|

[Previous

Page]

SPEECH OF THE

EARL OF

DERBY

AT THE COUNTY MEETING, ON THE 2ND DECEMBER 1863.

THE EARL OF SEFTON IN THE CHAIR.

|

|

|

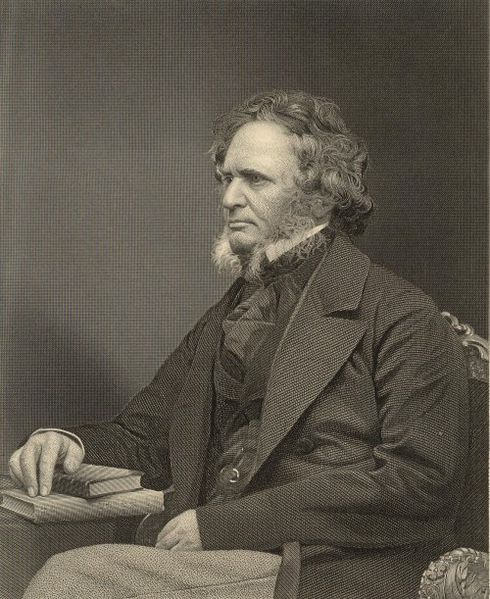

Edward Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

(1799-1869).

During the American Civil War, Lord Derby was

chairman of the Central Executive Committee that worked to alleviate

the distress being experienced by the Lancashire textile workers

caused by the cotton famine. |

The thirteen hundred circulars issued by the Earl of Sefton,

Lord-Lieutenant of Lancashire, "brought together such a gathering of rank,

and wealth, and influence, as is not often to be witnessed; and the

eloquent advocate of class distinctions and aristocratic privileges (the

Earl of Derby) became on that day the powerful and successful

representative of the poor and helpless." Called upon by the

chairman, the Earl of Derby said: ―

"My Lord Sefton, my Lords and Gentlemen, ― We are met together upon an

occasion which must call forth the most painful, and at the same time

ought to excite, and I am sure will excite, the most kindly feelings of

our human nature. We are met to consider the best means of

palliating ― would to God that I could say removing! ― a great national

calamity, the like whereof in modern times has never been witnessed in

this favoured land ― a calamity which it was impossible for those who are

the chief sufferers by it to foresee, or, if they had foreseen, to have

taken any steps to avoid ― a calamity which, though shared by the nation at

large, falls more peculiarly and with the heaviest weight upon this

hitherto prosperous and wealthy district ― a calamity which has converted

this teeming hive of industry into a stagnant desert of compulsory

inaction and idleness ― a calamity which has converted that which was the

source of our greatest wealth into the deepest abyss of impoverishment ― a

calamity which has impoverished the wealthy, which has reduced men of easy

fortunes to the greatest straits, which has brought distress upon those

who have hitherto been somewhat above the world by the exercise of frugal

industry, and which has reduced honest and struggling poverty to a state

of absolute and humiliating destitution. Gentlemen, it is to meet this

calamity that we are met together this day, to add our means and our

assistance to those efforts which have been so nobly made throughout the

country generally, and, I am bound to say, in this county also, as I shall

prove to you before I conclude my remarks. Gentlemen, I know how

impossible it is by any figures to convey an idea of the extent of the

destitution which now prevails, and I know also how impatient large

assemblies are of any extensive use of figures, or even of figures at all;

but at the same time, it is impossible for me to lay before you the whole

state of the case, in opening this resolution, and asking you to resolve

with regard to the extent of the distress which now prevails, without

trespassing on your attention by a few, and they shall be a very few,

figures, which shall show the extent, if not the pressure, throughout this

district, of the present distress. And, gentlemen, I think I shall best

give you an idea of the amount of distress and destitution which prevails,

by very shortly comparing the state of things which existed in the

districts to which I refer in the month of September 1861, as compared

with the month of September 1862, and with that again only about two weeks

ago, which is the latest information we have ― up to the 22nd of last month.

|

TH' SHURAT

WEAVER'S SONG.

[4.]

CONFOUND

it! aw ne'er wur so woven afore,

Mi back's welly brocken, mi fingers are sore;

Aw've bin starin' an' rootin' among this Shurat,

Till aw'm very near getten as bloint as a bat.

Every toime aw go in wi' mi cuts to owd Joe,

He gies mi a cursin', an' bates mi an' o;

Aw've a warp i' one loom wi' booath selvedges marr'd,

An' th' other's as bad for he's dress'd it to hard.

Aw wish aw wur fur enuff off, eawt o' th' road,

For o' weavin' this rubbitch aw'm gettin' reet stow'd;

Aw've newt i' this world to lie deawn on but straw,

For aw've only eight shillin' this fortni't to draw.

Neaw aw haven't mi family under mi hat,

Aw've a woife an' six childer to keep eawt o' that;

So aw'm rayther among it at present yo see,

Iv ever a fellow wur puzzled, it's me!

Iv one turns eawt to steal, folk'll co me a thief,

An' aw conno' put th' cheek on to ax for relief;

As aw said i' eawr heawse t' other neet to mi woife,

Aw never did nowt o' this sort i' mi loife.

One doesn't like everyone t' know heaw they are,

But we'n suffered so long thro' this 'Merica war,

'At there's lot's o' poor factory folk getten t' fur end,

An' they'll soon be knock'd o'er iv th' toimes don't

mend.

Oh, dear! iv yon Yankees could only just see

Heaw they're clemmin' an' starvin' poor weavers loike

me,

Aw think they'd soon settle their bother, an' strive

To send us some cotton to keep us alive.

There's theawsands o' folk just i' th' best o' their days,

Wi' traces o' want plainly seen i' their face;

An' a future afore 'em as dreary an' dark,

For when th' cotton gets done we shall o be beawt wark.

We'n bin patient an' quiet as long as we con;

Th' bits o' things we had by us are welly o gone;

Aw've bin trampin' so long, mi owd shoon are worn

eawt,

An' mi halliday clooas are o on 'em "up th' speawt."

It wur nobbut last Monday aw sowd a good bed—

Nay, very near gan it—to get us some bread;

Afore these bad times cum aw used to be fat,

But neaw, bless yo'r loife, aw'm as thin as a lat!

Mony a toime i' mi loife aw've seen things lookin'

feaw,

But never as awk'ard as what they are neaw;

Iv there isn't some help for us factory folk soon,

Aw'm sure we shall o be knocked reet eawt o' tune.

Come give us a lift, yo' 'at han owt to give,

An' help yo're poor brothers an' sisters to live;

Be kind, an' be tender to th' needy an' poor,

An' we'll promise when th' times mend well ax yo no

moor.

SAMUEL

LAYCOCK. |

"I find then, gentlemen, that in a district comprising, in round numbers,

two million inhabitants ― for that is about the number in that district ― in

the fourth week of September 1861, there were forty-three thousand five

hundred persons receiving parochial relief; in the fourth week of

September 1862, there were one hundred and sixty-three thousand four

hundred and ninety-eight persons receiving parochial relief; and in the

short space which elapsed between the last week of September and the third

week of November the number of one hundred and sixty-three thousand four

hundred and ninety-eight had increased to two hundred and fifty-nine

thousand three hundred and eighty-five persons. Now, gentlemen, let us in

the same periods compare the amount which was applied from the parochial

funds to the relief of pauperism. In September 1861, the amount so applied

was 2,259 pounds; in September 1862, it was 9,674 pounds. That is by the

week. What is now the amount? In November 1862 it was 17,681 pounds for

the week. The proportion of those receiving parochial relief to the total

population was two and three-tenths per cent in September 1861, and eight

and five-tenths per cent in September 1862, and that had become thirteen

and five-tenths percent in the population in November 1862. Here,

therefore, is thirteen per cent of the whole population at the present

moment depending for their subsistence upon parochial relief alone. Of

these two hundred and fifty-nine thousand ― I give only round

numbers ― there were thirty-six thousand eight hundred old or infirm; there

were nearly ninety-eight thousand able-bodied adults receiving parochial

relief, and there were under sixteen years of age nearly twenty-four

thousand persons. But it would be very far from giving you an estimate of

the extent of the distress if we were to confine our observations to those

who are dependent upon parochial relief alone.

"We have evidence from the local committees, whom we have extensively

employed, and whose services have been invaluable to us, that of persons

not relieved from the poor-rates there are relieved also by local

committees no fewer in this district than one hundred and seventy-two

thousand persons ― making a total of four hundred and thirty-one thousand

three hundred and ninety-five persons out of two millions, or twenty-one

and seven-tenths per cent on the whole population ― that is, more than one

in every five persons depend for their daily existence either upon

parochial relief or public charity. Gentlemen, I have said that figures

will not show sufficiently the amount of distress; nor, in the same

manner, will figures show, I am happy to say, the amount that has been

contributed for the relief of that distress. But let us take another test;

let us examine what has been the result, not upon the poor who are

dependent for their daily bread upon their daily labour, and many of whom

are upon the very verge of pauperism, from day to day, but let us take a

test of what has been the effect upon the well-to-do artisan, upon the

frugal, industrious, saving men, who have been hitherto somewhat above the

world, and I have here but an imperfect test, because I am unable to

obtain the whole amount of deposits withdrawn from the savings banks, the

best of all possible tests, if we could carry the account up to the

present day; but I have only been able to obtain it to the middle of June

last, when the distress could hardly be said to have begun, and yet I find

from seven savings banks alone in this county in six months ― and those

months in which the distress had not reached its present height, or

anything like it ― there was an excess of withdrawals of deposits over the

ordinary average to the amount of 71,113 pounds. This was up to June last,

when, as I have said, the pressure had hardly commenced, and from that

time it as been found impossible to obtain from the savings banks, who are

themselves naturally unwilling to disclose this state of affairs ― it has

been found impossible to obtain such further returns as would enable us to

present to you any proper estimate of the excess of withdrawals at

present; but that they have been very large must necessarily be inferred

from the great increase of distress which has taken place since the large

sum I have mentioned was obtained from the banks, as representing the

excess of ordinary withdrawals in June last.

|

TH' SURAT

WEYVER'S

SONG.

[4.]

We're warkin lads frae Lankysheer,

An' gradely daycent fooak;

We'n hunted weyvin far an' near,

An' couldn't ged a strook;

We'n sowd booath table, clock, an' cheer,

An' popt booath shoon an' hat,

An' borne wod mortal man could bear,

Affoor we'd weyve Surat!

It's neaw aboon a twelmon gone

Sin't "crisis" coom abeawt,

An' t' poor's tried hard to potter on

Tell t' rich ud potter eawt;

We'n left no stooan unturn'd, nod one,

Sin' t' trade becoom so flat,

Bud neaw they'n browt us too id, mon,

They'n med us weyve Surat!

Aw've yerd fooak talk o' t' treydin mill,

Un pickin oakum too;

Bud transpooartation's nod as ill

As weyvin rotten Su!

It's been too monny for eawr Bill,

Un aw'm as thin as a latt,

Bud iv wey wi' t' Yankees hed eawr will,

We'd hang 'em i' t' Surat!

It's just like rowlin stooans up t' broo,

Or twisting rooaps o' sand;

Yo piece yo'r twist, id comes i' two,

Like cobwebs i' yor hand;

Aw've wark'd an' woven like a foo!

Tell aw'm as weak as a cat,

Yet after o as aw could do,

Aw'm konkurd bi t' Surat!

Eawr Mally's i' t' twist fever yon—

Mi feyther's getten bagg'd;

Strange tacklers winnod teck him on,

Becose his cooat's so ragg'd!

Mi mother ses it's welly done—

Hoo'l petch id wi' her brat,

An' meck id fit for ony mon

Wod roots among t' Surat.

Aw wonst imagined Deeoth's a very

Dark un dismal face;

Bud neaw aw fancy t' cemetery

Is quite a pleasant place!

Bud sin' wey took eawr Bill to bury,

Aw've often wish'd Owd Scrat

Ud fetch o t' bag-o-tricks, an lorry

To hell wi o t' Surat!

WILLIAM

BILLINGTON

1862. |

"Now, gentlemen, figure to yourselves, I beg of you, what a state of things

that sum of 71,113 pounds, as the excess of the average withdrawals from

the savings banks represents; what an amount of suffering does it picture;

what disappointed hopes; what a prospect of future distress does it not

bring before you for the working and industrious classes? Why, gentlemen,

it represents the blighted hopes for life of many a family. It represents

the small sum set apart by honest, frugal, persevering industry, won by

years of toil and self-denial, in the hope of its being, as it has been in

many cases before, the foundation even of colossal fortunes which have

been made from smaller sums. It represents the gradual decay of the hopes

for his family of many an industrious artisan. The first step in that

downward progress which has led to destitution and pauperism is the

withdrawal of the savings of honest industry, and that is represented in

the return which I have quoted to you. Then comes the sacrifice of some

little cherished article of furniture ― the cutting off of some little

indulgence ― the sacrifice of that which gave his home an appearance of

additional comfort and happiness ― the sacrifice gradually, one by one, of

the principal articles of furniture, till at last the well-conducted,

honest, frugal, saving working man finds himself on a level with the idle,

the dissipated, and the improvident ― obliged to pawn the very clothes of

his family ― nay, the very bedding on which he lies, to obtain the simple

means of subsistence from day to day, and encountering all that difficulty

and all that distress with the noble independence that would do anything

rather than depend upon public or even on private charity, and in his own

simple but emphatic language declaring, 'Nay, but we'll clem first.'

"And, gentlemen, this leads me to observe upon a more gratifying point of

view, that is, the noble manner, a manner beyond all praise, in which this

destitution has been borne by the population of this great county. It is

not the case of ordinary labourers who find themselves reduced a trifle

below their former means of subsistence, but it is a reduction in the

pecuniary comfort, and almost necessaries, of men who have been in the

habit of living, if not in luxury, at least in the extreme of comfort ― a

reduction to two shillings and three shillings a week from sums which had

usually amounted to twenty-five shillings, or thirty shillings, or forty

shillings; a cutting off of all their comforts, cutting off all their

hopes of future additional comfort, or of rising in life ― aggravated by a

feeling, an honourable, an honest, but at the same time a morbid feeling,

of repugnance to the idea of being indebted under these circumstances to

relief of any kind or description. And I may say that, among the

difficulties which have been encountered by the local relief

committees ― no doubt there have been many of those not among the most

deserving who have been clamorous for the aid held out to them ― but one

of the great difficulties of local relief committees has been to find out

and relieve struggling and really-distressed merit, and to overcome that

feeling of independence which, even under circumstances like these, leads

them to shrink from being relieved by private charity. I know that

instances of this kind have happened; I know that cases have occurred

where it has been necessary to press upon individuals, themselves upon the

point of starvation, the necessity of accepting this relief; and from this

place I take the opportunity of saying, and I hope it will go far and

wide, that in circumstances like the present, discreditable as habitual

dependence upon parochial relief may be, it is no degradation, it is no

censure, it is no possible cause of blame, that any man, however great his

industry, however high his character, however noble his feeling of

self-dependence, should feel himself obliged to have recourse to that

Christian charity which I am sure we are all prepared to give.

Gentlemen, I might perhaps here, as far as my resolution goes, close the

observations I have to make to you. The resolution I have to move,

indeed, is one which calls for no extensive argument; and a plain

statement of facts, such as that I have laid before you, is sufficient to

obtain for it your unanimous assent. The resolution is: ―

"'That the manufacturing districts of Lancashire and the adjoining

counties are suffering from an extent of destitution happily hitherto

unknown, which has been borne by the working classes with a patient

submission and resolution entitling them to the warmest sympathy of their

fellow-countrymen.'

"But, gentlemen, I cannot, in the first place, lose the opportunity of

asking this great assembly with what feelings this state of things should

be contemplated by us who are in happier circumstances. Let me say with

all reverence that it is a subject for deep national humiliation, and,

above all, for deep humiliation for this great county. We have been

accustomed for years to look with pride and complacency upon the enormous

growth of that manufacture which has conferred wealth upon so many

thousands, and which has so largely increased the manufacturing population

and industry of this country. We have seen within the last twelve or

fourteen years the consumption of cotton in Europe increase from fifty

thousand to ninety thousand bales a week; we have seen the weight of

cotton goods exported from this country in the shape of yarn and

manufactured goods amount to no less than nine hundred and eighty-three

million pounds in a single year. We have seen, in spite of all opposing

circumstances, this trade constantly and rapidly extending; we have seen

colossal fortunes made; and we have as a county, perhaps, been accustomed

to look down on those less fortunate districts whose wealth and fortunes

were built upon a less secure foundation; we have reckoned upon this great

manufacture as the pride of our country, and as the best security against

the possibility of war, in consequence of the mutual interest between us

and the cotton-producing districts.

"We have held that in the cotton manufacture was the pride, the strength,

and the certainty of our future national prosperity and peace. I am afraid

we have looked upon this trade too much in the spirit of the Assyrian

monarch of old. We have said to ourselves: ― 'Is not this great Babylon,

that I have built for the house of my kingdom by the might of my power,

and for the honour of my majesty?' But in the hour in which the monarch

used these words the word came forth, 'Thy kingdom is departed from thee!' That which was his pride became his humiliation; that which was our pride

has become our humiliation and our punishment. That which was the source

of our wealth ― the sure foundation on which we built ― has become itself

the instrument of our humiliating poverty, which compels us to appeal to

the charity of other counties. The reed upon which we leaned has gone

through the hand that reposed on it, and has pierced us to the heart.

"But, gentlemen, we have happier and more gratifying subjects of

contemplation. I have pointed to the noble conduct which must make us

proud of our countrymen in the manufacturing districts; I have pointed to

the noble and heroic submission to difficulties they could never foresee,

and privations they never expected to encounter; but again, we have

another feeling which I am sure will not be disappointed, which the

country has nobly met ― that this is an opportunity providentially given to

those who are blessed with wealth and fortune to show their

sympathy ― their practical, active, earnest sympathy ― with the sufferings

of their poorer brethren, and, with God's blessing, used as I trust by

God's blessing it will be, it may be a link to bind together more closely

than ever the various classes in this great community, to satisfy the

wealthy that the poor have a claim, not only to their money, but to their

sympathy ― to satisfy the poor also that the rich are not overbearing,

grinding tyrants, but men like themselves, who have hearts to feel for

suffering, and are prompt to use the means God has given to them for the

relief of that suffering.

|

THE TIMES

5th Nov. 1862.

THE DISTRESS IN LANCASHIRE.

――◊――

MANSION-HOUSE COMMITTEE.

Last evening the total sum received during the day by the Lord Mayor

towards the Mansion-house Relief Fund for the relief of the

prevailing distress amounted to £2,772. The members of the Old

Corn-Exchange, London, through Mr. William Maidlow, contributed the

handsome sum of £707.15s.; Mr. F. W. Beneke, £500; Messrs H. D. and

James Blyth, Greene and Co., £100; Miss H S. (2d donation), £100;

Messrs, Stiebal, Brothers £100; Messrs. Thomson, Bonar, and Co.,

£100; Mrs, Hodgson, £100; Mrs France M. A. Hoare, £100; Mr. F.

Richardson, £50; Mr. George Briscoe £50; Messrs Ripley, Bothers,

£52. 10s; Mrs. Lucas, £20; Mr Henry Bruce, £20; Mr. Joseph Cubitt,

£25; and The Times Companionship, through Mr. Francis Goodlake (5th

instalment), £4. 5s. 6d. "Amicus" has also sent 10s. through Mr.

Goodlake.

ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE.

The borough relief committee of which Mr. B. M. Kenworthy, the mayor

of the borough, is chairman, relieved last week 13,549 persons at a

cost of £374. 11s. 10d. As compared with the previous week, there is

an increase of 705 persons and of the relief given of £16. 8s. The

committee also made the following grants to sewing-classes, viz.:—To

the parish church sewing-class £100; to St. Ann's (Catholic) class,

£30.; to the Methodist New Connexion class, £30.; to Rycroft

(Independent) class, £20.; to the Wesleyan Methodist class £20.; and

to the Independent Methodist class, £5., making in the whole to

sewing-classes £205. The committee also allowed £19. 8s. 4d. for the

instruction of 2,294 poor children at the day-schools of the parish

church, Sr. Peter's, Christ Church. Rycroft (Independent), St. Ann's

and St. Mary's (both Catholic), the Baptists', Joseph Robinson's,

Job Arundale's, William Lister's, Mrs Bowman's, Henry Grimshaw's,

and John Robinson's, making a total expenditure for the week of

£399. 0s. 2d. The following sums have been received during the last

week by the treasurer, Mr. John Ross Coulthart, banker,

Ashton-under-Lyne ― viz., from the Lord Mayor of London, £500.;

Messrs. Brooks, Marshall, and Brooks, solicitors, Ashton, £20., A

Parishioner of Chilton, Thame, Oxon, per the Rev. George

Chetwode.10s.; the Ashton-under-Lyne Cricket Club, £50.; Mr. John

Mills, Nantwich, £5.; Anonymous, £15.; and the second monthly

instalment from the following gentleman ― namely, from Messrs. James

Kenworthy and Co., Ashton, £28; Mr. B. M. Kenworthy Ashton, £10.;

Mr. John Kenworthy, Beech-grove. Harrogate, £20.; and Messrs.

Jonathan Andrew and Son, Ashton, £20; making a total income for the

week of £668. 10s., and leaving a balance in hand of £472 18s. 11s.,

or little more than one week's expenditure.

PRESTON.

At the usual weekly meeting of the relief committed one Monday night

a further large increase in the number of cases relieved was

reported. No less than 41½ per cent of the entire population are

now receiving relief from this committee, the numbers being 8,617

cases, comprising 34,227 persons, who were relieved at a cost of

£853. 1s. 6d., being an increase for the week of 477 cases, 1,516

persons, and an expenditure of £50. 1s. 6d. In addition to this 330

females have been employed at the sewing schools and 900 persons

supplied with nutritious food from the sick kitchen.

Dr. BUCHANAN,

of the Privy Council, attended the meeting of the committee, and

stated that the class of fever which he had found prevailing in

Preston was induced by the low diet the people had been living on,

overcrowding, insufficient clothing, and poor bedding, and suggested

that a more liberal scale of relief should be adopted, and, as far

as possible, overcrowding in beds prevented.

The COMMITTEE

explained to Dr. Buchanan that the suggestions which he had thrown

out were already being acted upon.

The police returns of the state of employment in the mills

are as follow: ― Number fully employed, 3,813; five days, 663; four

days, 2,276; three days, 7,191; two days, 605; and totally

unemployed, 12,874. The number out of work unconnected with the

mills is estimated at 600 and the total weekly loss of wages at

£13,500. The subscription list for the week includes £1,000 received

from the Lord Mayor, £500, from Messrs. Birley Brothers; £704. 19s.,

the proceeds of the Guild festival; £50 from Major the Hon. L.

Powys; and £70 from Mr. T. Tomlinson, being the first of six monthly

instalments.

Mr. Cobden's speech at Rochdale in defence of the

manufacturer has caused considerable comment here. It is alleged

that, in summing up the liabilities of the millowners, he has

unfairly omitted reference to their advantages. It is urged here

that the possessors of mill property worth £50,000 must consider it

a more profitable investment than land, and that in the year 1861

the profits on manufacturing were from 25 to 40 per cent., while

during the present year many large fortunes have been realised owing

to the increased value of accumulated shocks. It is also urged that

all allusion to losses upon cottage property had better have been

omitted, was it is well known that the occupancy of these cottages

by workpeople is compulsory, and excessive rents are in many

instance charged and deducted from the wages.

LIVERPOOL.

The Liverpool committed, taking into consideration the increasing

distress in Lancashire, and also the daily increasing contributions

in Liverpool, have raised their monthly remittance to the Manchester

Central Committee from £4,000, to £6,000, and the treasurers

yesterday remitted £2,000 to supplement their subscription for

November.

PUTNEY.

On Sunday there were collections made at St. Mary's, Putney, and St.

John's New Church, both in the same parish, when the very handsome

sum of £210. 14s. was collected on behalf of the distressed

Lancashire weavers, and which amount was handed over to the Lord

Mayor, who observed that it was the largest collection made in any

parish and that he trusted it would stimulate other perishes to act

in a similar benevolent spirit. |

"Gentlemen, a few words more, and I will not further trespass on your

attention. But I feel myself called on, as chairman of that executive

committee to which my noble friend in the chair has paid so just a

compliment, to lay before you some answer to objections which have been

made, and which in other counties, if not in this, may have a tendency to

check the contributions which have hitherto so freely flowed in. Before

doing so, allow me to say (and I can do it with more freedom, because in

the, earlier stages of its organisation I was not a member of that

committee) it is bare justice to them to say that there never was an

occasion on which greater or more earnest efforts were made to secure that

the distribution of those funds intrusted to them should be guarded

against all possibility of abuse, and be distributed without the slightest

reference to political or religious opinions; distributed with the most

perfect impartiality, and in every locality, through the instrumentality

of persons in whom the neighbourhood might repose entire confidence. Such

has been our endeavour, and I think to a great extent we have been

successful. I may say that, although the central executive committee is

composed of men of most discordant opinions in politics and religion,

nothing for a single moment has interfered with the harmony ― I had almost

said with the unanimity ― of our proceedings. There has been nothing to

produce any painful feelings among us, nor any desire on the part of the

representatives of different districts to obtain an undue share for the

districts they represented from the common fund.

"But there are three points on which objection has being taken to the

course we have adopted. One has been, that the relief we have given has

not been given with a sufficiently liberal hand; the next ― and I think I

shall show you that these two are inconsistent, the one answering the

other ― is, that there has not been a sufficient pressure on the local

rates; and the third is, that Lancashire has not hitherto done its duty

with reference to the subscriptions from other parts of the country. Allow

me a few words on each of these subjects.

"First, the amount to which we have endeavoured to raise our subscriptions

has been to the extent of from two shillings to two shillings and sixpence

weekly per head; in this late cold weather an additional sixpence has been

provided, mainly for coal and clothing. Our endeavour has been to raise

the total income of each individual to at least two shillings or two

shillings and sixpence a week. Now, I am told that this is a very

inadequate amount, and no doubt it is an amount very far below that which

many of the recipients were in the habit of obtaining. But in the first

place, I think there is some misapprehension when we speak of the sum of

two shillings a week. If anybody supposes that two shillings a week is the

maximum to each individual, he will be greatly mistaken. Two shillings a

head per week is the sum we endeavoured to arrive at as the average

receipt of every man, woman, and child receiving assistance; consequently,

a man and his wife with a family of three or four small children would

receive, not two shillings, but ten or twelve shillings from the fund ― an

amount not far short of that which in prosperous times an honest and

industrious labourer in other parts of the country would obtain for the

maintenance of his family. I am not in the least afraid that, if we had

fixed the amount at four shillings or five shillings per head, such is the

liberality of the country, we should not have had sufficient means of

doing so. But were we justified in doing that? If we had raised their

income beyond that of the labouring man in ordinary times, we should have

gone far to destroy the most valuable feeling of the manufacturing

population ― namely, that of honest self-reliance, and we should have done

our best, to a great extent, to demoralise a large portion of the

population, and induce them to prefer the wages of charitable relief to

the return of honest industry. But then we are told that the rates are not

sufficiently high in the distressed districts, and that we ought to raise

them before we come on the fund. In the first place, we have no power to

compel the guardians to raise the rates beyond that which they think

sufficient for the maintenance of those to be relieved, and, naturally

considering themselves the trustees of the ratepayers, they are unwilling,

and, indeed, ought not to raise the amount beyond that which is called for

by absolute necessity. But suppose we had raised the relief from our

committee very far beyond the amount thought sufficient by the guardians,

what would have been the inevitable result? Why, that the rates which it

is desired to charge more heavily would have been relieved, because

persons would have taken themselves off the poor-rates, and placed

themselves on the charitable committee, and therefore the very object

these objectors have in view in calling for an increase of our donations

would have been defeated by their own measure. I must say, however,

honestly speaking all I feel, that, with regard to the amount of rates,

there are some districts which have applied to us for assistance which I

think have not sufficient pressure on their rates. Where I find, for

example, that the total assessment on the nett rateable value does not

exceed ninepence or tenpence in the pound, I really think such districts

ought to be called upon to increase their rates before applying for

extraneous help. But we have urged as far as we could urge ― we have no

power to command the guardians to be more liberal in the rate of relief,

and to that extent to raise the rates in their districts.

|

THE TIMES

7th Nov. 1862.

PRESTON.

On Wednesday

Mr. Manwaring, Poor Law Inspector, paid on official visit to Preston

to make inquiries respecting the existing distress in the township,

and the typhoid fever which has made its appearance, as well as the

means which are being adopted to prevent its spread. He had

long interviews with Mr. R. Ashcroft, Chairman of the Preston Board

of Guardians; Mr. Newton, borough surveyor; Dr. Bernard Haldan, one

of the medical inspectors of the Union, and other local authorities.

He inspected a plan which had been prepared by the borough engineer,

on the suggestion of Dr. Buchanan, of the medical department of the

Privy Council, for the erection of a fever ward adjacent to the

House of Recovery, which had been decided on by the Board of

Guardians, to be proceeded with without delay, at a cost of £150.

He was also informed of the means which had been put into operation

at the instance of the guardians and the Local Board of Health to

abate the fever; and, as the result of his inquiries, though the

proposed erection could be put up within a period of three days, he

expressed his opinion that even that delay would be dangerous, and

that premises must at once be procured in which the increasing

number of fever patients could be accommodated and properly attended

to.

The Board of Guardians have appointed Mr. Johnson, of

Blackburn, schoolmaster of the adult male paupers, and arranged that

he should commence his duties next Monday. 150 ablebodied men

are to be draughted from the Moor, and sent to the St. Peter's

school premises for education. They will allowed 6d. per day,

at the discretion of the guardians. Their present tickets will

be withdrawn, and new ones, adapted to the change, substituted.

The Board have also agreed, in committee, to extend the privileges

of the educational scheme to the Middleforth-green School,

Penwortham (an out-township of the Preston Union), the children of

the operatives attending it having latterly been unable to pay their

school fees through the stoppage of the Penwortham factory.

There are 186 girls attending the Leyland sewing school, and a

school is to be opened next Monday beneath the independent chapel

for the instruction of unemployed male operatives during three days

of the week. A sewing school was on Monday night opened under

the auspices of the Preston Church ladies, and attended by 91 girls;

and for the benefit of male factory operatives out of work, the

Temperance-hall, North-road, has been opened as a free reading room. |

"And now a word on the subject of raising rates, because I have received

many letters in which it has been said that the rates are nothing ― 'they

are only three shillings or four shillings in the pound, while we in the

agricultural districts are used to six shillings in the pound. We consider

that no extraordinary rate, and it is monstrous,' they say, 'that the

accumulated wealth of years in the county of Lancashire should not more

largely contribute to the relief of its own distress.' I will not enter

into an argument as to how far the larger amount of wages in the

manufacturing districts may balance the smaller amount of wages and the

larger amount of poor-rates in the agricultural districts. I don't wish to

enter into any comparison; I have seen many comparisons of this kind made,

but they were full of fallacies from one end to the other. I will not

waste your time by discussing them; but I ask you to consider the effect

of a sudden rise of rates as a charge upon the accumulated wealth of a

district. It is not the actual amount of the rates, but it is the sudden

and rapid increase of the usual rate of the rates that presses most

heavily on the ratepayers. In the long run, the rates must fall on real

property, because all bargains between owner and occupier are made with

reference to the amount of rates to be paid, and in all calculations

between them, that is an element which enters into the first agreement. But when the rate is suddenly increased from one shilling to four

shillings, it does not fall on the accumulated wealth or on the real

property, but it falls on the occupier, the ratepayer ― men, the great bulk

of whom are at the present moment themselves struggling upon the verge of

pauperism. Therefore, if in those districts it should appear to persons

accustomed to agricultural districts that the amount of our rates was very

small, I would say to them that any attempt to increase those rates would

only increase the pauperism, diminish the number of solvent ratepayers,

and greatly aggravate the distress. In some of the districts I think the

amount of the rates quite sufficient to satisfy the most ardent advocate

of high rates. For example, in the town of Ashton they have raised in the

course of the year one rate of one shilling and sixpence, another of one

shilling and six-pence, and a third of four shillings and sixpence, which

it is hoped will carry them over the year. They have also, in addition to

these rates, drawn largely on previous balances, and I am afraid have

largely added to their debt. The total of what has been or will be

expended, with a prospect of even a great increase, in that borough

exceeds eleven shillings and elevenpence in the pound for the relief of

the poor alone. And, gentlemen, this rate of four shillings and sixpence

about to be levied, which ought to yield about 32,000 pounds, it is

calculated will not yield 24,000 pounds. In Stockport the rate is even

higher, being twelve shillings or more per pound, and there it is

calculated that at the next levy the defalcations will be at least forty

per cent, according to the calculation of the poor-law commissioner

himself. To talk, then, of raising rates in such districts as these would

be absolute insanity; and even in districts less heavily rated, any sudden

attempt considerably to increase the rate would have the effect of

pauperising those who are now solvent, and to augment rather than diminish

the distress of the district.

"The last point on which I would make an observation relates to the

objection which has been taken to our proceedings, on the ground that

Lancashire has not done its duty in this distress, and that consequently

other parts of the country have been unduly called on to contribute to

that which I don't deny properly and primarily belongs to Lancashire.

Gentlemen, it is very hard to ascertain with any certainty what has been

done by Lancashire, because, in the first place, the amount of local

subscriptions and the amount of public contributions by themselves give no

fair indication of that which really has been done by public or private

charity. I don't mean to say that there are not individuals who have

grossly neglected their duty in Lancashire. On the other hand, we know

there are many, though I am not about to name them, who have acted with

the most princely munificence, liberality, and generous feeling, involving

an amount of sacrifice of which no persons out of this county can possibly

have the slightest conception. I am not saying there are not instances of

niggard feeling, though I am not about to name them, which really it was

hardly possible to believe could exist.

"Will you forgive me if I trespass for a few moments by reading two or

three extracts from confidential reports made to us every week from the

different districts by a gentleman whose services were placed at our

disposal by the Government? These reports being, as I have said,

confidential, I will not mention the names of the persons, firms, or

localities alluded to, though in some instances they may be guessed at. This report was made to us on the 25th of November, and I will quote some

of the remarks made in it. The writer observes: ―

'It must not be inferred when such

remarks are absent from the reports that nothing is done. I have

great difficulty sometimes in overcoming the feeling that my questions on

these points are a meddlesome interference in private matters.'

Bearing that remark in mind, I say here are instances which I am sure

reflect as much credit on the individuals as on the interest they

represent and the county to which they belong. I am sure I shall be

excused for trespassing on your patience by reading a few examples.

He says, under number: ―

1. ― 'Nearly three thousand operatives out of the whole, most of them

the hands of Messrs ― and Mr ― , at his own cost, employs five hundred

and fifty-five girls in sewing five days a week, paying them eightpence a

day; sends seventy-six youths from thirteen to fourteen years old, and

three hundred and thirty-two adults above fifteen, five days a week to

school, paying them from fourpence to eightpence per day, according to

age. He also pays the school pence of all the children. Mr

― has hitherto

paid his people two days' wages a week, but he is now preparing to adopt a

scheme like Mr ― to a great extent. I would add that, in addition to

wages, Mr ― gives bread, soup, socks, and clogs.

|

|

|

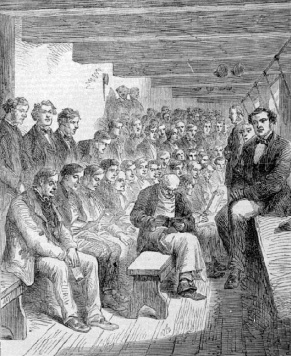

Literacy class, Stalybridge.

Illustrated London News. |

2. Mr ― has at his own expense caused fifty to sixty dinners to be

provided for sick persons every day. These consist of roast beef or

mutton, soup, beef-tea, rice-puddings, wine, and porter, as ordered; and

the forty visitors distribute orders as they find it necessary. Ostensibly

all is done in the name of the committee; but Mr ― pays all the cost. An

admirable soup kitchen is being fitted up, where the poor man may purchase

a good hot meal for one penny, and either carry it away or consume it on

the premises.

3. Messrs ― are giving to their hands three days' wages (about 500 pounds

a week.) Messrs ― and ― are giving their one hundred and twenty hands,

and Messrs their two hundred and thirty hands, two days' wages a week. I

may mention that Messrs ― are providing for all their one thousand seven

hundred hands.

4. A great deal of private charity exists, one firm having spent 1400

pounds in money, exclusive of weekly doles of bread.

5. Messrs ― are providing all their old hands with sufficient clothing

and bedding to supply every want, so that their subscription of 50 pounds

is merely nominal.

6. The ladies of the village visit and relieve privately with money, food,

or clothing, or all, if needed urgently. In a few cases distraint has been

threatened, but generally the poor are living rent free.

7. Payment of rent is almost unknown. The agent for several landlords

assures me he could not from his receipts pay the property-tax, but no distraints are made.

8. The bulk of the rents are not collected, and distraints are unknown.

9. The millowners are chiefly cottage-owners, and are asking for no

rents.'

|

BROOKLYN EAGLE

[U.S.A.]

8 November, 1862.

Mr. Milnes, M.P., on the American Question.

On the 21st a meeting of the inhabitants of Pontefract,

convened by requisition to the Mayor, was held in the Town Hall, for

the purpose of deciding what steps should be taken with the object

of contributing towards the fund for the relief of the distressed

Lancashire operatives. Resolutions in accordance with the

objects of the meeting were passed, and Mr. R. M. Milnes, M.P. was

one of the speakers. He remarked that it had been said that we

ought to recognise the Southern States of America, and go and get

our cotton at once. But the real objection to this course was

that we should not get the cotton. The reasons were twofold.

One was that the Southerners would withhold their produce, in the

hope that, by so doing, they would irritate this country more and

more against the Northern States. The other reason was, that

the blockade of the whole of the ports was a tolerably efficient

blockade, and this of itself would prevent any material bulk of

cotton coming out. If we were to recognize the Southern States

tomorrow, the blockade will still continue, and by the law of

nations we should have to declare war against the Northern States,

and thus add a fratricidal war to the calamities under which we are

already suffering. (Hear, hear.) Within the course of the next

few months some contingencies might occur by which some proportion

of this produce might come to these shores, and this he did not

think improbable. But it was better not to expect it; it was

preferable to look this evil fairly in the face; and he would tell

them why. Because if we looked for the cotton, week after week, the

question of relieving the national distress was kept in a continued

uncertainty. We must look forward, all this winter, to the

impossibility of again setting in work the great cotton

manufacturies of Lancashire and Cheshire. Nor would it be

advisable for the government to do more than they had done, until

they were compelled to do it. (Hear, hear.) If they were

compelled to do it, then these men in the cotton districts must not

die. (Applause.) This was the essential principle of the

English poor-law. |

"That leads me to call your attention to the fact that, in addition to the

sacrifices they are making, the millowners are themselves to a large

extent the owners of cottages, and I believe, without exception, they are

at the present moment receiving no rent, thereby losing a large amount of

income they had a right to count upon. I know one case which is curious as

showing how great is the difficulty of ascertaining what is really done.

It is required in the executive committee that every committee should send

in an account of the local subscriptions. We received an application from

a small district where there was one mill, occupied by some young men who

had just entered into the business. We returned a refusal, inasmuch as

there was no local subscription; but when we came to inquire, we found

that from last February, when the mill closed, these young men had

maintained the whole of their hands, that they paid one-third of the rates

of the whole district, and that they were at that moment suffering a

yearly loss of 300 pounds in the rent of cottages for which they were not

drawing a single halfpenny. That was a case in which we thought it right

in the first instance to withhold any assistance, because there appeared

to be no local subscription, and it shows how persons at a distance may be

deceived by the want apparently of any local subscription. But I will

throw out of consideration the whole of those amounts ― the whole of this

unparalleled munificence on the part of many manufacturers which never

appears in any account whatever ― I will throw out everything done in

private and unostentatious charity ― the supplies of bedding, clothing,

food, necessaries of every description, which do not appear as public

subscriptions, and will appeal to public subscriptions alone; and I will

appeal to an authority which cannot, I think, be disputed ― the authority

of the commissioner, Mr Farnall himself, whose services the Government

kindly placed at our disposal, and of whose activity, industry, and

readiness to assist us, it is difficult to speak in too high terms of

praise. A better authority could not be quoted on the subject of the

comparative support given in aid of this distress in Lancashire and other

districts. I find that, excluding altogether the subscriptions in the Lord

Mayor's Mansion House list ― of which we know the general amount, but not

the sources from which it is derived, or how it is expended ― but excluding

it from consideration, and dealing only with the funds which have been

given or promised to be administered through the central executive

committee, I find that, including some of the subscriptions which we know

are coming in this day, the total amount which has been contributed is

about 540,000 pounds. Of that amount we received ― and it is a most

gratifying fact ― 40,000 pounds from the colonies; we received from the

rest of the United Kingdom 100,000 pounds; and from the county of

Lancaster itself, in round numbers, 400,000 pounds out of 540,000 pounds.

|

TICKLE TIMES.

Neaw times are so tickle, no wonder

One's heart should be deawn i' his shoon,

But, dang it, we munnot knock under

To th' freawn o' misfortin to soon;

Though Robin looks fearfully gloomy,

An' Jamie keeps starin' at th' greawnd,

An' thinkin' o'th table 'at's empty,

An' th' little things yammerin' reawnd.

Iv a mon be both honest an' willin',

An' never a stroke to be had,

An' clemmin' for want ov a shillin', ―

It's likely to make him feel sad;

It troubles his heart to keep seein'

His little brids feedin' o'th air;

An' it feels very hard to be deein',

An' never a mortal to care.

But life's sich a quare bit o' travel, ―

A warlock wi' sun an' wi' shade, ―

An' then, on a bowster o' gravel,

They lay'n us i' bed wi' a spade;

It's no use o' peawtin' an' fratchin';

As th' whirligig's twirlin' areawn'd,

Have at it again; an' keep scratehin',

As lung as your yed's upo' greawnd.

Iv one could but feel i'th inside on't,

There's trouble i' every heart;

An' thoose that'n th' biggest o'th pride on't,

Oft leeten o'th keenest o'th smart.

Whatever may chance to come to us,

Let's patiently hondle er share, ―

For there's mony a fine suit o' clooas

That covers a murderin' care.

There's danger i' every station,

I'th palace, as weel as i'th cot;

There's hanker i' every condition,

An' canker i' every lot;

There's folk that are weary o' livin',

That never fear't hunger nor cowd;

An' there's mony a miserly crayter

'At's deed ov a surfeit o' gowd.

One feels, neaw 'at times are so nippin',

A mon's at a troublesome schoo',

That slaves like a horse for a livin',

An, flings it away like a foo;

But, as pleasur's sometimes a misfortin,

An' trouble sometimes a good thing, ―

Though we liv'n o'th floor, same as layrocks,

We'n go up, like layrocks, to sing.

EDWIN

WAUGH. |

"Now, I hope that these figures, upon the estimate and authority of the

Government poor-law commissioner, will be sufficient, at all events, to do

away with the imputation that Lancashire, at this crisis, is not doing its

duty. But if Lancashire has been doing its duty ― if it is doing its

duty ― that is no reason why Lancashire should relax its efforts; and of

that I trust the result of this day's proceedings will afford a sufficient

testimony. We are not yet at the height of the distress. It is estimated

that at the present moment there are three hundred and fifty-five thousand

persons engaged in the different manufactories. Of these forty thousand

only are in full work; one hundred and thirty-five thousand are at short

work, and one hundred and eighty thousand are out of work altogether. In

the course of the next six weeks this number is likely to be greatly

increased; and the loss of wages is not less than 137,000 pounds a week. This, I say then, is a state of things that calls for the most active

exertions of all classes of the community, who, I am happy to say, have

responded to the call which has been made upon them most nobly, from the

Queen down to the lowest individual in the community. At the commencement

of the distress, the Queen, with her usual munificence, sent us a donation

of 2,000 pounds. The first act of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales,

upon attaining his majority, was to write from Rome, and to request that

his name should be put down for 1,000 pounds. And to go to the other end of

the scale, I received two days ago, from Lord Shaftesbury, a donation of

1,200 pounds from some thousands of working men, readers of a particular

periodical which he mentioned, the British Workman. To that sum Lord Shaftesbury stated many thousands of persons had subscribed, and it

embraced contributions even from the brigade of shoe-black boys.

"On the part of all classes there has been the greatest liberality

displayed; and I should be unjust to the working men, I should be unjust

to the poor in every district, if I did not say that in proportion to

their means they have contributed more than their share. In no case hardly

which has come to my knowledge has there been any grudging, and in many

cases I know that poor persons have contributed more than common prudence

would have dictated. These observations have run to a greater extent than

I had intended; but I thought it desirable that the whole case, as far as

possible, should be brought before you, and I have only now earnestly to

request that you will this day do your part towards the furtherance of the

good work. I have no apprehension, if the distress should not last over

five or six months more, that the spontaneous efforts of individuals and

public bodies, and contributions received in every part of the country,

will fall short of that which is needed for enabling the population to

tide over this deep distress; and I earnestly hope that, if it be

necessary to apply to Parliament, as a last resource, the representatives

of the country will not grudge their aid; yet I do fervently hope and

believe that, with the assistance of the machinery of that bill passed in

Parliament last session, (the Rate in Aid Act,) which will come into

operation shortly after Christmas, but could not possibly be brought into

operation sooner, I do fervently hope and believe that this great

manufacturing district will be spared the further humiliation of coming

before Parliament, which ought to be the last resource, as a claimant, a

suppliant for the bounty of the nation at large. I don't apprehend that

there will be a single dissentient voice raised against the resolution

which I have now the honour to move."

____________________________________

FOOTNOTES.

1. These stanzas are extracted, by permission, from the

second volume of "Lancashire Lyrics," edited by John Harland, Esq., F.S.A.

"They were written by a lady in aid of the Relief Fund. They were

printed on a card, and sold, principally at the railway stations.

Their sale there, and elsewhere, is known to have realised the sum of 160

pounds. Their authoress is the wife of Mr Serjeant Bellasis, and the

only daughter of the late William Garnett, Esq. of Quernmore Park and

Bleasdale, Lancashire." ― Notes in "Lancashire Lyrics."

2. From "Lancashire Lyrics," edited by John Harland,

Esq., F.S.A.

3. Dole; relief from charity.

4. "During what has been well named 'The Cotton Famine,'

amongst the imports of cotton from India, perhaps the worst was that

denominated 'Surat,' from the city of that name in the province of Guzerat,

a great cotton district. Short in staple, and often rotten, bad in

quality, and dirty in condition, (the result too often of dishonest

packers,) it was found to be exceedingly difficult to work up; and from

its various defects, it involved considerable deductions, or 'batings,'

for bad work, from the spinners' and weavers' wages. This naturally

led to a general dislike of the Surat cotton, and to the application of

the word 'Surat' to designate any inferior article. One action was

tried at the assizes, the offence being the applying to the beverage of a

particular brewer the term of 'Surat beer.' Besides the song given

above, several others were written on the subject. One called 'Surat

Warps,' and said to be the production of a Rossendale rhymester, (T. N.,

of Bacup,) appeared in Notes and Queries of June 3, 1865, (third

series, vol. vii., p. 432,) and is there stated to be a great favourite

amongst the old 'Deyghn Layrocks,' (Anglice, the 'Larks of Dean,' in the

forest of Rossendale,) 'who sing it to one of the easy-going psalm-tunes

with much gusto.' One verse runs thus: ―

" 'I look at th' yealds, and there they stick;

I ne'er seen the like sin' I wur wick!

What pity could befall a heart,

To think about these hard-sized warps!' |

Another song, called 'The Surat Weyver,' was written by

William Billington of Blackburn.

It is in the form of a lament by a body of Lancashire weavers, who declare

that they had

" 'Borne what mortal man could bear,

Affoore they'd weave Surat.' |

But they had been compelled to weave it, though

" 'Stransportashun's not as ill

As weyvin rotten Su'.' |

The song concludes with the emphatic execration,

" 'To hell wi' o' Surat!'"

― Note in "Lancashire Lyrics," vol. ii., edited by John Harland, Esq.,

F.S.A.

5. These beautiful lines, by the veteran

Samuel Bamford, of Harperhey, near

Manchester, author of "Passages

in the Life of a Radical," &c., are copied from the new and complete

edition of his poems, entitled "Homely

Rhymes, Poems, and Reminiscences," published by Alexander Ireland &

Co., Examiner and Times Office, Pall Mall, Manchester. Price 3s.

6d., with a portrait of the author. |

.htm_cmp_poetic110_bnr.gif)