|

THE DISTRESS IN THE COTTON-MANUFACTURING

DISTRICTS.

THE poor-law returns for the second week of November

show an increase of 10,290 persons relieved in the Lancashire Unions, or

253,640 persons in all. The Poor-law Board have authorised the

guardians of Preston and Blackburn to borrow money under the provisions of

the Union Relief Aid Act. The guardians of Preston are authorised to

borrow £3517 0s. 1¾d., and the guardians

of Blackburn £3330. A large quantity of clothing arrived at Preston

during the past week, and the distribution of bedding and clothing among

the poor unemployed operatives has been made; and their expressions of

gratitude have even overwhelmed those who have superintended the

distribution with tears, in common with tears of thankfulness from

themselves. Some particulars by our own reporter, of the state of

things in Manchester will be found in another column.

At the weekly meeting of the Mansion House Committee yesterday week the

financial statement was read, showing that the contributions during the

week amounted to upwards of £35,000. Among the contributions received were

some additional ones from India, and a collection from the Greek church in

London-wall amounting to £1400. The whole sum received since the committee

was formed amounts to nearly £174,000. The committee sat for some time

deliberating on the various applications made to them for relief. They

distributed altogether nearly £39,000 among eighty different towns and

villages, in sums varying, according to the necessities of the case, from

£3000 to £50. Success beyond expectation has attended the plan of

collecting clothing. The report from the depot at Bridewell showed the

number of bales and parcels of clothing, &c., received there up to

Thursday night to be 2400. Besides cast-off clothes, amazing quantities of

blankets, flannel, linsey, and the like, have been delivered at the depot

from time to time.

A highly influential meeting was held on Monday in Cork for the purpose of

assisting in the relief, and at the close of the meeting subscriptions

were handed in amounting to upwards of £1120. Yesterday week a public

meeting was held in Wolverhampton, which was attended by the leading

ironmasters, manufacturers, and landed proprietors in that town and the

immediate district. Resolutions were passed to canvass the town, and £1562

was promised in the room―£1000 being put down in cash or cheques. At a

town meeting held at Wigan, on Wednesday week, a subscription-list (the

third) was announced of £7152. Amongst these was the Earl of Crawford

(£100 a week for five months), £2000; Messrs. Thomas Taylor and Brothers

(£800 now and £200 a month for six months), £2000. At a town meeting at

Preston, on Thursday week, a third subscription for the relief of the

existing distress was opened. Upwards of £9000 was promised, including Horrocks, Miller, and Co., £2000; Swainson, Burley, and Co., £1000. Leeds

has subscribed £16,000. The subscriptions received from Manchester and

Salford amounted to about £90,000— viz., £60,000 devoted to general relief

and £30,000 for purely local distribution. Amongst the subscriptions

received by the Central Relief Committee at Manchester are the

following:—A third sum of £1000 from the diocese of Gloucester and

Bristol, £2000 from Birmingham, £6000 from Edinburgh. The Lord Bishop of

Bath and Wells has forwarded another sum of £1000, making a total of £2600

as the receipts up to the present time of the parochial collections. The

Wesleyans have raised about £15,000, and expect to make it about £30,000,

half of which will be given to the general fund, and the other half

appropriated to the relief of their own people.

__________________________

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS

29th November, 1862

LANCASHIRE DISTRESS AND RELIEF ORGANISATION.

MANCHESTER.

(From our own Correspondent.)

I AM now in a position

to enter pretty fully into the organisation for the relief of the

distressed operatives at Manchester. I will commence by stating what is

being done by the guardians. Manchester, with a population of 332,000, is

divided into three unions. The Township Union contains 190,000 people. The

value of the property on which the rate is assessed is £850,000. The rate

laid in June last for the whole year was 3s. 8d. in the pound, and it is

expected that another rate of 1s. 6d. at least must be raised to carry the

guardians through the year. Out of this population 12,311 cases are now in

receipt of outdoor relief, representing 31,285 persons; 3443 received

indoor relief: in all, 34,428. Without specifying in particular this

union, I think I shall be correct in saying that, throughout the unions of

Manchester and Salford, the relief granted by the guardians amounts to 1s.

6d. per head per week. The workhouses generally are full of those old

stereotyped cases of pauperism for whom the picking of oakum is a worthy

employment; but many of the better class are removed to Crumpsal, where

some 1000 or 1200 may be seen reducing a farm of fifty acres to a state of

Belgian tillage. The labour-test has for the most part, however, given way

to public opinion. A different test is sought to be established. Several

schools for adult recipients of relief have been established. In Jersey

and Bengal streets two are to be found containing 1200 men, who receive

relief on condition that they attend. Besides this, the guardians very

properly recognise the schools established by masters in their mills, and

are willing to regard attendances there as work done. I visited one school

or sewing-class of this kind at the Phoenix Mill, St. Jude's parish, where

160 women and girls above sixteen years of age received 2s. 6d. a week,

the relief committee adding 1s. 2d., or at least so much as brought the

sum total to 3s. 4d. With regard to the children, no advantage has been

taken as yet of Denison's Act. The school pence are paid by private

individuals in many cases, but not by the guardians.

|

|

|

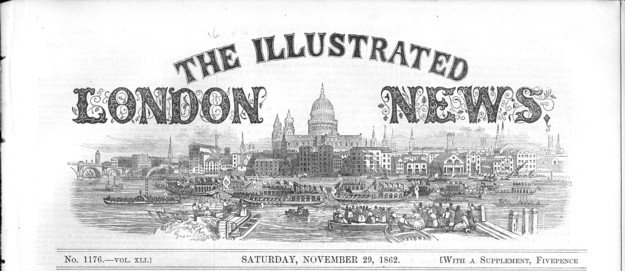

School for mill operatives at Stirling's Mill, Lower

Moseley Street, Manchester. |

I now come to the operations of the Central, Executive, and

Local Relief Committees. The two first particularly undertake to collect

money, to receive money and clothing transmitted from various parts, and

to see to the distribution of these to the local committees throughout the

suffering districts of the county. Of the executive committee Lord Derby

is chairman. Over the general committee the Mayor of Manchester presides,

with J. W. Maclure, Eq., for hon. secretary. The total of the Manchester

subscription amounts to about £75,000. The Cotton Districts Relief

Committee grants £12,000 monthly; the Liverpool Operatives Relief Fund

Committee grants £6000 monthly; while from other sources some £90,000 have

flowed in to the fund administered at Manchester. It is also necessary to

notice a collecting committee, recently appointed, to whose strenuous

canvass a considerable amount of the increased supply of means is due. The

general committee now meets in the warehouse lent by Earl Ducie. The

ground floor is used for the reception and dispatch of parcels of

clothing, which arrive in large quantities from all parts of the kingdom.

These are carried to an upper floor, where they are opened, sorted, and

repacked. Each bale contains an equal number of articles; and as the

clothing is granted to the local committees in bales nothing remains but

to take the number required from the heap in reply to an order. Some

ninety packages arrive every day, and, as about 25 people are employed in

packing and unpacking, the scene, as shown in last week's Issue, is

necessarily a busy one.

|

|

|

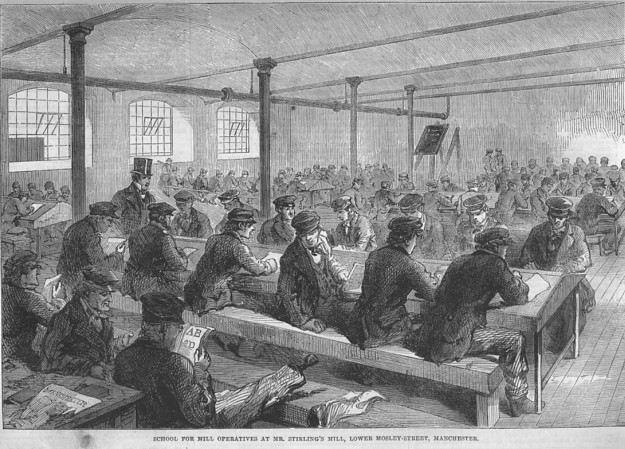

The Manchester and Salford Provident Society

distributing clothing. |

This general committee has nothing to do with individual

relief. This is intrusted to local committees. So far as Manchester and

Salford are concerned, advantage has been taken of the staff of the

District Provident Society. From the report of this institution, which was

established in 1833, I find that it had originally two functions:—First,

that of an inquiry office, to which cases of mendicity were referred by

its subscribers for investigation; secondly, it act as a penny bank. It

rarely gave relief, but "sent back each case, with the ascertained facts,

to the subscribers who had initiated the inquiry." As a banking

establishment it took charge, at fifteen offices throughout the town, of

the small savings of the poor. Here was a body of managers and a staff of

visitors, with an energetic secretary in Mr. James Smith. The usual

business having fallen off in consequence of the distress, the managers,

"while not abandoning their annual subscription of £400 to £500," offered

to undertake the distribution of any loan which might be intrusted to

them. The result is that nearly the whole relief of Manchester is now

administered by this body, which, without any canvassing, has received

£15,000 to mitigate this distress, and about £10,000 additional from the

central fund. The society professes now to have completed its

organisation. A perfect network has been improvised. This large community

is divided into seventeen districts, with their several committees, all

acknowledging the headship of the committee of the Provident Society,

under the presidency of the Bishop of Manchester. Some of its most

influential members are J. Heywood, Esq., M.P.; Messrs. S. Fletcher, W.

Langton, E. Lloyd, T. H. Birley, Oliver Heywood, and Herbert Philips. On

the local committees are to be found one representative from each

religious body, millowners, tradesmen, and mill-overlookers. The utmost

catholicity is thus preserved. The work of visitation is intrusted to paid

agents; but, deeming this insufficient, the committee visits as well.

Millowners, clergymen of all denominations, all people of influence

whatever throughout Manchester, are supplied with forms, to be filled in

with the names of those who may apply for relief or be sought out and

found to require it. These forms are forwarded to the office of the

society in John Dalton-street. The secretary at once transmits the form

concerning A. by special messenger to C., the committee of the district

where A. resides. A. is looked up at once, and a relief-ticket is granted,

bearing a specified number, and the original form containing all

particulars with respect to A. is returned to the office, a like number

being attached to it. When the turn for A.'s district to receive relief

comes, he presents his ticket at the pay office, finds his relief already

calculated according to scale, and receives coloured cards for the amount

in meal, and bread, and soup. Suppose I give an example: —District A 1, E.

W., aged fifty-two, washes, five children; total family, six; total

earning, 4s. 6d.; parochial relief, 4s.; society's relief, 3s. 4d. in

tickets. Again: S. and J. C., age, thirty-five; number of children, four;

total, six; guardians' relief, 0; society's relief, 3s. And, be it

remembered, that the relief of the society in kind exceeds the nominal sum

in value. In 3s. the recipients gain about 6d. Every recipient of relief

also obtains, without application, a grant of coals, and, I believe, of

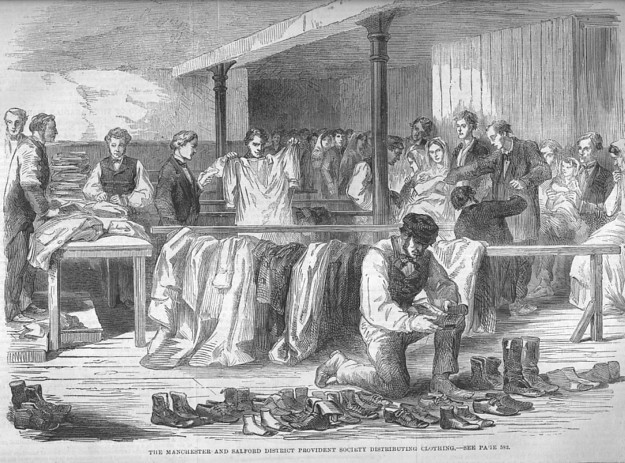

clothing. On another page will be found the store or shop at which these

poor people exchange their tickets for food. Upon these tickets the

dealer, of course, claims repayment of the society. Last week were given

views of the Friends' Soup Kitchen to which the Provident Society

commissions its devouring army, and full particulars were given concerning

the quantities consumed. I may repeat, however, that it is sold below cost

price. This society takes personal oversight of about 4000 families which

do not come within these districts. For the purpose of dealing efficiently

with these an old mill in Garden-lane was taken five months since, and

there I found depot for clothing, the working offices of the committee,

and sewing-schools. The appeal for clothes had been well responded to,

but, on the day I visited the place not a remnant of the stock remained.

Two days earlier, and I should have found the apartments full.

|

|

|

|

|

Provision-shop where goods are obtained for tickets

issued by the

Manchester and Salford Provident Society. |

The committee had been clearing the warehouses of unsalable

goods at cheap rates and obtaining gifts of blankets, &c., and such was

the stock I saw. "This week," said the secretary to me, "we have expended

£5000 in clothing, but it will all be gone in ten days." I wish I could

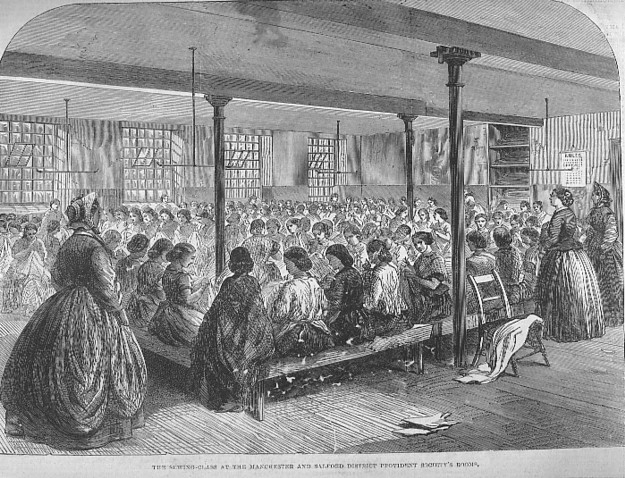

stop to dwell on the distribution scene, but the pencil-picture of it on

another other page is much more striking than any word-picture I could

give. Fancy, however, must lend to the faces their careworn and grateful

expression. The people are full of gratitude; and if I here say that one

happy result of this calamity will be the blending of classes, and the

lesson to the lower class concerning the affectionate regard entertained

for them by the higher classes, the remark will not be out of place. The

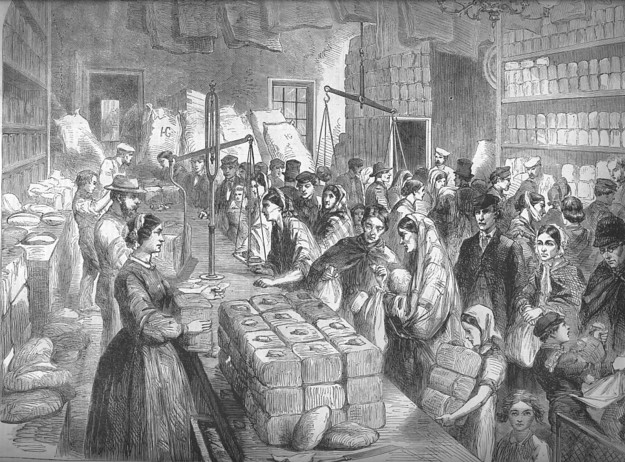

sewing-school here established contains 152 young women, who read, write,

and work by turns. The needles are employed for the most part on the new

material; but the inmates are also allowed to mend their own clothes. The

ladies who manage the class have arranged to give the girls a meal at noon

for 1d. The constituents of this potatoes; meat, onions, dripping, pepper

and salt—cost (without fuel and plant) from 13s. to 14s. a day, so that it

may be called a self-paying concern. The girls work five days a week, and

receive 3s. 4d. This old mill may, therefore, be imagined a scene of

constant activity, and deserves a fuller description than I can now

pretend to give. Before I pass from the operations of this society, I must

not omit to say that each district has its sewing-classes, giving

employment to 500 or 700 girls, who receive 3s. 4d., a penny dinner, and

some elementary teaching. A company of twelve is usually draughted out of

each class for housework. They cook the noon meal and keep the apartments

clean. Everything is thus done for the comfort of the girls, and for their

instruction in arts of which they are so lamentably ignorant. These

classes are generally held in the mills: they are perfectly unsectarian;

the spirit that pervades them is excellent and the young women recognise

with lively gratitude the efforts which are being made for their comfort

and instruction. Several of them were visited by me. On questioning the

inmates, I found that they had been accustomed to receive from 7s. to 12s.

a week, and were doing their best to make the most of the present scanty

pittance. It is difficult to say what numbers are thus being cared for,

for this movement has not long begun and school and sewing-classes are

daily rising up in all parts of the city and its suburbs.

|

|

|

The sewing-class at the Manchester and Salford

Provident Society's rooms. |

This, then, is the agency for the relief of the Manchester

poor. It is not perfect, for it is constantly expanding; but it is as

complete as can be expected, and the public may well repose confidence in

it. Some few parishes, however, have not made themselves amenable to the

Provident Society. I introduce here the last weekly statement, to Nov. 17,

of one of these—St. Jude's—by way of example :—Heads of families relieved,

1143; individuals, 3438; sewing-class, 160 young women. Cost of provisions

distributed—Bread, £43 2s. 5d.; groceries, £12 10s.; soap, £5; potatoes,

£24; coal, £8; payments to staff, 16s.: total, £93 8s. 5d. Weekly

collections—Firms within the parish £33; collected by members of the

committee within the parish, £4; grant from central committee, £240; Lord

Mayor's committee, £150; other sources, £1: total, £428. Some parishes

refuse to unite with the society because they prefer to uphold the

sectarian spirit.

So far as I can understand, the religious bodies of

Manchester are rather behind those of other places in devising means for

the support of their own poor. Now, however, they are waking up and doing

much to clothe and feed the destitute. Their appeals have been well

responded to, and the help sent is, so far as I can learn, carefully

expended. In justice to those most accustomed to rely on the voluntary

principle, I must add that they not only know how to ask, but how to give.

Amongst the most successful efforts to relieve distress is

that made by a merchant's clerk, a young gentlemen of the name of Birch.

During the early part of this cotton famine Mr. Birch became the almoner

of a nobleman. The sum intrusted to him was £40 a week, and in looking

about for fitting recipients of it he seems to have been struck with the

idea of sewing-schools as the best means of saving the over-tempted female

mill-hands, and determinately threw himself with a simpler faith and

without money into this service. I say without money, because he would not

appropriate the £40 to it. He collected some fifty of his helpless clients

at the Hulme Working Men's Institute, engaged a matron, and set them to

work. It was with difficulty he succeeded in begging the money to pay the

3s. 4d. each at the close of the first week. The hit was popular, his

class was increased the following week to 107. A touching appeal in a

Manchester print enabled him to discharge the duties of paymaster with

honour, but the doors of the institute were besieged with applicants for

admission. Numbers soon increased to 700; still he was supplied with

money, and various church and chapel Sunday schoolrooms were placed at his

disposal. In all, at the present time, there are thirteen schools thus

occupied five days a week, and an aggregate of 2800 souls. Mr. Birch has

raised £4107, his weekly expenditure is now £400, and at the close of the

week ending Nov. 15, he had only a balance sufficient to pay for two days!

This effort of a genuine faith has been encouraged from the Lord Mayor's

Fund, the Central Relief Fund, and is, I believe, receiving the support of

the guardians. The class assembled in Dr. Munro's school I visited: 344

young women were working there, while ladies were reading to them.

Two-thirds of them were Roman Catholics, and consequently the books read

were sectarian. The needles are employed upon old clothes and new

material. The products of this industry are sold to pay wages. The sales

last week amounted to £81. Success is written in the boldness of this

dashing movement.

|

|

|

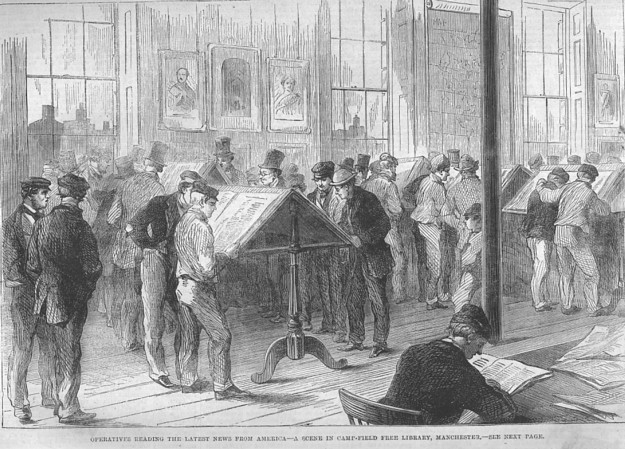

Operatives reading the latest news from America--a

scene in Camp-Field Free Library, Manchester. |

While speaking of Hulme, I must mention the institute for

men, supported by the Township Relief Committee. An old mill with three

floors has been lent for the purpose, where about 400 men are congregated

to read and write from nine to six o'clock five days a week, under proper

teachers. Two meals a day are provided for them on the foundation floor,

while on the two others, supplied with tables and educational requisites,

they polish their wits, and chat and smoke in leisure hours. The windows

are festooned with coloured calico, the whole building is warmed and

lighted, musical instruments are lent by gentlemen, lectures are delivered

every evening, and one evening no even a week is given to music, songs,

recitations, and drollery. These men are all in the receipt of relief. I

mingled freely with them, and found the best spirit to pervade them. Their

docility and respect is very touching. The old hard, insolent manner seems

to be quite softened down. Their teachers are looked upon with great

affection. I spoke with them as to the effect the affliction might have in

opening their eyes to the possibility of finding delight in something

besides a large tale of work and high wages, in giving them a taste for

the refined pleasures of intellectual life, and my remarks met with much

concurrence. There are other schools of this kind, but I mention this as

the best I saw.

I have now noticed all that is being done in the cause of the

distressed operatives of Manchester with means drawn from the public purse

and set forth in subscription lists. In addition, private and hidden

streams are flowing from the masters of silent mills to their suffering

workpeople. Some correspondents have doubted whether instances of this

sort of benevolence are numerous. I only know that it would be on easy

matter for me to fill up the page with the recital of them, but this is

impossible. There are plenty of cases in which, though the mill is

stopped, the hands are receiving £20, £30, £40, and £50 a week, in kind or

cash, and many where the whole mill staff is kept off the rates or the

fund. The efforts put forth at the Chorlton and Sterling mills afford

noble examples of this fact, and must on some other occasion receive more

notice. The Reading-class in the latter is pictured on another page. These

private acts do not reveal themselves; they spring from men who are doing

only what they feel to be right, and who object on this ground to be held

in the public eye. Several milliners have said to me, "You may come and

see what I am doing, but only on condition that you mention no names." The

fact that the workpeople are contented and grateful possesses a

significance as yet imperfectly appreciated. That the operative class can

rise at the cry of injustice is shown clearly enough by the late riot at

Blackburn.

Considerable doubt is expressed lest relief, coming to the

poor from so many independent sources, should be abused. The

thorough-going, regular pauper is in clover; there can be no question

about that, He looks with pleasure as rank upon rank from the industrious

population fall to his level. Little chance is there, however, of families

obtaining more than 2s. a head, so well are the cases investigated. The

guardians set their faces very resolutely against one device which is

employed to increase receipts—I mean the breaking up of families; the boys

and girls going into lodgings so that they may claim separate relief. But

in Manchester this is not found to be the great difficulty. The people, as

a rule, had rather starve than ask relief, and they are in more danger of

starving than of living riotously upon the proceeds of imposition.

House-to-house visitation sets the sceptic right on this point in very

quick time. I have made my observations on these families in all their

stages, even to those where death was within a few steps waiting to close

the hard but unsuccessful struggle for life. Such a morning's work entails

an empty pocket so surely as it is undertaken, for one cannot withstand

the intense pleading of silent want. Halfpence will drop out into little

famished hands, and shillings into the arms of mothers who weep over the

sufferings of the children from whose cheeks the roses have fled long

since. Yet I never once was asked for charity, and the district visitor

must use the query cleverly if he will probe the wound. I will take two or

three cases from my notebook, by the help of which the touching scenes

portrayed by the artist will be better realised. One house I went into

contained a family of seven. They had been accustomed to earn 27s. 6d.,

and now obtained from all sources less than 2s, a head, and they had

1s.6d. to pay for rent. They were occupying two rooms only, the bedding

had all disappeared, and they lay on the bare bedstead at night, huddled

together, without removing their ragged clothes. Again: a man and wife,

with eight children. The husband's parochial relief, 7s. 6d.; from the

relief fund, 3s. 6d. and one cwt. of coal. Out of this 11s. a week 1s. 6d.

should be paid for rent, and the remainder is left to support a family

which has been accustomed to 45s. Again: a family of seven. The husband is

sickly, two boys earn 5s., no parish relief, the relief fund affords 5s.

They have been accustomed to 37s. weekly. The rent is 2s. 1d. The boys are

hearty. "What is there," as the poor mother said, "on which they can

exercise their appetites?" Again: a family of eleven; parish. relief, 8s.

6d.; from committee, 6s.; rent, 3s. They have been out of employ forty-one

weeks, and have never received more than 16s. a week. I asked how they had

managed to exist, and was told that the 65s. per week which they did earn

formerly helped them to occupy a nice house, to stock it with new

furniture, to lay up a little in the bank, and to buy a share in some

co-operative concern. First the deposits were drawn front bank, then some

of the superfluous furniture was sold, then the share so proudly held was

relinquished, and after that the course had been one of rather rapid

descent. Before this family came upon the ratepayers they had expended

property of their own to maintain the policy of the country with regard to

the American States amounting to £30. I might extend the catalogue, but

there is no need for it. We may as well stop with this last instance,

which affords so true a picture of the operative classes, and the losses

they have personally sustained before they have allowed themselves to fall

upon public charity. If we take the pressure of this great calamity upon

the population of Manchester alone, and estimate its value in money, we

may easily calculate that the rate which has been borne has not been

simply one of 3s. 8d. in the pound, but one more nearly approaching 15s.,

and this at a time when the huge capital invested in the cotton

manufacture has been lying idle. It may be that some millowners are not

doing their duty and that cases of imposition occur, but we do not forbear

to feed the fowls because the sparrows pick a few kernels of the handfuls

we cast to them.

__________________________

THE TIMES,

August 13, 1867.

MIDLAND CIRCUIT.

LEEDS, AUG. 12.

NISI PRIUS COURT.—(Before Mr. Baron PIGOTT.)

GARTSIDE V. BRIEFLY.

Mr. Digby Seymour, Q.C., and Mr. Kemplay were for the

Plaintiff; Mr. Maule, Q.C., and Mr. Wills for the defendant.

This was an action for an assault. The plaintiff is a

cotton-spinner, and the defendant a cloth manufacturer, and both live at

Denshaw near Saddleworth. The plaintiff is also a trustee of the

school and churchwarden of the parish church, and the defendant is a

member and the chief promoter of a reading club at Denshaw. This

club was opened on the 24th of March last year, and some of the trustees,

without consulting the plaintiff, had given permission to use the

schoolroom for an opening entertainment, Dr. Ramsden presided on the

occasion; and Mr. Edwin Waugh, known as the "Lancashire Poet" had

consented to give readings from a prose work of his, entitled Besom Ben.

The entertainment was diversified by hymns and other vocal music given by

the church choir. In the middle of the evening, about half-past 8

o'clock, the plaintiff went into the school-room and found Mr. Waugh

engaged in reading an extract from Besom Ben.

This tale, which is

founded upon an old story very popular in Lancashire, relates the

adventures of a tinker of Lobden with his donkey. On one of his

excursions Ben arrives at a mill where sacks of corn are being hoisted

from the ground to an upper floor, and having sent the man in charge at

the bottom for some beer, conceived the idea of sending up his donkey in

place of a sack of corn. This is done by attaching the hoisting rope

to the belly-band of the ass, and the story then proceeds to describe the

behaviour of the donkey and his master during the ascents as follows:―"The

rope gradually tightened and as soon as the donkey felt itself lifted it

started from its peaceful dream. Its eyes glistened with fear, and

it gave unmistakable evidence of a strong dislike to take flight into

heaven that night and leave dull earth behind it. The poor brute

struggled to lay hold of the ground with its feet. But fate was too

strong for Balaam." In the mill are two men called Twitchel and

Riprap, and their emotions at sight of the ascending donkey are thus

described, "A jackass! Iv it isn't aw'll go to the crows!" said Twitchel,

gathering himself up and staring with all his eyes from the back of a bag

of wool, "Ay, it is a jackass," said Riprap, rubbing his eyes and going

nearer to make sure of the thing. "It's a jackass, begow.

Heaw's th' moon, Twitch!" The story then goes on to tell how as the

tail came round Twitchel tried to catch the donkey by it, and was rewarded

by a violent kick "a little below the dinner-trap."

The case for the plaintiff was that upon hearing this he gave

utterance to an exclamation of disapproval, whereupon the defendant came

up to him and seizing him by the collar threw him down and knocked his

head against the floor.

On cross-examination, the plaintiff was asked to read the

passage he disapproved. At first he excused himself, on the ground

that the story was in the Lancashire dialect, while he was a Yorkshireman;

but upon being pressed to translate it into Yorkshire, read the following

passage descriptive of Ben's feelings during the ascent of the donkey.

"'Howd fast, good bally-bant," cried Ben, gazing up and clasping his

hands, "Hawd fast; iv thae gi's way aw'm done for. Eh, Dimple!

I wish thee and me wur safe a whom this neet. What a stark, starin'

jumped up foo' au wur to send tho up theer! Iv that bally-bant

breiks, aw'll jow' my yed straight off again this stone wole. Iv aw

duunnot, aw'll go to th' say. Weigh! gently! Take care, owd

bird! Aw'Il never face Lobden again iv owt happen thee—never while

aw've teeth an' een i' my yed!" This was the passage, the plaintiff

said, which caused him to utter the sounds of disapproval.

The case for the defendant was that the plaintiff was quite

drunk, and was interfering with the pleasure and harmony of the evening by

uttering exclamations in a sneering tone, such as "Oh, oh!" "Ah,

ah!" "Just so!" "What fun!" The defendant went up to

him, and, offering to find him a seat, requested him to discontinue

annoying the company. The plaintiff, however, persisted in his

conduct, whereupon the defendant took hold of him and gently removed him

from the room.

The jury found a verdict for the plaintiff for 40s.

__________________________

THE COTTON FAMINE.

|

There's a moan on the gale, there's a cry in the air,

'Tis the wail of distress, 'tis the sigh of despair

All silent and hushed is the factory's whirl,

And famine and want their black banner unfurl

Where the warm laugh of childhood is hushed on the ear,

And the glance of affection is met by the tear;

Where hope's lingering embers are ready to die,

And utterance is choked by the heartbroken sigh.

From "A Visit to Lancashire in December, 1862,"

By ELLEN

BAILEE.

|

THE supply of cotton

from North America nearly ceased in consequence of the secession of the

Southern States from the Union in 1860-61. At the beginning of the

latter year the prospect seemed to the operatives so bright that they

pressed for an advanced in wages. In March there was a turn-out of

weavers at several mills. Somewhat suddenly the American Civil War broke

out, and at once it was realised that the mills must close for want of

cotton unless the war came to an end soon. The weavers returned to work

after a brief struggle, but the war continued and the mills were run short

time. Some were closed altogether, and the operatives, with aching hearts,

became unwilling recipients of relief. "Short commons and long faces,"

said one, were his recollections of the "panic." "I wur nobbut a lad at

th' time, but I'd a lad's keen feelin's, especially in certain vital

parts. I wur punced through th' panic, I wur."

So scarce did employment become that in the winter of 1862-3 nearly 7,000

of 11,484 operatives usually employed were out of work, and a large number

of those employed were on short time. Of 39 cotton manufactories, 24

foundries and machine shops, and three bobbin turning shops in the town,

only five were employed full time with all hands; 17 full time with a

reduced number of hands; 34 on short time; and seven were stopped. A

gigantic system of relief was organised in the town, and it is said that

more than three-fourths of the population became dependent. The cotton

operatives were not so well organised as now, and what little they had

saved was soon exhausted. Contributions of money, immense quantities of

clothing, and cloth for making up flowed in from all parts of England. To

provide food for the distressed people orders on grocers in the town were

issued. To clothe them the garments received from various parts were

distributed, and the tailors of the town were employed by the relief

committee to make up the cloth. When that work was done many of the

tailors went to the workhouse, some to repair the clothing of the inmates,

and some to become inmates themselves. The Rev. Mr. and Mrs. Hoare started

a school in the Albion Mills, employing a tailor to teach the men who

attended to mend their own clothing. Another considerate action of Mr.

Hoare's was to forego his fees for marriages solemnised at St. Paul's. Mr.

James Buckley, of Buckley and Newton's, was a generous helper. It is said

that he told the people, "You'll never starve so long as you have plenty

of bacon and potatoes," and he gave large quantities of those comestibles. About the beginning of 1863 our society distributed quantities of stew

from the butchering department.

Mr. B. Worth had the shop at the end of Castle Street. On one occasion a

mob of half-famished people went for it, but Mr. Worth was prepared. He

announced that if they would come at ten o'clock the next morning he would

distribute 200 loaves. The crowd passed on; at the appointed time the

loaves were thrown from the windows and caught by the people.

Sewing schools were opened for the women and girls, who were paid for

attending, and instructed in dressmaking and other sewing work each

afternoon, and in ordinary school subjects in the morning. These are

referred to in Sam Laycock's "Sewin' Class Song"―

|

Come, lasses, let's cheer up an' sing

It's no use lookin' sad;

We'll mak' our sewin' schoo' to ring,

An' stitch away like mad.

We'll try an' mak' th' best job we con

O' owt we han to do;

We read, an' write, an' spell, an' keawnt,

While here at th' sewin' school'.

Sin' th' war began, an' th' factories stopped,

We're badly off, it's true,

But still we needn't grumble,

For we'n noan so mich to do;

We're only here fro' nine to four,

An' han an hour for noon;

We noather stop so very late,

Nor start so very soon. |

One rather humorous local incident may be remembered by some readers. Mr.

Bates' mill in Castle Street was used as one of the relief stores. A man

stationed at the door for the purpose of regulating the applicants had a

way of issuing the command "Hook it!" to any applicant who became

importunate. The expression stuck to the man the rest of his life, and

after his death people were asked, " Do'st know Hook-it's 'dead?"

Another, a retired army sergeant, marched out numbers of the unemployed

men and put them through exercises; anything to keep them occupied.

The decision of the relief committee to issue tickets instead of money

resulted in the "Bread Riots." The great excitement commenced on the

morning of Thursday, March 19th, 1863, when the executive committee sent

word to the schools that relief would be given by ticket at the rate of

3s. a week, but that a day in hand would be kept. The scholars objected.

They contended that they ought to receive their "wages" in money and to

the full amount, or attend what they termed the labour test certain hours

per week less. The tickets were refused, and a vast crowd congregated

around Castle Street Mill. The windows of a cab in which Mr. Bates and Mr.

J. Kirk were riding had its windows smashed, portions of the mill

machinery were broken, and missiles were thrown at the police, who had

turned out under the superintendence of Mr. Wm. Chadwick, chief constable. The officers were quite overpowered by the mob, which numbered hundreds. Much damage was done to shops in Market Street, particularly those

occupied by Mr. Brierley, the druggist, and Mr. Dyson, the eating-house

keeper, and the shopkeepers were soon busy putting up their shutters. The

animus of the mob seemed to be directed, however, toward the more

prominent members of the relief committee. At Mr. Bates' house, in Cockerhill, windows were broken and many valuable pieces of furniture

destroyed, even young women joining in the wanton destruction. From there

the mob turned again to Market Street, Melbourne Street, and Caroline

Street. Every window of the Central Relief Committee rooms in Melbourne

Street was smashed. At the shop of Mr. Ashton, another member of the

relief committee, bottles, canisters, and groceries were thrown about and

destroyed savagely. There was also an onslaught on our society's drapery

department in Caroline Street, but the mob desisted when it was found that

the shop was not Mr. Ashton's property. Two adjoining shops were used as

relief stores. They were quickly broken open, and a scene more disgraceful

perhaps than any other enacted. Piles of clothing and cloth were hurled

out of the upper windows to the people in the street.

A cry was raised that the soldiers were coming, but amidst laughter from

the mob it was declared to be only a woman in a red cloak, and the work of

destruction went on, several things being wantonly set on fire, until, a

little after half-past five, a company of the 14th Hussars from the Ashton

Barracks, under the command of Captain Chapman, appeared in sight. The

soldiers galloped along flourishing their swords, and every one in the

crowd looked to his or her personal safety. Some of those still in the

store, in attempting a hasty retreat, fell at the entrance; others behind were thrown upon them, and there the people lay, five or six deep,

male and female, when the soldiers reached them. The police were almost as

soon as the Hussars, and some who had created such havoc were easily

captured. Amidst the hooting and yelling, Mr. D. Harrison read the Riot

Act, and the troops proceeded to clear the streets. To escape detection

some of the plunderers burned the clothing; others threw it into the

canal and the river Tame, and various articles of wearing apparel could be

seen for some time floating on the water. Special constables were sworn

in, armed with sabres, and arrangements were made for the calling in of

fifty of the Cheshire police force should their services be required. Under the protection of the military the police visited certain parts of

the town, where they found large quantities of the stolen clothing, and

many more people were taken into custody. At 10 o'clock the soldiers were

called off and the town was left to the guardianship of the police and

special constables. When the prisoners were brought before the magistrates

they were admonished by Mr. David Harrison (chairman) and Mr. John Cheetham. It was a most disgraceful thing, they were told, that after so

much had been done for the people the benefactors should be turned upon

and abused as they had been. Mr. Bates, for instance, had opened his door

to the people, and this was the return they had made for his kindness. He

(Mr. Cheetham) had been speaking publicly in London, within a fortnight,

of the high character he thought they had won for their patience and

forbearance under their trials. He felt it deeply; he felt that they had

not only alienated the people at a distance, but had disgraced the town. Many of the prisoners were committed to Chester for riot.

There was further resistance to the police and military when two omnibuses

appeared for the purpose of conveying the prisoners to the railway station

to take train for Chester, brickbats and other missiles being thrown. The

people vowed that they would have something to eat before they went to

bed, and would "clem" no longer. Prisoners to the number of 29 were

placed in a separate railway carriage and left the station amidst loud

cheering. Twice the cavalry rode through the mob, creating the greatest

consternation, and a company of infantry marched the streets with fixed

bayonets, but little personal injury was done. On one or two occasions

blood was drawn; the sight of it had a great effect on the crowd, and

order was restored.

In the spring and summer of 1865 a few more hands were employed in the

mills. When the panic was at its height there were, it is said, 730 houses

and shops empty, and in October, 1866, there were still 620. It was

estimated that before the panic had lasted two years about 1,000 persons

had emigrated, and from 1861 to 1866 the population had decreased by

2,000. At the height of the distress there was the extraordinary spectacle

of 84 persons emigrating to Australia in a body, headed through the town

by a band of music, with flags flying and thousands of people cheering.

Mr. William Cooper, referred to elsewhere as the first cashier of the

Rochdale Pioneers, wrote to

Mr. Holyoake that Stalybridge, Ashton, Mossley,

Dukinfield, Hyde, Heywood, Middleton, and Rawtenstall had suffered badly,

being almost entirely cotton manufacturing towns, but that none of the

stores had failed, so that, taken altogether, the co-operative societies

in Lancashire were as numerous and as strong after the cotton panic as

before it set in. Mr. Cooper wrote of Manchester at the same time rather

contemptuously, that it was good for nothing then except to sell cotton. But even Manchester, he said, had created a Manchester and Salford store,

maintained for five years an average of 1,200 members, and made for them

£7,000 of profit. What would Mr. Cooper think now, we wonder, of the same

Manchester and Salford store, with its 18,000 members?

In 1852 Mr. T. Bazley warned the country of the danger of trusting to

America alone for cotton. In 1857 there was formed the Cotton Supply

Association, with our townsman, the late John Cheetham, M.P., as

president. The scheme had its inception in the fears of a portion of the

trade that some dire calamity must sooner or later overtake the cotton

manufacture of Lancashire if it were left to depend upon the treacherous

foundation of slave-labour as the main source of its raw material. The

association established agencies in various countries, and distributed

large consignments of cotton seed and preparatory machinery, but the

scheme did not meet with the support it deserved.

In May, 1862, Mr. Bazley stated that through the failure of the American

supply the loss to the labouring classes was £12,000,000 a year, and

estimated the loss including the employing classes at nearly £40,000,000 a

year. In the Lancashire district―population about 4,000,000—there were

receiving parish relief, September, 1861, 43,500 persons; in September,

1862, 163,498. The Union Relief Act, passed August, 1862, gave much relief

by enabling overseers to borrow money to be expended in public works

executed by the unemployed workmen. In October, 1864, much distress still

existed, and fears for the approaching winter were entertained. At that

time, it was stated in the Times of 18th January, 1865, there were 90,000

more paupers than ordinary in cotton districts. In June, 1865, a special

commissioner appointed in May, 1862, was recalled by the Poor Law Board,

and the famine was declared ended. £1,000,000 had been expended in two

years. The executive of the central relief fund held their last meeting on

the 4th December, 1865.

__________________________ |

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)