|

SELF-HELP, &c.

__________

CHAPTER I.

SELF-HELP—NATIONAL

AND INDIVIDUAL.

"The worth of a State, in the long

run, is the worth of the individuals composing it."—J. S. Mill.

"We put too much faith in systems, and look too little to

men."—B. Disraeli. |

"HEAVEN helps

those who help themselves" is a well-tried maxim, embodying in a

small compass the results of vast human experience. The spirit

of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual;

and, exhibited in the lives of many, it constitutes the true source

of national vigour and strength. Help from without is often

enfeebling in its effects, but help from within invariably

invigorates. Whatever is done for men or classes, to a certain

extent takes away the stimulus and necessity of doing for

themselves; and where men are subjected to over-guidance and

over-government, the inevitable tendency is to render them

comparatively helpless.

Even the best institutions can give a man no active help.

Perhaps the most they can do is, to leave him free to develop

himself and improve his individual condition. But in all times

men have been prone to believe that their happiness and well-being

were to be secured by means of institutions rather than by their own

conduct. Hence the value of legislation as an agent in human

advancement has usually been much over-estimated. To

constitute the millionth part of a Legislature, by voting for one or

two men once in three or five years, however conscientiously this

duty may be performed, can exercise but little active influence upon

any man's life and character. Moreover, it is becoming more

clearly understood, that the function of Government is negative and

restrictive, rather than positive and active; being resolvable

principally into protection—protection of life, liberty, and

property. Laws, wisely administered, will secure men in the

enjoyment of the fruits of their labour, whether of mind or body, at

a comparatively small personal sacrifice; but no laws, however

stringent, can make the idle industrious, the thriftless provident,

or the drunken sober. Such reforms can only be effected by

means of individual action, economy, and self-denial; by better

habits, rather than by greater rights.

The Government of a nation itself is usually found to be but

the reflex of the individuals composing it. The Government

that is ahead of the people will inevitably be dragged down to their

level, as the Government that is behind them will in the long run be

dragged up. In the order of nature, the collective character

of a nation will as surely find its befitting results in its law and

government, as water finds its own level. The noble people

will be nobly ruled, and the ignorant and corrupt ignobly.

Indeed all experience serves to prove that the worth and strength of

a State depend far less upon the form of its institutions than upon

the character of its men. For the nation is only an aggregate

of individual conditions, and civilization itself is but a question

of the personal improvement of the men, women, and children of whom

society is composed.

National progress is the sum of individual industry, energy,

and uprightness, as national decay is of individual idleness,

selfishness, and vice. What we are accustomed to decry as

great social evils, will, for the most part, be found to be but the

outgrowth of man's own perverted life; and though we may endeavour

to cut them down and extirpate them by means of Law, they will only

spring up again with fresh luxuriance in some other form, unless the

conditions of personal life and character are radically improved.

If this view be correct, then it follows that the highest patriotism

and philanthropy consist, not so much in altering laws and modifying

institutions, as in helping and stimulating men to elevate and

improve themselves by their own free and independent individual

action.

It may be of comparatively little consequence how a man is

governed from without, whilst everything depends upon how he governs

himself from within. The greatest slave is not he who is ruled

by a despot, great though that evil be, but he who is the thrall of

his own moral ignorance, selfishness, and vice. Nations who

are thus enslaved at heart cannot be freed by any mere changes of

masters or of institutions; and so long as the fatal delusion

prevails, that liberty solely depends upon and consists in

government, so long will such changes, no matter at what cost they

may be effected, have as little practical and lasting result as the

shifting of the figures in a phantasmagoria. The solid

foundations of liberty must rest upon individual character; which is

also the only sure guarantee for social security and national

progress. John Stuart Mill truly observes that "even despotism

does not produce its worst effects so long as individuality exists

under it; and whatever crushes individuality is despotism, by

whatever name it be called."

Old fallacies as to human progress are constantly turning up.

Some call for Cæsars, others for Nationalities, and others for Acts

of Parliament. We are to wait for Cæsars, and when they are

found, "happy the people who recognise and follow them." [p.4]

This doctrine shortly means, everything for the people,

nothing by them,—a doctrine which, if taken as a guide, must,

by destroying the free conscience of a community, speedily prepare

the way for any form of despotism. Cæsarism is human idolatry

in its worst form—a worship of mere power, as degrading in its

effects as the worship of mere wealth would be. A far

healthier doctrine to inculcate among the nations would be that of

Self-Help; and so soon as it is thoroughly understood and carried

into action, Cæsarism will be no more. The two principles are

directly antagonistic; and what Victor Hugo said of the Pen and the

Sword alike applies to them, "Ceci tuera cela." [This will kill

that.]

The power of Nationalities and Acts of Parliament is also a

prevalent superstition. What William Dargan, one of Ireland's

truest patriots, said at the closing of the first Dublin Industrial

Exhibition, may well be quoted now. "To tell the truth," he

said, "I never heard the word independence mentioned that my own

country and my own fellow townsmen did not occur to my mind. I

have heard a great deal about the independence that we were to get

from this, that, and the other place, and of the great expectations

we were to have from persons from other countries coming amongst us.

Whilst I value as much as any man the great advantages that must

result to us from that intercourse, I have always been deeply

impressed with the feeling that our industrial independence is

dependent upon ourselves. I believe that with simple industry

and careful exactness in the utilization of our energies, we never

had a fairer chance nor a brighter prospect than the present.

We have made a step, but perseverance is the great agent of success;

and if we but go on zealously, I believe in my conscience that in a

short period we shall arrive at a position of equal comfort, of

equal happiness, and of equal independence, with that of any other

people."

All nations have been made what they are by the thinking and

the working of many generations of men. Patient and

persevering labourers in all ranks and conditions of life,

cultivators of the soil and explorers of the mine, inventors and

discoverers, manufacturers, mechanics and artisans, poets,

philosophers, and politicians, all have contributed towards the

grand result, one generation building upon another's labours, and

carrying them forward to still higher stages. This constant

succession of noble workers—the artisans of civilisation—has served

to create order out of chaos in industry, science, and art; and the

living race has thus, in the course of nature, become the inheritor

of the rich estate provided by the skill and industry of our

forefathers, which is placed in our hands to cultivate, and to hand

down, not only unimpaired but improved, to our successors.

The spirit of self-help, as exhibited in the energetic action

of individuals, has in all times been a marked feature in the

English character, and furnishes the true measure of our power as a

nation. Rising above the heads of the mass, there were always

to be found a series of individuals distinguished beyond others, who

commanded the public homage. But our progress has also been

owing to multitudes of smaller and less known men. Though only

the generals' names may be remembered in the history of any great

campaign, it has been in a great measure through the individual

valour and heroism of the privates that victories have been won.

And life, too, is "a soldiers' battle,"—men in the ranks having in

all times been amongst the greatest of workers. Many are the

lives of men unwritten, which have nevertheless as powerfully

influenced civilisation and progress as the more fortunate Great

whose names are recorded in biography. Even the humblest

person, who sets before his fellows an example of industry,

sobriety, and upright honesty of purpose in life, has a present as

well as a future influence upon the well-being of his country; for

his life and character pass unconsciously into the lives of others,

and propagate good example for all time to come.

Daily experience shows that it is energetic individualism

which produces the most powerful effects upon the life and action of

others, and really constitutes the best practical education.

Schools, academies, and colleges, give but the merest beginnings of

culture in comparison with it. Far more influential is the

life-education daily given in our homes, in the streets, behind

counters, in workshops, at the loom and the plough, in

counting-houses and manufactories, and in the busy haunts of men.

This is that finishing instruction as members of society, which

Schiller designated "the education of the human race," consisting in

action, conduct, self-culture, self-control,—all that tends to

discipline a man truly, and fit him for the proper performance of

the duties and business of life,—a kind of education not to be

learnt from books, or acquired by any amount of mere literary

training. With his usual weight of words Bacon observes, that

"Studies teach not their own use; but that is a wisdom without them,

and above them, won by observation;" a remark that holds true of

actual life, as well as of the cultivation of the intellect itself.

For all experience serves to illustrate and enforce the lesson, that

a man perfects himself by work more than by reading,—that it is life

rather than literature, action rather than study, and character

rather than biography, which tend perpetually to renovate mankind.

Biographies of great, but especially of good men, are

nevertheless most instructive and useful, as helps, guides, and

incentives to others. Some of the best are almost equivalent

to gospels—teaching high living, high thinking, and energetic action

for their own and the world's good. The valuable examples

which they furnish of the power of self-help, of patient purpose,

resolute working, and steadfast integrity, issuing in the formation

of truly noble and manly character, exhibit in language not to be

misunderstood, what it is in the power of each to accomplish for

himself; and eloquently illustrate the efficacy of self-respect and

self-reliance in enabling men of even the humblest rank to work out

for themselves an honourable competency and a solid reputation.

Great men of science, literature, and art—apostles of great

thoughts and lords of the great heart—have belonged to no exclusive

class nor rank in life. They have come alike from colleges,

workshops, and farmhouses,—from the huts of poor men and the

mansions of the rich. Some of God's greatest apostles have

come from "the ranks." The poorest have sometimes taken the

highest places; nor have difficulties apparently the most

insuperable proved obstacles in their way. Those very

difficulties, in many instances, would even seem to have been their

best helpers, by evoking their powers of labour and endurance, and

stimulating into life faculties which might otherwise have lain

dormant. The instances of obstacles thus surmounted, and of

triumphs thus achieved, are indeed so numerous, as almost to justify

the proverb that "with Will one can do anything." Take, for

instance, the remarkable fact, that from the barber's shop came

Jeremy Taylor, the most poetical of divines;

Sir Richard Arkwright,

the inventor of the spinning-jenny and founder of the cotton

manufacture; Lord Tenterden, one of the most distinguished of Lord

Chief justices; and Turner, the greatest among landscape painters.

No one knows to a certainty what Shakespeare was; but it is

unquestionable that he sprang from a humble rank. His father

was a butcher and grazier; and Shakespeare himself is supposed to

have been in early life a wool-comber; whilst others aver that he

was an usher in a school and afterwards a scrivener's clerk.

He truly seems to have been "not one, but all mankind's epitome."

For such is the accuracy of his sea phrases that a naval writer

alleges that he must have been a sailor; whilst a clergyman infers,

from internal evidence in his writings, that he was probably a

parson's clerk; and a distinguished judge of horse-flesh insists

that he must have been a horse-dealer. Shakespeare was

certainly an actor, and in the course of his life "played many

parts," gathering his wonderful stores of knowledge from a wide

field of experience and observation. In any event, he must

have been a close student and a hard worker; and to this day his

writings continue to exercise a powerful influence on the formation

of English character.

|

|

|

HUGH

MILLER

(1802-56):

self-taught Scottish geologist and

writer. |

The common class of day labourers has given us

Brindley the engineer, Cook the

navigator, and Burns the poet. Masons and bricklayers can

boast of Ben Jenson, who worked at the building of Lincoln's Inn,

with a trowel in his hand and a book in his pocket, Edwards and

Telford the engineers,

Hugh Miller the geologist, and

Allan Cunningham the writer and sculptor; whilst among distinguished

carpenters we find the names of Inigo Jones the architect,

Harrison the chronometer-maker, John

Hunter the physiologist, Romney and Opie the painters, Professor Lee

the Orientalist, and John Gibson the sculptor.

From the weaver class have sprung Simson the mathematician,

Bacon the sculptor, the two Milners, Adam Walker, John Foster,

Wilson the ornithologist, Dr. Livingstone the missionary traveller,

and Tannahill the poet. Shoemakers have given us Sir

Cloudesley Shovel the great Admiral, Sturgeon the electrician,

Samuel Drew the essayist, Gifford the editor of the 'Quarterly

Review,' Bloomfield the poet, and William Carey the missionary;

whilst Morrison, another laborious missionary, was a maker of

shoe-lasts. Within the last few years, a profound naturalist

has been discovered in the person of a shoemaker at Banff, named

Thomas Edwards, who, while maintaining himself by his trade, has

devoted his leisure to the study of natural science in all its

branches, his researches in connexion with the smaller crustaceæ

having been rewarded by the discovery of a new species, to which the

name of "Praniza Edwardsii" has been given by naturalists.

Nor have tailors been undistinguished. John Stow, the

historian, worked at the trade during some part of his life.

Jackson, the painter, made clothes until he reached manhood.

The brave Sir John Hawkswood, who so greatly distinguished himself

at Poictiers, and was knighted by Edward III. for his valour, was in

early life apprenticed to a London tailor. Admiral Hobson, who

broke the boom at Vigo in 1702, belonged to the same calling.

He was working as a tailor's apprentice near Bonchurch, in the Isle

of Wight, when the news flew through the village that a squadron of

men-of-war was sailing off the island. He sprang from the

shopboard, and ran down with his comrades to the beach, to gaze upon

the glorious sight. The boy was suddenly inflamed with the

ambition to be a sailor; and springing into a boat, he rowed off to

the squadron, gained the admiral's ship, and was accepted as a

volunteer. Years after, he returned to his native village full

of honours, and dined off bacon and eggs in the cottage where he had

worked as an apprentice. But the greatest tailor of all is

unquestionably Andrew Johnson, the present President of the United

States—a man of extraordinary force of character and vigour of

intellect. In his great speech at Washington, when describing

himself as having begun his political career as an alderman, and run

through all the branches of the legislature, a voice in the crowd

cried, "From a tailor up." It was characteristic of Johnson to

take the intended sarcasm in good part, and even to turn it to

account. "Some gentleman says I have been a tailor. That

does not disconcert me in the least; for when I was a tailor I had

the reputation of being a good one, and making close fits; I was

always punctual with my customers, and always did good work."

GEORGE

STEPHENSON

(1781-1848):

English civil and mechanical engineer.

Cardinal Wolsey, De Foe, Akenside, and Kirke White were the

sons of butchers; Bunyan was a tinker, and Joseph Lancaster a

basket-maker. Among the great names identified with the

invention of the steam-engine are those of Newcomen,

Watt, and

Stephenson; the first a blacksmith,

the second a maker of mathematical instruments, and the third an

engine-fireman. Huntingdon the preacher was originally a

coal-heaver, and Bewick, the father of wood-engraving, a coalminer.

Dodsley was a footman, and Holcroft a groom. Baffin the

navigator began his seafaring career as a man before the mast, and

Sir Cloudesley Shovel as a cabin-boy. Herschel played the oboe

in a military band.

Chantrey was a journeyman carver, Etty a journeyman printer, and

Sir Thomas Lawrence the son of a tavern-keeper.

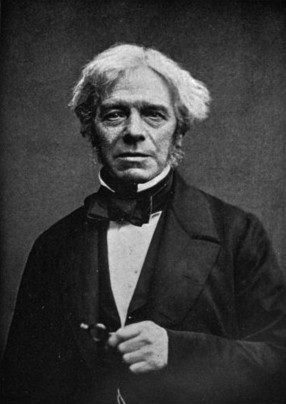

Michael Faraday,

the son of a blacksmith, was in early life apprenticed to a

bookbinder, and worked at that trade until he reached his

twenty-second year: he now occupies the very first rank as a

philosopher, excelling even his master,

Sir Humphry Davy, in the

art of lucidly expounding the most difficult and abstruse points in

natural science.

|

|

|

MICHAEL

FARADAY

(1791-1867)

English chemist and physicist.

Picture: Wikipedia. |

Among those who have given the greatest impulse to the sublime

science of astronomy, we find Copernicus, the son of a Polish baker;

Kepler, the son of a German public-house keeper, and himself the "garçon

de cabaret;" d'Alembert, a foundling picked up one winter's night on

the steps of the church of St. Jean le Rond at Paris, and brought up

by the wife of a glazier; and

Newton and Laplace,

the one the son of a small freeholder near Grantham, the other the

son of a poor peasant of Beaumont-en-Auge, near Honfleur.

Notwithstanding their comparatively adverse circumstances in early

life, these distinguished men achieved a solid and enduring

reputation by the exercise of their genius, which all the wealth in

the world could not have purchased. The very possession of

wealth might indeed have proved an obstacle greater even than the

humble means to which they were born. The father of Lagrange,

the astronomer and mathematician, held the office of Treasurer of

War at Turin; but having ruined himself by speculations, his family

were reduced to comparative poverty. To this circumstance

Lagrange was in after life accustomed partly to attribute his own

fame and happiness. "Had I been rich," said he, "I should

probably not have become a mathematician."

The sons of clergymen and ministers of religion generally,

have particularly distinguished themselves in our country's history.

Amongst them we find the names of Drake and Nelson, celebrated in

naval heroism; of Wollaston, Young, Playfair, and Bell, in science;

of Wren, Reynolds, Wilson, and Wilkie, in art; of Thurlow and

Campbell, in law; and of Addison, Thomson, Goldsmith, Coleridge, and

Tennyson, in literature. Lord Hardinge, Colonel Edwardes, and

Major Hodson, so honourably known in Indian warfare, were also the

sons of clergymen. Indeed, the empire of England in India was

won and held chiefly by men of the middle class—such as Clive,

Warren Hastings, and their successors—men for the most part bred in

factories and trained to habits of business.

Among the sons of attorneys we find Edmund Burke,

Smeaton the engineer, Scott

and Wordsworth, and Lords Somers, Hardwick, and Dunning. Sir

William Blackstone was the posthumous son of a silk-mercer.

Lord Gifford's father was a grocer at Dover; Lord Denman's a

physician; Judge Talfourd's a country brewer; and Lord Chief Baron

Pollock's a celebrated saddler at Charing Cross. Layard, the

discoverer of the monuments of Nineveh, was an articled clerk in a

London solicitor's office; and Sit William Armstrong, the inventor

of hydraulic machinery and of the Armstrong ordnance, was also

trained to the law and practised for some time as an attorney.

Milton was the son of a London scrivener, and Pope and Southey were

the sons of linen drapers. Professor Wilson was the son of a

Paisley manufacturer, and Lord Macaulay of an African merchant.

Keats was a druggist, and

Sir Humphry Davy a country apothecary's apprentice.

Speaking of himself, Davy once said, "What I am I have made myself:

I say this without vanity, and in pure simplicity of heart."

Richard Owen, the Newton of Natural History, began life as a

midshipman, and did not enter upon the line of scientific research

in which he has since become so distinguished, until comparatively

late in life. He laid the foundations of his great knowledge

while occupied in cataloguing the magnificent museum accumulated by

the industry of John Hunter, a work which occupied him at the

College of Surgeons during a period of about ten years.

Foreign not less than English biography abounds in

illustrations of men who have glorified the lot of poverty by their

labours and their genius. In Art we find Claude, the son of a

pastry cook; Geefs, of a baker; Leopold Robert, of a watchmaker; and

Haydn, of a wheelwright; whilst Daguerre was a scene-painter at the

Opera. The father of Gregory VII. was a carpenter; of Sextus

V., a shepherd; and of Adrian VI., a poor bargeman. When a

boy, Adrian, unable to pay for a light by which to study, was

accustomed to prepare his lessons by the light of the lamps in the

streets and the church porches, exhibiting a degree of patience and

industry which were the certain forerunners of his future

distinction. Of like humble origin were Hauy, the

mineralogist, who was the son of a weaver of Saint-Just;

Hautefeuille, the mechanician, of a baker at Orleans; Joseph

Fourier, the mathematician, of a tailor at Auxerre; Dui and, the

architect, of a Paris shoemaker; and Gesner, the naturalist, of a

skinner or worker in hides, at Zurich. This last began his

career under all the disadvantages attendant on poverty, sickness,

and domestic calamity; none of which, however, were sufficient to

damp his courage or hinder his progress. His life was indeed

an eminent illustration of the truth of the saying, that those who

have most to do and are willing to work, will find the most time.

Pierre Ramus was another man of like character. He was the son

of poor parents in Picardy, and when a boy was employed to tend

sheep. But not liking the occupation he ran away to Paris.

After encountering much misery, he succeeded in entering the College

of Navarre as a servant. The situation, however, opened for

him the road to learning, and he shortly became one of the most

distinguished men of his time.

The chemist Vauquelin was the son of a peasant of Saint

André-d'Herbetot, in the Calvados. When a boy at school,

though poorly clad, he was full of bright intelligence; and the

master, who taught him to read and write, when praising him for his

diligence, used to say, "Go on, my boy; work, study, Colin, and one

day you will go as well dressed as the parish churchwarden!" A

country apothecary who visited the school, admired the robust boy's

arms, and offered to take him into his laboratory to pound his

drugs, to which Vauquelin assented, in the hope of being able to

continue his lessons. But the apothecary would not permit him

to spend any part of his time in learning; and on ascertaining this,

the youth immediately determined to quit his service. He

therefore left Saint-André and took the road for Paris with his

haversack on his back. Arrived there, he searched for a place

as apothecary's boy, but could not find one. Worn out by

fatigue and destitution, Vauquelin fell ill, and in that state was

taken to the hospital, where he thought he should die. But

better things were in store for the poor boy. He recovered,

and again proceeded in his search of employment, which he at length

found with an apothecary. Shortly after, he became known to

Fourcroy the eminent chemist, who was so pleased with the youth that

he made him his private secretary; and many years after, on the

death of that great philosopher, Vauquelin succeeded him as

Professor of Chemistry. Finally, in 1829, the electors of the

district of Calvados appointed him their representative in the

Chamber of Deputies, and he re-entered in triumph the village which

he had left so many years before, so poor and so obscure.

England has no parallel instances to show, of promotions from

the ranks of the army to the highest military offices, which have

been so common in France since the first Revolution. "La

carrière ouverte aux talents" has there received many striking

illustrations, which would doubtless be matched among ourselves were

the road to promotion as open. Hoche, Humbert, and Pichegru,

began their respective careers as private soldiers. Hoche,

while in the King's army, was accustomed to embroider waistcoats to

enable him to earn money wherewith to purchase books on military

science. Humbert was a scapegrace when a youth; at sixteen he

ran away from home, and was by turns servant to a tradesman at

Nancy, a workman at Lyons, and a hawker of rabbit skins. In

1792, he enlisted as a volunteer; and in a year he was general of

brigade. Kleber, Lefèvre, Suchet, Victor, Lannes, Soult,

Massena, St. Cyr, D'Erlon, Murat, Augereau, Bessières, and Ney, all

rose from the ranks. In some cases promotion was rapid, in

others it was slow. Saint Cyr, the son of a tanner of Toul,

began life as an actor, after which he enlisted in the Chasseurs,

and was promoted to a captaincy within a year. Victor, Due de

Belluno, enlisted in the Artillery in 1781: during the events

preceding the Revolution he was discharged; but immediately on the

outbreak of war he re-enlisted, and in the course of a few months

his intrepidity and ability secured his promotion as Adjutant-Major

and chief of batallion. Murat, "le beau sabreur," was the son

of a village innkeeper in Perigord, where he looked after the

horses. He first enlisted in a regiment of Chasseurs, from

which he was dismissed for insubordination; but again enlisting, he

shortly rose to the rank of Colonel. Ney enlisted at eighteen

in a hussar regiment, and gradually advanced step by step: Kleber

soon discovered his merits, surnaming him "The Indefatigable," and

promoted him to be Adjutant-General when only twenty-five. On

the other hand, Soult [p.15]

was six years from the date of his enlistment before he reached the

rank of sergeant. But Soult's advancement was rapid compared

with that of Massena, who served for fourteen years before he was

made sergeant; and though he afterwards rose successively, step by

step, to the grades of Colonel, General of Division, and Marshal, he

declared that the post of sergeant was the step which of all others

had cost him the most labour to win. Similar promotions from

the ranks, in the French army, have continued down to our own day.

Changarnier entered the King's bodyguard as a private in 1815.

Marshal Bugeaud served four years in the ranks, after which he was

made an officer. Marshal Randon, the present French Minister

of War, began his military career as a drummer boy; and in the

portrait of him in the gallery at Versailles, his hand rests upon a

drum-head, the picture being thus painted at his own request.

Instances such as these inspire French soldiers with enthusiasm for

their service, as each private feels that he may possibly carry the

baton of a marshal in his knapsack.

The instances of men, in this and other countries, who, by

dint of persevering application and energy, have raised themselves

from the humblest ranks of industry to eminent positions of

usefulness and influence in society, are indeed so numerous that

they have long ceased to be regarded as exceptional. Looking

at some of the more remarkable, it might almost be said that early

encounter with difficulty and adverse circumstances was the

necessary and indispensable condition of success. The British

House of Commons has always contained a considerable number of such

self-raised men—fitting representatives of the industrial character

of the people; and it is to the credit of our Legislature that they

have been welcomed and honoured there. When the late Joseph

Brotherton, member for Salford, in the course of the discussion on

the Ten Hours Bill, detailed with true pathos the hardships and

fatigues to which he had been subjected when working as a factory

boy in a cotton mill, and described the resolution which he had then

formed, that if ever it was in his power he would endeavour to

ameliorate the condition of that class; Sir James Graham rose

immediately after him, and declared, amidst the cheers of the House,

that he did not before know that Mr. Brotherton's origin had been so

humble, but that it rendered him more proud than he had ever before

been of the House of Commons, to think that a person risen from that

condition should be able to sit side by side, on equal terms, with

the hereditary gentry of the land.

The late Mr. Fox, member for Oldham, was accustomed to

introduce his recollections of past times with the words, "when I

was working as a weaver boy at Norwich;" and there are other members

of parliament, still living, whose origin has been equally humble.

Mr. Lindsay, the well-known ship owner, until recently member for

Sunderland, once told the simple story of his life to the electors

of Weymouth, in answer to an attack made upon him by his political

opponents. He had been left an orphan at fourteen, and when he

left Glasgow for Liverpool to push his way in the world, not being

able to pay the usual fare, the captain of the steamer agreed to

take his labour in exchange, and the boy worked his passage by

trimming the coals in the coal hole. At Liverpool he remained

for seven weeks before he could obtain employment, during which time

he lived in sheds and fared hardly; until at last he found shelter

on board a West Indiaman. He entered as a boy, and before he

was nineteen, by steady good conduct he had risen to the command of

a ship. At twenty-three lie retired from the sea, and settled on

shore, after which his progress was rapid: "he had prospered," he

said, "by steady industry, by constant work, and by ever keeping in

view the great principle of doing to others as you would be done

by."

The career of Mr. William Jackson, of Birkenhead, the present

member for North Derbyshire, bears considerable resemblance to that

of Mr. Lindsay. His father, a surgeon at Lancaster, died,

leaving a family of eleven children, of whom William Jackson was the

seventh son. The elder boys had been well educated while the

father lived, but at his death the younger members had to shift for

themselves. William, when under twelve years old, was taken

from school, and put to hard work at a ship's side from six in the

morning till nine at night. His master falling ill, the boy

was taken into the counting-house, where he had more leisure.

This gave him an opportunity of reading, and having obtained access

to a set of the 'Encyclopædia Britannica,' he read the volumes

through from A to Z, partly by day, but chiefly at night. He

afterwards put himself to a trade, was diligent, and succeeded in

it. Now he has ships sailing on almost every sea, and holds

commercial relations with nearly every country on the globe.

|

|

|

RICHARD

COBDEN

(1804-65):

English manufacturer and Radical. |

Among like men of the same class may be ranked the late Richard

Cobden, whose start in life was equally humble. The son of a

small farmer at Midhurst in Sussex, he was sent at an early age to

London and employed as a boy in a warehouse in the City. He

was diligent, well conducted, and eager for information. His

master, a man the old school, warned him against too much reading;

but the boy went on in his own course, storing his mind with the

wealth found in books. He was promoted from one position of

trust to another—became a traveller for his house—secured a large

connection, and eventually started in business as a calico printer

at Manchester. Taking an interest in public questions, more

especially in popular education, his attention was gradually drawn

to the subject of the Corn Laws, to the repeal of which he may be

said to have devoted his fortune and his life. It may be

mentioned as a curious fact that the first speech he delivered in

public was a total failure. But he had great perseverance,

application, and energy; and with persistency and practice, he

became at length one of the most persuasive and effective of public

speakers, extorting the disinterested eulogy of even Sir Robert Peel

himself. M. Drouyn de Lhuys, the French Ambassador, has

eloquently said of Mr. Cobden, that he was "a living proof of what

merit, perseverance, and labour can accomplish; one of the most

complete examples of those men who, sprung from the humblest ranks

of society, raise themselves to the highest rank in public

estimation by the effect of their own worth and of their personal

services; finally, one of the rarest examples of the solid qualities

inherent in the English character."

In all these cases, strenuous individual application was the

price paid for distinction; excellence of any sort being invariably

placed beyond the reach of indolence. It is the diligent hand

and head alone that maketh rich—in self culture, growth in wisdom,

and in business. Even when men are born to wealth and high

social position, any solid reputation which they may individually

achieve can only be attained by energetic application; for though an

inheritance of acres may be bequeathed, an inheritance of knowledge

and wisdom cannot. The wealthy man may pay others for doing

his work for him, but it is impossible to get his thinking done for

him by another, or to purchase any kind of self-culture.

Indeed, the doctrine that excellence in any pursuit is only to be

achieved by laborious application, holds as true in the case of the

man of wealth as in that of Drew and Gifford, whose only school was

a cobbler's stall, or Hugh Miller, whose only college was a Cromarty

stone quarry.

Riches and ease, it is perfectly clear, are not necessary for

man's highest culture, else had not the world been so largely

indebted in all times to those who have sprung from the humbler

ranks. An easy and luxurious existence does not train men to

effort or encounter with difficulty; nor does it awaken that

consciousness of power which is so necessary for energetic and

effective action in life. Indeed, so far from poverty being a

misfortune, it may, by vigorous self-help, be converted even into a

blessing; rousing a man to that struggle with the world in which,

though some may purchase ease by degradation, the right-minded and

true-hearted find strength, confidence, and triumph. Bacon

says, "Men seem neither to understand their riches nor their

strength: of the former they believe greater things than they

should; of the latter much less. Self-reliance and self-denial

will teach a man to drink out of his own cistern, and eat his own

sweet bread, and to learn and labour truly to get his living, and

carefully to expend the good things committed to his trust."

Riches are so great a temptation to ease and self-indulgence,

to which men are by nature prone, that the glory is all the greater

of those who, born to ample fortunes, nevertheless take an active

part in the work of their generation—who "scorn delights and live

laborious days." It is to the honour of the wealthier ranks in

this country that they are not idlers; for they do their fair share

of the work of the state, and usually take more than their fair

share of its dangers. It was a fine thing said of a subaltern

officer in the Peninsular campaigns, observed trudging alone through

mud and mire by the side of his regiment, "There goes £15,000

a-year!" and in our own day, the bleak slopes of Sebastopol and the

burning soil of India have borne witness to the like noble

self-denial and devotion on the part of our gentler classes; many a

gallant and noble fellow, of rank and estate, having risked his

life, or lost it, in one or other of those fields of action, in the

service of his country.

Nor have the wealthier classes been undistinguished in the

more peaceful pursuits of philosophy and science. Take, for

instance, the great names of Bacon, the father of modern philosophy,

and of Worcester, Boyle, Cavendish, Talbot, and Rosse, in science.

The last named may be regarded as the great mechanic of the peerage;

a man who, if he had not been born a peer, would probably have taken

the highest rank as an inventor. So thorough is his knowledge

of smith-work that he is said to have been pressed on one occasion

to accept the foremanship of a large workshop, by a manufacturer to

whom his rank was unknown. The great Rosse telescope, of his

own fabrication, is certainly the most extraordinary instrument of

the kind that has yet been constructed.

|

|

|

WILLIAM

EWART GLADSTONE

(1809-98)

English Liberal statesman;

four times Prime Minister.

Picture: Project Gutenberg. |

BENJAMIN

DISRAELI

(1804-81)

English Conservative Statesman;

twice Prime Minister.

Picture: Project Gutenberg. |

But it is principally in the departments of politics and

literature that we find the most energetic labourers amongst our

higher classes. Success in these lines of action, as in all

others, can only be achieved through industry, practice, and study;

and the great Minister, or parliamentary leader, must necessarily be

amongst the very hardest of workers. Such was Palmerston; and

such are Derby and Russell, Disraeli and Gladstone. These men

have had the benefit of no Ten Hours Bill, but have often, during

the busy season of Parliament, worked "double shift," almost day and

night. One of the most illustrious of such workers in modern

times was unquestionably the late Sir Robert Peel. He

possessed in an extraordinary degree the power of continuous

intellectual labour, nor did he spare himself. His career,

indeed, presented a remarkable example of how much a man of

comparatively moderate powers can accomplish by means of assiduous

application and indefatigable industry. During the forty years

that he held a seat in Parliament, his labours were prodigious.

He was a most conscientious man, and whatever he undertook to do, he

did thoroughly. All his speeches bear evidence of his careful

study of everything that had been spoken or written on the subject

under consideration. He was elaborate almost to excess; and

spared no pains to adapt himself to the various capacities of his

audience. Withal, he possessed much practical sagacity, great

strength of purpose, and power to direct the issues of action with

steady hand and eye. In one respect he surpassed most men: his

principles broadened and enlarged with time; and age, instead of

contracting, only served to mellow and ripen his nature. To

the last he continued open to the reception of new views, and,

though many thought him cautious to excess, he did not allow himself

to fall into that indiscriminating admiration of the past, which is

the palsy of many minds similarly educated, and renders the old age

of many nothing but a pity.

The indefatigable industry of Lord Brougham has become almost

proverbial. His public labours have extended over a period of

upwards of sixty years, during which he has ranged over many

fields—of law, literature, politics, and science,—and achieved

distinction in them all. How he contrived it, has been to many

a mystery. Once, when Sir Samuel Romilly was requested to

undertake some new work, he excused himself by saying that he had no

time; "but," he added, "go with it to that fellow Brougham, he seems

to have time for everything." The secret of it was, that he

never left a minute unemployed; withal he possessed a constitution

of iron. When arrived at an age at which most men would have

retired from the world to enjoy their hard-earned leisure, perhaps

to doze away their time in an easy chair, Lord Brougham commenced

and prosecuted a series of elaborate investigations as to the laws

of Light, and he submitted the results to the most scientific

audiences that Paris and London could muster. About the same

time, he was passing through the press his admirable sketches of the

'Men of Science and Literature of the Reign of George III.,' and

taking his full share of the law business and the political

discussions in the House of Lords. Sydney Smith once

recommended him to confine himself to only the transaction of so

much business as three strong men could get through. But such

was Brougham's love of work—long become a habit—that no amount of

application seems to have been too great for him; and such was his

love of excellence, that it has been said of him that if his station

in life had been only that of a shoe-black, he would never have

rested satisfied until he had become the best shoe-black in England.

Another hard-working man of the same class is Sir E. Bulwer

Lytton. Few writers have done more, or achieved higher

distinction in various walks—as a novelist, poet, dramatist,

historian, essayist, orator, and politician. He has worked his

way step by step, disdainful of ease, and animated throughout by the

ardent desire to excel. On the score of mere industry, there

are few living English writers who have written so much, and none

that have produced so much of high quality. The industry of

Bulwer is entitled to all the greater praise that it has been

entirely self-imposed. To hunt, and shoot, and live at

ease,—to frequent the clubs and enjoy the opera, with the variety of

London visiting and sight-seeing during the "season," and then off

to the country mansion, with its well-stocked preserves, and its

thousand delightful out-door pleasures,—to travel abroad, to Paris,

Vienna, or Rome,—all this is excessively attractive to a lover of

pleasure and a man of fortune, and by no means calculated to make

him voluntarily undertake continuous labour of any kind. Yet

these pleasures, all within his reach, Bulwer must, as compared with

men born to similar estate, have denied himself in assuming the

position and pursuing the career of a literary man. Like

Byron, his first effort was poetical ('Weeds and Wild Flowers'), and

a failure. His second was a novel ('Falkland'), and it proved

a failure too. A man of weaker nerve would have dropped

authorship; but Bulwer had pluck and perseverance; and he worked on,

determined to succeed. He was incessantly industrious, read

extensively, and from failure went courageously onwards to success.

'Pelham' followed 'Falkland' within a year, and the remainder of

Bulwer's literary life, now extending over a period of thirty years,

has been a succession of triumphs.

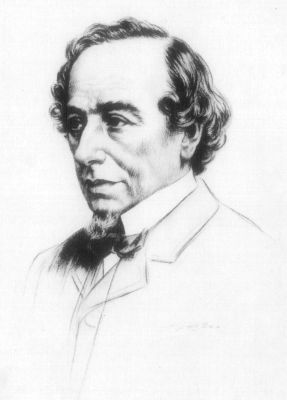

Mr. Disraeli affords a similar instance of the power of

industry and application in working out an eminent public career.

His first achievements were, like Bulwer's, in literature; and he

reached success only through a succession of failures. His

'Wondrous Tale of Alroy' and 'Revolutionary Epic' were laughed at,

and regarded as indications of literary lunacy. But he worked

on in other directions, and his 'Coningsby,' 'Sybil,' and 'Tancred,'

proved the sterling stuff of which he was made. As an orator

too, his first appearance in the House of Commons was a failure.

It was spoken of as "more screaming than an Adelphi farce."

Though composed in a grand and ambitious strain, every sentence was

hailed with "loud laughter." 'Hamlet' played as a comedy were

nothing to it. But he concluded with a sentence which embodied

a prophecy. Writhing under the laughter with which his studied

eloquence had been received, he exclaimed, "I have begun several

times many things, and have succeeded in them at last. I shall

sit down now, but the time will come when you will hear me."

The time did come; and how Disraeli succeeded in at length

commanding the attention of the first assembly of gentlemen in the

world, affords a striking illustration of what energy and

determination will do; for Disraeli earned his position by dint of

patient industry.

He did not, as many young men do, having once failed, retire

dejected, to mope and whine in a corner, but diligently set himself

to work. He carefully unlearnt his faults, studied the

character of his audience, practised sedulously the art of speech,

and industriously filled his mind with the elements of parliamentary

knowledge. He worked patiently for success; and it came, but

slowly: then the House laughed with him, instead of at him.

The recollection of his early failure was effaced, and by general

consent he was at length admitted to be one of the most finished and

effective of parliamentary speakers.

Although much may be accomplished by means of individual

industry and energy, as these and other instances set forth in the

following pages serve to illustrate, it must at the same time be

acknowledged that the help which we derive from others in the

journey of life is of very great importance. The poet

Wordsworth has well said that "these two things, contradictory

though they may seem, must go together—manly dependence and manly

independence, manly reliance and manly self-reliance." From

infancy to old age, all are more or less indebted to others for

nurture and culture; and the best and strongest are usually found

the readiest to acknowledge such help. Take, for example, the

career of the late Alexis de Tocqueville, a man doubly well-born,

for his father was a distinguished peer of France, and his mother a

granddaughter of Malesherbes. Through powerful family

influence, he was appointed Judge Auditor at Versailles when only

twenty-one; but probably feeling that he had not fairly won the

position by merit, he determined to give it up and owe his future

advancement in life to himself alone. "A foolish resolution,"

some will say; but De Tocqueville bravely acted it out. He

resigned his appointment, and made arrangements to leave France for

the purpose of travelling through the United States, the results of

which were published in his great book on 'Democracy in America.'

His friend and travelling companion, Gustave de Beaumont has

described his indefatigable industry during this journey. "His

nature," he says, "was wholly averse to idleness, and whether he was

travelling or resting, his mind was always at work . . . With

Alexis, the most agreeable conversation was that which was the most

useful. The worst day was the lost day, or the day ill spent;

the least loss of time annoyed him." Tocqueville himself wrote

to a friend "There is no time of life at which one can wholly cease

from action; for effort without one's self, and still more effort

within, is equally necessary, if not more so, when we grow old, as

it is in youth. I compare man in this world to a traveller

journeying without ceasing towards a colder and colder region; the

higher he goes, the faster he ought to walk. The great malady

of the soul is cold. And in resisting this formidable evil,

one needs not only to be sustained by the action of a mind employed,

but also by contact with one's fellows in the business of life." [p.25]

Notwithstanding de Tocqueville's decided views as to the

necessity of exercising individual energy and self-dependence, no

one could be more ready than he was to recognise the value of that

help and support for which all men are indebted to others in a

greater or less degree. Thus, he often acknowledged, with

gratitude, his obligations to his friends De Kergorlay and Stofells,—to

the former for intellectual assistance, and to the latter for moral

support and sympathy. To De Kergorlay he wrote—"Thine is the

only soul in which I have confidence, and whose influence exercises

a genuine effect upon my own. Many others have influence upon

the details of my actions, but no one has so much influence as thou

on the origination of fundamental ideas, and of those principles

which are the rule of conduct." De Tocqueville was not less

ready to confess the great obligations which he owed to his wife,

Marie, for the preservation of that temper and frame of mind which

enabled him to prosecute his studies with success. He believed

that a noble-minded woman insensibly elevated the character of her

husband, while one of a grovelling nature as certainly tended to

degrade it. [p.26]

In fine, human character is moulded by a thousand subtle

influences; by example and precept; by life and literature; by

friends and neighbours; by the world we live in as well as by the

spirits of our forefathers, whose legacy of good words and deeds we

inherit. But great, unquestionably, though these influences

are acknowledged to be, it is nevertheless equally clear that men

must necessarily be the active agents of their own well-being and

well-doing; and that, however much the wise and the good may owe to

others, they themselves must in the very nature of things be their

own best helpers.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER II.

LEADERS OF INDUSTRY—INVENTORS AND PRODUCERS.

"Le travail et la Science sont désormais les maîtres

du monde."—De Salvandy.

"Deduct all that men of the humbler classes have done for England in

the way of inventions only, and see where she would have been but

for them."—Arthur Helps.

ONE of the most

strongly-marked features of the English people is their spirit of

industry, standing out prominent and distinct in their past history,

and as strikingly characteristic of them now as at any former

period. It is this spirit, displayed by the commons of

England, which has laid the foundations and built up the industrial

greatness of the empire. This vigorous growth of the nation

has been mainly the result of the free energy of individuals, and it

has been contingent upon the number of hands and minds from time to

time actively employed within it, whether as cultivators of the

soil, producers of articles of utility, contrivers of tools and

machines, writers of books, or creators of works of art. And

while this spirit of active industry has been the vital principle of

the nation, it has also been its saving and remedial one,

counteracting from time to time the effects of errors in our laws

and imperfections in our constitution.

The career of industry which the nation has pursued, has also

proved its best education. As steady application to work is

the healthiest training for every individual, so is it the best

discipline of a state. Honourable industry travels the same

road with duty; and Providence has closely linked both with

happiness. The gods, says the poet, have placed labour and

toil on the way leading to the Elysian fields. Certain it is

that no bread eaten by man is so sweet as that earned by his own

labour, whether bodily or mental. By labour the earth has been

subdued, and man redeemed from barbarism; nor has a single step in

civilization been made without it. Labour is not only a

necessity and a duty, but a blessing only the idler feels it to be a

curse. The duty of work is written on the thews and muscles of

the limbs, the mechanism of the hand, the nerves and lobes of the

brain—the sum of whose healthy action is satisfaction and enjoyment.

In the school of labour is taught the best practical wisdom; nor is

a life of manual employment, as we shall hereafter find,

incompatible with high mental culture.

Hugh Miller, than whom none

knew better the strength and the weakness belonging to the lot of

labour, stated the result of his experience to be, that Work, even

the hardest, is full of pleasure and materials for self-improvement.

He held honest labour to be the best of teachers, and that the

school of toil is the noblest of schools—save only the Christian

one,—that it is a school in which the ability of being useful is

imparted, the spirit of independence learnt, and the habit of

persevering effort acquired. He was even of opinion that the

training of the mechanic,—by the exercise which it gives to his

observant faculties, from his daily dealing with things actual and

practical, and the close experience of life which he

acquires,—better fits him for picking his way along the journey of

life, and is more favourable to his growth as a Man, emphatically

speaking, than the training afforded by any other condition.

The array of great names which we have already cursorily

cited, of men springing from the ranks of the industrial classes,

who have achieved distinction in various walks of life—in science,

commerce, literature, and art—shows that at all events the

difficulties interposed by poverty and labour are not

insurmountable. As respects the great contrivances and

inventions which have conferred so much power and wealth upon the

nation, it is unquestionable that for the greater part of them we

have been indebted to men of the humblest rank. Deduct what

they have done in this particular line of action, and it will be

found that very little indeed remains for other men to have

accomplished.

Inventors have set in motion some of the greatest industries

of the world. To them society owes many of its chief

necessaries, comforts, and luxuries; and by their genius and labour

daily life has been rendered in all respects more easy as well as

enjoyable. Our food, our clothing, the furniture of our homes,

the glass which admits the light to our dwellings at the same time

that it excludes the cold, the gas which illuminates our streets,

our means of locomotion by land and by sea, the tools by which our

various articles of necessity and luxury are fabricated, have been

the result of the labour and ingenuity of many men and many minds.

Mankind at large are all the happier for such inventions, and are

every day reaping the benefit of them in an increase of individual

well-being as well as of public enjoyment.

Though the invention of the working steam-engine—the king of

machines—belongs, comparatively speaking, to our own epoch, the idea

of it was born many centuries ago. Like other contrivances and

discoveries, it was effected step by step—one man transmitting the

result of his labours, at the time apparently useless, to his

successors, who took it up and carried it forward another stage,—the

prosecution of the inquiry extending over many generations.

Thus the idea promulgated by Hero of Alexandria was never altogether

lost; but, like the grain of wheat hid in the hand of the Egyptian

mummy, it sprouted and again grew vigorously when brought into the

full light of modern science. The steam-engine was nothing,

however, until it emerged from the state of theory, and was taken in

hand by practical mechanics; and what a noble story of patient,

laborious investigation, of difficulties encountered and overcome by

heroic industry, does not that marvellous machine tell of! It

is indeed, in itself, a monument of the power of self-help in man.

Grouped around it we find Savary, the military engineer; Newcomen,

the Dartmouth blacksmith; Cawley, the glazier; Potter, the

engine-boy; Smeaton, the

civil engineer; and, towering above all, the laborious, patient,

never-tiring James Watt, the

mathematical-instrument maker.

Watt was one of the most industrious of men; and the story of

his life proves, what all experience confirms, that it is not the

man of the greatest natural vigour and capacity who achieves the

highest results, but he who employs his powers with the greatest

industry and the most carefully disciplined skill—the skill that

comes by labour, application, and experience. Many men in his

time knew far more than Watt, but none laboured so assiduously as he

did to turn all that he did know to useful practical purposes.

He was, above all things, most persevering in the pursuit of facts.

He cultivated carefully that habit of active attention on which all

the higher working qualities of the mind mainly depend.

Indeed, Mr. Edgeworth entertained the opinion, that the difference

of intellect in men depends more upon the early cultivation of this

habit of attention, than upon any great disparity between the powers

of one individual and another.

Even when a boy, Watt found science in his toys. The

quadrants lying about his father's carpenter's shop led him to the

study of optics and astronomy; his ill health induced him to pry

into the secrets of physiology; and his solitary walks through the

country attracted him to the study of botany and history.

While carrying on the business of a mathematical-instrument maker,

he received an order to build an organ; and, though without an ear

for music, he undertook the study of harmonics, and successfully

constructed the instrument. And, in like manner, when the

little model of Newcomen's steam-engine, belonging to the University

of Glasgow, was placed in his hands to repair, he forthwith set

himself to learn all that was then known about heat, evaporation,

and condensation,—at the same time plodding his way in mechanics and

the science of construction,—the results of which he at length

embodied in his condensing steam-engine.

For ten years he went on contriving and inventing—with little

hope to cheer him, and with few friends to encourage him. He

went on, meanwhile, earning bread for his family by making and

selling quadrants, making and mending fiddles, flutes, and musical

instruments; measuring mason-work, surveying roads, superintending

the construction of canals, or doing anything that turned up, and

offered a prospect of honest gain. At length, Watt found a fit

partner in another eminent leader of industry—Matthew Boulton, of

Birmingham; a skilful, energetic, and far-seeing man, who vigorously

undertook the enterprise of introducing the condensing-engine into

general use as a working power; and the success of both is now

matter of history. [p.31]

Many skilful inventors have from time to time added new power

to the steam-engine; and, by numerous modifications, rendered it

capable of being applied to nearly all the purposes of

manufacture—driving machinery, impelling ships, grinding corn,

printing books, stamping money, hammering, planing, and turning

iron; in short, of performing every description of mechanical labour

where power is required. One of the most useful modifications

in the engine was that devised by Trevithick, and eventually

perfected by George Stephenson and his son, in the form of the

railway locomotive, by which social changes of immense importance

have been brought about, of even greater consequence, considered in

their results on human progress and civilization, than the

condensing-engine of Watt.

One of the first grand results of Watt's invention,—which

placed an almost unlimited power at the command of the producing

classes,—was the establishment of the cotton-manufacture. The

person most closely identified with the foundation of this great

branch of industry was unquestionably Sir Richard Arkwright, whose

practical energy and sagacity were perhaps even more remarkable than

his mechanical inventiveness. His originality as an inventor

has indeed been called in question, like that of Watt and

Stephenson. Arkwright probably stood in the same relation to

the spinning-machine that Watt did to the steam-engine and

Stephenson to the locomotive. He gathered together the

scattered threads of ingenuity which already existed, and wove them,

after his own design, into a new and original fabric. Though

Lewis Paul, of Birmingham, patented the invention of spinning by

rollers thirty years before Arkwright, the machines constructed by

him were so imperfect in their details, that they could not be

profitably worked, and the invention was practically a failure.

Another obscure mechanic, a reed-maker of Leigh, named Thomas Highs,

is also said to have invented the water-frame and spinning-jenny;

but they, too, proved unsuccessful.

When the demands of industry are found to press upon the

resources of inventors, the same idea is usually found floating

about in many minds,--such has been the case with the steam-engine,

the safety-lamp, the electric telegraph, and other inventions.

Many ingenious minds are found labouring in the throes of invention,

until at length the master mind, the strong practical man, steps

forward, and straightway delivers them of their idea, applies the

principle successfully, and the thing is done. Then there is a

loud outcry among all the smaller contrivers, who see themselves

distanced in the race; and hence men such as Watt, Stephenson, and

Arkwright, have usually to defend their reputation and their rights

as practical and successful inventors.

Richard Arkwright, like most of our great mechanicians,

sprang from the ranks. He was born in Preston in 1732.

His parents were very poor, and he was the youngest of thirteen

children. He was never at school: the only education he

received he gave to himself; and to the last he was only able to

write with difficulty. When a boy, he was apprenticed to a

barber, and after learning the business, he set up for himself in

Bolton, where he occupied an underground cellar, over which he put

up the sign, "Come to the subterraneous barber—he shaves for a

penny." The other barbers found their customers leaving them,

and reduced their prices to his standard, when Arkwright, determined

to push his trade, announced his determination to give "A clean

shave for a halfpenny." After a few years he quitted his

cellar, and became an itinerant dealer in hair. At that time

wigs were worn, and wig-making formed an important branch of the

barbering business. Arkwright went about buying hair for the

wigs. He was accustomed to attend the hiring fairs throughout

Lancashire resorted to by young women, for the purpose of securing

their long tresses; and it is said that in negotiations of this sort

he was very successful. He also dealt in a chemical hair dye,

which he used adroitly, and thereby secured a considerable trade.

But he does not seem, notwithstanding his pushing character, to have

done more than earn a bare living.

The fashion of wig-wearing having undergone a change,

distress fell upon the wig-makers; and Arkwright, being of a

mechanical turn, was consequently induced to turn machine inventor

or "conjurer," as the pursuit was then popularly termed. Many

attempts were made about that time to invent a spinning-machine, and

our barber determined to launch his little bark on the sea of

invention with the rest. Like other self-taught men of the

same bias, he had already been devoting his spare time to the

invention of a perpetual-motion machine; and from that the

transition to a spinning-machine was easy. He followed his

experiments so assiduously that he neglected his business, lost the

little money he had saved, and was reduced to great poverty.

His wife—for he had by this time married—was impatient at what she

conceived to be a wanton waste of time and money, and in a moment of

sudden wrath she seized upon and destroyed his models, hoping thus

to remove the cause of the family privations. Arkwright was a

stubborn and enthusiastic man, and he was provoked beyond measure by

this conduct of his wife, from whom he immediately separated.

In travelling about the country, Arkwright had become

acquainted with a person named Kay, a clockmaker at Warrington, who

assisted him in constructing some of the parts of his

perpetual-motion machinery. It is supposed that he was

informed by Kay of the principle of spinning by rollers; but it is

also said that the idea was first suggested to him by accidentally

observing a red-hot piece of iron become elongated by passing

between iron rollers. However this may be, the idea at once

took firm possession of his mind, and he proceeded to devise the

process by which it was to be accomplished, Kay being able to tell

him nothing on this point. Arkwright now abandoned his

business of hair collecting, and devoted himself to the perfecting

of his machine, a model of which, constructed by Kay under his

directions, he set up in the parlour of the Free Grammar School at

Preston. Being a burgess of the town, he voted at the

contested election at which General Burgoyne was returned; but such

was his poverty, and such the tattered state of his dress, that a

number of persons subscribed a sum sufficient to have him put in a

state fit to appear in the poll-room. The exhibition of his

machine in a town where so many workpeople lived by the exercise of

manual labour proved a dangerous experiment; ominous growlings were

heard outside the school-room from time to time, and Arkwright,

remembering the fate of Kay, who was mobbed and compelled to fly

from Lancashire because of his invention of the fly-shuttle, and of

poor Hargreaves, whose spinning-jenny had been pulled to pieces only

a short time before by a Blackburn mob,—wisely determined on packing

up his model and removing to a less dangerous locality. He

went accordingly to Nottingham, where he applied to some of the

local bankers for pecuniary assistance; and the Messrs. Wright

consented to advance him a sum of money on condition of sharing in

the profits of the invention. The machine, however, not being

perfected so soon as they had anticipated, the bankers recommended

Arkwright to apply to Messrs. Strutt and Need, the former of whom

was the ingenious inventor and patentee of the stocking-frame.

Mr. Strutt at once appreciated the merits of the invention, and a

partnership was entered into with Arkwright, whose road to fortune

was now clear. The patent was secured in the name of "Richard

Arkwright, of Nottingham, clockmaker," and it is a circumstance

worthy of note, that it was taken out in 1769, the same year in

which Watt secured the patent for his steam-engine. A

cotton-mill was first erected at Nottingham, driven by horses; and

another was shortly after built, on a much larger scale, at

Cromford, in Derbyshire, turned by a water-wheel, from which

circumstance the spinning-machine came to be called the water-frame.

Arkwright's labours however, were, comparatively speaking,

only begun. He had still to perfect all the working details of

his machine. It was in his hands the subject of constant

modification and improvement, until eventually it was rendered

practicable and profitable in an eminent degree. But success

was only secured by long and patient labour: for some years, indeed,

the speculation was disheartening and unprofitable, swallowing up a

very large amount of capital without any result. When success

began to appear more certain, then the Lancashire manufacturers fell

upon Arkwright's patent to pull it in pieces, as the Cornish miners

fell upon Boulton and Watt to rob them of the profits of their

steam-engine. Arkwright was even denounced as the enemy of the

working people; and a mill which he built near Chorley was destroyed

by a mob in the presence of a strong force of police and military.

The Lancashire men refused to buy his materials, though they were

confessedly the best in the market. Then they refused to pay

patent-right for the use of his machines, and combined to crush him

in the courts of law. To the disgust of right-minded people,

Arkwright's patent was upset. After the trial, when passing

the hotel at which his opponents were staying, one of them said,

loud enough to be heard by him, "Well we've done the old shaver at

last;" to which he coolly replied, "Never mind, I've a razor left

that will shave you all." He established new mills in

Lancashire, Derbyshire, and at New Lanark, in Scotland. The

mills at Cromford also came into his hands at the expiry of his

partnership with Strutt, and the amount and the excellence of his

products were such, that in a short time he obtained so complete a

control of the trade, that the prices were fixed by him, and he

governed the main operations of the other cotton-spinners.

Arkwright was a man of great force of character, indomitable

courage, much worldly shrewdness, with a business faculty almost

amounting to genius. At one period his time was engrossed by

severe and continuous labour, occasioned by the organising and

conducting of his numerous manufactories, sometimes from four in the

morning till nine at night. At fifty years of age he set to

work to learn English grammar, and improve himself in writing and

orthography. After overcoming every obstacle, he had the

satisfaction of reaping the reward of his enterprise. Eighteen

years after he had constructed his first machine, he rose to such

estimation in Derbyshire that he was appointed High Sheriff of the

county, and shortly after George III. conferred upon him the honour

of knighthood. He died in 1792. Be it for good or for

evil, Arkwright was the founder in England of the modern factory

system, a branch of industry which has unquestionably proved a

source of immense wealth to individuals and to the nation.

All the other great branches of industry in Britain furnish

like examples of energetic men of business, the source of much

benefit to the neighbourhoods in which they have laboured, and of

increased power and wealth to the community at large. Amongst

such might be cited the Strutts of Belper; the Tennants of Glasgow;

the Marshalls and Gotts of Leeds; the Peels, Ashworths, Birleys,

Fieldens, Ashtons, Heywoods, and Ainsworths of South Lancashire,

some of whose descendants have since become distinguished in

connection with the political history of England. Such

pre-eminently were the Peels of South Lancashire.

The founder of the Peel family, about the middle of last

century, was a small yeoman, occupying the Hole House Farm, near

Blackburn, from which he afterwards removed to a house situated in

Fish Lane in that town. Robert Peel, as he advanced in life,

saw a large family of sons and daughters growing up about him; but

the land about Blackburn being somewhat barren, it did not appear to

him that agricultural pursuits offered a very encouraging prospect

for their industry. The place had, however, long been the seat

of a domestic manufacture—the fabric called "Blackburn greys,"

consisting of linen weft and cotton warp, being chiefly made in that

town and its neighbourhood. It was then customary—previous to

the introduction of the factory system—for industrious yeomen with

families to employ the time not occupied in the fields in weaving at

home; and Robert Peel accordingly began the domestic trade of

calico-making. He was honest, and made an honest article;

thrifty and hardworking, and his trade prospered. He was also

enterprising, and was one of the first to adopt the carding

cylinder, then recently invented.

But Robert Peel's attention was principally directed to the

printing of calico—then a comparatively unknown art—and for

some time he carried on a series of experiments with the object of

printing by machinery. The experiments were secretly conducted

in his own house, the cloth being ironed for the purpose by one of

the women of the family. It was then customary, in such houses

as the Peels, to use pewter plates at dinner. Having sketched

a figure or pattern on one of the plates, the thought struck him

that an impression might be got from it in reverse, and printed on

calico with colour. In a cottage at the end of the farm-house

lived a woman who kept a calendering machine, and going into her

cottage, he put the plate with colour rubbed into the figured part

and some calico over it, through the machine, when it was found to

leave a satisfactory impression. Such is said to have been the

origin of roller printing on calico. Robert Peel shortly

perfected his process, and the first pattern he brought out was a

parsley leaf; hence he is spoken of in the neighbourhood of

Blackburn to this day as "Parsley Peel." The process of calico

printing by what is called the mule machine—that is, by means of a

wooden cylinder in relief, with an engraved copper cylinder—was