that a purse containing from thirty to

fifty pounds having been made up, was given to one of the principal

leaders, with instructions to proceed on the London road a day or two in

advance, to procure food and lodgings for money, where they could not be

had for friendship or a more urgent motive. That "the good man," by

some mistake, got out of the right way, and wandering far into Yorkshire,

he never found himself till the money was all spent; and the Blanketeers,

thus losing their commissary and paymaster, were broken by the same means

which had dispersed more numerous armies, viz., want of necessaries; and

thus "the nation" was saved for that time. However true or otherwise

this account may be, it is certain that the man suddenly disappeared (but

others did the same) and was out of the way a month or two, after which he

paid a visit to Middleton on his return, as he said, from Yorkshire to

Manchester. He was always somewhat doubted afterwards; and his last

appearance in this quarter was in the character of an adroit crimp to a

fortune-promising attorney.

It was about this time, though I have not the exact date,

that the first out-of-door meeting was held at Rochdale. Fitton,

Knight, myself, and several other public characters were invited to

attend, and I did so. The day was cold and very wet; the hustings

were fixed on the bare moor of Cronkeyshaw. None of the speakers

save myself kept their appointment; nothing in the form of resolution or

petition had been prepared, and I had to select and arrange these from an

old "Statesman" newspaper which I found at the rendezvous, the "Rose," in

Yorkshire Street. The town wore an appearance of alarm, and a

company or two of soldiers were under arms in the main street. The

meeting was, however, well attended, and the hearts of the people seemed

to warm in proportion to the merciless cold of the wind and rain, which

latter teemed upon us during the whole of the proceedings. On our

return, the poor redcoats were still carrying arms, though, as one of the

woollen weavers remarked, it would be to little purpose should they be

wanted, "as the water was already running over at the muzzles of their

guns; they might squirt us," he said, "but could not shoot us." On

this occasion I received pay for my attendance. On our return to the

"Rose," besides refreshments, the Committee presented me with four

shillings, and I accepted the money because I thought I was entitled to

it, having lost work to that value at home. But I never, except on

this occasion, took money or any other remuneration for attending reform

meetings. I considered it a mean thing, though the practice was

coming much into use, and several of my friends, without any scruple,

continued to do so until "their occupation" was gone. It was a bad

practice, however, and gave rise to a set of orators who made a trade of

speechifying, and the race has not become extinct. These persons

began to seek engagements of the kind; some would even thrust themselves

upon the committee for remuneration, and generally received it. He

who produced the greatest excitement, the loudest cheering, and the most

violent clappings, was the best orator, and was sure to be engaged and

well paid, and in order to produce those manifestations, the wildest and

most extravagant rhodomontade would too often suffice. Such speakers

quickly got a name; the calls on them were frequent; and they left their

work or their business for a more profitable and flattering employment;

tramping from place to place hawking their new fangles, and guzzling,

fattening, and replenishing themselves at the expense of the simple and

credulous multitude. Steadiness of conduct and consistency of

principle were soon placed as it were at a distance from us. Our

unity of action was relaxed; new speakers sprung like mushrooms about our

feet; plans were broached, quite different from any that had been

recognised by the Hampden Clubs; and the people, at a loss to distinguish

friends from enemies, were soon prepared for the operations of informers,

who, in the natural career of their business, became also promoters of

secret plots and criminal measures of various descriptions. The good

and fatherly maxim of the worthy old major, "Hold fast by the laws," was

by many lost sight of.

How far the moral of these facts is applicable to the present

day will be judged by an observant public, and may perhaps not be deemed

ill-timed by some of the more intelligent of those who have been found

amongst the persons styled Chartists. If from the records of past

errors good can be extracted for present emergencies, it will be well, and

let us endeavour to do so. History is a faithful monitor, requiring

only to be consulted in a truth-seeking spirit, when she will vouchsafe to

become a friendly counsellor, saying to her inquirer, "Come blind one and

see; come lost one, and behold thy way." Nations may read their fate

in the histories of nations; and individuals may be advised by a memoir so

humble as mine.

At dusk on the evening of Tuesday, the 11th of March, the day

after the Blanket meeting, a man dressed much like a dyer was brought to

my residence by Joseph Healey, who had found him inquiring for me in the

lower part of the town. The stranger said he had something of a

private and important nature to communicate, in consequence of which I and

the stranger and Healey went to the sign of the "Trumpeter," where we were

accommodated with a private room. The man now told us that he was

deputed by some persons at Manchester to propose that in consequence of

the treatment which the Blanketeers had received at the meeting and

afterwards, "a Moscow of Manchester" should take place that very night.

The man paused and looked at us severally. I intimated that I knew

what he meant, and desired him to go on. He said it would entirely

depend on the co-operation or otherwise of the country people; that other

messengers had been sent to every reform society within twenty miles of

the town; that if the answers were favourable to the project, the light of

the conflagration was to be the signal for the country people to come

in—and, in such case, the Middleton people were requested to take their

station on St. George's Field. He said the plan had been arranged by

a meeting held at Manchester; that the whole force would be divided into

parties, one of which was to engage the attention of the military and draw

them from their barracks; another was to take possession of the barracks

and secure the arms and magazine; another was to plunder and then set fire

to the houses of individuals who were marked out; and a fourth was to

storm the New Bailey and liberate the prisoners, particularly the

Blanketeers confined there. I said it was a serious thing to

undertake, and that an answer could not be returned from Middleton until

some friends had been consulted. On my rising to go out, the man

appeared alarmed, and begged I would not betray him. I assured him

he had nothing to fear, and desired him to stay with Healey until my

return, which would be very soon, on which he seemed reconciled to my

going. I speedily went to five of my acquaintance, chiefly members

of the committee, and desired them to repair immediately to Healey's

house, where business of importance would be laid before them. I

then brought up the stranger and the doctor, and telling the man he might

confide in us, he repeated nearly word for word what he had said at the

"Trumpeter." I then said I would have nothing to do with the scheme;

that it was unlawful, inhuman, and cowardly. I told him he appeared

to be a simple young fellow, and was probably the dupe of some designing

villain. My friends agreed with my opinion, both as to the proposal

and the instrument who broached it: we bade him, however, not to mistrust

us; gave him refreshment, and sent him away, more in sorrow for his peril

(being persuaded he was in the hands of villains) than of resentment for

the decoy he had attempted. We bade him good night, and he went his

way.

The young man said his name was Samuel Priestley; I observed

that he had lost a finger from his left hand; he said he lived at Bank

Top, Manchester. I afterwards made inquiries respecting him on the

spot, but never could hear of such a person in the place or neighbourhood.

This statement, however, cannot now injure him.

After he was gone we consulted about this strange message and

unknown messenger. We had not heard of the plot before, and though

we doubted not that it had been sanctioned, as the man stated, by the

Manchester committee, that circumstance did not increase our confidence.

We had no reliance on their sagacity or their integrity as a body; men who

could get up and countenance the Blanket Expedition had no weight with us.

They were moreover reported to be under the influence of spies from the

police; a suspicion which many circumstances tended to strengthen.

The plot itself did the same; the unknown messenger, the precipitation,

"to be done that very night," the population for twenty miles around an

immense town to be brought upon it by midnight, and then to be divided,

apportioned, and set to work by men of whom they knew nothing! The

proposal was too absurd, as well as iniquitous, to excite anything save

wonder and disgust, even with simple and inexperienced ones like

ourselves. Besides, would Major Cartwright have sanctioned such a

measure? Certainly not. And then we almost regretted that we

had suffered the emissary to depart.

It was deemed prudent that Healey and I should on that night

sleep from home, and at some place where our stay could be proved, should

anything arise to render such a step necessary; and none could tell what

might be necessary, as in those days of alarm and uncertainty no one knew

what was impending. An old female reformer accordingly gave us her

house and bed, and turning the key, locked us in, whilst we, in our

simplicity, were quite satisfied with having taken so wise a precaution

against any false evidence which might by possibility be brought to

connect us with the plot of which we had been apprised. We retired

to rest and lay talking this strange matter over until sleep overtook us.

I was first to awake, and seeing a brightness behind the curtain, I

stepped to the window, and sure enough beheld in the southern sky a stream

of light which I thought must be that of a distant lire. It was a

fine crisped morning, and as I looked, a piece of a moon came wandering to

the west from behind some masses of cloud. Now she would be entirely

obscured; then streaks of her pale beams would be seen breaking on the

edges of the vapours; then a broader gleam would come; then again it would

be pale and receding; but the clouds were so connected that the fair

traveller had seldom a space for showing her unveiled horn. I saw how it

was; my conflagration had dwindled to a moonbeam, and as I stood with the

frost tingling at my toes "an unlucky thought" (as we say, when excusing

our own sins we impute them to a much abused sable personage) came into my

head to have a small joke at the doctor's expense; and as it was a mode of

amusement to which I must confess I was rather prone, I immediately began

to carry it into effect. I gave a loud cough or two; the doctor

thereupon grunted and turned over in bed; when, in the very break of his

sleep, I said aloud, as I crept beneath the bedclothes, "there's a fine

leet i'th' welkin, as th' witch o' Brandwood sed when the devil wur ridin'

o'er Rossenda." "Leet," said the doctor; "a fine leet, weer? weer?"

"Why go to th' windo' an' look." That instant my sanguine friend was

out of bed and at the window, his head stuck behind the curtain.

"There's a great leet," he said, "to'rd Manchester." "There is

indeed," I replied, "it's mitch but weary wark is gooin' on omung yon foke."

"It's awful," said the doctor; " thei'r agate as sure as we're heer."

"I think there's summut up," I said. I was now snugly rolled in the

clothes, and perceived at the same time that the doctor was getting into a

kind of dancing shiver, and my object being to keep him in his shirt till

he was cooled and undeceived, and consequently a little sprung in temper,

I asked, "Dun yo really think then ot th' teawn's o' foyer?"

"Foyer," he replied; "there's no deawt on't." "Con yo see th'

flames, doctor?" "Nowe, I conno' see th' flames, but Icon see th'

leet ut coms fro' em." "That's awful," I ejaculated. "Aye,

it's awful," he said; "come an' see for yo'rsel'." "Nowe, I'd

reyther not," I answered; "I dunno' like sich sects; it's lucky ut we're

heer—they conno' say ut we'n had owt to do wi' it, at ony rate, con they,

doctor?" "Nowe," he said, "they conno'. It keeps changin'," he

said. "Con yo' yer owt?" I asked. "Nowe, I conno' yer nowt,"

he said. I, however, heard his teeth hacking in his head, and

stuffed the sheet into my mouth to prevent my laughter from being noticed.

"Ar' yo' sure, doctor?" I asked. No reply. "Is it blazin' up?"

I said. "Blazin' be hanged!" was the answer. "Wet dun yo' myen,

doctor—is it gwon eawt then?" "Gullook!" he said, "it's nobbut th'

moon, an' yo' knewn it oth' while." A loud burst of laughter

followed, which I enjoyed till the bed shook; my companion muttering

imprecations and sundry devil's prayers against all "moon doggs an' welkin

lookers," by which terms I knew he meant myself for one.

CHAPTER VI.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE SUSPENSION OF THE HABEAS CORPUS—STATE OF THE

COUNTRY—STOPPAGE OF PUBLIC MEETINGS—SECRET ONES COMMENCED.

PERSONAL liberty not being now secure from one hour

to another, many of the leading reformers were induced to quit their

homes, and seek concealment where they could obtain it. Those who

could muster a few pounds, or who had friends to give them a frugal

welcome, or who had trades with which they could travel, disappeared like

swallows at the close of summer, no one knew whither. The single men

stayed away altogether; the married ones would occasionally steal back at

night to their wan-cheeked families, perhaps to divide with them some

trifle they had saved during their absence, perhaps to obtain a change of

linen or other garment for future concealment, but most of all, as would

naturally be the case, to console, and be consoled by their wives and

little ones. Perhaps one had found an asylum amongst kind friends,

and had brought home a little hoard, the fruits of his own industry and

carefulness, or of their generosity. Perhaps he had been wandering

in want, not daring to make himself known, until his beard disguised him,

his shoes and stockings were trampled from his feet, and his linen was in

rags; when at length, worn out and reckless, he would venture home, like

the wearied bird which found no place to rest. Perhaps he had been

discovered to be a reform leader, and had been threatened, mayhap pursued,

and, like a hunted hare, now returned to the place of former repose.

Then he would come home stealthily under cover of darkness; his wife would

rush into his arms, his little ones would be about his knees, looking

silent pleasure —for they, poor things, like nestling birds, had learned

to be mute in danger.

But with all precautions, it did sometimes happen that in

such moments of mournful joy the father would be seized, chained, and torn

from his family before he had time to bless them or to receive their

blessings and tears. Such scenes were of frequent occurrence, and

have thrown a melancholy retrospection over those days. Private

revenge or political differences were gratified by secret and often false

information handed to the police. The country was distracted by

rumours of treasonable discoveries, and apprehensions of the traitors,

whose fate was generally predicted to be death or perpetual imprisonment.

Bagguley, Johnson, Drummond, and Benbow were already in prison at London;

and it was frequently intimated to me, through some very kind

relations-in-law, that I and some of my acquaintances would soon be

arrested. This sort of information was always brought to Middleton

by parties who, being in the manufacturing line, visited Manchester twice

or thrice a week for the purpose of disposing of their goods. They

appeared to be well acquainted with the movements of the police; they

could tell when king's messengers arrived or departed; how many State

warrants had been issued; who would be next apprehended; and such like

useful and pleasant things, which they always took care to make known in

such quarters as made it sure to reach those they wished to render unhappy

by anticipation of troubles they could not now avoid. And, strange

to say, many of their predictions were verified. King's messengers

did arrive: Government warrants were issued; and the persons they

mentioned were taken to prison. A cloud of gloom and mistrust hung

over the whole country. The suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act was

a measure the result of which we young reformers could not judge, save by

report, and that was of a nature to cause anxiety in the most indifferent

of us. The proscriptions, imprisonments, trials, and banishments of

1792 were brought to our recollections by the similarity of our situation

to those of the sufferers of that period. It seemed as if the sun of

freedom were gone down, and a rayless expanse of oppression had finally

closed over us. Cobbett, in terror of imprisonment, had fled to

America; Sir Francis Burdett had enough to do in keeping his own arms

free; Lord Cochrane was threatened, but quailed not; Hunt was still

somewhat turbulent, but he was powerless, for he had lost the genius of

his influence when he lost Cobbett, [9] and was now

almost like Sampson, shorn and blind. The worthy old Major remained

at his post, brave as a lion, serene as an unconscious child; and also, in

the rush and tumult of that time, almost as little noticed. Then, of

our country reformers, John Knight had disappeared; Pilkington was out of

the way somewhere; Bradbury had not yet been heard of; Mitchell moved in a

sphere of his own, the extent of which no man knew save himself; and Kay

and Fitton were seldom visible beyond the circle of their own village;

whilst, to complete our misfortunes, our chapel-keeper, in the very tremor

of fear, turned the key upon us, and declared we should no longer meet in

the place.

Our society, thus hopeless, became divided and dismayed;

hundreds slunk home to their looms, nor dared to come out, save like owls

at nightfall, when they would perhaps steal through by-paths or behind

hedges, or down some clough, to hear the news at the next cottage.

Some might be seen chatting with and making themselves agreeable to our

declared enemies; but these were few, and always of the worst character.

Open meetings thus being suspended, secret ones ensued; they were

originated at Manchester, and assembled under various pretexts.

Sometimes they were termed "benefit societies," sometimes "botanical

meetings," "meetings for the relief of the families of imprisoned

reformers," or "of those who had fled the country"; but their real

purpose, divulged only to the initiated, was to carry into effect the

night attack on Manchester, the attempt at which had before failed for

want of arrangement and co-operation.

CHAPTER VII.

SEARCH FOR A TEMPORARY HOME—DOCTOR HEALEY'S PATERNITY—SOME ACCOUNT OF

HIMSELF—A GLANCE AT THE AUTHOR'S ANCESTRY—HEALEY'S UNCLE RICHARD, HIS

HOUSE AND FAMILY—VIEW FROM KNOWE HILL.

WEARIED at length with the continued alarms of my

intended arrest and committal to prison, I consented to leave home for a

day or two to find some place where, unknown, I might earn a subsistence

until the cloud was blown over, and I could return in safety.

Healey, who also had expectations of being wanted shortly, determined to

accompany me with a like view; and so, in the thick, grey morning, with

light purses and somewhat heavy hearts, we left our humble but dear homes,

and struck into the open country

|

"Down a quiet green lane where two rindles flow;

Unto lands where the night-hunters stealthily go;

Cross'd Roche's dark stream; o'er a barren heath hied;

And up to the moorlands wild and wide." |

Healey wished to see his uncle Richard, who was a farmer and publican on

the moors to the north-west of Middleton; and soon, as the sun broke out

and the mist cleared, we found ourselves traversing Hopwood Ley in that

direction. How delicious was the air, wafting breezy and free over

the budding woods! Now sweeping up the hollows, now coming through

the dew pearls and shaking the hazel bloom, now bearing towards us the

bold note of the throstle, anon receding to nestle softly in the dingles

with the melody of the blackbird! How happy were those simple

children of nature—happy in their loves, in their rude nests; in their

offspring, and in their unconsciousness of danger. The lapwing's

plaintive cry as it wheeled above was in unison with our feelings; the

bird also seemed, like ourselves, to have no resting-place; whilst the

cony, frisking before us, and disappearing, showed us he had a home.

But the bracing air, the warm, life-giving sun, the glorious beings of

nature around and above us, whilst they excited our attention, gradually

dispelled the gloom of our feelings, and we also began to be cheerful if

not happy, remembering that there is no hill without its vale, no storm

without its calm, no shadow without its sun. So we went on—now

climbing a hedge, now leaping a rindle, now starting a hare, or springing

a woodcock, now treading a bit of swamp, now up a knoll through the

gorses, then by the skirt of a meadow, and round to the hill-foot, by the

music of a stream, where—

|

"Spring moves on as glad we gaze,

Calling the flowers wherever she strays.

Come from the earth, ye dwellers there,

To the blessed light, and the living air:

For the snowdrop hath warned the drift away;

And the crocus awaiteth your company;

And the bud of the thorn is beginning to swell;

And the waters have broken their bonds in the dell.

And are not the hazel and slender bine

Blending their boughs where the sun doth shine?

And the willow is bringing its downy palm,

Garland for days that are bright and calm;

And the lady-flower waves on its slender stem;

And the primrose peeps like a starry gem." |

Thus tramping o'er Spinthreeds and the Wilderness, we approached Captain

Fold, the sight of which led Healey into some remarks on his father, his

family, and his own early days.

He said he was born at Captain Fold, where his father lived

and was a famous cow-leech, being fetched by the farmers to all parts of

the country when their cattle were sick; that he also dabbled a little in

medicines for the human frame, and was successful in most of the cases

which he undertook; and they were such as had baffled common applications.

That his father was a devout man of the Methodist persuasion, and a firm

believer in witches and witchcraft, which persuasion he also inherited.

That in those days there were many sudden and uncommon disorders, which

few persons understood, and fewer still could cope with. Such were

often treated by his father on the "supernatural plan," and he was

generally successful. He was almost sure to be sent for when cattle

were supposed to be amiss from the influence of infernal spells, which he

counteracted sometimes by other spells, drugs and herbs prepared at

particular seasons, and under certain forms and ceremonials. He had

also great faith in the power of faith, and the efficacy of private

prayer. He died, however, leaving my companion unprovided for, and

he was put apprentice to a cotton weaver at Bolton, where he learned the

business, but under such oppressions and cruelties from his master and

dame, as instilled into him a thorough abhorrence of tyranny. At the

expiration of the term of his bondage he came to Chadderton, where he had

a married sister living; and after introducing a new method of

twisting-in-warps, by which he saved a little money, and clothed himself

respectably, he paid his addresses to his present wife and was accepted,

and came to Middleton to reside with his wife and her parents. He

accounted for his getting into the surgical profession by supposing that

he derived a taste for it from his father. He first began by selling

simple drugs; after which he got some books, and ventured to compound and

prescribe medicines. Next he succeeded in "breathing a vein"; and

lastly became a tooth-drawer, and general practitioner of the surgical

art; and now "he was thankful, he needed not turn his back on any of his

neighbours in the same line." There was only one point he said, and

that was the art obstetric, in which he was deficient; and he hoped to

attain that yet. Such were my companion's past trials and present

attainments. In sketching his father, however, he omitted one

remarkable circumstance, and if he knew it, honour be to his filial regard

for the omission; it accords, however, very closely with the son's outline

of the remarkable old man. It was said that so firm was his belief

in the human application of divine faith, and such his assurance of being

perfected in it, that he ascended the ridge of his barn, in the presence

of his assembled neighbours, and after praying for, and exhorting them,

he, in the full expectation of being buoyed tip, flung himself off, and

fell souse on a dung-heap below. Such a misdirection was, of course,

a great handle to the ungodly; but in the old man's opinion it was no

disproof of the power of faith, but an intimation only of his own weakness

and imperfections in that divine attainment.

Doctor Healey, or, "the doctor," as we must now call him, was

about five feet six in height; thirty-two or three years of age, with

rather good features, small light grey eyes, darker whiskers and hair,

with a curl on his forehead, of which he was remarkably proud. He

was well-set in body, but light of limb; his knees had an uncommonly

supple motion, which gave them an appearance of weakness. He had an

assured look, and in walking, especially when with a little "too much wind

in the sheet," he turned his toes inward, and carried an air of bravado

which was richly grotesque. In disposition he was, until afterwards

corrupted, generous and confiding; credulous, proud of his person and

acquirements. A book-buyer, but little of a reader, less of a

thinker, and no recollector of literary matters. Hence, with an

imperturbable self-complacency, he was supremely oblivious of the world,

its history, manners, and concerns; except such as directly interfered

with the good or evil of his own existence. At this time his attire

was scarcely more decent than my own; both were somewhat too seedy, but

that was a circumstance on which a learned doctor and a self-devoting

patriot could look with indifference.

His hat was somewhat napless, with sundry dinges on the

crown, and up-settings and down-flappings of the brim, which showed it to

have tupped against harder substances than itself, as well as to have seen

much "winter and rough weather." He wore a long drab top-coat,

which, from its present appearance, might never have gone through the

process of perching. His under-coat was of dark uncut fustian,

which, by his almost incessant occupation in the "laboratory," preparing

ointments, salves, and lotions, had become smooth and shining as a duck's

wing, and almost as impervious to wet; his hamsters were similar in

material and condition to his coat, whilst his legs were encased in

top-boots, no worse for wear, except perhaps a leaky seam or two, and a

cracked upper leather. Such was one who will have frequently to make

his appearance in this work. He had within him at this time, no

doubt, the germs of many faults which might not have appeared at all, had

he not been thrown into connections which perverted his naturally simple,

inoffensive, and even amiable nature.