|

HUGH MILLER

(1802-56)

Geologist, journalist and author.

A Brief Biography by

Samuel

Smiles.

|

|

|

HUGH MILLER.

A Calotype, ca 1843. |

MEN may learn much that is

good from each other's lives,—especially from good men's lives. Men

who live in our daily sight, as well as men who have lived before us, and

handed down illustrious examples for our imitation, are the most valuable

practical teachers. For it is not mere literature that makes men,—it

is real, practical life, that chiefly moulds our nature, enables us to

work out our own education, and to build up our own character.

HUGH

MILLER has very strikingly worked out

this idea in his admirable autobiography, entitled, "My Schools and

Schoolmasters." It is extremely interesting, even fascinating, as a book;

but it is more than an ordinary book,—it might almost be called an

institution. It is the history of the formation of a truly noble and

independent character in the humblest condition of life,—the condition in

which a large mass of the people of this country are born and brought up;

and it teaches all, but especially poor men, what it is in the power of

each to accomplish for himself. The life of Hugh Miller is full of

lessons of self-help and self-respect, and shows the efficacy of these in

working out for a man an honourable competence and a solid reputation. It

may not be that every man has the thew and sinew, the large brain and

heart, of a Hugh Miller,—for there is much in what we may call the breed

of a man, the defect of which no mere educational advantages can supply;

but every man can at least do much, by the help of such examples as his,

to elevate himself, and build up his moral and intellectual character on a

solid foundation.

|

"....on finding in my copybook, on one occasion, a page filled

with rhymes, which I had headed "Poem on Care," he brought it to his

desk, and, after reading it carefully over, called me up, and with

his closed penknife, which served as a pointer, in the one hand, and

the copybook brought down to the level of my eyes in the other,

began his criticism. "That's bad grammar, Sir," he said,

resting the knife-handle on one of the lines; "and here's an

ill-spelt word; and there's another; and you have not at all

attended to the punctuation; but the general sense of the piece is

good,—very good indeed, Sir." And then he added, with a grim

smile, "Care, Sir, is, I daresay, as you remark, a very bad

thing; but you may safely bestow a little more of it on your

spelling and your grammar...."

A schoolmasterly criticism of Miller's juvenile 'Poem

on Care', from

'My Schools and Schoolmasters.' |

We have spoken of the breed of a man. In Hugh Miller we have an

embodiment of that most vigorous and energetic element of English national

life,—the Norwegian and Danish. In times long, long ago, the daring and

desperate pirates of these nations swarmed along the eastern coasts. In

England they were resisted by force of arms, for the prize of England's

crown was a rich one; yet, by dint of numbers, valour, and bravery, they

made good their footing in England, and even governed the eastern part of

it by their own kings until the time of Alfred the Great. And to this day

the Danish element amongst the population of the east and northeast of

England is by far the prevailing one. But in Scotland it was different.

They never reigned there; but they settled and planted all the eastern

coasts. The land was poor and thinly peopled; and the Scottish kings and

chiefs were too weak—generally too much occupied by intestine broils—to

molest or dispossess them. Then these Danes and Norwegians led a

seafaring life, were sailors and fishermen, which the native Scots were

not. So they settled down in all the bays and bights along the coast of

Scotland, and took entire possession of the Orkneys, Shetland, and Western

Isles, the Shetlands having been held by the crown of Denmark down to a

comparatively recent period. They never amalgamated with the Scotch

Highlanders; and to this day they speak a different language, and follow

different pursuits. The Highlander was a hunter, a herdsman, a warrior,

and fished in the fresh waters only. The descendants of the Norwegians,

or the Lowlanders, as they came to be called, followed the sea, fished in

salt waters, cultivated the soil, and engaged in trade and commerce.

Hence the marked difference between the population of the town of

Cromarty—where Hugh Miller was born, in 1802—and the population only a few

miles inland; the townspeople speaking Lowland Scotch, and being dependent

for their subsistence mainly on the sea,—the others speaking Gaelic, and

living solely, upon the land.

|

"....The concluding

evening prayer was one of great solemnity and unction. I was unacquainted

with the language in which it was couched; but it was impossible to avoid

being struck, notwithstanding, with its wrestling earnestness and fervour. The man who poured it forth evidently believed there was an unseen ear

open to it, and an all-seeing presence in the place, before

whom every secret thought lay exposed. The entire scene was a deeply

impressive one; and when I saw, in witnessing the celebration of high mass

in a Popish cathedral many years after, the altar suddenly enveloped in a

dim and picturesque obscurity, amid which the curling smoke of the incense

ascended, and heard the musically-modulated prayer sounding in the

distance from within the screen, my thoughts reverted to the rude Highland

cottage, where, amid solemnities not theatric, the red umbry light of the

fire fell with uncertain glimmer upon dark walls, and bare black rafters,

and kneeling forms, and a pale expanse of dense smoke, that, filling the

upper portion of the roof, overhung the floor like a ceiling, and there

arose amid the gloom the sounds of prayer truly God-directed, and poured

out from the depths of the heart...."

Evening prayers in a Highland cottage, spoken in

Gaelic, from

'My Schools and Schoolmasters.'

|

These Norwegian colonists of Cromarty held in their blood the very same

piratical propensities which characterized their forefathers who followed

the Vikings. Hugh Miller first saw the light in a long, low-built house,

built by his great-grandfather, John Feddes, "one of the last of the

buccaneers;" this cottage having been built, as Hugh Miller himself says

he has every reason to believe, with "Spanish gold." All his ancestors

were sailors and seafaring men; when boys they had taken to the water as

naturally as ducklings. Traditions of adventures by sea were rife in the

family. Of his grand-uncles, one had sailed round the world with Anson,

had assisted in burning Paeta, and in boarding the Manilla galleon;

another, a handsome and powerful man, perished at sea in a storm; and his

grandfather was dashed overboard by the jib-boom of his little vessel when

entering the Cromarty Firth, and never rose again. The son of this last,

Hugh Miller's father, was sent into the country by his mother to work upon

a farm, thus to rescue him, if possible, from the hereditary fate of the

family. But it was of no use. The propensity for the salt water, the

very instinct of the breed, was too powerful within him. He left the

farm, went to sea, became a man-of-war's man, was in the battle with the

Dutch off the Dogger Bank, sailed all over the world, then took "French

leave" of the royal navy, returned to Cromarty with money enough to buy a

sloop and engage in trade on his own account. But this vessel was one

stormy night knocked to pieces on the bar of Findhorn, the master and his

men escaping with difficulty; then another vessel was fitted out by him,

by the help of his friends, and in this he was trading from place to place

when Hugh Miller was born.

|

".....The other half of the prospect embraces the iron and

coal districts, with their many towns and villages, their smelting

furnaces, forges, steam-engines, tall chimneys, and pit-fires

innumerable; and beyond the whole lies the huge Birmingham, that

covers its four square miles of surface with brick. No day, however

bright and clear, gives a distinct landscape in this direction,—all

is dingy and dark; the iron furnaces vomit smoke night and noon,

Sabbath-day and week-day; and the thick reek rises ceaselessly to

heaven, league beyond league, like the sulphurous cloud of some

never-ending battle."

A distant vista of Birmingham, from 'First

Impressions of England and its People.' |

What a vivid picture of sea-life, as seen from the shore at least, do

we obtain from the early chapters of Miller's life! "I retain," says he,

"a vivid recollection of the joy which used to light up the household on

my father's arrival, and how I learned to distinguish for myself his sloop

when in the offing, by the two slim stripes of white that ran along her

sides, and her two square topsails." But a terrible calamity—though an

ordinary one in sea-life—suddenly plunged the sailor's family in grief;

and he, too, was gathered to the same grave in which so many of his

ancestors lay,—the deep ocean. A terrible storm overtook his vessel near

Peterhead; numbers of ships were lost along the coast; vessel after vessel

came ashore, and the beach was strewn with wrecks and dead bodies, but no

remnant of either the ship or bodies of Miller and his crew was ever cast

up. It was supposed that the little sloop, heavily laden, and labouring

in a mountainous sea, must have started a plank and foundered. Hugh

Miller was but a child at the time, having only completed his fifth year.

The following remarkable "appearance," very much in Mrs. Crowe's way, made

a strong impression upon him at the time. The house-door had blown open,

in the gray of evening, and the boy was sent by his mother to shut it.

|

"....It is surely a remarkable fact, that in an army never more than

seven miles removed from the base line of its operations, the distress

suffered was so great, that nearly five times the number of men sank under

it than perished in battle. There was no want among them of pinheading and

pinheaded martinets. The errors of officers such as Lucan and

Cardigan are understood to be all on the side of severity. . . . So far as the statistics of the British portion of

this greatest of sieges have yet been ascertained, rather more than three

thousand men perished in battle by the shot or steel of the enemy, or

afterwards of their wounds, and rather more than fifteen thousand men of

privation and disease. As for the poor soldiers themselves, they

could do but little in even more favourable circumstances under the

pinheading martinets...."

Characteristics of the Crimean War, from

Leading Articles. |

"Day had not wholly disappeared, but it was fast posting on to night,

and a gray haze spread a neutral tint of dimness over every more distant

object, but left the nearer ones comparatively distinct, when I saw at the

open door, within less than a yard of my breast, as plainly as ever I saw

anything, a dissevered hand and arm stretched towards me. Hand and arm

were apparently those of a female: they bore a livid and sodden

appearance; and directly fronting me, where the body ought to have been,

there was only blank, transparent space, through which I could see the dim

forms of the objects beyond. I was fearfully startled, and ran shrieking

to my mother, telling what I had seen; and the house-girl, whom she next

sent to shut the door, affected by my terror, also returned frightened,

and said that she, too, had seen the woman's hand; which, however, did not

seem to be the case. And finally, my mother going to the door, saw

nothing, though she appeared much impressed by the extremeness of my

terror, and the minuteness of my description. communicate the story as it

lies fixed in my memory, without attempting to explain it: its coincidence

with the probable time of my father's death, seems at least curious."

|

"....Birmingham produces on the average a musket

per minute, night and day, throughout the year: it, besides, furnishes

the army with its swords, the navy with its cutlasses and pistols, and the

busy writers of the day with their steel pens by the hundredweight and the

ton; and thus it labours to deserve its name of the "Great Toy-shop of

Britain," by fashioning toys in abundance for the two most serious games

of the day—the game of war and the game of opinion-making."

The business of Birmingham, from 'First

Impressions of England and its People.' |

The little boy longed for his father's return, and continued to gaze

across the deep, watching for the sloop with its two stripes of white

along the sides. Every morning he went wandering about the little

harbour, to examine the vessels which had come in during the night; and he

continued to look out across the Moray Forth long after anybody else had

ceased to hope. But months and years passed, and the white stripes and

square topsails of his father's sloop he never saw again. The boy was

the son of a sailor's widow, and so grew up, in sight of the sea, and with

the same love of it that characterized his father. But he was sent to

school; first to a dame school, where he learnt his letters; he then

worked his way through the Catechism, the Proverbs, and the New Testament

and emerged into the golden region of "Sinbad the Sailor," "Jack the

Giant-Killer," "Beauty and the Beast," and "Aladdin and the Wonderful

Lamp." Other books followed,—the Pilgrim's Progress, Cook's and Anson's

Voyages, and Blind Harry the Rhymer's History of Wallace; which first

awoke within him a strong feeling of Scottish patriotism. And thus his

childhood grew, on proper child-like nourishment. His uncles were men of

solid sense and sound judgment, though uncultured by scholastic

education. One was a local antiquary, by trade a working harness-maker;

the other was of a strong religious turn: he was a working cartwright, and

in early life had been a sailor, engaged in nearly all Nelson's famous

battles. The examples and the conversation of these men were for the

growing boy worth any quantity of school primers: he learnt from them far

more than mere books could teach him.

|

"....The age has been peculiarly an

age of exploration—a locomotive age: commerce, curiosity, the spirit of

adventure, the desire of escaping from the tedium of inactive

life,—these, and other motives besides, have scattered travellers by

hundreds, during the period of our long European peace, over almost every

country of the world. And hence so mighty an increase of knowledge in this

department, that what the last age knew of the subject has been altogether

overgrown. Vast additions, too, have been made to the province of

mechanical contrivance: the constructive faculties of the country,

stimulated apparently by the demands of commerce and the influence of

competition both at home and abroad, have performed in well-nigh a single

generation the work of centuries..."

The 7th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica,

from 'Leading Articles.' |

But his school education was not neglected either.

From the dame's school he was transferred to the town's grammar school,

where, amidst about one hundred and fifty other boys and girls, he

received his real school education. But it did not amount to much.

There, however, the boy learnt life,—to hold his own,—to try his powers

with other boys,—physically and morally, as well as scholastically.

The school brought out the stuff that was in him in many ways, but the

mere book-learning was about the least part of the instruction.

|

"...It was Sabbath, but the morning rose like a hypochondriac

wrapped up in his night-clothes,—gray in fog, and sad with rain..."

At anchor in

the bay

of Kildonan, from 'The Cruise of the Betsey.' |

The school-house looked out on the beach, fronting the opening of the

Frith, and not a boat or a ship could pass in or out of the harbour of

Cromarty without the boys seeing it. They knew the rig of every craft,

and could draw them on their slates. Boats unloaded their glittering

cargoes on the beach, where the process of gutting afterwards went busily

on; and to add to the bustle, there was a large killing-place for pigs not

thirty yards from the school door, "where from eighty to a hundred pigs

used sometimes to die for the general good in a single day; and it was a

great matter to hear, at occasional intervals, the roar of death rising

high over the general murmur within, or to be told by some comrade,

returned from his five minutes' leave of absence, that a hero of a pig had

taken three blows of a hatchet ere it fell, and that, even after its

subjection to the sticking process, it had got hold of Jock Keddie's hand

in its mouth, and almost smashed his thumb." Certainly it is not in every

grammar-school that such lessons as these are taught.

|

"....On both sides the river the eye rests on a

multitude of scattered patches of green, that seem inlaid in the

brown heath. We trace on these islands of sward the marks of

furrows, and mark here and there, through the loneliness, the

remains of a group of cottages, well-nigh levelled with the soil,

and, haply like those ruins which eastern conquerors leave in their

track, still scathed with fire. All is solitude within the

valley, except where, at wide intervals, the

shieling of a shepherd

may be seen....It would seem as if for twenty miles the long

withdrawing valley had been swept of its inhabitants....And such

generally is the present state of Sutherland. The interior is

a solitude occupied by a few sheep-farmers and their hinds; while a

more numerous population than fell to the share of the entire

county, ere the inhabitants were expelled from their inland

holdings, and left to squat upon the coast, occupy the selvage of

discontent and poverty that fringes its shores....in this instance the victory of the lord of the soil over the

children of the soil was signal and complete. In little more than nine

years a population of fifteen thousand individuals were removed from the

interior of Sutherland to its sea-coasts, or had emigrated to America. The

inland districts were converted into deserts, through which the traveller

may take a long day's journey, amid ruins that still bear the scathe of

fire, and grassy patches betraying, when the evening sun casts aslant its

long deep shadows, the half-effaced lines of the plough...."

The terrible Highland 'clearances,' from

Sutherland as it Was and Is. |

Miller was put to Latin, but made little progress in it,—his master

had no method, and the boy was too fond of telling stories to his

schoolfellows in school hours to make much progress. Cock-fighting was a

school practice in those days, apparently the master having a perquisite

of two-pence for every cock that was entered by the boys on the days of the

yearly fight. But Miller had no love for this sport, although he paid his

entry money with the rest. In the mean time his miscellaneous reading

extended, and he gathered pickings of odd knowledge from all sorts of odd

quarters,— from workmen, carpenters, fishermen and sailors, old women,

and, above all, from the old boulders strewed along the shores of the

Cromarty Frith. With a big hammer, which had belonged to his

great-grandfather, John Feddes, the buccaneer, the boy went about chipping

the stones, and thus early accumulating specimens of mica, porphyry,

garnet, and such like, exhibiting them to his uncle Alexander, and other

admiring relations. Often, too, he had a day in woods to visit his

uncle, when working as a sawyer,—his trade of cartwright having, failed.

And there, too, the boy's attention was excited by the peculiar geological

curiosities which lay in his way. While searching among the stones and

rocks on the beach, he was sometimes asked, in humble irony, by the farm

servants who came to load their carts with sea-weed, whether he "was

gettin' siller in the stanes," but was so unlucky as never to be able to

answer their question in the affirmative. Uncle Sandy seems to have been

a close observer of nature, and in his humble way had his theories of

ancient sea beaches, the flood, and the formation of the world, which he

duly imparted to the wondering youth. Together they explored caves,

roamed the beach for crabs and lobsters, whose habits Uncle Sandy could

well describe; he also knew all about moths and butterflies, spiders, and

bees,—in short, was a born natural-history man, so that the boy regarded

him in the light of a professor, and, doubtless, thus early obtained from

him the bias toward his future studies.

|

". . . . It was a lovely evening of October.

The ancient elms and wild cherry-trees which surrounded the

burying-ground still retained their foliage entire, and the elms

were hung in gold, and the wild cherry-trees in crimson, and the

pale yellow tint of the straggling and irregular fields on the

hill-side contrasted strongly with the deepening russet of the

surrounding moor. The tombs and the ruins were bathed in the

yellow light of the setting sun; but to the melancholy and aimless

wanderer the quiet and gorgeous beauty of the scene was associated

with the coming night and the coming winter, with the sadness of

inevitable decay and the gloom of the insatiable grave."

The Chaplain's Lair, from

Scenes and Legends. |

|

|

|

Miller: a Calotype by Hill and Adamson -

period 1843-47. |

There was the usual number of hair-breadth

escapes in Miller's boy-life. One of them, when he and a companion had

got cooped up in a sea cave, and could not return because of the tide,

reminds us of the exciting scene described in Scott's Antiquary. There

were school-boy tricks, and schoolboy rambles, mischief-making in

companionship with other boys, of whom he was often the leader. Left very

much to himself, he was becoming a big, wild, insubordinate boy; and it

became obvious that the time was now come when Hugh Miller must enter that

world-wide school in which toil and hardship are the severe but noble

masters. After a severe fight and wrestling-match with his schoolmaster,

he left school, avenging himself for his defeat by penning and sending by

the teacher, that very night, a copy of satiric verses, entitled "The

Pedagogue," which occasioned a good deal of merriment in the place.

|

THE BABIE

NAE shoon to hide

her tiny taes,

Nae stockings on her feet;

Her supple ankles white as snow

Of early blossoms sweet.

Her simple dress of sprinkled pink,

Her double, dimpled chin;

Her pucker’d lip and bonny mou’,

With nae ane tooth between.

Her een sae like her mither’s een,

Twa gentle, liquid things;

Her face is like an angel’s face—

We’re glad she has nae wings. |

His boyhood over, and his school training ended, Hugh Miller must now

face the world of toil. His uncles were most anxious that he should

become a minister; and were even willing to pay his college expenses,

though the labour of their hands formed their only wealth. The youth,

however, had conscientious objections: he did not feel called to the

work; and the uncles, confessing that he was right, gave up their point.

Hugh was accordingly apprenticed to the trade of his choice,—that of a

working stone-mason; and he began his labouring career in a quarry

looking out upon the Cromarty Firth. This quarry proved one of his best

schools. The remarkable geological formations which it displayed awakened

his curiosity. The bar of deep-red stone beneath, and the bar of pale-red

clay above, were noted by the young quarryman, who, even in such

unpromising subjects, found matter for observation and reflection. Where

other men saw nothing, he detected analogies, differences, and

peculiarities, which set him a-thinking. He simply kept his eyes and his

mind open; was sober, diligent, and persevering; and this was the secret

of his intellectual growth.

|

"...The

shieling, a rude low-roofed erection of turf and

stone, with a door in the centre some five feet in height or so, but

with no window, rose on the grassy slope immediately in front of the

vast continuous rampart. A slim pillar of smoke ascends from

the roof, in the calm, faint and blue within the shadow of the

precipice, but it caught the sun-light in its ascent, and blushed,

ere it melted into the ether, a ruddy brown..."

On approaching a shepherd's hut, from 'The Cruise of the Betsey.' |

Hugh Miller takes a cheerful view of the lot of labour. While others

groan because they have to work hard for their bread, he says that work is

full of pleasure, of profit, and of materials for self-improvement. He

holds that honest labour is the best of all teachers, and that the school

of toil is the best and noblest of all schools, save only the Christian

one,—a school in which the ability of being useful is imparted, and the

spirit of independence communicated, and the habit of persevering effort

acquired. He is even of opinion that the training of the mechanic, by the

exercise which it gives to his observant faculties, from his daily

dealings with things actual and practical, and the close experience of

life which he invariably acquires, is more favourable to his growth as a

Man, emphatically speaking, than the training which is afforded by any

other condition of life. And the array of great names which he cites in

support of his statement is certainly a large one. Nor is the condition

of the average well-paid operative at all so dolorous, according to Hugh

Miller, as many modern writers would have it to be. "I worked as an

operative mason," says he, "for fifteen years,—no inconsiderable portion

of the more active part of a man's life; but the time was not altogether

lost. I enjoyed in those years fully the average amount of happiness, and

learned to know more of the Scottish people than is generally known. Let

me add, that from the close of the first year in which I wrought as a

journeyman, until I took final leave of the mallet and chisel, I never

knew what it was to want a shilling; that my two uncles, my grandfather,

and the mason with whom I served my apprenticeship—all working-men—had had

a similar experience; and that it was the experience of my father also. I

cannot doubt that deserving mechanics may, in exceptional cases, be

exposed to want; but I can as little doubt that the cases are exceptional,

and that much of the suffering of the class is a consequence either of

improvidence on the part of the completely skilled, or of a course of

trifling during the term of apprenticeship,—quite as common as trifling at

school,—that always lands those who indulge in it in the hapless position

of the inferior workman."

|

"....the river,—after wailing for miles in a pent-up channel,

narrow as one of the lanes of old Edinburgh, and hemmed in by walls

quite as perpendicular, and nearly twice as lofty,—suddenly

expands, first into a deep brown pool, and then into a broad

tumbling stream, that, as if permanently affected in temper by the

strict severity of the discipline to which its early life had been

subjected, frets and chafes in all its after course, till it loses

itself in the sea."

The river

Auldgrande, near Evanton, from 'Rambles of a

Geologist.' |

There is much honest truth in this observation. At the same time, it

is clear that the circumstances under which Hugh Miller was brought up and

educated are not enjoyed by all workmen,—are, indeed, experienced by

comparatively few. In the first place, his parentage was good, his father

and mother were a self-helping, honest, intelligent pair, in humble

circumstances, but yet comparatively comfortable. Thus his early

education was not neglected. His relations were sober, industrious, and

"God-fearing," as they say in the north. His uncles were not his least

notable instructors. One of them was a close observer of nature, and in

some sort a scientific man, possessed of a small but good library of

books. Then Hugh Miller's own constitution was happily trained. As one

of his companions once said to him, "Ah, Miller, you have stamina in you,

and will force your way; but I want strength; the world will never hear

of me." It is the stamina which Hugh Miller possessed by nature, that

were born in him, and were carefully nurtured by his parents, that enabled

him as a working-man to rise, while thousands would have sunk or merely

plodded on through life in the humble station in which they were born.

And this difference in stamina and other circumstances is not sufficiently

taken into account by Hugh Miller in the course of the interesting, and,

on the whole, exceedingly profitable remarks, which he makes in his

autobiography on the condition of the labouring poor.

|

"....Perhaps no personage of real life can be

more properly regarded as a hermit of the churchyard than the

itinerant sculptor, who wanders from one country burying-ground to

another, recording on his tablets of stone the tears of the living

and the worth of the dead. . . . How often have I suffered my

mallet to rest on the unfinished epitaph, when listening to some

friend of the buried expatiating, with all the eloquence of grief,

on the mysterious warning—and the sad deathbed—on the worth that had

departed—and the sorrow that remained behind! How often,

forgetting that I was merely an auditor, have I so identified myself

with the mourner as to feel my heart swell, and my eyes becoming

moist! . . . . I have grieved above the half-soiled shroud of her

for whom the tears of bereavement had not yet been dried up, and

sighed over the mouldering bones of him whose very name had long

since perished from the earth."

The stone-mason

at work in Kirk-Michael churchyard, from 'Scenes

and Legends.' |

We can afford, in our brief space, to give only a very rapid outline

of Hugh Miller's fifteen years' life as a workman. He worked away in the

quarry for some time, losing many of his finger-nails by bruises and

accidents, growing fast, but gradually growing stronger, and obtaining a

fair knowledge of his craft as a stone-hewer. He was early subjected to

the temptation which besets most young workmen,—that of drink. But he

resisted it bravely. His own account of it is worthy of extract :—

"When overwrought, and in my depressed moods, I learned to regard the

ardent spirits of the dram-shop as high luxuries; they gave lightness and

energy to both body and mind, and substituted for a state of dulness and

gloom one of exhilaration and enjoyment. Usquebhae was simply happiness

doled out by the glass, and sold by the gill. The drinking usages of the

profession in which I laboured were at this time many; when a foundation

was laid, the workmen were treated to drink; they were treated to drink

when the walls were levelled for laying the joists; they were treated to

drink when the building was finished; they were treated to drink when an

apprentice joined the squad; treated to drink when his 'apron was washed;'

treated to drink when his ' time was out;' and occasionally they learnt to

treat one another to drink. In laying down the foundation stone of one of

the larger houses built this year by Uncle David and his partner, the

workmen had a royal 'founding-pint,' and two whole glasses of the whiskey

came to my share. A full-grown man would not have deemed a gill of

usquebhae an overdose, but it was considerably too much for me; and when

the party broke up, and I got home to my books, I found, as I opened the

pages of a favourite author, the letters dancing before my eyes, and that

I could no longer master the sense. I have the volume at present before

me, a small edition of the Essays of Bacon, a good deal worn at the

corners by the friction of the pocket, for of Bacon I never tired. The

condition into which I had brought myself was, I felt, one of

degradation. I had sunk, by my own act, for the time, to a lower level of

intelligence than that on which it was my privilege to be placed; and

though the state could have been no very favourable one for forming a

resolution, I in that hour determined that I should never again

sacrifice my capacity of intellectual enjoyment to a drinking usage; and,

with God's help, I was enabled to hold my determination."

A young working mason, reading Bacon's Essays in his by-hours, must

certainly be regarded as a remarkable man; but not less remarkable is the

exhibition of moral energy and noble self-denial in the instance we have

cited.

|

"...The entire scene suggested the idea of a land with which

man had done for ever;—the vapour-enveloped rocks,—the waste of

ebb-uncovered sand,—the deserted harbour,—the ruinous house,—the

melancholy rain-fretted tides eddying along the strip of brown

tangle in the foreground,—and, dim over all, the thick, slant lines

of the beating shower!..."

At anchor off Eigg on a rainy 'Sabbath', from 'The Cruise of the Betsey.' |

It was while working as a mason's apprentice, that the lower Old Red

Sandstone along the Bay of Cromarty presented itself to his notice; and

his curiosity was excited and kept alive by the infinite organic remains,

principally of old and extinct species of fishes, ferns, and ammonites,

which lay revealed along the coasts by the washings of waves, or were

exposed by the stroke of his mason's hammer. He never lost sight of this

subject; went on accumulating observations and comparing formations, until

at length, when no longer a working mason, many years afterwards, he gave

to the world his highly interesting work on the Old Red Sandstone, which

at once established his reputation as an accomplished scientific

geologist. But this work was the fruit of long years of patient

observation and research. As he modestly states in his autobiography,

"the only merit to which I lay claim in the case is that of patient

research, —a merit in which whoever wills may rival or surpass me; and

this humble faculty of patience, when rightly developed, may lead to more

extraordinary developments of idea than even genius itself." And he adds

how he deciphered the divine ideas in the mechanism and framework of

creatures in the second stage of vertebrate existence.

But it was long before Hugh Miller accumulated his extensive

geological observations, and acquired that self-culture which enabled him

to shape them into proper form. He went on diligently working at his

trade, but always observing and always reflecting. He says he could not

avoid being an observer; and that the necessity which made him a mason,

made him also a geologist. In the winter months, during which mason-work

is generally superseded in country places, he occupied his time with

reading, sometimes with visiting country friends,—persons of an

intelligent caste,—and often he strolled away amongst old Scandinavian

ruins and Pictish forts, speculating about their origin and history. He

made good use of his leisure. And when spring came round again, he would

set out into the Highlands, to work at building and hewing jobs with a

squad of other masons,—working hard, and living chiefly on oatmeal brose.

Some of the descriptions given by him of life in the remote Highland

districts are extremely graphic and picturesque, and have all the charm of

entire novelty. The kind of accommodation which he experienced may be

inferred from the observation made by a Highland laird to his uncle James,

as to the use of a crazy old building left standing beside a group of neat

modern offices. "He found it of great convenience," he said, "every time

his speculations brought a drove of pigs, or a squad of masons, that

way." This sort of life and its surrounding circumstances were not of a

poetical cast; yet the youth was now about the poetizing age, and during

his solitary rambles after his day's work, by the banks of the Conon, he

meditated poetry, and began to make verses. He would sometimes write

them out upon his mason's kit, while the rain was dropping through the

roof of the apartment upon the paper on which he wrote. It was a rough

life of poetic musing, yet he always contrived to mix up a high degree of

intellectual exercise and enjoyment with whatever manual labour he was

employed upon; and this, after all, is one of the secrets of a happy

life. While observing scenery and natural history, he also seems to have

very closely observed the characters of his fellow workmen, and he gives

us vivid and life-like portraits of some of the more remarkable of them in

his Autobiography. There were some rough and occasionally very wicked

fellows among his fellow-workmen, but he had strength of character, and

sufficient inbred sound principle, to withstand their contamination. He

was also proud,—and pride in its proper place is an excellent

thing,—particularly that sort of pride which makes a man revolt from doing

a mean action, or anything which would bring discredit on the, family.

This is the sort of true nobility which serves poor men in good stead

sometimes, and it certainly served Hugh Miller well.

|

"....I was fortunate in a fine breezy day, clear and sunshiny,

save where the shadows of a few dense piled-up clouds swept dark

athwart the landscape. In the secluded recesses of the valley

all was hot, heavy, and still; though now and then a fitful snatch

of a breeze, the mere fragment of some broken gust that seemed to

have lost its way, tossed for a moment the white cannach of the

bogs, or raised spirally into the air, for a few yards, the light

beards of some seeding thistle, and straightway let them down

again.

Suddenly, however, about noon, a shower

broke thick and heavy against the dark sides and gray scalp of the

Ward Hill, and came sweeping down the valley...."

A walk on the Island of Hoy, from 'Rambles of a

Geologist.' |

His apprenticeship ended, he "took jobs" for himself,—built a cottage

for his Aunt Jenny, which still stands, and after that went out working as

journeyman-mason. In his spare hours, he was improving himself by the

study of practical geometry, and made none the worse a mason on that

account. While engaged in helping to build a mansion on the western coast

of Ross-shire, he extended his geological and botanical observations,

noting all that was remarkable in the formation of the district. He also

drew his inferences from the condition of the people,—being very much

struck, above other things, with the remarkably contented state of the

Celtic population, although living in filth and misery. On this he

shrewdly observes: "It was one of the palpable characteristics of our

Scottish Highlanders, for at least the first thirty years of the century,

that they were contented enough, as a people; to find more to pity than to

envy in the condition of their Lowland neighbours; and I remember that at

this time, and for years after, I used to deem the trait a good one. I

have now, however, my doubts on the subject, and am not quite sure whether

a content so general as to be national may not, in certain circumstances,

be rather a vice than a virtue. It is certainly no virtue, when it has

the effect of arresting either individuals or peoples in their course of

development; and is perilously allied to great suffering, when the men who

exemplify it are so thoroughly happy amid the mediocrities of the present

that they fail to make provision for the contingencies of the future."

|

"....The infection spread with frightful rapidity. At Inver, though the population did not much exceed a hundred persons,

eleven bodies were committed to the earth, without shroud or coffin, in

one day; in two days after they had buried nineteen more. Many of the

survivors fled from the village, and took shelter, some in the woods, some

among the hollows of an extensive tract of sand-hills. But the pest

followed them to their hiding-places, and they expired in the open air. Whole families were found lying dead on their cottage floor. In one

instance, an infant, the only survivor, lay grovelling on the body of its

mother—the sole mourner in a charnel-house of the pestilence. Rows of

cottages, entirely divested of their inhabitants, were set on fire and

burned to the ground."

The Cholera, from 'Scenes

and Legends'. |

Trade becoming slack in the North, Hugh Miller took ship for

Edinburgh, where building was going briskly on (in 1824), to seek for

employment there as a stone-hewer. He succeeded, and lived as a workman

at Niddry, in the neighbourhood of the city, for some time; pursuing at

the same time his geological observations in a new field, Niddry being

located on the carboniferous system. Here also he met with an entirely

new class of men,—the colliers,—many of whom, strange to say, had been

born slaves; the manumission of the Scotch colliers having been

effected in comparatively modern times,—as late as the year 1775! So

that, after all, Scotland is not so very far ahead of the serfdom of

Russia.

|

"....It was on a fine calm morning,—one of those clear

sunshiny mornings of October when the gossamer goes sailing about in

long cottony threads, so light and fleecy that they seem the

skeleton remains of extinct cloudlets, and when the distant hills,

with their covering of gray frost-rime, seem, through the clear

close atmosphere, as if chiselled in marble. The sun was

rising over the town through a deep blood-coloured haze,—the smoke

of a thousand fires; and the huge fantastic piles of masonry that

stretched along the ridge looked dim and spectral through the cloud,

like the ghosts of an army of giants...."

A vista of Edinburgh, from 'Recollections

of Ferguson.' |

Returning to the North again, Miller next began business for himself

in a small way, as a hewer of tombstones for the good folks of Cromarty.

This change of employment was necessary, in consequence of the hewer's

disease, caused by inhaling stone-dust, which settles in the lungs, and

generally leads to rapid consumption, afflicting him with its premonitory

symptoms. The strength of his constitution happily enabled him to throw

off the malady, but his lungs never fairly recovered their former vigour.

Work not being very plentiful, he wrote poems, some of which appeared in

the newspapers; and in course of time a small collection of these pieces

was published by subscription. He very soon, however, gave up poetry

writing, finding that his humble accomplishment of verse was too narrow to

contain his thinking; so next time he wrote a book it was in prose, and

vigorous prose too, far better than his verse. But Miller had meanwhile

been doing what was better than either cutting tombstones or writing

poetry: he had been building up his character, and thereby securing the

respect of all who knew him. So that, when a branch of the Commercial Bank

was opened in Cromarty, and the manager cast about him to make selection

of an accountant, whom should he pitch upon but Hugh Miller, the

stone-mason? This was certainly a most extraordinary selection; but why

was it made? Simply because of the excellence of the man's character. He

had proved himself a true and a thoroughly excellent and trustworthy man

in a humble, capacity of life; and the inference was, that he would carry

the same principles of conduct into another and higher sphere of action.

Hugh Miller hesitated to accept the office, having but little knowledge of

accounts, and no experience in book-keeping; but the manager knew his

pluck and determined perseverance in mastering whatever he undertook;

above all, he had confidence in his character, and he would not take a

denial. So Hugh Miller was sent to Edinburgh to learn his new business at

the head bank.

|

"....One night, towards the close of last autumn, I visited the old chapel of

St. Regulus. The moon, nearly at full, was riding high overhead in a

troubled sky, pouring its light by fits, as the clouds passed, on the grey

ruins, and the mossy, tilt-like hillocks, which had been raised ages

before over the beds of the sleepers. The deep, dark shadows of the tombs

seemed stamped upon the sward, forming, as one might imagine, a kind of

general epitaph on the dead, but inscribed, like the handwriting on the

wall, in the characters of a strange tongue. A low breeze was creeping

through the long withered grass at my feet; a shower of yellow leaves

came rustling, from time to time, from an old gnarled elm that shot out

its branches over the burying-ground—and, after twinkling for a few seconds

in their descent, silently took up their places among the rest of the

departed; the rush of the stream sounded hoarse and mournful from the

bottom of the ravine, like a voice from the depths of the sepulchre; there

was a low, monotonous murmur, the mingled utterance of a thousand

sounds of earth, air, and water, each one inaudible in itself; and,

at intervals, the deep, hollow roar of waves came echoing from the

caves of the distant promontory, a certain presage of coming

tempest."

The Chapel of

St. Regulus, from Scenes and Legends. |

|

|

|

Miller: from a Calotype by Hill and Adamson -

period 1843-47. |

Throughout life, Miller seems to have invariably put his conscience

into his work. Speaking of the old man with whom he served his

apprenticeship as a mason, he says: "He made conscience of every stone

he laid. It was remarked in the place, that the walls built by Uncle

David never bulged nor fell; and no apprentice nor journeyman of his was

permitted, on any plea, to make 'slight work.'" And one of his own

Uncle James's instructions to him on one occasion was, "In all your

dealings, give your neighbour the cast of the baulk,—'good measure,

heaped up and running over,'—and you will not lose by it in the end."

These lessons were worth far more than what is often taught in schools,

and Hugh Miller seems to have framed his own conduct in life on the

excellent moral teaching which they conveyed. Speaking of his own career

as a workman, when on the eve of quitting it, he says: "I do think I acted

up to my uncle's maxim; and that, without injuring my brother workmen by

lowering their prices. I never yet charged an employer for a piece of

work that, fairly measured and valued, would not be rated at a slightly

higher sum than that at which it stood in my account."

Although he gained some fame in his locality by his poems, and still

more by his "Letters on the Herring Fisheries of Scotland," he was not, as

many self-raised men are, spoilt by the praise which his works called

forth. "There is," he says, "no more fatal error into which a working-man

of a literary turn can fall, than the mistake of deeming himself too good

for his humble employments; and yet it is a mistake as common as it is

fatal. I had already seen several poor wrecked mechanics, who, believing

themselves to be poets, and regarding the manual occupation by which they

could alone live in independence as beneath them, had become in

consequence little better than mendicants,—too good to work for their

bread, but not too good virtually to beg it; and looking upon them as

beacons of warning, I determined that, with God's help, I should give

their error a wide offing, and never associate the idea of meanness with

an honest calling, or deem myself too good to be independent." Full of

this manly and robust spirit, Hugh Miller pursued his career of

stone-hewing by day, and prose composition when the day's work was done,

until he entered upon his new vocation of banker's accountant. He showed

his self-denial, too, in waiting for a wife until he could afford to keep

one in respectable comfort, —his engagement lasting over five years,

before he was in a position to fulfil his promise. And then he married,

wisely and happily.

|

"....The evening was of great beauty: the sea spread out from

the cliffs to the far horizon like the sea of gold and crystal

described by the Prophet, and its warm orange lines so harmonized

with those of the sky that, passing over the dimly-defined line of

demarcation, the whole upper and nether expanse seemed but one

glorious firmament, with the dark Ailsa, like a thunder-cloud,

sleeping in the midst. The sun was hastening to his setting,

and threw his strong red light on the wall of rock which, loftier

and more imposing than the walls of even the mighty Babylon,

stretched onward along the beach, headland after headland, till the

last sank abruptly in the far distance, and only the wide ocean

stretched beyond...."

The coast of Kirkoswald, from 'Recollections

of Burns'. |

At Edinburgh, by dint of perseverance and application, Mr. Miller

shortly mastered his new business, and then returned to Cromarty, where he

was installed in office. His "Scenes and Legends of the North of

Scotland" were published about the same time, and were well received; and

in his leisure hours he proceeded to prepare his most important work, on

"The Old Red Sandstone." He also contributed to the "Border Tales," and

other periodicals. The Free-Church movement drew him out as a polemical

writer: and his Letter to Lord Brougham on the Scotch Church Controversy

excited so much attention, that the leaders of the movement in Edinburgh

invited him to undertake the editing of the Witness newspaper, the organ

of the Free-Church party. He accepted the invitation, and continued to

hold the editorship until his death, in 1856.

|

"....The evening, considering the lateness of the season, for

winter had set in, was mild and pleasant. The moon at full was

rising over the Cumnock hills, and casting its faint light on the

trees that rose around us, in their winding-sheets of brown and

yellow, like so many spectres, or that, in the more exposed glades

and openings of the wood, stretched their long naked arms to the

sky. A light breeze went rustling through the withered grass;

and I could see the faint twinkling of the falling leaves, as they

came showering down on every side of us...."

A night-time walk near Mossgiel

farm-house, from 'Recollections

of Burns.' |

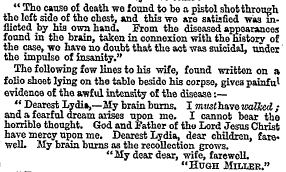

The circumstances connected with his decease were of a most

distressing character. On entering his room one morning, he was found

lying dead, shot through the body, and under circumstances which left no

doubt that he had died by his own hand. He had for some time been closely

applying himself to the completion of his "Testimony of the Rocks,"

without rest or relaxation, or due attention to his physical health.

Under these circumstances, overwork of the brain speedily began to tell

upon him. He could not sleep,—if he lay down and dozed, it was only to

wake in a start, his head filled with imaginary horrors; and in one of

these fits of his disease he put an end to his life;—a warning to all

brainworkers, that the powers of the human constitution may be strained

until they break, and that even the best and strongest mind cannot

dispense with the due observance of the laws which regulate the physical

constitution of man.

|

|

|

Extract from Miller's obituary in

THE TIMES, 29 Dec 1856. |

Ed. ―Miller took his life during the night of 23/24 December 1856.

_________________

|